Abstract

Background:

Posterior-stabilized total knee prostheses were introduced to address instability secondary to loss of posterior cruciate ligament function, and they have either fixed or mobile bearings. Mobile bearings were developed to improve the function and longevity of total knee prostheses. In this study, the International Consortium of Orthopaedic Registries used a distributed health data network to study a large cohort of posterior-stabilized prostheses to determine if the outcome of a posterior-stabilized total knee prosthesis differs depending on whether it has a fixed or mobile-bearing design.

Methods:

Aggregated registry data were collected with a distributed health data network that was developed by the International Consortium of Orthopaedic Registries to reduce barriers to participation (e.g., security, proprietary, legal, and privacy issues) that have the potential to occur with the alternate centralized data warehouse approach. A distributed health data network is a decentralized model that allows secure storage and analysis of data from different registries. Each registry provided data on mobile and fixed-bearing posterior-stabilized prostheses implanted between 2001 and 2010. Only prostheses associated with primary total knee arthroplasties performed for the treatment of osteoarthritis were included. Prostheses with all types of fixation were included except for those with the rarely used reverse hybrid (cementless tibial and cemented femoral components) fixation. The use of patellar resurfacing was reported. The outcome of interest was time to first revision (for any reason). Multivariate meta-analysis was performed with linear mixed models with survival probability as the unit of analysis.

Results:

This study includes 137,616 posterior-stabilized knee prostheses; 62% were in female patients, and 17.6% had a mobile bearing. The results of the fixed-effects model indicate that in the first year the mobile-bearing posterior-stabilized prostheses had a significantly higher hazard ratio (1.86) than did the fixed-bearing posterior-stabilized prostheses (95% confidence interval, 1.28 to 2.7; p = 0.001). For all other time intervals, the mobile-bearing posterior-stabilized prostheses had higher hazard ratios; however, these differences were not significant.

Conclusions:

Mobile-bearing posterior-stabilized prostheses had an increased rate of revision compared with fixed-bearing posterior-stabilized prostheses. This difference was evident in the first year.

This study aimed to determine whether there is a difference in the rate of revision of fixed-bearing compared with mobile-bearing posterior-stabilized total knee prostheses. Posterior-stabilized total knee prostheses were introduced to address instability secondary to the loss of posterior cruciate ligament function. Some surgeons selectively use posterior-stabilized prostheses to address instability when there is a deficient posterior cruciate ligament or when there is substantial preoperative angular deformity that requires resection of the ligament. However, many surgeons use this type of design following routine resection of the posterior cruciate ligament in the belief that this approach allows for improved knee flexion and ease of ligament and flexion-extension gap balance1,2.

Posterior-stabilized total knee prostheses have either fixed or mobile bearings. Mobile bearings were developed in the hope of improving the function and longevity of total knee prostheses. They are most often used with posterior cruciate-retaining designs, but there are also a number of mobile-bearing posterior-stabilized total knee prostheses. The most common reason for revision of a total knee arthroplasty is aseptic loosening of the implant, with both wear and torque as contributing factors. Mobile bearings were introduced in an attempt to reduce polyethylene wear and possibly reduce torque at the bone-implant interface. In biomechanical testing, mobile bearings were found to reduce both contact stress and polyethylene wear; this has the potential to decrease the risk of revision, particularly in younger and more active patients3-7. It has also been argued that mobile bearings have the potential to enhance patellar tracking, reduce pain, enhance function, and reduce patellofemoral-related revision8.

Many studies have compared clinical and radiographic outcomes of mobile and fixed-bearing total knee prostheses4,5,7,9-12. One meta-analysis demonstrated an early reduction in anterior knee pain for patients with mobile-bearing total knee prostheses7. However, other studies have not identified any clinical or radiographic benefit for the use of mobile-bearing compared with fixed-bearing total knee prostheses5,9-11. A number of randomized controlled trials have examined comparative revision rates and found no difference, but these studies had limited follow-up and small numbers of patients5,10. In contrast, the authors of larger, registry-based studies have reported higher revision rates for mobile-bearing total knee prostheses6,13.

Very few studies have specifically compared fixed-bearing posterior-stabilized and mobile-bearing posterior-stabilized total knee prostheses. In a small number of studies, no differences in midterm functional and radiographic outcomes between patients with fixed and those with mobile-bearing posterior-stabilized prostheses were identified4,11,12. In one study with limited follow-up, implant survival rates were also reported to be similar14. It remains uncertain whether the outcome of posterior-stabilized prostheses differs depending on whether the prosthesis has a fixed or mobile bearing.

In the current study, the International Consortium of Orthopaedic Registries (ICOR) used a distributed health data network to examine a large cohort of posterior-stabilized prostheses to determine if the outcome of a posterior-stabilized total knee arthroplasty differs depending on whether the prosthesis has a fixed or mobile design.

Materials and Methods

Aggregated registry data were collected via a distributed health data network that was developed by ICOR. This approach was used to reduce barriers to participation (e.g., security, proprietary, legal, and privacy issues) that have the potential to occur with the alternate centralized data warehouse approach15,16. A distributed health data network is a decentralized model that allows secure storage and analysis of data from different registries17. Generally, the data from each registry are standardized (e.g., the data elements are operationalized) and provided at a level of aggregation most suitable for the detailed analysis of interest, with the aggregated data combined across registries18.

The first step undertaken to develop the health data network was to evaluate the variation in international practice patterns, including patient selection, technology use, and procedural detail. All interested registries participated, and a methodology committee discussed the inclusion of key variables for analytic purposes. Next, each registry with an interest in participating completed simple tables depicting the means and proportions of patient and procedure-related characteristics. Six national and regional registries (those of Kaiser Permanente [U.S.], Sweden, the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy, the Catalan region of Spain, Norway, and Australia) participated in this study.

Each registry provided data on mobile and fixed-bearing posterior-stabilized prostheses implanted between 2001 and 2010. Only the prostheses associated with primary total knee arthroplasties performed for the treatment of osteoarthritis were included. All types of fixation were included except for the rarely used reverse hybrid (cementless tibial and cemented femoral component) technique. The use of patellar resurfacing was reported. The outcome of interest was time to first revision (for any reason). The sample sizes by registry, mobility, age, sex, fixation method, and patellar-resurfacing status are presented in Table I.

TABLE I.

Distribution of Posterior-Stabilized Prostheses by Registry, Mobility, Age, Sex, Fixation Method, and Patellar-Resurfacing Status*

| U.S. (KP) | Australia | Italy (E-R) | Sweden | Norway | Spain (C) | |

| Fixed-bearing PS | ||||||

| Age in yr | ||||||

| <45 | 203 (0.6) | 281 (0.5) | 13 (0.2) | 13 (0.2) | 7 (0.9) | 4 (0) |

| 45 to 55 | 3047 (8.4) | 3631 (6.9) | 136 (1.6) | 333 (6.3) | 45 (5.8) | 69 (0.7) |

| 56 to 65 | 10,768 (29.8) | 14,354 (27.4) | 1161 (13.8) | 1282 (24.2) | 169 (21.8) | 835 (8.1) |

| >65 | 22,149 (61.2) | 34,141 (65.1) | 7095 (84.4) | 3664 (69.2) | 553 (71.4) | 9384 (91.2) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 13,327 (36.8) | 22,228 (42.4) | 2148 (25.6) | 1973 (37.3) | 201 (26.0) | 2969 (28.8) |

| Female | 22,840 (63.2) | 30,179 (57.6) | 6257 (74.4) | 3319 (62.7) | 573 (74.0) | 7323 (71.2) |

| Fixation | ||||||

| Cementless | 926 (2.6) | 2970 (5.7) | 132 (1.6) | 25 (0.5) | 15 (1.9) | 222 (2.2) |

| Hybrid | 774 (2.1) | 2960 (5.6) | 64 (0.8) | 3 (0.1) | 266 (34.4) | 1253 (12.2) |

| Cemented | 34,467 (95.3) | 46,477 (88.7) | 8209 (97.7) | 5264 (99.5) | 493 (63.7) | 8817 (85.7) |

| Resurfacing | ||||||

| No | 218 (0.6) | 21,357 (40.8) | 6246 (74.3) | 3310 (62.5) | 746 (96.4) | 5184 (50.4) |

| Yes | 35,949 (99.4) | 31,050 (59.2) | 2159 (25.7) | 1982 (37.5) | 28 (3.6) | 5108 (49.6) |

| Mobile-bearing PS | ||||||

| Age in yr | ||||||

| <45 | 51 (1.1) | 101 (0.8) | 6 (0.1) | 7 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.9) |

| 45 to 55 | 714 (15.4) | 1033 (7.7) | 84 (1.5) | 58 (12.0) | 0 (0) | 5 (4.6) |

| 56 to 65 | 1955 (42.1) | 3860 (28.9) | 746 (13.1) | 177 (36.6) | 0 (0) | 15 (13.8) |

| >65 | 1929 (41.5) | 8358 (62.6) | 4850 (85.3) | 241 (49.9) | 0 (0) | 88 (80.7) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1880 (40.4) | 5968 (44.7) | 1477 (26.0) | 220 (45.5) | 0 (0) | 38 (34.9) |

| Female | 2769 (59.6) | 7384 (55.3) | 4209 (74.0) | 263 (54.5) | 0 (0) | 71 (65.1) |

| Fixation | ||||||

| Cementless | 39 (0.8) | 773 (5.8) | 397 (7.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 32 (29.4) |

| Hybrid | 41 (0.9) | 1768 (13.2) | 101 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.8) |

| Cemented | 4569 (98.3) | 10,811 (81.0) | 5188 (91.2) | 483 (100) | 0 (0) | 74 (67.9) |

| Resurfacing | ||||||

| No | 48 (1.0) | 5412 (40.5) | 4552 (80.1) | 296 (61.3) | 0 (0) | 38 (34.9) |

| Yes | 4601 (99.0) | 7940 (59.5) | 1134 (19.9) | 187 (38.7) | 0 (0) | 71 (65.1) |

The values are given as the number of each, with the percentage in parentheses. KP = Kaiser Permanente, E-R = Emilia-Romagna region, C = Catalan region, and PS = posterior-stabilized prostheses.

Statistical Analyses

Multivariate meta-analysis was performed with linear mixed models, with survival probability as the unit of analysis19. The models estimated the residual covariances precisely as described previously20 and also implemented a transformation21-23 to ensure that the models could be fitted with existing SAS software (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). Survival probabilities and their standard errors were extracted from each registry for each unique combination of the covariates (e.g., mobility, patellar-resurfacing status, and patient age) at each distinct event time. Each unique combination was grouped into yearly time intervals, with only the earliest observation in that interval retained.

We fitted two models, one that treated the registries as a set of fixed effects and one that treated them as random effects. Although the random-effects model offers some inferential advantage for combining studies24,25, with few observational data and/or registries the estimated between-registry variation in the random-effects model can be rather inaccurate. Moreover, the absence of randomization for mobility groups could lead to confounding because of registry-level effects, which the random-effects model does not address but the fixed-effects model does26,27. Therefore, we gave preference to interpretation of the fixed-effects model, particularly when the parameter estimates differed substantially between the fixed and random-effects models26,27. Accordingly, we present the results of the fixed-effects model below and include the results of the random-effects model in the Appendix (Table III).

TABLE III.

Results from the Random-Effects Model: Hazard Ratios for Revision After Mobile Compared with Fixed-Bearing Posterior-Stabilized Knee Replacement*

| Mobile-Bearing PS, Relative to Fixed-Bearing PS | HR (95% CI) | P Value |

| Time in yr | ||

| 0 to 1 | 1.76 (1.215-2.55) | 0.003 |

| 1 to 2 | 1.062 (0.934-1.208) | 0.357 |

| 2 to 3 | 1.017 (0.915-1.13) | 0.759 |

| 3 to 4 | 1.037 (0.939-1.145) | 0.475 |

| 4 to 5 | 1.012 (0.917-1.118) | 0.809 |

| 5 to 6 | 1.012 (0.908-1.128) | 0.831 |

| 6 to 7 | 1.023 (0.869-1.205) | 0.785 |

| 7 to 8 | 1.06 (0.811-1.386) | 0.667 |

| 8 to 9 | 1.059 (0.769-1.458) | 0.726 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | Ref. | |

| Female | 0.799 (0.747-0.854) | <0.001 |

| Age in yr | ||

| >65 | Ref. | |

| ≤65 | 0.556 (0.52-0.595) | <0.001 |

| Resurfacing | ||

| No | Ref. | |

| Yes | 0.67 (0.62-0.724) | <0.001 |

| Fixation | ||

| Cemented | Ref. | |

| Cementless | 1.491 (1.259-1.766) | <0.001 |

| Hybrid | 1.280 (1.01-1.491) | 0.002 |

| Fixed registry effects† | — | — |

| Random registry effects‡ | — | — |

Confidence intervals and p values are based on a t distribution. HR = hazard ratio, CI = confidence interval, and PS = posterior-stabilized knee prostheses.

Fixed registry effects were included in this model (five coefficients), but the results are omitted from this table because a precondition of data sharing was no reporting of comparisons among registries. The estimated intercept of the fixed registry effects was −5.522 (standard error, 0.134).

The estimated intercept of the random registry effects was 0.020 (standard error, 0.020).

The results from the linear mixed models are presented as hazard ratios (HRs) for revision, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and a p value. SAS (version 9.2) was used for all analyses. Further details regarding the model fitting are presented in the Appendix.

Results

The study includes 137,616 posterior-stabilized knee prostheses; 17.6% had a mobile bearing and 62% were in female patients. Five-year revision rates for all types of total knee arthroplasties varied across registries, from 1.8% to 3.5%. Distribution of fixed and mobile-bearing posterior-stabilized procedures by registry, mobility, age, sex, and patellar-resurfacing status is reported in Table I.

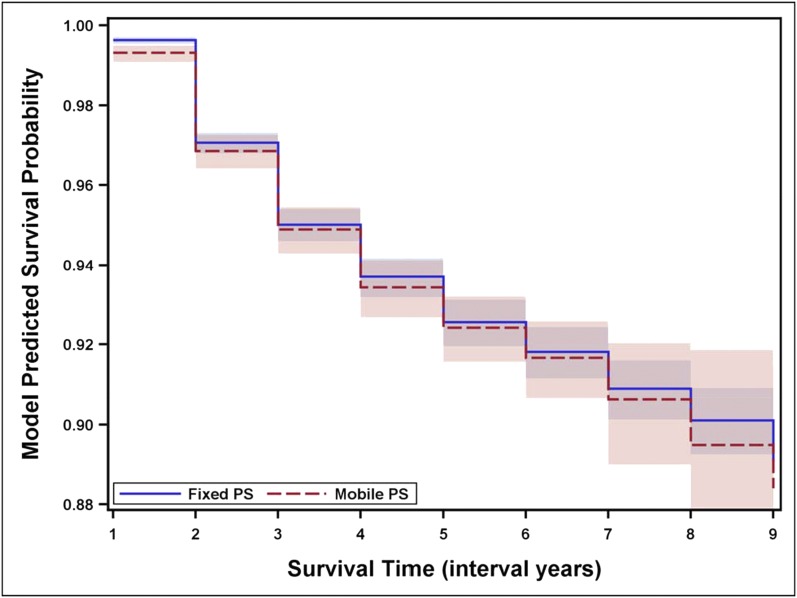

From each registry and each covariate profile (based on age, mobility, sex, and patellar-resurfacing status), estimates of survival probabilities and their standard error were obtained at ten time intervals (year zero to one through year nine to ten). The complementary log-log transformation of these survival estimates was combined in a general linear model with a fixed registry effect (Table II) and in a linear mixed model with a registry-level random intercept (see Appendix). There was no evidence of interactions of mobility and age, sex, or patellar-resurfacing status. The details of the model-fitting procedure are given in the Appendix. The results of the fixed-effects model provide the hazard ratio for revision of mobile-bearing posterior-stabilized prostheses compared with that for revision of fixed-bearing posterior-stabilized prostheses at different time points (Table II). The model indicates that in the first time interval (year zero to one), mobile-bearing posterior-stabilized prostheses had a significantly higher hazard ratio for revision (1.86; 95% CI = 1.28 to 2.7, p = 0.001). For all other time intervals, mobile-bearing posterior-stabilized prostheses had higher hazard ratios; however, these differences were not significant. The survival probabilities (estimated from the model) for fixed and mobile-bearing knee prostheses are given in Figure 1.

TABLE II.

Results from the Fixed-Effects Model: Hazard Ratios for Revision After Mobile Compared with Fixed-Bearing Posterior-Stabilized Knee Replacement*

| Mobile-Bearing PS, Relative to Fixed-Bearing PS | HR† (95% CI) | P Value |

| Time in yr | ||

| 0 to 1 | 1.858 (1.281-2.695) | 0.001 |

| 1 to 2 | 1.072 (0.943-1.218) | 0.291 |

| 2 to 3 | 1.024 (0.922-1.137) | 0.661 |

| 3 to 4 | 1.044 (0.946-1.153) | 0.393 |

| 4 to 5 | 1.019 (0.923-1.124) | 0.709 |

| 5 to 6 | 1.019 (0.915-1.135) | 0.735 |

| 6 to 7 | 1.03 (0.875-1.212) | 0.723 |

| 7 to 8 | 1.066 (0.816-1.392) | 0.639 |

| 8 to 9 | 1.066 (0.775-1.467) | 0.694 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | Ref. | |

| Female | 0.8 (0.748-0.855) | <0.001 |

| Age in yr | ||

| >65 | Ref. | |

| ≤65 | 0.555 (0.518-0.593) | <0.001 |

| Resurfacing | ||

| No | Ref. | |

| Yes | 0.676 (0.626-0.73) | <0.001 |

| Fixation | ||

| Cemented | Ref. | |

| Cementless | 1.498 (1.265-1.773) | <0.001 |

| Hybrid | 1.27 (1.091-1.478) | 0.002 |

| Fixed registry effects† | — | — |

Confidence intervals and p values are based on a Z distribution. HR = hazard ratio, CI = confidence interval, and PS = posterior-stabilized prostheses.

Fixed registry effects were included in this model (five coefficients), but the results are omitted from this table because a precondition of data sharing was no reporting of comparisons among registries. The estimated fixed intercept was −5.601 (standard error, 0.122).

Fig. 1.

Graph comparing the survival probability of the fixed and mobile-bearing posterior-stabilized (PS) prostheses over time. The fixed-effects model outlined in Table II is depicted. The x-axis values of 1 through 9 correspond to the interval years zero to one through eight to nine. The shading indicates the 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

Mobile-bearing posterior-stabilized prostheses have an increased rate of revision compared with fixed-bearing posterior-stabilized prostheses. This difference is evident in the first year. After that, the difference is maintained, with the revision rates for both fixed and mobile-bearing posterior-stabilized prostheses continuing to increase at a similar rate. There was no evidence of interactions of mobility and age, sex, or patellar-resurfacing status.

The major advantage of this study is that it includes a large number of procedures with posterior-stabilized prostheses. Mobile-bearing posterior-stabilized prostheses in particular are not commonly used, but in this study we were able to compare the outcome with that for fixed-bearing posterior-stabilized prostheses. There are two major limitations to this study. First, although there was evidence of a difference in outcome, the reasons for that difference are not apparent. This is because the reasons for revision were not identified in the current study. Second, the performance of individual types of prostheses was not analyzed, so it remains uncertain whether the higher rate of revision for mobile-bearing posterior-stabilized prostheses is true for all mobile-bearing posterior-stabilized devices or is only evident for some.

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that despite some potential theoretical advantages of the use of posterior-stabilized mobile bearings, there is no evidence that this mobile-bearing design is associated with a reduced risk of revision when combined with a posterior-stabilized design. On the contrary, the risk of revision is increased compared with when fixed-bearing posterior-stabilized prostheses are used.

Appendix: Model-Fitting Details

For the models comparing mobile and fixed-bearing posterior-stabilized knee prostheses, we examined the sensitivity of the results to outlier observations (for all data and with observations that had a standard error of more than 0.05, more than 0.025, or more than 0.0125 removed). We determined that removing the observations with a standard error of more than 0.025 would sufficiently limit the inaccuracies that arose from observations involving unreliable information. We began with a model that includes an intercept, mobility, patient age, sex, fixation method, patellar-resurfacing status, time, mobility by time interaction, and registry-level random effects for intercept and residual variance fixed at one. A likelihood ratio test with maximum likelihood estimation found significant improvement as a result of including the mobility by time interaction terms (χ2 [9] = 100.077; p < 0.0001), and therefore they were included in the model. Lastly, we explored whether there was evidence of an interaction between mobility and patellar-resurfacing status, fixation method, or sex. A global test of all of these two-way interactions indicated no evidence of an effect (χ2 [5] = 7.851; p = 0.165).

Footnotes

Disclosure: One or more of the authors received payments or services, either directly or indirectly (i.e., via his or her institution), from a third party in support of an aspect of this work. In addition, one or more of the authors, or his or her institution, has had a financial relationship, in the thirty-six months prior to submission of this work, with an entity in the biomedical arena that could be perceived to influence or have the potential to influence what is written in this work. No author has had any other relationships, or has engaged in any other activities, that could be perceived to influence or have the potential to influence what is written in this work. The complete Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest submitted by authors are always provided with the online version of the article.

References

- 1.Bercik MJ, Joshi A, Parvizi J. Posterior cruciate-retaining versus posterior-stabilized total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2013March;28(3):439-44 Epub 2013 Feb 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engh GA. Is long-term survivorship really significantly better with cruciate-retaining total knee implants?: Commentary on an article by Matthew P. Abdel, MD, et al.: “Increased long-term survival of posterior cruciate-retaining versus posterior cruciate-stabilizing total knee replacements.” J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011November16;93(22):e136: (1-2). Epub 2012 Jan 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Callaghan JJ, Insall JN, Greenwald AS, Dennis DA, Komistek RD, Murray DW, Bourne RB, Rorabeck CH, Dorr LD. Mobile-bearing knee replacement: concepts and results. Instr Course Lect. 2001;50:431-49 Epub 2001 May 25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasegawa M, Sudo A, Uchida A. Staged bilateral mobile-bearing and fixed-bearing total knee arthroplasty in the same patients: a prospective comparison of a posterior-stabilized prosthesis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009March;17(3):237-43 Epub 2008 Nov 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim YH, Yoon SH, Kim JS. The long-term results of simultaneous fixed-bearing and mobile-bearing total knee replacements performed in the same patient. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007October;89(10):1317-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Namba RS, Inacio MC, Paxton EW, Ake CF, Wang C, Gross TP, Marinac-Dabic D, Sedrakyan A. Risk of revision for fixed versus mobile-bearing primary total knee replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012November7;94(21):1929-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith H, Jan M, Mahomed NN, Davey JR, Gandhi R. Meta-analysis and systematic review of clinical outcomes comparing mobile bearing and fixed bearing total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011December;26(8):1205-13 Epub 2011 Feb 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sawaguchi N, Majima T, Ishigaki T, Mori N, Terashima T, Minami A. Mobile-bearing total knee arthroplasty improves patellar tracking and patellofemoral contact stress: in vivo measurements in the same patients. J Arthroplasty. 2010September;25(6):920-5 Epub 2009 Sep 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lädermann A, Lübbeke A, Stern R, Riand N, Fritschy D. Fixed-bearing versus mobile-bearing total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomised, clinical and radiological study with mid-term results at 7 years. Knee. 2008June;15(3):206-10 Epub 2008 Mar 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carothers JT, Kim RH, Dennis DA, Southworth C. Mobile-bearing total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2011June;26(4):537-42 Epub 2010 Jul 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breugem SJ, van Ooij B, Haverkamp D, Sierevelt IN, van Dijk CN. No difference in anterior knee pain between a fixed and a mobile posterior stabilized total knee arthroplasty after 7.9 years. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014March;22(3):509-16 Epub 2012 Nov 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gioe TJ, Glynn J, Sembrano J, Suthers K, Santos ER, Singh J. Mobile and fixed-bearing (all-polyethylene tibial component) total knee arthroplasty designs. A prospective randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009September;91(9):2104-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gøthesen O, Espehaug B, Havelin L, Petursson G, Lygre S, Ellison P, Hallan G, Furnes O. Survival rates and causes of revision in cemented primary total knee replacement: a report from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1994-2009. Bone Joint J. 2013May;95(5):636-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahoney OM, Kinsey TL, D’Errico TJ, Shen J. The John Insall Award: no functional advantage of a mobile bearing posterior stabilized TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012January;470(1):33-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown JS, Holmes JH, Shah K, Hall K, Lazarus R, Platt R. Distributed health data networks: a practical and preferred approach to multi-institutional evaluations of comparative effectiveness, safety, and quality of care. Med Care. 2010June;48(6)(Suppl):S45-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sedrakyan A, Paxton EW, Marinac-Dabic D. Stages and tools for multinational collaboration: the perspective from the coordinating center of the International Consortium of Orthopaedic Registries (ICOR). J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011December21;93(Suppl 3):76-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maro JC, Platt R, Holmes JH, Strom BL, Hennessy S, Lazarus R, Brown JS. Design of a national distributed health data network. Ann Intern Med. 2009September1;151(5):341-4 Epub 2009 Jul 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sedrakyan A, Paxton EW, Phillips C, Namba R, Funahashi T, Barber T, Sculco T, Padgett D, Wright T, Marinac-Dabic D. The International Consortium of Orthopaedic Registries: overview and summary. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011December21;93(Suppl 3):1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arends LR, Hunink MG, Stijnen T. Meta-analysis of summary survival curve data. Stat Med. 2008September30;27(22):4381-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dear KB. Iterative generalized least squares for meta-analysis of survival data at multiple times. Biometrics. 1994December;50(4):989-1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kutner MH, Nachtsheim CJ, Neter J, Li W. Applied linear statistical models. 5th ed.Boston: McGraw-Hill Irwin; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalaian HA, Raudenbush SW. A multivariate mixed linear model for meta-analysis. Psychol Methods. 1996;1:227-35. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheung MWL. A model for integrating fixed-, random-, and mixed-effects meta-analyses into structural equation modeling. Psychol Methods. 2008September;13(3):182-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986September;7(3):177-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hedges LV, Vevea JL. Fixed- and random-effects models in meta-analysis. Psychol Methods. 1998;3:486-504. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Localio AR, Berlin JA, Ten Have TR, Kimmel SE. Adjustments for center in multicenter studies: an overview. Ann Intern Med. 2001July17;135(2):112-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allison PD. Fixed effects regression models. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]