Key Points

Largest prospective trial for adult Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia patients.

Substantial cure rates and high treatment-realization rates in all age groups.

Abstract

This largest prospective multicenter trial for adult patients with Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia aimed to prove the efficacy and feasibility of short-intensive chemotherapy combined with the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab. From 2002 to 2011, 363 patients 16 to 85 years old were recruited in 98 centers. Treatment consisted of 6 5-day chemotherapy cycles with high-dose methotrexate, high-dose cytosine arabinoside, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, ifosphamide, corticosteroids, and triple intrathecal therapy. Patients >55 years old received a reduced regimen. Rituximab was given before each cycle and twice as maintenance, for a total of 8 doses. The rate of complete remission was 88% (319/363); overall survival (OS) at 5 years, 80%; and progression-free survival, 71%; with significant difference between adolescents, adults, and elderly patients (OS rate of 90%, 84%, and 62%, respectively). Full treatment could be applied in 86% of the patients. The most important prognostic factors were International Prognostic Index (IPI) score (0-2 vs 3-5; P = .0005), age-adjusted IPI score (0-1 vs 2-3; P = .0001), and gender (male vs female; P = .004). The high cure rate in this prospective trial with a substantial number of participating hospitals demonstrates the efficacy and feasibility of chemoimmunotherapy, even in elderly patients. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT00199082.

Introduction

Treatment strategies for Burkitt lymphoma were pioneered in pediatric studies. Murphy et al1 introduced fractionated high doses of cyclophosphamide and high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX), in addition to vincristine, doxorubicin, and cytarabine. Thereafter, major contributions to cure rates of 70% to 90% in children were made by Magrath et al from the US National Cancer Institute,2 St Jude Children’s Research Hospital,1 and several pediatric cooperative study groups in Europe such as the French Pediatric Oncology Society3 and the Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster group.4

These short-intensive regimens, all before rituximab, were adopted for adults with Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia, most in smaller series. In series with >30 patients, the weighted mean of the complete remission (CR) rates was 79%; the weighted mean of the overall survival (OS) rates was 64%.2,5-11

The German Multicenter Study Group for Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (GMALL) conducted several studies for Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia since 1983 based originally on a pediatric Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster protocol for high-grade non-Hodgkin lymphomas including Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia.4 The first protocol (B-NHL83) improved the OS rate for Burkitt leukemia significantly, from 10% with standard acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)-type therapy to 49%.5 In the subsequent studies, increased methotrexate doses from 500 mg/m2 to 1500 mg/m2 (B-NHL86) and to 3000 mg/m2 (B-NHL90) did not further improve OS but aggravated toxicity.7 Thus, a dose of methotrexate, 1500 mg/m2 in younger patients and 500 mg/m2 in elderly patients, was combined with the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab in the trial GMALL-B-ALL/NHL2002, reported here. Similarly, in all the above studies, short-intensive chemotherapy improved the outcome of adult Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia, but not further; therefore, rituximab was added, with the rationale that the CD20 antigen is highly expressed.12,13

There is still the need to improve the outcome in elderly Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia patients as evident from recent surveys.14-16 Also considering that the median age for this disease is 43 years in a survey from 2002 to 2008,14 and 49 years in another study,15 the GMALL study group decided to implement a dose-reduced protocol for patients aged >55 years to avoid substantial toxicity and thereby guarantee a high treatment-realization rate for this age cohort.

Patients and methods

Eligibility

Patients older than 15 years without an upper age limit were eligible if they had one of the following diagnoses: Burkitt lymphoma, Burkitt-like lymphoma, atypical Burkitt lymphoma, or Burkitt cell leukemia (Burkitt leukemia; also termed mature B-cell or L3-ALL). The following major exclusion criteria were applied: cytotoxic pretreatment except steroids or one cycle of CHOP (cyclophosphamide/hydroxy doxorubicin/vincristine/prednisone) or a similar regimen, severe impaired renal or liver function not caused by the underlying disease, secondary lymphoma following prior chemotherapy/radiotherapy, or an active second malignancy. The protocol was approved by the ethical review board of the University of Frankfurt. All patients had to give written informed consent. The study was registered in a public registry (NCT00199082).

Diagnosis

Diagnostic tumor biopsies were reviewed by hematopathologists and classified as Burkitt lymphoma, Burkitt-like lymphoma, or atypical Burkitt lymphoma according to the Revised European American Lymphoma classification criteria17 and the 2001 World Health Organization classification as the relevant classifications when the study was implemented. In Burkitt lymphoma, the diagnosis made by a local pathologist was confirmed by a reference Pathology Panel as a standard procedure in lymphoma diagnosis in 177 (79%) of the 225 patients. Chromosomal analysis and molecular genetics were not mandatory. Burkitt leukemia was defined as bone marrow involvement of leukemic blast cells in >25%. These diagnostic measures for Burkitt leukemia were performed in central laboratories for all participating hospitals.5

All the above diagnostic Burkitt subentities were further analyzed together as Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia.

Clinical investigations

Procedures at primary diagnosis included laboratory evaluations with complete blood counts, differential counts, bone marrow analysis, complete laboratory chemistry, and microbiological investigations. Clinical investigations consisted of physical examination plus ultrasonography, x-ray computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging if clinically indicated. Lumbar puncture for cerebral fluid at diagnosis was recommended for all Burkitt leukemia patients and in only those Burkitt lymphoma patients with neurologic symptoms.

Therapy

Chemoimmunotherapy regimen.

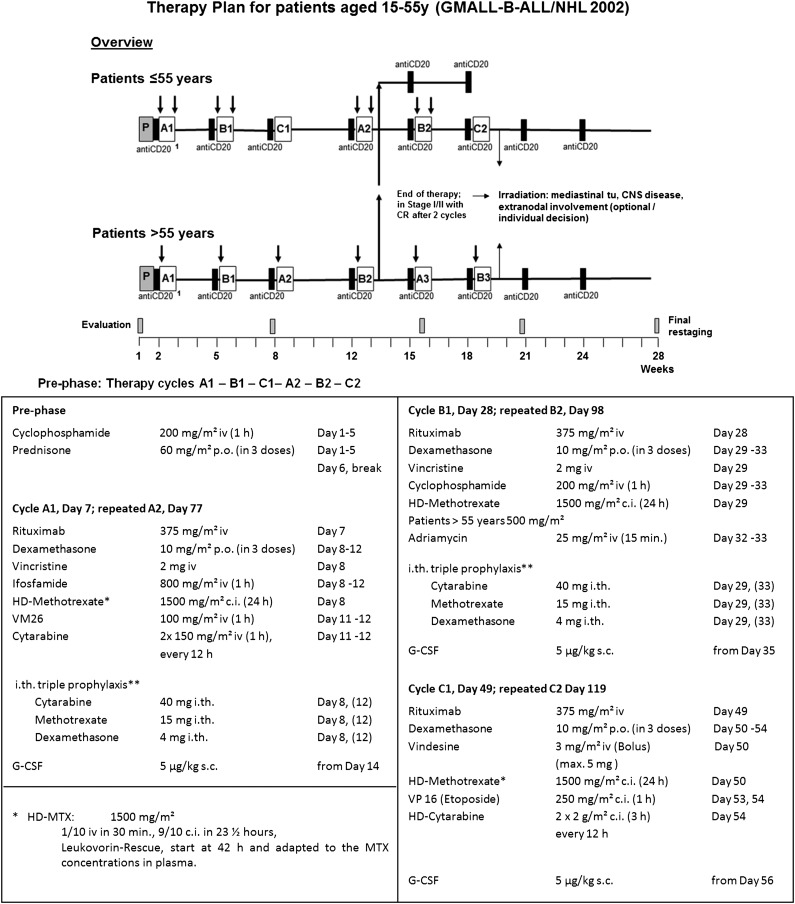

The chemotherapy schedule is summarized in Figure 1. All patients received a prephase treatment with cyclophosphamide and prednisone on days 1 to 5 to stabilize the clinical condition of the patient and to reduce the risk of tumor lysis syndrome. The protocol for younger patients (<55 years) consisted of 3 different courses (A, B, C) of chemotherapy, given at 2-week intervals, repeated once for a total of 6 cycles. All cycles started with a standard dose of rituximab (375 mg/m2), followed by chemotherapy the next day (details in Figure 1). Two additional doses of rituximab were administered 3 and 6 weeks after completion of the combined chemoimmunotherapy cycles. Older patients (>55 years) received alternating dose-reduced cycles A and B (see supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site).

Figure 1.

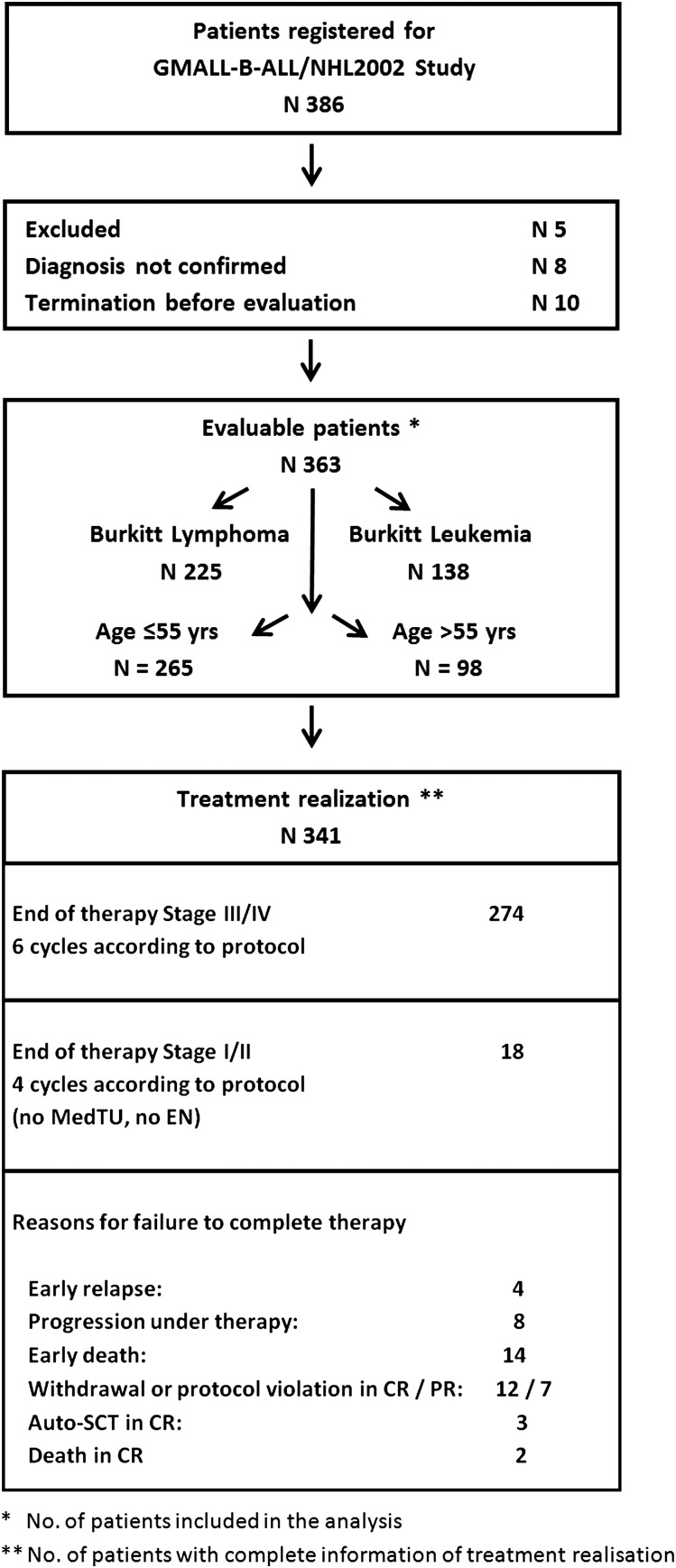

Consort diagram depicting enrollment, exclusion, and treatment realization. Overall chemoimmunotherapy realization: 86% of all patients received the complete number of treatment cycles, either 6 in stage III-IV or 4 of the planned cycles in stage I-II. A tumor lysis syndrome was observed in only 3 patients, which is less than 1%. Auto-SCT, autologous stem cell transplant; EN, extranodal involvement; MedTu, mediastinal tumor; PR, partial remission.

Radiotherapy and salvage therapy.

Central nervous system (CNS) irradiation (24 Gy) was recommended after 6 cycles for all patients with initial CNS involvement; mediastinal irradiation (36 Gy) was recommended for those with mediastinal tumor (>7.5 cm) at diagnosis. In patients with residual tumors at other sites, irradiation was given upon advice by the study center and the reference radiotherapist. For patients not responding, salvage therapy followed by subsequent stem cell transplantation was recommended.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed by the GMALL Study Center. The remission status was evaluated after cycles 2, 4, and 6. The response criteria followed the recommendations of an international working group that developed standardized response criteria in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.18 Toxicities were assessed according to the Common Terminology Criteria v2.0 scale for adverse events, and only grade 3/4 was recorded. The influence of entrance parameters on the achievement of CR was evaluated by the χ2 test. Median values were compared by the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. The probabilities for OS and progression-free survival (PFS) were computed by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. The Cox model was used to test prognostic factors in correlation with OS. The OS was calculated from the first day of therapy to death or the date of last review in all evaluable patients; PFS was calculated for all patients from the date of diagnosis to the date of early death, progression, failure, relapse, death in CR, or secondary malignancy (whatever occurred earlier) or the last date of follow-up (censored) in patients without progression/relapse, continuous CR/CR unconfirmed, or withdrawal. The median follow-up of surviving patients was 3.6 years. A calculated P value <.05 was established to indicate statistical significance. All analyses were performed with the SAS program (SAS 9.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient recruitment

Patients were recruited from 97 hospitals in Germany and one center in Poland. Of the 386 patients registered (Figure 2), 5 had to be excluded; 8 did not have their diagnosis confirmed; and 10 terminated the study before evaluation. Of the remaining 363 patients, 225 were diagnosed with Burkitt lymphoma and 138 with Burkitt leukemia; 265 were ≤55 years old, and 98 were >55 years old. The full treatment protocol could be realized in 86% (293/341).

Figure 2.

Treatment scheme and the detailed treatment application for patients aged 15 to 55 years. CNS prophylaxis (**) started with a single intrathecal administration of methotrexate (MTX) on day 1 of prephase treatment, followed by triple intrathecal therapy with MTX, cytarabine, and dexamethasone in cycles A and B, twice per cycle. The second application in cycle A on days 12 and 33 was later omitted because triple intrathecal therapy may have aggravated cytopenia, particularly neutropenia, due to a systemic effect; furthermore, the patients increasingly complained about the number of intrathecal injections. Patients with documented CNS involvement received intrathecal chemotherapy twice weekly during induction until the cerebrospinal fluid cell count was normalized and the cytological examination was negative, and then followed the prophylactic scheme described above. Prophylactic application of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor after each cycle was part of the protocol. The aim was the application to therapy cycles at 21-day intervals. Before each cycle, hematologic regeneration with granulocytes >1000/mL, platelets >50 000/mL, the absence of grade 3/4 mucositis, or other severe organ toxicities was required. In Burkitt patients with stage I-II disease achieving a CR already after 2 cycles, chemotherapy could be stopped after 4 cycles if they had no initial extranodal involvement or a mediastinal tumor. The protocol for older patients (>55 years) consisted of cycles A and B alternatively repeated up to 6 total cycles (supplemental Figure 1). To reduce toxicity, HD-MTX was reduced to 500 mg/m2, cycle C with high-dose cytarabine was omitted, and intrathecal therapy with MTX was reduced to single to triple intrathecal therapy. c.i., continuous infusion; G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; h, hour; HD, high-dose; i.th., intrathecal; p.o., by mouth; s.c., subcutaneously; tu, tumor; VM26, teniposide.

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics are given in Table 1 for the total cohort of 363 Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia patients. The median age was 42 years, with a range of 16 to 85 years. The 98 patients older than 55 years constituted 27%, with 19 patients aged 55 to 59 years, 34 aged 60 to 65 years, 30 aged 66 to 70 years, and 15 patients older than 70 years. There was an unequivocal gender distribution, with 70% (253) male and 30% (110) female patients. Extranodal involvement was observed in 86% (n = 297).

Table 1.

Disease characteristics and overall survival in Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia patients (N = 363)

| OS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease characteristics | Frequency (%) | Total, % | P |

| ECOG performance status | |||

| 0-2 | 285 (93) | 82 ± 2 | |

| 3-4 | 20 (7) | 74 ± 10 | .25 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 253 (70) | 84 ± 2 | |

| Female | 110 (30) | 70 ± 5 | .004 |

| Age* | |||

| 15-25 y | 69 (19) | 90 ± 4 | |

| 26-55 y | 196 (54) | 84 ± 3 | <.0001 |

| >55 y | 98 (27) | 62 ± 5 | |

| Karyotype | |||

| t(8;14), t(2;8), t(8;22), c-myc | 125 (80) | 77 ± 4 | .92 |

| No typical aberrations | 32 (20) | 78 ± 8 | |

| White blood cells | |||

| <30 000/µL | 317 (94) | 83 ± 2 | .007 |

| >30 000/µL | 21 (6) | 62 ± 11 | |

| Platelets | |||

| <25 000/µL | 38 (11) | 53 ± 8 | <.0001 |

| >25 000/µL | 302 (89) | 85 ± 2 | |

| Hemoglobin | |||

| <8 g/dL | 10 (3) | 70 ± 14 | .31 |

| >8 g/dL | 329 (97) | 81 ± 2 | |

| LDH | |||

| Within reference range (≤250 U/L) |

90 (26) | 95 ± 3 | |

| Moderately increased (>250-500 U/L) |

67 (20) | 76 ± 6 | .0006 |

| Increased (>500 U/L) | 184 (54) | 75 ± 3 | |

| Involved localizations | |||

| Lymph node | |||

| Yes | 261 (77) | 83 ± 2 | .20 |

| No | 79 (23) | 76 ± 5 | |

| Extranodal involvement | |||

| Yes | 297 (86) | 79 ± 3 | .08 |

| No | 49 (14) | 91 ± 4 | |

| CNS | |||

| Yes | 35 (10) | 67 ± 8 | .02 |

| No | 306 (90) | 82 ± 2 | |

| Bone marrow | |||

| Yes | 143 (42) | 67 ± 4 | <.0001 |

| No | 201 (58) | 90 ± 2 | |

| Other localizations | |||

| Mediastinal tumor | 26 (8) | ||

| Pleura | 55 (16) | ||

| Pericardium | 11 (3) | ||

| Spleen | 43 (13) | ||

| Liver | 49 (14) | ||

| Tonsils | 16 (5) | ||

| Thyroid | 7 (2) | ||

| Uterus/adnexa | 13 (4) | ||

| Testes/ovaries | 23 (7) | ||

| Kidney | 16 (5) | ||

| Lung | 8 (2) | ||

| Stomach | 31 (9) | ||

| Gut | 85 (25) | ||

| Bone | 28 (8) | ||

| Other | 76 (23) | ||

| Stage | |||

| I-II | 100 (29) | 90 ± 3 | .002 |

| III-IV | 249 (71) | 76 ± 3 | |

| IPI | |||

| low (0-2) | 140 (49) | 90 ± 3 | .0005 |

| high (3-5) | 146 (51) | 75 ± 4 | |

| aaIPI | |||

| low (0-1) | 111 (37) | 93 ± 3 | <.0001 |

| high (2-3) | 192 (63) | 74 ± 3 | |

Median age was 42 years (range 16-85 years).

aaIPI, age-adjusted IPI; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IPI, International Prognostic Index; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

Treatment response

The CR rate for the total cohort was 88% (Table 2); for the age cohorts ≤55 and >55 years, it was 89% and 84%, respectively (P = .0002). The death rate during therapy was lower for the younger patients <55 years old compared to patients >55 years old (2% vs 11%; P = .0002), in whom >90% of deaths were due to infections.

Table 2.

Overall results in Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia patients according to age: 15 to 55 years and older than 55 years

| Total | Age group, y | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 to ≤55 | >55 | |||

| No. of patients | 363 | 265 | 98 | |

| Response | ||||

| CR | 319 (88) | 237 (89) | 82 (84) | .0002 |

| PR | 13 (4) | 9 (3) | 4 (4) | |

| Failure/progression | 16 (4) | 15 (6) | 1 (1) | |

| Death | 15 (4) | 4 (2) | 11 (11) | |

| Outcome of CR patients | 319 | 237 | 82 | |

| Relapse | 37 (12) | 20 (8) | 17 (21) | |

| Death in CR | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 | |

| PFS | 0.75 ± 0.03 | 0.82 ± 0.03 | 0.60 ± 0.05 | <.0001 |

| OS | 0.80 ± 0.02 | 0.86 ± 0.02 | 0.62 ± 0.02 | <.0001 |

Values are n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

Overall outcome and prognostic factors

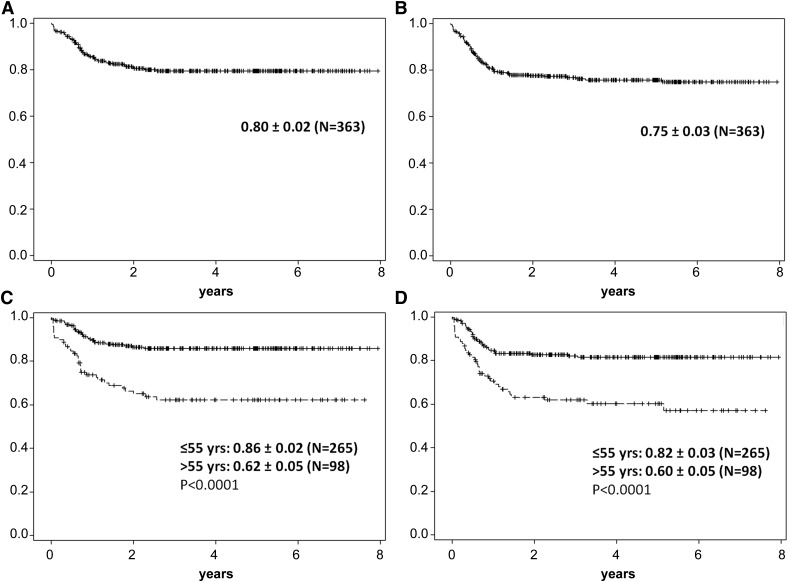

The OS rate for the total cohort was 80% ± 2%, and the PFS rate was 75% ± 3%.

The pretreatment with 1 cycle of CHOP (mostly applied due to delayed confirmed diagnosis) in a small cohort of patients (n = 14) vs no pretreatment (n = 349) had no impact on OS (supplemental Figure 2). In addition, the diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma vs Burkitt-like lymphoma had no influence on outcome. When the outcome was analyzed for the age groups ≤55 years vs >55 years (the latter having received the less-intensive protocol), the OS rate was 86% ± 2% vs 62% ± 2%, and the PFS rate was 82% ± 3% vs 60% ± 5% (Table 2; Figure 3). Adolescents (aged 15-25 years) had an OS rate of 90% ± 4%; adults (aged 26-55 years) had a rate of 64% ± 3%; and older patients (>55 years) had a rate of 62% ± 5%. The outcome of patients older than 55 years was further analyzed according to increasing age (supplemental Table 1), and revealed an OS rate of 56% ± 12% for patients 56 to 59 years (n = 19), 71% ± 8% for patients 60 to 65 years (n = 34), 68% ± 9% for patients 66 to 70 years (n = 30), and 43% ± 14% for patients >70 years (n = 15), without statistically significant difference (P = .75; supplemental Table 1).

Figure 3.

A+B 5-year probability of OS and PFS in Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia patients. (A) Five-year probablitity of OS in Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia patients (N = 363): 0.80 ± 0.02. (B) Five-year probability of PFS in Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia patients (N = 363): 0.75 ± 0.03. (C) Five-year probability of OS in Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia patients ≤55 years old (n = 265): 0.86 ± 0.02; >55 years old (n = 98): 0.62 ± 0.05 (P < .0001). (D) Five-year probability of PFS in Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia patients ≤55 years old: 0.82 ± 0.03; >55 years old: 0.60 ± 0.05 (P < .0001).

Several parameters at diagnosis had a significant impact on OS rate (Table 1): male (n = 253) vs female (n = 110) gender, 84% ± 2% vs 70% ± 5% (P = .004); white blood cell count below or above 30 000/µL, 83% ± 2% vs 62% ± 11% (P = .007); platelet count below or above 25 000/µL, 53% ± 8% vs 85% ± 2% (P = .007); LDH within the reference range (≤250 U/L) vs increased (>250 U/L) (P = .0006); bone marrow involvement vs none (P < .0001); CNS involvement at diagnosis vs none (P = .02); and stage I-II vs III-IV, 90% ± 3% vs 76% ± 3% (P = .002). For the IPI score of low (0-2) vs high (3-5), the OS was 90% ± 3% vs 75% ± 4% (P = .0005), and for the aaIPI, the corresponding OS for low score (0-1) vs high (2-3) was 93% ± 3% vs 74% ± 3% (P < .0001).

In a multivariate analysis for OS, the factors of age (≤55 or >55 years), LDH (≤250 vs >250 U/L), stage I-II vs III-IV, bone marrow involvement, CNS involvement, aaIPI score (0-1 vs 2-3), extranodal involvement, and gender were included, and the following factors remained significant: age (P = .0014; hazard ratio 2.5), bone marrow involvement (P = .01; hazard ratio 2.4), LDH (P = .02; hazard ratio 4.4), and gender (P = .006; hazard ratio 2.2).

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy was given as a consolidation in 61 of 363 patients. CNS irradiation with 24 Gy was applied to 24 patients with initial CNS involvement, and mediastinal irradiation with 36 Gy in 6 patients. Other sites of irradiation are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Radiation therapy of Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia patients (N = 363)

| Patients irradiated | |

|---|---|

| Total Localization |

61 (17) |

| Lymph nodes | 17 (5) |

| Mediastinal | 6 (2) |

| Extranodal | |

| CNS | 24 (7) |

| Bone | 6 (2) |

| Testes/ovaries | 1 |

| Kidney | 2 |

| Stomach | 1 |

| Abdomen | 1 |

| Nasopharynx | 1 |

| Tonsils | 1 |

| Breast | 1 |

Values are n or n (%).

Relapse pattern

The overall relapse rate of the CR patients was 12% (37/319) (Table 4). The most frequent site of relapse was the CNS (n = 12), either combined with other sites (n = 7) or as the primary site of relapse (n = 5). The second-most frequent relapse localization was the bone marrow (n = 9). Other relapse sites are listed in Table 4. The majority of relapses occurred within the first year.

Table 4.

Relapse localization in Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia patients who achieved CR (n = 319)

| Relapse patients | |

|---|---|

| Total Localization |

37 (12) |

| CNS ± other | 12 (4) |

| Age <55 y | 7 |

| Age >55 y | 5 |

| CNS, isolated | 5 (2) |

| Age <55y | 2 |

| Age >55y | 3 |

| Bone marrow ± other | 9 (3) |

| Age <55 y | 4 |

| Age >55 y | 5 |

| Lymph nodes | |

| Lymph nodes | 2 |

| Lymph nodes + other | 2 (intestine/lung) |

| Extranodal sites | |

| Gastrointestinal | 2 |

| Bone | 1 |

| Muscle | 1 |

| Skin | 2 |

| Pararenal | 1 |

Values are n or n (%).

Toxicity

The toxicity grade of 3/4 for all chemoimmunotherapy cycles (A1, B1, C1 and A2, B2, C2) and the cumulative toxicity for all cycles for patients ≤55 years are given in Table 5. Hematologic toxicity was the most pronounced toxicity, particularly the incidence of grade 3/4 neutropenias during cycle A1 in 58% of patients and the duration of grade 4 neutropenia with 6 days (decreasing in frequency and duration with each cycle). Correspondingly, infections were more often observed in cycle A1, with an incidence of 38%, also decreasing substantially during the subsequent cycles. Liver toxicity (glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase/glutamate pyruvate transaminase >5xN) was pronounced in the first treatment cycle. The incidence of mucositis grade 3/4 was high throughout the first 2 cycles. It is unfortunate that in the beginning of this study, a 33-year-old male Burkitt lymphoma patient was accidently administered intrathecal vincristine after cycle A2. Despite immediate recognition and treatment in the neurosurgery department, he died 9 months later. As a consequence, different steps to prevent accidental intrathecal injection were again recommended.19 The frequency of grade 3/4 neurotoxicity was otherwise low, with a cumulative incidence of 1%. Other toxicities of grade 3/4 occurred only in few patients (Table 5). The toxicity pattern for Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia patients >55 years old (also given separately for each chemotherapy cycle; supplemental Table 2) did not substantially differ from the younger cohort but was more pronounced. In particular, the first cycle revealed a high incidence of neutropenia grade 4 and, together with the prolonged duration, yielded a higher rate of infections associated with an increased rate of death in induction (11%), particularly in Burkitt leukemia patients.

Table 5.

Grade 3/4 toxicity in Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia patients aged 55 years or younger (n = 265)

| Treatment cycle | Cumulative | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | B1 | C1 | A2 | B2 | C2 | ||

| No. of cycles evaluable | 207 | 210 | 206 | 194 | 171 | 160 | 1148 |

| Hematologic events | |||||||

| Hemoglobin <8.0 g/dL | 78 (38) | 65 (31) | 84 (41) | 87 (45) | 54 (32) | 59 (37) | 427 (37) |

| White blood cells <2.0/µL | 164 (79) | 94 (45) | 134 (65) | 135 (70) | 89 (52) | 108 (68) | 724 (63) |

| Leukopenia grade 4, <1.0/µL, | |||||||

| duration, d (range) | 7 (1-22) | 3 (1-18) | 4 (1-24) | 3 (1-12) | 3 (1-27) | 4 (1-21) | |

| Neutrophils <1.0/µL | 120 (58) | 55 (26) | 82 (40) | 92 (47) | 32 (19) | 72 (45) | 453 (39) |

| Neutropenia grade 4, <0.5/µL, | |||||||

| duration (range) | 6 d (1-22) | 4 d (1-6) | 5 d (1-14) | 4 d (1-14) | 3 d (1-13) | 4 d (1-8) | |

| Platelets <50/µL | 149 (72) | 37 (18) | 134 (65) | 135 (70) | 59 (35) | 100 (63) | 614 (53) |

| Thrombopenia grade 4, <10/µL, | |||||||

| duration, d (range) | 2 (1-15) | 2 (1-5) | 2 (1-18) | 1 (1-8) | 2 (1-21) | 1 (1-4) | |

| General disorders | |||||||

| Fever | 8 (4) | 3 (1) | 8 (4) | 3 (2) | — | 2 (1) | 24 (2) |

| Pain | 53 (26) | 44 (21) | 29 (14) | 27 (14) | 21 (12) | 18 (11) | 192 (17) |

| Infection | 79 (38) | 36 (17) | 36 (17) | 49 (25) | 22 (13) | 30 (19) | 252 (22) |

| Liver toxicity | |||||||

| Bilirubin >3xN | 5 (2) | — | 2 (1) | 3 (2) | 1 | 1 | 12 (1) |

| GOT/GPT >5xN | 56 (27) | 18 (9) | 17 (8) | 24 (12) | 6 (4) | 7 (4) | 128 (11) |

| AP >5xN | 2 (1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | — | 5 |

| Gastrointestinal | |||||||

| Vomiting | 29 (14) | 22 (10) | 15 (7) | 20 (10) | 9 (5) | 5 (3) | 100 (9) |

| Mucositis (stomatitis) | 74 (36) | 78 (37) | 51 (25) | 52 (27) | 43 (25) | 31 (19) | 329 (29) |

| Diarrhea | 14 (7) | 8 (4) | 13 (6) | 6 (3) | 2 (1) | 4 (3) | 47 (4) |

| Colitis | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 6 (3) | 2 (1) | 1 | 1 | 15 (1) |

| Vascular | |||||||

| Bleeding | 6 (3) | — | 5 (2) | 3 (2) | 1 | 2 (1) | 17 (1) |

| Thromboembolic events | 3 (1) | 5 (2) | 3 (1) | 3 (2) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 18 (2) |

| Other | |||||||

| Lung | 9 (4) | 5 (2) | 3 (1) | 9 (5) | 2 (1) | 1 | 29 (3) |

| Cardiac | 2 (1) | — | 1 | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 1 | 10 (1) |

| Neurologic | — | 3 (1) | 2 | 1 | 2 (1) | — | 8 (1) |

| Skin reaction | 2 (1) | 1 | 1 | 3 (2) | 1 | — | 8 (1) |

| Fibrinogen <100 mg/dL | 1 | 1 | — | 1 | — | — | 3 |

| ATIII <40% | 1 | — | — | 1 | 2 (1) | — | 4 |

| Creatinine >3xN | 4 (2) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 (1) | — | 10 (1) |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

AP, alkaline phosphatase; ATIII, antithrombin III; GOT/GPT, glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase/glutamate pyruvate transaminase; —, none.

Discussion

In this largest prospective trial for adult patients with Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia with 363 evaluable patients from 98 centers, the high rate (86%) of patients receiving the full proposed protocol reflected that the combined chemoimmunotherapy approach was feasible in such a multicenter approach.

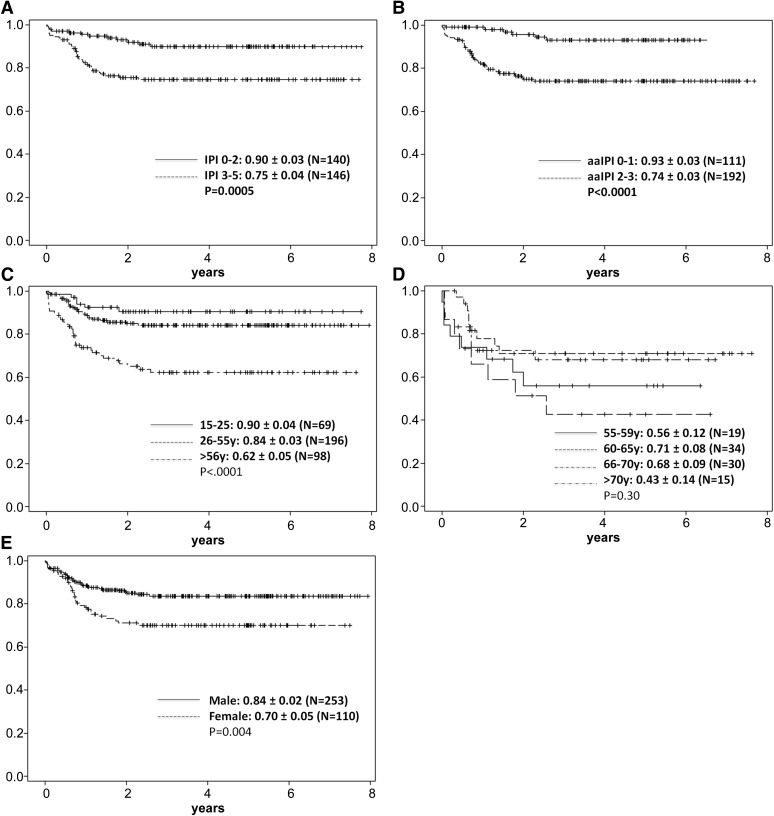

The overall CR rate of 88% was high but not significantly superior to (1) that obtained in the study B-ALL/NHL90 without rituximab (83% for Burkitt lymphoma, 75% for Burkitt leukemia),7 (2) the CR rate observed by Thomas et al,8 or (3) the CR rate reported in a recent comparison using a similar chemotherapy backbone with and without rituximab.11,20 However, there are no randomized or matched-pair comparisons with respect to CR rates with and without rituximab. The long-term outcome could be substantially improved, with an OS rate of 80% and a PFS rate of 75% at >7 years, reflecting a high cure rate, since the few relapses occurred mostly within the first year. In adolescents aged 15 to 25 years, the OS rate of 90% is equal to best results achieved in adolescents treated according to pediatric protocols, albeit with higher doses of methotrexate and without rituximab. Remarkably, the cohort of 130 adults aged 26 to ≤55 years also had a promising OS rate of 84%. The outcome of the 98 elderly patients >55 years, the largest cohort of this age hitherto reported, with an OS rate of 62% and a PFS rate of 60%, was inferior but still encouraging, indicating that a reduced-intensity regimen was sufficiently effective in older Burkitt lymphoma patients. In most trials, the results for elderly Burkitt patients are inferior to those of the younger cohorts20-23; in only a few patients are the results similar.24,25 When the patients >55 years old were analyzed according to the age subgroups 56 to 59 years, 60 to 65 years, 66 to 70 years, and >70 years (Figure 4; supplemental Table 1), the CR rates were similar: 74%, 91%, 83%, and 80%, respectively. Respective OS rates were 56%, 71%, 68%, and lower in the oldest age group (43%) but without statistically significant difference (P = .75). Again, this analysis underlines that the protocol is effective in this older patient population, but attempts still have to be undertaken to decrease the relapse incidence. To reduce particularly those relapses in the bone marrow and CNS, a moderate dose of cytarabine (1 g/m2) is now included in 2 cycles (C1, C2) for this age cohort.

Figure 4.

Five-year probability of OS in Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia patients according to risk factors. (A) Five-year probability of OS according to IPI score: 0-2 (n = 140), 0.90 ± 0.03; 3-5 (n = 146), 0.75 ± 0.04 (P = .0005). (B) Five-year probability of OS according to aaIPI score; 0-1 (n = 111), 0.93 ± 0.03; 2-3 (n = 192), 0.74 ± 0.03 (P < .0001). (C) Five-year probability of OS according to age: 15 to 25 years (n = 69), 0.90 ± 0.04; 26 to 55 years (n = 196), 0.84 ± 0.03; >56 years (n = 98), 0.62 ± 0.05 (P < .0001). (D) Five-year probability of OS according to age >55 years: 55 to 59 years (n = 19), 0.56 ± 0.12; 60 to 65 years (n = 34), 0.71 ± 0.08; 66 to 70 years (n = 30), 0.68 ± 0.09; >70 years (n = 15), 0.43 ± 0.14 (P = .3). (E) Five-year probability of OS according to gender: male (n = 253), 0.84 ± 0.02; female (n = 110), 0.70 ± 0.05 (P = .004).

Interestingly, there was a strong influence of gender on the OS observed in another adult Burkitt trial.16 In our study, 70% of the patients were male, with an OS rate of 84% ± 2% compared to 70% ± 5% for female patients. The difference, as evident from Figure 4, was a higher rate of events between 0.5 and 1.5 years in the female cohort. This is in contrast to a better outcome of female patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab plus CHOP, where the explanation is a prolonged half-life of rituximab in elderly female patients.26,27 In our Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia cohort, reasons for the inferior outcome of the female patients are as yet unclear.

Other study groups have recently conducted trials on Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia, adding rituximab. When rituximab was added to the regimen of cyclophosphamide/vincristine/adriamycin/dexamethasone/HD-MTX/high-dose cytarabine8 twice in the first 4 chemotherapy cycles, 86% of 31 patients with Burkitt lymphoma or Burkitt leukemia (including 9 patients ≥60 years) achieved CR, and the 3-year OS rate was 89%, with no additional toxicity compared to the previous protocol of chemotherapy only. Rituximab was also added to the regimen of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, high-dose methotrexate, ifosfamide, etoposide, and high-dose cytarabine with a median of 4 doses in 40 patients. The CR rate for patients given the regimen with rituximab vs no rituximab was 90% vs 85%, and the respective 3-year OS rate was 77% vs 66%.28 Because the outcome for the patients given the regimen with rituximab was not significantly superior, it has been considered whether more frequent dosing of rituximab might provide the optimal benefit. In another trial of 30 patients in which rituximab was added to the above-mentioned regimen, 93% achieved CR22; PFS was significantly lower in older patients (49% in those >60 years vs 93% in those ≤60 years; P = .03), thus leaving outcome of elderly patients a priority.

Two European study groups have also used the GMALL-B-ALL/NHL2002 protocol reported here, confirming the promising results. The Spanish study group applied it in 36 patients, of whom 53% were HIV infected.29 For HIV-negative and HIV-positive patients, the CR rates were 88% and 84%, and the 2-year OS rates were 82% vs 73%. The full protocol could be applied in 68% of HIV-positive patients. It was concluded that such a regimen is applicable in HIV-positive patients. The Northern Italy Leukemia Group adapted the same protocol to treat 105 adult patients, 55 with Burkitt lymphoma and 50 with Burkitt leukemia.30 The CR rate was 79%, and at 2 years, 61% were alive; patients >55 years had a poorer outcome, with an OS rate of 28% compared with 89% in younger patients.

In a trial by the Cancer and Leukemia Group B, 105 adult patients with Burkitt or Burkitt-like leukemia/lymphoma received the modified GMALL study B-NHL86 protocol with rituximab.20 The CR rate was 83%; the 4-year event-free survival rate, 74%; and the OS rate, 78%; and there was a substantial age difference, with a remission duration of 81% vs 54% for the cohort >60 years old (27%).

Recently, the regimen of dose-adjusted etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and rituximab was tested in 19 HIV-negative patients, and a lower-dose short-course combination of this regimen including a double dose of rituximab was tested in 11 HIV-positive patients. The PFS in the two cohorts was 95% and 100%, respectively, but the overall median age was 33 years; only 10% had high-risk disease.25 All these studies that included rituximab undoubtedly improved the outcome for younger Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia patients but still left the need for improved outcomes in elderly patients: according to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program database (2007), 59% of Burkitt lymphoma cases occurred in patients older than 40 years.14,21

The major toxicity in patients <55 years was myelosuppression and corresponding cytopenias (particularly in cycle A), leading to infections. This toxicity pattern was even more pronounced in patients aged >55 years. The median duration of neutropenia grade 4 was 9 days, leading to infections, causing a higher death rate during induction. Mucositis, a severe side effect in this study, is attributable to the long exposure to methotrexate as a 24-hour continuous infusion. However, shortening of the methotrexate application time did not seem advisable, because in a randomized childhood ALL trial, shorter methotrexate application over 4 hours resulted in a lower event-free survival rate.31

In Burkitt lymphoma, there was a significant difference in outcome for patients with an IPI score of 0-2 and those with an IPI score of ≥3 (P = .03). Also, female gender had a significant adverse influence on OS (P = .03), as observed in other Burkitt lymphoma studies.16 CNS disease at diagnosis or elevated LDH had no adverse prognostic impact. In this study, starting in 2002 with a large number of hospitals, molecular markers analysis was not mandatory. In the limited number of patients analyzed, there was no difference between those with typical karyotype aberration or c-myc positivity compared to those without (Table 1). Thus, patients with a potential inferior prognosis, such as double-hit lymphomas or those with 7q or 13q as a secondary chromosomal aberration, could not be identified.32

Future progress might be achieved by such diagnostic measures as the detection of residual disease in Burkitt lymphoma by positron emission tomography, which could not be implemented in this study starting in 2002 for all of the participating centers. The evaluation of minimal residual disease in Burkitt leukemia in patients with initial bone marrow involvement, as pioneered in children,33 may identify early vs late responders. New therapeutic options could include the intensification of rituximab, newer anti-CD20 antibodies, or the application of other monoclonal antibodies targeting CD19, an antigen highly expressed in Burkitt lymphoma. The bispecific antibody (CD3/CD19) blinatumomab, already successfully explored in adult minimal residual disease–positive ALL patients,34 may also be promising in Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia patients, as well as CD19-directed chimeric antigen receptor–modified T cells.35

Authorship

Contribution: D.H. and N.G. designed and coordinated the study; N.G. performed the statistical analysis; D.H. wrote the manuscript; and all coauthors contributed to patient care, supported the study conduct, and contributed to the final report.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for D.H. is Onkologikum, Frankfurt am Museumsufer, Frankfurt am Main, Germany; e-mail: dieter.hoelzer@onkologikum-frankfurt.de.

For a complete list of German Multicenter Study Group for Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia members, please go to the GMALL Web site at http://www.kompetenznetz-leukaemie.de/.

Correspondence: Dieter Hoelzer, Department of Internal Medicine II, University Hospital, Theodor-Stern-Kai 7, 60596 Frankfurt am Main, Germany; e-mail: hoelzer@em.uni-frankfurt.de.

Acknowledgments

We thank the German Multicenter Study Group for Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (GMALL) for entering patients into the trial and for follow-up documentation, Ms Sabine Hug for data management, and Ms Lena-Solveig Lenz for assistance in manuscript preparation.

This study was supported by the Deutsche José Carreras Leukämie-Stiftung (DJCLS H06/03, H09/01f).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

References

- 1.Murphy SB, Bowman WP, Abromowitch M, et al. Results of treatment of advanced-stage Burkitt’s lymphoma and B cell (SIg+) acute lymphoblastic leukemia with high-dose fractionated cyclophosphamide and coordinated high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine. J Clin Oncol. 1986;4(12):1732–1739. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1986.4.12.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Magrath I, Adde M, Shad A, et al. Adults and children with small non-cleaved-cell lymphoma have a similar excellent outcome when treated with the same chemotherapy regimen. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(3):925–934. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.3.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patte C, Philip T, Rodary C, et al. Improved survival rate in children with stage III and IV B cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and leukemia using multi-agent chemotherapy: results of a study of 114 children from the French Pediatric Oncology Society. J Clin Oncol. 1986;4(8):1219–1226. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1986.4.8.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reiter A, Schrappe M, Ludwig WD, et al. Favorable outcome of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood: a report of three consecutive studies of the BFM group. Blood. 1992;80(10):2471–2478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoelzer D, Ludwig WD, Thiel E, et al. Improved outcome in adult B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1996;87(2):495–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diviné M, Casassus P, Koscielny S, et al. GELA; GOELAMS. Burkitt lymphoma in adults: a prospective study of 72 patients treated with an adapted pediatric LMB protocol. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(12):1928–1935. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoelzer D, Arnold R, Diedrich H, et al. Successful treatment of Burkitt’s NHL and other high-grade NHL according to a protocol for mature B-ALL [abstract]. Blood. 2002;100(11). Abstract 595.

- 8.Thomas DA, Cortes J, O’Brien S, et al. Hyper-CVAD program in Burkitt’s-type adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(8):2461–2470. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moleti ML, Testi AM, Giona F, et al. CODOX-M/IVAC (NCI 89-C-41) in children and adolescents with Burkitt’s leukemia/lymphoma and large B-cell lymphomas: a 15-year monocentric experience. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48(3):551–559. doi: 10.1080/10428190601078944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mead GM, Barrans SL, Qian W, et al. UK National Cancer Research Institute Lymphoma Clinical Studies Group; Australasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma Group. A prospective clinicopathologic study of dose-modified CODOX-M/IVAC in patients with sporadic Burkitt lymphoma defined using cytogenetic and immunophenotypic criteria (MRC/NCRI LY10 trial). Blood. 2008;112(6):2248–2260. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-145128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rizzieri DA, Johnson JL, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Intensive chemotherapy with and without cranial radiation for Burkitt leukemia and lymphoma: final results of Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study 9251. Cancer. 2004;100(7):1438–1448. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raponi S, De Propris MS, Intoppa S, et al. Flow cytometric study of potential target antigens (CD19, CD20, CD22, CD33) for antibody-based immunotherapy in acute lymphoblastic leukemia: analysis of 552 cases. Leuk Lymphoma. 2011;52(6):1098–1107. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.559668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoelzer D. Novel antibody-based therapies for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011:243-249. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Costa LJ, Xavier AC, Wahlquist AE, Hill EG. Trends in survival of patients with Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia in the USA: an analysis of 3691 cases. Blood. 2013;121(24):4861–4866. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-475558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castillo JJ, Winer ES, Olszewski AJ. Population-based prognostic factors for survival in patients with Burkitt lymphoma: an analysis from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. Cancer. 2013;119(20):3672–3679. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wästerlid T, Brown PN, Hagberg O, et al. Impact of chemotherapy regimen and rituximab in adult Burkitt lymphoma: a retrospective population-based study from the Nordic Lymphoma Group. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(7):1879–1886. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Stein H, et al. A revised European-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: a proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 1994;84(5):1361–1392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, et al. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(4):1244. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hennipman B, de Vries E, Bökkerink JP, Ball LM, Veerman AJ. Intrathecal vincristine: 3 fatal cases and a review of the literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;31(11):816–819. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181b83fba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rizzieri DA, Johnson JL, Byrd JC, et al. Alliance for Clinical Trials In Oncology (ACTION) Improved efficacy using rituximab and brief duration, high intensity chemotherapy with filgrastim support for Burkitt or aggressive lymphomas: cancer and Leukemia Group B study 10 002. Br J Haematol. 2014;165(1):102–111. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly JL, Toothaker SR, Ciminello L, et al. Outcomes of patients with Burkitt lymphoma older than age 40 treated with intensive chemotherapeutic regimens. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2009;9(4):307–310. doi: 10.3816/CLM.2009.n.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corazzelli G, Frigeri F, Russo F, et al. RD-CODOX-M/IVAC with rituximab and intrathecal liposomal cytarabine in adult Burkitt lymphoma and ‘unclassifiable’ highly aggressive B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2012;156(2):234–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kasamon YL, Brodsky RA, Borowitz MJ, et al. Brief intensive therapy for older adults with newly diagnosed Burkitt or atypical Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54(3):483–490. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.715346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas DA, Faderl S, O’Brien S, et al. Chemoimmunotherapy with hyper-CVAD plus rituximab for the treatment of adult Burkitt and Burkitt-type lymphoma or acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2006;106(7):1569–1580. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunleavy K, Pittaluga S, Shovlin M, et al. Low-intensity therapy in adults with Burkitt’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(20):1915–1925. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Müller C, Murawski N, Wiesen MH, et al. The role of sex and weight on rituximab clearance and serum elimination half-life in elderly patients with DLBCL. Blood. 2012;119(14):3276–3284. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-380949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfreundschuh M, Müller C, Zeynalova S, et al. Suboptimal dosing of rituximab in male and female patients with DLBCL. Blood. 2014;123(5):640–646. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-07-517037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barnes JA, Lacasce AS, Feng Y, et al. Evaluation of the addition of rituximab to CODOX-M/IVAC for Burkitt’s lymphoma: a retrospective analysis. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(8):1859–1864. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oriol A, Ribera JM, Bergua J, et al. High-dose chemotherapy and immunotherapy in adult Burkitt lymphoma: comparison of results in human immunodeficiency virus-infected and noninfected patients. Cancer. 2008;113(1):117–125. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Intermesoli T, Rambaldi A, Rossi G, et al. High cure rates in Burkitt lymphoma and leukemia: Northern Italy Leukemia Group study of the German short intensive rituximab-chemotherapy program. Haematologica. 2013;98(11):1718–1725. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.086827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mikkelsen TS, Sparreboom A, Cheng C, et al. Shortening infusion time for high-dose methotrexate alters antileukemic effects: a randomized prospective clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(13):1771–1778. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.5340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poirel HA, Cairo MS, Heerema NA, et al. FAB/LMB 96 International Study Committee. Specific cytogenetic abnormalities are associated with a significantly inferior outcome in children and adolescents with mature B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: results of the FAB/LMB 96 international study. Leukemia. 2009;23(2):323–331. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mussolin L, Pillon M, Conter V, et al. Prognostic role of minimal residual disease in mature B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia of childhood. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(33):5254–5261. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.3159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Topp MS, Kufer P, Gökbuget N, et al. Targeted therapy with the T-cell-engaging antibody blinatumomab of chemotherapy-refractory minimal residual disease in B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients results in high response rate and prolonged leukemia-free survival. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(18):2493–2498. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.7270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brentjens RJ, Davila ML, Riviere I, et al. CD19-targeted T cells rapidly induce molecular remissions in adults with chemotherapy-refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(177):177ra38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]