Abstract

Background

Despite improved survival with chemotherapy for stage III colorectal cancer (CRC), patients may suffer substantial economic hardship during treatment. Methods for quantifying financial burden in CRC patients are lacking.

Objective

To derive and validate a novel patient-reported measure of personal financial burden during CRC treatment.

Data Collection

Within a population-based survey of patients in the Detroit and Georgia Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results regions diagnosed with stage III CRC between 2011 and 2013, we asked 7 binary questions assessing effects of disease and treatment on personal finances.

Data Analysis

We used factor analysis to compute a composite measure of financial burden. We used χ2 tests to evaluate relationships between individual components of financial burden and chemotherapy use with χ2 analyses. We used Mantel-Haenszel χ2 trend tests to examine relationships between the composite financial burden metric and chemotherapy use.

Results

Among 956 patient surveys (66% response rate), factor analysis of 7 burden items yielded a single-factor solution. Factor loadings of 6 items were >0.4; these were included in the composite score. Internal consistency was high (Cronbach α = 0.79). The mean financial burden score among all respondents was 1.72 (range, 0–6). The 812 (85%) who reported chemotherapy use had significantly higher financial burden scores than those who did not (mean burden score 1.88 vs. 0.88, P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Financial burden is high among CRC patients, particularly those who use adjuvant chemotherapy. We encourage use of our instrument to validate our measure in the identification of patients in need of additional financial support during treatment.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, chemotherapy, financial burden, finances, factor analysis

Thirty-five percent of colorectal cancer (CRC) patients are diagnosed with stage III disease.1 Adjuvant 5-FU-based chemotherapy improves survival, and has become standard treatment.2 Unfortunately, chemotherapy use may be associated with financial hardship.3–8 Patients may even choose to forego recommended cancer care because of prohibitively high costs.9,10 To help ensure that patients receive all recommended care, clinicians and policymakers should understand the extent of financial burden associated with chemotherapy use and identify patients at risk for substantial financial burden.

The primary aim of our study was to derive and validate a new patient-reported measure of personal financial burden in a large, population-based sample of geographically, economically, and racially diverse patients with stage III CRC. We then used the measure to evaluate the association of chemotherapy use and personal financial burden among these patients.

METHODS

Study Population

We identified all patients 21 years and older with pathologic stage III colon or rectal cancer reported to the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results cancer registries of tricounty metropolitan Detroit and the State of Georgia between August 2011 and March 2013. Patients were eligible for study recruitment within 3–12 months following surgical resection of CRC. Exclusion criteria included stage IV disease, change in diagnosis based on final histology, death before survey deployment, or residence outside the catchment area.

Data Collection

We notified physicians of our intention to contact study subjects. After a brief response period, subjects were invited to participate in the survey. A modified Dillman approach was used for recruitment.11 Upon receipt of surveys, extensive data checks for logic, errors and omissions were performed and patients were contacted as necessary to obtain missing information.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Michigan, Wayne State University, Emory University, the State of Michigan, and the State of Georgia Department of Public Health.

Measures

The primary outcome in this study was personal financial burden, assessed by a series of 7 binary questions asking patients how CRC or its treatment affected their finances (Table 1). These measures were adapted from the National Consumer Bankruptcy Project12 and have been used previously in our work.13,14

TABLE 1.

Survey Items to Assess Financial Burden and Worry

| Burden* | ||||

| We’d like to learn about how your colorectal cancer or treatment have affected your finances. Please check ALL of the responses below that apply. | ||||

| (1) I had to use savings. | ||||

| (2) I had to borrow money or take out a loan. | ||||

| (3) I could not make payments on credit cards or other bills. | ||||

| (4) I cut down on spending for food and/or clothes. | ||||

| (5) I cut down on spending for health care for other family members. | ||||

| (6) I cut down on recreational activities. | ||||

| (7) I cut down on expenses in general. | ||||

| Worry† | ||||

| How much do you worry about financial problems that have resulted from your colorectal cancer and its treatment? | ||||

| 1 Not at all | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 Very much |

After factor analysis, the item “I cut down on spending for health care for other family members” was omitted from the composite measure of financial burden, resulting in a 6-item measure with a score range of 0–6 (higher scores denote increased financial burden).

In accordance with our previous work, worry was dichotomized as low (1–3) or high (4–5).

As a secondary aim, we examined the association between personal financial burden and use of adjuvant chemotherapy. Additional covariates included Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results catchment area, self-reported demographics (age at diagnosis, sex, race, and marital status), socioeconomic status (based on measures in the National Health Interview Survey), employment status, health insurance, health status, and comorbidities. Respondents with missing income data were grouped separately for covariate analysis.

Development and Validation of Composite Financial Burden Score

Factor analysis was performed on the financial burden items for all respondents. Using these results, we developed a composite measure of financial burden with a range of 0–6; higher scores denote increased financial burden. The composite measure was internally validated against a binary item on global financial burden (My illness has had no impact on my finances) and a single question about financial worry (How much do you worry about financial problems that have resulted from your colorectal cancer and its treatment). In accordance with our previous work,15 worry was measured using a Likert scale that we dichotomized into “low” and “high” (Table 1).

Statistical Analyses

We used t tests and ANOVA to evaluate associations between financial burden, use of chemotherapy, and other covariates.

Using factor analysis, we initially retained factors with Eigen values of >1.0. We used item loading values >0.4 for the final scale. Finally, we evaluated internal consistency with Cronbach α statistic.

We used the Mantel-Haenszel χ2 trend test to validate the composite financial burden score against the summary financial burden and financial worry items, and to test the relationship between financial burden and chemotherapy use. All statistical tests were 2-sided; P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 (Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Study Sample and Response Rate

Among 1653 eligible patients, 119 (8%) could not be located and 488 (31%) did not return the survey, yielding 956 completed surveys (66% response rate).

Respondent Characteristics and Financial Burden

Relationships between mean financial burden and the demographics, socioeconomic factors, and health status of respondents are displayed in Table 2. After adjustment, mean financial burden was significantly higher in respondents who were younger, uninsured, unemployed, had lower income, or used chemotherapy.

TABLE 2.

Respondent Characteristics and Reported Personal Financial Burden (N = 956)

| Patient Characteristics | N (%) | Financial Burden (Mean ± SE) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEER catchment area | < 0.001 | ||

| Metropolitan Detroit | 324 (34) | 1.91 ± 0.09 | |

| Georgia | 632 (66) | 1.35 ± 0.07 | |

| Use of chemotherapy | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 144 (15) | 0.88 ± 0.12 | |

| Yes | 812 (85) | 1.88 ± 0.06 | |

| Age at diagnosis | < 0.001 | ||

| < 50 | 158 (17) | 2.51 ± 0.16 | |

| 50–64 | 349 (37) | 2.13 ± 0.10 | |

| 65–74 | 219 (23) | 1.41 ± 0.11 | |

| 75+ | 230 (24) | 0.88 ± 0.09 | |

| Sex | 0.385 | ||

| Male | 504 (53) | 1.68 ± 0.08 | |

| Female | 440 (46) | 1.79 ± 0.09 | |

| Race | 0.022 | ||

| White | 678 (71) | 1.63 ± 0.07 | |

| Black | 220 (23) | 1.92 ± 0.13 | |

| Other/unknown | 57 (6) | 2.16 ± 0.26 | |

| Marital status | 0.012 | ||

| Not married/partnered | 382 (40) | 1.54 ± 0.09 | |

| Married/partnered | 574 (60) | 1.85 ± 0.08 | |

| Education | 0.247 | ||

| < High school | 152 (16) | 1.66 ± 0.15 | |

| High school | 231 (25) | 1.85 ± 0.12 | |

| Some college | 308 (33) | 1.83 ± 0.11 | |

| College grad+ | 247 (26) | 1.57 ± 0.11 | |

| Annual income | < 0.001 | ||

| < $20,000 | 165 (22) | 1.70 ± 0.14 | |

| $20,000–$49,000 | 256 (33) | 2.31 ± 0.12 | |

| $50,000–$89,000 | 208 (27) | 1.86 ± 0.13 | |

| ≥$90,000 | 140 (18) | 1.42 ± 0.14 | |

| Missing | 187 (20) | 1.03 ± 0.11 | |

| Health insurance | < 0.001 | ||

| Medicare | 357 (38) | 1.28 ± 0.09 | |

| Medicaid | 32 (3) | 1.44 ± 0.31 | |

| None | 81 (9) | 2.67 ± 0.22 | |

| Other | 163 (17) | 1.84 ± 0.14 | |

| Employer provided | 313 (33) | 2.00 ± 0.10 | |

| Overall health | 0.488 | ||

| Poor | 61 (7) | 1.72 ± 0.22 | |

| Fair | 131 (14) | 1.96 ± 0.17 | |

| Good | 337 (36) | 1.77 ± 0.10 | |

| Very good | 274 (30) | 1.68 ± 0.11 | |

| Excellent | 134 (14) | 1.57 ± 0.15 | |

| Comorbid conditions | 0.212 | ||

| None | 238 (25) | 1.91 ± 0.12 | |

| 1 | 294 (31) | 1.66 ± 0.10 | |

| ≥2 | 424 (44) | 1.67 ± 0.09 | |

| Employment status | < 0.001 | ||

| Employed | 236 (26) | 1.81 ± 0.11 | |

| Unemployed | 42 (5) | 2.57 ± 0.28 | |

| Disabled | 176 (19) | 2.79 ± 0.07 | |

| Retired | 409 (44) | 1.18 ± 0.24 | |

| Homemaker | 62 (7) | 1.61 ± 0.16 |

Data shown are N (%).

P values are derived from t tests for groups of 2 and from ANOVA for groups of >2. Proportions may not add to 100% because of rounding or missing data.

SEER indicates Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results.

Composite Financial Burden Scores

The mean financial burden score was 1.72 (SD = 1.83). The range was 0–6, and 366 (38%) respondents endorsed no measures of financial burden. A total of 277 (29%) reported 1–2 measures; 223 (23%) reported 3–4; 90 (9%) reported ≥5.

Item Characteristics

Characteristics of financial burden items are described in Table 3. The most frequently endorsed measure was “I cut down on expenses in general,” (48%). The least frequently endorsed was “I cut down on spending for health care for other family members” (5%). Inter-item correlations varied between 0.14 and 0.61.

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of Personal Financial Burden Items From Exploratory Factor Analysis

| Items | Frequency Endorsed by Respondents [N (%)] | Corrected Item–Total Correlation | Loading Value | Cronbach α (if Item Deleted)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) I had to use savings | 310 (34) | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.78 |

| (2) I had to borrow money or take out a loan | 124 (13) | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.78 |

| (3) I could not make payments on credit cards | 124 (13) | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.77 |

| (4) I cut down on spending for food/clothes | 286 (30) | 0.66 | 0.79 | 0.73 |

| (5) I cut down spending for health care for others | 50 (5) | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.79 |

| (6) I cut down on recreational activities | 336 (35) | 0.63 | 0.77 | 0.74 |

| (7) I cut down on expenses in general | 461 (48) | 0.59 | 0.72 | 0.75 |

Cronbach α statistic = 0.79 for the scale.

Exploratory Factor Analysis

The principal factor analysis of the financial burden items suggested 1 underlying factor with Eigen value = 4.31 (Eigen value second factor = 0.62). Factor loadings varied between 0.38 and 0.79. The items demonstrated good internal consistency; Cronbach α = 0.79.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The items referred to as “burden items” represent inherently different types of financial hardship. Nondiscretionary spending is assessed by the items “I had to use savings,” “I had to borrow money or take out a loan,” and “I could not make payments on credit cards or other bills.” Loading values for these items were similar (0.72–0.79). Discretionary spending is assessed by the items “I cut down on recreational activities,” “I cut down on spending for food and/or clothes,” and “I cut down on expenses in general.” While spending on food/clothing could represent discretionary or nondiscretionary spending, depending on context, that item grouped with the discretionary items in the factor analysis (loading values 0.45–0.50). The item “I cut down on spending for health care for other family members,” had a loading value <0.4 (0.38) and was endorsed by only 5% of respondents. We omitted this item from the composite measure, without significant change in Cronbach α.

We considered a 2-factor structure including a composite variable of the 3 discretionary items and a composite variable of the 3 nondiscretionary items. However, confirmatory factor analysis did not support an improved scale with these composite variables and thus our final financial burden score was computed by summing responses to 6 burden items. This scale had an Eigen value = 4.06 suggesting 1 factor (Eigen value second factor = 0.39). Factor loadings ranged from 0.44 to 0.79. The items demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.79).

Internal Validation

Thirty percent of respondents endorsed the item “My illness has had no impact on my finances.” Of these, 94% did not endorse any financial burden items (composite burden score = 0). Similarly, among 562 respondents (60%) who reported low levels of financial worry, 54% had a composite financial burden score of 0.

In general, constructs of worry and financial burden were closely associated: 70% of respondents had concordant worry and burden scores (Pearson Correlation Coefficient = 0.625, P < 0.001). Four percent had low worry but high burden score (3–6) and 26% had high worry but low burden score (0–2).

Financial Burden and Chemotherapy Use

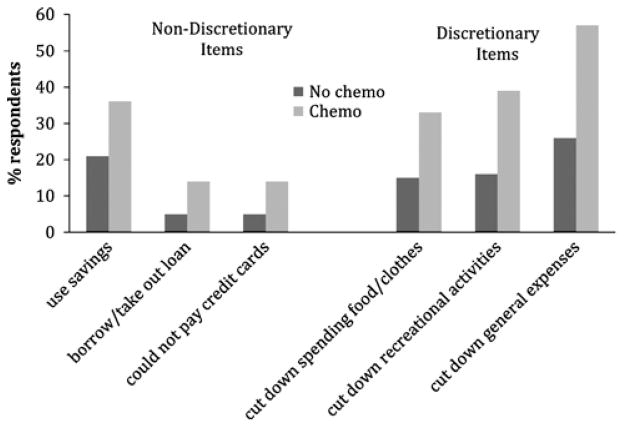

Associations between individual measures of financial burden and chemotherapy use are shown in Figure 1. When compared with patients who did not use adjuvant chemotherapy, patients who used chemotherapy were more likely to use savings (36% vs. 21%; P < 0.001), borrow money or take out a loan (14% vs. 5%; P = 0.002), miss credit card payments (14% vs. 5%; P = 0.002), cut down on spending for food/clothes (33% vs. 15%; P < 0.001), cut down on recreational activities (39% vs. 16%; P < 0.001), or reduce general expenses (57% vs. 26%; P < 0.01).

FIGURE 1.

Patient report of individual personal financial burden items, by chemotherapy use. Those using chemotherapy were significantly more likely to endorse each item of financial burden (all P < 0.01).

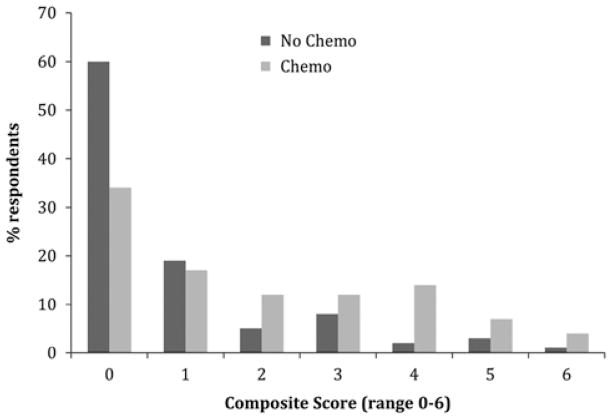

The mean financial burden score for patients using adjuvant chemotherapy was 1.9 versus 0.9 for those patients who did not use chemotherapy (P < 0.001). The distribution of composite financial burden score by chemotherapy use is presented in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of personal financial burden scores, by chemotherapy use. Those using chemotherapy had significantly higher scores and were less likely to report none of the items of personal financial burden (P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

An estimated 137,000 Americans will be diagnosed with CRC in 2014; approximately half of these will receive chemotherapy. Although use of chemotherapy is associated with financial hardship, metrics to screen for financial burden are lacking. In our study of geographically, economically, and racially diverse patients with stage III CRC, we aimed to develop and describe a tool based on patient-reported data regarding the personal financial burden patients experience with use of chemotherapy. This tool can be used to identify patients at risk for financial burden and inform policy interventions to support these patients through cancer treatment. We found substantial financial burden among most respondents, with significantly higher burden reported by those who used chemotherapy.

Consistent with prior studies,3,4 younger respondents reported greater burden than older respondents. Because younger patients remain in the workforce during their cancer treatment, they may face lost wages and opportunity costs.16–18 One fourth of respondents aged less than 50 and 14% of respondents age 50–64 reported that they were working at the time of CRC diagnosis, but were disabled when they completed the survey. Respondents with an annual household income of $20,000–$49,000 (roughly 100%–200% of the 2014 national poverty threshold) reported the highest levels of financial burden. These findings suggest that the young, working poor are a particularly vulnerable patient group. Policy changes to job support measures, such as mandatory paid sick leave and disability benefits, may help support such patients during CRC treatment.

There were several subgroups of respondents who reported high levels of worry about finances despite lower reported composite personal financial burden scores. These respondents tended to be racial minorities and have an annual household income <$20,000. Our burden score may lack sensitivity to the socioeconomic hardships of these individuals who may not have personal savings, available credit, or discretionary spending to reduce in times of illness. Individuals with fewer means of compensating for financial losses may find some of the response items immaterial. Given that one quarter of our respondents reported an annual household income <$20,000 and nearly 40% of US workers earned <$20,000 in 2012,19 this could potentially affect a large population of CRC patients. Alternate measures of financial burden should be explored in this population.

Composite financial burden was particularly high among respondents in our study who used chemotherapy. These respondents were significantly more likely to endorse each individual financial burden item, compared with those who did not use chemotherapy. Nonadherence with recommended medications, including chemotherapy, and omission of essential medical care has been attributed to financial burden among cancer patients.20,21 Emotional distress and dissatisfaction with care also stem from financial burden,22,23 and all contribute to reduced quality of life.24 Policy interventions to support patients receiving chemotherapy could include subsidies from pharmaceutical companies to offset copays or funds from hospitals and cancer centers to defray patient costs for parking and transportation.

Although our survey respondents included only patients with resected stage III CRC, the population-based nature of our study and the broad geographic and economic representation ensure that our findings can be applied to the general population of CRC patients and perhaps patients with other cancers as well. Although our results may reflect nonresponse bias, our response rate of 66% compares quite favorably to the response rates of other large, mailed surveys of CRC patients. There may be other dimensions to personal financial burden that our measure does not assess. However, our burden items are adapted from the well-known National Consumer Bankruptcy Project. Finally, a subjective measure of patient financial burden may be more difficult to interpret across studies than a dollar value such as out-of-pocket cost, however, dollar values may not convey the personal burden experienced by individuals. We would welcome future studies investigating the association between out-of-pocket costs and patient-reported financial burden.

In conclusion, we have developed a novel patient-reported measure of personal financial burden among a population-based sample of patients with stage III CRC. We present a 1-factor measure of personal financial burden, which may be a valuable tool to identify patients at risk for increased burden. The greatest burden was endorsed by the younger working poor and by those respondents who used chemotherapy. These vulnerable patient groups may benefit from policy interventions to provide economic support as they undergo potentially life-saving cancer treatment.

Acknowledgments

A.M.M. and the study are supported by a generous Grant from the American Cancer Society, Atlanta, GA (Research Scholar Grant #11-097-01-CPHPS). The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the American Cancer Society.

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge the assistance and support of Ashley Gay, BA and Paul Abrahamse, MA.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.SEER Cancer Statistics Factsheets: Colon and Rectum Cancer. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: [Accessed May 2, 2014]. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/htmlcolorect.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andre T, Boni C, Navarro M, et al. Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3109–3116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shankaran V, Jolly S, Blough D, et al. Risk factors for financial hardship in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer: a population-based exploratory analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1608–1614. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.9511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18:381–390. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meropol NJ, Schulman KA. Cost of cancer care: issues and implications. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:180–186. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langa KM, Fendrick AM, Chernew ME, et al. Out-of-pocket healthcare expenditures among older Americans with cancer. Value Health. 2004;7:186–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2004.72334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arozullah AM, Calhoun EA, Wolf M, et al. The financial burden of cancer: estimates from a study of insured women with breast cancer. J Support Oncol. 2004;2:271–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banegas MP, Yabroff KR. Out of pocket, out of sight? An unmeasured component of the burden of cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:252–253. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1143–1152. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Markman M, Luce R. Impact of the cost of cancer treatment: an internet-based survey. J Oncol Pract. 2010;6:69–73. doi: 10.1200/JOP.091074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM, et al. Internet, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. 3. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawless RM, Littwin AK, Porter KM, et al. Did bankruptcy reform fail? An empirical study of consumer debtors. Am Bankr L J. 2008;82:349–405. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Regenbogen SE, Veenstra CM, Hawley ST, et al. The personal financial burden of complications after colorectal cancer surgery. Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1002/cncr.28812. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mujahid MS, Janz NK, Hawley ST, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in job loss for women with breast cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:102–111. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0152-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Regenbogen SE, Veenstra CM, Hawley ST, et al. The effect of complications on the patient-surgeon relationship after colorectal cancer surgery. Surgery. 2014;155:841–850. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chirikos TN, Russell-Jacobs A, Cantor AB. Indirect economic effects of long-term breast cancer survival. Cancer Pract. 2002;10:248–255. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.105004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yabroff KR, Warren JL, Knopf K, et al. Estimating patient time costs associated with colorectal cancer care. Med Care. 2005;43:640–648. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000167177.45020.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finkelstein EA, Tangka FK, Trogdon JG, et al. The personal financial burden of cancer for the working-aged population. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:801–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. [Accessed May 2, 2014];The National Average Wage Index (AWI): Wage statistics for 2012. Available at: http://www.ssa.gov/cgi-bin/netcomp.cgi?year=2012.

- 20.Kelley RK, Venook AP. Nonadherence to imatinib during an economic downturn. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:596–598. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1004656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Yabroff KR, et al. Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care? Cancer. 2013;119:3710–3717. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chino F, Peppercorn J, Taylor DH, Jr, et al. Self-reported financial burden and satisfaction with care among patients with cancer. Oncologist. 2014;19:414–420. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allen J, Zebrack B, Wittmann D, et al. Expanding the NCCN guidelines for distress management: a model of barriers to the use of coping resources. J Community Support Oncol. 2014;12:271–277. doi: 10.12788/jcso.0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta D, Lis CG, Grutsch JF. Perceived cancer-related financial difficulty: implications for patient satisfaction with quality of life in advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:1051–1056. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]