Abstract

Gold nanoparticle (AuNP) based colorimetric aptasensor have been developed for many analytes recently largely because of the ease of detection, high sensitivity, and potential for high-throughput analysis. Most of the target aptamers for detection have short sequences. However, the approach shows poor performance in terms of detection sensitivity for most of the long-sequence aptamers. To address this problem, for the first time, we split the 76 mer aptamer of 17β-estradiol into two short pieces to improve the AuNP based colorimetric sensitivity. Our results showed that the split P1 + P2 still retained the original 76 mer aptamer's affinity and specificity but increased the detection limit by 10-fold, demonstrating that as low as 0.1 ng/mL 17β-estradiol could be detected. The increased sensitivity may be caused by lower aptamer adsorption concentration and a lower affinity to the AuNPs of a short single-strand DNA (ssDNA) sequence. Our study provided a new way to use long-sequence aptamers to develop a highly sensitive AuNP-based colorimetric aptasensor.

Aptamers have received extensive attention in analytical and diagnostic applications as an excellent example of an affinity molecule, which can bind tightly to a broad range of targets from small metal ions to whole cells1,2,3. Compared with conventional antibodies, nucleic acid based aptamer probes have a number of advantages such as avoidance of using animals' productions, better thermostability, and more flexibility in designing various types of electrochemical4,5, fluorescence6,7, chemiluminescence8, or colorimetric9,10 sensing schemes for a broad spectrum of targets. Among the approaches, unmodified gold nanoparticle (AuNP) based colorimetric aptasensors have been given prominent attention largely because of the simplicity, high sensitivity, and a potential for high-throughput analysis11,12,13. In these assays, AuNPs are used as an extremely sensitive colorimetric indicator due to an extraordinarily high extinction coefficient and strong distance-dependent optical properties14,15. Random coil single-strand DNA (ssDNA) aptamers are postulated to be adsorbed onto the surface of AuNPs through coordination between Au and N atoms in DNA bases16,17,18,19,20. Then, the AuNPs are stabilized by ssDNA aptamers against aggregation upon salt addition and the solution remains wine-colored. However, in the presence of targets, the aptamers become folded by binding to the targets and being desorbed from the surface of the AuNPs, resulting in subsequent aggregation of AuNPs and the solution's color change from red to purple-blue. In fact, the folded aptamers or double-strand DNAs are not easily adsorbed onto the AuNPs mainly due to the higher rigidity in the structures with the hidden status of the positively charged bases positioned inside the double-stranded.

Even though the simple colorimetric aptasensor has been developed for various target molecules16,17,21,22,23,24,25, most of the target aptamers have short sequences such as potassium ions 21 mer16, thrombin 29 mer17, ochratoxin A 36 mer21, ampicillin 19 mer22, and sulfadimethoxine 22 mer23. Most of long-sequence aptamers showed poor performance in detection sensitivity as we tested aptamers such as 17β-estradiol 76 mer26, chloramphenicol 80 mer27, and oxytetracycline 76 mer28. A lower affinity to targets may be one reason as Kim et al. has significantly increased the sensitivity by truncating the 76 mer oxytetracycline aptamer to shortened 8 mer ssDNAs with an enhanced affinity28. There may be some other reasons since the mechanism of DNA adsorption onto the surface of AuNPs is still not well understood29,30. One possible reason is that short ssDNAs are more easily adsorbed onto the surface of AuNPs than long ssDNAs, which have more folded structures. That means more long aptamers are needed to stabilize AuNPs against the same concentration of salt than short aptamers. As we know, excessive aptamers mean less sensitivity in the aspect of competitive interaction dynamics among aptamers, AuNPs, and targets23. Another possible reason is that once the aptamers are adsorbed onto the surface of AuNPs, the long aptamers bind more tightly than short aptamers as they have more bases binding to the surface of AuNPs. A higher aptamer affinity to AuNPs indicates more targets are needed to detach aptamers from the surface of AuNPs, which also means lower sensitivity31.

Since many long-sequence aptamers have been selected by SELEX and it is difficult to find a short core sequence with a higher affinity, to find a new way is critical to develop a highly sensitive unmodified AuNP based colorimetric aptasensor with long-sequence aptamers. 17β-estradiol, as an endocrine disrupting chemical (EDC), has the greatest estrogenic activity and has been found frequently in natural water sources and in wastewater effluents within the range of 0.2 to 3 mg/L32. 17β-estradiol entering into the organism from outside interferes with normal physiological processes and creates many deleterious effects33. The detection of such chemicals, therefore, is necessary for protecting public and environmental health.

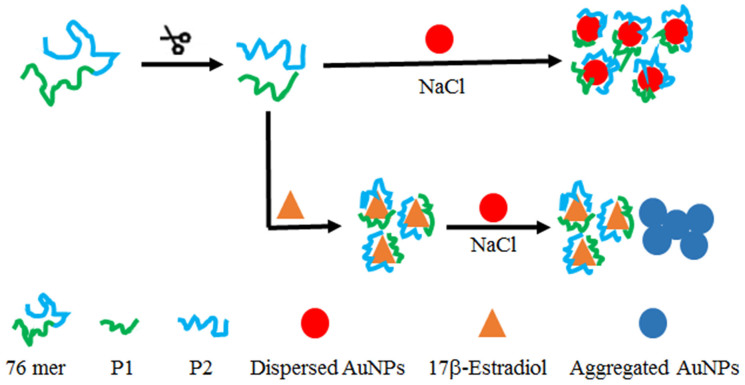

To address this problem, for the first time, we focused on 17β-estradiol with its 76 mer aptamer split into two short pieces to improve the AuNP based colorimetric sensitivity. As shown in Figure 1, the long-sequence 17β-estradiol aptamer was splitted into two fragments, which could be easily adsorbed on the surface of AuNPs and enhanced the stability of AuNPs against salt-induced aggregation. In the presence of 17β-estradiol, the split P1 and P2 binding to the target resulted in obvious AuNP aggregation upon adding a high concentration of salt and color change from red to purple or blue.

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of a gold nanoparticle based colorimetric aptasensor to detect 17β-estradiol using split aptamers.

Results and Discussion

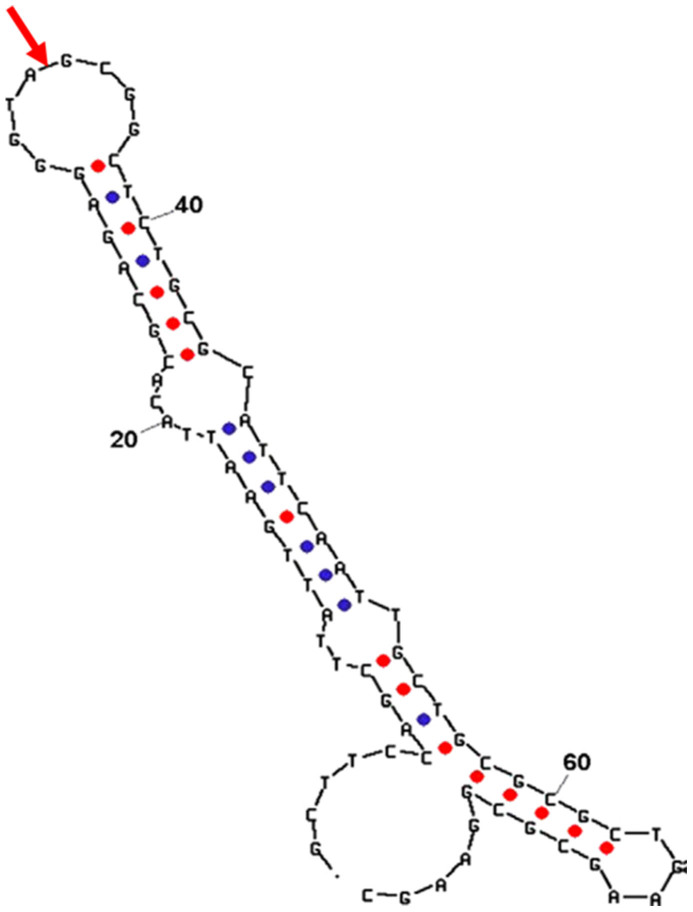

The secondary structure of the 76 mer 17β-estradiol aptamer has been illustrated in Figure 2 using a web-based tool mfold with the free-energy minimization algorithm26. The 33A/34G site in the loop near the center of the sequence was selected to split the aptamer into two fragments (33 mer P1 and 43 mer P2), which was expected to have the minimum effect on the complete conformation. Table 1 lists the 76 mer 17β-estradiol aptamer and the P1 and P2 sequences, which were synthesized by Sangon Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Figure 2. Secondary structure of the 17β-estradiol aptamer illustrated in the report of Kim et al.26.

The red arrow indicates the splitting site, where P1 and P2 are shown.

Table 1. Aptamer and complementary sequences used in this study.

| Description | Length | Sequence(5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| 17β-estradiol aptamer | 76 mer | GCTTCCAGCTTATTGAATTACACGCAGAGGGTAGCGGCTCTGCGCATTCAATTGCTGCGCGCTGAAGCGCGGAAGC |

| P1 | 33 mer | GCTTCCAGCTTATTGAATTACACGCAGAGGGTA |

| P2 | 43 mer | GCGGCTCTGCGCATTCAATTGCTGCGCGCTGAAGCGCGGAAGC |

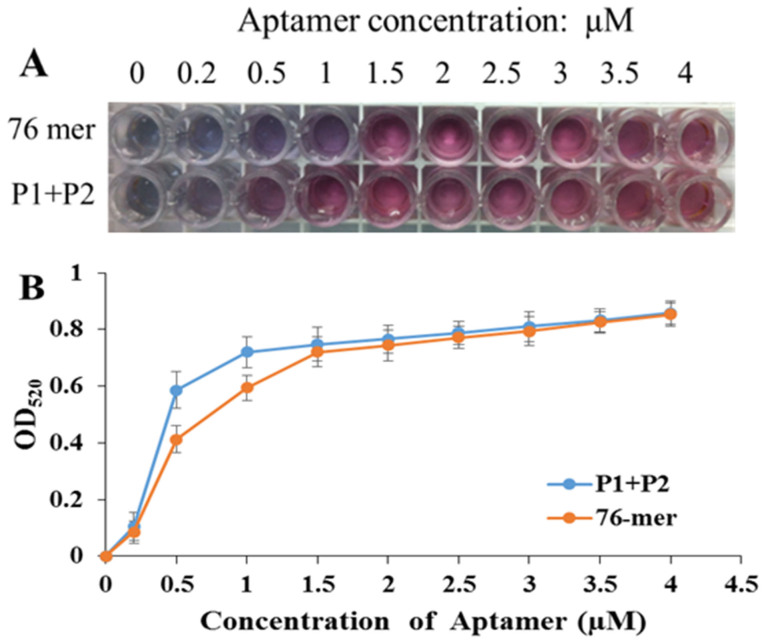

To develop a sensitive AuNP based colorimetric aptasensor, the minimum aptamer concentration used to stabilize AuNPs should be determined. As shown in Figure 3, with the same concentration of NaCl (125 mM), 1 μM P1 + P2 could stabilize AuNPs, whereas at least 1.5 μM of the original long 76 mer aptamer was needed to keep the AuNP solution red. As short ssDNAs have a more fragile structure with more bases exposed, they are more likely to adsorb onto the surface of AuNPs due to the coordination between Au and N atoms in DNA bases16,17,18,19,20. However, long ssDNAs are not easily adsorbed on AuNPs because of higher rigidity in the structure with the hidden status of the bases positioned inside the double-stranded. Furthermore, 1 μM P1 + P2 provides the same protection for AuNPs' resistance against salt-induced aggregation as 1.5 μM original long aptamer with about 0.5 μM bases lost. It might be concluded that it is the mole number of ssDNAs, rather than the number of nucleotides, plays a more important role in stabilizing AuNPs against salt-induced aggregation.

Figure 3. Comparison of the minimum aptamer concentrations of the 76 mer aptamer and split P1 + P2 to stabilize AuNPs with 125 mM NaCl.

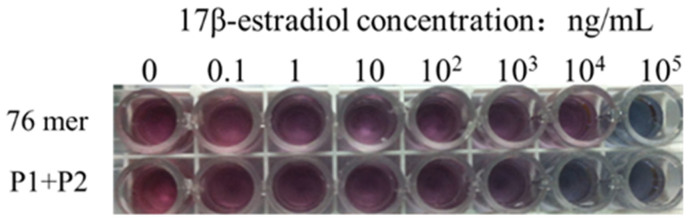

We first tested the application of the split P1 and P2 for 17β-estradiol detection with an unmodified AuNP based colorimetric aptasensor. 1 μM of the P1 + P2 was incubated with different concentrations of 17β-estradiol for 5 min and then mixed with AuNPs for another 5 min. After that, NaCl was added. The same experiment was performed with the original 76 mer aptamer. As shown in Figure 4, with the 17β-estradiol concentration increasing, the AuNP solution changed to purple and even blue at high concentration of 17β-estradiol. And interestingly, we found that for the original 76 mer aptamer, naked eyes could detect color change with 10 ng/mL 17β-estradiol or above, while for the P1 + P2 based assay, as low as 1 ng/mL 17β-estradiol showed obvious changes in color. That means the sensitivity is improved by nearly 10-fold with the split P1 and P2.

Figure 4. Photographs of the AuNP solutions adsorbing the 76 mer aptamer and split P1 + P2 under different concentrations of 17β-estradiol.

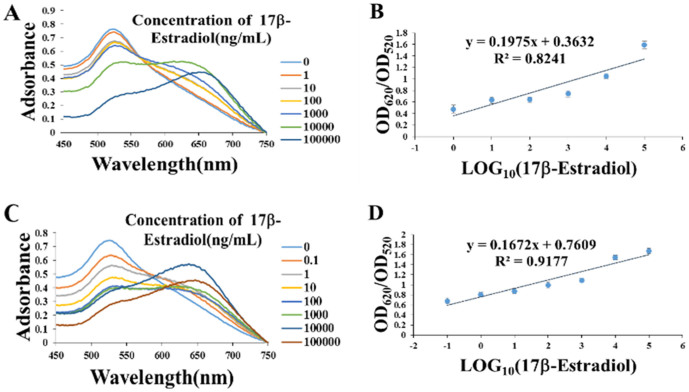

To further analyze the aptasensor sensitivity as well as the linear range of 17β-estradiol detection, the absorption spectra of 450 nm to 750 nm were measured and the ratio of OD620/OD520 was plotted to the log 17β-estradiol concentration. As shown in Figure 5, for both the original 76 mer aptamer and the split P1 + P2 based aptasensor, the presence of increasing concentrations of 17β-estradiol from 0 ng/mL to 105 ng/mL leads to obvious adsorbance decease of A520 and increase of A600–700. The linear relationship of the ratio of OD620/OD520 vs the 17β-estradiol concentration indicates that the 17β-estradiol concentration can be quantitatively derived. For the 76 mer aptamer, the detection limit is 1 ng/mL with a dynamic range from 1 ng/mL to 105 ng/mL (Figure 5A and 5B). For the split P1 + P2, the detection limit is 0.1 ng/mL with a dynamic range from 0.1 ng/mL to 105 ng/mL (Figure 5C and 5D). That means, for the split P1 + P2, the sensitivity was increased by 10-fold. One reason for the increased sensitivity may attribute to the lower adsorption concentration of the split P1 + P2 since 17β-estradiol competitively bind to P1 + P2 or the 76 mer aptamer with AuNPs. Another reason may attribute to a lower affinity of short-sequence P1 + P2 to AuNPs than the 76 mer aptamer, which bind more tightly to AuNPs due to the establishment of more contact points on the AuNP surface.

Figure 5. Sensitivity for detecting 17β-estradiol with the original 76 mer aptamer or split P1 + P2 adsorbed onto AuNPs.

(A) Absorption spectra of the AuNP solutions with 76 mer aptamer adsorption under different 17β-estradiol concentrations. (B) Typical calibration curve for 17β-estradiol with the 76 mer aptamer adsorbed AuNPs. (C) Absorption spectra of the AuNP solutions with P1 + P2 adsorption under different 17β-estradiol concentrations. (D) Typical calibration curve for 17β-estradiol with P1 + P2 adsorbed AuNPs.

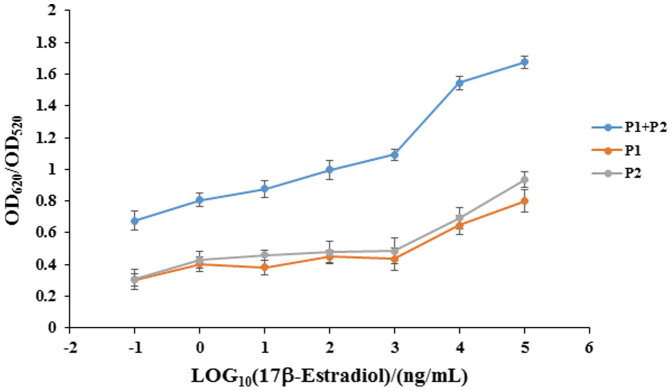

However, there is another question on whether the split P1 and P2 can still specifically bind to 17β-estradiol. To answer this question, the split P1 and P2 were separately adsorbed to the AuNP surface to perform 17β-estradiol detection. As could be observed in Figure 6, either P1 or P2 can be used to detect 17β-estradiol even the detection limit was decreased to 10,000 ng/mL. It is easy to understand that either of the split P1 and P2 has a low affinity to 17β-estradiol since the binding sites have been reduced greatly. Whatever, the result proves that both of the split P1 and P2 retained partial binding capacity of the original 76-mer aptamer and they can be used for 17β-estradiol detection after adsorbed onto AuNPs simultaneously or independently.

Figure 6. Control experiments to verify that the split P1 and P2 can retain partial affinity to 17β-estradiol.

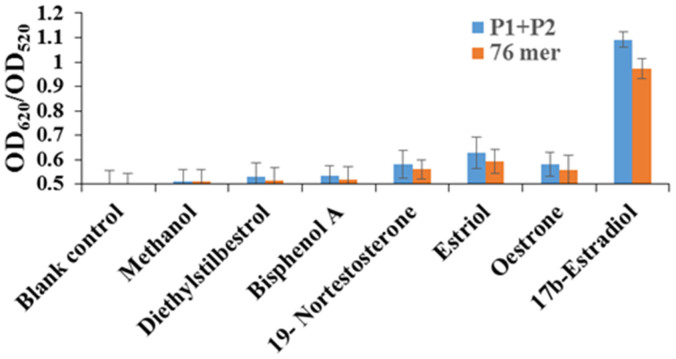

We know the specificity of an aptasensor relies on high selectivity of the aptamer. To determine whether P1 + P2 still retains the original 76 mer aptamer's specificity after splitting, we tested the sensing platform against several structural analogues, estrogen-like compounds, and solvent control methanol (for 17β-estradiol dissolution). As shown in Figure 7, for both the original 76 mer aptamer and P1 + P2, the structural analogues of estriol, estrone, and 19-nortestosterone all induced a slight increase in the ratio of OD620/OD520 at 1000 ng/mL. This can be attributed to their cyclopentanoperhydrophenanthrene structures as the same as 17β-estradiol. While for the estrogen-like compounds bisphenol A and diethylstilbestrol at 1000 ng/mL and solvent control methanol, the increase in the ratio of OD620/OD520 is almost negligible for both the original 76 mer aptamer and P1 + P2. The result proves that there is no significant difference in specificity between P1 + P2 and the original 76 mer aptamer and the split P1 and P2 still retain the specificity of the original aptamer.

Figure 7. Selectivity evaluation of the P1 + P2 or original 76 mer aptamer based AuNP colorimetric assay.

In summary, we have demonstrated a highly sensitive colorimetric aptasensor with two split fragments P1 and P2 of the 17β-estradiol aptamer adsorbed on the surface of AuNPs. Our results proved that the split P1 + P2 still retained the original 76 mer aptamer's affinity and specificity and even increased the detection limit by 10 times since as low as 0.1 ng/mL 17β-estradiol can be detected. The reasons for the increased sensitivity may be both the lower adsorption concentration and lower affinity to AuNPs of short ssDNA sequences. In this study, attention should also be drawn to the cut site on the original aptamer since it was casually selected in the loop near the center of the sequence on the base in the secondary structure of the predicted 76 mer aptamer. We have reasons to believe there may be other splice sites to give higher sensitivity in producing two, three, or even more fragments with the AuNP based colorimetric aptasensor. The illustration of the complex 17β-estradiol-aptamer structure may greatly help find these sites. Whatever, our study provided a new way to make use of long aptamers for a highly sensitive AuNP based colorimetric aptasensor. Besides, the split-aptamer strategy may provide a chance for the development of a sandwich assay for targets with only one aptamer.

Methods

Materials and reagents

The sequences of the 17β-estradiol binding aptamer26 and the split P1 and P2 fragments were synthesized by Shanghai Sangon Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), as listed in Table 1. The lyophilized powder was dissolved in ultrapure water and stored at 4°C before use. The concentration of the oligonucleotide was determined by measuring the UV absorbance at 260 nm. Estriol, estrone, chloroauric acid (HAuCl4), and sodium citrate (C6H5Na3O7) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Bisphenol A, 17β-estradiol, 19-nortestosterone, and diethylstilbestrol were purchased from Dr. Ehrenstorfer GmbH (Augsburg, Germany). Other chemicals including sodium chloride and methanol were all purchased from Beijing Chemical Reagent Company (Beijing, China). All of the chemicals were of at least analytical grade.

Synthesis of citrate-protected AuNPs

AuNPs were synthesized using the classical citrate reduction method34. Briefly, colloidal AuNPs with an average diameter of 13 nm were prepared by rapidly injecting a sodium citrate solution (10 mL, 38.8 mM) into a boiling aqueous solution of HAuCl4 (100 mL, 1 mM) with vigorous stirring. An obvious color change of the reaction mixture was observed from transparent to dark blue and finally wine red. After being boiled for 20 min, the reaction flask was removed from the heat to allow the reaction solution to cool at room temperature.

Detection procedure using an AuNP based colorimetric aptasensor

To develop an AuNP based colorimetric aptasensor for 17β-estradiol detection, 50 μL 1.5 μM 76 mer 17β-estradiol aptamer or 1 μM split P1 + P2 was incubated with 50 μL target for 5 min at room temperature, and then 50 μL AuNP solution was added and kept for another 5 min at room temperature. Subsequently, 10 μL of 2 M NaCl was transferred to the solution to give a final volume of 160 μL and mixed thoroughly. After the solution was equilibrated for 5 min, the resulting solution was transferred to a 10 mm quartz cuvette. The UV–vis absorption spectrum was measured over the wavelength range from 450 nm to 750 nm with respect to water and finally photographs were taken with a Sony TX20 digital camera.

Author Contributions

A.C. and S.Y. conceived the project, J.L., W.B., S.N. and C.Z. performed the experiment and data analysis. A.C. and J.L. wrote the main manuscript and J.L. and W.B. prepared all figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by International Science & Technology Cooperation Program of China (2012DFA31140). The authors express their gratitude for the support.

References

- Tuerk C. & Gold L. Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science 249, 505–510 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellington A. D. & Szostak J. W. In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature 346, 818–822 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliuk A. B., Hu L. H. & Tao W. A. Aptamer in Bioanalytical Applications. Anal. Chem. 83, 4440–4452 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Xiang Y., Lu Y. & Crooks R. M. Aptamer-based origami paper analytical device for electrochemical detection of adenosine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 51, 6925–6928 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho M. Y., D'Souza N. & Migliorato P. Electrochemical aptamer-based sandwich assays for the detection of explosives. Anal. Chem. 84, 4245–4247 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B., Jung I. H., Kang M., Shim H. K. & Woo H. Y. Cationic conjugated polyelectrolytes-triggered conformational change of molecular beacon aptamer for highly sensitive and selective potassium ion detection. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 3133–3138 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y. et al. Electrochemical aptasensor based on the dual-amplification of G-quadruplex horseradish peroxidase-mimicking DNAzyme and blocking reagent-horseradish peroxidase. Biosens. Bioelectron. 26, 4236–4240 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman R., Liu X. & Willner I. Chemiluminescent and chemiluminescence resonance energy transfer (CRET) detection of DNA, metal ions, and aptamer-substrate complexes using hemin/G-quadruplexes and CdSe/ZnS quantum dots. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 11597–11604 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. C., Wei S. C., Wu T. H., Lee C. H. & Lin C. W. Aptamer-based colorimetric detection of platelet-derived growth factor using unmodified gold nanoparticles. Biosens. Bioelectron. 42C, 119–123 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z. et al. An aptamer cross-linked hydrogel as a colorimetric platform for visual detection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 49, 1052–1056 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. & Rothberg L. Colorimetric detection of DNA sequences based on electrostatic interactions with unmodified gold nanoparticles. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101, 14036–14039 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Wang Y., Marty J. L. & Yang X. R. Aptamer-based colorimetric biosensing of Ochratoxin A using unmodified gold nanoparticles indicator. Biosens. Bioelectron. 26, 2724–2727 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y., Li L. D., Mu X. J. & Guo L. Aptamer-gold nanoparticle-based colorimetric assay for the sensitive detection of thrombin. Sensor. Actuat. B-Chem. 177, 818–825 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Storhoff J. J. et al. What controls the optical properties of DNA-linked gold nanoparticle assemblies? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 4640–4650 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S. K. & Pal T. Interparticle coupling effect on the surface plasmon resonance of gold nanoparticles: from theory to applications. Chem. Rev. 107, 4797–4862 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Liu X., Hu X., Song S. & Fan C. Unmodified gold nanoparticles as a colorimetric probe for potassium DNA aptamers. Chem. Commun. 36, 3780–3782 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H., Li B., Li J., Wang E. & Dong S. Simple and sensitive aptamer-based colorimetric sensing of protein using unmodified gold nanoparticle probes. Chem. Commun. 36, 3735–3737 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. W., Hsieh Y. T., Huang C. C., Lin Z. H. & Chang H. T. Detection of mercury(II) based on Hg2+ -DNA complexes inducing the aggregation of gold nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 19, 2242–2244 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demers L. M. et al. Thermal desorption behavior and binding properties of DNA bases and nucleosides on gold. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 11248–11249 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Servos M. R. & Liu J. Surface science of DNA adsorption onto citrate-capped gold nanoparticles. Langmuir 28, 3896–3902 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Wang Y., Marty J. L. & Yang X. Aptamer-based colorimetric biosensing of Ochratoxin A using unmodified gold nanoparticles indicator. Biosens. Bioelectron. 26, 2724–2727 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song K. M., Jeong E., Jeon W., Cho M. & Ban C. Aptasensor for ampicillin using gold nanoparticle based dual fluorescence-colorimetric methods. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 402, 2153–2161 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A. et al. High sensitive rapid visual detection of sulfadimethoxine by label-free aptasensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 42, 419–425 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei Z. et al. Ultrasensitive one-step rapid visual detection of bisphenol A in water samples by label-free aptasensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 39, 26–30 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. S. et al. A novel colorimetric aptasensor using gold nanoparticle for a highly sensitive and specific detection of oxytetracycline. Biosens. Bioelectron. 26, 1644–1649 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. S. et al. Electrochemical detection of 17beta-estradiol using DNA aptamer immobilized gold electrode chip. Biosens. Bioelectron. 22, 2525–2531 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta J. et al. In vitro selection and characterization of DNA aptamers recognizing chloramphenicol. J. Biotechnol. 155, 361–369 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon Y. S., Raston N. H. A. & Gu M. B. An ultra-sensitive colorimetric detection of tetracyclines using the shortest aptamer with highly enhanced affinity. Chem. Commun. 50, 40–42 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson E. M. & Rothberg L. J. Kinetics and Mechanism of Single-Stranded DNA Adsorption onto Citrate-Stabilized Gold Nanoparticles in Colloidal Solution. Langmuir 27, 1770–1777 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Servos M. R. & Liu J. W. Surface Science of DNA Adsorption onto Citrate-Capped Gold Nanoparticles. Langmuir 28, 3896–3902 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. S., Kim J. H., Kim I. A., Lee S. J. & Gu M. B. The affinity ratio--its pivotal role in gold nanoparticle-based competitive colorimetric aptasensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 26, 4058–4063 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H. S., Choo K. H., Lee B. & Choi S. J. The methods of identification, analysis, and removal of endocrine disrupting compounds (EDCs) in water. J. Hazard. Mater. 172, 1–12 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin G. G., Kookana R. S. & Ru Y. J. Occurrence and fate of hormone steroids in the environment. Environ. Int. 28, 545–551 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. & Lu Y. Preparation of aptamer-linked gold nanoparticle purple aggregates for colorimetric sensing of analytes. Nat. Protoc. 1, 246–252 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]