Abstract

Objectives

To present estimates of clinically meaningful or minimal important changes for the Oxford Hip Score (OHS) and the Oxford Knee Score (OKS) after joint replacement surgery.

Study Design and Setting

Secondary data analysis of the NHS patient-reported outcome measures data set that included 82,415 patients listed for hip replacement surgery and 94,015 patients listed for knee replacement surgery was performed.

Results

Anchor-based methods revealed that meaningful change indices at the group level [minimal important change (MIC)], for example in cohort studies, were ∼11 points for the OHS and ∼9 points for the OKS. For assessment of individual patients, receiver operating characteristic analysis produced MICs of 8 and 7 points for OHS and OKS, respectively. Additionally, the between group minimal important difference (MID), which allows the estimation of a clinically relevant difference in change scores from baseline when comparing two groups, that is, for clinical trials, was estimated to be ∼5 points for both the OKS and the OHS. The distribution-based minimal detectable change (MDC90) estimates for the OKS and OHS were 4 and 5 points, respectively.

Conclusion

This study has produced and discussed estimates of minimal important change/difference for the OKS/OHS. These estimates should be used in the power calculations and the interpretation of studies using the OKS and OHS. The MDC90 (∼4 points OKS and ∼5 points OHS) represents the smallest possible detectable change for each of these instruments, thus indicating that any lower value would fall within measurement error.

Keywords: Minimal important change, Minimal important difference, Hip replacement, Knee replacement, Responder definition, Study designs

1. Introduction

What is new?

-

•

An array of values representing clinically meaningful changes has been provided for the Oxford Knee Score (OKS) and the Oxford hip Score (OHS).

-

•

This study builds on a previous study that provided only minimal important difference (MID) values for the OKS/OHS (which were based on a much smaller sample) and provides and discusses an array of minimal important change/MID values.

-

•

The results of this study will enable researchers and clinicians to better interpret changes in the OKS and OHS, after joint replacement surgery both in the research setting and in the clinical practice.

The Oxford hip and knee scores are widely used patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in research, audit, and clinical practice. In addition to their appropriate development, PROMs used in the context of arthroplasty should have well-established measurement properties, assessed in that context, such as evidence of validity, reliability, and responsiveness. It is also important that scores are interpretable, that is, that qualitative meaning can be assigned to a particular quantitative score or to a difference or change in the score [1]. Determining whether statistically significant changes in the Oxford Hip Score (OHS) and the Oxford Knee Score (OKS) are also clinically meaningful is essential for judging the efficacy of joint replacement. Such interpretation is needed for assessing change in single groups of patients over time (ie, cohort studies), for differences between groups (ie, clinical trials) and for assessing changes in individual patients. Individual patient-level assessment is important as clinicians (and patients) increasingly use individual PROM scores for personal decision making. This might involve identification of appropriate timing of an intervention or assessment of progress and/or deterioration after intervention or delay in treatment (such as hip replacement).

Two different approaches can be used to estimate and interpret the smallest amount of change in a score that could be considered to have clinical importance [2]. These are commonly termed as “anchor-based” or “distribution-based” methods [3].

Anchor-based methods explore how an observed change or difference in the score on the instrument relates to an external criterion or relevant anchor (eg, responses on a global transition item). The anchor can be rated or set by the patient, clinician, or other stakeholder. Anchor-based methods are, by definition, more likely to be clinically relevant as they relate the score or changes in the score to a clinically meaningful reference measure (a little better, about the same, and so forth). Anchor-based methods can provide information at both group and individual levels. For example, a hypothesis may explore (1) the change in health status in a single group or a single individual over time [often referred to as the minimal important change (MIC)] or (2) the difference in health gain or loss between two independent groups of patients [the minimal important difference (MID)].

Distribution-based methods are based on the statistical characteristics of the sample in a particular study [2], [3], [4]. The observed change is expressed as a standardized metric with examples including the effect size (ES), the standard error of measurement (SEM), and the minimal detectable change (MDC). Apart from the ES, which is normally applied to comparisons between groups, distribution-based measures can provide information at an individual patient level. For example, the MDC is the smallest change, for an individual, that is likely to be beyond the measurement error of the instrument and therefore to represent a true change.

It is acknowledged that these definitions and their use can cause confusion [3], [4], and in the literature, several terms are often used interchangeably.

In this article, we calculate and describe estimates of meaningful change and difference for the Oxford hip and knee scores and discuss how they should be used.

2. Materials and methods

An analysis of the NHS PROMS data set of all hip and knee replacements undertaken from January 1, 2009, to December 31, 2011, in England and Wales was performed. Full PROMs data reports and methodology guides can be found online [5].

2.1. Subjects and/or assessments

As a part of the NHS PROMS program, patients who were listed for primary joint replacement surgery completed a set of preoperative questionnaires including the OHS or the OKS. The OHS and the OKS are both 12-item questionnaires that address pain and functional disability in relationship to the patient's hip or knee problems, respectively. Items were originally devised using interviews with patients undergoing joint replacement surgery, so that they would reflect the patient's perspective. In each case, item responses have five categories and are Likert scaled. The original scoring system was from 1 to 5, with a summary score ranging from 12 (best) to 60 (worst). The recommended scoring system has since changed with items now scored from 0 to 4, with a summary score range of 0 (worst) to 48 (best) [6]. Although both questionnaires contain the same number of items and are scored similarly, their scales are not equivalent to each other (ie, a score of 10 on the OHS cannot be assumed to represent the same level of severity as a score of 10 on the OKS).

At 6 months after surgery, the measures were repeated and patients also completed a global transition item (“overall, how are your <hip/knee> problems now, compared to before your operation?”) with five response categories: “much better” (scored 1), “a little better” (2), “about the same” (3), “a little worse” (4), and “much worse” (5).

2.2. Statistical methods

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Change scores followed a normal distribution, which allowed the use of parametric statistics. Change-related parameters for group-level estimates were examined using both anchor- and distribution-based methods.

2.2.1. Anchor-based method

Initially, the appropriateness of the anchor item to record change in the OKS and OHS was first assessed by examining the correlations between the anchor item and the change and postoperative OHS/OKS scores. Directionality of the association between the transition item and the scores was tested using an analysis of variance with a test for linear trend.

2.2.1.1. Minimally important change

Clinically relevant change (improvement or deterioration) in health status over time in a single group was assessed using the MIC. This value was calculated as the mean change in the OKS and the OHS in patients who identified themselves to be “a little better” on the patient-reported global transition item (anchor).

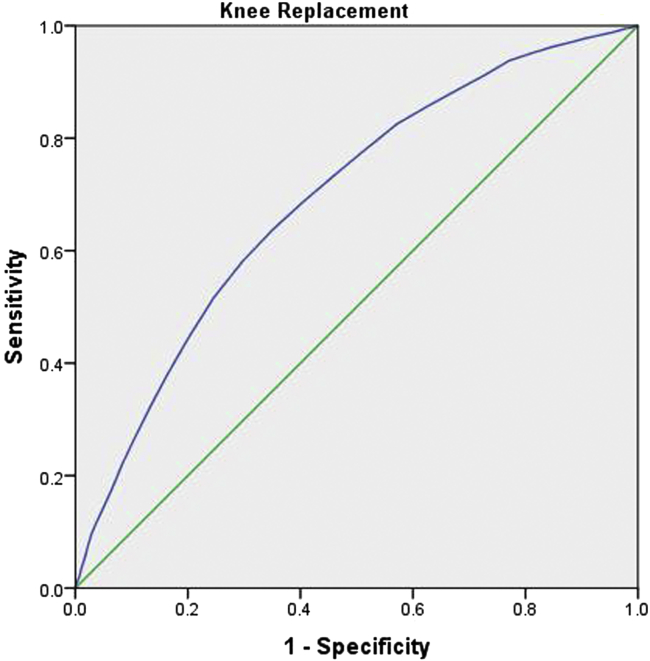

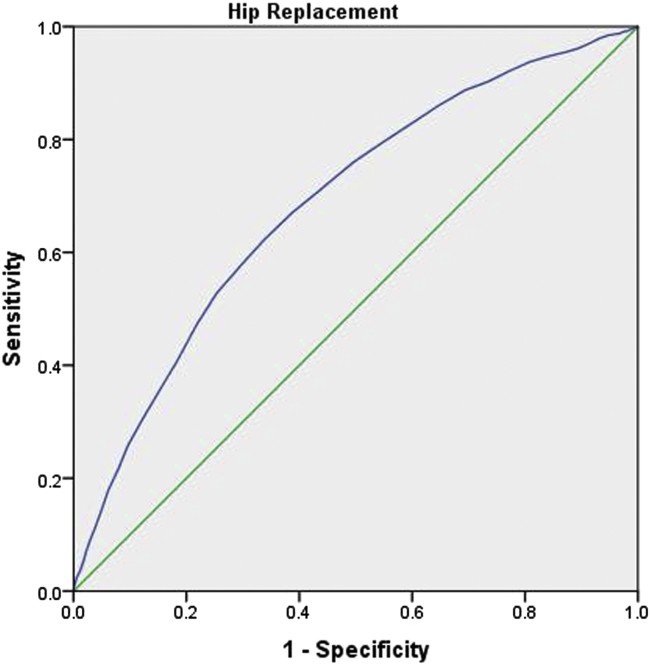

Although the MIC is most often applied to group-level (aggregated scores) data, clinically relevant change in health status over time in an individual patient was also estimated using an anchor-based method but in this instance using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. The ROC method calculates the probability of correctly identifying patients based on an external anchor. Furthermore, ROC curves plot sensitivity (y-axis) against 1−specificity (x-axis) for all possible cutoff points of the instrument's change score and relate this to the probability of detecting improvement, as judged by the external anchor [7]. The individual-level MIC was calculated by performing the ROC analysis to differentiate between two groups of patients: those who did and did not experience important clinical change. These were patients who responded that they were “a little better” versus “the same,” respectively. The most efficient cutoff value, with regard to specificity and sensitivity, is associated with the point closest to the top left hand corner of the ROC curve. Because the best-cut point “cuts” or differentiates at the boundary between improvement and no change, the best-cut point would be expected to be lower than the value (the MIC) reported by all subjects in the “a little better” group [8]. ROC curves were also used to assess the diagnostic ability of the OHS and OKS to detect change. The area under the curve (AUC) represents the diagnostic ability of an instrument, with a value of 0.5 denoting performance no better than random chance and a value of 1.0 indicating perfect predictive ability [9].

2.2.1.2. Minimally important difference

Comparison of clinically relevant difference in health status change between groups was assessed with a value representing the minimal important difference (MID). This value was calculated as the difference in the mean change of the OHS and OKS in patients who identified themselves to be “a little better” and “about the same” on the patient-reported global transition item (anchor).

2.2.2. Distribution-based method

2.2.2.1. Minimal detectable change

A distribution-based method was used to calculate the MDC. The MDC is the value representing the lowest change score that can be considered beyond the measurement error of the instrument (at the individual patient level). The MDC is the lower bound of real change, although it may not indicate clinical significance.

This method is based on the SEM, the range within which a person's true score may fall, which is estimated as SEM = standard deviation (SD) × √(1 − test–retest reliability). The MDC is then calculated by multiplying the SEM by √2 (to account for error that is introduced on the two occasions that the test is completed, to measure change) [10], and the z value representing the desired confidence level of the error-induced uncertainty of the observed score [11] (eg, 1.65 for 90% confidence level).

3. Results

3.1. Study population characteristics

At baseline, 137,109 patients who underwent hip replacement surgery were recruited, of which 84,371 (61.5%) had completed both preoperative and postoperative OHS, with 82,415 (98.9%) of those completing the global transition item. Of 156,788 patients who underwent knee replacements, 94,502 (60.3%) had completed both preoperative and postoperative OKS, with 94,015 (99.5%) of those completing the global transition item. Of the patients who underwent hip replacement and knee replacement, 58.3% and 55.5%, respectively, were female. Patients who completed the postoperative OHS had, on average, 1.64 (SE, 0.048; P < 0.001) points higher baseline OHS than the group of patients who did not return the postoperative OHS, and patients who completed the postoperative OKS had 1.43 (SE, 0.042; P < 0.001) points higher preoperative OKS than the patients who did not return the postoperative questionnaires.

3.2. Assessment of minimal change

The mean preoperative and 6 month postoperative absolute scores, change scores, and ESs for the OHS and OKS (with SDs) are shown in Table 1. ESs were large (>0.8) and mean changes were statistically significant (P < 0.001) for both the OHS and the OKS.

Table 1.

Mean preoperative and 6 month postoperative change scores and effect sizes for the OHS and the OKS

| Statistic | OHS | OKS |

|---|---|---|

| Preoperative mean (SD) | 17.68 (8.50) | 18.47 (7.95) |

| Postoperative mean (SD) | 37.98 (9.56) | 33.75 (10.24) |

| Mean change (SD) | 19.70 (10.36) | 14.74 (10.02) |

| Effect size | 2.32 | 1.85 |

Abbreviations: OHS, Oxford Hip Score; OKS, Oxford Knee Score; SD, standard deviation.

All changes were significant (paired t test, at P ≤0.001).

3.3. Anchor-based methods

The Pearson correlation coefficients for the association between OHS and OKS change scores and the global transition item were 0.52 and 0.61 and 0.65 and 0.67 for the correlations between the anchor and the postoperative OHS and OKS, respectively.

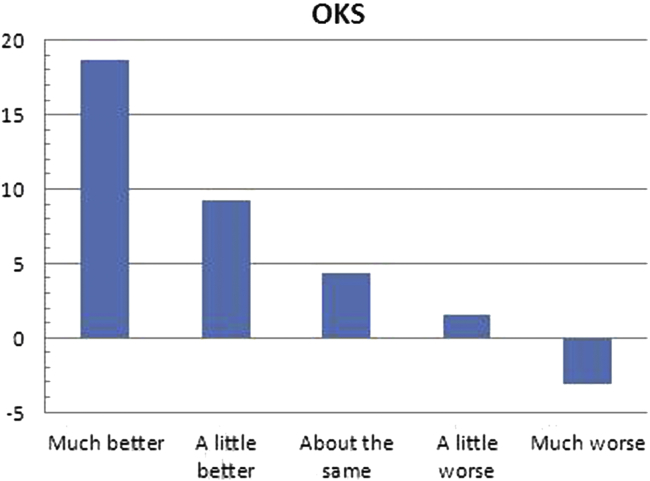

Percentages of responses for different response categories, ESs, and mean score changes by response category are presented in Table 2. There is a linear trend (however, disproportional for improvement and worsening) between perceived change measured with the global transition item and the ESs. Fig. 1 demonstrates this relationship for the OKS.

Table 2.

Number and percentages of responses on the global transition item for different response categories, with effect sizes, mean score changes by response category, and ANOVA tests for linear trend for the OHS and the OKS

| Measure/Statistic | Much better | A little better | About the same | A little worse | Much worse |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OHS | |||||

| Percentage of responses | 69,328 (84) | 8,340 (10) | 2,286 (3) | 1,404 (2) | 1,057 (1) |

| Mean change (SD) | 21.99 (8.884) | 10.63 (7.986) | 5.41 (7.918) | 2.19 (7.663) | −3.58 (8.587) |

| Effect size | 2.6 | 1.25 | 0.69 | 0.26 | −0.45 |

| P-value for linear trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| OKS | |||||

| Percentage of responses | 65,086 (69) | 16,901 (18) | 5,279 (6) | 3,819 (4) | 2,930 (3) |

| Mean change (SD) | 18.64 (8.146) | 9.22 (7.187) | 4.38 (6.848) | 1.53 (6.712) | −3.18 (6.726) |

| Effect size | 2.4 | 1.18 | 0.56 | 0.2 | −0.4 |

| P-value for linear trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: OHS, oxford hip score; OKS, oxford knee score; SD, standard deviation.

Fig. 1.

Mean OKS change by response category on the global transition item. OKS, Oxford Knee Score.

3.3.1. Minimally important change estimate applicable for single group over time (eg, cohort studies)

The MIC or average score change associated with the response “a little better” on the global transition item was ∼11points for the OHS and ∼9 points for the OKS. Patients who reported themselves to be “a little worse” actually demonstrated an improvement (∼2 points) on both the OHS and OKS (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of estimates for meaningful change for the OHS and the OKS

| Measure | MIC |

MID (group) | MDC90 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual-level MIC (ROC analysis) |

Group-level MIC | ||||||

| BCP | AUC (95% CI) | 1 − specificity | Sensitivity | ||||

| OKS | 6.5 | 0.692 (0.684, 0.700) | 0.351 | 0.638 | 9.22 | 4.84 | ±4.15 |

| OHS | 7.5 | 0.687 (0.674, 0.699) | 0.339 | 0.624 | 10.63 | 5.22 | ±4.85 |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; BCP, best-cut point; CI, confidence interval; OHS, oxford hip score; OKS, oxford knee score; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Minimal important change (MIC) and minimal important difference (MID) were calculated by anchor-based methods. Minimal detectable change (MDC90) was calculated by distribution-based methods.

3.3.2. Minimally important change estimate applicable for assessment of individual patients

For the individual-level MIC, the ROC analysis demonstrated that the AUCs for the change OKS/OHS in distinguishing between the groups of patients “a little better” and “about the same” were 0.7. For the OHS, the optimum threshold was 7.5 points (sensitivity, 0.6; 1 − specificity, 0.3). For the OKS, the optimum threshold was 6.5 (sensitivity, 0.6; 1 − specificity, 0.4).

Table 3 and Fig. 2, Fig. 3 also summarize the characteristics of ROC curves for the OHS and the OKS MIC. The point closest to the top left corner (the best-cut point) was close to the MIC, for both the OHS and the OKS.

Fig. 2.

ROC curve for the OKS.

Fig. 3.

ROC curve for the OHS.

3.3.3. Minimally important difference estimate applicable for group comparisons (eg, clinical trials, case–control studies)

The MID or average score difference between the response categories “a little better” and “about the same” was ∼5 points for both OHS and OKS (Table 3).

3.4. Distribution-based methods

3.4.1. Minimal detectable change

The MDC90 values are provided in Table 3. The MDC90 values provided can be interpreted to mean that in 90% of the cases, patients will have experienced real change (beyond measurement error) if their score has changed by at least 4.85 points on the OHS or by 4.15 points on the OKS in either direction.

4. Discussion

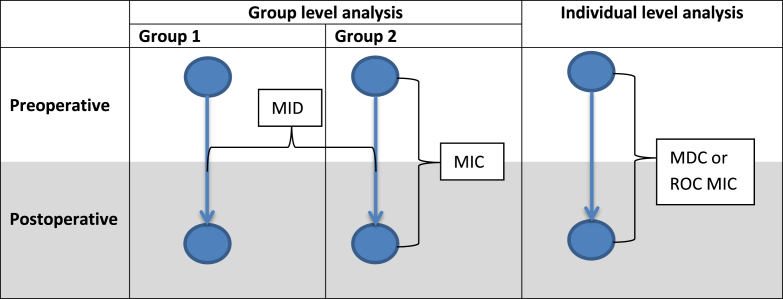

Our work has shown that the MICs for the OHS and OKS, at a group level, are about 11 points and 9 points (respectively). The corresponding group MID values are about 5 points both for OHS and for OKS. When used at an individual level (MIC from ROC analysis), any change in the OHS and OKS beyond 8 and 7 points (respectively) can be considered as a “clinically relevant” change. Finally, any change beyond 5 and 4 (respectively) can be considered as a “real” change (above measurement error—the MDC). A schema for the suggested use of these values is presented in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Taxonomy for determining and using meaningful changes following hip or knee replacement surgery. MDC, minimal detectable change; MIC, minimal important change; MID, minimal important difference; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Some estimates of minimal change have previously been reported for the OKS. Browne et al. [12] have reported MID values only for the OKS and the OHS (3.8 points and 8.4 points, respectively). The difference in estimates between Browne et al. and those reported in this present study could be explained by the smaller sample sizes used in the former study (eg, only five patients were used to identify those who were “a little worse”). That said, the values reported by Browne et al. are not substantially dissimilar and although this present work offers greater precision because of the greater sample size, a working MID of between 4 and 8 points would not be considered wildly inaccurate [13].

In terms of interpretation and use, some examples may help. The smallest detectable change possible (or limit of the instrument) is the MDC90 − 5 points for the OHS and 4 points for the OKS. Any conclusions regarding change below these levels (changes of less than 4 points) should be viewed with suspicion—the instrument is simply unable to discriminate. The MDC90 could indeed be used to identify the smallest clinically important change for an individual patient (being that it reflects the smallest detectable change in the score for any use). However, a more suitable metric for this purpose is the MIC as derived by the anchor-based ROC method. From ROC curves, the best-cut point reveals values of 7 and 8 points for the OKS and OHS, respectively. Using an example, a patient improving over time from 30 to 36 points (on either hip or knee score), may have achieved the amount of change that is beyond measurement error, but this may still not represent a clinically meaningful improvement. On the other hand, a patient changing from 30 to 39 points can be considered as truly improved (beyond measurement error AND meaningful). However, caution must be exercised when using the MIC ROC at the individual level. The AUC value of 0.7 is the lowest limit for accepting the usefulness of any threshold for diagnostic purposes.

Moving away from individual measurement and toward population or group-based assessment (MIC and MID for groups), similar examples can be given. For example, in a study examining the effect of knee replacement in a single cohort (with baseline measures and longitudinal follow-up), it is the MIC that will be of most interest. However, it would require a mean change score of at least 11 points (OHS) or 9 points (OKS) to demonstrate a true clinical change over time. Finally, if the study were a comparative study between two groups (ie, in a clinical trial), then the MID is of most interest, both for establishing a priori sample size and for interpreting any a posteri differences between groups. In this instance, a difference of 5 points (for either OKS or OHS) would demonstrate a true clinical difference between groups.

4.1. Study considerations and limitations

Although these values are the best current estimates for meaningful clinical difference/change for these Oxford scores (OHS and OKS), it should be remembered that there remains some disagreement on which method should be used for estimate derivation [1], [14], [15]. Therefore, caution should be exercised before discarding or discrediting values calculated using other methods at the present time.

Another concern is the apparent low proportion of responses. There were very small, but significant, baseline score differences between the groups of patients who did and did not complete a postoperative OKS or OHS. Whether there are differences in postoperative outcomes between the respondents and nonrespondents at the follow-up stage is not known [16]. However, we consider the issue to have little impact; the relation between anchor and change scores on the OHS/OKS is likely to be the same in the respondents and nonrespondents.

Other points are worthy of comment. It should be appreciated that there is a lack of symmetry in the relationship of the OHS and OKS change scores with the global transition item. Some patients considered themselves to be “much worse” on the anchor question yet showed only modest deterioration on their Oxford score (Fig. 1; although the OKS is shown for illustration purposes, the phenomenon was the same for the OHS). Similarly, patients who considered themselves to be “a little worse” or “about the same” actually experienced small (∼0.2 ES) and medium (∼0.6 ES) levels of improvement, respectively. This observation was unexpected and certainly of interest, but its impact on these results is beyond the scope of this article and a topic for further research.

Another concern relating to the anchor-based method is that the anchor item was more correlated to the postoperative score than the change score. This has also been demonstrated in some previous studies, and it raises concerns over the validity of the anchor [17], [18]. Response shift and the implicit theory of change are the two most dominant theories that have been put forward to explain this phenomenon [19].

On a more general note, we should also highlight the fact that the MIC/MID values are not a fixed attribute of a measure but are (in common with other attributes of health status measures) dependent on the study design, timing of the assessment, and the purpose to which the instrument(s) have been applied [7], [20]. In our study, a patient-reported transition item asking about the perceived change, with five response categories, was used as an anchor. If instead, changes on the OHS and OKS had been related to a global item asking about the importance of any change experienced or about patients' satisfaction with the outcome, different values representing the anchor-based MICs/MIDs would very likely have been obtained. Also, the small amount of change that some individuals perceive as noteworthy might be considered trivial/unimportant by many.

4.1.1. Implications of the findings and future directions

This is the first time that detailed MIC/MID values have been reported for the OKS and OHS based on such a large study sample. After taking account of the aforementioned concerns using the MIC/MID on a group level, the values presented in this study can be used to classify meaningful clinical change. Those planning future trials should use the appropriate MIC/MID value, particularly for randomized controlled trials. Assessment of individual change should probably be performed using the values obtained by ROC analysis in line with FDA recommendations [7] although a priori responder definitions using distribution-based methods (such as the MDC) could also be used as a lower bound of meaningful change.

Although this study, using a specific methodology, has provided great detail and precision in calculating MIC and MID values for the OKS and OHS (and we would recommend using these whenever possible), there may be an argument for accepting the apparent convergence toward a five-point “rule of thumb” for the OKS and OHS. Indeed, the review work conducted and reported by Norman et al. in 2003 has highlighted that the “half a standard deviation” rule still holds in the majority of cases seeking to delineate clinical significance. The inability to discriminate beyond seven categories, the suggested “channel capacity” of the human mind, has been put forward as a potential reason. This equates to nearly one-half of an SD (0.46). Although the move toward increased sophistication and greater precision of MIC/MIDs is mostly welcomed, an appreciation of the potential reduction to a simpler construct is helpful on two fronts: (1) it allows us to continue to confer credibility on studies that have had sample sizes and ESs calculated using the “0.5 SD” method and (2) it may be easier for certain groups to work with the rule of thumb “0.5 SD” method rather than the more complex concepts and structure outlined in this article.

The challenges we encountered in this study highlight the need for further development and for consensus to be reached on the most appropriate methodology to be used in estimating anchor-based MICs/MIDs. It is likely that these methods will evolve further, and (hopefully) an international consensus on the “best practice” in calculating MIDs/MICs will be reached. It is possible that recommendations from this article may therefore change in the future.

5. Conclusion

Meaningful clinical significance values have been estimated for the Oxford hip and knee scores. The measurement error or the smallest detectable change for the OKS and OHS is 4 and 5 points, respectively. To measure change in an individual patient, the MIC (ROC method) should be used and is 7 and 8 points for OKS and OHS, respectively. To assess change over time in a single group of patients, the MIC should be used and is 9 points for the OKS and 10 points for the OHS. To assess the difference between groups, the MID can be used and is 5 points for both OKS and OHS.

Acknowledgments

A copy of the OHS and OKS questionnaires and permission to use these measures can be acquired from Isis Innovation Ltd, the technology transfer company of the University of Oxford via the Web site http://www.isis-innovation.com/outcomes/index.html or e-mail healthoutcomes@isis.ox.ac.uk.

Footnotes

K.H. and D.J.B. contributed equally to this work and should be regarded as joint first authors.

Conflict of interest: J.D. is one of the original inventors of the Oxford Hip Score and Oxford Knee Score. She has received consultancy payments, via Isis Innovation, in relation to work involving both questionnaires. The other authors have no conflicts of interest.

Funding: This work was supported under the general program of research undertaken by the Nuffield Department of Orthopedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences as a National Institute of Health Research Biomedical Research Unit- Musculoskeletal Disease.

References

- 1.Mokkink L.B., Terwee C.B., Patrick D.L., Alonso J., Stratford P.W., Knol D.L. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:737–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dawson J., Boller I., Doll H., Lavis G., Sharp R., Cooke P. Minimally important change was estimated for the Manchester–Oxford Foot Questionnaire after foot/ankle surgery. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:697–705. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crosby R.D., Kolotkin R.L., Williams G.R. Defining clinically meaningful change in health-related quality of life. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:395–407. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lydick E., Epstein R. Interpretation of quality of life changes. Qual Life Res. 1993;2:221–226. doi: 10.1007/BF00435226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NHS Information Centre. HES Online. 2012. Available at http://www.hesonline.nhs.uk/Ease/servlet/ContentServer?siteID=1937&categoryID=1295. Accessed August 13, 2013.

- 6.Murray D., Fitzpatrick R., Rogers K., Pandit H., Beard D., Carr A. The use of the Oxford hip and knee scores. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(8):1010–1014. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B8.19424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. 2009.

- 8.Deyo R.A., Centor R.M. Assessing the responsiveness of functional scales to clinical change: an analogy to diagnostic test performance. J Chronic Dis. 1986;39(11):897–906. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(86)90038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanley J.A., McNeil B.J. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green B.F. A primer of testing. Am Psychol. 1981;36(10):1001. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beckerman H., Roebroeck M., Lankhorst G., Becher J., Bezemer P., Verbeek A. Smallest real difference, a link between reproducibility and responsiveness. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:571–578. doi: 10.1023/a:1013138911638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Browne J.P., van der Meulen J.H., Lewsey J.D., Lamping D.L., Black N. Mathematical coupling may account for the association between baseline severity and minimally important difference values. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:865–874. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Browne J., Jamieson L., Lewsey J., van der Meulen J., Black N., Cairns J. Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) in elective surgery. Rep Department Health. 2007:12. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Revicki D., Hays R.D., Cella D., Sloan J. Recommended methods for determining responsiveness and minimally important differences for patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King M.T. A point of minimal important difference (MID): a critique of terminology and methods. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;11(2):171–184. doi: 10.1586/erp.11.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hutchings A., Frie K.G., Neuburger J., van der Meulen J., Black N. Late response to patient-reported outcome questionnaires after surgery was associated with worse outcome. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;66 doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cella D., Hahn E.A., Dineen K. Meaningful change in cancer-specific quality of life scores: differences between improvement and worsening. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:207–221. doi: 10.1023/a:1015276414526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wyrwich K.W., Tardino V.M. Understanding global transition assessments. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:995–1004. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-0050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norman G. Hi! How are you? Response shift, implicit theories and differing epistemologies. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:239–249. doi: 10.1023/a:1023211129926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beaton D.E., Boers M., Wells G.A. Many faces of the minimal clinically important difference (MCID): a literature review and directions for future research. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2002;14(2):109. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200203000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]