Abstract

Background/Aims:

To assess the antiviral efficacy of lamivudine (LAM), entecavir (ETV), telbivudine (LDT), and lamivudine and adefovir dipivoxil (CLA) combination in previously untreated hepatitis B patients at different time points during a 52-week treatment period.

Patients and Methods:

A total of 164 patients were included in this prospective, open-label, head-to-head study. Serum levels of alanine transaminase (ALT), hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA, and hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) were measured at baseline, and at 12, 24, and 52 weeks of treatment.

Results:

Median reductions in serum HBV DNA levels at 52 weeks (log10 copies/mL) were as follows: LAM, 3.98; ETV, 3.89; LDT, 4.11; and CLA, 3.36. The corresponding HBV DNA undetectability rates were 83%, 96%, 91%, and 89%, respectively. These two measures showed no significant intergroup differences. Clinical efficacy appeared related to HBV DNA level reduction after 24 weeks of therapy. Patients were divided into three groups based on HBV DNA levels at week 24: Undetectable (<103 copies/mL), detectable but <104 copies/mL, and >104 copies/mL. Patients with levels below quantitation limit (QL) were analyzed at 52 weeks for HBV DNA undetectability rate (94%), ALT normalization rate (83%), and viral breakthrough rate (0%). The corresponding values in the QL-104 copies/mL group were 50%, 75%, and 13%, whereas those in the above 104 copies/mL group were 53%, 65%, and 18%. There were significant differences at week 52 for HBV DNA levels and viral breakthrough rate between the three groups.

Conclusions:

Different nucleos(t)ide (NUC) analogues tested exhibited no significant differences in effectiveness for Chinese NUC-naive HBV patients during 1-year treatment period.

Keywords: Adefovir dipivoxil, antiviral therapy, chronic hepatitis B, entecavir, lamivudine, telbivudine

Approximately 350 million people worldwide are carriers of the hepatitis B virus (HBV).[1] The majority of these carriers acquired the infection at birth or in early childhood.[2] It is estimated that 50% of male and 14% of female carriers will die from chronic hepatitis B (CHB)-related complications such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) or cirrhosis.[3] Since the introduction of routine vaccination against HBV for newborns in countries where the incidence of HBV-related complications are high, such as the Asia-Pacific region, there has been a significant decline in rates of CHB and HCC.[4]

Treatment with antiviral agents has improved the clinical outcomes of CHB patients by improving the functional capacity of remaining viable liver.[5] In recent years, the oral antiviral agents and interferon (IFN) have been the primary therapeutic choices for CHB patients.[6,7,8] There are currently five nucleos (t) ide (NUC) analogues that are commonly used in HBV infection. They are lamivudine (LAM), adefovir dipivoxil, entecavir (ETV), telbivudine (LDT), and tenofovir. In China, there are four agents that are widely available (Tenofovir is not widely available). Because of poor antiviral efficacy and adverse effects,[9,10,11] the use of adefovir dipivoxil as a single agent has decreased. Lamivudine is the only drug for treating HBV in the national health insurance program in China. The combination of lamivudine and adefovir dipivoxil has a low incidence of drug resistance,[12] and is used for many CHB patients. The beneficial effects of these agents have been clearly demonstrated.[13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20] However, there has been no consensus on the best treatment for NUC-naive CHB patients at present. There is little data available on direct comparison of these different NUC analogues. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to compare antiviral efficacy of these four agents [LAM, ETV, LDT, and the combination of LAM and adefovir dipivoxil (CLA)] and to provide further recommendations for selection of oral agents in the treatment of NUC-naive CHB patients.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study population

For this open-label trial, patients were recruited From January 2011 to December 2013 at our hospital. One hundred sixty-four consecutive NUC treatment-naive patients with HBV were enrolled in this study. These patients were all treatment naïve with regard to IFN or other immune or cytokine therapies. These patients tested negative for concurrent infectious with hepatitis A, C, D, E, and human immunodeficiency virus prior to acceptance into the trial. Patients were required to meet the Chinese National Program Chronic Hepatitis B Prevention and Control Guidelines criteria for HBV infection. The criteria are (1) hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positive, HBV DNA ≥ 105 copies/mL or HBeAg negative, HBV DNA ≥ 104 copies/mL; (2) alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels greater than two times the upper limit of normal (ULN); (3) ALT < 2 times the ULN, but with liver histology showing Knodell histology activity index ≥ 4, or inflammation and necrosis ≥ grade 2, or fibrosis ≥ grade 2.

Patients were excluded from this study if they met the following exclusion criteria: (1) autoimmune hepatitis or other diseases treated with corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, or chemotherapeutic agents; (2) a history of alcohol abuse; (3) a female with human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG)-positive pregnancy test; (4) evidence for or diagnosis of HCC before the start of the study.

The patients were divided into four groups for treatment with the four oral antiviral regimens. This open-label, head-to-head study was approved by Ethics Committee for Human Study of the First affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University and all patients provided written informed consent.

Follow-up visits

The patients were scheduled to visit the clinic during weeks 12, 24, and 52 of treatment. At every visit, patients underwent routine general examination, along with biochemical (ALT), virologic (HBV DNA levels), and serologic (HBeAg) assays.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint of the study was clinical virologic response (VR), which was defined as 1 log10/mL decrease in the serum HBV DNA level at 12 weeks of treatment compared with baseline. Secondary endpoints were HBeAg seroconversion and ALT normalization.

Laboratory tests

Serum alanine transaminase (ALT) levels were measured using an automatic biochemical analyzer (Roche, Switzerland). HBeAg levels were detected using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Kehua Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China). Serum HBV DNA levels were measured using a fluorogenic quantitative polymerase chain reaction (Zhijiang Technology Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China).

Further data analyses

After trial completion, further analyses were undertaken to explore potential relationships between early antiviral response and clinically important efficacy outcomes. Data from 164 treated patients were pooled, regardless of treatment arm. Patients were then classified according to their serum HBV DNA level at week 24: Undetectable (<103 copies/mL), detectable but ≤104 copies/mL, and >104 copies/mL, similar to the categorical analysis previously reported for resistance to lamivudine.[21] Week 52 (one-year) clinical and virologic efficacy outcomes were then analyzed based on the week-24 viral load categories.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Medians of four groups were compared using Mann–Whitney U test. The comparison of the rate used Chi-square test. A P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Enrolled patient population and patient management

A total of 164 patients participated in this trial. Of the 164 patients, nine discontinued prematurely and 155 completed the study. The reasons for premature discontinuation from the trial included noncompliance (four patients), pregnancy (two patients), and three patients were lost to follow-up.

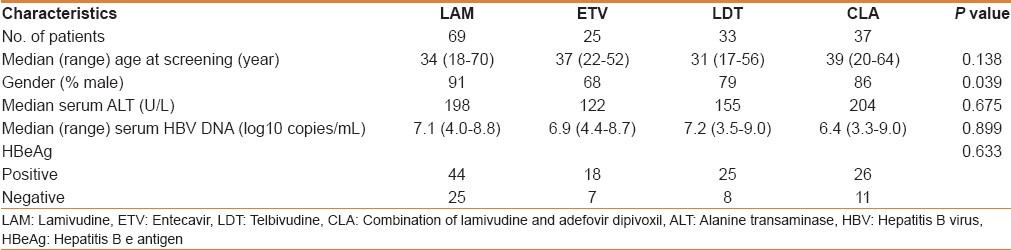

The 164 patients with postbaseline data constitute the intent-to-treat population for the study, on which the primary study analyses were conducted. Enrolled patients were mostly men and ranged in age from 17 to 70 years [Table 1]. Demographics across the four treatment groups were comparable with respect to age, duration of HBV infection, baseline HBV DNA levels, baseline ALT levels, and baseline hepatitis B serology [Table 1].

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics

Virologic responses

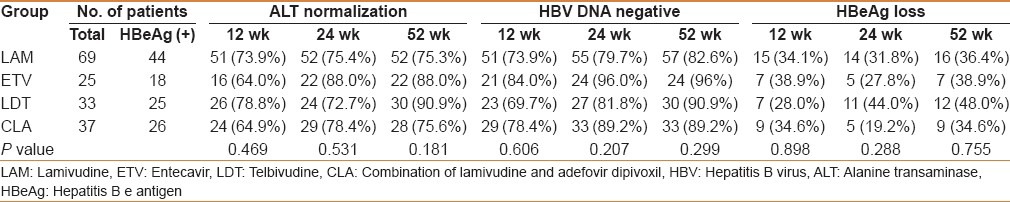

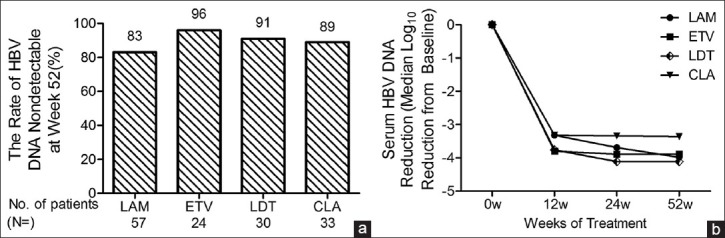

Reductions in serum HBV DNA levels were observed after the start of treatment in all treatment groups. With extended treatment time, the rate of virologic response for the four groups gradually increased. Twelve, 24, and 52 weeks after LAM, ETV, LDT, and CLA treatment, virologic response rates at 12 weeks were LAM 74%, ETV 84%, LDT 70%, and CLA 78%. Response rates at 24 weeks were LAM 80%, ETV 96%, LDT 82%, and CLA 89%. Virologic response rates at 52 weeks were LAM 83%, ETV 96%, LDT 91%, and CLA 89% [Table 2]. There were no significant differences between the four treatment groups after 12, 24, or 52 weeks of treatment [Figure 1a]. At week 52, the median reductions in serum HBV DNA levels from baseline were LAM 3.98, ETV 3.89, LDT 4.11, and CLA 3.36 log10 [Figure 1b]. There were no significant differences between the four treatment groups.

Table 2.

Virologic, biochemical, and serological responses to nucleos(t)ide treatment

Figure 1.

(a) Different treatment group at 52 weeks of treatment. Serum samples were analyzed for HBV DNA levels by fluorescent quantitative PCR. Assay lower limit of detection is 103 copies/mL. (b) Reduction in serum HBV DNA levels from baseline. Data are plotted as log10 change from baseline values. LAM, lamivudine; ETV, entecavir; LDT, telbivudine; CLA, combination of lamivudine and adefovir dipivoxil

Biochemical responses

At 12 weeks, of treatment, biochemical responses (ALT normalization) rates were LAM 74%, ETV 64%, LDT 79%, and CLA 65%. Response rates at 24 weeks were LAM 75%, ETV 88%, LDT 73%, and CLA 78%. At 52 weeks, the response rates were LAM 75%, ETV 88%, LDT 91%, and CLA 76% [Table 2]. There were no statistically significant differences among the four groups.

HBeAg loss

After 12 weeks of treatment, HBeAg loss rates were LAM 34%, ETV 39%, LDT 28%, and CLA 35%; HBeAg loss rates as 24 weeks were LAM 32%, ETV 28%, LDT 44%, and CLA 19%. Loss rates at 52 weeks were LAM 36%, ETV 39%, LDT 48%, and CLA 35% [Table 2]. There were no significant differences among the four groups.

Early antiviral response and its relationship to subsequent efficacy

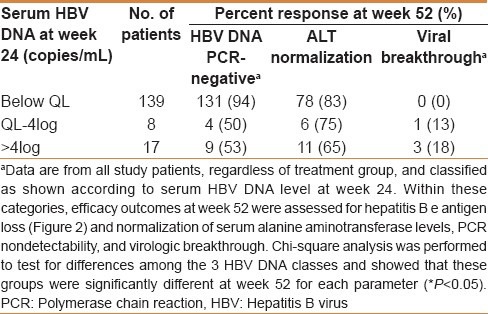

At week 24, 131 patients had undetectable serum HBV DNA (<103 copies/mL) by the quantitative PCR assay. Serum HBV DNA levels were between the quantitation limit and 104 copies/mL in eight patients, and > 104 copies/mL in 17 patients. Response rates at week 52 on clinical and virologic efficacy outcomes showed a close relationship with the degree of viral suppression at week 24, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Efficacy responses at week 52 versus serum HBV DNA level at week 24

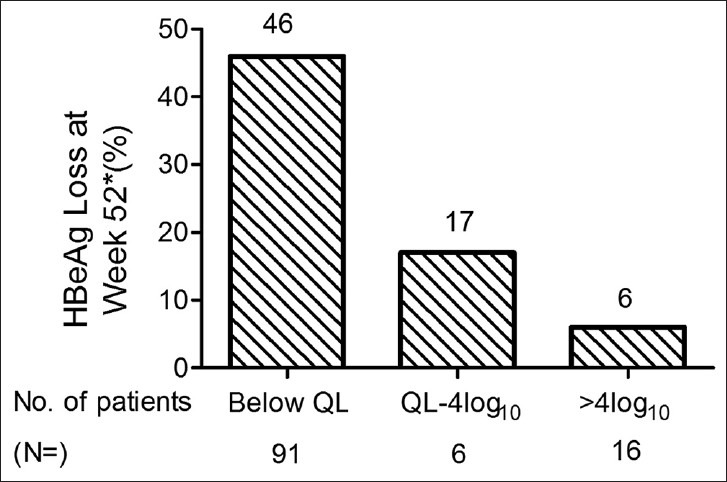

The difference in HBeAg loss rates, comparing the patients who had undetectable serum HBV DNA and those with residual viral load > 104 copies/mL at week 24, was more than sevenfold (46% vs 6%, respectively). The intermediate patient group (≥103 and ≤ 104 copies/mL) had intermediate HBeAg loss rates [Figure 2]. As shown in Table 3, for patients with undetectable serum HBV DNA at week 24, 94% of these patients maintained HBV DNA levels below the detection limit at week 52 [Table 3]. Differences in HBV DNA levels among the three groups were substantial.

Figure 2.

Reduction in hepatitis B e antigen at 52 weeks in patients grouped by HBV DNA levels at 24 weeks of treatment. *P < 0.05 by Chi-square test. QL, quantitation limit, 103 copies/mL

The rate of ALT normalization at week 52 was 83% of patients who had undetectable serum HBV DNA at week 24, ranging down to 65% of patients with viral load > 104 at week 24. However, there were no statistical differences among the three groups [Table 3].

No cases of viral breakthrough were seen at week 52 in patients with viral load below the detection limit at week 24. In contrast, viral breakthrough rates of 13%–18% were seen at week 52 in patients with viral DNA levels above the quantitation limit [Table 3]. Chi-square analysis was performed to test for differences among the three HBV DNA groups and showed that these classes were significantly different at week 52 for viral breakthrough and HBV DNA PCR-negative (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The results of this head-to-head, one-year trial allowed a direct comparison of these four different treatments LAM, ETV, LDT, and CLA. Antiviral effects were evident for all four treatment groups. At week 52, the percentage of patients with undetectable serum HBV DNA were LAM 83%, ETV 96%, LDT 91%, and CLA 89%. HBeAg loss was proportionally greatest at one year for each therapy compared to previous time points (LAM 36%, EVT 39%, LDT 48%, and CLA 35%). At week 52, the median reduction in HBV DNA levels from baseline were (log10) LAM 3.98, ETV 3.89, LDT 4.11, and CLA 3.36. However, there were no significant differences among all four groups for any of these responses.

Short-term studies have shown that IFN-based therapy was modestly effective in inducing HBeAg loss or seroconversion (30%–40%) in HBeAg-positive patients.[22,23] In therapy with direct antiviral NUC analogues, the serological response was lower than that of IFN-based therapy.[24] The predicted trends of our study were similar to the references,[25] but the response rates were higher.

The reasons for these differences may lie in the following factors: (1) The HBV DNA detection limit of our study was 1000 copies/mL; however, the detection limit for the other studies was 300 copies/mL. (2) It may be due to differences in the Chinese HBV genotype from the genotypes in other populations. (3) The study was not randomized, so the baseline ALT values were higher than values in the other studies and the age range in this study included some younger patients. (4) The small sample size and short observation time in this study. The posttreatment durability of HBeAg responses observed during NUC analogue therapy is presently unknown. Current guidelines indicate that patients should receive a minimum of one year of NUC treatment and should be HBeAg negative for at least 3–6 months before treatment is discontinued.[26,27] Ninety percent of patients in this trial were enrolled into a 2-year extension study, in which the posttreatment durability of the effects of different NUC analogues on HBeAg will be studied.

Although the HBV DNA levels were significantly decreased in all four groups of patients at 12, 24, and 52 weeks, there were no differences among the four groups. These results indicated that (1) LAM, ETV, LDT, and CLA exhibited similar potential in inhibiting HBV DNA replication in a one-year trial; and (2) the role of these four therapies in inhibiting HBV DNA replication caused a parallel change in loss of HBeAg. The rate of HBeAg seroconversion may decrease the morbidity and mortality associated with CHB. Loss of HBeAg and seroconversion to anti-HBeAg will ensure that these benefits are sustained even after therapy is discontinued. Therefore, a long posttreatment observation period for anti-HBeAg will be a valuable measure in evaluating the long-term antiviral efficacy of these agents.

The analyses of the patient response data from this study support the concept that in HBV patients, early viral suppression was linked to later clinical and virologic efficacy. Normalization of serum ALT levels and HBeAg clearance were greatest at one year in the group of patients who had the greatest antiviral responses at 6 months of treatment. In addition, viral breakthrough was zero at one year in patients with serum HBV DNA levels below the QL (<103 copies/mL) at week 24. Conversely, HBeAg clearance at one year was low, ALT normalization rate was modest, and viral breakthrough was most prevalent in the patient subgroup whose serum HBV DNA levels were above 104 at week 24. The clear relationship between degree of early HBV suppression and subsequent clinical efficacy supports an emerging rationale for maximizing early viral suppression as a strategy for optimizing longer-term clinical outcomes in HBV patients. Larger population studies will be needed to confirm these observations.

A significant advantage of this study was the direct comparison of the four treatments over a one-year period under the same conditions. However, we acknowledge that there were several limitations to this study, such as a small number of patients, a short observation period, and a lack of testing for drug resistance. This may limit the ability to extrapolate these results to larger or different populations of patients. In conclusion, all four treatments administered in this study (LAM, ETV, LDT, and CLA) showed no statistically significant differences when given to NUC-naïve patients.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yuen MF, Lai CL. Treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Lancet Infect Dis. 2001;1:232–41. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00118-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai CL, Yuen MF. The natural history and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: A critical evaluation of standard treatment criteria and end points. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:58–61. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-1-200707030-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang MH, Shau WY, Chen CJ, Wu TC, Kong MS, Liang DC, et al. Hepatitis B vaccination and hepatocellular carcinoma rates in boys and girls. JAMA. 2000;284:3040–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.23.3040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang MH, Chen TH, Hsu HM, Wu TC, Kong MS, Liang DC, et al. Prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma by universal vaccination against hepatitis B virus: The effect and problems. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7953–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koda M, Nagahara T, Matono T, Sugihara T, Mandai M, Ueki M, et al. Nucleotide analogs for patients with HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma increase the survival rate through improved liver function. Intern Med. 2009;48:11–7. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Association for the Study of Liver. EASL clinical practical guidelines: Management of alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2012;57:399–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liaw YF, Leung N, Guan R, Lau GK, Merican I, McCaughan G, et al. Asian-Pacific consensus update working party on chronic hepatitis B. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: A 2005 update. Liver Int. 2005;25:472–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.01134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lok AS, McMahon BJ AASLD (American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases) AASLD Practice Guidelines. Chronic hepatitis B: Update of therapeutic guidelines. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2004;13:150–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartono JL, Aung MO, Dan YY, Gowans M, Lim K, Lee YM, et al. Resolution of adefovir-related nephrotoxicity by adefovir dose-reduction in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:710–9. doi: 10.1111/apt.12251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcellin P, Chang TT, Lim SG, Tong MJ, Sievert W, Shiffman ML, et al. Adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:808–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schiff ER, Lai CL, Hadziyannis S, Neuhaus P, Terrault N, Colombo M, et al. Adefovir dipivoxil therapy for lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B in pre- and post-liver transplantation patients. Hepatology. 2003;38:1419–27. doi: 10.1016/j.hep.2003.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sung JJ, Lai JY, Zeuzem S, Chow WC, Heathcote EJ, Perrillo RP, et al. Lamivudine compared with lamivudine and adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2008;48:728–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bryant ML, Bridges EG, Placidi L, Faraj A, Loi AG, Pierra C, et al. Antiviral L-nucleosides specific for hepatitis B virus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:229–35. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.1.229-235.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai CL, Chien RN, Leung NW, Chang TT, Guan R, Tai DI, et al. A one-year trial of lamivudine for chronic hepatitis B. Asia Hepatitis Lamivudine Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:61–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807093390201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai CL, Shouval D, Lok AS, Chang TT, Cheinquer H, Goodman Z, et al. Entecavir versus lamivudine for patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1011–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lai CL, Yuen MF. Chronic hepatitis B--new goals, new treatment. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2488–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0808185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liaw YF, Chien RN, Yeh CT, Tsai SL, Chu CM. Acute exacerbation and hepatitis B virus clearance after emergence of YMDD motif mutation during lamivudine therapy. Hepatology. 1999;30:567–72. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marcellin P, Heathcote EJ, Buti M, Gane E, de Man RA, Krastev Z, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus adefovir dipivoxil for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2442–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Standring DN, Bridges EG, Placidi L, Faraj A, Loi AG, Pierra C, et al. Antiviral beta-L-nucleosides specific for hepatitis B virus infection. Antivir Chem Chemother. 2001;12(Suppl 1):119–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuen MF, Yuan HJ, Wong DK, Yuen JC, Wong WM, Chan AO, et al. Prognostic determinants for chronic hepatitis B in Asians: Therapeutic implications. Gut. 2005;54:1610–4. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.065136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuen MF, Sablon E, Hui CK, Yuan HJ, Decraemer H, Lai CL. Factors associated with hepatitis B virus DNA breakthrough in patients receiving prolonged lamivudine therapy. Hepatology. 2001;34:785–91. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.27563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lau GK, Piratvisuth T, Luo KX, Marcellin P, Thongsawat S, Cooksley G, et al. Peginterferon Alfa-2a HBeAg-Positive Chronic Hepatitis B Study Group. Peginterferon Alfa-2a, lamivudine, and the combination for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2682–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin SM, Sheen IS, Chien RN, Chu CM, Liaw YF. Long-term beneficial effect of interferon therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 1999;29:971–5. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liaw YF. Impact of therapy on the outcome of chronic hepatitis B. Liver Int. 2013;33(Suppl 1):111–5. doi: 10.1111/liv.12057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liaw YF, Chu CM. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2009;373:582–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liaw YF, Leung N, Guan R, Lau GK, Merican I Asian-Pacific Consensus Working Parties on Hepatitis B. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: An update. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:239–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.03037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lok AS, McMahon BJ Practice Guidelines Committee. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) Chronic hepatitis B: Update of recommendations. Hepatology. 2004;39:857–61. doi: 10.1002/hep.20110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]