Abstract

Background

Patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) often complain of persistent fatigue even after conventional therapies such as pharmacotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, or graded exercise therapy. The aim of this study was to investigate in a randomized, controlled trial the feasibility and efficacy of isometric yoga in patients with CFS who are resistant to conventional treatments.

Methods

This trial enrolled 30 patients with CFS who did not have satisfactory improvement after receiving conventional therapy for at least six months. They were randomly divided into two groups and were treated with either conventional pharmacotherapy (control group, n = 15) or conventional therapy together with isometric yoga practice that consisted of biweekly, 20-minute sessions with a yoga instructor and daily in-home sessions (yoga group, n = 15) for approximately two months. The short-term effect of isometric yoga on fatigue was assessed by administration of the Profile of Mood Status (POMS) questionnaire immediately before and after the final 20-minute session with the instructor. The long-term effect of isometric yoga on fatigue was assessed by administration of the Chalder’s Fatigue Scale (FS) questionnaire to both groups before and after the intervention. Adverse events and changes in subjective symptoms were recorded for subjects in the yoga group.

Results

All subjects completed the intervention. The mean POMS fatigue score decreased significantly (from 21.9 ± 7.7 to 13.8 ± 6.7, P < 0.001) after a yoga session. The Chalder’s FS score decreased significantly (from 25.9 ± 6.1 to 19.2 ± 7.5, P = 0.002) in the yoga group, but not in the control group. In addition to the improvement of fatigue, two patients with CFS and fibromyalgia syndrome in the yoga group also reported pain relief. Furthermore, many subjects reported that their bodies became warmer and lighter after practicing isometric yoga. Although there were no serious adverse events in the yoga group, two patients complained of tiredness and one of dizziness after the first yoga session with the instructor.

Conclusions

Isometric yoga as an add-on therapy is both feasible and successful at relieving the fatigue and pain of a subset of therapy-resistant patients with CFS.

Trial registration

University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN CTR) UMIN000009646.

Keywords: Chronic fatigue syndrome, Isometric yoga, Fatigue, Treatment, Fibromyalgia

Background

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is a debilitating disease characterized by persistent fatigue that is not relieved by rest and by other nonspecific symptoms, all of which last for a minimum of six months [1]. The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying CFS are not yet fully understood. Currently, patients with CFS are treated with antidepressants, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and/or graded exercise therapy (GET) [2–5]. However, there are patients who do not fully recover even with these treatments.

Yoga is one of the most commonly accepted mind/body therapies of complementary and alternative medicine and is recommended as an alternative therapy for improving unexplained chronic fatigue [6]. In fact, several studies have demonstrated that yoga is effective in improving the fatigue of patients with cancer [7,8] as well as of healthy subjects [9]. We hypothesized that yoga is also effective in improving the fatigue of patients with CFS. However, as the yoga programs practiced in previously published studies were not uniform, it was difficult to identify which program or which component of yoga is useful for alleviating fatigue. Furthermore, patients with CFS complain of severe fatigue, especially after exertion. Therefore, before starting this study, we discussed the yoga program with yoga instructors to determine which type of practice had the least probability of exacerbating a patient’s fatigue. We selected isometric yoga, as described in the methods section.

The aims of this study were to assess the feasibility of isometric yoga among patients with CFS and to assess the effect of isometric yoga on fatigue and related psychological and physical symptoms of patients with CFS who did not respond to conventional therapies. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the effect of isometric yoga on the fatigue of patients with CFS.

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kyushu University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before they were enrolled.

Subjects

This study enrolled outpatients with CFS who visited the Department of Psychosomatic Medicine of Kyushu University Hospital. Inclusion criteria were the following: (1) the subject’s fatigue did not improve sufficiently with ordinary treatment given in our Department (as an example see [10]), including pharmacotherapy (for example, antidepressants, Japanese traditional herbal medicine [11,12], and/or coenzyme Q10), psychotherapy, and/or GET; in some cases, a four-week inpatient treatment program was also included [10]) for at least six months; (2) the subject was between 20 and 70 years old; (3) the subject’s level of fatigue was serious enough to cause an absence from school or the workplace at least several days a month but not serious enough to require assistance with the activities of daily living; (4) the subject was able to fill out the questionnaire without assistance; (5) the subject could sit for at least 30 minutes; and (6) the subject could visit Kyushu University Hospital regularly every two or three weeks. Subjects were excluded if (1) their fatigue was due to a physical disease such as liver, kidney, heart, respiratory, endocrine, autoimmune, or malignant disease, severe anemia, electrolyte abnormalities, obesity, or pregnancy; and (2) they had previously practiced yoga. The diagnosis of CFS was made for patients meeting the diagnostic criteria of the 1994 international research case definition of CFS [1]. Patients with idiopathic chronic fatigue were not included in this study.

Methods

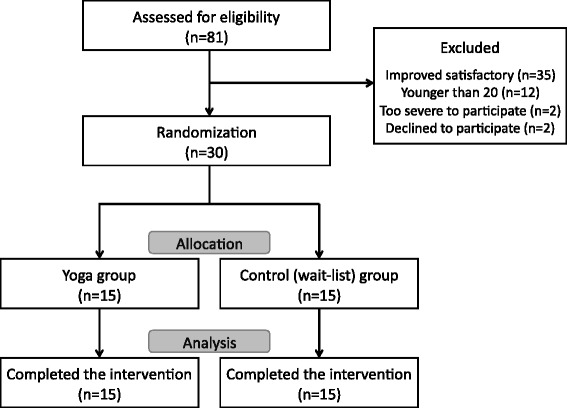

Following enrollment, eligible participants were randomized using a computer-generated randomization list to receive either an isometric yoga practice together with conventional pharmacotherapy group (yoga group, n = 15) or to a conventional pharmacotherapy alone group (wait-list control group, n = 15) for approximately two months. As the patients visited the hospital every two or three weeks, the intervention period lasted 9.2 ± 2.5 (mean ± standard deviation (SD)) weeks after the start of the intervention (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart outlining participation in this study.

Development of the yoga program

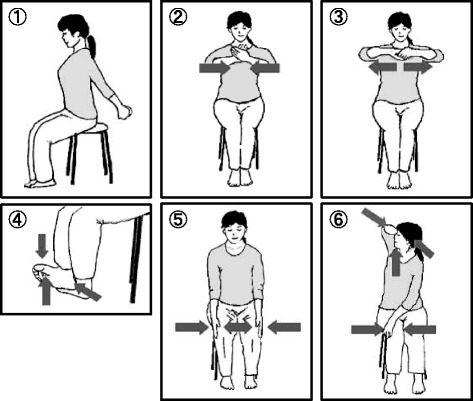

Before starting this trial, we consulted yoga instructors to identify a program that would satisfy the following requirements. Firstly, because patients with CFS have severe fatigue, it should not exacerbate their symptoms or cause post-exertion malaise. Secondly, because the patients are deconditioned, it should also act as an exercise therapy. Thirdly, because the patients’ concentration and short-term memory are impaired, it should be simple and easy to do. Fourthly, because the patients would be treated at the hospital, not at a yoga studio, it must be able to be practiced in an outpatient setting, where space is limited. To satisfy these requirements, we determined that the trial would include isometric yoga, or an isometric yogic breathing exercise, as a treatment for patients with CFS. Isometric yoga, which was developed by Dr. Keishin Kimura, differs from traditional yoga postures in several ways. The predominant difference is that the poses consist mainly of isometric muscle contractions. Since the patients can change resistance depending on their fatigue level, we thought that isometric yoga would help prevent worsened fatigue. These poses do not include isotonic muscular contractions or strong stretching and require less physical flexibility. Therefore, we hypothesized that practicing this form of yoga would be easy on the patients, preventing over-stretching, which is detrimental and may increase pain. However, as are traditional yoga poses, these poses are conducted slowly in accordance with breathing and with awareness of inner sensations. We intentionally avoided standing postures, because a considerable number of CFS patients suffer from orthostatic intolerance, including postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome [13]. This 20-minute yoga program can be practiced in a sitting position and consists of three parts. First, patients are asked to be aware of their spontaneous breathing for one minute. Next, they practice six poses. These poses are very slow movements that are coordinated with the timing of breathing, with or without sounds, and isometric exercise at 50% of the patient’s maximal physical strength. Lastly, the patients practice abdominal breathing for one minute (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Illustration of the six poses of the isometric yoga program used in this study. The 20-minute isometric yoga program consisted of three parts. 1) The patients practiced being aware of their spontaneous breathing for one minute. 2) The patients practiced six isometric poses 4–6 times: (i) stretching both arms behind the back; (ii) pushing the palms against each other; (iii) pulling the palms away from each other; (iv) pushing the feet against each other; (v) pushing both knees inward with hands on the outside; and (vi) twisting. 3) The patients practiced abdominal breathing for one minute. The postures were practiced slowly in association with exhalation or inhalation with 50% of the maximal physical strength. After the postures were repeated 4–6 times, the patients decreased their physical exertion and returned slowly to the basic position while exhaling.

Yoga intervention

Patients in the yoga group practiced isometric yoga in a quiet room for 20 minutes on a one-to-one basis with an instructor who has over 30 years of experience. The sessions occurred between 2 pm and 4 pm on the day they visited the hospital. In this program, the yoga instructor was not allowed to use background music, which is often used in the yoga studio to facilitate the participants’ relaxation, because many patients with CFS are sensitive to sounds. Before and after practicing isometric yoga, the doctors in charge checked the patient’s condition and recorded any adverse events or any changes caused by practicing isometric yoga. In addition to receiving a private lesson, the participants were asked to practice this program on non-class days if they could, with the aid of a digital videodisc and a booklet. Most patients visited their doctor every two to three weeks during the intervention period. Therefore, all patients practiced isometric yoga at least four times (mean ± SD, 5.6 ± 1.7 times) with the instructor during the intervention period. Basically, all patients practiced the same 20-min program, both with an instructor and at home. However, the program was modified on a patient-to-patient basis, in most cases skipping a certain pose or decreasing the number of repetitions of poses, depending on the severity of their fatigue and the pain associated with the pose.

Outcome assessment

To assess the acute effects of isometric yoga, the fatigue (F) and vigor (V) scores of the Profile of Mood States (POMS) questionnaire [14] were assessed immediately before and after the final 20-minute session of isometric yoga with the instructor. To assess the chronic effects of isometric yoga, fatigue was assessed with Chalder’s fatigue scale (FS) [15] before and after the intervention period in the yoga and control groups. Chalder’s FS is a well-validated, self-reported scale that measures the physical and mental symptoms of fatigue. In the yoga group, the assessments were conducted just before practicing yoga. Patients in this group also completed the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 8, standard version (SF-8™) before and after the intervention period to assess their health-related quality of life (QOL) [16]. Questionnaires were collected by a nurse.

Adverse events and adherence

Adverse events were monitored in two ways. First, at each visit to the hospital, the doctors in charge determined if a subject experienced any uncomfortable symptoms after practicing yoga with the instructor. Second, patients in the yoga group were asked to keep a “yoga diary,” in which they could record the amount of time they practiced and how they felt after practicing yoga. On the day of the visit, before the patient practiced yoga with the instructor, the doctors checked the diary and determined if the patient had had any symptoms of discomfort. After the intervention period, the diary was collected and checked to determine how often the subjects had practiced yoga at home.

Statistical analyses

The data are presented as the mean ± SD. The differences in the outcome measures were tested by two-way, repeated measures, analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the mean scores. Two comparisons were made: one compared the scores of the yoga group to those of the control group; the other compared the scores measured before the intervention to those measured after. The differences in the patients’ POMS, Chalder’s FS, and SF-8 scores measured before and after the intervention were tested by use of a paired-sample t test. Between-group differences in age and in the POMS, Chalder’s FS, and SF-8 scores measured before and after the intervention were tested by use of an independent-sample t test. Two-tailed tests were used. Fisher’s exact probability test was also used when appropriate. Data were analyzed by using SPSS for Windows, V.17.

Results

Participants

The study comprised 30 subjects, with 15 in the yoga group (age range: 24–60 years; mean age (mean ± SD): 38.0 ± 11.1 years; 3 men) and 15 in the control group (age range: 20–59 years; mean age: 39.1 ± 14.2 years; 3 men). All patients completed the study. There were no significant differences in age, sex, or Chalder’s FS total and subscale scores measured before the intervention between the yoga group and the control group (Table 1). The mean Chalder’s FS score at the first hospital visit of both groups was 30.8 ± 4.5.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants

| Yoga group | Control group | |

|---|---|---|

| Number(m:f)# | 15(3:12) | 15(3:12) |

| Age (years)* | 38.0 ± 11.1 | 39.1 ± 14.2 |

| Chalder’s fatigue scale, Physical fatigue* | 16.4 ± 3.5 | 16.5 ± 3.4 |

| Chalder’s fatigue scale, Mental fatigue* | 9.5 ± 3.5 | 9.7 ± 3.2 |

| Chalder’s fatigue scale, Total score* | 25.9 ± 6.1 | 26.1 ± 6.2 |

The data shown are the mean ± standard deviation (SD). #Not significant by the Fisher exact probability test. *Not significant by an independent-sample t test.

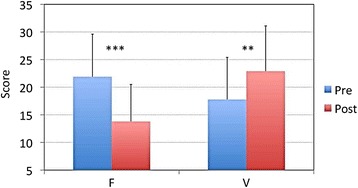

Short-term effects of isometric yoga on fatigue and vigor

We assessed the short-term effects of isometric yoga on fatigue by comparing the POMS F and V scores before and after the patients completed the final 20-minute session of isometric yoga with the instructor. We used the POMS because the Chalder’s FS is not appropriate for evaluating short-term changes in fatigue. Practicing isometric yoga significantly decreased the mean F score (from 21.9 ± 7.7 to 13.8 ± 6.7, P < 0.001) and increased the mean V score (from 17.8 ± 7.6 to 22.9 ± 8.2, P = 0.002) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Acute effects of isometric yoga on fatigue and vigor. A comparison of the fatigue (F) and vigor (V) scores of the Profile of Mood States (POMS) questionnaire for participants in the yoga group before (pre, blue) and immediately after (post, red) the final 20-minute session of isometric yoga with the instructor. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 (paired t test).

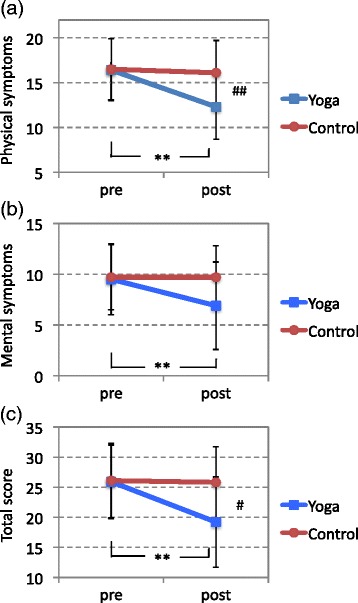

Long-term effects of isometric yoga on fatigue

To assess the long-term effects of regular practice of isometric yoga on fatigue, we compared the Chalder’s FS total score and the subscale scores for physical and mental symptoms of the control group to those of the yoga group before and approximately two months after the intervention. At baseline, the three scores did not differ significantly between the two groups.

We observed a significant main effect of time in the repeated measure ANOVA for the total score and for the two subscores (total score; f(1) = 12.4, P = 0.001: physical symptoms subscore; f(1) = 11.0, P = 0.002: and mental symptoms subscore; f(1) = 8.6, P = 0.007). We also found a significant interaction between the intervention and time (total score; f(1) = 10.2, P = 0.003: physical symptoms subscore; f(1) = 7.9, P = 0.009: and mental symptoms subscore; f(1) = 8.6, P = 0.007) (Figure 4 and Table 2). This finding indicates that patients who practiced yoga experienced a greater improvement in fatigue than did those who did not. The main effect for group was not significant for any score (total score; f(1) = 2.5, P = 0.124: physical symptoms subscore; f(1) = 2.9, P = 0.099: and mental symptoms subscore: f(1) = 1.4, P = 0.252).

Figure 4.

Chronic effects of isometric yoga on fatigue. Chalder’s Fatigue Scale (FS) subscale scores for physical symptoms (a), mental symptoms (b), and FS total scores (c) of the yoga and control groups. **P < 0.01 for differences between the pre- and post-intervention scores (paired-sample t test). # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01 for differences in the scores between the yoga and control groups (independent-sample t test).

Table 2.

Changes in Chalder’s Fatigue Scale (FS) subscale and total scores from baseline to post-intervention of patients in the yoga group compared with the score changes of those in the control group

| Chalder ’ s fatigue scale | Yoga group mean (SD) | Control group mean (SD) | Significance of change (P values) Within - group | Time x group interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yoga group | Control group | ||||

| Physical symptoms | |||||

| Pre-intervention | 16.4 (3.5) | 16.5 (3.4) | 0.004 | 0.779 | 0.009 |

| Post-intervention | 12.3 (3.8) | 16.1 (3.6) | |||

| Mental symptoms | |||||

| Pre-intervention | 9.5 (3.5) | 9.7 (3.2) | |||

| Post-intervention | 6.9 (4.4) | 9.7 (3.1) | 0.004 | 0.395 | 0.007 |

| Total score | |||||

| Pre-intervention | 25.9 (6.1) | 26.1 (6.2) | |||

| Post-intervention | 19.2 (7.5) | 25.8 (5.9) | 0.002 | 0.550 | 0.003 |

Tested with repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by post-hoc, within-group, paired-sample t tests.

At the time of the post-intervention evaluation, both the physical symptoms subscale score and the total score of the yoga group were significantly lower than those of the control group (P = 0.005, P = 0.022, respectively by the independent-sample t test). In the control group, neither the total score nor the two subscores differed significantly between the pre- and post-intervention evaluations. In contrast, in the yoga group the mean physical and mental symptoms subscores and the mean FS total score decreased significantly after the intervention period (P = 0.004, P = 0.004, P = 0.002, respectively, by the paired-sample t test; Figure 4).

Effect of regular practice of isometric yoga on health-related QOL

To assess if the regular practice of yoga affects health-related QOL, we compared the SF-8TM scores of participants in the yoga group before and after the intervention. At baseline, all subscale scores were less than 50, suggesting that the QOL of patients with CFS is lower than that of the average Japanese population. Among the 10 subscale scores, the mean scores for three increased significantly after regular practice of isometric yoga: bodily pain (BP, from 41.3 ± 6.7 to 48.1 ± 7.9, P = 0.0001), general health (GH, from 39.3 ± 5.3 to 43.6 ± 6.0, P = 0.002), and physical component summary (PCS, from 35.8 ± 7.2 to 40.6 ± 4.7, P = 0.024) (Table 3). These data suggest that yoga relieved the patients’ pain and improved their general health.

Table 3.

Changes in Short-Form 8 (SF-8) scores obtained before (pre-) and after (post-) the intervention for participants in the yoga group

| Pre | Post | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning (PF) | 39.6 ± 9.1 | 42.5 ± 7.1 | n.s. |

| Role physical (RP) | 34.4 ± 8.4 | 38.4 ± 6.4 | n.s. |

| Bodily pain (BP) | 41.3 ± 6.7 | 48.1 ± 7.9 | P = 0.0001 |

| General health perception (GH) | 39.3 ± 5.3 | 43.6 ± 6.0 | P = 0.0021 |

| Vitality (VT) | 43.7 ± 4.9 | 43.5 ± 6.1 | n.s. |

| Social functioning (SF) | 37.6 ± 7.8 | 37.6 ± 7.8 | n.s. |

| Role emotional (RE) | 39.2 ± 12.6 | 44.4 ± 9.3 | n.s. |

| Mental health (MH) | 45.8 ± 9.5 | 46.8 ± 9.5 | n.s. |

| Physical component summary (PCS) | 35.8 ± 7.2 | 40.6 ± 4.7 | P = 0.024 |

| Mental component summary (MCS) | 44.1 ± 8.5 | 44.5 ± 7.9 | n.s. |

The data shown are the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The P values assess the differences in scores between the pre- and post-intervention periods (paired-sample t test).

Safety and adverse events

At the hospital, one female subject complained of dizziness after her first yoga session. However, she did not require any specific treatment and she did not experience any negative symptoms in the subsequent sessions. After the first yoga session, two patients reported that they felt tired because they had to concentrate and follow the instructions. In subsequent sessions, neither reported that they experienced this symptom. None of the other patients reported any adverse symptoms. During the home practice, two patients reported that they felt light-headed when they practiced yoga with their eyes closed or on bad days, but not with their eyes open or on good days. Finally, none of the patients reported disabling post-exertion malaise after they practiced yoga.

Other patient reported outcomes

The short-term effects commonly reported by the patients after practicing isometric yoga included a feeling of warmth (n = 11) and lightness (n = 8). One subject mentioned that these benefits lasted for one hour. Seven patients reported that they felt more calm, relaxed, and worry-free. Five patients reported pain relief during their yoga practice. Two patients who have fibromyalgia syndrome as well as CFS skipped the arm-stretching pose because it was difficult and painful for them. They reported that, in the beginning, practicing yoga caused a transient increase in pain because they had to focus on the inner sensations of their bodies. However, as their practice proceeded, they were able to become detached from the pain, and they noticed that the severity of the pain decreased during a yoga session. Regarding the long-term effects, seven patients reported that they now noticed how tense they were in their daily lives and how helpful it was to release muscular tension during yoga. Two patients reported “After regular practice of yoga, I started to wake up more easily in the morning, which had been hard, because tiredness in the morning decreased.”

Adherence

Adherence was very good overall. All patients practiced yoga with an instructor when they visited the hospital. Fourteen of the 15 patients kept yoga diaries. Based on the records in their diaries, these 14 patients practiced isometric yoga at home for a mean of 5.8 ± 1.8 days/week and 5.7 ± 1.8 days/week during the first and last weeks of the intervention period, respectively.

Satisfaction

Fourteen of the 15 patients cited high satisfaction and described isometric yoga as being useful and helpful. One subject reported that she did not want to continue her yoga practice after the intervention period because she was afraid to close her eyes and to see inside.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that isometric yoga together with conventional therapy was more effective in relieving fatigue than was conventional therapy alone in patients with CFS who did not respond adequately to conventional therapy. To our knowledge, this is the first clinical trial that assessed the effects of yoga on the fatigue of CFS patients.

The first aim of this study was to assess the feasibility of isometric yoga as a treatment for CFS. Some patients with CFS experience adverse events such as worsening of fatigue and physical function even when treated with conventional therapies such as CBT and GET [17]. Although two patients in this study complained of tiredness at the first yoga session, they did not have this complaint after they became accustomed to the procedures. Participants had neither serious adverse events nor post-exertion malaise lasting for more than 24 hours. Furthermore, this study exhibited an excellent level of adherence and participant satisfaction. Taken together, our results suggest that an isometric yoga program is both feasible and acceptable for patients with CFS.

Our results also indicate that isometric yoga can significantly improve fatigue, enhance vigor, reduce pain, and improve QOL, and thus may offer a promising new treatment modality for patients with therapy-resistant CFS. The isometric yoga intervention reduced Chalder’s FS scores, especially the physical symptoms subscore. It also improved the BP, GH, and PCS subscores of the SF-8, although it did not improve the mental component summary subscore. Therefore, isometric yoga may improve the physical components of CFS, including physical fatigue or pain, more effectively than the psychological ones. Interestingly, isometric yoga improved pain as well as fatigue. In the yoga group, two patients who were diagnosed with both CFS and fibromyalgia syndrome also reported pain relief. Therefore, isometric yoga might be an effective treatment for both conditions.

Some patients reported these benefits even just after their first session with an instructor. In contrast, others reported adverse events such as dizziness in the beginning. For some patients, it was an effort to memorize the procedures. However, as they practiced, they eventually felt the beneficial effects described above. In most cases, the patients began to feel beneficial effects within one month of practicing isometric yoga, as determined from their yoga diary and interviews.

Previous studies have demonstrated that yoga improves the fatigue of patients with cancer [7]. Although the precise mechanisms of cancer-related fatigue are not yet fully understood, several common mechanisms are suggested to exist between cancer-related fatigue and the fatigue associated with CFS. These include dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, disruption of circadian rhythms, and misregulation of cytokine expression [18–23]. Yoga has been reported to reduce serum levels of cortisol [24] and proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 [25,26]. It also increases heart rate variability and shifts the autonomic nervous system from a state predominated by sympathetic activity to one predominated by parasympathetic activity [27,28]. All of these changes may contribute to the beneficial effects of isometric yoga, one of which is reduced fatigue. As many patients reported that their bodies became warmer during a yoga session, isometric yoga may improve systemic circulation, and this physiological change might also reduce the pain and fatigue of CFS. However, the mechanisms behind the beneficial effects of this isometric yoga program are not fully understood yet. Therefore, these will be the focus of a future study. We have already investigated the changes in autonomic functions and in the blood levels of several biomarkers, the results of which will be published soon.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Firstly, the effects of yoga were evaluated for patients (1) whose fatigue level was not serious enough to require assistance with the activities of daily living, and (2) whose fatigue did not recover fully with ordinary treatment for more than six months. Secondly, we customized the yoga program for the patients in this study. Therefore, further studies are necessary to determine if we can generalize these findings to all patients with CFS or to any kind of yoga program. Thirdly, as this study evaluated the feasibility of a yoga program, we assessed the effects of isometric yoga for a relatively small number of patients and for a short intervention period. Two months might not be sufficient to fully evaluate the feasibility and the effects of yoga. Future studies should evaluate the long-term effects of isometric yoga. Finally, one subject did not want to continue practicing isometric yoga after the intervention period. This patient experienced psychological trauma at a young age and had a difficult life after that. Therefore, future studies should evaluate and treat comorbid psychiatric diseases, especially posttraumatic stress disorder, before considering treatment with yoga.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that a combination therapy consisting of isometric yoga and pharmacotherapy is feasible and that it can relieve the fatigue and pain of patients with CFS who are resistant to conventional therapy. Further studies are needed to determine the mechanisms by which isometric yoga improves fatigue.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by a Health and Labour Sciences Research Grant for integrative medicine to TO (H24-Iryo-Ippan-025 and H26-Togo-Ippan-008). We would like to thank Ms. Hisako Wakita, a yoga instructor, for her enthusiastic instruction. We also thank Ms. Aiko Kishi and Dr. Keishin Kimura for their cooperation.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- BP

Bodily pain

- CFS

Chronic fatigue syndrome

- CBT

Cognitive behavioral therapy

- F

Fatigue

- GET

Graded exercise therapy

- GH

General health perception

- MCS

Mental component summary

- MH

Mental health

- SD

Standard deviation

- SF

Social functioning

- SF-8

Short form-8

- PF

Physical functioning

- PCS

Physical component summary

- POMS

Profile of mood states

- QOL

Quality of life

- RE

Role emotional

- RP

Role physical

- V

Vigor

- VT

Vitality

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

TO designed the study protocol, treated patients, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. TO consulted with Dr. Keishin Kimura and Ms. Hisako Wakita to develop the isometric yoga program for CFS patients. TT also treated patients. TT and TC assisted with data collection. NS looked over the study. TC, BL, and KO assisted with data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Takakazu Oka, Email: oka-t@cephal.med.kyushu-u.ac.jp.

Tokusei Tanahashi, Email: tanatok@cephal.med.kyushu-u.ac.jp.

Takeharu Chijiwa, Email: cidiwa@cephal.med.kyushu-u.ac.jp.

Battuvshin Lkhagvasuren, Email: lbattuvshin@yahoo.de.

Nobuyuki Sudo, Email: nobuyuki@med.kyushu-u.ac.jp.

Kae Oka, Email: okakae@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, Sharpe MC, Dobbins JG, Komaroff A. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:953–959. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-12-199412150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price JR, Mitchell E, Tidy E, Hunot V: Cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome in adults.Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD001027. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD001027.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Reid S, Chalder T, Cleare A, Hotopf M, Wessely S. Chronic fatigue syndrome. Clin Evid. 2011;05:1101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White PD, Goldsmith KA, Johnson AL, Potts L, Walwyn R, DeCesare JC, Baber HL, Burgess M, Clark LV, Cox DL, Bavinton J, Angus BJ, Murphy G, Murphy M, O'Dowd H, Wilks D, McCrone P, Chalder T, Sharpe M. Comparison of adaptive pacing therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, graded exercise therapy, and specialist medical care for chronic fatigue syndrome (PACE): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;377:823–836. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60096-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Cauwenbergh D, De Kooning M, Ickmans K, Nijs J. How to exercise people with chronic fatigue syndrome: evidence-based practice guidelines. Eur J Clin Invest. 2012;42:1136–1144. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2012.02701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bentler SE, Hartz AJ, Kuhn EM. Prospective observational study of treatments for unexplained chronic fatigue. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:625–632. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v66n0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bower JE, Garet D, Sternlieb B, Ganz PA, Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Greendale G. Yoga for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2012;118:3766–3775. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carson JW, Carson KM, Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Seewaldt VL. Yoga of Awareness program for menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors: results from a randomized trial. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:1301–1309. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0587-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshihara K, Hiramoto T, Oka T, Kubo C, Sudo N. Effect of 12 weeks of yoga training on the somatization, psychological symptoms, and stress-related biomarkers of healthy women. Biopsychosoc Med. 2014;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1751-0759-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oka T, Kanemitsu Y, Sudo N, Hayashi H, Oka K. Psychological stress contributed to the development of low-grade fever in a patient with chronic fatigue syndrome: a case report. Biopsychosoc Med. 2013;7:7. doi: 10.1186/1751-0759-7-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oka T, Okumi H, Nishida S, Ito T, Morikiyo S, Kimura Y, Murakami M. Effects of Kampo on functional gastrointestinal disorders. Biopsychosoc Med. 2014;8:5. doi: 10.1186/1751-0759-8-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okumi H, Koyama A. Kampo medicine for palliative care in Japan. Biopsychosoc Med. 2014;8:6. doi: 10.1186/1751-0759-8-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoad A, Spickett G, Elliott J, Newton J. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome is an under-recognized condition in chronic fatigue syndrome. QJM. 2008;101:961–965. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcn123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNair D, Lorr M, Droppleman L. Mannual for the Profile of Mood States (POMS) San Diego: Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T, Watts L, Wessely S, Wright D, Wallace EP. Development of a fatigue scale. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37:147–153. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90081-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukuhara S, Suzukamo Y. Mannual of the SF-8 Japanese version. Kyoto: Institute for Health Outcomes & Process Evaluation Research; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dougall D, Johnson A, Goldsmith K, Sharpe M, Angus B, Chalder T, White P. Adverse events and deterioration reported by participants in the PACE trial of therapies for chronic fatigue syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2014;77:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryan JL, Carroll JK, Ryan EP, Mustian KM, Fiscella K, Morrow GR. Mechanisms of cancer-related fatigue. Oncologist. 2007;12(Suppl 1):22–34. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powell DJ, Liossi C, Moss-Morris R, Schlotz W. Unstimulated cortisol secretory activity in everyday life and its relationship with fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome: a systematic review and subset meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:2405–2422. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wyller VB, Helland IB. Relationship between autonomic cardiovascular control, case definition, clinical symptoms, and functional disability in adolescent chronic fatigue syndrome: an exploratory study. Biopsychosoc Med. 2013;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1751-0759-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lorusso L, Mikhaylova SV, Capelli E, Ferrari D, Ngonga GK, Ricevuti G. Immunological aspects of chronic fatigue syndrome. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8:287–291. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oka T. Influence of psychological stress on chronic fatigue syndrome. Adv Neuroimmune Biol. 2013;4:301–309. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meeus M, Mistiaen W, Lambrecht L, Nijs J. Immunological similarities between cancer and chronic fatigue syndrome: the common link to fatigue? Anticancer Res. 2009;29:4717–4726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamei T, Toriumi Y, Kimura H, Ohno S, Kumano H, Kimura K. Decrease in serum cortisol during yoga exercise is correlated with alpha wave activation. Percept Mot Skills. 2000;90:1027–1032. doi: 10.2466/pms.2000.90.3.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pullen PR, Nagamia SH, Mehta PK, Thompson WR, Benardot D, Hammoud R, Parrott JM, Sola S, Khan BV. Effects of yoga on inflammation and exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2008;14:407–413. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Christian L, Preston H, Houts CR, Malarkey WB, Emery CF, Glaser R. Stress, inflammation, and yoga practice. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:113–121. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181cb9377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Streeter CC, Gerbarg PL, Saper RB, Ciraulo DA, Brown RP. Effects of yoga on the autonomic nervous system, gamma-aminobutyric-acid, and allostasis in epilepsy, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Med Hypotheses. 2012;78:571–579. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balasubramaniam M, Telles S, Doraiswamy PM. Yoga on our minds: a systematic review of yoga for neuropsychiatric disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2012;3:117. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]