Abstract

Background

The use of multidisciplinary clinics (MDCs) for outpatient cancer evaluation is increasing. MDCs may vary in format, and data on whether MDCs change prostate cancer (PCa) care are limited. Here we report on the setup and design of a relatively new PCa MDC clinic. Because MDC evaluation was associated with a comprehensive re-evaluation of all patients' staging and risk stratification data, we studied the frequency of changes in PCa grade and stage upon MDC evaluation, which provides a unique estimate of the magnitude of pathology, radiology, and exam-based risk stratification in a modern tertiary setting.

Methods

In 2008–2012, 887 patients underwent consultation for newly diagnosed PCa at the Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) weekly MDC. In a same-day process, patients are interviewed and examined in a morning clinic. Examination findings, radiology studies, and biopsy slides are then reviewed during a noon conference that involves real-time collaboration among JHH attending specialty physicians: urologists, radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, pathologists, and radiologists. During afternoon consultations, attending physicians appropriate to each patients' eligible treatment options individually meet with patients to discuss management strategies and/or clinical trials. Retrospective chart review identified presenting tumor characteristics based on outside assessment, which was compared with stage and grade as determined at MDC evaluation.

Results

Overall, 186/647 (28.7%) had a change in their risk category or stage. For example, 2.9% of men were down-classified as very-low-risk, rendering them eligible for active surveillance. 5.7% of men thought to have localized cancer were up-classified as metastatic, thus prompting systemic management approaches. Using NCCN guidelines as a benchmark, many men were found to have undergone nonindicated imaging (bone scan 23.9%, CT/MRI 47.4%). The three most chosen treatments after MDC evaluation were external beam radiotherapy +/− androgen deprivation (39.3%), radical prostatectomy (32.0%) and active surveillance/expectant management (12.9%).

Conclusions

A once-weekly same-day evaluation that involves simultaneous data evaluation, management discussion, and patient consultations from a multidisciplinary team of PCa specialists is feasible. Comprehensive evaluation at a tertiary referral center, as demonstrated in a modern MDC setting, is associated with critical changes in presenting disease classification in over one in four men.

Keywords: pathology, radiology, staging, grading, diagnosis

Introduction

The past several years have witnessed growing interest from medical and governmental organizations in improvement and personalization of cancer care. The Institute of Medicine's recommendations for optimizing cancer care include an emphasis on a coordinated team approach [1], and the 2010 United States Affordable Care Act, guided by cost-containment, seeks to improve quality and efficiency of care, as well as promotes rigorous effectiveness comparisons of therapies for chronic conditions [2]. One tool increasingly believed to improve personalization and effectiveness of quality cancer care is the use of collaborative multidisciplinary teams to guide the potentially complex management of cancer patients [3–5].

A multidisciplinary cancer clinic (MDC) can have several different formats, but typically involves the patient receiving a same-day evaluation by multiple treating disciplines, thus improving patients' access to multiple expert opinions and potentially resulting in improved plans of care in complex clinical scenarios. The MDC approach for prostate cancer (PCa) evaluation has been described at several centers [4–10].

For men with PCa, data on if and how the MDC approach changes PCa outcomes are limited. Gomella et al. reported showing that for the cohort of men with locally advanced PCa evaluated in a MDC, overall survival was higher when compared to outcomes from NCI-SEER data [10]. However this conclusion was limited in that it compared national averages to a single urban tertiary referral center. In studies of limited cohorts (92 to 239 patients), others have shown that MDC evaluation is associated with changes in management approach [5, 9].

Here we describe the setup and format of a relatively new PCa MDC clinic initiated in 2008. Further, the real-time comprehensive staging and risk-stratification evaluation of each patient at the MDC allowed us to gain a unique perspective to assess the affect of pathology, radiology, and exam-based disease reclassification in a modern tertiary cohort. Therefore, we assessed the extent of disease classification changes (and thus altered treatment options [11]) in the first four years of the PCa MDC experience, comprised of 887 men referred to the Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) from 2008–2012.

Materials and Methods

Clinic Format

The MDC team is composed of attending physicians from five disciplines: urology, radiation oncology, medical oncology, radiology, and pathology. Patients are either self-referred or provider-referred. Oftentimes individual providers who evaluate patients in a non-MDC setting will make referrals based on high-risk features when multimodal treatment approaches or clinical trials are thought to be appropriate or in difficult cases when the patient and/or physician preferred treatment option is unclear.

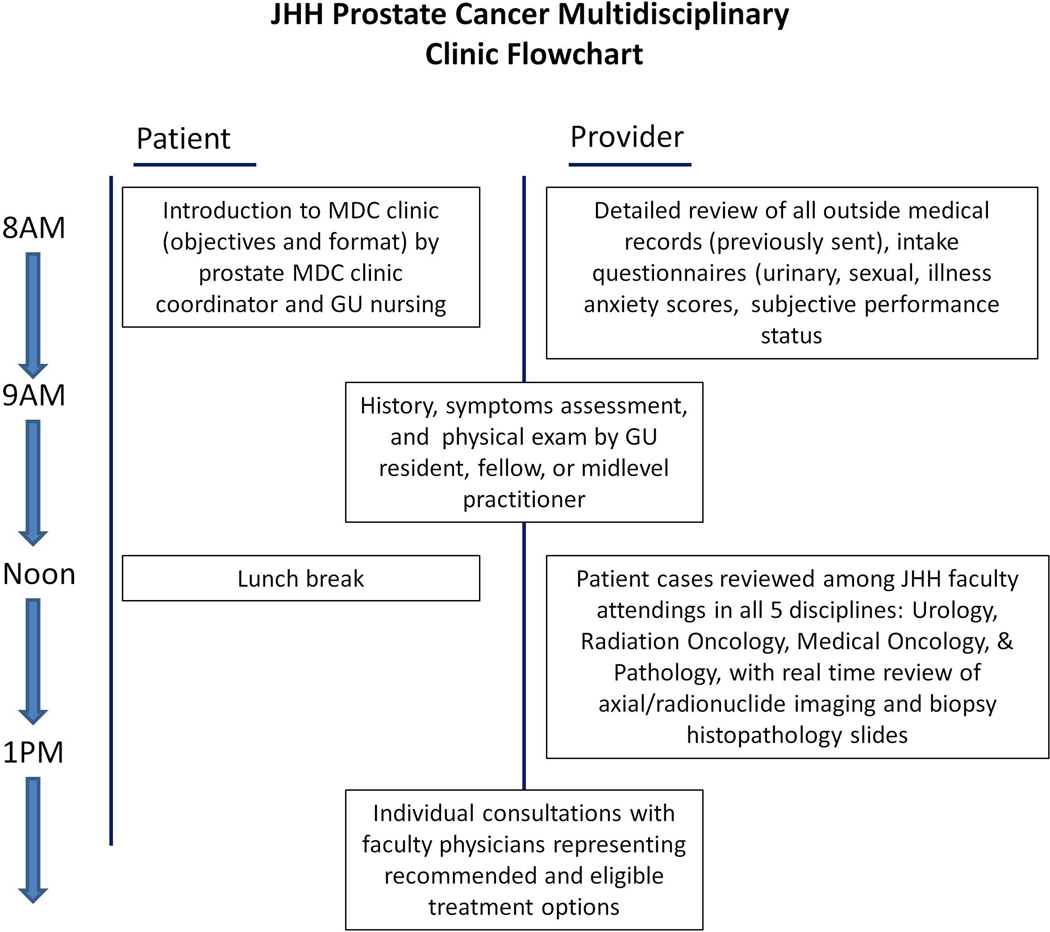

The MDC begins with a group meeting when the MDC coordinator reviews the purpose and format of the clinic and provides a brief overview of stage-specific PCa management options. In a same-day evaluation, each patient subsequently undergoes comprehensive history and physical in the morning by a midlevel practitioner, resident or fellow (Figure 1). The clinic unit (examination rooms, provider workspace, central nursing station) is utilizes radiation oncology space within the JHH Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center. Each patient's case is presented at a noon conference that includes the entire multidisciplinary team. All radiology films are re-reviewed by a dedicated genitourinary (GU) radiologist and all biopsy specimens are re-examined by a dedicated GU pathologist. Management options are discussed among the group. Subsequently physicians who specialize in each treatment modality for which a patient is eligible perform individual same-day consultations. When applicable, specialty attending physicians and dedicated trial nurses will also discuss clinical trials if a patient meet eligibility criteria.

Figure 1.

Structure and work flowchart of JHH MDC evaluation

Assessment of risk-stratification changes and statistical analyses

For some men, the presenting PCa stage, grade and risk classification may be altered based on the MDC evaluation. To assess the impact of the MDC on available treatment options, presenting disease characteristics before MDC were compared to disease features after MDC and the number of men for whom clinically relevant changes in risk classification or disease stage was assessed. Analyses of changes in disease stage, tumor Gleason grade, and risk-classification were performed only in men for whom complete laboratory, physical exam, biopsy, and radiology data were known at the time of referral to the MDC.

Additionally, we assessed whether the imaging studies that had been obtained for each patient were indicated, using National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines as a standard [11]. For this purpose the probability of nodal metastasis was determined using the Partin tables [12].

Patient demographic information (median income, educational attainment, distance from JHH) were estimated using 5-digit zip code tabulation areas (ZCTAs, publicly available from U.S. census data) [13]. This study was approved by the institutional review board. Appropriate comparative tests were used. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Results

Between May 2008 and December 2012, 887 consecutive patients underwent consultation at the JHH PCa MDC. Median age at presentation was 64 years. 26.5% of evaluated patients traveled from a distance of ≥200 miles for consultation. The three most chosen treatments after MDC evaluation were external beam radiotherapy +/− androgen deprivation (39.3%), radical prostatectomy (32.0%), and active surveillance/expectant management (12.9%) (Table 1). In the most recent calendar year of analysis, 62.7% (121/193) of evaluated patients were deemed eligible for one or multiple clinical trials offered through Johns Hopkins, and 19.8% (24/121) of eligible patients ultimately elected to enroll. 74.6% (144/193) of evaluated patients chose to provide a urine and/or blood sample for use in research studies.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics of men evaluated at the JHH PCa MDC, 2008–2012

| # of evaluable patients | 887 |

| Median age (IQR) | 64.0 (58.0, 70.0) |

| Distance traveled to JHH (miles) | |

| 0–200 | 654 (73.7%) |

| 200–500 | 104 (11.7%) |

| 500–1000 | 73 (8.2%) |

| >1000 | 56 (6.3%) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 157/166 (94.6%) |

| 1–2 | 9/166 (5.4%) |

| Median IPSS (IQR) | 7.0 (3.0, 12.0) |

| Median IIEF (IQR) | 20.0 (7.0, 24.0) |

| Median PSA (IQR) | 5.9 (4.4, 9.8) |

| Chose management at JHH | 400 (45.1%) |

| Management approach | |

| Active surveillance / expectant management | 90/698 (12.9%) |

| Radical prostatectomy | 223/698 (32.0%) |

| EBRT +/− ADT | 274/698 (39.3%) |

| Brachytherapy +/− ADT | 43/698 (6.2%) |

| ADT +/− chemotherapy | 47/698 (6.7%) |

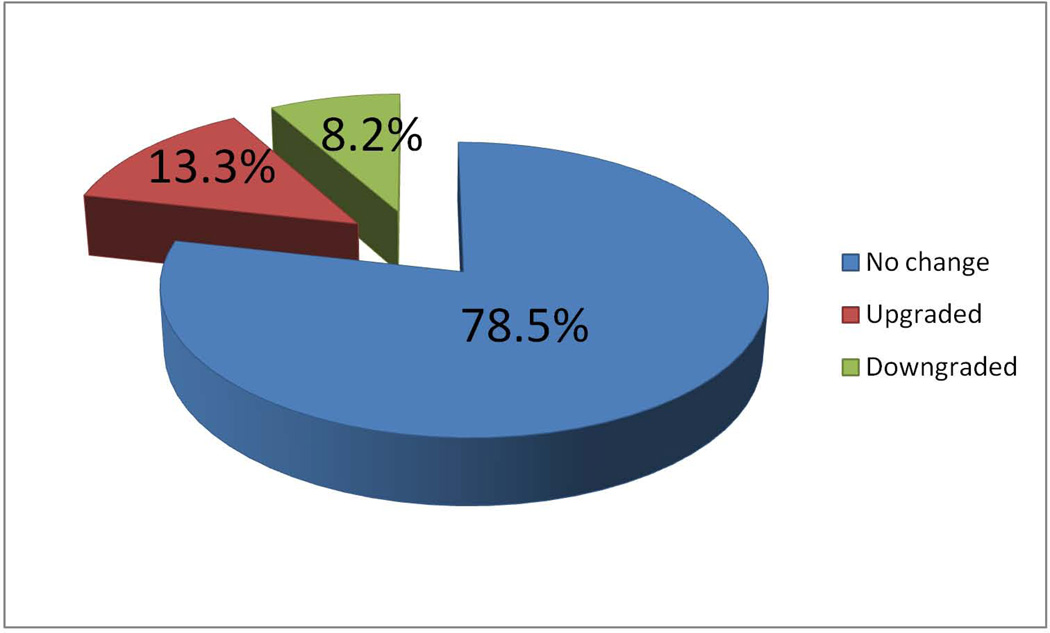

Among men who had known clinical stage at the time of referral (before MDC), the frequency of up-staging and down-staging (based on digital rectal exam) after MDC evaluation was 17.8% and 9.4%, respectively (Table 2). After pathological re-review, the frequency of Gleason up-grading and down-grading was 13.3% and 8.2%, respectively (Figure 2). Among the 629 men where perineural invasion (PNI) on biopsy was assessed prior to referral to MDC, 4.3% of men who were not known to have PNI, had PNI subsequently identified by the JHH pathologist (Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes in disease stage, grade, volume, and risk-classification after evaluation in the JHH PCa MDC, 2008–2012 (denominator reflects number of men with clinical data for each measure known both before and after MDC evaluation)

| Clinical stage (DRE) | |

| Down-staged | 27/287 (9.4%) |

| Up-staged | 51/287 (17.8%) |

| Clinical stage (imaging-based) | |

| Up-staged from N0 to N1 | 12/334 (3.6%) |

| Down-staged from N1 to N0 | 2/334 (0.6%) |

| Up-staged from M0 to M1 | 3/344 (0.9%) |

| Down-staged from M1 to M0 | 5/344 (1.5%) |

| Gleason sum | |

| Down-graded | 70/858 (8.2%) |

| Up-graded | 114/858 (13.3%) |

| Detailed Gleason sum changes among men with cancer on both pre- and post-MDC biopsy | |

| Down-grade by 2 Gleason points | 6/855 (0.7%) |

| Down-grade by 1 Gleason point | 62/855 (7.3%) |

| No change in Gleason sum | 674/855 (78.8%) |

| Up-grade by 1 Gleason point | 91/855 (10.6%) |

| Up-grade by 2 Gleason points | 21/855 (2.5%) |

| Up-grade by 3 Gleason points | 1/855 (0.1%) |

| Number of cores involved with cancer | |

| Lower | 69/757 (9.1%) |

| Higher | 88/757 (11.6%) |

| Perineural invasion | |

| Absent but noted before MDC | 16/629 (2.5%) |

| Present but not noted before MDC | 27/629 (4.3%) |

| NCCN risk classification | |

| Down-classified to NO CANCER | 2/647 (0.3%) |

| Down-classified to very-low-risk | 19/647 (2.9%) |

| Up-classified from very-low-risk | 2/647 (0.3%) |

| Down-classified to low-risk | 28/647 (4.3%) |

| Up-classified from low-risk | 8/647 (1.2%) |

| Up-classified to intermediate-risk | 6/647 (0.9%) |

| Down-classified from intermediate-risk | 35/647 (5.4%) |

| Up-classified to high-risk | 24/647 (3.7%) |

| Down-classified from high-risk | 18/647 (2.8%) |

| Up-classified to metastatic (N1 or M1) | 37/647 (5.7%) |

| Down-classified from metastatic (N1 or M1) | 7/647 (1.1%) |

| ANY RISK CLASSIFICATION CHANGE | 186/647 (28.7%) |

Figure 2.

Changes in Gleason grade after JHH MDC evaluation among 865 men with known Gleason grade at time of referral

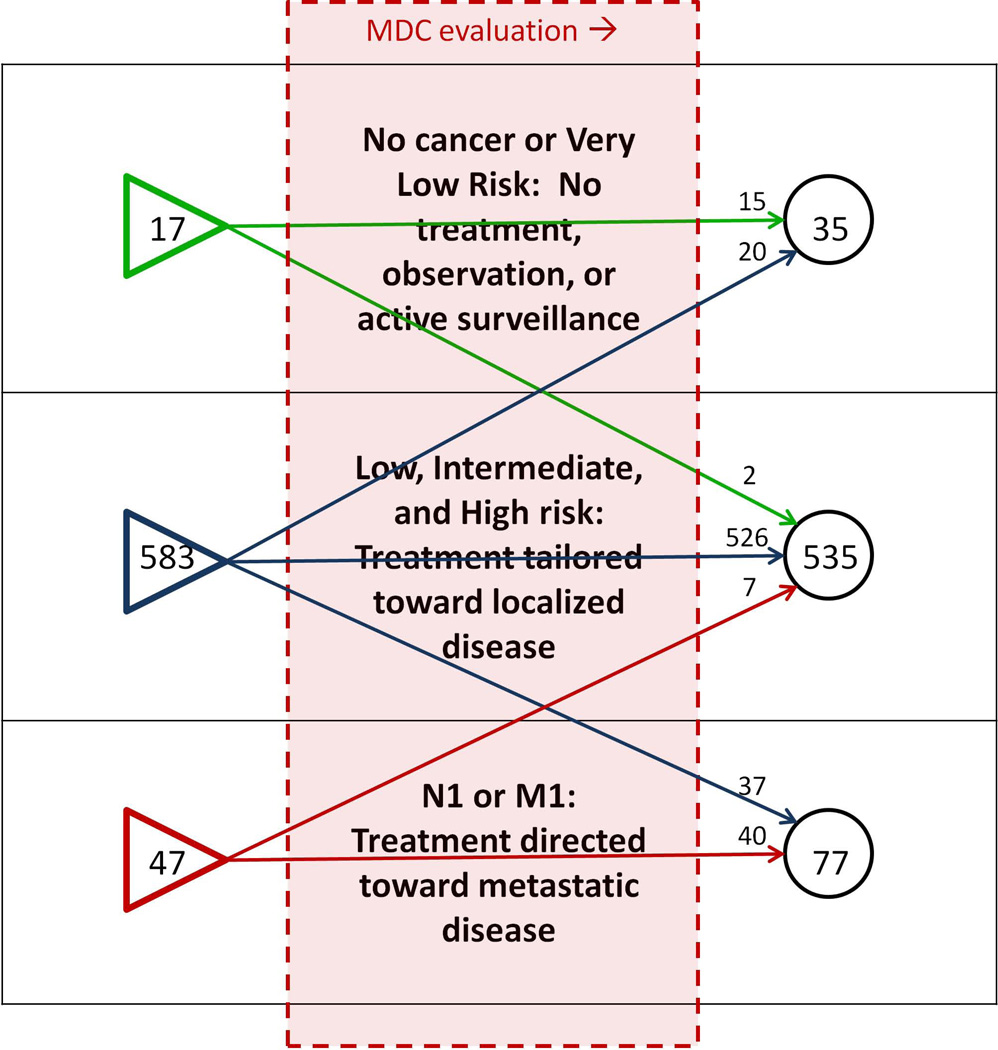

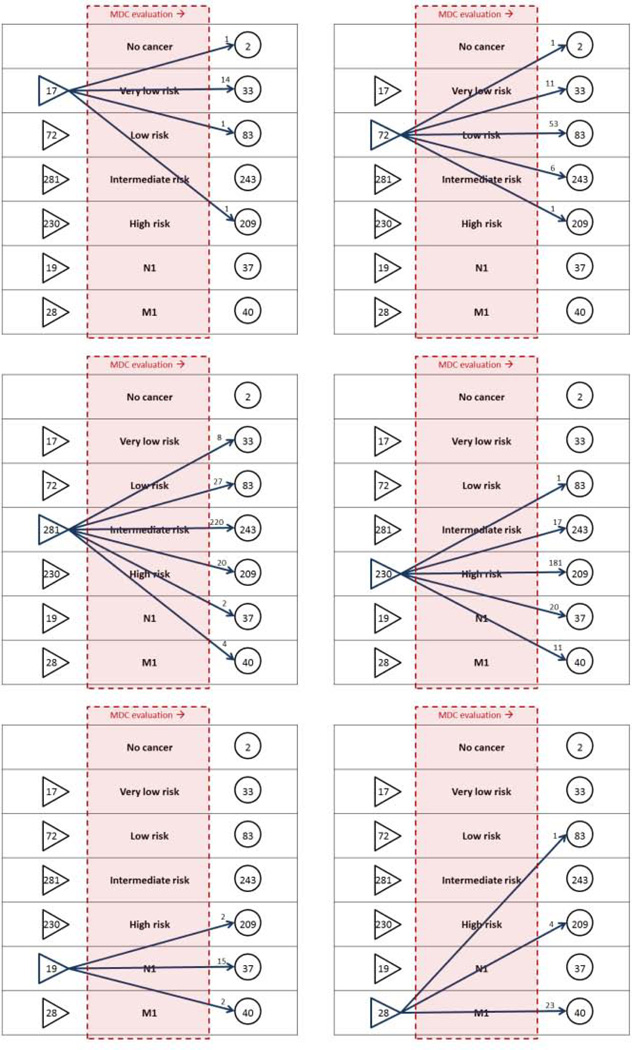

28.7% of men underwent change in their NCCN risk-class or N/M stage after MDC evaluation, including 2.9% of men who were down-classified as very-low-risk (active surveillance eligible) (Figures 3, 4). Nearly one-third of patients were referred with a diagnosis of high-risk or metastatic PCa (Figure 4). Among men referred with high-risk PCa, 2.8% were down-classified into a lower risk category after comprehensive evaluation, and among men referred with lower-risk cancers, 3.7% were up-classified into the high-risk category (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Changes in offered management options, related to presenting disease stage

Figure 4.

Changes in NCCN risk classification after evaluation at the JHH PCa MDC, 2008–2012

Of men with metastatic evaluations, 2.3% sustained a change in their M stage and 4.2% in their N stage. After MDC evaluation of all clinical and radiologic data, 3/344 (0.9%) were newly diagnosed with M1 PCa and 5/344 (1.5%) were initially thought to have metastatic disease but were diagnosed with M0 PCa. Similarly, 12/334 (3.6%) were newly diagnosed with N1 disease, whereas 2/334 (0.6%) were initially thought to have nodal metastases but were diagnosed with N0 PCa (Table 2).

Gleason up-grading after MDC evaluation was associated with higher median serum prostate specific antigen (PSA, Table 3). Men who were up-staged from N0 to N1 disease and those who were up-staged from M0 to M1 disease had significantly higher median PSA (12.9 ng/ml and 31.0 ng/ml, respectively) than men who did not sustain an increase in their N or M stage (Table 3). PSA among men with localized PCa who sustained an increase in their NCCN risk classification was lower than among men who were not up-classified (16.9 ng/ml vs 6.1 ng/ml, p = 0.040, which was expected as any man with PSA >10 or >20 ng/ml on initial workup was correctly classified as intermediate- or high-risk by default).

Table 3.

Median PSA (IQR) associated with adverse changes in presenting disease characteristics, JHH PCa MDC 2008–2012

| PSA if no | PSA if yes | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gleason up-graded | 5.7 (4.3, 9.4) | 6.9 (4.7, 21.0) | 0.005* |

| DRE up-staged | 5.6 (4.2, 10.0) | 6.0 (4.0, 15.1) | 0.294* |

| N0 to N1 | 6.4 (4.6, 12.6) | 12.9 (8.3, 42.9) | 0.001* |

| M0 to M1 | 6.4 (4.6, 12.1) | 31.0 (13.5, 77.9) | <0.001* |

| NCCN risk up-classified | 6.5 (4.6, 13.0) | 9.7 (5.4, 28.9) | *0.007 |

Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney rank-sum test

We additionally examined the utilization of diagnostic imaging in the study group. Using the disease stage, grade and risk characteristics post-MDC evaluation as a guide for indicating imaging tests, it was found that 23.9% of men who underwent a bone scan did so in the absence of indication (per NCCN guidelines), and 47.4% of men who underwent axial imaging (CT, MRI) did so in the absence of indication (Table 4). However, non-indicated imaging still had potential for affecting disease staging. Among 164 men who had undergone non-indicated bone scans, one was referred to the JHH MDC with what was thought to be M1 disease that was down-staged to M0 after comprehensive evaluation. Similarly, among 314 men who underwent non-indicated axial imaging, stage in three changed from N0 to N1, two N1 to N0, one M0 to M1, and five M1 to M0.

Table 4.

Risk stratification and indicated imaging according to stage/grade evaluation at referral and after JHH PCa MDC evaluation, 2008–2012 (analysis limited to men with adequate data for NCCN risk stratification pre- and post-MDC)

| Before MDC evaluation | After MDC evaluation | |

|---|---|---|

| Risk category | ||

| Very low | 17/647 (2.6%) | 35/647 (5.4%) |

| Low | 72/647 (11.1%) | 83/647 (12.8%) |

| Intermediate | 281/647 (43.4%) | 243/647 (37.6%) |

| High | 230/647 (35.5%) | 209/647 (32.3%) |

| Metastatic | 47/647 (7.3%) | 77/647 (11.9%) |

| Bone scan indicated* | 249/647 (38.5%) | 296/674 (43.9%) |

| CT/MRI indicated* | 36/647 (5.6%) | 123/658 (18.7%) |

| Work-up included non-indicated bone scan* | 214/647 (33.1%) | 161/674 (23.9%) |

| Work-up included non-indicated CT/MRI* | 425/647 (65.6%) | 312/658 (47.4%) |

Denominators differ before and after MDC evaluation due to increased number of patients with complete staging/risk-stratification information

Ultimately 45.1% of patients chose to have their PCa managed at JHH. Demographic characteristics such as distance traveled to JHH and median income were not associated with preferred treatment location. Age and educational attainment had statistically significant associations with preferred treatment location; however these differences were small in magnitude and therefore not considered clinically meaningful. Men who underwent NCCN risk up-classification were more likely to seek treatment at a different treatment location (12.7% vs 7.6%, p=0.033, Table 5).

Table 5.

Factors associated with subsequent disease management at JHH

| Managed at JHH (400) |

Managed elsewhere (487) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (IQR) | 63.0 (57.0, 69.0) | 65.0 (58.0, 71.0) | 0.018* |

| Distance traveled to JHH (miles) | 0.099 | ||

| 0–200 | 311/400 (77.8%) | 343/487 (70.4%) | |

| 200–500 | 40/400 (10.0%) | 64/487 (13.1%) | |

| 500–1000 | 29/400 (7.3%) | 44/487 (9.0%) | |

| >1000 | 20/400 (5.0%) | 36/487 (7.4%) | |

| Geography-based demographics | |||

| Median income ($ U.S.) | 59700 | 60300 | 0.728 |

| % high-school degree | 34.3 | 32.1 | 0.026 |

| % college degree | 11.5 | 13.5 | 0.015 |

| Up-graded | 51/387 (13.2%) | 63/471 (13.4%) | 0.932 |

| Down-graded | 34/387 (8.8%) | 36/471 (7.6%) | 0.543 |

| NCCN risk up-classified | 21/278 (7.6%) | 47/369 (12.7%) | 0.033 |

| NCCN risk down-classified | 39/278 (14.0%) | 34/369 (9.2%) | 0.055 |

Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney rank-sum test

Discussion

The format of a MDC can vary, ranging from individual patient consultations that occur on different days [5], to more of a 'tumor board' approach that involves patient case reviews without actual patient consultations [15]. PCa MDCs vary with regard to systematic re-review of pathologic and radiologic data [5, 6, 7]. Here we demonstrate the basic format of a weekly same-day PCa MDC. This clinic setup has proven feasible and permits approximately 200 patient evaluations per year. Further we show the magnitude of disease re-classification that may occur due to comprehensive evaluation at a tertiary referral center. At the JHH PCa MDC, this re-evaluation includes pathology and radiology re-review in concert with consensus decision making among urologists, radiation oncologists, and medical oncologists. In turn, these changes potentially alter the menu of management options for which each patient is eligible, and the magnitude of these option-altering changes is 28.7% in this study (the proportion of men who had a change in their NCCN risk classification, N stage, or M stage).

For example, classification into or out of the NCCN very low risk category affects a man's eligibility for active surveillance (at JHH very low risk disease is a criterion for entry into active surveillance). On the other extreme, change in N or M stage affects whether a man is eligible for local therapy for localized PCa versus systemic therapy for metastatic disease. Changes among low, intermediate, and high-risk classifications also have important treatment implications, such as eligibility for brachytherapy monotherapy or whether external beam radiation therapy is accompanied by androgen deprivation therapy, and if so, for what duration [11].

The MDC is an increasingly utilized tool in the evaluation of newly diagnosed PCa. The ultimate goal of the MDC is to improve patient outcomes, yet this finding is seldom reported due to difficulties inherent to assessing comparative health outcomes in patients who undergo MDC consultations. A large MDC experience (Thomas Jefferson University) reported that overall survival for men with locally advanced PCa evaluated at the MDC exceeded that of a comparable cohort, as reflected in the SEER database [10]. Whether this survival difference reflects a true MDC effect or is related to selection bias, co-morbidity differences between groups, confounding factors when comparing a single referral center to a national database, or the well-described benefit of treatment at a high-volume cancer center is unclear [14].

The role of MDCs in altering management decisions has been studied. Aizer et al. did demonstrate that within a multi-center university health system, men with low-risk PCa who were evaluated in an MDC were more likely to choose active surveillance than men who presented to single-provider clinics (adjusted odds ratio 2.15, p=0.02) [5]. The underlying reason is unclear, but the study implies that in a single-provider setting, a specialist is more likely to offer and recommend the treatment modality that s/he administers.

Others have reported changes in management after PCa MDC evaluation. Magnani et al. reported an 11% frequency with which patients referred to an MDC had been inappropriately prescribed androgen deprivation therapies which were subsequently discontinued (sample size not reported) [7]. Kurpad et al., analyzing 92 PCa patients evaluated at a MDC, found a 25% frequency change in presenting stage and 21.8% frequency of change in treatment plan, the majority of which was a change from treatment to active surveillance among men with T1c disease [9]. Changes in disease grade and stage and resulting changes in management options have also been reported in breast cancer1 and pancreatic cancer [3]. A common element in these MDCs are pathology and radiology review of outside tissues and films [3, 9, 15].

Pathological re-review of prostate biopsy cores is paramount. It has been shown that community-based pathologists under-report Gleason scores to varying extents [16, 17]. Further, second-opinion pathology review at a referral center has the potential to a change the assessment of whether cancer is present at all (1.3% of referred cancer cases re-classified cancer as benign in one study [18]), which has obvious implications for management. It is our recommendation that all PCa MDCs entail pathological re-review of biopsy specimens.

An unexpected finding of this study was the frequency of bone scans and CT/MRI for staging when such imaging is not indicated by commonly available guidelines. 33% of bone scans were obtained without indication, and 58% of axial scans (CT/MRI) were non-indicated. These rates are quite high and also in line with data from SEER-Medicare [19]. Interestingly, 'non-indicated' imaging had the potential to affect disease staging. Others have noted that surgical staging may be better predicted by imaging than nomograms, suggesting that there is room for improvement in guidelines for imaging for pre-operative staging [20]. It is also noteworthy that the non-indicated imaging rates are lower when using the post-MDC-evaluation disease characteristics as a reference: prior to evaluation at the MDC, patients were subject to over-imaging based on risk, yet also subject to under-classification of risk category at the time of original diagnosis.

It should also be emphasized that seven patients previously thought to have metastatic disease were re-classified to localized cancer after attending the MDC, thus opening the door to potentially curative surgical treatment or radiation therapy. Thus the MDC can act as a diagnostic safety net as a result of re-evaluation of critical staging data.

We would like to emphasize that the current report does not demonstrate that the MDC improves outcomes. From an oncologic perspective, this can only be demonstrated by showing that evaluation in a PCa MDC is followed by improved PCa specific survival when compared to a matched cohort that undergoes disease management without MDC evaluation. From a health-economics perspective, whether MDCs improve PCa care and are cost-justified depend on comparative effectiveness of MDCs versus standard outpatient evaluation, downstream direct and indirect costs of evaluation and treatment and follow-up from both routes, and costs per quality-adjusted and disability-adjusted life year. However, the MDC is an excellent option for the patient who prefers his diagnostic data to undergo second-opinion evaluation at a tertiary referral center and who prefers to have risk-appropriate consultations from specialists who can provide education regarding management options. An additional advantage of the MDC is that is a unique setting from which to evaluate patient eligibility for clinical trials due to the collaborative case discussion from faculty in multiple diagnostic and treating disciplines. As demonstrated in the Johns Hopkins PCa MDC, about two-thirds of patient will be eligible for one or more clinical trials, and about 20% of those eligible patients will choose to enroll.

A limitation of this study is its retrospective design. Furthermore, as the majority of patients did not undergo subsequent management at JHH, their oncologic outcomes could not be fully studied. A strength of this paper, among published reports, is that it represents a relatively large experience. Others have reported how MDC consultations change the preferred management approach. Recognizing that most patients referred to our MDC were undecided on management approach, and that for the majority of patients there are a menu of options, we did not study changes in 'the recommended treatment plan'; rather, we studied changes in disease classification that also changed the management options available to each patient. The latter analytical approach may be better suited to the unique aspects of PCa management.

Conclusions

A once-weekly same-day evaluation that involves simultaneous data evaluation, management discussion, and patient consultations from a multidisciplinary team of PCa specialists is feasible. Comprehensive evaluation at the JHH prostate cancer MDC leads to critical changes in presenting disease characteristics that potentially alters management options in up to 29% of men. In this referral population, risk-based imaging to assess for lymphadenopathy and metastases is over-utilized. With upwards of one in four men undergoing changes to their risk classification that can affect treatment options, tertiary evaluation of newly diagnosed prostate cancer in a multidisciplinary setting may have implications for optimizing cancer care that is team-based, correctly tailored to individual risk factors, and potentially cost-saving.

Acknowledgements (the PCMDC team)

Marian G Raben MS4, Danny Y Song MD4, Charles G Drake MD PhD2, Theodore L DeWeese MD4, Alan W Partin MD PhD1, Trinity J Bivalacqua MD PhD1,2, Georges J Netto MD1,2,3, Katarzyna J Macura MD1,2,5

1Brady Institute of Urology, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, Maryland

2Department of Oncology, the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, Maryland

3Department of Pathology, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, Maryland

4Department of Radiation Oncology, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, Maryland

5Department of Radiology, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, Maryland

Footnotes

Disclosures:

none

References

- 1.Spinks T, Albright HW, Feeley TW, et al. Ensuring quality cancer care: a follow-up review of the Institute of Medicine’s 10 recommendations for improving the quality of cancer care in America. Cancer. 2012;118(10):2571–2582. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swain S, Hudis C. Health policy: Upholding the Affordable Care Act--implications for oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2012;9(9):491–492. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pawlik TM, Laheru D, Hruban RH, et al. Evaluating the impact of a single-day multidisciplinary clinic on the management of pancreatic cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2008;15(8):2081–2088. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9929-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart SB, Bañez LL, Robertson CN, et al. Utilization trends at a multidisciplinary prostate cancer clinic: initial 5-year experience from the Duke Prostate Center. J. Urol. 2012;187(1):103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aizer Aa, Paly JJ, Zietman AL, et al. Multidisciplinary Care and Pursuit of Active Surveillance in Low-Risk Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30(25) doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.8466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valicenti RK, Gomella L, El-Gabry E, et al. The multidisciplinary clinic approach to prostate cancer counseling and treatment. Semin. Urol. Oncol. 2000;18(3):188–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magnani T, Valdagni R, Salvioni R, et al. The 6-year attendance of a multidisciplinary prostate cancer clinic in Italy: incidence of management changes. BJU Int. 2012;110(7):998–1003. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.10970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basler JW, Jenkins C, Swanson G. Multidisciplinary management of prostate malignancy. Curr. Urol. Rep. 2005;6(3):228–234. doi: 10.1007/s11934-005-0012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurpad R, Kim W, Rathmell WK, et al. A multidisciplinary approach to the management of urologic malignancies: does it influence diagnostic and treatment decisions? Urol. Oncol. 2011;29(4):378–382. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomella BLG, Lin J, Hoffman-Censits J, et al. Multidisciplinary Care Enhancing Prostate Cancer Care Through the Multidisciplinary Clinic Approach : A 15-Year Experience. J. Oncol. Pract. 2010;6(6):e5–e10. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2010.000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NCCN. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology: prostate cancer. Natl. Compr. cancer Netw. 2012 Version 3. Available at: NCCN.org. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eifler JB, Feng Z, Lin BM, et al. An updated prostate cancer staging nomogram (Partin tables) based on cases from 2006 to 2011. BJU Int. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11324.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.United States Census Bureau: American Fact Finder. Available at: http://factfinder2.census.gov.

- 14.Begg CB, Cramer LD, Hoskins WJ, et al. Impact of hospital volume on operative mortality for major cancer surgery. JAMA. 1998;280(20):1747–1751. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.20.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newman EA, Guest AB, Helvie MA, et al. Changes in surgical management resulting from case review at a breast cancer multidisciplinary tumor board. Cancer. 2006;107(10):2346–2351. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinberg D, Sauvageot J, Piantadosi S, et al. Correlation of prostate needle Biopsy and radical prostatectomy Gleason grade in academic and community settings. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1997;21(5):566–576. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199705000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Renshaw AA, Schultz D, Cote K, et al. Accurate Gleason grading of prostatic adenocarcinoma in prostate needle biopsies by general pathologists. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2003;127(8):1007–1008. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-1007-AGGOPA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Epstein JI, Walsh PC, Sanfilippo F. Clinical and cost impact of second-opinion pathology: review of prostate biopsies prior to radical prostatectomy. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1996;20(7):851–857. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199607000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Makarov DV, Desai RA, Yu JB, et al. The population level prevalence and correlates of appropriate and inappropriate imaging to stage incident prostate cancer in the medicare population. J. Urol. 2012;187(1):97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schiavina R, Scattoni V, Castellucci P, et al. 11C-choline positron emission tomography/computerized tomography for preoperative lymph-node staging in intermediate-risk and high-risk prostate cancer: comparison with clinical staging nomograms. Eur. Urol. 2008;54(2):392–401. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]