Abstract

Acute lung injury (ALI) was one of the major complications after cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) play an important role in ALI following CPB. In this study, we investigated the effects of doxycycline (DOX), a potent MMP inhibitor, on MMP-9 and ALI in the rat model of CPB. 48 adult male Sprague-Dawley rats were randomized into four groups: group I (Control group, underwent cannulation + heparinization only); group II (CPB group, underwent 60-minutes of normothermic CPB); group III (Low-dose treatment group, underwent 60-minutes of normothermic CPB with DOX gavage 30 mg/kg ×1 week ahead of CPB); and group IV (High-dose treatment group, underwent 60-minutes of normothermic CPB with DOX gavage 60 mg/kg ×1 week ahead of CPB). The effects of doxycycline on ALI were determined by measuring the lung Wet/Dry ratio, the inflammation of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and the ultrastructural changes of the lungs. The role of doxycycline on MMP-9 was assessed by the plasma concentration, the activity and the expression in lung tissue. Our results demonstrated that the lung Wet/Dry weight ratio and the inflammatory mediators (TNF-α, IL-1β) in BALF were decreased significantly with doxycycline treatment. The lung damages were attenuated by doxycycline. The levels of plasma concentration, the activity and the expression of MMP-9 in lung tissue were suppressed with doxycycline and the effects were dose dependent. Doxycycline could suppress the expression of MMP-9 and cytokines, and improve the ALI following CPB.

Keywords: Doxycycline, matrix metalloproteinases-9, acute lung injury, cardiopulmonary bypass, rat model

Introduction

Cardiopulmonary bypass has been shown to exert an inflammatory response within the lung, often resulting in postoperative pulmonary dysfunction. About 25% of patients following open heart surgery are reported to have a significant respiratory impairment for at least one week after operation [1]. The systemic inflammatory response to the extracorporeal circuit was the main reason leads to pulmonary injury [2]. Although strategies to reduce post-CPB lung injury have been examined [3], few have been applied in clinical practice, and the ideal management for the lungs during CPB remains controversial.

One essential step in the pathogenesis of respiratory impairment is the disruption of the pulmonary membrane and the infiltration of polymorphonuclear neutrophil granulocytes (PMNs) across the basement membrane into the pulmonary tissue. In this process, degradation of both basement membrane and extracellular matrix is required. The transmigration of neutrophils from pulmonary capillaries to the site of injury is facilitated by several proteinases that are stored in intracellular granules and released on the presence of proinflammatory stimuli. These potent proteinases include neutrophil elastase, myeloperoxidase, and matrix metalloproteinases, for example, MMP-9 and MMP-8, et al [4].

MMPs are zinc-dependent endopeptidases that are able to degrade almost all extracellular matrix components [5]. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), a subgroup of zinc endopeptidases, has been identified to degrade basement membrane components [6]. MMP-9 is therefore considered essential for PMN migration and alveolar capillary leakage. So MMP-9 inhibition may be a promising target for reduction or prevention of lung impairment. Doxycycline (DOX) is a tetracycline derivate, have nonspecific MMP inhibitory effects that are distinct from their antimicrobial action [6,7]. Doxycycline is cleared for use in periodontal disease as an MMP inhibitor by the USFDA [8]. In some lung disease, doxycycline has been used in clinical trials [9].

In this study we investigated the effects of doxycycline on the expression of MMP-9 and whether it influences the CPB-induced lung injury.

Materials and methods

Animals and groups

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (450-550 g) were used in the present study. All animals were housed in cages individually at standard conditions (12-hour light/dark cycle and 21°C ± 1°C). Animals received humane care in compliance with Principles of Laboratory Animal Care, formulated by the National Society for Medical Research, and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, prepared by the National Academy of Sciences and published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH Pub. No. 85-23, revised 1996). The following experimental protocol was approved by local ethical committee.

Rats were randomly assigned to one of four groups (n = 12 for each group): group I (Sham group, underwent cannulation + heparinization only); group II (CPB group, underwent 60-minutes of normothermic of CPB procedure only); group III (Low-dose group, underwent 60-minutes of normothermic of CPB which rats administered daily with 30 mg/kg DOX orally one week ahead of CPB); group IV (High-dose group, underwent 60-minutes of normothermic of CPB which rats administered daily with 60 mg/kg DOX orally one week ahead of CPB). In order to investigate the effects of dosage of DOX for MMP-9, we designed two doses, 30 mg/kg and 60 mg/kg. The dose of 30 mg/kg was used previously to inhibit MMPs in studies of pancreatitis-associated lung injury [10]. The dose of 60 mg/kg was the test dose.

Rat model of cardiopulmonary bypass

The rat model of CPB was based on the model for extracorporeal circulation in the rats as developed by Dong and associates [11]. Rats were anesthetized with butaylone (60 mg/kg, intraperitoneal administration), and anesthesia was maintained with additional butaylone. The right femoral artery was cannulated for arterial pressure monitoring. Following administration of heparin (250 U/kg), a 16-gauge catheter, modified to a multiside-orifices cannula in the forepart, was inserted into the right atrium through the right jugular vein approach for vein drain line. A 22-gauge catheter for arterial infusion was introduced into tail artery. The mini-cardiopulmonary bypass circuit comprised a venous reservoir (10 ml), a specially designed membrane oxygenator (Micro-1, Kewei Medical Instrument Inc, Guangzhou, China), a roller pump (BT00-300M, Lange Co, Shanghai, China). All components were connected with polyethylene tubing. Rectal temperature was monitored and kept at 37-38°C by a heat lamp placed around the animal and the equipments. The circuit was primed with 10 ml of heparin 1 ml (250 U/kg), synthetic colloid 8 ml and sodium bicarbonate 1 ml. The flow rate was gradually added to 100 ml/kg/min and maintained for 60 min. Mean arterial pressure was maintained about 60 to 80 mm Hg throughout the experiment. The right jugular vein was decannulated as soon as cardiopulmonary bypass was accomplished. According to the blood pressure, part of the remaining priming was infused through the tail artery. The tail and femoral artery catheters were removed and the incisions were sutured after procedure.

Specimen collection

The rats were sacrificed at the termination of CPB (T1), 6 h after termination of CPB (T2) respectively in four groups. In the sham group, the rats were sacrificed at the same time point. Chest was opened and blood was collected from heart atrium. Both lungs were removed intact and washed by PBS buffer. Right upper lung was served at 10% formalin liquid for immunohistochemistry, and lower lobe was fixed quickly in 2.5% cold glutaraldehyde solution for ultrastructure by transmission electron microscope. Left lungs were cannulated for bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) after weighted.

Lung wet/dry weight ratio

Left lungs were sharply dissected free of nonparenchymal tissue, with care taken to avoid contact with the tissue. Samples were placed in a dish and weighed. After bronchoalveolar lavage, the specimen was then oven-dried at 65°C for 24 hours and reweighed and wet/dry (W/D) weight ratio was calculated as a marker for lung edema.

Measurement of cytokines in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

The left main bronchus was cannulated and secured so that the fluid didn’t overflow. Ice saline was then injected as 3 aliquots of 6ml each. Each aliquot was injected quickly and then withdrawn slowly 3 times to obtain an optimal the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) specimen. Combined aliquots of BALF were spun at 1000 g for 10 min to remove cells. Supernatant was frozen at -70°C for measurement of TNF-α and IL-1β, which were measured using corresponding enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (R&D System, Inc, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Measurement of plasma concentration of MMP-9

The blood collected from heart was spun immediately at 3500 g for 15 min. the supernatant fluid was frozen at -70°C for measurement of concentration of MMP-9, which were measured using ELISA kits (Catalog Number DMP900, MBA901) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blot analysis for MMP-9 activity in BALF

All rats BALF samples were electrophoresed on SDS-polyacrylamide gels (30 μg protein/sample was loaded for each immunoblot lane) and electroblotted onto Immobilon-P PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked in Tris buffer (PH = 7.4) containing 5% powdered milk for one hour, washed and incubated with primary antibody of interest overnight at 4°C. After incubation, samples were washed with borate saline (100 mM boric acid, 25 mM Na borate, 75 mM NaCl) and incubated with species-specific IgG horseradish peroxidase conjugates (at dilutions of 1:5000) for one hour. Immunoblots were then developed using NEN chemiluminescent kits and the gel scanning imaging system.

Immunohistochemical staining for lung tissue MMP-9 levels

The levels of alveolar tissue MMP-9 was assessed by immunohistochemical analysis [12]. Briefly, 4-μm formalin-fixed paraffin sections were treated with xylene and ethanol to remove paraffin and hydrated. The endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubation for 5 min with 3% H2O2 in methanol at 37°C, and then was washed with double distilled water for 5 min and PBS for 15 min. The sections were incubated in citrate buffer (10 mmol/L, PH 6.0) at 95°C with Ki-67 repair for 30 min, VEGF CD34 repair for 5 min, then natural cooled to room temperature, PBS buffer washed for 15 min. The nonspecific binding sites were blocked by incubation with 5% bovine serum albumin. The sections were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with monoclonal anti-rat MMP-9 antibodies (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark, 1:200), The slides were washed for 15 min in 0.01% Triton X-100 in PBS (140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, KH2PO4, pH 7.4). Then detected by Histostain Plus Kit (Zymed) system. Finally, counterstaining was performed with hematoxylin for 30 seconds, dehydrated with ethanol and xylene, sealed with resinene. The immunoreactivities of whole tissue specimens were semiquantified independently by two persons to five degrees (0-none, 1-mild, 2-moderate, 3-abundant, 4-strongly abundant immunoreactivity).

Ultrastructure of lung tissue

Ultrastructure of lung tissue was observed by transmission electron microscopy (JEM-1200, Japan). Fresh lung specimens were fixed quickly in 2.5% cold glutaraldehyde solution for 2 hours, in 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 hour, then gradient dehydrated in acetone, embedded by Epon-812 resin, orientated by semi-thin section, sliced into 70 nm ultra-thin sections, and double electron stained by uranyl acetate - lead citrate, observed by transmission electron microscope.

Statistical analysis

All values were expressed as mean ± SD. Data were analyzed using a commercially available statistics software package (SPSS for Windows v. 13.0, Chicago, IL, USA). We used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with multiple comparisons for repeatedly measured parameters. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Pulmonary edema

The CPB group caused a significant increase in lung water (expressed by W/D weight ratio) as compared with other three groups. Lung water was significantly reduced by the administration of DOX, and high dose DOX could further reduce the weight ratio (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pulmonary edema. Pulmonary edema was assessed by gravimetric lung water measurement (W/D weight ratio). Lung water was significantly reduced by the administration of DOX, and high dose DOX could further reduce the weight ratio. Data are means ± SD, *P < 0.05 versus all other groups at the same time point respectively.

TNF-α and IL-1β of BALF

Pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and TNF-α) in the BALF was detected by ELISA to investigate whether the DOX had any effect on the inflammatory response following CPB. The level of IL-1β and TNF-α of BALF elevated markedly after CPB. In the treatment group, the expression was inhibited significantly, and the concentrations were lower following the dose increased. The trend of expression was similar between IL-1β and TNF-α (Figures 2, 3).

Figure 2.

The effect of DOX on IL-1β in BALF. DOX could suppress the expression of IL-1β and the inhibiting effect with high dose was greater compared with low-dose. Data are means ± SD, *P < 0.05 versus all other groups at the same time point respectively.

Figure 3.

The effect of DOX on TNF-α in BALF. DOX could suppress the expression of TNF-α and the inhibiting effect with high dose was greater compared with low-dose. Data are means ± SD, *P < 0.05 versus all other groups at the same time point respectively.

Plasma levels of MMP-9

The plasma levels of MMP-9 increased significantly following CPB compared with pre-CPB or sham group. DOX could reduce the expression of MMP-9. Both DOX treatment groups demonstrated significant depression of MMP-9 in the plasma as compared to sham group and CPB group. Between the treatment groups, there were significant differences in the level of MMP-9. With the administration of high-dose of DOX, a significant reduction in plasma was demonstrated as compared with the low-dose group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Plasma concentrations of MMP-9 in rat model with CPB (μg/L)

| Pre-CPB | T1 | T2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | 2.31 ± 0.78 | 3.56 ± 1.12 | 3.48 ± 1.09 |

| Group II | 2.26 ± 0.67 | 24.06 ± 2.67* | 19.35 ± 2.25* |

| Group III | 2.18 ± 0.83 | 20.72 ± 2.04 | 12.36 ± 1.89 |

| Group IV | 2.56 ± 0.77 | 19.36 ± 1.78** | 9.21 ± 0.97** |

Note: Group I (Sham group, underwent cannulation + heparinization only); Group II (CPB group, underwent 60-minutes of normothermic of CPB procedure only); Group III (Low-dose group, underwent 60-minutes of normothermic of CPB which rats administered daily with 30 mg/kg DOX orally one week ahead of CPB); Group IV (High-dose group, underwent 60-minutes of normothermic of CPB which rats administered daily with 60 mg/kg DOX orally one week ahead of CPB). T1 the termination of CPB; T2 6 h after termination of CPB;

P < 0.05 vs all groups at the corresponding time points;

P < 0.05 vs group II and III at T2 time point.

Activity of MMP-9 in BALF

The expression of activity of MMP-9 in the BALF was detected by Western-blot analysis. In CPB group, activity of MMP-9 was significantly increased compared with sham group respectively (T1: 1.04 ± 0.11 vs. 1.22 ± 0.07, P < 0.05; 0.90 ± 0.17 vs. 1.33 ± 0.28, P < 0.01). High-dose DOX therapy (group IV) could suppress MMP-9 activity in BALF compared to CPB group at T2 time point (1.17 ± 0.12 vs. 0.90 ± 0.17, P < 0.01); but at T1 time point, there was no difference between them (1.09 ± 0.11 vs. 1.01 ± 0.12, P = 0. 43). The suppression of MMP-9 activity was not obvious in low-dose group from statistical analysis (Figure 4A, 4B).

Figure 4.

The activity of MMP-9 in BALF by Western-blot analysis. A. Picture of activity of MMP-9 by Western-blot; B. Quantification of BALF levels of MMP-9 by Western-blot. Activity of MMP-9 was significantly increased compared with sham group respectively. High-dose DOX could suppress MMP-9 activity at T2 time point. Data are means ± SD, *P < 0.01 versus I T2 and IV T2 time point.

Lung tissue levels of MMP-9

Representative slides of immunohistochemical staining for MMP-9 from four groups demonstrating varying immunoreactivity grades are depicted in Figure 5. The levels of MMP-9 in the alveolar tissue following CPB were expressed strongly as compared with sham group and DOX groups. DOX administration significantly reduced the levels of MMP-9 in alveolar tissue in a dosedependent fashion (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical staining for lung tissue MMP-9 levels (×200 times). A. Representative slide from the sham group demonstrating an immunoreactivity grade of 0-1, representing absence of MMP-9 in alveolar tissue. B. Representative slide from the CPB group demonstrating an immunoreactivity grade of 4, representing a strongly abundant presence of MMP-9 in alveolar tissue. C. Representative slide from the low-dose DOX group demonstrating an immunoreactivity grade of 2, representing MMP-9 in alveolar tissue was suppressed. D. Representative slide from the high-dose DOX group demonstrating an immunoreactivity grade of 1-2, representing MMP-9 in alveolar tissue was strongly suppressed.

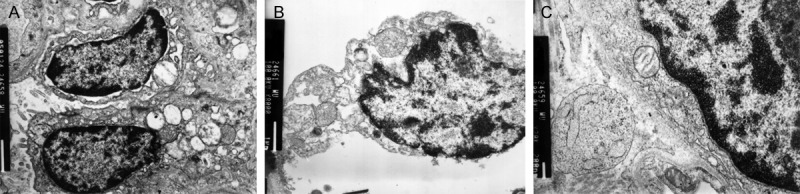

Ultrastructural change of lung tissue

In sham group, normal pathological including rich microvilli, mitochondria and reticulum was observed and the alveolar epithelial walls were well maintained (Figure 6A). Figure 6B was the representative slide from the CPB group demonstrating obvious lung injury marked alveolar epithelial cell shedding, matrix exposure, vascular congestion, mitochondria of epithelial cells swelling obviously. In DOX treated group, the pathologic changes were improved significantly. The alveolar epithelial walls were relatively maintained and the desmosomes and microvilli were observed, and the mitochondria and reticulum increased in cytoplasm (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Ultrastructure change of lung tissue. A. Sham group demonstrating normal pathological and the alveolar epithelial walls were well maintained. B. Representative section from CPB group demonstrating lung tissue obvious injury marked alveolar epithelial cell shedding, matrix exposure, vascular congestion, mitochondria of epithelial cells swelling obviously. C. DOX treatment group demonstrating lung tissue injury was improved and the alveolar epithelial walls were relatively maintained.

Discussion

The most significant findings in this study are that the DOX suppresses the expression of MMP-9 in the plasma and alveolar tissue and improves the lung injury following CPB. These data correlate and support findings from previous studies that demonstrated reduction of lung injury with tetracyclines in other CPB models [13,14]. Additionally, to our knowledge, this study adds further support to the role of proteolytic enzymes in the development of CPB-induced pulmonary injury.

Postoperative acute lung injury following CPB continues to represent a significant challenge to cardiac surgeons and physicians in the intensive care unit. Despite extensive research efforts, such as the progress of surgical technology, the improvement of material used in CPB and the new drug intervention, the CPB induced pulmonary damage remains inevitable and has been shown to affect the recovery of patients seriously, even threaten the life. Acute lung injury is a clinical and pathological entity characterized by diffuse alveolar-capillary wall damage causing severe impairment in oxygenation [15]. Cardiopulmonary bypass has been shown to exert an inflammatory response within the lung, often resulting in postoperative acute lung injury [16]. The causes of ALI following CPB are sophisticated, including CPB procedure, anesthesia, transfusion et al, and the development of ALI requires an initiator stage, which involves the release of a multitude of inflammatory mediators that promote neutrophil sequestration in the pulmonary vasculature.

The activation of sequestered neutrophils is the final common pathway which termed the effector phase. The hallmark of the effector phase is the release of proteolytic enzymes or proteases (specifically neutrophil elastase and MMPs) that normally serve as a host defense mechanism against pathogens. MMPs are known to involve in almost all stages of the inflammatory response and in extracellular matrix remodeling [17] and are capable of degrading components of the alveolar extracellular basement membrane, thus allowing for permeability changes between the alveolar epithelial and pulmonary vascular endothelial border in inflamed lungs [18]. The data from this study supports the role of MMP-9 in the pathogenesis of ALI secondary to CPB.

Doxycycline is in market for over 30 years, in many long term uses without significant toxicities [19] and is used for attenuating MMP activity [20]. The effect of doxycycline on MMPs was achieved by binding to Ca2+/Zn2+ at catalytic sites of MMP and inhibits the enzymatic activity of MMPs [21]. As an inhibitor of MMP-9, doxycycline was evaluated in various pathologic conditions and inflammatory models [10,22]. In a high volume ventilation-induced lung injury (VILI) model, Adrian Doroszko et al found treatment with doxycycline resulted in a decrease of pulmonary MMP-9 activity as well as in an increase in the levels of several proteins by the pharmacoproteomic approach, and conclude administration of doxycycline might be a significant supportive therapeutic strategy in prevention of VILI [23]. Recently, Bretz WA et al [24] observed the clinical effect of doxycycline on markers of systemic inflammation in postmenopausal women with periodontitis. In this study, in the rat model of CPB, the activity and concentration of lung tissue MMP-9 was suppressed by doxycycline significantly, and the effect of DOX was dose dependent.

In our present study, another goal was to assess the effect of DOX on pulmonary injury following CPB. Proinflammatory cytokines were important mediators in ALI following CPB, and increased in the lung contents of TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-8 during and after CPB [17]. Various of factors concerned inflammation, not only the changes in the levels, but also the time courses or the patterns of release, had been described for the affecting the incidence, severity and clinical outcome of the CPB-ALI. In this study, the effect of DOX on the BALF levels of TNF-α and IL-1β was significant and the change in the concentrations and time courses was dose dependent. Our data also demonstrated that the administration of DOX attenuated CPB-induced edematous changes in the lung, and maintained lower W/D weight ratio. The microscopic structural of the lung by the electron microscopy analysis was improved with the administration of DOX.

In conclusion, we investigated the effects of doxycycline on expression of MMP-9 in lung tissue and the lung injury following CPB in the rat model. Our study described the DOX could suppress the expression of MMP-9 and cytokines, and improve the lung injury following CPB. As the treatment strategy of inhibiting the effector stage mentioned previously, DOX might represent a novel strategy for the prevention of secondary pulmonary complications following CPB. Further studies should be warranted to determine the mechanism of doxycycline on MMPs.

This study has several limitations. Several other time points of sample collection should be added to investigate the time and dose dependent effect of DOX to MMP-9 and lung injury. More time points and more doses will be more accurate to determine the time and dose dependent effect of DOX. The survival rates of experimental animals should be investigated to evaluate the effect of DOX in prophylaxis and treatment the ALI. These questions will be addressed in further studies by our group.

Acknowledgements

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Taggart DP, el-Fiky M, Carter R, Bowman A, Wheatley DJ. Respiratory dysfunction after uncomplicated cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;56:1123–1128. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)90029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apostolakis E, Filos KS, Koletsis E, Dougenis D. Lung dysfunction following cardiopulmonary bypass. J Card Surg. 2010;25:47–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2009.00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imura H, Caputo M, Lim K, Ochi M, Suleiman MS, Shimizu K, Angelini GD. Pulmonary injury after cardiopulmonary bypass: beneficial effects of low-frequency mechanical ventilation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:1530–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Owen CA, Campbell EJ. The cell biology of leukocyte-mediated proteolysis. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;65:137–50. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hijova E. Matrix metalloproteinases: their biological functions and clinical implications. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2005;106:127–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sternlicht MD, Werb Z. How matrix metalloproteinases regulate cell behavior. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:463–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golub LM, Ramamurthy NS, McNamara TF, Greenwald RA, Rifkin BR. Tetracyclines inhibit connective tissue breakdown: new therapeutic implications for an old family of drugs. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1991;2:297–321. doi: 10.1177/10454411910020030201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golub LM, Lee HM, Ryan ME, Giannobile WV, Payne J, Sorsa T. Tetracyclines inhibit connective tissue breakdown by multiple nonantimicrobial mechanisms. Adv Dent Res. 1998;12:12–26. doi: 10.1177/08959374980120010501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mishra A, Bhattacharya P, Paul S, Paul R, Swarnakar S. An alternative therapy for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis by doxycycline through matrix metalloproteinase inhibition. Lung India. 2011;28:174–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.83972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sochor M, Richter S, Schmidt A, Hempel S, Hopt UT, Keck T. Inhibition of Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 with Doxycycline Reduces Pancreatitis-Associated Lung Injury. Digestion. 2009;80:65–73. doi: 10.1159/000212080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong GH, Xu B, Wang CT, Qian JJ, Liu H, Huang G, Jing H. A rat model of cardiopulmonary bypass with excellent survival. J Surg Res. 2005;123:171–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinberg J, Halter J, Schiller HJ, Dasilva M, Landas S, Gatto LA, Maisi P, Sorsa T, Rajamaki M, Lee HM, Nieman GF. Metalloproteinase inhibition reduces lung injury and improves survival after cecal ligation and puncture in rats. J Surg Res. 2003;111:185–95. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4804(03)00089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carney DE, Lutz CJ, Picone AL, Gatto LA, Ramamurthy NS, Golub LM, Simon SR, Searles B, Paskanik A, Snyder K, Finck C, Schiller HJ, Nieman GF. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor prevents acute lung injury after cardiopulmonary bypass. Circulation. 1999;100:400–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.4.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang C, Li D, Qian Y, Wang J, Jing H. Increased matrix metalloproteinase-9 activity and mRNA expression in lung injury following cardiopulmonary bypass. Lab Invest. 2012;92:910–6. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2012.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1334–1349. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edmunds LH Jr. Inflammatory response to cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:S12–16. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)00967-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanlaere I, Libert C. Matrix metalloproteinases as drug targets in infections caused by gram-negative bacteria and in septic shock. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:224–39. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00047-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamamoto M, Suga M, Nakatani T, Takahashi Y, Sato Y, Inamori S, Yagihara T, Kitamura S. Phosphodiesterase type 4 inhibitor prevents acute lung injury induced by cardiopulmonary bypass in a rat model. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;25:833–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calza L, Attard L, Manfredi R, Chiodo F. Doxycycline and chloroquine as treatment for chronic Q fever endocarditis. J Infect. 2002;45:127–9. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2002.0984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curci JA, Mao D, Bohner DG, Allen BT, Rubin BG, Reilly JM, Sicard GA, Thompson RW. Preoperative treatment with doxycycline reduces aortic wall expression and activation of matrix metalloproteinases in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31:325–342. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(00)90163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bendeck MP, Conte M, Zhang M, Nili N, Strauss BH, Farwell SM. Doxcycycline modulates smooth muscle cell growth, migration, and matrix remodeling after arterial injury. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1089–95. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64929-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee CZ, Xu B, Hashimoto T, McCulloch CE, Yang GY, Young WL. Doxycycline suppresses cerebral matrix metalloproteinase-9 and angiogenesis induced by focal hyperstimulation of vascular endothelial growth factor in a mouse model. Stroke. 2004;35:1715–1719. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000129334.05181.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doroszko A, Hurst TS, Polewicz D, Sawicka J, Fert-Bober J, Johnson DH, Sawicki G. Effects of MMP-9 inhibition by doxycycline on proteome of lungs in high tidal volume mechanical ventilation-induced acute lung injury. Proteome Sci. 2010;8:3. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-8-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bretz WA. Low-dose doxycycline plus additional therapies may lower systemic inflammation in postmenopausal women with periodontitis. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2012;12:67–8. doi: 10.1016/S1532-3382(12)70016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]