Abstract

Corynebacterium (C.) bovis infection in nude mice causes hyperkeratosis and weight loss and has been reported worldwide but not in Korea. In 2011, nude mice from an animal facility in Korea were found to have white flakes on their dorsal skin. Histopathological testing revealed that the mice had hyperkeratosis and Gram-positive bacteria were found in the skin. We identified isolated bacteria from the skin lesions as C. bovis using PCR and 16S rRNA sequencing. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of C. bovis infection in nude mice from Korea.

Keywords: athymic nude mice, Corynebacterium bovis, hyperkeratosis

Corynebacterium (C.) bovis is a Gram-positive rod-shaped, non-spore forming, facultative anaerobic bacterium that causes bovine mastitis but is rarely pathogenic in humans [4,11]. This microorganism is also the cause of epidermal hyperkeratosis in nude mice. Affected animals develop small yellow-white flakes on the skin of the dorsum [9]. Corynebacterium-associated hyperkeratosis was described globally in the 1980s and 1990s [1,3,9]. However, this condition has not been previously reported in Korea.

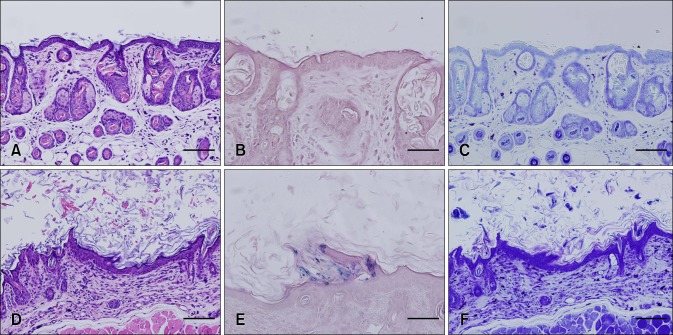

In 2011, athymic nude mice (nu/nu) from an animal facility maintained under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions had white scaly flakes on the dorsal skin. These mice were bought from a commercial vendor in Korea for experimental purposes and the client sent three mice (Test mouse 1, Test mouse 2, and Test mouse 3) to us for diagnosis. No additional information was provided about the characteristics of the outbreak. Upon gross examination, Test mouse 1 did not present any clinical signs. In contrast, Test mouse 2 and Test mouse 3 had yellow-white scales on the dorsal skin (Fig. 1), and their weight was lower than that suggested by the vendor (Table 1). For further diagnosis, matched healthy control mice (Central Lab Animal, Korea) were purchased and included in the analysis (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Gross lesions. (A) Test mouse 1, (B) Test mouse 2, and (C) Test mouse 3.

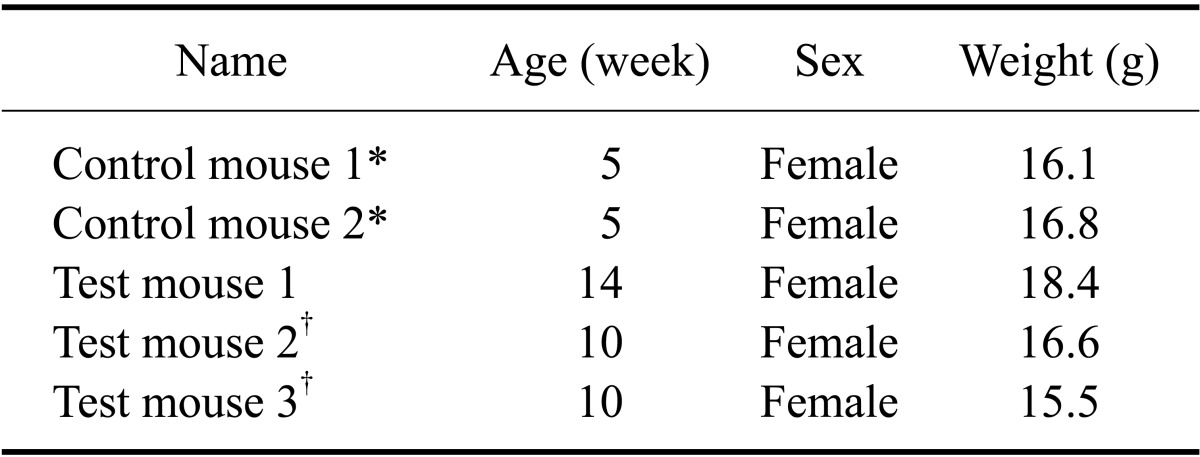

Table 1.

General characteristics of the experimental animals

*Mice purchased from a commercial vendor. †Mice with visible skin lesions.

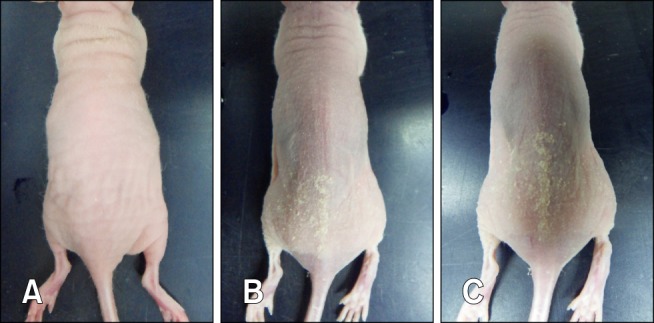

After sacrifice, skin samples from Control mouse 1 that had no gross skin lesions and Test mouse 3 that had the most severe symptoms were fixed with 10% neutralized formalin. The samples were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) along with Gram stain (Sigma-Aldrich) and toluidine blue (Sigma-Aldrich) for histopathological examination (Fig. 2). Hyperkeratosis (panel D in Fig. 2), Gram-positive bacilli (panel E in Fig. 2), and extensive mast cell infiltration into the dermis (panel F in Fig. 2) were observed in the skin of Test mouse 3 but not in that of Control mouse 1 (panels A-C in Fig. 2). Because there have been many reports of hyperkeratosis caused by C. bovis infection in nude mice, we surveyed for C. bovis in the skin using PCR and 16S rRNA sequence analysis [5].

Fig. 2.

Histopathological examination of skin samples from the experimental mice. H&E staining of skin tissue from Control mouse 2 (A), Gram-staining of skin tissue from Control mouce 2 (B), and toluidine blue staining of skin tissue from Control mouse 2 (C) revealed the presence of non-specific lesions and an absence of Gram staining. H&E staining of skin tissue from Test mouse 3 (D), Gram-staining of skin tissue from Test mouse 3 (E), and toluidine blue staining of skin tissue of Test mouse 3 (F) showed Gram-positive bacteria in the epidermis and severe mast cell infiltration into the dermis. Scale bars = 100 µm (A, C, D, F) or 50 µm (B, E).

To detect the presence of C. bovis in the skin lesions, a PCR analysis was performed with DNA samples extracted from skin tissue samples of the Control mice and Test mice, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, and a reference C. bovis strain obtained from the Korean Agricultural Culture Collection (KACC). Sequences of the C. bovis-specific primers [5] were 5'-GGTGTGGGGATCTTCCACGAT-3' (forward) and 5'-TGGGCTTGTTCACAGGTGGT-3 (reverse). The thermal cycler program was 95oC for 3 min followed by 35 cycles at 95℃ for 30 sec, 60oC for 30 sec, and 72℃ for 30 sec. The PCR program concluded with a 10-min extension period at 72℃. Amplified PCR bands were observed for Test mouse 1, 2, and 3 along with the C. bovis DNA samples. On the other hand, the bands were not observed for Control mouse 1 or 2 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus DNA samples (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Results of the polymerase chain reaction analysis. Lane 1, size marker; Lane 2, Control mouse 1; Lane 3, Control mouse 2; Lane 4, Test mouse 1; Lane 5, Test mouse 2; Lane 6, Test mouse 3; Lane 7, Lacobacillus rhamnosus; Lane 8, C. bovis.

To isolate bacteria from the skin lesions, swab samples were obtained by rubbing the dorsum skin of the Control and Test mice with a sterile cotton swab. The samples along with reference C. bovis bacteria were streaked onto blood agar plates (Hanil Komed, Korea) and incubated at 37℃ for 48 h in ambient air. After incubation, we selected colonies with the same morphology as those formed by C. bovis [9]. We isolated one characteristic colony from each Test mouse skin swab culture but none from the Control mouse skin swab cultures.

16S rRNA sequence analysis was next performed to identify bacteria from the isolated colonies. Sequencing was conducted using a commercial service (Macrogen, Korea). DNA from the colonies was prepared using InstaGene Matrix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA). PCR was performed to amplify the bacteria DNA fragment using 27F (5'-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTC) and Ag-3'/1492R (5'-TACGGYTACCTT GTTACGACT T-3') primers. The PCR products were purified using a Montage PCR Clean Up kit (Millipore, USA). Sequencing was performed with a Big Dye terminator cycle sequencing kit v.3.1 (Applied Biosystems, USA) and an Applied Biosystems model 3730XL automated DNA sequencing system (Applied Biosystems). 518F (5'-CCAGCAGCCGCGGTAATACG-3') and 800R (5'-TACCAGGGTATCTAATCC-3') primers were used for sequencing. A BLAST search confirmed that the sequences of tested colonies had a 99% similarity with that of the C. bovis 16S rRNA sequence.

Corynebacterium-associated hyperkeratosis can occur as an outbreak among both immunocompetent and immunodeficient mice, and is commonly observed in homozygous nude mice [6]. Infected mice may also lose weight and develop hyperemia of the conjunctiva [9]. The lesions tend to resolve spontaneously and disappear within 7~10 days [9]. Histologically, acanthosis, orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis, occasional dyskeratotic hair follicles with squamous metaplasia along the hair follicle neck, and mononuclear cell infiltration can be observed in the dermis [3].

C. bovis can be transmitted by direct contact with infected mice or via contaminated fomites such as gloves, cages, gowns, and bedding [3]. Persistent airborne contamination may account for continued transmission [9]. The infection spreads very quickly and morbidity can exceed more than 80% in a few days although mortality remains low at about 1% [9]. The origin of C. bovis in the animal facility is not clear and it is unknown whether hirsute mice can be vectors [3,6]. The original source of the infectious bacteria in the current case could not be determined.

Mice with symptoms of hyperkeratosis and weight loss due to C. bovis infection are considered unsuitable for experiments [3]. It has been reported that C. bovis infection affects research by decreasing tumor growth, interfering with xenografts, altering natural killer (NK) cell activity, and increasing water consumption [7,10]. It is very difficult to control C. bovis infection in facilities that house nude mice. Antibiotic treatment designed to eradicate C. bovis in nude mice is unsuccessful [1]. Cage changes and animal handling within a biosafety cabinet are not effective for preventing the spread of bacteria if infected mice are present in the colony [2]. Although results vary, the most effective methods for bacteria eradiation are colony depopulation and extensive environmental decontamination [2,9]. Barrier systems, restricted access, and scrubbing as well as autoclaving or disinfection of equipment and supplies prior to room entry or exit are also important for protection [1,2].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of C. bovis-associated hyperkeratosis in nude mice from Korea. C. bovis infection can cause the loss of precious animal resources such as immunodeficient nude mice and it is very difficult to eradicate the pathogen from animal care facilities. Thus, it is necessary to establish strategies including continuous monitoring programs to prevent C. bovis infection in nude mice.

Acknowledgments

We thank the KACC (Korean Agricultural Culture Collection) for supplying C. bovis specimens. This study was supported by the Research Institute for Veterinary Science, Seoul National University, Korea.

Footnotes

There is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Burr HN, Lipman NS, White JR, Zheng J, Wolf FR. Strategies to prevent, treat, and provoke Corynebacterium-associated hyperkeratosis in athymic nude mice. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2011;50:378–388. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burr HN, Wolf FR, Lipman NS. Corynebacterium bovis: epizootiologic features and environmental contamination in an enzootically infected rodent room. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2012;51:189–198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clifford CB, Walton BJ, Reed TH, Coyle MB, White WJ, Amyx HL. Hyperkeratosis in athymic nude mice caused by a coryneform bacterium: microbiology, transmission, clinical signs, and pathology. Lab Anim Sci. 1995;45:131–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalal A, Urban C, Ahluwalia M, Rubin D. Corynebacterium bovis line related septicemia: a case report and review of the literature. Scand J Infect Dis. 2008;40:575–577. doi: 10.1080/00365540701772448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duga S, Gobbi A, Asselta R, Crippa L, Tenchini ML, Simonic T, Scanziani E. Analysis of the 16S rRNA gene sequence of the coryneform bacterium associated with hyperkeratotic dermatitis of athymic nude mice and development of a PCR-based detection assay. Mol Cell Probes. 1998;12:191–199. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1998.0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gobbi A, Crippa L, Scanziani E. Corynebacterium bovis infection in immunocompetent hirsute mice. Lab Anim Sci. 1999;49:209–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanna N, Davis TW, Fidler IJ. Environmental and genetic factors determine the level of NK activity of nude mice and affect their suitability as models for experimental metastasis. Int J Cancer. 1982;30:371–376. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910300319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipsky BA, Goldberger AC, Tompkins LS, Plorde JJ. Infections caused by nondiphtheria corynebacteria. Rev Infect Dis. 1982;4:1220–1235. doi: 10.1093/clinids/4.6.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scanziani E, Gobbi A, Crippa L, Giusti AM, Giavazzi R, Cavalletti E, Luini M. Outbreaks of hyperkeratotic dermatitis of athymic nude mice in northern Italy. Lab Anim. 1997;31:206–211. doi: 10.1258/002367797780596310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharkey FE, Fogh J. Considerations in the use of nude mice for cancer research. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1984;3:341–360. doi: 10.1007/BF00051459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vale JA, Scott GW. Corynebacterium bovis as a cause of human disease. Lancet. 1977;2:682–684. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)90495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]