Abstract

The anti-neoplastic prodrug, cyclophosphamide, requires biotransformation to phosphoramide mustard (PM), which partitions to volatile chloroethylaziridine (CEZ). PM and CEZ are ovotoxicants, however their ovarian biotransformation remains ill-defined. This study investigated PM and CEZ metabolism mechanisms through the utilization of cultured postnatal day 4 (PND4) Fisher 344 (F344) rat ovaries exposed to vehicle control (1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)) or PM (60μM) for 2 or 4 days. Quantification of mRNA levels via an RT2 profiler PCR array and target-specific RT-PCR along with Western blotting found increased mRNA and protein levels of xenobiotic metabolism genes including microsomal epoxide hydrolase (Ephx1) and glutathione S-transferase isoform pi (Gstp). PND4 ovaries were treated with 1% DMSO, PM (60μM), cyclohexene oxide to inhibit EPHX1 (CHO; 2mM), or PM + CHO for 4 days. Lack of functional EPHX1 increased PM-induced ovotoxicity, suggesting a detoxification role for EPHX1. PND4 ovaries were also treated with 1% DMSO, PM (60μM), BSO (Glutathione (GSH) depletion; 100μM), GEE (GSH supplementation; 2.5mM), PM ± BSO, or PM ± GEE for 4 days. GSH supplementation prevented PM-induced follicle loss, whereas no impact of GSH depletion was observed. Lastly, the effect of ovarian GSH on CEZ liberation and ovotoxicity was evaluated. Both untreated and GEE-treated PND4 ovaries were plated adjacent to ovaries receiving PM + GEE or PM + BSO treatments. Less CEZ-induced ovotoxicity was observed with both GEE and BSO treatments indicating reduced CEZ liberation from PM. Collectively, this study supports ovarian biotransformation of PM, thereby influencing the ovotoxicity that ensues.

Keywords: ovary, chemotherapy, metabolism, glutathione

In the United States, there are an estimated 7.2 million female cancer survivors with 360,000 aged below 40 (Siegel et al., 2012). For female cancer survivors, a major concern that can affect the quality of life post-treatment is the increased risk for infertility as a consequence of premature ovarian failure (POF).

The anti-neoplastic drug, cyclophosphamide (CPA), when included in the chemotherapy regimen of breast cancer patients, led to a significant increase in the number of women experiencing POF (Bines et al., 1996). POF results from depletion of the finite ovarian follicular pool (Hirshfield, 1991). Follicles are the structures encompassing the oocyte with granulosa cells (small preantral follicles) and theca cells (antral follicles) surrounding the gamete during follicular development. Primordial follicles are the most premature follicle type and due to their inability to be replenished, it is critical that their viability is maintained to ensure fertility. CPA induces POF via the depletion of primordial follicles (Plowchalk and Mattison, 1991).

Similar to women, studies in rodents have shown that CPA exposure destroys the primordial follicles in mice (Desmeules and Devine, 2006; Plowchalk and Mattison, 1991) and antral (the developmental stage prior to ovulation) follicles in rats (Jarrell et al., 1991) at concentrations relevant to human exposures (Desmeules and Devine, 2006; Struck et al., 1987). The results from these studies coincide with the human side effects, such as amenorrhea, premature menopause, and infertility, reported by women and young girls who have undergone CPA treatment (Sanders et al., 1988; Suarez-Almazor et al., 2000).

When administered, CPA is not in its active form, but requires hepatic bioactivation for chemotherapeutic effects. Cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP) initiate CPA biotransformation, which continues non-enzymatically to form the active, antineoplastic metabolite phosphoramide mustard (PM) (Ludeman, 1999; Shulman-Roskes et al., 1998). In addition to targeting cancer cells, PM is also the ovotoxic metabolite of CPA, both in vivo (Plowchalk and Mattison, 1991) and in vitro (Desmeules and Devine, 2006). Interestingly, PM is capable of partitioning further to form the volatile metabolite, chloroethylaziridine (CEZ) (Rauen and Norpoth, 1968; Shulman-Roskes et al., 1998), which is also an ovotoxicant (Desmeules and Devine, 2006; Madden et al., 2014).

Although the bioactivation of CPA is well established, information on the mechanism of detoxification of this drug is lacking. The evidence available suggests that CPA and metabolites are detoxified by NADPH oxidation and glutathione (GSH) conjugation (Pinto et al., 2009), with variation in mechanisms occurring among follicle types (Desmeules and Devine, 2006). GSH conjugation to PM can occur spontaneously or non-spontaneously (Dirven et al., 1994; Yuan et al., 1991). Non-spontaneous GSH conjugation to PM likely occurs via the glutathione S-transferase (GST) family of enzymes, which are the predominant enzymes involved in GSH conjugation and detoxification of xenobiotics. Specifically, GSH, in excess, has been shown to decrease the stability of CEZ (Shulman-Roskes et al., 1998) and, furthermore, GSH has been shown to reduce the generation of CEZ from PM by promoting an alkylation reaction, in favor of the CEZ-forming hydrolysis reaction (Shulman-Roskes et al., 1998).

PM likely also undergoes phase I biotransformation, such as hydroxylation, which has been demonstrated in the biotransformation of other ovotoxicants. 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA), for example, is bioactivated to its ovotoxic form by hydroxylation via action of the enzyme microsomal epoxide hydrolase (EPHX1) (Igawa et al., 2009; Rajapaksa et al., 2007). In contrast, EPHX1 activity results in the formation of an inactive tetrol form of 4-vinylcyclohexene diepoxide (VCD), thereby providing a detoxification role for VCD, the opposite of that observed during DMBA bioactivation (Cannady et al., 2002; Flaws et al., 1994). Conjugation of GSH to PM (a phase II reaction) has been reported to replace one or both of the chlorides of PM (Dirven et al., 1994); however, it is unclear whether this reaction leads to a PM metabolite of lesser toxicity.

We hypothesized that activation of ovarian biotransformation enzymes would occur at time points prior to observed follicle loss. A neonatal rat ovarian culture system was used to characterize the biotransformation of PM in the absence of hepatic contribution, using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and Western blotting to evaluate enzymes that are involved in PM metabolism. In addition, manipulation of ovarian GSH and EPHX1 levels were achieved using chemical approaches in order to gain insight into the role of these xenobiotic metabolism enzymes and the impact they could have with respect to the reproductive outcome of PM exposure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Bovine serum albumin (BSA), ascorbic acid, transferrin, 2-β-mercaptoethanol, 30% acrylamide/0.8% bisacrylamide, ammonium persulphate, glycerol, N′ N′ N′ N′-tetrathylethylenediamine, Tris base, Tris HCL, sodium chloride, Tween-20, phosphatase inhibitor, protease inhibitor, BSO, CHO, and GEE were purchased from Sigma Aldrich Inc. (St. Louis, MO). Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM): nutrient mixture F-12 (Ham) 1x (DMEM/Ham's F12), Albumax, penicillin (5000 U/ml), Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (without CaCl2, Mg Cl2, or MgSO4) were obtained from Invitrogen Co. (Grand Island, NY). Millicell-CM filter inserts, anti-GSTP, and anti-GSTM were obtained from Millipore (Billerica, MA). RNeasy Mini kit, QIA Shredder kit, RNeasy Mini Elute kit, Quantitect SYBR Green PCR kit RT2 First Strand kit, RT2 SYBR Green Mastermix, and the Drug Metabolism RT2 Profiler PCR arrays were purchased from Qiagen Inc. (Valencia, CA). RNAlater and 48-well cell culture plates were obtained from Ambion Inc. (Grand Island, NY) and Corning Inc. (Corning, NY), respectively. PM was acquired from the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MA). All primers were obtained from the DNA facility of the Iowa State University office of biotechnology (Ames, IA). Ponceau S was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). SignalFire ECL Reagent and anti-rabbit, HRP-link secondary antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Anti- EPHX1 antibody was purchased from Detroit R&D (Detroit, MI) and goat anti-rabbit and donkey anti-goat HRP-labeled secondary antibodies were obtained from Southern Biotech (Birmingham, AL) and Santa Cruz (Dallas, TX), respectively.

Animals

Fisher 344 (F344) rats were housed one per plastic cage and maintained in a controlled environment (22 ± 2ºC; 12-h light/12-h dark cycles). The animals were provided a standard diet with ad libitum access to food and water, and allowed to give birth. The Iowa State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee's approved all experimental procedures.

In Vitro Ovarian Cultures

Ovaries were collected from female postnatal day (PND) 4 F344 rats (Devine et al., 2002) after euthanasia. Both ovaries were removed, trimmed of excess tissue, and placed onto a Millicell-CM membrane floating on 250 μl of previously 37ºC-equilibrated DMEM/Ham's F12 medium containing 1-mg/ml BSA, 1-mg/ml Albumax, 50-μg/ml ascorbic acid, 5-U/ml penicillin, and 27.5-μg/ml transferrin per well in a 48-well plate. A drop of medium was placed on top of each ovary to prevent dehydration. Ovary cultures containing PM treatments were cultured in a separate incubator from other treatments to eliminate contamination from the ovotoxic, PM-generated volatile metabolite (Madden et al., 2014). The chosen PM concentration was 60μM that we have previously characterized to cause follicle depletion from day 4 onward (Madden et al., 2014). Exposure to PM was performed on alternate days as in our previous work. This ensured that follicle depletion was gradual, thus allowing for investigation of the ovarian mechanistic response to PM exposure, prior to follicle loss induction.

RNA Isolation and qRT-PCR

Ovaries were stored in RNAlater at −80ºC following 2 or 4 days of in vitro culture. Ovaries (n = 3; 10 ovaries per pool) were homogenized and added to a QIAshredder column before proceeding to total RNA isolation using an RNeasy Mini kit. RNA concentration was performed with RNeasy Mini Elute kit and total RNA isolated was quantified with a NanoDrop (λ = 260/280 nm; ND 1000; Nanodrop Technologies Inc., Wilmington, DE).

RT2 PCR array

According to the manufacturer's protocol, total RNA (250 ng) was reverse transcribed to cDNA using the RT2 first-strand kit and pipetted into Drug Metabolism RT2 Profiler PCR array, which contains 96-wells, each containing a gene-specific primer set, therefore one plate tested 96 genes per each sample. The PCR protocol utilized was a 10-min hold at 95ºC and 40 cycles of denaturing at 95ºC for 15 s and a combined annealing and extension for 1 min at 60ºC. Each gene was normalized to both housekeeping genes hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (Hprt) and ribosomal protein, large, P1 (Rplp1), as recommended by the company-provided analysis software. There was no effect of PM on mRNA levels of either of these two housekeeping genes. The online SABiosciences RT2 Profiler PCR Array Data Analysis software quantified the changes in mRNA levels using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Individual gene target RT-PCR

Total RNA (250 ng) was reverse transcription to cDNA with the Superscript III One-Step RT-PCR System (Invitrogen). Using an Eppendorf mastercycler (Hauppauge, NY) and Quantitect SYBR Green PCR kit (Qiagen Inc.), PCR amplification of the following genes was performed: Ephx1 (forward: 5′-GGCTCAAAGCCATCAGGCA-3′; reverse: 5′-CCTCCAGAAGGACACCACTTT-3′), Gstp (forward: 5′-GGCATCTGAAGCCTTTTGAG-3′; reverse: 5′-GAGCCACATAGGCAGAGAGC-3′), and Gstm (forward: 5′-TTCAAGCTGGGCCTGGAC-3′; reverse: 5′-CAGGATGGCATTGCTCTG-3′). The RT-PCR protocol used was a 15-min hold at 95ºC and 40 cycles of denaturing at 95ºC for 15 s, annealing temperature of 58ºC, and extension at 72ºC for 15 s. Gapdh was used as the housekeeping gene for normalization as no change in its mRNA levels was observed between treatments. PM-induced changes in mRNA levels were quantified using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001; Pfaffl, 2001).

Protein Isolation and Western Blot Analysis

PND4 ovaries (n = 3; 10 ovaries per pool) were homogenized in 200 μl of ice-cold tissue lysis buffer and protein quantified using a standard bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protocol on a 96-well assay plate. Total protein (15 μg) was separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Prior to 1-h blocking in 5% milk, equal protein loading was confirmed by Ponceau S staining. Membranes were then incubated at 4ºC with their respective, specific primary antibodies [Rabbit Anti-GSTM, Rabbit Anti-GSTP, Goat Anti-EPHX1]. Following 48–72 h of incubation, donkey anti-rabbit or porcine anti-goat secondary antibody was added and membranes were incubated with shaking for 1 h at room temperature. Autoradiograms were visualized on X-ray films in a dark room after 10-min incubation of membranes with 1X SignalFire ECL reagent. Densitometry of the appropriate-sized bands was measured using Image Studio Lite Version 3.1 (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE), which eliminates background noise. Values were normalized to Ponceau S staining.

Competitive Inhibition of EPHX1

On alternate days, ovaries (n = 4–6) were treated with vehicle control media (1% DMSO), PM (60μM), cyclohexene oxide (CHO; 2mM), or PM (60μM) + CHO (2mM) for 2 or 4 days. The concentration of CHO was determined by a previous study (Igawa et al., 2009).

GSH Depletion and Supplementation

Ovaries were treated on alternate days with DMSO (1%), PM (60μM), Glutathione ethyl ester (GEE; 2.5mM), DL-buthionine-(S,R)-sulfoximine (BSO; 100μM), PM (60μM) ± GEE (2.5mM), PM (60μM) ± BSO (100μM) or left untreated to evaluate the effect of the neighboring well CEZ liberation from PM. BSO and GEE concentrations and the addition of BSO 8 h prior to PM treatment were based on conditions described in a previous study (Tsai-Turton and Luderer, 2006). As previously reported, CEZ exposed ovaries were cultured in control media in the same incubator as PM-containing treatment, thus the ovaries were exposed to the volatile metabolite, presumably CEZ, liberated from PM (Madden et al., 2014).

Histological Evaluation of Follicle Numbers

Following treatment, ovaries were placed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 h, washed and stored in 70% ethanol, paraffin embedded, and serially sectioned (5μM). Every sixth section was mounted and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Healthy oocyte-containing follicles were identified and counted in every sixth section. Unhealthy follicles were distinguished from healthy follicles by the appearance of pyknotic bodies and intense eosinophilic staining of oocytes. Healthy follicles were classified and enumerated according to Flaws et al. (1994). Slides were blinded to prevent counting bias.

Statistical Analysis

Treatment comparisons for follicle count experiments were performed using Analysis of Variance. Quantitative RT-PCR and Western blot data were analyzed by t-test comparing treatment with control raw data at each individual time point. All statistical analysis was performed using Prism 5.04 software (GraphPad Software). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05, with a trend for a difference considered at p < 0.1.

RESULTS

Investigation of Xenobiotic Biotransformation Genes Involved in the Ovarian Response to PM Exposure

To gain insight into the ovarian genes that are activated during PM exposure, a drug metabolism RT2 Profiler PCR array was performed on PND4 rat ovaries (n = 3, 10 ovaries per pool) cultured 2 or 4 days with vehicle control (1% DMSO) or PM (60μM) exposure on alternate days. After 2 days of PM exposure, of the 89 genes tested, four were undetectable, seven genes had altered (p < 0.05) gene expression, and 1 gene, Chst1, was trending toward significance (p < 0.10) compared with the control (Table 1). Following 4 days of PM exposure, six genes were undetected, 24 genes had altered (p < 0.05) gene expression, and four genes had a tendency for altered (p < 0.10) mRNA abundance in response to PM, relative to control (Table 1). The results of this PCR array are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1. Effect of PM Exposure on Ovarian Expression of Drug Metabolism Genes.

| 30-μM PM | 60-μM PM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Name | Symbol | P-value | Fold Change | P-value | Fold Change |

| ATP citrate lyase | Acly | 0.954085 | 1.04 | 0.260582 | −1.25 |

| Aconitase 1, soluble | Aco1 | 0.361035 | 1.36 | 0.151053 | −1.45 |

| Aconitase 2, mitochondrial | Aco2 | 0.440342 | 1.32 | 0.373738 | −1.19 |

| Amylo-1,6-glucosidase, 4-alpha-glucanotransferase | Agl | 0.215581 | 1.41 | 0.400170 | −1.21 |

| Aldolase A, fructose-bisphosphate | Aldoa | 0.543220 | 1.12 | 0.816814 | 1.05 |

| Aldolase B, fructose-bisphosphate | Aldob | 0.231024 | −1.74 | 0.334998 | 1.8 |

| Aldolase C, fructose-bisphosphate | Aldoc | 0.819839 | −1.09 | 0.113404 | −1.78 |

| 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate mutase | Bpgm | 0.359882 | 1.35 | 0.127002 | 1.68 |

| Citrate synthase | Cs | 0.567867 | 1.42 | 0.057028 | −1.21 |

| Dihydrolipoamide S-acetyltransferase | Dlat | 0.538224 | 1.52 | 0.257482 | −1.45 |

| Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase | Dld | 0.384469 | 1.92 | 0.805230 | −1.02 |

| Dihydrolipoamide S-succinyltransferase (E2 component of 2-oxo-glutarate complex) | Dlst | 0.824887 | 1.16 | 0.080166† | −1.3 |

| Enolase 1, (alpha) | Eno1 | 0.676376 | 1.07 | 0.359418 | 1.34 |

| Enolase 2, gamma, neuronal | Eno2 | 0.814807 | 1.03 | 0.473007 | 1.35 |

| Enolase 3, beta, muscle | Eno3 | 0.629575 | 1.14 | 0.502520 | −1.22 |

| Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase 1 | Fbp1 | 0.919005 | −1.01 | 0.287978 | −2.4 |

| Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase 2 | Fbp2 | 0.676015 | −1.04 | 0.505544 | −2.04 |

| Fumarate hydratase 1 | Fh | 0.358126 | 1.13 | 0.383882 | −1.18 |

| Glucose-6-phosphatase, catalytic subunit | G6pc | 0.872923 | 1.03 | 0.007638* | −2.84 |

| Glucose 6 phosphatase, catalytic, 3 | G6pc3 | 0.810169 | 1.05 | 0.059505† | −1.95 |

| Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase | G6pd | 0.576016 | 1.12 | 0.144316 | −1.41 |

| Galactose mutarotase (aldose 1-epimerase) | Galm | 0.650490 | 1.19 | 0.312772 | 1.35 |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | Gapdh | 0.276757 | 1.36 | 0.251625 | 1.37 |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, spermatogenic | Gapdhs | 0.462385 | 1.29 | 0.426497 | −1.48 |

| Glucokinase | Gck | 0.929796 | −1.03 | 0.168133 | −2.33 |

| Glucose phosphate isomerase | Gpi | 0.779812 | 1.03 | 0.493985 | −1.1 |

| Glycogen synthase kinase 3 alpha | Gsk3a | 0.613481 | 1.1 | 0.247874 | −1.2 |

| Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta | Gsk3b | 0.404445 | 1.09 | 0.079423† | 1.45 |

| Glycogen synthase 1, muscle | Gys1 | 0.647872 | −1.14 | 0.110067 | −1.8 |

| Glycogen synthase 2 | Gys2 | 0.600890 | 1.28 | 0.573863 | 1.26 |

| Hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (glucose 1-dehydrogenase) | H6pd | 0.567968 | −1.16 | 0.269001 | −1.3 |

| Hexokinase 2 | Hk2 | 0.360123 | −1.32 | 0.844049 | −1.01 |

| Hexokinase 3 (white cell) | Hk3 | 0.527202 | 1.08 | 0.865241 | 1.02 |

| Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (NADP+), soluble | Idh1 | 0.227221 | −1.17 | 0.193151 | 1.58 |

| Isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 (NADP+), mitochondrial | Idh2 | 0.592548 | 1.06 | 0.073399† | −2.97 |

| Isocitrate dehydrogenase 3 (NAD+) alpha | Idh3a | 0.961088 | 1.09 | 0.075077† | −1.39 |

| Isocitrate dehydrogenase 3 (NAD+) beta | Idh3b | 0.534927 | −1.07 | 0.373165 | −1.15 |

| Isocitrate dehydrogenase 3 (NAD), gamma | Idh3g | 0.261828 | 1.07 | 0.351370 | −1.32 |

| Malate dehydrogenase 1, NAD (soluble) | Mdh1 | 0.413280 | 1.1 | 0.241708 | 1.42 |

| Malate dehydrogenase 1B, NAD (soluble) | Mdh1b | 0.562679 | −1.39 | 0.489485 | −1.54 |

| Malate dehydrogenase 2, NAD (mitochondrial) | Mdh2 | 0.338297 | −22.92 | 0.166786 | −1.35 |

| Oxoglutarate dehydrogenase-like | Ogdhl | 0.240227 | −1.17 | 0.123835 | −1.63 |

| Pyruvate carboxylase | Pc | 0.511677 | −1.14 | 0.764769 | −1.06 |

| Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 (soluble) | Pck1 | 0.683443 | −1.25 | 0.647213 | 1.09 |

| Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 2 (mitochondrial) | Pck2 | 0.447316 | −1.2 | 0.089265† | −1.9 |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase (lipoamide) alpha 2 | Pdha2 | 0.242983 | −1.22 | 0.311628 | −2.75 |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase (lipoamide) beta | Pdhb | 0.235421 | −1.25 | 0.418468 | 1.09 |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, component X | Pdhx | 0.713113 | 1.15 | 0.200738 | −1.39 |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, isozyme 1 | Pdk1 | 0.177869 | −1.15 | 0.478618 | −1.17 |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, isozyme 2 | Pdk2 | 0.258785 | −1.16 | 0.093081† | −1.56 |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, isozyme 3 | Pdk3 | 0.963417 | −1.01 | 0.288269 | −1.32 |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, isozyme 4 | Pdk4 | 0.014980* | 1.35 | 0.090272† | 1.37 |

| Pyruvate dehyrogenase phosphatase catalytic subunit 2 | Pdp2 | 0.039831* | −1.19 | 0.988424 | −1.01 |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase regulatory subunit | Pdpr | 0.470951 | −1.12 | 0.099850† | 1.1 |

| Phosphofructokinase, liver | Pfkl | 0.201969 | −1.41 | 0.131916 | −1.55 |

| Phosphoglycerate mutase 2 (muscle) | Pgam2 | 0.560662 | −1.09 | 0.618281 | −1.1 |

| Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | Pgk1 | 0.340109 | −1.38 | 0.231464 | −1.39 |

| Phosphoglycerate kinase 2 | Pgk2 | 0.894652 | −1.04 | 0.284540 | −1.84 |

| 6-phosphogluconolactonase | Pgls | 0.575543 | −1.13 | 0.191813 | −1.66 |

| Phosphoglucomutase 1 | Pgm1 | 0.681927 | −1.06 | 0.119746 | −1.35 |

| Phosphoglucomutase 2 | Pgm2 | 0.512691 | −1.08 | 0.110986 | −1.32 |

| Phosphoglucomutase 3 | Pgm3 | 0.334640 | −1.18 | 0.082189† | −1.47 |

| Phosphorylase kinase, alpha 1 | Phka1 | 0.047853* | −1.33 | 0.697097 | 1.08 |

| Phosphorylase kinase, beta | Phkb | 0.619762 | −1.13 | 0.443373 | −1.78 |

| Phosphorylase kinase, gamma 1 | Phkg1 | 0.623883 | −1.12 | 0.855811 | −1.01 |

| Phosphorylase kinase, gamma 2 (testis) | Phkg2 | 0.652275 | 1.05 | 0.416117 | 1.17 |

| Pyruvate kinase, liver and RBC | Pklr | 0.080488† | −1.72 | 0.750707 | 1.03 |

| Phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate synthetase 1 | Prps1 | 0.476081 | 1.05 | 0.640634 | −1.23 |

| Phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate synthetase 1-like 1 | Prps1l1 | 0.478036 | −1.2 | 0.487140 | 1.59 |

| Phosphorylase, glycogen, liver | Pygl | 0.811363 | −1.13 | 0.099240† | −1.74 |

| Phosphorylase, glycogen, muscle | Pygm | 0.362372 | −1.14 | 0.297640 | 1.36 |

| Ribokinase | Rbks | 0.658595 | 1.18 | 0.143132 | −1.84 |

| Ribose 5-phosphate isomerase A | Rpia | 0.308363 | −1.12 | 0.096241† | −1.78 |

| Succinate dehydrogenase complex, subunit A, flavoprotein (Fp) | Sdha | 0.460289 | 20.55 | 0.198160 | −1.28 |

| Succinate dehydrogenase complex, subunit B, iron sulfur (Ip) | Sdhb | 0.187586 | −1.1 | 0.181449 | −1.55 |

| Succinate dehydrogenase complex, subunit C, integral membrane protein | Sdhc | 0.188390 | −1.14 | 0.039619* | −1.65 |

| Succinate dehydrogenase complex, subunit D, integral membrane protein | Sdhd | 0.063955† | −1.2 | 0.202560 | −1.68 |

| Succinate-CoA ligase, ADP-forming, beta subunit | Sucla2 | 0.119000 | −1.07 | 0.116385 | 1.36 |

| Succinate-CoA ligase, alpha subunit | Suclg1 | 0.381353 | −1.1 | 0.049259* | −1.59 |

| Succinate-CoA ligase, GDP-forming, beta subunit | Suclg2 | 0.432898 | −1.07 | 0.075873† | −1.91 |

| Transaldolase 1 | Taldo1 | 0.596663 | −1.05 | 0.095173 | −1.55 |

| Transketolase | Tkt | 0.424777 | 1.12 | 0.100861 | −1.75 |

| Triosephosphate isomerase 1 | Tpi1 | 0.656505 | 1.08 | 0.630511 | −1.11 |

| UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase 2 | Ugp2 | 0.842375 | 1.16 | 0.542613 | 1.09 |

| Actin, beta | Actb | 0.546930 | −1.06 | 0.119631 | −1.31 |

| Beta-2 microglobulin | B2m | 0.278627 | −1.33 | 0.043742* | −1.36 |

| Hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 | Hprt1 | 0.256585 | 1.05 | 0.140881 | 1.57 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase A | Ldha | 0.833449 | 21.03 | 0.637703 | −1.17 |

| Ribosomal protein, large, P1 | Rplp1 | 0.254518 | −1.04 | 0.182563 | −1.57 |

PND4 rat ovaries (n = 3; 10 ovaries per pool) were treated with 1% DMSO (vehicle control) or PM (60μM) for 2 or 4 days. Following RNA isolation, mRNA levels were quantified with an RT2 Profiler PCR array. Values represent fold-change ± SEM relative to a control value of 1, normalized to Hprt1 and Rplp1. * = different from control, p < 0.05; † = p < 0.1.

Effect of PM Exposure on Xenobiotic Biotransformation Gene Expression

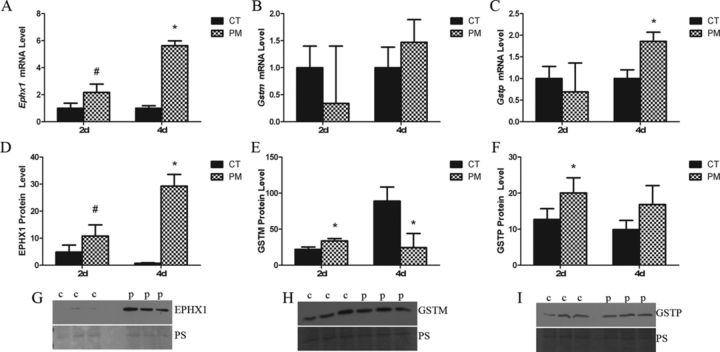

To both validate gene expression changes observed in the RT2 PCR array data and to determine changes in genes of interest that were not present on the array, primers were designed for candidate ovarian xenobiotic metabolism genes in PM metabolism. PND4 ovaries (n = 3, 10 ovaries per pool) were cultured for 2 or 4 days in control media (1% DMSO) or PM (60μM) to capture the molecular changes occurring prior to PM-induced follicle depletion (Madden et al., 2014). Following 2 days of PM exposure, there was no effect of treatment on Gstp or Gstm mRNA level compared with CT (Figs. 1B and C). However, after 4 days of PM exposure Gstp was increased (p < 0.05; 0.86-fold), relative to control (Fig. 1C). At 2 days, Ephx1 mRNA expression showed a tendency toward being increased (p < 0.1; 1.17-fold), followed by a large PM-induced increase in Ephx1 mRNA expression after 4 days (p < 0.05; 4.63-fold) (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Effect of PM on ovarian abundance of Ephx1, Gstm and Gstp mRNA, and protein. PND4 rat ovaries (n = 3; 10 ovaries per pool) were treated with 1% DMSO (vehicle control, CT) or PM (60μM). Following 2 or 4 days of culture, mRNA and protein were isolated and (A, D) Ephx1, (B, E) Gstm, and (C, F) Gstp, levels evaluated by quantitative RT-PCR or Western blot, respectively. mRNA values represent fold-change ± SEM relative to a control value of 1, normalized to Gapdh. Protein values represent signal intensity ± SEM normalized to Ponceau S. Representative blots for (G) EPHX1, (H) GSTM, and (G) GSTP are provided. *different from control, p < 0.05; #p < 0.1.

PM-Induced Changes in Protein Levels of Xenobiotic Metabolism Genes

In order to confirm the mRNA changes observed after PM exposure, protein levels were quantified in cultured PND4 ovaries (n = 3, 10 ovaries per pool) exposed to control media or media containing PM for 2 and 4 days. Compared with control, following 2 days of PM exposure, GSTP protein levels were increased (p < 0.05), but there was no effect of PM on GSTP protein level after 4 days of exposure (Fig. 1F). GSTM protein levels also increased (p < 0.05) following 2 days of PM exposure, but decreased (p < 0.05), relative to control, after 4 days (Fig. 1E). There was a trend for a PM-induced increase (p < 0.10) in EPHX1 protein levels after 2 days, followed by a large increase in EPHX1 after 4 days (Fig. 1D).

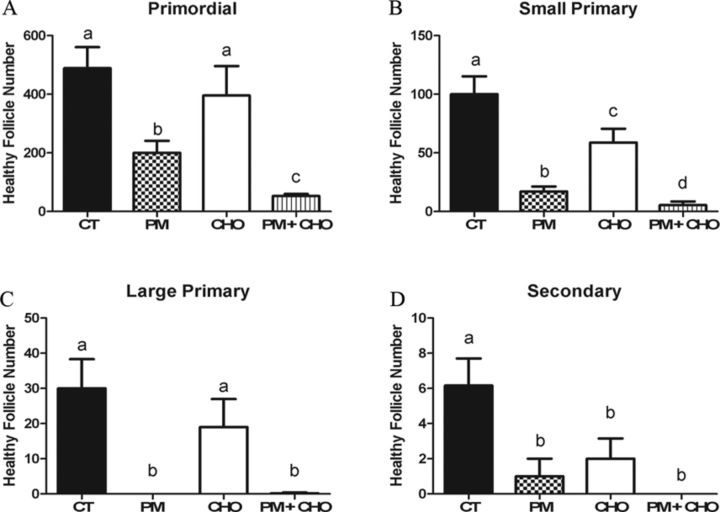

Evaluation of the Role of EPHX1 in PM Metabolism

EPHX1 was competitively inhibited by CHO in the neonatal culture system to evaluate the role of the enzyme in PM metabolism. PND4 ovaries (n = 4–6) were cultured for 4 days with vehicle control (1% DMSO), PM (60μM), CHO (2mM), or PM (60μM) + CHO (2mM). PM and PM + CHO-treated ovaries were cultured at separate times, in a separate incubator from the control ovaries to prevent control treated ovaries from being exposed to the volatile compound liberated from PM in our culture system (Madden et al., 2014).

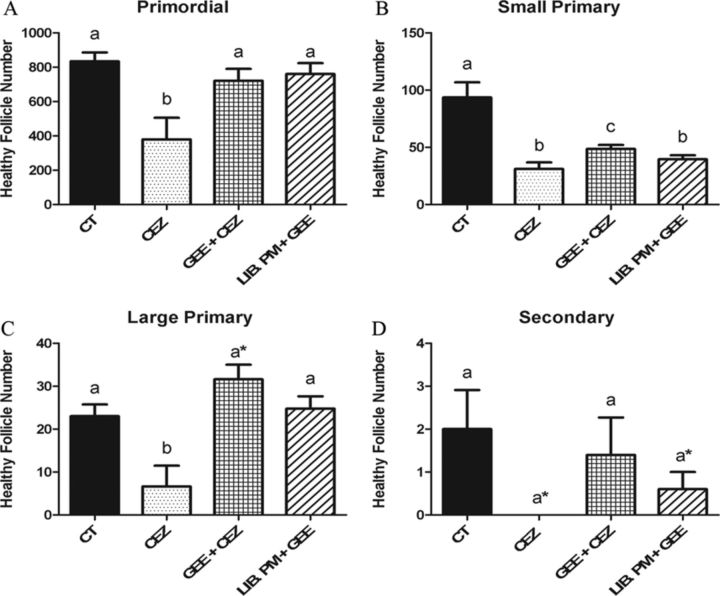

There was no effect of CHO treatment on primordial or large primary follicle number (Figs. 2A and C); however, CHO treatment alone lowered small primary and secondary follicles when compared with control (Figs. 2B and D). As previously reported (Madden et al., 2014), PM induced (p < 0.05) primordial (Fig. 2A), small primary (Fig. 2B), large primary (Fig. 2C), and secondary follicle loss compared with control (Fig. 2D). When EPHX1 was inhibited by CHO, in conjunction with PM exposure, greater (p < 0.05) primordial and small primary follicle loss was observed relative to PM alone (Figs. 2A and B).

FIG. 2.

Impact of EPHX1 inhibition during PM exposure on follicle number. PND4 rat ovaries were cultured and treated on alternate days to 1% DMSO (vehicle control, CT), PM (60μM), CHO (2mM), or PM (60μM) + CHO (2mM). Following 4 days of culture, follicles were classified and counted: (A) primordial follicles; (B) small primary follicles; (C) large primary follicles; (D) secondary follicles. Values represent mean ± SE total follicles counted/ovary, n = 4–6. Different letters represent significant difference between treatments p < 0.05.

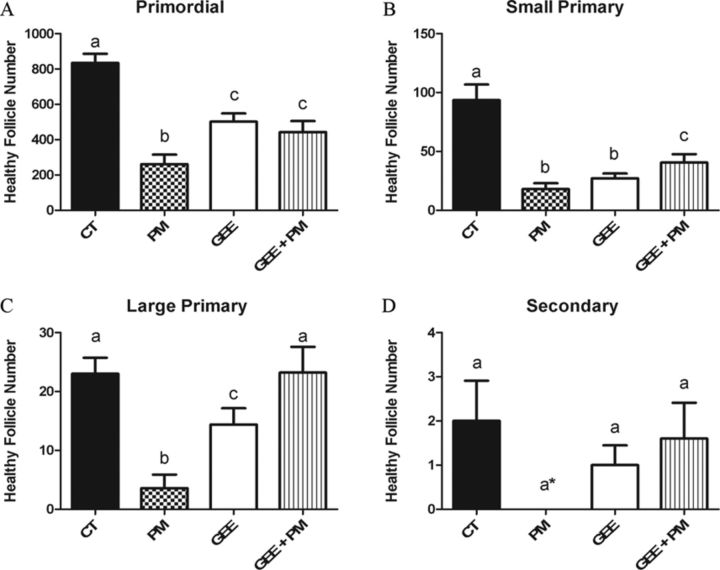

Impact of Ovarian GSH Level Manipulation on PM-Induced Ovotoxicity

In order to gain an understanding for the impact of GSH manipulation during PM-induced ovotoxicity, PND4 ovaries (n = 4–6) were cultured for 4 days with DMSO (1%), PM (60μM), GEE (2.5mM), BSO (100μM), PM (60μM) ± GEE (2.5mM), or PM (60μM) ± BSO (100μM). All PM-containing treatments were cultured in a separate incubator from other treatments to eliminate CEZ contamination (Madden et al., 2014).

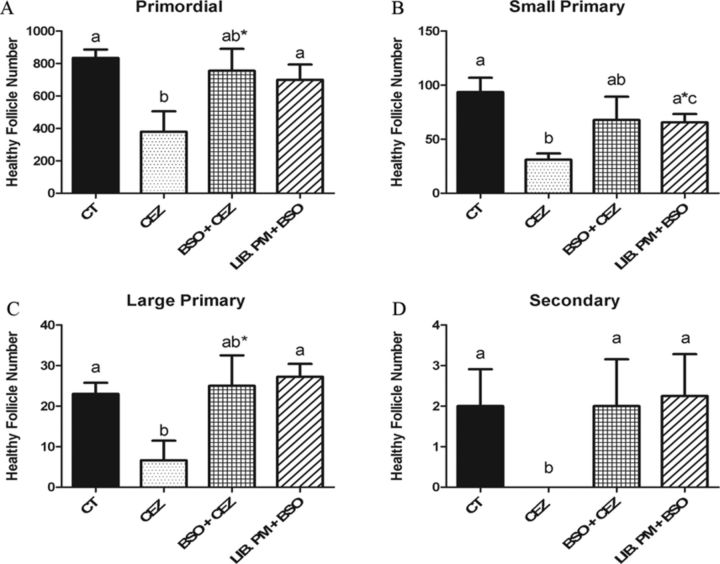

As previously reported, compared with control, PM depleted all follicle types after 4 days of culture (Madden et al., 2014). The addition of GSH alone, via GEE, depleted (p < 0.05) primordial, small primary, and large primary follicles (Figs. 3A–C), relative to control, with the number of small primary follicles being reduced to PM levels (Fig 3B). The supplementation of GSH via GEE in the presence of PM, reduced PM-induced follicle loss in all follicle types (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Impact of GSH supplementation during PM exposure on follicle number. PND4 rat ovaries were cultured and treated on alternate days to 1% DMSO (vehicle control, CT), PM (60μM), GEE (2.5mM), or PM (60μM) + GEE (2.5mM). Following 4 days of culture, follicles were classified and counted: (A) primordial follicles; (B) small primary follicles; (C) large primary follicles; (D) secondary follicles. Values represent mean ± SE total follicles counted/ovary, n = 4–6. Different letters represent significant difference between treatments p < 0.05. *p < 0.10 difference from CT.

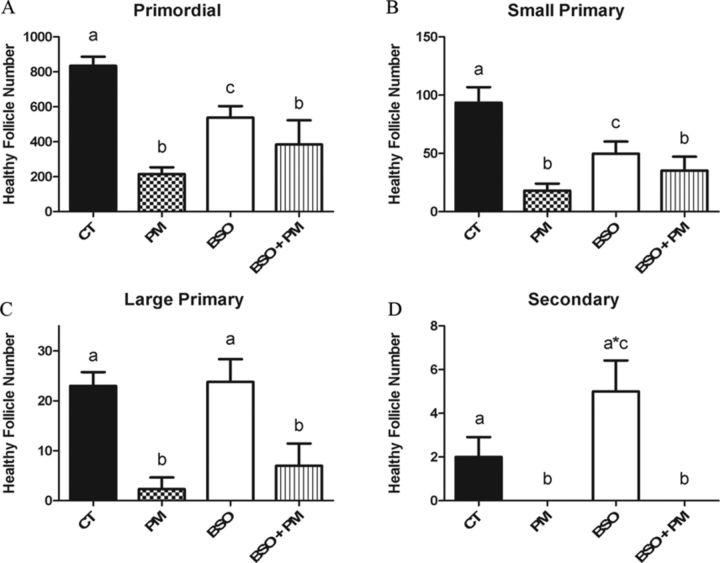

When GSH levels were depleted (p < 0.05) via the inhibition of GSH synthesis with BSO, BSO alone reduced (p < 0.05) the number of primordial and small primary follicles (Figs. 4A and B), whereas there was no effect on large primary follicles (Fig. 4C) and a trend (p < 0.1) for an increase in the number of secondary follicles (Fig. 4D) was observed relative to control. Similar to PM, compared with control, the inclusion of BSO with PM resulted in depletion (p < 0.05) of all follicle stages, with no difference in follicle loss observed relative to PM (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Impact of GSH depletion during PM exposure on follicle number. PND4 rat ovaries were cultured and treated on alternate days to 1% DMSO (vehicle control, CT), PM (60μM), BSO (100μM) or PM (60μM) + BSO (100μM). Following 4 days of culture, follicles were classified and counted: (A) primordial follicles; (B) small primary follicles; (C) large primary follicles; (D) secondary follicles. Values represent mean ± SE total follicles counted/ovary, n = 4–6. Different letters represent significant difference between treatments p < 0.05. *p < 0.10 difference from CT.

Impact of Altered GSH Levels on CEZ Liberation and Ovotoxicity

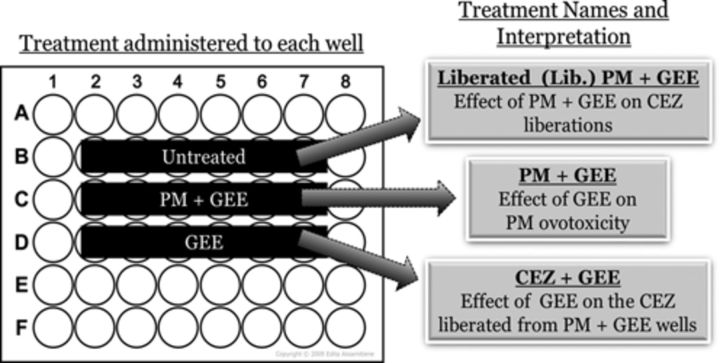

To evaluate the effect of altered ovarian GSH level on the generation of CEZ from PM and also to investigate the effect of GSH supplementation on CEZ ovotoxicity, cultured PND4 ovaries (n = 4–6) were treated for 4 days with DMSO (1%), PM (60μM), GEE (2.5mM), and BSO (100μM). In addition, ovaries were cultured in wells that received no treatment but were placed adjacent to wells containing an ovary that was exposed to PM + BSO or PM + GEE to evaluate the impact of GSH manipulation on CEZ generation from PM. These treatments were named Liberation (Lib.) PM + BSO or Lib. PM + GEE, respectively. Lastly, ovaries were treated with GEE (2.5mM) or BSO (100μM) in wells that were placed beside those that received PM + BSO (100μM) or PM + GEE (2.5mM) treatments in order to evaluate the effect of altered GSH on CEZ ovotoxicity. These treatments were designated CEZ + GEE and CEZ + BSO, respectively. This scheme is depicted in Figure 5. All ovaries receiving PM-containing treatments were cultured in a separate incubator from other treatments to eliminate CEZ contamination (Madden et al., 2014).

FIG. 5.

Plate layout for evaluation of the impact of ovarian GSH levels on CEZ liberation. Each well contained one PND4 rat ovary that was treated accordingly for 4 days to evaluate the following effects: untreated—ovaries cultured in control media were exposed to the CEZ liberated from the adjacent PM + GEE, thus named liberated (Lib.) PM + GEE; PM + GEE—ovaries treated with PM and GEE to evaluate the effect of GEE (GSH supplementation) on PM-induced ovotoxicity; and GEE—ovaries were treated with GEE and exposed to the CEZ liberated from the adjacent PM + GEE, thus named CEZ + GEE. Control treated ovaries were maintained in a separate incubator.

As previously reported, the volatile compound liberated from PM, presumably CEZ, depletes (p < 0.05) all follicle stages after 4 days of exposure (Madden et al., 2014). Relative to control, there was no primordial, large primary, or secondary follicle loss induced by the GEE + CEZ or Lib PM + GEE treatments (Figs. 6A, C, and D). Small primary follicle depletion, however, was impacted by the GEE + CEZ treatment and further worsened to PM levels by the Lib. PM + GEE treatment (Fig. 6B). BSO + CEZ and Lib PM + BSO exposures had no effect on follicle number at any stage of development, compared with control (Fig. 7).

FIG. 6.

Impact of GSH supplementation on CEZ liberation and ovotoxicity. PND4 rat ovaries were cultured and treated as described in Figure 5. Following 4 days of culture, follicles were classified and counted: (A) primordial follicles; (B) small primary follicles; (C) large primary follicles; (D) secondary follicles. Values represent mean ± SE total follicles counted/ovary, n = 4–6. Different letter represent significant difference between treatments p < 0.05. *p < 0.10 difference from CT.

FIG. 7.

Impact of GSH depletion on CEZ liberation and ovotoxicity. PND4 rat ovaries were cultured and treated as described in Figure 5. Following 4 days of culture, follicles were classified and counted: (A) primordial follicles; (B) small primary follicles; (C) large primary follicles; (D) secondary follicles. Values represent mean ± SE total follicles counted/ovary, n = 4–6. Different letter represent significant difference between treatments p < 0.05. *p < 0.10 difference from CT (a*) or PM (b*).

DISCUSSION

In 2012, an estimated 1.6-million people were diagnosed in the United States with cancer and 67% of these individuals will now survive at least 5 years post-diagnosis, compared with a 49% in 1977 (Siegel et al., 2012). Increasing the cancer survival rate is a great medical feat, yet coincides with increased risk for reduced fertility (Byrne et al., 1992; Sklar et al., 2006). Because the ovary is unable to replenish its gamete pool, accelerated loss of primordial follicles can hasten the onset of ovarian failure (Hirshfield, 1991).

To elicit the anti-neoplastic effects of CPA bioactivation to the ovotoxic form PM is required (Desmeules and Devine, 2006; Plowchalk and Mattison, 1991) and metabolism can potentially proceed further to formation of the volatile compound CEZ (Flowers et al., 2000; Madden et al., 2014). Bioactivation of CPA to PM has been well characterized in various tissues, but knowledge on detoxification of CPA and its metabolites remains lacking. Previous studies have demonstrated that GSH conjugation of PM occurs (Dirven et al., 1994), which, though unconfirmed, is assumed to represent a detoxification reaction, but this has not been demonstrated. Therefore, a PND4 rat ovary culture system was used to investigate the role of EPHX1 and GSH in PM metabolism and CEZ liberation.

Following PM exposure, EPHX1 was increased at both transcriptional and translational levels suggesting its involvement in PM metabolism. Previous reports have found that EPHX1 bioactivates DMBA to its ovotoxic form (Igawa et al., 2009; Rajapaksa et al., 2007), but, in contrast, detoxifies the ovotoxicant VCD (Bhattacharya et al., 2012; Cannady et al., 2002; Flaws et al., 1994; Keating et al., 2008). In order to evaluate a functional role for EPHX1 in PM metabolism, a competitive inhibitor of EPHX1, CHO, was used to block the action of EPHX1 during PM-induced follicle depletion. Lack of EPHX1 activity increased the level of PM-induced follicle loss, suggesting that EPHX1 is involved in the detoxification of PM to an as yet unidentified lesser ovotoxic metabolite.

As an epoxide hydrolase, EPHX1 action adds a hydrogen to the epoxide group of a chemical, which to our knowledge, is not included in the chemical structure of PM and its metabolites. Interestingly, however, CEZ, the volatile and ovotoxic metabolite of PM (Madden et al., 2014), is an aziridine compound capable of hydroxylation and may be the metabolite being detoxified by EPHX1 (Watabe and Suzuki, 1972), and, whereas outside the scope of the experiments described herein, is an area for future investigation.

The mRNA encoding several genes implicated in GSH conjugation catalysis and usage were altered by PM exposure. At a time prior to PM-induced follicle loss (Madden et al., 2014), the protein levels of GSTM and GSTP were increased. Interestingly, we observed a subsequent decrease in GSTM levels after 4 days of PM. We have previously demonstrated that GSTM negatively regulates ovarian apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) through protein interactions (Bhattacharya et al., 2013), thus a decline in GSTM protein could indicate that this negative regulation is being relieved and the cell being pushed toward an apoptotic fate as has been observed with ovarian DMBA exposure (Bhattacharya et al., 2013). These data support that the Gstp and Gstm genes are responsive to and involved in the ovarian response to PM exposure.

By manipulating the levels of GSH present in the ovary, the impact of GSH on PM-induced ovotoxicity was investigated. Ovarian supplementation of GSH during PM exposure restored follicle numbers to the GEE alone levels, with the exception of the large primary follicles where PM + GEE completely restored follicle loss to control levels. Surprisingly, GEE alone caused follicle loss in nearly all the follicle stages investigated indicating that an excess in GSH may be detrimental to follicles. These observations support that GSH conjugation to PM may represent a detoxification modification.

Unexpectedly, when GSH levels were depleted through blocking an enzyme essential to GSH synthesis, there was no impact on PM-induced follicle loss. These results therefore question the involvement of GSH conjugation in lessening the toxicity of PM. Our data are in agreement, however, with a study that found that depleting GSH levels in rat embryos did not impact PM-induced embryotoxicity, yet increased the toxicity of another CPA metabolite, acrolein (Slott and Hales,1987 ). Similarly, using rat hepatocytes and K562 human chronic myeloid leukemia cell in culture, PM did not impact the level of cellular GSH in either cell type, again, in contrast to acrolein, which depleted GSH levels.

Interestingly, the ovulated murine oocyte has an 8–10-mM GSH concentration (Perreault et al., 1988), which is among the highest of any cell type (Zuelke et al., 2003), and a prior study found that GSH concentration increased with age in mice in association with a decrease in CPA sensitivity (Mattison et al., 1983), but our literature review failed to provide the GSH concentrations in primordial and small primary follicles. It has previously been shown that a GSH-conjugate of trichloroethylene (TCA) represents a bioactivation modification and further decreased oocyte fertilizability relative to the parent compound (Wu and Berger, 2008), and it is known that GSH-conjugates are increasingly toxic in non-ovarian tissues (Monks et al., 1990), thus it is possible that excess GSH is promoting formation of potentially toxic GSH-conjugates or that negative feedback is occurring and limiting de novo synthesis of some important signaling mediators involved in PM metabolism. Fully understanding the GSH levels of all follicular stages would aid in interpretation of our results as well as improve our general understanding of primordial follicles metabolism and the mechanisms protecting this irreplaceable pool.

Another important aspect of the present study was the evaluation of the effect of ovarian GSH levels on CEZ generation from PM. Previous studies report that excess GSH will reduce the generation and stability of CEZ (Shulman-Roskes et al., 1998), thus we hypothesized that increasing GSH levels during PM exposure would reduce CEZ liberation, subsequently leading to reduced CEZ-induced follicle loss. When PM exposure was supplemented with GSH, our hypothesis was confirmed. However, surprisingly, when the levels of ovarian GSH were depleted during PM exposure, CEZ-induced follicle loss was also prevented. The physiological relevance of this result is unclear. It may be that BSO is not depleting ovarian GSH to a great enough extent to affect CEZ liberation. It could also be that a direct chemical reaction between BSO and PM is occurring to block the release of CEZ, but both scenarios render further investigation.

If, in the case of GSH supplementation and depletion, CEZ liberation is inhibited, this may partly explain the reduced follicle loss observed in the PM + GEE compared with PM treatments. The ovotoxicity of CEZ has been demonstrated (Madden et al., 2014) and our data suggest lack of CEZ liberation. Taken together, continued investigation of CEZ is required to understand the ovotoxic activity of this volatile, PM-generated metabolite.

In summary, the data generated from this study suggest that EPHX1 is involved in the detoxification of PM. Interestingly, excess GSH by itself impaired follicle viability, but GSH supplementation did reduce PM-induced follicle depletion. Depletion of GSH did not affect PM-induced ovotoxicity, thus the role of GSH in PM metabolism and ovotoxicity remains unclear. Ovarian chemical metabolism enzymes are widely expressed throughout the interstitial tissue, thus use of the neonatal model is considered appropriate for these studies. In addition, it is known that polymorphisms in the ovarian enzymes investigated herein confer increased susceptibility to ovarian cancer in humans (Hengstler et al., 1998). Thus the data generated in this study may further our ability to prevent PM-induced follicle loss, potentially by the overexpression of EPHX1, and could have profound implications for fertility preservation following cancer treatment with CPA, leading to an improved quality of life for millions of female cancer survivors.

FUNDING

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (R00ES016818).

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- Bhattacharya P., Madden J.A., Sen N., Hoyer P.B., Keating A.F. Glutathione S-transferase class mu regulation ofapoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 protein during VCD-induced ovotoxicity inneonatal rat ovaries. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2013;267:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya P., Sen N., Hoyer P. B., Keating A. F. Ovarian expressed microsomal epoxide hydrolase: Role in detoxification of 4-vinylcyclohexene diepoxide and regulation by phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase signaling. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2012;258:118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bines J., Oleske D. M., Cobleigh M. A. Ovarian function in premenopausal women treated with adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 1996;14:1718–1729. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.5.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne J., Fears T. R., Gail M. H., Pee D., Connelly R. R., Austin D. F., Holmes G. F., Holmes F. F., Latourette H. B., Meigs J. W., et al. Early menopause in long-term survivors of cancer during adolescence. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1992;166:788–793. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91335-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannady E. A., Dyer C. A., Christian P. J., Sipes I. G., Hoyer P. B. Expression and activity of microsomal epoxide hydrolase in follicles isolated from mouse ovaries. Toxicol. Sci. 2002;68:24–31. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/68.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmeules P., Devine P. J. Characterizing the ovotoxicity of cyclophosphamide metabolites on cultured mouse ovaries. Toxicol. Sci. 2006;90:500–509. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine P. J., Sipes I. G., Skinner M. K., Hoyer P. B. Characterization of a rat in vitro ovarian culture system to study the ovarian toxicant 4-vinylcyclohexene diepoxide. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2002;184:107–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirven H. A., Venekamp J. C., van Ommen B., van Bladeren P. J. The interaction of glutathione with 4-hydroxycyclophosphamide and phosphoramide mustard, studied by 31P nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1994;93:185–196. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(94)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaws J. A., Doerr J. K., Sipes I. G., Hoyer P. B. Destruction of preantral follicles in adult rats by 4-vinyl-1-cyclohexene diepoxide. Reprod. Toxicol. 1994;8:509–514. doi: 10.1016/0890-6238(94)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flowers J. L., Ludeman S. M., Gamcsik M. P., Colvin O. M., Shao K. L., Boal J. H., Springer J. B., Adams D. J. Evidence for a role of chloroethylaziridine in the cytotoxicity of cyclophosphamide. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2000;45:335–344. doi: 10.1007/s002800050049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengstler J.G., Arand M., Herrero M.E., Oesch F. Polymorphisms of N-acetyltransferases, glutathione S-transferases, microsomal epoxide hydrolase and sulfotransferases: Influence on cancer susceptibility. Recent Results Cancer Res. 1998;154:47–85. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-46870-4_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfield A. N. Development of follicles in the mammalian ovary. Int. Rev. cytology. 1991;124:43–101. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61524-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igawa Y., Keating A. F., Rajapaksa K. S., Sipes I. G., Hoyer P. B. Evaluation of ovotoxicity induced by 7, 12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene and its 3,4-diol metabolite utilizing a rat in vitro ovarian culture system. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2009;234:361–369. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrell J. F., Bodo L., YoungLai E. V., Barr R. D., O'Connell G. J. The short-term reproductive toxicity of cyclophosphamide in the female rat. Reprod. Toxicol. 1991;5:481–485. doi: 10.1016/0890-6238(91)90019-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating A. F., Sipes I. G., Hoyer P. B. Expression of ovarian microsomal epoxide hydrolase and glutathione S-transferase during onset of VCD-induced ovotoxicity in B6C3F(1) mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2008;230:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data usingreal-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludeman S. M. The chemistry of the metabolites of cyclophosphamide. Curr. Pharm. Des. 1999;5:627–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden J. A., Hoyer P. B., Devine P. J., Keating A. F. Involvement of a volatile metabolite during phosphoramide mustard-induced ovotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2014;277:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattison D.R., Shiromizu K., Pendergrass J.A., Thorgeirsson S.S. Ontogeny of ovarian glutathione and sensitivityto primordial oocyte destruction by cyclophosphamide. Ped. Pharmacol. 1983;3:49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monks T.J., Anders M.W., Dekant W., Stevens J.L., Lau S.S., van Bladeren P.J. Glutathione conjugate mediated toxicities. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1990;106:1–19. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(90)90100-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreault S.D., Barbee R.R., Slott V.L. Importance of glutathione in the acquisition andmaintenance of sperm nuclear decondensing activity in maturing hamster oocytes. Dev. Biol. 1988;125:181–186. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl M.W. A new mathematical model for relativequantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto N., Ludeman S. M., Dolan M. E. Drug focus: Pharmacogenetic studies related to cyclophosphamide-based therapy. Pharmacogenomics. 2009;10:1897–903. doi: 10.2217/pgs.09.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plowchalk D. R., Mattison D. R. Phosphoramide mustard is responsible for the ovarian toxicity of cyclophosphamide. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1991;107:472–481. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(91)90310-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajapaksa K. S., Sipes I. G., Hoyer P. B. Involvement of microsomal epoxide hydrolase enzyme in ovotoxicity caused by 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene. Toxicol. Sci. 2007;96:327–334. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauen H. M., Norpoth K. A volatile alkylating agent in the exhaled air following the administration of Endoxan. Klin. Wochenschr. 1968;46:272–275. doi: 10.1007/BF01770886. First published on Ein fluchtiges Alkylans in der Exhalationsluft nach Verabreichung von Endoxan. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders J. E., Buckner C. D., Amos D., Levy W., Appelbaum F. R., Doney K., Storb R., Sullivan K. M., Witherspoon R. P., Thomas E. D. Ovarian function following marrow transplantation for aplastic anemia or leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 1988;6:813–818. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1988.6.5.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman-Roskes E. M., Noe D. A., Gamcsik M. P., Marlow A. L., Hilton J., Hausheer F. H., Colvin O. M., Ludeman S. M. The partitioning of phosphoramide mustard and its aziridinium ions among alkylation and P-N bond hydrolysis reactions. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:515–529. doi: 10.1021/jm9704659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R., Naishadham D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2012;62:283–298. doi: 10.3322/caac.21153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklar C. A., Mertens A. C., Mitby P., Whitton J., Stovall M., Kasper C., Mulder J., Green D., Nicholson H. S., Yasui Y., et al. Premature menopause in survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:890–896. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slott V.L., Hales B.F. Enhancement of the embryotoxicity of acrolein,but not phosphoramide mustard, by glutathione depletion in rat embryos in vitro. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1987;36:2019–2025. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(87)90503-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struck R. F., Alberts D. S., Horne K., Phillips J. G., Peng Y. M., Roe D. J. Plasma pharmacokinetics of cyclophosphamide and its cytotoxic metabolites after intravenous versus oral administration in a randomized, crossover trial. Cancer Res. 1987;47:2723–2726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Almazor M. E., Belseck E., Shea B., Wells G., Tugwell P. Cyclophosphamide for treating rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2000;2000:CD001157. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai-Turton M., Luderer U. Opposing effects of glutathione depletion and follicle-stimulating hormone on reactive oxygen species and apoptosis in cultured preovulatory rat follicles. Endocrinology. 2006;147:1224–1236. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watabe T., Suzuki S. Studies on enzymatic hydrolysis of aziridines. II. Stereoselective hydrolysis of N-substituted 28,38-imino-5 -cholestanes by hepatic microsomal aziridine hydrolase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1972;46:1120–1127. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(72)80090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu K.L., Berger T. Reduction in rat oocyte fertilizability mediated by S-(1, 2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine: A trichloroethylene metabolite produced by the glutathione conjugation pathway. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2008;81:490–493. doi: 10.1007/s00128-008-9509-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Z. M., Smith P. B., Brundrett R. B., Colvin M., Fenselau C. Glutathione conjugation with phosphoramide mustard and cyclophosphamide. A mechanistic study using tandem mass spectrometry. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1991;19:625–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuelke K.A., Jeffay S.C., Zucker R.M., Perreault S.D. Glutathione (GSH) concentrations vary with thecell cycle in maturing hamster oocytes, zygotes, and pre-implantation stageembryos. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2003;64:106–112. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]