Abstract

The high risk of insertional oncogenesis reported in clinical trials utilizing integrating retroviral vectors to genetically-modify hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPC) requires the development of safety strategies to minimize risks associated with novel cell and gene therapies. The ability to ablate genetically modified cells in vivo is desirable, should an abnormal clone emerge. Inclusion of “suicide genes” in vectors to facilitate targeted ablation of vector-containing abnormal clones in vivo is one potential safety approach. We tested whether the inclusion of the “inducible Caspase-9” (iCasp9) suicide gene in a gamma-retroviral vector facilitated efficient elimination of vector-containing HSPCs and their hematopoietic progeny in vivo long-term, in an autologous non-human primate transplantation model. Following stable engraftment of iCasp9 expressing hematopoietic cells in rhesus macaques, administration of AP1903, a chemical inducer of dimerization able to activate iCasp9, specifically eliminated vector-containing cells in all hematopoietic lineages long-term, suggesting activity at the HSPC level. Between 75–94% of vector-containing cells were eliminated by well-tolerated AP1903 dosing, but lack of complete ablation was linked to lower iCasp9 expression in residual cells. Further investigation of resistance mechanisms demonstrated upregulation of Bcl-2 in hematopoietic cell lines transduced with the vector and resistant to AP1903 ablation. These results demonstrate both the potential and the limitations of safety approaches utilizing iCasp9 to HSPC-targeted gene therapy settings, in a model with great relevance to clinical development.

Keywords: iCasp9, HSC transplantation, genotoxicity, suicide gene, gene therapy

Introduction

Given the demonstrable significant clinical benefits achieved via genetic correction of HSPCs and the real potential for cure of several very serious monogenic blood, immunologic, metabolic, and neurodegenerative diseases, there is a strong impetus to mitigate genotoxic risks while further developing gene therapy approaches utilizing integrating vectors (1–5). There are several ways to reduce genotoxic risks linked to the presence of strong viral enhancers within standard gamma-retroviral vectors. Self-inactivating (SIN) gamma-retroviral vectors with deletion of LTR enhancers and inclusion of internal tissue-specific or constitutive cellular promoters less likely to activate adjacent genes are in active development or in early clinical trials. Lentiviral vectors derived from HIV are less likely to activate genes by integrating near transcription start sites, and can be constructed without enhancers and with tissue-specific or constitutive cellular promoters, such as phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) or elongation factor-1 alpha (EF-1a). Both strategies resulted in a much lower risk of genotoxicity in leukemia-prone mouse models or hematopoietic cell immortalization assays (6–8). However, even putatively safer lentiviral vectors have been linked to clonal expansion due to interference with normal gene expression in a clinical trial for β-thalassemia, with new evidence suggesting that this vector class is prone to interfere with mRNA splicing (9, 10).

The concept of incorporating a “suicide gene” within integrating vectors to allow ablation of transduced cells should transformation or other adverse side effects occur has been explored for almost two decades (11). A suicide gene encodes a protein that selectively converts a non-toxic drug into highly toxic metabolites or a protein that can be activated to be toxic within a cell by a drug, specifically eliminating vector-containing cells expressing the suicide gene. The most commonly used suicide system in clinical and experimental settings has been the combination of the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-tk) gene and the drug ganciclovir (GCV). Landmark clinical trials demonstrated its efficacy in the abrogation of graft versus host disease (GvHD) caused by allogeneic donor T cells genetically modified with the HSV-tk gene (11–13). We recently reported the feasibility and efficacy of GCV-mediated elimination of transduced HSPCs and their progeny, utilizing the rhesus macaque model. Complete and durable elimination of cells transduced with a vector containing a highly sensitive HSVTtkSR39 mutant enzyme was achieved with a single cycle of GCV administration (14).

In spite of these encouraging results, the HSV-tk/GCV suicide system has a number of important limitations that need to be considered before wider clinical application. As a viral protein, the HSVtk enzyme is immunogenic, and can result in rejection of transduced cells, even without GCV administration (15). In addition, mutations within the HSV-tk gene resulting from alternative splicing sites within the cDNA or point mutations decreasing HSV-tk activity and GCV resistance have been reported (16). Moreover, because GCV and the related antiviral acyclovir are commonly used to treat infections caused by large DNA viruses, including cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex and herpes zoster, the presence of HSV-tk within gene-corrected cells would either result in an inability to treat patients with these effective antiviral drugs, or undesirable ablation of functioning and non-transformed gene-corrected cells due to the need to give GCV treatment for a serious viral infection.

Therefore, alternative suicide gene systems have recently been developed. One of the most promising consists of a transgene encoding an inducible pro-apoptotic protein that is activated by a small molecule chemical inducer of dimerization (CID)(17). The human Caspase-9 apoptosis gene is modified by the addition of sequences encoding the CID-binding dimerizing domain from human FK506-binding protein 12, in a construct termed “inducible Caspase-9” (iCasp9) which is activated in the presence of low nanomolar concentrations of the bioinert and non-toxic compound, AP1903, resulting in selective dimerization of iCasp9 within cells expressing the transgene, leading to rapid apoptosis (18, 19). There are few potential immunogenic components in this engineered gene product, since the iCasp9 protein is derived from the endogenous human Caspase-9 and FK506-BP genes, and the AP1903 dimerizer is a small, non-peptidic molecule. AP1903 is not currently used therapeutically for any other indication; therefore, there is no possibility of inadvertent ablation of transduced cells, in contrast to GCV.

In a recent clinical trial, five patients received haplo-identical donor T cells transduced with the iCasp9 gene as anti-leukemia immunotherapy in the context of stem cell transplantation. After development of GvHD in four patients, the administration of just a single dose of AP1903 rapidly eliminated 80–90% of the donor T cells, including virtually all activated gene-modified cells, and effectively abrogated the clinical and laboratory manifestations of GvHD(20). This suicide system has also been investigated in vitro and in murine models to ablate transduced pluripotent or mesenchymal stem cells, but has not been previously investigated for efficacy in the hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell gene therapy model, the target cell most susceptible to genotoxicity and thus very relevant for suicide gene safety approaches (21, 22).

In this study, we tested the effectiveness of the iCasp9/AP1903 system for controlled ablation of vector-containing HSPCs and their progeny in vivo in the rhesus macaque model. Our results show that iCasp9 expression in HSPCs is safe, and enables long-term hematopoietic engraftment with transduced cells following autologous HSPC transplantation, with efficient but incomplete selective elimination of high-expressing transduced cells following AP1903 administration.

Methods

Study design

The in vivo transplantation of rhesus macaques was designed as a pilot toxicity, feasibility and efficacy study, testing the hypothesis that the iCasp9/AP1903 suicide gene system would allow effective ablation of hematopoietic cells in vivo. Three consecutive macaques were transplanted with iCasp9-transduced cells. No animals receiving iCasp9-transduced cells were excluded, and all samples collected from these animals at prospectively-defined time points were included in the analyses. The number of replicates of in vitro cellular assays are given in figure legends and descriptions.

Gene transfer vectors

The SFG-iCasp9-ΔCD19 gamma-retrovirus vector used for our studies has been previously described (23). The construct consists of a human Caspase-9 (iCasp9)-human FK506 binding protein fusion gene, which encodes an inducible Caspase-9 (iCasp9) activated by dimerization of the FK506 domain (17). This suicide gene is linked via a cleavable 2A-like sequence to a truncated human CD19 (ΔCD19) marker gene. In some experiments a control vector without a suicide gene (MND-MFG-GFP) was utilized (24).

Collection and transduction of human and rhesus CD34+ cells

Human G-CSF mobilized peripheral blood stem cells were obtained from normal volunteers entered on an IRB-approved clinical protocol (96-H-0049, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute), and CD34+ cells were enriched via immune-absorption using the Isolex 300i CD34 selection device (Nexell Therapeutics, Irvine, CA). Juvenile rhesus macaques weighing 3–5 kg were handled in accordance with the Institute of Laboratory Animal Research guidelines, in protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Peripheral blood mobilization with G-CSF and stem cell factor (SCF), and CD34 immunoselection were performed as described (25). A 24-hour pre-stimulation of human or rhesus CD34+ cells at a density of 2.5–5 × 105/mL in the presence of rhuSCF (100 ng/ml), rhuTPO (100 ng/ml), and rhuFlt-3L (100 ng/ml) (all from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) on CH296 fibronectin-coated T162 flasks (RetroNectin, Takara, Bio, Otsu, Japan) was performed. Prestimulated human or rhesus CD34+ cells were then exposed to filtered vector-containing supernatants, freshly collected from producer cell lines in the presence of 4 μg/ml protamine sulfate. Fresh vector was added to cultures at 24, 48, and 72 hours, and after 96 hours total culture, the transduced CD34+ cells were collected, washed, and resuspended for in vitro studies or autologous transplantation (26, 27).

In vitro sensitivity of iCasp9-CD19+ cells

iCasp9-ΔCD19-transduced rhesus or human CD34+ cells were sorted for CD19 expression after staining with a phycoerythrin (PE)-CD19 (4G7) monoclonal antibody (BD Pharmigen catalog # 349209; San Diego, CA). iCasp9-ΔCD19+ cells and non-transduced control CD34+ cells were plated at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells/ml in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS (Hyclone; Logan, UT), 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and recombinant human (rhu) SCF (100 ng/ml), TPO (100 ng/ml), and rhuFlt-3L (100 ng/ml). Following twenty-four hours of culture, 10–50 nM of AP1903 (AP1903: 5 mg/mL, Bellicum Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Houston, TX) was added to the wells, and the cultures were continued for 24–48 hours. Cells were harvested and stained with Annexin-V phycoerythrin (PE) and 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) (BD Pharmigen) to assess cell death and apoptosis via flow cytometry. In experiments using hematopoietic cell lines, data were normalized using the formula: percentage of killing induced by AP1903 = 100% −(% viability in cells treated with AP1903 ÷ % viability of nontreated cells).

Colony forming units (CFU) progenitor plating efficiency and differentiation capacity was evaluated in iCasp9-ΔCD19-transduced and non-transduced CD34+ cells by culturing sorted cells in 10 nM AP1903 and cytokines for 24 hours, then plating in methylcellulose medium (MethoCult H4034: Stem Cell Technologies; Vancouver, BC) at a concentration of 103 cells/dish (dishes in triplicates). Dishes were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 15 days. Colonies with more than 50 cells were scored as positive, and lineage characteristics scored via standard morphologic criteria.

Rhesus autologous transplantation and in vivo AP1903 treatment

Each animal received 500-cGy doses of total body irradiation 48 and 24 hours preceding infusion of transduced autologous CD34+ cells, as described (25). Autologous CD34+ cells were collected from transduction plates, resuspended in autologous serum, and infused intravenously. At different time points following engraftment, peripheral blood samples and bone marrow specimens obtained by aspiration from the posterior iliac crest or ischial tuberosities were collected for analysis. Once stable engraftment was achieved 6–10 months following transplantation, AP1903 was administered intravenously over two hours at doses ranging from 0.4 mg/kg to 4 mg/kg per administration. Complete blood counts as well as blood chemistries were monitored at least weekly throughout the AP1903 treatment cycles. Physicals and follow-up CBCs were performed at least every 3 months to monitor for early signs of hematological malignancy. All animals were alive and in good health at the moment of writing this report, with follow-up of 37–39 months post-transplantation.

PCR (q-RTPCR) for SFG gammaretroviral vector sequences and iCasp9 coding sequences

Copy number of universal retrovirus sequences was measured via quantitative PCR utilizing a forward primer 5′-cgc aac cct ggg aga cgt cc-3′, reverse primer 5′-cgt ctc cta cca gaa cca cat atc c -3′ and probe/56-FAM/ccg ttt ttg tgg ccc gac ctg -3′ (IDT, Coralville, IA) on DNA extracted from the blood cells using the DNeasy Blood Mini kit (Qiagen; Huntsville, AL)(28). In each reaction 150 ng genomic DNA was assessed for vector copy number. A standard curve ranging from 107 to 10 copies was generated using 10-fold serial dilutions of plasmid DNA suspended in normal control macaque genomic DNA. Reactions were performed using Applied Biosystems 7500 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, CA) with TaqMan® Universal PCR Master Mix 2.0 (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, CA). The amplification conditions were 2 min at 50°C and 10 min at 95°, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 1 min. Data were analyzed with SDS v1.4 software (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, CA) using the following parameters: average over cycle range, manual threshold above the non-template control or the normal DNA control; and, for baseline and threshold determinations, a cycle range between 3 to 15 cycles. We established the acceptance criteria of the calibrator curve as follows: slope (−3.56 to −3.68), Y-intercept (38.86 to 41.26), and R^2 values (0.9994 to 0.9997).

For mutation screening of iCasp9 sequences, the following primers were utilized: P-2753: 5′TTCGCTTCTCGCTTCTGTTC; P-3083: 5′TTATGCCTATGGTGCCACTG; P-3371: 5′CTCCTCGCTGCATTTCATGG; P-3946: 5′GGGTCGCTAATGCTGTTTCG; P-4360: 5′CTGCTGACGACATCATGTAAC; P-4195: 5″CGCCCAGAGAAAGAGCAGAC; P-3809: 5′CGTCACTGGGTGTGGGCAAAC

Assessment of pro-and anti-apoptotic protein levels

Transduced human Karpas 299 cells (ATCC) were sorted for ΔCD19 and exposed to 10 nM AP1903 in vitro. Fifty million cells were resuspended in RIPA lysis buffer (Pierce) containing protease inhibitors (Pierce) and incubated on ice for 10 minutes, then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 minutes. Supernatants were harvested, mixed 1:2 with Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), boiled, and 50 μg or 100 μg protein loaded on a precast 10 – 20% SDS-polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad). After transfer to nitrocellulose membranes (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), membranes were probed with a mouse anti-human antibody against full-length caspase 9 (47 kDa) and a rabbit antibody against cleaved human caspase-9 (37 kDa), cleaved caspase-3 (17/19 kDa), Bcl-2 (28 kDa), or XIAP (53 kDa) at concentrations suggested by the manufacturer (all from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). Membranes were then exposed to peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and protein expression was quantitated by chemiluminescence detection (LumiGLO®, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). Blots were stripped and reprobed with rabbit anti-beta-actin (45 kDa) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) to confirm equal loading. The western blot band densities were analyzed by ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/). The relative intensity of the bands of a protein of interest were measured and normalized to the control actin band intensities.

Statistical analyses

Two-sided student’s t tests were utilized for all binary comparisons. Two-way ANOVA was used for testing significance when three groups were compared

Results

iCasp9/AP1903-induced apoptosis of human and rhesus HSPCs in vitro

In order to confirm the ability to successfully transduce HSPCs with iCasp9 and ablate them in vitro after exposure to AP1903, we transduced human (Hu) and rhesus (Rh) CD34+ cells with the gammaretroviral vector SFG-iCasp9-2A-ΔCD19, and sorted them for expression of the marker ΔCD19. The sorted cells were cultured with 10 or 50 nM AP1903 for 24 to 48 hours, concentrations that have resulted in maximal killing of transduced human T cells (20). The percentage of apoptotic (Ann-V+ 7-AAD+) iCasp-9/ΔCD19+ HuCD34+ cells increased from 17.05 ± 5.3 % without AP1903 to 91.75 ± 1.6 % with 10 nM P1903, and 92.27 ± 1.4 % with 50 nM AP1903 (Fig. 1A, B). A similar apoptotic response to AP1903 was observed in RhCD34+ iCasp-9/ΔCD19+ transduced cells, although RhCD34+ cells had a higher background level of apoptosis (Fig. 1C, D) likely due to increased sensitivity to in vitro culture conditions or less robust viability following thawing from cryopreservation. In contrast, there was no change in the degree of apoptosis when untransduced or control (no iCasp9 gene) gamma-retroviral vector-transduced rhesus or human CD34+ cells were exposed to AP1903 at the same concentrations, excluding off-target effects of AP1903 or spontaneous dimerization of iCasp9 in the absence of AP1903 (Fig. 1A,C).

Fig. 1. Effect of AP1903 on human or rhesus CD34+ cells transduced with the iCasp suicide vector.

A. Summary of % cell death of human CD34+ cells as determined by staining for Annexin V and 7ADD (% death includes both 7ADD + and Ann-V+ cells). Human CD34+ cells transduced with the SFG-iCasp9-2A-ΔCD19 vector (black) and sorted for ΔCD19 expression, are compared with CD34+ cells that were not transduced (white), or CD34+ cells transduced with a control MND-MFG-GFP vector (no iCasp9 gene) (grey). Cells were exposed overnight to AP1903 before analysis. Values shown are mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA was used for analyses of significance. The p values of 10 nM and 50 nM AP1903 % cell death for SFG-iCasp9-2A-ΔCD19-transduced cells compared to either the untransduced or control vector-transduced cells were all **** < 0.0001; n= 4. There was no significant impact of AP1903 on cell death of untransduced or control vector-transduced CD34+ cells, comparing 0 to 10 or 50 nM AP1903. B. Representative dot plot panel showing flow cytometric analysis of human CD34+ cells transduced with the SFG-iCasp9-2A-ΔCD19 vector and then exposed to AP1903 overnight, and stained for Annexin-V and 7AAD apoptotic markers. C. % cell death (mean ± SEM) for rhesus CD34+ cells transduced with SFG-iCasp9-2A-ΔCD19 and exposed to AP1903, compared to untransduced rhesus CD34+ cells. % cell death was significantly increased between untransduced and transduced cells exposed to 10 nM (***p= 0.001) and 50 nM (***p= 0.001), respectively, and between transduced untreated and transduced treated with 10 nM and 50 nM AP1903 (****p= 0.0001; n=2). There was no significant difference in cell death between untransduced cells incubated with 0 versus 10 nM or 50 nM AP1903, nor between untransduced untreated and transduced untreated rhesus CD34+ cells (2-way ANOVA). D. Representative panel showing flow cytometric analysis of animal A7X028 CD34+ cells transduced with the SFG-iCasp9-2A-ΔCD19 vector and then exposed to AP1903 overnight, and stained for Annexin-V and 7AAD apoptotic markers.

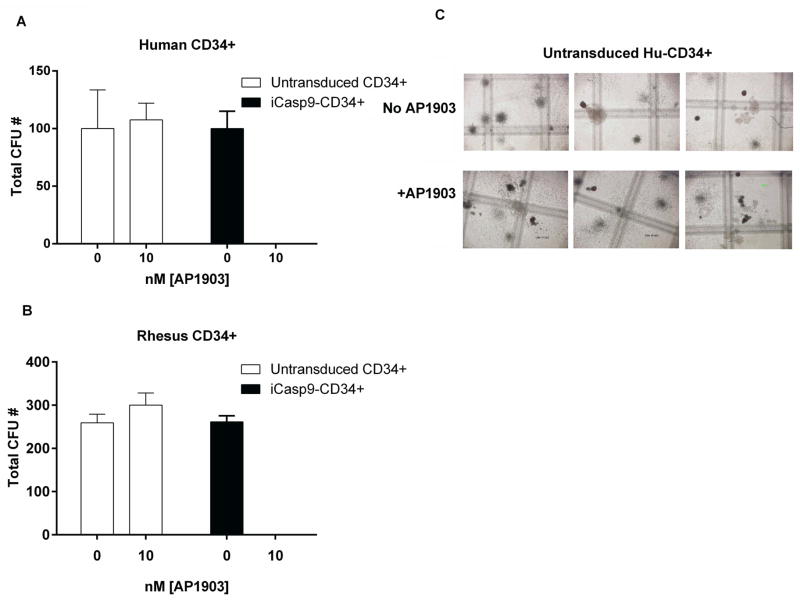

Next, we asked whether constitutive expression of iCasp9 or exposure to AP1903 influences the differentiation or proliferation of human or rhesus hematopoietic progenitors cells in vitro. Sorted iCasp9/ΔCD19+ or untransduced human and rhesus CD34+ cells were cultured for 24 hours with or without 10 nM AP1903 and then plated for colony-forming unit (CFU) assays. In the absence of AP1903, the plating efficiency and lineage characteristics of CFUs derived from iCasp9 transduced human or rhesus CD34+ cells were similar to untransduced CD34+ cells (Figure 2A, B). However, when the iCasp-9/ΔCD19+ HuCD34+ or iCasp-9/ΔCD19+ RhCD34+ cells were pre-incubated with AP1903, there was complete ablation of CFU formation, even at low (10 nM) concentrations. There was no impact of 10 nM AP1903 pre-incubation on the plating efficiency or differentiation characteristics of human or rhesus untransduced CD34+ cells (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2. Colony forming units (CFU) assays on human and rhesus CD34+ cells transduced with the SFG-iCasp9-2A-.CD19 vector.

A. Human, and B. rhesus CD34+ cells were transduced with the vector, sorted for ΔCD19, and treated or not treated with 10nM AP1903 overnight before plating in CFU assays. C. In parallel, untransduced Hu and Rh CD34+ cells were incubated overnight with 10 and 50 nM AP1903 and plated. CFU were enumerated at day 15. Abbreviations: ns (p= > 0.05; n=3)

Stable engraftment with iCasp9-transduced rhesus CD34+ cells

We evaluated the ability of iCasp-9/ΔCD19 transduced CD34+ cells to engraft in vivo, using a rhesus macaque autologous transplantation model. Three rhesus macaques were conditioned with ablative total body irradiation followed by transplantation with autologous CD34+ cells transduced with iCasp-9/ΔCD19 vector, without sorting for ΔCD19 expression prior to re-infusion (Fig. 3A). All three macaques recovered their blood counts and engrafted promptly with transduced cells, as detected by flow cytometry for ΔCD19 expression, using an antibody not cross-reacting with rhesus CD19 expressed on B cells (Fig. 3B, Fig S1). After an initial drop in marking levels, as we have observed previously, likely related to differences in transduction efficiency between early engrafting versus long-term engrafting stem and progenitor cells (23, 24), stabilization in the percentage of circulating transduced cells was achieved by 3–6 months, and these levels remained approximately constant in all three animals through the 6 to 10 month time points when AP1903 treatments were initiated. Marking was multi-lineage, as assessed by ΔCD19 flow cytometry (Fig. 3C). Bone marrow was sampled from animals A7X028 and DCLZ, and marrow mononuclear cells had similar levels of marking as circulating blood cells (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3. SFG-iCasp9-2A-ΔCD19 transduction and autologous bone marrow transplantation in rhesus macaques.

A. Summary of transduction efficiency and cell transplantation doses for three rhesus macaques transplanted with autologous CD34+ transduced with the SFG-iCasp9-2A-ΔCD19 vector. B. Marking levels in vivo as assessed by flow cytometry analysis for ΔCD19 expression in peripheral blood leukocytes of the three macaques at different time points after transplantation. C. The effect of the AP1903 therapy on the level of ΔCD19+ cells in myeloid (CD18+ and CD14+), T (CD3+), and B (CD20+) peripheral blood lineages, as assessed by flow cytometry. Levels of ΔCD19+ cells before (white bars) and 6 months after (dark bars) the last dose of AP1903 are shown. D. Flow cytometric histograms of ΔCD19 expression in PB and BM of animal A7X028 at 9 months after transplant prior to AP1903 treatment, and 45 days after AP1903 discontinuation. E. Longitudinal analysis of the level of ΔCD19+ cells as assessed by flow cytometry in macaques transplanted with SFG-iCasp9-2A-ΔCD19-transduced autologous CD34+ cells. The timelines indicates days post initial treatment with AP1903. The “PreAP1903” time point was 10 months in DCLZ and A7X028 and 6 months in A7E065, and levels were completely stable in all animals at these time points (see panel 3B above). Infusions of 0.4 mg/Kg (light gray arrows), 1.4 mg/Kg (dark gray arrows) and 4 mg/Kg (black arrows) AP1903 are indicated. F. Vector copy number as assessed by real time-quantitative PCR in PB leukocytes before initiation of AP1903 therapy and ~ 45 days after AP1903 discontinuation (right panel). The flow cytometric analyses of CD19 expresion level in PB is also presented (left panel).

AP1903 ablation of iCasp9-transduced rhesus hematopoiesis in vivo

We next tested whether in vivo administration of AP1903 could effectively eliminate cells derived from iCasp9/ΔCD19-transduced CD34+ cells. 6 months following stable engraftment with transplanted cells, an initial intravenous test dose of 0.4 mg/kg was given to animal A7E065, chosen according to the previously published human study (20). Given the lack of toxicity of the test dose, we then escalated the dose to 1.2 mg/kg in all three animals, which represents the predicted bioequivalent dose in macaques to the 0.4 mg/kg dose utilized safely in human patients. In all three animals, more than 75% of PB leukocytes expressing ΔCD19 were eliminated after infusion of 1.2 mg/kg of AP1903 (Fig. 3E 4A). In an attempt to increase the elimination of suicide gene-modified cells, three infusions of 1.2 mg/kg AP1903 were then administered, resulting in the elimination of 94% (A7E065), 83% (A7X028), and 75% (DCLZ) ΔCD19+ cells, as assessed by flow cytometry. Elimination occurred in both myeloid and lymphoid lineages in all three animals, and in the bone marrow compartments in the two animals with marrow samples assessed (Fig. 3C,D).

Fig. 4. Analyses of the characteristics of residual CD19+ cells after AP1903 therapy.

A. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for ΔCD19 in peripheral blood leukocytes from macaques transplanted with autologous transduced CD34+ cells before and after completion of AP1903. B. PBMCs from AP1903-treated macaques were cultured overnight with and without IL-2 and anti-CD3/CD28 beads and with and without AP1903. After overnight incubation the cells were assayed by flow cytomety for the expression of ΔCD19. Means of duplicate assays for each sample are shown. C. Karpas 299 cells transduced with the iCasp9-ΔCD19 vector were sorted for high (black) and low (grey) hCD19 expression and then exposed to 50nM AP1903 for 3 consecutive days in vitro (grey and black arrows indicate results after each day of in vitro dosing). Data represent means ± SEM; n=3. Abbreviations: ns= p >0.05; *** p= 0.0008. D. Western blots for expression of the cleaved fragment of caspase 9 (37 kDa) and caspase 3 (17/19 kDa) in Karpas cells transduced with SFG-iCasp9-ΔCD19 with and without exposure to AP1903 overnight. Results from the entire cell population as well as sorted ΔCD19+ cells are shown. E. Western blots for expression of uncleaved caspase 9 (47 kDa) in untransduced and transduced Karpas 299 cells. The transduced cells were sorted for high and low ΔCD19 expression by flow cytometry. Band intensities on triplicate determination normalized for actin expression are reported as mean ± SEM in the bar graphs below the blots. F. Western blot determination of expression of XIAP (53 kDa) and Bcl2 (28 kDa) in control untransduced Karpas cells, and transduced hCD19+ Karpas cells resistant to AP1903. The control and resistant cells (in duplicate) were re-exposed to 50 nM AP1903, overnight.

To confirm that the decrease of ΔCD19+ cells in the blood following AP1903 treatment accurately reflected elimination of vector-positive cells, and not down-regulation of transgene expression, we assessed vector copy number by qPCR on both peripheral blood and bone marrow specimens before and after AP1903. A copy number reduction of approximately the same magnitude as the reduction in the percentage of ΔCD19+ cells was detected, evaluated one month after discontinuation of AP1903 infusions, compared to the pre-administration levels, and were unchanged six months later (Fig. 3F).

Following the initial series of three infusions of AP1903 at 1.2 mg/kg in each animal, the reduction in the level of ΔCD19+ cells was stable for months, suggesting elimination of progenitors as well as fully differentiated cells. However, since the elimination of iCasp9 cells was not complete and we saw no toxicity of AP1903, we further escalated to 4 mg/kg for three additional doses in animals A7E065 and A7X028. There was no stable further drop in the level of ΔCD19+ cells (Fig. 3A). In spite of increasing the dose, no evidence of drug toxicity was detected in vivo, and the blood counts and blood chemistries remained normal throughout follow-up. The animals remain in good health condition now at least 2 years after completion of AP1903 therapy.

Investigation of resistance to iCasp9-mediated elimination

In order to investigate the mechanisms behind incomplete elimination of iCasp-transduced cells, we hypothesized that the level of expression of the transgenes could correlate with efficacy of AP1903-mediated ablation. We found that the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for ΔCD19 was 5 – 7.5 fold reduced in residual ΔCD19+ cells remaining following AP1903 exposure, compared to pre-exposure, in A7E065 and A7X028 (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, the MFI in DCLZ was the lowest prior to AP1903, and this animal had the least efficient killing with AP1903 in vivo. We sorted the residual iCasp9/ΔCD19+ cells remaining in the blood following AP1903 from all three animals and exposed these cells to AP1903 in vitro. Between 50–70% of the residual ΔCD19+ mononuclear cells from A7E065 and A7X028 were sensitive to relevant concentrations of AP1903 in vitro, but a minority of resistant cells persisted, and the residual ΔCD19+ cells from DCLZ showed little in vitro AP1903 sensitivity (Fig. 4B). To further confirm that these residual cells were apoptosis-resistant, we stimulated the cells with interleukin-2 and CD3/CD28 beads to induce cell activation and proliferation. Following 72 hours of in vitro stimulation, AP1903 was added. The magnitude of killing was not increased, suggesting that resistance to elimination was not simply due to cellular quiescence (Fig. 4B).

Since the number of residual vector-containing cells obtainable from the macaques post AP1903 treatment was limited, and these cells can not be studied long-term in vitro, we transduced three hematopoietic cell lines, previously tested Mycoplasma negative by touchdown PCR, with the SFG-iCasp9-ΔCD19+ vector: Karpas 299 (human T cell lymphoma), Jurkat (human T cell leukemia), and K562 (human myeloid leukemia). The transduction efficiency was 48 %; 84 %; and 47 %, respectively (Fig. S2B). Overnight treatment with either 10 nM or 50 nM AP1903 resulted in very efficient induction of apoptosis and killing of all three transduced and ΔCD19-sorted cell lines (> 97% apoptosis with 10 nM or 50 nM AP1903) (Fig. S2A). A residual 1.2–1.6% of ΔCD19+ cells remained (Fig. S2B).

In order to further investigate if the incomplete ablation with AP1903 can result from insufficient expression of iCasp9, we sorted transduced Karpas 299 cells for high and low MFI of ΔCD19. After in vitro treatment with up to three doses of 50 nM AP1903, 2.9 ± 0.3% of cells selected for high expression of ΔCD19 survived, in contrast to 18.5 ± 3.2 % of the low-expressing cells (p= 0.0008) (Fig. 4C). There was no difference in the survival of level of high versus low expressing cells without AP9013 treatment (ΔCD19high 92 ± 0.05 % vs. ΔCD19low 87.5 ± 6.1 %, p=0.5).

Transduced Karpas 299 cells were sorted for levels of ΔCD19 expression and assayed by western blot before and after AP1903 exposure. Cleaved products of both Caspase-9 and Caspase-3 were visualized in bulk and sorted cells following AP1903 exposure, confirming specific activation of the caspase-dependent apoptotic pathways after exposure to AP1903 (Fig. 4D). Protein expression of the uncleaved fragment of Caspase-9 was found to be at least 2-fold increased in ΔCD19high compared to ΔCD19low cells (Fig. 4E).

Anti-apoptotic proteins may limit the efficiency of AP1903 killing

To examine additional mechanisms of escape from AP1903 killing, we assessed the levels of endogenous inhibitors of apoptosis including XIAP and Bcl-2 by Western blot in transduced Karpas 299 cells resistant to AP1903. While basal XIAP expression was detected in this tumor cell line, it did not increase in AP1903-resistant cells, even when exposed repeatedly to AP1903 in vitro. In contrast, Bcl-2 was not detected in untransduced or transduced but untreated Karpas 299 cells, however its level increased in AP1903-resistant cells, suggesting that upregulation of Bcl-2 could be an additional potent mechanism of resistance (Fig. 4F).

Screening for mutations of the iCasp9 transgene

To ask whether resistance arose from in vivo selection for functional mutations in the iCasp9 protein, we sequenced the iCasp9 gene in genomic DNA obtained from macaque PB leukocytes before and after AP1903 therapy, and did not detect mutations in residual vector-positive cells following AP1903 treatment. We also sequenced iCasp9 in transduced resistant Karpas 299 cells, following single cell cloning of 30 resistant individual clones, and found no mutations, at least indicating that resistance mutations were not a common mechanism for the development of resistance to AP1903 (data not shown).

Discussion

While much progress has been made in the design of safer, integrating gene transfer vectors, the risk of an adverse event remains. Therefore, incorporation of a suicide gene into gene transfer vectors as a safety switch is an attractive concept, particularly when targeting HSPCs, a cell population that appears particularly prone to transformation via insertional mutagenesis (27). We previously reported that rhesus HSPCs and their progeny transduced with a highly sensitive mutant of the herpes simplex thymidine kinase gene could be completely eliminated in vivo by ganciclovir therapy (14). Here we report on the efficacy and safety of suicide gene-mediated elimination of transduced primate hematopoietic cells in vivo utilizing an inducible Caspase-9 transgene, activated by the chemical inducer of dimerization, AP1903, in a rhesus macaque transplantation model. Human and rhesus CD34+ cells transduced with the vector and analyzed in vitro had normal viability, colony formation and differentiation. Autologous rhesus macaque CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells transduced with the vector engrafted stably in vivo, and differentiated normally, producing circulating mature myeloid and lymphoid cells at levels similar to our prior rhesus macaque studies with non-iCasp9 vectors (24, 28). There was no evidence for spontaneous activation of the iCasp9 apoptotic transgene, or any impact on normal hematopoiesis, since prior to AP1903 treatment, the levels of circulating transduced cells remained stable for up to 10 months.

AP1903 administration was safe and quite effective, resulting in the immediate and stable elimination of 75–94% of suicide-gene modified cells, even after a single dose. However, a ΔCD19low population, expressing less iCasp9, persisted despite repetitive treatments with escalating doses of AP1903. This suggests a threshold concentration of iCasp9 molecules within a cell necessary to initiate AP1903-regulated apoptosis, and even higher levels of AP1903 are not able to overcome insufficient levels of iCasp9. This is in contrast to herpes tk, an enzyme that can continue to activate GCV to a toxic form within individual cells until a threshold for cell death is reached. The efficacy of the otherwise bioinert AP1903 drug only relies on the level of expression of the iCasp9 protein, and its potency is likely not enhanced by cell proliferation, as demonstrated by our studies in which mitogen-stimulated proliferation did not enhance killing of rhesus resistant hematopoietic cells. The complete cell elimination of sensitive rhesus HSPC achieved with HSV-tk-GCV in our prior rhesus model could be explained in part by the fact that suicide gene killing was likely enhanced by increased cell cycling in response to the myelosuppressive effects of GCV, eventually recruiting more quiescent HSPCs into cell cycle and therefore rendering them susceptible to killing (14).

We observed that suicide-gene modified Karpas 299 cells surviving AP1903 treatment had unchanged levels of XIAP, a direct caspase 9 inhibitor, as compared to pre-treatment cells, but upregulated Bcl-2 levels. Bcl-2 is upstream of caspase 9 in apoptosis signaling pathways, but the caspase 9 target caspase 3 acts on Bcl-2 to further lower the threshold for apoptosis, in a positive feedback loop, thus higher Bcl-2 levels could impact on iCasp9 sensitivity. Prior studies have shown iCasp9-mediated killing to be somewhat independent of inherent apoptosis resistance but none directly investigated the role of Bcl-2(17). Our resistant cells appear to be endowed by mechanisms of survival and self-renewal that exceed the control of apoptosis mediated by iCasp9 dimerization, and these mechanisms could play a role limiting the effectiveness of induced apoptosis in cells that express insufficient iCasp9 levels, observations which should be investigated further and may suggests approaches to achieve complete ablation of vector-containing cells. Indeed a novel mechanism must be at work that allows engrafted cells with this suicide gene to survive in the presence of high doses of the drug AP1903.

Contrary to the CASPALLO trial, we did not sort the rhesus iCasp9 CD34+ cells prior to transplantation. In our prior experience, expression of transgenes is delayed in the small minority of actual true engrafting cells present within the rhesus CD34+ population, and further prolonged culture followed by additional manipulation and cell sorting is associated with markedly decreased repopulating ability in vivo, making sorting for high-expressing cells currently infeasible in HSPCs, in contrast to mature T cells. Other potential strategies to increase iCasp9 expression in all transduced cells, such as more potent promoters or alternative vector backbones, might circumvent the issue of insensitive iCasplow cells and are likely to be successful.

Conclusions

We have evaluated the safety and efficacy of the iCasp9-AP1903 suicide gene system for ablation of vector-containing HSPCs and their progeny, showing that a large fraction of cells can be ablated in vivo with well-tolerated doses of the dimerizer. This is the first time iCasp9 has been evaluated as a suicide gene in primary hematopoietic progenitor and stem cells. While results are encouraging, persistence of residual AP1903-resistant cells in vivo even following dose-escalation of AP1903 indicates that complete elimination of premalignant or otherwise dysfunctional hematopoietic cells in vivo is not yet feasible. Use of a stronger internal promoter, a more active or easily dimerized form of iCasp9, or a dual suicide gene system might overcome this issue. The lack of deteca iCasp9 mutations under the pressure of treatment is reassuring for further development of iCasp9 as a suicide gene for both HSPC applications as well as for induced pluripotent stem cell applications in regenerative medicine.

Supplementary Material

Peripheral blood leukocytes of 3 control animals were analyzed by flow cytometry for cross-reactivity of rhesus CD19 with the anti-human CD19 4G7 monoclonal antibody (BD Pharmigen catalog # 349209) utilized for these studies. A representative set of plots for one control animal is shown

A. Human tumor cell lines were transduced and sorted for ΔCD19, then untreated or treated with 10–50nM AP1903 overnight and assayed for cell death (Annexin V+ and 7AAD+ by FACS). Apoptotic percentages are shown as means ± SEM of n=2 experiments. Data normalized as described in Methods section. B. Level of ΔCD19+ in transduced cells with AP1903 treatment overnight. Means ± SEM of n=2 experiments are shown

Acknowledgments

funding:

This study was funded by the intramural research program of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. AP1903 was provided by Bellicum Pharmaceuticals. DMS is an employee of Bellicum.

The authors want to thank Malcolm Brenner, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston TX, for helpful discussions, Bellicum Pharmaceuticals, Inc. for providing AP1903, Sandra Price and Barrington Thompson, NHLBI, for expert animal care, and Daniel Fowler, NCI, for resource support.

Footnotes

No other authors have relevant conflicts of interest.

Authors contributions

CNB and CED conceived the study and wrote the paper. TCF, SES and KK performed experiments, provided technical advice, and generated critical reagents. MEM, AEK and RED performed all rhesus macaque procedures and support. DMS and AD provided critical insights and edited the paper.

References

- 1.Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Garrigue A, Wang GP, Soulier J, Lim A, Morillon E, Clappier E, Caccavelli L, Delabesse E, Beldjord K, Asnafi V, MacIntyre E, Dal Cortivo L, Radford I, Brousse N, Sigaux F, Moshous D, Hauer J, Borkhardt A, Belohradsky BH, Wintergerst U, Velez MC, Leiva L, Sorensen R, Wulffraat N, Blanche S, Bushman FD, Fischer A, Cavazzana-Calvo M. Insertional oncogenesis in 4 patients after retrovirus-mediated gene therapy of scid-x1. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3132–3142. doi: 10.1172/JCI35700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Von Kalle C, Schmidt M, McCormack MP, Wulffraat N, Leboulch P, Lim A, Osborne CS, Pawliuk R, Morillon E, Sorensen R, Forster A, Fraser P, Cohen JI, de Saint Basile G, Alexander I, Wintergerst U, Frebourg T, Aurias A, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Romana S, Radford-Weiss I, Gross F, Valensi F, Delabesse E, Macintyre E, Sigaux F, Soulier J, Leiva LE, Wissler M, Prinz C, Rabbitts TH, Le Deist F, Fischer A, Cavazzana-Calvo M. Lmo2-associated clonal t cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for scid-x1. Science. 2003;302:415–419. doi: 10.1126/science.1088547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howe SJ, Mansour MR, Schwarzwaelder K, Bartholomae C, Hubank M, Kempski H, Brugman MH, Pike-Overzet K, Chatters SJ, de Ridder D, Gilmour KC, Adams S, Thornhill SI, Parsley KL, Staal FJ, Gale RE, Linch DC, Bayford J, Brown L, Quaye M, Kinnon C, Ancliff P, Webb DK, Schmidt M, von Kalle C, Gaspar HB, Thrasher AJ. Insertional mutagenesis combined with acquired somatic mutations causes leukemogenesis following gene therapy of scid-x1 patients. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2008;118:3143–3150. doi: 10.1172/JCI35798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein S, Ott MG, Schultze-Strasser S, Jauch A, Burwinkel B, Kinner A, Schmidt M, Kramer A, Schwable J, Glimm H, Koehl U, Preiss C, Ball C, Martin H, Gohring G, Schwarzwaelder K, Hofmann WK, Karakaya K, Tchatchou S, Yang R, Reinecke P, Kuhlcke K, Schlegelberger B, Thrasher AJ, Hoelzer D, Seger R, von Kalle C, Grez M. Genomic instability and myelodysplasia with monosomy 7 consequent to evi1 activation after gene therapy for chronic granulomatous disease. Nature medicine. 2010;16:198–204. doi: 10.1038/nm.2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riviere I, Dunbar CE, Sadelain M. Hematopoietic stem cell engineering at a crossroads. Blood. 2012;119:1107–1116. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-349993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baum C, Modlich U, Gohring G, Schlegelberger B. Concise review: Managing genotoxicity in the therapeutic modification of stem cells. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1479–1484. doi: 10.1002/stem.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Modlich U, Navarro S, Zychlinski D, Maetzig T, Knoess S, Brugman MH, Schambach A, Charrier S, Galy A, Thrasher AJ, Bueren J, Baum C. Insertional transformation of hematopoietic cells by self-inactivating lentiviral and gammaretroviral vectors. Molecular therapy: the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2009;17:19191928. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montini E, Cesana D, Schmidt M, Sanvito F, Bartholomae CC, Ranzani M, Benedicenti F, Sergi LS, Ambrosi A, Ponzoni M, Doglioni C, Di Serio C, von Kalle C, Naldini L. The genotoxic potential of retroviral vectors is strongly modulated by vector design and integration site selection in a mouse model of hsc gene therapy. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:964975. doi: 10.1172/JCI37630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moiani A, Paleari Y, Sartori D, Mezzadra R, Miccio A, Cattoglio C, Cocchiarella F, Lidonnici MR, Ferrari G, Mavilio F. Lentiviral vector integration in the human genome induces alternative splicing and generates aberrant transcripts. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2012;122:1653–1666. doi: 10.1172/JCI61852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavazzana-Calvo M, Payen E, Negre O, Wang G, Hehir K, Fusil F, Down J, Denaro M, Brady T, Westerman K, Cavallesco R, Gillet-Legrand B, Caccavelli L, Sgarra R, Maouche-Chretien L, Bernaudin F, Girot R, Dorazio R, Mulder GJ, Polack A, Bank A, Soulier J, Larghero J, Kabbara N, Dalle B, Gourmel B, Socie G, Chretien S, Cartier N, Aubourg P, Fischer A, Cornetta K, Galacteros F, Beuzard Y, Gluckman E, Bushman F, Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Leboulch P. Transfusion independence and hmga2 activation after gene therapy of human beta-thalassaemia. Nature. 2010;467:318–322. doi: 10.1038/nature09328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonini C, Ferrari G, Verzeletti S, Servida P, Zappone E, Ruggieri L, Ponzoni M, Rossini S, Mavilio F, Traversari C, Bordignon C. Hsv-tk gene transfer into donor lymphocytes for control of allogeneic graft-versus-leukemia. Science. 1997;276:1719–1724. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5319.1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ciceri F, Bonini C, Marktel S, Zappone E, Servida P, Bernardi M, Pescarollo A, Bondanza A, Peccatori J, Rossini S, Magnani Z, Salomoni M, Benati C, Ponzoni M, Callegaro L, Corradini P, Bregni M, Traversari C, Bordignon C. Antitumor effects of hsv-tkengineered donor lymphocytes after allogeneic stem-cell transplantation. Blood. 2007;109:46984707. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-023416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ciceri F, Bonini C, Stanghellini MT, Bondanza A, Traversari C, Salomoni M, Turchetto L, Colombi S, Bernardi M, Peccatori J, Pescarollo A, Servida P, Magnani Z, Perna SK, Valtolina V, Crippa F, Callegaro L, Spoldi E, Crocchiolo R, Fleischhauer K, Ponzoni M, Vago L, Rossini S, Santoro A, Todisco E, Apperley J, Olavarria E, Slavin S, Weissinger EM, Ganser A, Stadler M, Yannaki E, Fassas A, Anagnostopoulos A, Bregni M, Stampino CG, Bruzzi P, Bordignon C. Infusion of suicide gene-engineered donor lymphocytes after family haploidentical haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation for leukaemia (the tk007 trial): A non-randomised phase i–ii study. The lancet oncology. 2009;10:489–500. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barese CN, Krouse AE, Metzger ME, King CA, Traversari C, Marini FC, Donahue RE, Dunbar CE. Thymidine kinase suicide gene-mediated ganciclovir ablation of autologous gene-modified rhesus hematopoiesis. Molecular therapy: the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2012;20:1932–1943. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berger C, Flowers ME, Warren EH, Riddell SR. Analysis of transgene-specific immune responses that limit the in vivo persistence of adoptively transferred hsv-tk-modified donor t cells after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2006;107:2294–2302. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garin MI, Garrett E, Tiberghien P, Apperley JF, Chalmers D, Melo JV, Ferrand C. Molecular mechanism for ganciclovir resistance in human t lymphocytes transduced with retroviral vectors carrying the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene. Blood. 2001;97:122–129. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Straathof KC, Pule MA, Yotnda P, Dotti G, Vanin EF, Brenner MK, Heslop HE, Spencer DM, Rooney CM. An inducible caspase 9 safety switch for t-cell therapy. Blood. 2005;105:4247–4254. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spencer DM, Wandless TJ, Schreiber SL, Crabtree GR. Controlling signal transduction with synthetic ligands. Science. 1993;262:1019–1024. doi: 10.1126/science.7694365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan L, Freeman KW, Khan T, Pham E, Spencer DM. Improved artificial death switches based on caspases and fadd. Human gene therapy. 1999;10:2273–2285. doi: 10.1089/10430349950016924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Stasi A, Tey SK, Dotti G, Fujita Y, Kennedy-Nasser A, Martinez C, Straathof K, Liu E, Durett AG, Grilley B, Liu H, Cruz CR, Savoldo B, Gee AP, Schindler J, Krance RA, Heslop HE, Spencer DM, Rooney CM, Brenner MK. Inducible apoptosis as a safety switch for adoptive cell therapy. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365:16731683. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhong B, Watts KL, Gori JL, Wohlfahrt ME, Enssle J, Adair JE, Kiem HP. Safeguarding nonhuman primate ips cells with suicide genes. Molecular therapy: the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2011;19:1667–1675. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramos CA, Asgari Z, Liu E, Yvon E, Heslop HE, Rooney CM, Brenner MK, Dotti G. An inducible caspase 9 suicide gene to improve the safety of mesenchymal stromal cell therapies. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1107–1115. doi: 10.1002/stem.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tey SK, Dotti G, Rooney CM, Heslop HE, Brenner MK. Inducible caspase 9 suicide gene to improve the safety of allodepleted t cells after haploidentical stem cell transplantation. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2007;13:913–924. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beard BC, Dickerson D, Beebe K, Gooch C, Fletcher J, Okbinoglu T, Miller DG, Jacobs MA, Kaul R, Kiem HP, Trobridge GD. Comparison of hiv-derived lentiviral and mlv-based gammaretroviral vector integration sites in primate repopulating cells. Molecular therapy: the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2007;15:1356–1365. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donahue RE, Kuramoto K, Dunbar CE. Large animal models for stem and progenitor cell analysis. Curr Protoc Immunol Chapter. 2005;22(Unit 22A):21. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im22a01s69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu T, Kim HJ, Sellers SE, Meade KE, Agricola BA, Metzger ME, Kato I, Donahue RE, Dunbar CE, Tisdale JF. Prolonged high-level detection of retrovirally marked hematopoietic cells in nonhuman primates after transduction of CD34+ progenitors using clinically feasible methods. Molecular therapy: the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2000;1:285–293. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takatoku M, Sellers S, Agricola BA, Metzger ME, Kato I, Donahue RE, Dunbar CE. Avoidance of stimulation improves engraftment of cultured and retrovirally transduced hematopoietic cells in primates. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:447–455. doi: 10.1172/JCI12593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kang EM, Choi U, Theobald N, Linton G, Long Priel DA, Kuhns D, Malech HL. Retrovirus gene therapy for X-linked chronic granulomatous disease can achieve stable long-term correction of oxidase activity in peripheral blood neutrophils. Blood. 2010;115:783–791. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-222760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Peripheral blood leukocytes of 3 control animals were analyzed by flow cytometry for cross-reactivity of rhesus CD19 with the anti-human CD19 4G7 monoclonal antibody (BD Pharmigen catalog # 349209) utilized for these studies. A representative set of plots for one control animal is shown

A. Human tumor cell lines were transduced and sorted for ΔCD19, then untreated or treated with 10–50nM AP1903 overnight and assayed for cell death (Annexin V+ and 7AAD+ by FACS). Apoptotic percentages are shown as means ± SEM of n=2 experiments. Data normalized as described in Methods section. B. Level of ΔCD19+ in transduced cells with AP1903 treatment overnight. Means ± SEM of n=2 experiments are shown