Background: Retroelements are frequently under stringent control by RNAi mechanisms.

Results: Disruption of the Argonaut AgnA in Dictyostelium leads to loss of retroelement siRNAs, retroelement-encoded proteins, and accumulation of a cytoplasmic cDNA that is abolished with additional deletion of AgnB.

Conclusion: Two Argonautes with different functions are involved in retroelement regulation.

Significance: AgnA is required to minimize retroelement expression.

Keywords: Argonaute, Gene Silencing, RNA Interference (RNAi), Small Interfering RNA (siRNA), Transposable Element (TE)

Abstract

The retrotransposon DIRS-1 is the most abundant retroelement in Dictyostelium discoideum and constitutes the pericentromeric heterochromatin of the six chromosomes in D. discoideum. The vast majority of cellular siRNAs is derived from DIRS-1, suggesting that the element is controlled by RNAi-related mechanisms. We investigated the role of two of the five Argonaute proteins of D. discoideum, AgnA and AgnB, in DIRS-1 silencing. Deletion of agnA resulted in the accumulation of DIRS-1 transcripts, the expression of DIRS-1-encoded proteins, and the loss of most DIRS-1-derived secondary siRNAs. Simultaneously, extrachromosomal single-stranded DIRS-1 DNA accumulated in the cytoplasm of agnA− strains. These DNA molecules appear to be products of reverse transcription and thus could represent intermediate structures before transposition. We further show that transitivity of endogenous siRNAs is impaired in agnA− strains. The deletion of agnB alone had no strong effect on DIRS-1 transposon regulation. However, in agnA−/agnB− double mutant strains strongly reduced accumulation of extrachromosomal DNA compared with the single agnA− strains was observed.

Introduction

Argonaute proteins are key players in all known RNA-mediated gene silencing pathways and are highly conserved among eukaryotes. Small regulatory RNAs of 20–30 nucleotides guide the Argonaute proteins to complementary RNA targets that lead typically to reduced expression levels of the respective genes. Silencing is achieved by mRNA degradation, translational inhibition, or by chromatin remodeling (1). The main classes of small regulatory RNAs are small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), microRNAs, and piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) that differ in their biogenesis and the mode of target regulation.

The canonical triggers of siRNA-mediated gene silencing pathways are linear and perfectly base-paired dsRNA molecules that are processed by Dicer in the cytoplasm (2). Endogenous siRNAs arise for example from transposons, pericentromeric repeats, or other repetitive sequences, whereas exogenous siRNAs originate from viruses or transgenes (3).

The primary siRNA duplex is loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex that contains an Argonaute protein at its center. After unwinding the duplex and removal of the passenger strand, the RNA-induced silencing complex assembly is completed (4). The siRNA usually guides the complex to perfectly complementary target RNAs that are cleaved by the Piwi domain and further degraded by exonucleases (5). Some siRNA classes induce transcriptional rather than posttranscriptional silencing. In plants for example, cis-acting siRNAs (casiRNAs) derived from transposons initiate heterochromatin formation at loci from which they originate (6, 7).

Some organisms like plants, Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Caenorhabditis elegans require RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRPs)3 for efficient RNA-mediated gene silencing on the transcriptional or posttranscriptional level.

In the case of transgenes and some viruses, plant RdRPs initiate an RNAi response by catalyzing the synthesis of double-stranded RNA molecules (8, 9). This can lead to a >20-fold amplification of viral siRNAs and reduces virus accumulation efficiently (10). However, the molecular basis of RdRP target specificity is not yet well understood.

In contrast to plants, C. elegans RdRPs can directly synthesize short secondary siRNAs from an RNA template (11, 12). These secondary siRNAs are of antisense polarity and loaded onto Argonaute proteins of the WAGO-clade (12). The complexes contribute to target degradation, transposon silencing, and chromosomal segregation (13). Primary siRNAs, which are produced by Dicer, and secondary siRNAs, which are individual RdRP products, differ in that the latter have a 5′-triphosphate (11, 12). Primary siRNAs that associate with the Argonaute protein Rde-1 (14) constitute only a small amount of the siRNA pool in C. elegans and thus appear insufficient for robust gene silencing (15, 16). Therefore, the main function of primary RNA-induced silencing complexes appears to guide the RdRP machinery to the target RNAs for siRNA amplification (15).

From an evolutionary point of view, the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum is an interesting model as it branched off from the tree of life after the plants but before the animal-fungi split (17). The amoebae are characterized by their ability to alternate between uni- and multicellularity; they grow as single cells, but upon starvation they form multicellular organisms in a developmental process that culminates in a fruiting body consisting predominantly of stalk and spore cells (18).

D. discoideum is suitable in studying RNA-mediated gene silencing pathways (19) as all RNAi key components, namely the Dicer homologues DrnA and DrnB, the RdRP homologues RrpA to RrpC, and five Argonaute proteins AgnA to AgnE, homologous to the Piwi-clade, are encoded in the genome (20). RrpC is known to be involved in the accumulation of DIRS-1 siRNAs and transposon silencing (21).

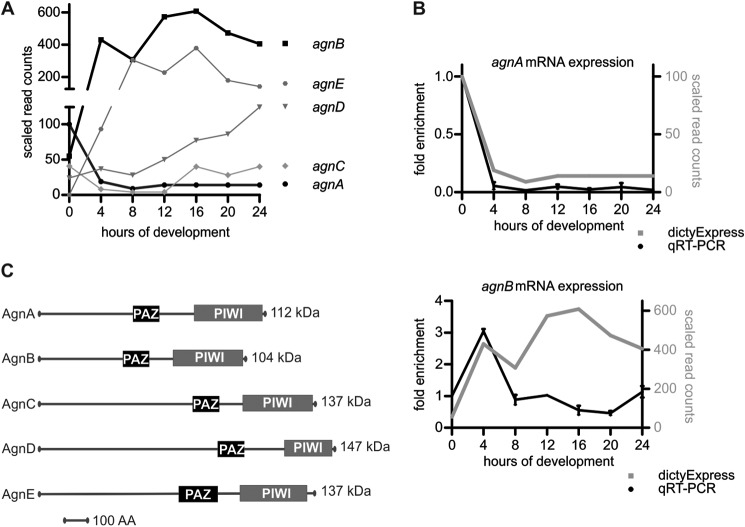

The Argonaute proteins are expressed at very different levels and at different times in development (Fig. 1A) (22). Developmental regulation is not surprising as retroelements and microRNAs, which are most likely regulated by Argonaute proteins, are differentially expressed in the developmental cycle (23, 24), but so far no biological functions have been assigned to these proteins.

FIGURE 1.

mRNA expression and domain composition of D. discoideum Argonautes. A, mRNA expression profiles of Argonaute genes in the Ax4 wt during development derived from deep sequencing. The figures was compiled from data in Rot et al. (22). B, relative expression of agnA and agnB mRNAs during development was analyzed by qRT-PCR in the Ax2 wild-type strain. cinD mRNA was used as a housekeeping gene for quantification. The expression level for each gene is given relative to its expression in vegetative cells (0 h = 1). The data (black line) are plotted in comparison to the deep sequencing data (gray line) (22). n = 2 (biological replicates). Error bars: mean with S.D. C, schematic representation of PAZ and PIWI domains of the different Argonaute proteins.

Transposons and repetitive elements add up to 10% of the D. discoideum genome (25). Transposable elements can be classified in long terminal repeat (LTR) retroelements, non-LTR retroelements, and DNA transposons. The most abundant transposable element in D. discoideum is the LTR retrotransposon DIRS-1 (26), which is present in 16 complete and up to 200 incomplete copies (27, 28). DIRS-1 elements are only found in clusters at the subtelomeric centromeres of all six chromosomes (17, 29).

Mobility of LTR retrotransposons is mediated by almost full-length transcripts that are synthesized by RNA polymerase II in the nucleus using a promoter within the 5′-LTR. The LTRs flank an internal region where structural proteins and enzymes for replication and subsequent transposition are encoded. The gag ORF encodes a protein that forms cytoplasmic or virus-like particles within which reverse transcription takes place. The pol ORF encodes several enzymes, among them the reverse transcriptase (RT) and an integrase that mediates cDNA insertion into the genome (30).

DIRS-1 belongs to the DIRS group of LTR retrotransposons that have some unusual structural features compared with typical LTR elements: the three overlapping reading frames encode 1) a putative Gag protein (ORF1), 2) a tyrosine recombinase (ORF2) instead of an integrase (31), and 3) a RT, an RNase H, and a methyltransferase domain in ORF3 (Fig. 2A) (28). The flanking LTRs are inverted (ITR), they are not absolutely identical in their sequence, and a 27-bp extension is present at the edge of the right ITR (27, 31). In addition, the element harbors an internal segment close to the right ITR, which is referred to as the internal complementary region, because it contains the reverse complement of the outer nucleotides of both ITRs (31). Based on these specific features, models for replication and transposition have been proposed (31, 32) but without any experimental evidence so far. According to the model, the internal complementary region is suggested to serve as a template to restore the ITR sequences during cDNA synthesis. Self-ligation of the cDNA would generate a single-stranded circular DNA. After conversion to a double-stranded circle, site-specific recombination could occur. This is supported by the fact that DIRS-1 targets pre-existing DIRS-1 elements for integration without generating a target site duplication (31).

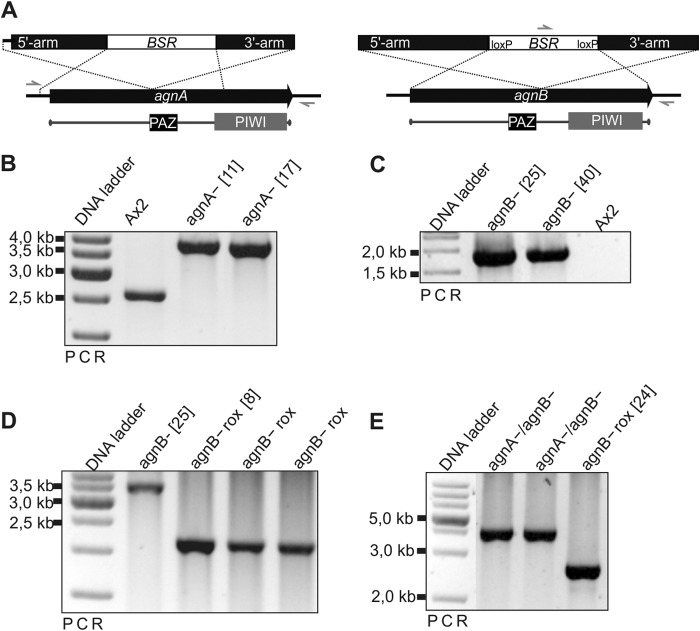

FIGURE 2.

Validation of agnA and agnB and agnA/B gene disruptions. A, schematic representation of the agnA and agnB gene disruption constructs and of the Bsr cassette insertion. Arrows indicate primers used to verify successful gene disruption. B, the agnA gene disruption was identified by PCR on genomic DNA using a primer set (BB059/BB060) that binds outside of the targeting fragment. Expected fragment sizes are 2645 bp for the Ax2 wild type and 3899 bp for the agnA gene disruption. C, the agnB gene disruption was identified by PCR using a primer set (Bsr G1–5A/BB048) where the forward primer binds in the Bsr cassette and the reverse primer binds downstream of the targeted fragment in the agnB terminator region. In the case of the agnB gene disruption, a fragment of 1935 bp is expected, whereas the Ax2 wild type gives no PCR product. D, removal of the Bsr cassette from the agnB knock-out strains was confirmed by PCR using a primer set (BB046/BB047) that flanks the original insertion site of the resistance cassette. After successfully removing of the Bsr cassette, the PCR reaction results in a shorter product of 2198 bp for agnB− rox strains compared with 3606 bp for the original agnB− strains. E, the agnA gene disruption in the agnB knock-out background was identified by PCR using a primer set (BB059/BB060) that binds outside of the targeted fragment. Expected fragment sizes are 2645 bp for single agnB− rox strains and 3899 bp for agnA−/B− strains.

Transcription of the 4.8-kb DIRS-1 element starts within the left ITR and terminates close to the extended sequence of the right ITR (33). DIRS-1 generates a population of several polyadenylated RNAs that accumulate during development and upon heat shock (26). Recently, a long antisense transcript driven by the right ITR has been identified in the D. discoideum wild type strain and in several mutants (21). Bidirectional transcription and Dicer cleavage of the resulting double-stranded RNAs could, therefore, be the source of primary siRNAs. Hinas et al. (23) showed that some of the DIRS-1-derived siRNAs are Dicer and some of them are RdRP products.

To elucidate the function of Argonaute proteins in general and specifically in DIRS-1 silencing, we focused on AgnA and AgnB as AgnC, -D, and -E knockouts have no obvious effect on DIRS-1 regulation.4 We find that AgnA is involved in generation of siRNAs and in posttranscriptional regulation of DIRS-1. In contrast, AgnB appears to be an unusual positive regulator of DIRS-1 in that its knock-out abolishes accumulation of DIRS-1 cDNA in an AgnA- strain.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Growth and Transformants

All D. discoideum strains were grown axenically in HL5+ medium (Formedia) supplemented with Blasticidin S and/or Geneticin at concentrations of 10 μg/ml when required. Transformation into the axenic strain Ax2 or derivates was done by electroporation as described previously (34).

For agnA gene (accession number DDB_G0276299) disruption a 2531-bp-long fragment (−222 bp upstream and 2309 bp downstream of the ATG) of the agnA gene was amplified by PCR with primers BB049 and BB050 and ligated into pGEM®-T-Easy. The Blasticidin resistance (Bsr) cassette (35) was cloned in the agnA gene fragment via the endogenous BglII site. The vector for the agnB gene (accession number DDB_G0290377) disruption was generated in the following way; the whole 2963-bp-long agnB gene was amplified by PCR using primers BB184 and BB185. A Bsr cassette flanked by LoxP sites was isolated from the pLPBLP vector (36) and cloned into the endogenous EcoRV site of the agnB gene. Gene disruption plasmids were linearized before transformation. Mutants were analyzed by PCR. For the agnA−/agnB− double mutant, the Bsr cassette from the agnB− strain was removed by transient expression of the Cre recombinase (36). Single, Blasticidin-sensitive clones were examined by PCR and then supertransformed with the agnA gene disruption construct. Single clones of the double mutant were analyzed by PCR. For the analysis of molecular phenotypes, two independent clones each were used.

Overexpressing constructs to monitor 3′-spreading activity in the DIRS-1 element were published previously (21). To analyze 5′-spreading activity, the DIRS-1 ORFs were cut out from the pJET.1.2/blunt cloning vectors (21) with BamHI and SpeI and ligated in the extrachromosomal vector pDM317 (37) that was previously linearized by BglII and SpeI. The ORFs were thus fused to an N-terminal GFP tag. Plasmids were transformed in the Ax2 wild type and the agnA− strain. Two independent transformation populations were used for transitivity analysis. Plasmids were transformed into the Ax2 wild type and the agnA− strain. Two independent transformation populations were used for transitivity analysis.

Developmental Time Course

The Ax2 wt strain was grown in shaking culture to a density of 2,5 × 106 cells/ml. 5 × 108 cells were chilled on ice for 10 min before centrifugation at 390 rcf/4 °C for 3 min. Cells were washed 3 times in cold Sorensen phosphate buffer (2 mm Na2HPO4, 15 mm KH2PO4, pH 6.5). Cell density was adjusted to 6.8 × 107 cells/ml with Sorensen buffer. 750 μl of cells each were distributed on autoclaved nitrocellulose filters (47-mm diameter; Sartorius). Cells were incubated at 22 °C in a moist chamber. After 0, 4, 8, and 12 h, cells from one filter and after 16, 20, and 24 h cells from two filters were harvested in 10 ml of phosphate buffer and centrifuged at 390 rcf and 4 °C for 5 min, and RNA was extracted as described previously (38).

Oligonucleotides

DNA oligonucleotides (Invitrogen) used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Primer name | Sequence | Description |

|---|---|---|

| BB049_agnA_KO_outer_fw #2309 | CCAAAAAAAAAAAAATCTTTGAAAAGTCAGCG | agnA gene disruption arm |

| BB050_agnA_KO_inner_rev #2310 | GAAAAGATACATTGAGTTAAAACTCTGAATTGG | |

| BB184 | CTGCAGAAATGATCCCAAAAAAACAAAAAGGATTC | agnA gene disruption arm |

| BB185 | GGATCCTTAAAGGAAGAATAATTTATCAGATAATTGAGG | |

| BB059_agnA_wo_loxP_N_outer (#2319) | TAGTATACCTTACCATTAATAAAAAC | PCR primers to verify agnA gene disruption |

| BB060_agnA_wo_loxP_C_outer (#2320) | GCAACCACTTGTTGTTTCAATTTG | |

| Bsr G1–5A (#385) | CGCTACTTCTAGTAATTCTAGA | PCR primers to verify agnB gene disruption |

| BB048_agnB_outer_rev_2 (52 °C) (#2308) | ATTTTGATTGTGTGTTTATTATTATGTGATG | |

| BB046_agnB_outer_fw (51 °C) (#2306) | CTATTTATCTTTTAAACAAATACATAATATTTTC | Verification of BsR cassette removal by PCR |

| BB047_agnB_outer_rev (54 °C) (#2307) | TACTTGAGAGACTAAAAAGAAATCATACC | |

| BB141_DIRS_1_sense (#2916) | TAGAGGCATCATTATTATTAACAGT | Probe1 (P1) |

| BB145_DIRS_3_sense (#2920) | GAACAAACGTCCACCTACTGGTAAG | Probe2 (P2) |

| BB153_DIRS_7_sense (#2928) | TACTTTGAGAGTTGAAGGTTCCCAT | Probe3 (P3) |

| cinD-1 qPCR fw (#1923) | GCCAGAAATGCTTTGAAAATGACA | qPCR primers |

| cinD-1_qPCR rev (#1924) | GAGTGGTTTGCCAATTTCTTTTCCT | |

| DIRS LE for | AGTAAATCCAGTAGTGGGAGT | qPCR primers DIRS-1 A1 |

| DIRS LE rev | GTGATGCAATCTGATTTCGGA | |

| MJD83 | GGAAGAAGAAAGCCCCATTC | qPCR primers DIRS-1 A2 |

| MJD84 | CAGAGAAGCCATAGCGGAAC | |

| DIRS small RNA (Hinas et al., 2007) | ACCTCGATTGGAGTCAATGGA | DIRS-1 siRNA (P4) |

| DIRS LE for T7 | GTTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGCAAATCCAGTAGTGGGAGT | T1 |

| DIRS LE rev | GTGATGCAATCTGATTTCGGA | |

| DIRS LE for | AGTAAATCCAGTAGTGGGAGT | T2 |

| DIRS LE rev T7 | GTTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTGATGCAATCTGATTTCGGA | |

| tRNA Asp [SM5_tRNA_Asp_mid] | CCCGGGCCTTTCGCGTGACAGGCGAAAATCCTCACCACTAGACCAACAAG | Cytoplasmic control |

| #2642_SM_58 | GGCATGGCACTCTTGAAAAAG | Probe5 (P5) |

| DM_146 | CTATAACTCACACAATGTATACATCATG | α Sense GFP siRNAs |

| DM_147 | CATGATGTATACATTGTGTGAGTTATAG | α Antisense GFP siRNAs |

| BB142_DIRS_1_AS (#2917) | ACTGTTAATAATAATGATGCCTCTA | Probe6 (P6) |

| BB144_DIRS_2_AS (#2919) | ACCTTTGCTTCTTATGTCAAGTATG | Probe7 (P7) |

| BB146_DIRS_3_AS (#2921) | CTTACCAGTAGGTGGACGTTTGTTC | Probe8 (P8) |

| BB148_DIRS_4_AS (#2923) | GTTGGAAAACAATGCCGTTCGGGTT | Probe9 (P9) |

| BB150_DIRS_5_AS (#2925) | CCCATTCCTCAAGATGTCAAGTCAG | Probe 10 (P10) |

| BB152_DIRS_6_AS (#2927) | CAAGAGTTACAACTGGCAACTGAAG | Probe 11 (P11) |

| BB154_DIRS_7_AS (#2929) | ATGGGAACCTTCAACTCTCAAAGTA | Probe 12 (P12) |

| BB156_DIRS_8_AS (#2931) | AAAGAAGTGGTGTTGTTTCAATATT | Probe 13 (P13) |

| #896_Dirs_LTR_fw | ATCAAATTGTTTTAGTTTTTA | Probe 14 (P14) |

| DM_173 | TATTTGGGAATTCCTCCTATATATATTTAAG | PCR primer #1 |

| BB_143 | CATACTTGACATAAGAAGCAAAGGT | PCR primer #2 |

| #896 | ATCAAATTGTTTTAGTTTTTA | PCR primer #3 |

| DM_135 | AAGCTTTTAAAAATTTAATTTATTAAATTATATTTTA | PCR primer #4 |

| MJD83 (#1927) | GGAAGAAGAAAGCCCCATTC | PCR primer #5 |

| BB_141 | TAGAGGCATCATTATTATTAACAGT | PCR primer #6 |

| Skipper A1 fw | GACTCTTCGTCCCACTGAAGTCGATG | Skipper amplicon A1 |

| Skipper A1 rev | GATGCAGCACCATTGTCCATAATGG |

Analysis of RNA

RNA was extracted from 2 × 107 cells of axenically grown D. discoideum cells as previously described (38). For detection of small RNAs, 10 μg of total RNA were separated by gel electrophoresis on 11% polyacrylamide gels (20 mm MOPS, pH 7.0, 7 m urea). RNA was transferred by semidry blot to a nylon membrane (Amersham Biosciences HybondTM-NX) for 10 min at 20 V. It was then chemically cross-linked to the membrane as described by Pall and Hamilton (39). Blots were probed with 5′-radio-labeled DNA oligonucleotides as described by Hinas et al. (23). Hybridization with an oligonucleotide complementary to small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA6; DdR-6) was used as a loading control. Probes are summarized in Table 1.

For the detection of DIRS-1 transcripts, 10 μg of total RNA were separated by gel electrophoresis on a 1.6% agarose gel in 1× MOPS (20 mm MOPS, 5 mm NaAc, 1 mm EDTA, pH 7.0). RNA samples (2 μg/μl) were denatured in 2 μl of 10× MOPS buffer, 2 μl of 37% formaldehyde, and 10 μl of formamide by heating for 5 min at 70 °C, 6× loading buffer was added, and samples were run on an agarose gel. After capillary transfer to a nylon membrane (Amersham Biosciences HybondTM-NX), RNA was cross-linked by UV irradiation (312 nm, 0.560 Joule/cm2). Prehybridization and hybridization were carried out in Church buffer (40) (250 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.2, 1 mm EDTA, 7% w/v SDS, 1% w/v BSA) using T4-PNK (Thermo Scientific) 32P-labeled oligonucleotides or random-primed-labeled PCR products using Klenow Fragment (Thermo Scientific) (41). All blots were washed as described in Hinas et al. (23). Hybridization signals were detected after exposure to an image plate and read-out on phosphorimaging (FLA-7000, Fujifilm).

Deep Sequencing of Small RNAs

Cells from axenically grown D. discoideum Ax2 and rrpC− and agnA− strains were collected by centrifugation for 3 min at 390 rcf at 4 °C and washed once with 10 ml of Sorensen buffer. Small RNAs (<200 nt) were extracted from 1 × 107 cells using the NucleoSpin® miRNA Kit (Macherey-Nagel). RNA isolation was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA libraries of these small RNA fractions were sequenced on an Illumina platform.

Specifically, cDNA synthesis, Illumina sequencing, and read mapping were performed as follows; RNA samples were poly-A-tailed, and the 5′-triphosphate was converted into 5′-P before an RNA adaptor was ligated. A poly-T-oligo was then used as primer for cDNA synthesis, and the resulting cDNAs were PCR-amplified. The cDNA libraries were sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq 2000 machine, resulting in around 5.3, 4.9, and 5.8 million reads with sufficient quality for the Ax2, the agnA−, and the rrpC− strain, respectively. The processed (clipped and quality trimmed) reads were mapped against the full-length DIRS-1 element SB41 (accession number M11339.1) by the short read mapper segemehl (42) and the Dictyostelium genome (DDB0169550, DDB0215151, DDB0232428, DDB0232430, DDB0232432, DDB0237465, DDB0215018, DDB0220052, DDB0232429, DDB0232431, DDB0232433). Overall, 34,152 reads of the Ax2 library, 8,350 reads of the agnA− library, and 3,909 reads of the rrpC− library were successfully aligned to the DIRS-1 element. Based on these alignments coverage plots in wiggle format were generated. For reads that map equally well to different places in the DIRS-1 sequence, proportional fractions were added to the coverage values. The data have been deposited in NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (43) and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE56111 (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Quantitative Reverse Transcription (qRT) PCR

For quantitative mRNA expression analysis, qRT-PCR was performed in an Eppendorf realplex light cycler using the SensiFASTTM SYBR® No-ROX One-Step kit (Bioline) by following the manufacturer's instructions. Primer sequences are listed in Table 1. All measurements were carried out in triplicate and averaged. Differential gene expression was calculated by the ΔΔCT method (44) using cinD (accession number DDB_G0273061) as the reference gene.

DNA Isolation and Southern Blot Analysis

Preparation of genomic DNA from isolated nuclei and Southern blot analysis were carried out as described before (45).

Extrachromosomal DIRS-1 DNA from 2 × 107 axenically grown D. discoideum cells was isolated by the GeneJetTM Plasmid Miniprep kit (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total DNA was isolated from 2 × 107 cells using the GeneJET Genomic DNA Purification kit (Thermo Scientific). For Southern blots under semidenaturing conditions, DNA was denatured in 2 μl of 10× MOPS buffer, 2 μl of 37% formaldehyde, and 10 μl of formamide, heated at 70 °C for 5 min, and chilled on ice before loading on a 1.4% 1 x MOPS (20 mm MOPS, 5 mm NaAc, 1 mm EDTA, pH 7.0) agarose gel. The following steps were carried out as described before (45).

Isolation of DNA after Cell Fractionation

A total of 5 × 107 cells were harvested from HL5+ medium and washed in ice-cold Sorensen buffer. Cells were collected at 390 rcf and 4 °C for 5 min. The cell pellet was lysed in 5 ml of nuclear lysis buffer (50 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 40 mm MgCl2, 20 mm KCl, 5% saccharose, and 1% Nonidet P-40). Nuclei were collected by centrifugation at 2680 rcf at 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant, referred to as the cytoplasmic fraction, was transferred into a new tube. Nuclei were resuspended in 5 ml of nuclear lysis buffer without Nonidet P-40. SDS was added to both fractions to a final concentration of 0.7%. After proteinase K and RNase A treatment, proteins were removed by phenol-chloroform extraction. DNA of both fractions was precipitated and resolved in 50 μl of double distilled H2O. For further fractionation 1 ml of cytosolic supernatant was centrifuged at 5,000 × g, 10,000 × g, 15,000 × g, and 20,000 × g. DNA was prepared from pellets, and the supernatants were treated were treated as described above and analyzed by Southern blot.

Nuclease Treatment of Extrachromosomal DIRS-1 DNA

10 μl of cytoplasmic DNA from the agnA− strain were subjected to DNase I, exonuclease III, exonuclease I, S1 nuclease and micrococcal nuclease (Thermo Fisher) in a final volume of 20 μl according to the manufacturer's instructions. After heat inactivation of the respective enzyme, 10 μl of each digest were used for agarose gel electrophoresis and Southern blot analysis. Extrachromosomal DIRS-1 DNA was detected by 32P-labeled probes as indicated.

Isolation of Proteins after Cell Fractionation

1 × 108 cells were lysed, and nuclei were pelleted as described above except that 1 tablet of protease inhibitor (complete, EDTA-free (Roche Applied Science)) was added to 10 ml of lysis buffer. The cytoplasmic supernatant was removed and precipitated by the addition of TCA to a final concentration of 10%. Proteins were collected by centrifugation at 15,000 rcf at 4 °C for 45 min. The protein pellet was washed 4 times with 80% cold acetone. Finally the dry pellet was resuspended in 20 μl of PBS and 20 μl of 2× Laemmli buffer (46). Nuclei were resuspended in 50 μl of PBS and 50 μl of 2× Laemmli buffer.

Western Blot Analysis

Total cell protein was prepared by boiling cells in 1 μl of Laemmli buffer (46)/5 × 104 cells. Protein lysate corresponding to 8 × 105 cells was separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a nylon membrane by wet blot. For detection of proteins, monoclonal antibodies against GFP mAb 264–449-2 (Millipore), against Coronin mAb 176-3-6 (47), and against α-actinin mAb 47-19-2 (48) were used. As secondary antibody, an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat α mouse antibody (Dianova, Hamburg), was used.

RESULTS

Expression Analysis of agnA and agnB mRNA in Development

We analyzed the expression of agnA and agnB mRNAs in the wild-type strain Ax2 by qRT-PCR and compared the data with the deep sequencing-based results in dictyExpress (22) (Fig. 1, A–C). The relative expression of agnA mRNA coincided well with the published data for the Ax4 wild type. However, the developmental regulation of agnB mRNA appeared to be different, as expression did not increase after 8 h of development.

AgnA Prevents Accumulation of Transposon Transcripts

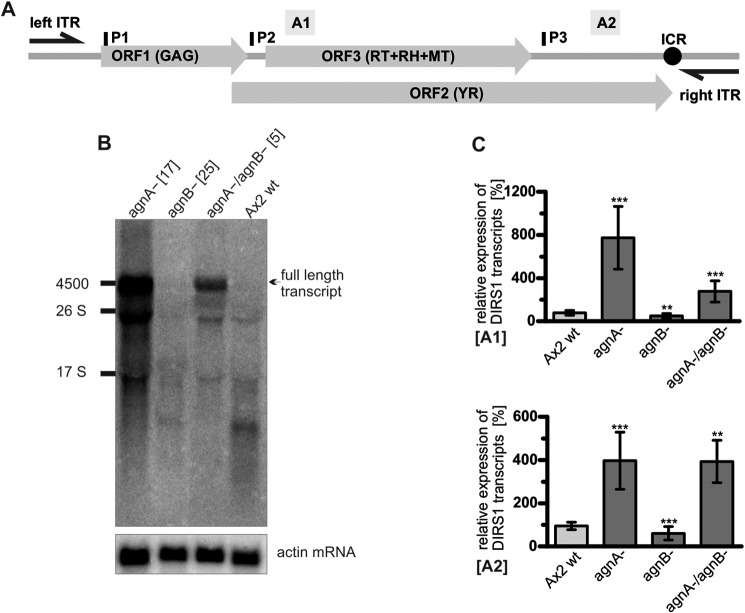

We constructed single knock-out strains of the agnA (agnA−) and the agnB gene (agnB−) as well as double knock-out strains (agnA−/agnB−) (Fig. 2). Multiple independent transformants did not show any significant mutant phenotype in growth and development under laboratory conditions (data not shown). When we analyzed DIRS-1 sense transcripts by Northern blot, we observed an accumulation of full-length ∼4.5-kb transcripts and of shorter variants in the agnA− strain compared with the Ax2 wild type (Fig. 3, A and B). The agnB− strain showed no obvious difference in transcript levels whereas the double knock-out strain was more similar to the agnA− strain. The data revealed that AgnA reduces the accumulation of all DIRS-1 transcripts, including full-length in the cell whereas AgnB had no major effect.

FIGURE 3.

Expression of DIRS-1 transcripts in different D. discoideum knock-out strains. A, schematic representation of a full-length (4869 bp) DIRS-1 element (31) consisting of long inverted terminal repeats (left ITR (330 bp) and right ITR (358 bp)) that flank three open reading frames. ORF1 encodes a putative Gag protein, ORF2 encodes a tyrosine recombinase (YR), and ORF3 encodes the pol gene, which comprises a RT, an RNase H (RH), and a methyltransferase (MT) domain. The internal complementary region (ICR) next to the right ITR exhibits sequences that are inverse complementary to the left and the right ITRs. A1 and A2 indicate amplicons used for qRT-PCR. P1 to P3 show the binding positions of the radioactively labeled oligonucleotides. Oligonucleotide probes (P) shown above the element are directed against sense transcripts. B, Northern blot analysis of DIRS-1 sense transcripts in deletion strains and the Ax2 wild type. Three 32P-labeled oligonucleotides (P1–P3) were used to detect sense transcripts. As a loading control, the membrane was rehybridized with a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probe directed against the actin mRNA. C, relative expression of DIRS-1 transcripts (sense and antisense) in the indicated deletion strains and the Ax2 wild type measured by qRT-PCR using two different DIRS-1 amplicons (A1 and A2) normalized to cinD mRNA. The data were plotted relative to DIRS-1 expression in Ax2 (transcript level is set to 100%). A1, n = 8. Error bars: mean with S.D.; paired t test: p = 0.0001 (***) (Ax2 wt: agnA−), p = 0.0037 (**) (Ax2: agnB−), p = 0.0010 (***) (Ax2: agnA−/agnB−). A2, n = 4 (agnA−/agnBko n = 4). Error bars: mean with S.D., paired t test: p = < 0.0001 (***) (Ax2: agnA−), p = 0.0004 (***) (Ax2: agnB−), p = 0, 0093 (**) (Ax2 wt: agnA−/agnB−). n includes (at least) two independent biological replicates. Each qPCR reaction was run in triplicate.

For better quantification we performed qRT-PCR to measure DIRS-1 transcript levels in the different mutant strains using two amplicons located at the 5′ end of ORF3 (A1) and at the 3′ end of ORF2 (A2) (Fig. 3C). The results confirmed the enrichment of DIRS-1 transcripts in the single agnA− and in the agnA−/agnB− strain and indicated a slight but significant reduction of transcripts in the single agnB− strain (see p values in legend to Fig. 3).

It should be noted that the qRT-PCR targets several of the DIRS-1 transcripts seen in the Northern blot (Fig. 3B). Because these processing and/or degradation products have different abundance we cannot determine the absolute number of full-length DIRS-1 RNAs.

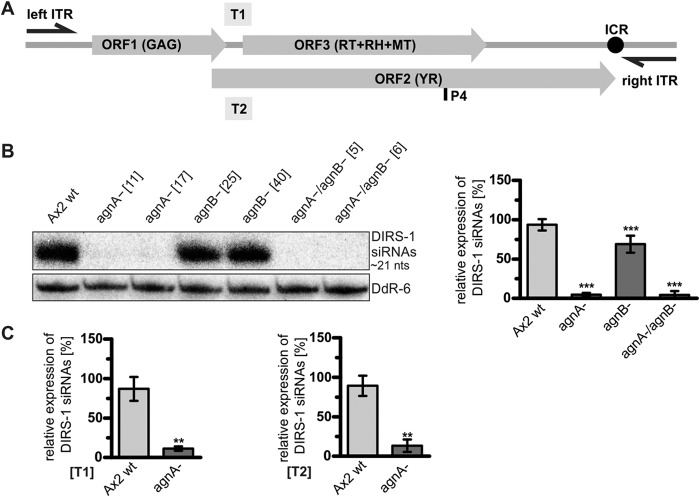

DIRS-1 derived siRNAs Are Reduced in agnA− Cells

To elucidate the role of the AgnA and AgnB in DIRS-1 regulation, we analyzed the expression of DIRS-1-derived siRNAs in the respective knock-out strains. Northern blot analysis revealed a strong, up to 90% reduction in the agnA− and in the agnA−/agnB− strains as compared with the Ax2 wild type. This was observed for sense and antisense DIRS-1 siRNAs as well as for different positions within the element (Fig. 4, A–C). The data indicated that AgnA is involved in the generation of siRNAs, and the reduced siRNA level upon agnA deletion could explain the increase of DIRS-1 mRNA shown in Fig. 3.

FIGURE 4.

DIRS-1 small RNAs do not accumulate in agnA− strains. A, positions of the radiolabeled probes used to detect DIRS-1 siRNAs. P4 is a 32P-labeled 21-nt oligonucleotide that detects a subset of DIRS-1 antisense siRNAs. T1 and T2 are strand-specific 32P-labeled riboprobes, detecting sense and antisense siRNAs in a distinct 300-bp region of the DIRS-1 element. Oligonucleotide probes (P) and riboprobes (T) shown below the element are directed against sequences in antisense orientation, and probes shown above the element are directed against sense transcripts. B, representative Northern blot of DIRS-1 antisense siRNAs detected by P4. Equal loading was verified by rehybridization of the membrane with a 32P-labeled probe directed against the snoRNA DdR-6. Numbers in brackets indicate clone numbers of independent biological replicates. Quantification of DIRS-1 siRNAs (right panel) is given relative to the DdR-6 loading control and normalized to the Ax2 wild type (=100%). n = 8. Error bars: mean with S.D., paired t test: p = < 0.0001 (***) (Ax2 wt: agnA−), p = < 0.0001 (***) (Ax2 wt: agnB−), p = < 0.0001 (***) (Ax2 wt: agnA−/agnB−). C, quantification of DIRS-1 siRNAs from Northern blots using strand-specific riboprobes T1 and T2 relative to DdR-6. Error bars: mean with S.D. T1: n = 4, paired t test: p = 0.0025 (**) (Ax2 wt: agnA−). T2: n = 4, paired t test: p = 0.0016 (**) (Ax2 wt: agnA−).

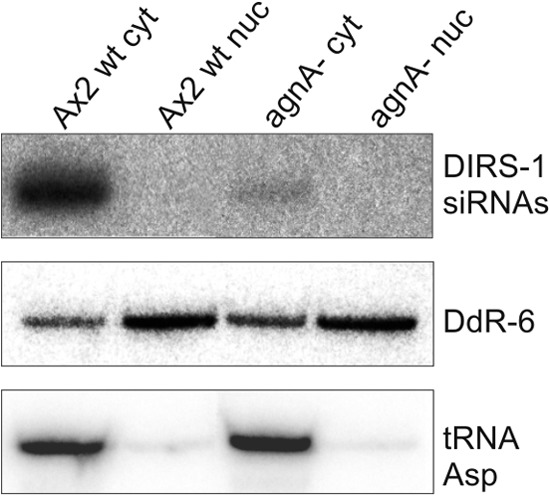

Localization of DIRS-1 siRNAs

To elucidate whether DIRS-1 siRNAs accumulate in the cytoplasm or in the nucleus, cells were fractionated, and siRNAs were analyzed in nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions. A Northern blot showed that DIRS-1 siRNAs localized predominantly in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5), suggesting a posttranscriptional mechanism of DIRS-1 silencing.

FIGURE 5.

Subcellular localization of DIRS-1 siRNAs. Fractions of cytoplasmic (cyt) and nucleoplasmic (nuc) RNA were isolated from the Ax2 wild type and the agnA− strain and analyzed by Northern blot. The membrane was probed with the 32P-labeled oligonucleotide P4 (see Fig. 3A) to detect DIRS-1 specific siRNAs in antisense orientation. The enrichment for nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA was shown by hybridization with a 32P-labeled antisense oligonucleotide against snoRNA DdR-6 and against tRNAAsp. The tRNA is almost exclusively in the cytoplasm, whereas DdR-6 is enriched in the nucleus.

Deep Sequencing of Small RNAs Confirmed Depletion of DIRS-1 siRNAs in the agnA− Strain

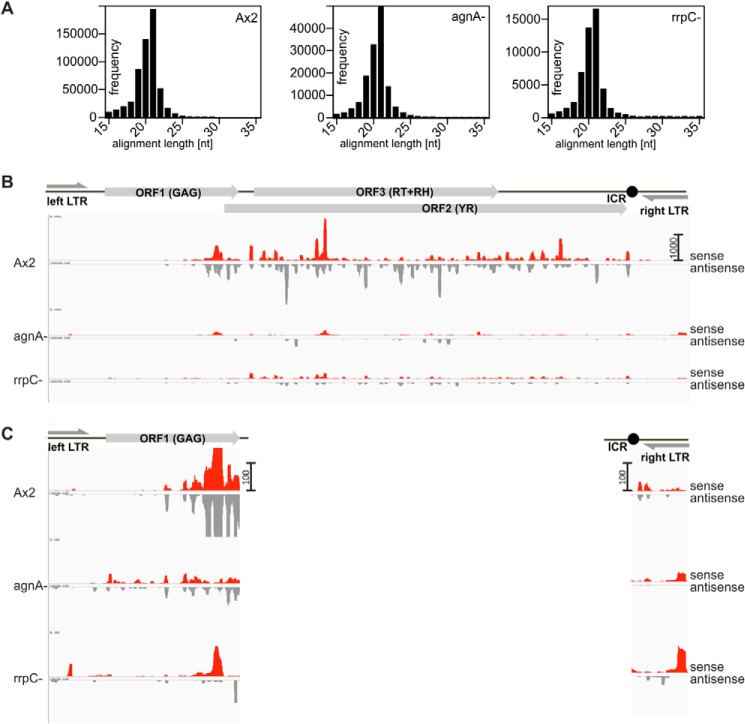

To confirm the Northern blot data and to obtain further insight into the distribution of siRNAs along the DIRS-1 element, we performed RNA-seq of size-fractionated samples from the wild type, the agnA− strain, and a rrpC− strain, which has previously been shown to display reduced levels of DIRS-1 siRNAs (21). In the agnA− strain we observed an ∼70% reduction of siRNAs along the DIRS-1 element compared with Ax2. For the rrpC− we found an ∼90% reduction (Table 2) that was in the range of the previously published data. Size-sorted reads of the small RNAs peak at 21 nt and are thus defined as siRNAs rather than random degradation products (Fig. 6A).

TABLE 2.

Reads aligned to DIRS-1

The table shows the DIRS-1 siRNAs normalized to the total number of reads. Numbers are given for the different strains used in this study.

| Strain | Ax2 | agnA- | rrpC- |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total read number | 5,222,372 | 4,719,427 | 5,747,142 |

| Number of reads aligned to DIRS-1 | 34.152 | 8.350 | 3.909 |

| Relative number of DIRS-1 aligned reads | 0.006539557 | 0.001769283 | 0.00680164 |

| Normalized reads (Ax2 is set as 1) | 1 | 0.27 | 0.10 |

FIGURE 6.

Distribution of siRNAs along the retroelement DIRS-1 in Ax2 wt, agnA−, and rrpC− strains. A, DIRS-1 mapped reads between 15 and 35 nt were sorted by size. For all strains investigated the size peak was found between 19 and 21 nt with a maximum at 21 nt. RH, RNase H; MT, methyltransferase. B, the retroelement is schematically shown in scale to the distribution panels below. Size-selected small RNAs were subjected to deep sequencing and mapped to a full-length DIRS-1 element. Sense RNAs are shown as upward red bars, and antisense RNAs are shown as downward gray bars. C, enlargements of the left ITR and ORF1 and of the right ITR are shown to visualize siRNAs that are detectable in the deletion mutants but not in the wild type. Scale bars on the y axis (right) show read counts for panel B and C.

Fig. 6B shows that siRNAs were unequally distributed along the sequence with some predominant peaks. The distribution of sense (red) and antisense (gray) siRNAs was mostly asymmetric, suggesting either different stabilities of the two strands or preferential synthesis of one strand by the RdRP. The ITR sequences and most of the gag gene (ORF1) showed almost no matching siRNAs except for a peak close to the gag 3′ end. For the agnA− strain, the pattern of siRNA distribution was very similar to the wild type except that the total number was lower, thereby confirming the results of the Northern blots. Remarkably, new siRNAs that were barely or not detectable in the wild type, appeared in the 5′ half of ORF1 and the right ITR (Fig. 6C). As previously observed by Hammann and co-workers (21), the rrpC− strain also displayed strongly reduced siRNA levels. The distribution of the residual DIRS-1 siRNAs was, however, distinct from what we found in agnA− cells. Similarly, the distribution of new siRNAs in the rrpC− strain was most pronounced in the ends of the retroelement but different from those in the agnA− strain. It should be noted that independent deep sequencing experiments are difficult to compare, but our overall results for the Ax2 and the rrpC− match the data by Hammann and co-workers (21) very well.

AgnA Is Necessary for DIRS-1 siRNA Amplification in 3′ and 5′ Direction and for Posttranscriptional Silencing

In C. elegans, fungi, and plants an amplification system based on RdRPs produces double-stranded RNAs on transcripts and thus expands the pool of siRNAs (13). This phenomenon is termed transitivity. Primed synthesis by RdRPs will proceed in the 5′ direction of a given RNA. A different mechanism of RdRP guiding by siRNAs or by proteins may also amplify siRNAs in 3′ direction (9, 15, 49).

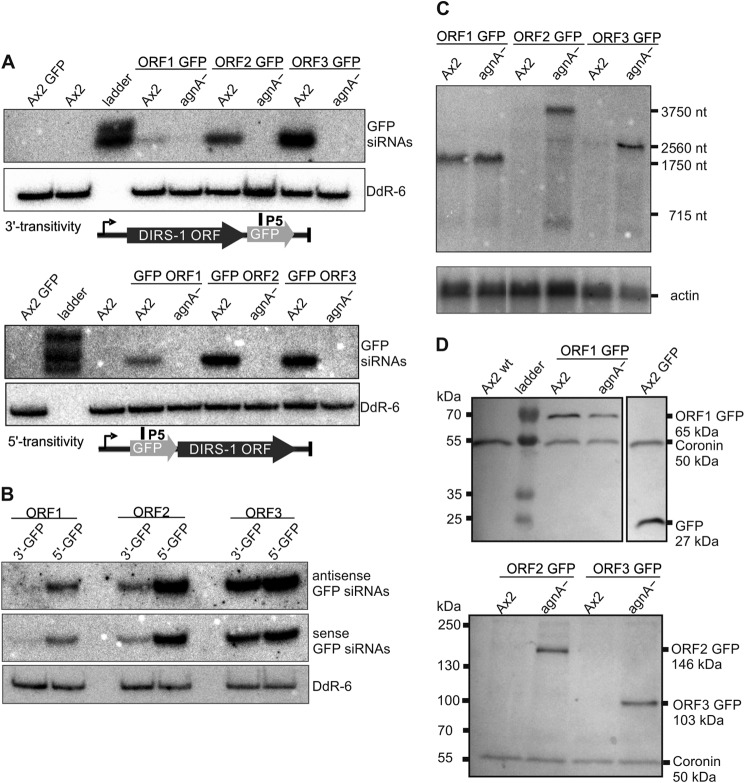

In C. elegans the Argonaute protein rde-1 has an important function in the recruitment of the amplification machinery (15). To examine if AgnA in D. discoideum acts in a similar way, we analyzed 3′ and 5′ transitivity in the knock-out strain and in the Ax2 wild type. If AgnA was important to recruit the amplification machinery one would expect no transitivity at all in the respective knock-out strain. We used a set of six extrachromosomal plasmids (37) containing one of the three DIRS-1 ORFs, each which were fused to a C-terminal and to an N-terminal GFP tag (21). The constructs were transformed into the agnA− and into the Ax2 wild type strains.

If the endogenous DIRS-1 siRNAs or any protein factor could guide an RdRP to the transgene, secondary, transitive siRNAs homologous to GFP would be expected. In fact, we detected GFP siRNAs in the Ax2 wild type with each construct (Fig. 7A) (21). Transitivity was strongest with ORF3, intermediate with ORF2, and very weak with ORF1. Effective spreading occurred in the 5′ and 3′ direction, and in both cases sense and antisense siRNAs were detected (Fig. 7, A and B). Unexpectedly, transitivity did not correlate with the amount of siRNAs found in the 3′ or 5′ parts of the different DIRS-1 ORFs (compare Fig. 6). In the agnA− strain, no GFP siRNAs were found (Fig. 7A), thus demonstrating the requirement of the protein for the spreading process.

FIGURE 7.

Transitivity in the Ax2 and in the agnA− strain. A, Northern Blots to detect GFP siRNAs generated by 3′ and 5′ transitivity. Radioactively labeled oligonucleotide P5 was used to detect GFP-derived sense siRNAs. Equal loading was verified by rehybridization of the membrane with a 32P-labeled probe directed against snoRNA DdR-6. Total RNA from the Ax2 wild type and from an Ax2 strain transformed with the extrachromosomal plasmid pDM317 containing an expressed GFP tag only were loaded as controls. B, Northern blot to detect GFP sense and antisense siRNAs generated by 3′ and 5′ transitivity in the Ax2. The radioactively labeled probes detected either sense or antisense GFP siRNAs and are complementary to each other. Equal loading was verified by rehybridization of the membrane with a 32P-labeled probe directed against snoRNA DdR-6. C, Northern blot analysis of DIRS-1 ORF-GFP fusion mRNAs. The membrane was probed with a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probe (P5). As a loading control, the membrane was rehybridized with a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probe directed against actin mRNA. D, cell lysates of different strains were analyzed by Western blot to detect the GFP fusions proteins. DIRS-1 ORF2 and ORF3 GFP accumulate in the agnA− but not in the Ax2 wild type, whereas DIRS-1 ORF1 GFP was expressed in both strains. An anti-GFP antibody was used to detect the GFP fusion proteins. To show equal loading, blots were probed for the endogenous protein Coronin with an anti-Coronin antibody.

As expected, mRNA of the ORF 2 and 3 transgenes was strongly reduced in the wild type but accumulated in the agnA− strain. No silencing effect was seen with the ORF1 transgene (Fig. 7C). The silencing effect on the mRNA level by siRNAs was further confirmed by Western blots (Fig. 7D). Although ORF1 (Gag) was equally expressed in the mutant and the wild type, ORF2 (tyrosine recombinase) and ORF3 (RT + RNase H + methyltransferase) fusion proteins were only detected in the agnA− strain. Complete silencing was observed in the wild type for the latter two even though the constructs were expressed from a strong promoter and were present in multiple copies. The agnA−/B− strain behaved exactly like the agnA− strain, whereas the single agnB− strain showed DIRS protein expression like the Ax2 wild-type strain (data not shown). In addition to AgnA-mediated spreading, the experiment indicates that endogenous siRNAs can target a transgene in trans on the mRNA level.

Extrachromosomal DIRS-1 cDNA Is Accumulated in the agnA− and Reduced in the agnA−/agnB− Strains

Assuming that DIRS-1 deregulation may be sufficient for mobilization of the retroelement, we performed restriction analysis followed by Southern hybridization to detect new DIRS-1 integrations. We did not find any indication of new inserts but rather unexpectedly found additional identical hybridizing fragments in several independent strains (data not shown).

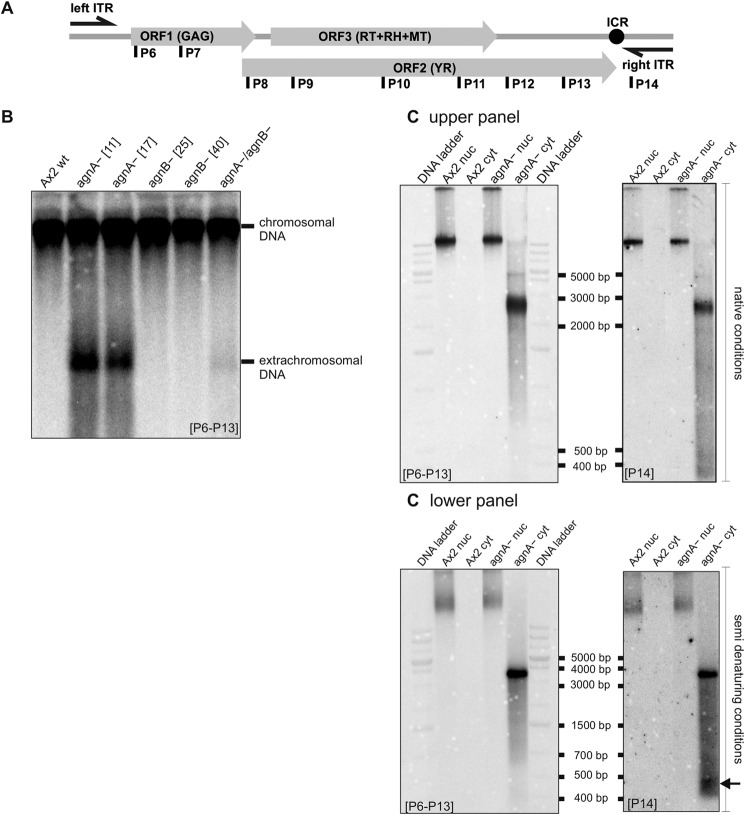

We then hybridized undigested DNA from the different mutants and the Ax2 and detected two hybridization signals, one corresponding to the genomic high molecular weight DNA and one of an apparent molecular weight of 2.8–4 kb that was strong in agnA− cells, much less intense in the agnA−/agnB− strain, and not visible in the wild type and in agnB− cells (Fig. 8, A and B). Because both Argonaute proteins are developmentally regulated, we examined if changes in accumulation of new extrachromosomal DIRS-1 DNA could be observed at high expression of agnB in development (8 h). But DIRS-1 extrachromosomal DNA levels did not change either in the agnA− or the agnA/B− strains (data not shown).

FIGURE 8.

DIRS-1 extrachromosomal DNA accumulates in agnA− strains. A, positions of 32P-labeled oligonucleotides used for detection of extrachromosomal cDNA are shown in the schematic graph of DIRS-1. Either a mixture of oligonucleotides as indicated or P14 alone (binding to the right ITR) was used. Oligonucleotide probes (P) shown below the element are directed against antisense sequences of the DIRS-1 mRNA. RH, RNase H; MT, methyltransferase. B, DNA was isolated with the GeneJET Genomic DNA Purification kit (Thermo Scientific). The gel with undigested DNA was run under native conditions. The Southern blot was hybridized with probes P6–P13 that detect DIRS-1 copies in the chromosome as well as extrachromosomal DIRS-1 cDNA. Extrachromosomal cDNA that corresponds to the minus strand of the transposon is found in the agnA− strains and is barely detectable in the agnA−/agnB− strain. C, DNA was isolated from the cytoplasm and from the nucleoplasm. Southern Blots were performed under native (upper panel) and under semi-denaturing (lower panel) conditions. The apparent molecular weight of the dominant extrachromosomal DIRS-1 DNA in the cytoplasmic fraction depended on running conditions and varied between 2800 and 4500 nt. P6 to P13 were used as probes in the left panels. The same blots were stripped and hybridized with P14 (right panels). Below the dominant almost full-length extrachromosomal DIRS-1 cDNA, shorter fragments of 400 to 500 nt became detectable.

As determined by strand-specific probes, the extrachromosomal DNA was single-stranded and corresponded to the almost complete antisense strand of the retrotransposon (Fig. 8B and data not shown). The extrachromosomal property of the additional DIRS-1 DNA was further supported by the fact that it could be readily isolated by a kit designed for plasmid purification (data not shown).

Cell fractionation demonstrated that the extrachromosomal DNA was accumulated or exclusively present in the cytoplasm (Fig. 8C). Especially under denaturing conditions we detected an additional smear or group of predominant bands migrating at ∼500 nt (Fig. 8C). Using various radiolabeled probes, the smaller bands were found to contain sequences of the right ITR (Fig. 8, A and C, lower panel). We do not know how the smaller molecules associate or hybridize to the long single-stranded DNA. Variations in the apparent molecular weight of the large and the small extrachromosomal DNA fragments are probably due to secondary structures, which are more or less resolved depending on subtle changes in running conditions and treatment of the DNA sample. The DNA ladder only serves as a crude ruler, not as a precise measure of molecular weight.

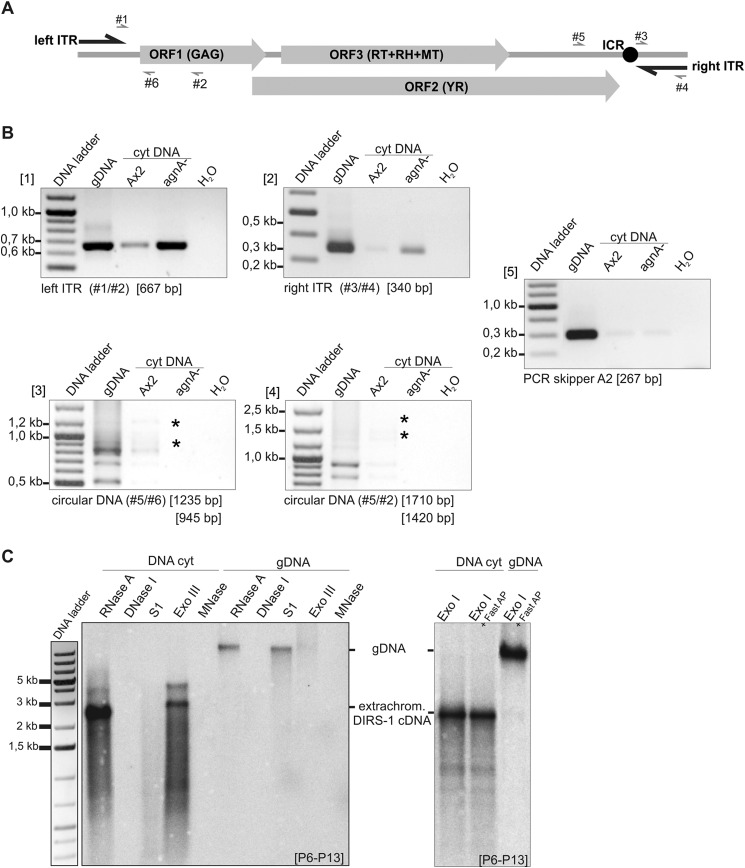

To further characterize the composition of the extrachromosomal DIRS-1 DNA, PCR analysis and digestions with different nucleases were performed (Fig. 9). Amplicons covering the predicted transcription start in the left LTR as well as the complete right LTR could generate PCR products (Fig. 9, A and B). However, oligonucleotides located in the left LTR upstream of the transcription start did not give any PCR products (data not shown). Thus, the extrachromosomal cDNA covers the complete DIRS-1 element except for the left LTR sequences upstream of the predicted transcription start site. PCR reactions across the junction of the left and the right LTR that would indicate a circular DIRS-1 extrachromosomal DNA, failed (Fig. 9B).

FIGURE 9.

Composition of extrachromosomal DIRS-1 DNA. A, DIRS-1 element and binding positions of primers used for PCR analysis of extrachromosomal DIRS-1 cDNA. Forward primers are shown above the element, whereas reverse primers are shown below the element, respectively. Primer combinations used for PCR analysis and the size of expected fragments are given below the figures in B. RH, RNase H; MT, methyltransferase. B, PCRs to analyze extrachromosomal DIRS-1 cDNA. PCRs were performed on DNA isolated from the cytoplasmic (cyt) fraction of Ax2 and the agnA− strain. As a control, all PCRs were performed on genomic DNA (gDNA) as template. PCRs were performed with 28 cycles (1). PCR was carried out to analyze the presence of the left LTR. The forward primer (#1) starts at the predicted DIRS-1 transcription start. Another forward primer that binds 20 nucleotides upstream in the left LTR gave no PCR product (2). PCR was carried out to analyze the presence of the right LTR. Cytoplasmic DNA from the agnA− strain but not from the Ax2 wild type gave a PCR signal indicating that the complete right LTR is part of the extrachromosomal cDNA (3 and 4). PCRs were carried out to test for circularized extrachromosomal cDNA (with or without complete left LTR). No signals of the expected sizes (indicated by a star) were detectable for the cytoplasmic DNA fraction of agnA−. PCR products on genomic DNA are most likely derived from incomplete fragments in the DIRS-1 clusters (5). Control PCR on the skipper retrotransposon is shown. Weak signals indicate low levels of contaminating chromosomal DNA in the cytoplasmic fractions. C, left panel, cytoplasmic DNA (left) and nuclear DNA (right) from the agnA− strain was digested with RNase A alone or in the addition with DNase I, S1 nuclease (S1), exonuclease III (ExoIII), and micrococcal nuclease (MNase). DNase I and MNase are endonucleases that cleave single and double-stranded DNA. S1 nuclease is an endonuclease that is specific for single-stranded DNA. Exonuclease III only cleaves double-stranded DNA. Right panel, cytoplasmic and genomic DNA from the agnA− strain was digested with Exonuclease I (ExoI). which degrades single-stranded DNA in the 3′-5′ direction. Both panels, Southern blots were performed under native conditions. Extrachromosomal DIRS-1 DNA was detected by probes P6 to P13 (see Fig. 8A).

Using various nucleases, the extrachromosomal DNA was further confirmed to be single-stranded (Fig. 9C, left panel). In particular, the single strand-specific nuclease S1 digested the extrachromosomal DNA but not the nuclear DNA, whereas the double strand-specific nuclease exonuclease III digested the chromosomal DNA but not the cytoplasmic copies. Unexpectedly, exonuclease I, which degrades single-stranded DNA in 3′ to 5′ direction, did not digest the extrachromosomal DNA (Fig. 9C, right panel). Although this may argue for a circular molecule, we rather assume that unusual secondary structures or modifications prevented the attack of the enzyme on the 3′ end of a linear cDNA.

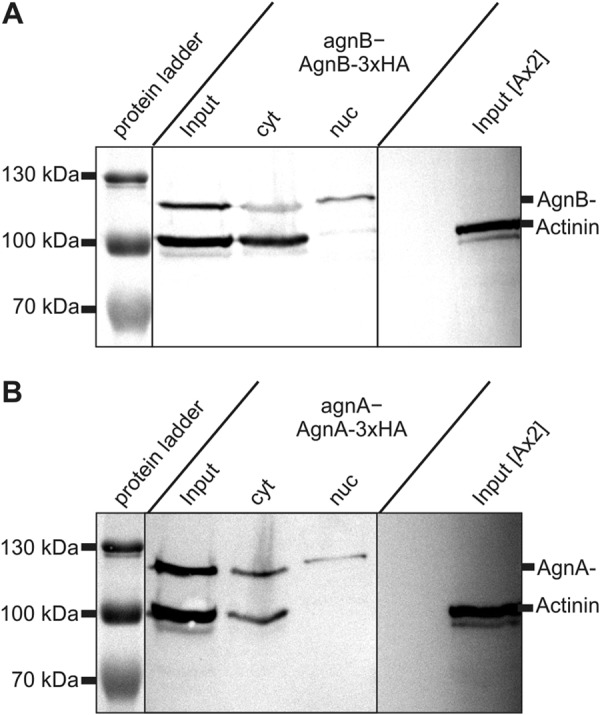

AgnA and AgnB Are Present in the Cytoplasm as Well as in the Nucleus

The observation that DIRS-1 extrachromosomal DNA accumulated to a lesser extent in strains where agnA and agnB were disrupted (compared with the single agnA− strain, Fig. 8B) was in agreement with the assumption that AgnB somehow promotes expression or amplification of the DIRS-1 retrotransposon. A direct effect of AgnB in DIRS-1 transcription or cDNA synthesis is feasible because the protein is localized in the nucleus as well as in the cytoplasm (Fig. 10).

FIGURE 10.

Subcellular localization of AgnA-3xHA and AgnB-3xHA fusion proteins. Protein was prepared from total cells (input) and from fractionated cytoplasm (cyt) and nuclei (nuc). Sources were agnB− cells overexpressing AgnB-3xHA and agnA−cells overexpressing AgnA-3xHA. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted. HA-tagged proteins were detected with a specific antibody. Cell equivalents were loaded, and fractions were not normalized for total protein content. As a cytoplasmic marker, α-actinin was used. The blot indicates that both tagged proteins can be detected in the cytoplasm as well as in the nucleus.

DISCUSSION

We have analyzed the role of the two Argonaute proteins AgnA and AgnB in regulation of siRNA-mediated transposon silencing in D. discoideum. AgnA and AgnB are the most closely related (66.9% consensus positions) Argonautes among the five family members, and both are present in the cytoplasm and in the nucleoplasm. The strongest expression of agnA mRNA was found in vegetative cells, whereas expression of agnB peaks at 4 h in development. Differences to the previously published data could be due to (a) strain differences, (b) differences in the method (deep sequencing versus qRT-PCR), or (c) growth conditions (bacterial lawn versus axenic media) (Fig. 1). Although at the first glance a knock-out of agnB had no obvious effect on regulation of the DIRS-1 retroelement, a knock-out of agnA showed a strong reduction of DIRS-1-derived siRNAs and, consistently, a moderate accumulation of transposon transcripts. Using the DIRS-1-derived ORFs as transgenes (see below), we have shown that the silencing mechanism works in trans and that the DIRS-1-encoded proteins RT and tyrosine recombinase are not detectable in the wild type but are detectable in the agnA− strain. Furthermore, we could detect extrachromosomal single-stranded DIRS-1 DNA in the cytoplasm of the knock-out strain. AgnA thus plays an essential role in transposon silencing, probably by the generation of secondary siRNAs and ultimately by inhibition of RT and tyrosine recombinase expression.

Distribution of Endogenous DIRS-1 siRNAs in the Wild Type and in Different Mutants

Analysis of the DIRS-1-derived siRNAs by deep sequencing revealed that the small RNAs are unevenly distributed along the retroelement and that only very few siRNAs match the ITRs and the 5′ half of ORF1. The distribution of sense and antisense siRNAs is asymmetric, suggesting either differential stability of both strands or asymmetric synthesis of secondary siRNAs by RdRPs. This agrees with a previous observation by Wiegand et al. (21).

Similar to the rrpC− strain, siRNAs were not completely lost in the agnA− strain. The pattern of residual siRNA distribution was more similar to the wild type in the agnA− than in the rrpC−, but it appears that the antisense siRNAs are overall more reduced. For both mutants some new siRNAs that were not detected in the wild type appeared in the ITRs and the 5′ half of ORF1. Again, the distribution pattern differed between the two mutants, suggesting that siRNAs have different origins and that the two proteins contribute to partially different pathways of siRNA generation. Our hypothesis is that AgnA is involved in the synthesis of secondary siRNAs by recruiting RdRPs to DIRS-1 transcripts, which would allow for 3′ and 5′ transitivity. Good experimental evidence for a similar model exists in C. elegans. There, transitivity occurs in a 3′ and in a 5′ direction, and a lack of the Argonaute protein rde-1 results in the loss of secondary siRNAs (15, 50).

Is AgnA Involved in Secondary siRNA Synthesis?

To substantiate AgnA involvement in secondary siRNA synthesis, we designed an experiment to shed light on the question if endogenous siRNAs can act in trans on transgenic DIRS-1 gene fusions. This was obviously the case as ORF2 and ORF3 transcripts were barely detectable in the wild type but clearly accumulated in the agnA− strain. Secondary siRNAs can be unambiguously identified by spreading or transitivity into adjacent regions (12). In fact, we detected siRNAs matching the GFP gene, which was fused to the C terminus and the N terminus of the ORFs. Surprisingly theses siRNAs were found in sense and antisense orientation, thus excluding a simple copying mechanism by RdRP from the mRNA. This is different to C. elegans where secondary siRNAs are only of antisense polarity with respect to the original trigger (15, 50). There is so far no precedence for this observation, and the current model of 3′ spreading has to be adjusted. Silencing of the fusion genes was even more obvious on the protein level than on the RNA level. Consistent with the hypothesis that AgnA was involved in secondary siRNA generation, no GFP-derived siRNAs and no transgene silencing were observed in the agnA− strain. However, we cannot clearly distinguish if this was due to the overall reduction of siRNAs in the mutant or to its inability to recruit the amplification machinery. One may assume that the strength of transitivity depended on the amount of endogenous siRNAs at the ends of the ORFs as these siRNAs could guide an RdRP close to the fusion point and generate secondary siRNAs of the 3′ and 5′ tag. But there was no correlation between transitivity and the number of 3′ or 5′ siRNAs. Remarkably, ORF1 GFP showed essentially no transitivity even though there was a substantial amount of siRNAs close to the 3′ end. These findings and the fact that we could not see any transitivity in the agnA− strain even though 30% of DIRS-1 siRNAs were still present suggested that AgnA recruits RrpC for siRNA amplification and that the residual siRNAs are not sufficient. Based on the transgene experiments, one could assume that the ORF1-encoded Gag protein is also expressed in wild type cells but insufficient to assemble functional virus like particles in which reverse transcription is thought to take place (30). Gag may either be insufficient to form virus-like particles or, even if virus-like particles were formed, no RT is expressed in wt cells to promote reverse transcription.

Is DIRS-1 on the Way to Transpose?

Expression of the reverse transcriptase and the tyrosine recombinase was strongly enhanced in the agnA− strain (Fig. 6D). Even though this could only be shown with the respective transgenes, we believe that the endogenous RT and tyrosine recombinase proteins are also up-regulated in the mutant. With the disruption of agnA, proliferation of the retroelement proceeds further than in the wild type. However, we could not show enhanced transposition in the mutant. The accumulated single-stranded DNA in the cytoplasm is most likely a product of the DIRS-1-encoded reverse transcriptase and an intermediate on the way to transposition, but there appears to be another safeguard mechanism that prevents completion of this pathway.

According to hybridization and PCR analysis with different oligonucleotides, this long DNA is not complete but is only an almost full-length product. It does not contain the left ITR up to the previously suggested transcription start site at approximately nucleotide 300. The cDNA thus covers only ∼4500 nt of the 4800 nt. These cytoplasmic molecules have not been observed before in D. discoideum. Notably, a second, less distinct DNA family of apparent 500 nt is associated with the almost full-length cDNA. The origin of these molecules is unknown; they could be abortive reverse transcripts or processing products. Southern blot experiments showed that they harbor sequences of the right LTR and were also single-stranded. Because no sequence complementarity between the small and the long cDNAs is obvious; protein-aided association of partially complementary regions may be possible to support the generation of dsDNA of a complete DIRS-1 element. The theoretical model for the amplification of the DIRS-1 retroelement proposed by Cappello et al. (31) does not include such short molecules. Poulter and Goodwin (32) proposed a model where a second, possibly smaller DNA serves as an annealing platform for reconstruction of the complete element and for synthesis of dsDNA. However this model is only suggested for retroelements with direct repeats.

Accumulation of DIRS-1 cDNA in the agnA− strain may be due to two interrelated reasons; DIRS-1-derived full-length RNA and processing or degradation products accumulated 4–8-fold in the agnA− strain compared with the wild type, and relative accumulation levels depended on the position of the amplicon that was used for qRT-PCR. This rather moderate increase in transcripts was by far surpassed by the accumulation of the single-stranded cDNA molecule in the agnA− mutant. A more dramatic effect was also seen on protein expression in the transitivity approach (Fig. 7) where ORF 2 and ORF 3 proteins were only detectable in the agnA− strain, whereas the ORF 1 protein was well translated in the wild type. In the end it is most likely the expression of the DIRS-1 proteins that mediates the accumulation of DIRS-1 cDNA. In the wild type, protein expression is inhibited or reduced by low levels of mRNA due to high levels of secondary siRNAs. However, we cannot exclude that siRNAs have an additional effect on translation.

The Role of AgnB in DIRS-1 Regulation

The single agnB disruption had only minor effects on DIRS-1 regulation. Upon closer inspection, a reduction in DIRS-1 transcripts and DIRS-1-derived siRNAs was observed, but these effects were relatively mild. DIRS-1 transcripts were reduced in comparison to the single agnA− strain but still significantly higher than in the wild type. However, there was a strong effect in the double mutant where the accumulation of extrachromosomal DNA was almost abolished. AgnB thus has an apparently positive effect on the retroelement, or it prevents further productive processing of the cDNA on the way to transposition. For retroviruses it has been shown that Argonaute proteins promote their amplification: human Ago2 may facilitate the assembly of retroviral particles, but detailed mechanisms are not well understood (51).

Both Argonaute proteins that we analyzed have substantial effects on silencing of the retroelement DIRS-1 and appear to function on different levels. AgnA has a more canonical role in the generation of siRNAs, probably in the cytoplasm where most of DIRS-1 siRNAs are present. AgnB, however, is to our knowledge the first Argonaute with an apparently positive effect on a retroelement.

Further investigations are required to unravel the role of AgnB in regulation. Similarly, the exact composition of the extrachromosomal single-stranded DNA that is accumulated in the agnA− strain requires further analysis. Because we did not observe a substantial mobilization of the retroelement, it will be of interest to elucidate the additional safeguard mechanism(s) that inhibits full activation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Thomas Winckler, Fredrik Soederbom, and Stephan Wiegand for discussion and suggestions. Markus Maniak generously supplied antibodies against GFP, Coronin, and α-actinin.

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grants NE285/10-1 (to W. N.) and HA3459/7 (to C. H.).

F. Soederbom and T. Winckler, personal communication.

- RdRP

- RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

- LTR

- long terminal repeat

- nt

- nucleotides

- qRT

- quantitative reverse transcription

- snoRNA

- small nucleolar RNA

- rcf

- relative centrifugal force

- ITR

- inverted terminal repeat.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ghildiyal M., Zamore P. D. (2009) Small silencing RNAs: an expanding universe. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 94–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mello C. C., Conte D., Jr. (2004) Revealing the world of RNA interference. Nature 431, 338–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carthew R. W., Sontheimer E. J. (2009) Origins and Mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell 136, 642–655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meister G. (2013) Argonaute proteins: functional insights and emerging roles. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 447–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Orban T. I., Izaurralde E. (2005) Decay of mRNAs targeted by RISC requires XRN1, the Ski complex, and the exosome. RNA 11, 459–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zheng X., Zhu J., Kapoor A., Zhu J. K. (2007) Role of Arabidopsis AGO6 in siRNA accumulation, DNA methylation and transcriptional gene silencing. EMBO J. 26, 1691–1701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zilberman D., Cao X., Jacobsen S. E. (2003) ARGONAUTE4 control of locus-specific siRNA accumulation and DNA and histone methylation. Science 299, 716–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Luo Z., Chen Z. (2007) Improperly terminated, unpolyadenylated mRNA of sense transgenes is targeted by RDR6-mediated RNA silencing in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19, 943–958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Voinnet O. (2008) Use, tolerance and avoidance of amplified RNA silencing by plants. Trends Plant Sci. 13, 317–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang X. B., Wu Q., Ito T., Cillo F., Li W. X., Chen X., Yu J. L., Ding S. W. (2010) RNAi-mediated viral immunity requires amplification of virus-derived siRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 484–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pak J., Fire A. (2007) Distinct populations of primary and secondary effectors during RNAi in C. elegans. Science 315, 241–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sijen T., Steiner F. A., Thijssen K. L., Plasterk R. H. (2007) Secondary siRNAs result from unprimed RNA synthesis and form a distinct class. Science 315, 244–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maida Y., Masutomi K. (2011) RNA-dependent RNA polymerases in RNA silencing. Biol. Chem. 392, 299–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yigit E., Batista P. J., Bei Y., Pang K. M., Chen C. C., Tolia N. H., Joshua-Tor L., Mitani S., Simard M. J., Mello C. C. (2006) Analysis of the C. elegans Argonaute family reveals that distinct Argonautes act sequentially during RNAi. Cell 127, 747–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pak J., Maniar J. M., Mello C. C., Fire A. (2012) Protection from feed-forward amplification in an amplified RNAi mechanism. Cell 151, 885–899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Parrish S., Fire A. (2001) Distinct roles for RDE-1 and RDE-4 during RNA interference in Caenorhabditis elegans. RNA 7, 1397–1402 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eichinger L., Pachebat J. A., Glöckner G., Rajandream M. A., Sucgang R., Berriman M., Song J., Olsen R., Szafranski K., Xu Q., Tunggal B., Kummerfeld S., Madera M., Konfortov B. A., Rivero F., Bankier A. T., Lehmann R., Hamlin N., Davies R., Gaudet P., Fey P., Pilcher K., Chen G., Saunders D., Sodergren E., Davis P., Kerhornou A., Nie X., Hall N., Anjard C., Hemphill L., Bason N., Farbrother P., Desany B., Just E., Morio T., Rost R., Churcher C., Cooper J., Haydock S., van Driessche N., Cronin A., Goodhead I., Muzny D., Mourier T., Pain A., Lu M., Harper D., Lindsay R., Hauser H., James K., Quiles M., Madan Babu M., Saito T., Buchrieser C., Wardroper A., Felder M., Thangavelu M., Johnson D., Knights A., Loulseged H., Mungall K., Oliver K., Price C., Quail M. A., Urushihara H., Hernandez J., Rabbinowitsch E., Steffen D., Sanders M., Ma J., Kohara Y., Sharp S., Simmonds M., Spiegler S., Tivey A., Sugano S., White B., Walker D., Woodward J., Winckler T., Tanaka Y., Shaulsky G., Schleicher M., Weinstock G., Rosenthal A., Cox E. C., Chisholm R. L., Gibbs R., Loomis W. F., Platzer M., Kay R. R., Williams J., Dear P. H., Noegel A. A., Barrell B., Kuspa A. (2005) The genome of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature 435, 43–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kessin R. H. (2001) Dictyostelium: Evolution, Cell Biology, and the Development of Multicellularity, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK [Google Scholar]

- 19. Martens H., Novotny J., Oberstrass J., Steck T. L., Postlethwait P., Nellen W. (2002) RNAi in Dictyostelium: the role of RNA-directed RNA polymerases and double-stranded RNase. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 445–453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cerutti H., Casas-Mollano J. A. (2006) On the origin and functions of RNA-mediated silencing: from protists to man. Curr. Genet. 50, 81–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wiegand S., Meier D., Seehafer C., Malicki M., Hofmann P., Schmith A., Winckler T., Földesi B., Boesler B., Nellen W., Reimegård J., Käller M., Hällman J., Emanuelsson O., Avesson L., Söderbom F., Hammann C. (2014) The Dictyostelium discoideum RNA-dependent RNA polymerase RrpC silences the centromeric retrotransposon DIRS-1 post-transcriptionally and is required for the spreading of RNA silencing signals. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 3330–3345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rot G., Parikh A., Curk T., Kuspa A., Shaulsky G., Zupan B. (2009) dictyExpress: a Dictyostelium discoideum gene expression database with an explorative data analysis web-based interface. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hinas A., Reimegård J., Wagner E. G., Nellen W., Ambros V. R., Söderbom F. (2007) The small RNA repertoire of Dictyostelium discoideum and its regulation by components of the RNAi pathway. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 6714–6726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rosen E., Sivertsen A., Firtel R. A. (1983) An unusual transposon encoding heat shock inducible and developmentally regulated transcripts in Dictyostelium. Cell 35, 243–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Glöckner G., Szafranski K., Winckler T., Dingermann T., Quail M. A., Cox E., Eichinger L., Noegel A. A., Rosenthal A. (2001) The complex repeats of Dictyostelium discoideum. Genome Res. 11, 585–594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zuker C., Cappello J., Chisholm R. L., Lodish H. F. (1983) A repetitive Dictyostelium gene family that is induced during differentiation and by heat shock. Cell 34, 997–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chung S., Zuker C., Lodish H. F. (1983) A repetitive and apparently transposable DNA sequence in Dictyostelium discoideum associated with developmentally regulated RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 11, 4835–4852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Piednoël M., Gonçalves I. R., Higuet D., Bonnivard E. (2011) Eukaryote DIRS1-like retrotransposons: an overview. BMC Genomics 12, 621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dubin M., Fuchs J., Gräf R., Schubert I., Nellen W. (2010) Dynamics of a novel centromeric histone variant CenH3 reveals the evolutionary ancestral timing of centromere biogenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 7526–7537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Havecker E. R., Gao X., Voytas D. F. (2004) The diversity of LTR retrotransposons. Genome Biol. 5, 225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cappello J., Handelsman K., Lodish H. F. (1985) Sequence of Dictyostelium DIRS-1: an apparent retrotransposon with inverted terminal repeats and an internal circle junction sequence. Cell 43, 105–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Poulter R. T., Goodwin T. J. (2005) DIRS-1 and the other tyrosine recombinase retrotransposons. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 110, 575–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cohen S. M., Cappello J., Lodish H. F. (1984) Transcription of Dictyostelium discoideum transposable element DIRS-1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4, 2332–2340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gaudet P., Pilcher K. E., Fey P., Chisholm R. L. (2007) Transformation of Dictyostelium discoideum with plasmid DNA. Nat. Protoc. 2, 1317–1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sutoh K. (1993) A transformation vector for Dictyostelium discoideum with a new selectable marker bsr. Plasmid 30, 150–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Faix J., Kreppel L., Shaulsky G., Schleicher M., Kimmel A. R. (2004) A rapid and efficient method to generate multiple gene disruptions in Dictyostelium discoideum using a single selectable marker and the Cre-loxP system. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, e143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Veltman D. M., Akar G., Bosgraaf L., Van Haastert P. J. (2009) A new set of small, extrachromosomal expression vectors for Dictyostelium discoideum. Plasmid 61, 110–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Müller S., Windhof I. M., Maximov V., Jurkowski T., Jeltsch A., Förstner K. U., Sharma C. M., Gräf R., Nellen W. (2013) Target recognition, RNA methylation activity and transcriptional regulation of the Dictyostelium discoideum Dnmt2-homologue (DnmA). Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 8615–8627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pall G. S., Hamilton A. J. (2008) Improved northern blot method for enhanced detection of small RNA. Nat. Protoc. 3, 1077–1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Church G. M., Gilbert W. (1984) Genomic sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 81, 1991–1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Feinberg A. P., Vogelstein B. (1983) A technique for radiolabeling DNA restriction endonuclease fragments to high specific activity. Anal. Biochem. 132, 6–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hoffmann S., Otto C., Kurtz S., Sharma C. M., Khaitovich P., Vogel J., Stadler P. F., Hackermüller J. (2009) Fast mapping of short sequences with mismatches, insertions and deletions using index structures. PLoS Comput. Biol. 5, e1000502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Edgar R., Domrachev M., Lash A. E. (2002) Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 207–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pfaffl M. W. (2001) A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kuhlmann M., Borisova B. E., Kaller M., Larsson P., Stach D., Na J., Eichinger L., Lyko F., Ambros V., Söderbom F., Hammann C., Nellen W. (2005) Silencing of retrotransposons in Dictyostelium by DNA methylation and RNAi. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 6405–6417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Laemmli U. K. (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. de Hostos E. L., Bradtke B., Lottspeich F., Guggenheim R., Gerisch G. (1991) Coronin, an actin binding protein of Dictyostelium discoideum localized to cell surface projections, has sequence similarities to G protein β subunits. EMBO J. 10, 4097–4104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wallraff E., Schleicher M., Modersitzki M., Rieger D., Isenberg G., Gerisch G. (1986) Selection of Dictyostelium mutants defective in cytoskeletal proteins: use of an antibody that binds to the ends of α-actinin rods. EMBO J. 5, 61–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Moissiard G., Parizotto E. A., Himber C., Voinnet O. (2007) Transitivity in Arabidopsis can be primed, requires the redundant action of the antiviral Dicer-like 4 and Dicer-like 2, and is compromised by viral-encoded suppressor proteins. Rna 13, 1268–1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sijen T., Fleenor J., Simmer F., Thijssen K. L., Parrish S., Timmons L., Plasterk R. H., Fire A. (2001) On the role of RNA amplification in dsRNA-triggered gene silencing. Cell 107, 465–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bouttier M., Saumet A., Peter M., Courgnaud V., Schmidt U., Cazevieille C., Bertrand E., Lecellier C. H. (2012) Retroviral GAG proteins recruit AGO2 on viral RNAs without affecting RNA accumulation and translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 775–786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]