Abstract

Objective

Although adiposity has been considered protective against hot flashes, newer data suggest positive relations between flashes and adiposity. No studies have been specifically designed to test whether weight loss reduces hot flashes. This pilot study aimed to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and initial efficacy of behavioral weight loss to reduce hot flashes.

Methods

Forty overweight/obese women with hot flashes (≥4/day) were randomized to a behavioral weight loss intervention or to wait list control. Hot flashes were assessed pre- and post-intervention via physiologic monitor, diary, and questionnaire. Comparisons of changes in hot flashes and anthropometrics between conditions were tested via Wilcoxon tests.

Results

Study retention (83%) and intervention satisfaction (93.8%) were high. Most women (74.1%) reported that hot flash reduction was a main motivator to lose weight. Women randomized to the weight loss intervention lost more weight (-8.86 kg) than did women randomized to control (+0.23 kg, p<.0001). Women randomized to weight loss also showed greater reductions in questionnaire-reported hot flashes (2-week hot flashes: −63.0) than did women in the control (−28.0, p=.03), a difference not demonstrated in other hot flash measures. Reductions in weight and hot flashes were significantly correlated (e.g., r=.47, p=.006).

Conclusions

This pilot study showed a behavioral weight loss program to be feasible, acceptable, and effective in producing weight loss among overweight/obese women with hot flashes. Findings indicate the importance of a larger study designed to test behavioral weight loss for hot flash reduction. Hot flash management could motivate women to engage in this health-promoting behavior.

Keywords: Hot flashes, hot flushes, vasomotor symptoms, weight loss, weight, obesity

Introduction

Hot flashes are a prevalent menopausal symptom, with over 70% of women reporting hot flashes during the menopause transition.1 In many cases, these symptoms are frequent or severe.1–3 Newer data also indicate that hot flashes are persistent, lasting an average of 9 or more years.4 Women with hot flashes are at greater risk of poor quality of life,5 sleep problems,6 and depressed mood7 compared to women without hot flashes. Thus, women frequently seek treatment for their hot flashes, which are a leading driver of gynecologic ambulatory care visits8 and out-of-pocket gynecologic expenditures.9 In light of potential risks associated with hormone therapy,10 the most effective treatment for hot flashes, there is great interest in nonhormonal methods to manage hot flashes, including behavioral approaches.11

One potential behavioral approach to managing hot flashes is weight loss.12 However, the role that body weight has played in the occurrence of hot flashes during the menopause transition has been the subject of debate. Given that adipose tissue is a site of peripheral conversion of androgens to estrogens, body fat was initially theorized to be protective against hot flashes.13 However, more recent epidemiologic investigations challenge this idea, as cross-sectional data indicate that women with higher BMIs and higher body fat report more hot flashes than their leaner counterparts.1 Moreover, longitudinal data indicate that increasing body fat over the menopausal transition is associated with higher subsequent hot flash reporting.14 These data are consistent with a thermoregulatory role of body fat, with adipose tissue insulating against the putative heat dissipating action of hot flashes.15, 16 In addition, data suggest that the relation between adiposity and hot flashes may vary according to menopausal stage. Higher adiposity may act as a risk factor earlier in the menopausal transition, and be protective later in the transition when ovarian estrogen production has ceased.17–19 Thus, the positive association between adiposity and hot flashes may be limited to early in the menopausal transition.

Existing research on adiposity and hot flashes has been largely observational, limiting conclusions about the causal role of body fat in hot flash occurrence. Post-hoc analyses of two existing trials have provided some preliminary suggestion that weight loss may reduce the occurrence or bother associated with hot flashes,20, 21 although findings were mixed and did not provide clear answers to the question of whether weight loss reduces hot flashes.22 Notably, these existing data are derived from secondary analyses of trials not designed to address whether weight loss reduced hot flashes, and thus had important limitations. These include a low representation of women with hot flashes, inclusion of women using medications to reduce hot flashes (e.g., hormone therapy), and assessment of hot flashes via brief retrospective questionnaire instruments. To date, there have been no experimental manipulations specifically designed to test whether weight loss reduces hot flashes. Furthermore, it is unclear whether behavioral weight loss for hot flash reduction would be acceptable to women with hot flashes, and whether reduction of hot flashes would motivate women to engage in this health-promoting behavior.

The primary aim of this pilot study was to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of a behavioral weight loss intervention to reduce hot flashes. Secondarily, we examined the preliminary effect of this weight loss intervention on hot flashes, and particularly whether women in the weight loss group showed greater reductions in hot flashes than women in the control group. Further, in an exploratory fashion, we investigated whether degree of weight change was related to the degree of hot flash change. Finally, we examined whether any weight loss-associated reduction in hot flashes varied by proximity to the final menstrual period (FMP; a proxy for ovarian aging).

Methods

Study participants

Forty overweight or obese (BMI 25–40) women with ≥4 hot flashes/day who wanted to lose weight were recruited from the surrounding community via hospital registries, fliers at local businesses and hospitals, and online message boards. Women were either late perimenopausal (amenorrhea 3 to 12 months) or postmenopausal (amenorrhea ≥12 months). Sample exclusions included hysterectomy/oophorectomy or use of medications known to impact hot flashes and/or weight (hormone therapy, oral contraceptives, gabapentin, SSRI/SNRIs, SERMS, clonidine, antipsychotics, steroids, weight loss medications, chemotherapy). Women also were excluded if they were currently participating in a structured weight loss program, had ever undergone weight loss surgery, or currently reported more than 150 minutes/week of physical activity with a BMI <27.5. All women obtained written medical clearance from their personal physician to participate in a lifestyle weight loss program and provided written, informed consent. Study procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Protocol

Women completed a telephone and subsequent in-person assessment to determine study eligibility. Eligible women underwent baseline hot flash monitoring, measurement of height and weight, Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) assessment of body composition, and questionnaires. Women were next randomly assigned to the weight loss or control arm in approximate blocks of 10. Participants in the experimental condition were invited to attend 20 group sessions delivered weekly over 6 months. The hot flash, height, weight, DXA, and questionnaire assessments were repeated after this 6-month period. The control condition was a wait list control. Women in the control condition underwent assessments at baseline at 6 months, and were invited to attend separate weight loss group sessions after completing all assessments.

Measures

Screening measures included measurement of height and weight, medical history, medication use, and reproductive history, including assessment of menstrual cycles. The approximate date of the last menstrual period was reported.

Anthropometric

Height and weight were measured via a fixed stadiometer (Seca; Hanover, MD) and calibrated balance beam scale (Healthometer; Alsip, IL), respectively. BMI was calculated (kg/m2).

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA)

Body composition was assessed via DXA, a validated measure of body composition.115 Measurements were performed at the University of Pittsburgh Endocrinology & Metabolism Research Center on a Luna r-iDEXA machine with enCORE v.12.30 software (GE Healthcare). Total percentage of body fat was derived from this measurement.

Hot flashes

Hot flashes were measured in three ways: 1) physiologic assessment, 2) electronic diary, and 3) questionnaire.

Physiologic hot flashes

Women were equipped with a physiologic hot flash monitor, the Biolog (UFI, 3991/2-SCL; Morro Bay, CA), which they wore in a pouch around the waist for 24 hours. Skin conductance is sampled at 1 Hz from the sternum via a 0.5 Volt constant voltage circuit passed between two Ag/AgCl electrodes (UFI, Morro Bay, CA) filled with 0.05M KCL Velvachol/glycol paste.23 Physiologic hot flashes were classified via standard methods, with skin conductance rises of ≥2 μmho in 30 seconds24 flagged automatically by UFI software (DPSv3.6; Morro Bay, CA) and edited for artifact.25 As some women show submaximal events failing to reach the 2 μmho criterion,26, 27 all potential hot flashes were visually inspected by hot flash coders, and events showing the characteristic hot flash pattern yet <2 μmho/30 sec rise coded as a hot flash. This coding has been shown to be reliable (κ=.86) in our laboratories.26, 27 A 20-minute lockout period was implemented after the start of hot flash during which no further events were coded.

Diary-reported hot flashes

Women reported their hot flashes at the time of hot flash occurrence in a handheld electronic diary (Palm Z22, Palm, Inc.) for three days, the first of which coincided with physiologic monitoring. Each hot flash was also rated on severity and bother (1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe, 4=very severe). This three-day monitoring period was chosen given prior work indicating that three days of diary yield comparable estimates to a week.28

Questionnaire-assessed hot flashes

For comparability with other investigations,1,16, 17 women were asked to report via questionnaire the frequency of hot flashes over the past two weeks (number of days experiencing hot flashes: 1–5 days, 6–8 days, 9–13 days, or everyday; number of hot flashes/day). The number of hot flashes/day was multiplied by the days experiencing hot flashes to yield the number of hot flashes over two weeks.

Other questionnaires

Women completed a battery of questionnaires, including demographics (e.g., age, race/ethnicity, educational attainment), health behaviors (e.g., smoking, physical activity as assessed by the International Physical Activity Questionnaire,29 and psychosocial factors (e.g., depressive symptoms as assessed by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale30).

Intervention acceptability

After each intervention session, women were asked to rate the session with respect to usefulness (0=not at all-4=very). At the end of the intervention, women were asked how satisfied they were with the program (0=very dissatisfied-4=very satisfied) and the reasons that they joined the study [appearance, hot flash reduction, other health reasons (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, orthopedic), other quality of life reasons (e.g., mood, sleep, energy), advice from health care provider, other]. They also were asked whether the potential to reduce hot flashes with weight loss influenced their motivation to lose weight (0=decreased a lot- 4=increased a lot), and whether their motivation to lose weight during midlife/menopause was different than at other times of life.

Weight Loss Intervention

The intervention was a standard behavioral weight loss intervention that included dietary and physical activity self-monitoring, prescription of moderate calorie reduction, and encouragement of moderate physical activity. Sessions were delivered in 20, 1-hour group sessions (10–14 women/group) over 6 months. Each session included a weigh-in, review of self-monitoring forms with written feedback, and didactics. The intervention is similar to that of Look AHEAD31 and Diabetes Prevention Program32 trials and follows NHLBI Clinical Guidelines for obesity treatment.33 Women were provided with calorie goals based on initial body weight (1200–1800 kcal/day), given physical activity goals (e.g., 100–300 min/wk brisk walking), and instructed on key behavioral strategies such as stimulus control, and self-monitoring of weight, calories. The intervention was additionally tailored to midlife, menopausal women, including addressing issues such as dietary and activity choices in the context of sleep loss; behavior change in the context of family, work, and caretaking demands; and physical activity choices with aging.

Data analysis

All indices were examined for normality, outliers, and smaller cell sizes. To account for variations in monitoring duration, ambulatory-assessed physiologic and diary hot flash indices were standardized to a 24-hour period. To do so, the number of hot flashes (physiologic or diary-reported) were divided by the monitoring duration and multiplied by 24. Diary-reported severity and bother ratings for each hot flash were averaged over the number of hot flashes reported.

Characteristics of women randomized to the experimental vs. control condition as well as completers vs. dropouts were compared via t-tests and chi-square tests. Completers were defined as women who completed the 6-month (post-intervention) follow up assessment. Pre to post-intervention changes in hot flashes, weight, and % body fat were calculated as change scores. Differences in hot flashes and weight change between intervention and control were compared via Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Analyses were conducted for both completers as well as intent to treat, with baseline hot flash values carried forward for missing 6-month follow-up hot flash values. Analyses were conducted in SAS. All tests were two-sided tests at alpha=0.05.

Results

Forty women (25% African American, 75% White) were enrolled. At baseline women had a median (Md) of 8.86 (interquartile range (IQR): 4.99, 13.47) physiologic hot flashes and 6.41 (IQR: 4.93, 9.80) self-reported hot flashes per 24 hours. Their baseline BMI was an average of 32.13 (SD=3.79) and percentage of total body fat 44.84% (SD=4.50). Women randomized to weight loss vs. control were similar on all study characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Weight Loss | Control | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 21 | 19 |

| Age, M (SD) | 55.23 (3.83) | 55.16 (4.58) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White | 18 (85.71) | 12 (63.16) |

| African American | 3 (14.29) | 7 (36.84) |

| Education | ||

| Less than college | 5 (23.81) | 9 (47.37) |

| College or higher | 16 (76.19) | 10 (52.63) |

| Marital status (n, % married/partnered) | 14 (73.68) | 12 (57.14) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||

| Current | 0 (0) | 2 (10.53) |

| Past/never | 21 (100.00) | 17 (89.47) |

| Physical activity, MET hrs/wk, Median (IQR)* | 17.00 (7.40, 28.11) | 15.70 (8.00, 42.60) |

| Menopausal stage, n (%) | ||

| Perimenopausal | 7 (33.33) | 9 (47.37) |

| Postmenopausal | 14 (66.67) | 10 (52.63) |

| Years since FMP, M (SD) | 4.30 (5.40) | 4.49 (6.50) |

| Depression, M (SD) § | 8.57 (9.17) | 10.37 (7.56) |

As assessed by International Physical Activity Questionnaire;

As assessed by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

MET=Metabolic equivalent; FMP=final menstrual period

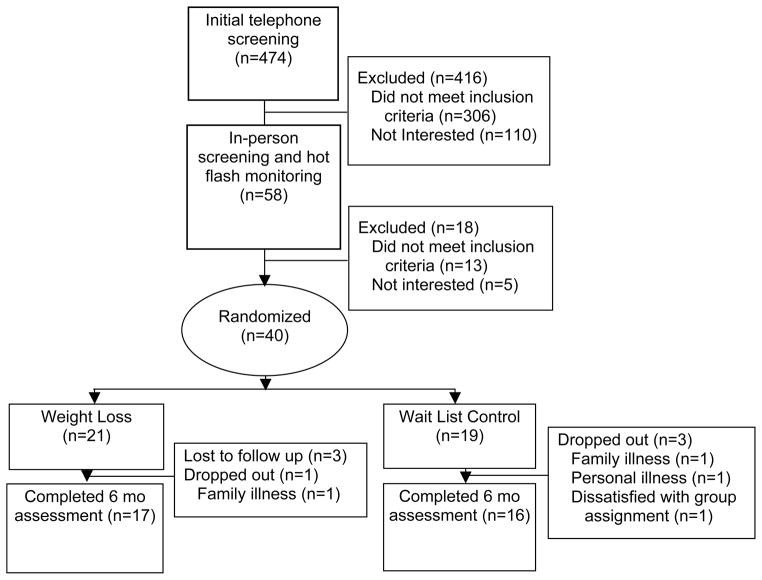

Retention was high and did not differ between groups, with 83% of women completing the study (81.0% in intervention, 84.2% in control; p=1.00, see Figure 1 for study flow chart). Women who completed the study did not differ from women not completing the study on any characteristics with the exception of marginally lower percentage of body fat prior to treatment (completers: 44.5% vs. noncompleters: 47.5%, p=0.07). Women in the intervention group attended a median of 80% (16) of weight loss sessions. On average, women rated the sessions high on usefulness (M=3.76, SD=.25; scale of 0=not at all to 4=very). Women in the intervention group also reported being satisfied (6.3%) or very satisfied (93.8%) with the intervention. Session ratings of usefulness and amount of weight loss were significantly correlated (rho=0.52, p=0.03).

Figure 1.

Study Diagram

Women were asked about the reasons for their participation in this weight loss study. The leading reasons women cited for wanting to lose weight were appearance (81.5%), followed by hot flash reduction (74.1%), and improved quality of life (70.4%). Most of the women (81.5%) indicated that the potential to reduce hot flashes increased their motivation to lose weight (“by a lot” for 51.9% of women). Approximately half (51.9%) of the women indicated that their motivation to lose weight was higher during the menopausal transition than at other times of life.

Women in the intervention lost an average of 8.8 kg (10.7%) and 4.7% body fat from baseline to the 6-month post-intervention assessment (Table 2), with similar yet slightly attenuated changes in intent to treat analyses (7.5 kg; 3.8% body fat change, Table 3). There was little weight or body composition change in the control group. Women in the intervention group also showed some a tendency towards greater reduction in hot flashes than women in the control group. This different was significant in the case of questionnaire-reported hot flashes, yet not diary or monitored hot flash frequency. The amount of weight reduction was correlated with reductions in questionnaire-reported hot flash frequency as well as diary-reported hot flash severity (Table 4).

Table 2.

Hot flashes (HF) and body composition at baseline, follow up, and change from baseline to follow up (completers)

| Weight Loss (N=17) | Control (N=16) | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| median | IQR | median | IQR | ||||

| Baseline | HF/24 hrs | Physiologic (#) | 8.94 | (5.00, 11.92) | 7.52 | (3.39, 14.35) | 0.86 |

| Self report (#) | 7.93 | (5.96, 9.99) | 5.82 | (3.82, 9.47) | 0.30 | ||

| HF/2 wk (#, Questionnaire) | 70.00 | (42.00, 112.00) | 77.00 | (31.50, 112.00) | 0.96 | ||

| HF Severity | 1.26 | (1.11, 1.48) | 1.34 | (1.24, 1.67) | 0.12 | ||

| HF Bother | 1.21 | (1.07, 1.43) | 1.43 | (1.19, 1.68) | 0.07 | ||

| Weight (kg) | 80.00 | (76.36, 92.27) | 85.34 | (79.32, 97.73) | 0.29 | ||

| % fat | 44.50 | (41.20, 47.30) | 43.85 | (41.10, 48.40) | 0.17 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Follow up | HF/24 hrs | Physiologic (#) | 4.99 | (0.98, 10.11) | 8.48 | (1.99, 14.65) | 0.31 |

| Self report (#) | 4.00 | (1.98, 6.33) | 3.90 | (2.01, 6.28) | 0.97 | ||

| HF /2 wk (#, Questionnaire) | 22.00 | (6.00, 42.00) | 56.00 | (28.00, 84.00) | 0.01 | ||

| HF Severity | 1.12 | (1.00, 1.25) | 1.44 | (1.25, 1.79) | <0.001 | ||

| HF Bother | 1.06 | (1.00, 1.18) | 1.34 | (1.27, 1.89) | 0.001 | ||

| Weight (kg) | 70.45 | (67.05, 79.77) | 85.23 | (78.07, 97.73) | 0.01 | ||

| % fat | 40.20 | (32.50, 42.80) | 44.75 | (40.15, 47.80) | 0.03 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Change | HF/24 hrs | Physiologic(#) | −3.79 | (−6.88, 0.01) | 0.00 | (−4.58, 1.53) | 0.24 |

| Physiologic (%) | −43.17 | (−90.51, 0.27) | 0.00 | (−62.14, 40.46) | 0.39 | ||

| Self report (#) | −2.90 | (−5.76, −0.51) | −1.42 | (−4.88, −0.21) | 0.49 | ||

| Self report (%) | −31.39 | (−73.33, −8.53) | −26.18 | (−55.88, −3.38) | 0.47 | ||

| HF/2 wk (#, Questionnaire) | −63.00 | (−70.00, −8.00) | −28.00 | (−42.00, 27.00) | 0.03 | ||

| HF Severity | −0.05 | (−0.37, 0.00) | 0.09 | (−0.16, 0.24) | 0.08 | ||

| HF Bother | −0.05 | (−0.39, 0.06) | 0.01 | (−0.27, 0.20) | 0.24 | ||

| Weight (kg) | −8.86 | (−10.45, −6.36) | 0.23 | (−1.48, 1.70) | <.0001 | ||

| Weight (%) | −10.71 | (−14.01, −7.57) | 0.29 | (−1.61, 1.98) | <.0001 | ||

| % fat | −4.65 | (−7.40, −3.65) | −0.70 | (−1.40, 0.80) | <.0001 | ||

Note: Diary HF bothersome and severity scores ranged from 1–4 and were averaged over the monitoring period. Questionnaire HF frequency was recalled frequency of hot flashes over past two weeks (number HF/day*number of days experiencing HF)

Differences tested via Wilcoxon test

Table 3.

Hot flashes (HF) and body composition at baseline, follow up, and change from baseline to follow up (intent to treat)

| Weight Loss (N=21) | Control (N=19) | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| median | IQR | median | IQR | ||||

| Baseline | HF/24 hrs | Physiologic (#) | 9.90 | 5.09, 13.19 | 6.98 | 2.99, 13.82 | 0.29 |

| Self report (#) | 7.27 | 5.76, 9.99 | 5.65 | 3.35, 8.65 | 0.12 | ||

| HF/2 wk (#, Questionnaire) | 70.00 | 35.00, 112.00 | 70.00 | 15.00, 112.00 | 0.50 | ||

| HF Severity | 1.33 | 1.19, 1.71 | 1.42 | 1.29, 1.89 | 0.42 | ||

| HF Bother | 1.33 | 1.17, 1.71 | 1.53 | 1.20, 1.89 | 0.39 | ||

| Weight (kg) | 82.27 | 76.36, 87.05 | 85.91 | 78.64, 99.09 | 0.18 | ||

| % fat | 44.90 | 41.20, 47.60 | 46.00 | 4.00, 13.00 | 0.53 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Follow up | HF/24 hrs | Physiologic (#) | 6.54 | 2.95, 12.91 | 8.09 | 2.00, 14.45 | 0.98 |

| Self report (#) | 4.85 | 2.66, 6.34 | 4.14 | 2.01, 6.24 | 0.56 | ||

| HF/2 wk (#, Questionnaire) | 22.00 | 6.00, 49.00 | 55.50 | 14.00, 70.00 | 0.13 | ||

| HF Severity | 1.17 | 1.00, 1.38 | 1.42 | 1.27, 1.86 | 0.03 | ||

| HF Bother | 1.17 | 1.00, 1.41 | 1.42 | 1.29, 1.86 | 0.045 | ||

| Weight (kg) | 77.73 | 67.27, 84.55 | 85.45 | 77.05, 97.73 | 0.01 | ||

| % fat | 41.30 | 35.05, 44.50 | 46.00 | 41.00, 48.00 | 0.03 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Change | HF/24 hrs | Physiologic (#) | −1.73 | −5.39, 0.01 | 0.00 | −3.98, 0.97 | 0.31 |

| Physiologic (%) | −18.43 | −53.62, 0.14 | 0.00 | −57.44, 29.92 | 0.56 | ||

| Self report (#) | −1.93 | −4.54, 0.00 | −1.26 | −2.78, 0.00 | 0.73 | ||

| Self report (%) | −28.74 | −59.41, 0.00 | −24.64 | −51.48, 0.00 | 0.71 | ||

| HF/2 wk (#, Questionnaire) | −42.00 | −70.00, 0.00 | −14.50 | −28.00, 12.00 | 0.09 | ||

| HF Severity | 0.00 | −0.37, 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.31, 0.13 | 0.23 | ||

| HF Bother | 0.00 | −0.33, 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.26, 0.13 | 0.35 | ||

| Weight (kg) | −7.50 | −10.00, −3.18 | 0.00 | −1.36, 1.59 | <.0001 | ||

| Weight (%) | −8.95 | −13.83, −3.45 | 0.00 | −1.38, 1.42 | <.0001 | ||

| % fat | −3.75 | −6.65, −2.00 | −0.50 | −1.20, 0.60 | <.0001 | ||

Note: Diary HF bothersome and severity scores ranged from 1–4 and were averaged over the monitoring period. Questionnaire HF frequency was recalled frequency of hot flashes over past two weeks (number HF/day*number of days experiencing HF)

Differences tested via Wilcoxon test

Table 4.

Correlation between change in hot flashes and change in weight (completers)

| r | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Physiologic hot flashes (#/24 hrs) | 0.31 | 0.08 |

| Reported hot flashes (#/24 hrs, diary) | 0.22 | 0.21 |

| Reported hot flashes (#/2 wks, questionnaire) | 0.47 | 0.006 |

| Hot flash severity | 0.36 | 0.04 |

| Hot flash bother | 0.28 | 0.12 |

N=33

We explored whether changes in hot flashes in response to the intervention varied by time since the FMP as an indicator of ovarian aging. Although not statistically significant (interactions by time since FMP p’s=.18–.65), diary-reported hot flash reductions in response to the intervention were somewhat more pronounced among women who were more proximal to their FMP (<=5 years: Md=−5.15, IQR=−7.32, −2.00, −66.4%) than among women farther from their FMP (>5 years: Md=−1.68, IQR=−3.04, 4.08, −23.4%). Similar patterns were observed for reductions in diary-reported hot flash severity (≤5 years: Md=−.39, IQR=−.68, 0 vs. >5 years: Md= −.06, IQR=−.33, .26) and bother (≤5 years: Md=−.22, IQR=−.78, .00 vs. >5 years: Md= −.06, IQR=−.33, .04). Correlations between changes in weight and diary-reported hot flashes were also more pronounced among women earlier in the transition (≤5 years since FMP: r=.41, p=.06; >5 years since FMP: r=−.02, p=.95).

Discussion

This pilot clinical trial indicates that a behavioral weight loss intervention for midlife women with hot flashes is feasible and acceptable. It also successfully produced weight loss at a magnitude similar to other behavioral weight loss trials.33 Further, the degree of weight loss correlated with the degree of reduction in hot flashes. This pilot study was designed to assess the feasibility and acceptability of this intervention among this population, and was not powered to detect intervention-associated changes in hot flashes. However, preliminary findings show greater reductions in questionnaire-reported hot flashes in the weight loss group relative to the control among women completing the trial, which suggest the potential value of a larger trial to assess weight loss for hot flash reduction.

Our findings support the acceptability and feasibility of this intervention, as session attendance, retention rates during the study period, and satisfaction were high. Women in the intervention groups attended on average 80% of the sessions. Participants rated the intervention highly on utility and satisfaction and reported that hot flash reduction was a major motivator to lose weight. These findings are relevant, as more silent conditions may not provide sufficient motivation for women to lose weight. Thus, the possibility of reductions in the often bothersome symptom of hot flashes may be an important motivator for women to engage in weight loss-related behaviors.

Women completing the intervention lost over 10% of their body weight and 5% of body fat, which was associated with improvement in self-reported hot flashes. This amount of weight loss is clinically significant (e.g., associated with improvements in lipids, insulin sensitivity, and blood pressure33). Although this study was not powered to detect intervention-associated changes in hot flashes, there was some indication of greater reductions in hot flashes in response to the intervention rather than control. In fact, questionnaire-reported hot flashes showed a pronounced reduction in response to the intervention (reductions by 63 hot flashes/two weeks, or 4.5 hot flashes/day). Further, reductions in reported hot flashes were correlated with reductions in weight, supporting a potential causal role of weight change in hot flash reduction.

These data add to the very limited existing literature on weight loss and hot flashes. To date, only two post-hoc analyses of existing trials have examined weight loss interventions in relation to hot flashes. One study analyzed data from a behavioral weight loss trial among overweight and obese women with urinary incontinence, finding improvements in ratings of hot flash bother among women randomized to intervention.20 A second analysis from the Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification Study, which assessed the occurrence and severity of hot flashes, produced conflicting results, a decrease in recalled hot flashes in women who, paradoxically, both gained and lost weight.21 Although these analyses provide important initial examinations of this topic, they were not designed to address this question, and they had limitations such as brief hot flashes measures and inclusion of primarily postmenopausal women, only a subset of which were experiencing hot flashes, and many of whom were using medications to treat hot flashes. A woman’s menopausal stage was not considered. Together with the existing pilot trial, these studies do underscore the importance of future well-powered trials specifically designed to address whether weight loss reduces hot flashes. Such a trial could both lend insight into the direction of relations between adiposity and hot flashes and point to a behavioral method to manage hot flashes that also has other salubrious effects.

Hot flashes were measured via several different modalities in this study, including physiologic monitor, diary, and questionnaire. Although women in the weight loss group showed reductions across modalities, our findings were significant only for questionnaire-reported hot flashes. This pattern was evident for the changes in hot flashes in response to the intervention as well as associations between hot flashes and weight loss. Why findings were noted principally for questionnaire-rated hot flashes is not immediately clear. Questionnaire-reported hot flashes differed from the other measures of hot flashes in that they were recalled over a two-week period and thus encompass a longer time period than the 24-hr or 3-day physiologic or diary measures, respectively. Because these hot flashes are recalled, these estimates incorporate the potential influence of memory, which could potentially be influenced by intervention group participation. Prior work has indicated that hot flash measures differ in important ways.35,36 It is notable that results of prior post-hoc analyses of clinical weight loss trials were based solely on questionnaire-reported hot flashes.20, 21 These findings further underscore that all hot flash measures are not interchangeable, and indicate the importance of conducting a well-powered trial using state-of-the art measures of hot flashes to assess changes in hot flashes in response to weight loss.

Prior work has indicated that the direction of relations between adiposity and hot flashes may change over the course of the menopausal transition, with positive associations between adiposity and hot flashes early in the transition and inverse associations later in the transition.17–19 The reasons for this reversal are not entirely clear. However, there is evidence to indicate that the role of adiposity in estrogen production may vary by age or menopausal stage,37, 38 which would in turn influence hot flash occurrence. Early in the transition higher adiposity may impair ovarian estradiol production, whereas later in the transition when ovarian function has ceased, body fat may be a key source of estrogen (estrone). We saw suggestive evidence for stronger reductions in reported hot flashes and more pronounced associations between changes in adiposity and changes in reported hot flashes among women closer to their FMP. However, these findings were highly exploratory and must be viewed with caution. The sample size was small, and this study was not designed to address any differential effect of weight loss on hot flashes by ovarian aging (e.g., early perimenopausal women were not included). These findings do indicate the potential importance of assessing any differential effect of weight loss by ovarian aging in future work.

This study had several limitations. As it was a pilot study designed to assess feasibility and acceptability, the sample size was modest. The control condition was a wait list control rather than an active control. Although no significant differences were noted between women completing the intervention and those who dropped out, the small sample size precludes firm conclusions that these women did not differ. Nonetheless, this study is the first specifically designed to test a behavioral weight loss intervention among women with hot flashes. Several hot flash measures were included, including physiologic measures, diary measures, and questionnaire measures, allowing comparison of findings across measures. A well-validated behavioral intervention was used that reliably produces weight loss here and in other studies. Further, both BMI and body fat were measured. A control condition was included.

Conclusion

This study indicates that a behavioral weight loss intervention can be acceptable and feasible among overweight and obese midlife women with hot flashes. It also suggests the potential promise of a weight loss intervention for hot flash reduction that should be evaluated more fully in future work. Based upon this demonstration of acceptability and feasibility, the next step in this work is a well-powered trial designed to test the impact of behavioral weight loss on hot flashes. The possibility of symptomatic relief of this bothersome midlife symptom of hot flashes may be a motivator for women to engage in this important health-promoting behavior, a behavior that may not only improve quality of life, but reduce later disease as women enter their postmenopausal years.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health through National Institute on Aging Grant AG029216 (to R.C.T.). We thank Dr. John Jakicic the University of Pittsburgh Obesity and Nutrition Research Center staff for assistance with intervention materials and Dr. Bret Goodpaster for assistance with body composition measurements.

Footnotes

No authors have conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Gold E, Colvin A, Avis N, et al. Longitudinal analysis of vasomotor symptoms and race/ethnicity across the menopausal transition: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Am J Public Health. 2006;96(7):1226–35. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnabei VM, Cochrane BB, Aragaki AK, et al. Menopausal symptoms and treatment-related effects of estrogen and progestin in the Women’s Health Initiative. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 Pt 1):1063–73. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000158120.47542.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams RE, Kalilani L, DiBenedetti DB, et al. Frequency and severity of vasomotor symptoms among peri- and postmenopausal women in the United States. Climacteric. 2008;11(1):32–43. doi: 10.1080/13697130701744696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Liu Z, Gracia CR. Duration of menopausal hot flushes and associated risk factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(5):1095–104. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318214f0de. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avis NE, Colvin A, Bromberger JT, et al. Change in health-related quality of life over the menopausal transition in a multiethnic cohort of middle-aged women: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Menopause. 2009;16(5):860–9. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181a3cdaf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kravitz HM, Zhao X, Bromberger JT, et al. Sleep disturbance during the menopausal transition in a multi-ethnic community sample of women. Sleep. 2008;31(7):979–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bromberger JT, Matthews KA, Schott LL, et al. Depressive symptoms during the menopausal transition: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) J Affect Disord. 2007;103(1–3):267–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicholson WK, Ellison SA, Grason H, Powe NR. Patterns of ambulatory care use for gynecologic conditions: A national study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(4):523–30. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.111795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kjerulff KH, Frick KD, Rhoades JA, Hollenbeak CS. The cost of being a woman: a national study of health care utilization and expenditures for female-specific conditions. Women’s health issues : official publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health. 2007;17(1):13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sherman S, Miller H, Nerurkar L, Schiff I. Research opportunities for reducing the burden of menopause-related symptoms. Am J Med. 2005;118(12 Suppl 2):166–71. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher TE, Chervenak JL. Lifestyle alterations for the amelioration of hot flashes. Maturitas. 2012;71(3):217–20. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryan K, Berkowitz R, Barbieri R, Dunaif A. Kistner’s Gynceology and Women’s Health. 7. St. Lewis: Mosby, Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thurston RC, Sowers MR, Sternfeld B, et al. Gains in body fat and vasomotor symptom reporting over the menopausal transition: the study of women’s health across the nation. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(6):766–74. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson GS. Human morphology and temperature regulation. Int J Biometeorol. 1999;43(3):99–109. doi: 10.1007/s004840050123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freedman RR. Physiology of hot flashes. Am J Human Biol. 2001;13(4):453–64. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thurston RC, Chang Y, Mancuso P, Matthews KA. Adipokines, adiposity, and vasomotor symptoms during the menopause transition: findings from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(3):793–800. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thurston RC, Santoro N, Matthews KA. Adiposity and hot flashes in midlife women: A modifying role of age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011 doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thurston RC, Sowers MR, Chang Y, et al. Adiposity and reporting of vasomotor symptoms among midlife women: the study of women’s health across the nation. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(1):78–85. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang AJ, Subak LL, Wing R, et al. An intensive behavioral weight loss intervention and hot flushes in women. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(13):1161–7. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroenke CH, Caan BJ, Stefanick ML, et al. Effects of a dietary intervention and weight change on vasomotor symptoms in the Women’s Health Initiative. Menopause. 2012;19(9):980–8. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31824f606e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reame NK. Fat, fit, or famished? No clear answers from the Women’s Health Initiative about diet and dieting for longstanding hot flashes. Menopause. 2012;19(9):956–8. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318263859a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dormire SL, Carpenter JS. An alternative to Unibase/glycol as an effective nonhydrating electrolyte medium for the measurement of electrodermal activity. Psychophysiology. 2002;39(4):423–6. doi: 10.1017.S0048577201393149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freedman RR. Laboratory and ambulatory monitoring of menopausal hot flashes. Psychophysiology. 1989;26(5):573–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1989.tb00712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA, Freedman RR, Munn R. Feasibility and psychometrics of an ambulatory hot flash monitoring device. Menopause. 1999;6(3):209–15. doi: 10.1097/00042192-199906030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thurston R, Matthews K, Hernandez J, De La Torre F. Improving the performance of physiologic hot flash measures with support vector machines. Psychophysiology. 2009;46(2):285–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00770.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thurston R, Hernandez J, Del Rio J, De la Torre F. Support vector machines to improve physiologic hot flash measures: Application to the ambulatory setting. Psychophysiology. 2011;48(7):1015–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2010.01155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grady D, Macer J, Kristof M, Shen H, Tagliaferri M, Creasman J. Is a shorter hot flash diary just as good as a 7-day diary? Menopause. 2009;16(5):932–6. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181a4f558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Craig CL, Marshall A, Sjostrom M, et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-Country Reliability and Validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381–95. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psych Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wadden TA, West DS, Delahanty L, et al. The Look AHEAD study: a description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting it. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(5):737–52. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The Diabetes Prevention Program. Design and methods for a clinical trial in the prevention of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(4):623–34. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.4.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Services UDoHaH, editor. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: The evidence report. National Institutes of Health. National Heart Lung and Blood Institute; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elobeid MA, Padilla MA, McVie T, et al. Missing data in randomized clinical trials for weight loss: scope of the problem, state of the field, and performance of statistical methods. PLoS One. 2009;4(8):e6624. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fu P, Matthews K, Thurston R. How well do different measurement modalities estimate the number of vasomotor symptoms? Findings from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation FLASHES Study. Menopause. 2014;21(2):124–30. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e318295a3b9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thurston RC, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Sherwood A. Emotional antecedents of hot flashes during daily life. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(1):137–46. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000149255.04806.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Gracia CR. Obesity and reproductive hormone levels in the transition to menopause. Menopause. 2010;17(4):718–26. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181cec85d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Randolph JF, Jr, Zheng H, Sowers MR, et al. Change in follicle-stimulating hormone and estradiol across the menopausal transition: effect of age at the final menstrual period. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(3):746–54. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]