Abstract

Cytokines play diverse and critical roles in innate and acquired immunity, and several function within the central nervous system and in peripheral tissues to modulate energy metabolism. The extent to which changes in energy balance impact the expression and circulating levels of cytokines (many of which have pleiotropic functions) has not been systematically examined. To investigate metabolism-related changes in cytokine profiles, we used a multiplex approach to assess changes in 71 circulating mouse cytokines in response to acute (fasting and refeeding) and chronic (high-fat feeding) alterations in whole body metabolism. Refeeding significantly decreased serum levels of IL-22, IL-1α, soluble (s)IL-2Rα, and soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (VEGFR3), but markedly increased granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), IL-1β, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand (CCL2), sIL-1RI, lipocalin-2, pentraxin-3, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP-1), and serum amyloid protein (SAP) relative to the fasted state. Interestingly, only a few of these changes paralleled the alterations in expression of their corresponding mRNAs. Functional studies demonstrated that central delivery of G-CSF increased, whereas IL-22 decreased, food intake. Changes in food intake were not accompanied by acute alterations in orexigenic (Npy and Agrp) and anorexigenic (Pomc and Cart) neuropeptide gene expression in the hypothalamus. In the context of chronic high-fat feeding, circulating levels of chemokine (C-X-C) ligand (CXCL1), serum amyloid protein A3 (SAA3), TIMP-1, α1-acid glycoprotein (AGP), and A2M were increased, whereas IL-12p40, CCL4, sCD30, soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE), CCL12, CCL20, CX3CL1, IL-16, IL-22, and haptoglobin were decreased relative to mice fed a control low-fat diet. These results demonstrate that both short- and long-term changes in whole body metabolism extensively alter cytokine expression and circulating levels, thus providing a foundation and framework for further investigations to ascertain the metabolic roles for these molecules in physiological and pathological states.

Keywords: food intake, cytokines, metabolism, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, interleukin-22, obesity, fasting

proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines are secreted by a variety of cells in an immune response. Cytokines regulate a broad range of biological processes related to innate and adaptive immunity (1, 24). However, cytokines have also been shown to play significant roles in the regulation of food intake and energy homeostasis in the absence of infection or tissue injury (13, 33, 86). There appears to be reciprocal regulation and complex interplay between the immune and endocrine systems. In the context of metabolism, malnutrition has long been known to result in immune deficiency (19, 48, 52). In contrast, in the obese state, local and systemic production of proinflammatory cytokines is altered (80, 81), and elevated IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α levels impair systemic insulin sensitivity (38, 78). Indeed, low-grade inflammation contributes to and underlies obesity-related dysregulation in glucose and lipid metabolism. Paradoxically, obese individuals have a greater chance of survival when confronted with the immune challenge of severe, life-threatening, sepsis (43); however, in general, obesity tends to adversely affect the immune system in humans (39, 57, 58, 82) and in rodent models (21, 39, 40, 45, 74).

Although typically secreted by lymphocytes and macrophages, the secretion of cytokines by microglial cells suggests that these factors may act through central pathways in the brain to influence metabolic processes in the peripheral tissues (32, 60, 75). Thus far, a role for modulating food intake via the central nervous system (CNS) has been demonstrated for several cytokines, including IL-1β (49), IL-6 (70), TNF-α (26), IL-18 (86), and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (66). Despite their size and hydrophilicity, cytokines and other polypeptide hormones have been demonstrated to cross the blood-brain barrier (4–9, 11, 84). Further, the arcuate nucleus, which plays an important role in food intake regulation (71), is located in the mediobasal portion of the hypothalamus where the blood-brain barrier is thought to be semipermeable (44, 63), thus enabling circulating hormones and cytokines to gain access to neurons within the arcuate nucleus.

While the immune function of most cytokines is well established (1, 24), much less is known about their metabolic roles. The extent to which changes in metabolic state impact the expression and circulating levels of cytokines has not been systematically examined. Advancement in technology has made it possible now to simultaneously measure the circulating levels of a large number of cytokines at a reasonable cost using only a small volume of serum. Employing a bead-based multiplex profiling method, we performed a large-scale analysis of serum cytokine levels in response to acute and long-term changes in whole body metabolic states. Although not every known cytokine was included, the 71 cytokines (including secreted cytokine receptors and acute phase proteins) examined represent a well-studied set of molecules that encompass a variety of cytokine functions. These cytokines are known to act on a variety of immune and nonimmune cell types to regulate diverse physiological processes that include proinflammatory, anti-inflammatory, chemotactic, antiapoptotic, proangiogenic, proliferative, metabolic, and acute phase responses. We hypothesized that dynamic changes in circulating cytokine levels would be seen in accordance with changes in whole body metabolism, suggesting a role for cytokines in regulating energy balance. Our results indicate that circulating levels of many cytokines are indeed altered by fasting, refeeding, and consuming a high-fat diet. The extent of these changes has not been previously appreciated. Of the 12 cytokines that displayed significantly altered circulating levels after fasting and refeeding, we functionally characterized the role of two cytokines with marked changes, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) and IL-22, in modulating food intake.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Recombinant G-CSF and IL-22.

Carrier-free recombinant G-CSF, synthesized in bacteria, was obtained from Biolegend (San Diego, CA). Endotoxin levels for purified recombinant G-CSF were determined to be <0.01 ng/μg. Carrier-free recombinant IL-22, made in human embryonic kidney 293 mammalian cells, was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Boston, MA).

Animals.

Eight- or twenty-week-old C57BL/6J male mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were housed in a temperature (37°C)- and humidity (45% ± 5)-controlled vivarium, provided ad libitum access to water and a standard laboratory chow diet (2018, Harlan-Teklad, Indianapolis, IN), and maintained on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle. Before blood collection, “fasted” mice (n = 10) were provided free access to water but no food for 12 h. “Refed” mice (n = 10) were treated in the same manner as the fasted mice; however, prior to blood collection, mice were provided 2 h of access to food. On the basis of previous fasting/refeeding studies in rats (50), as well as our previous studies examining the expression and circulating levels of secreted hormones (Clq/TNF-related protein family members), a 2-h refeeding time point was sufficient to observe changes in transcript and plasma protein levels (64, 73, 79). To avoid confounding effects due to circadian-mediated fluctuations in serum cytokine levels, all mice were euthanized at the same time of day (between 10 and 11 AM). Food intake, body weight, and energy metabolism measurements began at the start of the dark cycle. Mice were housed in clear Plexiglas cages with alpha dry bedding. A wire mesh floor was inserted into the cage to measure food intake. Spillage of food was collected and subtracted from the total food intake.

For the low-fat diet (LFD; n = 12) vs. high-fat diet (HFD; n = 12) study, C57BL/6J male mice were fed ad libitum an HFD (60% kcal derived from fat, Research Diets; D12492) or a control LFD (10% kcal derived from fat, Research Diets; D12450B). HFD was provided for a period of 12 wk. For the LFD and HFD groups, sera were harvested from overnight-fasted animals. All animal experiments were conducted according to the National Institutes of Health “Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Serum cytokine profiling.

Mouse blood samples were harvested by tail vein bleed and separated using Microvette CB 300 (The SARSTEDT Group, Numbrecht, Germany). Serum samples (n = 10–12 mice per group) were analyzed using a Luminex instrument (Luminex, Austin, TX) and XPonent 3.1 Software (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Assays for 71 mouse cytokines (covering the majority of the known cytokines) were performed using a Luminex bead-based multiplex system, according to manufacturer's protocol (EMD Millipore). All of the available cytokine assays provided by Millipore were included. Five separate multiplex assays, based on the known dynamic range of each cytokine, were carried out to cover all 71 cytokines. Some of the cytokines' receptors are synthesized in membrane-bound form, and proteolytic cleavage generates a soluble version that circulates in plasma. Thus, sCD30, sIL-1RI, sIL-1RII, sIL-2Rα, sIL-4R, sIL-6R, soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR)I, sTNFRII, soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 (VEGFR1), sVEGFR2, sVEGFR3, sgp130, and soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) were also measured as part of the 71 cytokines profiled. Standards were provided for each mouse cytokine, from which standard curves were generated. Concentrations were determined for each of the 71 mouse cytokines relative to an appropriate six-point regression standard curve, in which the mean fluorescence for each cytokine standard was transformed into known concentrations (pg/ml or ng/ml). We assigned the lowest measurable value (3.2 pg/ml) to any sample below the detection limit of the assay.

Stereotaxic cannulation and food intake measurements.

A unilateral cannula was implanted into the lateral ventricle of 10-wk-old male C57BL/6J mice, as previously described (15, 16). After recovery from surgery, the correct placement of the cannula was confirmed by intracerebroventricular infusion of neuropeptide Y (NPY; 1 nmol/2 μl; American Peptide). Food intake was measured during the light cycle for 1 h, and placement of the cannula was confirmed when the animals consumed 100% more food during the 1-h food intake test, relative to animals given a saline injection. Only mice that passed the cannula placement test were used for functional study. One week later, food intake was measured after animals received an intracerebroventricular infusion (2 μl) of recombinant G-CSF (n = 6 mice, 0.2 μg/μl), IL-22 (n = 5 mice, 0.83 μg/μl), or control buffer (saline; n = 8–10 mice).

Indirect calorimetry.

To assess metabolic alterations after central administration of G-CSF, differences in energy expenditure and usage of fat and carbohydrate fuels were determined as previously described (14, 64). Briefly, mice were adapted to metabolic chambers 3 days before the start of the experiment, with data acquisition for 24 h after intracerebroventricular injection of G-CSF (n = 10) or control (n = 10). Mice were provided ad libitum access to water and standard laboratory chow and were individually housed in indirect calorimeter chambers (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH). Oxygen and carbon dioxide levels were sampled in each chamber every 15 min. Oxymax software (v. 4.03) was used to calculate the respiratory exchange ratio (RER = V̇co2/V̇o2). The rate of energy expenditure (EE, kcal/kg lean mass/h) was estimated by multiplying the caloric value (CV: 3.815 + [1.232 × RER]) by V̇o2. Data are reported as an average over 1 or 4 h after injection for each subject.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis.

The hypothalamus was dissected using the anterior commissure and the oculomotor nerve as neuroanatomical markers. Tissue was stored in RNALater (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) at −80°C until RNA was extracted and quantified, as previously described (17). Other tissues (liver, skeletal muscle, and epididymal white adipose tissue) were harvested, snap-frozen, and stored at −80°C until RNA was extracted. A separate cohort of fasted and refed male mice was used for the isolation of immune cells. Retro-orbital bleeding enables greater volumes of blood to be collected compared with tail bleed, thus allowing greater numbers of circulating immune cells to be isolated. For this reason, blood was collected from the retro-orbital plexus and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm (2,000 g) for 15 min at room temperature to separate the circulating immune cells (lymphocytes, monocytes, neutrophils, and basophils) from the serum. Ack lysing buffer (Quality Biologicals, Gaithersburg, MD) was added to lyse the red blood cells on ice for 5 min with occasional shaking; for every 0.5 ml of blood, 5 ml of Ack lysing buffer were added. 15 ml of PBS were added to stop the reaction, and immune cells were pelleted at 300–400 g for 5 min at 4°C. All RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or the RNeasy Midi kits (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Random primers and Superscript II (Invitrogen) or Goscript (Promega, Madison, WI) reverse transcriptase were used to generate cDNA. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis (SYBR Green PCR master mix, Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) generated a Ct value for the threshold cycle of each sample. The data were normalized to β2 microglobulin (B2M), β-actin, or 36B4 [also known as acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein P0 (RPLP0)] to generate a ΔCt value, and then a ΔΔCt was obtained by normalizing the data to the mean ΔCt of the control group (68). In general, housekeeping genes with the least variation across tissue samples were used. For most tissues, expression levels of 36B4 were used for normalization. All primers used for real-time PCR analyses are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used in real-time PCR analysis

| Gene | Forward primer (5′ to 3′) | Reverse primer (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| g-Csf | ATGGCTCAACTTTCTGCCCAG | CTGACAGTGACCAGGGGAAC |

| Il-22 | ATGAGTTTTTCCCTTATGGGGAC | GCTGGAAGTTGGACACCTCAA |

| Il-16 | AAGAGCCGGAAATCCACGAAA | GTCTCAAAAGGGTCAGGGTACT |

| Il-1α | GCACCTTACACCTACCAGAGT | AAACTTCTGCCTGACGAGCTT |

| Il-1β | GTGGCTGTGG AGAAGCTGTG | GAAGGTCCACGGGAAAGACAC |

| Cxcl1 | CTGGGATTCACCTCAAGAACATC | CAGGGTCAAGGCAAGCCTC |

| Il-1R1 | GTGCTACTGGGGCTCATTTGT | GGAGTAAGAGGACACTTGCGAAT |

| Il-2Rα | AACCATAGTACCCAGTTGTCGG | TCCTAAGCAACGCATATAGACCA |

| Vegf3 | CTGGCAAATGGTTACTCCATGA | ACAACCCGTGTGTCTTCACTG |

| Lcn2 | TGGCCCTGAGTGTCATGTG | CTCTTGTAGCTCATAGATGGTGC |

| Ptx3 | CCTGCGATCCTGCTTTGTG | GGTGGGATGAAGTCCATTGTC |

| Timp-1 | GCAACTCGGACCTGGTCATAA | CGGCCCGTGATGAGAAACT |

| Sap | AGACAGACCTCAAGAGGAAAGT | AGGTTCGGAAACACAGTGTAAAA |

| Cd30 | CCTTCCCAACGGATCGACC | CCCGTCTTCATTGACGTAGTAGT |

| Il-12p40 | TGGTTTGCCATCGTTTTGCTG | ACAGGTGAGGTTCACTGTTTCT |

| Ccl12 | ATTTCCACACTTCTATGCCTCCT | ATCCAGTATGGTCCTGAAGATCA |

| Cx3cl1 | ACGAAATGCGAAATCATGTGC | CTGTGTCGTCTCCAGGACAA |

| Ccl4 | TTCCTGCTGTTTCTCTTACACCT | CTGTCTGCCTCTTTTGGTCAG |

| Ccl20 | CGTCATCCATGGCGAACTG | GCTTCTTTGCAGCTCCTTCGT |

| Rage | CTTGCTCTATGGGGAGCTGTA | GGAGGATTTGAGCCACGCT |

| Saa-3 | TGCCATCATTCTTTGCATCTTGA | CCGTGAACTTCTGAACAGCCT |

| Haptoglobin | GCTATGTGGAGCACTTGGTTC | CACCCATTGCTTCTCGTCGTT |

| A2M | AGATGGTGAGATTTCGTGTTGTC | ACGGTCCTGCCTGATTCTGTA |

| Npy | ATGCTAGGTA ACAAGCGAATGG | TGTCGCAGAGCGGAGTAGTAT |

| Agrp | ATGCTAGGTAACAAGCGAATGG | CAGACTTAGACC TGGGAACTCT3 |

| Pomc | TGCCGAGATTCTGCTACAG | TGCTGCTGTTCCTGGGGC |

| Cart | CCCGAGCCCTGGACATCTA | G CTTCGATCTGCAACATAGCG |

| β2M | TTCTGGTGCTTG TCTCACTGA | CAGTATGTTCGGCTTCCCATTC |

| 36B4 | AGATTCGGGATATGCTGTTGGC | TCGGGTCCTAGACCAGTGTTC |

| β-actin | GGCACCACACCTTCTACAATG | GGGGTGTTGAAGGTCTCAAAC |

Statistical analysis.

Statistical tests used to determine differences between groups were one-way ANOVA, Student's t-test, or Mann-Whitney U-test. The nonparametric Mann-Whitney U-test was used on serum cytokine profiling data that did not pass the D'Agostino and Pearson omnibus normality test. P < 0.05 was considered significant. The values reported in the figures represent means ± SE. Data were analyzed and graphed using Statistica (v. 8.0 software) and/or GraphPad Prism 6 software.

RESULTS

Serum cytokine profiling in fasted and refed mice.

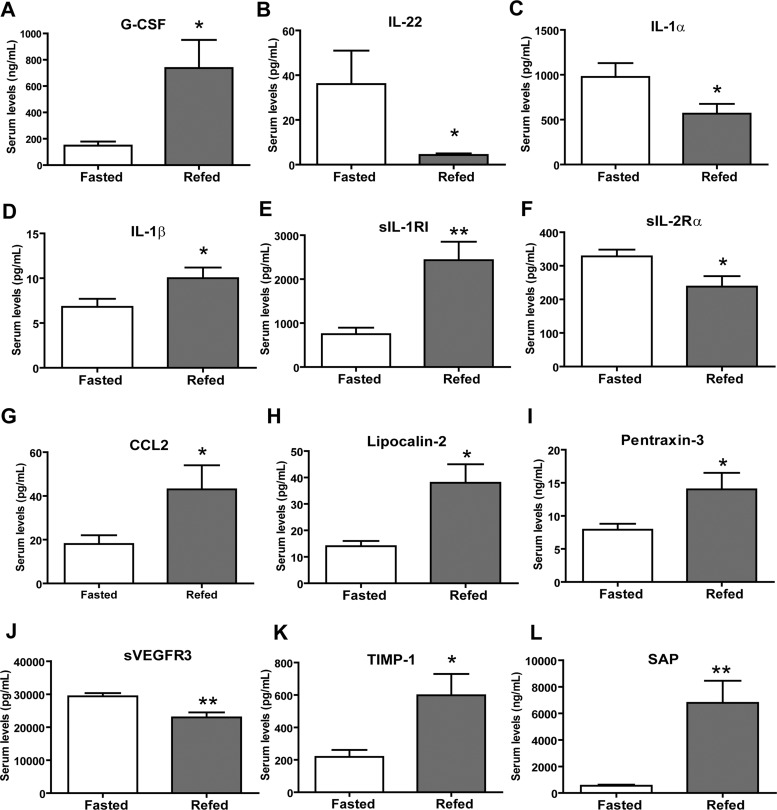

To identify cytokines that may modulate pathways associated with altered energy balance or food intake, we examined changes in circulating cytokines in response to fasting and refeeding. On the basis of the established interplay between the immune and the endocrine systems and the fact that cytokines can modulate metabolic function directly and/or indirectly, we hypothesized that cytokines with altered circulating levels following acute changes in whole body metabolism may have metabolic roles. For our cytokine profiling, serum was harvested from mice fasted for 12 h and from mice fasted for 12 h followed by 2 h of refeeding (regular chow pellets). An ad libitum group was not included in the study due to the randomness and variability of food intake. Cytokine profiling was carried out using a bead-based Luminex multiplex system, which enabled simultaneous quantification of a large number of cytokines (23). Of the 71 mouse cytokines measured, 67 were reliably detected (Table 2). Four cytokines—IL-3 (<3.2 pg/ml), IL-21 (<9.8 pg/ml), IL-23 (<3.2 pg/ml), and leukemia inhibitory factor (<3.2 pg/ml)—were consistently below the assay detection limits and, therefore, are not included in the final profiles. We observed significant changes in the serum concentrations of 12 cytokines between the fasted and refed groups. Specifically, circulating levels of eight cytokines [G-CSF, IL-1β, CCL2, sIL-1RI, lipocalin-2, pentraxin-3, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP)-1, and serum amyloid protein (SAP)] were higher, and 4 cytokines (IL-22, IL-1α, sIL-2Rα, and sVEGFR3) were lower, in fasted vs. refed mice (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Summary of serum cytokine levels in fasted and refed states

| Fasted | Refed | P Value | Cytokine | Fasted | Refed | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokines | |||||||

| sCD30 | 71 ± 48 | 31 ± 10 | 0.43 | IL-17 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 0.13 |

| sgp130 | 414 ± 47 | 310 ± 35 | 0.09 | IL-20 | 16 ± 0.1 | 15.8 ± 0.2 | 0.33 |

| IFN-γ | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 4 ± 0.5 | 0.07 | IL-22* | 36 ± 15 | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 0.01 |

| IL-1α* | 976 ± 155 | 567 ± 109 | 0.04 | IL-25 | 1476 ± 986 | 128 ± 75 | 0.22 |

| IL-1β* | 6.8 ± 0.9 | 10 ± 1.2 | 0.04 | IL-27 | 12 ± 4.4 | 20 ± 8 | 0.35 |

| IL-2 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 0.36 | IL-28B | 214 ± 26 | 235 ± 16 | 0.49 |

| IL-4 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 0.72 | IL-33 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 1 | 0.51 |

| IL-5 | 12 ± 5 | 8.9 ± 1 | 0.64 | sIL-1RI** | 749 ± 147 | 2430 ± 420 | 0.001 |

| IL-6 | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 30 ± 13 | 0.30 | sIL-1RII | 9852 ± 207 | 9038 ± 405 | 0.09 |

| IL-7 | 57 ± 54 | 5.2 ± 1.9 | 0.35 | sIL-2Rα* | 328 ± 20 | 238 ± 31 | 0.02 |

| IL-9 | 45 ± 5 | 69 ± 17 | 0.19 | sIL-4R | 2300 ± 248 | 3008 ± 402 | 0.15 |

| IL-10 | 3.3 ± 0.6 | 3.4 ± 0.6 | 0.95 | sIL-6R | 7895 ± 588 | 7438 ± 515 | 0.56 |

| IL-12p40 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 5.4 ± 1.7 | 0.63 | PTX-3* | 7.9 ± 0.9 | 14 ± 2.5 | 0.03 |

| IL-12p70 | 7.2 ± 2 | 9 ± 3.3 | 0.64 | TNF-α | 2 ± 0.3 | 2 ± 0.4 | 0.97 |

| IL-13 | 74 ± 15 | 63 ± 11 | 0.72 | sTNFRI | 4609 ± 374 | 3729 ± 257 | 0.05 |

| IL-15 | 5.3 ± 2.1 | 6.2 ± 3 | 0.80 | sTNFRII | 3065 ± 195 | 3157 ± 240 | 0.77 |

| IL-16 | 5600 ± 1053 | 11626 ± 2389 | 0.14 | ||||

| Chemokines | |||||||

| CCL11 | 421 ± 32 | 466 ± 23 | 0.27 | CCL19 | 31 ± 6 | 25 ± 4 | 0.41 |

| CCL12 | 34 ± 6 | 43 ± 5 | 0.25 | CXCL2 | 53 ± 12 | 54 ± 14 | 0.96 |

| CCL21 | 1511 ± 251 | 1584 ± 111 | 0.79 | CCL22 | 11 ± 1 | 10 ± 0.4 | 0.42 |

| CX3CL1 | 1220 ± 200 | 1125 ± 93 | 0.67 | CXCL9 | 58 ± 9 | 37 ± 5 | 0.13 |

| CXCL1 | 77 ± 7 | 144 ± 29 | 0.12 | CCL2* | 18 ± 4 | 43 ± 11 | 0.03 |

| CXCL10 | 110 ± 6 | 113 ± 8 | 0.74 | CCL20 | 22 ± 3 | 18 ± 4 | 0.40 |

| CXCL5 | 12464 ± 1734 | 11492 ± 826 | 0.61 | CCL5 | 22 ± 3 | 20 ± 3 | 0.67 |

| CCL3 | 43 ± 7 | 38 ± 7 | 0.64 | CCL17 | 29 ± 2 | 37 ± 4 | 0.11 |

| CCL4 | 31 ± 6 | 25 ± 4 | 0.41 | ||||

| Growth and Differentiation Factors | |||||||

| G-CSF* | 148 ± 31 | 737 ± 214 | 0.01 | VEGF | 17 ± 10 | 5 ± 2.6 | 0.25 |

| GM-CSF | 14 ± 4 | 16 ± 5 | 0.69 | sVEGFR1 | 1802 ± 191 | 1706 ± 168 | 0.71 |

| M-CSF | 244 ± 169 | 52 ± 22 | 0.28 | sVEGFR2 | 32082 ± 1925 | 24481 ± 2567 | 0.07 |

| TIMP-1* | 218 ± 43 | 598 ± 132 | 0.01 | sVEGFR3** | 29352 ± 972 | 22954 ± 1513 | 0.002 |

| Other Cytokines | |||||||

| sRAGE | 135 ± 63 | 52 ± 12 | 0.21 | AGP | 0.1 ± 0 | 5.5 ± 5.5 | 0.33 |

| Lipocalin-2* | 14 ± 2 | 38 ± 7 | 0.01 | A2M | 499 ± 85 | 751 ± 267 | 0.38 |

| SAA-3 | 52 ± 3.3 | 293 ± 165 | 0.16 | Haptoglobin | 20 ± 4 | 19 ± 8 | 0.86 |

| Adipsin | 21 ± 0.9 | 21 ± 0.6 | 0.68 | SAP** | 548 ± 79 | 6788 ± 1663 | 0.001 |

| CRP | 11 ± 1 | 10 ± 0.5 | 0.33 | ||||

Except for A2M, adipsin, AGP, haptoglobin, SAP, PTX3, and SAA-3 (ng/ml), all other values are in pg/ml.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.005.

Fig. 1.

Fasting and refeeding alters serum cytokine levels in mice. A–L: serum cytokine levels of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), IL-22, IL-1α, IL-1β, secreted IL-1 receptor type 1 (sIL-1RI), soluble IL-2 receptor α chain (sIL-2Rα), chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2), lipocalin-2, pentraxin-3, soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (sVEGFR3), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1), and serum amyloid protein (SAP) in fasted and refed mice. Data are expressed as means ± SE (n = 10 per group) *P < 0.05; **P < 0.005.

Fasting and refeeding alter the expression of cytokine mRNA.

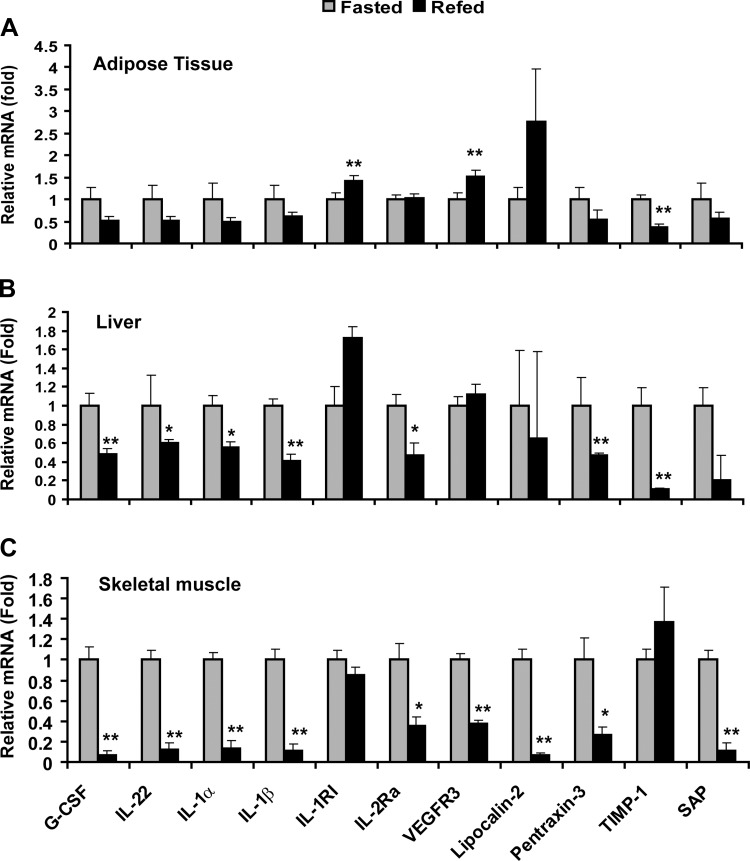

We performed real-time PCR analysis to determine whether the observed changes in circulating cytokine levels after fasting and refeeding were due to altered mRNA expression. While cytokines can be produced by a variety of cell types, we focused our analysis on immune cells, as well as the three major metabolic tissues—adipose tissue, liver, and skeletal muscle. While the patterns of relative mRNA expression of IL-22, IL-1α, and IL-1RI in adipose, liver, and/or skeletal muscle parallels their circulating levels (Fig. 2), opposing changes in relative mRNA expression were observed for G-CSF, IL-β, VEGFR3, pentraxin-3, and SAP compared with their serum levels (Fig. 2). We failed to detect any significant changes in cytokine transcript levels in total blood-derived immune cells (lymphocytes, monocytes, neutrophils, and basophils) in response to fasting and refeeding; in most cases, the expression of cytokine mRNA in immune cells was very low (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Fasting and refeeding alters cytokine mRNA expression. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of relative cytokine expression in adipose tissue (A), liver (B), and skeletal muscle (C). Expression levels were normalized to 36B4. Data shown are expressed as means ± SE (n = 10 per group) *P < 0.05; **P < 0.005.

Centrally delivered cytokines have opposing effects on food intake and body weight.

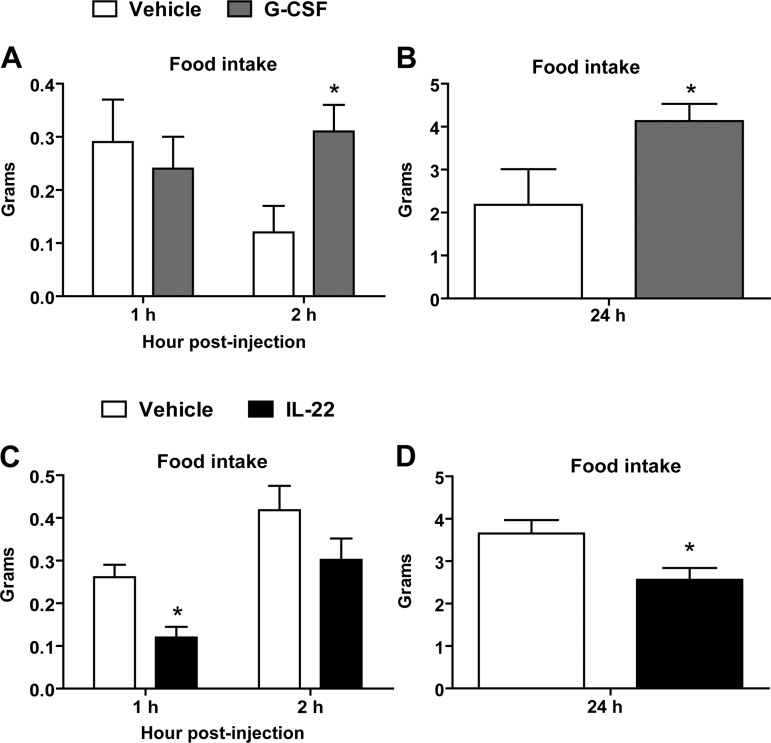

To investigate whether any of the cytokines regulated by fasting and/or refeeding are capable of modulating food intake and energy balance, we selected G-CSF and IL-22 for further functional studies based on three key findings. First, G-CSF is a member of the colony-stimulating factor family, of which a related protein, GM-CSF, has been shown to act in the CNS to modulate food intake (66). IL-22 belongs to the interleukin family, and several interleukins (IL-1, IL-6, and IL-18) have been shown to modulate food intake (37, 41, 49, 70, 83, 86). Second, we found that circulating levels of G-CSF and IL-22 were markedly (and reciprocally) altered by fasting and refeeding, leading us to believe that they might have opposing effects on food intake. Third, G-CSF produced in the periphery is known to cross the blood-brain barrier, and its receptor is expressed throughout the CNS (69, 84), giving it the potential to act in the CNS to modulate food intake. On the basis of these observations, we hypothesized that G-CSF and IL-22 may play a role in CNS to modulate ingestive physiology. To test this, we delivered recombinant G-CSF, IL-22, or control buffer into the lateral ventricle of cannulated mice, since protein delivered into the lateral ventricle has been shown to diffuse rapidly throughout the CNS (61). The 0.2 μg/μl dose of G-CSF increased food intake relative to control mice at 2 and 24 h after intracerebroventricular injection (Fig. 3, A and B). Increased food intake resulted in a very modest increase in body weight 24 h after central delivery of G-CSF (data not shown). Central administration of a lower dose of G-CSF (0.1 μg/μl) demonstrated only a trend for increased food intake (data not shown). In contrast, administration of recombinant IL-22 had the opposite effect and decreased food intake at 1 and 24 h after intracerebroventricular injection (Fig. 3, C and D).

Fig. 3.

Alterations in food intake after central injection of G-CSF or IL-22. Intracerebroventricular administration of G-CSF increased food intake at 2 h (A) and 24 h (B). Central delivery of IL-22 decreased food intake at 1 h (C) and reduced cumulative food intake at 24 h (D). Data are shown as means ± SE (n = 8–10 for saline control; n = 6 for G-CSF; n = 5 for IL-22). *P < 0.05.

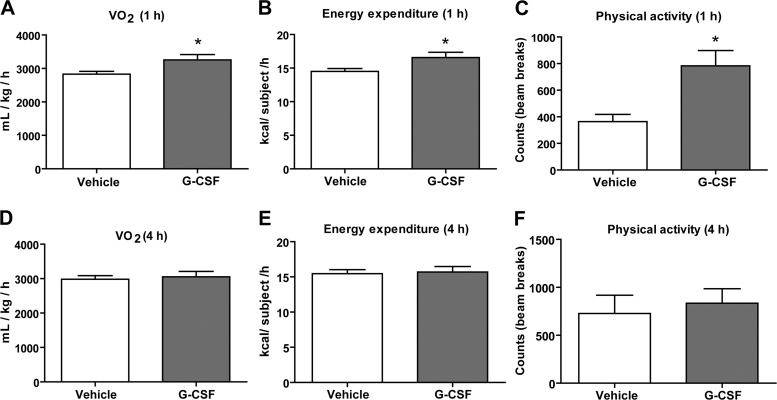

Central administration of G-CSF transiently increases energy expenditure and physical activity.

All cytokines known to modulate food intake have been shown to decrease caloric intake (26, 49, 66, 70, 86). To better understand how central delivery of G-CSF increased food intake, we measured changes in whole body metabolism and hypothalamic neuropeptide gene expression. Central administration of G-CSF induced an acute and transient (lasting 1 h) increase in V̇o2 and energy expenditure (Fig. 4, A and B). However, at 4 h after intracerebroventricular injection, mice that received G-CSF were not different from saline-injected controls (Fig. 4, D and E). Total physical activity levels were measured by laser beam breaks across the cage floor. We also observed a transient increase in physical activity of mice at 1 h after intracerebroventricular injection of G-CSF (Fig. 4C). These alterations in metabolism and physical activity preceded the increase in food intake, suggesting that the mechanism for increased food intake may be associated with transient changes in metabolic rate and energy expenditure.

Fig. 4.

Central delivery of G-CSF increases whole body metabolism and physical activity levels. Central administration of G-CSF had an acute and transient effect on whole body metabolism and physical activity. V̇o2 (A), energy expenditure (B), and physical activity levels (C) were increased at 1 h following intracerebroventricular delivery of G-CSF. V̇o2 (D), energy expenditure (E), and physical activity (F) levels were not different between the groups at 4 h. Data shown are means ± SE (n = 10 for saline control; n = 10 for G-CSF). *P < 0.05.

Effects of G-CSF on hypothalamic neuropeptide gene expression.

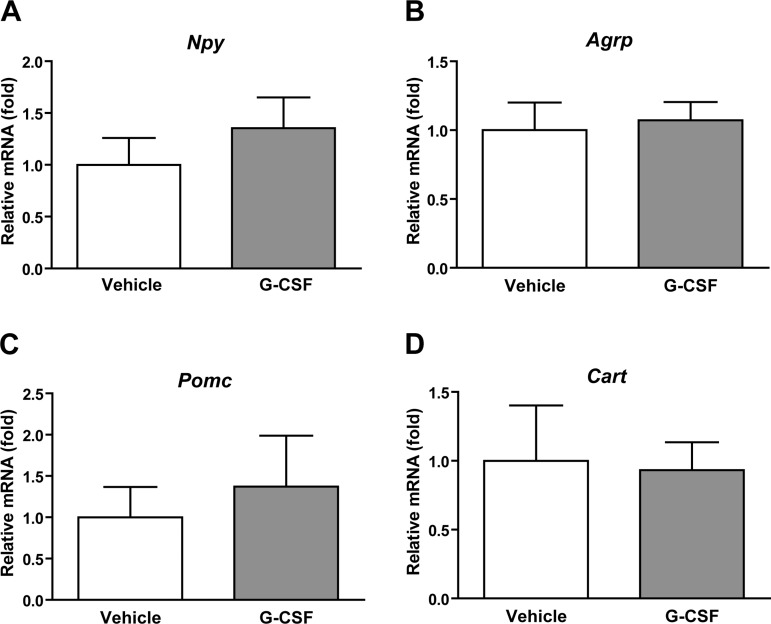

To determine whether the mechanism of increased food intake was driven by alterations in hypothalamic neuropeptide gene expression, we measured the mRNA levels of orexigenic (Npy and Agrp) and anorexigenic (Pomc and Cart) neuropeptide genes associated with food intake regulation (71). We observed no significant changes in neuropeptide gene expression in the hypothalamus 3 h after intracerebroventricular delivery of G-CSF (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effects of G-CSF on hypothalamic neuropeptide gene expression. Real-time PCR analyses of neuropeptide gene expression in the hypothalamus at 3 h after intracerebroventricular delivery of G-CSF. Expression level was normalized to β2 microglobulin level in each sample. Npy, neuropeptide Y (A); Agrp, agouti-related peptide (B); Pomc, proopiomelanocortin (C); Cart, cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (D). Data shown are means ± SE (n = 5).

Serum cytokine profiling in mice fed a low-fat diet or a high-fat diet.

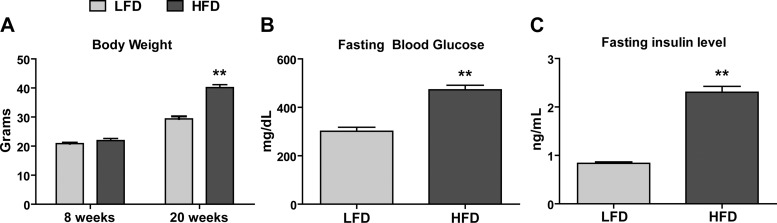

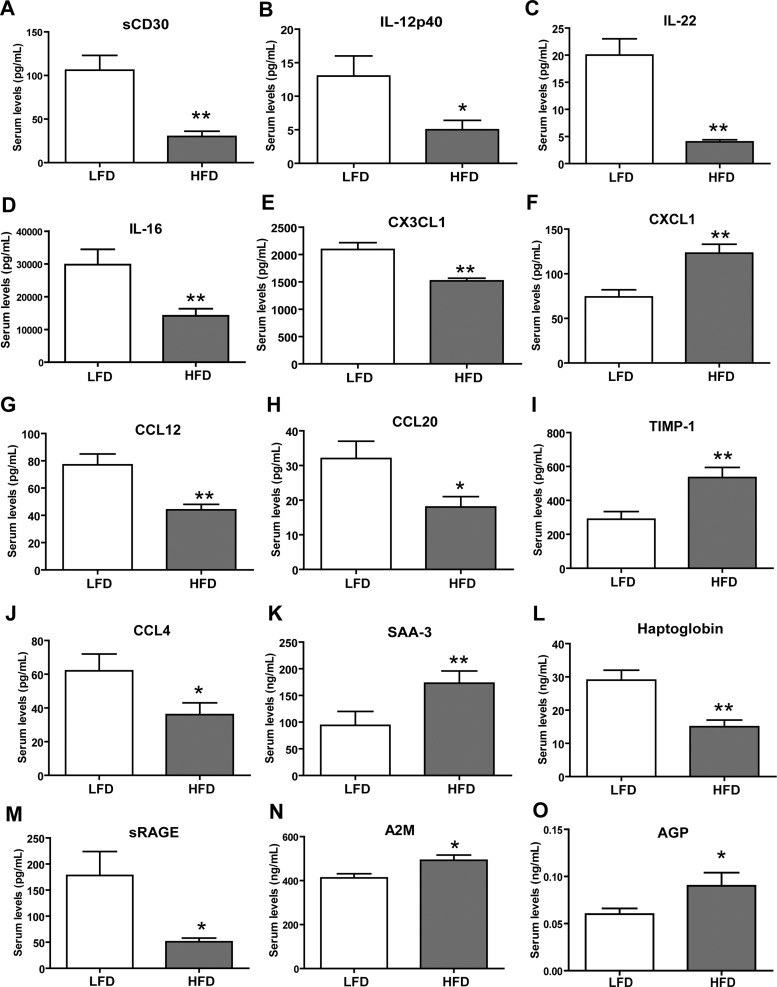

To identify cytokines that may modulate pathways associated with chronic excess caloric intake, as in obesity, we examined changes in circulating cytokines in response to a low-fat diet (LFD) or a high-fat diet (HFD). As expected, HFD-fed mice had significantly greater body weights (Fig. 6A) and were insulin resistant, as indicated by marked increase in fasting blood glucose and insulin levels (Fig. 6, B and C). Cytokine profiling was carried out as described for the fasted and refed group. As before, of the 71 mouse cytokines measured, 67 were reliably detected (Table 3). We observed significant changes in the serum concentrations of 15 cytokines between the LFD-fed and HFD-fed groups. Specifically, HFD-fed mice had higher circulating levels of five cytokines [CXCL1, TIMP-1, serum amyloid protein A3 (SAA-3), alpha-2-macroglobulin (A2M), and α1-acid glycoprotein (AGP)], and 10 cytokines [sCD30, IL-12p40, IL-22, IL-16, CX3CL1, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 12 (CCL12), CCL20, CCL4, haptoglobin, and sRAGE] were lower compared with the LFD-fed control mice (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Body weight, fasting glucose, and insulin levels in mice fed a low-fat diet (LFD) or a high-fat diet (HFD). A: body weight of LFD-fed and HFD-fed mice at 8 and 20 wk old. B: fasting blood glucose of LFD-fed and HFD-fed mice (20 wk old). C: fasting insulin levels of LFD-fed and HFD-fed mice (20 wk old). Data shown are means ± SE (n = 12 per group). **P < 0.01.

Table 3.

Summary of serum cytokine levels in mice fed a low-fat diet or a high-fat diet

| LFD | HFD | P Value | Cytokine | LFD | HFD | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokines | |||||||

| sCD30** | 106 ± 17 | 30 ± 6 | 0.0001 | IL-17 | 10 ± 5 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 0.17 |

| sgp130 | 549 ± 96 | 461 ± 77 | 0.48 | IL-20 | 16 ± 0.2 | 23 ± 5 | 0.21 |

| IFN-γ | 7.4 ± 2 | 4.2 ± 1 | 0.17 | IL-22** | 20 ± 3 | 4 ± 0.4 | 0.0001 |

| IL-1α | 812 ± 173 | 903 ± 134 | 0.68 | IL-25 | 983 ± 141 | 644 ± 116 | 0.08 |

| IL-1β | 30 ± 17 | 10 ± 1 | 0.27 | IL-27 | 16 ± 4 | 20 ± 5 | 0.55 |

| IL-2 | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 0.44 | IL-28B | 273 ± 31 | 295 ± 31 | 0.61 |

| IL-4 | 6.4 ± 4.4 | 2 ± 0.4 | 0.33 | IL-33 | 7 ± 2.4 | 2 ± 1 | 0.20 |

| IL-5 | 18 ± 5 | 13 ± 2 | 0.47 | sIL-1RI | 814 ± 173 | 596 ± 59 | 0.25 |

| IL-6 | 13 ± 5 | 9 ± 1 | 0.39 | sIL-1RII | 11153 ± 280 | 10328 ± 633 | 0.25 |

| IL-7 | 8 ± 3 | 3 ± 0.3 | 0.15 | sIL-2Rα | 348 ± 27 | 470 ± 141 | 0.41 |

| IL-9 | 68 ± 16 | 88 ± 20 | 0.44 | sIL-4R | 3043 ± 418 | 2083 ± 226 | 0.06 |

| IL-10 | 18 ± 10 | 8 ± 2 | 0.33 | sIL-6R | 8641 ± 383 | 8179 ± 864 | 0.63 |

| IL-12p40* | 13 ± 3 | 5 ± 1.4 | 0.01 | PTX-3 | 11 ± 1.3 | 15 ± 2.5 | 0.15 |

| IL-12p70 | 16 ± 5 | 13 ± 3 | 0.66 | TNF-α | 8 ± 3.2 | 4 ± 0.5 | 0.19 |

| IL-13 | 114 ± 10 | 175 ± 63 | 0.35 | sTNFRI | 6596 ± 639 | 6260 ± 412 | 0.66 |

| IL-15 | 17 ± 8 | 6 ± 2 | 0.22 | sTNFRII | 3836 ± 261 | 4727 ± 450 | 0.10 |

| IL-16** | 29785 ± 4681 | 14150 ± 2183 | 0.006 | ||||

| Chemokines | |||||||

| CCL11 | 623 ± 34 | 657 ± 17 | 0.39 | CXCL2 | 85 ± 13 | 82 ± 25 | 0.90 |

| CCL12** | 77 ± 8 | 44 ± 4 | 0.001 | CCL19 | 121 ± 14 | 84 ± 17 | 0.11 |

| CCL21 | 2888 ± 479 | 2533 ± 181 | 0.50 | CCL22 | 19 ± 3 | 15 ± 1.4 | 0.31 |

| CX3CL1** | 2090 ± 125 | 1518 ± 48 | 0.005 | CXCL9 | 129 ± 23 | 150 ± 25 | 0.54 |

| CXCL1** | 74 ± 8 | 123 ± 10 | 0.001 | CCL2 | 54 ± 19 | 49 ± 6 | 0.81 |

| CXCL10 | 152 ± 18 | 181 ± 19 | 0.27 | CCL20* | 32 ± 5 | 18 ± 3 | 0.01 |

| CXCL5 | 8481 ± 1007 | 10268 ± 1083 | 0.24 | CCL5 | 22 ± 3 | 20 ± 3 | 0.67 |

| CCL3 | 43 ± 8 | 52 ± 7 | 0.38 | CCL17 | 56 ± 7 | 44 ± 5 | 0.15 |

| CCL4* | 62 ± 10 | 36 ± 7 | 0.03 | ||||

| Growth and Differentiation Factors | |||||||

| G-CSF | 396 ± 71 | 292 ± 54 | 0.25 | VEGF | 12 ± 3 | 17 ± 9 | 0.62 |

| GM-CSF | 20 ± 7 | 16 ± 4 | 0.56 | sVEGFR1 | 2003 ± 330 | 1656 ± 123 | 0.35 |

| M-CSF | 689 ± 372 | 190 ± 119 | 0.22 | sVEGFR2 | 28350 ± 1991 | 28960 ± 1776 | 0.82 |

| TIMP-1** | 289 ± 45 | 535 ± 59 | 0.004 | sVEGFR3 | 30035 ± 1081 | 30228 ± 1417 | 0.92 |

| Other Cytokines | |||||||

| sRAGE* | 178 ± 46 | 51 ± 7 | 0.03 | A2M* | 412 ± 19 | 492 ± 24 | 0.02 |

| Lipocalin-2 | 24 ± 3 | 28 ± 4 | 0.39 | Haptoglobin** | 29 ± 3 | 15 ± 2 | 0.002 |

| SAA-3** | 94 ± 26 | 173 ± 23 | 0.003 | SAP | 1126 ± 386 | 770 ± 152 | 0.40 |

| Adipsin | 20 ± 0.6 | 20 ± 0.8 | 0.96 | CRP | 11 ± 1 | 10 ± 0.2 | 0.33 |

| AGP | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 0.03 | ||||

Except for A2M, adipsin, AGP, haptoglobin, SAP, PTX3, and SAA-3 (ng/ml), all other values are pg/ml.

LFD, low-fat diet; HFD, high-fat diet.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.005.

Fig. 7.

High-fat feeding alters serum cytokine levels in mice. Serum cytokine levels of soluble CD30 (sCD30) (A), IL-12p40 (B), IL-22 (C), IL-16 (D), CX3CL1 (E), CXCL1 (F), CCL12 (G), CCL20 (H), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) (I), CCL4 (J), serum amyloid A-3 (SAA-3) (K), haptoglobin (L), soluble receptor of advanced glycation end-products (sRAGE) (M), A2M (N), and α1-acid glycoprotein (AGP) (O) in mice fed a LFD or a HFD. Data shown are means ± SE (n = 12 per group). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.005.

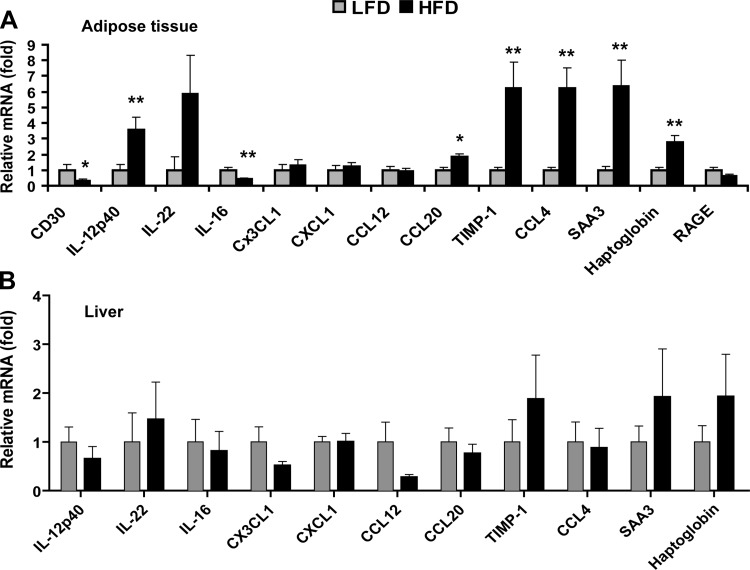

High-fat feeding alters the expression of cytokine mRNA.

To determine whether the observed changes in circulating cytokine levels in HFD-fed mice were due to changes in mRNA expression, we performed real-time PCR analysis on adipose tissue and liver, which are infiltrated with macrophages and Kupffer cells, respectively, in the obese state. The relative mRNA expression patterns of CD30, IL-16, TIMP-1, and SAA3 in adipose tissue parallel the circulating levels, whereas opposing patterns of mRNA (in adipose tissue) and serum levels were observed for IL-12p40, IL-22, CCL20, CCL4, and haptoglobin (Fig. 8A). The expression for this same set of cytokines in liver tissue was not statistically different between the LFD-fed and HFD-fed mice (Fig. 8B). The mRNA expression of Cd30 and Rage was below detection levels in the liver (not shown).

Fig. 8.

High-fat feeding alters cytokine mRNA expression. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of cytokine expression in adipose tissue (A) and liver (B) of mice fed an HFD or an LFD. Expression levels were normalized to 36B4 in adipose and liver. Expression levels in liver were normalized to β-actin. Data shown are means ± SE (n = 7–12 per group). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

We performed a comprehensive analysis of serum cytokine levels in response to fasting and refeeding and high-fat feeding. Strikingly, circulating levels of 12 cytokines (∼18% of those tested) were significantly altered in response to refeeding following an overnight fast, reflecting acute changes in whole body metabolism. Given that we only examined changes in cytokine profiles after 2 h of refeeding, it is conceivable that greater changes in circulating cytokine levels might be observed if additional refeeding time points were to be sampled. Interestingly, the changes that we observed in circulating cytokine levels were not due to acute transcriptional changes in cytokine mRNA in tissues with high metabolic activity, such as the white adipose, liver, and skeletal muscle. We also failed to detect any significant changes in cytokine transcript levels in total immune cells derived from blood.

Given that only a few cytokines had transcript expression patterns that correlated with their serum levels, our results suggest that both transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms are likely involved in controlling circulating cytokine levels in response to refeeding, as is the case for many cytokines (2). Several posttranscriptional mechanisms have been shown to regulate cytokine expression, specifically by modulating mRNA stability through the interaction between RNA-binding proteins and the AU-rich elements located in the 3′ UTR of cytokine transcripts (2, 18). microRNA (miRNA)-mediated suppression of mRNA translation has also been shown to affect cytokine expression (3). Mechanisms such as these may be employed in controlling the spatial and temporal expression of cytokines in response to metabolic alterations.

Of the 12 cytokines whose levels were altered by fasting and refeeding, we functionally characterized two. We showed that central delivery of G-CSF increased, whereas IL-22 decreased, food intake. The increase in food intake appeared to be independent of acute changes in hypothalamic neuropeptide gene expression (Fig. 5). Given that other brain regions are also involved in food intake regulation (30, 31, 34, 35), such as the hindbrain where G-CSF receptor is also expressed, it is possible that G-CSF acts on neurons in these locations to modulate food intake. While the local concentrations of G-CSF and IL-22 in the CNS are not known, the dose of G-CSF injected centrally was comparable to its typical circulating level and, hence, within physiological range. In contrast, the dose of IL-22 injected centrally was far greater than its typical circulating level. Future dose-response studies are needed to determine whether the effects of G-CSF and IL-22 on food intake are physiological and not merely pharmacological in nature. Whether G-CSF or IL-22 truly plays a role in food intake regulation can only be established using mouse models with selective deletion of G-CSF or IL-22 receptor in the CNS. Future studies will establish whether the other 10 cytokines that were altered by fasting and refeeding have a central and/or a peripheral metabolic role.

Of the cytokines examined, 15 (22%) had altered circulating levels following chronic high-fat feeding, and six (IL-12p40, sCD30, SAA-3, CCL12, IL-16, and A2M) have not been previously associated with obesity; these cytokines and acute-phase proteins may be considered candidate serum markers for adiposity and other related metabolic parameters in humans. Similar to our observations in the fasted and refed states, transcriptional changes in cytokine mRNA expression only partly account for the observed changes in serum cytokine levels in HFD-fed vs LFD-fed mice (Fig. 8). This suggests that both transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms are likely involved in controlling circulating cytokine levels in response to chronic metabolic stress, resulting from dietary manipulations (2). Alternatively, feedback control may account for the discordance in mRNA and protein patterns for some of the cytokines. Because we only examined adipose tissue and liver for cytokine mRNA expression in HFD-fed mice, it may be that other tissues and cells are responsible for the chronic changes in circulating cytokine levels.

In mice fed an HFD, serum levels of IL-22, TIMP-1, sRAGE, haptoglobin, CCL20, CCL4, and CXCL1 were also significantly altered relative to mice fed an LFD. These cytokines and acute-phase proteins have been previously shown to be associated with human obesity. However, in most cases, it is far from clear whether alterations in plasma levels of these cytokines are a consequence of metabolic dysregulation or whether they are causally linked to obesity and Type 2 diabetes. In humans, plasma levels of IL-22 are elevated in Type 2 diabetes (85), and IL-22 secreted by T lymphocytes has been shown to exacerbate adipose tissue inflammation (22). Further, mice deficient in IL-22 appear to be protected from diet-induced obesity (76). In diet-induced obese (DIO) mice, we observed a decrease in the circulating levels of IL-22. Given its proinflammatory activity, reduced plasma levels of IL-22 in the DIO mice may represent a compensatory response to obesity and its associated insulin resistance.

As a proteinase inhibitor, TIMP-1 regulates the activity of matrix metalloproteinases, playing an important role in extracellular matrix and tissue remodeling (77). In humans, the mRNA expression and circulating levels of TIMP-1 are elevated in obesity (29, 42, 51, 53). In mice fed an HFD, increasing the plasma concentrations of TIMP-1 by recombinant protein administration increases the size of adipocytes (54). A sustained short-term overexpression of TIMP-1 in mice via adenoviral vector also has been shown to reduce blood vessel density in the white adipose tissue (72). However, in loss-of-function mouse models, contrasting results were reported for TIMP-1. Depending on the genetic background and sex, HFD-fed mice with TIMP-1 deletion are either obese or lean (28, 46). In our study, we observed an increase in the circulating levels of TIMP-1 in mice fed an HFD relative to the control LFD group, consistent with the human studies (29, 42, 51, 53).

sRAGE is thought to serve as a soluble receptor decoy for advanced glycation end products, thereby reducing proinflammatory responses (10, 67). Consistent with this notion, human plasma sRAGE levels are inversely correlated with obesity and metabolic syndrome (36, 55, 56). Interestingly, in morbidly obese subjects, bariatric surgery increases the circulating levels of sRAGE (12). Our study shows that serum sRAGE levels are decreased in mice fed an HFD compared with control group fed an LFD. Thus, decreased plasma levels of sRAGE in obese humans and DIO mice may be associated with a proinflammatory state.

Haptoglobin is an acute phase protein whose expression is highly induced by inflammatory stimuli such as IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α (65). While liver has the highest expression level of haptoglobin, other tissues such as white and brown fat and lung also express haptoglobin. One of the main functions of haptoglobin is to scavenge hemoglobin resulting from hemolysis or normal red blood cell turnover (65). In humans, serum haptoglobin levels are positively correlated with body mass index (BMI) and fat mass (20). Mice with a targeted deletion of the haptoglobin gene have improved glucose homeostasis, attenuated diet-induced fatty liver, and adipocyte hypertrophy (27, 47). These studies suggest that haptoglobin is a negative regulator of energy metabolism. In contrast to obese humans, HFD-fed obese mice have decreased circulating levels of haptoglobin compared with control mice fed an LFD. Since a high-fat diet was given for a period of 12 wk, reduced haptoglobin levels in HFD-fed mice may be a compensatory response to diet-induced obesity and its associated low-grade inflammation and insulin resistance.

In humans, the expression of chemokine CCL20 (also known as MIP-3α) in adipose tissue is positively correlated with BMI and is expressed at higher levels in visceral compared with subcutaneous fat depots (25). Plasma levels of another related chemokine, CCL4 (also known as MIP-1β), are also positively correlated with waist circumferences (59). However, the function of these chemokines in the context of obesity has not been established. In our study, both CCL20 and CCL4 serum levels are decreased in the HFD-fed mice relative to LFD-fed control group. Although it is not known whether circulating levels of CXCL1 are altered in human obesity, overexpressing CXCL1 in the skeletal muscle of transgenic mice enhances muscle fat oxidation and ameliorates diet-induced obesity (62). In DIO mice, serum levels of CXCL1 were found to be increased relative to control mice fed an LFD, the significance of which remains to be determined.

In summary, we provide evidence that circulating levels of a large number of cytokines are dynamically regulated in response to short- and long-term changes in whole body metabolism. Changes in serum cytokine levels often do not parallel changes in mRNA expression in multiple tissues. We show that two of these cytokines, reciprocally regulated by fasting and refeeding, may have a central role in modulating food intake. This study provides the foundation and framework to systematically examine the metabolic and nonimmune function of cytokines using gain- and loss-of-function approaches.

GRANTS

P. S. Petersen was supported by a Carlsberg Foundation travel grant. M. S. Byerly was supported by a T32 training grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Grant DK-007751. X. Lei was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association (POST17070119). G. W. Wong was supported by NIDDK Grant DK-084171. The serum cytokine profiling was performed at the Integrated Physiology Core of the Diabetes Research and Training Center at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, funded by NIDDK Grant P60DK-079637.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: P.S.P., M.M.S., M.S.B., and G.W.W. conception and design of research; P.S.P., X.L., M.M.S., S.R., M.S.B., A.W., and S.W. performed experiments; P.S.P., X.L., M.M.S., S.R., M.S.B., and G.W.W. analyzed data; P.S.P., X.L., M.M.S., S.R., M.S.B., and G.W.W. interpreted results of experiments; P.S.P. and X.L. prepared figures; P.S.P., M.S.B., and G.W.W. drafted manuscript; X.L., M.M.S., M.S.B., and A.W. edited and revised manuscript; S.R. and S.W. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Susan Aja for her help with the indirect calorimetry study and Patrick McCulloh for help with the food intake study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akira S, Hirano T, Taga T, Kishimoto T. Biology of multifunctional cytokines: IL-6 and related molecules (IL-1 and TNF). FASEB J 4: 2860–2867, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson P. Post-transcriptional control of cytokine production. Nat Immunol 9: 353–359, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asirvatham AJ, Magner WJ, Tomasi TB. miRNA regulation of cytokine genes. Cytokine 45: 58–69, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banks WA, Kastin AJ, Broadwell RD. Passage of cytokines across the blood-brain barrier. Neuroimmunomodulation 2: 241–248, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banks WA, Kastin AJ, Huang W, Jaspan JB, Maness LM. Leptin enters the brain by a saturable system independent of insulin. Peptides 17: 305–311, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banks WA, Kastin AJ, Jaspan JB. Regional variation in transport of pancreatic polypeptide across the blood-brain barrier of mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 51: 139–147, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banks WA, Kastin AJ, Maness LM, Huang W, Jaspan JB. Permeability of the blood-brain barrier to amylin. Life Sci 57: 1993–2001, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banks WA, Niehoff ML, Martin D, Farrell CL. Leptin transport across the blood-brain barrier of the Koletsky rat is not mediated by a product of the leptin receptor gene. Brain Res 950: 130–136, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banks WA, Ortiz L, Plotkin SR, Kastin AJ. Human interleukin (IL) 1 alpha, murine IL-1 alpha and murine IL-1 beta are transported from blood to brain in the mouse by a shared saturable mechanism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 259: 988–996, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basta G. Receptor for advanced glycation endproducts and atherosclerosis: From basic mechanisms to clinical implications. Atherosclerosis 196: 9–21, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baura GD, Foster DM, Porte D, Jr, Kahn SE, Bergman RN, Cobelli C, Schwartz MW. Saturable transport of insulin from plasma into the central nervous system of dogs in vivo. A mechanism for regulated insulin delivery to the brain. J Clin Invest 92: 1824–1830, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brix JM, Hollerl F, Kopp HP, Schernthaner GH, Schernthaner G. The soluble form of the receptor of advanced glycation endproducts increases after bariatric surgery in morbid obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 36: 1412–1417, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buchanan JB, Johnson RW. Regulation of food intake by inflammatory cytokines in the brain. Neuroendocrinology 86: 183–190, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byerly MS, Al Salayta M, Swanson RD, Kwon K, Peterson JM, Wei Z, Aja S, Moran TH, Blackshaw S, Wong GW. Estrogen-related receptor beta deletion modulates whole-body energy balance via estrogen-related receptor gamma and attenuates neuropeptide Y gene expression. Eur J Neurosci 37: 1033–1047, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byerly MS, Petersen PS, Ramamurthy S, Seldin MM, Lei X, Provost E, Wei Z, Ronnett GV, Wong GW. C1q/TNF-related protein 4 (CTRP4) is a unique secreted protein with two tandem C1q domains that functions in the hypothalamus to modulate food intake and body weight. J Biol Chem 289: 4055–4069, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Byerly MS, Swanson R, Wei Z, Seldin MM, McCulloh PS, Wong GW. A central role for C1q/TNF-related protein 13 (CTRP13) in modulating food intake and body weight. PLoS One 8: e62862 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Byerly MS, Swanson RD, Semsarzadeh NN, McCulloh PS, Kwon K, Aja S, Moran TH, Wong GW, Blackshaw S. Identification of hypothalamic neuron-derived neurotrophic factor as a novel factor modulating appetite. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 304: R1085–R1095, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carballo E, Lai WS, Blackshear PJ. Evidence that tristetraprolin is a physiological regulator of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor messenger RNA deadenylation and stability. Blood 95: 1891–1899, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chandra RK. 1990 McCollum Award Lecture Nutrition and immunity: lessons from the past and new insights into the future. Am J Clin Nutr 53: 1087–1101, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiellini C, Santini F, Marsili A, Berti P, Bertacca A, Pelosini C, Scartabelli G, Pardini E, Lopez-Soriano J, Centoni R, Ciccarone AM, Benzi L, Vitti P, Del Prato S, Pinchera A, Maffei M. Serum haptoglobin: a novel marker of adiposity in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89: 2678–2683, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Claycombe K, King LE, Fraker PJ. A role for leptin in sustaining lymphopoiesis and myelopoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 2017–2021, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dalmas E, Venteclef N, Caer C, Poitou C, Cremer I, Aron-Winewsky J, Lacroix-Desmazes S, Bayry J, Kaveri SV, Clement K, Andre S, Guerre-Millo M. T-cell-derived IL-22 amplifies IL-1β-driven inflammation in human adipose tissue: relevance to obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 63: 1966–1977, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Jager W, te Velthuis H, Prakken BJ, Kuis W, Rijkers GT. Simultaneous detection of 15 human cytokines in a single sample of stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 10: 133–139, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dinarello CA. Historical insights into cytokines. Eur J Immunol 37 Suppl 1: S34–S45, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duffaut C, Zakaroff-Girard A, Bourlier V, Decaunes P, Maumus M, Chiotasso P, Sengenes C, Lafontan M, Galitzky J, Bouloumie A. Interplay between human adipocytes and T lymphocytes in obesity: CCL20 as an adipochemokine and T lymphocytes as lipogenic modulators. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 29: 1608–1614, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fantino M, Wieteska L. Evidence for a direct central anorectic effect of tumor-necrosis-factor-alpha in the rat. Physiol Behav 53: 477–483, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gamucci O, Lisi S, Scabia G, Marchi M, Piaggi P, Duranti E, Virdis A, Pinchera A, Santini F, Maffei M. Haptoglobin deficiency determines changes in adipocyte size and adipogenesis. Adipocyte 1: 142–183, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerin I, Louis GW, Zhang X, Prestwich TC, Kumar TR, Myers MG, Jr, Macdougald OA, Nothnick WB. Hyperphagia and obesity in female mice lacking tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1. Endocrinology 150: 1697–1704, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glowinska-Olszewska B, Urban M. Elevated matrix metalloproteinase 9 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 in obese children and adolescents. Metabolism 56: 799–805, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grill HJ, Kaplan JM. The neuroanatomical axis for control of energy balance. Front Neuroendocrinol 23: 2–40, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grill HJ, Schwartz MW, Kaplan JM, Foxhall JS, Breininger J, Baskin DG. Evidence that the caudal brainstem is a target for the inhibitory effect of leptin on food intake. Endocrinology 143: 239–246, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanisch UK. Microglia as a source and target of cytokines. Glia 40: 140–155, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hansen MK, Taishi P, Chen Z, Krueger JM. Cafeteria feeding induces interleukin-1β mRNA expression in rat liver and brain. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 274: R1734–R1739, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayes MR, Leichner TM, Zhao S, Lee GS, Chowansky A, Zimmer D, De Jonghe BC, Kanoski SE, Grill HJ, Bence KK. Intracellular signals mediating the food intake-suppressive effects of hindbrain glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor activation. Cell Metab 13: 320–330, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayes MR, Skibicka KP, Leichner TM, Guarnieri DJ, DiLeone RJ, Bence KK, Grill HJ. Endogenous leptin signaling in the caudal nucleus tractus solitarius and area postrema is required for energy balance regulation. Cell Metab 11: 77–83, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He CT, Lee CH, Hsieh CH, Hsiao FC, Kuo P, Chu NF, Hung YJ. Soluble form of receptor for advanced glycation end products is associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome in adolescents. Int J Endocrinol 2014: 657607, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hellerstein MK, Meydani SN, Meydani M, Wu K, Dinarello CA. Interleukin-1-induced anorexia in the rat. Influence of prostaglandins. J Clin Invest 84: 228–235, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 444: 860–867, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karlsson EA, Beck MA. The burden of obesity on infectious disease. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 235: 1412–1424, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karlsson EA, Sheridan PA, Beck MA. Diet-induced obesity impairs the T cell memory response to influenza virus infection. J Immunol 184: 3127–3133, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kent S, Bluthe RM, Dantzer R, Hardwick AJ, Kelley KW, Rothwell NJ, Vannice JL. Different receptor mechanisms mediate the pyrogenic and behavioral effects of interleukin 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 9117–9120, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kralisch S, Bluher M, Tonjes A, Lossner U, Paschke R, Stumvoll M, Fasshauer M. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 predicts adiposity in humans. Eur J Endocrinol 156: 257–261, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuperman EF, Showalter JW, Lehman EB, Leib AE, Kraschnewski JL. The impact of obesity on sepsis mortality: a retrospective review. BMC Infect Dis 13: 377, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Langlet F, Levin BE, Luquet S, Mazzone M, Messina A, Dunn-Meynell AA, Balland E, Lacombe A, Mazur D, Carmeliet P, Bouret SG, Prevot V, Dehouck B. Tanycytic VEGF-A boosts blood-hypothalamus barrier plasticity and access of metabolic signals to the arcuate nucleus in response to fasting. Cell Metab 17: 607–617, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lautenbach A, Wrann CD, Jacobs R, Muller G, Brabant G, Nave H. Altered phenotype of NK cells from obese rats can be normalized by transfer into lean animals. Obesity (Silver Spring) 17: 1848–1855, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lijnen HR, Demeulemeester D, Van Hoef B, Collen D, Maquoi E. Deficiency of tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) impairs nutritionally induced obesity in mice. Thromb Haemost 89: 249–255, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lisi S, Gamucci O, Vottari T, Scabia G, Funicello M, Marchi M, Galli G, Arisi I, Brandi R, D'Onofrio M, Pinchera A, Santini F, Maffei M. Obesity-associated hepatosteatosis and impairment of glucose homeostasis are attenuated by haptoglobin deficiency. Diabetes 60: 2496–2505, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lord GM, Matarese G, Howard JK, Baker RJ, Bloom SR, Lechler RI. Leptin modulates the T-cell immune response and reverses starvation-induced immunosuppression. Nature 394: 897–901, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luheshi GN, Gardner JD, Rushforth DA, Loudon AS, Rothwell NJ. Leptin actions on food intake and body temperature are mediated by IL-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 7047–7052, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luna-Moreno D, Aguilar-Roblero R, Diaz-Munoz M. Restricted feeding entrains rhythms of inflammation-related factors without promoting an acute-phase response. Chronobiol Int 26: 1409–1429, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maquoi E, Munaut C, Colige A, Collen D, Lijnen HR. Modulation of adipose tissue expression of murine matrix metalloproteinases and their tissue inhibitors with obesity. Diabetes 51: 1093–1101, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marcos A, Nova E, Montero A. Changes in the immune system are conditioned by nutrition. Eur J Clin Nutr 57 Suppl 1: S66–S69, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maury E, Ehala-Aleksejev K, Guiot Y, Detry R, Vandenhooft A, Brichard SM. Adipokines oversecreted by omental adipose tissue in human obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E656–E665, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meissburger B, Stachorski L, Roder E, Rudofsky G, Wolfrum C. Tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP1) controls adipogenesis in obesity in mice and in humans. Diabetologia 54: 1468–1479, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Momma H, Niu K, Kobayashi Y, Huang C, Chujo M, Otomo A, Tadaura H, Miyata T, Nagatomi R. Higher serum soluble receptor for advanced glycation end product levels and lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome among Japanese adult men: a cross-sectional study. Diabetol Metab Syndr 6: 33, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Momma H, Niu K, Kobayashi Y, Huang C, Chujo M, Otomo A, Tadaura H, Miyata T, Nagatomi R. Lower serum endogenous secretory receptor for advanced glycation end product level as a risk factor of metabolic syndrome among Japanese adult men: a 2-year longitudinal study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99: 587–593, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nieman DC, Henson DA, Nehlsen-Cannarella SL, Ekkens M, Utter AC, Butterworth DE, Fagoaga OR. Influence of obesity on immune function. J Am Diet Assoc 99: 294–299, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.O'Rourke RW, Kay T, Scholz MH, Diggs B, Jobe BA, Lewinsohn DM, Bakke AC. Alterations in T-cell subset frequency in peripheral blood in obesity. Obes Surg 15: 1463–1468, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ognjanovic S, Jacobs DR, Steinberger J, Moran A, Sinaiko AR. Relation of chemokines to BMI and insulin resistance at ages 18–21. Int J Obes (Lond) 37: 420–423, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Olson JK, Miller SD. Microglia initiate central nervous system innate and adaptive immune responses through multiple TLRs. J Immunol 173: 3916–3924, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Passini MA, Wolfe JH. Widespread gene delivery and structure-specific patterns of expression in the brain after intraventricular injections of neonatal mice with an adeno-associated virus vector. J Virol 75: 12382–12392, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pedersen L, Olsen CH, Pedersen BK, Hojman P. Muscle-derived expression of the chemokine CXCL1 attenuates diet-induced obesity and improves fatty acid oxidation in the muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 302: E831–E840, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peruzzo B, Pastor FE, Blazquez JL, Schobitz K, Pelaez B, Amat P, Rodriguez EM. A second look at the barriers of the medial basal hypothalamus. Exp Brain Res 132: 10–26, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peterson JM, Wei Z, Seldin MM, Byerly MS, Aja S, Wong GW. CTRP9 transgenic mice are protected from diet-induced obesity and metabolic dysfunction. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 305: R522–R533, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Quaye IK. Haptoglobin, inflammation and disease. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 102: 735–742, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reed JA, Clegg DJ, Smith KB, Tolod-Richer EG, Matter EK, Picard LS, Seeley RJ. GM-CSF action in the CNS decreases food intake and body weight. J Clin Invest 115: 3035–3044, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Santilli F, Vazzana N, Bucciarelli LG, Davi G. Soluble forms of RAGE in human diseases: clinical and therapeutical implications. Curr Med Chem 16: 940–952, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat Protoc 3: 1101–1108, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schneider A, Kruger C, Steigleder T, Weber D, Pitzer C, Laage R, Aronowski J, Maurer MH, Gassler N, Mier W, Hasselblatt M, Kollmar R, Schwab S, Sommer C, Bach A, Kuhn HG, Schabitz WR. The hematopoietic factor G-CSF is a neuronal ligand that counteracts programmed cell death and drives neurogenesis. J Clin Invest 115: 2083–2098, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schobitz B, Pezeshki G, Pohl T, Hemmann U, Heinrich PC, Holsboer F, Reul JM. Soluble interleukin-6 (IL-6) receptor augments central effects of IL-6 in vivo. FASEB J 9: 659–664, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schwartz MW, Woods SC, Porte D, Jr, Seeley RJ, Baskin DG. Central nervous system control of food intake. Nature 404: 661–671, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Scroyen I, Jacobs F, Cosemans L, De Geest B, Lijnen HR. Blood vessel density in de novo formed adipose tissue is decreased upon overexpression of TIMP-1. Obesity (Silver Spring) 18: 638–640, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Seldin MM, Peterson JM, Byerly MS, Wei Z, Wong GW. Myonectin (CTRP15), a novel myokine that links skeletal muscle to systemic lipid homeostasis. J Biol Chem 287: 11968–11980, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Smith AG, Sheridan PA, Tseng RJ, Sheridan JF, Beck MA. Selective impairment in dendritic cell function and altered antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in diet-induced obese mice infected with influenza virus. Immunology 126: 268–279, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Smith JA, Das A, Ray SK, Banik NL. Role of pro-inflammatory cytokines released from microglia in neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Res Bull 87: 10–20, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Upadhyay V, Poroyko V, Kim TJ, Devkota S, Fu S, Liu D, Tumanov AV, Koroleva EP, Deng L, Nagler C, Chang EB, Tang H, Fu YX. Lymphotoxin regulates commensal responses to enable diet-induced obesity. Nat Immunol 13: 947–953, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Visse R, Nagase H. Matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases: structure, function, and biochemistry. Circ Res 92: 827–839, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vozarova B, Weyer C, Hanson K, Tataranni PA, Bogardus C, Pratley RE. Circulating interleukin-6 in relation to adiposity, insulin action, and insulin secretion. Obes Res 9: 414–417, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wei Z, Seldin MM, Natarajan N, Djemal DC, Peterson JM, Wong GW. C1q/tumor necrosis factor-related protein 11 (CTRP11), a novel adipose stroma-derived regulator of adipogenesis. J Biol Chem 288: 10214–10229, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW., Jr. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest 112: 1796–1808, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D, Chou CJ, Sole J, Nichols A, Ross JS, Tartaglia LA, Chen H. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 112: 1821–1830, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yang H, Youm YH, Vandanmagsar B, Rood J, Kumar KG, Butler AA, Dixit VD. Obesity accelerates thymic aging. Blood 114: 3803–3812, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yang ZJ, Blaha V, Meguid MM, Laviano A, Oler A, Zadak Z. Interleukin-1α injection into ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus of normal rats depresses food intake and increases release of dopamine and serotonin. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 62: 61–65, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhao LR, Navalitloha Y, Singhal S, Mehta J, Piao CS, Guo WP, Kessler JA, Groothuis DR. Hematopoietic growth factors pass through the blood-brain barrier in intact rats. Exp Neurol 204: 569–573, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhao R, Tang D, Yi S, Li W, Wu C, Lu Y, Hou X, Song J, Lin P, Chen L, Sun L. Elevated peripheral frequencies of Th22 cells: a novel potent participant in obesity and type 2 diabetes. PLoS One 9: e85770, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zorrilla EP, Sanchez-Alavez M, Sugama S, Brennan M, Fernandez R, Bartfai T, Conti B. Interleukin-18 controls energy homeostasis by suppressing appetite and feed efficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 11097–11102, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]