Abstract

As bystander approaches become increasingly prevalent elements of sexual and domestic violence prevention efforts, it is necessary to better understand the factors that support or impede individuals in taking positive action in the face of aggressive or disrespectful behavior from others. This study presents descriptive findings about the bystander experiences of 27 men who recently became involved in antiviolence against women work. More specifically, we describe the consistency with which respondents actively intervene in the speech or behavior of others, the strategies they use, and the factors they weigh as they deliberate taking action. Respondents report a complex and interrelated set of individual and contextual influences on their choices within bystander opportunities, which hold implications for both violence-specific models of bystander behavior and for prevention intervention development.

Keywords: bystander, engaging men, sexual assault, domestic violence, prevention

Primary prevention efforts to reduce sexual and intimate partner violence have increasingly moved toward incorporating “bystander” components in educational programming. Rooted in a desire to engage community members in helping to recognize and prevent possible assaults, bystander approaches educate individuals about violence and encourage them to speak up in the face of aggressive, coercive, or disrespectful conduct (Banyard, Plante, & Moynihan, 2004; McMahon, 2010). This approach has garnered considerable excitement because of its potential to provide all community members with a positive, tangible role to play in reducing violence as well as its capacity to fundamentally shift violence-related social norms as more people take a vocal stance against exploitive or misogynistic behavior (Banyard et al., 2004). Accordingly, evaluations of the bystander approach to sexual and intimate partner violence prevention have been supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and highlighted as an important new direction in prevention intervention (CDC, 2010).

Although bystander prevention programs target both men and women as possible helpers, this approach is a core element of efforts aimed at engaging men as allies in ending violence against women (see, for example, Foubert, 2000; Katz, 1995). Central to men's engagement programs is the notion that men may be particularly effective in challenging violence-supportive behavior or speech among their male peers (Flood, 2005). This is predicated on findings that men disproportionately perpetrate sexual and intimate partner violence (Tjaden & Thoennes, 1998), that violence may be tacitly reinforced in some male peer cultures characterized by violence-supportive norms and beliefs (Humphrey & Kahn, 2000), and that men may be more swayed by male peer messengers (Earle, 1996). Male bystanders may therefore have greater access to and influence over the norms and behaviors of their peers and, concomitantly, have a critical role to play as “allies” in reducing violence against women. This study aims to augment knowledge about men's roles as positive bystanders by describing how 27 male antiviolence allies talk about their own bystander experiences and about the barriers and dynamics that shape their responses in the face of problematic behavior from other men.

Bystander Components in Current Violence Prevention Initiatives

As a relatively new addition to sexual and intimate partner violence prevention, few bystander programs have yet been rigorously evaluated. “Bringing in the Bystander,” Banyard, Moynihan, and Plante (2007), is one of the few tested bystander-specific prevention programs. This theory-based intervention involves a one-to-three-session curriculum that educates undergraduates about sexual violence, describes warning signs of a potential assault, and supports skill building related to appropriately intervening in a situation or behavior that could lead to an assault or that is disrespectful to women. An experimental evaluation of the program found positive effects for both men and women on rape-related knowledge and attitudes as well as on positive bystander attitudes and behavior at a 2-month follow-up (Banyard et al., 2007). Other prevention initiatives with bystander components include “The Men's Program,” (Foubert, 2000), the Mentors in Violence Prevention (MVP) program (Katz, 1995), and Men Can Stop Rape's “Men of Strength” (MOST) clubs (www.mencanstoprape.org). Nonexperimental evaluations of these three programs suggest that participants report increased confidence and intention to intervene in disrespectful peer behavior (see, respectively, Foubert & Perry, 2007; Ward, 2005; Hawkins, 2005).

Theories of Bystander Behavior

These bystander intervention programs are informed by 40 years of social psychological research on the conditions under which bystanders intervene in emergency or problem situations. Although a thorough review of this extensive literature is beyond the scope of this article, findings particularly relevant to violence prevention are summarized here. The most prominent and enduring bystander framework comes from the work of Latané and Darley (1969), who proposed a 5-stage model of the processes bystanders must traverse before taking action. These stages include noticing the troubling situation, interpreting it as problematic, assuming personal responsibility for addressing the problem, identifying an accessible course of action, and then implementing that action. Progress toward action at all of these stages may be hindered by the presence of others (known as the “bystander effect”). Passive others may decrease the likelihood that a situation is viewed as a crisis, may reduce responsibility felt by any single individual to help, and may increase the potential costs of taking action (such as through raising concerns about appearing foolish; Latané & Darley, 1969; Latané & Nida, 1981). Support for elements of this model have been demonstrated across a variety of emergency and rule-breaking situations (see, for review, Latané & Nida, 1981), including child abuse (Christy & Voight, 1994) and vandalism (Chekroun & Brauer, 2002).

Recent research suggests that Latané and Darley's 5-stage model and bystander effect construct may be relevant to intervening in situations that could lead to sexual or dating violence. In a cross-sectional investigation of situational barriers to intervening in a possible sexual assault, Burn (2009) found that for men, difficulty in identifying high-risk situations, in taking responsibility in those situations, and/or in knowing what to do were all negatively correlated with self-reported willingness to take action. Fearing what others might think was also inversely associated with likelihood of intervening (Burn, 2009). Similarly, Weisz and Black (2008) found that in speculating about how they might respond to a vignette of a male friend who was abusing his partner, adolescents cited many of the factors highlighted by the 5-stage model. These included believing that it was not their business (responsibility) to intervene or that they were unsure whether it was serious enough to step forward and get involved.

Several other factors may be related to intervening behavior. For example, individuals may be more inclined to intervene when they feel a common social identity with other present bystanders or with the victim—a dynamic which may counteract the “bystander effect” (Levine & Crowther, 2008). Relative to intimate violence, this notion is supported by findings that athletes with a high degree of team bondedness report a willingness to challenge teammates on abusive behavior (McMahon & Farmer, 2009) and that both men and women are more likely to intervene on behalf of a friend than a stranger in a potential assault situation (Burn, 2009). Similarly, several researchers have found that self-reported willingness to intervene with an abusive or disrespectful male friend is highly related to men's perceptions of their male peers’ willingness to do the same (Brown & Messman-Moore, 2010; Fabiano, Perkins, Berkowitz, Linkenbach, & Stark, 2003). Bystanders may also engage in a cost-benefit analysis of intervening (Piliavin, Dovidio, Gaertner, & Clark, 1981). When the costs of taking no action supersede the potential costs of stepping forward, direct or indirect helping becomes more likely (see, for review, Fritzsche, Finkelstein, & Penner, 2000). Although to our knowledge, this dynamic has not yet been directly explored relative to antiviolence bystanders, understanding men's perceptions of the potential advantages and costs of stepping forward would likely enhance prevention programming.

Gaps in the Literature and Purpose of the Study

In summary, bystander components in sexual and intimate partner violence prevention programs have shown exciting potential to engage community members in taking action and are backed by considerable evidence of the factors that influence bystander behavior. Still, gaps remain in our understanding of the specific experiences of men negotiating violence-related bystander opportunities in the context of their daily lives and relationships. Although the considerable body of social psychological bystander literature points to possible variables that may be relevant to understanding male antiviolence bystander behavior, much of it has focused on “emergency” situations in which a victim or person in distress is either present or clearly identifiable (see, for review, Latané & Nida, 1981). In contrast, many of the situations in which male allies are encouraged to take a stand involve disrespectful, violence-supportive, or sexist speech or conduct by a male peer—circumstances that may be difficult to interpret and in which there may be no clear, immediate victim. Indeed, prior research has found that greater ambiguity within an emergency situation is associated with reduced likelihood of intervention among bystanders (Latané & Nida, 1981). Another point of departure is that unlike many of the bystander situations studied in the literature in which helping is likely consistent with overt social norms (such as reporting a thief or assisting an injured person), many antiviolence bystander opportunities may involve challenging tacit peer group or masculinity-related norms for speech or behavior (see Schwartz & DeKeseredy, 1997 for a discussion of male peer support for violence). Speaking up in these contexts may be further complicated by men's desire to maintain positive relationships with the peers or family members they are faced with the prospect of challenging. Finally, male allies may face a wide variety of bystander opportunities, ranging from a friend clearly taking advantage of an incapacitated woman to a friend or family member using sexist language. Each of these is likely to present unique intervention considerations. As McMahon (2010) notes, “Research on the factors that facilitate or hinder a bystander's decision to intervene in situations involving sexual assault is in its infancy” (p. 4). Better elucidating the dynamics and circumstances associated with action versus inaction among male antiviolence allies across a variety of situations may foster our ability to engage and support positive male bystanders in an ongoing way.

The purpose of this study is therefore to explore how antiviolence men experience and decode bystander opportunities as well as the factors they consider as they weigh the choice to intervene. To this end, we present descriptive analyses of interviews with 27 men who recently initiated involvement in antiviolence work regarding their experiences and perceptions of “stepping up” in the face of another man's inappropriate violence-relevant behavior or speech. Specifically, we will describe (a) the consistency with which men report intervening in these situations, (b) the kinds of strategies they employ, and (c) the factors and dynamics they identify as relevant to their decisions about taking action. A fourth aim of this article is to examine the degree of salience of extant bystander intervention theory to the specific dynamics reported by male antiviolence bystanders in this sample.

Method

Participant Recruitment

Data for these analyses were drawn from a study of the factors that precipitated antiviolence involvement among newly initiated male allies. Following approval from the human subjects review committee, potential respondents were recruited through several topic-relevant national email list serves, through announcements at relevant practitioner and organizational meetings in the Northwest United States, and through referrals from participants themselves. Respondents contacted the researcher directly and were screened for eligibility. Eligibility criteria included joining an antiviolence against women organization, event, or group within the past 2 years and being a man 18 years or older. Eligible participants were then interviewed in person or over the phone, depending on location.

Sample

Forty-three men contacted the study. Of these, 14 reported long-term anti-violence involvement and 2 did not return consent forms, for a final sample size of 27. Participants ranged in age from 20 to 72 and identified almost exclusively as White—one participant identified as Latino. Therefore, the bystander experiences described here are largely those of White men. Of the 16 men whose length of participation or lack of consent form excluded them from the study, 5 identified as African American, 1 as Latino, and 10 as White. Length of involvement in antiviolence work at the time of the interview ranged from 1 to approximately 24 months, with one participant's interview occurring 30 months after initiation due to a delay in interview scheduling. Participants came from all regions of the United States. Of the 27 respondents, 16 (59%) were involved in a campus-based antiviolence organization, and their activities included organizing educational events, facilitating presentations about sexual and dating violence, and/or working to mobilize other men. The remaining 11 participants (41%) were postcollege-aged men who volunteered or worked for a domestic and/or sexual violence-related program or who belonged to a community-based men's group. These men's roles ranged from doing direct advocacy with survivors of violence to participating in prevention education programs for youth. All participants but one reported receiving several hours of training related to sexual and/or domestic violence, and 20 respondents (74%) recalled that they received specific training (and/or now train others) about being a positive bystander.

Data Collection

Interviews were semistructured, with standard general questions about men's antiviolence involvement, followed by tailored prompts to elicit deeper narratives about their experiences. The interviews ranged from 45 to 90 min in length. In addition to questions designed for the larger study, men were asked to describe a situation in which they were faced with the choice of whether to intervene in another male's problematic behavior, such as sexist comments or conduct that was disrespectful or dangerous to women. Follow-up questions included inquiries about the facilitators and barriers of action in that moment as well as factors that support or hinder taking action for each respondent more generally. Several participants described more than one bystander opportunity or situation. Nine respondents were interviewed in person and the remaining 18 were interviewed by phone. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed. Eight participants requested to review and approve their transcripts prior to their inclusion in data analysis; none made changes to their transcript.

Data Analysis

Transcripts were entered into the qualitative software program Atlas.ti and analyzed using grounded theory techniques (Corbin & Strauss, 1998). Grounded theory encourages close coding of and comparisons across participants’ data to identify conceptual categories, their dimensions, and their interrelationships. Transcripts were first coded by two researchers for general domains pertinent to bystander experiences. Relevant portions of transcripts were then divided so that two researchers had both unique and shared transcripts to review for line by line, open coding (Corbin & Strauss, 1998). Emergent themes identified by the two researchers were examined for broader conceptual categories, with areas of divergence discussed until a consensus was reached regarding major thematic content within the data. This process was replicated to analyze participants’ frequency of intervening in bystander situations, strategies for intervening, and barriers and considerations related to intervening. Two external reviewers then examined the emergent themes and supporting data as a check on analytical trustworthiness.

Results

Frequency of Bystander Intervention

Participants (signified in this text by anonymity-preserving “MAV” numbers) reported a range of consistency in intervening in the problematic speech or behavior of others. Six (22%) reported that they “never” intervene. These men variably indicated not yet feeling comfortable with taking action, believing that intervening was ineffective or “not worth it” or perceiving that they had not encountered intervention opportunities. Two respondents (8%) were categorized as “rarely” intervening. Each of these men talked about general strategies for intervening with others but were unable to identify a specific situation in which they used those strategies. Twelve men (44%) described making the choice to intervene “sometimes.” These participants either specifically described themselves as taking action in some situations and not others or provided examples of times in which they both did and did not intervene. Finally, seven respondents (26%) self-identified as intervening “most or all of the time.” These participants reported nearly always making the choice to take action, and many could provide several specific examples of times when they intervened.

Men across the range of intervention frequency spoke about the difficulty of challenging other people and the upsetting feelings created by having to choose whether to intervene in the moment. A participant who intervenes “sometimes” and had received bystander training noted, “It's a continuing struggle for me. I'm not going to lie. And a lot of it has to do with my own . . . personal insecurities” (MAV24). A similar participant said sadly,

It's still not something I'm proud of. This whole topic is actually probably the area that I'm most disappointed in myself in terms of activism . . . we talk about how [intervening] is one of those basic levels, but just for me and like every day it's the hardest level to do. (MAV28)

One participant who describes himself as taking action most of the time in response to inappropriate behavior simply noted that speaking up is “hard . . . it really is” (MAV1).

Bystander Situations and Strategies

The 19 respondents who reported intervening in troubling behavior at least sometimes provided more in-depth accounts of specific situations in which they intervened and the strategies they employed. Of these, 17 (89%) provided at least one example of intervening in sexist, homophobic, or rape-supportive language among male friends, 4 (21%) described talking with a friend or family member who was mistreating or disrespecting a partner, and 5 (24%) mentioned stepping into an abusive or potentially exploitive interaction between a male and a vulnerable woman. In this latter category, four of the men reported using distraction or separation techniques, including claiming the police had been called or escorting one of the parties out of the situation. One participant reported once physically stepping into an aggressive altercation.

Across situations involving interrupting inappropriate comments or addressing the abusive behavior of a friend, men described using a range of strategies. Most men used multiple approaches and described tailoring their response to the moment and to the individual target. The most common strategy, mentioned by 11 participants (58%), was making a short, brief and immediate statement such as “that's not cool,” “you know that's not appropriate,” or simply “yo, dude” in response to problematic language. The goal of this type of strategy seemed to be curtailing the target's inappropriate behavior in the moment. As one participant noted, “. . . in the more informal way, you might have to do it five times before they'll stop saying it around you, but when they stop saying it around you, they'll probably stop saying it around other people and stop perpetuating that” (MAV30). Ten participants (53%) described using respectful dialogue and/or questions to encourage the target to think more deeply about the meaning of their words or behavior. This strategy involved asking the target to clarify what he meant or why he said what he did as a way to surface the unexamined assumptions, implications, or impact of a statement. A participant who works with youth noted a typical approach, reporting that he often says, “Okay. So I heard you just said this, and I was just curious where you're coming from with that, and where did you learn those things?” (MAV15).

Six participants (32%) used intervention strategies designed to increase empathy or to encourage the target to consider the impact of their behavior on others or on potential victims. Within these conversations were often attempts to personalize the issue by invoking the target's female family members or friends and asking the target to consider the potential impact of his behavior on those close to him. Similarly, five respondents (26%) reported that they use their own reaction or emotion in the intervention. In this strategy, a respondent communicates how he, personally, is affected or offended by the target's behavior, as reflected in one respondent's most frequent response: “I'm just like, ‘hey, you know, really try not to talk like that because it just kind of bothers me’” (MAV7). Another five participants noted that they sometimes choose to approach the target at a later time, to allow for a more respectful, in-depth conversation in private.

Finally, three respondents reported capitalizing on the dynamics of stereotypical masculinity within male peer groups and either engaging in verbal “one-upmanship” to disparage or isolate the target or appealing to a peer's desire to “be a better man” or to be more attractive to women by behaving more respectfully. For example, one college-enrolled participant noted that in the fraternity context, he might employ a statement such as, “Dude . . . you're kind of coming across as an asshole . . . some of that carries over not just from us, but to women, and if . . . you're known as an asshole, good luck” (MAV21). At the same time, five respondents (26%) specifically warned against intervention strategies that employ confrontation, condescension, or lecturing, noting that these approaches might raise defensiveness or simply be ineffective.

Factors Influencing Men's Bystander Behavior

The bulk of men's discussion of their bystander experiences centered on the way they perceive those moments and on the dynamics that influence their own behavior. Irrespective of how frequently they intervened, all participants but one shared that they contemplated multiple considerations related to whether and how to respond to problematic behavior. The remaining participant did not identify any past bystander “opportunities” and was unsure what dynamics might be at play should he encounter one.

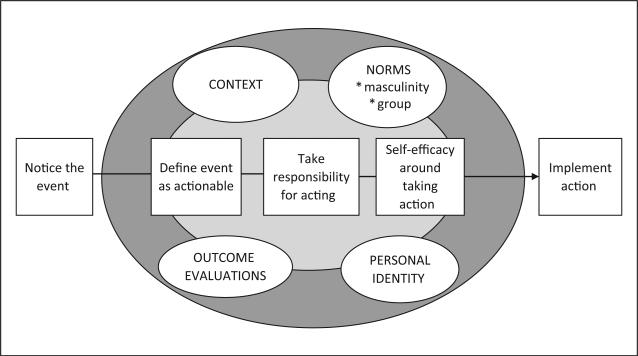

Factors influencing bystander behavior fell into seven main themes and are depicted in Figure 1. All factors described by participants are depicted inside the large circle. Three of these factors roughly mirror stages described in Latané & Darley's 5-stage bystander model (1969) and are represented by squares running through the middle of the model. The remaining four considerations identified by respondents seemed to be unique to the issue of intervening in violence-related behavior and are depicted by circles within the figure. Twenty-three of the men (85%) identified being influenced by three or more considerations. As a descriptive model, linearity or temporality is not implied, although the sequencing in Latané and Darley's model has been retained. Rather, this figure depicts considerations that were simultaneously “live” for participants in an interrelated way as they recalled a bystander experience or spoke about issues that generally facilitate or inhibit their own intervening behavior. Each theme, starting with those that overlap with Latané and Darley's 5-stage model, is described below.

Figure 1.

Influences on antiviolence bystander behavior among male allies

Defining a situation as actionable

Thirteen participants (48%) described weighing whether a particular behavior or situation was “bad enough” to warrant taking action. For some participants, this took the form of realizing later that someone else's behavior had been egregious enough to warrant a response, whereas for others, this was an active struggle in the moment. For the latter, there was ambiguity about how harmful someone's behavior really was, whether it was fitting to “haggle” (MAV3) over someone's words or whether they were accurately reading the situation as inappropriate or dangerous, as reflected in the following comment:

. . . there's no flashing light or sign that says like, “Hey this is really going on.” You know, in our conversation, we may just be joking around. There's never some point where an exclamation point appears over somebody's head that says he's about to make a comment. (MAV2)

Others spoke about being selective about when to define something as actionable for fear of being labeled as “the police” (MAV20), as indicated by one participant's remarks:

I don't do it all the time because I don't want to be the, “Oh [he] is around, you don't want to talk about that.” So I'm very selective . . . you know, I will kind of weigh if it's something I really need to speak up about. (MAV21)

Responsibility

Twelve men (44.4%) described pondering whether it was their responsibility to “step up” in a problematic situation. Some of these participants spoke about always feeling a sense of personal duty to intervene, such as the college resident advisor whose position engenders a sense of accountability and leads him to “correct them every time I hear the ‘gay’ word” used as a put-down (MAV11). Others grappled with whether they should be the one to step into others’ business or conversations. For some, this was about managing the degree to which being an ally permeated their life, such as the college student who noted his thought process when hearing troubling statements from others as he walks across campus:

It's almost like having to weigh, “am I going to make this a part of my day, too?” . . . I mean ultimately it's always worth it for me because I feel no regret over . . . well I haven't yet . . . [laughs] . . . over calling someone out or sparking up a conversation like that. But at the same time, I always have to keep in mind like I have these other things in my day and really it goes into time management. (MAV30)

Another participant relayed weighing whether it was his job or place to say something to a friend who was possibly abusive to a partner:

I think one of the barriers would be respect. Like not stepping on somebody's toes, . . . not telling somebody how to run their relationship, not assuming you know all the circumstances around what's going on. (MAV3)

Self-efficacy

Mirroring Latané and Darley's stage of identifying an accessible course of action, 21 participants (78%) described weighing their own perceived competence to successfully intervene. Some reported that they had developed an effective set of strategies over time that they could successfully employ or felt that they were equipped with the knowledge and language needed to stage an intervention, such as this participant, “I guess I feel like because I have a lot of knowledge about it I can defend my position in a more logical way, and that makes me feel more comfortable and powerful” (MAV22). Others reported gaining confidence because of past interventions that had gone well. One participant, who described himself as “recently” accessing the courage to speak up, attributed his newfound courage to a successful intervention with a fellow group member, which he experienced as “empowering” (MAV10).

Conversely, most respondents mentioning self-efficacy spoke of being unsure about how to respond to problematic behavior or lacking confidence in launching an intervention. For some, this was due to a perception of lacking the tools or strategies they needed to effectively take action, as captured in the following participants’ words, “I was like . . . okay, how do I do this? You know, I can't really call the cops . . . and say ‘Yeah this guy's being a dick’” (MAV9) and

. . . what would be helpful and useful would be tools . . . to where I may not always be able to put my sentences together or remember a word that I'm thinking of . . . to have the tools, to have a go-to sentence, to have some quick answers to some of the most-asked questions. (MAV18)

Others noted that the dynamics of bystander moments made it difficult to actually employ those skills, as evidenced by the following participant speaking of the “intensity” of bystander opportunities, “I don't know if I feel comfortable . . . I'm building up the ability to pick the right spot . . . I imagine I will find a voice” (MAV14).

Context

Most of the men (78%) described situation-specific factors that influenced their decision to act or not. Some of these factors included the respondent's relationship with the perpetrator and victim (if present), the number of people present, the setting (i.e., a football game vs. a private conversation), and whether those present had been drinking. Although a majority of the participants described contextual factors as playing into their decision about whether to confront problematic behavior (echoing the “bystander effect”), no clear patterns emerged about these factors’ influence. Participants’ decoding of context seemed highly individualized. For example, some men reported feeling more comfortable intervening with someone they know:

Good friends I'm just going to straight up call them on it . . . but maybe with people that I've met a couple of times but don't know all that well, I might not be the one to say something because I'm just not comfortable enough. (MAV7)

In contrast, others felt more efficacious in confronting strangers, such as the participant who noted, “It's much easier for me to say something to someone I don't know . . . it's like I don't care as much what they think” (MAV28). Another noted complexities related to the nature of his relationship with the target of an intervention:

It's almost easier when you don't know somebody. It's kind of a bell curve. Like its easy [when you're strangers] and then you get to know someone, and it gets harder and harder and then at some point . . . you start to get so familiar with that person that its easier again, because you know that it's not going to end your relationship. (MAV30)

Similarly, participants had different feelings about the role of the group size. Most participants felt that interventions were easier in one-on-one or smaller group situations. Others felt that speaking up in the context of larger groups could be less intense or carried the promise of others speaking up as well. One fraternity member stated, “I think it's actually easier to get guys if you're in a larger group, like I'm talking twenty-five, thirty, like our fraternity meetings, and somebody says something, I could easily get one or two [allies] at least” (MAV21).

Norms

Closely related to contextual considerations, perceived social or group norms affected the behavior of 20 participants (74%). Two subthemes emerged related to men's appraisal of relevant norms. First, 17 participants (63%) talked about the role of male gender norms and expectations related to masculinity as barriers to taking action. Some perceived that other men associate talking about violence against women, talking about being offended by others’ behavior, or policing others’ language as weak, antimale, “uncool” (MAV11), “goody two-shoes” (MAV4), or “less than a man” (MAV6), all attributes described by participants as counter to codes of masculinity. One participant explained that “there's something in the society that . . . has like an agenda to make it seem like you're being a wimp if you stick up for women” (MAV4). Other men described explicit codes in male peer groups against challenging each other's behavior or impeding sexual access to women. Some men identified the notion of a “cock block” as a label to avoid:

The idea of the cock block is big in our college society today, that men don't want to be a cock block to another man. And so the idea of doing that to another man is kind of like part of man law that you're not supposed to prevent another man, no matter if you know him or not, from hooking up with someone. (MAV12)

Participants mentioning masculinity-related norms also described assessing issues of power or hierarchy between themselves and the target of a possible intervention within a group. Being higher status in a group, older, “alpha male,” (MAV21) or in a recognized position of authority in relation to another person seemed to render intervening more likely or less difficult. One participant, describing a time he ultimately chose to say something to an offensive fellow group member noted, “This is a man that I felt . . . that in the past I would have felt had more power than I did, so I needed to kowtow to him, and I didn't [this time]. I stood my ground” (MAV10). Another respondent reported that he found it easier to challenge youth than to challenge same-age or older male colleagues who might assume that “I don't necessarily know what I'm talking about” (MAV15).

Respondents also reported attending to the implicit norms within the specific groups or relationships in which bystander opportunities occurred. Seventeen of the participants (63%) worried that speaking up might violate group norms and could cause them to be stigmatized, “outcast” (MAV21), or excluded from groups or relationships that are important to them. One participant noted that he perceives disagreeing with a group norm as difficult for him:

Having an entire table, especially people that I've just met, disagreeing and talking back to me would really separate me from this group that I'm trying to get to know. So I'd say fear of social rejection is probably a strong factor in that. (MAV29)

Another discussed the intricacies of norms and relationships within group situations:

So it gets really complex because . . . you don't want to make people feel bad about laughing. You don't want to break up a flow of conversation. You don't want to sort of damage your relationships. There's all these different things to weigh in that moment. (MAV28)

Norms within groups or relationships also seemed closely related to the following theme, outcome evaluations, in that participants’ assessment of norms often centered on how perceived norms might affect the consequences of taking action in the moment.

Outcome evaluations

Eighteen participants (67%) described evaluating the possible contingencies or consequences of inaction versus action. Outcomes associated with action included the likelihood that they would be “backed up” by others in an intervention situation and whether the planned intervention would be effective or “worth” (MAV 11) the effort. For six of these participants, concerns about their own or a woman's physical safety surfaced, with one man commenting, “how do you know you're not going to make it worse for the woman?” (MAV3). However, participants also reported being motivated to act by the possible negative consequences for a potential victim of failing to intervene:

If you see something going on, you need to intervene, because if you don't, you don't know what's going to happen. And if something bad happens, you own part of it. It's kind of how I see it. (MAV1)

Personal identity

Finally, six men (22%) perceived that aspects of their own identities or perceived identities were relevant to the decision to intervene. Two of these men noted that identifying as gay or queer resulted in added social vulnerability or even physical risk if an intervention revealed this part of their identity to others:

. . . you kind of are thinking about, well, does my identity as a queer person have to play into what I'm going to say? Does it have to play into my safety? You know what if I'm the only person who thinks this way, and now I'm in a group of people where I'm now the minority, and there's a group of guys who are physically stronger than me . . . (MAV15)

For others, a lack of comfort with their own sense of self, or a self-perceived lack of “purity” (a lack of a perfect past record of nonsexist behavior; MAV28), somehow rendered intervening hypocritical for them. In contrast, one participant who identified as “always” intervening stated,

I'm to that point in my life now where we don't have to do that little façade thing: I'm this way with my friends, I'm this way at home, I'm this way at work. Today I'm [me], and it doesn't matter where I go. If you like me, fine. If you don't, that's fine too. (MAV1)

Discussion

A majority of the male antiviolence allies in this study reported that they intervene or take some form of action when confronted with exploitive, offensive, or inappropriate behavior by other men. At the same time, only a moderate percentage of the respondents (26%) report consistently intervening. Not surprisingly, and regardless of the frequency with which they respond to bystander “opportunities,” men reported that intervening is challenging, complex, and can be an ongoing struggle and source of guilt. Perhaps, the most important theme to emerge from these analyses, then, is that being a “positive” bystander is a difficult undertaking under the best of circumstances. Respondents in this study are self-identified antiviolence allies, many of whom have had hours of training and multiple opportunities to discuss these kinds of situations—and yet continue to struggle with how to respond to inappropriate behavior in the moment. It is reasonable to speculate that the complexities of intervening described by these respondents may prove even more daunting for men without the level of support or training enjoyed by many of the participants in the study. These complexities hold implications for theory and intervention development, described in turn below.

Overlap With Models of Bystander Behavior

As previously noted, three of the considerations identified by respondents as relevant to their own response to bystander situations closely corresponded to stages within Latané and Darley's (1969) model of bystander intervention. Specifically, men reported weighing whether a situation was problematic enough to warrant action, whether it was appropriate to assume responsibility to take action, and whether they had the skills or tools to successfully intervene. Moreover, in line with the years of bystander research subsequent to Latané and Darley's work, each of these stages appeared to simultaneously affect and be influenced by a range of deeply contextual and individual factors—factors that warrant inclusion in developing conceptual models of violence-related bystander behavior. Assessments of whether a peer's behavior was “bad” enough to demand a response, for example, were mutually influenced by men's perceptions of their own relationship and status relative to the “offender,” to their relationships with and perceived norms of present group members, to their own identities, and to their assessments of likely outcomes of taking action or staying silent within the situation. Furthermore, an individual's decision about the actionability of a behavior might change across circumstances and time, suggesting the need for flexible and contextualized models of violence-related bystander behavior.

Many of the factors influencing bystander behavior here mirror constructs within the theory of planned behavior (TPB; Ajzen, 1991), a model that offers a way to concretize some of the complexities of intervening behavior. This social cognitive theory posits that a specific behavior is predicted by intention to engage in the behavior, which in turn is related to individuals’ attitudes, perceptions of subjective norms, and perceived self-efficacy related to the behavior (Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2002). Each of these latter constructs has a parallel in the bystander considerations raised by respondents. For example, the TPB construct of subjective norms is reflected in the men's assessment of how important others (such as other men or other present group members) might perceive intervening behavior. Moreover, men's perceptions of the likely outcomes of taking action echo the TPB construct of attitudes, which is operationalized as being affected by a combination of individuals’ beliefs about the possible results of a behavior and their evaluation of those results as positive or negative. Incorporating the TPB with constructs from Latané and Darley's 5-stage model may offer a more comprehensive mechanism for capturing the processes involved in evaluating antiviolence bystander opportunities. Assessing the possible outcomes of taking action as positive or negative is also consistent with the aforementioned work of Piliavin and colleagues (1981), whose model contends that individuals weigh the potential costs and benefits of stepping forward. Enhancing models of violence-related bystander behavior may necessitate further elucidating allies’ specific perceptions of probable outcomes of intervention.

Implications for Bystander-Based Prevention Intervention

Several of the factors identified as relevant to bystander decision making provide support to the content of existing bystander intervention programs. For example, participants reported struggles with determining whether someone else's behavior was “bad enough” and with feeling confident and skilled enough to step forward. These barriers echo topics within programs such as “Bringing in the Bystander” (Banyard et al., 2007) that focus on educating participants about risky, assault-related behaviors and on skill building for intervening in those behaviors in a variety of ways. Sustaining male allies’ ability to enact positive bystander behavior may also be supported by explicitly attending to other specific barriers to intervening identified by participants. These include acknowledging men's concerns about social hierarchies or negotiating codes of masculinity, about the role of their own identities in weighing safe options for intervention, and about men's need to preserve the relationships and group memberships that are inextricable from these encounters. Acknowledging and honoring the variety of social and personal goals with which men enter bystander opportunities may help to facilitate the identification of accessible options for taking action that can be maintained over time. At the same time, given evidence that men overestimate other men's support for coercive or rape-supportive behavior (Fabiano et al., 2003), it may be important to surface and test allies’ assumptions about their peers’ masculinity-related norms. Encouraging men to take risks and speak up holds the potential to empower other, previously hidden, antiviolence allies in bystander situations.

Men in this study also evidenced a highly individualized approach to interpreting the dynamics of bystander opportunities. For example, the bystander effect (Latané & Darley, 1969), and patterns related to the degree of common social identification within a bystander situation (Levine & Crowther, 2008), did not operate uniformly among participants. Some men felt more comfortable intervening one-on-one, others felt that a group offered more support; many men described greater comfort saying something to someone known to them, whereas others reported greater ease intervening with strangers. All of these perceptions were complicated by individualized assessments of status, self-efficacy, and other contextual elements. This suggests that bystander intervention programs would be well served to help men develop a wide variety of tools, statements, and strategies that could be flexibly employed across a range of bystander opportunities and time. Opportunities to reflect on and problem solve bystander experiences and to do additional skill building over time may also help to sustain men's efforts as several men reported the importance of experience and building on past successes. Finally, it may be important for bystander programs to explicitly communicate that it is not realistic or even perhaps desirable for allies to attempt action in every single situation, a message that may free men to step forward in the moments that are most critical or in which they can be most effective. This may also prevent allies from feeling like the “police” and either burning out or giving up as they perceive those around them to minimize or discount their words.

Limitations

Limitations include the marked racial homogeneity of the sample. These findings almost exclusively represent White men's experiences with bystander behavior and fail to examine the ways that race or experiences of racism (or other sources of marginalization) interact with men's perception of or behavior within bystander opportunities. A second limitation is the small, self-selected nature of the sample which may introduce bias in the types of experiences most represented. Finally, data about men's bystander experiences were collected as only one topic within a larger study, which may have limited the degree to which the dimensionality and temporality of men's experiences was uncovered. In-depth, longitudinal research is needed that examines allies’ bystander experiences and behaviors over time and that more clearly maps supports for and barriers to intervention within specific types of bystander opportunities.

Conclusion

Given the increasing prevalence and promise of bystander approaches to intimate violence prevention, it is important to continue to elucidate the factors that both impede and support antiviolence allies in consistently confronting problematic behavior. Evidence from the male allies in this study suggest that helping men to develop an assortment of tools, strategies, and words that can be flexibly employed across a variety of bystander opportunities may help them to negotiate the individualized and inevitable barriers to taking action they encounter.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the 27 men who volunteered their time to participate in this study, along with the many individuals who provided consultation throughout the process of the research, including Charles Emlet, Jonathan Grove, and Diane Morrison.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by a University of Washington, Tacoma Founder's Grant.

Biography

Erin A. Casey, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor of Social Work at the University of Washington, Tacoma. She received her M.S.W. and Ph.D. in Social Welfare at the University of Washington, Seattle and has over 10 years of practice experience in the fields of domestic and sexual violence. Erin's research interests include the etiology of sexual and intimate partner violence perpetration, examining ecological approaches to violence prevention, and exploring intersections between violence, masculinities, and sexual risk.

Kristin Ohler is completing her Master's in Social Work degree at the University of Alaska, Anchorage. She has approximately six years of experience in the field of social service, and her areas of interest include intimate partner violence, LGBTQ experiences in health and mental health settings and the experiences of those with developmental disabilities.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Portions of this article were presented at the 2009 Conference on Men and Masculinities in Portland, Oregon and the 2010 Society for Social Work Research Conference in San Francisco, California.

References

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL, Maynihan MM, Plante E. Sexual violence prevention through bystander education: An experimental evaluation. Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;35:463–481. [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL, Plante EG, Moynihan MM. Bystander education: Bringing a broader community perspective to sexual violence prevention. Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;32:61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Brown AL, Messman-Moore TL. Personal and perceived peer attitudes supporting sexual aggression as predictors of male college students’ willingness to intervene against sexual aggression. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25:503–517. doi: 10.1177/0886260509334400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burn S. A situational model of sexual assault prevention through bystander intervention. Sex Roles. 2009;60:779–792. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence: Program activities guide. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pub/ipv_sv_guide.html.

- Chekroun P, Brauer M. The bystander effect and social control behavior: The effect of the presence of others on people's reactions to norm violations. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2002;32:853–867. [Google Scholar]

- Christy CA, Voight H. Bystander responses to public episodes of child abuse. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1994;24:824–847. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss AC. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3rd ed. SAGE; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Earle JP. Acquaintance rape workshops: Their effectiveness in changing the attitudes of first year college men. NASPA Journal. 1996;34:2–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano PM, Perkins HW, Berkowitz AD, Linkenbach J, Stark C. Engaging men as social justice allies in ending violence against women: Evidence for a social norms approach. Journal of American College Health. 2003;52:105–112. doi: 10.1080/07448480309595732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood M. Changing men: Best practic in sexual violence education. Women Against Violence. 2005;18:26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Foubert JD. The longitudinal effects of a rape-prevention program on fraternity men's attitudes, behavioral intent, and behavior. Journal of American College Health. 2000;48:158–163. doi: 10.1080/07448480009595691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foubert JD, Perry B. Creating lasting attitude and behavior change in fraternity members and male student athletes: The qualitative impact of an empathy-based rape prevention program. Violence Against Women. 2007;13:70–86. doi: 10.1177/1077801206295125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritzsche BA, Finkelstein MA, Penner LA. To help or not to help: Capturing individuals’ decision policies. Social Behavior and Personality. 2000;28:561–578. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins SR. Evaluation findings: Men Can Stop Rape, Men of Strength Clubs 2004-2005. 2005 Retrieved www.mencanstoprape.org.

- Humphrey SE, Kahn AS. Fraternities, athletic teams, and rape. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2000;15:1313–1322. [Google Scholar]

- Katz J. Reconstructing masculinity in the locker room: The Mentors in Violence Prevention Project. Harvard Educational Review. 1995;65:163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Latané B, Darley J. Bystander “apathy.”. American Scientist. 1969;57:244–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latané B, Nida S. Ten years of research on group size and helping. Psychological Bulletin. 1981;89:308–324. [Google Scholar]

- Levine M, Crowther S. The responsive bystander: How social group membership and group size can encourage as well as inhibit bystander intervention. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95:1429–1439. doi: 10.1037/a0012634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon S. Rape myth beliefs and bystander attitudes among incoming college students. Journal of American College Health. 2010;59:3–11. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.483715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon S, Farmer GL. The bystander approach: Strengths-based sexual assault prevention with at-risk groups. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2009;19:1042–1065. [Google Scholar]

- Montaño DE, Kasprzyk D. The theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health behavior and health education. 3rd ed. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2002. pp. 67–98. [Google Scholar]

- Piliavin JA, Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL, Clark RD. Emergency intervention. Academic Press; New York, NY: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MD, DeKeseredy WS. Sexual assault on the college campus: The role of male peer support. SAGE; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Prevalence, incidence and consequences of violence against women: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. National Institute of Justice; Washington, DC: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ward K. MVP: Evaluation 1999-2000. Northeastern University Center for Study of Sport and Society; Boston, MA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz AN, Black BM. Peer intervention in dating violence: Beliefs of African-American middle school adolescents. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work. 2008;17:177–196. doi:10.1080/15313200801947223\. [Google Scholar]