Abstract

Background and aim

The course of disordered gambling in women has been described as “telescoped” compared with that in men, with a later age at initiation of gambling but shorter times from initiation to disorder. This study examined the evidence, for the first time, for such a telescoping effect in a general population rather than a treatment-seeking sample.

Method

Participants in a large community-based Australian twin cohort (2,001 men, 2,662 women) were assessed by structured diagnostic telephone interviews in which they reported the ages at which they had attained various gambling milestones and additional information to be used as covariates (the types of gambling in which they had participated and history of symptoms of alcohol dependence, major depression, and adult antisocial behavior). Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to examine differences between men and women in the time from gambling initiation to the first disordered gambling symptom and a diagnosis of disordered gambling.

Results

Men had a higher hazards than women for the time to the first disordered gambling symptom (HR = 3.13, p < .0001) and to a diagnosis of disordered gambling (HR = 2.53, p < .0001). These differences persisted after controlling for covariates. Earlier age of initiation was the most potent predictor of progression to the first symptom.

Conclusions

When assessed at the general population level, female gamblers do not appear to show a telescoped disordered gambling trajectory compared with male gamblers.

Introduction

Disordered gambling (DG) is a behavioral addiction characterized by “persistent and recurrent maladaptive gambling behavior that disrupts personal, family, and/or vocational pursuits1” (p. 586). Men are about 2–3 times more likely to suffer from a gambling disorder than are women2–3. The course of DG also appears to differ between men and women; men start to gamble and to develop gambling problems at an earlier age than do women on average2,4. Despite the fact that women attain these gambling milestones at a later age than do men, there is evidence to suggest that the time between the onset of gambling and the development of problems is shorter in women than in men1,5. This compressed time window from first use to problems among women has been termed “telescoping”6.

The empirical evidence supporting a “telescoping effect” in the course of DG among women is remarkably consistent6–10. For example, a study of 77 individuals admitted to an outpatient DG treatment program in Brazil found that the ages of gambling initiation were 20 and 34 years, and the ages of DG onset were 33 and 42 years among men and women, respectively6. Another study including 2,256 individuals enrolled in outpatient DG treatment in the state of Iowa found that the ages of gambling initiation were 22 and 30 years, and the ages of DG onset were 36 and 41 years among men and women, respectively7. Finally, a study of 71 individuals enrolled in clinical research trials of pharmacotherapies for DG found that the ages of gambling initiation were 22 and 31 years, and the ages of DG onset were 34 and 39 years among men and women, respectively8. In these three studies, the average time between gambling initiation to the onset of DG was 13 years among men compared to 9 years among women. This accelerated time course of problem gambling development in women compared to men is a clue to potentially distinct etiologic processes involved for the two sexes. Such distinct etiologies might point to alternate targets for prevention and intervention.

However, the previous research is limited in that it was completely based on treatment-seeking samples. This is similar to alcohol use disorder, the diagnosis for which telescoping was originally described and extensively studied. Several researchers have noted that the use of treatment-seeking samples may lead to incorrect conclusions about gender differences in alcohol use disorder progression (e.g.11–12). Until recently, it was thought that women progressed more quickly from alcohol use initiation, to heavy drinking, to alcohol use disorder than did men13. However, a recent example from the alcohol use disorder literature, based on data obtained from over 50,000 participants from two nationally-representative United States surveys, found no evidence that women progressed more rapidly than did men from the onset of drinking to alcohol dependence12. In fact, the opposite was true -- men progressed more rapidly than did women. This prompts the question of whether the phenomenon of telescoping that has been observed in samples of men and women in treatment for DG may need to be revisited in a community-based sample. Much like alcohol use disorder, only a small proportion of individuals affected with a gambling disorder (~10%) ever seek treatment14, rendering treatment-seeking samples unrepresentative of the general population by excluding many of those individuals potentially at risk12.

The purpose of the present study was to examine the phenomenon of telescoping for DG among men and women in a non-treatment-seeking national Australian sample. Because gambling and DG are more common in Australia than they are currently in the United States15–16, Australia provides an optimal setting for studying telescoping for this relatively rare disorder in a community sample. We examined whether there were differences between men and women in the age that they first gambled, the time until they gambled regularly for the first time, the time until they experienced the first symptom of DG, and the time until the first onset of a DG diagnosis. Building on previous research demonstrating that an early age of gambling initiation17–19, type of gambling activity20, and co-occurring psychiatric disorder 18,20–21 are associated with an increased risk of developing DG, we also examined whether these factors would predict a shorter time to the onset of gambling disorder and potentially account for any observed gender differences.

Methods

Participants

Participants for this study were 4,764 members of the Australian Twin Registry (ATR) Cohort II, a national registry of twins born 1964–197115. In 2004–2007, a telephone interview containing an extensive assessment of gambling involvement, including the ages of attaining major gambling-related milestones, and related psychiatric disorders was conducted with the ATR Cohort II members (individual response rate of 80.4%). The mean age was 37.7 years (range = 32–43) and 57.2% of the sample was female. Of the 4,764 participants, 2.1% (n = 101) were lifetime abstainers from gambling. These individuals were not included in this study, leaving a final sample size of 4,663 (2,001 men, 2,662 women). The 4,663 participants came from 2,832 families (1,831 twin pairs and 1,001 single twins). Because community-based samples of twins are typically no different from singletons on a range of traits22, including gambling involvement23, there is no reason to believe that the findings of this study cannot be generalized to the larger population of non-twins.

Procedure

Participants were assessed by a structured telephone interview that had a mean duration of 50 minutes (SD = 10.76). Interviews were administered by trained lay-interviewers under the supervision of a clinical psychologist with over ten years of experience (DJS). All interviews were tape-recorded and a random sample of 5% of the interview tapes was reviewed for quality control and coding inconsistencies. A small sub-sample (n = 166) of the participants were re-interviewed 3.4 months (SD=1.4, range=1.2–9.5) after the initial interview to establish the test-retest reliability of the measures. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Missouri and the Queensland Institute of Medical Research. All of the participants provided informed consent.

Measures

Gambling initiation

Participants were asked how old they were the first time that they had engaged in 11 different gambling activities. The most common first gambling activities were purchasing lottery tickets or scratchcards, playing electronic gambling machines, or betting on horse or dog races24. The earliest reported age was coded as the age first gambled. The test-retest reliability of the age first gambled was very good (r =.75. p < .0001).

Weekly gambling initiation

After responding to an extensive set of questions about involvement in 11 specific gambling activities25, participants were instructed that “For the remaining questions, when I refer to “gambling,” I am talking about any of the different activities that we have been discussing,” and were subsequently asked whether they had ever gambled at least once a week for at least six months in a row (in any gambling activity), and how old they were the first time that had occurred. The test-retest reliability of the age first gambled weekly was very good (r =.78, p < .0001).

Disordered gambling onset

Lifetime symptoms of DG were assessed using the National Opinion Research Center DSM-IV Screen for Gambling Problems26. The age of onset was assessed for each symptom endorsed. Omitting one symptom (gambling-related legal problems) and lowering the diagnostic threshold from 5 to 4 symptoms yielded diagnoses consistent with the DSM-5. A broad diagnosis of DG was based on experiencing at least four lifetime symptoms, and the age of onset of DG was the age at which the fourth symptom first occurred (similar to the approach used in27). The test-retest reliabilities of reporting at least one DG symptom (κ = .79; r =.95, p < .0001) and a DG diagnosis (κ = .75; r =.95, p < .0001) were very good. The test-retest reliability of the age of DG onset was also very good (r =.76, p < .0001). Of the 131 individuals that qualified for the broad DSM-5 DG diagnosis, 20 (15%; 9 men, 11 women) had received either professional treatment for their gambling problems or attended at least one Gamblers’ Anonymous meeting. Unfortunately, the number of individuals that had sought treatment was too small to conduct separate analyses restricted to this subsample for comparison with the prior studies based on treatment-seeking samples.

Type of gambling activity

Involvement in each of the 11 different gambling activities for the 12-month period of maximal gambling involvement was assessed and a summary score of gambling versatility (a count of the 11 different activities) based on this assessment was also derived. (See online Supplemental Materials for details.)

History of psychiatric disorder

The interview also included screening assessments of DSM-IV lifetime diagnoses of alcohol dependence, major depression, and adult antisocial behavior (the adult criterion for antisocial personality disorder). The three-month test-retest reliabilities of these assessments were good (κ = 0.53–0.70). (See online Supplemental Materials for details.)

Data Analysis

Analyses were conducted using Cox proportional hazard models28. In these models, data from individuals without DG are not treated as unaffected, instead they are treated as censored observations. That is, some of the individuals currently unaffected may eventually develop DG, and this is accounted for in the analyses. Because the hazard models were based on data obtained from twins, frailty models were employed using the PROC PHREG procedure in SAS 9.329. These models handle the dependence in the twin pair data by including a random intercept. The time to the age of gambling initiation was modeled, as well as the time from gambling initiation to weekly gambling (among those who had ever gambled weekly), the time from gambling initiation to the first DG symptom (among those who had ever experienced a symptom of DG) and the time from gambling initiation to the onset of a DG diagnosis (among those who met the diagnostic criteria for DG).

The main results of interest were the survival plots for men versus women and their associated hazard ratios. The survival plots show the cumulative proportion of men versus women that have reached a particular gambling milestone as a function of time. A hazard is the probability of an event, such as first meeting the diagnostic criteria for DG, occurring within a year given that DG onset has not yet occurred. Because gender was coded 0=female, 1=male, the hazard ratios were the ratios of the hazard rates among men to the hazard rates among women for each of the gambling milestones. For example, a hazard ratio significantly less than one indicated that for any given time point, women were more likely to have transitioned to a DG diagnosis than men, and would be evidence consistent with a telescoping of the time to DG onset occurring among women relative to men. A key assumption of the Cox proportional hazard model is proportional hazards. This assumption was tested by including interactions between predictors and survival time in the models. A significant interaction provided evidence that the predictor was not proportional and that the assumption was not met. This assumption was met for all but one the models.

Following the unadjusted Cox proportional hazards models, covariate-adjusted models were fit to probe any gender differences uncovered in the hazards of progressing to DG symptoms and diagnosis. These models included three additional sets of explanatory variables (“covariates”): age of gambling onset, type of gambling involvement during the period of heaviest gambling, and lifetime history of comorbid psychiatric disorder (alcohol dependence, major depression, and adult antisocial behavior). (See online Supplemental Materials for more details.)

Results

The mean age of gambling onset was 17.8 (SD = 4.1). Thirty-seven percent of the participants had gambled weekly (40% of men, 35% of women), 12.8% of the participants had experienced at least one symptom of DG (18.5% of men, 8.5% of women), and 2.8% (4.3% of men, 1.7% of women) qualified for the broad DSM-5 DG diagnosis. The majority of those who qualified for the broad diagnosis of lifetime DSM-5 DG (84%) reported a 12-month period of symptom clustering. For all four of the gambling milestones examined, men had an earlier age of onset than did women (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean ages and latencies of attaining gambling milestones for men and women.

| Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | |

| Age first gambled (n = 4,663) | 17.23 | 17.06, 17.40 | 18.26 | 18.08, 18.44 |

| Age first weekly gambling (n = 1,714) | 24.68 | 24.20, 25.16 | 26.09 | 25.66, 26.51 |

| Age first DG symptom (n = 589) | 24.56 | 23.87, 25.26 | 28.09 | 27.27, 28.91 |

| Age of DG onset (n = 128) | 27.16 | 25.79, 28.54 | 30.35 | 28.91, 31.78 |

| Time to weekly gambling (n = 1,714) | 8.11 | 7.63, 8.58 | 8.55 | 8.10, 9.00 |

| Time to first DG symptom (n = 589) | 8.34 | 7.65, 9.04 | 10.91 | 9.94, 11.87 |

| Time to DG onset (n = 128) | ||||

| …from gambling initiation | 10.87 | 9.42, 12.32 | 12.93 | 11.09, 14.77 |

| …from first DG symptom | 4.07 | 3.13, 5.01 | 3.23 | 1.79, 4.68 |

Note: DG = disordered gambling

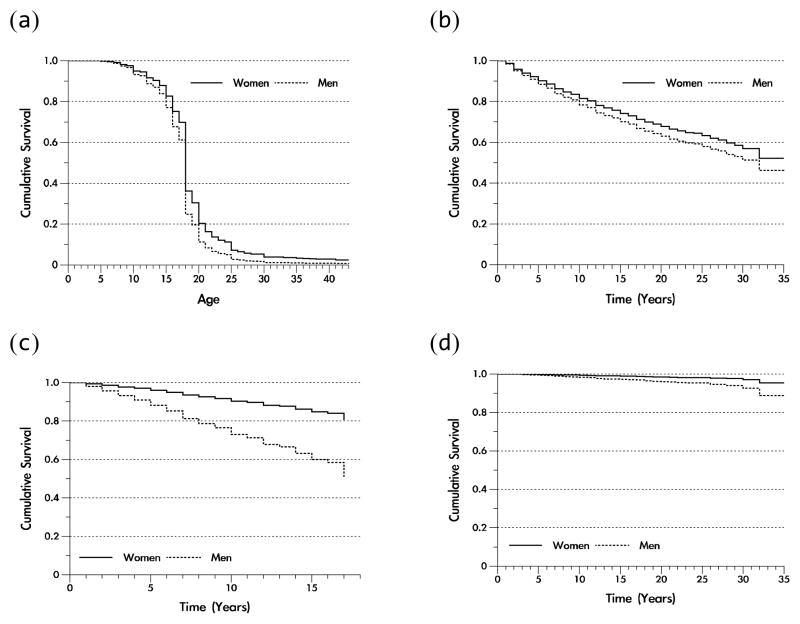

Men initiated gambling at an earlier age and progressed more rapidly to weekly gambling, symptoms of DG, and a DG diagnosis than did women (Table 1). These descriptive results were empirically confirmed in the survival analyses. Men had a higher hazard for initiating gambling and progressing to weekly gambling than women (Table 2, see Figure 1, panels a and b). In the model for the time to the first DG symptom, the proportional hazards assumption was not met (χ2 = 12.03, df=1, p = 0.0005); the differences between the hazards for men and women varied with time. The proportional hazards assumption was met after the sample was divided and analyses were conducted within the subsamples. Men had a significantly higher hazard than women for progressing to DG symptoms when the time from initiating gambling to the first symptom of DG was less than 18 years (Table 2; see Figure 1, panel c); this accounted for 86% of those with a symptom of DG. Among the remaining 14%, the hazard ratio was not significant (Table 2). Men had a higher hazard than women for progressing to a DG diagnosis when the time to a DG diagnosis was measured from the age of first initiating gambling (Table 2; see Figure 1, panel d); when the time to a DG diagnosis was measured from the age of the first DG symptom, there was not a significant difference between men and women (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cox proportional hazards regression model results of gender differences in the course of gambling involvement and disorder

| Effect of gender (men compared to women) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | p | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | |

| Age at initiation of gambling (n = 4,663) | 111.86 | < .0001 | 1.37 | 1.29, 1.46 |

| Time to weekly gambling (n = 1,714) | 10.42 | .001 | 1.17 | 1.06, 1.29 |

| Time to first disordered gambling symptom | ||||

| …when time < 18 years (n = 505) | 140.84 | < .0001 | 3.13 | 2.59, 3.78 |

| …when time ≥18 years (n = 84) | 0.01 | .91 | 1.03 | 0.66, 1.59 |

| Time to disordered gambling onset | ||||

| …from gambling initiation (n = 128) | 25.59 | < .0001 | 2.53 | 1.75 3.66 |

| …from first DG symptom (n = 128) | 0.05 | .82 | 1.05 | 0.07, 1.54 |

Note: Effects are age-adjusted. The ns in parentheses represent the number of events in each of the survival analyses. χ2 tests have 1 degree of freedom.

Figure 1. Cumulative survival curves for four different gambling milestones representing.

(a) the age of gambling initiation in women versus men

(b) the time from gambling initiation until gambling at least once a week in women versus men

(c) the time from gambling initiation until the first symptom of disordered gambling in women versus men (among individuals whose time from gambling initiation to the first disordered gambling symptom was less than 18 years)

(d) the time from gambling initiation until the first onset of disordered gambling in women versus men.

Age was included as a covariate in all of the Cox proportional hazards models.

The higher hazard for men compared to women for progressing to symptoms of DG and a diagnosis of DG (from the age of first initiating gambling) persisted even after including additional covariates in the models (Table 3). Early age of gambling initiation and having a history of adult antisocial behavior substantially contributed to the gender difference in progressing to the first DG symptom. Inclusion of the covariates did not result in a substantial reduction in the gender difference in the progression to a DG diagnosis (see Supplemental Materials).

Table 3.

Unadjusted and covariate-adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression model results of gender differences in the course of gambling symptoms and disorder

| Gambling Outcome | ||

|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Time to first disordered gambling symptoma | Time to disordered gambling onset |

| Unadjusted model results (from Table 2) | ||

| Genderb | 3.13 [2.59, 3.78] | 2.53 [1.75, 3.66] |

| Adjusted model results | ||

| Gender | 1.94 [1.57, 2.41] | 2.30 [1.55, 3.42] |

| Age | 1.24 [1.19, 1.28] | 0.96 [0.88, 1.03] |

| Early gambling initiation | 4.25 [3.44, 5.24] | 0.89 [0.61, 1.30] |

| Electronic gambling machines | 1.48 [1.07, 2.04] | 3.17 [1.66, 6.06] |

| Casino table games | 1.40 [1.01, 1.94] | 1.45 [0.79, 2.69] |

| Bingo | 1.67 [1.09, 2.54] | 3.24 [1.50, 6.99] |

| Alcohol dependence | 1.62 [1.29, 2.04] | 3.07 [2.08, 4.53] |

| Major depression | 1.68 [1.38, 2.05] | 2.37 [1.61, 3.48] |

| Adult antisocial behavior | 1.36 [1.10, 1.69] | 2.03 [1.34, 3.06] |

Note: Cell entries are hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals in brackets. Adjusted results are from models that included the predictors listed above as well as nine other forms of gambling and gambling versatility. Only significant predictors are shown (the other predictors were not statistically significant). See online supplemental materials for more details and the full model results.

= includes the 86% of participants who experienced their first disordered gambling symptom within 18 years of initiating gambling,

= estimate is age-adjusted.

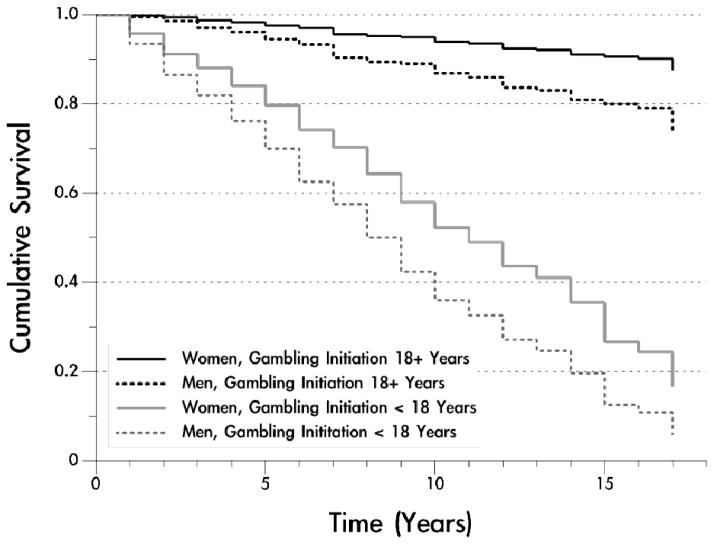

In addition to explaining gender differences, the inclusion of the covariates also revealed that: (a) those who initiated gambling before age 18 had a higher hazard for progressing to DG symptoms than those who initiated gambling at age 18 and later (see Figure 2), (b) those who participated in electronic gambling machines, casino table games, and bingo during the period of maximal gambling involvement had a higher hazard for progressing to DG symptoms than those who did not (electronic gambling machines and bingo were also associated with progression to a DG diagnosis), and (c) those with a lifetime history of alcohol dependence, major depression, and adult antisocial behavior had a higher hazard for progressing to DG symptoms and disorder than those who did not. All possible gender by covariate interactions were tested, but none were statistically significant and are therefore not reported. Failure to observe any gender interactions suggests that the aforementioned covariates affect the risk for progressing to disordered gambling symptoms and diagnosis similarly in men and women.

Figure 2.

Cumulative survival curves representing the time from gambling initiation until the first symptom of disordered gambling as a function of sex and early age of gambling initiation (among individuals whose time from gambling initiation to the first disordered gambling symptom was less than 18 years). There was not a significant interaction between gender and early gambling initiation in predicting the onset of the first disordered gambling symptom (χ2 = 1.72, df = 1, p = 0.19), and the hazards significantly differed for men and women with both an earlier (HR = 1.57, 95% CI = 1.16 – 2.13) and later (HR = 2.45, 95% CI = 1.89 – 3.17) age of gambling initiation. Age was included as a covariate in the two Cox proportional hazards models used to derive these survival curves.

Discussion

This represents the first community-based study to examine the question of whether DG trajectories are telescoped in women compared to men. The age of gambling initiation was earlier, and the time to the progression to weekly gambling, symptoms of DG, and the onset of a DG diagnosis were shorter among men compared to women. The only exception to this pattern was when the time to the onset of a DG diagnosis was measured from the time of the first disordered gambling symptom, there was no difference between men and women. This suggests that once problems are set in motion, there is no longer a gender difference in the rate of progression to disorder.

These findings stand in sharp contrast to the five previous studies based on individuals seeking treatment for DG that all found that the time from the age of gambling onset to DG was shorter among women than among men. The telescoping phenomenon previously observed rests on the idea that women start to gamble later than do men, but that they eventually start to “catch up” to men by taking less time to develop a gambling disorder. The ages of gambling initiation reported in the previous studies of 20–22 years among men and 30–34 years of age among women are quite discrepant from the ages of 17 and 18 years among men and women in the present study. A recent study demonstrating that the ages of gambling onset in men and women have been converging in more recent United States birth cohorts4 may provide one possible explanation for this discrepancy. In the cohort born around the same time as the participants in the previous studies, the ages of gambling initiation were about 23 and 29 years among men and women, respectively. In the cohort born around the same time as the participants in the present study, the ages of gambling initiation were about 19 and 23 years among men and women, respectively. In the most recently born United States birth cohort included in the previous survey, the ages of gambling initiation were about 16 and 19 years among men and women, respectively, which are similar to the ages among the Australian participants in the present study. This suggests that not only are the ages of gambling onset converging in men and women, but they may also be converging in the United States compared to Australia. The convergence of the age of gambling initiation in men and women4 will result in a diminution of any telescoping effect. As the age at which women take up gambling approaches the age at which men do, the time window within which to “catch up” is shortened, especially given the robust finding that men tend to have an earlier age of DG onset than do women.

Another likely explanation for the discrepant findings may rest with differences in the men and women who are found in DG treatment samples. For example, both men and women who seek treatment have more severe disorder than those who do not seek treatment, and men with DG are less likely to seek treatment than are women with DG30. As a consequence of the different forces leading men and women into treatment, there may also be differences in the ages of gambling initiation and DG onset that would not be observed among men and women with DG in the general community. It is difficult to draw inferences about the course of DG in the general population from an unrepresentative 10% of individuals with DG.

The results of this study provide several clues to the underlying reasons for why men progress more rapidly to DG than do women. Of the three characteristics that were proposed as predicting a shorter time to disordered gambling, two of them -- early age of gambling initiation, and co-occurring psychiatric disorder – also partially explained the gender difference. Men initiated gambling earlier than did women, and this earlier age of gambling initiation was related to a shorter time to symptoms of DG and accounted for some of the difference between men and women in their DG trajectory. Perhaps not surprisingly, men were more likely to have a history of antisocial behavior disorder, and having a history of this disorder was related to a shorter time to symptoms of DG and a diagnosis of DG, and accounted for some of the difference between men and women in their DG trajectory. These predictors of disordered gambling progression explained some, but not all of the gender difference. The type of gambling activity in which one was involved, particularly electronic machine gambling, was more common among men than women, and was related to a shorter time to symptoms of DG and a diagnosis of DG, but did not explain the gender difference. Further elucidation of the mechanisms behind the more rapid progression to DG among men than women is an important topic for future community-based gambling research.

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. First, the ages of onset of gambling, weekly gambling, and DG were based on retrospective reports. Unlike the previous studies on telescoping in DG, however, we were able to provide evidence that these reports were moderately reliable. Second, the majority of the participants were Caucasians of Northern European ancestry, so it is not clear the extent to which these results will apply to other racial groups. Third, it is unclear how the results of this Australian study will generalize to other countries. This limitation is offset by the advantage of exploring the trajectory of DG development in a community-based sample that had adequate numbers of at-risk and affected individuals. Fourth, the participants were relatively young; later onsets of DG may not have been represented. This concern is mitigated by the use of the data analytic technique of survival analysis that treats individuals without DG as censored, rather than unaffected per se.

Conclusions

The findings were unambiguous in showing no evidence consistent with a telescoped DG trajectory in women compared to men. The results of this study align neatly with the alcohol use disorder literature in demonstrating that the telescoping effect observed in treatment-seeking samples is not found in samples of individuals from the community.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grant MH66206. We thank Bronwyn Morris and Megan Fergusson for coordinating the data collection for the twins, and David Smyth, Olivia Zheng, and Harry Beeby for data management of the Australian Twin Registry. We thank the Australian Twin Registry twins for their continued participation.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanco C, Hasin DS, Petry N, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Sex differences in subclinical and DSM-IV pathological gambling: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2006;36(7):943–953. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wardle H, Moody A, Spence S, Orford J, Volberg R, Jotangia D, Griffiths M, Hussey D, Dobbie F. British Gambling Prevalence Survey 2010. London: National Centre for Social Research; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richmond-Rakerd LS, Slutske WS, Piasecki TM. Birth cohort and sex differences in the age of gambling initiation in the United States: Evidence from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. International Gambling Studies. 2013;13(3):417–429. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant JE, Kim SW. Gender differences. In: Grant JR, Potenza MN, editors. Pathological Gambling: A Clinical Guide to Treatment. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tavares H, Zilberman ML, Beites FJ, Gentil V. Gender differences in gambling progression. J Gambl Stud. 2001;17(2):151–159. doi: 10.1023/a:1016620513381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson SE, LaPlante DA, LaBrie RA, Schaffer HJ. The proxy effect: Gender and gambling problem trajectories of Iowa gambling treatment participants. J Gambl Stud. 2006;22(2):221–240. doi: 10.1007/s10899-006-9012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Mooney ME. Telescoping phenomenon in pathological gambling: Association with gender and comorbidities. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012;200(11):996–8. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182718a4d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ladd GT, Petry NM. Gender differences among pathological gamblers seeking treatment. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;10(3):302–309. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.10.3.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Potenza MN, Steinberg MA, McLaughlin SD, Wu R, Rounsaville BJ, O’Malley SS. Gender-related differences in the characteristics of problem gamblers using a gambling helpline. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(9):1500–1505. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hussong A, Bauer D, Chassin L. Telescoped trajectories from alcohol initiation to disorder in children of alcoholic parents. J Abnorm Psychol. 2008;117(1):63–78. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keyes KM, Martins SS, Blanco C, Hasin DS. Telescoping and gender differences in alcohol dependence: New evidence from two national surveys. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(8):969–76. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stewart SH, Gavric D, Collins P. Women, girls, and alcohol. In: Brady KT, Back SE, Greenfield SF, editors. Women and Addiction: A Comprehensive Handbook. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slutske WS. Natural recovery and treatment-seeking in pathological gambling: Results of two US national surveys. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(2):297–302. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slutske WS, Meier MH, Zhu G, Statham DJ, Blaszczynski A, Martin NG. The Australian twin study of gambling (OZ-GAM): Rationale, sample description, predictors of participation, and a first look at sources of individual differences in gambling involvement. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2009;12(1):63–78. doi: 10.1375/twin.12.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slutske WS, Zhu G, Meier MH, Martin NG. Genetic and environmental influences on disordered gambling in men and women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):624–630. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lynch WJ, Maciejewski PK, Potenza MN. Psychiatric correlates of gambling in adolescents and young adults grouped by age at gambling onset. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(11):1116–22. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessler RC, Hwang I, LaBrie R, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Winters KC, et al. The prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV pathological gambling in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol Med. 2008;38(9):1351–60. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slutske WS, Deutsch AR, Richmond-Rakerd LS, Chernyavskiy P, Statham DJ, Martin NG. Test of a potential causal influence of earlier age of gambling initiation on gambling involvement and disorder: A multi-level discordant twin design. Psychol Addict Behav. 2014 doi: 10.1037/a0035356. eonline ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hodgins DC, Schopflocher DP, Martin CR, el-Guebaly N, Casey DM, Currie SR, Smith GJ, Williams RJ. Disordered gambling among higher-frequency gamblers: Who is at risk? Psychol Med. 2012;42(11):2433–2444. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petry NM, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Comorbidity of DSM-IV pathological gambling and other psychiatric disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(5):564–574. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnes JC, Boutwell BB. A demonstration of the generalizability of twin-based research on antisocial behavior. Behav Genet. 2013;43(2):120–131. doi: 10.1007/s10519-012-9580-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slutske WS, Richmond-Rakerd LS. A closer look at the evidence for sex differences in the genetic and environmental influences on gambling in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: From disordered to ordered gambling. Addiction. 2014;109(1):120–127. doi: 10.1111/add.12345. [online supplemental materials] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richmond-Rakerd LS, Slutske WS, Heath AC, Martin NG. Genetic and environmental influences on the ages of drinking and gambling initiation: Evidence for distinct aetiologies and sex differences. Addiction. 2014;109(2):323–331. doi: 10.1111/add.12310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Productivity Commission. Australia’s Gambling Industries, Report No. 10. Canberra, Australia: AusInfo; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerstein D, Murphy S, Toce M, Hoffmann J, Palmer A, Johnson R, et al. Gambling Impact and Behavior Study: Report to the National Gambling Impact Study Commission. Chicago: National Opinion Research Center; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wagner FA, Anthony JC. Male-female differences in the risk of progression from first use to dependence upon cannabis, cocaine, and alcohol. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86(2–3):191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singer JD, Willett JG. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT® 13.1 User’s Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slutske WS, Blaszczynski A, Martin NG. Sex differences in the rates of recovery, treatment-seeking, and natural recovery in pathological gambling: Results from an Australian community-based twin survey. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2009;12(5):425–432. doi: 10.1375/twin.12.5.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.