Abstract

Background

For over 50 years, methadone has been prescribed to opioid-dependent individuals as a pharmacological approach for alleviating the symptoms of opioid withdrawal. However, individuals prescribed methadone sometimes require additional interventions (e.g., counseling) to further improve their health. This study undertook a realist synthesis of evaluations of interventions aimed at improving the psychosocial and employment outcomes of individuals on methadone treatment, to determine what interventions work (or not) and why.

Methods

The realist synthesis method was utilized because it uncovers the processes (or mechanisms) that lead to particular outcomes, and the contexts within which this occurs. A comprehensive search process resulted in 31 articles for review. Data were extracted from the articles, and placed in four templates to assist with analysis. Data analysis was an iterative process and involved comparing and contrasting data within and across each template, and cross checking with original articles to determine key patterns in the data.

Results

For individuals on methadone, engagement with an intervention appears to be important for improved psychosocial and/or employment outcomes. The engagement process involves attendance at interventions as well as an investment in what is offered. Three intervention contexts (often in some combination) support the engagement process: a) client-centered contexts (or those where clients’ psychosocial and/or employment needs/issues/skills are recognized and/or addressed); b) contexts which address clients’ socio-economic conditions and needs; and, c) contexts where there are positive client-counselor and/or peer relationships. There is some evidence that sometimes ongoing engagement is necessary to maintain positive outcomes. There is also some evidence that complete abstinence from drugs (e.g., cocaine, heroin) is not necessary for engagement.

Conclusions

It is important to consider how the contexts of interventions might elicit and/or support clients’ engagement. Further research is needed to explore how an individual’s background (e.g., involvement with different interventions over an extended period) may influence engagement. Long-term engagement may be necessary to sustain some positive outcomes although how long is unclear and requires further research. Engagement can occur without complete abstinence from such drugs as cocaine or heroin, but additional research is required as engagement may be influenced by the extent and type of drug use.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s40359-014-0026-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Methadone treatment, Engagement, Realist synthesis, Opioids, Opiates, Employment outcomes, Psychosocial health, Client-centered, Socio-economic conditions, Positive relationships

Background

For over 50 years methadone has been prescribed to opioid-dependent individuals as a pharmacological treatment for opioid dependence (Grönbladh and Öhlund 2010; Fischer 2000) as it reduces the symptoms of opioid withdrawal and opioid cravings (King et al. 2002; Prince Edward Island Department of Health 2008; Reist 2010). Opioid dependence is more than a heavy use of opioids; it is a chronic pattern of use with complex physiological, psychological and social impacts that affect individual users, their families and communities (Berkman and Wechsberg 2007; WHO, UNODC, UNAIDS 2004; Prince Edward Island Department of Health 2008; Reist 2010). The efficacy of methadone is well established when taken at the recommended dosage, and long-term maintenance treatment has been associated with such outcomes as reduced use of opioids and reduced criminal activity (Reist 2010; Ward et al. 1994; Gossop 2006; Gossop et al. 2001; SACDM Methadone Project Group 2007).

Although methadone is a well-established pharmacological treatment, individuals often require additional social interventions such as counseling services or other support services, to help improve their health and quality of life (Abbott et al. 1999; Berkman and Wechsberg 2007). Various social interventions targeting individuals on methadone have been implemented in different places. However, at the time of this study, and to the best of our knowledge, there were no systematic reviews of evaluations of social interventions specifically aimed at improving the psychosocial health and employment outcomes of individuals on methadone. Our research was aimed at filling this gap because of the importance of psychosocial health and employment to individuals’ health and quality of life.

The research team was composed of community workers providing services to people on methadone (e.g., individuals working in an AIDS [Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome] organization or needle exchange program), policy-makers in the area of substance use, and academic researchers from various disciplines (e.g., health promotion, social work, pharmacy, psychology, epidemiology). The expertise of team members spanned the areas of harm reduction, substance use, and the health of marginalized populations. Originally, our research question focused on evaluations of interventions aimed at methadone retention and/or improving the physical, social, and mental/emotional health outcomes of individuals on methadone. However, as we conducted our search of evaluations it became clear that we needed to refine our review given the number of evaluations. It also became clear that a number of evaluations included employment outcomes as a marker of improved health or quality of life. Therefore, we focused on evaluations of interventions aimed at improving the psychosocial (e.g., self-esteem, positive social networks) and/or employment (e.g., hours of paid labour) outcomes of individuals on methadone. The key question was: What formal interventions work (or not) for individuals on methadone to improve their psychosocial health and/or employment outcomes? The term formal interventions was defined as interventions that are formally planned and implemented (and usually funded) as opposed to informal interventions such as those developed and implemented by family members. We focused on evaluations from 1980 to 2011. Articles from 1980 on were included because this is when “there was growing demand for treatment and mounting evidence of the merits of methadone treatment” (Reist 2010, p. 2). The search process began in December 2011.

Methods

Rationale for using the realist synthesis

The realist synthesis method was utilized because, unlike a meta-analysis, the realist approach goes beyond an assessment of what works and seeks to understand why social interventions work (or not) (Wong et al. 2011; Wong et al. 2012). Understanding why social interventions work is critical to help guide policy makers and practitioners in determining the contexts and resources needed “to most likely…produce the desired outcome” (Wong et al. 2013). The realist approach accepts that social interventions are complex and messy given that they consist of “multiple human components (teachers, learners, etc.) that interact in a non-linear fashion to produce outcomes which are highly context dependent” (Wong et al. 2010).

A key aim of a realist synthesis is to explain why interventions lead to certain outcomes in some contexts and not others, and why they might work for some sub-populations and not others (Pawson et al. 2005). The realist synthesis “adopts a theory-driven approach to evidence synthesis, underpinned by a realist philosophy of science and causality” (Rycroft-Malone et al. 2014, p. 3). As Rycroft-Malone et al. (2014) explain,

Causal explanations are expressed as contingent relationships between mechanisms (changes in participants’ reasoning or resources), context (contingencies) and outcomes, often abbreviated to context-mechanism-outcome configuration (CMO) to show how particular contexts or conditions trigger or fire mechanisms to generate an observed outcome. (p. 3)

The realist approach does not provide a definitive answer about what works, but does provide detailed information about the contexts and mechanisms which explain how, for whom, and in what circumstances the interventions work (or not) (Pawson 2006).

An underlying assumption of a realist review is that all social interventions are based on a theory or theories about how to change behaviours (Pawson 2006, p. 74). Architects of interventions believe that if an intervention is delivered in a certain way it will produce particular results. The underlying theory(ies) is/are not always made explicit; however, a key task of a realist synthesis is to articulate the underlying theory or theories, and “interrogate the existing [empirical] evidence to find out whether and where these theories are pertinent and productive” (Pawson 2006, p. 74).

Within a realist synthesis, each study is examined for what it can add to the theoretical understanding of how and why interventions work (or not), and studies are included from varied sources including the grey literature (e.g., non peer-reviewed government reports). Consistency in methods and outcome measures across primary studies and evaluations is not a requirement (Jackson et al. 2009; O’Campo et al. 2009; Walshe and Luker 2010). Indeed, studies are often quite varied in terms of study design, length of implementation and follow-up, as well as specific outcomes.

The search process

As noted above, our original question focused on formal interventions seeking to maintain individuals on methadone and/or improve their physical, social and mental health. A Clinical Librarian (KN) assisted with the development of the search strategy to obtain articles on evaluations of these types of interventions. See Additional file 1 for our initial search strategy and terms.

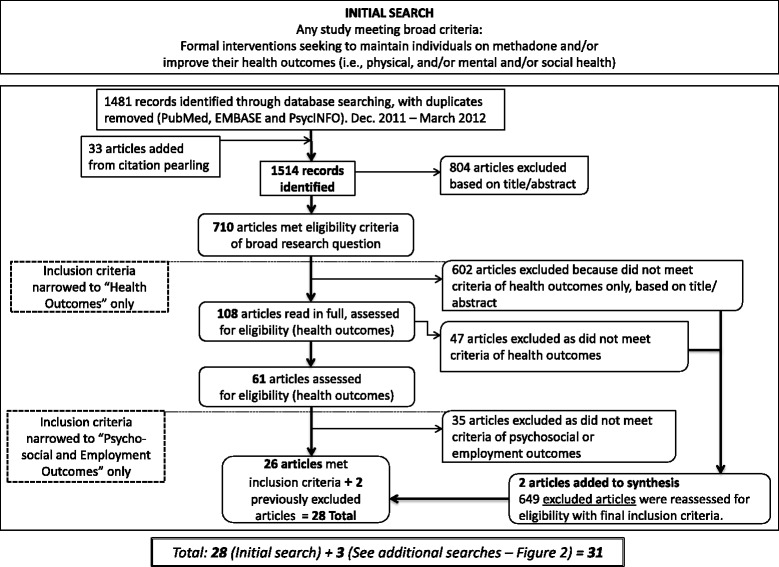

Based on our original search strategy (including searching reference lists of flagged articles or citation pearling), 1514 citations were found (Figure 1. Initial search process). Of these, 804 were deemed not applicable (according to the title and abstract), and 710 met our inclusion criteria based on our original research question. At this time, through discussions with the research team, there was consensus that the research question was too broad as it covered not only a vast literature on methadone retention, but also health outcomes for those on methadone. Therefore, the research question was narrowed to evaluations focused on health outcomes (defined in terms of physical, social or mental/emotional health), and articles centered on methadone retention were excluded because the research team prioritized health outcomes as of current importance in informing program and policy decisions. With the change in the research question, 108 articles met our new inclusion criteria of health outcomes (physical, social, mental/emotional health). These 108 articles were reviewed in more depth. Forty-seven articles were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria, and thus 61 articles remained.

Figure 1.

Initial search process.

As the 61 articles were reviewed there was consensus once again to limit the scope of the synthesis given the available time and resources. It was agreed that in order to do this we should focus on one or more specific health outcomes (e.g., physical, social and/or mental/emotional health). To facilitate this process the primary health outcome for each article was assessed, and the articles sorted according to the key health outcome. As we began to do this, however, it became clear that the articles did not fall clearly into the three categories of physical, social and/or mental/emotional health outcomes. There were some articles that reported on “overall health” so these were sorted into one group. Some articles focused on what we viewed as physical health outcomes (e.g., smoking cessation) and were placed into a second group. Other articles focused specifically on reducing high risk behaviors (e.g., reduced needle sharing) so were placed in a third grouping. A number of articles reported on psychosocial outcomes (e.g., improved self-esteem, involvement in non-drug using networks) so these were placed into a fourth grouping. Finally, a number of the articles centered on employment outcomes (e.g., hours of paid work) so these were placed into a fifth grouping.

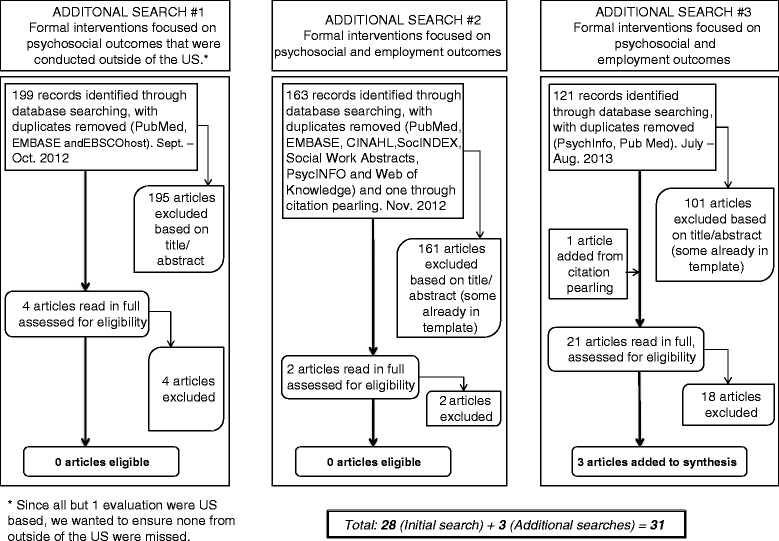

At this point in time, there was consensus that the synthesis would center on interventions where the key outcomes were psychosocial and/or employment outcomes. Articles with these two types of outcomes were chosen because of the importance of psychosocial health and employment to individuals’ quality of life. At this point in time, 26 of the 61 articles centered on psychosocial and/or employment outcomes. With this revised inclusion criteria some previously excluded articles were re-evaluated, and two were added to the synthesis, totaling 28. Additional searches were conducted to ensure we were capturing all relevant articles. Through these added searches, as well as citation pearling, three additional articles were found (Figure 2. Additional search process). Therefore, the total number of articles in our synthesis is 31. As the synthesis progressed we also sought literature to assist us in understanding our developing theory of why interventions for individuals on methadone appear to work or not.

Figure 2.

Additional search process.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included in the synthesis if they were quantitative and/or qualitative evaluations, peer reviewed, published from 1980–2011, and written in English. As Pawson and colleagues note (2005, p. S1:30), judgements concerning rigor are made based on whether the study can make “a methodologically credible contribution to the test of a particular intervention theory” and the 31 studies were deemed to contain sufficient data to contribute to testing the theory about why the interventions work (or not). Studies were excluded if: (a) they focused on family therapy or parenting outcomes or outcomes related to family members or others not on methadone treatment; (b) they included individuals on methadone as well as others not on methadone, but the outcomes for individuals on methadone were not clearly indicated; (c) there were no clear psychosocial and/or employment outcomes or the evaluation was mainly centered on drug use outcomes; and (d) the intervention was described as a methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) program with no clear indication of the component or components beyond methadone substitution that may have contributed to the psychosocial and/or employment outcomes.

Many of the articles specifically listed their outcomes as psychosocial or employment, but in some cases the outcomes were apparently psychosocial yet not explicitly stated as psychosocial. In these cases, we assessed the reported outcome(s) based on how psychosocial was defined in other articles (e.g., reduced depression, involvement with non-drug activities), as well as our assessment of the fit of the outcomes within this category. In cases where there was disagreement between the Research Co-ordinator (MMD) and Principal Investigator (LJ), at least two other members of the research team assessed the articles to determine the fit with the criteria. Some of the 31 interventions had objectives beyond improving psychosocial and/or employment outcomes, such as reduced drug use or retention in the program. These other outcomes are discussed only insofar as they are relevant to understanding the psychosocial and/or employment outcomes.

Data extraction

In consultation with the research team, four templates were created to extract and organize the data and assist with data analysis. The first template, (organizational template), numbered each article, and provided an overview of the article including the citation, objective of the study, summary of the intervention(s), study population and, overall results. The second template, (mechanisms template) was used to help capture data on what appeared to be the causal connectors (implicit or explicit) between the intervention and outcomes or what appeared to cause the intervention to work (or not work) (e.g., clients actively taking part in the activities). The third template, (context template), documented contextual factors (e.g., positive relationships between counselors and clients) that appear to be important to sparking the mechanism, and the fourth template (outcomes template) provided information on key outcomes of the intervention.

We developed the templates in terms of contexts, mechanisms and outcomes because within a realist review explaining behaviour patterns is done “by critically scrutinising the interaction between context, mechanism and outcome in a sample of primary studies” (Wong et al. 2010). Certain contexts may spark or elicit mechanisms, and thus generate “outcomes of interest” while others may not (Wong et al. 2012, p. 91). This means that, “An intervention itself does not directly change its participants; it is the participants’ reaction to the opportunities provided by the programme that triggers the change” (Wong et al. 2012, p. 92).

Reading the articles and developing the templates was an ongoing iterative process. As the Research Co-ordinator (MMD) and Principal Investigator (LJ) read the articles; the templates were revised following discussion and critical reflection with the research team. As our understanding of the articles developed we further refined the information in the templates. Through this process of constant comparison between the templates (often returning to the original articles to ensure that information in the templates had not been taken out of context), common themes or patterns were identified. The evolving patterns were discussed with all of the team members at a face-to-face workshop (November 2012). The themes were revised in light of the discussion, and after a re-examination of the templates as well as the original articles. Further refinement of the patterns in the data continued with the authors of the paper until agreement was reached. Following an assessment of the key patterns, two members of the research team (DL and LJ) reviewed once again the articles, and checked the fit of the patterns with the articles. We also attempted to identify disconfirming data or data that might challenge or refute our candidate theory. It is important to note that in this study a key focus is on the contextual factors that elicit or spark the mechanism that is linked to positive intervention outcomes. Contextual factors are the focus because one key over-riding mechanism was found to be linked to positive intervention outcomes.

Results

An overview of the interventions

An underlying assumption found in the 31 evaluations is that individuals on methadone treatment have a deficit or problem in how they think and/or behave that needs to be changed. There was great variability among the articles in terms of the specific problem(s) targeted for change, with some focusing on several different problems or issues. In some cases, the problem was not explicitly identified but was implicit in the evaluation. Overall, however, the interventions targeted a variety of cognitive/emotional problems (e.g., problem solving, self-esteem), and/or different behaviours (e.g., social involvement) (See Table 1 for some examples). In a number of instances, the goal was for the individual to achieve abstinence from drugs (other than methadone), or reduce drug use/alcohol use, in conjunction with other changes. At times, an underlying assumption was that continued drug use (e.g., cocaine use) interferes with the ability to improve psychosocial and/or employment outcomes.

Table 1.

Some examples of changes targeted by the various interventions

| Cognitive/emotional changes | Behavioural changes |

|---|---|

| • Problem solving skills (Abbott et al. 1998; Coviello et al. 2009; Platt et al. 1993) | • Communication and drug-refusal skills (Abbott et al. 1998) |

| • Understanding feelings and behaviors (Woody et al. 1995) | • Communication between clients and counselors (Joe et al. 1994; Dansereau et al. 1996) |

| • Self-awareness and discipline (Aszalos et al. 1999) | • Communication skills (Joe et al. 1997) |

| • Attention problems (Joe et al. 1994) | • Change in activities, such as avoiding drug-using friends (Farabee et al. 2002) |

| • Depression (Carpenter et al. 2006) | |

| • Greater understanding of self and issues related to women and drug use (implicit in evaluation) (Najavits et al. 2007) | • Developing and refining interpersonal skills (e.g. problem solving and communication skills) (Nurco et al. 1995) |

| • Communication and reasoning processes (Joe et al. 1997) | • Leadership skills (Glickman et al. 2006) |

| • Motivation to employment (Coviello et al. 2004) | • Job acquisition (Kidorf et al. 1998) |

| • Productive activity (Cohen et al. 1982) | |

| • Action steps to employment (Coviello et al. 2004) |

The majority of the interventions included individual/group counseling or therapy as a component of the intervention. However, various approaches were utilized (and varied combinations) such as cognitive behavioural therapy (Aszalos et al. 1999), supportive decision-making (Bigelow et al. 1980), and mapping or visually representing feelings and actions (Joe et al. 1994). A number of interventions had, in addition to a therapy or counseling component, other components such as an educational element, or referral to services (e.g., legal services).

Various outcome measures were used to assess changes (See Table 2 for some examples). Many of the evaluations reported positive outcomes, a few reported no improvement, and in some instances, there was a mix of outcomes often depending on the outcome measure or group (e.g., control group versus experimental group).

Table 2.

Some examples of outcome measures from the interventions

| Psychosocial outcomes | Employment outcomes |

|---|---|

| • Enrollment in health care coverage, improved living conditions (Aszalos et al. 1999) | • Employment status (mean hours employed per week) (Bigelow et al. 1980) |

| • Helping others (i.e., leadership) (Glickman et al. 2006) | • Days employed (Cohen et al. 1982) |

| • Drug avoidance activities (Farabee et al. 2002) | • Obtained employment (Magura et al. 2007) |

| • Reduced impulsive-addictive behaviour (Najavits et al. 2007) | • Perceived motivation to obtain a job (Coviello et al. 2004) |

| • Increased rapport self-confidence, and motivation (Dansereau et al. 1996) | • Behavioural actions to obtain a job (e.g., completing job applications) (Coviello et al. 2004) |

| • Productive activity (which included number of arrests) (Cohen et al. 1982) | • Job acquisition (having worked at least one day in the 30 days prior); mean monthly income (Coviello et al. 2009) |

| • Increased internal locus of control (Nurco et al. 1995) | • Number of vocational-educational services (e.g., pre- employment workshops) involved with (Appel et al. 2000) |

| • Improvement in psychiatric symptoms (Woody et al. 1987) | • Number of days employed in past 30 days (McLellan et al. 1993; Zanis et al. 2001) |

| • Counselor ratings of rapport, motivation and self-confidence (Joe et al. 1994) |

The evaluations also varied in terms of the groups targeted for the intervention or the inclusion and exclusion criteria. For example, some interventions targeted men only (McLellan et al. 1993), male veterans (Woody et al. 1987), or women only (Najavits et al. 2007). In one study, individuals were “ineligible if they were dependent on alcohol or benzodiazepines to the point of requiring medical withdrawal” (Farabee et al. 2002, p. 344) or eligible if dependent on alcohol (Cohen et al. 1982). There were also differences in how long clients had to have been on methadone to be eligible for the intervention. For example, individuals on methadone for at least 6 months (Nurco et al. 1995), or on methadone for a minimum of 90 days (Farabee et al. 2002).

In spite of the variability in the specific populations targeted, most interventions included individuals who were of low socio-economic status as indicated by education, low or under employment, housing status, and/or living on social security benefits (Coviello et al. 2009; Aszalos et al. 1999; Coviello et al. 2004; Farabee et al. 2002; Nurco et al. 1995; Ronel et al. 2011). In addition, many had been drug-involved for a number of years (Glickman et al. 2006; Nurco et al. 1995; Ronel et al. 2011). This suggests that the results of this synthesis apply mainly to populations of low socio-economic status with a significant history of drug use (i.e., individuals who have used drugs such as cocaine and heroin for a long period of time).

Candidate theory

In the early stages of the analysis a key pattern was evident in the data: attendance at the intervention (or what some articles refer to as retention or compliance) was associated with positive client outcomes, and conversely, lack of attendance was linked to poor outcomes. However, good attendance was also sometimes linked to disappointing outcomes suggesting that attendance alone does not lead to positive outcomes. Our candidate theory, therefore, was that attendance at interventions was important but not enough for positive outcomes. Lidz et al. (2004) argued, based on the evaluation of an intervention with disappointing outcomes, that in order to be successful, interventions need to, “engage patients, and command their attendance and active participation” (p. 2302). We began, therefore, to look at the literature on engagement, and more specifically literature focused on drug treatment and engagement. As we explored this literature we found that a number of researchers suggest that engagement is linked to positive outcomes. Fiorentine et al. (1999) argue that there is evidence that “client engagement in [drug] treatment is significantly associated with positive treatment outcomes” (p. 199). Likewise, Broome et al. (2007) maintain that, “the engagement or active participation of clients in [drug abuse] treatment is a critical step leading to better outcomes” (p. 149).

As we examined this literature in more depth, it became clear that there is no single definition of engagement (sometimes referred to as involvement), and it has been operationalized in different ways. As Broome et al. (2007) note, “Client engagement has been operationalized as session attendance or through a broader set of personal reactions, including building rapport or therapeutic alliance with a counselor, openness and participation within sessions, and perceived general helpfulness of or satisfaction within treatment” (p. 149). Speaking about clients’ engagement with therapy, Hill (2005) contends that, “client involvement refers to the degree of client engagement in the session, or the extent to which the client becomes immersed in the tasks required of the particular therapy” (p. 433). According to Hill, “client involvement might be inferred if the client initiates topics, explores the presenting problem, struggles to gain insight, participates in behavioral change activities, or openly informs the therapist about reactions or complaints” (2005, p. 433). Tetley et al. (2011) further argue that, “engagement refers to the extent to which the client actively participates in the treatment on offer” (p. 927). They maintain that:

To participate in therapy, clients must consistently attend the arranged therapy sessions and complete the specified course of treatment. In addition to this, clients must also be willing to share their inner world by disclosing their thoughts, feelings, problems, and history. Engaging in between-session tasks is also a requirement of clients in therapy. This includes thinking things over, trying out skills and doing homework. (Tetley et al. 2011, p. 928)

Key contexts within which interventions work (or not)

Based on this client engagement in drug treatment literature, and our initial review of the articles and templates, we hypothesized that engagement is the key mechanism through which change happens and that it involves both attendance at sessions as well as various personal reactions such as active participation in what is offered, openness to sharing thoughts, feelings, etc. We examined each template, and in turn the corresponding article, to determine the fit with this initial candidate theory. Through this process, we found that engagement appears to occur in some contexts and not in others. Specifically, we found three key contexts: (a) a client-centered context, and more specifically a context where clients are supported in articulating/addressing the psychosocial/employment needs/issues/skills that are important to them; (b) a context where the challenges of clients’ socio-economic lives are recognized and/or there are attempts to provide socio-economic assistance; and (c) a context in which there are quality/positive relationships between counselors and clients and/or among clients. Contexts (b) and (c) are frequently found together with context (a) or a client-centered context.

Our synthesis further found that ongoing engagement may, in some instances, be necessary for continued psychosocial and/or employment changes although the evidence for this is not strong. In addition, based on our analysis it appears that engagement can occur even when clients are not abstinent from drugs (e.g., there is some continued use of cocaine, heroin). However, it is unclear whether or not there is a ceiling over which drug use interferes with engagement, and/or if the type of drug might affect engagement.

We present below some key examples of the findings.

1) Intervention contexts that elicit and/or support engagement

a) Client-centered contexts

Intervention contexts where clients are supported in articulating/addressing the psychosocial/employment needs/issues/skills important to them, appear to elicit and/or support engagement. This process is often (although not always) linked to positive psychosocial and/or employment outcomes.

Client-centered contexts or those where clients are supported in articulating and/or addressing psychosocial/employment needs/issues/skills of value to them, appear to be important for engagement and thus positive outcomes (Additional file 2, see Contexts 1a). For example, one qualitative evaluation reported some positive results for an intervention that used a twelve-step program adapted to methadone clients in which clients were encouraged to articulate their issues in an accepting and supportive atmosphere where “members could feel comfortable and uninhibited to share their difficulties” (Ronel et al. 2011, p. 1142). The researchers argue that there were some positive changes because, “as the group progressed, there were meaningful social interactions between members during and in between meetings that possibly represented meaningful group processes” (Ronel et al. 2011, p. 1147). The researchers further argue that some “members who were formerly isolated established new friendships within the community of the group” (p. 1147). Nurco et al. (1995) likewise reported some positive results in their evaluation, and in this intervention the experimental group “demonstrated statistically significant changes in locus-of-control beliefs, from external to internal causation, about personal responsibility for drug misuse” (p. 765). The intervention was a clinically-guided self-help group (CGSH) that not only involved social and recreation activities (e.g., going to the movies) but discussions of “issues of self-declared importance” suggesting support for clients to articulate their issues (Nurco et al. 1995, p. 769).

Platt et al. (1993) reported positive outcomes for an employment intervention where participants were “helped in clarifying their own attractions and barriers to work”, and the barriers were used “as the basis for specifying individualized objectives and plans for action” (p. 23). The individualized approach points to a client-centered context, and the types of activities that supported clients in articulating their own employment barriers included exercises, group discussions, brainstorming, case studies as well as role playing. According to the researchers, “this study demonstrated a significant increase in employment” six months following the intervention, and jobs were not created or assigned to clients but rather, they had to “search out, apply for, and be hired for a position on their own” (Platt et al. 1993, p. 27).

A manual-based intervention targeting women which involved readings and exercises from a workbook, focused on “themes and psychoeducation relevant to women” pointing to a client-centered context (Najavits et al. 2007, p. 6). Not only was there a high attendance rate (87% of available sessions) but clients reported strong treatment satisfaction suggesting engagement with the intervention. According to the researchers, “Results indicated significant improvements from intake to 2 months later on key variables most related to treatment:…impulsive-addictive behaviour, global improvement and knowledge of the workbook concepts” (Najavits et al. 2007, p. 9). Other variables (e.g., employment, psychological problems) “despite being non-significant over time, were largely in the direction of improvement” (p. 8–9).

In an intervention evaluated by Coviello et al. (2009), the experimental group received treatment based on interpersonal cognitive problem solving (ICPS) focused on drug and employment counseling. The control group also received treatment based on ICPS but only focused on drug counseling. Both groups had improved employment outcomes and it appears that this was because in both groups there was support for clients to think through “his/her own problems and select a range of implementable options that could potentially be helpful in reaching a realistic goal” (Coviello et al. 2009, p. 190). Indeed, the authors argue that one of the reasons why there was no significant treatment effect between groups is likely because “both groups received the problem-solving intervention, [and] the control group could have generalized these strategies to finding work” (p. 195).

Node-link mapping which requires clients’ to map their issues through the drawing of a physical map (often in conjunction with the counselor), was evaluated in three articles (Joe et al. 1994; Joe et al. 1997; Dansereau et al. 1996). According to Dansereau et al. (1996), visual maps are used to “represent interrelationships comprising personal issues and related plans, alternatives or solutions visually” (p. 364). In two evaluations (Dansereau et al. 1996; Joe et al. 1994), clients in the mapping groups improved on psychosocial measures (i.e., counselors’ rating of clients on rapport, motivation and self-confidence). It appears that the improvement in the mapping groups was related, at least in part, to the support (through mapping) in helping clients to articulate their issues. The third evaluation reported mixed results depending on the outcome measure (Joe et al. 1997). The researchers suggest that the negative outcomes may be because the mapping allowed “clients to see their psychological and social strengths and weaknesses in a more critical (and perhaps more realistic) light” (Joe et al. 1997, Discussion para 3), and this suggests that in some cases, articulating one’s issues may be overwhelming and may lead to negative outcomes, at least for a period of time.

A number of studies that supported clients in developing needed skills also reported positive outcomes. For example, a mandatory employment program based on behavioural contingencies (e.g., more intensive counseling if clients did not meet the employment goals) was evaluated by Kidorf et al. (1998), and found that most clients (75%) secured employment and maintained the position for at least one month. In this intervention, the counselors helped clients with a number of employment-related issues (e.g., strategies for seeking employment) as well as help in “completing applications, creating resumes, and identifying job and volunteer openings,” indicating a client-centered context (Kidorf et al. 1998, p. 78). Zanis and Coviello (2001) evaluated an employment case management intervention involving 10 clients, and the intervention also appeared to support engagement through a client-centered approach of assisting with skill development. The researchers argue that the intervention was, “designed to motivate chronically unemployed persons to engage in work, assist in job placement, and provide post employment support through workforce integration, while maintaining progress in drug treatment” (Zanis and Coviello 2001, p. 67). Part of the intervention included teaching relevant life skills, such as “how to use public transportation, budget money, decide on a health insurance plan, how to request a day off from work, how to communicate with employers, etc.” (p. 69). According to the researchers, “Nine of the 10 clients were employed at the two-month follow-up assessment and six maintained employment at the eight-month follow-up. Moreover, three clients were able to successfully transition from welfare to competitive private sector employment” (p. 67).

Contexts that do not support psychosocial and/or employment needs/issues/skills of importance to clients do not appear to support engagement and are linked to no change or poor outcomes.

In a couple of evaluations there was little, if any, change reported. Although it was not always clear why this was the case, it appears that in some instances it was because the clients were not fully engaged with the intervention. Lack of engagement appears to have been because the intervention context did not support the clients in articulating/addressing a needed psychosocial and/or employment issue (Additional file 2, see Contexts 1a [Lack of]). In two evaluations (Rounsaville et al. 1983; Cohen et al. 1982), for example, there was little or no difference between the experimental and comparison groups in outcomes, and the researchers note that there was poor attendance in the interventions. Rounsaville et al. (1983) compared a short-term interpersonal psychotherapy treatment (IPT) consisting of weekly individual psychotherapy, to a low-contact treatment consisting of one brief meeting per month. Only 38% of the IPT group completed treatment and 54% completed the low-contact condition. The researchers maintain that, “The attrition data are striking given the difficulty in attracting subjects to the study” (Rounsaville et al. 1983, p. 634). According to the researchers, most who dropped out of the IPT group “remained in the methadone program, indicating that it was the former treatment [IPT] that they failed to become engaged with and not the latter [methadone program]” (p. 634). It may be that the clients were already receiving the therapy they needed through the methadone program, and asking them to engage in more psychotherapy was not what they wanted or felt they needed. Indeed, the researchers suggest that this was the case as they note that, “there was little in our findings that would suggest that individual weekly short-term IPT provided additional benefit when added to a methadone program that already provided weekly group psychotherapy” (p. 634). Cohen et al. (1982) also note that there was very low attendance among the treatment groups in the intervention they evaluated, but that there was “considerably less resistance in their participation” in the methadone program (p.360). This also suggests that the intervention (which was centered on treating alcoholism among those deemed “operative alcoholics”) may not have been what clients wanted or felt they needed. In addition, the seminars that were part of the intervention may not have allowed the clients to be actively involved in articulating their specific issues.

In another intervention the goal was to improve both psychosocial (e.g., overall personal and social adjustment) and employment (i.e., mean hours employed each week) outcomes, and although there was good attendance, there was “little average change in the treated group over the 6 months of their participation” (Bigelow et al. 1980, p. 432). The researchers note that, “counselors selected specific treatment goals, and designed and implemented treatment techniques” (Bigelow et al. 1980, p. 430). It appears, therefore, that the treatment goals may not have been those of importance to the clients. It should also be noted, however, that all participants, including the control group, received supportive counseling which may have been what all the participants wanted, and hence the high rates of participation but not a significant difference in outcomes between the groups. This supportive counseling “consisted of here-and-now based discussion of [a] client’s life situations, feelings, problems and alternatives, with counselors providing both suggestions and emotional support” suggesting that it was client-centered (p. 430).

Finally, Lidz et al. (2004) noted disappointing outcomes from the intervention they evaluated, and argue that this was in part because the manual-based format of the intervention could not address clients’ barriers to employment such as having to explain past criminal behaviours. The researchers point out that, “Some subjects faced such complex barriers to employment that contrary to the manuals, it was often not possible to suggest realistic solutions during group discussion” (Lidz et al. 2004, p. 2303). The goal of the intervention was to improve employment rates but it appears that the context did not provide the supports and services that clients needed. As the researchers note, “…individualizing efforts to meet training needs, and providing support during job-finding and early job-holding might improve program effectiveness” (p. 2288).

b) Responsiveness to clients’ socio-economic lives

Intervention contexts that recognize/address the socio-economic conditions and needs of clients, appear to support engagement, and in turn positive outcomes.

In a number of interventions that were client-centered, there was also an acknowledgement of, and/or an attempt to address, clients’ socio-economic conditions and needs (Additional file 2, see Contexts 1b). For example, in some client-centered interventions socio-economic assistance was provided such as help with transportation, flexibility with bringing children to the intervention, and information on preferred shelters and accessing emergency food stamps (Aszalos et al. 1999), or help with literacy issues (McLellan et al. 1993). Although such assistance was not part of all client-centered interventions, there is some evidence that attention to clients’ socio-economic conditions and needs augments the supportive context for engagement. For example, in an intervention evaluated by McLellan et al. (1993) both the Enhanced Services (which included counseling plus on-site medical/psychiatric, employment and family therapy) and the Standard Services (counseling only) resulted in psychosocial improvements. However, the Enhanced Services had the most improvements in psychosocial outcomes over all (including employment and psychiatric status). Improvement in psychological problems and family problems among the Standard Services group might be explained by what appears to be a client-centered context such as assistance with “various problems” (McLellan et al. 1993, p. 1955). At the same time, the more positive outcomes in the Enhanced Services group might be explained, at least in part, by the fact that not only were many services offered to help address clients’ psychosocial needs, but clients were also provided with an employment counselor who “conducted a series of workshops and group sessions designed to teach reading and prepare for a general equivalence diploma” thus helping to address their socio-economic lives (p. 1955).

Farabee et al. (2002) evaluated an intervention comparing both cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and contingency management (CM), and found some positive outcomes in terms of drug-use avoidance activities, although CBT had more positive outcomes. The researchers argue that, “subjects who had been exposed to CBT reported engaging in drug-use avoidance activities more frequently than did subjects assigned to either the CM or control conditions” (Farabee et al. 2002, p. 348). It appears that the CBT groups were client-centered as clients were encouraged to articulate how the “topic introduced” was relevant to them (p. 346). At the same time, however, there appears to have been some engagement among the CM group as there were some positive outcomes for this group. The engagement may be attributed, in part, to the fact that vouchers were provided which could be used for subsistence items. The researchers point out that, participants were “strongly encouraged to use the voucher earnings to engage in new prosocial, non-drug-related behaviour” (p. 346), yet many wanted to use their earnings for such subsistence items as food (restaurant/fast food certificates, grocery store vouchers), or clothes for themselves or their children.

Intervention contexts where clients’ socio-economic lives are not recognized do not appear to support engagement.

In a couple of interventions, clients’ socio-economic lives were not recognized, and it appears that there was limited engagement (Additional file 2, see Contexts 1b [Lack of]). For example, an intervention evaluated by Lidz et al. (2004) reported disappointing outcomes, and it appears that there was limited engagement with the intervention. As the researchers note, “In some cases, subjects lacked the literacy and everyday knowledge that the manuals assumed they would have. Other subjects lacked the self-presentation skills to keep up with the pace of the programs” (Lidz et al. 2004, p. 2302). In this intervention, video feedback techniques were used “with subjects who often were not accustomed to making presentations in formal group settings” (p. 2302). The researchers indicate that the video feedback techniques embarrassed some clients when they viewed their video performances, and this made it “difficult to maintain group progress” (p. 2302).

An evaluation by Coviello et al. (2004) provides an example of an employment intervention that was aimed at increasing “motivation and action step activities that lead to employment” (p. 2309), but overall there were no differences between the control group and the intervention group (p. 2310). Although the intervention appears to have been client-centered insofar as it focused on clients thinking through their problems and selecting action steps towards employment (and the control group consisted of a similar cognitively-based intervention aimed at drug use), the intervention was not successful. According to the researchers, this was in large part because the goal was for clients to obtain taxable employment which did not fit with the clients’ “lifestyle”. The researchers argue that participants obtained day jobs often “off the books” rather than taxable employment (Coviello et al. 2004, p. 2318–2319). These off the books jobs helped the clients meet their financial needs and meant that they did not have to fear losing medical assistance coverage for methadone treatment. In addition, “several men with children believed that a job with taxable benefits would result in their wage being garnished for back child support” (p. 2320). According to the researchers, “Rather than continue with the VPSS sessions [intervention] with the aim of obtaining taxable income, clients dropped out of the intervention because their immediate need for income was satisfied” (p. 2320).

c) Positive or supportive relationships between counselors and clients, and among clients

Positive or supportive relationships between counselors and clients, and among clients, appear to support engagement, and thus positive outcomes.

In a number of evaluations in which the intervention context was client-centered the researchers also reported positive or supportive counselor-client relationships (Additional file 2, see Context 1c). For example, in Zanis and Coviello’s (2001) case management employment study (which had a client-centered approach), it appears that there were positive relationships between clients and counselors. This is suggested by the fact that a number of clients indicated that they felt “case management staff cares” (Zanis and Coviello 2001, p. 71). One counselor was also reported as having worked with a local employer to restructure the job hours to meet a client’s methadone schedule, further suggestive of caring relationships between counselor and client.

Woody et al. (1983) found that for all three treatment groups in their evaluation there was improvement on various psychosocial measures. Although it is not clear why there was improvement for all groups it is possible that positive relationships between patients and counselors were a factor as the researchers argue “Observations during this study and in other therapy situations suggest to us that the benefits of therapy are a result of the therapists’ ability to form a relationship…” (Woody et al. 1983, p. 645).

In a few of the evaluations, the factors that appeared to help create positive or supportive relationships were discussed. In many instances, these factors were related to the counselors’ or therapists’ attitudes, skills, behaviors and/or experiential knowledge. Connett (1980), for example, argues that, “the closer social environmental identification and experiences of CGA [paraprofessional] counselors with this type of patient population may have been more of an influencing factor upon patient progress in the short run than had been anticipated” (Connett 1980, p. 589). Nurco et al. (1995) contend that the counselors in the intervention they evaluated were charismatic, committed to the success of the program, were aware of clients’ issues, and possessed core interpersonal skills, such as “empathy, respect, and genuineness” (p. 770). In another intervention evaluated by Magura et al. (2007), counselors went into the community and worked with the clients, and the researchers believe that this helped to “build the therapeutic alliance with patients on which counseling depends” (p. 815).

Kidorf et al. (1998) argue that time in the relationship is important for the development of a positive relationship, and they maintain that a mandatory employment program they evaluated was successful, in part, because there was already an established relationship between the clients and counselors. The researchers indicate that the MMT patients had been in the methadone program for one year before the mandatory employment program, and this provided “ample time for the program to foster the development of a positive therapeutic relationship” (Kidorf et al. 1998, p. 79). They contend that this therapeutic relationship was important to “the successful management of patient anger and apprehension associated with negative contingencies” (p. 79). That is, the positive relationship with counselors helped to mitigate the various levels of negative consequences (e.g., increased intensive counseling, a 21 day methadone tapering in preparation for discharge), that were linked to not meeting treatment goals (Kidorf et al. 1998).

There is also a small amount of evidence that positive relationships among clients helps support engagement. For example, Platt et al.’s (1993) evaluation of an employment intervention reported positive peer relationships. The researchers note that within this intervention “participants…help[ed] each other through structured exercises which provide[ed] important peer feedback and support” (Platt et al. 1993, p. 23–24). Likewise, in an intervention where a “fellowship” between clients was encouraged, clients helped one another with homework and connected with each other outside of formal meetings (Ronel et al. 2011). This may have supported engagement with the intervention.

For a summary of findings 1 (a), (b), and (c) see Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of findings 1 (a, b, and c)

| 1) Intervention contexts that elicit and/or support (or not) engagement | ||

|---|---|---|

| (a) Client-centered contexts | Examples of client-centered contexts are those where clients are: | Examples of contexts that are not client-centered (and do not support psychosocial and/or employment needs/issues skills) are those where: |

| • Supported to think through their own problems and select a range of options to help reach a realistic goal (Coviello et al. 2009). | • Clients are already receiving the therapy they need through the methadone program (Rounsaville et al. 1983). | |

| • Involved with social and recreation activities (e.g., going to the movies) and discussions of “issues of self-declared importance” (Nurco et al. 1995). | • Intervention is not what clients want or feel they need: it appears that seminars may not have allowed clients to articulate their own issues (Cohen et al. 1982). | |

| • Assisted (through group discussions, role playing etc.) in clarifying their attractions and barriers to work, and helped to create individualized objectives and plans for action to find work (Platt et al. 1993). | • Manual-based format does not address real barriers to employment (e.g., how to explain past criminal behaviours) so realistic solutions to the barriers are not addressed during group discussions (Lidz et al. 2004). | |

| • Involved with readings and exercises from a workbook that are focused on relevant “themes and psychoeducation” (Najavits et al. 2007). | • Counselors select specific treatment goals and design and implement treatment techniques (suggesting that treatment goals are not what clients want) (Bigelow et al. 1980). | |

| • Encouraged to articulate their issues in an accepting and supportive atmosphere (Ronel et al. 2011) | ||

| • Supported (through visual mapping) to articulate their issues (Joe et al. 1994; Dansereau et al. 1996) (although not going so far as to overwhelm with personal issues) (Joe et al. 1997). | ||

| • Provided assistance with needed skills development such as: | ||

| ➢ how to complete applications, creating resumes, and identifying job and volunteer openings (Kidorf et al. 1998). | ||

| ➢ how to use public transportation, budget money, request a day off from work, communicate with employers, etc. (Zanis and Coviello 2001). | ||

| (b) Responsiveness to clients’ socio-economic lives | Examples of contexts that recognize/address the socio-economic conditions and needs of clients are those that provide: | Examples of contexts where clients’ socio-economic lives are not recognized are those where: |

| • Socio-economic assistance (e.g., help with transportation etc.) (Aszalos et al. 1999). | • The literacy level or social skills of the clients are not recognized (e.g., video feedback techniques used that embarrassed some clients) (Lidz et al. 2004). | |

| • Help with literacy issues (McLellan et al. 1993). | ||

| • Vouchers for subsistence items (e.g., food, clothes) (Farabee et al. 2002). | • Employment that includes taxable income is the goal of the program but this type of employment can negatively impact clients (e.g., taxable income can mean losing coverage for methadone treatment) (Coviello et al. 2004). | |

| (c) Positive or supportive relationships between counselors and clients, and among clients | Examples of contexts that support positive relationships between counselors and clients are those where counselors: | Examples of contexts that support positive relationships among clients are those where clients: |

| • Are committed to the success of the intervention; and are aware of clients’ issues and express “empathy, respect and genuineness” towards clients (Nurco et al. 1995). | • Help each other through structured exercises which provide peer feedback and support (Platt et al. 1993). | |

| • Are engaged in mediation on behalf of clients (e.g., working with a local employer to restructure job hours to meet a client’s methadone schedule) (Zanis and Coviello 2001). | • Help one another with homework and connect with each other outside of formal meetings (Ronel et al. 2011). | |

| • Work with clients over a period of time and have an established relationship (Kidorf et al. 1998). | ||

| • Go into the community and work with clients (Magura et al. 2007). | ||

| • Can identify with clients (e.g., understand clients’ experiences) (Connett 1980). | ||

2) Ongoing engagement may be needed

Ongoing engagement with an intervention may be necessary (in some instances) for sustained positive outcomes.

Given that the studies we reviewed were based on short-term interventions with most outcome measures taken at the end of the intervention or shortly thereafter, we do not have evidence about long-term changes in attitudes and/or behavior. However, there are suggestions that engagement over some period of time may be necessary, in some instances, but not in others (Table 4). Woody et al. (1987), for example, found that improvements in employment and psychiatric status were maintained (and in some cases there was increased improvement) when clients were evaluated 12 months after the baseline for the intervention. (During months 7 and 12 of this study there were no intervention supports in place). However, research by Platt et al. (1993) found that even though the employment gains in their intervention were significant at 6 months post-intervention, at 12 months post-intervention “overall employment gains declined in the experimental group” (p. 21). Although it is unclear why the employment gains declined, the researchers suggest that it may be because of unstable jobs or “the distress which many methadone clients report when faced with work demands” (Platt et al. 1993, p. 28). The researchers argue that this points to the need for ongoing support through interventions (Platt et al. 1993).

Table 4.

Results #2 – Ongoing engagement may be needed (in some instances) to sustain positive changes

| Citation | Intervention summary (Qualitative/Quantitative) | Main psychosocial/employment outcomes | Ongoing engagement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Joe et al. 1997. | The intervention compared: 1) An Individual and group counseling group (utilizing node-link mapping); and, 2) a control group with standard counseling. (Quantitative) | According to the researchers, 12 months after the treatment ended the outcomes were mixed. The mapping group was less likely than those in standard counseling to report illegal activity, being jailed or arrested. Yet, “measures of self-esteem, decision-making confidence, and hostility showed mapping clients tended to rate themselves more poorly than standard clients….However, overall ratings at follow-up were moderately positive on all measures in both counseling modalities” (Discussion para 3). | 2) Ongoing engagement |

| As the follow-up occurred one year after treatment ended, it is possible that at least some of the poor ratings on self-esteem, decision-making confidence and hostility among the mapping group were due to the lack of engagement with the intervention. The researchers also suggest, however, (as per finding 1a in Additional file 2) that some of the poor outcomes may have been due to the fact that clients saw their “psychological and social strengths and weaknesses in a more critical light” (Discussion para 3). | |||

| Platt et al. 1993. | The intervention compared: 1) Group counseling (vocational cognitive problem-solving); and, 2) a control group with standard methadone treatment services provided by their clinic (e.g., methadone and weekly individual counseling). (Quantitative) | According to the researchers, “At six months post-intervention, the experimental group (N = 67) demonstrated a significant increase in employment rate (13.4% to 26.9%); no significant change occurred for controls (n = 63). At 12 months post-intervention, however, overall employment gains declined in the experimental group…” (p. 21). | 2) Ongoing engagement |

| Twelve months after the intervention ended there was a decline in employment gains for the experimental group, which, according to the researchers suggests “the need for [an] additional intervention in order to maintain employment gains” (p. 21). | |||

| Woody et al. 1987. | Three groups were compared: 1) A Supportive-expressive Therapy (SE) group; 2) A Cognitive-behavioral Therapy (CB) group; and, 3) A drug counseling group. Follow-up evaluation was done 6 months after treatment ended. (Quantitative) | Positive outcomes were maintained overtime. Follow up evaluation occurred 6 months after treatment ended, and the intervention ran for 6 months. Hence, at 12 months following the baseline, “all treatment groups [n = 3] showed improvements. However, the two psychotherapy groups showed more improvements than the drug counseling group over a wider range of outcome measures, with marked changes in the areas of employment, legal status, and psychiatric symptoms” (p. 595). | 2) Ongoing engagement (Not needed) |

| This evaluation suggests that changes in clients’ attitudes and behaviours can continue for a period of time even after the intervention ends. |

3) Engagement can occur without complete abstinence from drugs

Complete abstinence from drugs does not appear to be necessary for engagement in an intervention.

In a number of the studies, there were at least some positive psychosocial and/or employment outcomes even though there was not complete abstinence from drugs suggesting that engagement can occur even when there is some continued drug use (Table 5). For example, Abbott et al. (1999) report that, both groups that received additional counseling and other services (beyond methadone) “benefited from additional treatment and continued to improve through the 6 months of treatment” (p. 135) however, “cocaine use was not altered in either group by … treatment interventions” (p. 136). As we noted earlier, Coviello et al. (2009) report that for the intervention and control groups in their evaluation there were “significant improvements in the percent of subjects who were employed after the six-month intervention…[and] significant increase in mean monthly income from baseline to follow-up” (p.194). However, these researchers also note that, “There were no significant between-group differences in opiate use and no overall reduction in opiate use from baseline to six months….There were also no differences in use of cocaine or benzodiazepines, either between groups or from baseline to follow-up” (Coviello et al. 2009, p. 195). In a pilot intervention evaluated by Carpenter et al. (2006), 48% of the responders demonstrated a 50% reduction in baseline depression scores following the 16-week intervention yet the responders did not differ from non-responders in terms of cocaine and opioid use (p. 544–545).

Table 5.

Results #3 – Engagement can occur without complete abstinence from drugs

| Citation | Intervention summary (Qualitative/Quantitative) | Main psychosocial/employment outcomes | Engagement can occur without complete abstinence from drugs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abbott et al. 1999. | Two groups were compared: 1) A Methadone Free at Intake (MFI) group; and, 2: Methadone Maintenance Transfers (MMT) or those who were on methadone for a period of time. The goal of the study was to determine if enhanced services would benefit the groups. Both groups received two treatments: a) Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA) (problem-solving skills, drug-refusal training, communication skills etc.) with referrals to the Job Finding Club; and, b) Standard Counseling (SC) with referrals to “resources in the clinic or community” (p. 131). (Quanitative) | For both groups of clients (MMT and MFI) there were improvements in “drug, alcohol, legal, employment, social and in some measures of psychiatric distress” with the use of additional services and this continued up to the 6 month follow-up point (p. 129). At 6 months “the two groups [MMT and MFI] were comparable with regard to psychiatric problems”, legal problems and both showed decreases in depression (p. 135). | 3) Engagement can occur without complete abstinence from drugs |

| Both groups had some positive psychosocial and employment outcomes even with continuation of drug use. At 6 months both groups were approximately 75% opiate-free, however, according to the researchers, “cocaine use was not altered in either group by our treatment interventions” (p. 136). | |||

| Carpenter et al. 2006. | The intervention involved behavioral therapy and contingency management through individual counseling. No control or comparison group. (Quantitative) | According to the researchers, “Approximately 48.3% of the patients demonstrated at least a 50% reduction” in self-rated depression and clinic rated depression at 12 weeks relative to baseline (p. 544). They also report that, “Cocaine and opiate use…did not differ between the groups” (p. 545). | 3) Engagement can occur without complete abstinence from drugs |

| Responders to treatment demonstrated a 50% reduction in depression scores following the 16-week intervention. These responders did not, however, differ from non-responders in terms of cocaine and opiate use, suggesting that engagement can occur in an intervention even in a context of continued drug use. | |||

| Coviello et al. 2009. | Two groups were compared using a manual based interpersonal cognitive problem solving (ICPS) theory: 1) a control group using ICPS focusing on drug counselling; and, 2) an experimental group using ICPS with integrated employment and drug counselling. (Quantitative) | According to the researchers, “While there were no differences between the integrated and control conditions, both groups showed a significant improvement in employment outcomes…at the six-month follow-up” (p.189). | 3) Engagement can occur without complete abstinence from drugs |

| Both groups (the control and experimental) had significant improvements in outcomes yet there was some continued drug use in both groups. According to the researchers, “There were no significant between-group differences in opiate use and no overall reduction in opiate use from baseline to six months” (p. 195). The researchers also note that there were “no differences in use of cocaine or benzodiazepines, either between groups or from baseline to follow-up” (p. 195). | |||

| Kidorf et al. 1998. | This intervention involved a mandatory employment programme based on contingency management (i.e., more intensive counseling and eventually methadone tapering if did not meet employment goals). The intervention included counseling to help find employment (paid or volunteer). No control or comparison group. (Quantitative) | According to the researchers, “Seventy-five percent of the patients secured employment and maintained the position for at least 1 month. Positions were found in an average of 60 days. Most patients (78%) continued working throughout the 6-month follow-up” (p. 73). | 3) Engagement can occur without complete abstinence from drugs |

| Although patients who met the employment goal had lower proportions of cocaine and opioid-positive urines than those who did not met the goal, there was still drug use. This suggests engagement can occur when using drugs. The researchers do indicate that employment may have lowered the use of drugs. They note that, “We hoped that employment would operate as a powerful relapse-prevention strategy; the lower rates of drug use by those who found a job lends some support to this hypothesis” (p. 78). | |||

| McLellan et al. 1993. | Three groups were compared: 1) A Minimum Methadone Services (MMS) group which involved methadone only; 2) Standard Methadone Services group (counseling only) (SMS); and, 3) Enhanced Methadone Services (EMS) group which included counseling and extended on site medical/psychiatric, employment, and family therapy services. (Quantitative) | The SMS group had “significant decreases in illegal drug use…with some additional changes in alcohol, legal, family and psychiatric problem area status measures” (p. 1957). The EMS group had the most improvements in both drug use and psychosocial outcomes overall (including employment, criminal activity and psychiatric status). According to the researchers, “The EMS group showed better outcomes than did the SMS group on 14 of the 21 measures” within the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (p. 1957). | 3) Engagement can occur without complete abstinence from drugs |

| According to the researchers, although there was some reduction in drug use, it was not eliminated even when there were improvements in psychosocial and employment outcomes. For example, with respect to the EMS group the researchers note that this group “showed a 30% increase in number of days of employment a 57% decrease in cocaine use and 67% reductions in the number of days of alcohol use, opiate use, illegal activities and psychological problems” (p. 1957). | |||

| Woody et al. 1995. | Two groups were compared: 1) A Drug Counseling (DC) group; and, 2) A Supportive-expressive (SE) Psychotherapy group. Both groups received drug counseling which included referrals to medical, social and legal services when needed, along with “exploring current problems and providing support… and responding to acute personal or social crises” (p.1303). (Quantitative) | At one month follow up both groups had improved approximately the same. However, after 6 months the counseling group (DC) “had lost many of its gains or failed to improve further, while the group receiving supportive expressive psychotherapy showed continued improvement in several areas, to the point where both statistically and clinically significant differences became apparent” (p. 1307). The SE group improved in terms of employment and psychiatric symptoms. | 3) Engagement can occur without complete abstinence from drugs |

| According to the researchers, across all weeks, the SE group (which was the group which showed improvement in employment and psychiatric symptoms) averaged 22% cocaine-positive urines while the DC group averaged 36%. According to the researchers, “31% of the patients receiving supportive-expressive psychotherapy and 27% of the drug counseling patients had urine samples that were positive for at least one other drug (usually benzodiazepines) each week during the course of treatment” (1305). |

Limitations

Our synthesis has a number of limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, our initial search was based on our original research question, and we reviewed hundreds of citations for appropriate articles. Given that our original research question was very broad, relevant articles related to our final research question (which was much narrower) may not have been identified. However, we did try and address this limitation by undertaking additional searches focused specifically on psychosocial and/or employment outcomes.

A second limitation relates to our decision to focus on health outcomes. When we decided to have this focus we had to make a determination about the key health outcomes of the articles. In some instances the authors explicitly stated the outcomes as psychosocial, in other instances we had to categorize them as such. We may, therefore, have included articles that other researchers may have excluded, and conversely, excluded articles that others may have included. However, in order to ensure consistency in articles included, decisions about inclusion and exclusion of the articles were made by multiple members of the research team.

The four templates that were developed were of value in helping to organize and analyze the data, and as such were a key part of the data analysis process. However, it is important to note that through the process of extracting data from the articles and refining the information in the templates important pieces of information may have been missed from the analysis process or taken out of context. We did, however, return on a continual basis to the original articles in an attempt to address this limitation.

Another limitation of this review is that we were interested in articles that evaluated interventions for individuals on methadone treatment yet there were variations across studies in terms of methadone dosage, adherence, and so forth. This may have influenced the outcomes reported in the 31 studies. In addition, some studies lacked a control or comparison group, and therefore, in some instances it was difficult to know to what extent reported changes were due to the intervention. Moreover, in some cases there were multiple intervention components making it challenging to assess what specifically may have caused the change (or no change). As well, some of the studies had control and/or comparison groups receiving standard services, but sometimes there was limited information on what these received so it was difficult to determine why there may (or may not) have been changes among controls or comparison groups. A number of the articles also provided limited, if any, information about what the researchers believed created the changes (or not), and inferences had to be made based on relatively little information.

Finally, the 31 articles are not exhaustive given that we included only peer-reviewed, English articles written during a specific period of time. Including only peer-reviewed articles was due to the relatively large number of articles that were found, and the recognition that the articles do provide a “body of literature on which to test and refine theory” (Wong et al. 2011). This synthesis provides rich in-depth information about why interventions aimed at improving the psychosocial and/or employment outcomes of individuals on methadone appear to work (or not), but it is recognized that our findings could be further tested by searching for, and analyzing, grey literature.

Discussion

This realist review of 31 articles has four key findings. First, engagement with an intervention appears to be key to an intervention working to improve psychosocial and/or employment outcomes for individuals on methadone. The role of engagement is not new but some of the literature equates attendance at treatment with engagement. Our research indicates that engagement is more than attendance, and that it includes some type of personal reaction to what is offered so that there is an investment in the process. Nevertheless, further research is needed to more fully understand the notion of engagement. Specifically, research is needed that explores the engagement process when the intervention is aimed at different outcomes beyond psychosocial and employment outcomes. For example, what is the nature of engagement when involved with interventions seeking to improve educational outcomes? Is the process of engagement the same or different? Moreover, do clients’ backgrounds (e.g., number of different interventions that they have been involved with over a period of time) influence engagement?

The second key finding from our synthesis is that various intervention contexts are critical to eliciting and/or supporting this engagement process. The three intervention contexts that were found to be critical are: (a) those which are client-centered, or in other words where clients are supported in addressing psychosocial and employment issues that are important to them; (b) those which recognize and/or respond to clients’ socio-economic conditions and needs; and (c) those where there are positive counselor-client and/or peer client relationships. This review also suggests that ongoing engagement may, in some situations, be necessary for continued positive changes although the evidence for this finding is weak. Finally, a fourth key finding is that engagement can occur without complete abstinence from drugs (e.g., there may be continued use of cocaine, heroin). However, whether or not there is a ceiling over which continued drug use may interfere with engagement is not known, and further research related to this finding is needed.

The importance of a client-centered approach for individuals on methadone treatment has been raised by others (see, for example, Jamieson et al. 2002), and this realist review therefore re-affirms the importance of this perspective. However, this synthesis also highlights a variety of methods or strategies that can be utilized in developing and shaping a client-centered context. These methods or strategies include: manual-based interventions, exercises that encourage talking, node-link mapping, assistance with developing needed skills, support in accessing services including those required for day-to-day survival, etc. Although our synthesis re-affirms the importance of a client-centered approach it also indicates that, in some contexts, it may be overwhelming for clients when they are addressing some of their psychosocial issues, and this may negatively impact outcomes (see, Joe et al. 1997). Given the challenging lives that many within this population have experienced it is perhaps not surprising that articulating some personal issues may, at times, cause distress. It is unclear under what conditions this distress might occur but our synthesis does suggest that there is a need for great sensitivity when encouraging this engagement process in order to avoid such distress. Continuous feedback from clients to help gauge the intensity of the process may provide guidance on the steps that need to be taken to reduce any potential negative reactions.

Our realist review not only points to the importance of contexts which are attentive to what clients view as important psychosocial and/or employment needs/issues/skills, but also to contexts that recognize clients’ socio-economic lives, and to those which support and encourage positive relationships between clients and counselors and/or among clients. Further research is needed to understand the nature of the relationship between these three different contexts as it is not clear if one context alone can elicit and/or support engagement and/or if all three contexts might help to intensify the engagement process and potentially lead to better outcomes. However, our review does suggest that failure to recognize the socio-economic lives of clients may be a key factor in why clients are not engaged with some interventions. Indeed, in a couple of evaluations, researchers noted that failure to understand the socio-economic lives of those targeted for the intervention was a critical factor in explaining the disappointing outcomes (Coviello et al. 2004; Lidz et al. 2004).