Abstract

Lactimidomycin (LTM, 1) and iso-migrastatin (iso-MGS, 2) belong to the glutarimide-containing polyketide family of natural products. We previously cloned and characterized the mgs biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces platensis NRRL 18993. The iso-MGS biosynthetic machinery featured an acyltransferase (AT)-less type I polyketide synthase (PKS) and three tailoring enzymes (MgsIJK). We now report cloning and characterization of the ltm biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces amphibiosporus ATCC 53964, which consists of nine genes that encode an AT-less type I PKS (LtmBCDEFGHL) and one tailoring enzyme (LtmK). Inactivation of ltmE or ltmH afforded the mutant strain SB15001 or SB15002, respectively, that abolished the production of 1, as well as the three cometabolites 8,9-dihydro-LTM (14), 8,9-dihydro-8S-hydroxy-LTM (15), and 8,9-dihydro-9R-hydroxy-LTM (13). Inactivation of ltmK yielded the mutant strain SB15003 that abolished the production of 1, 13, and 15 but led to the accumulation of 14. Complementation of the ΔltmK mutation in SB15003 by expressing ltmK in trans restored the production of 1, as well as that of 13 and 15. These results support the model for 1 biosynthesis, featuring an AT-less type I PKS that synthesizes 14 as the nascent polyketide intermediate and a cytochrome P450 desaturase that converts 14 to 1, with 13 and 15 as minor cometabolites. Comparative analysis of the LTM and iso-MGS AT-less type I PKSs revealed several unusual features that deviate from those of the collinear type I PKS model. Exploitation of the tailoring enzymes for 1 and 2 biosynthesis afforded two analogues, 8,9-dihydro-8R-hydroxy-LTM (16) and 8,9-dihydro-8R-methoxy-LTM (17), that provided new insights into the structure–activity relationship of 1 and 2. While 12-membered macrolides, featuring a combination of a hydroxyl group at C-17 and a double bond at C-8 and C-9 as found in 1, exhibit the most potent activity, analogues with a single hydroxyl or methoxy group at C-8 or C-9 retain most of the activity whereas analogues with double substitutions at C-8 and C-9 lose significant activity.

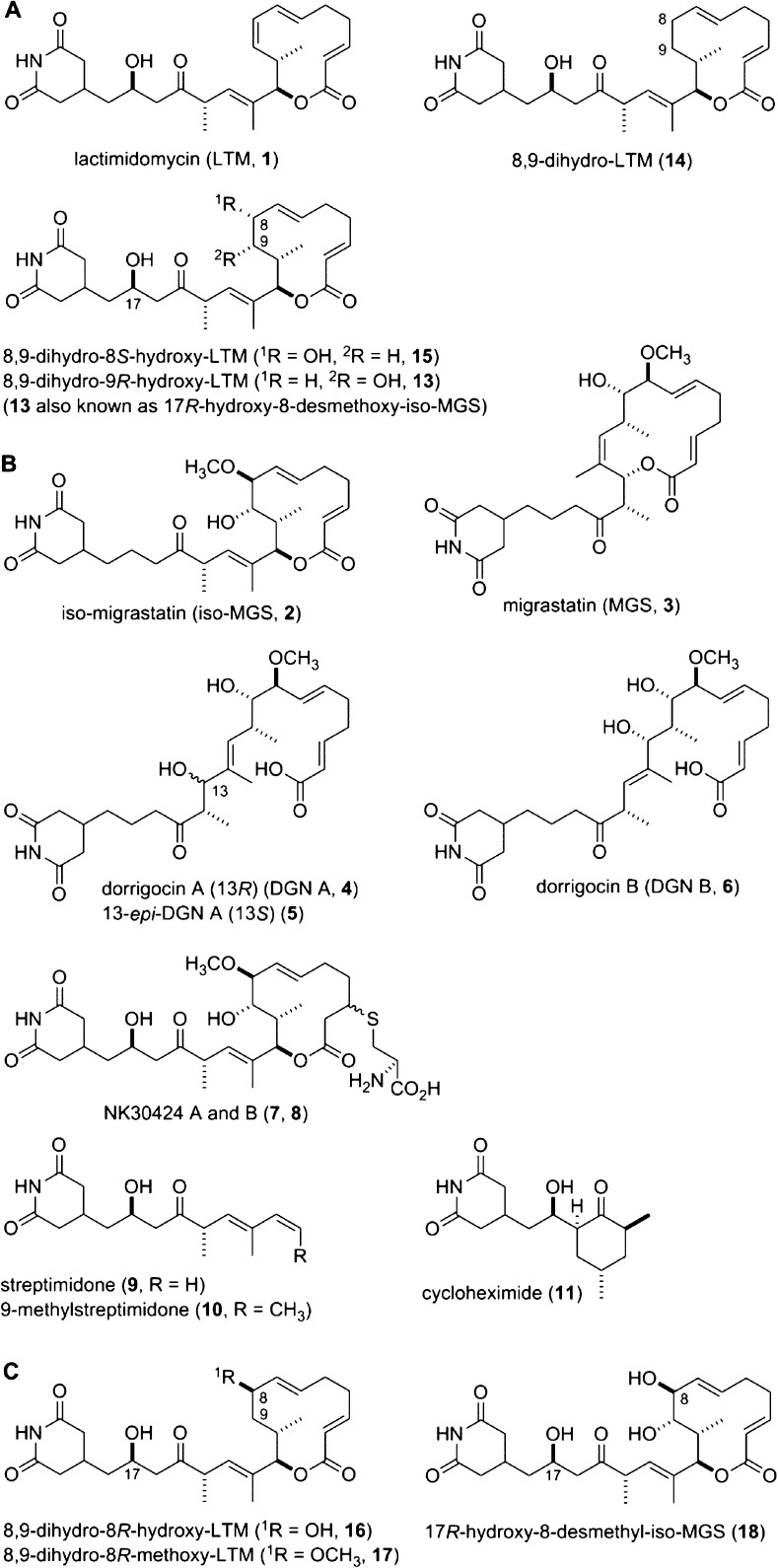

Lactimidomycin (LTM, 1) belongs to the glutarimide-containing polyketide family of natural products.1,2 Other members of this family include iso-migrastatin (iso-MGS, 2), migrastatin (MGS, 3), the dorrigocins (DGNs, 4–6), NK30424A and -B (7 and 8, respectively), the streptimidones (9 and 10), and cycloheximide (11) (Figure 1). Originally, 1 was isolated from Streptomyces amphibiosporus ATCC 53964 for its potent cytotoxicity activity against various tumor cells;33 was isolated in Streptomyces sp. MK929-43F1 for its modest tumor cell migration inhibitory activity,4,5 and 4–6 were isolated from Streptomyces platensis NRRL 18993 as inhibitors of carboxyl methyltransferases involved in the processing of Ras-related proteins.6,7 Fermentation optimization subsequently resulted in the isolation of 2 from S. platensis NRRL 18993.8 Identical to the cysteine adducts of 2,17 and 8 were first isolated from Streptomyces sp. NA30424 for their ability to inhibit PLS-induced TNF-α production by suppressing the NF-κB signaling pathway.9 Mostly known for their antifungal activity, 9 and 10 have been isolated from various Streptomyces species.10,11 Finally, best known as an inhibitor of eukaryotic protein translation, 11 was first isolated from Streptomyces griseus and has since been isolated from numerous Streptomyces species.12−14

Figure 1.

Structures of (A) LTM (1) and congeners (13–15) from S. amphibiosporus ATCC 53964, (B) selected members of the glutarimide-containing polyketide family of natural products (2–11), and (C) engineered glutarimide-containing polyketides (16 and 17) bearing structural features of both 1 and 2, and 17R-hydroxy-8-desmethyl-iso-MGS (18), a congener of 2 used as a comparison for cytotoxicity assays in Table 2.

Among the multitude of activities exhibited by the glutarimide-containing polyketides, the tumor cell migration inhibitory activity of 3 and the protein translation initiation inhibitory activity of 1 have by far most captured the interests of biologists and chemists.1,2 Accordingly, synthetic analogues of the 14-membered macrolide 3 have been prepared, some with cell migration inhibitory activity ∼3 orders of magnitude greater than that of the natural product, which have been pursued as therapeutic candidates for treating tumor metastasis.15−17 A focused library of glutarimide-containing polyketides has been isolated from optimized fermentations of S. platensis NRRL 18993 and S. amphibiosporus ATCC 53694, and preliminary evaluation of these revealed that 12-membered macrolides, as exemplified by 1 and 2, were also potent inhibitors of tumor cell migration.1,2,18−20 While the exact modes of action that dictate and differentiate cell migration inhibition from cytotoxicity for the glutarimide-containing polyketides remain controversial, the actin-bundling protein fascin has been identified as the target for the cell migration inhibitory activity of 3,21 and blocking the translocation step in eukaryotic protein translation initiation has been deduced as the mechanism for the cytotoxicity of 1.22−24 The latter property of 1, in contrast to 11 that blocks the translocation steps in protein translation elongation, has been exploited in the development of the Global Translation Initiation Sequencing (GTI-seq) technology that allows high-resolution mapping of translation initiation sites across the entire transcriptome.23,24 Small molecule inhibitors of protein translation have also shown promise as potential chemotherapeutic agents for treating cancers.25

We have previously reported that 2 is the true natural product of S. platensis NRRL 18993, and 3–6 are degradation products of 2 that occur during isolation, which can be readily derived from 2 via a facile, H2O-mediated ring expansion or ring-opening rearrangement (Figure S1 of the Supporting Information).26 We subsequently cloned and characterized the mgs biosynthetic gene cluster from S. platensis NRRL 18993 and confirmed 2 as the final product of the iso-MGS biosynthetic machinery, which featured an acyltransferase (AT)-less type I polyketide synthase (PKS) and three tailoring enzymes.27 We have recently revealed that the iso-MGS AT-less type I PKS produces two nascent polyketide intermediates, 16,17-didehydro-8-desmethoxy-iso-MGS (12) and 17R-hydroxy-8-desmethoxy-iso-MGS (13). Further, the biosynthesis of 12 and 13 involves several unusual features that deviate from those of the collinear type I PKS model, and the three tailoring enzymes possess remarkable substrate promiscuity, accounting for the formation of all congeners of 2 known to S. platensis NRRL 18993 from 12 and 13 (Figure S2 of the Supporting Information).28

We have also optimized the fermentation of S. amphibiosporus ATCC 53964 and isolated, in addition to 1, three LTM congeners, 8,9-dihydo-LTM (14), 8,9-dihydro-8S-hydroxy-LTM (15), and 8,9-dihydro-9R-hydroxy-LTM (13) (Figure 1A),18 the latter of which is identical to 17R-hydroxy-8-desmethoxy-iso-MGS (13), one of the two nascent polyketide intermediates synthesized by the iso-MGS AT-less type I PKS (Figure S2 of the Supporting Information).27,28 The structural similarity, with distinct variations, between 1 and 2, and the isolation of the same biosynthetic intermediate 13 from both producers of 1 and 2, suggest close relationships in their biosynthetic pathways.

Here we report the cloning and characterization of the ltm biosynthetic cluster from S. amphibiosporus ATCC 53964. The LTM biosynthetic machinery features an AT-less type I PKS nearly identical to that of 2 but a rare cytochrome P450 desaturase functioning as the sole tailoring enzyme. Comparison of the LTM and iso-MGS biosynthetic machineries allows deduction of a biosynthetic pathway for 1, reveals new insights into the biosynthesis of the glutarimide-containing polyketides, and sets the stage to investigate several unusual features common to AT-less type I PKSs. Exploitation of the tailoring enzymes for 1 and 2 biosynthesis affords two analogues, 8,9-dihydro-8R-hydroxy-LTM (16) and 8,9-dihydro-8R-methoxy-LTM (17), which feature the 17R-hydroxyl group present in 1 and the 8R-hydroxyl or 8R-methoxyl groups present in 2 (Figure 1C) and provide new insights into the structure–activity relationship (SAR) of 1 and 2.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Culture Conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids used are summarized in Table S1 of the Supporting Information. S. amphibiosporus wild-type and recombinant strains were cultivated on ISP4 or tryptic soy broth (TSB) medium at 28 °C.29Escherichia coli strains were grown on lysogeny broth (LB) medium at 37 °C.30 Strains carrying antibiotic resistance markers were selected in medium supplemented with ampicillin (50 μg/mL), apramycin (50 μg/mL), chroramphenicol (50 μg/mL), kanamycin (50 μg/mL), nalidixic acid (20 μg/mL), thiostrepton (5 μg/mL), or trimethoprim (50 μg/mL), where appropriate.29,30

DNA Isolation, Manipulation, and Sequencing

Standard procedures were used to manipulate purified DNA.30 Genomic DNAs were purified from S. amphibiosporus strains using the salting out procedure.29 Plasmids were isolated using available kits (Qiagen). Cosmid DNAs were purified by the alkaline lysis method.17 PCRs were performed using the high-fidelity Expand PCR system according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Roche). Oligonucleotide primers that were used are listed in Table S2 of the Supporting Information. Southern analysis of S. amphibiosporus genomic DNA was conducted using DIG-High Prime DNA Labeling and Detection Starter Kit I following the manufacturer’s protocol (Roche).

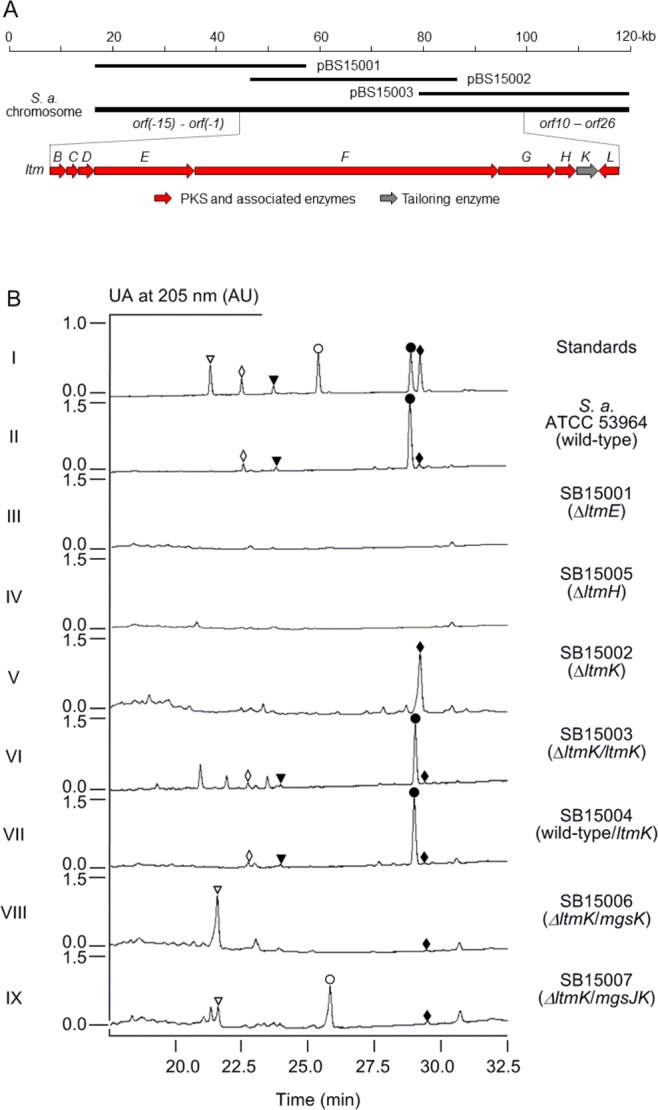

Genome Scanning and Sequence Analysis

Isolation of the ltm biosynthetic gene cluster was performed by the genome scanning method as described previously.27,31 A SuperCos1-based library of S. amphibiosporus ATCC 53964 was constructed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Agilent Technologies). Three cosmids, pBS15001, pBS15002, and pBS15003, covering the entire ltm biosynthetic gene cluster, were identified by probing with PKS genes identified from a genome sampling library and were sequenced (Figure 2A). The DNA sequences obtained were analyzed by the Genetic Computer Group (GCG) program, BLAST-X, N, and P available at National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

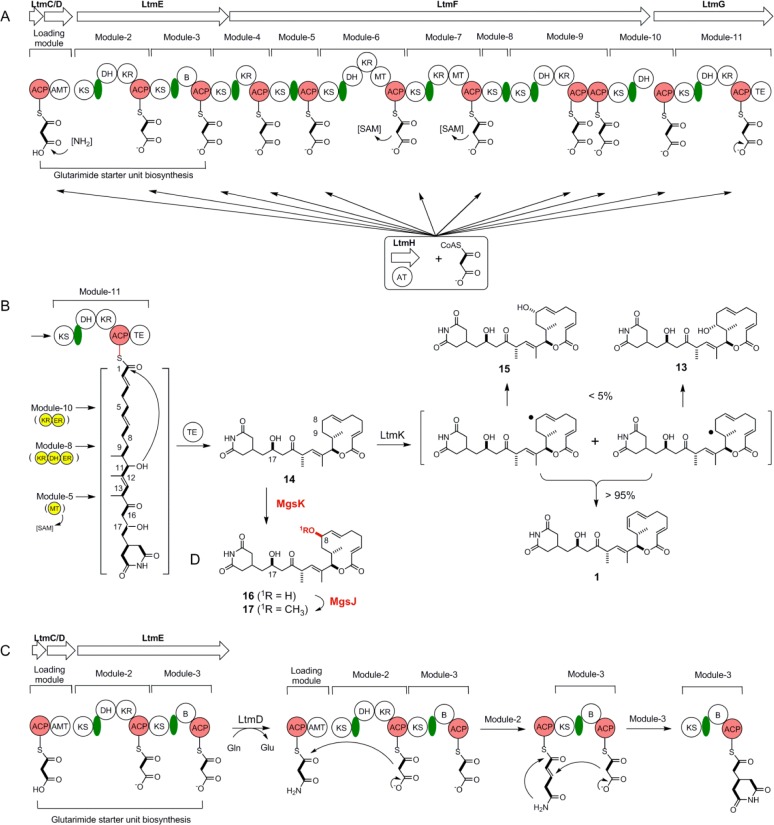

Figure 2.

Cloning and sequencing of the ltm gene cluster from S. amphibiosporus ATCC 53964 and confirmation of its role in LTM (1) biosynthesis. (A) Sequenced 100 kb DNA region covered by three overlapping cosmids and genetic organization of the ltm biosynthetic gene cluster. Proposed functions for individual open reading frames are summarized in Table 1. (B) Inactivation of selected genes within the ltm cluster supporting the proposed pathway for 1 biosynthesis and exploitation of the tailoring enzymes for 1 and 2 biosynthesis affording two novel analogues. HPLC chromatograms show authentic standards of 1 (●), 14 (◆), 13 (▼), 15 (◇), 16 (▽), and 17 (○).

Gene Inactivation in S. amphibiosporus by λ-RED-Mediated PCR Targeting Mutagenesis

The ltmE, ltmH, and ltmK genes, located on pBS15001 and pBS15003 (Figure 2A), were inactivated in S. amphibiosporus ATCC 53964 by λ-RED-mediated PCR targeting mutagenesis.32 Specifically designed primers (Table S2 of the Supporting Information) were used to amplify the disruption cassette from the template plasmid pIJ773.32 The PCR-amplified cassette is comprised of the aac(3)IV gene, conferring apramycin resistance, and an RK2 origin of transfer (oriT), and is flanked by DNA sequence homologous to regions immediately upstream and downstream of the gene to be deleted. This cassette is used to replace the target gene on the cosmid by homologous recombination, yielding pBS15004 (ΔltmE), pBS15005 (ΔltmK), and pBS15008 (ΔltmH) (Figure S3 of the Supporting Information). The resulting mutant cosmids were introduced into the S. amphibiosporus wild-type strain through intergeneric conjugation between S. amphibiosporus and E. coli S17-1.29 Exconjugants with desired double-crossover recombination were selected on the basis of apramycin resistance and kanamycin sensitivity. The genotype of each mutant was confirmed by Southern analysis, and the mutants were subsequently named SB15001 (ΔltmE), SB15002 (ΔltmK), and SB15005 (ΔltmH) (Figure S3 of the Supporting Information).

Generation of the ΔltmK Complementation Strain SB15003

A 2.5 kb SacI–MscI DNA fragment carrying ltmK was first cloned from pBS15003 into pWHM7933 as a SacI–SmaI fragment, creating pBS15006. From there, a 3.0 kb EcoRI–HindIII fragment was purified, Klenow treated (Roche), and ligated into the EcoRV site of pBS11016,27 in which the aac(3)IV gene is replaced by the neo gene conferring kanamycin resistance, affording pBS15007. Expression of ltmK in pBS15007 is under the control of the ErmE* promoter.29 pBS15007 was transformed into E. coli S17-1 and conjugated into SB15002. Exconjugants were selected on the basis of resistance to apramycin and kanamycin, yielding SB15003 as the ΔltmK complemented strain.

Generation of the ltmK Overexpression Strain SB15004

pBS15007 was transformed into E. coli S17-1 and conjugated into the S. amphibiosporus wild-type strain. Exconjugants were selected on the basis of resistance to kanamycin, yielding SB15004.

Construction of Recombinant Strains SB15006 and SB15007 for Production of Novel Analogues

The three genes, mgsI, mgsJ, and mgsK, encoding the three tailoring enzymes for 2 biosynthesis were amplified by PCR from pBS1100627 individually. The ErmE* promoter was amplified by PCR from pWHM79.33 All primers for mgsI, mgsJ, mgsK, and ErmE* contained different restriction enzyme sites (Table S2 of the Supporting Information). The resultant PCR products were digested accordingly and ligated sequentially into the EcoRV and XbaI sites of pBS1101627 to yield pBS15009, in which the expression of each of the mgsIJK genes was under the control of ErmE* (Figure S4 of the Supporting Information). pBS15009 was then digested with either Acc65I and PmeI or Acc65I and AflII, and the resultant fragments were Klenow treated and self-ligated to afford the expression construct pBS15010 (for mgsK) or pBS15011 (for mgsJK), respectively. pBS15010 or pBS15011 was finally introduced into the ΔltmK mutant strain of SB15002 by conjugation, and exconjugates, selected on the basis of apramycin and kanamycin resistance, afforded the recombinant strain SB15006 (i.e., ΔltmK/mgsK) or SB15007 (i.e., ΔltmK/mgsJK), respectively (Figure S4 of the Supporting Information).

S. amphibiosporus Wild-Type and Recombinant Strain Fermentation and Isolation and HPLC Analysis of 1 and Related Metabolites 13–15

S. amphibiosporus ATCC 53964 wild-type and recombinant strains were fermented as previously described.18 Large-scale fermentation to isolate 14 from SB15002 for structural characterization was similarly conducted after incubation in production medium for 7 days. All metabolites were isolated as previously described, and their identities were confirmed by either HPLC analysis in comparison with authentic standards (for 13–15) or 1H and 13C NMR analyses (for 14).18,28

Isolation and Structural Elucidation of Analogues 16 and 17

SB15006 and SB15007 strains were grown on ISP4 medium for sporulation, and spores were harvested and preserved as a 20% glycerol suspension at −80 °C. Large-scale fermentations and metabolite isolation were similarly performed as previously described.18 From a 2 L fermentation of SB15006, 15 (5.0 mg) was purified, and from a 2 L fermentation of SB15007, 15 (2.0 mg) and 16 (5.2 mg) were purified.

8,9-Dihydro-8R-hydroxy-LTM (16)

Colorless oil: [α]27D + 95.4 (c 0.24, DMSO); 1H NMR (700 MHz) and 13C NMR (175 MHz) data in Table S3 of the Supporting Information; HRESIMS for the [M + Na]+ ion at m/z 498.2461 (calcd [M + Na]+ ion for C26H37NO7 at m/z 498.2466).

8, 9-Dihydro-8R-methoxy-LTM (17)

Colorless oil: [α]27D + 123.3 (c 0.24, DMSO); 1H NMR (700 MHz) and 13C NMR (175 MHz) data in Table S3 of the Supporting Information; HRESIMS for the [M + Na]+ ion at m/z 512.2617 (calcd [M + Na]+ ion for C27H39NO7 at m/z 512.2623).

Cytotoxicity Assay

The cytotoxicity assay was conducted using the MTT method as previously described.34 Generally, cells were seeded in 96-well plates (HeLa cervical carcinoma cells, 3000 per well; MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, 10000 per well; and Jurkat T cell lymphoma cells, 40000 per well) and cultured in the presence of serial dilutions of the test compound, with vehicle as a negative control, in a 5% CO2 incubator for 4 days. MTT reagent (Millipore CT0-A) was added (10 μL/well), and incubation continued for 5 h. Then, 100 μL of 2-propanol with 0.04 N HCl was added to each well, and UV absorption for each well was determined using a Synergy II plate reader at 570 and 630 nm. Experiments were conducted in triplicate and repeated twice. Representative dose–response curves are shown in Figure S5 of the Supporting Information, from which EC50 values were determined using GraphPad Prism (Table 2).

Table 2. EC50 Values (nanomolar) of the Novel Analogues 16 and 17 against Selected Cancer Cell Lines in Comparison with Those of 1 and 2 and Selected Congeners 13, 15, and 18a.

| cancer cell line | 2 | 18 | 15 | 13 | 16 | 17 | 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDA-MB-231 | 464 | 1.24 × 103 | 47.6 | 172 | 157 | 87.4 | 11.9 |

| HeLa | 110 | 346 | 11.1 | 35.1 | 30.7 | 13.4 | 2.50 |

| Jurkat | 688 | 1.30 × 103 | 51.8 | 175 | 112 | 115 | 18.0 |

See Figure 1 for structures.

Results

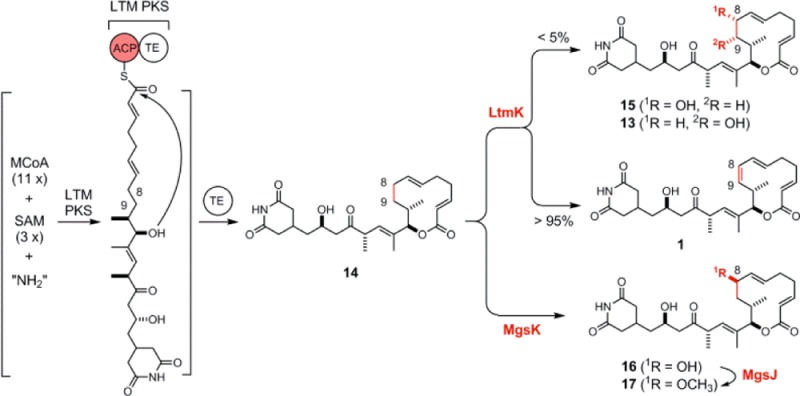

Cloning of the ltm Biosynthetic Gene Cluster from S. amphibiosporus ATCC 53964

The ltm biosynthetic gene cluster was cloned from S. amphibiosporus ATCC 53964 by genome scanning (Materials and Methods).31 Genome scanning and sequence analysis of a 100 kb DNA region from S. amphibiosporus ATCC 53964 revealed a gene cluster that is highly conserved with the mgs gene cluster of S. platensis NRRL 18993 (Figure 2A and Figure S2 of the Supporting Information). The putative ltm cluster was covered by three overlapping cosmids, pBS15001, pBS15002, and pBS15003. Construction of the SB15001 (ΔltmE), SB15005 (ΔltmH), and SB15002 (ΔltmK) mutant strains and subsequent metabolite analysis by HPLC showed these mutants all abolished LTM production, confirming the involvement of this gene cluster in LTM biosynthesis (Figure 2B). Because the boundary of the mgs cluster in S. platensis had been previously determined by systematic gene inactivation,27 we assigned the boundary of the ltm cluster by direct comparison between the mgs and ltm clusters (Figure 2A and Figure S2A of the Supporting Information). The ltm cluster consists of nine genes, and as would be expected from the structural similarity between iso-MGS and LTM (Figure 1), eight of the nine genes within the ltm cluster shared significant homology with genes involved in iso-MGS production in S. platensis NRRL 18993 (Figure 2A, Table 1, and Figure S2 of the Supporting Information).

Table 1. Deduced Functions of ORFs in the ltm Gene Cluster in Comparison with Those in the mgs Gene Cluster.

| gene | deduced product/amino acida | protein homologuesa,b | % identity/ % similarity | proposed functionc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| orf(−15)–orf(−1) | beyond the upstream boundary | ||||

| – | MgsA/1217 (ACY01386) | – | transcriptional activatord | ||

| ltmB | LtmB/539 (ACY01397) | MgsB/539 (ACY01387) | 63/71 | type II thioesterase | |

| ltmC | LtmC/88 (ACY01398) | MgsC/83 (ACY01388) | 68/85 | loading module | ACP |

| ltmD | LtmD/656 (ACY01399) | MgsD/656 (ACY01389) | 82/87 | loading module | amidotransferase |

| ltmE | LtmE/3437 (ACY01400) | MgsE/3192 (ACY01390) | 68/74 | module-2, -3, -4 | KS-DH-KR-ACP-KS-B-ACP-KS |

| ltmF | LtmF/8360 (ACY01401) | MgsF/8021 (ACY01391) | 67/73 | module-4, -5, -6, -7, -8, -9, -10 | KR-ACP-KS-ACP-KS-DH-KR-MT-ACP-KS-KR -MT-ACP-KS-KS-DH-KR-ACP-ACP-KS-DH |

| ltmG | LtmG/2098 (ACY01402) | MgsG/1953 (ACY01392) | 58/68 | module-10, -11 | ACP-KS-DH-KR-ACP-TE |

| ltmH | LtmH/768 (ACY01403) | MgsH/751 (ACY01393) | 65/76 | acyltransferase | |

| – | MgsI/338 (ACY01394) | – | oxidoreductased | ||

| – | MgsJ/281 (ACY01395) | – | O-methyltransferased | ||

| ltmK | LtmK/413 (ACY01404) | MgsK/403 (ACY01396) | 32/47 | cytochrome P450 desaturase | |

| ltmL | LtmL/247 (ACY0140%) | Ppta/246 (AAG43513) | 57/65 | phosphopantetheinyltransferase | |

| orf10–orf26 | beyond the downstream boundary | ||||

Numbers are in amino acids, and given in parentheses are NCBI accession numbers.

Homologues from mgs clusters are given, and other homologues are included if mgs homologues are absent.

Domain abbreviations: ACP, acyl carrier protein; B, branching; DH, dehydratase; KR, ketoreductase; KS, ketosynthase; MT, methyltransferase; TE, thioesterase.

Function proposed for the genes from the mgs cluster that are missing from the ltm cluster.

Assignment and Annotation of the ltm Cluster

The overall organization of the ltm cluster is highly conserved with respect to the mgs cluster from S. platensis NRRL 18993 (Figure S2A of the Supporting Information), and the deduced gene products from both clusters show remarkable sequence homologies (Table 1 and Figure S2B of the Supporting Information). ORFs immediately upstream [orf(−15)–orf(−1)] and downstream (orf10–orf26) of the ltm cluster encode proteins with no apparent function in 1 biosynthesis. These findings greatly facilitated the assignment of the ltm cluster to nine genes (LtmBCDEFGHKL) that span approximately 55 kb (Figure 2A and Table 1).

Eight of the nine genes within the ltm cluster have homologues in the mgs cluster (Table 1 and Figure S2A,B of the Supporting Information).27 As a result, ltmC encodes an acyl carrier protein (ACP), ltmD encodes an amidotransferase, ltmEFG encode three AT-less type I PKSs, ltmH encodes a discrete AT, and ltmB encodes a type II thioesterase (TE). The three LtmEFG AT-less type I PKSs together comprise 10 PKS modules. Bioinformatics analyses of each of the 10 modules revealed that all ketosynthase (KS) and ACP domains are functional as they contain the conserved Cys-His-His catalytic triad for KS domains and the Ser residue for phosphopantetheinylation in ACP domains. However, module-8 and module-9 of LtmF are unusual, with the former lacking an ACP domain and the latter containing two ACP domains. Other domains within the 10 PKS modules are also predicted to be functional. Thus, the six ketoreductase (KR) domains (in module-2, -4, -6, -7, -9, and -11) all have the conserved GxGxxG motif for NAD(P)H binding. The five dehydratase (DH) domains (in module-2, -6, -9, -10, and -11) all contain the conserved HxxxGxxxxP motif. Both methyltransferase (MT) domains (in module-6 and -7) are characterized with the ExxxGxG motif highly conserved among various S-adenosylmethionine (SAM)-dependent MTs. Module-11 of LtmG features a TE domain at its C-terminus, which catalyzes macrolactonization and release of the completed polyketide product. Taken together, LtmCDEFG constitute the functional LTM AT-less type I PKS, with LtmH providing the AT activity in trans, for the biosynthesis of the nascent glutarimide-containing polyketide intermediate (Figure 3A,B). The glutarimide starter unit is assembled by the loading module of LtmCD and PKS module-2 and -3 of LtmE. LtmE module-3 features the newly discovered branching (B) domain, a hallmark of PKS modules that generate a β-branch by catalyzing a Michael addition of a C2 unit to the growing polyketide chain (Figure 3C).11,14,35,36 LtmB, a type II TE, plays an editing role to ensure polyketide biosynthesis by removing mischarged substrates or aberrant intermediates that might otherwise block the LTM AT-less type I PKS.37,38

Figure 3.

Proposed biosynthetic pathway for LTM (1) featuring the LTM AT-less type I PKS that affords 14 as the nascent product and the LtmK P450 desaturase that catalyzes the conversion of 14 to 1, and production of novel analogues by exploiting the tailoring enzymes in 1 and 2 biosynthesis. (A) Schematic depiction of the LTM AT-less type I PKS consisting of LtmCDEFG with the discrete LtmH AT that acts iteratively in trans, loading malonate onto each of the 11 modules. (B) LtmK P450 desaturase converts 14 to 1 via transient radical intermediates accompanied by 13 and 15 as minor hydroxylated products. (C) Revised proposal for glutarimide starter unit biosynthesis featuring the LtmD amidotransferase that furnishes an ACP-tethered malonamoyl thioester intermediate and the KS-B-ACP tridomain PKS module-3 of LtmE that affords the ACP-tethered glutarimide starter unit via a Michael addition. (D) Production of novel analogues 16 and 17, featuring the 17R-hydroxyl group as in 1 and 8R-hydroxyl or 8R-methoxyl group as in 2, by expressing mgsK or mgsJK in the ΔltmK mutant. Abbreviations: ACP, acyl carrier protein; AMT, amidotransferase; B, branching; DH, dehydratase; ER, enoylreductase; KR, ketoreductase; KS, ketosynthase; MT, methyltransferase; TE, thioesterase. [NH2] represents the amino donor for the AMT domain. [SAM] denotes S-adenosylmethionine as the methyl donor for the MT domain. Green ovals represent AT-docking domains, and the yellow domains highlight the missing domains for the LTM AT-less type I PKS predicted according to the colinearity model for 14 biosynthesis.

Distinct differences also exist between the mgs and ltm clusters (Table 1 and Figure S2 of the Supporting Information). Within the ltm cluster, pathway-specific regulatory genes are absent, whereas the mgs cluster has a regulatory mgsA gene. While there are three genes within the mgs cluster that encode the tailoring enzymes MgsIJK, ltmK is the only gene within the ltm cluster that encodes a tailoring enzyme, indicative of variations in post-PKS modifications between 1 and 2 biosynthesis. Sequence analysis revealed that LtmK is a cytochrome P450 protein with the conserved oxygen-activating (GxxT) and heme binding (GxxxCxG) motifs, both critical for the activity of P450 enzymes. LtmK shares homology with MgsK (32% identical and 47% similar)17 and other cytochrome P450 monooxygenases, such as PldB (39% identical and 54% similar) for pladienolide B biosynthesis from S. platensis Mer-1110739 and Ema1 (34% identical and 50% similar) for avermectin biosynthesis from Streptomyces tubercidicus R-922 (Figure S1D of the Supporting Information).40 Finally, the ltm cluster contains an additional ltmL gene that is absent in the mgs cluster. LtmL shares homology with phosphopantetheinyl transferases, including PptA (63% identical and 72% similar) for bleomycin biosynthesis from Streptomyces verticillus,41 SePptII (57% identical and 65% similar) for erythromycin biosynthesis from Saccharopolyspora erythraea,42 and NysF (57% identical and 65% similar) for nystatin biosynthesis from Streptomyces noursei.43 LtmL ensures that the LTM AT-less type I PKS is in its functional holo form by phosphopantetheinylating the serine residues of each of the 11 ACPs.41

Development of a Genetic System for S. amphibiosporus ATCC 53694

An efficient genetic system for S. amphibiosporus ATCC 53694 was established by E. coli–Streptomyces intergeneric conjugation (Materials and Methods). S. amphibiosporus grows well on ISP4 medium, and sporulation typically requires incubation for 10–14 days at 28–30 °C. The S. amphibiosporus wild-type strain shows extreme sensitivity to apramycin, kanamycin, and thiostrepton, but its growth is not affected by trimethoprim (50 μg/mL) or nalidixic acid (20 μg/mL). Although protoplast-mediated transformation in S. amphibiosporus was not successful under all conditions examined, E. coli–S. amphibiosporus intergeneric conjugation can proceed with high efficiency.29 With E. coli S17-1 (DNA methylation proficient) or E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002 (DNA methylation deficient) as donors and S. amphibiosporus spores as recipients, integrative plasmids such as pSET152 can be introduced into S. amphibiosporus with conjugation frequencies of 10–6 or 10–7, respectively (Table S1 of the Supporting Information). Selected E. coli–Streptomyces shuttle vectors, commonly used in Streptomyces genetics, including pKC1218, pKC1139, pBS3031, and pHZ1358 (Table S1 of the Supporting Information), with copy numbers varying from one to 300 copies per cell,29 were all successfully introduced by conjugation and were stably maintained in S. amphibiosporus ATCC 53694.

Inactivation of ltmE and ltmH Abolishing the Production of 1, as Well as 13–15, in SB15001 and SB15005

The identity of the cloned gene cluster that encodes the production of 1 was confirmed by inactivation of ltmE and ltmH in S. amphibiosporus ATCC 53694 (Materials and Methods). The ltmE gene encodes module-2 and -3 of the LTM AT-less type I PKS that is responsible for the biosynthesis of the glutarimide starter unit, while ltmH encodes the sole AT that loads malonyl-CoA onto each of the PKS modules for LTM biosynthesis (Table 1 and Figure 3A,C). Both ltmE and ltmH were inactivated by replacement of an internal fragment, encoding the KS domain in PKS module-2 of LtmE, and a 2.3 kb fragment, encoding essentially the entire LtmH, respectively, with the aac(3)IV-oriT cassette through λ-RED-mediated PCR targeting mutagenesis.32 The genotypes of the resulting mutant strains of SB15001 (i.e., ΔltmE) and SB15005 (i.e., ΔltmH) were confirmed by Southern analysis (Figure S3A,B of the Supporting Information). Both SB15001 and SB15005 were fermented under established conditions for LTM production18 with the S. amphibiosporus wild-type strain as a positive control. While the wild-type strain produced 1, with 13–15 as minor metabolites (Figure 2B, trace II), HPLC analysis revealed that SB15001 and SB15005 completely abolished the production of 1 and the three minor cometabolites 13–15 (Figure 2B, traces III and IV).

Inactivation of ltmK Abolishing 1 Production and Leading to the Accumulation of 14 as the Nascent Polyketide Intermediate

The ltmK gene encodes the sole post-PKS tailoring enzyme in 1 biosynthesis, and inactivation of ltmK would therefore allow one to identify the nascent polyketide intermediate and explore the exact role of LtmK in tailoring the penultimate intermediate to 1 (Figure 3B). The ltmK gene was inactivated by replacing the entire gene with the aac(3)IV-oriT cassette through λ-RED-mediated PCR targeting mutagenesis,32 and the genotype of the resulting SB15002 strain was confirmed by Southern analysis (Figure S3C of the Supporting Information). To complement the ΔltmK mutation in SB15002, pBS15007, a construct in which the expression of ltmK is under control of the constitutive ErmE* promoter,29 was introduced into SB15002 by conjugation to afford SB15003. Finally, to investigate the effect of overexpression of ltmK on the production of 1, pBS15007 was also introduced into the S. amphibiosporus wild-type strain by conjugation to yield SB15004. SB15002, SB15003, and SB15004 were subjected to fermentation, under the previously established condition for 1 production,18 with the S. amphibiosporus wild-type strain as a positive control. HPLC analysis indicated that SB15002 completely lost its ability to produce 1, as well as 13 and 15, but rather exclusively accumulated a compound with a retention time identical to that of 14 (Figure 2B, trace V). This compound was isolated and characterized by 1H and 13C NMR, confirming its identity as 14 (Figure S6 of the Supporting Information).18 Production of 1, together with 13 and 15, as well as 14, was restored to levels comparable to that of the S. amphibiosporus wild-type strain in SB15003 (Figure 2B, trace VI). Finally, SB15004 produced an amount of 1 similar to that in the S. amphibiosporus wild-type strain (Figure 2B, trace VII), indicating that the LtmK-catalyzed tailoring step from 14 to 1 was not rate-limiting in 1 biosynthesis. Collectively, these data unambiguously established 14 as the nascent product for the LTM AT-less type I PKS (Figure 3). On the basis of the iso-MGS biosynthetic paradigm, we now propose a similar model for LTM biosynthesis that features the LTM AT-less type I PKS (Figure 3).

Expression of mgsK or mgsJK in the ΔltmK Mutant Resulting in the Production of Novel Analogues

We have previously established that the three tailoring enzymes MgsIJK possessed remarkable substrate promiscuity, accounting for the formation of the various congeners of 2 known to S. platensis NRRL 18993 (Figure S2C of the Supporting Information).27,28 We thus reasoned that MgsK could recognize 14 as a substrate, catalyzing regio- and stereoselective C-8 hydroxylation, the product of which could be further methylated by MgsJ to produce an 8-methoxy analogue (Figure 3D). Two plasmids, pBS15010 and pBS15011, in which the expression of mgsK or mgsJK is under the control of the constitutive ErmE* promoter, were constructed and introduced into the ΔltmK mutant SB15002 (Figure S4 of the Supporting Information). The resultant recombinant strains SB15006 and SB15007 were fermented under the same conditions previously established for production of 1, with SB15002 as a control. Upon HPLC analysis, it was apparent that 14 was essentially all converted into a new product (16) in SB15006 (Figure 2B, trace VIII), which was then further converted into another new product (17) in SB15007 (Figure 2B, trace IX). The two new products were isolated from large-scale fermentations of SB15006 and SB15007, and their structures were elucidated by a combination of spectroscopic analysis. Compounds 16 and 17, featuring the 17R-hydroxyl group as in 1 and the 8R-hydroxyl or 8R-methoxyl groups as in 2, are novel analogues that cannot be produced by either the LTM or iso-MGS biosynthetic machinery alone, once again highlighting the power of combinatorial biosynthesis in natural product structural diversity.

Structural Elucidation of 16 as 8,9-Dihydro-8R-hydroxy-LTM and 17 as 8,9-Dihydro-8R-methoxy-LTM

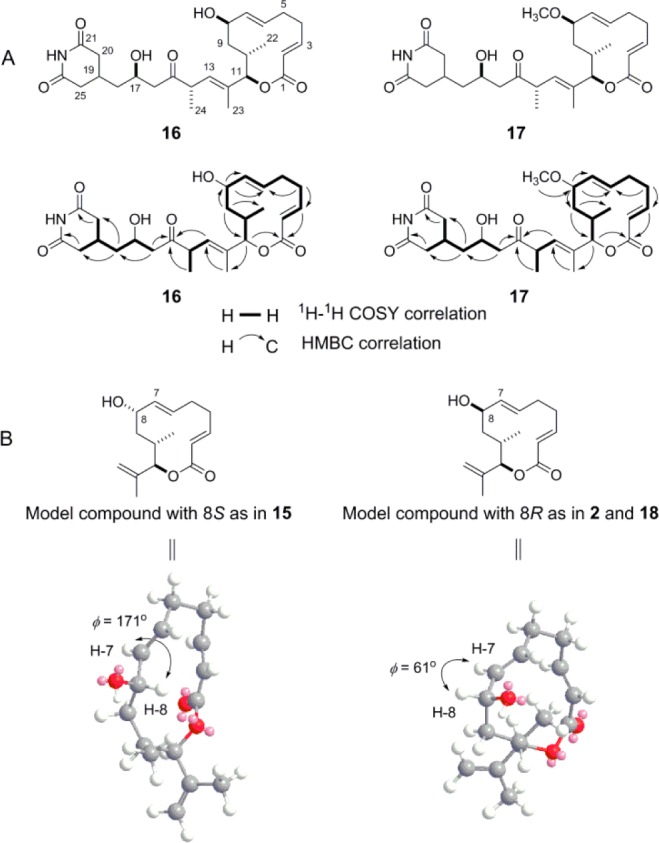

Both 16 and 17 were isolated as colorless oils (Materials and Methods). High-resolution electrospray ionization (HRESI) MS analysis of 16 afforded an [M + Na]+ ion at m/z 498.2461, establishing its molecular formula as C26H37NO7 (calcd [M + Na]+ ion at m/z 498.2466). The 1H, 1H–1H COSY, and 13C NMR spectra of 16 are very similar to those of 15 (Figures S7 and S8 of the Supporting Information),18 except that the signals at δH 5.27 (dd, J = 15.5, 8.0 Hz, H-7), δH 4.45 (m, H-8), and δH 2.15 (m, H-10) in 15 are shifted to δH 5.49 (dd, J = 15.6, 3.8 Hz, H-7), δH 4.14 (m, H-8), and δH 1.79 (m, H-10) in 16, respectively, in the 1H NMR spectrum and that signals at δC 73.4 (C-8) and δC 39.4 (C-9) in 15 are shifted to δC 68.9 (C-8) and δC 42.2 (C-9) in 16, respectively, in the 13C NMR spectrum (Table S3 of the Supporting Information). The correlations of H-8 with C-6, C-7, and C-9 and H-9 with C-8 in the HMBC spectrum of 16 established the hydroxyl group attachment at the C-8 position (Figure 4A). Thus, the only difference between 16 and 15 is the absolute configuration at C-8, and the coupling constant values between H-7 and H-8 are diagnostic in determining the absolute configuration at C-8. These observations agreed well with MM2 energy-minimized configurations for the model 12-membered macrolides with an 8S- or 8R-hydroxyl group, where the dihedral angel (ϕ) for H-7/H-8 is 171° (hence, a large coupling constant) or 61° (hence, a small coupling constant), respectively (Figure 4B). Thus, as exemplified by 15 that contains an 8S-hydroxyl group, the observed H-7/H-8 coupling constant is 8.0 Hz.18 In contrast, for 2 or 17R-hydroxy-8-desmethyl-iso-MGS (18), each of which contains a methoxyl and hydroxyl group at C-8 with an opposite configuration to 15 (Figure 1), the observed H-7/H-8 coupling constant value is 3.5 or 4.0 Hz, respectively.18,28 The observed H-7/H-8 coupling constant in 16 was 3.8 Hz (Table S3 of the Supporting Information), thereby assigning the 8R absolute configuration to 16. Thus, 16 was established as 8,9-dihydro-8R-hydroxy-LTM, and this structure is consistent with MgsK catalyzing the same regio- and stereoselective hydroxylation as it does for 2 and its congeners.28

Figure 4.

Structures of the two novel analogues 8,9-dihydro-8R-hydroxy-LTM (16) and 8,9-dihydro-8R-methoxy-LTM (17). (A) Key 1H–1H COSY and HMBC correlations of 16 and 17 supporting their structural assignments. (B) MM2 energy-minimized configurations of model 12-membered macrolides with an 8S- or 8R-hydroxyl group, depicting the predicted H-7/H-8 dihedral angels that support the 8R absolute configurations for 16 and 17 on the basis of the H-7/H-8 coupling constants.

The structure of 17 was established in a manner similar to that used for 16. Thus, HRESI-MS analysis of 17 afforded an [M + Na]+ ion at m/z 512.2617, establishing its molecular formula as C27H39NO7 (calcd [M + Na]+ ion at m/z 512.2623). The 1H, 1H–1H COSY, and 13C NMR spectra of 17 are very similar to those of 16 (Figures S9 and S10 of the Supporting Information), except that the signals at δH 5.49 (dd, J = 15.6, 3.8 Hz, H-7) and δH 4.14 (m, H-8) in 16 are shifted to δH 5.27 (dd, J = 15.8, 4.4 Hz, H-7) and δH 3.54 (m, H-8) in 17, respectively, in the 1H NMR spectrum and that signals at δC 138.4 (C-7), δC 68.9 (C-8), and δC 42.2 (C-9) in 16 are shifted to δC 134.5 (C-7), δC 78.4 (C-8), and δC 40.7 (C-9) in 17, respectively, in the 13C NMR spectrum (Table S3 of the Supporting Information). Compound 17 also has extra signals attributed to a methyl group at δH 3.29 (s) and δC 56.5. These data indicate that 17 is an O-methylated product at the C-8 hydroxyl group of 16, and the correlations of H-8 with C-6, C-7, and C-9 and H3C-O with C-8 in the HMBC spectrum clearly established the methoxyl attachment at C-8 in 17 (Figure 4A). Finally, 17 was established as 8,9-dihydro-8R-methoxy-LTM, the 8R absolute stereochemistry of which was similarly assigned on the basis of the relatively small H-7/H-8 coupling constant of 4.4 Hz (Table S3 of the Supporting Information).

Cytotoxicity Assay of the Two New Analogues 15 and 16 in Comparison with 1, 2, and Selected Congeners

The SAR emerging from the preliminary screening of a previously constructed glutarimide-containing polyketide library has revealed that (i) 12-membered macrolides, as exemplified by 1 and 2, have more potent cytotoxicity against select cancer cell lines than their 14-membered and ring-open congeners, such as 3 and 4–6, respectively, and (ii) congeners containing a C-17 hydroxyl group are generally more potent than their C-16/C-17 dehydrated or saturated counterparts (Figure 1).20,22 The new analogues 16 and 17, featuring both the 17R-hydroxyl group as in 1 and the 8R-hydroxyl or 8R-methoxyl group as in 2, a combination of functional groups that have not been evaluated previously, presented an opportunity to expand the SAR beyond the natural 1 and 2 congeners. Thus, 16 and 17 were assayed for cytotoxicity against three cancer cell lines, MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, HeLa cervical carcinoma cells, and Jurkat T lymphoma cells, and their activities were compared with the activities of 1, 2, 13, 15, and 18 (Materials and Methods).20,22 The seven compounds are all 12-membered macrolides and, with the exception of 2, all feature the C-17 hydroxyl group yet have varying substitutions at positions C-8 and C-9 (Figure 1).

As summarized in Table 2 (also see Figure S5 of the Supporting Information), while 1 was most potent against all cell lines, compounds 13 and 15–17, which contain 9R-hydroxyl, 8S-hydroxyl, 8R-hydroxyl, and 8R-methoxyl groups, respectively, were more potent than 18, which contains two hydroxyl groups at 8R and 9R, and 2 and 18 were the least potent among all the compounds tested. These findings reinforce the significance of the C-17 hydroxyl group but now reveal new insights into the C-8 and C-9 substitution. (i) While a double bond at C-8 and C-9 as found in 1 is the most potent, a single substitution at C-8 or C-9 such as in 13 and 15–17 retains significant activity, whereas double substitutions at C-8 and C-9 such as in 2 and 18 significantly reduce activity. (ii) While there is no significant difference between C-8 and C-9 substitution as in 16 and 13, the 8S-hydroxyl group, as in 15, appears to be more potent than the 8R-hydroxy counterpart as in 16. (iii) O-Methylation of the 8R-hydroxyl group also increases, albeit modestly, the potency, as in 15 and 16. These findings should facilitate the design, engineering, and preparation of additional analogues of 1 and 2 for anticancer drug discovery and development, and 15 and 17, which have low nanomolar potency on par with that of 1, warrant further mechanistic and in vivo evaluation.

Discussion

LTM (1) is a potent inhibitor of tumor cell migration and eukaryotic protein translation. Cloning and sequencing of the ltm biosynthetic gene cluster from S. amphibiosporus ATCC 53964 revealed that it is highly similar to the mgs gene cluster from S. platensis NRRL 18993 that encode iso-MGS (2) biosynthesis. The ltm cluster consists of nine genes that encode an AT-less type I PKS (LtmBCDEFGHL) for biosynthesis of the nascent glutarmide-containing polyketide intermediate 14 and a post-PKS tailoring enzyme (LtmK) that converts 14 to 1. Inactivation of ltmE or ltmH completely abolished the production of 1, while inactivation of ltmK yielded a mutant strain in which 14 accumulated. Further, the production of 1 can be restored in the ΔltmK mutant by expressing ltmK in trans. These results support a model for 1 biosynthesis that features the LTM AT-less type I PKS that is very similar to the iso-MGS AT-less type I PKS. AT-less type I PKSs harbor unusual domains and PKS architecture and often violate the colinearity rule that is a hallmark for type I PKSs. Comparative studies of the LTM and iso-MGS PKSs now provide an excellent opportunity to probe how AT-less type I PKSs select and control reductive modifications during polyketide chain elongation.

LtmCDEFG consist of the LTM AT-less type I PKS with LtmH acting iteratively in trans to load malonate onto each of the 11 modules (Figure 3A). Although the exact mechanism is not established, the LtmD amidotransferase likely catalyzes the formation of the signature glutarimide moiety by transferring the amine group from glutamine to the LtmC-tethered malonate on the loading module, in a manner akin to that of MgsD,27 SmdH,11 and ChxD.14 After one cycle of elongation by LtmE module-2, the formation of the glutarimide moiety invokes an unusual PKS chemistry, requiring LtmE module-3 to catalyze a Michael addition of the C2 unit to the α,β-unsaturated thioester (Figure 3C). While LtmE module-3 is characterized with a typical KS and an ACP domain, it features the newly discovered B domain.11,14,35,36 Recent structural and biochemical characterization of the KS-B didomain for rhizoxin biosynthesis from Burkholderia rhizoxinica has confirmed their role in a PKS-mediated Michael addition, and the KS-B-ACP domain architecture has been proposed as a hallmark to search for PKS modules that catalyze β-branching in polyketide biosynthesis.36 Previously, this domain has been annotated as an unknown domain in iso-MGS biosynthesis27 and as an X domain in 9-methylstreptimidone biosynthesis.11 On the basis of the recent structural and biochemical evidence of the KS-B domain for rhizoxin biosynthesis, we have now adopted the B domain nomenclature for the glutarimide-containing polyketides.14 The revised proposal for glutarimide biosynthesis sets the stage for characterizing the novel biochemistry in vitro (Figure 3C).

Following the assembly of the glutarimide starter unit, eight additional rounds of extensions catalyzed by PKS modules 4–11 produce the full length LTM polyketide backbone, which is finally cyclized and released as the nascent PKS product 14. Given the structural similarity between 1 and 2 (Figure 1) and the sequence and architectural homology between the LTM and iso-MGS AT-less type I PKSs (Figure 3, Table 1, and Figure S2 of the Supporting Information), it is therefore remarkable that the two PKSs synthesize distinct nascent polyketides, 14 for the LTM type I PKS and 12 and 13 for the iso-MGS type I PKS (Figure 3B and Figure S2C of the Supporting Information). Thus, on the basis of the collinear model for type I PKSs, the LTM PKS would minimally lack a MT domain in module-5, a KR, a DH, and an enoylreductase (ER) domain in module-8, and a KR and ER domain in module-10. In contrast, the iso-MGS PKS would minimally lack a DH domain in module-4, a MT domain in module-5, a KR domain in module-8, and a KR and ER domain in module-10. Intriguingly, while the loading module and modules 2–7 of the LTM and iso-MGS PKSs are essentially identical, the LTM PKS affords a single polyketide product with a hydroxyl group at C-17 and the iso-MGS PKS yields two products, the major one of which features a double bond at C-16 and C-17. There are also distinct domain architectural differences between module-8 and -9 for the LTM and iso-MGS PKSs; however, how these differences account for the structural variations in the resultant polyketide products in 1 and 2 biosynthesis remains unknown (Figure 3A,B and Figure S2B,C of the Supporting Information). AT-less type I PKSs are rich in unusual domains and PKS architecture, and they often violate the colinearity rule most known for type I PKSs.44,45 Comparative studies of the LTM and iso-MGS PKSs, as well as PKSs that direct the biosynthesis of other glutarimide-containing polyketides,1,2,10,11,27,28 should provide opportunities to probe some of these properties, for example, how AT-less type I PKSs select and control reductive modifications during polyketide chain elongation.

Accumulation of 14 as the sole metabolite in SB15002 (Figure 2B, trace V) and restoration of the production of 1 and the two minor metabolites 13 and 15 in SB15003 (Figure 2B, trace VI) suggested that the LtmK P450 enzyme acts as a desaturase that catalyzes regio- and stereospecific desaturation of 14 to 1, with 13 and 15 as minor products (Figure 3B). P450 enzymes that act as desaturases are known, but the majority are associated with liver or lung microsomes that catalyze various metabolic biotransformation events in eukaryotes.46−48 Only a few P450 desaturases of bacterial origin have been described,49−52 for example, CYP102A1 of Bacillus megaterium,49−51 CYP101A1 of Pseudomonas putida,49 and CYP199A4 of Rhodopseudomonas palustris HaA2.52 P450-catalyzed desaturation proceeds via abstraction of hydrogen from the substrate to yield transient free radical intermediates, which undergo elimination of a hydrogen radical to afford the olefin product or recombination with a hydroxyl radical to form the hydroxylated products. Regardless of a prokaryotic or eukaryotic origin, all known examples of P450-catalyzed desaturation are accompanied by hydroxylation, with hydroxylation generally being the major course of the reaction; the P450 desaturases do not convert the hydroxylated products into olefins.53 It is therefore highly significant that, under the fermentation conditions tested, LtmK catalyzes the desaturation of 14 to 1 with minimal formation of the hydroxylated products, 13 and 15 (Figure 3B). Mechanistic and structural characterization of LtmK may therefore reveal new insights into how P450 desaturases control the fate of the initial radical intermediate in partitioning between the elimination and hydroxylation pathways.

Compared to LtmK, the MgsK P450 enzyme in 2 biosynthesis catalyzes the hydroxylation at position C-8, which is further O-methylated by the MgsJ methyltransferase to furnish the methoxyl group found at C-8 in 2. Both MgsK and MgsJ have broad substrate promiscuity, and exploitation of the tailoring steps in 1 and 2 biosynthesis therefore provides an attractive opportunity to engineer novel glutarimide-containing polyketide natural products. Indeed, introduction of mgsK and mgsJK into the ΔltmK mutant strains resulted in the production of two novel analogues 16 and 17, featuring the 17R-hydroxyl group as in 1 and 8R-hydroxyl or 8R-methoxyl group as in 2 (Figure 1C), a combination of structural features not seen in the natural congeners of 1 and 2. Cytotoxicity assays of 16 and 17 against select cancer cell lines, in comparison with those of 1, 2, and specific natural congeners, allowed us to expand the emerging SAR of the glutarimide-containing polyketide family of natural products. Given their fascinating modes of action as inhibitors of tumor cell migration and eukaryotic protein translation and the potent cytotoxicity of 1 and 2 against cancer cell lines, these findings lay the foundation for facilitating the design, development, and preparation of additional analogues of 1 and 2 for anticancer drug discovery and development.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NMR Core facility at The Scripps Research Institute for obtaining 1H and 13C NMR data and the John Innes Center (Norwich, U.K.) for providing the λ-RED-mediated PCR targeting mutagenesis kit.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ACP

acyl carrier protein

- AMT

amidotransferase

- AT-less type I PKS

acyltransferase-less type I polyketide synthase

- B

branching

- DGN

dorrigocin

- DH

dehydratase

- ER

enoylreductase

- GCG

Genetic Computer Group

- GTI-seq

Global Translation Initiation Sequencing

- HRESI-MS

high-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry

- iso-MGS

iso-migrastatin

- KR

ketoreductase

- KS

ketosynthase

- LB

lysogeny broth

- LTM

lactimidomycin

- MGS

migrastatin

- MT

methyltransferase

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- ori-T

origin of transfer

- SAM

S-adenosylmethionine

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- TE

thioesterase

- TSB

tryptic soy broth.

Supporting Information Available

Strains and plasmids (Table S1), summary of the primers used in this study (Table S2), 1H and 13C NMR data for 16 and 17 (Table S3), highlighting of 2 as the true natural product of S. platensis NRRL 18993 and 3 and 4–6 as shunt metabolites of 2 following H2O-mediated ring expansion and ring-opening rearrangements, respectively (Figure S1), a comparison of the biosynthesis of 1 in S. amphibiosporus ATCC 53964 and 2 in S. platensis NRRL 18993 (Figure S2), studies confirming that the cloned ltm cluster directs 1 biosynthesis in S. amphibiosporus ATCC 53964 by gene inactivation of ltmE, ltmH, and ltmK (Figure S3), the construction of the mgsK and mgsJK expression plasmids used to produce 16 and 17 in recombinant strains SB15006 and SB15007 (Figure S4), summary of the cytotoxicity assay data for 16 and 17 against three cancer cell lines in comparison with those of 1, 2, and selected native congeners (Figure S5), and 1H and 13C NMR spectra of 14, 16, and 17 (Figures S6–S10). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Accession Codes

The GenBank accession number for the ltm gene cluster from S. amphibiosporus ATCC 53964 is GQ274954.

Author Present Address

@ J.-W.S.: Biorefinery Research Center, Jeonbuk Branch Institute, Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (KRIBB), 181 Ipsin-gil, Jeongeup, Jeonbuk 580-185, Korea.

Author Present Address

∇ J.J.: South China Sea Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 164 W. Xingang Rd., Guangzhou 510301, China.

Author Present Address

○ S.-K.L.: Research and Development Center, GenoTech Co. Ltd., Daejeon 305-343, Korea.

Author Present Address

● H.J.: College of Life Sciences, Zhejiang University, 866 Yuhangtang Rd., Hangzhou, Zhejiang 310058, China.

Author Present Address

▲ C.Y.: Department of Tumor Biology, The Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, 12902 Magnolia Dr., MRC, Tampa, FL 33612.

Author Contributions

J.-W.S., M.M., and T.K. contributed equally to this work.

This work was supported in part by ThinkPinkKids funds (to J.C.), funds from the State of Florida to The Scripps Research Institute (to J.C. and B.S.), and National Institutes of Health Grant CA106150 (to B.S.).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Ju J.; Lim S. K.; Jiang H.; Seo J. W.; Shen B. (2005) Iso-migrastatin congeners from Streptomyces platensis and generation of a glutarimide polyketide library featuring the dorrigocin, lactimidomycin, migrastatin, and NK30424 scaffolds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 11930–11931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajski S. R.; Shen B. (2010) Multifaceted modes of action for the glutarimide-containing polyketides revealed. ChemBioChem 11, 1951–1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara K.; Nishiyama Y.; Toda S.; Komiyama N.; Hatori M.; Moriyama T.; Sawada Y.; Kamei H.; Konishi M.; Oki T. (1992) Lactimidomycin, a new glutarimide group antibiotic. Production, isolation, structure and biological activity. J. Antibiot. 45, 1433–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakae K.; Yoshimoto Y.; Sawa T.; Homma Y.; Hamada M.; Takeuchi T.; Imoto M. (2000) Migrastatin, a new inhibitor of tumor cell migration from Streptomyces sp. MK929-43F1. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation and biological activities. J. Antibiot. 53, 1130–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura H.; Takahashi Y.; Naganawa H.; Nakae K.; Imoto M.; Shiro M.; Matsumura K.; Watanabe H.; Kitahara T. (2002) Absolute configuration of migrastatin, a novel 14-membered ring macrolide. J. Antibiot. 55, 442–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochlowski J. E.; Whittern D. N.; Hill P.; McAlpine J. B. (1994) Dorrigocins: Novel antifungal antibiotics that change the morphology of ras-transformed NIH/3T3 cells to that of normal cells. II. Isolation and elucidation of structures. J. Antibiot. 47, 870–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadam S.; McAlpine J. B. (1994) Dorrigocins: Novel antifungal antibiotics that change the morphology of ras-transformed NIH/3T3 cells to that of normal cells. III. Biological properties and mechanism of action. J. Antibiot. 47, 875–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo E. J.; Starks C. M.; Carney J. R.; Arslanian R.; Cadapan L.; Zavala S.; Licari P. (2002) Migrastatin and a new compound, isomigrastatin, from Streptomyces platensis. J. Antibiot. 55, 141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayasu Y.; Tsuchiya K.; Aoyama T.; Sukenaga Y. (2001) NK30424A and B, novel inhibitors of lipopolysaccharide-induced tumour necrosis factor α production, produced by Streptomyces sp. NA30424. J. Antibiot. 54, 1111–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen M. S.; Becker A. M.; Rickards R. S. (1976) The glutarimide antibiotic 9-methylstreptimidone: Structure, biogenesis and biological activity. Aust. J. Chem. 29, 673–679. [Google Scholar]

- Wang B.; Song Y.; Luo M.; Chen Q.; Ma J.; Huang H.; Ju J. (2013) Biosynthesis of 9-methylstreptimidone involves a new decarboxylative step for polyketide terminal diene formation. Org. Lett. 15, 1278–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach B. E.; Ford J. H.; Whiffen A. J. (1947) Actidione, an antibiotic from Streptomyces griseus. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 69, 474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S. X.; Yu Z.; Robert F.; Zhao L. X.; Jiang Y.; Duan Y.; Pelletier J.; Shen B. (2011) Cycloheximide and congeners as inhibitors of eukaryotic protein synthesis from endophytic actinomycetes Streptomyces sps. YIM56132 and YIM56141. J. Antibiot. 64, 163–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin M.; Yan Y.; Lohman J. R.; Huang S.-X.; Ma M.; Zhao G.-R.; Xu L.-H.; Xiang W.; Shen B. (2014) Cycloheximide and actiphenol production in Streptomyces sp. YIM56141 governed by single biosynthetic machinery featuring an acyltransferase-less type I polyketide synthase. Org. Lett. 16, 3072–3075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaul C.; Njardarson J. T.; Shan D.; Dorn D. C.; Wu K. D.; Tong W. P.; Huang X. Y.; Moore M. A. S.; Danishefsky S. J. (2004) The migrastatin family: Discovery of potent cell migration inhibitors by chemical synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 11326–11337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan D.; Chen L.; Njardarson J. T.; Gaul C.; Ma X.; Danishefsky S. J.; Huang X. Y. (2005) Synthetic analogues of migrastatin that inhibit mammary tumor metastasis in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 3772–3776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecomte N.; Nijardarson J. T.; Nagorny P.; Yang G.; Downey R.; Ouerfelli O.; Moore M. A. S.; Danishefsky S. J. (2011) Emergence of potent inhibitors of metastasis in lung cancer via syntheses based on migrastatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 15074–15078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju J.; Seo J. W.; Her Y.; Lim S. K.; Shen B. (2007) New lactimidomycin congeners shed insight into lactimidomycin biosynthesis in Streptomyces amphibiosporus. Org. Lett. 9, 5183–5186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju J.; Rajski S. R.; Lim S. K.; Seo J. W.; Peters N. R.; Hoffmann F. M.; Shen B. (2008) Evaluation of new migrastatin and dorrigocin congeners unveils cell migration inhibitors with dramatically improved potency. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 18, 5951–5954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju J.; Rajski S. R.; Lim S. K.; Seo J. W.; Peters N. R.; Hoffmann F. M.; Shen B. (2009) Lactimidomycin, iso-migrastatin and related glutarimide-containing 12-membered macrolides are extremely potent inhibitors of cell migration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 1370–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.; Yang S.; Jakoncic J.; Zhang J.; Huang X. Y. (2010) Migrastatin analogues target fascin to block tumour metastasis. Nature 464, 1062–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider-Poetsch T.; Ju J.; Eyler D. E.; Dang Y.; Bhat S.; Merrick W. C.; Green R.; Shen B.; Liu J. O. (2010) Inhibition of eukaryotic translation elongation by cycloheximide and lactimidomycin. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 209–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.; Liu B.; Lee S.; Huang S. X.; Shen B.; Qian S. B. (2012) Global mapping of translation initiation sites in mammalian cells at single-nucleotide resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, E2424–E2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern-Ginossar N.; Weisburd B.; Michalski A.; Vu T. K. L.; Hein M. Y.; Huang S. X.; Ma M.; Shen B.; Qian S. B.; Hengel H.; Mann M.; Ingolia N. T.; Weissman J. S. (2012) Decoding human cytomegalovirus. Science 338, 1088–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggero D.; Pandolfi P. P. (2003) Does the ribosome translate cancer?. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 179–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju J.; Lim S. K.; Jiang H.; Shen B. (2005) Migrastatin and dorrigocins are shunt metabolites of iso-migrastatin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 1622–1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S. K.; Ju J.; Zazopoulos E.; Jiang H.; Seo J. W.; Chen Y.; Feng Z.; Rajski S. R.; Farnet C. M.; Shen B. (2009) iso-Migrastatin, migrastatin, and dorrigocin production in Streptomyces platensis NRRL 18993 is governed by a single biosynthetic machinery featuring an acyltransferase-less type I polyketide synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 29746–29756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M.; Kwong T.; Lim S. K.; Ju J.; Lohman J. R.; Shen B. (2013) Post-polyketide synthase steps in iso-migrastatin biosynthesis, featuring tailoring enzymes with broad substrate specificity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 2489–2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieser T., Bibb M. J., Buttner M. J., Chater K. F., and Hopwood D. A. (2000) Practical Streptomyces genetics, John Innes Foundation, Norwich, U.K. [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., and Russell D. (2001) Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual, 3rd ed., Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Zazopoulos E.; Huang K. X.; Staffa A.; Liu W.; Bachmann B. O.; Nonaka K.; Ahlert J.; Thorson J. S.; Shen B.; Farnet C. M. (2003) A genomics-guided approach for discovering and expressing cryptic metabolic pathways. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 187–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gust B.; Challis G. L.; Fowler K.; Kieser T.; Chater K. F. (2003) PCR-targeted Streptomyces gene replacement identifies a protein domain needed for biosynthesis of the sesquiterpene soil odor geosmin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 1541–1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen B.; Hutchinson C. R. (1996) Deciphering the mechanism for the assembly of aromatic polyketides by a bacterial polyketide synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 6600–6604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tim M. (1983) Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 65, 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusebauch B.; Busch B.; Scherlach K.; Roth M.; Hertweck C. (2009) Polyketide-chain branching by an enzymatic Michael addition. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 48, 5001–5004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretschneider T.; Heim J. B.; Heine D.; Winkler R.; Busch B.; Kusebauch B.; Stehle T.; Zocher G.; Hertweck C. (2013) Vinylogous chain branching catalyzed by a dedicated polyketide synthase module. Nature 502, 124–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heathcote M. L.; Staunton J.; Leadlay P. F. (2001) Role of type II thioesterases: Evidence for removal of short acyl chains produced by aberrant decarboxylation of chain extender units. Chem. Biol. 8, 207–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claxton H. B.; Akey D. L.; Siler M. K.; Admiraal S. J.; Smith J. L. (2009) Structure and functional analysis of RifR, the type II thioesterase from the rifamycin biosynthetic pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 5021–5029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machida K.; Arisawa A.; Takeda S.; Tsuchida T.; Aritoku Y.; Yoshida M.; Ikeda H. (2008) Organization of the biosynthetic gene cluster for the polyketide antitumor macrolide, pladienolide, in Streptomyces platensis Mer-11107. Biosci., Biotechnol., Biochem. 72, 2946–2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungmann V.; Molnar I.; Hammer P. E.; Hill D. S.; Zirkle R.; Buckel T. G.; Buckel D.; Ligon J. A.; Pachlatko J. P. (2005) Biocatalytic conversion of avermectin to 4″-oxo-avermectin: Characterization of biocatalytically active bacterial strains and of cytochrome P450 monooxygenase enzymes and their genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 6968–6976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez C.; Du L.; Edwards D. J.; Toney M. D.; Shen B. (2001) Cloning and characterization of a phosphopantetheinyl transferase from Streptomyces verticillus ATCC15003, the producer of the hybrid peptide-polyketide antitumor drug bleomycin. Chem. Biol. 8, 725–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman K. J.; Hong H.; Oliynyk M.; Siskos A. P.; Leadlay P. F. (2004) Identification of a phosphopantetheinyl transferase for erythromycin biosynthesis in Saccharopolyspora erythraea. ChemBioChem 5, 116–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brautaset T.; Sekurova O. N.; Sletta H.; Ellingsen T. E.; Strom A. R.; Valla S.; Zotchev S. B. (2000) Biosynthesis of the polyene antifungal antibiotic nystatin in Streptomyces noursei ATCC 11455: Analysis of the gene cluster and deduction of the biosynthetic pathway. Chem. Biol. 7, 395–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen B. (2003) Polyketide biosynthesis beyond the type I, II and III polyketide synthase paradigms. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 7, 285–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piel J. (2010) Biosynthesis of polyketides by trans-AT polyketide synthase. Nat. Prod. Rep. 27, 996–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettie A. E.; Rettenmeier A. W.; Howald W. N.; Baillie T. A. (1987) Cytochrome P450 catalyzed formation of delta 4-VPA, a toxic metabolite of valproic acid. Science 235, 890–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H.; Ehlhardt W. J.; Kulanthaivel P.; Lanza D. L.; Reilly C. A.; Yost G. S. (2007) Dehydrogenation of indoline by cytochrome P450 enzymes: A novel “aromatase” process. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 322, 843–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaz A. D.; Kessell K. J.; Coon M. J. (1994) Aromatization of a bicyclic steroid analog, 3-oxodecalin-4-ene-10-carboxaldehyde, by liver microsomal cytochrome P450 2B4. Biochemistry 33, 13651–13661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y.; He X.; Ortiz de Montellano P. R. (2006) Radical intermediates in the catalytic oxidation of hydrocarbons by bacterial and human cytochrome P450 enzymes. Biochemistry 45, 533–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Nardo G.; Fantuzzi A.; Sideri A.; Panicco P.; Sassone C.; Giunta C.; Gilardi G. (2007) Wild-type CYP102A1 as a biocatalyst: Turnover of drugs usually metabolized by human liver enzymes. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 12, 313–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse C. J.; Bell S. G.; Wong L. L. (2008) Desaturation of alkylbenzenes by cytochrome P450 (BM3). Chem.—Eur. J. 14, 10905–10908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell S. G.; Zhou R.; Yang W.; Tan A. B.; Gentleman A. S.; Wong L. L.; Zhou W. (2012) Investigation of the substrate range of CYP199A4: Modification of the partition between hydroxylation and desaturation activities by substrate and protein engineering. Chem.—Eur. J. 18, 16677–16688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guengerich F. P. (2001) Common and uncommon cytochrome P450 reactions related to metabolism and chemical toxicity. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 14, 611–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.