Abstract

Background

Several restaurant chains have committed to reducing sodium levels in their foods; however, how much sodium levels have changed over the past few years is unknown. The objective was to measure changes in sodium in restaurant foods from 2010 to 2013.

Methods

Data for the serving size, calorie and sodium level of 3878 foods were collected from the websites of 61 Canadian restaurant chains in 2010 and 2013. A longitudinal study of changes in sodium levels in foods available from the restaurants in 2010 and 2013 (n = 2198) was conducted. Levels in newly reported and discontinued foods were also investigated.

Results

Sodium levels (mg/serving) decreased in 30.1% of foods, increased in 16.3% and were unchanged in 53.6%. The average change in foods with a decrease in sodium was –220 (standard deviation [SD] ± 303) mg/serving (a decline of 19% [SD ± 17%]), whereas the average change in foods with an increase in sodium was 251 (SD ± 349) mg/serving (a 44% [SD ± 104%] increase). The prevalence and magnitude of change varied depending on the restaurant and food category. Overall, there was a small, yet significant, decrease in sodium per serving (–25 [SD ± 268] mg, p < 0.001); however, the percentage of foods exceeding the daily sodium adequate intake (1500 mg) and tolerable upper intake level (2300 mg) remained unchanged.

Interpretation

The observed increases and decreases in sodium show that industry efforts to voluntarily decrease sodium levels in Canadian restaurant foods have produced inconsistent results. Although the lower levels in some foods show that sodium reduction is possible, the simultaneous increase in other foods demonstrates the need for targets and timelines for sodium reduction in restaurants.

Excessive sodium consumption is a causal risk factor for hypertension,1 which is the leading preventable risk factor for death worldwide.2 Currently, 85% of men and 63%–83% of women in Canada have sodium intakes that exceed the daily recommended tolerable upper intake level (2300 mg).3 Reducing sodium intakes in Canada to the recommended level could produce an annual health care savings of $2.99 billion by decreasing the rate of hypertension and cardiovascular disease events by 30% and 13%, respectively.4 Research has shown that 77% of dietary sodium is derived from processed and restaurant foods. This may be partly due to the prevalence of eating outside the home,5 as well as the high levels of sodium found in restaurant foods.6,7

Efforts such as the National Salt Reduction Initiative in the United States have been established to promote the reduction of sodium in packaged and restaurant foods.8 In addition, several restaurants and food companies have made voluntary commitments to lower sodium levels.9,10 Although the Sodium Working Group in Canada created a plan to track sodium reductions,11 they were disbanded before a monitoring system could be implemented.12 Research conducted in 2010 showed alarmingly high sodium levels in Canadian restaurant foods;6,7 however, according to the Canadian Restaurant and Foodservice Association, many restaurants have decreased their sodium levels since that time.13 Nevertheless, no systematic studies have been conducted to investigate the accuracy of such assertions by the restaurant industry. Therefore, the objective of this study was to measure changes in sodium levels in Canadian restaurant foods from 2010 to 2013.

Methods

We conducted a longitudinal follow-up study to a previous report investigating the sodium levels in Canadian fast-food and sit-down restaurants.6

Restaurants included in the study

The restaurants included in the study were identified using the Directory of Restaurant and Fast-Food Chains in Canada.14 Of the 172 restaurants that had > 20 locations across Canada (20 was selected because this is the cut-off for mandatory menu labelling according to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in the US15), 95 provided nutrition information online in 2010 (data for 3 restaurants were collected in early 2011). Data were downloaded and compiled into the University of Toronto Restaurant Database, which contains nutrition information for over 9000 à la carte entrées, side dishes, beverages, desserts and condiments. Details concerning the database have been described elsewhere.16

In May 2013, we revisited the websites for all 95 restaurants and, if available, downloaded their nutrition data. Thirty-four restaurants were excluded for the following reasons: they did not provide serving size data (n = 8), they only provided data for beverages or ice cream (n = 9), they only provided data for the US (n = 7), they no longer provided publicly available nutrition information (n = 4), they did not provide sodium data (n = 3), they substantially changed the format of the data they provided (n = 2) or they were a cafeteria supplier (n = 1).

Database construction

Data collected in 2013 were entered into the existing database where all foods were categorized according to the restaurant, type of restaurant (fast-food v. sit-down restaurant), food category (e.g., hamburgers, sandwiches, etc.) and type of food (e.g., entrée, side dish, kids’ item, etc.). All foods were categorized according to their “food status” in 2013 (newly reported, discontinued or available in both 2010 and 2013). All data entries and categorizations were double-checked against the original source and subjected to range and logic checks. Matched pairs in 2010 and 2013 were examined to ensure plausibility. We excluded all beverages and ice cream (these foods typically do not contain a large amount of sodium), appetizers (this category is too heterogeneous to make reliable comparisons), sauces and condiments (they were not reported by the majority of restaurants), meals combining entrées and side dishes (we would be unable to determine what component of the meal decreased in sodium), size duplications (per 100 g comparisons would be redundant), and categories with less than 10 items.

Statistical analysis

Primary a priori analyses were the longitudinal changes in sodium levels (per serving and per 100 g) overall, in each restaurant and in each food category. Secondary analyses included the percentage of foods meeting or exceeding sodium intake recommendations, simultaneous changes in calories and serving size, and the difference among foods that were newly reported or discontinued. For foods available in 2010 and 2013 (n = 2198), descriptive statistics and pairwise t tests were used to compare sodium levels per serving and per 100 g. Medians were reported to prevent extreme values from skewing the average. The data was right-skewed in both 2010 and 2013; therefore, Monte Carlo simulations of the exact p values were used to confirm the parametric findings. Additionally, general linear models and Monte Carlo exact simulations that included “restaurant” as a covariate were created to control for this potential confounder. The proportion of foods that had an increase or decrease in sodium was calculated for each restaurant and food category. The χ2 test was used to compare the percentage of entrées with sodium levels (mg/serving) greater than the recommended adequate intake level (1500 mg) and tolerable intake level (2300 mg)17 in 2010 and 2013. In addition, the percentage of entrées with less than 600 mg (the healthy amount for restaurant meals and main dishes according to the US Food and Drug Administration [FDA])18 was also compared in 2010 and 2013. A general linear model was constructed to investigate the effect of food status (newly reported, discontinued or available in both 2010 and 2013) as a predictor of sodium levels while controlling for restaurant and food category. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc.).

Results

Sixty-one restaurants, representing > 15 500 food outlets,19 were included in this study (Table 1). Excluded restaurants, and the reasons for their exclusion are provided in Appendix 1 (available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/2/4/E343/suppl/DC1). A total of 3878 à la carte entrée items, side dishes and baked goods from both regular and children’s menus were analyzed. There were 2198 foods for which data were reported in 2010 and 2013, 860 discontinued foods, and 820 newly reported foods.

Table 1: Restaurant characteristics (n = 61).

| Restaurant | No. of outlets in 2010 | No. of outlets in 2013 | No. of food items meeting inclusion criteria with data provided in 2010 and 2013 | No. of discontinued foods | No. of newly reported foods | Restaurant type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 241 Pizza |

96 |

95 |

10 |

0 |

9 |

FFR |

| A&W |

701 |

772 |

34 |

4 |

6 |

FFR |

| Arby’s |

112 |

53 |

28 |

10 |

6 |

FFR |

| Baton Rouge |

28 |

30 |

16 |

0 |

0 |

SDR |

| Bento Nouveau |

31 |

31 |

5 |

11 |

19 |

FFR |

| Boston Pizza |

333 |

345 |

106 |

30 |

50 |

SDR |

| Burger King |

305 |

317 |

51 |

10 |

3 |

FFR |

| Casey’s Bar and Grill |

37 |

27 |

46 |

28 |

17 |

SDR |

| Coffee Time |

237 |

175 |

30 |

0 |

0 |

FFR |

| Country Style |

533 |

485 |

38 |

93 |

0 |

FFR |

| Dagwoods Sandwiches and Salads |

27 |

25 |

38 |

8 |

9 |

FFR |

| Dairy Queen |

507 |

501 |

18 |

19 |

3 |

FFR |

| Denny’s |

50 |

53 |

124 |

0 |

0 |

SDR |

| Druxy’s Deli |

48 |

45 |

6 |

0 |

4 |

FFR |

| Earl’s Restaurant |

61 |

60 |

28 |

34 |

9 |

SDR |

| East Side Mario’s |

114 |

89 |

45 |

15 |

12 |

SDR |

| Edo Japan |

86 |

103 |

18 |

2 |

19 |

FFR |

| Extreme Pita |

104 |

207 |

43 |

0 |

0 |

FFR |

| Flying Wedge Pizza |

20 |

18 |

14 |

5 |

14 |

FFR |

| Harvey’s |

269 |

250 |

25 |

0 |

0 |

FFR |

| Jack Astor’s |

29 |

34 |

24 |

65 |

19 |

SDR |

| Joey’s Restaurants |

78 |

74 |

20 |

19 |

37 |

SDR |

| Jugo Juice |

105 |

130 |

5 |

3 |

0 |

FFR |

| Kelsey’s |

103 |

97 |

44 |

28 |

27 |

SDR |

| KFC |

731 |

668 |

24 |

31 |

3 |

FFR |

| Little Caesars |

131 |

179 |

14 |

0 |

0 |

FFR |

| Manchu Wok |

77 |

77 |

14 |

0 |

0 |

FFR |

| McDonald’s |

1419 |

1417 |

46 |

32 |

33 |

FFR |

| Mikes |

90 |

85 |

80 |

59 |

55 |

SDR |

| Mmmuffins |

33 |

23 |

46 |

0 |

75 |

FFR |

| Montana’s |

87 |

91 |

75 |

17 |

24 |

SDR |

| Mr. Greek |

26 |

21 |

35 |

4 |

3 |

SDR/FFR* |

| Mr. Sub |

390 |

339 |

49 |

13 |

5 |

FFR |

| Mrs. Vanelli’s Fresh Italian Foods |

65 |

47 |

28 |

0 |

0 |

FFR |

| New Orleans Pizza |

73 |

68 |

20 |

6 |

35 |

FFR |

| New York Fries |

173 |

130 |

5 |

0 |

3 |

FFR |

| Opa! Souvlaki of Greece |

63 |

87 |

6 |

3 |

9 |

FFR |

| Orange Julius |

67 |

81 |

7 |

1 |

0 |

FFR |

| Panago |

174 |

182 |

171 |

0 |

64 |

FFR |

| Pita Pit |

114 |

149 |

9 |

21 |

0 |

FFR |

| Pizza 73 |

79 |

89 |

22 |

2 |

9 |

FFR |

| Pizza Delight |

98 |

91 |

34 |

20 |

21 |

SDR |

| Pizza Hut |

339 |

316 |

73 |

65 |

49 |

SDR |

| Pizza Nova |

120 |

130 |

11 |

0 |

0 |

FFR |

| Pizza Pizza |

550 |

604 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

FFR |

| Pizzaville |

63 |

73 |

25 |

1 |

0 |

FFR |

| Robin’s Donuts |

130 |

140 |

23 |

0 |

0 |

FFR |

| Scores Rotisserie |

34 |

42 |

30 |

11 |

7 |

SDR |

| Shoeless Joe’s |

34 |

32 |

18 |

39 |

12 |

SDR |

| Subway |

2467 |

2896 |

51 |

38 |

60 |

FFR |

| Swiss Chalet |

198 |

208 |

55 |

8 |

0 |

SDR |

| Taco Bell |

191 |

196 |

32 |

9 |

7 |

FFR |

| Taco Del Mar |

61 |

33 |

27 |

27 |

23 |

FFR |

| Taco Time |

118 |

117 |

18 |

12 |

0 |

FFR |

| Teriyaki Experience |

104 |

109 |

74 |

0 |

0 |

FFR |

| The Great Canadian Bagel |

37 |

30 |

85 |

0 |

0 |

FFR |

| Tim Hortons |

2995 |

3437 |

70 |

15 |

24 |

FFR |

| Treats |

86 |

75 |

6 |

12 |

18 |

FFR |

| Van Houtte’s Bistro |

54 |

64 |

24 |

0 |

0 |

FFR |

| White Spot Legendary Restaurant |

64 |

63 |

52 |

30 |

16 |

SDR |

| White Spot Triple O’s | 45 | 36 | 20 | 0 | 2 | FFR |

Note: FFR = fast-food restaurants (encompassing fast-casual restaurants, quick-service restaurants and coffee shops), SDR = sit-down restaurants (defined as restaurants with table service. Many sit-down restaurants may also offer a take-away option). *Restaurant provided separate data for their sit-down and quick-serve menus; because both sets of data were included in the analysis, they were classified as both.

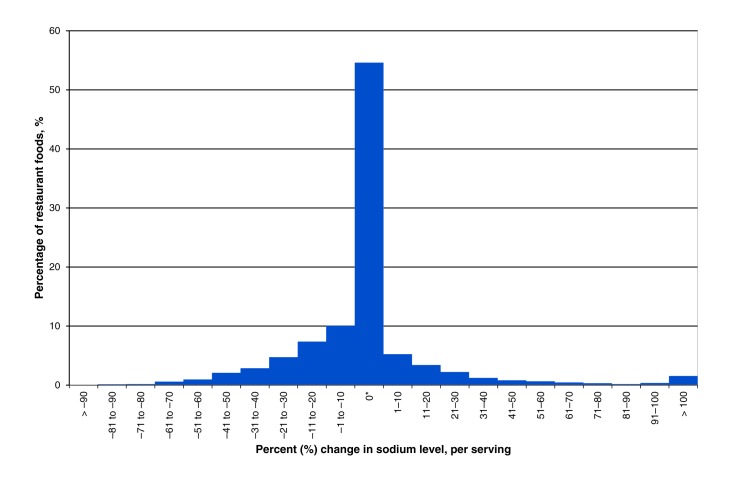

Overall change in sodium levels

Sodium levels (per serving) decreased in 30.1% of foods, increased in 16.3% of foods and remained unchanged in 53.6% of foods (Figure 1). Although the magnitude of the decrease varied, the average change among foods with a decrease in sodium was −220 (SD ± 303) mg/serving, which was, on average, a 19% (SD ± 17%) decline (Table 2). Among foods with an increase in sodium, the average change was 251 (SD ± 349) mg per serving, which was a 44% (SD ± 104%) increase. Overall, there was a small (−25 [SD ± 268] mg), yet significant (p < 0.001), decrease in sodium levels both per serving and per 100 g.

Figure 1:

Percent change in sodium levels (per serving) in foods in chain restaurants in Canada (n = 2198) from 2010 to 2013. *Includes foods with no change in sodium from 2010 to 2013 (54%).

Table 2: Sodium levels in restaurant food items in Canada (2010–2013) .

| Food items | n (%) | Sodium level (mg), mean ± SD |

Sodium, (mg/100 g), mean ± SD |

Serving size (g), mean ± SD |

Calories (kcal/serving), mean ± SD |

Calories (kcal/100 g), mean ± SD |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2013 | Average change | Average percent change | 2010 | 2013 | 2010 | 2013 | 2010 | 2013 | 2010 | 2013 | |||

| Overall |

2198 (100) |

917 ± 694 |

892 ± 679* |

–25 ± 268 |

1 ± 48 |

401 ± 194 |

390 ± 185† |

241 ± 161 |

239 ± 159‡ |

438 ± 287 |

433 ± 288§‡ |

208 ± 97 |

208 ± 98 |

|

| Foods with a decrease in sodium |

662 (30) |

1130 ± 778 |

910 ± 642 |

–220 ± 303 |

–19 ± 17 |

481 ± 212 |

407 ± 190* |

252 ± 171 |

238 ± 161* |

474 ± 293 |

442 ± 275* |

209 ± 83 |

209 ± 88 |

|

| Foods with an increase in sodium |

358 (16) |

842 ± 658 |

1093 ± 858 |

251 ± 349 |

44 ± 104 |

353 ± 175 |

431 ± 197* |

246 ± 163 |

254 ± 167‡ |

468 ± 307 |

497 ± 343§ |

205 ± 71 |

206 ± 71 |

|

| Foods with no change in sodium | 1178 (54) | 821 ± 624 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 371 ± 175 | 368 ± 175* | 234 ± 155 | 235 ± 154§ | 410 ± 284 | 409 ± 274 | 209 ± 110 | 207 ± 110 | ||

Note: SD = standard deviation. *p < 0.0001. †p < 0.01. ‡Paired t tests, p < 0.05. §p < 0.001.

Changes in sodium level by food category

Table 3 illustrates that the change in sodium levels varied depending on the food category. Sodium levels (per serving) decreased significantly in some categories (sit-down pizza, sit-down pasta, sit-down entrées for children, fast-food chicken, and fast-food tacos and burritos, p < 0.05), with the average percent decrease ranging from 7% to 26%.

Table 3: Changes in sodium levels from 2010 to 2013, by food category (n = 1580).

| Food category | No. of food items | Sodium level (mg/serving), mean ± SD* |

Food items with a decrease in sodium level |

Food items with an increase in sodium level |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2013 | n (%) | Percent change; median (25th, 75th percentile) |

n (%) | Percent change; median (25th, 75th percentile) | ||

|

Sit-down restaurant |

|||||||

| Stir fry entrées |

10 |

2198 ± 986 |

2209 ± 802 |

1 (10.0) |

–50 |

4 (40.0) |

25 (8, 67) |

| Sandwiches or wraps |

73 |

1906 ± 1083 |

1933 ± 933 |

21 (28.8) |

–8 (–23, –4) |

22 (30.1) |

21 (9, 49) |

| Pasta entrées |

76 |

1822 ± 738 |

1619 ± 723† |

49 (64.5) |

–11 (–22, –7) |

10 (13.2) |

12 (3, 17) |

| Entrées with multiple meats and seafood (e.g., surf-n-turf) |

12 |

1821 ± 798 |

1862 ± 802 |

1 (8.3) |

0 |

3 (25.0) |

6 (6, 14) |

| Hamburgers |

39 |

1653 ± 657 |

1753 ± 642‡ |

13 (33.3) |

–7 (–8, –6) |

11 (28.2) |

35 (21, 57) |

| Breakfast entrées (e.g., pancakes, waffles, or eggs and bacon) |

74 |

1595 ± 678 |

1573 ± 681 |

19 (25.7) |

–24 (–35, –8) |

18 (24.3) |

13 (2, 47) |

| Rib entrées |

19 |

1594 ± 712 |

1717 ± 956 |

3 (15.8) |

–4 (–4, –2) |

1 (5.3) |

137 |

| Salad entrée with meat |

41 |

1218 ± 447 |

1259 ± 487 |

8 (19.5) |

–11 (–16, –9) |

13 (31.7) |

20 (13, 29) |

| Chicken entrées |

42 |

1145 ± 669 |

1142 ± 731 |

10 (23.8) |

–28 (–44, –11) |

9 (21.4) |

25 (18, 41) |

| Salad entrées |

19 |

863 ± 434 |

908 ± 394 |

7 (36.8) |

–20 (–25, –9) |

6 (31.6) |

54 (18, 182) |

| Steak and beef entrées |

36 |

832 ± 816 |

836 ± 777 |

9 (25.0) |

–15 (–39, –8) |

6 (16.7) |

135 (39, 217) |

| Seafood entrées |

24 |

804 ± 588 |

811 ± 578 |

2 (8.3) |

–38 (–40, –36) |

3 (12.5) |

48 (34, 64) |

| Pizza (one medium slice) |

93 |

575 ± 204 |

446 ± 163† |

85 (91.4) |

–17 (–12, 32) |

7 (7.5) |

17 (12, 32) |

|

Fast-food restaurant |

|||||||

| Stir fry |

24 |

1766 ± 181 |

1766 ± 181 |

0 (0.0) |

0 |

0 (0.0) |

0 |

| Poutine |

15 |

1617 ± 722 |

1505 ± 476 |

6 (40.0) |

–17 (–23, –6) |

3 (20.0) |

8 (1, 129) |

| Tacos or burritos |

61 |

1389 ± 852 |

1123 ± 618† |

48 (78.7) |

–21 (–34, –11) |

12 (19.7) |

16 (4, 32) |

| Sandwiches or wraps |

203 |

1354 ± 554 |

1327 ± 659 |

82 (40.4) |

–18 (–25, –12) |

33 (16.3) |

23 (10, 56) |

| Hot dogs |

13 |

1203 ± 236 |

1163 ± 264 |

8 (61.5) |

–10 (–13, –6) |

4 (30.8) |

4 (1, 31) |

| Salads with meat |

22 |

1094 ± 282 |

1047 ± 342 |

12 (54.5) |

–11 (–28, –8) |

3 (13.6) |

60 (21, 67) |

| Hamburgers |

60 |

1061 ± 307 |

1039 ± 319 |

33 (55.0) |

–6 (–11, –4) |

5 (8.3) |

20 (18, 73) |

| Stir fry (no sodium or low sodium) |

37 |

1041 ± 246 |

1041 ± 246 |

0 (0.0) |

0 |

0 (0.0) |

0 |

| Sushi |

11 |

897 ± 261 |

961 ± 236 |

0 (0.0) |

0 |

4 (36.4) |

35 (14, 36) |

| Chicken |

47 |

777 ± 338 |

689 ± 301§ |

20 (42.6) |

–20 (–25, –13) |

3 (6.4) |

7 (2, 97) |

| Breakfast (e.g., bagels or breakfast sandwiches) |

113 |

721 ± 427 |

710 ± 397 |

28 (28.3) |

–5 (–11, –1) |

14 (14.1) |

6 (2, 13) |

| Pasta |

25 |

718 ± 335 |

718 ± 335 |

0 (0.0) |

0 |

0 (0.0) |

0 |

| Salads |

20 |

588 ± 222 |

646 ± 311 |

2 (10.0) |

–32 (–44, –20) |

4 (20.0) |

71 (37, 107) |

| Pizza (one medium slice) |

263 |

432 ± 211 |

436 ± 211 |

56 (21.3) |

–9 (–17, –5) |

76 (28.9) |

14 (6, 22) |

|

Kid’s menu items |

|||||||

| Sit-down restaurant kid’s meal entrées |

68 |

760 (567, 1008) |

730 (535, 972)‡ |

21 (30.1) |

–26 (–39, –13) |

10 (14.7) |

10 (6, 36) |

| Fast-food kid’s meal entrées (e.g., hamburger or nuggets) |

13 |

752 (592, 900) |

717 (686, 770) |

3 (23.1) |

–24 (–34, –22) |

3 (23.1) |

16 (11, 17) |

| Sit-down restaurant kid’s side dishes | 27 | 420 (75, 570) | 380 (85, 520) | 9 (33.3) | –30 (–32, –23) | 3 (11.1) | 140 (54, 258) |

Note: SD = standard deviation. Additional analysis using general linear models to predict the change in sodium while including establishment as a covariate produced the same results and confirmed that establishment is not a covariate. Data for baked goods, desserts and side dishes are provided in Appendix 1 (Supplementary Table 2, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/2/4/E343/suppl/DC1). Data for changes in sodium density (sodium per 100 g) in each category are provided in Appendix 1 (Supplementary Table 3, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/2/4/E343/suppl/DC1). *Unless otherwise indicated. †p < 0.001. ‡Paired t tests, p < 0.05. §p < 0.01.

Changes in sodium level by restaurant

The degree to which sodium levels changed varied depending on the restaurant (Table 4). Although sodium levels were completely unchanged in 17 restaurants (28% of the sample), most restaurants had both increases and decreases within their menu. In certain restaurants (such as Subway, Pizza Hut, Taco Bell and Taco Time) sodium levels decreased by at least 20% in more than 70% of foods surveyed. However, in certain restaurants, despite large decreases in some foods, there were equally large increases in others.

Table 4: Changes in sodium levels from 2010 to 2013, by restaurant (n = 1603) .

| Restaurant | n | Food items with a decrease in sodium level |

Food items with an increase in sodium level |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Percent change; median (25th, 75th percentile) | n (%) | Percent change; median (25th, 75th percentile) | ||

| Subway* |

51 |

44 (86.3) |

–20 (–27, –15) |

4 (7.8) |

2 (1, 2) |

| Pizza Hut* |

73 |

57 (78.1) |

–37 (–44, –17) |

3 (4.1) |

4 (1, 41) |

| Taco Bell* |

32 |

25 (78.1) |

–20 (–31, –13) |

3 (9.4) |

8 (2, 10) |

| Taco Time |

18 |

14 (77.8) |

–35 (–50, –13) |

4 (22.2) |

8 (1, 73) |

| Shoeless Joe’s |

18 |

13 (72.2) |

–22 (–27, –12) |

5 (27.8) |

25 (25, 39) |

| Burger King |

51 |

36 (70.6) |

–3 (–7, –1) |

1 (1.9) |

33† |

| Boston Pizza |

106 |

72 (67.9) |

–8 (–18, –5) |

22 (20.75) |

13 (10, 44) |

| Dagwood Sandwiches and Subs |

38 |

25 (65.8) |

–16 (–23, –13) |

12 (31.6) |

21 (8, 56) |

| White Spot Triple O’s |

20 |

13 (65.0) |

–16 (–24, –15) |

0 (0.0) |

NA |

| Dairy Queen |

18 |

11 (61.1) |

–7 (–30, –6) |

6 (33.3) |

18 (16, 20) |

| A&W |

34 |

20 (58.8) |

–7 (–12, –4) |

10 (29.4) |

11 (3, 15) |

| East Side Mario’s |

45 |

26 (59.1) |

–11 (–24, –6) |

13 (29.5) |

17 (8, 32) |

| Taco Del Mar |

27 |

15 (55.6) |

–25 (–33, –11) |

11 (40.7) |

23 (9, 36) |

| KFC* |

24 |

13 (54.2) |

–23 (–37, –19) |

3 (12.5) |

23 (7, 97) |

| Joey’s Restaurant |

20 |

10 (50.0) |

–13 (–54, –8) |

10 (50.0) |

66 (14, 96) |

| Mike’s Restaurant |

80 |

38 (47.5) |

–25 (–46, –12) |

35 (43.75) |

31 (10, 106) |

| White Spot Legendary Restaurant |

52 |

23 (44.2) |

–10 (–29, –5) |

13 (25.0) |

33 (4, 67) |

| Arby’s |

28 |

12 (42.9) |

–9 (–18, –5) |

15 (53.6) |

25 (16, 118) |

| Kelsey’s |

44 |

17 (38.6) |

–10 (–27, –10) |

17 (38.6) |

20 (9. 33) |

| Panago |

171 |

62 (36.3) |

–9 (–17, –5) |

74 (43.3) |

16 (7, 25) |

| Tim Hortons |

70 |

24 (34.3) |

–9 (–20, –4) |

8 (11.4) |

9 (6, 21) |

| Jack Astor’s |

24 |

8 (33.3) |

–30 (–52, –17) |

16 (66.7) |

65 (20, 173) |

| Montana’s |

75 |

22 (29.3) |

–30 (–36, –25) |

15 (20.0) |

21 (13, 54) |

| Mr. Greek |

35 |

9 (25.7) |

–1 (–43, –1) |

2 (5.7) |

21 (14, 54) |

| Edo Japan |

18 |

4 (22.2) |

–9 (–10, –10) |

0 (0.0) |

NA |

| McDonald’s* |

46 |

12 (26.1) |

–8 (–18, –7) |

10 (21.7) |

11 (6, 19) |

| Harvey’s |

25 |

5 (20.0) |

–14 (–19, 14) |

0 (0.0) |

NA |

| Casey’s |

46 |

8 (17.4) |

–14 (–30, –4) |

6 (13.0) |

29 (12, 43) |

| Scores Rotisserie |

30 |

5 (16.7) |

–12 (–24, –11) |

6 (20.0) |

5 (2, 18) |

| Pizza Delight |

34 |

4 (11.8) |

–12 (–14, –9) |

1 (2.9) |

14 |

| New Orleans Pizza |

20 |

2 (10.0) |

–40 (–69, –11) |

17 (85.0) |

52 (13, 51) |

| Earl’s Restaurant |

28 |

1 (3.6) |

0 (0.0) |

2 (7.1) |

23 (5, 42) |

| Extreme Pita |

43 |

0 (0.0) |

NA |

0 (0.0) |

NA |

| Mmmuffins |

46 |

0 (0.0) |

NA |

0 (0.0) |

NA |

| Mrs. Vanelli’s Fresh Italian Foods |

28 |

0 (0.0) |

NA |

1 (3.6) |

13 |

| The Great Canadian Bagel | 85 | 0 (0.0) | NA | 0 (0.0) | NA |

Note: NA = not applicable. The following restaurants reported no changes in sodium levels between 2010 and 2013: 241 Pizza, Baton Rouge, Coffee Time, Country Style, Denny’s, Flying Wedge Pizza, Little Caesars, Manchu Wok, Mr. Sub, Pita Pit, Pizza 73, Pizza Nova, Pizzaville, Robin’s Donuts, Swiss Chalet, Teriyaki Experience and Van Houtte’s Bistro. The following restaurants were excluded because they had less than 10 menu items included in this study: Bento Nouveau, Druxy’s Deli, Jugo Juice, New York Fries, Opa, Orange Julius, Pizza Pizza and Treats. Data for changes in sodium density (sodium per 100 g) in each restaurant can be found in Appendix 1 (Supplementary Table 4, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/2/4/E343/suppl/DC1). *Indicates restaurants that have made a voluntary commitment to reducing the sodium level in their products. †When there was only one food that increased or decreased, the percent change in that food was presented without an indicator of variance.

Similar results were seen when sodium levels were standardized (mg per 100 g) (Appendix 1, Supplementary Tables 3 and 4, www.cmajopen.ca/content/2/4/E343/suppl/DC1).

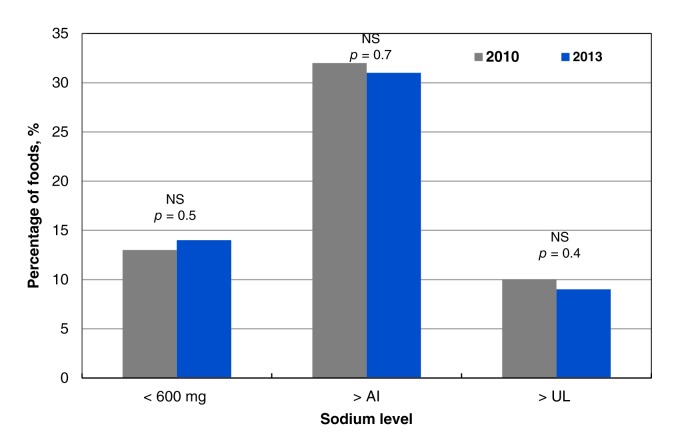

Proportion of foods exceeding the recommended daily intake levels for sodium

There was no significant change in the percentage of entrées exceeding the daily sodium adequate intake level (p = 0.7) or tolerable upper intake limit (p = 0.4) (Figure 2). Restaurants decreased sodium levels in 39% of foods that exceeded the adequate intake level in 2010; however, they simultaneously increased the sodium levels in 18% of foods that already exceeded the adequate intake level. Sodium levels were lowered in 51% of foods in which sodium levels exceeded the tolerable upper intake limit in 2010; however, sodium levels were increased in 12% of foods in which sodium levels exceeded the tolerable upper intake level in 2010. Additionally, there was no significant change (p = 0.5) in the percentage of entrées that contained a “healthy” amount of sodium (< 600 mg per meal/main dish, according to the US FDA17) in 2013 versus 2010.

Figure 2:

Percentage of restaurant entrees (n = 1004) in three categories: (1) < 600 mg of sodium (the US Food and Drug Administration defines 600 mg of sodium as a “healthy level” for a restaurant meal);18 (2) exceeding the daily recommended adequate intake level (AI, 1500 mg) and (3) exceeding the tolerable upper intake level (UL, 2300 mg) as defined by the Institute of Medicine18 in 2010 and 2013. NS = not significant according to χ2 tests. This graph compares the sodium level in a single entrée (without the accompanying side dishes) to the healthy level for meals and main dishes. The entrées represented include chicken, hamburgers, pastas, ribs, salads, stir-fries and sandwiches or wraps. Therefore, these proportions underestimate the amount of sodium that would typically be consumed at a chain restaurant. Newly reported and discontinued entrées were not included because the different types of entrées were not equally represented in these 2 groups and therefore could bias the outcome. See Appendix 1 (Supplementary Table 5, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/2/4/E343/suppl/DC1) for data concerning discontinued and newly added foods.

Sodium levels in newly reported, discontinued and persisting foods

When controlling for restaurant and food category, there was no significant difference (p = 0.3) in the sodium level of foods that were newly reported (983 [SD ± 730] mg/serving) in comparison to foods that were discontinued (993 [SD ± 706] mg/serving) or foods that were on the menu in 2010 and 2013 (892 [SD ± 679] mg/serving) (Appendix 1, Supplementary Table 5).

Changes in serving size and calories

Foods with a decrease in sodium (mg/serving) from 2010 to 2013 also had a significant decrease in serving size, sodium per 100 g and calories (p < 0.0001) (Table 1). In addition, foods with an increase in sodium level had a significant increase in serving size, sodium per 100 g and calories (p < 0.05). The number of calories per 100 g did not change in foods in which sodium levels increased or decreased.

Interpretation

Main findings

From 2010 to 2013 sodium levels decreased in 30.1% of foods, increased in 16.3% and remained unchanged in 53.6%. The percentage of foods that increased or decreased and the magnitude of the change varied depending on the restaurant and food category. Changes in sodium levels arose because of both altered serving size and sodium density. The number of menu items with unacceptably high amounts of sodium (exceeding the adequate intake level and tolerable upper intake level) did not change. This study shows that industry efforts to voluntarily decrease sodium levels in restaurant foods in Canada have produced inconsistent results.

Comparison with other studies

Previous studies in the US also have shown that both healthy and unhealthy changes in sodium levels are occurring simultaneously. When comparing identical restaurant foods in 2005, 2008 and 2011, Jacobson and colleagues found a 2.6% increase in sodium levels.9 Meanwhile, Wu and Strum found no change in sodium levels between 2010 and 2011.20

Our data showed that many of the leaders in sodium reduction are restaurants that have made voluntary commitments to reduce the sodium level in their foods (Subway, Pizza Hut, Taco Bell and KFC).9,10 However, all of the restaurants that have made commitments still offer foods that exceed the adequate intake level for sodium, and some even increased sodium levels in certain products. This illustrates how voluntary, industry-designed commitments, such as those that aim to produce an average percentage reduction in sodium across a restaurant’s entire menu, are not ideal because they allow large reductions in certain foods to mask increases in others.

Consuming excessive sodium has been shown to increase a person’s taste preference for foods high in sodium.21–23 However, it is well established that gradually reducing sodium levels is an effective way to retrain the taste buds of consumers to prefer foods that are lower in sodium.24–27 This study shows that the first gradual step toward sodium reduction has been taken by some restaurants; nevertheless, further decreases are still needed to reduce the amount of sodium in restaurant foods to an acceptable level.

Despite the creation of voluntary sodium reduction targets for grocery foods in Canada28 and restaurant targets in the US,9 targets for restaurant foods in Canada are yet to be established. Restaurant foods in Canada have higher sodium levels when compared with foods in countries such as the United Kingdom, which has a government−industry agreement to lower sodium levels.29 Additionally, targets may not be the only way to motivate sodium reduction; research has shown that menu-labelling laws requiring the disclosure of sodium information, such as those implemented in King County, Washington, and also proposed by Toronto Public Health,30–32 may also promote sodium reduction.33

In this study, decreased sodium levels resulted from a combination of both reductions in serving size and sodium density. It is important to note that reduction targets and commitments must aim to lower sodium levels per serving and per 100 g to ensure that sodium reduction is not achieved solely via decreases in serving size. Additionally, given the large number of menu items with sodium levels exceeding the daily adequate intake level (22%) and tolerable upper intake level (10%), reduction target maxima are needed to reduce sodium levels in products that are exceptionally high in sodium. Even though our study showed no change in calorie density, sodium-reduction programs should also ensure that potentially adverse nutrients are not increased to compensate for decreases in sodium.

Limitations

This study included 64% of the top 50 restaurants in Canada (by number of outlets),19 therefore, our sample may not be representative of the entire restaurant food supply because of the number of restaurants that did not disclose nutrition data (Table 1). In addition, this study may not include all menu items from the restaurants represented in the sample. The extent to which the exclusion of restaurants that did not meet the study criteria may have biased the results, in either direction, is unknown. Foods that were “newly reported” in 2013 may not exclusively represent “new menu items” because some restaurants may have reported nutrition information for more menu items in 2013 than in 2010. This may have masked potentially lower sodium levels in new menu items. The accuracy of the findings presented in this study is dependent on the accuracy of the self-reported data provided by the establishments. Furthermore, this study represents the sodium level in foods available in restaurants and does not necessarily reflect consumption. A study in the UK investigating purchase-weighted mean sodium in processed foods showed that mean sodium was 18%–35% higher than unweighted sodium levels.34 More research is needed to understand the effect of market share or purchase weighting on this data. Finally, this study does not shed light on how the sodium levels were reduced (e.g., use of mineral salts [potassium chloride or magnesium sulfate], yeast extracts [hydrolyzed vegetable protein], amino acids, dendritic salt or salt enhancers).27,35

Conclusion

From 2010 to 2013 sodium levels in the majority of restaurant foods in Canada were unchanged. The decreases seen in certain restaurants illustrate that sodium reduction is possible. However, the observed increases in some foods show that industry-wide commitments and a systematic monitoring program are needed. This study highlights the importance of establishing targets for sodium reduction in restaurant foods in Canada, and the need for a government-enforced sodium-reduction strategy with regular monitoring. In conclusion, owing to the slow rate of progress over the past 3 years, alongside high rates of hypertension and cardiovascular disease, addressing the high sodium levels in restaurant foods continues to be a public health priority, and an essential step toward decreasing the burden of diet-related chronic disease.

Supplemental information

For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/2/4/E343/suppl/DC1

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Sahar Qassem and Zhila Semnani-Azad for assistance with data entry, as well as Paul Corey for his statistical guidance.

References

- 1.Intersalt: an international study of electrolyte excretion and blood pressure. Results for 24-hour urinary sodium and potassium excretion. Intersalt Cooperative Research Group. BMJ 1988;297:319-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, et al. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet 2006;367:1747-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canadian community health survey, Cycle 2.2, nutrition. Nutrient intakes from food: provincial, regional and national summary tables. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joffres MR, Campbell NR, Manns B, et al. Estimate of the benefits of a population-based reduction in dietary sodium additives on hypertension and its related health care costs in Canada. Can J Cardiol 2007;23:437-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garriguet D. Canadians’ eating habits. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scourboutakos MJ, L’Abbe M. Sodium levels in Canadian fast-food and sit-down restaurants. Can J Public Health 2013;104:e2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scourboutakos MJ, Semnani-Azad Z, L’Abbe MR. Restaurant meals: almost a full day’s worth of calories, fats, and sodium. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1373-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Salt Reduction Initiative restaurant food categories and targets. New York: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2013. Available: www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/cardio/cardio-salt-nsri-restaurant.pdf (accessed: 2014 Oct. 29).

- 9.Jacobson MF, Havas S, McCarter R. Changes in sodium levels in processed and restaurant foods, 2005 to 2011. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1285-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nutritional improvement: sodium. Yum! Brands corporate responsibility report. Louisville (KY): Yum! 2013. Available: www.yumcsr.com/food/nutritional-improvement.asp (accessed 2014 Oct. 29).

- 11.Sodium reduction strategy for Canada: recommendations of the Canadian Sodium Working Group Ottawa: Health Canada; 2010. Available: www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/nutrition/sodium/related-info-connexe/strateg/reduct-strat-eng.php (accessed 2014 Oct. 30).

- 12.Schmidt S. Federal inaction on limiting Canadians’ salt intake criticized. Postmedia News 2012 June 12.

- 13.Weeks C. Researchers ‘shocked’ by sodium levels at Canadian restaurants. The Globe and Mail [Toronto] 2013 Feb. 27.

- 14.Monday report on retailers: directory of restaurant & fast food chains in Canada. Toronto: Rogers Publishing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stein K. A national approach to restaurant menu labeling: the Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act, Section 4205. J Am Diet Assoc 2010;110:1280-6, 1288-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scourboutakos MJ, L’Abbe MR. Restaurant menus: calories, caloric density, and serving size. Am J Prev Med 2012;43:249-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dietary reference intakes for water, potassium, sodium, chloride, and sulfate. Institute of Medicine; 2004.

- 18.Food and Drug Administration . Food labeling; nutrient content claims, definition of sodium levels for the term “healthy.” Final rule. Fed Regist 2005;70:56828-49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monday report on retailers: 2013 Directory of restaurant & fast-food chains in Canada. Toronto: Rogers Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu HW, Sturm R. Changes in the energy and sodium content of main entrees in US chain restaurants from 2010 to 2011. J Acad Nutr Diet 2014;114:209-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bertino M, Beauchamp GK, Engelman K. Increasing dietary salt alters salt taste preference. Physiol Behav 1986;38:203-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim GH, Lee HM. Frequent consumption of certain fast foods may be associated with an enhanced preference for salt taste. J Hum Nutr Diet 2009;22:475-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayes JE, Sullivan BS, Duffy VB. Explaining variability in sodium intake through oral sensory phenotype, salt sensation and liking. Physiol Behav 2010;100:369-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodgers A, Neal B. Less salt does not necessarily mean less taste. Lancet 1999;353:1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertino M, Beauchamp GK, Engelman K. Long-term reduction in dietary sodium alters the taste of salt. Am J Clin Nutr 1982;36:1134-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Girgis S, Neal B, Prescott J, et al. A one-quarter reduction in the salt content of bread can be made without detection. Eur J Clin Nutr 2003;57:616-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dötsch M, Busch J, Batenburg M, et al. Strategies to reduce sodium consumption: a food industry perspective. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2009;49:841-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reducing the sodium intake of Canadians: a provincial and territorial report on progress and recommendations for future action Provincial-Territorial Ministers of Health; 2012; Available: www.health.gov.bc.ca/library/publications/year/2012/reducing-sodium-intake.pdf (accessed 2014 Oct. 30).

- 29.Dunford E, Webster J, Woodward M, et al. The variability of reported salt levels in fast foods across six countries: opportunities for salt reduction. CMAJ 2012;184:1023-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finkelstein EA, Strombotne KL, Chan NL, et al. Mandatory menu labeling in one fast-food chain in King County, Washington. Am J Prev Med 2011;40:122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.What’s on the menu? Making key nutrition information readily available in restaurants. Toronto: Toronto Public Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Menu labeling requirements, Philadelphia City Code Philadelphia: Public Health: City of Philadelphia; 2010. Available: www.phila.gov/health/pdfs/Menu%20Labeling%20Requirements.pdf (accessed 2014 Oct. 30).

- 33.Bruemmer B, Krieger J, Saelens BE, et al. Energy, saturated fat, and sodium were lower in entrées at chain restaurants at 18 months compared with 6 months following the implementation of mandatory menu labeling regulation in King County, Washington. J Acad Nutr Diet 2012;112:1169-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ni Mhurchu C, Capelin C, Dunford EK, et al. Sodium content of processed foods in the United Kingdom: analysis of 44 000 foods purchased by 21 000 households. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;93:594-600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sodium reduction market by ingredients, applications & geography — Global trends & forecasts to 2018 Dublin: Research and Markets; 2013. Available: www.researchandmarkets.com/research/nkh4xt/sodium_reduction (accessed 2014 Oct. 30).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.