Abstract

Early events of MSC adhesion to and transmigration through the vascular wall following systemic infusion are important for MSC trafficking to inflamed sites, yet are poorly characterized in vivo. Here, we used intravital confocal imaging to determine the acute extravasation kinetics and distribution of culture-expanded MSC (2-6 hours post-infusion) in a murine model of dermal inflammation. By 2 h post-infusion, among the MSC that arrested within the inflamed ear dermis, 47.8±8.2% of MSC had either initiated or completed transmigration into the extravascular space. Arrested and transmigrating MSC were equally distributed within both small capillaries and larger venules. This suggested existence of an active adhesion mechanism, since venule diameters were greater than those of the MSC. Heterotypic intravascular interactions between distinct blood cell types have been reported to facilitate the arrest and extravasation of leukocytes and circulating tumor cells. We found that 42.8±24.8% of intravascular MSC were in contact with neutrophil-platelet clusters. A role for platelets in MSC trafficking was confirmed by platelet depletion, which significantly reduced the preferential homing of MSC to the inflamed ear, though the total percentage of MSC in contact with neutrophils was maintained. Interestingly, although platelet depletion increased vascular permeability in the inflamed ear, there was decreased MSC accumulation. This suggests that increased vascular permeability is unnecessary for MSC trafficking to inflamed sites. These findings represent the first glimpse into MSC extravasation kinetics and microvascular distribution in vivo, and further clarify the roles of active adhesion, the intravascular cellular environment and vascular permeability in MSC trafficking.

Keywords: Mesenchymal Stem Cells, Trafficking, Inflammation, Platelets, Neutrophils, Intravital Imaging

Introduction

The therapeutic potential of systemically infused mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSC) has been associated with their ability to accumulate at sites of inflammation. This ability is also being exploited as a cellular drug delivery system for multiple applications[1]. Unfortunately, efforts to increase MSC homing to sites of inflammation have been limited by a poor understanding of their mechanism of trafficking[2-4].

Several studies have indicated that increased MSC accumulation at a site of inflammation is associated with enhanced therapeutic benefit. In a model of myocardial infarction, augmenting MSC adhesiveness (by eliminating reactive oxygen species) increased MSC engraftment in the heart 3 days after transplantation, and was associated with improved therapeutic outcome[5]. Similarly, in another study, MSC therapeutic effect in a model of Sjögren disease was reduced after CXCR4 blockade, which decreased MSC engraftment in the salivary gland[6]. Hence, efforts are being made to enhance MSC therapeutic effect by increasing MSC trafficking to target tissues, such as increasing MSC expression of adhesion molecules that bind to endothelium[7-10].

Our current understanding of MSC trafficking behavior mostly derives from in vitro studies, based on the classical model of leukocyte homing[2, 11, 12], which emphasizes interactions with endothelium. The leukocyte model comprises tethering, rolling, and firm adhesion on activated endothelium, followed by transmigration across the endothelium, These events are mediated by complementary receptor-ligand pairs on the leukocytes and endothelium[13]. We and others have reported that MSC roll, adhere and transmigrate on endothelium in vitro[14-19]. Though MSC exhibit heterogeneous receptor expression[14], integrins and chemokines/chemokine receptors have been reported to influence MSC adhesion and transmigration[16-18]. Further, using high-resolution confocal microscopy, we found that MSC transmigration is associated with blebbing on endothelium[17].

However, MSC trafficking in vivo likely depends on additional factors besides MSC-endothelial interactions. Firstly, trapping of MSC in vessels of smaller diameter, as opposed to specific adhesive mechanisms, may partially account for the intravascular arrest of MSC. Secondly, the intravascular environment of sites of inflammation comprises non-endothelial cell types. In particular, platelets and leukocytes at sites of inflammation can act as a bridge between circulating cells and endothelium[20]. Thirdly, vascular permeability, which increases at sites of inflammation, has been proposed to facilitate MSC transmigration and accumulation[2].

Furthermore, the kinetics of MSC adhesion and extravasation at sites of inflammation is unknown. This is important for some MSC therapeutic strategies (e.g. targeted drug delivery[21]), which may be most beneficial when MSC have extravasated into interstitial tissue, instead of being adhered intravascularly in the circulation. Critically, the quantitative analysis of the acute events following MSC infusion and prior to their extravasation has not been performed.

In this study, we used intravital confocal microscopy to examine the adhesion and transmigration of MSC in a murine model of LPS-induced dermal inflammation. We observed that about half of MSC that arrest at the inflamed ear are extravascular by 6 h post-infusion. Further, MSC were equally distributed between capillaries and venules. Since MSC diameter (10-20μm) was smaller than venule diameters (=20μm), this indicated that trapping is not the only potential mechanism of MSC arrest in the inflamed ear. Notably, there was a strong association between the spatial distribution of MSC and leukocytes/platelets at the site of inflammation, and >40% of intravascular MSC were in contact with both neutrophils and platelets. Though platelet depletion significantly decreased the preferential trafficking of MSC to the inflamed ear, the extravasation rate of MSC and percentage of MSC in contact with neutrophils was unaffected. This suggests that platelets impact MSC arrest intravascularly, but not the mechanism mediating MSC contact with neutrophils following arrest. Finally, vascular permeability was increased following platelet depletion. Since preferential accumulation of MSC in the inflamed ear decreased after platelet depletion, this suggests that increased vascular permeability alone does not facilitate MSC extravasation or accumulation at sites of inflammation.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All animals were used in accordance with NIH guidelines for care and use of animals under approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School. MSC were isolated from human donors under an Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved protocol with informed consent, administered by the NIH Adult Mesenchymal Stem Cell Resource (http://dpcpsi.nih.gov/orip/cm/biological_materials.aspx).

Murine model of dermal inflammation

C57/Bl6 wild-type mice (Charles River Laboratories) were used for all in vivo studies. Immediately prior to LPS injection, mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of 20-30μl of ketamine/xylazine solution. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was reconstituted in saline to make a 10mg/ml stock solution. The stock solution was diluted in saline to make a working solution of 1mg/ml, and 30μl of the working solution was injected beneath the dermis of the left ear of mice. 30μl of saline was injected beneath the dermis of the control, contralateral ear. Mice were used 24 h following LPS and saline injection.

Platelet depletion

To deplete platelets from mice prior to MSC infusion, animals were weighed and injected with 2mg/kg of polyclonal anti-GPIbβ antibody, unconjugated (Emfret Analytics, Eibelstadt, Germany). Control animals were weighed and injected with 2mg/kg of polyclonal non-immune rat immunoglobulins (Emfret Analytics, Eibelstadt, Germany). The platelet-depleting and control antibodies were injected 1h prior to MSC infusion.

MSC culture

Frozen vials of primary human bone marrow-derived MSC were obtained from the NIH Adult Mesenchymal Stem Cell Resource, located in the Texas A&M Health Science Center, College of Medicine, Institute for Regenerative Medicine at Scott & White Hospital (Temple, TX; http://medicine.tamhsc.edu/irm/msc-distribution.html). These MSC were isolated from the iliac crest of the hip bone of healthy consenting donors. Donors were normal, healthy adults, at least 18 years of age, with a normal body mass index and free of infectious diseases (as determined by blood sample screening performed 1 week before bone marrow donation). In these studies, MSC from three different donors (Donor IDs 7081, 7083, 8004) were used. MSC were maintained in StemPro MSC serum free media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), at 37°C, 5% CO2, and media were changed every 2-3 days. Cells were cultured to 90% confluence before passaging. MSC between passages 3-6 were used.

Preparation of MSC for systemic infusion

Prior to infusion, MSC were trypsinized with 0.05% Trypsin/EDTA, and resuspended in 10μM DiI, DiO, DiD or DiR solutions. This method of labeling MSC for detection in our model of inflammation has previously been validated[22]. MSC solutions were incubated for 15 min at room temperature in the dark, then washed twice in 10ml PBS before being resuspended at 200,000 or 500,000 cells/100μl. In kinetics experiments, 3 differently labeled groups of 200,000 MSC were injected retro-orbitally 6 h, 4 h and 2 h before imaging (i.e. a total of 600,000 MSC were injected). In experiments determining the MSC association with neutrophils and platelets, 500,000 MSC were injected 3 h prior to imaging. In all other experiments involving MSC visualization, 500,000 MSC were injected 6 h prior to imaging.

Visualization of endogenous vasculature and cells in the murine ear

To visualize the vasculature of the murine ear, 50μl of a 10mg/ml FITC-conjugated dextran (MW = 2,000,000) solution or 50μl of a 2mg/ml Rhodamine-conjugated dextran (MW = 70,000) solution was injected retro-orbitally into mice 15 min prior to imaging. To visualize immune cells in the murine ear, 20μl of a 0.5mg/ml Rhodamine6G solution was injected retro-orbitally into mice 15 min prior to imaging.

To visualize neutrophils at the site of inflammation, 10μg of an anti-Ly6G antibody, clone 1A8, conjugated to AlexaFluor555 or AlexaFluor647 was injected retro-orbitally into mice 15 min prior to imaging.

To visualize platelets at the site of inflammation, 5μg of an anti-GPIbβ antibody conjugated to DyLight649 (Emfret Analytics, Eibelstadt, Germany) was injected retro-orbitally into mice 15 min prior to imaging.

Intravital imaging

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane throughout the imaging procedure. Cells and vasculature in the mouse ear were imaged non-invasively (in real time) using a custom-built video-rate laser-scanning confocal microscope designed specifically for live animal imaging[23] using a 60x water-immersion objective. Acquired images were averages of 10 frames. Microscopic fields were typically 474x488μm for quantifying the number of MSC in the LPS or saline treated ear. In experiments to determine MSC association with neutrophils and platelets, 2x and 3.2x zoom was employed, resulting in smaller microscopic fields but greater pixel resolution.

In vivo MSC trafficking experiments

In most experiments, MSC were infused retro-orbitally into mice 24 h following LPS and saline treatment of the mouse ears. Mice were then imaged at various timepoints after MSC infusion (up to 24 h post-infusion). In kinetics experiments, MSC were labeled with either DiI, DiD or DiR, and infused 2h apart. Imaging was performed 2h after the third group of MSC had been infused. In time-lapse imaging experiments, imaging was performed between 4 h and 6 h post-MSC infusion. Fields containing intravascular MSC were chosen and imaged every 5 minutes. In leukocyte-MSC correlation experiments, imaging was performed 6 h post-MSC infusion. In experiments determining MSC association with neutrophils and platelets, imaging was performed 3 h post-MSC infusion. In platelet depletion experiments, platelet-depleting antibodies were infused 1 h prior to MSC infusion. Imaging was performed 6 h and 24 h post-MSC infusion.

To quantify the number of MSC and immune cells (leukocytes and platelets) accumulating in the ear, 20 random microscopic fields of 474x488μm were imaged in the region of LPS and saline injection in each experiment. To quantify the number of MSC in contact with neutrophils or platelets in the ear, at least 30 random MSC were imaged in each experiment.

Image analysis

Image analysis was performed using the open source software ImageJ and VAA3D (www.vaa3d.org). Image J was used for cell enumeration and measurement of vessel diameters. VAA3D was used to perform three-dimensional reconstructions of confocal image stacks to classify MSC positions as being (i) intravascular (completely within a vessel), (ii) transmigrating (partly within and partly outside a vessel) or (iii) extravascular (completely outside a vessel), and to determine which vessels they were associated with.

Permeability assays

To assess vascular permeability in mouse ears, anesthetized mice were infused with 20μl of Evans Blue (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) via the inferior vena cava. 30 min later, a needle was inserted into the right ventricle of the mouse, and the vasculature of the mouse was flushed with 20ml of an ice-cold solution of 100U/ml heparin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in phosphate buffered saline. The region of LPS or saline injections in the mouse ears were isolated and minced. The tissue was then weighed and incubated in a volume of formamide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) proportional to the mass of the tissue overnight at 56°C to extract Evans Blue. The amount of Evans Blue was then measured, by measuring the absorbance of the formamide containing the tissue at 620nm using a UV spectrophotometer.

Statistical analysis

For comparisons between 2 groups, Student’s t tests were used. Comparisons between multiple groups (>2) were performed with one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post-hoc test, or with two-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s post-hoc test. Pearson analysis was used to test for correlations. Results were presented as mean ± standard deviation for n=3. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences of p<0.05 (*), p<0.01 (**) and p<0.001 (***).

Results

MSC arrest and extravasate within 2 hours post-infusion in both capillaries and venules

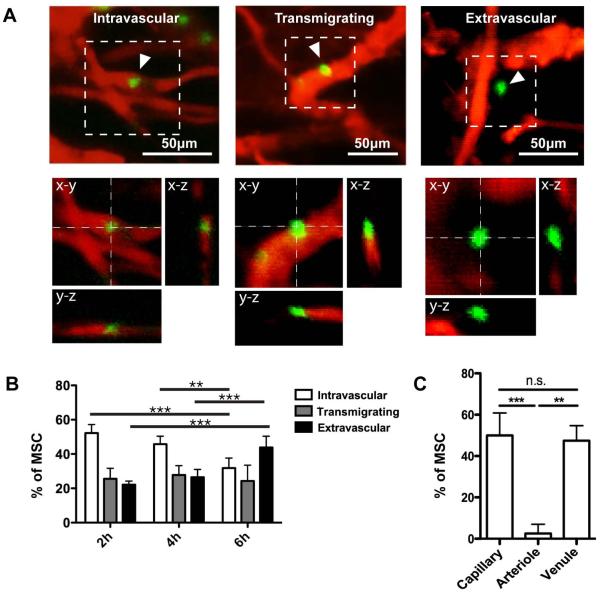

The kinetics of systemically infused MSC arrest and extravasation at sites of inflammation have not been explored. Thus, we designed studies to infuse fluorescent MSC and image their recruitment to inflamed skin at time points of 0.5, 2, 4 and 6 h post-infusion by intravital confocal microscopy. Our preliminary experiment showed that few MSC were evident in the inflamed skin 0.5 h following infusion (not shown), but significant quantities of MSC accumulated by 2 h. We therefore focused subsequent quantitation and analyses on the 2, 4 and 6 h time points. First, we determined the location of MSC with respect to the blood vessel wall (delineated by circulating fluorescent dextran) through serial-section 3-dimensional imaging. MSC were thus classified as being (i) arrested intravascularly, (ii) transmigrating (i.e., spanning both intra- and extra-vascular space) or (iii) in the extravascular space (Fig. 1A and Supp. Video 1-3) and quantified the fraction of each class at 2, 4 and 6 hours post-infusion (Fig 1B). By 2h post-infusion, 47.8±8.2% of MSC were observed transmigrating or extravasated. The percentage of extravasated MSC doubled from 22.2±2.1% at 2 h, to 43.9±6.5% at 6 h.

Figure 1. Extravasation kinetics and distribution of MSC in the inflamed ear.

Systemically infused MSC (green) were imaged 2, 4 and 6 h post-infusion in the inflamed ear using intravital confocal microscopy. Blood vessels (red) were visualized using fluorescent dextrans. (A): MSC were classified according to intravascular, transmigrating and extravascular positions. Representative images of MSC in each position are shown as z-projections and orthogonal projections. (B): The percentages of MSC in each position at different time points post-infusion were quantified. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-hoc test was used (n=4). (C): The percentages of MSC associated with capillaries (vessel diameter <20μm), arterioles and venules were quantified (n=4). Arterioles and venules were differentiated based on blood flow rate and tortuosity of vessels. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test was used (n=4). Values are mean±SD. Asterisks represent p<0.05(*), p<0.01(**) and p<0.001(***); n.s. = not significant.

Through time-lapse imaging, we also observed extravasation time for an individual MSC to be as short as 15 min (Supp. Fig. 1A). Interestingly, this is ~3 times shorter than what we observed previously for MSC in vitro [17]. Further, the MSC extravasation time is about 3-5 times longer than for leukocytes, but similar to what has been observed for tumor cells in an in vitro microvascular network platform[24].

We next examined the type of vessels that support MSC arrest and extravasation. Leukocytes preferentially arrest and extravasate in venules, which are larger than capillaries yet have higher levels of adhesion molecule expression and greater permeability compared to capillaries and arterioles[25]. Since MSC do not express many adhesion molecules employed by leukocytes during homing, they have been proposed to arrest in capillaries as a result of their large size (typically 10-20um in diameter in suspension)[26].

We quantified the fraction of MSC associated with vessels <20μm or =20μm in diameter in the inflamed ear. Further, the larger vessels (=20μm in diameter) were identified as arterioles or venules based on morphology, and blood flow direction and speed. To note, the smaller vessels (<20μm in diameter) include capillaries and possibly also post-capillary venules. The use of permeability measurements[27, 28] and adhesion molecule expression[25] is required to properly differentiate between capillaries and post-capillary venules (observed to be as small as 8-14μm[29], and as large as 20-40μm[30, 31]). However, since our goal was to determine the potential for MSC trapping in smaller vessels versus their adhesion in larger vessels, we chose 20μm, the upper limit of MSC diameter, as the cut-off between smaller and larger vessels. The smaller vessels (<20μm in diameter) are henceforth referred to as capillaries for convenience.

Interestingly, MSC were rarely found associated with arterioles but equally distributed between capillaries and venules, (Fig. 1C). The significant portion of MSC observed to be associated with venules of diameters greater than that of MSC, strongly suggested that an active adhesive mechanism exists between the MSC and blood vessel wall (Supp. Fig 1B).

Despite the equal distribution of cells in capillaries and venules, we also found that there were significantly more transmigrating and extravascular MSC associated with capillaries than in venules (Supp. Fig. 1C). (Extravascular MSC were not included in the analysis when the vessel they were associated with was not obvious.) This is similar to tumor cells, which preferentially extravasate in smaller versus larger vessels in an in vitro microvascular network platform [24].

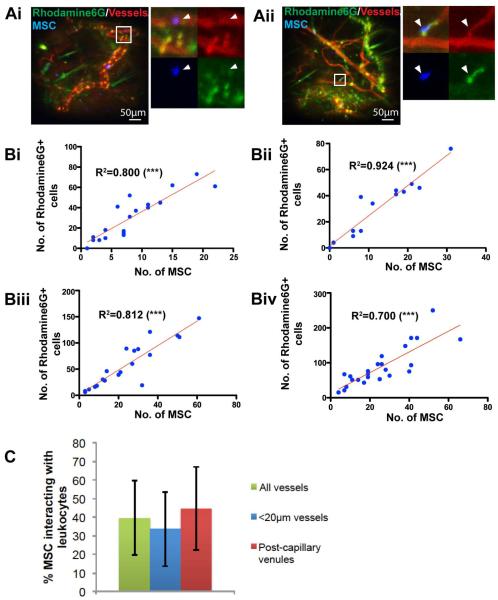

MSC and leukocytes exhibit a similar distribution in the inflamed ear

The presence of MSC in venules of diameter larger than the MSC further supported the possibility that a subset of MSC might arrest at the site of inflammation through secondary interactions with leukocytes, which preferentially arrest and extravasate in venules[25]. To elucidate if a relationship exists between MSC and leukocyte homing to sites of inflammation, we labeled endogenous, intravascular leukocytes and platelets in the mouse with Rhodamine 6G (R6G; Fig. 2A). Rhodamine 6G is a non-specific stain that binds to mitochondria in cells, commonly used to label intravascular leukocytes[32, 33]. As expected, most Rhodamine6G+ cells arrested in venules, with fewer in capillaries and arterioles (Supp. Fig 2A). We further observed that fields with many R6G-positive cells often had many MSC as well. Indeed, when we plotted the number of MSC against the number of arrested intravascular R6G+ cells in each 474x488μm microscopic field, there was consistently a strong correlation (Fig. 2B and Supp. Fig. 2B; R2 ranged from 0.700-0.924).

Figure 2. MSC and leukocyte distribution in the inflamed ear is correlated.

Systemically infused MSC (blue) were imaged 6 h post-infusion in the inflamed ear using intravital confocal microscopy. Blood vessels (red) were visualized using fluorescent dextrans, and endogenous intravascular leukocytes and platelets were visualized using Rhodamine 6G (green). (A): MSC were often observed in proximity to Rhodamine6G+ cells, and could be classified as being in contact or not in contact with Rhodamine6G+ cells. Insets (white boxes) in Ai and Aii show representative images of MSC (white arrowheads) not in contact or in contact with Rhodamine6G+ cells respectively. See also Supp. Fig. 2A. (B): The numbers of MSC and Rhodamine6G+ cells found in each microscopic field were quantified for at least 15 microscopic field in each of 4 independent experiments. The numbers of MSC and Rhodamine6G+ cells for each field were plotted against each other. Pearson’s correlation was used. (C): The percentages of MSC interacting with leukocytes in all vessels, only capillaries (vessel diameter <20μm) and only venules were quantified. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test was used (n=4). Values are mean±SD. Asterisks represent p<0.05(*), p<0.01(**) and p<0.001(***); n.s. = not significant.

Further, to determine if there was a physical association between MSC and leukocytes/platelets, we quantified the percentage of MSC and R6G+ cells in contact with each other (Fig. 2A). In this manner, we found that 39.5±20.1% of MSC were in contact with leukocytes/platelets across all vessels, with a greater percentage in vessels of diameter =20 μm compared to smaller vessels (Fig. 2C; p=0.218). This latter observation is likely because leukocytes were more commonly found in venules.

Three possibilities might account for the strong correlation between MSC and leukocyte/platelet distribution. First, related signals regulate both MSC and leukocyte/platelet accumulation in the inflamed ear. Second, leukocytes/platelet facilitate MSC accumulation in the inflamed ear. Third, MSC facilitate leukocyte/platelet accumulation in the inflamed ear. Based on our observations that a large percentage of MSC were apparently in direct contact with leukocytes/platelets and that there were many localized leukocytes not in contact with MSC, we decided to explore the second possibility.

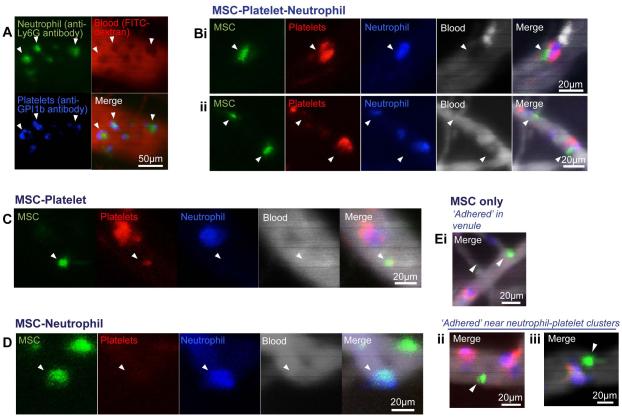

MSC are found in contact with, or in close proximity to, neutrophil-platelet clusters

To facilitate our investigation of the role of leukocytes/platelets in facilitating MSC homing, we decided to focus specifically on neutrophils and platelets.

We chose these two circulating cell types for several reasons. First, neutrophils and platelets are typically the first responders during acute inflammation, and are found abundantly at the site of inflammation[34]. Second, platelets have previously been implicated in MSC accumulation at sites of inflammation[19, 35]. Third, we observed intravascular neutrophil-platelet clusters to exist at baseline (i.e. LPS-induced inflammation without MSC infusion) using antibodies toward the neutrophil-specific Ly6G antigen and platelet-specific GPI1b antigen (Fig. 3A). The area of platelet-specific fluorescence signals was often comparable to that of neutrophils. Since the diameter of a single platelet is typically 1-3μm, while neutrophils are 3-5 times larger, we believe that the neutrophil-platelet clusters comprised multiple platelets. This is consistent with other studies that have also found platelet-leukocyte complexes with multiple platelets adhered to each leukocyte[36, 37].

Figure 3. Large fraction of intravascular MSC found in contact with neutrophils and platelets.

Systemically infused MSC (green) were imaged 3 h post-infusion in the inflamed ear using intravital confocal microscopy. Endogenous, intravascular neutrophils (N; blue) and platelets (P; red) were labeled using antibodies toward murine Ly6G and murine GPI1b, respectively. Blood vessels were visualized using fluorescent dextrans (red in A, white in all other panels). (A): Representative images of intravascular P-N clusters (white arrowheads) found in the inflamed ear at baseline, without MSC infusion. (B-D): Representative images of intravascular MSC found in contact with P-N clusters (B), with P only (C), or with N only (D). (E): Representative images of intravascular MSC (white arrowheads) not in contact with P or N, could be found in vessels of diameters larger than the cell diameter, indicating an adhesive mechanism for their arrest (i). It was not uncommon to find MSC ‘adhered’ near to P-N clusters (ii, iii).

When we systemically infused MSC, we found 42.8±24.8% of intravascular MSC in contact with these neutrophil-platelet clusters (Fig. 3B and Fig. 5A). Of the remaining intravascular MSC, 15.0±6.8% were found with platelets only (Fig. 3C), 4.36±2.70% were found in association with neutrophils only (Fig. 3D), and the remaining 37.8±25.3% were neither in contact with neutrophils nor platelets (Fig. 3E). We also frequently observed lone MSC near, but not in contact with the neutrophil-platelet clusters (Fig. 3Eii,iii). The percentage of MSC found in contact with neutrophils here (47.2±26.5%) is similar to the percentage of MSC previously found in contact with R6G+ cells (39.5±20.1%).

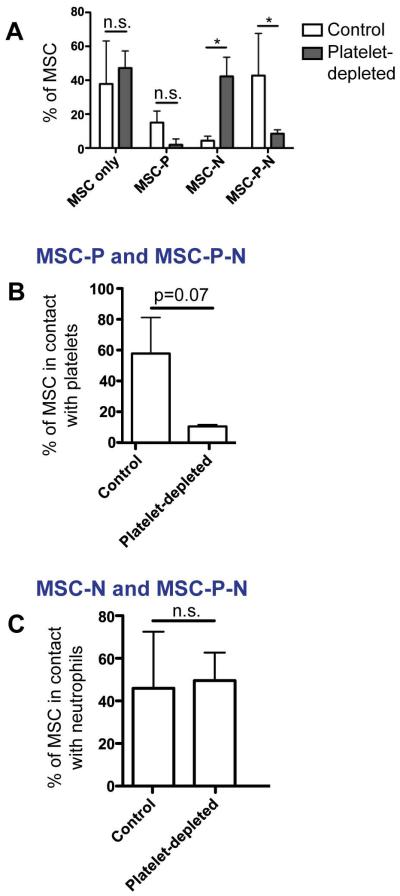

Figure 5. Fraction of intravascular MSC in contact with neutrophils is maintained after platelet depletion.

To determine how platelets affected MSC contact with neutrophils, we imaged at least 30 random intravascular MSC in the inflamed ear of control and platelet-depleted MSC. Platelets (P) and neutrophils (N) were visualized using antibodies towards murine Ly6G and murine GPI1b, respectively. (A): The percentages of MSC not found in contact with P or N (“MSC only”), found in contact with P only (“MSC-P”), found in contact with neutrophils only (“MSC-N”) and found in contact with both P and N (“MSC-N-P”), was compared for control and platelet-depleted animals. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-hoc test was used (n=3). (B, C): The total percentages of MSC found in contact with P (B; sum of MSC-P and MSC-P-N) and N (C; sum of MSC-N and MSC-P-N) were compared for control and platelet-depleted animals. Paired student’s t-test was used (n=3). Values represent mean±SD. Asterisks represent p<0.05(*); n.s. = not significant.

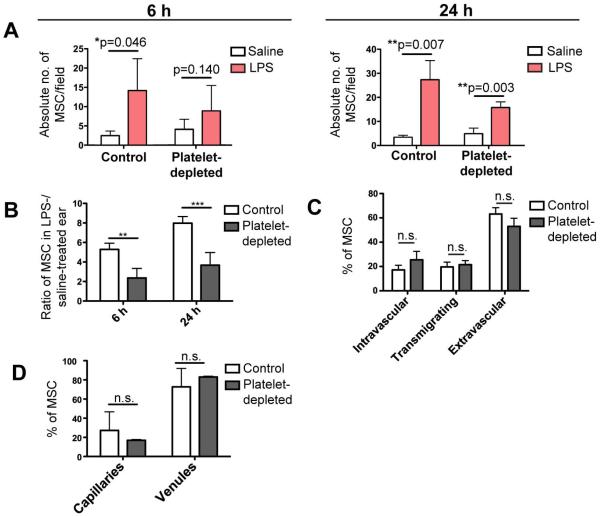

Platelet depletion decreases MSC trafficking to the inflamed ear

Since more than half of intravascular MSC were associated with platelets, we quantified MSC trafficking to the inflamed ear following platelet depletion. Preferential MSC trafficking to the inflamed ear remained after platelet depletion at both 6h and 24h (Fig. 4A). To further understand how preferential MSC trafficking to the inflamed ear was affected after platelet depletion, we compared the ratio of MSC that accumulated in the LPS-treated ear to the control (saline-treated) ear of the same animal. We found the ratio of MSC numbers in the LPS- versus saline-treated ears of each mouse was significantly decreased by more than 50% at both 6h and 24h following infusion (Fig. 4B; At 6h, 5.29±0.63 decreased to 2.36±0.98; At 24h, 7.98±0.67 decreased to 3.67±1.31). This suggested that platelet depletion affected a mechanism that facilitates enhanced MSC trafficking to the inflamed ear.

Figure 4. Platelet depletion decreased preferential trafficking of MSC to inflamed ear.

To determine if platelets facilitate MSC homing, platelets were depleted prior to MSC infusion. Random microscopic fields of both the inflamed, LPS-treated ear, and contralateral, saline-treated ear were imaged at 6 h and 24 h post-infusion, and the average numbers of MSC per field were quantified for both. (A): The absolute number of MSC per microscopic field in the LPS-treated and saline-treated ear of both control and platelet-depleted animals were compared. Paired student’s t-test was used to compare both groups at each time point (n=4). (B): The ratios of number of MSC in the LPS-treated ear versus the saline-treated ear were compared for control and platelet-depleted animals. Paired student’s t-test was used to compare both groups at each time point (n=4). (C): The extravasation rate of arrested MSC in the inflamed ear was compared for control and platelet-depleted animals, by quantifying the percentages of MSC in intravascular, transmigrating and extravascular positions. Paired student’s t-test was used to compare both groups for each position (n=4). (D): The distribution of MSC between capillaries (vessel diameter <20μm) and venules in the inflamed ear at 6 h post-infusion was compared for control and platelet-depleted animals. Paired student’s t-test was used to compare both groups at each time point in A, each position in B or for each vessel type in C (n=4). Values represent mean±SD. Asterisks represent p<0.05(*), p<0.01(**) and p<0.001(***); n.s. = not significant.

We further determined that the extravasation capacity of the MSC was not affected by platelet depletion by quantifying the percentage of MSC in the (i) intravascular, (ii) transmigrating and (iii) extravascular position (Fig. 4C). There was no significant difference between the percentage of MSC in each stage under both control and platelet depleted conditions suggesting that platelet depletion affects events upstream of MSC extravasation, i.e. MSC arrest. Similarly, the distribution of MSC in capillaries and venules within the inflamed ear was not affected (Fig. 4D).

MSC-neutrophil contact following MSC arrest is independent of platelets

Since previous studies suggested that platelets could act as a bridge between circulating tumor cells and other cells[20], we aimed to determine how platelet depletion affected MSC contact with neutrophils. We quantified the percentages of intravascular MSC, which were (i) not in contact with neutrophils or platelets (“MSC only”), (ii) in contact with either platelets or neutrophils only (“MSC-P” and “MSC-N”), or (iii) in contact with both neutrophils and platelets (“MSC-P-N”) in the LPS-treated ear of control and platelet depleted mice (Fig. 5A). As expected, the total percentage of MSC in contact with platelets (MSC-P and MSC-P-N) decreased by more than seven-fold following platelet depletion (Fig. 5B). Surprisingly though, the percentage of MSC in contact with neutrophils (MSC-N and MSC-P-N) was maintained (Fig. 5C). With our findings that platelet depletion decreased MSC accumulation in the inflamed ear, this shows that platelets impact the number, but not percentage, of intravascular MSC in contact with neutrophils. Hence, platelets impact MSC arrest (which may potentially be due to MSC-neutrophil contact), but likely not the mechanism maintaining MSC-neutrophil contact following arrest.

One possible indirect mechanism of MSC-neutrophil adhesion is via newly described neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). During certain types of inflammation and immune reactions (including LPS-induced inflammation) neutrophils have been shown to extrude their nuclear DNA into the extracellular environment forming an adhesive meshwork of material, a process termed ‘NETosis’[38, 39]. These NETs can be found intravascularly, where they can trap bacteria and circulating tumor cells[40, 41]. Significantly, platelet-neutrophil adhesion has been shown to be important for NET formation[41-43], hence one would expect fewer NETs after platelet depletion, which would potentially provide fewer sites for MSC arrest.

We indeed found that MSC adhered to thick webs of NETs in vitro (Supp. Fig. 3). Though NETs typically comprise thin DNA strands not visible at the resolution of epi-fluorescence microscopy, their fragility causes the thin strands to coalesce into thick webs of NETs during the washing and removal of non-adherent MSC. In certain instances, we observed MSC solely in contact with the NETs, without any contact with neutrophils. These MSC were suspended in bridge-like strands of NETs, strongly suggesting that that MSC can adhere directly to NETs.

However, we did not find any evidence for the presence of NETs in our in vivo model. We systemically infused Sytox Green, a DNA-labeling dye, into mice but found that almost all Sytox Green-labeled structures in the LPS-treated ear were extravascular (Supp. Video 1). This suggests that while MSC may be able to adhere to NETs, NETs are not a mechanism of intravascular adhesion in our model.

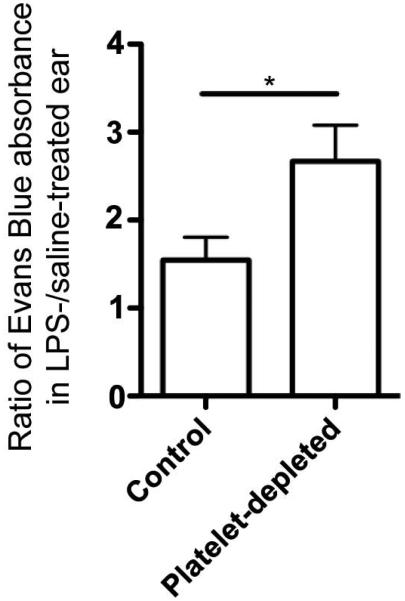

Increased vascular permeability associated with reduced MSC trafficking

Of note, platelets are known to affect vascular permeability under both physiological and pathological states[44-46]. As it has been previously proposed that MSC arrest or extravasation occurs as result of increased vascular permeability at sites of inflammation[2], we determined if permeability changed after platelet depletion in our model. To do so, we systemically infused Evans Blue into both control and platelet-depleted mice, and measured the ratio of Evans Blue leakage in the LPS-treated ear versus the control ear. Consistent with published studies, we found that platelet-depletion indeed significantly increased vascular permeability in the inflamed ears of mice (Fig. 6), which was surprisingly coupled to decreased MSC accumulation in parallel. This strongly suggests that increased vascular permeability on its own cannot account for the increased MSC accumulation at sites of inflammation.

Figure 6. Vascular permeability in inflamed ear increases after platelet depletion.

To determine how platelet depletion affected vascular permeability in the inflamed ear, Evans Blue leakage in the ear was measured. The ratio of Evans Blue absorbance in the inflamed, LPS-treated ear versus the control, saline-treated ear was compared for control and platelet-depleted animals. Paired student’s t-test was used (n=4). Values represent mean±SD. Asterisks represent p<0.05(*).

Discussion

In this study, we have investigated the trafficking of MSC in a model of dermal inflammation following systemic infusion. Though the term ‘MSC’ is controversially used to represent different populations of cells[47, 48], we chose to explore the trafficking of culture-expanded, human bone marrow-derived MSC defined by standards described by the International Society of Cellular Therapy[49]. We chose this population of cells because they are widely used experimentally and in clinical trials. Importantly, MSC defined in this way represent a highly heterogeneous population of cells (in size, surface marker expression, differentiation potential, clonogenicity etc.), hence it is unlikely that a single mechanism can account for the accumulation of all MSC at sites of inflammation in vivo.

To our knowledge this is the first study that has employed in vivo confocal microscopy to quantitatively examine the adhesion and extravasation dynamics of systemically infused MSC at a site of inflammation. This study was performed as a follow up to our previous study where we imaged the cellular processes mediating MSC transmigration through endothelium in vitro[17]. Unlike in vitro experiments where endothelial monolayers are a limited approximate to the inner lining of blood vessels, here we were able to quantify the dynamics of MSC extravasation through the vascular wall at a site of inflammation. We found that more than 20% of MSC were extravasated as early as 2 h following infusion, and that this percentage more than doubles by 6 h. The kinetics of extravasation is relevant to current MSC studies for several reasons.

First, numerous studies that have examined MSC trafficking to tissues and organs focus on late time points, typically 24 h post-infusion or later. Since MSC can adhere and extravasate much earlier than 24 h, it is unclear if such studies are actually measuring an effect on adhesion and extravasation capacity, or the survival of extravasated MSC within interstitial tissue.

Second, a significant debate within the MSC field is whether MSC exert their immunosuppressive effects via a systemic or local mechanism. While this is a complex topic, a better understanding of the timing of MSC extravasation at the site of inflammation (when they can exert local effects) compared to the initial observation of a functional immunosuppressive effect can be helpful to address this question. For example, in one study, the migration of activated dendritic cells to the lymph node (a pro-inflammatory) effect, was reduced within 10 minutes of systemic infusion of MSC[50]. Based on our data that few MSC are present at the site of inflammation 0.5 h after infusion, it is unlikely that a local immunosuppressive effect was exerted by MSC in this model.

Third, MSC are being explored as local drug delivery carriers due to their ability to preferentially traffic to sites of inflammation, including tumors[21, 51, 52]. An understanding of the kinetics of MSC arrival and extravasation at the site of inflammation, versus the kinetics of drug release by MSC will be important to avoid unwanted systemic side effects.

The majority of systemically infused MSC are sequestered in the small capillaries in the lung immediately post-infusion, a phenomenon common to many infused cell types, including stem cells and neutrophils[26, 53]. Several studies have implicated adhesive interactions in mediating this sequestration. For example, a deficiency of L-selectin did not prevent lung sequestration post-infusion, but did reduce the duration for which neutrophils were sequestered[53]. Similarly, pretreating MSC with a blocking antibody to the α4 integrin also reduced their duration of sequestration in the lung[26]. Our analysis showed that MSC were equally distributed between capillaries and venules in the inflamed ear. Their presence in vessels of diameter larger that that of MSC, helps to confirm the role of an active adhesive mechanism for the arrest of at least a subset of the MSC. This is consistent with a previous study where MSC were observed to adhere directly to the injured arterial lumen within 5 minutes of infusion in a model of carotid artery ligation[19]. The factors that determine MSC arrest in a capillary or venule require further study. Additionally, MSC populations are known to comprise subsets of cells with heterogeneous size[54] and surface molecule expression[55]. It is conceivable that larger MSC may arrest in capillaries, while smaller MSC with greater adhesion molecule expression arrest in venules.

Care should be taken when extending our results to MSC distribution in other microvascular beds, however, as blood vessels are a highly heterogenous anatomic compartment[56]. Site-specific endothelial characteristics and intravascular cell traffic likely influence the distribution of MSC in each tissue bed. For example, we have found that significant MSC extravasation and engraftment occurs in the calvarial bone marrow regardless of inflammation[7], while few MSC traffic to the non-inflamed ear in our study. It is also unclear if similar mechanisms mediate MSC trafficking to inflamed and non-inflamed tissues.

The current studies focus on the microvascular blood vessels (i.e., arterioles, capillaries and venules). It is interesting to consider whether meaningful interactions also take place between MSC and lymphatic microvessels (i.e., lymph capillaries) in vivo. To our knowledge, MSC have never been isolated from lymph or identified within lymphatic vessels. Yet, some recent studies indicate that systemically infused MSC can be found in secondary lymphoid organs, (e.g., Mesenteric lymph nodes after intracardiac infusion[57], lymph nodes, Peyer patches, spleen[58]. However, it remains unclear as to whether these arrived via trafficking through to high endothelial blood vessels or via the lymphatic vessels. Of course migration into secondary lymphoid organs via lymphatic vessels would require that intravascularly infused MSC first extravasate out of blood vessels, then migrate through tissues and finally intravasate into lymphatic vessels[59]. Though an investigation of this possible trafficking pattern was beyond the scope of the current study, we would suggest that this would seem unlikely to be a major route given that MSC (similarly to most effector leukocytes, other than dendritic cells) are largely attracted to inflammatory stimuli and that migration into lymphatic vessel and ultimately secondary lymphoid organs requires moving away from the inflammatory stimulus[59]. Nonetheless, the potential for such trafficking events, putative mechanisms and potential functional roles represent important questions for future investigation.

However, it seems that intravasation may utilize distinct mechanisms from extravasation for some cell types. In contrast to other studies that emphasized the importance of adhesive interactions[60, 61], dendritic cells were found to access afferent lymphatic vessels through preformed portals, independent of adhesive interactions and any pericellular proteolysis[62]. Taken together, it seems at least possible, that MSC might exhibit functionally meaningful trafficking through lymphatic vessels and that during such migration the mechanisms could be similar or different to those used for migration across blood vessels.

Interestingly, we found that the majority of intravascular MSC could be found in contact with platelets or neutrophils in the inflamed ear. Previously, the MSC integrin αVβ3, and platelet surface molecules P-selectin and GPIIb/IIIa, have been shown to mediate adhesion of activated platelets, but not resting platelets, to MSC in vitro[19, 35]. To note, a significant minority of intravascular MSC (37.8±25.3%) could also be found neither in contact with platelets nor neutrophils. Since images of each region in the inflamed ear were acquired at a single time-point, it is difficult to tell if this subset of MSC were in contact with platelets or neutrophils at some point during their intravascular arrest. Further, the heterogeneity of MSC raises the possibility that different subsets of MSC have varying affinity for platelets and neutrophils, due to variable surface marker expression.

Nonetheless, a role for platelets in MSC trafficking, for at least a subset of MSC, was confirmed by our finding that platelet depletion decreased preferential homing of MSC to the inflamed ear. A previous study showed that platelet depletion decreased MSC adhesion to a site of arterial ligation[19]. While endothelium is denuded to expose subendothelial extracellular matrix during arterial ligation, in our model endothelium is intact, hence the mechanisms of MSC arrest in the two studies are expected to be different. Furthermore, in the previous study, platelet depletion was initiated 16 h prior to arterial injury and MSC infusion, which allowed an extended time for multiple downstream inflammatory processes (e.g. levels of circulating platelet secreted factors) to be affected. To decrease impact of platelet depletion on other inflammatory processes, we initiated platelet depletion after induction of inflammation and just 1 h prior to MSC infusion and found that a decrease in MSC adhesion was still observed. This suggests that direct MSC-platelet interactions are responsible for MSC arrest on intact endothelium at the inflamed site.

The mechanism by which platelet depletion decreases MSC accumulation at inflamed sites is still unclear and will be addressed in future work. Previous in vitro experiments suggest that platelets may facilitate MSC disruption of the endothelial barrier[19]. This contradicts our finding that the percentage of extravasated MSC is unaffected by platelet depletion. Based on our findings, platelet depletion likely affects events upstream of MSC extravasation. These events can be categorized into two main groups affecting: (i) The availability of MSC in the circulation, and (ii) adhesive interactions between the MSC and endothelial wall. Platelets might affect the availability of MSC in circulation by protecting MSC from natural killer cell lysis as previously shown for tumor cells[63]. However, it is unlikely that the availability of MSC accounted for the decrease in MSC accumulation in our model, since not only absolute numbers of MSC, but also the preferential accumulation of MSC in the inflamed ear were decreased.

Compared to the role of platelets in affecting MSC availability in circulation, the role for platelets in mediating direct or indirect adhesive interactions between MSC and the endothelial wall would seem more likely. Such a role is supported by a previous study that found that blocking MSC-platelet adhesion via the platelet receptor, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa, decreased MSC accumulation in a model of lung injury[35]. Conceivably, intravascular platelets adhered at the inflamed site may act as a bridge for MSC to adhere to endothelium, as has been proposed for tumor cells[20]. Alternatively, platelet microparticles have been known to bind to hematopoietic stem cells, and increase their engraftment[64]. The role of platelet microparticles in MSC trafficking has not been explored.

Interestingly, we found that the platelet depletion did not affect the percentage of intravascular MSC in contact with neutrophils, although the number of MSC in contact with neutrophils decreased. This result requires further investigation to determine if MSC-neutrophil interaction is a result of random interactions or platelet-associated adhesive mechanisms. Minimal evidence exists for direct MSC-neutrophil adhesion. Unfortunately, LPS-induced inflammation and neutrophil depletion both require a significant stabilization time delay (e.g. 24 hours) prior to infusion of MSCs. Thus the addition of neutrophil-depleting antibodies would have likely affected the induction of inflammation. However, MSC expression of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 has been observed[65]. Since neutrophils also adhere to endothelium at inflamed sites via endothelial ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression, it is reasonable to conceive that neutrophils might similarly adhere to MSC. Future studies blocking neutrophil trafficking to sites of inflammation may help to elucidate the role for neutrophils in facilitating MSC trafficking.

Another role for platelets that we considered in our experiments was their function in maintaining endothelial permeability. Platelet depletion has been shown to both increase and decrease endothelial permeability in different studies, in both physiological and pathological states[44-46]. This is significant as MSC trafficking to inflamed sites has been thought to be facilitated by increased endothelial permeability, e.g. MSC may take advantage of intercellular endothelial gaps to directly invade interstitial tissue[2]. Indeed, although leukocyte extravasation is a much better understood process, the role of endothelial permeability in leukocyte extravasation is still controversial[66-69]. To our surprise, we found that the increased endothelial permeability in our experiments (following platelet depletion) was associated with decreased MSC accumulation at the site of inflammation. Furthermore, the percentage of extravasated MSC in the inflamed ear following platelet depletion was unchanged, suggesting that MSC extravasation at inflamed sites is not dependent on endothelial gaps or permeability. This is consistent with our previous study where we demonstrated that MSC can transmigrate transcellularly (i.e. directly through an endothelial cell), and does not require pre-existing endothelial gaps[17].

The role of platelets in facilitating MSC trafficking should be strongly considered, especially when designing and analyzing results from MSC clinical trials where patients may receive anti-platelet agents or other anti-inflammatory drugs. Indeed, MSC clinical trials have had variable results, and multiple trials have failed to meet their primary endpoints. One example is the SWISS-AMI trial, where post-myocardial infarction patients all received the standard treatment - aspirin and one of 2 ADP P2Y12 inhibitors (clopidgrel or prasugrel)[70]. All three drugs are anti-platelet agents. These drugs might have reduced MSC trafficking to the injured cardiac tissue in the trials, and contributed to the failure of systemically infused MSC to enhance cardiac regeneration in the SWISS-AMI trial. Hence, we believe that platelet levels should be closely monitored in patients participating in MSC clinical trials in the future.

Further, MSC are being designed as drug-delivery agents for tumors where they are specifically required to accumulate in tumors after systemic infusion. These strategies should consider that many patients experience chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia[71]. Additional studies will be required to determine the impact of chemotherapy on the ability of MSC to target tumor sites.

In conclusion, we have explored several factors in vivo that can influence MSC trafficking. Our results strongly support the existence of an active adhesive mechanism for MSC arrest, for at least a population of MSC, at the inflamed site in contrast to passive mechanical trapping in small diameter vessels. Further, by visualizing the intravascular cellular environment of the MSC, we found that platelets, and possibly also neutrophils, play a significant role in regulating MSC trafficking perhaps via secondary adhesive interactions. Finally, we demonstrated that endothelial permeability does not appear to facilitate MSC accumulation and extravasation. This advances our knowledge of MSC trafficking, which has largely been restricted to MSC-endothelial interactions. Due to the inherent heterogeneity of vascular beds between tissues, future studies are needed to critically evaluate and extend the current findings for other inflammatory contexts, e.g. sterile wounds, autoimmune diseases, in which MSC are being used as a cell therapy. A better understanding of how MSC interact with vascular beds from different tissues will inform strategies to engineer MSC trafficking for therapeutic purposes.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: Extravasation kinetics and distribution of MSC in the inflamed ear

Systemically infused MSC (green) were imaged 2, 4 and 6 h post-infusion in the inflamed ear using intravital confocal microscopy. Blood vessels (red) were visualized using fluorescent dextrans. (A): The extravasation of an individual MSC (white arrowhead) was captured using time-lapse imaging (1 confocal stack/5 min). The stack has been rotated such that the direction of extravasation is parallel to the plane being viewed. Images shown are projections of the stack in the region of interest (blue box). (B): MSC could be seen in capillaries of diameter ≤ cell diameter. One of the cells (1) is intravascular, while the other cell (2) is transmigrating. (C): The percentages of intravascular, transmigrating and extravascular MSC associated with capillaries (vessel diameter <20μm), arterioles and venules were quantified (n=4). Arterioles and venules were differentiated based on blood flow rate and tortuosity of vessels. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test was used (n=4). Values are mean±SD. Asterisks represent p<0.05(*), p<0.01(**) and p<0.001(***); n.s. = not significant.

Supplementary Figure 2: MSC and leukocyte distribution in the inflamed ear is correlated

Systemically infused MSC (green) were imaged 6 h post-infusion in the inflamed ear using intravital confocal microscopy. Blood vessels (red) were visualized using fluorescent dextrans, and endogenous intravascular leukocytes and platelets were visualized using Rhodamine 6G. Representative projections of confocal stacks acquired are shown. Intravascular densities of Rhodamine6G+ cells had a wide range (compare i to ii). Rhodamine6G+ cells were found mainly in venules (v), not arterioles (a) or capillaries (c). Non-adherent leukocytes rolling along arterioles could be seen occasionally (white boxes).

Supplementary Figure 3: MSC adhere to neutrophil extracellular traps in vitro

Neutrophils (blue) were treated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) to generate neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs; green). MSC (red) were incubated with NETs for 5 min, and non-adherent MSC were gently removed before imaging. (A): Representative epifluorescent inverted microscopy images of MSC (white arrowheads) directly adhered to NETs, but not neutrophils. The effect of shear force on NETs often formed NET ‘bridges’ which suspended MSC in solution. Cells in the planes below the MSC can be seen out of focus. (B): Representative confocal image of an MSC (white arrowhead) with a strand of DNA apparently adhered to its surface.

Supplementary Video 1: Detection of NETs in the inflamed ear

Sytox Green (green) was used to detect NETs in the inflamed ear using intravital confocal microscopy. Blood vessels (red) and neutrophils (blue) were visualized using fluorescent dextrans, and an antibody against murine Ly6G, respectively. A representative confocal image stack is shown. Most Sytox-Green structures seemed to be extravascular, not associated with intravascular neutrophils.

Acknowledgements

Some of the materials employed in this work were provided by the Texas A&M Health Science Center College of Medicine Institute for Regenerative Medicine at Scott & White through a grant from NCRR of the NIH, Grant # P40RR017447. This work was also funded in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 grant HL104006 to C.V.C., the NIH grant HL095722 to JMK, a Department of Defense grant # W81XWH-13-1-0305 to J.M.K., the Movember Prostate Cancer Foundation Challenge Award to J.M.K. and NIH grants R01 EB017274, U01 HL100402, and P41 EB015903-02S1 to C.P.L..

The authors would like to thank Luke Mortensen and Clemens Alt for their assistance with in vivo confocal microscopy and helpful discussions. Also, we thank Roberta Martinelli for helpful discussions about NETs, and Rens Zonnefeld, Traci Anderson and Dylan Dupuis for their assistance with in vitro NET assays. Finally, we are grateful to Priya Misir and Caroline Chen for their help with image analysis.

Footnotes

Disclaimers

J.M.K. is a paid consultant of Sanofi, Stempeutics and Mesoblast.

References

- 1.Porada C, Almeida-Porada G. Mesenchymal stem cells as therapeutics and vehicles for gene and drug delivery. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2010;62:1156–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karp JM, Teo GSL. Mesenchymal stem cell homing: the devil is in the details. Cell stem cell. 2009;4:206–216. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henschler R, Deak E, Seifried E. Homing of Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Transfusion medicine and hemotherapy : offizielles Organ der Deutschen Gesellschaft fur Transfusionsmedizin und Immunhamatologie. 2008;35:306–312. doi: 10.1159/000143110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chamberlain G, Fox J, Ashton B, et al. Concise review: mesenchymal stem cells: their phenotype, differentiation capacity, immunological features, and potential for homing. Stem cells (Dayton, Ohio) 2007;25:2739–2749. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song H, Cha M-J, Song B-W, et al. Reactive oxygen species inhibit adhesion of mesenchymal stem cells implanted into ischemic myocardium via interference of focal adhesion complex. Stem cells (Dayton, Ohio) 2010;28:555–563. doi: 10.1002/stem.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu J, Wang D, Liu D, et al. Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell treatment alleviates experimental and clinical Sjögren syndrome. Blood. 2012;120:3142–3151. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-391144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy O, Zhao W, Mortensen L, et al. mRNA-engineered mesenchymal stem cells for targeted delivery of interleukin-10 to sites of inflammation. Blood. 2013 doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-495119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarkar D, Vemula PK, Teo GSL, et al. Chemical Engineering of Mesenchymal Stem Cells to Induce a Cell Rolling Response. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2008;19:2105–2109. doi: 10.1021/bc800345q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sackstein R, Merzaban JS, Cain DW, et al. Ex vivo glycan engineering of CD44 programs human multipotent mesenchymal stromal cell trafficking to bone. Nat Med. 2008;14:181–187. doi: 10.1038/nm1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thankamony SP, Sackstein R. Enforced hematopoietic cell E- and L-selectin ligand (HCELL) expression primes transendothelial migration of human mesenchymal stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018064108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fox J, Chamberlain G, Ashton B, et al. Recent advances into the understanding of mesenchymal stem cell trafficking. British journal of haematology. 2007;137:491–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spaeth E, Klopp A, Dembinski J, et al. Inflammation and tumor microenvironments: defining the migratory itinerary of mesenchymal stem cells. Gene therapy. 2008;15:730–738. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ley K, Laudanna C, Cybulsky MI, et al. Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:678–689. doi: 10.1038/nri2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Semon J, Nagy L, Llamas C, et al. Integrin expression and integrin-mediated adhesion in vitro of human multipotent stromal cells (MSCs) to endothelial cells from various blood vessels. Cell and tissue research. 2010;341:147–158. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-0994-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Segers VFM, Van Riet I, Andries LJ, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell adhesion to cardiac microvascular endothelium: activators and mechanisms. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H1370–1377. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00523.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruster B, Gottig S, Ludwig RJ, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells display coordinated rolling and adhesion behavior on endothelial cells. Blood. 2006;108:3938–3944. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-025098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teo G, Ankrum J, Martinelli R, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells transmigrate between and directly through tumor necrosis factor-α-activated endothelial cells via both leukocyte-like and novel mechanisms. Stem cells (Dayton, Ohio) 2012;30:2472–2486. doi: 10.1002/stem.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith H, Whittal C, Weksler B, et al. Chemokines stimulate bi-directional migration of human mesenchymal stem cells across bone marrow endothelial cells. Stem Cells and Development. 2011 doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langer HF, Stellos K, Steingen C, et al. Platelet derived bFGF mediates vascular integrative mechanisms of mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2009;47:315–325. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Labelle M, Hynes R. The Initial Hours of Metastasis: The Importance of Cooperative Host-Tumor Cell Interactions during Hematogenous Dissemination. Cancer discovery. 2012;2:1091–1099. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarkar D, Ankrum J, Teo G, et al. Cellular and extracellular programming of cell fate through engineered intracrine-, paracrine-, and endocrine-like mechanisms. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3053–3061. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mortensen LJ, Levy O, Phillips JP, et al. Quantification of Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC) Delivery to a Target Site Using In Vivo Confocal Microscopy. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e78145. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Veilleux I, Spencer JA, Biss DP, et al. In Vivo Cell Tracking With Video Rate Multimodality Laser Scanning Microscopy. Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics, IEEE Journal of. 2008;14:10–18. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen M, Whisler J, Jeon J, et al. MECHANISMS OF TUMOR CELL EXTRAVASATION IN AN IN VITRO MICROVASCULAR NETWORK PLATFORM. Integr Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1039/c3ib40149a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Granger D, Senchenkova E. Leukocyte-Endothelial Cell Adhesion. Inflammation and the Microcirculation: Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences. 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fischer U, Harting M, Jimenez F, et al. Pulmonary passage is a major obstacle for intravenous stem cell delivery: the pulmonary first-pass effect. Stem cells and development. 2009;18:683–692. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egawa G, Nakamizo S, Natsuaki Y, et al. Intravital analysis of vascular permeability in mice using two-photon microscopy. Scientific reports. 2013;3:1932. doi: 10.1038/srep01932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Majno G, Palade G. Studies on inflammation. 1. The effect of histamine and serotonin on vascular permeability: an electron microscopic study. The Journal of biophysical and biochemical cytology. 1961;11:571–605. doi: 10.1083/jcb.11.3.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Svensjö E, Arfors K. Dimensions of postcapillary venules sensitive to bradykinin and histamine-induced leakage of macromolecules. Upsala journal of medical sciences. 1979;84:47–60. doi: 10.3109/03009737909179139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bienvenu K, Russell J, Granger D. Leukotriene B4 mediates shear rate-dependent leukocyte adhesion in mesenteric venules. Circulation research. 1992;71:906–911. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.4.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim L, Solito E, Russo-Marie F, et al. Promoting detachment of neutrophils adherent to murine postcapillary venules to control inflammation: effect of lipocortin 1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:14535–14539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thiele J, Goerendt K, Stark G, et al. Real-time digital imaging of leukocyte-endothelial interaction in ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) of the rat cremaster muscle. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2012 doi: 10.3791/3973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warnock R, Askari S, Butcher E, et al. Molecular mechanisms of lymphocyte homing to peripheral lymph nodes. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1998;187:205–216. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.2.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sadik C, Kim N, Luster A. Neutrophils cascading their way to inflammation. Trends in immunology. 2011;32:452–460. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang L, Song X, Liu P, et al. Platelet-mediated Mesenchymal Stem Cells Homing to the Lung Reduces Monocrotalineinduced Rat Pulmonary Hypertension. Cell transplantation. 2012 doi: 10.3727/096368912X640529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Polanowska-Grabowska R, Wallace K, Field JJ, et al. P-Selectin–Mediated Platelet-Neutrophil Aggregate Formation Activates Neutrophils in Mouse and Human Sickle Cell Disease. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2010;30:2392–2399. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.211615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.da Costa Martins P, van den Berk N, Ulfman LH, et al. Platelet-Monocyte Complexes Support Monocyte Adhesion to Endothelium by Enhancing Secondary Tethering and Cluster Formation. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2004;24:193–199. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000106320.40933.E5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brinkmann V, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil extracellular traps: is immunity the second function of chromatin? The Journal of cell biology. 2012;198:773–783. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201203170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Demers M, Wagner D. Neutrophil extracellular traps: A new link to cancer-associated thrombosis and potential implications for tumor progression. Oncoimmunology. 2013:2. doi: 10.4161/onci.22946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cools-Lartigue J, Spicer J, McDonald B, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps sequester circulating tumor cells and promote metastasis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013 doi: 10.1172/JCI67484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McDonald B, Urrutia R, Yipp B, et al. Intravascular neutrophil extracellular traps capture bacteria from the bloodstream during sepsis. Cell host & microbe. 2012;12:324–333. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caudrillier A, Kessenbrock K, Gilliss B, et al. Platelets induce neutrophil extracellular traps in transfusion-related acute lung injury. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2012;122:2661–2671. doi: 10.1172/JCI61303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clark S, Ma A, Tavener S, et al. Platelet TLR4 activates neutrophil extracellular traps to ensnare bacteria in septic blood. Nature medicine. 2007;13:463–469. doi: 10.1038/nm1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boilard E, Nigrovic PA, Larabee K, et al. Platelets amplify inflammation in arthritis via collagen-dependent microparticle production. Science. 2010;327:580–583. doi: 10.1126/science.1181928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Camerer E, Regard J, Cornelissen I, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate in the plasma compartment regulates basal and inflammation-induced vascular leak in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2009;119:1871–1879. doi: 10.1172/JCI38575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang L, Dudek S. Regulation of vascular permeability by sphingosine 1-phosphate. Microvascular research. 2009;77:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bianco P, Robey P, Simmons P. Mesenchymal stem cells: revisiting history, concepts, and assays. Cell stem cell. 2008;2:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bianco P, Cao X, Frenette P, et al. The meaning, the sense and the significance: translating the science of mesenchymal stem cells into medicine. Nature medicine. 2013;19:35–42. doi: 10.1038/nm.3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chiesa S, Morbelli S, Morando S, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells impair in vivo T-cell priming by dendritic cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:17384–17389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103650108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gao Z, Zhang L, Hu J, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells: a potential targeted-delivery vehicle for anti-cancer drug, loaded nanoparticles. Nanomedicine : nanotechnology, biology, and medicine. 2013;9:174–184. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Studeny M, Marini F, Dembinski J, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells: potential precursors for tumor stroma and targeted-delivery vehicles for anticancer agents. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2004;96:1593–1603. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Doyle N, Bhagwan S, Meek B, et al. Neutrophil margination, sequestration, and emigration in the lungs of L-selectin-deficient mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1997;99:526–533. doi: 10.1172/JCI119189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee RH, Hsu SC, Munoz J, et al. A subset of human rapidly self-renewing marrow stromal cells preferentially engraft in mice. Blood. 2006;107:2153–2161. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wynn RF, Hart CA, Corradi-Perini C, et al. A small proportion of mesenchymal stem cells strongly expresses functionally active CXCR4 receptor capable of promoting migration to bone marrow. Blood. 2004;104:2643–2645. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aird W. Phenotypic heterogeneity of the endothelium: II. Representative vascular beds. Circulation research. 2007;100:174–190. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000255690.03436.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li X, Ling W, Khan S, et al. Therapeutic effects of intrabone and systemic mesenchymal stem cell cytotherapy on myeloma bone disease and tumor growth. Bone and Mineral Research. 2012 doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schwarz S, Huss R, Schulz-Siegmund M. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells migrate to healthy and damaged salivary glands following stem cell infusion. International Journal of Oral Science. 2014 doi: 10.1038/ijos.2014.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Randolph G, Angeli V, Swartz M. Dendritic-cell trafficking to lymph nodes through lymphatic vessels. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2005 doi: 10.1038/nri1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johnson LA, Clasper S, Holt AP, et al. An inflammation-induced mechanism for leukocyte transmigration across lymphatic vessel endothelium. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2006;203:2763–2777. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Johnson L, Jackson D. Cell traffic and the lymphatic endothelium. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008 doi: 10.1196/annals.1413.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pflicke H, Sixt M. Preformed portals facilitate dendritic cell entry into afferent lymphatic vessels. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2009;206:2925–2935. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nieswandt B, Hafner M, Echtenacher B, et al. Lysis of tumor cells by natural killer cells in mice is impeded by platelets. Cancer research. 1999;59:1295–1300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Janowska-Wieczorek A, Majka M, Kijowski J, et al. Platelet-derived microparticles bind to hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells and enhance their engraftment. Blood. 2001;98:3143–3149. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.10.3143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ren G, Zhao X, Zhang L, et al. Inflammatory cytokine-induced intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 in mesenchymal stem cells are critical for immunosuppression. Journal of immunology. 2010;184:2321–2328. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vestweber D. Relevance of endothelial junctions in leukocyte extravasation and vascular permeability. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2012;1257:184–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carman C, Springer T. A transmigratory cup in leukocyte diapedesis both through individual vascular endothelial cells and between them. The Journal of cell biology. 2004;167:377–388. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schulte D, Küppers V, Dartsch N, et al. Stabilizing the VE-cadherin-catenin complex blocks leukocyte extravasation and vascular permeability. The EMBO journal. 2011;30:4157–4170. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim M-H, Curry F-RE, Simon S. Dynamics of neutrophil extravasation and vascular permeability are uncoupled during aseptic cutaneous wounding. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2009;296:56. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00520.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sürder D, Manka R, Lo Cicero V, et al. Intracoronary Injection of Bone Marrow Derived Mononuclear Cells, Early or Late after Acute Myocardial Infarction: Effects on Global Left Ventricular Function Four months results of the SWISS-AMI trial. Circulation. 2013 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.001035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zeuner A, Signore M, Martinetti D, et al. Chemotherapy-Induced Thrombocytopenia Derives from the Selective Death of Megakaryocyte Progenitors and Can Be Rescued by Stem Cell Factor. Cancer Research. 2007;67:4767–4773. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Extravasation kinetics and distribution of MSC in the inflamed ear

Systemically infused MSC (green) were imaged 2, 4 and 6 h post-infusion in the inflamed ear using intravital confocal microscopy. Blood vessels (red) were visualized using fluorescent dextrans. (A): The extravasation of an individual MSC (white arrowhead) was captured using time-lapse imaging (1 confocal stack/5 min). The stack has been rotated such that the direction of extravasation is parallel to the plane being viewed. Images shown are projections of the stack in the region of interest (blue box). (B): MSC could be seen in capillaries of diameter ≤ cell diameter. One of the cells (1) is intravascular, while the other cell (2) is transmigrating. (C): The percentages of intravascular, transmigrating and extravascular MSC associated with capillaries (vessel diameter <20μm), arterioles and venules were quantified (n=4). Arterioles and venules were differentiated based on blood flow rate and tortuosity of vessels. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test was used (n=4). Values are mean±SD. Asterisks represent p<0.05(*), p<0.01(**) and p<0.001(***); n.s. = not significant.

Supplementary Figure 2: MSC and leukocyte distribution in the inflamed ear is correlated

Systemically infused MSC (green) were imaged 6 h post-infusion in the inflamed ear using intravital confocal microscopy. Blood vessels (red) were visualized using fluorescent dextrans, and endogenous intravascular leukocytes and platelets were visualized using Rhodamine 6G. Representative projections of confocal stacks acquired are shown. Intravascular densities of Rhodamine6G+ cells had a wide range (compare i to ii). Rhodamine6G+ cells were found mainly in venules (v), not arterioles (a) or capillaries (c). Non-adherent leukocytes rolling along arterioles could be seen occasionally (white boxes).

Supplementary Figure 3: MSC adhere to neutrophil extracellular traps in vitro

Neutrophils (blue) were treated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) to generate neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs; green). MSC (red) were incubated with NETs for 5 min, and non-adherent MSC were gently removed before imaging. (A): Representative epifluorescent inverted microscopy images of MSC (white arrowheads) directly adhered to NETs, but not neutrophils. The effect of shear force on NETs often formed NET ‘bridges’ which suspended MSC in solution. Cells in the planes below the MSC can be seen out of focus. (B): Representative confocal image of an MSC (white arrowhead) with a strand of DNA apparently adhered to its surface.

Supplementary Video 1: Detection of NETs in the inflamed ear

Sytox Green (green) was used to detect NETs in the inflamed ear using intravital confocal microscopy. Blood vessels (red) and neutrophils (blue) were visualized using fluorescent dextrans, and an antibody against murine Ly6G, respectively. A representative confocal image stack is shown. Most Sytox-Green structures seemed to be extravascular, not associated with intravascular neutrophils.