Abstract

The heart adjusts its power output to meet specific physiological needs through the coordination of several mechanisms, including force-induced changes in contractility of the molecular motor, the β-cardiac myosin (βCM). Despite its importance in driving and regulating cardiac power output, the effect of force on the contractility of a single βCM has not been measured. Using single molecule optical-trapping techniques, we found that βCM has a two-step working stroke. Forces that resist the power stroke slow the myosin-driven contraction by slowing the rate of ADP release, which is the kinetic step that limits fiber shortening. The kinetic properties of βCM are affected by load, suggesting that the properties of myosin contribute to the force-velocity relationship in intact muscle and play an important role in the regulation of cardiac power output.

The cardiac cycle is a tightly regulated process in which the heart generates power during systole and relaxes during diastole. Appropriate power must be generated to effectively pump blood against cardiac afterload. Dysfunction of this cycle has devastating consequences for affected individuals.

Cardiac power output is regulated by several feedback mechanisms (e.g., neuronal, hormonal, mechanical) that ultimately lead to changes in the force and power output of the molecular motor, β-cardiac myosin (βCM). In isolated cardiac fibers and cardiomyocytes, loading the muscle during systole slows contraction and alters power output. It is widely believed that this slowing is partially due to force-induced inhibition of myosin ATPase kinetics, similar to the Fenn Effect in skeletal muscle. However, this hypothesis has not been directly tested at the molecular level. Much of our contemporary view of how power is generated in cardiac muscle is due to in vivo and isolated muscle-fiber studies (1). Substantial progress has been made in understanding the actomyosin interactions required for power generation, but resolving the molecular effects of mechanical load on the ATPase properties of βCM in intact muscle has been challenging. Nevertheless, determining the biophysical parameters that define βCM contractility is key to understanding cardiac regulation and the etiology of several muscle diseases (1).

In vitro assays using isolated contractile proteins have been central to advancing our understanding of contractility, although most experiments have been conducted at low resisting loads that do not mimic working conditions. Elegant optical trapping experiments have imposed loads on small ensembles of murine α-cardiac myosin at subsaturating [ATP] (2), and these experiments suggest that force slows α-cardiac myosin kinetics. The kinetic properties of α-cardiac myosin are substantially different from βCM, the primary isoform in the adult human myocardium (3). Thus, experiments using βCM must be performed to determine the unitary force-dependent kinetic parameters of this key molecular motor. We used optical trapping to measure the working-stroke displacement and force dependence of actin-detachment kinetics of single porcine βCM molecules at saturating ATP concentrations. These experiments allow direct measurement of the force-velocity relationship for single βCM molecules and reveal the mechanism of how loads regulate βCM-driven power output.

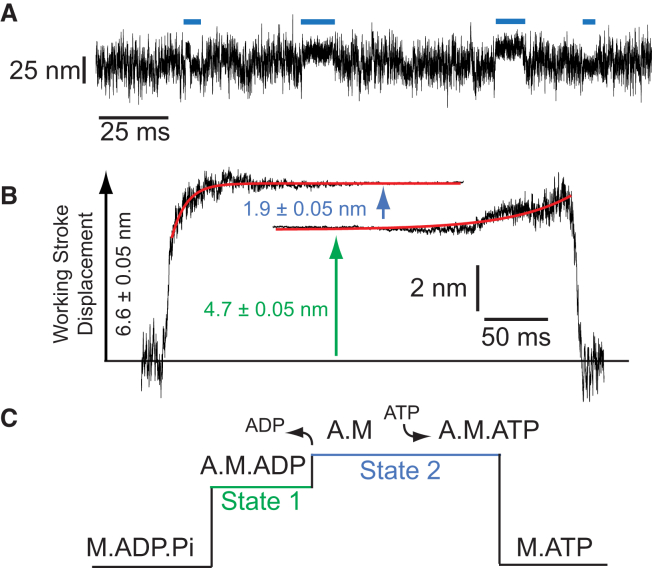

Using the three-bead geometry (4) in which an actin filament is strung between two optically-trapped beads and then lowered over a bead that is sparsely coated with purified full-length porcine ventricular βCM, interactions between single βCM molecules and actin were recorded at 10 μM ATP (Fig. 1 A) (5, 6). Ensemble averages of these interactions were constructed to determine the size and kinetics of the working stroke (7, 8). βCM has an average displacement (6.8 ± 0.04 nm) that is similar to previously characterized muscle myosins (9, 10). Similar to skeletal muscle myosin (10), ensemble averages clearly show that the βCM working stroke is composed of two substeps with average displacements of 4.7 ± 0.05 nm and 1.9 ± 0.05 nm (Fig. 1 B). A single exponential function was fit to the rising-phase of the time-forward ensemble averages, yielding a rate (74 ± 2 s−1) for the transition from state 1 to state 2 (Fig. 1 C). This rate is similar to the biochemical rate of ADP release measured for βCM (64 s−1) (3), indicating that this structural transition is associated with the release of ADP. The rate of the rising phase of the time-reversed ensemble averages (22 ± 0.7 s−1) reports the rate of exit from state 2 and is consistent with the biochemical rate of ATP binding and actomyosin detachment at 10 μM ATP (16 s−1) (3) (Fig. 1 C).

Figure 1.

(A) Representative data trace showing actomyosin displacements generated by βCM at 10 μM ATP. (Blue lines) Individual binding events. (B) Ensemble averages of the βCM working stroke generated from averaging 1295 binding interactions collected at 10 μM ATP. Single exponential functions were fit to the data (red lines) and the reported errors are the standard errors from the fit. (C) Cartoon showing an idealized actomyosin interaction with the corresponding mechanical and biochemical states. To see this figure in color, go online.

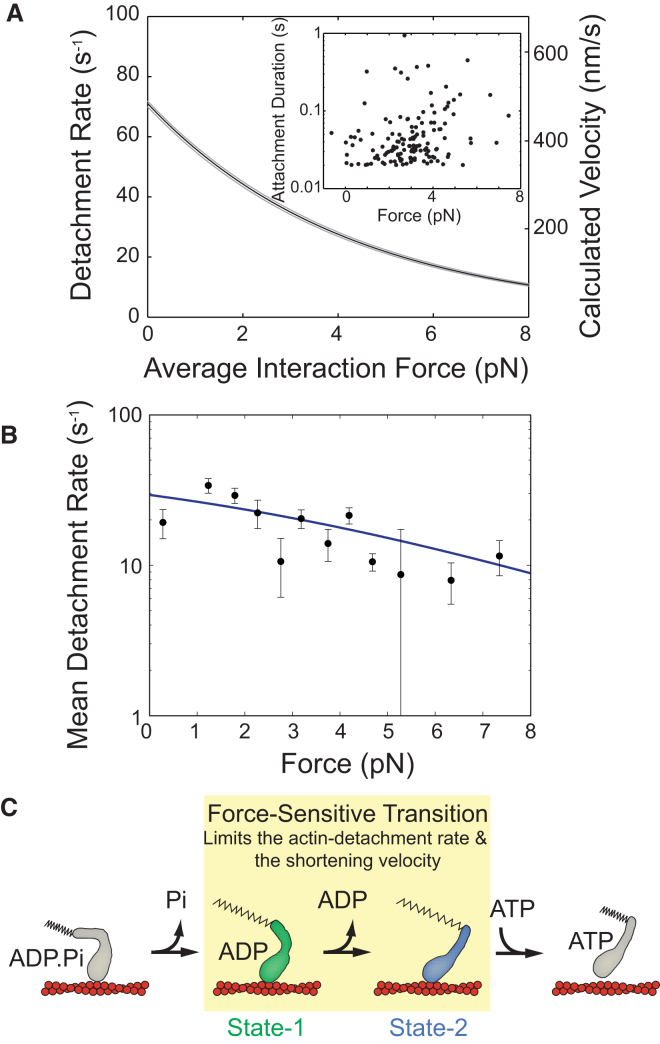

To examine actomyosin detachment kinetics under working conditions, a positional feedback optical clamp was used to apply a dynamic load to the myosin, keeping the myosin at an isometric position during its working stroke (11). We measured the effect of force on the actin-attachment duration at 4 mM Mg.ATP to ensure that the rate of ATP binding is not rate-limiting for detachment. Increases in attachment durations are observed as the force on the myosin is increased (Fig. 2 A, inset). Assuming a two-state model (12), we expect the attachment durations to be exponentially distributed at each force with the force-dependent actin detachment rate, k(F), given by (13)

| (1) |

where k0 is the rate of the primary force-sensitive transition in the absence of force, F is the force on the myosin, ddet is the distance to the transition state (a measurement of force sensitivity), kB is Boltzmann’s constant, and T is the temperature. Maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) fitting Eq. 1 to the data yields a detachment rate (k0 = 71 (−1.0/+0.8 s−1)) that is similar to the rate of ADP release measured for βCM (64 s−1) (3) and the rate of the time-forward ensemble averages (74 ± 2 s−1). Thus, the ADP release step (and the accompanying state-1 to state-2 mechanical transition) is force-sensitive (ddet = 0.97 (−0.014/+0.011) nm). The value of ddet indicates that the ADP release step slows with increasing force, but less than some other characterized myosins (14). Using the values determined from the MLE fitting and the measured size of the working stroke, it is possible to calculate a force-velocity relationship for βCM, assuming the rate of ADP release limits actin motility (Fig. 2 A).

Figure 2.

(A, Inset) Single molecule actomyosin interactions were collected in the presence of the isometric optical clamp. The scatter plot shows 262 binding events. Attachment durations are exponentially distributed at each force. (A) The detachment rate as a function of force as determined by MLE fitting. (Black line) Best fit; (small gray shaded area) 95% confidence interval. (Right axis) Velocity, calculated by multiplying the displacement of the working stroke by the detachment rate. (B) The calculated mean detachment rate as a function of force. Attachment durations were binned according to the average force experienced by the myosin during the binding event. Error bars were calculated via bootstrapping simulations of each force bin. (Blue line) Expected mean detachment rate based on the MLE fitting and the limited temporal resolution of our experiment (see the Supporting Material for details). (C) Proposed model for how force slows shortening velocity. Force inhibits the mechanical transition associated with ADP release, slowing the rate of actomyosin detachment. To see this figure in color, go online.

The MLE fitting of Eq. 1 assumes an exponential distribution of attachment durations at every force. As such, the MLE fitting of the raw data should yield correct values of the parameters k0 and ddet, despite limitations of the temporal resolution of our experiment (see Supporting Material for detailed discussion of MLE fitting). Frequently, groups report the mean attachment duration as a function of force. However, the mean attachment duration at each force will be overestimated because some shorter binding events cannot be resolved. We provide a method for calculating the expected mean detachment rate based on the parameters determined from the MLE fitting, given the limited temporal resolution of the experiment, and verify the robustness of the MLE fitting (see the Supporting Material). For demonstration purposes only, Fig. 2 B shows that the measured mean detachment rate agrees well with the expected mean detachment rate based on the MLE fitting and the temporal resolution of the experiment. It should be emphasized that the relevant dissociation values are obtained from the MLE fitting in Fig. 2 A (see also Figs. S1–S3).

Our data demonstrate that at saturating [ATP], the detachment rate is limited by the ADP release step, which is the same transition that limits fiber shortening velocity (15). We propose that resisting loads slow ADP release and actin detachment by slowing the mechanical transition that accompanies ADP release (Fig. 2 C), thereby reducing the shortening velocity of muscle fibers. Thus, our data demonstrate that the intrinsic force-dependent properties of βCM contribute to the force-velocity relationship in the heart. It is important to note that our proposed mechanism does not rule out additional mechanisms by which force could directly modulate the activity of actomyosin such as force-induced reversal of the power stroke (11) or population of branched pathways (16, 17).

Are the loads in our experiments physiologically relevant to contracting muscle? Modeling of the force per cross-bridge generated in isometric soleus muscle, which contains the βCM isoform, suggests a load of 2–4 pN per myosin (18). At these loads, we expect actin-detachment to slow up to threefold. Interestingly, βCM is substantially less force-sensitive than smooth muscle myosin (ddet = 2.7), suggesting that βCM can generate more power (the product of force and velocity) under load.

In conclusion, our data show that cardiac power output can be directly modulated by force at the level of single myosin molecules. These data will enable the comparison of how molecular changes, such as light-chain phosphorylation, pharmacological treatments, or mutations associated with cardiomyopathies, affect the ability of the myosin to generate power against the afterload.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the American Heart Association (grant No. 14SDG18850009 to M.J.G.) and National Institutes of Health (grant No. R01GM057247 to E.M.O. and grant No. K99HL123623 to M.J.G.).

Editor: James Sellers.

Footnotes

Supporting Materials and Methods, one scheme, three equations, and three figures are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(14)01187-4.

Supporting Citations

References (19, 20) appear in the Supporting Material.

Supporting Material

References and Footnotes

- 1.Spudich J.A. Hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy: four decades of basic research on muscle lead to potential therapeutic approaches to these devastating genetic diseases. Biophys. J. 2014;106:1236–1249. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Debold E.P., Schmitt J.P., Warshaw D.M. Hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy mutations differentially affect the molecular force generation of mouse α-cardiac myosin in the laser trap assay. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007;293:H284–H291. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00128.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deacon J.C., Bloemink M.J., Leinwand L.A. Identification of functional differences between recombinant human α and β cardiac myosin motors. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2012;69:2261–2277. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-0927-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finer J.T., Simmons R.M., Spudich J.A. Single myosin molecule mechanics: piconewton forces and nanometre steps. Nature. 1994;368:113–119. doi: 10.1038/368113a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberg M.J., Lin T., Ostap E.M. Myosin IC generates power over a range of loads via a new tension-sensing mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:E2433–E2440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207811109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laakso J.M., Lewis J.H., Ostap E.M. Myosin I can act as a molecular force sensor. Science. 2008;321:133–136. doi: 10.1126/science.1159419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veigel C., Coluccio L.M., Molloy J.E. The motor protein myosin-I produces its working stroke in two steps. Nature. 1999;398:530–533. doi: 10.1038/19104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen C., Greenberg M.J., Shuman H. Kinetic schemes for post-synchronized single molecule dynamics. Biophys. J. 2012;102:L23–L25. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.01.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tyska M.J., Hayes E., Warshaw D.M. Single-molecule mechanics of R403Q cardiac myosin isolated from the mouse model of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 2000;86:737–744. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.7.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Capitanio M., Canepari M., Bottinelli R. Two independent mechanical events in the interaction cycle of skeletal muscle myosin with actin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:87–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506830102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takagi Y., Homsher E.E., Shuman H. Force generation in single conventional actomyosin complexes under high dynamic load. Biophys. J. 2006;90:1295–1307. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.068429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huxley A.F. Muscle structure and theories of contraction. Prog. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 1957;7:255–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bell G.I. Models for the specific adhesion of cells to cells. Science. 1978;200:618–627. doi: 10.1126/science.347575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenberg M.J., Ostap E.M. Regulation and control of myosin-I by the motor and light chain-binding domains. Trends Cell Biol. 2013;23:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siemankowski R.F., Wiseman M.O., White H.D. ADP dissociation from actomyosin subfragment 1 is sufficiently slow to limit the unloaded shortening velocity in vertebrate muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1985;82:658–662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.3.658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linari M., Caremani M., Lombardi V. A kinetic model that explains the effect of inorganic phosphate on the mechanics and energetics of isometric contraction of fast skeletal muscle. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2010;277:19–27. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Debold E.P., Walcott S., Turner M.A. Direct observation of phosphate inhibiting the force-generating capacity of a miniensemble of myosin molecules. Biophys. J. 2013;105:2374–2384. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.09.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seebohm B., Matinmehr F., Kraft T. Cardiomyopathy mutations reveal variable region of myosin converter as major element of cross-bridge compliance. Biophys. J. 2009;97:806–824. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kielley W.W., Bradley L.B. The relationship between sulfhydryl groups and the activation of myosin adenosinetriphosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 1956;218:653–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenberg M.J., Kazmierczak K., Moore J.R. Cardiomyopathy-linked myosin regulatory light chain mutations disrupt myosin strain-dependent biochemistry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:17403–17408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009619107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.