Abstract

Under normal physiological conditions, the open probability of Slo2.1 K+ channels is low. Elevation of cytosolic [Na+] and [Cl−] caused by ischemia or rapid electrical pacing of cells increases the open probability of Slo2.1 channels and the resulting outward current can stabilize the resting state of cells. Initial characterization of heterologously expressed human Slo2.1 indicated that these channels were inhibited by physiological levels of intracellular ATP. However, a subsequent study found that intracellular ATP had no effect on Slo2.1 channels. Here, we re‐examine the effects of intracellular ATP on cloned human Slo2.1 channels heterologously expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Our studies provide both direct and indirect evidence that changes in intracellular [ATP] have no effect on Slo2.1 channels. First, we directly examined the effects of intracellular ATP on Slo2.1 channel activity in excised inside‐out macropatches from Xenopus oocytes. Application of 5 mmol/L ATP to the intracellular solution did not inhibit Slo2.1 currents activated by niflumic acid. Second, we lowered the [ATP]i in whole oocytes using the metabolic inhibitor NaN3. Depletion of [ATP]i in oocytes by 3 mmol/L NaN3 rapidly activated heterologously expressed KATP channels, but did not increase wild‐type Slo2.1 channel currents activated by niflumic acid or currents conducted by constitutively active mutant (E275D) Slo2.1 channels. Third, mutation of a conserved residue in the ATP binding consensus site in the C‐terminal domain of the channel did not enhance the magnitude of Slo2.1 current as expected if binding to this site inhibited channel function. We conclude that Slo2.1 channels are not inhibited by intracellular ATP.

Keywords: ATP, KCNT2, oocytes, potassium channels, Xenopus

Initial characterization of heterologously expressed human Slo2.1 indicated that these channels were inhibited by physiological levels of intracellular ATP. Here, we re‐examine the effects of intracellular ATP on cloned human Slo2.1 channels heterologously expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Our studies provide both direct and indirect evidence that changes in intracellular [ATP] have no effect on Slo2.1 channels.

Introduction

Intracellular Na+‐activated K+ (KNa) channels were first described in guinea pig cardiomyocytes 30 years ago (Kameyama et al. 1984) and later in cultured trigeminal ganglion neurons from quail embryos (Bader et al. 1985; Haimann et al. 1990). KNa channels in neurons can either be activated by Na+ ions that are conducted by voltage‐activated Na+ channels during the rapid upstroke phase of action potentials (Bader et al. 1985) or by a persistent inward Na+ current (Budelli et al. 2009). However, in the heart it appears that KNa channels are only activated under pathological conditions such as hypoxia or ischemia (Kameyama et al. 1984). The molecular basis of KNa channels was discovered in 2003 with the cloning of Slo2.1 (Bhattacharjee et al. 2003) and Slo2.2 (Yuan et al. 2003). Based on RT‐PCR, Slo2.1 is expressed in most tissues, including the brain, heart, skeletal muscle, lung and liver, whereas Slo2.2 is highly expressed within specific regions of the brain, and to a lesser extent in the kidney, testis, and very weakly in the heart (Yuan et al. 2003). The Slo2.1 channel was first described as a functional hybrid between a KNa and KATP channel because it was activated by intracellular Na+ (and Cl−) and inhibited by intracellular ATP (Bhattacharjee et al. 2003). Activation of large conductance Slo2.1 K+ channels in response to elevated [Na+]i and depletion of intracellular ATP as occurs during hypoxia or ischemia might protect cardiomyocytes or neurons from damage such as Ca2+‐overload by stabilizing the resting (hyperpolarized) state of the cell.

Consistent with its proposed sensitivity to changes in [ATP]i, Slo2.1 channels contain a consensus ATP binding site just C‐terminal to the second cytoplasmic RCK (regulate conductance of K+) domain. Inhibition of Slo2.1 currents by intracellular ATP (~80% reduction at 5 mmol/L) in whole cells or excised membrane patches of CHO cells transfected with Slo2.1 cDNA was reported to be dependent on the integrity of this motif (Bhattacharjee et al. 2003). However, subsequent studies on striatal interneurons and HEK293T cells transfected with Slo2.1 cDNA showed no effect of intracellular ATP on Slo2.1 channel activity (Berg et al. 2007), consistent with the early studies of cardiac KNa channels (presumably Slo2.1) that were recorded in the presence of 2 mmol/L K2ATP in the intracellular solution (Kameyama et al. 1984). Moreover, we have found that heterologously expressed human Slo2.1 channels can be robustly activated by either niflumic acid (NFA) or elevation of [NaCl]i (Dai et al. 2010; Garg et al. 2013; Garg and Sanguinetti 2012) in intact Xenopus oocytes where [ATP]i is estimated to be 4.6 mmol/L (Gribble et al. 2000). As inhibition of Slo2.1 by intracellular ATP has been cited as one of the defining features of these channels (Bhattacharjee and Kaczmarek 2005; de Los Angeles Tejada et al. 2012; Garg et al. 2013; Garg and Sanguinetti 2012; Kaczmarek 2013; Paulais et al. 2006), in this study we have investigated the effects of altering cytosolic [ATP] on heterologously expressed human Slo2.1 channels in intact Xenopus oocytes and in excised inside‐out macropatches.

Materials and Methods

Molecular biology

cDNA for human Slo2.1 (KCNT2, NCBI Genbank accession no. NM_198503), kindly provided by L. Kaczmarek (Yale University), was subcloned into the psGEM oocyte expression vector as described (Dai et al. 2010). K1031A Slo2.1 was generated by using the QuikChange site‐directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies) and confirmed by DNA sequencing by the University of Utah sequencing core facility. Human Kir6.2 (KCNJ11) and rat SUR1 (ABCC8) cDNAs in the pBF vector were kindly provided by F. Ashcroft (University of Oxford). Plasmids were linearized with SfiI (Slo2.1) or Mlu1 (Kir6.2, SUR1). cRNAs were prepared using the mMessage mMachine T7 kit (Slo2.1) or SP6 kit (Kir6.2, SUR1) (Ambion, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Concentrations of cRNA were measured with the RiboGreen RNA quantitation kit (Invitrogen, Life Technologies).

Oocyte isolation and cRNA injection

Methods for isolation of oocytes from Xenopus laevis were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Utah. Briefly, adult female frogs were anesthetized by immersion in a 0.2% tricaine methanesulfonate solution. A small surgical incision was made to remove the ovarian lobes. To separate the individual oocytes from follicle cells, ovarian lobes were manually dispersed using tweezers and placed into a Ca2+‐free saline solution containing 2 mg/ml each of type I and II collagenase (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Lakewood, NJ) and gently shaken for 1–1.5 h. The Ca2+‐free saline solution contained (in mmol/L): 96 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1 MgCl2, and 5 HEPES; pH was adjusted to 7.6 with NaOH.

To study ISlo2.1, stage IV and V oocytes were injected with 1 ng Slo2.1 cRNA for whole cell recordings or 15 ng cRNA for excised‐patch recordings. To study ATP‐sensitive K+ channel current (IKATP), oocytes were injected with 25 ng Kir6.2 and 46 ng SUR1 cRNA. Injected oocytes were incubated at 18°C for 1–7 days (Slo2.1) or 3 days (Kir6.2/SUR1) in Barth's saline solution before use in voltage clamp experiments. Barth’ solution contained (in mmol/L): 88 NaCl, 1 KCl, 0.41 CaCl2, 0.33 Ca(NO3)2, 1 MgSO4, 2.4 NaHCO3, 10 HEPES, and 1 pyruvate plus gentamycin (50 mg/L); pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH.

Two‐electrode voltage‐clamp protocol

Standard two‐electrode voltage‐clamp (TEVC) techniques (Goldin 1991; Stuhmer 1992) were used to record whole cell Slo2.1 K+ channel current (ISlo2.1) at room temperature. Oocytes were placed in a small chamber (0.3 mL volume, RC‐1Z; Warner Instruments) and superfused at a rate of ~2 mL/min with recording solution that contained (in mmol/L): 98 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, and 5 mmol/L HEPES; pH adjusted to 7.6 with NaOH. To study IKATP, this solution was modified by omitting NaCl and increasing the [KCl] to 104 mmol/L.

Agarose‐cushion microelectrodes used for TEVC recordings were fabricated as described previously (Schreibmayer et al. 1994) and had tip resistances ranging from 0.2 to 0.8 MΩ after back‐filling with 3 M KCl. A Dell 2400 computer, GeneClamp 500 amplifier, Digidata 1322A data acquisition system, and pCLAMP 8.2 or 9.0 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) were used to produce voltage protocols and to record digitized current and voltage signals.

Macropatch recordings

Multi‐channel patch recordings of ISlo2.1 were performed using the standard excised inside‐out configuration of the patch clamp technique (Hamill et al. 1981). The vitelline membrane from each oocyte was removed manually after treatment with hypertonic solution (400 mmol/L sucrose) for 2–6 min. Patch pipettes were fabricated from 1 mm OD borosilicate glass capillaries (World Precision Instruments, Sarasoto, FL) using a Sutter Instruments P‐97 puller (Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA). Pipette tips were heat polished after pulling and had a resistance of 2–4 MΩ when filled with a pipette (extracellular) solution that contained (in mmol/L): 90 NaCl, 10 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES and 2 niflumic acid (NFA); pH was adjusted to 7.2 with NaOH. NFA was added to the pipette solution to activate ISlo2.1. The bath (intracellular) solution contained (in mmol/L): 90 KCl, 10 NaCl, 2 EGTA, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES and 10 μM phosphatidylinositol 4,5‐bisphosphate diC8 (PI(4,5)P2 diC8); pH was adjusted to 7.2 with KOH. During the day of recording, the stock solution of PI(4,5)P2 diC8 was kept on ice until just before use when it was added to the intracellular solution.

A Dell computer, Axopatch 200B patch clamp amplifier, Digidata 1322A data acquisition system and pCLAMP 9.0 software (Molecular Devices) were used to produce command voltage steps and to record currents. Currents were digitized at 5 kHz after on‐line filtering at 1 kHz with an eight‐pole low‐pass Bessel filter. After patch excision, macroscopic ISlo2.1 was recorded for at least 4 min to ensure stability before 5 mmol/L K2ATP was added to the intracellular solution. Currents were recorded during 1‐s voltage ramps applied from +80 to −140 mV. The holding potential was −80 mV and the interval between voltage ramps was 5 s.

Data analysis

pCLAMP9 (Molecular Devices) and Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) software were used to analyze digitized data, and Origin 8.5 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA) was used to prepare figures. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. (n = number of oocytes). Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Statistical significance was evaluated using paired Student's T‐test or ANOVA (one‐way or two‐way) with Tukey's multiple comparison post‐hoc test where appropriate. A P‐value <0.05 was considered significant.

Chemicals

Sodium azide (NaN3), niflumic acid (NFA) and K2ATP were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). PI(4,5)P2 diC8 (Echelon Biosciences Inc., Salt Lake City, UT) was dissolved in the macropatch intracellular solution and stored in glass vials as a 230 μM stock at −80°C. All working solutions were prepared immediately before use by dilution of stock solutions previously stored at −20°C.

Results

Intracellular ATP has no effect on ISlo2.1 recorded from inside‐out macropatches of oocyte membrane

The effect of ATP applied directly to the intracellular side of inside‐out membrane patches excised from Xenopus oocytes was determined. In most patches, the magnitude of ISlo2.1 decreased rapidly soon after patch excision, complicating analysis of the effects of intracellular ATP. However, the rate of current run‐down was greatly reduced by including 10 μM PI(4,5)P2 diC8 to the solution bathing the inside (cytosolic side) of the membrane patch. Slo2.1 channels can be activated by elevated [NaCl]i delivered via intracellular pipettes in intact oocytes (Garg et al. 2013). However, Slo2.1 channels were not activated in excised inside‐out macropatches when [NaCl]i was elevated from 3 mmol/L to 30 or 300 mmol/L, even in the presence of 10 μM PI(4,5)P2 diC8. Therefore, heterologously expressed Slo2.1 channels were activated by 2 mmol/L NFA in the pipette solution. ISlo2.1 was recorded under voltage clamp in response to repetitive ramping of the transmembrane voltage from +80 to −120 mV (Fig. 1A, inset). Under control conditions, large outward currents were activated almost instantly in response to stepping the voltage from −80 mV to +80 mV, and current magnitude declined as the voltage was ramped to −120 mV, becoming inward at potentials negative to −80 mV (Fig. 1A, black trace). After several voltage ramps were applied, 5 mmol/L K2ATP was added to the intracellular solution and the voltage ramps were continued for another 5 min. There was no difference between the currents recorded in the presence of 5 mmol/L ATP (Fig. 1A, red trace) compared to the control trace. Currents were rapidly and almost fully blocked by addition of 100 μM N‐methyl verapamil (D890) to the intracellular solution (Fig. 1A, blue trace), confirming that the membrane patch was in the inside‐out configuration as the permanently charged D890 only blocks ISlo2.1 when added to the intracellular side of the membrane (Garg et al. 2013). Figure 1B shows currents from the same patch after averaging multiple traces under each condition. The effect of 5 mmol/L K2ATP was determined in a total of 4 patches, and no significant change in ISlo2.1 was detected (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Intracellular ATP does not inhibit ISlo2.1 recorded from inside‐out macropatches of Xenopus oocyte membranes. (A) Representative current traces recorded from excised inside‐out macropatches of oocyte membrane during voltage ramps (upper inset) from +80 to −120 mV. Currents were recorded in the absence (Control, black trace), 5 min after addition of 5 mmol/L K2ATP (red trace), and after addition of 100 μM D890 in the continued presence of K2ATP. Arrow indicates 0 current level. (B) Mean currents from 30 to 35 consecutive sweeps under each condition as indicated. (C) Bar graph comparing normalized peak ISlo2.1 in the absence and presence of 5 mmol/L K2ATP. No statistical difference was observed between the two groups (paired Student's t test; P = 0.13, n = 4).

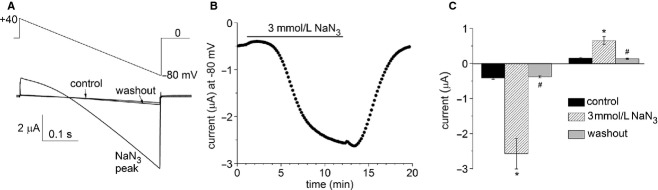

NaN3 activates ATP‐sensitive K+ (KATP) channels, but not Slo2.1 channels

The properties of ISlo2.1 may be altered in excised membrane patches due to stretching of the membrane and exchange of the complex contents of cytoplasm with a simple intracellular salt solution. To determine if changes in [ATP]i under conditions where the membrane is not stretched and the cytoplasmic contents not altered, we used NaN3 to lower [ATP]i in intact oocytes. Extracellular application of NaN3 (3 mmol/L) was previously reported to lower [ATP]i from 4.6 mmol/L to 1.2 mmol/L and activate heterologously expressed KATP channels in Xenopus oocytes (Gribble et al. 1997). We first confirmed the effect of NaN3 on KATP channels. From a holding potential of 0 mV, voltage ramps of 0.4 s duration were applied from +40 to −80 mV once every 10 s. As reported previously (Gribble et al. 1997), extracellular application of 3 mmol/L NaN3 produced a gradual increase in whole cell currents in oocytes co‐injected with Kir6.2 and SUR1 cRNAs (Fig. 2A). IKATP started to activate within 3–5 min after NaN3 application, reached a steady state level after about 10 min and was completely reversible upon washout (Fig. 2A and B). There was an initial transient increase in current level after NaN3 removal which could result from relief of direct azide‐induced block of IKATP (Gribble et al. 1997). NaN3 did not increase currents during the voltage ramps in oocytes not injected with Kir6.2 and SUR1 cRNAs (not shown). Figure 2C compares the average current amplitudes for 10 oocytes recorded at the start (+40 mV) and end (−80 mV) of the voltage ramps before, and after treatment with 3 mmol/L NaN3.

Figure 2.

NaN3 activates KATP channels heterologously expressed in Xenopus oocytes. (A) Voltage ramp protocol (upper panel) used to elicit whole‐cell currents (lower panel) measured by TEVC. Currents were recorded under control conditions, after 10 min exposure to 3 mmol/L NaN3 and after washout of NaN3. Arrow indicates 0 current level. (B) Time‐dependent changes in the inward current recorded at −80 mV in a single representative oocyte induced by application and subsequent washout of 3 mmol/L NaN3. (C) Bar graphs comparing IKATP measured at −80 and +40 mV during voltage ramps before (control), at peak of NaN3 effect and after washout of NaN3 (n = 10). *P < 0.001 relative to control, #P < 0.001 relative to NaN3‐peak current (one‐way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparison test).

Oocytes injected with low amounts of Slo2.1 cRNA (~1 ng) elicit negligible currents under control conditions. As reported previously (Dai et al. 2010; Garg and Sanguinetti 2012), application of 1 mmol/L NFA to the extracellular solution causes an increase in ISlo2.1 that reaches a peak in about 4 min, followed by a slow decline over 20 min (Fig. 3A, black circles). The EC50 for NFA activation of ISlo2.1 is 2.1 mmol/L (Dai et al. 2010). We purposely used a non‐saturating concentration of NFA (1 mmol/L) for these experiments to allow for a possible further increase in response to lowering [ATP]i. In another group of oocytes, the effect of 3 mmol/L NaN3 (in the continued presence of 1 mmol/L NFA) on ISlo2.1 was determined (Fig. 3A, red circles). After NFA‐mediated activation of ISlo2.1 reached a peak in 4 min, the control recording solution was switched to a solution that contained 3 mmol/L NaN3 plus 1 mmol/L NFA. ISlo2.1 was rapidly inhibited by NaN3 within seconds after its application, and this effect was rapidly reversible upon washout of the NaN3 as the magnitude of NFA‐activated ISlo2.1 was the same at 20–25 min as the control group (Fig. 3A). The rapid inhibition of NFA‐activated Slo2.1 current may result from NaN3 competition with NFA binding to the channel, or from direct physical block of the channel by NaN3.

Figure 3.

NaN3 does not activate Slo2.1 channels heterologously expressed in Xenopus oocytes. (A) Plot of time‐dependent effect of 1 mmol/L NFA (●, n = 3) or 1 mmol/L NFA co‐applied with 3 mmol/L NaN3 (●, n = 4) for 13 min (indicated by red bar) on whole‐cell ISlo2.1 recorded using TEVC from oocytes expressing WT Slo2.1 channels. Currents were recorded during repetitive pulses to 0 mV and normalized relative to the peak current measured in response to NFA (at ~4 min). Oocytes were injected with 1 ng WT Slo2.1 cRNA and studied 2 days later. (B) NaN3 does not enhance currents conducted by constitutively active E275D Slo2.1 channels. Currents recorded during repetitive pulses to 0 mV were normalized relative to the initial current and plotted as a function of time after start of voltage clamp. At 5 min, 3 mmol/L NaN3 was added to the bathing solution for a total of 13 min (indicated by red bar), then washed out (n = 7). Oocytes were injected with 0.3 ng E275D Slo2.1 cRNA and recorded 2 days later.

E275D Slo2.1 channels are constitutively active in the presence of physiological [Na]i and [Cl]i and absence of NFA (Garg et al. 2013). The magnitude of E275D Slo2.1 channel currents can be increased 2.5‐fold by NFA with an EC50 of 192 μM (Garg et al. 2013), indicating that these mutant channels are not fully activated under normal physiological conditions. We examined the effects of NaN3 on these channels to address the possibility that activation of WT channels by NFA might somehow prevent inhibition of ISlo2.1 in response to NaN3‐induced reduction in [ATP]i. Extracellular application of 3 mmol/L NaN3 inhibited these mutant channels to a lesser extent than that observed with WT Slo2.1. E275D ISlo2.1 slowly increased with time and application of NaN3 did not alter this time‐course (Fig. 3B). Thus, unlike KATP channels, NaN3 does not activate ISlo2.1, indicating a relative insensitivity of Slo2.1 to a decrease in [ATP]i.

Mutation of putative ATP binding site does not alter NFA‐activated ISlo2.1

Slo2.1 contains a consensus ATP binding motif (GPKHSGKT) in the C‐terminus of the channel. Mutation of the first Gly to a Ser in this motif was reported to prevent ATP from inhibiting Slo2.1 channel currents (Bhattacharjee et al. 2003). We mutated the highly conserved second Lys of this motif to Ala (K1031A). If as previously proposed, ATP inhibits ISlo2.1 by binding to this putative binding site, then mutant channels harboring a disrupted motif would be expected to have larger currents than WT channels under similar conditions. We tested this prediction by comparing the magnitude of 1 mmol/L NFA‐activated ISlo2.1 conducted by WT and K1031A Slo2.1 channels in whole oocytes. Oocytes from a single isolation were injected with 1 ng of WT or K1031A Slo2.1 cRNA and recorded after 2 days of incubation to achieve comparable levels of expression (Fig. 4A). The I‐V relationships for both currents recorded in the absence and presence of 1 mmol/L NFA are plotted in Fig. 4B. In the absence of NFA, WT and K1031A Slo2.1 channel currents were undetectable and only very small endogenous oocyte currents were measurable (0.47 ±0.03 μA at +80 mV). NFA application provoked a marked and similar increase of current magnitude at all potentials examined between −130 and +80 mV in oocytes expressing WT or K1031 Slo2.1 channels (Fig. 4B). These findings suggest that the putative ATP binding site in the C‐terminus of Slo2.1 is non‐functional.

Figure 4.

ATP does not inhibit NFA‐activated Slo2.1 channels heterologously expressed in Xenopus oocytes. (A) NFA activates WT and K1031A Slo2.1 channel currents measured by TEVC. Under control conditions, only endogenous oocyte currents were measurable. After addition of 1 mmol/L NFA, ISlo2.1 was activated to a similar extent in oocytes expressing either WT Slo2.1 channel (left panel) or K1031A mutant Slo2.1 channels (right panel). Upper inset depicts voltage‐clamp protocol. (B) Average I–V relationships for WT (□,■) and K1031A (●,○) ISlo2.1 recorded before and after treatment with 1 mmol/L NFA (n = 17 for each channel type). Oocytes were recorded after 2 days of injection with 1 ng WT or K1031A Slo2.1 cRNA. NFA‐activated currents were larger than control currents (P < 0.001; two‐way ANOVA), but not different between WT and K1031A oocytes.

Discussion

Due to conflicting reports in the literature, we re‐examined the effects of intracellular ATP on human Slo2.1 K+ channels heterologously expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Previously, Bhattacharjee et al. (2003) reported that intracellular ATP at a concentration of 5 mmol/L caused >80% inhibition of heterologously expressed human Slo2.1 channels, whereas Berg et al. (2007) reported no inhibition by intracellular ATP of native KNa channels or cloned human Slo2.1 channels. Specifically, neither constitutively expressed Cl−‐activated K+ currents in striatal interneurons, nor human Slo2.1 heterologously expressed in HEK293T cells measured using the whole cell voltage clamp were inhibited by 3 mmol/L intracellular ATP (Berg et al. 2007). In the present study, we found that application of 5 mmol/L K2ATP to the cytosolic side of excised inside‐out macropatches did not inhibit ISlo2.1, and that mutation of a consensus ATP binding motif did not enhance ISlo2.1. Unlike the previous studies, we included 10 μM PIP2 in the cytosolic solution to prevent run‐down of current and used NFA in most experiments to activate Slo2.1. It is possible that these compounds may have affected the response of Slo2.1 channels to ATP in excised inside‐out patch recordings. To control for this possibility, we showed that lowering [ATP]i with NaN3 also did not enhance E275D channel currents. Although these mutant channels are constitutively active, they can be further activated by NFA or elevated [NaCl]i (Garg et al. 2013). Overall, our findings are in agreement with Berg et al. (2007) that intracellular ATP does not inhibit heterologously expressed human Slo2.1 channels.

We performed experiments to determine if lowering [ATP]i by treatment of intact oocytes with NaN3 might enhance Slo2.1 channel activity. ISlo2.1 was recorded from whole oocytes before and after treating oocytes with the metabolic inhibitor, NaN3 that inhibits cytochrome C oxidase in the mitochondrial electron transport chain and causes depletion of intracellular ATP (Trapp and Ashcroft 2000). At physiological pH, NaN3 is almost completely dissociated in solution and azide ions (![]() ) combine with extracellular protons to form HN3, a weak acid that can penetrate the plasma membrane (Trapp and Ashcroft 2000). In Xenopus oocytes, 10 min exposure to 3 mmol/L NaN3 reduced the [ATP]i from 4.6 ± 0.3 mmol/L to 1.2 ± 0.1 mmol/L (Gribble et al. 2000). We confirmed that treatment of oocytes with 3 mmol/L NaN3 for 13 min activated heterologously expressed KATP (Kir6.2/SUR1) channels, but found that the same treatment did not activate either constitutively active E275D Slo2.1 channels or WT Slo2.1 channels partially activated by NFA.

) combine with extracellular protons to form HN3, a weak acid that can penetrate the plasma membrane (Trapp and Ashcroft 2000). In Xenopus oocytes, 10 min exposure to 3 mmol/L NaN3 reduced the [ATP]i from 4.6 ± 0.3 mmol/L to 1.2 ± 0.1 mmol/L (Gribble et al. 2000). We confirmed that treatment of oocytes with 3 mmol/L NaN3 for 13 min activated heterologously expressed KATP (Kir6.2/SUR1) channels, but found that the same treatment did not activate either constitutively active E275D Slo2.1 channels or WT Slo2.1 channels partially activated by NFA.

Slo2.1 contains a consensus ATP binding site (1025‐GPKHSGKT‐1032) that is located distal to the second RCK domain in the C‐terminal. The sequence GXXXXGKT, known as Walker motif A (W‐motif) has been shown to bind nucleotides in a wide variety of proteins [e.g. α‐ and β‐subunits of F1‐ATPase, myosin and other ATP‐requiring enzymes (Walker et al. 1982)]. The W‐motif forms a loop around the nucleotide and the highly conserved Lys and Thr residues bind the phosphate group of ATP. An analysis of the crystal structure of 92 proteins that have a W‐motif revealed that in about half of these proteins, the motif did not form a loop or did not bind ATP (Ramakrishnan et al. 2002). Our finding that K1031A Slo2.1 channel currents were of the same magnitude as WT Slo2.1 channel currents indicates that the W‐motif is nonfunctional in Slo2.1.

Together our findings indicate that intracellular ATP does not inhibit human Slo2.1 channels heterologously expressed in Xenopus oocytes, consistent with the lack of effect of ATP on these channels when heterologously expressed in HEK293T cells (Berg et al. 2007). This finding implies that during ischemia it is the elevation of [Na+]i and [Cl‐]i, but not the reduction of [ATP]i that causes activation of Slo2.1 K+ channels.

Acknowledgments

The expert technical support of Alison Gardner is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Footnotes

Funding Information

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Heart Lung and Blood Institute [Grant R01HL103877] and from the Nora Eccles Treadwell Foundation.

References

- Bader C. R., Bernheim L., Bertrand D. 1985. Sodium‐activated potassium current in cultured avian neurones. Nature; 317:540-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg A. P., Sen N., Bayliss D. A. 2007. TrpC3/C7 and Slo2.1 are molecular targets for metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling in rat striatal cholinergic interneurons. J. Neurosci.; 27:8845-8856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee A., Kaczmarek L. K. 2005. For K+ channels, Na+ is the new Ca2+. Trends Neurosci.; 28:422-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee A., Joiner W. J., Wu M., Yang Y., Sigworth F. J., Kaczmarek L. K. 2003. Slick (Slo2.1), a rapidly‐gating sodium‐activated potassium channel inhibited by ATP. J. Neurosci.; 23:11681-11691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budelli G., Hage T. A., Wei A., Rojas P., Jong Y. J., O'malley K. 2009. Na+‐activated K+ channels express a large delayed outward current in neurons during normal physiology. Nat. Neurosci.; 12:745-750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai L., Garg V., Sanguinetti M. C. 2010. Activation of Slo2.1 channels by niflumic acid. J. Gen. Physiol.; 135:275-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg P., Sanguinetti M. C. 2012. Structure‐activity relationship of fenamates as Slo2.1 channel activators. Mol. Pharmacol.; 82:795-802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg P., Gardner A., Garg V., Sanguinetti M. C. 2013. Structural basis of ion permeation gating in Slo2.1 K+ channels. J. Gen. Physiol.; 142:523-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin A. L. 1991. Expression of ion channels by injection of mRNA into Xenopus oocytes. Methods Cell Biol.; 36:487-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble F. M., Ashfield R., Ammala C., Ashcroft F. M. 1997. Properties of cloned ATP‐sensitive K+ currents expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J. Physiol.; 498:87-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble F. M., Loussouarn G., Tucker S. J., Zhao C., Nichols C. G., Ashcroft F. M. 2000. A novel method for measurement of submembrane ATP concentration. J. Biol. Chem.; 275:30046-30049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haimann C., Bernheim L., Bertrand D., Bader C. R. 1990. Potassium current activated by intracellular sodium in quail trigeminal ganglion neurons. J. Gen. Physiol.; 95:961-979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill O. P., Marty A., Neher E., Sakmann B., Sigworth F. J. 1981. Improved patch‐clamp techniques for high‐resolution current recording from cells and cell‐free membrane patches. Pflugers Arch.; 391:85-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek L. K. 2013. Slack, Slick, and Sodium‐Activated Potassium Channels. ISRN Neurosci.; 2013:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameyama M., Kakei M., Sato R. 1984. Intracellular Na+ activates a K+ channel in mammalian cardiac cells. Nature; 309:354-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Los Angeles Tejada M., Stolpe K., Meinild A. K., Klaerke D. A. 2012. Clofilium inhibits Slick and Slack potassium channels. Biologics; 6:465-470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulais M., Lachheb S., Teulon J. 2006. A Na+‐ and Cl‐ ‐activated K+ channel in the thick ascending limb of mouse kidney. J. Gen. Physiol.; 127:205-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan C., Dani V. S., Ramasarma T. 2002. A conformational analysis of Walker motif A [GXXXXGKT(S)] in nucleotide‐binding and other proteins. Protein Eng.; 15:783-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreibmayer W., Lester H. A., Dascal N. 1994. Voltage clamping of Xenopus laevis oocytes utilizing agarose‐cushion electrodes. Pflugers Arch.; 426:453-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuhmer W. 1992. Electrophysiological recording from Xenopus oocytes. Methods Enzymol.; 207:319-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapp S., Ashcroft F. M. 2000. Direct interaction of Na‐azide with the KATP channel. Br. J. Pharmacol.; 131:1105-1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker J. E., Saraste M., Runswick M. J., Gay N. J. 1982. Distantly related sequences in the alpha‐ and beta‐subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP‐requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J.; 1:945-951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan A., Santi C. M., Wei A., Wang Z. W., Pollak K., Nonet M. 2003. The sodium‐activated potassium channel is encoded by a member of the Slo gene family. Neuron; 37:765-773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]