Abstract

Intracellular ion channels are essential regulators of organellar and cellular function, yet the molecular identity and physiological role of many of these channels remains elusive. In particular, no ion channel has been characterized in melanosomes, organelles that produce and store the major mammalian pigment melanin. Defects in melanosome function cause albinism, characterized by vision and pigmentation deficits, impaired retinal development, and increased susceptibility to skin and eye cancers. The most common form of albinism is caused by mutations in oculocutaneous albinism II (OCA2), a melanosome-specific transmembrane protein with unknown function. Here we used direct patch-clamp of skin and eye melanosomes to identify a novel chloride-selective anion conductance mediated by OCA2 and required for melanin production. Expression of OCA2 increases organelle pH, suggesting that the chloride channel might regulate melanin synthesis by modulating melanosome pH. Thus, a melanosomal anion channel that requires OCA2 is essential for skin and eye pigmentation.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.04543.001

Research organism: human

eLife digest

Melanin is a pigment found in our skin, eyes and hair. Individuals who are unable to make or store melanin, a condition known as albinism, have unusually pale features and problems with vision. The pigment helps to protect us from harmful UV radiation, and so individuals with albinism also have an increased risk of developing skin and eye cancers.

In cells, melanin is made and stored in compartments called melanosomes. The most common type of albinism is caused by defects in a protein called OCA2, which is found in the membrane that surrounds melanosomes. However the role of OCA2 in melanin production is unclear.

It has been proposed that OCA2 may allow charged particles (or ions) to enter or leave melanosomes. Here, Bellono et al. used a technique called patch-clamp to study the movement of ions across the membrane of melanosomes from skin and eye cells. The experiments show that a flow of chloride ions out of the melanosome is required for melanin to be produced. OCA2 is involved in the ion movement, and it might alter the acidity of the melanosome when present.

Bellono et al. propose that OCA2 is part of an ion channel that allows chloride ions to pass through the membrane, to make the melanosome less acidic and enable melanin to be produced. The next challenge will be to identify other ion channels in the melanosome and understand their roles in producing melanin.

Introduction

Ion channels are membrane proteins that regulate the concentration of key signaling ions to control a wide range of cellular functions. While plasma membrane ion channels have been extensively studied, much less is known about the identity and physiology of intracellular channels because they are less accessible to direct electrophysiological characterization.

Melanosomes are lysosome-related organelles that produce and store melanin, a natural pigment present in most organisms. Impaired melanin synthesis and storage affects visual system development and pigmentation of the skin, eyes, and hair, leading to reduced protection against ultraviolet radiation and predisposition for skin and eye cancers. A number of genes encoding putative melanosomal ion transport proteins are critical for melanosomal function, as mutations in these genes result in oculocutaneous albinism (OCA) (Montoliu et al., 2014). This suggests that ionic homeostasis plays an important role in melanin synthesis and storage, yet how ion channels might contribute to melanosome function and pigmentation remains poorly understood (Bellono and Oancea, 2014).

One of the most common forms of albinism is caused by mutations in a highly conserved protein encoded by the oculocutaneous albinism II gene (OCA2) (Gardner et al., 1992; Rinchik et al., 1993; Rosemblat et al., 1994; Lee et al., 1994a; Sitaram et al., 2009) (Figure 1—figure supplement 1). OCA2-deficient animals lack pigment (Gardner et al., 1992; Protas et al., 2006) and reduced OCA2 expression leads to decreased melanin underlying blue eye color in humans (Eiberg et al., 2008; Sturm et al., 2008). OCA2 has twelve predicted transmembrane domains (Gardner et al., 1992), is localized to melanosomal membranes (Rosemblat et al., 1994; Sitaram et al., 2009), and has been implicated in pH regulation of melanosomes and trafficking of the melanogenic enzyme tyrosinase (Puri et al., 2000; Manga and Orlow, 2001; Chen et al., 2002, 2004; Ni-Komatsu and Orlow, 2006). Despite its importance, the function of OCA2 and the molecular mechanism by which it regulates melanin are not known.

Here we identify and characterize a new intracellular ion channel that resides in the melanosomal membrane and requires OCA2 expression. Using whole-organelle and single-channel patch-clamp recordings we found that OCA2 contributes to an anion channel required for pigmentation. The OCA2-mediated Cl− current was nearly abolished by a mutation identified in patients with oculocutaneous albinism type II. Interestingly, expression of OCA2 in endolysosomes increased organelle pH, providing a potential mechanism for how OCA2 regulates melanogenesis. Thus, a previously uncharacterized OCA2-dependent anion channel is critical for melanosomal function and pigmentation, revealing a novel function for intracellular ion channels.

Results and discussion

Because intracellular ion channels are important regulators of organellar and cellular function and defects in melanosomes, lysosomal-related organelles present in melanocytes and retina, often result in severe pigmentation phenotypes, we wondered how ion channels contribute to melanosome function. We investigated OCA2, a melanosome-specific membrane protein of unknown function that, when mutated, results in albinism.

OCA2 expression in endolysosomes leads to a Cl− conductance (IOCA2)

In melanocytes and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) OCA2 is restricted to melanosomes, but when expressed in heterologous systems it localizes to lysosomes and late endosomes (endolysosomes) (Sitaram et al., 2009). To investigate if OCA2 has ion transport activity, we expressed OCA2 tagged with GFP (GFP-OCA2) or mCherry (mCherry-OCA2) in AD293 cells, where it colocalized with the endolysosomal marker LAMP1 (Figure 1A). Endolysosomes are an ideal melanosome-related heterologous system because they can be enlarged by treating cells with 1 μM vacuolin-1 and mechanically released from the cytoplasm with a glass pipette (Cerny et al., 2004; Saito et al., 2007; Dong et al., 2008). We recorded whole-organelle currents from endolysosomes expressing GFP-OCA2 and found that voltage pulses evoked a large outwardly rectifying current (IOCA2) that was not present in mock-transfected cells (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. OCA2 contributes to an endolysosomal chloride current with ion channel properties.

(A) Heterologous GFP-OCA2 localized to LAMP1-mCherry-positive late endosomes and lysosomes (endolysosomes) individually dissected from AD293 cells for patch-clamp experiments (scale bar = 5 μm). Whole-endolysosomal currents elicited by voltage steps between −80 mV and +80 mV in a representative endolysosome expressing GFP-OCA2 or in an endolysosome from a mock-transfected cell. (B) Representative whole-endolysosome current–voltage (I–V) relationships in response to voltage ramps. Outwardly rectifying IOCA2 was nearly abolished and its reversal potential (Erev) shifted in the positive direction when luminal Cl− was substituted for gluconate (Gluc−), similar to currents measured from mock-transfected endolysosomes containing a Cl−-based luminal solution. (C) Average current densities (pA/pF) measured at 100 mV. Inset: Average Erev (±s.e.m., n = 6–9 endolysosomes for each condition). (D) In a representative OCA2-expressing endolysosome, Erev was dependent on cytoplasmic [Cl−] ([Cl−]cyto). NMDG-based solutions were used to inhibit endogenous cation permeabilities. (E) IOCA2 Erev varied linearly with [Cl−]cyto when [Cl−]luminal was kept at 48 mM. Each point represents one endolysosome at the [Cl−]cyto indicated on the x-axis.

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. OCA2 is a highly conserved transmembrane protein expressed in pigment cells.

Figure 1—figure supplement 2. IOCA2 is not mediated by K+ flux or regulated by pH.

Figure 1—figure supplement 3. IOCA2 is mediated by Cl− flux.

Figure 1—figure supplement 4. Cl− channel blockers DIDS, NFA, and NPPB do not affect IOCA2.

The measured outward current could result either from K+, the main cation in the bath, moving into the endolysosome, or Cl−, the main anion in the pipette solution, moving out of the endolysosome. We tested if IOCA2 carries K+ into the lumen by replacing it with Na+ in the bath solution. We detected no significant change in the current amplitude or reversal potential (Erev) (Figure 1—figure supplement 2A,B), suggesting that K+ is not required for IOCA2. We next tested if IOCA2 is mediated by luminal Cl− moving into the cytoplasm by replacing Cl− in the pipette solution with the impermeant anion gluconate (Gluc−). IOCA2 was nearly abolished with Gluc− in the pipette and Erev was significantly shifted in the positive direction, consistent with the endogenous current recorded in endolysosomes from mock-transfected cells (Figure 1B,C). The similar current amplitude and positive Erev measured in mock-transfected and OCA2-expressing endolysosomes with luminal Gluc− suggests the presence of an endogenous cationic permeability. When we subtracted this endogenous current from IOCA2, the Erev for IOCA2 became similar to ECl predicted by the Nernst equation (Figure 1—figure supplement 3). The significant reduction in current amplitude in the presence of luminal Gluc− indicates that IOCA2 is mediated by Cl−, consistent with OCA2 homology to bacterial anion transporters (Rinchik et al., 1993; Brilliant, 2001; Kobayashi et al., 2006). We tested whether a range of pharmacological inhibitors of different Cl− channels and transporters affect IOCA2 by bath-applying 4,4′-diisothiocyanato-2,2′-stilbenedisulfonic acid disodium salt (DIDS), niflumic acid (NFA), or 5-Nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)benzoic acid (NPPB), but none significantly altered IOCA2 amplitude (Figure 1—figure supplement 4). Thus, IOCA2 has a different pharmacological profile from the channels and transporters that are inhibited by the tested compounds.

The Nernst equation predicts that if IOCA2 were due to selective transport of Cl−, Erev will be dependent on the Cl− concentration ([Cl−]) gradient across the endolysosomal membrane. To establish whether this is the case, we determined Erev for currents measured at variable cytoplasmic and constant luminal [Cl−], using NMDG-based solutions to prevent endogenous cationic permeability. Erev for 48 mM luminal and 8 mM cytoplasmic [Cl−] was −42.7 ± 2.3 mV and shifted to 1.6 ± 2.5 mV under symmetrical 48 mM [Cl−] (Figure 1D). Erev increased linearly as a function of cytosolic [Cl−] ([Cl−]cyto), with a 10-fold change in [Cl−]cyto corresponding to a shift in Erev of 58 mV, consistent with a highly Cl− selective current (Figure 1E).

Mutations associated with oculocutaneous albinism disorder affect IOCA2

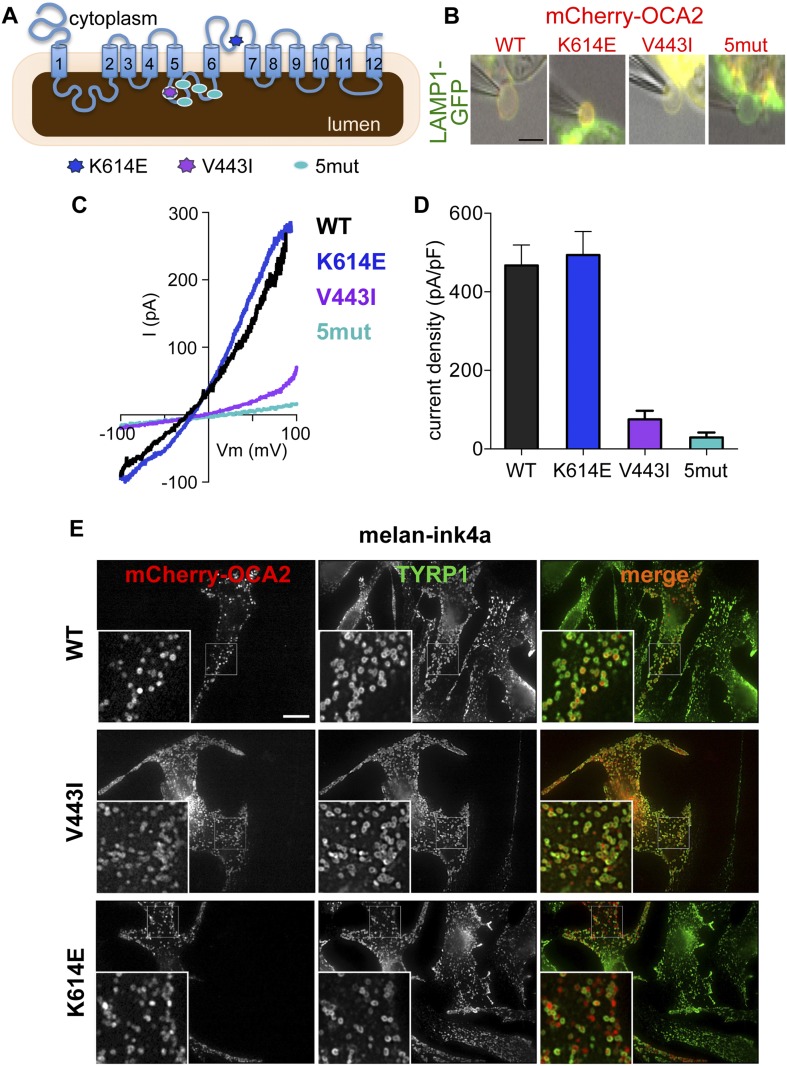

OCA2 shares little homology with known chloride channels or transporters; OCA2 might be an accessory subunit of a Cl− transporter or form a Cl− channel or carrier protein itself. To determine if specific OCA2 residues are required for Cl− transport, we sought to identify mutations important for ion transport, but not melanosomal localization. We analyzed mCherry-OCA2 variants containing disease-related mutations within highly conserved regions of the protein (Figure 1—figure supplement 1A). We chose mutations identified in patients with OCA type II through human genetic studies: V443I, a common albinism-associated mutation in a predicted luminal loop and important for melanin content in vitro (Lee et al., 1994a, 1994b; Sviderskaya et al., 1997; King et al., 2003; Garrison et al., 2004; Hongyi et al., 2007; Preising et al., 2007; Hutton and Spritz, 2008; Rimoldi et al., 2014) and K614E, in a predicted cytoplasmic loop (Passmore et al., 1999). We also generated an OCA2 variant with five point mutations in the same predicted luminal loop as V443I (5mut: V443I, M446V, I473S, N476D, N489D) (Lee et al., 1994a, 1994b; Spritz et al., 1995; Hongyi et al., 2007; Preising et al., 2007) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Effect of OCA2 disease-associated mutations on IOCA2.

(A) Predicted topology of OCA2 with albinism-associated mutations: K614E (dark blue) in a conserved cytoplasmic loop, V443I (purple) in a highly conserved luminal loop, and 5mut (light blue) consisting of 5 point mutations (V443I, M446V, I473S, N476D, N489D) in the same luminal loop. (B) mCherry-tagged WT, K614E, and V443I OCA2 localized to LAMP1-GFP-positive isolated endolysosomes (merged in yellow), while 5mut did not (scale bar = 5 μm). (C) Representative I–V relationships measured in response to voltage ramps from endolysosomes expressing WT, K614E, V443I, or from endolysosomes isolated from cells expressing 5mut OCA2. (D) Average IOCA2 current densities (pA/pF) measured at 100 mV (±s.e.m., n = 4–8 endolysosomes for each condition). (E) Melan-ink4a melanocytes expressing mCherry-tagged (red) WT, V443I, or K614E and stained with anti-tyrosinase-related protein one (TYRP1) antibodies (green). Insets, 3× magnification of boxed regions. Merged images (right) show that WT, V443I, and K614E OCA2 variants localize primarily to TYRP1-positive compartments (scale bar = 10 μm).

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. Localization of wild-type (WT), K614E, V443I, and 5mut OCA2.

Upon expression in HeLa cells, the K614E and V443I mutants colocalized with the endolysosomal marker LAMP1, similar to WT mCherry-OCA2 (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A), indicating that both mutants traffic efficiently to endolysosomes when expressed in non-melanocytic cells. By contrast, 5mut OCA2 localized primarily to endoplasmic reticulum-like structures rather than endolysosomes (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A), therefore it could be used as a negative control. In pigment cells containing melanosomes (melan-ink4a), expression of OCA2 variants revealed that WT, as well as V443I and K614E mutants colocalized with the melanosomal tyrosinase-related protein 1 (TYRP1; overlap with TYRP1 = 60.1 ± 21.3% for WT; 50.7 ± 13.9% for V433I; and 53.6 ± 16.1% for K614E mCherry-OCA2) (Figure 2E), whereas overlap with the endolysosomal marker LAMP2 was minimal (11.8 ± 10.7% among all variants). A portion of K614E localized to vesicular structures without TYRP1 but that contained pigment when imaged by bright field microscopy.

To determine if albinism-associated mutations affect IOCA2, we expressed mCherry-tagged WT, K614E, V443I or 5mut OCA2 in AD293 cells together with LAMP1-GFP (Figure 2B). Currents recorded from AD293 endolysosomes identified by LAMP1-GFP and expressing K614E had similar amplitudes and Erev as WT OCA2 (Figure 2C,D), but those expressing V443I had amplitudes reduced by ∼85% and Erev shifted to more positive values (Figure 2C,D). Endolysosomes of cells expressing 5mut had very small current amplitudes and a positive Erev, similar to mock-transfected cells (Figure 2C,D).

Collectively, these data suggest that the V443I-containing luminal loop between transmembrane domains 5 and 6 is critical for the OCA2-mediated Cl− current. The K614E mutation had little effect on localization or OCA2-mediated currents in our experiments. Because K614E was identified in albinism patients with an additional OCA2 mutation (Passmore et al., 1999), its associated phenotype might be too mild to detect in our assays or might be masked by overexpression.

OCA2 regulates organelle pH

How does the OCA2-mediated anion conductance affect pigmentation? Early stage melanosomes are highly acidic (Raposo et al., 2001), but because tyrosinase is inactive at pH < 6.0, melanosomal pH is thought to increase in order to allow for melanin synthesis (Ancans et al., 2001; Halaban et al., 2002). We tested the hypothesis that OCA2-mediated anion extrusion from melanosomes regulates luminal pH (Puri et al., 2000; Brilliant, 2001; Manga and Orlow, 2001; Chen et al., 2002, 2004; Ni-Komatsu and Orlow, 2006), similar to other anionic conductances (Stauber and Jentsch, 2013). We expressed in endolysosomes of AD293 cells ecliptic pHluorin-LAMP1, which becomes fluorescent at pH > 6 (Rak et al., 2011) (Figure 3A). Endolysosomes of control cells were acidic and lacked fluorescence emission at baseline (Figure 3B), but exhibited increased fluorescence upon neutralization (pH > 6) of organellar pH by cellular treatment with the vacuolar H+-ATPase inhibitor bafilomycin A1 (BafA1) (Figure 3A–C). In contrast, coexpression of WT OCA2 with pHluorin-LAMP1 resulted in endolysosomes that were fluorescent at baseline, with only a small increase in fluorescence in response to BafA1 (Figure 3B,C). This indicates that OCA2 expression increased the pH of endolysosomes to > 6.

Figure 3. OCA2 expression regulates organellar pH.

(A) Ecliptic pHluorin-LAMP1 fluoresces when luminal pH > 6, but not when pH < 6. The V-ATPase inhibitor bafilomycin A1 (BafA1, 2 μM) was used to neutralize acidic endolysosomes and detect pHluorin-LAMP1 expression. (B) Endolysosomes from mock-transfected control (CTL) AD293 cells expressing pHluorin-LAMP1 were not fluorescent at baseline (Fo) but brightly fluoresced after BafA1 treatment (FBafA1). Endolysosomes coexpressing pHluorin-LAMP1 and mCherry-tagged WT or K614E OCA2 were fluorescent prior to BafA1 treatment (Fo), indicating that expression increased pH. Endolysosomes that coexpressed pHluorin-LAMP1 and V443I were dim at baseline (Fo), similar to CTL and mislocalized 5mut, representing an acidic lumen, and pHluorin-LAMP1 fluorescence increased upon BafA1 treatment (FBafA1) (scale bar = 10 µm). (C) Fluorescence intensity following BafA1 treatment was compared with baseline fluorescence to determine relative baseline acidity in enodolysosomes from CTL cells, expressing WT, K614E, V443I, OCA2 or from cells expressing mislocalized 5mut. Bars represent average normalized change in pHluorin-LAMP1 fluorescence (±s.e.m., n = 3 independent experiments, each experiment calculated as the average of n = 78–214 endolysosomes).

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. LysoSensor pH measurements.

To determine if changes in pH required the OCA2-mediated anion conductance, we examined changes in pHluorin-LAMP1 fluorescence elicited by the expression of albinism-associated OCA2 mutants. Endolysosomes expressing K614E exhibited basal fluorescence and little change in fluorescence following treatment with BafA1 (Figure 3B,C), consistent with its intact conductance and localization to endolysosomes (Figure 2, Figure 3—figure supplement 1). However, endolysosomes expressing V443I, which have significantly reduced current amplitudes but intact localization (Figure 2, Figure 3—figure supplement 1), had dim fluorescence at baseline that increased dramatically following BafA1 treatment (Figure 3B,C). Endolysosomes from cells expressing mislocalized 5mut lacked basal fluorescence and increased their fluorescence with BafA1 treatment (Figure 3B,C), similar to untransfected cells. Together, these results support the notion that OCA2-mediated ion transport in organelles modulates luminal pH.

We confirmed the observed OCA2-associated changes in luminal pH using the ratiometric pH-sensitive dye LysoSensor DND-160. Based on LysoSensor calibration, the luminal pH of LAMP1-positive compartments in control cells had an approximate pH value of 5.12 ± 0.03, while the luminal pH of WT OCA2-expressing endolysosomes was significantly greater (6.67 ± 0.03, Figure 3—figure supplement 1A–C). Expression of the K614E mutant increased pH to 6.32 ± 0.03, while V443I only modestly raised the luminal pH of endolysosomes to 5.72 ± 0.04, (Figure 3—figure supplement 1B). Melanosomal pH measurements were not possible because fluorescent indicator uptake in melanosomes is impaired and melanin interferes with the emission of fluorescent proteins.

Our pH measurements are consistent for the two indicators and show that OCA2-mediated Cl− transport shifts the endolysosomal pH toward neutral values that in melanosomes would be optimal for tyrosinase activity and melanin synthesis. The mechanism by which OCA2 modulates pH is unclear. We hypothesize that OCA2-mediated Cl− efflux from the lumen regulates the organelle membrane potential, reducing vacuolar H+-ATPase activity and resulting in less H+ being pumped in the lumen. Alternatively, the pH modulation by the OCA2-mediated Cl− conductance could be a more complex mechanism involving the contribution of additional channels and transporters. Thus, our model for pH regulation by OCA2 remains tentative and awaits a better understanding of melanosomal membrane conductance and signaling.

OCA2 contributes to a melanosomal chloride conductance (Imelano) required for pigmentation

To investigate endogenous OCA2, we measured native currents by direct patch-clamp recordings from melanosomes. This is technically challenging due to the intracellular localization and small size (300–500 nm) of melanosomes and because treatment of melanocytes with vacuolin-1 did not significantly enlarge melanosomes. To circumvent these difficulties we exploited a dermal melanocyte cell line derived from mice deficient in ocular albinism 1 (Oa1) (Palmisano et al., 2008), in which melanosomes are enlarged to up to ∼1 μm diameter (Cortese et al., 2005). Recordings from individual melanosomes dissected from Oa1−/− melanocytes under the same conditions used for endolysosome patch-clamp experiments (Figure 4A) revealed a large outwardly rectifying current (Imelano) with a negative Erev that was dependent on luminal Cl−, similar to currents recorded from OCA2-expressing endolysosomes (Figure 4B,C). When currents recorded in the presence of luminal Gluc− were subtracted from Imelano measured in the presence of Cl−, Erev was similar to ECl (Figure 4—figure supplement 1A). The Erev for Imelano measured with NMDG-based solutions was found to be −44.3 ± 2.5 mV for 48 mM luminal and 8 mM cytoplasmic [Cl−] and −2.3 ± 1.1 mV for symmetrical 48 mM [Cl−] (Figure 4—figure supplement 1B,C), consistent with the values measured for endolysosomes expressing OCA2 (Figure 1E) and with the Nernst potential for Cl− selective currents.

Figure 4. Direct recording from melanosomes identifies an endogenous Cl− current (Imelano).

(A) Dermal macromelanosomes were individually dissected from Oa1−/− melanocytes and patch-clamped. A NaCl-based luminal solution and KGluc-based cytoplasmic solution were used for recordings (scale bar = 10 μm). (B) Representative I–V relationships exhibit a Cl−-dependent outwardly rectifying current (Imelano) with a negative Erev. Substituting luminal Cl− for Gluc− reduced the current amplitude and shifted Erev of Imelano. (C) Average current densities (pA/pF) measured at 100 mV. Inset: Average Erev (±s.e.m., n = 4–5 dermal melanosomes for each condition). (D) Patch-clamp experiments using freshly isolated bullfrog RPE melanosomes (scale = 10 μm). (E) Representative whole-RPE melanosome current–voltage (I–V) relationships in response to voltage ramps. Outwardly rectifying Imelano was reduced and Erev shifted in the positive direction when luminal Cl− was substituted for Gluc−. (F) Average current densities (pA/pF) measured at 100 mV. Inset: Average Erev (±s.e.m., n = 5 RPE melanosomes for each condition).

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. Imelano Erev is dependent on the Cl− concentration gradient.

Figure 4—figure supplement 2. RPE melanosome dissection.

In addition to skin melanocytes, melanosomes are also present in the retinal pigment epithelium of the eye. We patch-clamped melanosomes dissected from freshly isolated RPE cells from American bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus) that are larger than those from mammalian RPE, thus allowing for patch-clamp experiments (Figure 4E, Figure 4—figure supplement 2). RPE whole-melanosome recordings identified an outwardly rectifying current with a negative Erev that was nearly abolished (reduced by ∼90%) by substituting luminal Cl− with Gluc− (Figure 4E,F). Together, these data indicate that a current with similar properties as IOCA2 is present in melanosomes from skin and RPE.

To determine if OCA2 contributes to Imelano, we used OCA2-targeted siRNA to reduce OCA2 expression (Figure 5—figure supplement 1A). Consistent with previous findings (Sviderskaya et al., 1997), reducing endogenous OCA2 expression markedly decreased melanin content in Oa1−/− melanocytes (Figure 5A, Figure 5—figure supplement 1B). Melanosomes dissected from melanocytes expressing OCA2-targeted siRNA had dramatically reduced current amplitudes and melanin content compared with melanosomes from cells expressing scrambled siRNA (control), indicating that OCA2 is required for Imelano and pigmentation (Figure 5B,C). Expression of WT OCA2, but not of the V443I mutant, in siRNA-treated cells was sufficient to reconstitute Imelano and rescue melanization (Figure 5A–C), suggesting that the OCA2-mediated current is required for melanin production.

Figure 5. OCA2 is required for Imelano and pigmentation.

(A) Representative images of Oa1−/− melanocytes expressing scrambled or OCA2-targeted siRNA, the latter of which significantly decreased melanin content. Pigmentation was restored by transfection with mCherry-tagged WT OCA2, but not with the mCherry-tagged V443I mutant (scale bar = 10 μm). (B) Representative I–V relationships from melanosomes from cells expressing scrambled siRNA, OCA2-targeted siRNA, and rescued with WT or V443I OCA2. Insets: images of the individual melanosomes used for the shown recordings (scale bar = 3 μm). (C) Average Imelano current densities (pA/pF) measured at 100 mV in melanosomes from cells expressing scrambled siRNA or OCA2-targeted siRNA (±s.e.m., n = 4 melanosomes per condition). (D) Average current densities (pA/pF) measured at 100 mV in melanosomes expressing WT or V443I OCA2 from cells expressing OCA2-targeted siRNA (±s.e.m., n = 3–4 melanosomes per condition).

Figure 5—figure supplement 1. OCA2-targeted siRNA reduces OCA2 mRNA and melanin content in Oa1−/− melanocytes.

Figure 5—figure supplement 2. Melanin is not required for Imelano.

Might melanin itself be critical for Imelano? To address this question, we treated Oa1−/− melanocytes with phenylthiourea (PTU), a potent inhibitor of the key melanogenic enzyme tyrosinase, resulting in melanin depletion (Figure 5—figure supplement 2A). Recording from melanosomes dissected from PTU-treated melanocytes revealed a current with the same properties as in vehicle-treated cells and similar to Imelano, suggesting that melanin does not influence Imelano (Figure 5—figure supplement 2B,C). We thus concluded that OCA2 expression is required for Imelano and melanization, but melanin is not required for Imelano.

We next sought to compare the biophysical properties of the endogenous OCA2-mediated melanosome current (Imelano) in dermal and RPE melanosomes with those of the OCA2-expressing endolysosome current (IOCA2). Excised cytoplasmic-side-out patches from partially dissected endolysosomes of OCA2-expressing AD293 cells (Figure 6A) exhibited single-channel currents (iOCA2) with greatest activity at positive membrane potentials (Figure 6B), consistent with the outward rectification measured for whole-endolysosome IOCA2 (Figure 1B). Patches from mock-transfected endolysosomes did not exhibit similar single-channel activity (Figure 6—figure supplement 1A,B). The Erev of iOCA2 was −66 mV, close to ECl predicted by the Nernst equation (−68 mV), and the unitary slope conductance was 58 ± 2 pS (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. Endolyosomal IOCA2 has the same properties as melanosomal Imelano.

(A) Cytoplasmic-side-out patches were excised from partially dissected organelles to carry out single-channel recordings. (B) Representative single-channel currents recorded in response to voltage steps between −80 mV and +80 mV from a patch excised from an OCA2-expressing endolysosome (O indicates the open state and C the closed state of the channel). (C) Average single-channel current amplitudes from patches excised from OCA2-expressing endolysosomes (±s.e.m., n = 4 patches) (ECl = Nernst potential for Cl−). (D) Single-channel currents from a representative patch excised from a dermal melanosome that contains at least two channels (O1 indicates one open channel, O2 indicates two channels open simultaneously, and C both channels closed). (E) Average single-channel current amplitudes from patches excised from dermal melanosomes (±s.e.m., n = 3 patches). (F) In a representative OCA2-expressing endolysosome, dermal melanosome, and RPE melanosome, currents were selective for Cl− and Br−, but not I−, F−, or Gluc−. In the same organelle, currents were recorded with 48 mM luminal NMDG-Cl while substituting symmetrical concentrations of cytoplasmic anions in an NMDG-based solution. (G) IOCA2 permeability ratios based on Erev measurements (±s.e.m., n = 3–7 organelles for each condition).

Figure 6—figure supplement 1. OCA2-mediated single-channel current characteristics.

Ion channels are pore-proteins that allow rapid diffusion of ions (>106 ions/s) down their concentration gradients, while carriers and pumps typically move ions at slower rates (<105 ions/s). We thus calculated the OCA2-mediated transport rate at 80 mV, where we measured the largest single-channel amplitude, and found a transport rate of ∼5.5 × 107 ions/s. The large conductance recorded in isolated patches from OCA2-expressing endolysosomes indicates that OCA2 functions as a critical component of an electrodiffusive anion channel. Similar properties were measured for single-channel currents in excised cytoplasmic-side-out patches of dermal melanosomes from Oa1−/− melanocytes (imelano) (Erev = −67 mV and unitary slope conductance = 60 ± 1 pS) (Figure 6D,E). Thus, the single-channel properties of this endogenous melanosomal current are nearly identical to those recorded from OCA2-expressing endolysosomes.

To determine the anion selectivity of the recorded currents, we estimated the permeability to different anions by determining Erev under symmetrical concentrations (48 mM) of luminal Cl− and cytoplasmic Cl−, Br−, I−, F− or Gluc−. Erev for IOCA2 was close to zero for cytoplasmic Cl− and Br− and shifted to negative voltages for I−, F−, and Gluc− (Figure 6F), suggesting that in endolysosomes OCA2 mediates a current selective for Cl− and Br−, but poorly permeable to I−, F−, and Gluc−. A similar shift in Erev was measured for Imelano in dermal or RPE melanosomes (Figure 6F), indicating that the endogenous currents have the same selectivity profile. Moreover, the calculated permeability ratios (Px/PCl) for the heterologously expressed currents were nearly the same as the endogenous ones (Figure 6G). Collectively, these results suggest that IOCA2 and Imelano are mediated by the same anion channel.

Conclusions and implications

Our results suggest that OCA2 is an essential component of a melanosome-specific anion channel. Heterologous endolysosomal expression of OCA2 contributes to a chloride channel with biophysical properties similar to an endogenous melanosomal OCA2-mediated channel. Importantly, OCA2 activity controls the melanin content of melanosomes, most likely by regulating organellar pH. We propose that OCA2 contributes to a novel melanosome-specific anion current that modulates melanosomal pH for optimal tyrosinase activity required for melanogenesis.

Materials and methods

Cells and tissue

All cells were grown at 37°C and 5% CO2, and reagents were from Invitrogen/Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY) unless stated otherwise. AD293, HeLa, and NF-SV60 fibroblasts were grown in DMEM, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Atlanta Biologicals, Flowery Branch, GA) with or without 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S).

Immortalized mouse melanocyte cell lines melan-Ink4a (Sviderskaya et al., 2002) and melan-Oa1 (Palmisano et al., 2008) were grown in RPMI 1640, 10% FBS, 1% P/S, 200 nM phorbol 12-myristate-13-acetate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 37°C and 10% CO2. Primary human epidermal melanocytes and keratinocytes were isolated from neonatal foreskin. Human epidermal melanocytes (Cascade Biologics/Life Technologies) were cultured in Medium 254, Human Melanocytes Growth Supplement, and 1% P/S. Human epidermal keratinocytes (Lifeline Cell Technology, Frederick, MD) were cultured in Dermalife basal medium supplemented with LifeFactors and 1% P/S.

Transfection of cells used for electrophysiology and imaging was carried out using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen/Life Technologies) according to manufacturer's protocol, unless otherwise stated.

RPE tissue

American Bullfrogs (L. catesbeianus) eyes were hemisected and RPE tissue was removed from the eyes with forceps after removal of the retinas. The dissection was performed in normal room light using light-adapted frogs. The tissue was kept at 4°C in a modified Ringer's solution containing (mM): 111 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1.5 MgCl2, 0.02 EDTA, 3 HEPES, pH 7.6. Tissue was used for a maximum of 36 hr.

Molecular biology

OCA2 tagged with GFP or mCherry was generated by inserting human OCA2 (hOCA2, NM_000275) between the BamHI/Xhol sites of pcDNA4/TO (Invitrogen/Life Technologies). K614E and V443I mutations in hOCA2 were made using site-directed mutagenesis and verified by sequencing. 5mut hOCA2 was generated by Genscript (Piscataway, NJ).

siRNA

Mouse OCA2 (mOCA2)-targeted and scrambled siRNAs were designed and expressed using the BLOCK-iT miRNA lentiviral system (Invitrogen/Life Technologies). mOCA2 specific oligos were cloned into pcDNA6.2-GW/EmGFP-miRNA, then recombined into pLenti6/V5-DEST vector and expressed in Oa1−/− mouse melanocytes using viral transduction (Bellono et al., 2013). Stable cell lines of OCA2-targetd or control siRNA-expressing melanocytes were created using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and subsequently kept under blasticidin selection (10 μg/ml). For rescue experiments hOCA2 was transfected in mouse melanocytes expressing mOCA2-targeted siRNA.

Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Plus kit (QIAGEN) and reverse transcribed using SuperScript III kit (Invitrogen/Life Sciences). mOCA2 mRNA levels were determined using the following primers: F 5′-CAGGAATCGCAGAGAAGCAT-3′ and R 5′-AGATAGCACATCCCAATGGTG-3′. hOCA2 mRNA levels in an array of human tissues (Origene) and in human epidermal skin cells were determined by qPCR with the following primers F 5′-GTGTGCAGGGATTGCAGAAC-3′ and R 5′-ACATCCCAACAGTGCAGGAC-3′. Reactions were prepared according to manufacturer instructions using Power SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems/Life Technologies) and cycled on a 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems/Life Technologies). Actin was used as an internal control and all reactions were run in triplicate. mRNA levels were quantified by calculating 2−ΔCT values for each condition.

Organellar electrophysiology

Organelle dissection

AD293 cells were transiently transfected 1 day prior to electrophysiological recordings and treated with 1 μM vacuolin-1 (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) for 6–12 hr before the patch clamp experiments. Enlarged endolysosomes were individually dissected for patch clamp experiments, as previously described (Dong et al., 2008). In short, a borosilicate patch pipette was used to cut the cell membrane and push out individual organelles. Enlarged dermal melanosomes were dissected from Oa1−/− mouse melanocytes and RPE melanosomes from bullfrog RPE cells using two patch pipettes.

Recording conditions

Organelle patch-clamp recordings were carried out at room temperature using an EPC 10 amplifier (HEKA Instruments, Lambrecht, Germany) with PatchMaster software (HEKA Instruments). Data were filtered at 2.9 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz. Membrane potentials were corrected for liquid junction potentials. Organelle currents were recorded using borosilicate glass pipettes polished to 7–8 MΩ for lysosomes and 9–12 MΩ for melanosomes. Standard pipette/lumen solutions contained (mM): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 MES, 10 glucose; pH 4.6 for endolysosomes and pH 6.8 for melanosomes, unless otherwise stated. Standard bath/cytoplasmic solution contained (mM): 140 K-gluconate, 5 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 0.39 CaCl2, 1 EGTA (Ca2+ buffered to 100 nM), 20 HEPES, pH 7.2. NMDG-based solutions were used in some experiments to block endogenous cation permeabilities. The holding potential was 0 mV and currents were measured in response to 500 ms voltage ramps from −100 to +100 mV, unless otherwise stated. Whole-organelle current density was calculated by normalizing to capacitance (0.14–0.5 pF for melanosomes, 0.24–1.2 pF for endolyosomes). Single-channel current amplitudes were measured from the middle of the noise band between closed and open states or calculated from the difference between Gaussian-fitted closed and open peaks on all-points amplitude histograms for each excised patch record. To determine if IOCA2 passes Cl− electrodiffusively, reversal potential (Erev) was measured using 48 mM luminal Cl− and variable cytoplasmic [Cl−] and compared with Erev predicted by the Nernst potential for Cl−: ECl = (RT/zF)ln([Clluminal]/[Clcytoplasmic]). R = gas constant, z = valence (−1 for Cl−), T = absolute temperature, and F = Faraday constant.

Anion permeability

Relative permeability of IOCA2 was determined by measuring the shift in Erev after the substitution of bath/cytoplasmic anions from Cl− to Br−, I−, F−, or Gluc−. Pipette/luminal and bath/cytoplasmic solutions were 48 mM NMDG-X solutions, where X = Cl− for pipette/luminal and X = Cl−, Br−, I−, F−, or Gluc− for bath/cytoplasmic. Permeability ratios were estimated using the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz (GHK) equation: PX/PCl = exp (ΔErevF/RT), where ΔErev is the difference between Erev in symmetrical Cl (Erev = 0 mV) and that in cytoplasmic X. We did not correct for the possibility of the permeation of symmetrical NMDG+ or H+.

pH imaging

pHluorin-LAMP1

AD293 cells were cotransfected with mCherry-OCA2 and pHluorin-LAMP1 1 day prior to imaging experiments. pHluorin-LAMP1 expression was verified by treatment with bafilomycin A1 (BafA1, 2 μM). pHluorin-LAMP1 fluorescence intensity was quantified in endoysosomes that coexpressed mCherry-OCA2 and pHluorin-LAMP1 by subtracting the initial fluorescence from fluorescence elicited by treatment with BafA1: [(FBafA1 − Fo)/Fo]−1.

LysoSensor DND-160

AD293 cells were transfected 1 day prior to imaging experiments with mCherry-OCA2 or LAMP1 to identify endolysosomes, and incubated with 1 μM LysoSensor-ND160 for 5 min. Lysosensor was excited at 405 nm and its emission detected at 417–483 nm (W1) and 490–530 nm (W2). The ratio of emissions (W1/W2) in endolysosomes expressing mCherry-tagged OCA2 or LAMP1 was assigned to a pH value based on a calibration curve generated prior to each experiment using solutions containing 125 mM KCl, 25 mM NaCl, 24 μM Monensin, and varying concentrations of MES to adjust the pH to 3.5, 4.5, 5, 5.5, 6.5, 7, 7.5. The fluorescence ratio was linear for pH 5.0–7.0.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Melan-ink4a melanocytes were seeded on coverslips coated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) at 3–4 × 104 cells/well in a 24-well plate, transfected the next day with 0.8 μg of plasmid DNA; HeLa cells were seeded on glass coverslips at 105 cells/well in a six well plate, transfected the next day using GeneJuice (EMD Millipore) as recommended by the manufacturer, with 0.1 µg of plasmid DNA. Both cell types were analyzed 48 hr post-transfection. Cells were fixed in HBSS (Invitrogen)/2% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) for 20 min at roo temperature, washed once with PBS and labeled with primary and secondary antibodies diluted in PBS with 0.2% (wt/vol) saponin, 0.1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin, 0.02% (wt/vol) sodium azide as described (Calvo et al., 1999). Nuclei were labeled with 500 ng/µl Hoescht 33342 (Sigma). Antibodies used were: mouse anti-TYRP1 (TA99/mel-5, ATCC); mouse anti-human LAMP1 (H4A3) and rat anti-mouse LAMP2 (GL2A7; both from Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA). Donkey antibodies specific to mouse or rat immunoglobulin and conjugated to Dylight 594 or 488 were from Jackson Immunoresearch (West Grove, PA). Cells were imaged using a 100× HCX PL APO Lens on a Leica DM IRBE microscope equipped with a Retiga Exi Fast 1394 digital camera (Qimaging, Surrey, Canada) and Improvision Openlab software (Perkin–Elmer, Waltham, MA). Sequential z-stack images separated by 0.2 µm were acquired and deconvolved using the OpenLab Volume Deconvolution module. Images from single stacks are shown. Final images were generated and insets magnified using Photoshop (Adobe, San Jose, CA). Colocalization analyses were performed using OpenLab software, as described (Setty et al., 2007). Briefly, images of individual cropped cells were rendered binary using the ‘Density slice’ module and the densely labeled perinuclear region was excluded from analysis. Pixel overlap between binary red and green images in the remaining cell regions was defined using the ‘Boolean operations’ module and further analyzed using Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

Melanin quantification

Melanin from Oa1−/− melanocytes expressing scrambled or OCA2-targeted siRNA was quantified as previously described (Oancea et al., 2009). Briefly, the soluble and insoluble fractions of melanocytes were separated after cell lysis with 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma) in PBS pH 7.4. Total protein was measured in the soluble fraction using a Bradford Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Waltham, MA). The insoluble fraction was dissolved in 1 N NaOH by incubation for 30 min at 80°C and used to quantify melanin by measuring the optical density of each sample at 405 nm, then fit with a standard curve generated using synthetic melanin (Sigma). Average cellular melanin values were quantified as the ratio between total melanin and total protein from the same dish.

Data analysis

All data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. Data were considered significant if p < 0.05 using unpaired two-tailed Student t test or one-way ANOVA.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs C Cang and D Ren, who were instrumental for assisting us with the endolysosomal patch-clamp technique, V Yorgan and Dr SB Lizarraga for help with pH measurements and analyses, Dr TJ Roberts and D Sleboda for help with frogs, and Dr AL Zimmerman for advice and suggestions. We are also thankful to Dr JS Orange for providing the pHluorin-LAMP1 construct. We thank Drs AL Zimmerman, JA Kauer, and D Ren for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by NIAMS (R01 AR066318 to EO and R01 AR048155 to MSM), NEI (R01 EY015625 to MSM), Brown University (EO), NIGMS training grant T32 GM077995 (NWB), a NSF Graduate Research Fellowship (NWB), and NIGMS training grant T32 GM007229 (AJL).

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Funding Information

This paper was supported by the following grants:

National Science Foundation to Nicholas W Bellono.

National Institute of General Medical Sciences to Ariel J Lefkovith, Nicholas W Bellono.

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases to Michael S Marks.

National Eye Institute to Michael S Marks.

Brown University to Elena Oancea.

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Author contributions

NWB, Conception and design, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

IEE, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

AJL, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

MSM, Conception and design, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

EO, Conception and design, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

Ethics

Animal experimentation: All mouse melanocytes were obtained from the Wellcome Trust Functional Genomics Cell Bank as described in the Methods. American bullfrog eyes were obtained as discarded tissue from Dr Thomas Roberts' laboratory at Brown University (protocol number 1303990009) and used in agreement with all the ethics rules and regulations.

References

- Ancans J, Tobin DJ, Hoogduijn MJ, Smit NP, Wakamatsu K, Thody AJ. Melanosomal pH controls rate of melanogenesis, eumelanin/phaeomelanin ratio and melanosome maturation in melanocytes and melanoma cells. Experimental Cell Research. 2001;268:26–35. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellono NW, Kammel LG, Zimmerman AL, Oancea E. UV light phototransduction activates transient receptor potential A1 ion channels in human melanocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA. 2013;110:2383–2388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215555110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellono NW, Oancea EV. Ion transport in pigmentation. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2014;563C:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2014.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brilliant MH. The mouse p (pink-eyed dilution) and human P genes, oculocutaneous albinism type 2 (OCA2), and melanosomal pH. Pigment Cell Research. 2001;14:86–93. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0749.2001.140203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo PA, Frank DW, Bieler BM, Berson JF, Marks MS. A cytoplasmic sequence in human tyrosinase defines a second class of di-leucine-based sorting signals for late endosomal and lysosomal delivery. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:12780–12789. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerny J, Feng Y, Yu A, Miyake K, Borgonovo B, Klumperman J, Meldolesi J, Mcneil PL, Kirchhausen T. The small chemical vacuolin-1 inhibits Ca(2+)-dependent lysosomal exocytosis but not cell resealing. EMBO Reports. 2004;5:883–888. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Manga P, Orlow SJ. Pink-eyed dilution protein controls the processing of tyrosinase. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2002;13:1953–1964. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-02-0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Minwalla L, Ni L, Orlow SJ. Correction of defective early tyrosinase processing by bafilomycin A1 and monensin in pink-eyed dilution melanocytes. Pigment Cell Research. 2004;17:36–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0749.2003.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortese K, Giordano F, Surace EM, Venturi C, Ballabio A, Tacchetti C, Marigo V. The ocular albinism type 1 (OA1) gene controls melanosome maturation and size. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2005;46:4358–4364. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong XP, Cheng X, Mills E, Delling M, Wang F, Kurz T, Xu H. The type IV mucolipidosis-associated protein TRPML1 is an endolysosomal iron release channel. Nature. 2008;455:992–996. doi: 10.1038/nature07311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiberg H, Troelsen J, Nielsen M, Mikkelsen A, Mengel-From J, Kjaer KW, Hansen L. Blue eye color in humans may be caused by a perfectly associated founder mutation in a regulatory element located within the HERC2 gene inhibiting OCA2 expression. Human Genetics. 2008;123:177–187. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0460-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner JM, Nakatsu Y, Gondo Y, Lee S, Lyon MF, King RA, Brilliant MH. The mouse pink-eyed dilution gene: association with human Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes. Science. 1992;257:1121–1124. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5073.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison NA, Yi Z, Cohen-Barak O, Huizing M, Hartnell LM, Gahl WA, Brilliant MH. P gene mutations in patients with oculocutaneous albinism and findings suggestive of Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2004;41:e86. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.014902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halaban R, Patton RS, Cheng E, Svedine S, Trombetta ES, Wahl ML, Ariyan S, Hebert DN. Abnormal acidification of melanoma cells induces tyrosinase retention in the early secretory pathway. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:14821–14828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111497200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hongyi L, Haiyun W, Hui Z, Qing W, Honglei D, Shu M, Weiying J. Prenatal diagnosis of oculocutaneous albinism type II and novel mutations in two Chinese families. Prenatal Diagnosis. 2007;27:502–506. doi: 10.1002/pd.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton SM, Spritz RA. A comprehensive genetic study of autosomal recessive ocular albinism in Caucasian patients. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2008;49:868–872. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King RA, Willaert RK, Schmidt RM, Pietsch J, Savage S, Brott MJ, Fryer JP, Summers CG, Oetting WS. MC1R mutations modify the classic phenotype of oculocutaneous albinism type 2 (OCA2) American Journal of Human Genetics. 2003;73:638–645. doi: 10.1086/377569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M, Katoh H, Ikeuchi M. Mutations in a putative chloride efflux transporter gene suppress the chloride requirement of photosystem II in the cytochrome c550-deficient mutant. Plant & Cell Physiology. 2006;47:799–804. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcj052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ST, Nicholls RD, Bundey S, Laxova R, Musarella M, Spritz RA. Mutations of the P gene in oculocutaneous albinism, ocular albinism, and Prader-Willi syndrome plus albinism. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1994a;330:529–534. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199402243300803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ST, Nicholls RD, Schnur RE, Guida LC, Lukuo J, Spinner NB, Zackai EH, Spritz RA. Diverse mutations of the P gene among African-Americans with type II (tyrosinase-positive) oculocutaneous albinism (OCA2) Human Molecular Genetics. 1994b;3:2047–2051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manga P, Orlow SJ. Inverse correlation between pink-eyed dilution protein expression and induction of melanogenesis by bafilomycin A1. Pigment Cell Research. 2001;14:362–367. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0749.2001.140508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoliu L, Grønskov K, Wei AH, Martínez-García M, Fernández A, Arveiler B, Morice-Picard F, Riazuddin S, Suzuki T, Ahmed ZM, Rosenberg T, Li W. Increasing the complexity: new genes and new types of albinism. Pigment Cell & Melanoma Research. 2014;27:11–18. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni-Komatsu L, Orlow SJ. Heterologous expression of tyrosinase recapitulates the misprocessing and mistrafficking in oculocutaneous albinism type 2: effects of altering intracellular pH and pink-eyed dilution gene expression. Experimental Eye Research. 2006;82:519–528. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oancea E, Vriens J, Brauchi S, Jun J, Splawski I, Clapham DE. TRPM1 forms ion channels associated with melanin content in melanocytes. Science Signaling. 2009;2:ra21. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmisano I, Bagnato P, Palmigiano A, Innamorati G, Rotondo G, Altimare D, Venturi C, Sviderskaya EV, Piccirillo R, Coppola M, Marigo V, Incerti B, Ballabio A, Surace EM, Tacchetti C, Bennett DC, Schiaffino MV. The ocular albinism type 1 protein, an intracellular G protein-coupled receptor, regulates melanosome transport in pigment cells. Human Molecular Genetics. 2008;17:3487–3501. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passmore LA, Kaesmann-Kellner B, Weber BH. Novel and recurrent mutations in the tyrosinase gene and the P gene in the German albino population. Human Genetics. 1999;105:200–210. doi: 10.1007/s004390051090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preising MN, Forster H, Tan H, Lorenz B, de Jong PT, Plomp AS. Mutation analysis in a family with oculocutaneous albinism manifesting in the same generation of three branches. Molecular Vision. 2007;13:1851–1855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protas ME, Hersey C, Kochanek D, Zhou Y, Wilkens H, Jeffery WR, Zon LI, Borowsky R, Tabin CJ. Genetic analysis of cavefish reveals molecular convergence in the evolution of albinism. Nature Genetics. 2006;38:107–111. doi: 10.1038/ng1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri N, Gardner JM, Brilliant MH. Aberrant pH of melanosomes in pink-eyed dilution (p) mutant melanocytes. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2000;115:607–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rak GD, Mace EM, Banerjee PP, Svitkina T, Orange JS. Natural killer cell lytic granule secretion occurs through a pervasive actin network at the immune synapse. PLOS Biology. 2011;9:e1001151. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raposo G, Tenza D, Murphy DM, Berson JF, Marks MS. Distinct protein sorting and localization to premelanosomes, melanosomes, and lysosomes in pigmented melanocytic cells. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2001;152:809–824. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.4.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimoldi V, Straniero L, Asselta R, Mauri L, Manfredini E, Penco S, Gesu GP, Del Longo A, Piozzi E, Soldà G, Primignani P. Functional characterization of two novel splicing mutations in the OCA2 gene associated with oculocutaneous albinism type II. Gene. 2014;537:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.11.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinchik EM, Bultman SJ, Horsthemke B, Lee ST, Strunk KM, Spritz RA, Avidano KM, Jong MT, Nicholls RD. A gene for the mouse pink-eyed dilution locus and for human type II oculocutaneous albinism. Nature. 1993;361:72–76. doi: 10.1038/361072a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosemblat S, Durham-Pierre D, Gardner JM, Nakatsu Y, Brilliant MH, Orlow SJ. Identification of a melanosomal membrane protein encoded by the pink-eyed dilution (type II oculocutaneous albinism) gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA. 1994;91:12071–12075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M, Hanson PI, Schlesinger P. Luminal chloride-dependent activation of endosome calcium channels: patch clamp study of enlarged endosomes. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:27327–27333. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702557200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setty SR, Tenza D, Truschel ST, Chou E, Sviderskaya EV, Theos AC, Lamoreux ML, Di Pietro SM, Starcevic M, Bennett DC, Dell'angelica EC, Raposo G, Marks MS. BLOC-1 is required for cargo-specific sorting from vacuolar early endosomes toward lysosome-related organelles. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2007;18:768–780. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-12-1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitaram A, Piccirillo R, Palmisano I, Harper DC, Dell'Angelica EC, Schiaffino MV, Marks MS. Localization to mature melanosomes by virtue of cytoplasmic dileucine motifs is required for human OCA2 function. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2009;20:1464–1477. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-07-0710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spritz RA, Fukai K, Holmes SA, Luande J. Frequent intragenic deletion of the P gene in Tanzanian patients with type II oculocutaneous albinism (OCA2) American Journal of Human Genetics. 1995;56:1320–1323. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauber T, Jentsch TJ. Chloride in vesicular trafficking and function. Annual Review of Physiology. 2013;75:453–477. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm RA, Duffy DL, Zhao ZZ, Leite FP, Stark MS, Hayward NK, Martin NG, Montgomery GW. A single SNP in an evolutionary conserved region within intron 86 of the HERC2 gene determines human blue-brown eye color. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2008;82:424–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sviderskaya EV, Bennett DC, HO L, Bailin T, Lee ST, Spritz RA. Complementation of hypopigmentation in p-mutant (pink-eyed dilution) mouse melanocytes by normal human P cDNA, and defective complementation by OCA2 mutant sequences. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 1997;108:30–34. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12285621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sviderskaya EV, Hill SP, Evans-Whipp TJ, Chin L, Orlow SJ, Easty DJ, Cheong SC, Beach D, DePinho RA, Bennett DC. p16(Ink4a) in melanocyte senescence and differentiation. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2002;94:446–454. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.6.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]