Abstract

The G-protein coupled inwardly rectifying potassium (GIRK, or Kir3) channels are important mediators of inhibitory neurotransmission via activation of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs). GIRK channels are tetramers comprising combinations of subunits (GIRK1–4), activated by direct binding of the Gβγ subunit of Gi/o proteins. Heterologously expressed GIRK1/2 exhibit high, Gβγ-dependent basal currents (Ibasal) and a modest activation by GPCR or coexpressed Gβγ. Inversely, the GIRK2 homotetramers exhibit low Ibasal and strong activation by Gβγ. The high Ibasal of GIRK1 seems to be associated with its unique distal C terminus (G1-dCT), which is not present in the other subunits. We investigated the role of G1-dCT using electrophysiological and fluorescence assays in Xenopus laevis oocytes and protein interaction assays. We show that expression of GIRK1/2 increases the plasma membrane level of coexpressed Gβγ (a phenomenon we term ‘Gβγ recruitment’) but not of coexpressed Gαi3. All GIRK1-containing channels, but not GIRK2 homomers, recruited Gβγ to the plasma membrane. In biochemical assays, truncation of G1-dCT reduces the binding between the cytosolic parts of GIRK1 and Gβγ, but not Gαi3. Nevertheless, the truncation of G1-dCT does not impair activation by Gβγ. In fluorescently labelled homotetrameric GIRK1 channels and in the heterotetrameric GIRK1/2 channel, the truncation of G1-dCT abolishes Gβγ recruitment and decreases Ibasal. Thus, we conclude that G1-dCT carries an essential role in Gβγ recruitment by GIRK1 and, consequently, in determining its high basal activity. Our results indicate that G1-dCT is a crucial part of a Gβγ anchoring site of GIRK1-containing channels, spatially and functionally distinct from the site of channel activation by Gβγ.

Key Points

The G-protein coupled inwardly rectifying potassium (GIRK) channel is an important mediator of neurotransmission via Gβγ subunit of the heterotrimeric Gi/o protein released by G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) activation.

Channels containing the GIRK1 subunit exhibit high basal currents, whereas channels that are formed by the GIRK2 subunit have very low basal currents.

GIRK1-containing channels, but not channels consisting of GIRK2 only, recruit Gβγ to the plasma membrane. The Gα subunit of the G protein is not recruited by either GIRK1/2 or GIRK2.

The unique distal C terminus of GIRK1 (G1-dCT) endows the channel with strong interaction with Gβγ, and deletion of G1-dCT abolishes the Gβγ recruitment and reduces the basal currents.

These findings suggest that the basal activity of GIRK channels depends on channel-induced recruitment of Gβγ. The unique C terminus of GIRK1 subunit plays an important role in Gβγ recruitment.

Introduction

The G protein-gated inward rectifying K+ (GIRK, or Kir3) channels are major mediators of inhibitory neurotransmitters that activate G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). GIRK channels are involved in alcohol and drug addiction, epilepsy, ataxia, Parkinson's disease and other disorders (Luscher & Slesinger, 2010). Whereas agonist-induced GIRK conductance is a well-recognized, classic mediator of inhibitory neurotransmission, the role of the basal activity of GIRK channels (Ibasal) is also emerging as being important in setting the level of excitability and resting membrane potential in neurons (Luscher et al. 1997; Torrecilla et al. 2002; Chen & Johnston, 2005; Wiser et al. 2006), in depotentiation of long-term potentiation (Chung et al. 2009) and possibly in working memory (Sanders et al. 2013).

According to the classic scheme, activation of GIRK is achieved through a direct interaction with the Gβγ subunit of Gi/o proteins. The free Gβγ is derived from Gαi/oβγ heterotrimers following agonist binding and the activation of GPCR. Both Gβγ and Gαi/o interact with multiple binding sites on cytosolic N- and C-terminal domains of GIRK subunits (Huang et al. 1995; Krapivinsky et al. 1995; Ivanina et al. 2003, 2004; Clancy et al. 2005; Yokogawa et al. 2011; Mase et al. 2012). It has been proposed that heterotrimeric G proteins and GIRK channels form a signalling complex (Doupnik, 2008; Raveh et al. 2009; Zylbergold et al. 2010), possibly ‘pre-associated’ before activation of GPCR, but the composition and the spatial organization of this hypothetical complex are incompletely understood. In a recent crystal structure of a complex of Gβγ with the homotetrameric GIRK2 channel in a ‘preopen’ state, the Gα subunit was not present (Whorton & MacKinnon, 2013), and biochemical data suggest that Gαi–GIRK interaction is weaker than that of GIRK–Gβγ (Berlin et al. 2011; Mase et al. 2012).

GIRKs are tetramers comprising four subunits, each containing two transmembrane domains, a pore region, and large cytosolic N- and C-termini. Mammals have four GIRK subunit genes encoding subunits GIRK1–4. All subunits are expressed in the brain, while GIRK1 and GIRK4 are expressed in the heart. GIRK2 and GIRK4 are able to form homotetramers, while GIRK1 and GIRK3 cannot; they need to associate with another type of subunit to form a functional channel (Dascal, 1997; Hibino et al. 2010). However, a pore mutation in GIRK1, F137S, allows its expression as a homotetramer (denoted GIRK1*) (Chan et al. 1996). Subunit distribution pattern varies among brain structures and within neurons, with GIRK1/2 being the predominant form in the brain (Luscher & Slesinger, 2010).

The functional consequences of divergent GIRK subunit composition are not well understood. In Xenopus oocytes and mammalian cells, heterologously expressed GIRK1/2 and GIRK1* have a substantial GPCR-independent basal current (Ibasal), which is mostly Gβγ-dependent, and show only moderate activation by agonists or coexpressed Gβγ (Leaney et al. 2000; Peleg et al. 2002; Rishal et al. 2005; Rubinstein et al. 2009). Functional data suggest that the high Ibasal of GIRK1/2 may reflect an excess of Gβγ over Gα available to the channel in its immediate microenvironment. Under the conditions of excess free Gβγ, addition of more Gβγ (by activating a GPCR or by coexpressing Gβγ) would cause only a modest increase in channel activity (Peleg et al. 2002; Rubinstein et al. 2007). In contrast, the GIRK2 homotetramer has low Ibasal, which appears mostly Gβγ-independent, and a robust Gβγ-dependent activation (Rubinstein et al. 2009).

The high basal currents of GIRK1-containing channels appear to be associated with the presence in the GIRK1 subunit of a unique distal C-terminal segment (G1-dCT) (Chan et al. 1997; Rubinstein et al. 2009; Wydeven et al. 2012). G1-dCT is absent from the available crystal structures of GIRK1, and it is not known how it folds or how it affects GIRK gating. We hypothesized that G1-dCT is somehow involved in the generation of excess Gβγ available for GIRK1, in correlation with its high Ibasal and mild activation by added Gβγ. To investigate the molecular basis of the differences between GIRK2 and GIRK1/2 or GIRK1* channels, and to better understand how G1-dCT is involved in the regulation of Ibasal, we took a structure–function approach with the GIRK2 and GIRK1* homotetramers expressed in Xenopus oocytes, and protein interaction assays using the cytosolic domains of these subunits. We find that GIRK1-containing channels increase Gβγ expression in the plasma membrane (PM), and identify the distal C terminus of GIRK1 as an essential structural element that confers upon GIRK1 a high affinity to Gβγ and carries an essential role in Gβγ recruitment to the PM and in Ibasal of GIRK1-containing channels. We suggest that G1-dCT is a crucial part of a Gβγ anchoring site in GIRK1.

Methods

Ethical approval and animals

Experiments were approved by Tel Aviv University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (permits M-08-081 and M-13-002). Female frogs, maintained at 20 ± 2°C on a 10 h light/14 h dark cycle, were anaesthetized in a 0.17% solution of procaine methanesulphonate (MS222), and portions of the ovary were removed through a small incision in the abdomen. The incision was sutured, and the animal was held in a separate tank until it had fully recovered from the anaesthesia, and afterwards was returned to the other post-operational animals. The animals did not show any signs of post-operative distress and were allowed to recover for at least 3 months until the next surgery. Following the final collection of oocytes, anaesthetized frogs were killed by decapitation and double pithing.

DNA constructs and RNA

All constructs were in pGEM-HJ or pBS-MXT vectors. For fluorescence labeling the coding regions of the DNAs of the desired proteins were fused in-frame to DNAs of cerulean (cyan) fluorescent protein (CFP) or enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) mutated to reduce dimer formation and to increase stability, as described in previous publications (Berlin et al. 2010, 2011). CFP and YFP are collectively denoted xFP in the following. Preparation of cDNAs of GIRK1, GIRK1F137S (GIRK1*), GIRK2, GIRK4, N-terminally YFP-tagged GIRK1F137S (YFP-GIRK1*), GIRK2 with an extracellular haemagglutinin (HA) tag (GIRK2HA), the cytosolic domains of GIRK1 and GIRK2 (G1NC and G2NC, respectively), Gβ1, Gγ2 and N-terminally xFP-tagged myristoylated Gαi3, and RNA preparation were as described previously (Yakubovich et al. 2000; Rubinstein et al. 2009; Berlin et al. 2011). Mouse GIRK3 cDNA was kindly provided by Henry A. Lester. N-terminally YFP-tagged Gγ was obtained from Wolfgang Schreibmayer. All other constructs were prepared using standard methods. The following constructs were inserted into the following restriction sites of pGEM-HJ vector using standard cut and paste (construct description in parentheses): GIRK1*-YFP (XbaI-rGIRK1F137S-XbaI-YFP-HindIII), GIRK2-YFP (BamHI-mGIRK2-XbaI-eYFP-HindIII) and CFP-Gγ (EcoRI-Cerulean-XbaI-hGγ2-HindIII). The following constructs were transferred to the pBS-MXT vector using standard PCR protocols (construct description in parentheses): G1NCΔ121 (EcoRI-rGIRK11-84-QSTASQST linker–rGIRK1185-380-NotI) and G2NC–dCTG1 (XbaI-mGIRK21-94-QSTASQST linker-mGIRK2195-381-rGIRK1371-501). The following constructs were prepared in pGEM-HJ vector using standard PCR protocols (construct description in parentheses): mCherry-G1dCT (EcoRI-mCherry-XhoI-rGIRK1380-501-XbaI), GIRK1*Δ67-YFP (XbaI-rGIRK1F137S,1-434-XhoI-YFP-HindIII), GIRK1*Δ121-YFP (XbaI-rGIRK1F137S,1-380-XhoI-YFP-HindIII), GIRK2–dCTG1 (BamHI-mGIRK21-380-XbaI-rGIRK1370-501-HindIII), GIRK1*Δ121 (XbaI-rGIRK1F137S,1-380-XbaI), GIRK1Δ121 (XbaI-rGIRK11-380-XbaI) and YFP-GIRK1*Δ67 (EcoRI-YFP-Xba-rGIRK1F137S, 1-434-XbaI). GIRK1*–dCTG2 was prepared in pGEM-HE vector using standard PCR protocols (construct description: YFP-hGIRK1F137S,1-381-mGIRK2382-414). The G1NCD67 construct was prepared by inserting a stop codon after amino acid 434 in the G1NC construct using site-directed mutagenesis.

The amounts of RNA injected per oocyte were varied according to the experimental design and are indicated in the Results or in figure legends. RNA of the muscarinic 2 receptor (m2R) was always 1–2 ng. For maximal channel activation by Gβγ we injected 5 ng Gβ and 1 ng Gγ RNA; for recruitment experiments, we used 1 ng Gβ and 0.5 ng xFP-Gγ RNA. These weight ratios of RNAs of Gβ, Gγ and xFP-Gγ were chosen to keep approximately equal molar amounts of Gβ and Gγ RNAs. Low doses of GIRK1* RNA were always co-injected with an anti-GIRK5 oligonucleotide XIR to prevent the formation of GIRK1*/5 channels (Hedin et al. 1996).

Electrophysiology

Oocyte defolliculation, incubation and RNA injection were performed as previously described (Rubinstein et al. 2009). Oocytes were incubated in NDE solution (in mm: 96 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 5 Hepes, 2.5 pyruvic acid, 50 mg l−1 gentamycin). Whole-cell GIRK currents in oocytes were measured using a standard protocol (see Fig. 4C) under two-electrode voltage clamp with Geneclamp 500 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), using agarose cushion electrodes (Schreibmayer et al. 1994) filled with 3 m KCl, with a resistance 0.1–0.3 MΩ. GIRK currents were measured in either low-[K+] solution ND96 (same as NDE but without pyruvic acid and gentamycin) or high [K+] solution (HK). We used HK with either 24 mm [K]out (in mm: 24 KCl, 72 NaCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2 and 5 Hepes) for high channel densities, or 96 mm [K]out (in mm: 96 KCl, 2 NaCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2 and 5 Hepes) for low channel densities. The pH of all solutions was 7.5–7.6.

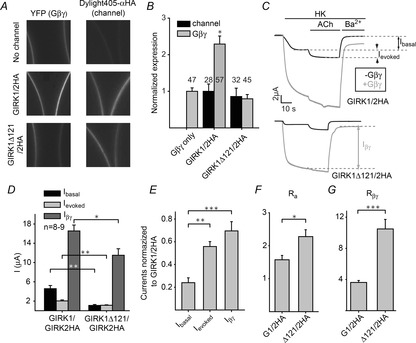

Figure 4. Deletion of GIRK1 dCT abolishes Gβγ recruitment by GIRK1/2HA.

A, expression levels of Gβγ-YFP (left column) and the GIRK2HA-containing channels (right column) were monitored in oocytes expressing no channel (top row), GIRK1/2HA (middle row) or GIRK1Δ121/2HA (bottom row). B, a summary of two experiments reveals that at the same channel expression levels (black bars), the GIRK1/2HA channel recruits Gβγ to the PM, whereas the heterotetrameric GIRK1Δ121/2HA does not (grey bars). C, representative currents of GIRK1/2HA (top) or GIRK1Δ121/2HA (bottom), without coexpressed Gβγ (black) or with 5:1 ng of coexpressed Gβ/Gγ (grey). Currents were first measured in a low-K+ solution (ND96), which was switched to the high K+ solution (HK, 24 mm K+, see Methods) resulting in an inward basal current, IHK. Then the oocyte was perfused with HK solution containing 10 μm ACh, to produce Ievoked (IACh). At the end, 5 mm Ba2+ was added to the solution to block GIRK currents and to reveal the residual non-GIRK current, Iresidual. Ibasal is defined as IHK–Iresidual, Ievoked as IACh–IHK, and Iβγ as IHK–Iresidual in oocytes expressing Gβγ. D, summary of current measurements in the experiment shown in C. E, currents of GIRK1Δ121/2HA were normalized to currents of GIRK1/2HA. The decrease in Ibasal was much more pronounced than the decrease in Ievoked and Iβγ. F and G, deletion of G1-dCT increases the extent of activation by agonist (F) and by Gβγ (G) in the GIRK1/2HA heterotetrameric channel. The extent of activation by agonist, Ra, is defined as (Ievoked+Ibasal)/Ibasal, and the extent of activation by coexpressed Gβγ, Rβγ, is defined as Iβγ/(average Ibasal) (Rubinstein et al. 2007). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Cell-attached patch clamp recordings were performed as previously described (Rubinstein et al. 2009), at 20–23°C using borosilicate glass pipettes with resistances of 1–5.5 MΩ. The electrode solution contained (in mm): 146 KCl, 2 NaCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 Hepes and 1 GdCl3 (pH 7.6). Bath solution contained (in mm): 146 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 6 NaCl, 10 Hepes and 1 EGTA (pH 7.6). Block of stretch-activated channels by GdCl3 was confirmed by recording currents at +80 mV. Single channel currents were recorded at −80 mV in cell-attached patches with the Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices) at −80 mV, filtered at 2 kHz and sampled at 10 kHz. Single channel amplitudes were calculated from Gaussian fits of all-points histograms of 30–90 s segments of the record. The open channel probability (Po) was estimated from 1–5 min segments of 4–20 min recordings from patches containing one to three channels using a standard idealized trace analysis (Yakubovich et al. 2000). Data acquisition and analysis were performed using pCLAMP (Molecular Devices).

Biochemistry

Glutathione-S-transferase fused Gαi3 (GST-Gα) and hexa histidine-tagged Gβγ (His-Gβγ) were purified as described (Dessauer et al. 1998; Rishal et al. 2003), and pull-down binding experiments were performed essentially as described (Farhy Tselnicker et al. 2014). Briefly, in vitro translated [35S]methionine-labelled proteins were prepared in rabbit reticulocyte lysate (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and mixed with either purified His-Gβγ or purified GST-Gα in 300 μl of the incubation buffer. For GST-Gα experiments, the incubation buffer contained, in mm: 150 KCl, 50 Tris, 0.6 MgCl2, 1 EDTA, 0.1% Lubrol and 90 μm GDP (pH 7.4). In His-Gβγ experiments, the buffer contained, in mm: 150 KCl, 50 Tris, 0.6 MgCl2, 1 EDTA, 0.1% Lubrol and 10 imidazole (pH 7.4). The mixture was incubated while shaking for 45 min at room temperature, then 30 μl beads were added, and incubated for 30 min at 4°C. His-Gβγ was pulled-down using HisPur™ Ni-NTA Resin affinity beads (ThermoFisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) and GST-Gα was pulled-down using glutathione sepharose beads (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The beads were washed three times with 500 μl buffer. Elution was done with 30 μl elution buffer (100 mm Tris-HCl, 120 mm NaCl and 15 mm glutathione in GST-Gα experiments, and with the incubation buffer supplemented with 250 mm imidazole in His-Gβγ experiments). After wash, the samples were analysed on 12% gels by SDS-PAGE. Also, 1/60 of the mixture before the pull-down was loaded, usually on a separate gel (‘input’). Gels were imaged using Typhoon PhosphorImager (GE Healthcare). Autoradiograms were analysed using ImageQuant 5.2 (GE Healthcare). Binding was calculated as percentage of input and then normalized to the binding of the control construct used in the same experiment (as indicated in the figures).

Giant membrane patches

The method used for giant membrane patches was as described before (Singer-Lahat et al. 2000). Oocytes were mechanically devitellinized using tweezers in hypertonic solution (in mm: 6 NaCl, 150 KCl, 4 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, pH 7.6). The devitellinized oocytes were transferred onto a Thermanox™ coverslip (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) immersed in Ca2+-free ND96 solution (in mm: 96 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 5 Hepes, 5 EGTA, pH 7.6) with their animal pole facing the coverslip, for 30–45 min. The oocytes were then suctioned using a Pasteur pipette, leaving a giant membrane patch attached to the coverslip, with the cytosolic part facing the medium. The coverslip was washed thoroughly with fresh ND96 solution, and fixated using 4% formaldehyde for 30 min.

Immunochemistry

Extracellular HA tag on GIRK2HA was labelled in whole oocytes fixated with 4% formaldehyde for 30 min. Oocytes were blocked in 5% milk in Ca2+-free ND96 solution for 1 h, incubated with mouse anti-HA antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) diluted 1:333 in 2.5% milk-Ca2+-free ND96 for 1 h, washed and incubated in DyLight405-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) as the primary antibody. Oocytes were then kept for no more than 1 week at 4°C in Ca2+-free ND96 solution until imaged. Fixated giant membranes were immunostained in 5% milk in PBS. Non-specific binding was blocked with Donkey IgG 1:200 (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA). Primary rabbit anti-Gβ (Santa Cruz, SC-378) was applied at 1:200 dilution for 45 min at 37°C either alone or with blocking peptide supplied with the antibody (for determining non-specific binding). Cy3-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) was then applied for 30 min at 37°C, washed with PBS and mounted on a slide for visualization. Immunostained slides were kept at 4°C for no more than 1 week.

Imaging

Confocal imaging and analysis were performed as described (Berlin et al. 2011), with a Zeiss 510 META confocal microscope, using a 20× objective. In whole oocytes, the image was focused on an oocyte's animal hemisphere, at the equator. Images were acquired using spectral (λ)-mode: CFP and DyLight405 were excited with a 405 nm laser and visualized at 481–492 nm (CFP) and 427–449 nm (DyLight 405). YFP was excited with the 514 nm line of the argon laser and visualized at 535–546 nm. Fluorescence signals at the maximum emission wavelength were averaged from three regions of interest using Zeiss LSM Image Browser, and averaged background and the average signal from uninjected oocytes were subtracted.

Visualization of giant membranes was performed under similar conditions. Cy3 conjugated to the secondary antibody was excited using a 543 nm laser, and visualized at 566–577 nm. Patches were visualized at their edges, so background fluorescence from the coverslip could be seen. Two regions of interest were chosen: one comprising the entire area of the membrane within the field of view, and another comprising background fluorescence, which was subtracted from the giant membrane emission. The signal from membranes immunostained with blocking peptide was subtracted from all groups.

Statistical analysis

Imaging data on protein expression have been normalized as described previously (Kanevsky & Dascal, 2006). Fluorescence intensity in each oocyte or giant membrane was calculated relative to the average signal in the oocytes of the control group of the same experiment. This procedure yields average normalized intensity as well statistical variability (e.g. SEM) in all treatment groups as well as in the control group. Statistical analysis was performed with SigmaPlot 11 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). If the data passed the Shapiro–Wilk normality test and the equal variance test, two-group comparisons were performed using a t test. If not, we performed the Mann–Whitney rank sum test. Multiple group comparison was done with one-way ANOVA if the data were normally distributed. ANOVA on ranks was performed whenever the data did not distribute normally. Tukey's post hoc test was performed for normally distributed data and Dunn's post hoc test otherwise. Unless specified otherwise, the data in the graphs are presented as mean ± SEM.

Results

GIRK channels increase surface levels of Gβγ but not myr-YFP-Gα

Previous immunocytochemical measurements in giant excised PM patches of Xenopus oocytes indicated that GIRK1/2 increases the expression of endogenous Gβγ and, to a lesser extent, Gαi/o (Rishal et al. 2005). To test whether GIRK1/2 also recruits to the PM the exogenous Gα and Gβγ, we expressed Gβγ and Gα tagged with either CFP or YFP (collectively denoted xFP) and monitored their surface expression in the presence of GIRK1/2. In these experiments we used N-terminally xFP-tagged myristoylated Gαi3 (myr-YFP-Gαi3) and wild-type Gβ coexpressed with Gγ tagged with CFP or YFP at the N terminus. For mild expression of Gβγ-xFP, low RNA doses were used, usually 1 ng per oocyte of Gβ and 0.5 ng per oocyte XFP-Gγ.

Figure 1A and B shows that expression of GIRK1/2 (1–2 ng RNA per oocyte of each subunit) induced an ∼3-fold increase in surface levels of Gβγ, but did not produce detectable changes in surface expression levels of myr-YFP-Gαi3. In comparison, expression of a large dose of untagged Gβγ caused an ∼2-fold increase in surface levels of myr-YFP-Gαi3, in agreement with previous works (reviewed by Hewavitharana & Wedegaertner, 2012), confirming that our system can detect changes in surface expression of myr-YFP-Gαi3 (Fig. 1C). Upon injection of 5-fold higher amounts of Gβγ RNA (5 ng Gβ and 2.5 ng xFP-Gγ), the surface levels of Gβγ were saturating, as no further increase could be detected upon co-expression of GIRK1/2 (Fig. 1D), presumably because of the excess of the overexpressed Gβγ. A GIRK2 channel with an extracellular HA tag, GIRK2HA, which usually shows high surface expression levels in the oocytes (Rubinstein et al. 2009), did not increase surface levels of Gα (Fig. 1C). Thus, GIRK1/2 increases Gβγ levels in the PM; changes in surface Gα levels, if any, are less substantial.

Figure 1. Expression of GIRK1/2 increases the surface levels of Gβγ-YFP but not of myr-YFP-Gαi3.

A, examples of images of oocytes expressing fluorescently labelled proteins. Surface expression levels of myr-YFP-Gαi3 (5 ng RNA per oocyte) and Gβγ-YFP (1 and 0.5 ng RNA of Gβ and YFP-Gγ, respectively) were measured without coexpression of GIRK (left column), or with coexpression of GIRK1/2 (1 or 2 ng RNA per oocyte; right column). B, summary of experiments shown in A. GIRK1/2 increased the expression of YFP-Gβγ (dark grey bars), but not of myr-YFP-Gαi3 (light grey bars). C, coexpressed Gβγ increases the surface level of myr-YFP-Gαi3, whereas GIRK1/2 and GIRK2HA are without effect. D, at high expression level, Gβγ is not recruited to the PM by GIRK1/2. The plot shows normalized expression level of Gβγ in oocytes injected with 5 ng Gβ RNA and 1 ng Gγ RNA, with or without GIRK1/2 channel (2 ng RNA per oocyte). At this expression level, there is no detectable Gβγ recruitment. ***P < 0.001; n.s., not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

GIRK1-containing channels, but not homotetrameric GIRK2, recruit Gβγ to the PM

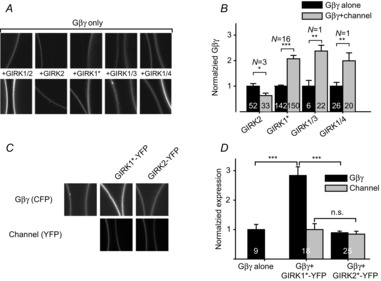

We hypothesized that the large Ibasal in the heteromeric GIRK1/2 and the homomeric GIRK1*, compared with the homomeric GIRK2, is due to better recruitment of Gβγ by the GIRK1 subunit. To test this, we monitored the surface expression of the xFP-tagged Gβγ in the presence of different GIRK channel compositions (Fig. 2A and B). As with GIRK1/2, coexpression of GIRK1*, GIRK1/3 and GIRK1/4 significantly increased the surface levels of Gβγ by 2- to 2.5-fold. In contrast, coexpression of GIRK2 did not increase the surface level of Gβγ but rather slightly reduced it (by 36 ± 10%, P < 0.05).

Figure 2. GIRK1-containing channels, but not GIRK2, increase the surface expression levels of Gβγ.

A, representative confocal images of oocytes expressing Gβγ-xFP (tagged with either CFP or YFP at the N terminus of Gγ). The Gβγ was expressed alone (top) or with different GIRK subunit combinations (bottom). For presentation only, the brightness/contrast of CFP images was enhanced equally in all images, to allow a better visualization. The amounts of GIRK subunits’ RNAs injected (per oocyte) were: 10 ng for homomeric GIRK2 and GIRK1*, 1 or 2 ng for GIRK1/2 (each subunit), 2 or 5 ng for GIRK1/3, and 2 or 5 ng of GIRK1 RNA and half of that amount of GIRK4 RNA for the heterotetrameric GIRK1/4. B, summary of the effects of different channel combinations on surface Gβγ expression. In each experiment, Gβγ expression in each oocyte was normalized to the average expression in the control (Gβγ-alone) group. The number of oocytes tested is shown within the bars, and the number of experiments (N) is indicated above the bars. C, effect of C-terminally YFP-tagged GIRK1* and GIRK2 channels on the surface expression of Gβγ-CFP (upper row). Levels of GIRK1*-YFP and GIRK2-YFP were measured in the same oocytes, to verify that they are expressed at similar levels (bottom). D, despite similar expression levels of the channels (grey bars), GIRK1* recruited Gβγ to the plasma membrane while GIRK2 did not (black bars). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, n.s., not significant (P > 0.05).

To exclude the possibility that the GIRK2 did not increase the surface expression of Gβγ because the channel itself was expressed less well than GIRK1/2 or GIRK1*, we monitored channel expression levels using C-terminally YFP-tagged GIRK subunits, GIRK2-YFP and GIRK1*-YFP. We coexpressed Gβγ-CFP with GIRK2-YFP or GIRK1*-YFP, and confirmed similar surface expression of both channels. Under these conditions, GIRK1*-YFP increased the Gβγ expression at the PM by 284±29% (P < 0.001), whereas GIRK2-YFP did not significantly alter Gβγ expression (Fig. 2C and D). In all, GIRK1-containing channels increase the surface expression of Gβγ, whereas the GIRK2 homotetramer does not.

Deletion of dCT of GIRK1 crucially affects GIRK-Gβγ and GIRK-Gα-Gβγ interactions

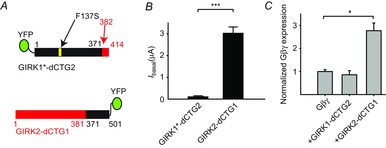

G1-dCT spans 121 amino acids (a.a.), from amino acids 380 to 501, with a short segment of partial homology to the other GIRK subunits at amino acids 434–450 (Fig. 3A). Only a weak direct interaction between dCT and Gβγ has been detected (Ivanina et al. 2003), but deletion of G1-dCT attenuated binding of Gβγ to the full-length C terminus (Huang et al. 1997). To address these inconsistencies, we examined whether dCT plays a role in the binding of Gβγ to GIRK1.

Figure 3. GIRK1 dCT affects the strength of GIRK1–Gβγ interaction.

A, amino acid alignment of C-terminal parts of GIRK1–4 reveals a unique 121 a.a. segment at the distal part of the C terminus of GIRK1 (a.a. 380–501), with a small stretch of partial homology with other subunits. B, schematic representation of the constructs used for pull-down experiments. All truncations were based on the G1NC construct (black bars), which consists of the cytosolic domains of GIRK1, with an 8 a.a. linker GSTASGST (cyan line) between them. Amino acids flanking the constructs’ parts are indicated below the cartoons. C and D, pulled-down of in vitro translated cytosolic G1NC, G1NCΔ67 and G1NCΔ121 with his-Gβγ. C, representative SDS-PAGE autoradiogram; D, summary of the experiments. To compare the results from different experiments, binding of each construct was calculated as percentage of input of that construct, and then normalized to G1NC. E, comparison between G2NC (the cytosolic domains of GIRK2) and G2NC-GIRK1 dCT chimera, G2NC–dCTG1 (G2NC top cartoon; G2NC–dCTG1 bottom cartoon; GIRK2 parts and a.a. numbers are in green, G1-dCT and GIRK1 a.a. numbers are in black). The G2NC–dCTG1 binds Gβγ better than G2NC. A representative autoradiogram is on the bottom left, and a summary of three experiments on the bottom right. F and G, effect of purified Gβγ (5 μg) on the interaction of GST-Gαi3GDP with G1NC and G1NCΔ121. F, representative experiment; G, summary of four experiments. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

Because both N- and C-terminal cytosolic parts of GIRKs participate in the formation of Gβγ-binding sites in GIRKs (Huang et al. 1997; Whorton & MacKinnon, 2013), we investigated the effect of G1-dCT in the context of the full-length cytosolic domain of the channel. Three constructs were used (Fig. 3B): G1NC, which comprises the entire cytosolic domain of GIRK1 with the transmembrane segment replaced by an 8 a.a. linker; and G1NCΔ67 and G1NCΔ121 (truncations of G1NC lacking the last 67 and 121 a.a. of G1NC, respectively). These constructs were expressed in rabbit reticulocyte lysate in the presence of [35S]methionine, and the resulting in vitro translated proteins were pulled down with purified His-tagged Gβγ (His-Gβγ) on Ni-agarose beads (Fig. 3C and D). These experiments revealed that deletion of the last 67 a.a. and especially 121 a.a. attenuated the G1NC–Gβγ interaction by 61 ± 7% and 79 ± 6%, respectively. Thus, the presence of dCT strengthens the GIRK1–Gβγ association.

Next, to see if G1-dCT can also potentiate the GIRK2–Gβγ interaction, we used G2NC – the full cytosolic domain of GIRK2 (Rubinstein et al. 2009) – and a chimera (G2NC–dCTG1) consisting of G2NC in which its own short distal C terminus (34 a.a.) was replaced by the 121 a.a. G1-dCT (Fig. 3E). The chimeric protein bound His-Gβγ significantly more strongly than G2NC (285 ± 22%, P < 0.001). This supports the hypothesis that the unique distal C terminus of GIRK1, although it does not strongly bind Gβγ by itself, renders the GIRK channel with high Gβγ affinity, compared with the core cytosolic domain.

GαGDP does not directly interact with a GST-fused G1-dCT (Ivanina et al. 2004; Berlin et al. 2010), but we suspected that G1-dCT might contribute to GαGDP binding in the context of the full cytosolic domain. To address this, we measured the binding of G1NC and G1NCΔ121 to GST-Gαi3GDP, in the presence or absence of purified Gβγ (Fig. 3F and G). There was no significant difference in the binding of GST-Gα to either construct in the absence of Gβγ. Thus, G1-dCT does not participate in GαGDP binding. However, while the purified Gβγ strengthened the G1NC–Gαi3GDP interaction 3-fold, as reported previously, it did not do so in the truncated construct. This result confirms that G1-dCT plays a vital role in the triple Gα–Gβγ–GIRK interaction (Rubinstein et al. 2009; Berlin et al. 2010).

The distal C terminus is involved in Gβγ recruitment and high basal activity of GIRK1/2

To address the involvement of G1-dCT in Gβγ recruitment, we used the GIRK1 subunit lacking the last 121 a.a. (GIRK1Δ121). To follow the channel's surface expression, the untagged GIRK1 and GIRK1Δ121 were coexpressed with the extracellularly HA-tagged GIRK2 (GIRK2HA), giving the heterotetrameric GIRK1/2HA and GIRK1Δ121/2HA channels. Gβγ-YFP was expressed at a low dose (as in Fig. 1A). After YFP-Gβγ expression was measured in intact oocytes (Fig. 4A, left column), the cells were fixated and immunolabelled with an anti-HA antibody (Fig. 4A, right column). Using this methodology, we were able to confirm equal expression of the truncated and the full-length channels (Fig. 4B, black bars). Under these conditions, GIRK1/2HA increased YFP-Gβγ expression in the plasma membrane by 229 ± 22%, while GIRK1Δ121/2HA did not alter Gβγ expression significantly (Fig. 4B, grey bars). Thus, G1-dCT is important for Gβγ recruitment in the context of the heterotetrameric GIRK1/2.

We then examined the function of the heterotetramers. Whole-cell GIRK currents were measured using standard protocols (Rubinstein et al. 2009). Figure 4C shows representative whole-cell currents of GIRK1/2HA (top) and GIRK1Δ121/2HA (bottom), in the absence (black) or presence (grey) of Gβγ. In these experiments, to elicit maximal GIRK current (Iβγ), untagged Gβγ was expressed at a saturating dose (5 ng Gβ RNA and 1 ng Gγ RNA per oocyte) that normally produced maximal activation of GIRK1/2 (data not shown) and GIRK2 (Rubinstein et al. 2009). The net GIRK's Ibasal in the absence of agonist in the HK solution was determined by subtracting the current remaining after full block of GIRK currents by Ba2+. Ievoked, the agonist-evoked current, was elicited by applying a saturating dose of acetylcholine (ACh; 10 μm) via the coexpressed m2R. The basal current in the presence of coexpressed Gβγ was measured in a separate group of cells.

Figure 4D summarizes the measurements of currents. GIRK1Δ121/2HA shows smaller Ibasal, Ievoked and Iβγ, but the effect of the truncation on Ibasal was significantly greater than on agonist- and Gβγ-induced currents: 76 ± 4% decrease in Ibasal, 44 ± 4% decrease in Ievoked and 30 ± 8% decrease in Iβγ (Fig. 4E). Notably, the extent of activation by agonist (Ra; see legend to Fig. 4) of the truncated GIRK1Δ121/2HA was larger than in the full-length channel (2.3 ± 0.2 vs. 1.6 ± 0.1, P = 0.014), as was the extent of activation by coexpressed Gβγ, Rβγ (10.5 ± 1.2 for GIRK1Δ121/2HA vs. 3.6 ± 0.3 for the full-length channel, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4F and G). Thus, deletion of G1-dCT strongly reduces both Gβγ recruitment by the GIRK1/2 channel and its basal activity, but substantially increases the relative extent of activation by Gβγ.

If the reduction in Ibasal of GIRK currents after truncation of G1-dCT is due mainly to a reduced association with Gβγ, then addition of G1-dCT to GIRK2 might confer both Gβγ recruitment and high Ibasal. To test this hypothesis, we prepared two chimeras: one based on GIRK1*, with the addition of the dCT of GIRK2 (Fig. 5A top, GIRK1*–dCTG2), and the other based on GIRK2, with the addition of the dCT of GIRK1 (Fig. 5A bottom, GIRK2–dCTG1). Both constructs were tagged with YFP (in the N terminus in GIRK1*–dCTG2 and in the C terminus in GIRK2–dCTG1) to monitor expression. As expected, fusion of dCT of GIRK1 to GIRK2 endowed the channel with high basal currents (Fig. 5B, 3.05 ± 0.27 μA), as reported previously with a similar chimeric construct that was labelled with an external HA tag instead of YFP (Rubinstein et al. 2009). The reverse chimera showed low basal currents (Fig. 5B, 0.12 ± 0.03 μA) and high Rβγ (7.9 ± 1.37, n = 7). Finally, the GIRK2–dCT1 construct showed significant Gβγ recruitment ability (Gβγ expression was 277 ± 33% of control), while the reverse chimera did not recruit Gβγ at the same expression level (Fig. 5C). These results support the notion that dCT of GIRK1 is important for Gβγ recruitment and high Ibasal.

Figure 5. GIRK1–GIRK2 chimeras confirm the role of G1-dCT in Gβγ recruitment and high Ibasal.

A, cartoon presentation of the two chimeric channels used. The GIRK1*–dCTG2 chimera shows small basal currents (B) and is unable to recruit Gβγ to the PM (C), while GIRK2–dCTG1 shows large basal currents and recruits Gβγ. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

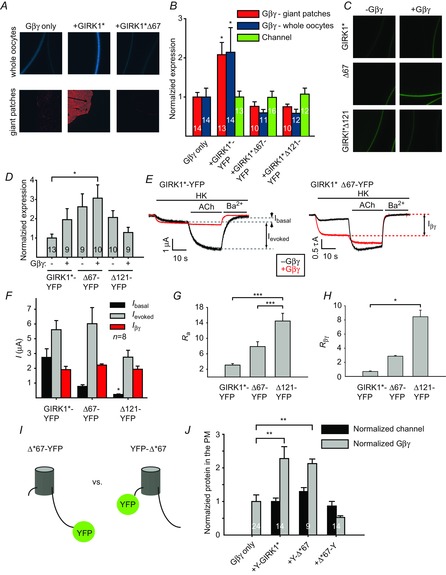

We also studied the effects of truncations of 67 and 121 C-terminal amino acids in the context of homotetrameric GIRK1* channels (Fig. 6). To monitor channel expression, all constructs were tagged at the C terminus with YFP or CFP, producing GIRK1*Δ67-xFP and GIRK1*Δ121-xFP. Changes in PM levels of Gβγ were monitored using two independent methods, with Gβγ-xFP (as in Fig. 1) and by immunostaining of giant excised membrane patches (see Methods) (Fig. 6A and B). Both methods gave similar results. At similar surface expression levels, GIRK1*-YFP induced an ∼2-fold increase in coexpressed Gβγ in the PM, while both GIRK1*Δ67-YFP and GIRK1*Δ121-YFP did not induce such an increase. The truncated channels had similar Ievoked but lower Ibasal than GIRK1* (Fig. 6F). Correspondingly, the extent of activation by agonist was higher in the truncated channels (Fig. 6G). Finally, the dCT deletions greatly affected activation by coexpressed Gβγ. As shown previously (Rubinstein et al. 2009), coexpressed Gβγ failed to increase Ibasal of GIRK1* channels expressed at high densities (Fig. 6F). The mechanism of this phenomenon is unknown but possible explanations are presented in the Discussion. In contrast, the dCT-truncated channels showed significant activation by coexpressed Gβγ (Fig. 6H). In summary, in C-terminally labelled GIRK1*, deletion of dCT generated channels with low Ibasal and substantial activation by Gβγ. However, the position of the xFP tag can significantly affect the properties of the truncated channel. In a representative experiment (Fig. 6I, J), the N-terminally YFP-tagged YFP-GIRK1* and YFP-GIRK1*Δ67 recruited Gβγ-CFP to the PM by more than 2-fold, whereas the C-terminally tagged GIRK1*Δ67-YFP did not. Unfortunately, an N-terminal fusion construct of GIRK1*Δ121, YFP-GIRK1*Δ121, did not express well in the oocytes (data not shown). Therefore, although the results of experiments with xFP-tagged homotetrameric channels generally support the conclusions drawn from the use of heteromeric GIRK1/2HA, they should be interpreted with caution and controlled for by using the untagged constructs.

Figure 6. Deletions of 67 or 121 a.a. of G1-dCT reduce Ibasal and Gβγ recruitment in GIRK1* channels labelled with YFP at the C terminus.

A, expression of Gβγ in the plasma membrane of Xenopus oocytes as seen in whole oocytes (top row; Gγ is tagged with CFP at the N terminus) or in giant membrane patches with antibody against Gβ (bottom row). B, both in whole oocytes (blue bars) and in giant membrane patches (red bars), plasma membrane expression level of Gβγ increases with GIRK1*-YFP, but not with the truncated GIRK1*Δ67-YFP or GIRK1*Δ121-YFP. Channel expression was similar in all cases (green bars). For better visualization of CFP images, their brightness/contrast was enhanced. C–H, electrophysiological properties of the truncated channel. C, expression of full-length and truncated channels was monitored with YFP in the presence or absence of Gβγ. D, summary of channel expression in a representative experiment. All channels showed similar expression levels. Gβγ was expressed at saturating levels (5:1 ng RNA of Gβ/Gγ). E, records of currents in oocytes expressing GIRK1*-YFP (left) and GIRK1*Δ67-YFP (right), without (black) or with (red) coexpressed Gβγ. F, summary of current amplitudes. Deletion of the last 67 or 121 a.a. of the YFP-tagged channel significantly reduces Ibasal, but not Ievoked or Iβγ. G and H, both Ra and Rβγ are higher in the truncated than in the full-length channels. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. I, cartoons of C-terminally YFP-tagged GIRK1*Δ67 channel (left, Δ*67-YFP) and N-terminally YFP-tagged GIRK1*Δ67 (right, YFP-Δ*67). J, at similar channel expression levels (black bars) the N-terminally tagged truncated channel showed Gβγ recruitment similar to the full length channel, while the C-terminally tagged GIRK1*Δ67 did not recruit Gβγ (grey bars). **P < 0.01.

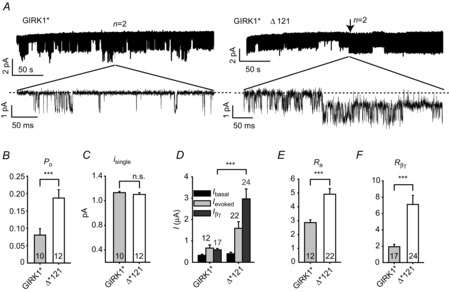

GIRK1*Δ121 shows higher Po,max and higher response to coexpressed Gβγ

To study the role of G1-dCT in the homomeric channels without the addition of fluorescent tags, we used untagged GIRK1* and GIRK1*Δ121. Single channel properties of Gβγ-activated GIRK1* and GIRK1*Δ121 were studied in cell-attached patches, while surface expression levels were adjusted to produce 0–5 channels per patch (2 ng RNA of GIRK1*Δ121 and 0.2 ng RNA of GIRK1*; see below, Fig. 7D). We measured the channel open probability, Po, from patches with 1–3 channels, and the single channel currents at –80 mV, isingle, in the presence of a high dose of coexpressed Gβγ (5:1 ng Gβ/Gγ RNA). Representative recording are shown in Fig. 7A. The GIRK1* channels showed bursting behaviour and an isingle of ∼ 1.1 pA, as described previously (Chan et al. 1996). GIRK1*Δ121 channels showed an unexpected behaviour: while some channels were obviously active from the beginning of the record (once the seal was formed), others started firing abruptly several minutes later. Figure 7A (right) illustrates one such patch, where a second channel suddenly appeared after 3.5 min of measurement. Therefore, for GIRK1*Δ121, we have averaged Po from 1–5 min segments of recording where there was no doubt regarding the number of active channels. The analysis showed that in the presence of high levels of coexpressed Gβγ, GIRK1*Δ121 had a significantly higher Po (0.18 ± 0.02) than GIRK1* (0.08 ± 0.02, P = 0.003) (Fig. 7B). The Po of GIRK1* channels in the absence of coexpressed Gβγ was low and a reliable count of channels in the patch was impossible, so we could not compare the basal Po of the two channels. The isingle values of the two channels were similar (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7. Deletion of G1-dCT increases Po and enhances activation by agonist and Gβγ in the GIRK1* homotetrameric channel.

A, cell-attached patch clamp records of GIRK1* channels (left trace) and GIRK1*Δ121 channels (right trace). K+ currents are shown as downward deflections from zero current, shown as dashed line. The oocytes expressed the channels in the presence of 5:1 ng per oocyte of Gβ/Gγ. Both patches contained two channels. Note that in GIRK1*Δ121 the second channel appears after >3 min of recording (arrow). The lower traces zoom in on the indicated intervals at an expanded time scale. B and C, summary of Po (B) and isingle (C) measurements. D–F, whole-cell currents of GIRK1* and GIRK1*Δ121 homomeric channels. Oocytes were injected with 0.2 and 2 ng RNA, respectively, to attain approximately equal levels of expression of the channels. Currents were measured in the 96 mm high-K+ solution (see Methods). Summary of current amplitudes is shown in D. The truncated homomeric channel shows a higher Ra (E) and Rβγ (F) than the full-length channel. ***P < 0.001.

We do not know the reason for the peculiar emergence of GIRK1*Δ121 channels in patches. It is possible that some of the GIRK1*Δ121 channels present in the patch became ‘silenced’ during patch formation and then recovered, or, alternatively, ‘silent’ channels became active because of a change in membrane conditions during a long patch recording. The mechanism is unknown; factors such as changes in cytoskeletal connections or membrane tension could play a role. This phenomenon seems to be linked to G1-dCT because it has not been observed in GIRK1* (n > 30 records).

We next examined the whole-cell electrophysiological properties of functional untagged channels expressed using the same RNA doses as for single channel experiments. The results of the whole-cell experiments are shown in Fig. 7D–F. Notably, at these relatively low levels of channel expression, coexpressed Gβγ moderately activated GIRK1* (Fig. 7D and F), as reported by others (Mahajan et al. 2013). This contrasts with the lack of Gβγ activation at high GIRK1* levels; possible mechanisms will be discussed.

Ievoked was not statistically different in GIRK1*Δ121 and GIRK1*, whereas Iβγ was much larger in GIRK1*Δ121 than in GIRK1*. Unexpectedly, GIRK1* and GIRK1*Δ121 displayed similar basal currents, although we expected a smaller Ibasal in GIRK1*Δ121 (because it does not recruit Gβγ). The probable reason is that in these experiments the level of expression of functional GIRK1*Δ121 channels in intact cells was higher than that of GIRK1*. To obtain an estimate of relative amounts of functional channels (N), we used the classical equation (Hille, 1992)

| (1) |

where Iβγ is the whole-cell Gβγ-evoked current, and Po is the open probability of a single Gβγ-activated GIRK channel. From here, given the equal isingle, the number of functional GIRK1*Δ121 and GIRK1* channels is proportional to their Iβγ/Po. Using the data of Fig. 7D, we estimated that, in experiments of Fig. 7D–F, the oocytes expressed 2.25-fold more GIRK1*Δ121 than GIRK1* channels; the actual Ibasal, per channel, was probably lower in GIRK1*Δ121. In support of this, the extent of activation by agonist and by Gβγ was significantly larger in GIRK1*Δ121 than in GIRK1* (Fig. 7E and F), as in the heteromeric GIRK1/2HA and the C-terminally labelled homomeric channels. Higher Ra and Rβγ are expected for channels that recruit less Gβγ and therefore show a greater activation by added Gβγ (see Discussion).

Discussion

In mammalian neurons, basal activity of GIRK channels contributes to the regulation of resting excitability and certain forms of plasticity. Heterologously expressed GIRK1/2, the predominant neuronal GIRK channel, possesses a substantial basal activity that is mostly Gβγ-dependent. Here we show that the large Ibasal of GIRK1/2 correlates with its ability to increase surface levels of the Gβγ subunit of G proteins (a phenomenon that we call ‘Gβγ recruitment’), and that the unique distal C terminus of GIRK1 (G1-dCT) is essential for Gβγ recruitment and, subsequently, for the channel's high Ibasal. G1-dCT also substantially contributes to Gβγ binding by GIRK1's cytosolic domain, but it is not needed for channel activation by Gβγ. Our findings support a two-site hypothesis that postulates functional and spatial separation of Gβγ anchoring versus effector activation in the GIRK1/2 channel.

Gβγ recruitment underlies high Ibasal of GIRK1* and GIRK1/2 and requires G1-dCT

Studies with heterologously expressed GIRK channels indicated a role for Gβγ and for the C terminus of GIRK1 in the generation of a high Ibasal. (1) For heterologously expressed GIRK1/4, GIRK1/2 and GIRK1*, Ibasal is largely Gβγ-dependent, as it is decreased upon coexpression of Gαi/o or Gβγ scavengers (Vivaudou et al. 1997; Leaney et al. 2000; Peleg et al. 2002; Rishal et al. 2005). We have therefore proposed that Gβγ available for channel activation (associated with GIRK1/2, or enriched in the channel's microenvironment) is in excess over Gα (Rubinstein et al. 2007). (2) Expression of GIRK1/2 increased the level of endogenous Gβγ in oocyte PM, with a smaller (Rishal et al. 2005) or no increase in surface Gα (Fig. 1). This might be the mechanism for the enrichment of Gβγ in the GIRK1/2 environment. (3) GIRK2, in contrast to GIRK1/2 and GIRK1*, has low basal activity when expressed both in Xenopus oocytes (Rubinstein et al. 2009) and in a mammalian cell line (Wydeven et al. 2012). Similarly, low basal activity was reported for GIRK4 homotetramers (Vivaudou et al. 1997). (4) G1-dCT is important for high basal activity of GIRK1/4 (Vivaudou et al. 1997) and GIRK1/2 (Wydeven et al. 2012), and ‘implanting’ G1-dCT of GIRK1 onto GIRK2 renders a higher Ibasal and a lower extent of activation by added Gβγ relative to Ibasal, Rβγ (Fig. 5B; Rubinstein et al. 2009).

Here we have formulated and established a simple, coherent model of basal activity that integrated the previous findings and allowed testable predictions. (1) The high, mostly Gβγ-dependent Ibasal of GIRK1/2 and GIRK1* is due to Gβγ recruitment. Accordingly, we predicted that GIRK2 should perform poorly in recruiting Gβγ. This can explain both the low Ibasal and the high relative activation by added Gβγ (Rβγ) and by Gβγ derived from the GPCR-activated G protein (Ra). (2) The dCT of GIRK1 (G1-dCT) is important for high Ibasal. Therefore, we expected that the removal of G1-dCT should both reduce Ibasal in GIRK1 and impair Gβγ recruitment. Accordingly, we expected an increase in Rβγ. The experimental results corroborated the predictions of the model:

Gβγ was recruited to the PM by all GIRK1-containing channels but not GIRK2, at similar levels of channel expression.

Deletion of the unique C-terminal 121 a.a. of GIRK1 produced a channel that did not recruit Gβγ and showed a lower basal activity. The lower Ibasal was consistently observed in those constructs where equal levels of expression of full-length and truncated channels could be compared: heteromeric GIRK1Δ121/GIRK2HA and homomeric GIRK1*Δ121 labelled with xFP at the C terminus.

Rβγ was increased by the removal of G1-dCT in all constructs tested.

Transplanting G1-dCT to GIRK2 endowed it with Gβγ recruitment, correlated with the previously reported high Ibasal. The opposite chimera, where the long G1-dCT was replaced with the shorter (34 a.a.) dCT of GIRK2, had low Ibasal and did not recruit Gβγ, underlining the uniqueness of G1-dCT.

Nevertheless, when compared with GIRK2 (Rubinstein et al. 2009), the basal current in GIRK1*Δ121 was still higher than in GIRK2 and the activation by Gβγ was weaker, suggesting that additional elements in GIRK channels, besides dCT, contribute to the variant subunit-dependent relationships between basal and Gβγ-evoked activity. These could be variations in amino acid composition in the pore (Wydeven et al. 2012) and in the cytosolic core, different sensitivity to membrane phospholipids such as PIP2 (Rohacs et al. 1999), etc. The nature of the Gβγ recruitment by GIRK1 remains to be investigated. Expression of GIRK1/2 does not alter the total endogenous Gβγ in the oocytes (Peleg et al. 2002), and thus the effect of GIRKs may occur by a reduced internalization or degradation, or an enhanced Gβγ translocation to the PM. There is evidence for a co-translocation of GIRKs and G proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum to the PM (Rebois et al. 2006). Recruitment may also occur by a mechanism similar to ‘kinetic scaffolding’ (Zhong et al. 2003; Mori et al. 2004) whereby strong binding of a cytosolic protein (Gβγ) to a membrane protein (GIRK1) increases the local concentration of Gβγ in the vicinity of the channel.

The two-site model: G1-dCT is an essential part of the Gβγ anchoring site in GIRK1

Following an original insight by He et al. (1999), we have previously proposed a two-site model for G protein interaction with GIRKs (Rubinstein et al. 2009). In this model, the Gαβγ heterotrimer is docked to the channel at an anchoring site, whereas channel activation is achieved through Gβγ binding to an activation site. During activation, the anchored Gβγ shifts or reorientates, making a better contact with the activation site. The two sites may overlap but at least partial spatial separation is envisaged. Our protein interaction findings (Fig. 3) support this model and, combined with functional data, reveal that G1-dCT is an essential element of a high-affinity anchoring site. Yet, G1-dCT is not necessary for channel activation by Gβγ, because GIRK1*Δ121 is activated by Gβγ, in fact better than the full-length GIRK1* (see below). These data suggest that G1-dCT does not constitute an essential part of the activation site, and support the conclusions of spectroscopic, structural and computational studies that the activation site, i.e. the Gβγ-binding site that leads to channel opening, is located within the well-conserved core of GIRK1 or GIRK2 (Yokogawa et al. 2011; Mahajan et al. 2013; Whorton & MacKinnon, 2013).

We further propose that anchoring is correlated with Gβγ recruitment. The protein interaction data show a definite decrease in the binding of Gβγ to the full cytosolic domain of GIRK1, G1NC, after removal of G1-dCT. Correspondingly, the truncated channel loses Gβγ recruitment and high Ibasal, and GIRK2 with an implanted G1-dCT acquires both of these features, in correlation with a stronger Gβγ binding.

We have not precisely mapped the structural elements of G1-dCT that are sufficient for these effects. Removal of 49 a.a. from GIRK1 only slightly reduced Ibasal of GIRK1/4 (Chan et al. 1997) and had no effect on Ibasal in GIRK1/2 (Wydeven et al. 2012), whereas in our hands the deletion of 67 a.a. produces partial and/or variable effects on Gβγ recruitment and Ibasal (depending on the positioning of the fluorescent label) and on Gβγ binding.

In all, the exact location and structure of the anchoring site in GIRK1, and the mechanism by which G1-dCT participates in anchoring, have yet to be uncovered. The structure of G1-dCT is unknown and appears labile; it is lacking in all available crystal structures of the cytosolic part of GIRK1 (Nishida & MacKinnon, 2002; Pegan et al. 2005) and of a channel composed of the cytosolic parts of GIRK1 and the transmembrane segment of a prokaryotic inward rectifier (Nishida et al. 2007). As purified G1-dCT does not strongly bind Gβγ by itself (Huang et al. 1997; Ivanina et al. 2003), the anchoring site must include cytosolic core elements outside of G1-dCT, whereas G1-dCT alters or stabilizes the conformation of the Gβγ-binding structure. Alternatively, while interacting with other parts of the cytosolic core, G1-dCT could acquire an affinity to Gβγ and become a structural part of a high-affinity Gβγ binding site, or a scaffold to tighten Gβγ to the core site.

The GIRK–G protein signalling complex

A permanent (pre-formed) signalling complex of GIRK with Gαi/oβγ heterotetramers is a popular concept (reviewed by Raveh et al. 2009; Nagi & Pineyro, 2014). However, here we show that, unlike for Gβγ, neither GIRK1/2 nor GIRK2 recruited the coexpressed fluorescently labelled Gαi3 to the PM (Fig. 2). This could be related to the impaired functional interaction of YFP-labelled Gαi3 with GIRK1/2 (Berlin et al. 2011) or a preferential modest recruitment of oocyte endogenous Gαi/o (Rishal et al. 2005). Nevertheless, we believe that the absence of a detectable recruitment of Gαi3 reflects the actual situation, with a preferential association of GIRK1/2 with Gβγ over Gα, as proposed in our previous functional studies (Rishal et al. 2005; Rubinstein et al. 2007), and explains the high Ibasal of GIRK1/2 and GIRK1*. Such preferential association calls for updating of the popular view of the existence of a preformed signalling complex of GIRK with Gi/o proteins, where an ‘inactive’ Gαβγ heterotrimer is permanently associated with the channel; a dynamic complex with variable stoichiometries of Gαβγ and Gβγ may be a more appropriate model. In the ‘minimal’ signalling complex (in vitro or in the oocyte that lacks auxiliary proteins such as RGS and AGS), the association with Gβγ is stronger (Berlin et al. 2011) and probably more permanent (Raveh et al. 2009), whereas GαGDP is dispensable. When present, GαGDP ‘primes’ the channel for Gβγ activation by offsetting the excess of channel-associated Gβγ and reducing Ibasal (Rubinstein et al. 2007). G1-dCT may be important for an interaction between GIRK1 and Gαiβγ heterotrimeric G protein, because G1-dCT deletion eliminates the enhancing effect of Gβγ on GIRK1-Gαi3GDP binding (Fig. 3F). Nevertheless, in native cells there may be additional scaffolding elements that help hold Gα in the vicinity of the channel and regulate Ibasal (e.g. Kienitz et al. 2014). The role of GαiGTP is debatable (Leal-Pinto et al. 2010; Berlin et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2014) and it has not been addressed in this study.

Note that coexpression of Gβγ did increase the surface expression of myr-YFP-Gαi3 (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, despite a significant recruitment of Gβγ by the coexpressed GIRK1/2, this recruited Gβγ did not cause an enhanced Gα expression. This raises the possibility that, under certain conditions, GIRK may serve as an alternative partner for Gβγ, instead of Gα. Indeed, the GIRK- and Gα-binding surfaces of Gβγ partially overlap (Ford et al. 1998; Whorton & MacKinnon, 2013).

G1-dCT as an inhibitory module for Gβγ activation

Our results suggest that, in addition to Gβγ anchoring and recruitment, G1-dCT may play an additional role in the regulation of GIRK. It has been previously shown that coexpression of the full-length C terminus of GIRK1 (Dascal et al. 1995), or addition of a DS6 peptide corresponding to the last 20 a.a. of GIRK1 (Luchian et al. 1997), inhibit the heterotetrameric GIRK1/5 and GIRK1/4 channels. The inhibition by the DS6 peptide was non-competitive with Gβγ, and it was proposed that G1-dCT is a part of an intrinsic inhibitory gating element (a ‘lock’) that helps to keep GIRK channels closed in the absence of Gβγ (Luchian et al. 1997; Rubinstein et al. 2009). Our results support this hypothesis, at least in the context of a homotetrameric GIRK1, as GIRK1*Δ121 exhibited a significantly higher Po than GIRK1* in the presence of Gβγ coexpressed at a saturating dose (Fig. 7B). The higher Po could also partly explain the higher Iβγ of GIRK1*Δ121 compared with GIRK1 (Fig. 7D). (Another portion of increased macroscopic Iβγ could be due to a higher expression of this channel in these experiments, as discussed above.)

The effect of coexpressed Gβγ on GIRK1* is controversial. Either 2- to 6-fold activation (Vivaudou et al. 1997; Mahajan et al. 2013) or no activation (Rubinstein et al. 2009) have been reported. Here we resolve the contradiction, at least on an empirical level. In our hands, GIRK1* was activated ∼2-fold in oocytes injected with a low dose of GIRK1* RNA (0.2 ng; Fig. 7) but not in cells injected with a 50-fold higher dose, 10 ng (Fig. 6). However, the mechanism remains unknown. The mysterious lack of activation may be related to the inhibitory function of G1-dCT (see Rubinstein et al. 2009 for a detailed discussion). Indeed, it seems that this function of G1-dCT is less pronounced in the context of GIRK1/2 heterotetramer compared with GIRK1* homotetramer; for instance, Iβγ is not increased in the GIRK1Δ121/2HA channel (Fig. 4). The presence of the complementary subunit such as GIRK2 may relieve the block imposed by G1-dCT by acting on the structural elements involved in the formation of the ‘lock’. The resolution of the Gβγ–GIRK1* activation problem may hold important keys for a better understanding of subunit-dependent gating mechanisms in GIRKs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. D. Yakubovich for fruitful discussions, Dr. Henry Lester for providing mouse GIRK3 cDNA and Dr. Wolfgang Schreibmayer for providing YFP-Gγ cDNA.

Glossary

- CFP

cerulean fluorescent protein

- G1-dCT

GIRK1 distal C terminus

- GIRK channel

G-protein coupled inwardly rectifying potassium channel

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

- GST

glutathione-S-transferase

- HA

haemagglutinin

- HK

high [K+]

- m2R

muscarinic 2 receptor

- Po

open probability

- PM

plasma membrane

- YFP

enhanced yellow fluorescent protein

Additional Information

Competing interests

None declared.

Author contributions

Experiments were conceived and designed by U.K., T.I., M.R., S.B. and N.D.; imaging and analysis was performed by U.K., B.S., R.C. and S.P.; biochemical experiments and analysis were performed by V.T.; two-electrode voltage clamp recording was performed by U.K. and G.T.; patch recordings and analysis were performed by U.K. and N.D.; DNA constructs and purified proteins were prepared by U.K., S.B., M.R., R.C., V.T., C.W.D. and T.I. C.W.D. contributed important intellectual input. The paper was written by U.K. and N.D. and approved by all authors.

Funding

This work was supported by the Israeli Science Foundation (grant nos. 386/09 to T.I. and 49/08 to N.D.) and by the US–Israel Binational Science Foundation to N.D. and C.W.D. (grant nos. 2009255 and 2013230).

Authors' present addresses

S. Berlin: Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA.

M. Rubinstein: Department of Pharmacology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA.

S. Peleg: Racine IVF Unit, Sourasky Medical Center, Tel-Aviv, Israel.

References

- Berlin S, Keren-Raifman T, Castel R, Rubinstein M, Dessauer CW, Ivanina T, Dascal N. Gαi and Gβγ jointly regulate the conformations of a Gβγ effector, the neuronal G-protein activated K+ channel (GIRK) J Biol Chem. 2010;285:6179–6185. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.085944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin S, Tsemakhovich VA, Castel R, Ivanina T, Dessauer CW, Keren-Raifman T, Dascal N. Two distinct aspects of coupling between Gαi and G protein-activated K+ channel (GIRK) revealed by fluorescently-labeled Gαi3 subunits. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:33223–33235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.271056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KW, Sui JL, Vivaudou M, Logothetis DE. Control of channel activity through a unique amino acid residue of a G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channel subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14193–14198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.14193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KW, Sui JL, Vivaudou M, Logothetis DE. Specific regions of heteromeric subunits involved in enhancement of G protein-gated K+ channel activity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6548–6555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Johnston D. Constitutively active G-protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channels in dendrites of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3787–3792. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5312-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HJ, Ge WP, Qian X, Wiser O, Jan YN, Jan LY. G protein-activated inwardly rectifying potassium channels mediate depotentiation of long-term potentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:635–640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811685106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy SM, Fowler CE, Finley M, Suen KF, Arrabit C, Berton F, Kosaza T, Casey PJ, Slesinger PA. Pertussis-toxin-sensitive Gα subunits selectively bind to C-terminal domain of neuronal GIRK channels: evidence for a heterotrimeric G-protein-channel complex. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;28:375–389. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dascal N( Signalling via the G protein-activated K+ channels. Cell Signal. 1997;9:551–573. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(97)00095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dascal N, Doupnik CA, Ivanina T, Bausch S, Wang W, Lin C, Garvey J, Chavkin C, Lester HA, Davidson N. Inhibition of function in Xenopus oocytes of the inwardly rectifying G-protein-activated atrial K channel (GIRK1) by overexpression of a membrane-attached form of the C-terminal tail. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6758–6762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessauer CW, Tesmer JJ, Sprang SR, Gilman AG. Identification of a Giα binding site on type V adenylyl cyclase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25831–25839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doupnik CA( GPCR-Kir channel signaling complexes: defining rules of engagement. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2008;28:83–91. doi: 10.1080/10799890801941970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhy Tselnicker I, Tsemakhovich V, Rishal I, Kahanovitch U, Dessauer CW, Dascal N. Dual regulation of G proteins and the G-protein-activated K+ channels by lithium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:5018–5023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316425111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford CE, Skiba NP, Bae H, Daaka Y, Reuveny E, Shekter LR, Rosal R, Weng G, Yang CS, Iyengar R, Miller RJ, Jan LY, Lefkowitz RJ, Hamm HE. Molecular basis for interactions of G protein βγ subunits with effectors. Science. 1998;280:1271–1274. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5367.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C, Zhang H, Mirshahi T, Logothetis DE. Identification of a potassium channel site that interacts with G protein βγ subunits to mediate agonist-induced signaling. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12517–12524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedin KE, Lim NF, Clapham DE. Cloning of a Xenopus laevis inwardly rectifying K+ channel subunit that permits GIRK1 expression of IKACh currents in oocytes. Neuron. 1996;16:423–429. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewavitharana T, Wedegaertner PB. Non-canonical signaling and localizations of heterotrimeric G proteins. Cell Signal. 2012;24:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibino H, Inanobe A, Furutani K, Murakami S, Findlay I, Kurachi Y. Inwardly rectifying potassium channels: their structure, function, and physiological roles. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:291–366. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B( G protein-coupled mechanisms and nervous signaling. Neuron. 1992;9:187–195. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90158-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CL, Jan YN, Jan LY. Binding of the G protein βγ subunit to multiple regions of G protein-gated inward-rectifying K+ channels. FEBS Lett. 1997;405:291–298. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CL, Slesinger PA, Casey PJ, Jan YN, Jan LY. Evidence that direct binding of Gβγ to the GIRK1 G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channel is important for channel activation. Neuron. 1995;15:1133–1143. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanina T, Rishal I, Varon D, Mullner C, Frohnwieser-Steinecke B, Schreibmayer W, Dessauer CW, Dascal N. Mapping the Gβγ-binding sites in GIRK1 and GIRK2 subunits of the G protein-activated K+ channel. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29174–29183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304518200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanina T, Varon D, Peleg S, Rishal I, Porozov Y, Dessauer CW, Keren-Raifman T, Dascal N. Gαi1 and Gαi3 differentially interact with, and regulate, the G protein-activated K+ channel. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:17260–17268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313425200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanevsky N, Dascal N. Regulation of maximal open probability is a separable function of Cavβ subunit in L-type Ca2+ channel, dependent on NH2 terminus of α1C (Cav1.2α) J Gen Physiol. 2006;128:15–36. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kienitz M-C, Mintert-Jancke E, Hertel F, Pott L. Differential effects of genetically-encoded Gβγ scavengers on receptor-activated and basal Kir3.1/Kir3.4 channel current in rat atrial myocytes. Cell Signal. 2014;26:1182–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krapivinsky G, Krapivinsky L, Wickman K, Clapham DE. Gβγ binds directly to the G protein-gated K+ channel, IKACh. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29059–29062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal-Pinto E, Gomez-Llorente Y, Sundaram S, Tang Q-Y, Ivanova-Nikolova T, Mahajan R, Baki L, Zhang Z, Chavez J, Ubarretxena-Belandia I, Logothetis DE. Gating of a G protein-sensitive mammalian Kir3.1 – prokaryotic Kir channel chimera in planar lipid bilayers. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:39790–39800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.151373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaney JL, Milligan G, Tinker A. The G protein α subunit has a key role in determining the specificity of coupling to, but not the activation of, G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channels. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:921–929. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchian T, Dascal N, Dessauer C, Platzer D, Davidson N, Lester HA, Schreibmayer W. A C-terminal peptide of the GIRK1 subunit directly blocks the G protein-activated K+ channel (GIRK) expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol. 1997;505:13–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.013bc.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luscher C, Jan LY, Stoffel M, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K+ channels (GIRKs) mediate postsynaptic but not presynaptic transmitter actions in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 1997;19:687–695. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luscher C, Slesinger PA. Emerging roles for G protein-gated inwardly rectifying potassium (GIRK) channels in health and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:301–315. doi: 10.1038/nrn2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan R, Ha J, Zhang M, Kawano T, Kozasa T, Logothetis DE. A computational model predicts that Gβγ acts at a cleft between channel subunits to activate GIRK1 channels. Sci Signal. 2013;6:ra69. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mase Y, Yokogawa M, Osawa M, Shimada I. Structural basis for the modulation of the gating property of G protein-gated inwardly rectifying potassium ion channel (GIRK) by the i/o-family G protein α subunit (Gαi/o. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:19537–19549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.353888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori MX, Erickson MG, Yue DT. Functional stoichiometry and local enrichment of calmodulin interacting with Ca2+ channels. Science. 2004;304:432–435. doi: 10.1126/science.1093490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagi K, Pineyro G. Kir3 channel signaling complexes: focus on opioid receptor signaling. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:186. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida M, Cadene M, Chait BT, Mackinnon R. Crystal structure of a Kir3.1-prokaryotic Kir channel chimera. EMBO J. 2007;26:4005–4015. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida M, MacKinnon R. Structural basis of inward rectification. Cytoplasmic pore of the G protein-gated inward rectifier GIRK1 at 1.8 Å resolution. Cell. 2002;111:957–965. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegan S, Arrabit C, Zhou W, Kwiatkowski W, Collins A, Slesinger PA, Choe S. Cytoplasmic domain structures of Kir2.1 and Kir3.1 show sites for modulating gating and rectification. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:279–287. doi: 10.1038/nn1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peleg S, Varon D, Ivanina T, Dessauer CW, Dascal N. Gαi controls the gating of the G-protein-activated K+ channel, GIRK. Neuron. 2002;33:87–99. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00567-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raveh A, Riven I, Reuveny E. Elucidating the gating of the GIRK channel using spectroscopic approach. J Physiol. 2009;587:5331–5335. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.180158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebois RV, Robitaille M, Gales C, Dupre DJ, Baragli A, Trieu P, Ethier N, Bouvier M, Hebert TE. Heterotrimeric G proteins form stable complexes with adenylyl cyclase and Kir3.1 channels in living cells. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:2807–2818. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rishal I, Keren-Raifman T, Yakubovich D, Ivanina T, Dessauer CW, Slepak VZ, Dascal N. Na+ promotes the dissociation between Gα-GDP and Gβγ, activating G-protein-gated K+ channels. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3840–3845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200605200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rishal I, Porozov Y, Yakubovich D, Varon D, Dascal N. Gβγ-dependent and Gβγ-independent basal activity of G protein-activated K+ channels. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16685–16694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412196200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohacs T, Chen J, Prestwich GD, Logothetis DE. Distinct specificities of inwardly rectifying K+ channels for phosphoinositides. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36065–36072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein M, Peleg S, Berlin S, Brass D, Dascal N. Gαi3 primes the G protein-activated K+ channels for activation by coexpressed Gβγ in intact Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol. 2007;581:17–32. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.125864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein M, Peleg S, Berlin S, Brass D, Keren-Raifman T, Dessauer CW, Ivanina T, Dascal N. Divergent regulation of GIRK1 and GIRK2 subunits of the neuronal G protein gated K+ channel by GαiGDP and Gβγ. J Physiol. 2009;587:3473–3491. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.173229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders H, Berends M, Major G, Goldman MS, Lisman JE. NMDA and GABAB (KIR) conductances: the “perfect couple” for bistability. J Neurosci. 2013;33:424–429. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1854-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreibmayer W, Lester HA, Dascal N. Voltage clamp of Xenopus laevis oocytes utilizing agarose cushion electrodes. Pflugers Arch. 1994;426:453–458. doi: 10.1007/BF00388310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer-Lahat D, Dascal N, Mittelman L, Peleg S, Lotan I. Imaging plasma membrane proteins in large membrane patches of Xenopus oocytes. Pflugers Arch. 2000;440:627–633. doi: 10.1007/s004240000341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrecilla M, Marker CL, Cintora SC, Stoffel M, Williams JT, Wickman K. G-protein-gated potassium channels containing Kir3.2 and Kir3.3 subunits mediate the acute inhibitory effects of opioids on locus ceruleus neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:4328–4334. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04328.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivaudou M, Chan KW, Sui JL, Jan LY, Reuveny E, Logothetis DE. Probing the G-protein regulation of GIRK1 and GIRK4, the two subunits of the KACh channel, using functional homomeric mutants. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31553–31560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Whorton MR, MacKinnon R. Quantitative analysis of mammalian GIRK2 channel regulation by G proteins, PIP2 and Na+ in a reconstituted system. Elife. 2014;3:e03671. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whorton MR, MacKinnon R. X-ray structure of the mammalian GIRK2-βγ G-protein complex. Nature. 2013;498:190–197. doi: 10.1038/nature12241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiser O, Qian X, Ehlers M, Ja WW, Roberts RW, Reuveny E, Jan YN, Jan LY. Modulation of basal and receptor-induced GIRK potassium channel activity and neuronal excitability by the mammalian PINS homolog LGN. Neuron. 2006;50:561–573. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wydeven N, Young D, Mirkovic K, Wickman K. Structural elements in the Girk1 subunit that potentiate G protein-gated potassium channel activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:21492–21497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212019110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakubovich D, Pastushenko V, Bitler A, Dessauer CW, Dascal N. Slow modal gating of single G protein-activated K+ channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol. 2000;524:737–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00737.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokogawa M, Osawa M, Takeuchi K, Mase Y, Shimada I. NMR analyses of the Gβγ binding and conformational rearrangements of the cytoplasmic pore of G protein-activated inwardly rectifying potassium channel 1 (GIRK1) J Biol Chem. 2011;286:2215–2223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.160754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong H, Wade SM, Woolf PJ, Linderman JJ, Traynor JR, Neubig RR. A spatial focusing model for G protein signals. Regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) protein-mediated kinetic scaffolding. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7278–7284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zylbergold P, Ramakrishnan N, Hebert T. The role of G proteins in assembly and function of Kir3 inwardly rectifying potassium channels. Channels. 2010;4:411–421. doi: 10.4161/chan.4.5.13327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]