Abstract

BACKGROUND

Advanced lung cancer (LC) patients and their families report low self-efficacy for self-care/caregiving and high rates of distress, yet few programs exist to address their supportive care needs during treatment.

OBJECTIVE

This pilot study examined the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a 6-session telephone-based dyadic psychosocial intervention that we developed for advanced LC patients and their caregivers. The program is grounded by Self-determination Theory (SDT), which emphasizes the importance of competence (self-efficacy), autonomy (sense of choice/volition), and relatedness (sense of belonging/connection) for psychological functioning. Primary outcomes were psychological functioning (depression/anxiety) and caregiver burden. Secondary outcomes were the SDT constructs of competence, autonomy, and relatedness.

METHODS

Thirty-nine advanced LC patients who were within one month of treatment initiation (baseline) and their caregivers (51% spouses/partners) completed surveys and were randomized to the intervention or usual medical care. Eight weeks post-baseline, they completed follow-up surveys.

RESULTS

Solid recruitment (60%) and low attrition rates demonstrated feasibility. Strong program evaluations (X̄=8.6 out of 10) and homework completion rates (88%) supported acceptability. Participants receiving intervention evidenced significant (p<.0001) improvements in depression, anxiety, and caregiver burden relative to usual medical care. Large effect sizes (d>1.2) favoring the intervention were also found for patient and caregiver competence and relatedness, and for caregiver autonomous motivation for providing care.

CONCLUSION

These findings support intervention feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy. By empowering families with skills to coordinate care and meet the challenges of LC together, this intervention holds great promise for improving palliative/supportive care services in cancer.

Keywords: lung cancer, psychosocial intervention, psychological distress, caregivers, supportive care, palliative care, couples

Background

Lung cancer (LC) is the second most common cancer and leading cause of cancer death in the United States.1 Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common type and often presents at an advanced stage (III and IV).2 Likewise, 70% of small cell lung cancer (SCLC) cases are diagnosed at an advanced/extensive stage. Unfortunately, prognosis is extremely poor. Median survival is approximately 12 months for advanced LC.3 In addition, patients with advanced LC experience higher rates of physical and emotional distress relative to patients with other cancers.4, 5 This not only contributes to their suffering but also to the suffering of their families who play a key role in providing care and emotional support.6 Now that early integration of palliative care with standard oncologic care has been shown to improve quality of life (QOL) and possibly survival in advanced LC,7 practice guidelines have changed to advocate that patients receive concurrent palliative and standard oncologic care from point of diagnosis.8, 9 Although support for the family is deeply ingrained in palliative care philosophy,10 the reality is that the support provided to families is often suboptimal.11 Despite outpatient palliative care services, the families of LC patients are often unprepared for caregiving,12 have low self-efficacy for managing patient symptoms at home,13 report high rates of distress,14 and have a number of unmet supportive care needs.12 LC also adversely affects family relationships. Both patients and caregivers have reported decreased closeness15 and increased conflict regarding symptom management after diagnosis.16 To date, only a handful of randomized controlled trials of psychosocial interventions for advanced cancer patients and/or their family members have been conducted.17–21 Most have targeted families in hospice (not undergoing cancer-directed treatment) and have not addressed the specific challenges of LC. Programs that address these gaps may not only improve patient and caregiver QOL, but also the quality of palliative and supportive care services that are offered in cancer.

We developed a dyadic intervention that seeks to improve the QOL of advanced LC patients and their caregivers. The program is telephone-based to reduce burden and is grounded by Self Determination Theory (SDT).22 Given that SDT emphasizes the need for individuals’ to develop a sense of competence (self-efficacy), autonomy (a sense of choice and volition), and relatedness (a sense of belonging and connection) for psychological functioning, the intervention: 1) teaches skills to enhance patient and caregiver competence for self-care, coping with cancer, and managing symptoms at home; 2) supports patient/caregiver autonomy by providing a clear rationale for recommendations and a variety of options to encourage choice and elaboration; and, 3) seeks to improve interpersonal connections or the sense of relatedness by teaching patients and caregivers strategies for problem solving, effective communication, and mobilizing support/maintaining supportive relationships.

This study tested the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of the dyadic intervention that we developed. We expected it would be feasible as assessed through adequate recruitment, retention, and completion of sessions. We also expected that it would be acceptable as assessed through participant evaluations. With regard to preliminary efficacy, we hypothesized that, compared to patients and caregivers receiving usual medical care (UMC), those receiving intervention would show greater improvements on the primary outcomes of psychological functioning (i.e., depression, anxiety) and caregiver burden. Finally, we hypothesized that patients and caregivers receiving intervention would report greater improvements on the secondary outcomes (SDT constructs) of autonomy, competence, and relatedness relative to those receiving UMC.

Methods

Participants

Patients were eligible if they 1) had advanced LC and were within one month of treatment initiation (any line of therapy); 2) were spending more than 50% of time out of bed on a daily basis, as measured by an ECOG Performance Status of ≤ 2; and 3) had a spouse/partner or other close family member who they identified as their primary caregiver. In addition, both patients and caregivers had to: 4) be ≥ 18 years old; 5) have the ability to read and understand English; and, 6) be able to provide informed consent.

Procedures

The study was reviewed and approved by the Mount Sinai Institutional Review Board. Patients were identified through medical chart review and approached to participate during chemotherapy infusion. If caregivers were not present, permission was obtained to contact them by phone. Interested dyads provided informed consent, independently completed baseline paper-and-pencil surveys, and were randomly assigned to either the 6-week intervention or UMC. Participants in both conditions completed follow-up paper-and-pencil surveys 8 weeks post-baseline and received $20 gift cards upon return of each completed survey.

Measures

Primary Outcomes

Psychological functioning

The 6-item PROMIS short-form depression measure assesses negative mood and views of the self.23 The 6-item PROMIS short-form anxiety measure assesses fear, anxious misery (e.g., worry), and hyperarousal.23 For both measures, the time frame is “the past 7 days”; responses range from 1 (never) to 5 (always) and are summed to form a raw score that can then be rescaled into a T-score (standardized) with a mean of 50 and standard deviation (SD) of 10 using tables available through the PROMIS website. Thus, a T-score of 60 is 1SD above the mean, and a T-score of 40 is 1SD below the mean. In this study, internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) for depression was αpatients=.96 and αcaregivers=.97, and for anxiety it was α=.93 for patients and caregivers.

Caregiver burden

The 12-item short-form of the Zarit Burden interview 24 taps the constructs of personal and role strain. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 0 (never) to 4 (nearly always). Cronbach’s alpha was .87.

Secondary Outcomes

Autonomy

Five items developed by Pierce25 assessed caregivers’ autonomous motivation for tending to patient needs and providing care on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Cronbach’s alpha was .78. Six items from the Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire26 assessed patient autonomy for engaging in self-care on a 7-point Likert-type scale; higher scores indicate greater endorsement.27 Cronbach’s alpha was .80.

Competence

We developed 38 items based on Lorig28 in which patients and caregivers rated on a scale of 0 (not at all confident) to 10 (totally confident) their self-efficacy for: seeking and understanding medical information, managing stress, affective regulation, managing physical symptoms, seeking support, and working together as a team. In this study, internal consistency reliability was αpatients=.98 and αcaregivers=.93.

Relatedness

Relatedness was assessed with a 4-item measure that assesses the quality of the caregiver–care recipient relationship.29 Items assess closeness, the ability to communicate, similarity of views, and the degree to which family members get along on a scale from 1 (not at all close/similar/well) to 4 (very close/similar/well). Cronbach’s alpha was .85 for patients and caregivers.

Feasibility, Acceptability, and Treatment Fidelity

Feasibility was assessed through rates of study enrollment and participation. Acceptability was measured through reports of the number of homework assignments completed and post-treatment ratings of the overall ease of participation, helpfulness of the program, and relevance of the information provided (0=not easy/helpful/relevant to 10=extremely easy/helpful/relevant). Participants also rated their liking of the dyadic format, telephone-based delivery, study materials, homeworks, and the interventionist (1=completely disagree to 10=completely agree). Finally, an open-ended question asked about suggestions for improvement.

A fidelity checklist was created that comprised the session topics covered, whether in-session exercises were conducted, and whether home assignments were given. The fidelity score consisted of the number of topics divided by the total number of fidelity criteria.

Study Conditions

UMC

At Mount Sinai, UMC consists of standard oncologic and primary palliative care for the patient from the point of diagnosis of advanced LC. Primary palliative care is provided by the patient’s medical oncologist and includes the basic management of pain and other symptoms including depression and anxiety, as well as basic discussions about prognosis and goals of treatment. In addition, patients may be referred to the outpatient supportive oncology practice for a specialty palliative care consultation based on need as determined by the treating oncologist. This consult follows the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care guidelines.30 Caregivers are welcome to attend/participate, but are not required to do so. The supportive oncology practice provides assistance as needed in the management of pain and other symptoms, existential distress, and regarding goals of care. Psychiatry, social work, and home-based visiting nurse association services are available for patients on referral. Chaplaincy and other integrative services (e.g., massage/art therapy) are also available and require referral from the primary medical oncologist.

Intervention (INT)

We created separate standardized tailored intervention manuals for patients and caregivers. The manuals were divided into 6 sections. Topics were: self-care, stress and coping, symptom management, effective communication, problem-solving, and maintaining and enhancing relationships. For each topic, approximately half the content was the same for patients and caregivers, and half was tailored based on the person’s role (patient or caregiver). For example, shared content included information about self-care and symptom management, strategies for coping as a team (e.g., joint problem-solving), relationship maintenance strategies, and cognitive-behavioral strategies for managing depression and anxiety symptoms (e.g., cognitive reframing, relaxation). Tailored content for patients included strategies for balancing autonomy with soliciting/accepting support, disclosing care/support needs, and supporting/acknowledging the caregiver. Tailored content for caregivers included strategies for minimizing overprotection and negative interaction patterns (e.g., nagging, criticizing) and for supporting the patient’s self-care goals.

In addition to UMC, patients and caregivers in INT received their own tailored intervention manual and participated together in 6 weekly 60-minute telephone counseling sessions with a trained interventionist who had a master’s degree in mental health counseling. During sessions, the interventionist reviewed homework and manual content for that week, guided participants through in-session activities, and assigned the next week’s homework to reinforce practice of skills taught.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses examined recruitment rates, baseline (T0) and follow-up (T1) means for the two conditions, and feasibility and acceptability measures. Baseline comparisons (Chi-square, t-tests) examined differences between the INT and UMC groups (for patients and caregivers separately); possible gender differences were also examined. Pearson correlations among the outcome variables and partial correlations between patients and caregivers were also examined.

To test the preliminary efficacy of INT, we performed analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) with T0 scores as covariates and follow-up T1 outcome scores as dependent variables. The main effects tested were treatment group (INT or UMC) and role (patient or caregiver). We also examined the treatment group X role interaction. Gender was not included in the model because there were no significant differences between men and women on the study outcomes. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated for significant findings at T1 using the formula where X̄INT is the mean for the intervention group at T1, X̄UMC is the mean of the control group at T1 and s is the pooled SD for the two groups.31

To gauge the clinical significance of the treatment effects, we identified patients and caregivers in the INT and UMC groups who had high levels of depression and anxiety (T-scores above 60 or 1SD on the PROMIS measures). The proportion scoring above 1SD in the INT and UMC groups who improved (i.e., their T-score moved from ≥ 1SD to < 1SD) versus those who remained stable or got worse from T0 to T1 was then examined using Chi-square analyses.

Results

Feasibility and Acceptability

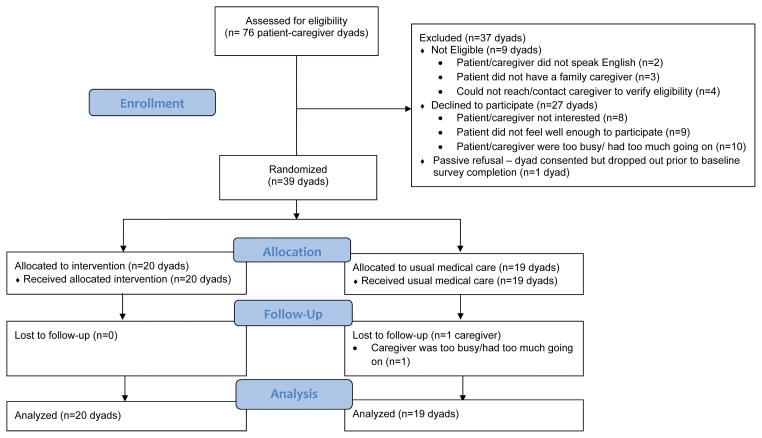

Study enrollment and participation. As Figure 1 shows, 76 patient-caregiver dyads were screened and 9 were excluded due to one of the dyad members not being eligible. Of the remaining 67 eligible dyads, 40 (60%) consented. There were no significant differences between participants and refusers on demographic or medical characteristics. The primary reasons for refusal were either that the patient/caregiver or both were not interested or that they had too much going on. One dyad dropped out before returning the baseline survey; the patient did not feel well-enough to participate. Of the remaining 39 dyads, 20 were randomized to INT and 19 to UMC. Telephone session attendance was high; in 90% of cases both the patient and caregiver participated on the call together, in 10% of cases, one of the dyad members missed the call and a make-up call was scheduled with that individual prior to the next session. In all cases, missed sessions were due to scheduling conflicts and make-ups were completed. All the patients and caregivers in INT completed the follow-up, as did all patients and 95% of the caregivers receiving UMC. Sessions generally occurred weekly; total duration averaged 6.5 weeks (SD=.20). Dyads completed an average of 4.4 out of 5 homeworks (SD=.20, Range=2 to 5).

Figure 1.

Treatment fidelity and program evaluation

All sessions were digitally recorded and fidelity was rated on 25% of sessions. The average fidelity rating was 86%. Participants rated the program favorably in terms of convenience, helpfulness, and relevance (see Table 3). They also rated the interventionist highly. Although most patients and caregivers said they enjoyed participating in the program together, they also noted they would have preferred some joint/dyadic and some one-on-one sessions with the interventionist. Reasons were to: (1) discuss topics they were uncomfortable discussing in front of their loved one; (2) gain more skills practice by working individually with the interventionist; and, (3) scheduling convenience.

Table 3.

Treatment Evaluations (N=20 patients, 18 caregivers)

| Patients M(SD) |

Caregivers M(SD) |

|

|---|---|---|

| How interesting were the sessions? | 8.1(1.5) | 8.5(1.5) |

| How helpful were the sessions? | 7.7(1.3) | 8.1(1.6) |

| How useful was the manual? | 9.6(.3) | 9.1(.7) |

| How relevant was the material covered to what you are experiencing? | 8.9(1.4) | 9.3 (.7) |

| How helpful was the interventionist? | 8.8(.9) | 8.5(1.4) |

| How likely is that you would recommend the program to another patient/caregiver? | 8.8(1.1) | 8.2(1.3) |

| How convenient was it to participate by telephone? | 9.1(.8) | 9.5(.8) |

| How helpful were the homework assignments? | 8.4(1.1) | 8.4(1.0) |

| How much did you enjoy participating in this program with your patient/caregiver? | 9.4(.6) | 9.0(1.0) |

| How much did you like the telephone delivery format? | 7.9(1.5) | 9.2(.6) |

| How much did you enjoy the dyadic format (i.e., patient and caregiver participate in ALL sessions together)? | 6.1(2.9) | 5.7(2.4) |

| Overall, how satisfied are you with the program? | 8.5(1.0) | 8.6(1.0) |

M=Mean, SD=Standard deviation; All ratings were on a 0 to 10 scale with higher scores indicating greater endorsement.

Participant Characteristics

Baseline demographic and medical data are in Table 1. Patients were mostly female (74%), White (85%), educated with at least some college credits (86%), elderly (X̄=68.17, SD=10.30), and unemployed/retired (62%); 84% had NSCLC. Caregivers were also mostly female (69%), educated with at least some college credits (95%), middle aged (X̄=51.10, SD=10.24), and employed at least part-time (77%); 51% were spouses/partners, the rest were either siblings or adult sons/daughters of the patient. No significant baseline differences on medical or outcome variables were found for patients randomized to INT or UMC (p-values≥.11).

Table 1.

Description of Study Sample (N=39 patient-caregiver dyads)

| Patients | Family Caregivers | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (%) | ||

| Male | 10 (26) | 12 (31) |

| Female | 29 (74) | 27 (69) |

| Age in years | X̄=68.17, SD=10.30 (Range=38 to 87) | X̄=51.10, SD=10.24 (Range=35 to 70) |

| Race* (%) | ||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 33(85%) | |

| Employment Status | ||

| Employed full-time | 6(15) | 14(36) |

| Employed part-time | 9(23) | 16(41) |

| Unemployed/retired | 24(62) | 9(23) |

| Education | ||

| High school diploma or less | 5(14) | 2(5) |

| At least some college | 15(38) | 13(33) |

| College degree | 19(48) | 24(62) |

| Caregiver Relationship to the Patient (%) | ||

| Spouse/Partner | 20(51) | |

| Son/Daughter | 12(31) | |

| Other Family Member (i.e., sibling, cousin, parent) | 7(18) | |

| Married (%) | 23(59%) | |

| Length of marriage in years | X̄=36.20, SD=8.70 (Range=18 to 51) | |

| Type of lung cancer (%) | ||

| Small Cell (SCLC) | 6(16) | |

| Non-Small Cell (NSCLC) | 33(84) | |

| Stage of cancer (%) | ||

| Stage 3 NSCLC | 10 (26) | |

| Stage 4 NSCLC | 23 (58) | |

| Extensive stage SCLC | 6 (16) | |

Race of the caregiver was not assessed.

At baseline, 33% of patients and 60% of caregivers had PROMIS Depression T-scores >60 (+1SD), indicating high levels of depression. In 23% of dyads, both patient and caregiver scored above 60. Also at baseline, 46% of patients and 69% of caregivers had PROMIS Anxiety T-scores >60, indicating high levels of anxiety. In 33% of dyads, both patient and caregiver scored above 60. As Table 2 shows, all correlations were in the expected directions. The partial correlations for patient and caregiver depression and anxiety were not significant.

Table 2.

Baseline Correlations (N=39 patients and 39 caregivers)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Depression | .30+ | .69** | -- | −.47** | −.60** | −.24 |

| 2. Anxiety | .75** | .21 | -- | −.39* | −.59** | −.19 |

| 3. Caregiver Burden | .47** | .35* | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 4. Autonomy1 | −.40* | .33* | −.20 | -- | .66** | .34* |

| 5. Competence | −.38* | −.37* | −.35* | .26+ | .46** | .21 |

| 6. Relatedness | −.12 | −.19 | −.27+ | −.01 | .20 | .66** |

Note: Partial correlations between patients and caregivers are in bold, on the diagonal. Correlations for patients are above the diagonal. Correlations for caregivers are below the diagonal.

Patient and caregiver autonomy were assessed using two different measures so partial correlations were not calculated.

p<.10,

p<.05,

p<.01

Preliminary Efficacy

Means for the primary and secondary outcomes at T0 and T1 are in Table 4.

Table 4.

Baseline and follow-up means and SDs on study outcomes for patients and caregivers in the INT and UMC groups

| Patients

|

Caregivers

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INT | UMC | INT | UMC | |||||

| Baseline M (SD) | Follow-up M (SD) | Baseline M (SD) | Follow-up M (SD) | Baseline M (SD) | Follow-up M (SD) | Baseline M (SD) | Follow-up M (SD) | |

| Depression1 | 14.75 (3.60) | 11.65 (3.77) | 14.74 (4.69) | 16.00 (5.69) | 16.45 (4.03) | 11.50 (3.20) | 16.26 (5.50) | 16.53 (5.47) |

| Anxiety1 | 14.95 (4.96) | 12.35 (4.46) | 14.79 (4.54) | 14.84 (4.96) | 17.40 (4.36) | 12.10 (3.60) | 17.42 (5.63) | 17.16 (5.41) |

| Caregiver Burden2 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 27.65 (5.46) | 24.70 (4.96) | 27.32 (6.28) | 28.16 (6.53) |

| Autonomy3 | 4.11 (1.29) | 4.83 (1.49) | 4.06 (1.42) | 4.35 (1.48) | 2.04 (.67) | 2.63 ( .65) | 2.23 ( .60) | 2.10 ( .62) |

| Competence4 | 4.75 (1.83) | 7.16 (1.42) | 4.68 (2.01) | 4.78 (1.95) | 4.68 (1.36) | 7.05 ( .98) | 4.50 ( .81) | 4.30 ( .69) |

| Relatedness5 | 11.00 (1.45) | 12.60 (1.39) | 11.26 (1.91) | 11.00 (2.08) | 11.10 (1.77) | 12.65 (1.69) | 11.21 (2.37) | 10.42 (2.39) |

Note: INT = Intervention; UMC=Usual Medical Care; M=Mean, SD=standard deviation

Raw scores for the PROMIS depression and anxiety measures are presented. Scores can range from 6 to 30; higher scores indicate greater anxiety/depression.

For the 12-item Zarit Caregiver Burden measure, scores can range from 0 to 48 – higher scores indicate greater burden.

Patient autonomous motivation for self-care was assessed on a 1 to 7 scale; caregiver autonomous motivation was assessed on a 0 to 4 scale. Higher scores indicate greater autonomous motivation.

Competence scores can range from 0 to 10; higher scores indicate greater competence. 5 Relatedness scores can range from 4 to 16; higher scores indicate greater relationship quality.

Primary Outcomes

Depression

At T1 there was a significant difference on depression (p<.0001), with the INT group having lower mean scores (less depressive symptomatology) than the UMC group. The effect size for this difference was Cohen’s d=−1.8, which is a large effect.32 There was also a significant main effect for role F(1,73)=4.55, p=.04, with caregivers reporting lower levels of depression at T1 than patients.

Anxiety

At T1 there was a significant difference on anxiety (p<.0001), with the INT group having lower mean scores (less anxiety) than the UMC group. The effect size was d=−1.3.

Caregiver burden

At T1 there was a significant difference in caregiver burden (p<.0001), with the INT group having lower mean scores (less caregiver burden) that the UMC group. The effect size was d=−2.5.

Secondary Outcomes

As Table 5 shows, with the exception of patient autonomy, significant main effects for group were found for all of the secondary outcomes at T1. Specifically, caregivers receiving INT had significantly higher scores on autonomy at T1, relative to caregivers receiving UMC (d=1.2). Likewise, patients and caregivers receiving INT had significantly higher scores on competence (d=2.6) and relatedness (d=2.2) at T1 relative to those receiving UMC.

Table 5.

Results of analyses of covariance for the study outcomes at baseline (T0) and follow-up (T1)

| Measure at T1 | Treatment Group | Role | Group X Role Interaction | Least square means | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| F-value | p-value | F-value | p-value | F-value | p-value | ||

| Depression | 72.13 | <.0001 | 4.55 | .04 | n.s. | n.s. | UMC=16.31, INT=11.53; Patients=14.53, Caregivers=13.31 |

| Anxiety | 34.34 | <.0001 | n.s. | n.s. | 3.46 | .07 | UMC=16.03, INT=12.20; UMCpatients=15.85, UMCcaregivers=16.20, INTpatients=13.24; INTcaregivers=11.16 |

| Caregiver Burden1 | 21.46 | <.0001 | -- | -- | -- | -- | UMC=28.32; INT=24.55 |

| Patient Autonomy1* | 3.13 | .09 | -- | -- | -- | -- | UMC=4.37; INT=4.81 |

| Caregiver Autonomy1* | 21.46 | <.0001 | -- | -- | -- | -- | UMC=2.03; INT=2.70 |

| Competence | 132.34 | <.0001 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | UMC=4.58; INT=7.07 |

| Relatedness | 63.66 | <.0001 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | UMC=10.63; INT=12.71 |

UMC=usual medical care, INT=Intervention, n.s.=not significant,

Analysis was not performed because only one partner (caregiver only or patient only) completed this measure;

Two different measures of autonomy were used for patients and caregivers. Specifically, we assessed patient autonomous motivation for self-care and caregiver autonomous motivation for providing care.

Clinical Significance

For caregivers with high depression levels (N=23), 2 of the 11 (18%) who received UMC improved (i.e., their T-score moved from ≥ 1SD to < 1SD) and 10 of the 12 (83%) who received INT improved (χ2=9.91, p=.01). For patients with high depression levels (N=13), 2 of the 6 (33%) who received UMC improved compared to 5 of the 7 (71%) who received INT (χ2=1.89, p=.39). For caregivers with high anxiety levels (N=27), 2 of the 12 (17%) who received UMC improved, compared to 10 of the 15 (67%) who received INT (χ2=8.44, p=.02). Finally, for patients with high anxiety levels (N=18), 2 of the 10 (20%) who received UMC improved, compared to 3 of the 8 (38%) who received INT (χ2=1.80, p=.41).

Discussion

This study supports the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a 6-session telephone-based dyadic psychosocial intervention that we developed for advanced LC patients and their caregivers. Our recruitment rate was 60%, which is comparable to rates reported by other telephone-based dyadic interventions in cancer33 and supports the feasibility of recruiting advanced LC patients on active treatment and their caregivers for this trial. Participants rated the intervention as relevant, convenient, and helpful. Retention was excellent and patients and caregivers completed the majority (88%) of the homework assignments, suggesting the intervention was highly acceptable. Large effect sizes were found for the impact of INT relative to UMC on the primary outcomes of patient and caregiver depression (d=−1.8), anxiety (d=−1.3), and caregiver burden (d=−2.5). Large effect sizes (d>1.2) for the impact of INT were also found for the secondary outcomes of patient and caregiver competence and relatedness, as well as for caregiver autonomous motivation for providing care. Finally, the proportion of highly depressed and anxious caregivers who experienced improvements in psychological functioning was significantly greater in the INT group relative to UMC.

Although effect sizes for most of the outcomes were large, there is room for improvement. Patient autonomy increased as a result of receiving intervention, but the effect was not statistically significant. Likewise, a greater number of the most distressed patients improved in the intervention group relative to UMC, but the difference was not significant. One explanation is that the small sample size and lack of extended follow-up limited our ability to detect differences. At the same time, many participants said they would have preferred not to have had all the telephone sessions together with their loved one. Thus, some patients may have held back concerns because their caregiver was present and this may have prevented them from fully benefiting from intervention. While the cancer literature shows that patients and caregivers have both individual and shared needs and concerns, the vast majority of dyadic interventions in cancer have been delivered to patients and caregivers together, which is more consistent with a couples’ therapy approach.33 Because acknowledging and addressing individuals’ unique and shared needs may enhance dyadic coping, it may not be sufficient solely to tailor intervention materials based on role. Thus, the next step in this research program will be to conduct a large-scale RCT where half of the sessions will be delivered to patients and caregivers together and half will be delivered separately. This should allow more: 1) in-depth coverage of tailored materials; 2) time with the interventionist to address individual needs/concerns; and, 3) time to practice skills and receive feedback, which may enhance program satisfaction and outcomes.

In terms of limitations, our sample was primarily white and relatively well-educated. The ability to generalize findings to other advanced LC populations is limited. We also did not collect data on the number of patients in both groups that were referred to the specialist palliative care team. We intend to address these issues in our future research and will continue to work to refine and shorten our 38-item measure of competence to reduce possible redundancies and participant burden. As initial support has now been obtained for our dyadic intervention, it is important to replicate findings with a larger sample size. A larger trial would make it possible to examine whether certain sub-groups are more likely to benefit and whether sociodemographic, medical, or relationship factors (e.g., whether the caregiver is a spouse/partner or other family member) moderate the effects of the intervention on study outcomes. Longer follow-up would allow us to examine the maintenance of effects after patients have undergone the first few rounds of treatment and have had more time to access and use existing palliative and supportive care services. Longer follow-up is also needed because it is possible that the clinically meaningful improvements seen in caregivers may precede and lead to improvements for patients over time. Given the dyadic nature of the study and the poor prognosis and fragility of this patient population, retention over an extended follow-up is likely to be challenging; however, given the rapid functional decline in advanced LC, it is important to determine how long intervention effects last, whether booster sessions are needed, and whether receiving intervention results in decreased healthcare utilization such as unnecessary hospital admissions (i.e., due to poor symptom control at home). It may also be useful to extend follow-up after the patient’s death to determine whether receiving intervention results in a less complicated bereavement for caregivers. Finally, in the future it will be important to explore what it is about INT that is of benefit and whether the “active ingredients” are the same for patients and caregivers.

Given that we chose to compare LC-STEPS to UMC instead of an attention control condition, it is possible that the improvements found were due to nonspecific effects. At the same time, if the aim of a trial is to determine whether an intervention is superior to existing practices (in this case, UMC), then it needs to be compared to those practices.34 Since the paramount consideration in choosing a control condition is how well it fits the purpose of the trial,35 and the goal of this preliminary efficacy trial was to push the envelope of efficacy to achieve better outcomes for patients and caregivers (not to differentiate between specific and nonspecific ingredients of the intervention), we believe that UMC was a reasonable and appropriate comparison condition. In the future, we would like to examine whether comparable outcomes can be achieved with a less expensive or intensive intervention, like the kind that might be employed in an attention control. That, however, is a comparative effectiveness question, and there would be no need for it unless LC-STEPS is first shown to be superior to UMC in a large, full-scale efficacy trial.

In conclusion, our findings provide evidence that dyadic psychosocial intervention is beneficial in the advanced LC population, improving both patient and caregiver psychological functioning during a very challenging and stressful time. They also suggest that such interventions have the potential to improve patient and caregiver self-efficacy for managing symptoms and working together as a team. Finally, our findings suggest that interventions that simultaneously target the patient and caregiver as individuals and as a dyad can result in improvements on both the individual (i.e., psychological functioning, self-efficacy) and dyadic (i.e., patient-caregiver relationship quality) levels. Given this and the fact that attending to the needs/concerns of patients and their family caregivers is an important component of quality end-of-life care, more research on ways to integrate dyadic and other family-based psychosocial interventions into oncology palliative and supportive care programs is warranted.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a pilot grant awarded to Dr. Badr under P30 AG028741 (Albert Siu, MD, Principal Investigator). The views represented in this paper are those of the authors and do not represent those of NIH, NIA, or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial disclosures.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mountain CF. Revisions in the international system for staging lung cancer. Chest. 1997;111:1710–1717. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.6.1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alberti W, Anderson G, Bartolucci A, et al. Chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis using updated data on individual patients from 52 randomised clinical trials. BMJ. 1995;311:899–909. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Degner LF, Sloan JA. Symptom distress in newly diagnosed ambulatory cancer patients and as a predictor of survival in lung cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 1995;10:423–431. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(95)00056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zabora J, Brintzenhofeszoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psycho-Oncology. 2001;10:19–28. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<19::aid-pon501>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bee PE, Barnes P, Luker KA. A systematic review of informal caregivers’ needs in providing home-based end-of-life care to people with cancer. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2009;18:1379–1393. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:880–887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ford DW, Koch KA, Ray DE, Selecky PA. Palliative and end-of-life care in lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: american college of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. CHEST Journal. 2013;143:e498S–e512S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies B, Reimer JC, Martens N. Family functioning and its implications for palliative care. Journal of Palliative Care. 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hudson P, Remedios C, Zordan R, et al. Guidelines for the psychosocial and bereavement support of family caregivers of palliative care patients. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2012;15:696–702. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakas T, Lewis RR, Parsons JE. Caregiving tasks among family caregivers of patients with lung cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2001;28 (5):847–854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Garst J, McBride CM, Baucom D. Self-efficacy for managing pain, symptoms, and function in patients with lung cancer and their informal caregivers: Associations with symptoms & distress. Pain. 2008;137:306. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carmack Taylor CL, Badr H, Lee L, et al. Lung cancer patients and their spouses: Psychological and relationship functioning within 1 month of treatment initiation. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;36:129–140. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9062-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooper ET. A pilot study on the effects of the diagnosis of lung cancer on family relationships. Cancer Nursing. 1984:301–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Badr H, Carmack Taylor C. Social constraints and spousal communication in lung cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15:673–683. doi: 10.1002/pon.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kissane D, McKenzie M, Bloch S, Moskowitz C, McKenzie D, O’Neill I. Family focused grief therapy: a randomized, controlled trial in palliative care and bereavement. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1208–1218. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.7.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLean LM, Walton T, Rodin G, Esplen MJ, Jones JM. A couple-based intervention for patients and caregivers facing end-stage cancer: outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Psycho-Oncology. 2011;22:28–38. doi: 10.1002/pon.2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keefe FJ, Ahles TA, Sutton L, et al. Partner-guided cancer pain management at the end of life: A preliminary study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2005;29:263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McMillan S, Small B, Schonwetter R, et al. Impact of a coping skills intervention with family caregivers of hospice patients with cancer: A randomized clinical trial. Cancer. 2006:105. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hudson PL, Aranda S, Hayman-White K. A psycho-educational intervention for family caregivers of patients receiving palliative care: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2005;30:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deci EL, Ryan RM. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry. 2000;11:227–268. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, Stover AM, Riley WT, Cella D. Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®): depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment. 2011;18:263–283. doi: 10.1177/1073191111411667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bédard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, Dubois S, Lever JA, O’Donnell M. The Zarit Burden Interview A New Short Version and Screening Version. The Gerontologist. 2001;41:652–657. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pierce T, Lydon JE, Yang S. Enthusiasm and moral commitment: What sustains family caregivers of those with dementia. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2001;23:29–41. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levesque C, Williams GC, Elliot D, Pickering MA, Bodenhamer B, Finley PJ. Validating the theoretical structure of the treatment self- regulation questionnaire (TSRQ) across three different health behaviors. Health Education Research. 2007;22:691–702. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levesque CS, Williams GC, Elliot D, Pickering MA, Bodenhamer B, Finley PJ. Validating the theoretical structure of the Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire (TSRQ) across three different health behaviors. Health Education Research. 2007;22:691–702. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lorig K, Stewart A, Ritter P, Gonzalez V, Laurent D, Lynch J. Outcome measures for health education and other health care interventions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawrence RH, Tennstedt SL, Assmann SF. Quality of the caregiver–care recipient relationship: Does it offset negative consequences of caregiving for family caregivers? Psychology and Aging. 1998;13:150. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.13.1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. (3) 2013 Available from URL: http://www.nationalconsensusproject.org/Guideline.pdf. [PubMed]

- 31.Rosnow RL, Rosenthal R. Computing contrasts, effect sizes, and counternulls on other people’s published data: general procedures for research consumers. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:331. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Badr H, Krebs P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for couples coping with cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22:1688–1704. doi: 10.1002/pon.3200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freedland KE, Mohr DC, Davidson KW, Schwartz JE. Usual and unusual care: existing practice control groups in randomized controlled trials of behavioral interventions. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2011;73:323–335. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318218e1fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wampold BE. The great psychotherapy debate: Models, methods, and findings. Routledge; 2001. [Google Scholar]