Abstract

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–positive breast cancers are currently treated with trastuzumab, an anti-HER2 antibody. About 30% of these tumors express a group of HER2 fragments collectively known as p95HER2. Our previous work indicated that p95HER2-positive tumors are resistant to trastuzumab monotherapy. However, recent results showed that tumors expressing the most active of these fragments, p95HER2/611CTF, respond to trastuzumab plus chemotherapy. To clarify this discrepancy, we analyzed the response to chemotherapy of cell lines transfected with p95HER2/611CTF and patient-derived xenografts (n = 7 mice per group) with different levels of the fragment. All statistical tests were two-sided. p95HER2/611CTF-negative and positive tumors showed different responses to various chemotherapeutic agents, which are particularly effective on p95HER2/611CTF-positive cells. Furthermore, chemotherapy sensitizes p95HER2/611CTF-positive patient-derived xenograft tumors to trastuzumab (mean tumor volume, trastuzumab alone: 906mm3, 95% confidence interval = 1274 to 538 mm3; trastuzumab+doxorubicin: 259mm3, 95% confidence interval = 387 to 131 mm3; P < .001). This sensitization may be related to HER2 stabilization induced by chemotherapy in p95HER2/611CTF-positive cells.

The receptor tyrosine kinase HER2 is overexpressed in approximately 20% of breast cancers. HER2-positive breast cancers are currently treated with monoclonal antibodies against the extracellular domain of the receptor, such as trastuzumab, in combination with different regimens of classical chemotherapy that interact, additively or synergistically, with the antibody (1). Despite its remarkable effectiveness, tumors frequently become resistant to this combination and resume their malignant progression (2).

About 30% of HER2-positive breast cancers express a series of HER2 carboxy-terminal fragments collectively known as HER2 CTFs or p95HER2 (3). An initial study showed that p95HER2-expressing tumors are resistant to the treatment with trastuzumab (4).

One of the p95HER2 fragments, the so-called 100–115kDa p95HER2 or 611CTF is highly oncogenic because it spontaneously homodimerizes into a constitutively active form (5). The current availability of specific antibodies allows the detection of p95HER2/611CTF in clinically relevant samples (6,7). Preliminary analyses of samples from the GeparQuattro clinical trial showed, in contrast with Scaltriti et al. (4), that the expression of p95HER2/611CTF was associated with better response to neoadjuvant therapy that included trastuzumab (8). A difference between these studies was that more than half (56%) of the patients included in the initial study were treated with trastuzumab alone (4). In contrast, patients from the GeparQuattro trial received trastuzumab plus anthracycline-taxane-based chemotherapy (8).

To investigate the effect of p95HER2/ 611CTF expression on the response to chemotherapy, we used immunohistochemistry, transcriptomic analysis, proliferation assays, flow cytometry and confocal microscopy, as well as experiments with patient-derived xenograft mice. Written informed consent for the use of the samples was obtained from all patients who provided tissue. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 software. Differences between means were estimated using the Student’s t test. All statistical tests were two-sided. Data represent results from three or more independent experiments. Additional details are given in the Supplementary Methods (available online).

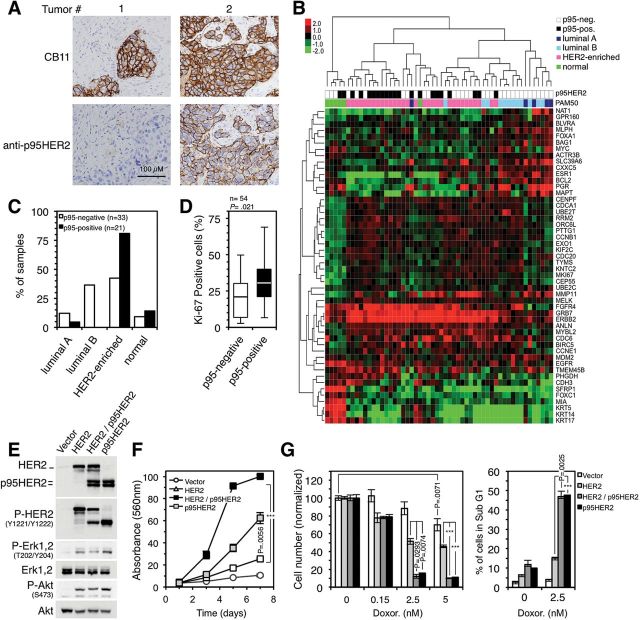

First we determined the levels of p95HER2/611CTF (Figure 1A), as well as the subtype of breast cancer according to the levels of expression of selected genes (Figure 1B), of a series of 54 HER2-positive samples. Less than half (42.42%) of the p95HER2/611CTF-negative tumors were HER2-enriched (Figure 1C). In contrast, virtually all the p95HER2/611CTF-positive samples expressed high levels of HER2 mRNA (Figure 1B), and most of them (80.95%) belonged to the HER2-enriched subtype (Figure 1C). Of note, a recent report showed that, compared with other subtypes, HER2-enriched tumors tended to respond better to therapeutic regimens that include chemotherapy and trastuzumab (9). Furthermore, the percentage of cells expressing nuclear Ki-67 was statistically significantly higher in p95HER2/611CTF-positive breast cancer samples (P = .021) (Figure 1D), and high levels of this proliferation marker predict response to chemotherapy (10).

Figure 1.

Characterization of p95HER2/611CTF-positive breast cancers and effect of p95HER2/611CTF expression on sensitivity to chemotherapy. A) Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) and p95HER2/611CTF protein expression were evaluated in a series of breast cancer samples by immunohistochemistry. Two representative examples are shown. Scale bar, 100 µm, in all panels. B) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the samples analyzed in A according to the levels of expression of 50 selected genes using the Counter platform. All tumors were assigned to an intrinsic molecular type of breast cancer (Luminal A, Luminal B, HER2-enriched, and Basal-like) (18). C) Percentage of p95HER2/611CTF-negative and p95HER2/611CTF-positive samples in each molecular type of breast cancer. D) The expression of the Ki-67 proliferation marker was determined in the samples analyzed in A. Box plots show the percentage of Ki-67-positive cells in p95HER2/611CTF-negative and -positive samples. Lower and higher whiskers indicate 10th and 90th percentiles, respectively; lower and higher edges of box indicate 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively; the inner line in the box indicates 50th percentile. p95HER2/611CTF-negative and -positive samples were compared using the two-sided Student’s t test. E) MCF10A cells stably transduced with an empty viral vector or the same vector encoding HER2 or p95HER2/611CTF, individually or together, were lysed and the cell lysates analyzed by western blot with the indicated antibodies. The bands corresponding to HER2 and p95HER2/611CTF are indicated in the upper panel. Results are representative of three independent experiments. F) The same cells as in (E) were seeded, and cell number was assessed at the indicated time points by the crystal violet staining assay. Error bars correspond to 95% confidence intervals of three independent experiments. P values were calculated using the two-sided Student’s t test; ***P < .001. G) The same cell lines as in (E) were treated with different concentrations of doxorubicin for one week. Cell number was estimated with the crystal violet staining assay. The sub-G1 cell fraction was determined through cell cycle analysis, and it was expressed as percentages of the whole-cell population. Error bars correspond to 95% confidence intervals of three independent experiments, each containing triplicates. P values were calculated using the two-sided Student’s t test; ***P < .001. HER2 = human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

The analysis of different breast cancer cell lines indicated that p95HER2/611CTF expression induces sensitivity to the anthracycline doxorubicin (Supplementary Figure 1, available online). To determine if there is an association between the expression of p95HER2/611CTF and an increased sensitivity to chemotherapy, we generated p95HER2/611CTF-expressing cells (Figure 1E). In agreement with the high percentage of Ki-67-positive cells in p95HER2/611CTF-positive breast cancers (Figure 1D), expression of p95HER2/611CTF, alone or along with HER2, accelerated cell proliferation (P = .0056 alone, P < .001 in combination) (Figure 1F). In consonance with this result, p95HER2/611CTF statistically significantly increased the sensitivity to doxorubicin and the induction of apoptotic cell death (P < .001 for cells expressing HER2 and p95HER2/611CTF compared with those expressing HER2, after doxorubicin treatment) (Figure 1G). Thus, p95HER2/611CTF-positive cells show a higher sensitivity to DNA-damaging chemotherapy compared with p95HER2/ 611CTF-negative cells.

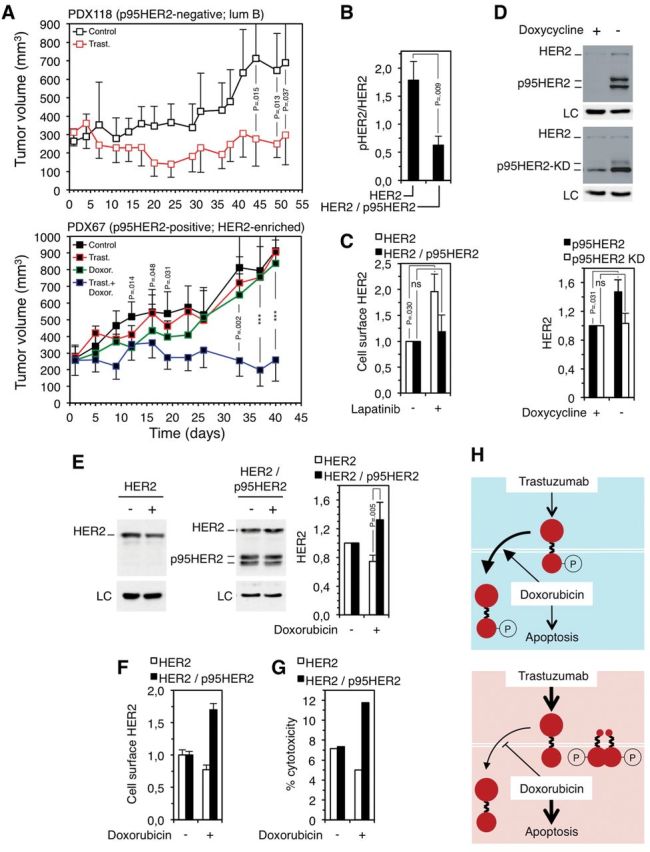

To analyze the effect of chemotherapy in vivo, we used two recently established breast cancer patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) (11). Trastuzumab impaired the growth of the p95HER2/611CTF-negative PDX118 (mean tumor volume, trastuzumab: 298mm3, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 459 to 137 vs control: 689mm3, 95% CI = 938 to 439, P = .037) (Figure 2A, upper panel) while it did not affect the growth of the p95HER2/611CTF-positive PDX67 (mean tumor volume, day 40: 906mm3, 95% CI = 1274 to 538) (Figure 2A, lower panel). Treatment with doxorubicin slightly inhibited the growth of the p95HER2/611CTF-positive PDX67, although the effect was only statistically significant during a limited period of time (P = .014 at day 12, P = .048 at day 16, and P = .031 at day 19) (Figure 2A, lower panel). Unexpectedly, treatment with doxorubicin sensitized PDX67 to trastuzumab, showing that p95HER2/611CTF-positive tumors are targeted by the trastuzumab-doxorubicin combination (mean tumor volume, day 40: 259mm3, 95% CI = 387 to 131; P < .001) (Figure 2A, lower panel).

Figure 2.

Effect of trastuzumab and doxorubicin on the growth of p95HER2/611CTF-negative and -positive patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) and effect of doxorubicin on human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) levels in p95HER2/611CTF-negative and -positive cells. A) Patient-derived xenografts obtained from two HER2-positive breast cancers not expressing (upper panel) (PDX118) or expressing (lower panel) (PDX67) p95HER2/611CTF (11) were treated as indicated (n = 7 in each group). Error bars correspond to 95% confidence intervals. P values were calculated using the two-sided Student’s t test; ***P < .001 (PDX67; control mice vs mice treated with doxorubicin at days 12-19; mice treated with trastuzumab alone vs mice treated with trastuzumab plus doxorubicin at days 33-40). PDX118 and PDX67 belong to the luminal B and HER2-enriched subgroups, according to the gene signatures described in Figure 1B. B) MCF10A cells expressing HER2 or HER2 and p95HER2/611CTF were analyzed by western blot. The signals corresponding to HER2 or phospho-HER2 (pHER2) were quantified. Error bars correspond to 95% confidence intervals of four independent experiments. P values were calculated using the two-sided Student’s t test. C) The same cells as in (B) were treated with 1µM lapatinib for 48 hours. Then, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry with antibodies against the extracellular domain of HER2. The results from three independent experiments are expressed as average fold increase relative to untreated control. Error bars correspond to 95% confidence intervals of four independent experiments. P values were calculated using the two-sided Student’s t test. D) MCF7 Tet-Off cells stably transfected with constructs encoding wild-type p95HER2/611CTF (upper blot) or p95HER2/611CTF bearing a mutation (K767) that inactivates its kinase domain (lower blot), p95HER2/611CTF KD, under the control of a doxycycline regulated promoter, were cultured with or without doxycycline. Then, cells were lysed and cell lysates analyzed by western blot. The signal corresponding to full-length HER2 was quantified from four independent experiments and averages and 95% confidence intervals are shown. P values were calculated using the two-sided Student’s t test. E) The same cells as in (B) were treated with 1.25 nM doxorubicin for one week, lysed and cell lysates analyzed by western blot; the signals corresponding to full-length HER2 were quantified from three independent experiments and expressed as average fold increase relative to untreated control ± SD. P values were calculated using the two-sided Student’s t test. F) The same cells as in (B) were treated with 1.25 nM doxorubicin for one week and analyzed by flow cytometry with antibodies against the extracellular domain of HER2. Error bars correspond to 95% confidence intervals of four independent experiments. G) Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) was analyzed as described in (15), after treating target cells with or without 1.25 nM doxorubicin for one week. H) Schematic drawing showing the effect of the combination of trastuzumab and doxorubicin on p95HER2/611CTF-negative cells (blue background) or p95HER2/611CTF-positive cells (red background). HER2 is represented by two big filled red circles linked by a broken line, the p95HER2/611CTF constitutively active fragment is represented by a small filled red circle linked with a broken line to a big one. Treatment with doxorubicin induces apoptosis more efficiently in p95HER2/611CTF-positive cells and, additionally, destabilizes phospho-HER2 and stabilizes HER2 in p95HER2/611CTF-negative and -positive cells, respectively. LC = loading control; HER2 = human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; ns = statistically non-significant

Treatment of cell cultures established from the PDXs with doxorubicin plus trastuzumab did not show any cooperative effect between the two drugs in vitro (Supplementary Figure 2, available online). This result indicated that, despite using NOD-SCID, which have impaired natural killer (NK) cell function, the effect observed in vivo (Figure 2A) could be because of the known ability of trastuzumab to induce antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) (12,13). In fact, previous reports have shown ADCC in this immunodeficient mouse strain (14).

Compared with the unphosphorylated form, active phosphorylated HER2 is rapidly endocytosed and degraded. Accordingly, inhibition of the phosphorylation of HER2 leads to the accumulation of HER2 at the cell surface and, as a consequence, to enhanced trastuzumab-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (15). The expression of p95HER2/611CTF was associated with reduced levels of the phosphorylated form of HER2 in different cellular contexts (P = .009) (Figure 2B; Supplementary Figure 3, available online; see also phosphorylated HER2 in Figure 1E), indicating that p95HER2/611CTF reduces the phosphorylation of full-length HER2 and, hence, stabilizes it. Analysis of cells expressing p95HER2/611CTF or, as control, a kinase-dead p95HER2/611CTF mutant, under the control of a promoter regulated by doxycycline, confirmed that p95HER2/611CTF increases the levels of full-length HER2 (P = .031) (Figure 2D). Furthermore, treatment with lapatinib, an inhibitor of the phosphorylation of HER2, statistically significantly increased the levels of cell surface HER2 in cells not expressing p95HER2/611CTF (P = .030). In expressing cells, where the phosphorylation of HER2 is already inhibited by p95HER2/611CTF, lapatinib had little effect on the level of cell surface HER2 (Figure 2C).

Since the activation of HER2 and, hence, its stability can be modified by p95HER2/611CTF, we hypothesized that HER2 levels may be differentially affected in p95HER2/611CTF-positive and -negative cells by chemotherapy. Supporting this hypothesis, treatment with doxorubicin resulted in increased levels of HER2 in cells expressing p95HER2/611CTF but not in nonexpressing cells (P = .005) (Figure 2E). Concordant results were observed when analyzing the levels of cell surface HER2 (Figure 2F). Although the mechanism behind this differential effect is unknown, it is not likely because of a direct binding of doxorubicin to HER2. As expected, the increase of cell surface HER2 in p95HER2/611CTF-expressing cells (Figure 2F) was accompanied by an increase in trastuzumab-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (Figure 2G).

The very recent analysis of p95HER2/611CTF in samples of the NeoALTTO trial has shown that p95HER2/611CTF is also associated with a better response of breast cancers to trastuzumab in combination with paclitaxel (16), a microtubule-stabilizing drug. The sensitivity of cell lines expressing different levels of p95HER2/611CTF shows that, as is the case with doxorubicin, the HER2 fragment sensitizes to the treatment with paclitaxel. Further, paclitaxel also increased the levels of HER2 at the cell surface in p95HER2/611CTF-expressing cells but not in p95HER2/611CTF-negative cells (Supplementary Figure 4, available online).

The results presented here show that breast cancer cells expressing p95HER2/611CTF are effectively targeted by regimens including chemotherapy in combination with trastuzumab (scheme in Figure 2H). This is likely because of the higher sensitivity of p95HER2/611CTF-positive cells to the chemotherapeutic agents and, in addition, because of the stabilization of full-length HER2, which results in more effective ADCC. This study also had some limitations. Because of the difficulty of establishing PDXs, we could only analyze two. The expansion of this analysis would definitively confirm the effect of the expression of p95HER2/611CTF on the response to trastuzumab plus chemotherapy. In addition, evaluation of ADCC was performed only in cell lines expressing levels of p95HER2/611CTF higher than those observed in tumor samples. Despite these limitations, these results reconcile previous apparently contradictory reports and indicate that p95HER2/611CTF is a useful biomarker for the efficacy of therapeutic regimens including trastuzumab and chemotherapy.

Funding

JA was supported by funds from The Breast Cancer Research Foundation (BCRF), the Spanish Association Against Cancer (Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer, AECC), AVON Cosmetics, Fundación Sandra Ibarra, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Intrasalud Intrasalud PI12/02536), and the Network of Cooperative Cancer Research (RTICC-RD12/0036/0003 /0042 /0057). CMP was supported by the National Cancer Institute Breast SPORE (P50-CA58223-09A1) and the BCRF. ITR was supported by a grant from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI11/02496). KP was supported by the postdoctoral program from the AECC.

Supplementary Material

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Pegram MD, Konecny GE, O’Callaghan C, Beryt M, Pietras R, Slamon DJ. Rational combinations of trastuzumab with chemotherapeutic drugs used in the treatment of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(10):739–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gradishar WJ. HER2 therapy--an abundance of riches. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(2):176–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arribas J, Baselga J, Pedersen K, Parra-Palau JL. p95HER2 and breast cancer. Cancer Research. 2011;71(5):1515–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Scaltriti M, Rojo F, Ocaña A, et al. Expression of p95HER2, a truncated form of the HER2 receptor, and response to anti-HER2 therapies in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(8):628–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pedersen K, Angelini PD, Laos S, et al. A naturally occurring HER2 carboxy-terminal fragment promotes mammary tumor growth and metastasis. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(12):3319–3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Parra-Palau JL, Pedersen K, Peg V, et al. A major role of p95/611-CTF, a carboxy-terminal fragment of HER2, in the down-modulation of the estrogen receptor in HER2-positive breast cancers. Cancer Research. 2010;70(21):8537–8546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sperinde J, Jin X, Banerjee J, et al. Quantitation of p95HER2 in paraffin sections by using a p95-specific antibody and correlation with outcome in a cohort of trastuzumab-treated breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(16):4226–4235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Loibl S, Bruey J, Minckwitz Von G, et al. Validation of p95 as a predictive marker for trastuzumab-based therapy in primary HER2-positive breast cancer: A translational investigation from the neoadjuvant GeparQuattro study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(suppl):Abstract 530. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Prat A, Bianchini G, Thomas M, et al. Research-Based PAM50 Subtype Predictor Identifies Higher Responses and Improved Survival Outcomes in HER2-Positive Breast Cancer in the NOAH Study. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(2):511–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fasching PA, Heusinger K, Haeberle L, et al. Ki67, chemotherapy response, and prognosis in breast cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant treatment. BMC Cancer. 2011;11(1):486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Morancho B, Parra-Palau JL, Ibrahim YH, et al. A dominant-negative N-terminal fragment of HER2 frequently expressed in breast cancers. Oncogene. 2013;32(11):1452–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gennari R, Menard S, Fagnoni F, et al. Pilot study of the mechanism of action of preoperative trastuzumab in patients with primary operable breast tumors overexpressing HER2. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(17):5650–5655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Clynes RA, Towers TL, Presta LG, Ravetch JV. Inhibitory Fc receptors modulate in vivo cytotoxicity against tumor targets. Nature Medicine. 2000;6(4):443–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Piloto O, Levis M, Huso D, et al. Inhibitory anti-FLT3 antibodies are capable of mediating antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity and reducing engraftment of acute myelogenous leukemia blasts in nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient mice. Cancer Research. 2005;65(4):1514–1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Scaltriti M, Verma C, Guzman M, et al. Lapatinib, a HER2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor, induces stabilization and accumulation of HER2 and potentiates trastuzumab-dependent cell cytotoxicity. Oncogene. 2009;28(6):803–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Scaltriti M, Nuciforo P, Bradbury I, et al. High HER2 expression correlates with response to trastuzumab and the combination of trastuzumab and lapatinib. 36th San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; 2013:Poster P1–08–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jacobs TW, Gown AM, Yaziji H, Barnes MJ, Schnitt SJ. Specificity of HercepTest in determining HER-2/neu status of breast cancers using the United States Food and Drug Administration-approved scoring system. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(7):1983–1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Parker JS, Mullins M, Cheang MCU, et al. Supervised Risk Predictor of Breast Cancer Based on Intrinsic Subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(8):1160–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.