Abstract

Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is associated with mutations in sarcomeric proteins, including the myosin regulatory light chain (RLC). Here we studied the impact of three HCM mutations located in the NH2 terminus of the RLC on the molecular mechanism of β-myosin heavy chain (MHC) cross-bridge mechanics using the in vitro motility assay. To generate mutant β-myosin, native RLC was depleted from porcine cardiac MHC and reconstituted with mutant (A13T, F18L, and E22K) or wild-type (WT) human cardiac RLC. We characterized the mutant myosin force and motion generation capability in the presence of a frictional load. Compared with WT, all three mutants exhibited reductions in maximal actin filament velocity when tested under low or no frictional load. The actin-activated ATPase showed no significant difference between WT and HCM-mutant-reconstituted myosins. The decrease in velocity has been attributed to a significantly increased duty cycle, as was measured by the dependence of actin sliding velocity on myosin surface density, for all three mutant myosins. These results demonstrate a mutation-induced alteration in acto-myosin interactions that may contribute to the pathogenesis of HCM.

Keywords: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, myosin regulatory light chain, cardiac ventricular myosin, in vitro motility

the interaction of actin and myosin II in striated muscle is a tightly controlled and regulated system involving many proteins on the thick and thin filaments. Mutations in any of these proteins can greatly impact acto-myosin interactions and cardiac muscle function. The most common and hence most researched group of mutations is the hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)-associated mutations. These mutations are found in the myofilament proteins and result in enlargement (hypertrophy) of the heart, most commonly the left ventricular wall, interventricular septum, and in some cases the papillary muscles (22, 23).

Myosin, the molecular motor that powers muscle contraction, is a hexameric protein consisting of two heavy chains (∼200 kDa each) that self-associate via an alpha-helical coiled-coil domain. Two light chains, one essential light chain (ELC) and one regulatory light chain (RLC), are associated with each heavy chain. The entire myosin molecule can be broadly divided into two domains: the rod domain, which functions in filament formation, and the head domain, which has been shown to be sufficient for motion and force generation (16, 46). The myosin head domain is asymmetric with a globular portion, which contains the actin binding site and ATP hydrolytic activities (the motor domain), and an elongated alpha-helical MHC-neck domain that is supported by the binding of the two light chains (the neck domain).

The neck domain of the myosin head functions to amplify conformational changes originating in the globular motor domain via a lever-like action (2, 25, 34, 38, 51). Given its role in supporting the elongated neck region of the myosin head, it is not surprising that mutations in the regulatory light chain (RLC) were found to cause HCM. To date, several RLC mutations (see Fig. 1) have been linked to HCM (3, 27, 41), with five found near the COOH-terminal end (P95A, K104E, E134A, G162R, and D166V) (3, 27, 41), two located near the cation-binding domain (N47K and R58Q) (27, 41), and four that are located at the NH2-terminal end of the protein (A13T, F18L, M20L, and E22K) (3, 27, 41). The RLC is important due to its position on the myosin molecule (4) and its suspected role in imparting stiffness to the neck region of the myosin head (32). Consistent with this idea, a single amino acid mutation in skeletal muscle RLC, F102L, resulted in a decreased actin filament velocity in the in vitro motility assays (39). The importance of the RLC was also noted in experiments involving β-myosin containing the N47K and R58Q RLC HCM mutations that demonstrated alterations in the ability to propel actin under load (10). A decrease in force was also observed in transgenic mice containing the COOH-terminal RLC mutant (D166V) (18, 28). On the other hand, myocardium from transgenic mice expressing 10% A13T mutant RLC displayed elevated contractile force (17). These observations strongly support the notion that the RLC acts either alone or in concert with the ELC to add stiffness to the lever arm region of the myosin II molecule.

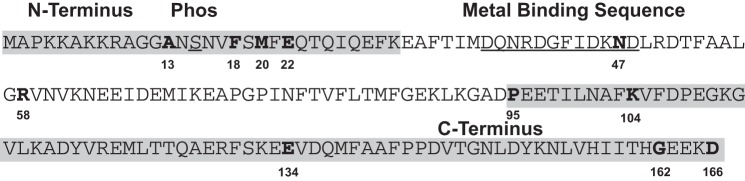

Fig. 1.

The linear amino acid sequence of human cardiac ventricular regulatory light chain. In this figure the NH2 and COOH termini of the molecule are shaded in gray, with the metal binding domain and the phosphorylatable serine underlined. The 11 known hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) mutations are indicated in bold and numbered. Note that 9 of the mutations reside in the gray-shaded areas with the other 2 mutations, N47K and R58Q, residing either in or near the metal binding domain. In this study we determined the mechanochemical effects of the A13T, F18L, and E22K mutant myosins, which are located near the NH2 terminus of the molecule.

In addition to its role in stabilizing the neck region of myosin, the NH2-terminal region and phosphorylation sites of the RLC have also been shown to be critical for the interaction of the myosin head with actin as well as impact the orientation of the myosin head in Drosophila (9). Furthermore, the phosphorylation state of the NH2-terminal serine has been implicated in contractile function, including enhanced stretch activation response in myocardium (5, 40), increased calcium sensitivity of striated muscle contraction (31, 43), and structurally controlling myosin head orientation (8, 9). Therefore, the RLC molecule, in particular the NH2-terminal region, may also play a role in the acto-myosin interactions.

To test the effects of the RLC-HCM mutations on the acto-myosin contractile activity, we produced myosin molecules containing the mutant light chains by exchanging bacterially expressed human cardiac RLCs onto purified porcine cardiac myosin. We used the in vitro motility assay to assess the effects of these NH2-terminal RLC mutations on myosin motion generation. We found that the principal defect for the NH2-terminal HCM mutant myosins is a loss in actin sliding velocity under low load. Measurements of solution ATPase activity and the dependence of actin filament velocity on myosin function indicated that the loss of velocity cannot be attributed to a decrease in the mutant myosin enzymatic activity but instead are a result of an increased duty cycle. These data demonstrate HCM mutation-induced changes in actomyosin interactions that could directly contribute to the disease phenotype.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Solutions.

All solutions used for in vitro motility assays were made as described previously (10, 11) with some modifications. As shown in Table 1, N,N-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid (BES) replaced imidazole.

Table 1.

Composition of the buffers used in these experiments

| Compound | Myosin Buffer | Actin Buffer | Actin + ATP | Motility Buffer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KCl | 300 mM | 55 mM | 55 mM | 55 mM |

| BES | 25 mM | 25 mM | 25 mM | 25 mM |

| MgCl2 | 4 mM | 4 mM | 4 mM | 4 mM |

| EGTA | 5 mM | 5 mM | 5 mM | 5 mM |

| Glucose | 0 mM | 0 mM | 0 mM | 2 mM |

| ATP | 0 mM | 0 mM | 1 mM | 1 mM |

| Glucose oxidase | N/A | N/A | N/A | 160 units |

| Catalase | 0 mM | 0 mM | 0 mM | 2 mM |

Note that the buffer BES was used instead of imidazole due to its better buffering capacity.

Depletion of native porcine RLC and reconstitution with human ventricular WT/HCM RLC.

Endogenous porcine cardiac RLC was depleted from the myosin heavy chain using the protocol described previously (32) with modifications. Briefly, native porcine cardiac myosin was precipitated in 4°C water with 10 mM DTT for 1 h, and then centrifuged at 8,800 g for 30 min. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 500 mM KCl and 50 mM KH2PO4, pH 8.5, to a final concentration of 1.5–2.0 mg/ml. Triton X-100 and CDTA were added to this solution to a final concentration 1% and 5 mM, respectively. After a 15-min incubation at room temperature the reaction was terminated by diluting 10-fold in ice-cold water with 10 mM DTT followed by a 1-h incubation. The myosin was pelleted once again at 8,800 g for 30 min and the pellet resuspended in minimal reconstitution buffer (400 mM KCl, 50 mM BES, 2 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM DTT). Myosin concentration was determined by a Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Labs, Hercules, CA). Depleted myosin was then reconstituted with bacterially expressed RLC (42) by incubation for 2 h at 4°C at a 3:1 RLC to myosin molar ratio. Reconstitution was terminated by precipitating the myosin in ice-cold 10 mM DTT. The reconstituted myosin was resuspended in minimal high-salt buffer (600 mM KCl, 50 mM BES, and 20 mM DTT) and mixed 1:1 with glycerol and stored at −20°C for up to 3 wk. The amount of exchanged RLC for each variant was determined using the ratio of RLC to ELC (in native, depleted, and reconstituted) as determined by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie stain. As shown in Fig. 2 the average amount of exchange for all four RLCs was 85.4 ± 4.2%, 81.3 ± 0.5%, 85.7 ± 5.5%, and 81.0 ± 1.9% for WT, A13T, F18L, and E22K respectively.

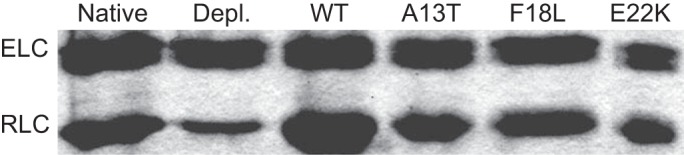

Fig. 2.

SDS-PAGE of native (lane 1), depleted (lane 2), and exchanged regulatory light chain (RLC) onto porcine cardiac beta myosin. As indicated by the gel the depletion reaction is able to remove ∼80–85% of the native RLC as indicated by densitometry traces, with the subsequent exchanges of WT, A13T, F18L, or E22K (lanes 3–6, respectively) yielding an average exchange of 85.4% ± 4.2%, 81.3% ± 0.5%, 85.7% ± 5.5%, and 81.0% ± 1.9%, respectively. ELC, essential light chain.

In vitro motility assay.

Experiments were performed as described previously (32) with some modifications. BSA concentration was increased from 0.5 to 1 mg/ml. Briefly, ∼20 μl flow cells were constructed by attaching nitrocellulose-coated coverslips and a standard glass slide with 100-μm-thick 3M double stick tape. Myosin and α-actinin (50 μg/ml) were mixed in myosin buffer (Table 1) and incubated in the flow cell for 1 min. This was followed by 25 μl of 1 mg/ml BSA, for 1 min, in myosin buffer to remove any unbound myosin and block the remaining surface sites to avoid nonspecific attachment of actin filaments. After blocking, 50 μl of actin buffer was flowed through the chamber, followed by the addition of unlabeled actin. This actin was allowed to incubate for 2 min before being washed out with 50 μl of actin + ATP buffer and then 100 μl of actin buffer to remove the ATP. TRITC labeled actin filaments in low-salt buffer was then added to the flow cell and allowed to incubate for 30 seconds. Unbound actin was washed out and motility initiated by the addition of low-salt buffer with 1 mM ATP and oxygen scavengers.

Myosin duty cycle.

To examine if the HCM mutants caused changes in myosin duty ratio, we measured the actin sliding velocity as a function of increasing myosin concentrations. In this assay, actin filaments are translocated at maximum velocity (Vmax) if at least one head is interacting with the actin filament at all times. The probability of this occurring is related to the number of heads available to interact with actin (loading concentration, ρ) and the fraction of ATPase cycle time that myosin molecule remains bound, r (i.e., duty cycle). Assuming that the motors act asynchronously, the probability that at least one head is interacting with actin at all times is given by 1 − (1 − r)ρ. Accordingly, at low motor surface densities, velocity will decrease as a function of r and ρ, according to the equation:

| (1) |

where Vobs is the observed velocity of the actin filament, and Vmax is the maximal sliding velocity at saturating myosin concentrations (26, 48). Therefore, a myosin with a higher duty cycle will be able to move an actin filament at maximal velocity at a lower concentration, whereas a myosin with a lower duty cycle will require a greater concentration on the motility assay surface in order to ensure that at least one myosin head is attached to actin at any given time.

Data acquisition and analysis.

Movies of actin filament motion on the cover glass surface were captured at three frames per second on an intensified charge-coupled device (ICCD) camera (IC300; PTI, Birmingham, NJ) using software (XCAP) and PCIe card (PIXCI SV7) purchased from EPIX (Buffalo Grove, IL). All movies were analyzed using an ImageJ plug-in, wrMTRCK [written by J. S. Pedersen (jsp@phage.dk)]. This program is a centroid-tracking program that automatically locates and tracks objects within a movie and reports the velocity of the object. All filaments from a single movie that have been determined to be moving are then averaged to give a single value for that movie. The average velocity for each movie is considered an N of 1 for each movie collected. For both the myosin dose response, and α-actinin curves 10 movies were collected for each data point for each exchanged myosin with 4–5 exchanges run for all RLC variants tested here.

Actin-activated ATPase assays.

WT-RLC and the three HCM mutants were diluted 1:10 in 4°C water, 10 mM DTT for 1 h. Precipitated (filamentous) myosin was centrifuged for 30 min at 8,800 g. The resulting pellet was resuspended in a minimal amount of 10X salt buffer (800 mM KCl, 50 mM BES, and 10 mM DTT) and the protein concentration was determined using a Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Labs). Actin-activated ATPase activity was measured using the ATPase Kinetic ELIPA Assay Kit (Cytoskeleton, Denver, CO) that is based on an absorbance shift from 330 to 360 nm when 2-amino-6-mercapto-7-methylpurine ribonucleoside (MESG) is converted to 2-amino-6-mercapto-7-methyl purine in the presence of inorganic phosphate. The reaction was run according to the manufacturer's instructions with a slight modification: the reaction volume was doubled from 300 to 600 μl to accommodate the 1-ml cuvettes used to measure the absorbance at 360 nm. Prior to measuring the ATPase activity of the exchanged myosins, the three components of the reaction were mixed in the amounts recommended by the manufacturer and allowed to mix briefly for 5 min before pipetting 540 μl of the reaction volume into 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes. G-actin was added to the reaction tubes to a final concentration of 1.9 μM along with 55 μl of myosin with one of four RLC exchanged myosins (wild-type, A13T, F18L, or E22K) and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. For myosin-free controls 55 μl of high-salt buffer was added thereby mimicking the condition for myosin-containing samples. The ATPase reaction was initiated by the addition of ATP (final concentration 10 mM). MESG, and thus phosphate production, was monitored by absorbance at 360 nm at room temperature. Measurements were made every 20 s for 20 min and the resulting measurements, two or three runs for each mutant myosin, were pooled to obtain the average ATPase for each myosin.

Statistics.

Statistical analysis referred to in this paper was performed using Prism 6 (GraphPad 7825, La Jolla, CA). One-way ANOVA was used to compare the actin sliding velocities between WT and HCM mutants at all amounts of applied α-actinin. Significance between the curves was determined using the compare function within the analyze window using the extra sum-of squares F-test. Significance was determined if the returned P value was <0.05.

RESULTS

Impact of RLC HCM mutations on sliding velocity.

To examine the direct impact of the NH2-terminal HCM mutations on the motility and kinetics of β-myosin, we performed experiments on isolated porcine β-myosin, which is 97% identical to human β-myosin, in which the native cardiac RLC was exchanged with the recombinant human ventricular WT and mutant RLC. As described previously, we found that RLC depletion and reconstitution had no statistically significant effects on steady-state ATPase activity and restored actin filament velocity to near untreated myosin values (32).

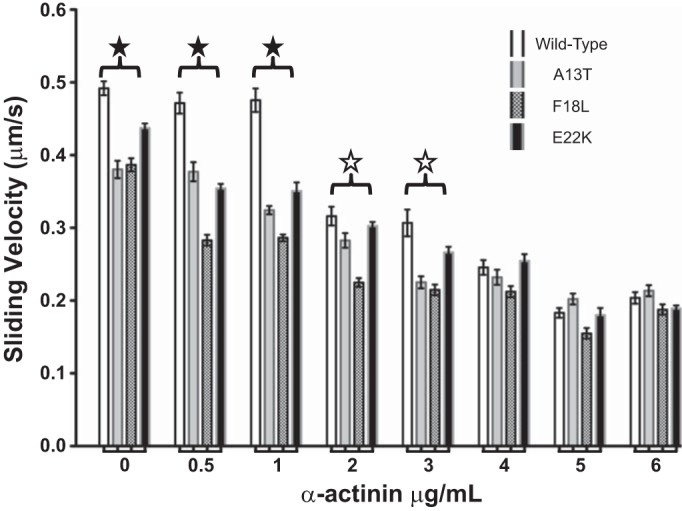

We used the in vitro motility assay to assess the mechanical properties of the myosin mutants used in this study. As shown in Fig. 3, all three NH2-terminal RLC mutations have significantly reduced unloaded actin sliding velocities when compared with WT-exchanged myosin. Porcine RLC is 97% identical to human RLC and control experiments show no significant differences in actin filament velocity between porcine myosin reconstituted with human or porcine RLC (not shown). To further scrutinize the impact of these mutations on actin sliding velocity, we introduced frictional loads with increasing amounts of the actin binding protein α-actinin. Under little to no frictional load (0–1 μg/ml α-actinin), all three mutants had significantly reduced velocities, indicated by the closed star. Increasing the frictional load reduced the velocities of all four strains with significant differences between WT and two of the mutants (A13T and F18L; open star), Table 2 gives the significance values compared with WT for the sliding velocities. At the higher loads (>3 μg/ml α-actinin) the velocities of the different RLC containing myosin constructs converged to a similar value as observed for WT, indicating similar force-generating capability.

Fig. 3.

Impact of NH2-terminal HCM RLC mutations on actin sliding velocity with varying amounts of frictional load. Note that the unloaded actin filament velocities driven by the mutant myosins are reduced compared with WT (P < 0.001). Similarly, actin filament velocities were significantly slower than wild type under low frictional load (up to 2 μg/ml α-actinin; solid stars; open stars indicate significance for A13T and F18L only). Yet, when the frictional load is increased beyond 3 μg/ml the actin sliding velocity for the mutants is not significantly different from the wild-type. Except for F18L at 6 μg/ml α-actinin (N = 9), all points represent the average of more than 25 movies; error bars represent SE.

Table 2.

P values of the frictional loaded assay illustrating the level of significance in the difference in sliding velocities relative to the wild-type sliding velocity

| Strain |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| α-Actinin, mg/ml | A13T | F18L | E22K |

| 0 | *** | *** | *** |

| 0.5 | *** | *** | *** |

| 1 | *** | *** | *** |

| 2 | * | *** | NS |

| 3 | *** | *** | NS |

| 4 | NS | NS | NS |

| 5 | NS | NS | NS |

| 6 | NS | NS | NS |

P < 0.001,

P < 0.05. NS, not significant.

Actin-activated ATPase.

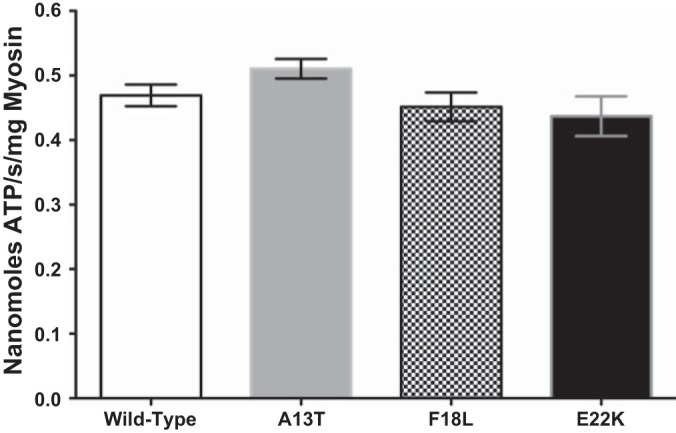

In the in vitro motility assay the actin filament velocity can be affected by changes in ATPase activity and/or duty ratio; therefore we measured these parameters to determine the underlying mechanism for the HCM-mutation-induced changes in velocity (12). To determine if the reduction in unloaded velocity observed with the HCM mutations resulted from a reduced ATPase activity, we examined the actin-activated ATPase activity of all four strains of RLC. As shown in Fig. 4, the ATPase activity of β-myosin containing exogenous human RLC demonstrated no significant difference in ATPase activity between WT and the three RLC mutants.

Fig. 4.

Actin-activated ATPase activity of β-myosin bearing WT and HCM-exchanged RLC. The ATPase activity of all four RLC exchanged β-myosins were not significantly different (average from 3 exchanges); error bars represent SE.

Myosin duty cycle.

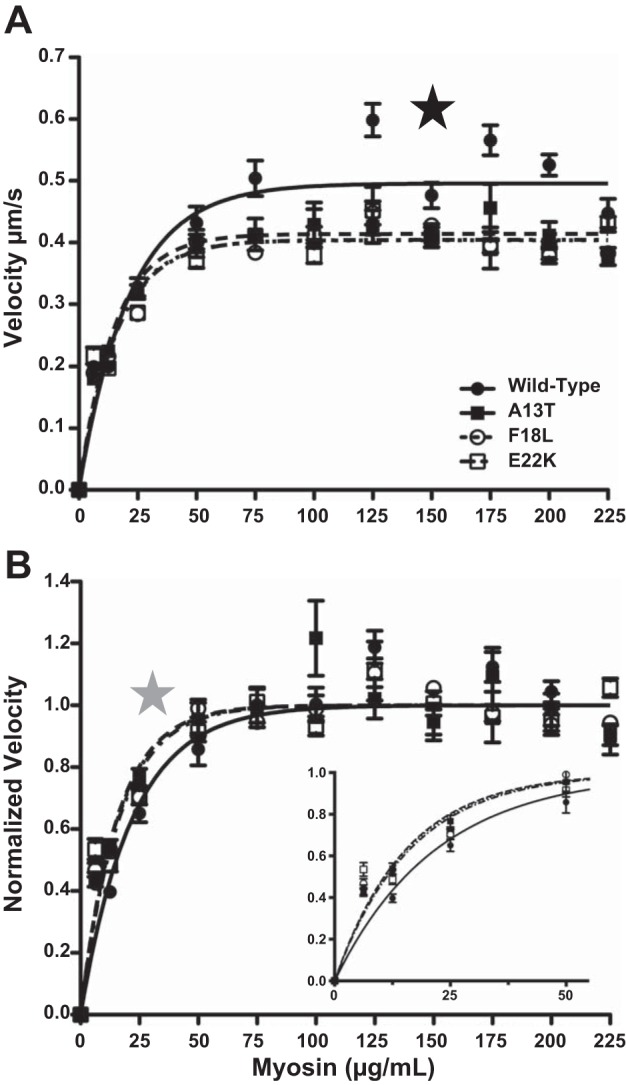

As shown in Fig. 5A, actin filament velocity was independent of myosin concentration over a broad range (50–200 μg/ml) for all of the myosins studied. Consistent with the data presented in Fig. 3, all three mutants (Vmax = 0.414 ± 0.008, 0.404 ± 0.004, and 0.404 ± 0.006 for A13T, F18L, and E22K, respectively) were significantly slower than WT (Vmax = 0.496 ± 0.009). As the concentration of myosin loaded onto the motility surface was lowered below 50 μg/ml, the normalized velocity for all strains decreased but the velocity at low myosin concentrations was higher for the mutants compared with WT (Fig. 5B). The relationship between actin filament velocity and surface density was used to estimate duty cycle, r (Eq. 1). The calculated r values are presented (see Fig. 5 legend). The HCM-RLC mutant myosins showed a significantly higher duty cycle when compared with the wild-type control myosin (Fig. 5B). This result indicates that, consistent with the inverse relationship between duty cycle and velocity (30), the mutation-induced increase in duty cycle contributes to the reduced Vmax.

Fig. 5.

Effect of HCM mutations on the duty cycle of β-myosin. As shown in A, consistent with the results from Fig. 1, the calculated Vmax for the 3 HCM mutants were significantly (P < 0.0001) slower than WT-RLC exchange myosin (0.496 ± 0.009, 0.414 ± 0.008, 0.404 ± 0.004, and 0.404 ± 0.006 mm/s for WT, A13T, F18L, and E22K, respectively), as indicated by the black star. B: normalizing the sliding velocities to the calculated Vmax illustrates that all 3 HCM mutants had a significantly (P < 0.01) larger duty cycle (6.3± 0.6%, 6.2± 0.3%, and 6.0± 0.4% for A13T, F18L and E22K, as shown in inset of B) than the wild-type exchanged myosin (4.4± 0.3%) (as indicated by the gray star). Data from 0-50 μg/l are plotted in the inset of B. For WT, A13T, and E22K there were 15–25 measurements per myosin concentration while for F18L the N was 25–35 movies for each point; error bars represent SE.

DISCUSSION

HCM is a disease of the myocardium manifested by hypertrophy, myofibrillar disarray, and fibrosis and was shown to result from mutations in sarcomeric proteins. In this report, we examined the impact of three of the four known NH2-terminal RLC-HCM mutations on the kinetics and mechanical properties of isolated myosin using the in vitro motility assay. To determine the effect of the mutations on acto-myosin contractile activity, reconstituted myosin preparations with the endogenous regulatory light chain extracted and replaced with bacterially expressed mutant RLCs were generated. The actin filament velocity, actin-activated ATPase, and duty cycle of the mutant myosins were examined to elucidate the mechanical and biochemical properties altered by the mutations. The results provide crucial information about the initial effects of these mutations on acto-myosin interactions, which ultimately may lead to the disease phenotype.

The RLC is found ubiquitously expressed in all muscle myosins and is proposed to play an important role in stiffening of the myosin neck region (lever arm) (19, 20, 47). Since the neck region of the myosin head is thought to undergo large changes in orientation during myosin motion generation (13, 21, 33, 36, 37), we hypothesized that the RLC-HCM mutations may disrupt actin filament velocity by either altering its mechanical properties or its biochemistry.

This present study demonstrates that the A13T and F18L mutations impose dramatic reductions in unloaded shortening velocity at saturating myosin surface densities (Fig. 3). On the other hand, the myosin bearing the E22K mutation was shown to produce a much more subtle effect (Fig. 3), strongly indicating that the amino acids around the phosphorylatable serine, along with the phosphorylatable serine, play an important role in stabilizing the lever arm region of the myosin molecule. No significant differences in myosin ATPase activity were observed between WT and the three RLC mutants (Fig. 4). Interestingly, differences in velocity observed for the NH2-terminal HCM mutants were minimized by the addition of an α-actinin-induced frictional load to the motility assay. These reported results are consistent with those published earlier for transgenic A13T mice (17), but differ when compared with results reported for transgenic E22K mice (7, 45). These differences are likely due to the myosin heavy chain isoform (porcine β vs. mouse α) bearing the mutant RLC. Therefore, in contrast to what has been observed for the more malignant mutations in the RLC, R58Q, (10) and D166V (29), the NH2-terminal RLC-HCM mutations do not appear to disrupt transfer of load to the active site.

There is precedence for mutations in the RLC resulting in a decrease in actin sliding velocity. Respective mutations in Dictyostelium myosin, E12T, and G18K also showed an unloaded contractile defect, evident as a ∼50% reduction in actin filament velocity with no change in ATPase activity (4). Similarly, the Dictyostelium RLC mutant, N94A, exhibited defects in cytokinesis as well as a dramatic reduction in ATPase activity and actin filament velocity. Furthermore, while not an HCM mutation, a single amino acid substitution in skeletal muscle myosin, F102L, resulted in decreased actin filament velocity (39).

Despite reductions in unloaded shortening velocity at saturating myosin surface densities, the RLC-HCM mutations studied here reached maximal sliding velocity at lower myosin concentrations compared with WT-RLC, indicating a higher unloaded duty cycle. This, combined with the fact that no change was seen for the actin-activated ATPase activity for the mutants compared with WT (Fig. 4), indicates that the reduced unloaded velocity observed for myosin containing the RLC-HCM mutations results, at least in part, from an increase in duty cycle. A decreased velocity and an increase in duty cycle are both consistent with a reduction in the acto-myosin detachment rate (14).

Because of the absence of the NH2-terminal region of the RLC from the atomic structure of myosin S1 (35), little is known about the interaction of the NH2-terminal region of the RLC with the rest of the myosin molecule. Mechanically, alterations in the NH2-terminal portion of the RLC in Drosophila indirect flight muscle (IFM), although larger than vertebrate RLC, reduce work and power output in these muscles (6, 15, 24) potentially by altering the proximity of the myosin head to the thin filament (20). Furthermore, substituting the phosphorylatable serines with alanines was also shown to significantly alter myosin head orientation (9). These results indicate that alteration of the RLC NH2 terminus, especially the regions around the phosphorylatable serines, greatly impacts the ability of myosin to interact with actin.

Consistent with this notion, structural studies of myosin thick filaments obtained from human biopsy samples from patients carrying the E22K mutation revealed myosin head disorder when compared with thick filaments from control human fibers (20). RLC phosphorylation has also been observed to affect myosin head orientation in a similar way as the E22K mutation (20), suggesting an important role for the NH2-terminal region of the RLC in head mobility and the ability to bind the thin filament. HCM mutation-induced alterations in myosin head orientation would allow for increased attachment to actin, which is consistent with the increased duty cycle observed here. Thus, alteration in the ability of the myosin heads to bind the thin filament could also be a contributing factor for the NH2-terminal RLC-HCM mutant contractile deficits (17) rather than from a loss in power stroke (39) or load transfer (10, 49).

In transgenic mice, disease-causing mutations of the RLC have shown alterations in contractility and faithfully recapitulated the disease phenotype at the heart level with myocyte disarray and fibrotic lesions (1, 17, 28, 30). In contrast to the results presented here, skinned muscle fibers from transgenic mice expressing E22K (17) and A13T (7, 45) mutant RLC show decreases and increases in force, respectively. Further complicating interpretation of these data, fibers extracted form transgenic mice expressing 10% mutant A13T RLC showed a 25% decrease in ATPase. This dominant effect of A13T RLC protein on myocardial function indicates that higher-order effects of the mutation at the fiber level (myocyte disarray, fibrosis, post-translational modification of contractile proteins) contribute to the observed phenotype. Indeed, endogenous mutant proteins can be posttranslationally modified to help restore normal function (1, 17, 18, 28, 30, 44). The uniqueness of our approach in using recombinant mutant proteins reconstituted with β-myosin heavy chain allows for the study and definition of the initial causative mutation-induced disruptions without the secondary effects that often confound the interpretation. Further, it should be noted that the results found here are particular to the β-myosin isoform and may not reflect the impact these mutations may have on α-myosin, the primary isoform expressed in adult mice. In this study we have determined that the principal contractile defect in the NH2-terminal HCM mutant myosin is a loss in actin sliding velocity due to an increase duty cycle. Unlike the cation-binding mutants or mutants near the COOH terminus, the NH2-terminal mutants do not manifest a severe disruption in strain dependent kinetics.

Given the proximity between the mutations and the RLC phosphorylation site it is conceivable that the mutations may affect the degree of phosphorylation. Consistent with this notion, several disease-linked RLC mutations have been associated with altered RLC phosphorylation(18, 28, 30, 50). Further, phosphorylation of the RLC has been shown to reverse some of biochemical and structural alterations of the isolated mutant RLCs (42). Future studies are needed to address the effectiveness of mutant RLC as a substrate for myosin light chain kinase as well as phosphorylation as a potential compensatory mechanism for mutation-induced alterations in myosin function (50).

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-071778 and HL-108343 (D. Szczesna-Cordary) and HL-077280 (J. R. Moore).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: G.P.F., P.M., K.K., D.S.-C., and J.R.M. conception and design of research; G.P.F. performed experiments; G.P.F. analyzed data; G.P.F. and J.R.M. interpreted results of experiments; G.P.F. prepared figures; G.P.F. and J.R.M. drafted manuscript; G.P.F., P.M., K.K., D.S.-C., and J.R.M. edited and revised manuscript; G.P.F., D.S.-C., and J.R.M. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham TP, Jones M, Kazmierczak K, Liang HY, Pinheiro AC, Wagg CS, Lopaschuk GD, Szczesna-Cordary D. Diastolic dysfunction in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy transgenic model mice. Cardiovasc Res 82: 84–92, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker JE, Brust-Mascher I, Ramachandran S, LaConte LE, Thomas DD. A large and distinct rotation of the myosin light chain domain occurs upon muscle contraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 2944–2949, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burghardt TP, Sikkink LA. Regulatory light chain mutants linked to heart disease modify the cardiac myosin lever arm. Biochemistry 52: 1249–1259, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaudoir BM, Kowalczyk PA, Chisholm RL. Regulatory light chain mutations affect myosin motor function and kinetics. J Cell Sci 112: 1611–1620, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis JS, Satorius CL, Epstein ND. Kinetic effects of myosin regulatory light chain phosphorylation on skeletal muscle contraction. Biophys J 83: 359–370, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickinson MH, Hyatt CJ, Lehmann FO, Moore JR, Reedy MC, Simcox A, Tohtong R, Vigoreaux JO, Yamashita H, Maughan DW. Phosphorylation-dependent power output of transgenic flies: an integrated study. Biophys J 73: 3122–3134, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dumka D, Talent J, Akopova I, Guzman G, Szczesna-Cordary D, Borejdo J. E22K mutation of RLC that causes familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in heterozygous mouse myocardium: effect on cross-bridge kinetics. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H2098–H2106, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farman GP, Gore D, Allen E, Schoenfelt K, Irving TC, de Tombe PP. Myosin head orientation: a structural determinant for the Frank-Starling relationship. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H2155–H2160, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farman GP, Miller MS, Reedy MC, Soto-Adames FN, Vigoreaux JO, Maughan DW, Irving TC. Phosphorylation and the N-terminal extension of the regulatory light chain help orient and align the myosin heads in Drosophila flight muscle. J Struct Biol 168: 240–249, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenberg MJ, Kazmierczak K, Szczesna-Cordary D, Moore JR. Cardiomyopathy-linked myosin regulatory light chain mutations disrupt myosin strain-dependent biochemistry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 17403–17408, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenberg MJ, Mealy TR, Watt JD, Jones M, Szczesna-Cordary D, Moore JR. The molecular effects of skeletal muscle myosin regulatory light chain phosphorylation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 297: R265–R274, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howard J. Molecular motors: structural adaptations to cellular functions. Nature 389: 561–567, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huxley AF, Simmons RM. Proposed mechanism of force generation in striated muscle. Nature 233: 533–538, 1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huxley HE. Sliding filaments and molecular motile systems. J Biol Chem 265: 8347–8350, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Irving T, Bhattacharya S, Tesic I, Moore J, Farman G, Simcox A, Vigoreaux J, Maughan D. Changes in myofibrillar structure and function produced by N-terminal deletion of the regulatory light chain in Drosophila. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 22: 675–683, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Itakura S, Yamakawa H, Toyoshima YY, Ishijima A, Kojima T, Harada Y, Yanagida T, Wakabayashi T, Sutoh K. Force-generating domain of myosin motor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 196: 1504–1510, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kazmierczak K, Muthu P, Huang W, Jones M, Wang Y, Szczesna-Cordary D. Myosin regulatory light chain mutation found in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients increases isometric force production in transgenic mice. Biochem J 442: 95–103, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kerrick WG, Kazmierczak K, Xu Y, Wang Y, Szczesna-Cordary D. Malignant familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy D166V mutation in the ventricular myosin regulatory light chain causes profound effects in skinned and intact papillary muscle fibers from transgenic mice. FASEB J 23: 855–865, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khromov AS, Somlyo AV, Somlyo AP. Thiophosphorylation of myosin light chain increases rigor stiffness of rabbit smooth muscle. J Physiol 512: 345–350, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levine RJ, Yang Z, Epstein ND, Fananapazir L, Stull JT, Sweeney HL. Structural and functional responses of mammalian thick filaments to alterations in myosin regulatory light chains. J Struct Biol 122: 149–161, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lombardi V, Piazzesi G, Reconditi M, Linari M, Lucii L, Stewart A, Sun YB, Boesecke P, Narayanan T, Irving T, Irving M. X-ray diffraction studies of the contractile mechanism in single muscle fibres. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 359: 1883–1893, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maron BJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. JAMA 287: 1308–1320, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maron BJ, Maron MS, Semsarian C. Genetics of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy after 20 years: clinical perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol 60: 705–715, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore JR, Dickinson MH, Vigoreaux JO, Maughan DW. The effect of removing the N-terminal extension of the Drosophila myosin regulatory light chain upon flight ability and the contractile dynamics of indirect flight muscle. Biophys J 78: 1431–1440, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore JR, Krementsova EB, Trybus KM, Warshaw DM. Does the myosin V neck region act as a lever? J Muscle Res Cell Motil 25: 29–35, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore JR, Krementsova EB, Trybus KM, Warshaw DM. Myosin V exhibits a high duty cycle and large unitary displacement. J Cell Biol 155: 625–635, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore JR, Leinwand L, Warshaw DM. Understanding cardiomyopathy phenotypes based on the functional impact of mutations in the myosin motor. Circ Res 111: 375–385, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muthu P, Kazmierczak K, Jones M, Szczesna-Cordary D. The effect of myosin RLC phosphorylation in normal and cardiomyopathic mouse hearts. J Cell Mol Med 16: 911–919, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muthu P, Liang J, Schmidt W, Moore JR, Szczesna-Cordary D. In vitro rescue study of a malignant familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy phenotype by pseudo-phosphorylation of myosin regulatory light chain. Arch Biochem Biophys 552–553: 29–39, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muthu P, Mettikolla P, Calander N, Luchowski R, Gryczynski I, Gryczynski Z, Szczesna-Cordary D, Borejdo J. Single molecule kinetics in the familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy D166V mutant mouse heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48: 989–998, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olsson MC, Patel JR, Fitzsimons DP, Walker JW, Moss RL. Basal myosin light chain phosphorylation is a determinant of Ca2+ sensitivity of force and activation dependence of the kinetics of myocardial force development. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H2712–H2718, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pant K, Watt J, Greenberg M, Jones M, Szczesna-Cordary D, Moore JR. Removal of the cardiac myosin regulatory light chain increases isometric force production. FASEB J 23: 3571–3580, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piazzesi G, Reconditi M, Dobbie I, Linari M, Boesecke P, Diat O, Irving M, Lombardi V. Changes in conformation of myosin heads during the development of isometric contraction and rapid shortening in single frog muscle fibres. J Physiol 514: 305–312, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Purcell TJ, Morris C, Spudich JA, Sweeney HL. Role of the lever arm in the processive stepping of myosin V. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 14159–14164, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rayment I, Holden HM, Whittaker M, Yohn CB, Lorenz M, Holmes KC, Milligan RA. Structure of the actin-myosin complex and its implications for muscle contraction. Science 261: 58–65, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reconditi M, Koubassova N, Linari M, Dobbie I, Narayanan T, Diat O, Piazzesi G, Lombardi V, Irving M. The conformation of myosin head domains in rigor muscle determined by X-ray interference. Biophys J 85: 1098–1110, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reconditi M, Linari M, Lucii L, Stewart A, Sun YB, Narayanan T, Irving T, Piazzesi G, Irving M, Lombardi V. Structure-function relation of the myosin motor in striated muscle. Ann NY Acad Sci 1047: 232–247, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakamoto T, Wang F, Schmitz S, Xu Y, Xu Q, Molloy JE, Veigel C, Sellers JR. Neck length and processivity of myosin V. J Biol Chem 278: 29201–29207, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sherwood JJ, Waller GS, Warshaw DM, Lowey S. A point mutation in the regulatory light chain reduces the step size of skeletal muscle myosin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 10973–10978, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stelzer JE, Patel JR, Moss RL. Acceleration of stretch activation in murine myocardium due to phosphorylation of myosin regulatory light chain. J Gen Physiol 128: 261–272, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szczesna D. Regulatory light chains of striated muscle myosin. Structure, function and malfunction. Curr Drug Targets Cardiovasc Haematol Disord 3: 187–197, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Szczesna D, Ghosh D, Li Q, Gomes AV, Guzman G, Arana C, Zhi G, Stull JT, Potter JD. Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations in the regulatory light chains of myosin affect their structure, Ca2+ binding, and phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 276: 7086–7092, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Szczesna D, Zhao J, Jones M, Zhi G, Stull J, Potter JD. Phosphorylation of the regulatory light chains of myosin affects Ca2+ sensitivity of skeletal muscle contraction. J Appl Physiol 92: 1661–1670, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Szczesna-Cordary D, Guzman G, Ng SS, Zhao J. Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-linked alterations in Ca2+ binding of human cardiac myosin regulatory light chain affect cardiac muscle contraction. J Biol Chem 279: 3535–3542, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Szczesna-Cordary D, Jones M, Moore JR, Watt J, Kerrick WG, Xu Y, Wang Y, Wagg C, Lopaschuk GD. Myosin regulatory light chain E22K mutation results in decreased cardiac intracellular calcium and force transients. FASEB J 21: 3974–3985, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toyoshima YY, Kron SJ, McNally EM, Niebling KR, Toyoshima C, Spudich JA. Myosin subfragment-1 is sufficient to move actin filaments in vitro. Nature 328: 536–539, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uyeda TQ, Abramson PD, Spudich JA. The neck region of the myosin motor domain acts as a lever arm to generate movement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 4459–4464, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uyeda TQ, Kron SJ, Spudich JA. Myosin step size. Estimation from slow sliding movement of actin over low densities of heavy meromyosin. J Mol Biol 214: 699–710, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Veigel C, Schmitz S, Wang F, Sellers JR. Load-dependent kinetics of myosin-V can explain its high processivity. Nat Cell Biol 7: 861–869, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walker LA, Fullerton DA, Buttrick PM. Contractile protein phosphorylation predicts human heart disease phenotypes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 304: H1644–H1650, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Warshaw DM, Guilford WH, Freyzon Y, Krementsova E, Palmiter KA, Tyska MJ, Baker JE, Trybus KM. The light chain binding domain of expressed smooth muscle heavy meromyosin acts as a mechanical lever. J Biol Chem 275: 37167–37172, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]