Abstract

Sclerosing mesenteritis (SM) is a rare, benign inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology, affecting the membranes of the digestive tract that involves lymphoplasmacytic inflammation, fat necrosis, and fibrosis of the mesentery. We report a child patient with a history of recurrent abdominal pain and fever who was found to have an intra-abdominal mass suspicious for malignancy. A tissue biopsy revealed the diagnosis of SM associated with IgG4-related systemic disease. The patient is currently maintained on 5 mg prednisone daily and no recurrence of symptoms was noted during the 24-month follow-up period. We emphasize, therefore, that SM can present clinical challenges and the presence of SM should cue clinicians to search for other coexisting autoimmune disorders that can have various outcomes.

Keywords: IgG4-related systemic disease, retroperitoneal fibrosis, sclerosing mesenteritis

Sclerosing mesenteritis (SM) is a chronic, nonspecific inflammatory and fibrotic process involving the adipose tissue of the small bowel mesentery. This rare disease was first reported by Durst et al.[1] SM commonly affects small bowel mesentery and less commonly large bowel mesentery and the omentum with rare involvement of the pancreas and retroperitoneum.[2] SM can present serious clinical challenges for clinicians, as it can be mistaken for lymphoma, vasculitis, granulomatous diseases, and carcinomatosis.[3]

The present paper describes a seven year-old girl who presented with anorexia, weight loss, chronic diarrhea, and abdominal pain, mimicking Crohn's disease and abdominal tuberculosis. She underwent exploratory laparotomy for a strong suspicion of lymphoma but tissue biopsy revealed SM associated with IgG4-related systemic disease (IgG4-RSD). A review of the literature is also provided.

CASE REPORT

A seven year-old girl was admitted with a one month history of colicky abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and fever. For three years, she had recurrent fever, vomiting, and diarrhea, which was fully investigated including colonoscopy and was eventually diagnosed as abdominal tuberculosis. The patient was commenced on antituberculosis treatment for 9 months but showed no improvement. One year later, a further admission with similar symptoms and signs warranted a computed tomography (CT) scan, which demonstrated a stricture in the terminal ileum suspecting Crohn's disease. She did not respond to steroid, azathioprine, and infliximab. Family history was noncontributory for gastrointestinal or autoimmune diseases. There was no history of night sweat, skin rash, joint pain, or recent travel. The patient had normal developmental milestones. On admission to hospital, the physical examination revealed evidence of growth retardation. No hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, or skin rashes were noted. Other systemic examination was unremarkable. The laboratory findings revealed normal hemoglobin level, white blood cell count, and platelet count. The electrolytes, coagulation study and liver function test results were normal. Serum amylase, lipase, lactate dehydrogenase, and uric acid levels were normal. C-reactive protein (CRP) was 236 (normal: <1.0 mg/dL) and serum albumin was 23 (normal: 35-55 g/L). Her serums IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 levels were normal, whereas serum IgG4 was 149 (normal 8-140 mg/dL). Esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy revealed normal mucosa, and no ulcerations were detected. Biopsies showed no evidence of Crohn's disease or abdominal tuberculosis. Abdominal CT scan with contrast revealed evidence of a subtle attenuation in the mesentery with diffuse lymphadenopathy [Figure 1]. It showed no abscesses or fistulae but there was significant fat stranding and inflammation in mesentery of the terminal ileum. She underwent exploratory laparotomy for a strong suspicion of lymphoma based on CT scan abnormalities. The operative findings showed extensive intraperitoneal adhesions, mesenteric lymphodenopathy, and inflamed omentum. The entire small intestine was normal. Histopathological biopsies from lymph nodes and the peritoneal membrane revealed extensive perinodal fibrosis, focal dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and prominent lymphoid follicular hyperplasia in lymph nodes. Immunohistochemistry using antibodies to IgG and IgG4 showed that the plasma cells are predominantly of IgG4 phenotype [Figures 2–4].

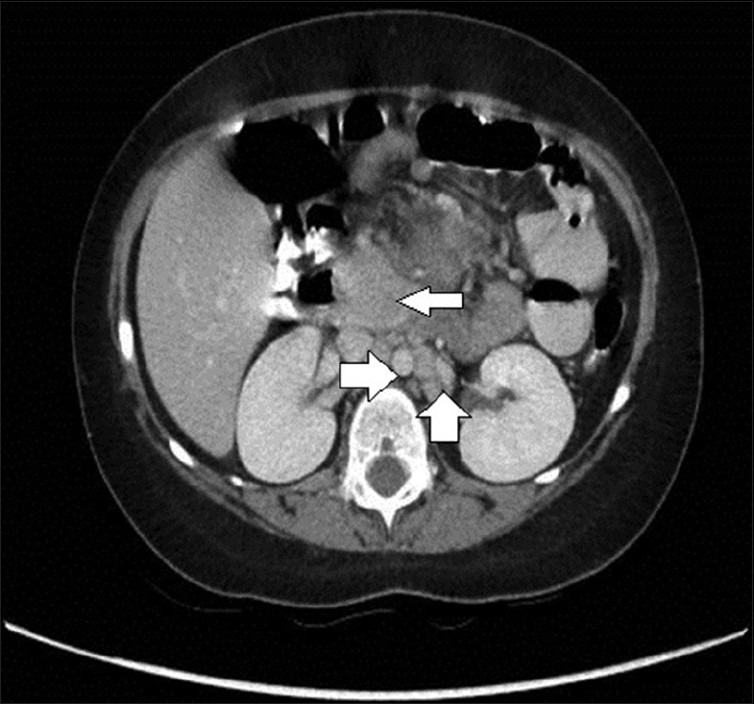

Figure 1.

CT scan of abdomen demonstrating a mass of confluent lymphadenopathy in the center of the abdomen at the root of the mesentery (narrow white arrow). There are significant enlarged retroperitoneal lymphadenopathies (bold white arrows)

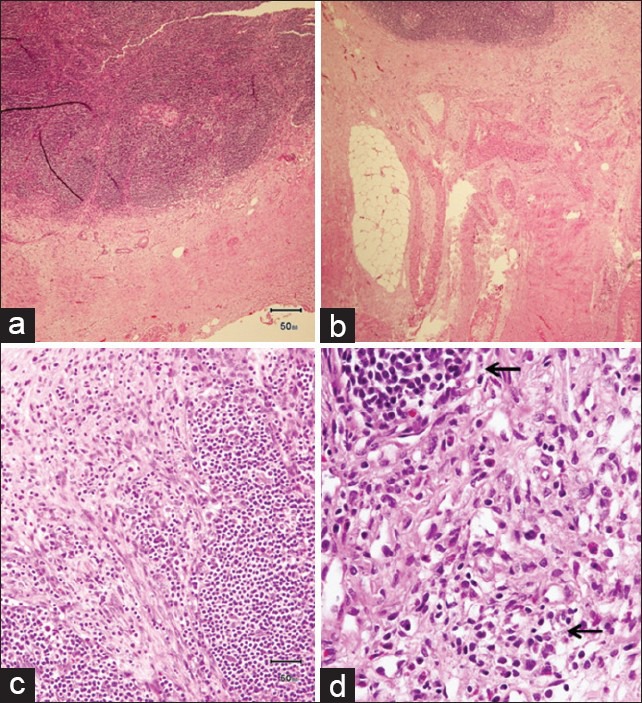

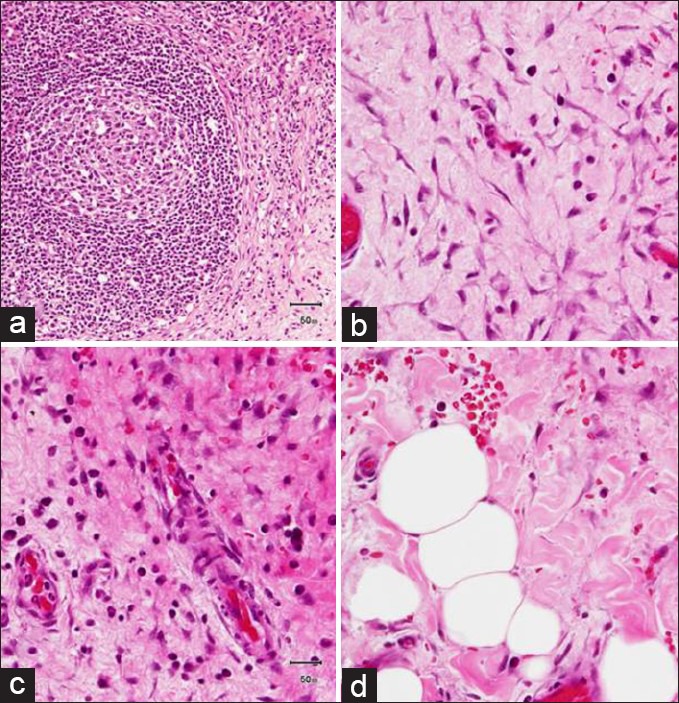

Figure 2.

Histopathology specimen from lymph nodes and omentum showed extensive perinodal fibrosis (a, b) with the presence of focal dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (arrows) and loose fibrovascular proliferation infiltrating adipose tissue (c, d)

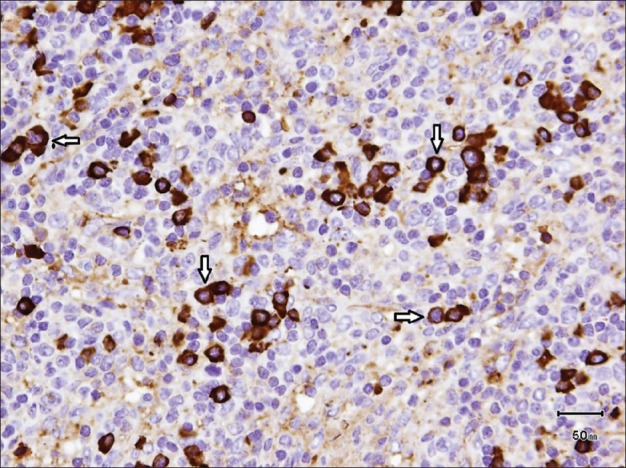

Figure 4.

IgG4 immunohistochemical staining showed predominant IgG4-positive plasma cells (white arrows)

Figure 3.

Histopathology specimen from lymph nodes showing prominent lymphoid follicular hyperplasia (a) and omentum showed extensive perinodal fibrosis presence of focal dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (arrows) and loose fibrovascular proliferation infiltrating adipose tissue (b-d)

Multidisciplinary consultations were carried out in the presence of involved clinicians and a pathologist. A diagnosis of IgG4-related sclerosing mesenteritis was made and the child was treated with colchicine, esomeprazole, prednisolone, and azathioprine. At 6 months followup from the onset of treatment, she was completely asymptomatic, mesenteric mass was reduced, and her laboratory investigations remained normal. She developed pericardial effusion which responds to high dose of prednisolone. The patient is currently maintained on 5 mg prednisone daily and there is no recurrence of symptoms noted during the 24-month followup period.

DISCUSSION

SM is a rare, adult-onset disease with progressive inflammation involving the small intestinal mesentery leading to fibrosis and bowel obstruction.[4]

IgG4-related systemic disease (IgG4-RSD) is a recently recognized systemic condition characterized by unique pathological features that affect a wide variety of organs.[5] The histopathology identified within affected organs was identical to that found in the pancreas: Extensive lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, abundant IgG4 plasma cells, and fibrosis.[5]

Viswanathan et al.[6] described 17 pediatric cases with SM, with no gender predominance and age at diagnosis averaging 6.5 years. The exact etiology of SM is unknown. Various pathological mechanisms of SM include previous surgery, trauma, hypoxia, allergy, infection, and autoimmunity.[4] Clinical features of SM are nonspecific and abdominal pain is the most common presentation.[7] Our patient presented with recurrent fever and abdominal pain. However, patients may present asymptomatically with an incidental diagnosis. Other clinical features of SM include vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, anorexia, weight loss, fatigue, fever of unknown origin, ascites, and pericardial effusion.[8]

Establishing the diagnosis of SM is both a clinical and histologic challenge. Radiographic means (contrast studies and CT) are nonspecific and the diagnosis can only be made after operative assessment and generous biopsy. Even the histopathological diagnosis of SM would be cautioned, because the possibility of an unsampled associated malignancy is hard to rule out, especially because the operative findings could simulate a neoplastic process. Immunohistochemistry of our patient's biopsy shows that the plasma cells are predominantly of IgG4 phenotype. Our case is IgG4-related sclerosing disease involving the mesentery and abdominal lymph nodes because the histopathology shows lymphoid hyperplasia; lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate; high number of IgG4+ Plasma cell (ratio of IgG4+ Plasma cell/IgG+ Plasma cell is 52%). However, extrapancreatic lesions of IgG4-related disease include the following: Retroperitoneal fibrosis, sclerosing mesenteritis, and sclerosing mediastinitis with abundance of IgG4+ plasma cell. The data of Chen et al.[9] taken together with the observation in our patient suggest that SM is a rare fibroinflammatory disorder that has been reported to be associated with IgG4-RSD. Additionally, the data of Belghiti et al.[10] taken together with the observation in our patient suggests that infiltrating plasma cells expressing IgG4 is a prominent feature of the inflammatory infiltrate of some patients with SM. Desmoid tumor and peritonitis are differential diagnoses of IgG4-related SM. Desmoid tumor is excluded because lymphoid hyperplasia and lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates are not features of desmoid tumor. In addition, immunohistochemistry stainings are negative for C-kit, BCL2, and beta-catenin.

No specific guidelines regarding the management of SM exist and various medical and surgical modalities have been tried. The treatment of SM is tailored to the patient's individual symptoms and accompanying complications. In one study conducted by Akram et al.[4] of 92 patients, 52% of patients did not receive any treatment, 26% were treated with medical therapy alone, 13% with surgery alone, and 9% with both surgical and medical therapy. In some studies in adult patients, good response was achieved with the use of various medications such as steroids, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, tamoxifen, progesterone, and colchicines.[11] IgG4-related manifestations are often steroid responsive and determining the degree of fibrosis may be important for predicting steroid response.[9] However, surgical exploration for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes has been reported with all the children having some form of surgical intervention with only two cases not having actual tissue resection.[6] Resection or debulking probably has a role in alleviating symptoms but may not help in prevention of disease progression.[6] Poor outcome has been demonstrated if the mesenteric lesion encases vital vasculature or extensive resection causes short bowel syndrome. If treatment is successful, case series document remission at 15 years.[9]

As in our case, steroids may be useful to relieve the symptoms. Surgical resection of the involved mesentery was discussed with the family but they refused it. Although the long-term use of steroids in our patient can be debated, we believe it is safer to maintain our patient on steroids because of failure of other immunosuppressive agents and steroids would prevent relapses.

In summary, our case illustrates the following: (1) the diagnosis of SM can be difficult to make preoperatively, especially when other conditions, such as Crohn's disease, abdominal tuberculosis, and lymphoma exist; (2) the presentation of SM with IgG4-RSD is unusual; (3) diagnosis is best made through histopathological examination from excision biopsy; and (4) the presentation of SM with IgG4-RSD emphasizes the need for more research to help in understanding the etiology

CONCLUSION

SM is a rare, benign inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology, affecting the membranes of the digestive tract. SM poses great diagnostic challenge due to its nonspecific clinical and diagnostic findings. However, the diagnostic conundrum was resolved by surgery and the histological examination of the specimen. We suggest that any pediatric patient who presents with symptoms of SM be evaluated for IgG4-RSD as a potential association of the disease.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Durst AL, Freund H, Rosenmann E, Birnbaum D. Mesenteric panniculitis: Review of literature and presentation of cases. Surgery. 1977;81:203–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phillips RH, Carr RA, Preston R, Pereira SP, Wilkinson ML, O’Donnell PJ, et al. Sclerosing mesenteritis involving the pancreas: Two cases of a rare cause of abdominal mass mimicking malignancy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:1323–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ege G, Akman H, Cakiroglu G. Mesenteric panniculitis associated with abdominal tuberculous lymphadenitis: A case report and review of the literature. Br J Radiol. 2002;75:378–80. doi: 10.1259/bjr.75.892.750378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akram S, Pardi DS, Schaffner JA, Smyrk TC. Sclerosing mesenteritis: Clinical features, treatment, and outcome in ninety-two patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:589–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamisawa T, Funata N, Hayashi Y, Eishi Y, Koike M, Tsuruta K, et al. A new clinicopathological entity of IgG4-related autoimmune disease. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:982–4. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1175-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viswanathan V, Murray KJ. Idiopathic sclerosing mesenteritis in paediatrics: Report of a successfully treated case and a review of literature. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2010;8:5. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-8-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheikh RA, Prindiville TP, Arenson D, Ruebner BH. Sclerosing mesenteritis seen clinically as pancreatic pseudotumour: Two cases and a review. Pancreas. 1999;18:316–21. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199904000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuff R, Landercasper J, Schlack S. Sclerosing mesenteritis. Surgery. 2001;129:509–10. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.106425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen TS, Montgomery EA. Are tumefactive lesions classified as sclerosing mesenteritis a subset of IgG4-related sclerosing disorders? J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:1093–7. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.057869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belghiti H, Cazals-Hatem D, Couvelard A, Guedj N, Bedossa P. Sclerosing mesenteritis: Can it be a IgG4 dysimmune disease? Ann Pathol. 2009;29:468–74. doi: 10.1016/j.annpat.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bala A, Coderre SP, Johnson DR, Nayak V. Treatment of sclerosing mesenteritis with corticosteroids and azathioprine. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15:533–5. doi: 10.1155/2001/462823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]