Abstract

Summary: BalestraWeb is an online server that allows users to instantly make predictions about the potential occurrence of interactions between any given drug–target pair, or predict the most likely interaction partners of any drug or target listed in the DrugBank. It also permits users to identify most similar drugs or most similar targets based on their interaction patterns. Outputs help to develop hypotheses about drug repurposing as well as potential side effects.

Availability and implementation: BalestraWeb is accessible at http://balestra.csb.pitt.edu/. The tool is built using a probabilistic matrix factorization method and DrugBank v3, and the latent variable models are trained using the GraphLab collaborative filtering toolkit. The server is implemented using Python, Flask, NumPy and SciPy.

Contact: bahar@pitt.edu

1 INTRODUCTION

Contemporary drug discovery faces important challenges: bringing a new molecular entity to the market is estimated to cost upward of 1.8 billion US$ (Paul et al., 2010), and the rate of new drug discovery has steadily halved every 9 years for the past 60 years (Scannell et al., 2012). One of the common suggestions brought forth to explain and remedy this trend is a paradigm shift in drug discovery efforts from high-affinity binding on a single target toward modulation of cellular network states through multiple interactions (Csermely et al., 2005, 2013; Hopkins, 2008; Keskin et al., 2007; Korcsmaros et al., 2007; Mencher and Wang, 2005; Zimmermann et al., 2007). The development of computational methods that can efficiently assess potential new interactions for drug repurposing thus became an important goal in quantitative systems/network pharmacology research.

We recently introduced a probabilistic matrix factorization (PMF) method that can be applied to known drug–target interaction graphs for predicting new interactions (Cobanoglu et al., 2013). Here, we introduce BalestraWeb, a Web server that has been developed for allowing users to efficiently obtain results from the PMF analysis, and assess the likelihood of interaction between any drug–target pair.

2 METHOD

BalestraWeb is built by training a latent factor model, as described in our previous work (Cobanoglu et al., 2013), on approved drugs and their interactions data from DrugBank v3 (Knox et al., 2011). To build the latent factor model, we use the GraphLab collaborative filtering toolkit implementation (Low et al., 2010). We mapped all the known names, brand names and synonyms of the drugs and targets to the relevant latent factor using a pre-computed hash table that allows constant time access and enables maximal efficiency.

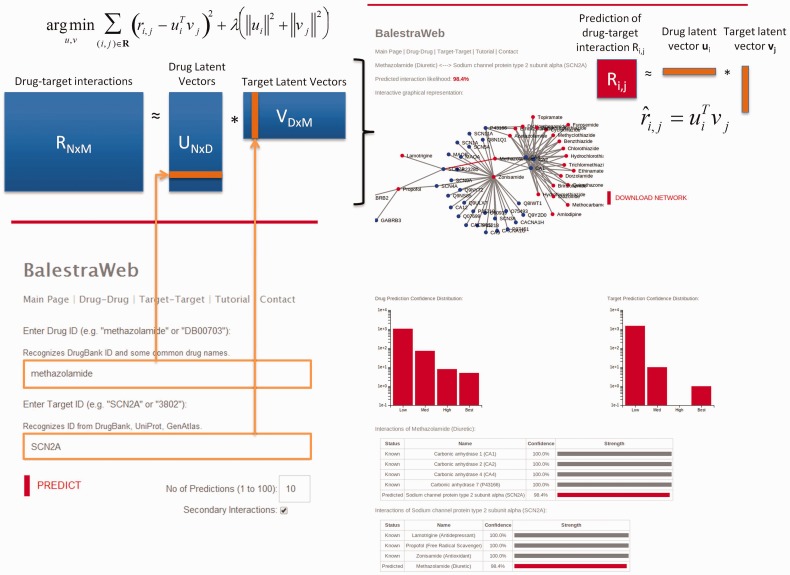

The server allows users to submit three types of queries: drug–target interaction, drug–drug similarity and target–target similarity. In the former case (Fig. 1), the input is mapped to the corresponding drug latent vector (LV) and target LV, and the dot product of these vectors yields a score for the probabilistic occurrence of the queried drug–target interaction. Alternatively, the user can enter a single type of input, either a drug or a target. If a single drug is entered, the server retrieves the LV for that drug and screens it against the entire set of LVs corresponding to all targets, so as to identify known and newly predicted targets. Drug–drug and target–target similarity queries provide information on drugs (or targets) similar to the query drug (or target) based on the cosine similarity of their LVs.

Fig. 1.

BalestraWeb architecture and underlying methodology. The user input (lower left) is mapped onto the latent factor vector(s) uivj (for targets), learned by minimizing squared error regularized by Frobenius norm (see equation at top left). The output (right) contains a score R representative of predicted interaction confidence along with a graphical representation of the close neighborhood of the query drug (Sunitinib) and/or query target (SCN5A) in the drug-target association network, along with a table of known and predicted interactions. Similar features hold for drug-drug and target-target similarity searches and outputs

The output is an interactive graph (that can be downloaded in JSON format) and a table displaying both the known drug–target interactions for the query drug (target) and the top N predicted targets (drugs), rank-ordered by their score. Users can select to view a second layer of interactions beyond the immediate neighbors of the query drug/target in the bipartite network of drugs and targets. The resulting subnet of interactions thus provides a more complete picture of the investigated drug/target in the context of the interactions of their known targets/drugs.

In addition to providing information on the distribution of scores in general in the tutorial, we provide query-specific histograms in the output files: the distribution of the predicted confidence score (for each member of the drug–target pairs) or the histogram of cosine similarities (for each member of the drug–drug or target–target pairs). These histograms facilitate the interpretation of the specific score released for the query pair in the context of the complete distribution of scores for the investigated drug/target, and help make a better assessment of the significance of the outputted score.

3 DISTINCTIVE FEATURES

There are three important distinguishing features of BalestraWeb: its ability to provide information on the likelihood of interaction between any drug and any target; its reliance on interaction profiles instead of chemical similarity; and its ability to compare drugs with drugs and targets with targets. The widely used similarity ensemble approach (SEA) (Keiser et al., 2007) uses ligand similarity to identify new ligands based on chemical similarity. STITCH (Kuhn et al., 2014) is an extensive repository of protein and chemicals (1.07 billion interactions), including predictions based on chemical similarities of compounds. However, the interactions predicted by BalestraWeb are not based on a particular chemical or genomic similarity method, but on the assessment of comparable interaction patterns, and as such they differ from, or complement, those predicted by SEA or listed by STITCH.

4 CONCLUSION

BalestraWeb provides users the ability to predict the most likely interaction partners of any drug or target beyond those known and compiled in the DrugBank. The technology used to build the Web server scales linearly with the number of drugs or targets and is therefore easily scalable to larger datasets as they become available. Our plan is to regularly update the underlying engine and optimized parameters by using the newly released data. The modular architecture of the software allows us to update the Web server to reflect changes as new data become available. Free, fast and easy-to-use BalestraWeb enables researchers to help eliminate improbable drug–target interactions and efficiently focus their limited resources on selected drugs.

Funding: Support from the NIH (U19 AI068021 and PO1 DK096990) is gratefully acknowledged by I.B.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Cobanoglu MC, et al. Predicting drug-target interactions using probabilistic matrix factorization. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2013;53:3399–3409. doi: 10.1021/ci400219z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csermely P, et al. The efficiency of multi-target drugs: the network approach might help drug design. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2005;26:178–182. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csermely P, et al. Structure and dynamics of molecular networks: a novel paradigm of drug discovery: a comprehensive review. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013;138:333–408. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins AL. Network pharmacology: the next paradigm in drug discovery. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:682–690. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keskin O, et al. Towards drugs targeting multiple proteins in a systems biology approach. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2007;7:943–951. doi: 10.2174/156802607780906690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiser MJ, et al. Relating protein pharmacology by ligand chemistry. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:197–206. doi: 10.1038/nbt1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox C, et al. DrugBank 3.0: a comprehensive resource for ‘omics’ research on drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D1035–D1041. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korcsmaros T, et al. How to design multi-target drugs: target search options in cellular networks. Discovery. 2007;2:1–10. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2.6.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn M, et al. STITCH 4: integration of protein-chemical interactions with user data. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2014;42:D401–D407. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low Y, et al. Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence. Catalina Island, CA: 2010. Graphlab: a new framework for parallel machine learning. [Google Scholar]

- Mencher SK, Wang LG. Promiscuous drugs compared to selective drugs (promiscuity can be a virtue) BMC Clin. Pharmacol. 2005;5:3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6904-5-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul SM, et al. How to improve R&D productivity: the pharmaceutical industry's grand challenge. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010;9:203–214. doi: 10.1038/nrd3078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scannell JW, et al. Diagnosing the decline in pharmaceutical R&D efficiency. Na.t Rev. Drug Discov. 2012;11:191–200. doi: 10.1038/nrd3681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann GR, et al. Multi-target therapeutics: when the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. Drug Discov. Today. 2007;12:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]