Abstract

Background

Assays identifying circulating tumor cells (CTC) allow noninvasive and sequential monitoring of the status of primary or metastatic tumors, potentially yielding clinically useful information. However, the effect of radiation therapy (RT) on CTC in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) to our knowledge has not been previously explored.

Methods

We describe here results of a pilot study of 30 NSCLC patients undergoing RT, from whom peripheral blood samples were assayed for CTC via an assay that identifies live cells, via an adenoviral probe that detects the elevated telomerase activity present in almost all cancer cells but not normal cells, and with validity of the assay confirmed with secondary tumor-specific markers. Patients were assayed prior to initiation of radiation (Pre-RT), during the RT treatment course, and/or after completion of radiation (Post-RT).

Results

The assay successfully detected CTC in the majority of patients, including 65% of patients prior to start of RT, and in patients with both EGFR wild type and mutation-positive tumors. Median counts in patients Pre-RT were 9.1 CTC/mL (range: undetectable - 571), significantly higher than the average Post-RT count of 0.6 CTC/mL (range: undetectable - 1.8) (p < 0.001). Sequential CTC counts were available in a subset of patients and demonstrated decreases after RT, except for a patient who subsequently developed distant failure.

Conclusions

These pilot data suggest that CTC counts appear to reflect response to RT for patients with localized NSCLC. Based on these promising results, we have launched a more comprehensive and detailed clinical trial.

Keywords: Circulating tumor cells, non-small cell lung cancer, telomerase, assay, biomarkers

INTRODUCTION

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which comprises 85–90% of all lung cancers, is the most common cause of cancer mortality in the United States with more than 224,000 individuals diagnosed each year.1 The 5-year overall survival rate for NSCLC has increased only 5.7% in the last four decades to 19.3%.2 Newer and biologically targeted agents offer renewed hope, especially when integrated into strategies that involve surgery, chemotherapy, improved imaging technology and advanced radiation therapy (RT). Improvements in the monitoring of disease to guide treatment decisions and patient management would likely further improve results.

Standard follow-up of patients after RT often includes history and physical exam as well as imaging, such as with chest computed tomography (CT). Post-radiation effects or fibrosis can resemble relapsed disease on imaging and thus decision making based on these results may sometimes be difficult.3–6 Re-biopsy or excision are often difficult or not possible, while procedures such as thoracentesis or bronchoscopy are invasive and accompanied by considerable risk. A reliable biomarker assay of disease status, especially if biologically relevant, non-invasive, and performed serially with low risk, could assist in diagnosis or treatment decisions.

Circulating tumor cell (CTC) assays have attracted intense interest as a biomarker that may assist in patient management. CTCs are continuously shed from primary or metastatic tumors; while the vast majority of CTCs will not become metastases, their identification and enumeration may enable serial interrogation of the status of solid tumors with minimal additional discomfort or risk to patients. For patients with NSCLC, the ideal CTC assay remains to be determined. Proposed assays have relied on cell surface marker detection (with epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) being most common) with or without operator cell morphology analysis and/or reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).7–20 In a meta-analysis of CTC levels in patients with NSCLC, elevated CTC levels appeared to be associated with increased tumor stage and poorer prognosis.16,17 However, EpCAM-based methods may be affected by variable EpCAM expression in different subtypes of NSCLC or downregulation of epithelial cell markers during epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT).21,22 RT-PCR-based methods may detect signal from circulating mRNA that are not cancer-derived. The only prior published study of CTC on patients receiving RT for NSCLC utilized RT-PCR-based detection, but which may lack certainty regarding the cancer cell origin of the signal detected.12 Other preliminary efforts have included surface-enhanced Raman scattering nanoparticles with epidermal growth factor peptide but have not been studied for NSCLC patients.23

In contrast, the novel NSCLC CTC assay described here, which relies on the detection of elevated telomerase activity in live cancer cells, may offer technical advantages that bypass current limitations. The assay incorporates an adenoviral probe that results in the expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) in CTCs within patient blood samples, thus enabling identification and enumeration using an automated computer imaging program. Telomerase is an enzyme considered to be the major contributor to cancer immortality by replenishing the ends of chromosomes, which shorten with successive DNA replication and forestall cellular senescence.21 Telomerase expression is elevated in almost all tumor cells but absent in almost all normal cells, characteristics which confers specificity to this probe.24 This technique thus has advantages that include: 1) a live cell assay not affected by nonviable cells or debris, and enabling counterstaining to confirm the cancer origin of the identified cancer cells, 2) telomerase-based detection that is specific to cancer cells even during EMT, and 3) an automated imaging program which increases efficiency of CTC analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Description of the Assay and Pilot Trial

The CTC assay has been previously described for patients with breast, glioma, and bladder cancer.25–29 Briefly, the probe utilized in the assay consists of the human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) promoter element driving the expression of adenoviral E1A and E1B genes, followed by a CMV promoter driving green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression. The preclinical validation process included studies presented in this manuscript (Figures 1, 2C–D), and also included testing of the probe in the blood drawn from healthy volunteers without cancer with and without spiking of NSCLC cells. This resulted in a data set that enabled a logistic regression- based classifier to be applied and which defines 1.3 GFP-expressing cells per mL of collected blood as the threshold for “CTC positivity” (a level delineated by the thin red line in Figure 3).

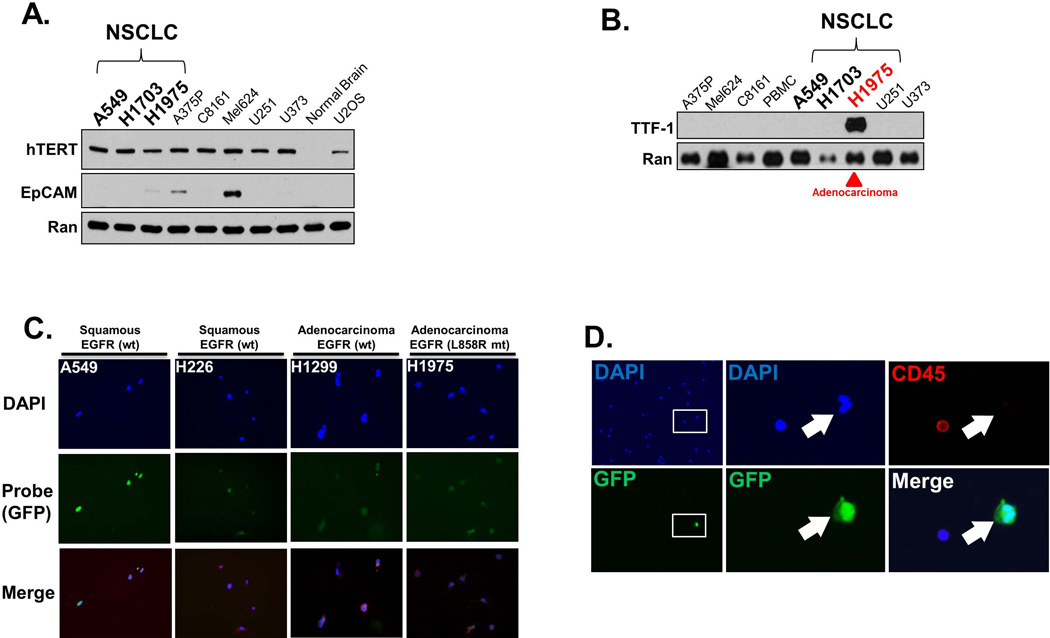

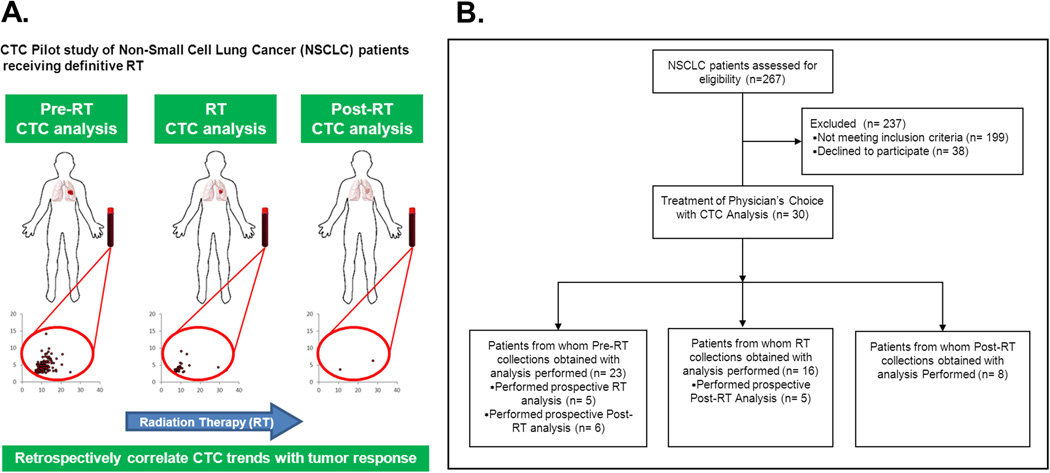

Figure 1. Preclinical and initial clinical validation of the Assay.

A. Human cancer cells, including NSCLC cells, express high levels of telomerase. High levels of human telomerase protein (hTERT) were found in all human cell lines tested, including NSCLC cell lines (A549, H1703, H1975), melanoma cells (A375P, C8161, Mel624), glioma (U251, U373) and sarcoma (U2OS). In contrast, hTERT was not appreciably expressed in normal brain tissue. Also of note, EpCAM was not detectable in any of the NSCLC cells. Western blotting was performed on lysates prepared from cell pellets of each cell line or tissue, with 20 ug of protein loaded in each lane, followed by probing for each respective protein. Probing for Ran protein served as the loading control. B. TTF-1 usefully serves as a marker of NSCLC adenocarcinoma. Lysates from each cell line was prepared as in A., but probed for TTF-1. Only H1975 cells, derived from a patient with adenocarcinoma of the lung, showed appreciable TTF-1 expression. C. The Assay is effective in all lung cancer cells tested and unaffected by EGFR mutation status. A representative panel of cell lines is shown (with the respective histology of origin and EGFR status (wt: wildtype, mt: mutant), with each cell line exposed to the probe, incubated for 24 hours, stained with the pan-nuclear stain DAPI, and imaged. The probe results in expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) in all cell lines. D. The Assay is effective in identifying tumor cells with high specificity in a peripheral blood sample from a patient with NSCLC. The blood sample was exposed to the Probe, incubated for 24 hours, fixed, and stained with DAPI (blue) and probed for the pan-leukocyte (white blood cells; WBC) marker CD45 (red). The rare circulating tumor cell is identifiable due to GFP expression induced by the probe. Left panels (top and bottom panels are of the same field) show the blood sample at low magnification, with the inset box shown at higher magnification in the middle panels. The middle panels show that the tumor cell (white arrow) expresses GFP, while the adjacent WBC does not. The right panels are of the identical cells shown in the middle panels, but showing CD45 expression (top) or GFP merged with DAPI. The WBC stains for CD45 while the tumor cell does not. E. TTF-1 usefully confirms the lung adenocarcinoma origin of CTCs identified by the Assay. A peripheral blood sample from a patient with adenocarcinoma NSCLC was exposed to the probe, incubated, fixed, and imaged as in D. with the exception that the sample was probed for the adenocarcinoma marker TTF-1. Each panel show the respective stain or GFP expression of the identical field of view, with the top panels are imaged at 20X while the bottom panels are imaged at 40X. The rare CTC is identified by GFP expression due to the probe, and which coincides with TTF-1 expression. In contrast, WBCs neither express GFP nor TTF-1.

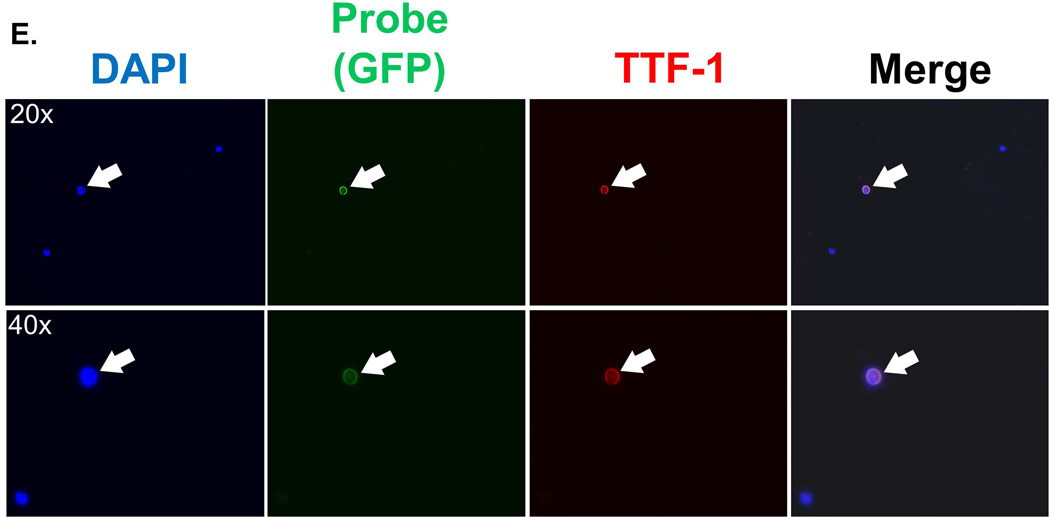

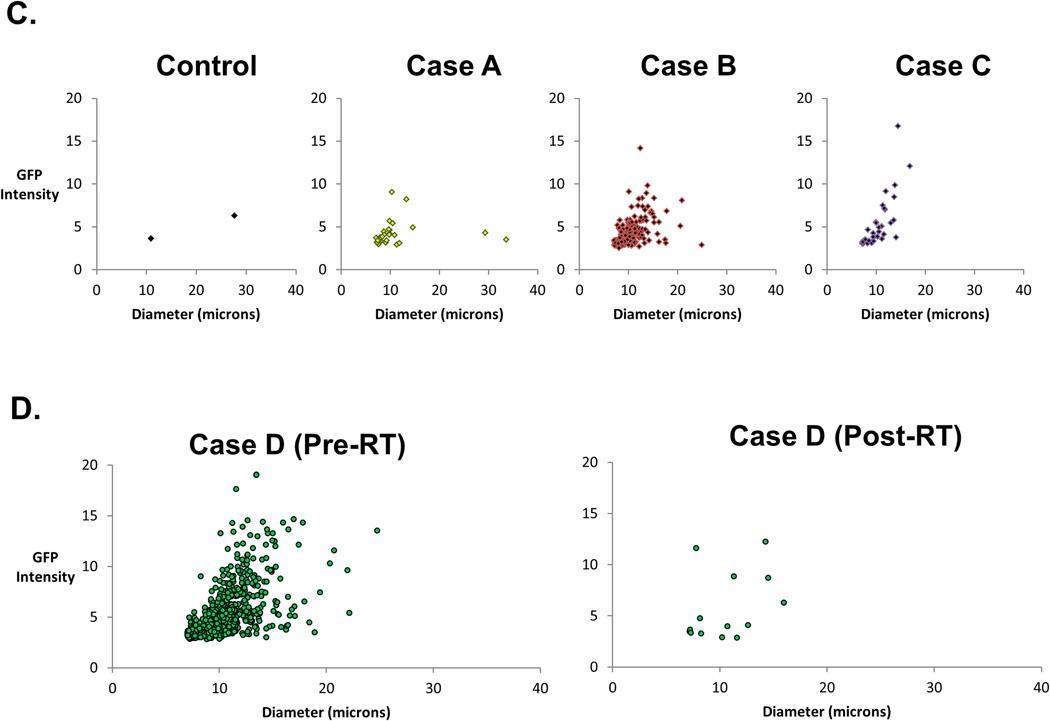

Figure 2. Descriptive schema and imaging of pilot trial in NSCLC patients receiving Radiation Therapy.

A. Overview schema of the trial, with sample collection and CTC analysis at the indicated phases of radiation therapy (RT): prior to initiation of RT (“Pre-RT”), during the RT course (on-treatment visit or “RT”), or following completion of RT (“Post-RT”). B. Flowchart showing the overview of the recruitment and CTC assessments (Consort Diagram of Prospective Clinical Study) C. Scattergrams showing the output from the imaging of blood samples from a healthy volunteer (Controls) or representative NSCLC patients referred for RT, with each dot representing a single cell. The X-axis of each graph indicates the tumor size, whereas the Y-axis shows fluorescent (GFP) intensity. The bottom pair of representative scattergrams contrasts the Pre-RT and Post-RT results from the same patient.

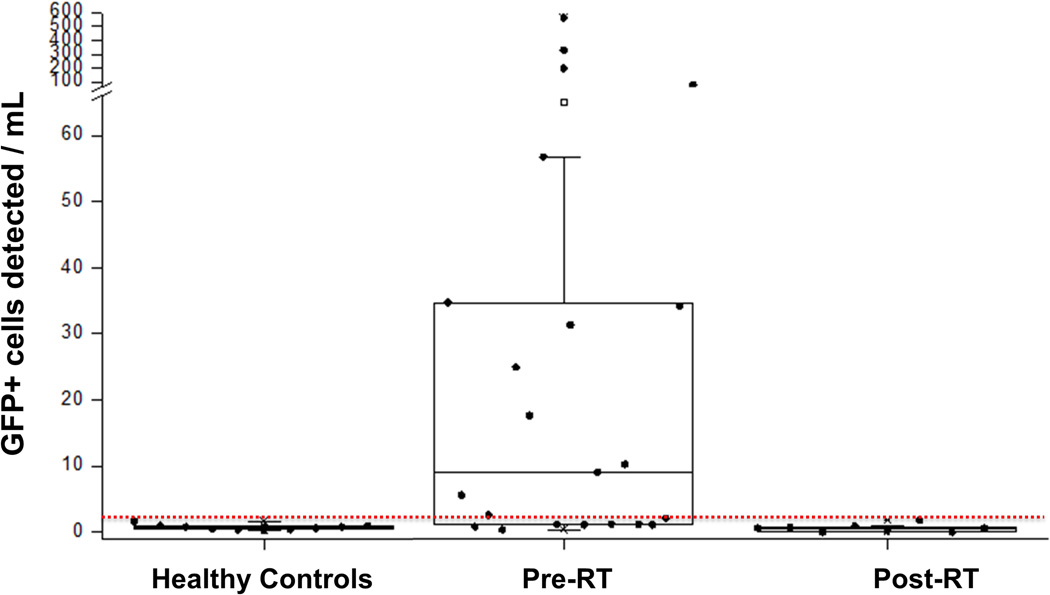

Figure 3. Cumulative results of the pilot trial of CTC analysis in NSCLC patients receiving Radiation Therapy.

Whisker plots showing the results of CTC analysis in all healthy controls and patients prior to the start of radiation therapy (“Pre-RT”) or after completion of RT(“Post-RT”). “T” indicates classifier threshold.

Patients were enrolled on an IRB-approved biomarker protocol. Pre-treatment specimens (Pre-RT) were acquired within 2 weeks of starting RT either during simulation (for RT treatment planning) or treatment set-up appointments immediately prior to beginning treatment. On-treatment visit (RT) collections were obtained one-half to two-thirds through each patient’s RT course. Post-treatment specimens (Post-RT) were collected within 3–6 weeks after the completion of RT at a follow-up appointment. A total of 30 patients were enrolled in the study, of which 23 had pre-RT sample analysis, 16 had RT sample analysis, and 8 had Post-RT sample analysis. The median follow-up time for Post-RT patients was 4 weeks.

All care providers and laboratory personnel involved with patient treatment and evaluation were blinded to CTC quantitative and qualitative analyses. Cancer-free control blood was obtained from healthy human volunteers under a separate IRB-approved protocol and was processed alongside clinical samples.

Approximately 10 mL of whole blood was drawn from each patient, which was then processed via centrifugation through a density gradient to enrich for CTCs while removing red blood cells. The CTC-enriched layer was then exposed to probe and incubated for 24 hours. The samples were subsequently imaged using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U, Tokyo, Japan) via a computer-driven image processing and cell counting system (Image Pro Plus 7.0, Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD). The computer software was set to filter and sort imaged cells by size and intensity, among other parameters, which together with manual visual confirmation ensured the counting of cells and exclusion of debris and other confounding objects. Samples were fixed by phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) rinse followed by either 1% formalin or 4% formaldehyde fixation (15 minute duration at room temperature), and an additional PBS rinse. Staining was done using mounting medium containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and anti-TTF1 antibodies (1:200 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). This enabled a second method to distinguish leukocytes (which are DAPI+/TTF1-) from NSCLC adenocarcinoma CTCs (DAPI+/TTF1+/GFP+). Additional immunofluorescence staining for leukocytes consisted of the following antibody: anti-CD45 at 1:200 (Biolegend, San Diego, CA).

NSCLC Cell Culture

Human NSCLC cell lines H1975 (adenocarcinoma), H1703 (squamous carcinoma), and A549 (squamous carcinoma) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). ATCC characterizes each cell line using cytochrome C oxidase I (COI) and short tandem repeat (STR) testing. H1975 and H1703 were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 1.0% penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. A549 was maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI-1640, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 1.0% penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Normal Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells

Normal Human Bronchial Epithelial (NHBE) cells were prepared, propagated, and handled as recommended by the source (Clonetics Primary Cells, Lonza Ltd, Basel, Switzerland). Briefly, NHBE cells were propagated in growth-factor supplemented BEGM Bronchial Epithelial Cell Growth Media, while differentiation was effected in B-ALI Bronchial Air Liquid Interface Media (all from Lonza). All other procedures utilized for NHBE cells were identical to that utilized for human cancer cells or patient samples, including exposure to Probe and image acquisition and analysis.

Western Blotting

Cell harvesting consisted of scraping, centrifugation, and lysis (ice, 2 hour duration). Lysate harvesting allowed for protein concentration determination via the BioRad protein assay (Hercules, CA). Sample electrophoresis, PVDF transfer, and non-specific binding block preceded membrane incubation in the following antibodies (with corresponding company at respective concentration and incubation condition): EpCAM at 1:1000 (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN), hTERT at 1:2000 (Millipore, Billerica, MA), TTF-1 at 1:1000 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) and Ran at 1:10,000 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Following membrane TBST rinse, HRP-conjugated secondary antibody incubation (5 minute duration) was performed with subsequent visualization.

Statistical Analysis

STATA 12 was used for statistical analysis (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Negative binomial regression was employed to model over-dispersed cell counts, adjusting variances for within-subject random effects using the cluster-correlated robust covariance estimate (alpha = 0.05).30 Treatment phase was entered as a categorical variable while Pre-RT count was treated as the reference category.

RESULTS

Preclinical and initial clinical validation of the assay

We tested NSCLC cells in culture as a first step towards establishing the effectiveness of the CTC assay for detecting malignant cells. Western blot analysis confirmed that all cancer cell lines tested, including those derived from NSCLC, expressed high levels of telomerase protein (Figure 1A). Interestingly, we found few of these cell lines, and none of the NSCLC-derived cell lines, expressed high levels of EpCAM (an epithelial cell surface marker that serves as the basis of alternative assays). Towards establishing the effectiveness of the assay for clinical-derived samples, we also tested the specificity of the NSCLC adenocarcinoma marker TTF-1. As expected, only the lung adenocarcinoma-derived H1975 cells expressed high levels of TTF-1 protein (Figure 1B). In contrast, TTF-1 protein was not expressed by A549 and H1703 cells, both derived from patients with squamous carcinoma of the lung, nor in the cell lines from other solid tumors of other histologies.

Next, we exposed NSCLC cells grown in culture to the probe. We found the probe was effective in all cell lines derived from NSCLC that we tested, including both squamous cell carcinomas (A549, H226) and adenocarcinomas (H1299, H1975). EGFR status did not adversely affect the performance of the probe, as H1975 adenocarcinoma cells which have mutant EGFR (L858R) and H1299 adenocarcinoma cells with wild-type EGFR were both readily identified by the probe (Figure 1C). As an additional control, we tested the probe on normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cells. In contrast to the bright signal elicited by the probe in all the lung cancer cells we tested, minimal signal was found in the NHBE cells, further illustrating the specificity of the probe for cancer and not normal cells (Supplemental Figure 1).

In additional preclinical studies, NSCLC cells were spiked into blood samples collected from healthy volunteers without cancer and the effectiveness of the probe was found not to be impeded (data not shown). These successes led to validation experiments in clinical NSCLC samples for confirming the specificity of the probe for detection of NSCLC CTC in patient samples. A representative clinical sample from a patient with NSCLC is shown in Figure 1D, which was processed and counterstained for CD45 (a leukocyte marker) to exclude the possibility of “false positive” detection of white blood cells (WBCs) by the probe. There was no appreciable overlap between immunofluorescent signals identifying tumor cells {GFP (green)} or WBCs {CD45 (red)} in nucleated cells that were identified by DAPI, confirming that the probe detected CTC but not the non-CTC nucleated WBCs. Finally, we also tested the probe’s ability to detect TTF-1-positive cells to confirm the adenocarcinoma origin of GFP-positive cells. As shown in a representative experiment (Fig. 1E), the GFP-positive cells identified from a patient with lung adenocarcinoma also co-expressed TTF-1, confirming the specificity of the probe. Taken together, these findings confirm that GFP expressing cells detected by the assay were indeed cancer cells whose origin was the primary lung adenocarcinoma.

Pilot study of CTC in patients undergoing Radiation Therapy for NSCLC

Following the extensive validation experiments described above, we conducted a pilot study to detect CTC in NSCLC patients receiving definitive RT in the Department of Radiation Oncology according to the schema described in Figure 2A. Patients were enrolled on study and had the CTC assay preformed at the following time points: prior to the initiation of Radiation Therapy (Pre-RT), during RT, and after completion of Radiation Therapy (Post-RT). Overview of the recruitment and CTC assessments are detailed in the flowchart described in Figure 2B. In total, 30 patients were recruited onto the CTC study.

The computer-driven image acquisition and analysis system employed for the assay enables the sorting of cells identified by the probe based on the size and fluorescence intensity. The results for each sample can be plotted on a scatter graph, with filters applied to distinguish true CTCs from debris and normal cells based on predetermined and validated size and fluorescent intensity criteria. Figure 2C shows scatter graphs of a representative healthy control blood sample (Control), as well as samples from three separate patients with NSCLC (Cases A, B, C). Changes in CTC-derived signal due to the effects of RT can be visualized on these graphs. For example, Figure 2D shows Pre-RT and Post-RT CTC counts in a representative patient, for whom CTC counts decreased with RT.

Of the 23 patients in whom samples were obtained prior to the initiation of RT, CTC were identified in 15 patients (65%). The mean and median CTC per mL of whole blood were 62.7 and 9.1, with a range from below threshold to 570.7 and standard deviation of 136.0 (Table 1). Samples obtained after the completion of RT showed that the CTC counts were below threshold in all but one patient. This exception was a patient who was found to have developed metastatic disease soon after completion of RT. His CTC counts correspondingly had increased from 198.5 during RT (RT) to 545 at follow-up (Post-RT). Figure 3 shows the distribution of all individual counts obtained with the sole exception of the patient who developed metastases.

Table 1.

| Pre-RT | RT | Post-RT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEAN | 62.7 | 9.4 | 0.6 |

| MEDIAN | 9.1 | 1.8 | 0.6 |

| RANGE | 0.57 – 570.7 | 0 – 74.7 | 0 – 1.8 |

| STDDEV | 136.0 | 19.3 | 0.6 |

| STD ERROR of the mean |

29.0 | 5.2 | 0.2 |

Negative binomial regression analysis was used to compare CTC counts obtained at the different points in treatment. Using the Pre-RT (“pre-treatment”) population as the reference group, the control counts (RR=0.012, CI 0.005–0.031, p<0.001) and the post-RT counts (RR=0.010, CI 0.004–0.029, p<0.001) had statistically significant lower CTC counts. Together, these analyses indicated that CTC counts obtained after completion of RT, and in healthy volunteers, were significantly lower than patients assessed prior to initiation of RT.

Sequential CTC analyses in individual patients/ Patient vignettes

Sequential CTC analyses, consisting of least two analyses obtained at either Pre-RT, during RT (RT), or Post-RT, were available for ten patients. The results of this subset of patients are shown in Table 2 (along with status of disease at the first follow-up visit after the completion of radiation treatment (Post-RT), patient and tumor characteristics, type of radiation therapy, and total RT dose). Three of these patients have sequential imaging that are illustrative and complement the CTC analyses, and are thus described in greater detail below.

Table 2.

| Pre-RT | RT | Post-RT | Status at Post-RT |

Age | M/F | Stage | Histology | Tumor Location |

Proton/ IMRT |

Radiation (cGy) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 56.9 | 0.4 | 0.9 | Controlled | 67 | F | IIIA (T2b N2 M0) | Adenosquamous | LLL | Proton | 5040 |

| 9.1 | 3.2 | 1.3 | Controlled | 51 | F | IIIA (T2a N2 M0) | Adenosquamous | LUL | Proton | 5040 |

| NA | 7.1 | 0 | Controlled | 71 | M | IIIA/B (TX N2/3 M0) | Poorly Differentiated NSCLC |

Mediastinal | Proton | 5040 |

| 3.2 | NA | 0.2 | Controlled | 70 | F | IIIB (T4 N2 M0) | Adenocarcinoma | RLL | Proton | 6660 |

| NA | 198.5 | 545.0 |

Distant Failure |

53 | M | IIIB (T3 N3 M0) | Squamous | RUL | IMRT | 6660 |

| 25 | 0 | Controlled | 53 | F | IIIA (T3 N2 M0) | Squamous | RUL | IMRT | 6660 | |

| 5.6 | NA | 0.6 | Controlled | 74 | M | IIIA (T3 N1 M0) | Typical Carcinoid | LUL | IMRT | 6660 |

| 1.1 | NA | 0.7 | Controlled | 62 | F | IIIA (T2b N2 M0) | Poorly Differentiated NSCLC |

RUL | Proton | 5040 |

| 2.6 | 0.2 | 0.3 | Controlled | 74 | M | IIIA (T1a N2 M0) | Adenocarcinoma | LLL | Proton | 5040 |

| 10.3 | 6.8 | NA | Controlled | 71 | M | IIIB (T3 N3 M0) | Squamous | LUL | Proton | 6660 |

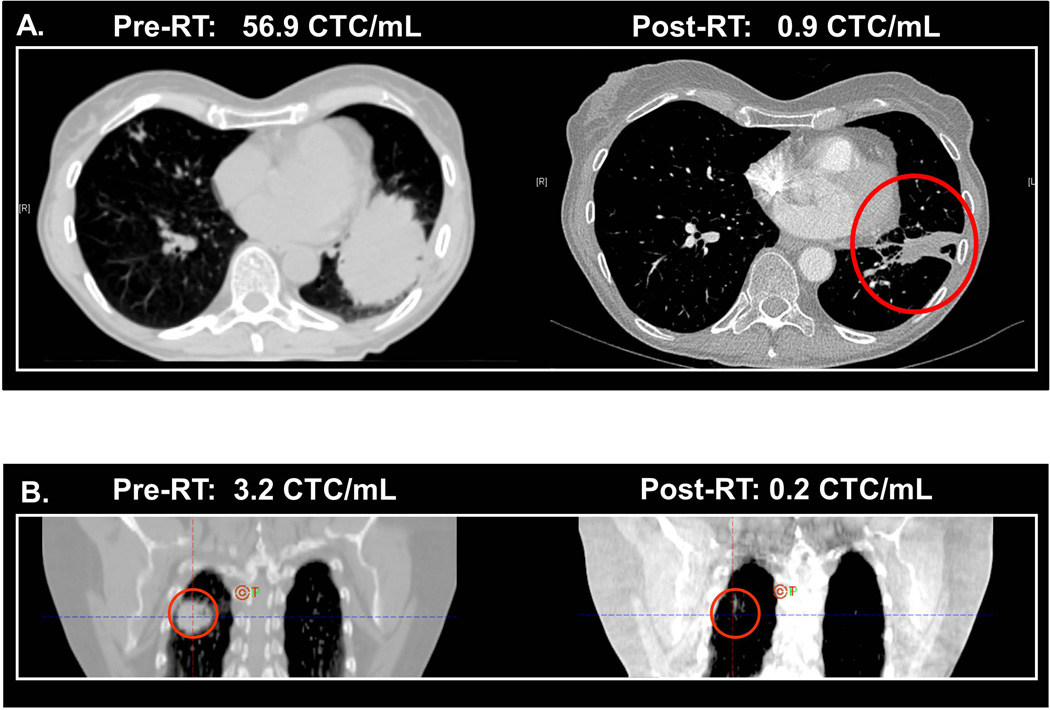

Case 1 is a 67 year old with a stage IIIA (T2bN2M0) lung adenosquamous carcinoma (T2b = tumor >5 cm but ≤7 cm in greatest dimension, N2 = metastasis in ipsilateral mediastinal or subcarinal lymph node, M0 = no distant metastases).31 On pre-treatment CT scan, the patient was found to have a significant tumor burden in the left lower lobe (Figure 4A) with an accompanying CTC count of 56.9 CTC/mL. After pre-operative chemo-RT and subsequent resection of the primary tumor and associated lymph nodes, the CT scan demonstrated a dramatic response with residual scarring. Post-RT, the CTC count had also decreased to 0.9 CTC/mL.

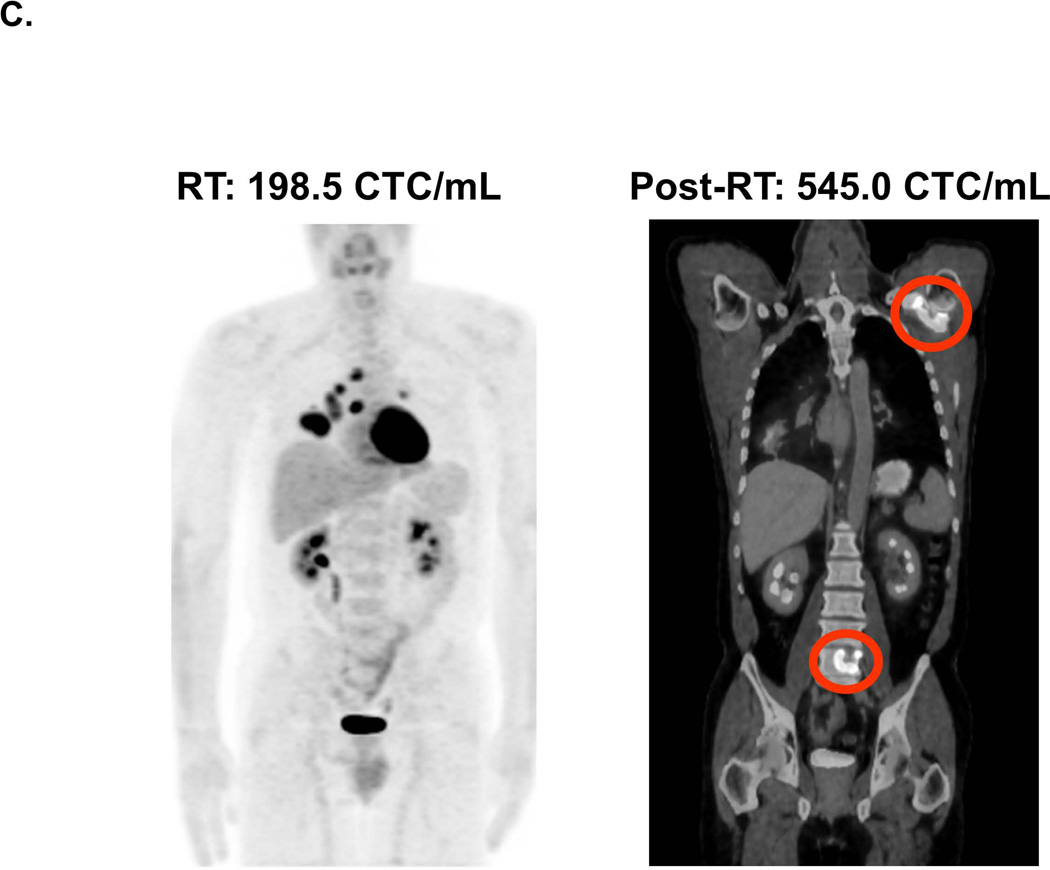

Figure 4. Correlation of Radiographic Imaging of Tumor Status and CTC Analysis Results.

For each patient, the respective CTC count is indicated at each time period and correlated with the radiographic imaging. A. CT imaging of a patient with stage IIIA adenosquamous carcinoma of the left lower lobe before and after RT. B. CT imaging of a patient with stage IIIB adenocarcinoma of the right lower lobe before and after RT. C. PET imaging of a patient with stage IIIB lung squamous carcinoma taken at the initial treatment facility during the RT course (“RT”), and a second PET scan taken at an outside facility after the patient developed new shoulder and low back pain. The latter PET scan indicated the progression of disease to new metastases to the shoulder and lumbar spine (therefore accounting for the patient’s symptoms).

Case 2 is a 70 year old with a stage IIIB lung adenocarcinoma of the right lower lobe. On pre-treatment CT scan, the patient had a 3 cm lung tumor and mediastinal nodal metastasis (Figure 4B) and had a Pre-RT CTC count of 3.2 CTCs/mL. After chemo-RT, the CT scan demonstrated significant tumor response with only residual scarring. The Post-RT CTC count had also decreased to below detectable levels at 0.2 CTC/mL.

Case 3 is a 53 year old with a stage IIIB lung squamous carcinoma who was treated with chemo-RT (IMRT to 6660 cGy). Of note, this patient’s tumor harbored an EGFR mutation in exon 19. The patient’s PET scan prior to treatment demonstrated only localized disease. The patient’s first clinical sample was obtained after the initiation of RT (because Pre-RT counts were not available, the patient’s data is not included in whisker plots depicting overall clinical prospective results (Figure 3). At 4320 cGy (24 of 37 fractions received), the patient was found to have an RT CTC count of 198.5 CTC/mL, which when reassessed two weeks following the completion of RT had increased to 545.0 CTC/mL. On routine follow up CT scan at 4 weeks after RT, she was found to have an ill-defined lytic lesion was detected in T10. At that time, the patient also noted left shoulder pain. A PET-CT scan was performed and demonstrated avid radiotracer uptake within the left scapula and T10 and lumbar (L5) vertebral bodies and sacrum, consistent with progressive metastatic disease (Figure 4C).

DISCUSSION

Herein we describe the novel application of a CTC assay that is effective for NSCLC cells in culture and in patients, effective in various subtypes and unaffected by EGFR mutation status. The CTC assay further appears to track the response of patients undergoing RT for their tumors. Our validation experiments reinforce the biological underpinnings for this telomerase-based assay. Increased levels of the human telomerase protein (hTERT) were found in all cancer cell lines tested, consistent with literature citing increased telomerase activity in almost all human cancers (Figure 1).21,32,33 Interestingly, an early effort also detected telomerase activity in the epithelial cell fraction harvested from the blood of patients with NSCLC, but not in healthy controls (even though limited in the ability to count or establish the tumor origin of the epithelial cells).34 In contrast to the consistently high levels of telomerase in all cancer cell lines we have tested, EpCAM was highly expressed in few. Among lung cancer cell lines, only H1975 expressed detectable levels of the EpCAM protein. The lack of EpCAM in many NSCLC cells may affect the widespread applicability of EpCAM-based CTC detection techniques for patients with NSCLC.

The assay detects NSCLC cells irrespective of histological subtype or EGFR mutation status. When the probe is applied to various NSCLC cell lines, each GFP+ signal corresponds to a DAPI+ cell. The sensitivity of the probe for NSCLC cell lines was calculated to be 95 ± 5%. Specificity studies were previously performed by incubating the probe with healthy control blood, finding a high specificity of 99.5%.28 Thus, the telomerase-based assay has high sensitivity and specificity for NSCLC CTC and was thus implemented in a pilot trial in patients with NSCLC undergoing RT.

This pilot study to identify CTC in NSCLC patients undergoing RT illustrates key aspects of NSCLC CTC detection using this assay. First, in NSCLC adenocarcinoma patients, we confirm the lung adenocarcinoma origin of these CTCs by counter-staining clinical samples with anti-TTF-1 antibodies. Though GFP+ cells are rare, these cells co-stain for antibodies against adenocarcinoma-specific proteins and are shown to be surrounded by a background of white blood cells, which in contrast are negative for GFP and TTF-1 (Figure 1E). Second, healthy control samples assayed in the same manner as cancer patient samples served as negative controls to establish a threshold count. A logistic regression model applied to healthy control samples identified a threshold count of 1.3 GFP+ cells/mL, above which CTC levels are taken to represent true signal above the background noise. Third, Post-RT CTC counts demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in comparison to Pre-RT levels. A negative binomial regression was applied to the pilot trial data using Pre-RT as the reference value. Control blood and Post-RT CTC levels were found to be statistically decreased (p<0.001 for both). Whether this decrease in CTC levels is a product of the cohort’s overall positive response to chemo-RT/RT or the effect of RT alone irrespective of treatment response is yet to be determined.

The three patient vignettes described highlight the potential for serial CTC levels to reflect tumor response to RT. CTC levels in Cases 1 and 2 decreased from Pre-RT to undetectable levels at Post-RT, and these decreases correlated with radiographic evidence of tumor response. Though the Post-RT CT scans for both patients show residual lung tissue thickening, the accurate eventual diagnosis of post-radiation scarring over residual disease was bolstered by the accompanying low CTC counts. In contrast, Case 3 was found to have new metastatic disease shortly after completing RT and had a corresponding rise in the CTC levels at Post-RT.

The patient described in Case 3 was also found to be a candidate for EGFR inhibitor targeted therapy but eventually developed resistance to this treatment. Highly variable response to EGFR inhibition has been previously observed, suggesting tumor heterogeneity within tumors of a given gene mutation status. For example, studies conducted on metastatic NSCLC patients revealed discordant mutational status of primary tumors with their respective metastases.35 Such considerations suggest the potential usefulness of CTC assays to help tailor optimal treatment regimens. CTC analysis may help serve as “real time liquid biopsies” of the constantly evolving tumor, potentially offering a method of monitoring of tumor evolution long after the initial primary tissue surgery or biopsy has taken place. Individual CTCs may potentially be characterized before, during, and after targeted therapy to identify populations that retain or lose their original EGFR mutation and thus responsiveness to targeted therapy.

The major limitation in this study is sample size. The pilot NSCLC CTC study strongly suggests CTC levels decreased over the course of RT but was not powered to detect these changes. The relatively small sample size also prohibited subset analyses, including for patients in which CTCs were not detected prior to the start of RT. Nonetheless, this subset of patients did not share an obvious factor potentially contributing to the lack of detection by the Assay (Supplemental Table 1).

Given the limited size of this pilot trial, the statistical analyses in this paper aggregates CTC counts for pre and post-RT, but a more accurate analysis may be achieved with pair-wise comparisons for each individual’s pre and post-RT CTC level. This was not always possible, as not every patient provided each of these samples. Though the constraints of this study did not permit extensive follow-up of individual patients, prospective longitudinal studies are currently underway to evaluate the significance of CTC trends in individual patients.

CONCLUSIONS

We describe promising results with the novel application of an assay that detects CTCs based on elevated telomerase specific to cancer cells in a pilot study of patients undergoing RT for localized NSCLC. We further found that in this small cohort of patients, CTC counts appear to reflect the clinical course and response to treatment. These preliminary results seem promising for ultimately contributing to patient care, such as by complementing standard radiographic imaging. How best to integrate CTC assays into standard clinical practice will, however, require further study, such as in a larger cohort of patients with NSCLC treated with a variety of modalities and having varied responses to treatment. We are currently conducting a larger clinical trial in NSCLC patients to expand on the promising results reported here.

Supplementary Material

Normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cells or non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell line H1975 were prepared as described for the experiment in Figure 1, including exposure to Probe, incubation, and imaging for subsequent fluorescence. After exposure to Probe, the NSCLC cells expressed strong green fluorescent protein (GFP), while in contrast NHBE cells expressed minimal to no fluorescence.

Details regarding age, sex, histology of the NSCLC, stage of cancer, and whether or not concurrent chemotherapy was employed was available for five of the patients in which CTC were not detected prior to the initiation of radiation therapy. None of these factors appeared to unambiguously contribute to the lack of CTC detected.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to acknowledge Yasunari Kashihara and Yasuo Urata of Oncolys Biopharma, Inc. for graciously supplying the Telomescan reagent. We would like to thank Drs. Hirotoshi Hoshiyama and Toshiyoshi Fujiwara for helpful discussions. We acknowledge Drs. Xiangsheng Xu and Wensheng Yang for technical assistance. We would also like to thank the University of Pennsylvania Department of Radiation Oncology (DRO) clinical research coordinators for their assistance with the clinical protocols reported here.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health: NCI (RC1 CA145075) and NINDS (K08 NS076548-01). J.F.D. was supported on a Burroughs Wellcome Career Award for Medical Scientists (1006792). K.M.M. was supported on the Radiation Biology Training Grant C5T32CA009677 (PI: Dr. Ann Kennedy). Financial support for the Assay development was provided by the University of Pennsylvania Department of Radiation Oncology.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors’ institution (University of Pennsylvania) has submitted a patent application based on a component of the technology presented in this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society. [Accessed January/08, 2014];What are the key statistics about lung cancer? http://www.cancer.org/cancer/lungcancer-non-smallcell/detailedguide/non-small-cell-lung-cancer-key-statistics. Updated 2013.

- 2.Hanley M, Welsh C. Current diagnosis and treatment in pulmonary medicine. New York City, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takeda A, Kunieda E, Takeda T, et al. Possible misinterpretation of demarcated solid patterns of radiation fibrosis on CT scans as tumor recurrence in patients receiving hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70(4):1057–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.07.2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang K, Dahele M, Senan S, et al. Radiographic changes after lung stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR)--can we distinguish recurrence from fibrosis? A systematic review of the literature. Radiother Oncol. 2012;102(3):335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahele M, Palma D, Lagerwaard F, Slotman B, Senan S. Radiological changes after stereotactic radiotherapy for stage I lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6(7):1221–1228. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318219aac5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Elmpt W, Pottgen C, De Ruysscher D. Therapy response assessment in radiotherapy of lung cancer. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;55(6):648–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devriese LA, Bosma AJ, van de Heuvel MM, Heemsbergen W, Voest EE, Schellens JH. Circulating tumor cell detection in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients by multi-marker QPCR analysis. Lung Cancer. 2012;75(2):242–247. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allard WJ, Matera J, Miller MC, et al. Tumor cells circulate in the peripheral blood of all major carcinomas but not in healthy subjects or patients with nonmalignant diseases. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(20):6897–6904. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krebs MG, Sloane R, Priest L, et al. Evaluation and prognostic significance of circulating tumor cells in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(12):1556–1563. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.7045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hofman V, Bonnetaud C, Ilie MI, et al. Preoperative circulating tumor cell detection using the isolation by size of epithelial tumor cell method for patients with lung cancer is a new prognostic biomarker. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(4):827–835. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nieva J, Wendel M, Luttgen MS, et al. High-definition imaging of circulating tumor cells and associated cellular events in non-small cell lung cancer patients: A longitudinal analysis. Phys Biol. 2012;9(1) doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/9/1/016004. 016004-3975/9/1/016004. Epub 2012 Feb 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ge M, Shi D, Wu Q, Wang M, Li L. Fluctuation of circulating tumor cells in patients with lung cancer by real-time fluorescent quantitative-PCR approach before and after radiotherapy. J Cancer Res Ther. 2005;1(4):221–226. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.19591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du YJ, Li J, Zhu WF, et al. Survivin mRNA-circulating tumor cells predict treatment efficacy of chemotherapy and survival for advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Tumour Biol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1592-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim E, Tay A, Von Der Thusen J, Freidin MB, Anikin V, Nicholson AG. Clinical results of microfluidic antibody-independent peripheral blood circulating tumor cell capture for the diagnosis of lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lou J, Ben S, Yang G, et al. Quantification of rare circulating tumor cells in non-small cell lung cancer by ligand-targeted PCR. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e80458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang J, Wang K, Xu J, Huang J, Zhang T. Prognostic significance of circulating tumor cells in non-small-cell lung cancer patients: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e78070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang J, Wang K, Xu J, Huang J, Zhang T. Correction: Prognostic significance of circulating tumor cells in non-small-cell lung cancer patients: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078070. 10.1371/annotation/6633ed7f-a10c-4f6d-9d1d-9c1245822eb7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagrath S, Sequist LV, Maheswaran S, et al. Isolation of rare circulating tumour cells in cancer patients by microchip technology. Nature. 2007;450(7173):1235–1239. doi: 10.1038/nature06385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rolle A, Gunzel R, Pachmann U, Willen B, Hoffken K, Pachmann K. Increase in number of circulating disseminated epithelial cells after surgery for non-small cell lung cancer monitored by MAINTRAC(R) is a predictor for relapse: A preliminary report. World J Surg Oncol. 2005;3(1):18. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu C, Hao H, Li L, et al. Preliminary investigation of the clinical significance of detecting circulating tumor cells enriched from lung cancer patients. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4(1):30–36. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181914125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim Y, Kim HS, Cui ZY, et al. Clinicopathological implications of EpCAM expression in adenocarcinoma of the lung. Anticancer Res. 2009;29(5):1817–1822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Qian X, Beitler JJ, et al. Detection of circulating tumor cells in human peripheral blood using surface-enhanced raman scattering nanoparticles. Cancer Res. 2011;71(5):1526–1532. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Z, Li Q, Li K, et al. Telomerase reverse transcriptase promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and stem cell-like traits in cancer cells. Oncogene. 2013;32(36):4203–4213. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim SJ, Masago A, Tamaki Y, et al. A novel approach using telomerase-specific replication-selective adenovirus for detection of circulating tumor cells in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;128(3):765–773. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1603-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kojima T, Hashimoto Y, Watanabe Y, et al. A simple biological imaging system for detecting viable human circulating tumor cells. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(10):3172–3181. doi: 10.1172/JCI38609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maida Y, Kyo S, Sakaguchi J, et al. Diagnostic potential and limitation of imaging cancer cells in cytological samples using telomerase-specific replicative adenovirus. Int J Oncol. 2009;34(6):1549–1556. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macarthur KM, Kao GD, Chandrasekaran S, et al. Detection of brain tumor cells in the peripheral blood by a telomerase promoter-based assay. Cancer Res. 2014;74(8):2152–2159. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ju M, Kao GD, Steinmetz D, et al. Application of a telomerase-based circulating tumor cell (CTC) assay in bladder cancer patients receiving postoperative radiation therapy: A case study. Cancer Biol Ther. 2014;15(6) doi: 10.4161/cbt.28412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams RL. A note on robust variance estimation for cluster-correlated data. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):645–646. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edge S, Byrd D, Compton C, Fritz A, Greene F, Trotti A. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim NW, Piatyszek MA, Prowse KR, et al. Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer. Science. 1994;266(5193):2011–2015. doi: 10.1126/science.7605428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shay JW, Bacchetti S. A survey of telomerase activity in human cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33(5):787–791. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(97)00062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gauthier LR, Granotier C, Soria JC, et al. Detection of circulating carcinoma cells by telomerase activity. Br J Cancer. 2001;84(5):631–635. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han HS, Eom DW, Kim JH, et al. EGFR mutation status in primary lung adenocarcinomas and corresponding metastatic lesions: Discordance in pleural metastases. Clin Lung Cancer. 2011;12(6):380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cells or non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell line H1975 were prepared as described for the experiment in Figure 1, including exposure to Probe, incubation, and imaging for subsequent fluorescence. After exposure to Probe, the NSCLC cells expressed strong green fluorescent protein (GFP), while in contrast NHBE cells expressed minimal to no fluorescence.

Details regarding age, sex, histology of the NSCLC, stage of cancer, and whether or not concurrent chemotherapy was employed was available for five of the patients in which CTC were not detected prior to the initiation of radiation therapy. None of these factors appeared to unambiguously contribute to the lack of CTC detected.