Abstract

Human ribonucleotide reductase (hRNR) is a target of nucleotide chemotherapeutics in clinical use. The nucleotide-induced oligomeric regulation of hRNR subunit α is increasingly being recognized as an innate and drug-relevant mechanism for enzyme activity modulation. In the presence of negative feedback inhibitor dATP and leukemia drug clofarabine nucleotides, hRNR-α assembles into catalytically inert hexameric complexes, whereas nucleotide effectors that govern substrate specificity typically trigger α dimerization. Currently, both knowledge of and tools to interrogate the oligomeric assembly pathway of RNR in any species in real time are lacking. We here developed a fluorimetric assay that reliably reports on oligomeric state changes of α with high sensitivity. The oligomerization-directed fluorescence quenching of hRNR-α covalently labeled with two fluorophores allows direct readout of hRNR dimeric and hexameric states. We applied the newly developed platform to reveal the timescales of α self-assembly driven by the feedback regulator dATP. This information is currently unavailable despite the pharmaceutical relevance of hRNR oligomeric regulation.

Keywords: feedback inhibitor, oligomeric regulation, fluorescence reporter assay, stopped-flow kinetics, human ribonucleotide reductase

Introduction

Feedback modulation is a central regulatory component in cellular information relay and decision making.[1] Aberrant processing of feedback circuits is often associated with disease phenotypes.[1-3] As a central regulator of nucleotide metabolism, ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) is a key drug target enzyme operating under tight feedback regulation.[4–9] Recent biophysical and structural studies have shown that the feedback regulation of RNR imposed by the metabolite dATP—a ubiquitous mechanism in RNRs from yeast, mice and humans—is coordinated with nucleotide-induced oligomerization of the RNR large subunit α.[8–14] However, neither the timescale of the self-assembly nor the identity of the transient intermediates involved in the assembly process have been interrogated in RNR from any species.

The human RNR (hRNR) holocomplex, composed of α and β subunits, catalyzes the rate-limiting conversion of nucleoside diphosphates (NDPs) to their deoxy forms (dNDPs) in the de novo biosynthesis pathway of dNTPs required for DNA replication and repair.[4–9] hRNR activity is positively correlated with cancer cell growth and suppressing hRNR activity is an effective strategy for repressing tumor survival, as demonstrated by a wealth of clinically used nucleoside antimetabolites.[9,15,16] The catalytic activity and substrate specificity of hRNR are tightly regulated allosterically. This allosteric regulation occurs exclusively on α.[6,8] ATP or dATP binding at the allosteric activity (A) site on α respectively stimulates or suppresses overall RNR enzymatic activity. dNTP/ATP binding at the allosteric specificity (S) site determines the substrate specificity of α.

Mounting evidence indicates that allosteric regulation is strongly coupled to nucleotide-induced oligomeric state changes that occur solely on hRNR α and do not require β.[8–14] The physiological relevance of such α oligomeric equilibria has also been demonstrated recently with the α-specific hexamerization-coupled inhibition induced by nucleotides of the antileukemic therapeutic clofarabine (ClF).[12] With dNTP/ATP natural allosteric effectors, some disagreement exists about whether higher-order oligomers can be assessed.[8–14] However, a large number of biochemical and structural reports have shown that the binding of the natural feedback allosteric inhibitor dATP at the A site induces α hexamerization of eukaryotic RNRs.[8–12,14] In addition, nucleotide effector binding at the S site is believed to prime α to initiate substrate selection through α dimerization.[6,8,10,11] The present study reports the development of the first readout directly reporting the two distinct hRNR-α oligomeric states. We applied this newly developed platform to monitor in real time hRNR-α hexamerization event triggered by the feedback regulator dATP (Figure 1).

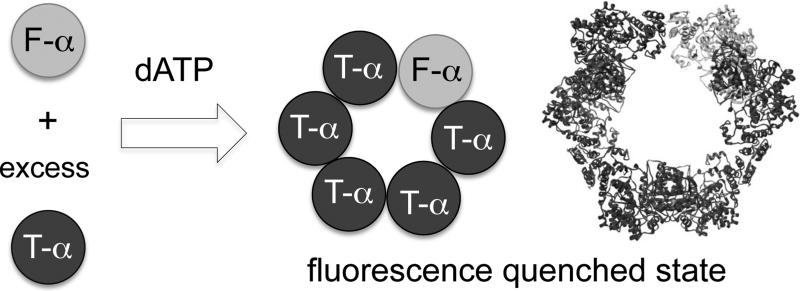

Figure 1.

A fluorescence readout directly reporting RNR-α hexamerization. Feedback inhibitor dATP binding at the A site induces assembly of α6 states in which the donor fluorescein signal is quenched. Gray and dark spheres are fluorescein (F)- and tetramethylrhodamine (T)-labeled α monomers. Hexamers with all T-α are omitted for clarity. The ribbon represents the known 6.6 Å crystal structure of dATP-bound α6 from S. cerevisiae (3PAW).

Results and Discussion

Fluorescence assay development

We first focused on dATP-induced hexamerization as a readout, initially investigating the quenching of intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence as a hexamerization reporter.[17] No fluorescence change was observed upon dATP-induced α oligomerization, presumably because of the large number of Trp residues (12) on α. We thus undertook identification of a robust fluorophore labeling method with minimal perturbation to α oligomerization. The functionality of hRNR-α depends on the presence of essential Cys residues in the reduced (free thiol) state.[4] Some of these residues reside on the solvent-exposed flexible C-terminal tail of α. hRNR-α is also highly sensitive to oxidation, and the oxidized protein is prone to precipitation. These features rendered incompatible a number of site-specific chemical- and mutagenesis-based labeling strategies that have been used successfully with the bacterial RNRs. For instance, we found that the prolonged reaction time and additives used in native chemical ligation[18] unavoidably led to protein precipitation.

Previous work showed that N-terminal hexa-histidine (His6)- tagged α hexamerizes in the presence of dATP or ClF di- and triphosphates [ClFD(T)P] in the same manner as the enzyme from which the His6 tag has been removed.[11,12] We thus anticipated that a fluorophore could be incorporated site-specifically using ATTO dyes[19] that bind to the His6 tag. However, because ATTO dye labeling of the His6 tag is noncovalent, we observed dye dissociation under dilute reaction conditions. We also attempted to use a Lap tag,[20] which can be enzymatically modified, inducing covalent labeling of the Lap-tagged protein. However, the N-terminal Lap-tagged-α failed to hexamerize upon treatment with hexamerization inducers. We also constructed and isolated catalytically functional α variants genetically encoded at the N-terminus with the commonly used protein tags, enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP),[21] monomeric red fluorescent protein (mRFP),[22] and HaloTag.[23] These fusion proteins also impeded hexamerization. Our labeling efforts highlighted the sensitivity of hRNR α hexamerization to N-terminal perturbations, an observation consistent with the fact that the N-terminus provides the physical dimer interface within the trimer of dimers (α2)3 [10,12].

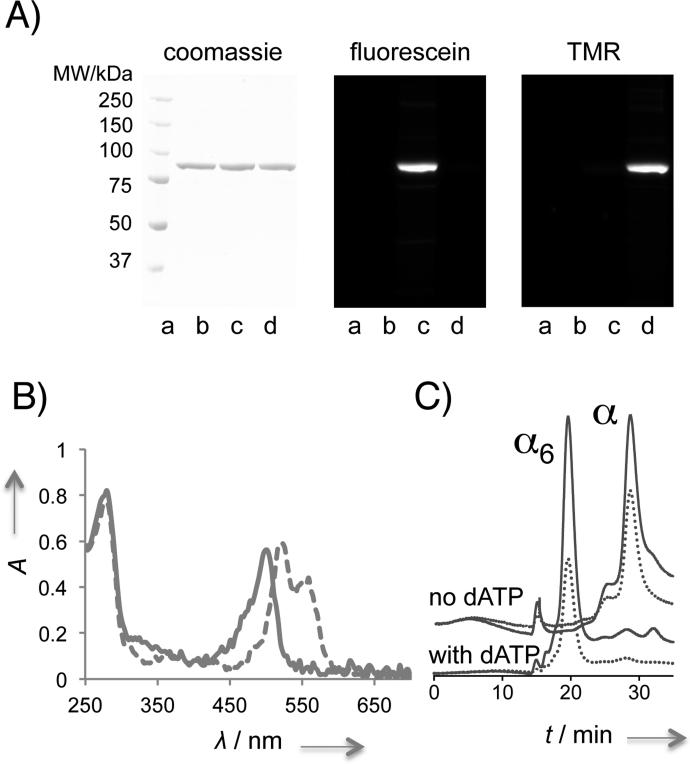

We ultimately identified a non-intrusive labeling strategy using small amounts of thiol-reactive dyes in the presence of the reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT). We hypothesized that the presence of the reducing agent provides a reaction environment in which DTT maintains the solubility and functional integrity— specifically, oligomerization capacity—of hRNR-α. A 20-min incubation with either 5-iodoacetamidofluorescein (5-IAF), or tetramethylrhodamine-5-iodoacetamide dihydroiodide (5-TMRIA), resulted in 1.0 ± 0.2 and 0.9 ± 0.1 equiv, respectively, of covalent fluorophore labeling per polypeptide (Figure 2A–B and Table S1). Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis suggested that, based on 66% peptide coverage, labeling occurred primarily on three solvent-exposed catalytically non-essential Cys residues: C254, C662 and C779 (Figure S1). Importantly, gel filtration analysis showed that both the fluorescein-labeled and the tetramethylrhodamine-labeled α (hereafter F- and T-α) hexamerized as efficiently as unlabeled α in the presence of 20 μM dATP in the running buffer (Figure 2C and S2). The activities of F- and T-α were not largely perturbed, maintaining, 72 ± 2% and 68 ± 8%, respectively, of the activity of unlabeled α treated under otherwise identical conditions (Figure S3A). The capability of the labeled α to undergo α hexamerization suggests that our covalent labeling strategy was noninvasive and therefore suitable for modeling the hexamerization pathway. However, the observed partial loss in activity of the labeled α means that the calculated rates of oligomerization may differ slightly from those of the unlabeled protein. We further validated the capacity of the labeled proteins to hexamerize using the known hexamerization inducers ClFD(T)P (Figure S2).

Figure 2.

The covalent fluorophore labeling strategy is non-intrusive to α oligomerization. A) In-gel fluorescence analysis using denaturing SDS-PAGE validates covalent fluorophore labeling. Lane a–d, ladder, unlabeled-α treated under otherwise identical conditions, F-α, T-α. B) Absorbance spectra overlay of F-(—) and T-(---) α. See also Table S1 and Figure S1. Note: peak splitting is a common spectral feature of TMR-labeled proteins (see for example, manuals from life technologies, genaxxon, and anaspec.com). C) Labeled protein hexamerizes efficiently. Gel filtration analysis of F-α with and without dATP. — and ... designate A280 and A495 traces, respectively. See also Figure S2.

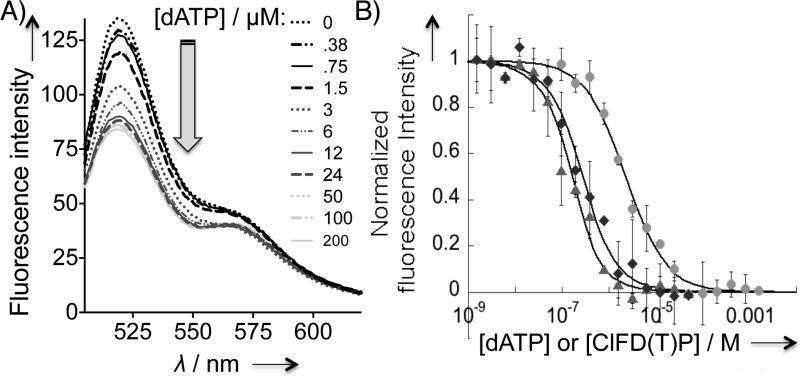

We then sought to identify the simplest and most reliable fluorimetric readout of α hexamerization. Fluorescent quenching in the presence of a 1:5 mixture of F-α (donor) and T-α (acceptor) was the most versatile and sensitive hexamerization reporter (Figure 1). Under these conditions, saturating concentrations of all three hexamerization-inducers—dATP, ClFD(T)P—caused 46–48 % drop in F intensity. Titration of dATP to the mixture revealed a dose-dependent signal drop (Figure 3 and S4A). The half maximal effective concentration (EC50) of the dATP-driven α hexamerization was calculated to be 2.3 ± 0.3 μM (Figure 3B). Similar titrations with ClFD(T)P showed that α hexamerization was inducible at a concentration much lower than that of dATP (Figure 3B). Because the minimum protein concentration for reliable fluorescence readout was ~180 nM, we fit the ClFD(T)P titration data to a tight-binding equation,[24] yielding Kd's instead of EC50. The resultant Kd values of ~185 ± 36 and 74 ± 19 nM, respectively, were within the range of the Kis deduced from inhibition assays.[11]

Figure 3.

Fluorescence quenching is coupled to wt-α hexamerization. A) Emission spectra of 1:5 F-:T-α (0.2 μM) with increasing dATP concentration (0–200 μM). B) Dose-dependent fluorescence quenching promoted by α hexamerization inducers: dATP (●), ClFDP (◆), and ClFTP (▲). Standard deviation was derived from N=3. Normalized intensity of 1.0 is set for the largest magnitude of drop in fluorescence intensity at the saturating concentrations of respective inducers and corresponds to a 46–48% drop in F intensity at 520 nm. See also Figure S4 and S5.

Importantly, nucleotides such as substrate CDP and the clinically used substrate analog suicide inactivator, gemcitabine diphosphate (F2CDP), which are incapable of altering the hRNR-α subunit quaternary structure,[9] did not induce appreciable fluorescence change (Figure S5A and S5B). Controls in which F-α alone or unlabeled α in place of T-α (Figure S5C–D) was treated with inducers showed a <1–3% drop in donor intensity. These observations suggest that no fluorescein quenching occurred due to nucleotide binding or interaction with protein residues.

To confirm that the observed quenching was due to a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) process, we subtracted the donor fluorescein intensities obtained from the samples with F-α alone from the emission spectra of an F- and T-α mixture at 0 and 200 μM dATP. An increase in T-α-specific intensity promoted by dATP was observed, indicating the presence of FRET (Figure S4B and S4C).

hRNR-α is monomeric in the absence of any substrates and effectors[8–14] and a wealth of evidence indicates that α alone can adopt a dimeric state. The α2 dimeric state is induced upon effector binding at the S site[6,8–14] and dimerization is a prerequisite for the adoption of the α2β2 active state by the holoenzyme.[25] The α2 quaternary state of hRNR-α (without β) has also been well-characterized by crystallography.[10] We were thus interested in the extent to which our fluorescence protocol could distinguish between α hexamerization and dimerization. We first took advantage of the previously characterized hRNR His6-D57N-α.[11] D57N-α is unresponsive to dATP-induced hexamerization-coupled inhibition. However, owing to dATP binding at the S site, this mutant is dimeric in saturating concentrations of dATP.[11,26] His6-D57N-α was covalently labeled with either F or T (Figure S6A), resulting in 0.9 ± 0.11 and 0.9 ± 0.3 equiv, respectively, of covalent dye labeling per polypeptide (Table S1 and Figure S6B). Gel filtration analysis in the presence of dATP in the running buffer showed that the labeled proteins dimerized with effiencies similar to that of the unlabeled mutant (Figure S2E and S2I). The specific activities of F- and T-D57N-α were 73 ± 8% and 61 ± 2% of the unlabeled D57N-α (Figure S3A).

Compared with the 46–48% drop in F intensity observed for dATP-induced wild type (wt)-α hexamerization, dATP promoted 37 ± 3 % quenching when wt-α was replaced with mutant-α under otherwise identical conditions. As a means for identifying a set of conditions in which the magnitudes of quenching resulting from dimerization and hexamerization are optimally different, the drop in the donor intensity at 520 nm was examined across various donor:acceptor ratios of F-:T-D57N-α (dimerization) and compared with the results obtained with F-:T-α (hexamerization) (Figure S3B). The results showed that the sensitivity of fluorimetry enabled the extent of quenching induced by α dimerization to be 10 ± 3 % lower than α hexamerization. Notably, the degree of donor quenching gradually declined as the proportion of T-α with respect to F-α decreased. This observation additionally corroborated the presence of FRET (Figure S4B and S4C). As the ratio of F-:T-α was increased beyond 1:1, the degree of quenching reached a plateau. A similar saturation effect has been reported in the previous FRET studies in which changes in the relative populations of donors to acceptors have little effect on FRET efficiency when the ratio of donor to acceptor is <1.[27]

The allosteric activator ATP is also thought to induce α oligomerization independent of β, although the precise nature of the resulting oligomeric state remains unsettled.[8-14] However, initial attempts to examine the effects of ATP using our new fluorescence assay revealed that high (millimolar) ATP nucleotide concentrations required to induce α oligomerization resulted in quenching of the fluorescein signal even in the sample containing only F-α alone, or even in the presence of 5-IAF dye alone without α. Thus, effects of ATP cannot be analyzed by this assay.

Stopped-flow fluorescence analyses

The successful development of a direct and sensitive fluorescence readout of the dATP inhibitor-induced α oligomerization gave us an impetus to study the kinetics of the dATP-driven hexamerization as a starting point. hRNR homo-oligomerization is an area of great pharmaceutical interest,[9–12] and its relevance has been biochemically proven with both the isolated enzyme[8–11,13–14] and the functional hRNR-α ectopically expressed in cells.[12] However, the mechanism and kinetics of the individual steps in the pathway remain unmapped in RNR from any species. The results of discontinuous inhibition assays and electron microscopy studies have inferred only an upper limit (3–4 min).[11,12]

In a FRET-based mixing assay using a fluorescence stopped-flow device, we first tested the conditions that permit only dimerization—namely, the dATP-induced D57N-α dimerization.[10, 26] Total fluorescence at wavelengths of >505 nm was monitored after the rapid mixing of a solution of 1:5 F-:T-D57N-α from one syringe and 200 μM dATP from another (Figure S7A). The process was surprisingly slow, requiring measurements longer than 180 s. The hyperbolic trace fit a second-order dimerization rate law:

where I(t), I0 and I∞ designate the fluorescence intensity at time t, time zero, and infinite time, respectively, and [α]0 is the initial concentration of D57N-α monomer (Figure S7A). The derivation of this equation is shown in the SI (page 8). Three lines of evidence further supported the second-order nature of the process. (1) The rate was dependent on protein concentration (Figure 4A): the apparent rate constant, kapp (i.e., 2[α]0k in Eq 1) was a linear function of [α]0 (Figure 4B). (2) Provided that dATP was present in saturating concentrations, changing dATP concentration had little or no effect on the rate (Figure S7B), implying that the dATP binding was rapid under these conditions. (3) A plot of the rate of total fluorescence intensity drop [dI(t)/dt] versus [I(t)]2 was also linear further confirming the second-order nature of the kinetic process (Figure 4C). The data revealed that D57N-α dimerization induced by dATP binding at the S site occurs with a bimolecular rate constant of (5.8 ± 0.2) × 104 M−1s−1. Although in our hands D57N-α was observed to be a dimer at 100 μM dATP,[11,12] high dATP concentrations have been implicated to induce further oligomerization of the mutant.[13] The biomolecular rate constant derived above was thus unambguiously verified by replicating the experiments at low dATP concentrations in which the mutant is undisputedly a dimer (Figure S8). The dimerization rate constants were found to be largely unaltered: [(5.0 ± 0.4) × 104] and [(5.9 ± 0.4) × 104] M−1s−1 at 20 and 33 μM dATP, respectively.

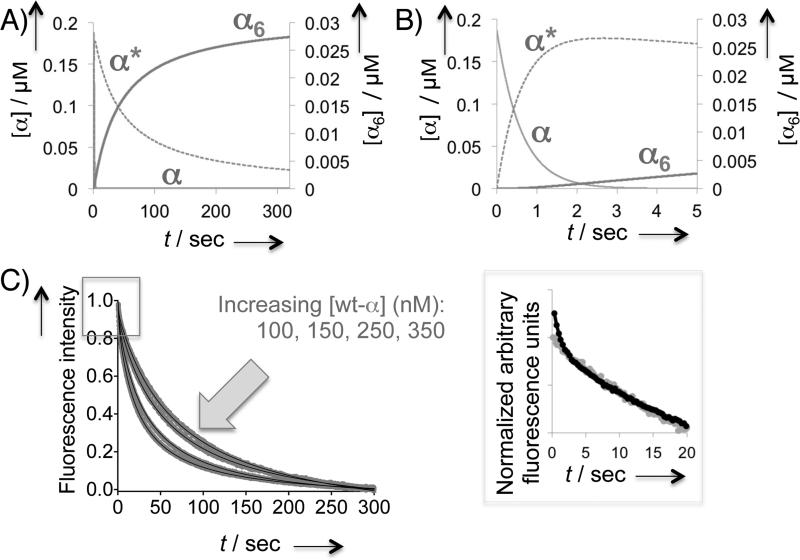

Figure 4.

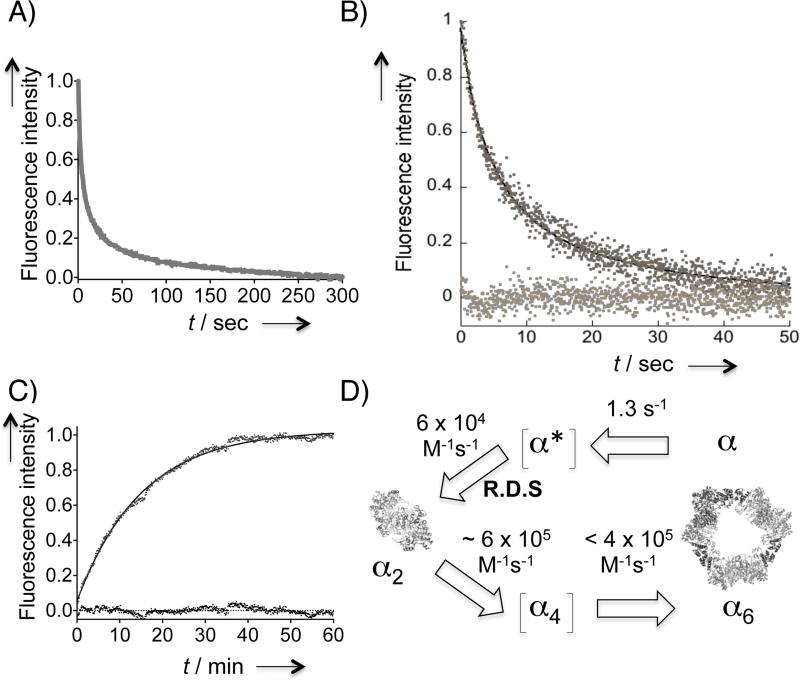

Stopped-flow fluorescence measurements of 100 μM dATP-induced α dimerization and hexamerization. Each trace is an average of ≥9 independent traces. A) D57N-α dimerization rate as a function of mutant protein concentration. Averaged kinetic traces from representative concentrations are shown. Solid lines indicate fit to Eq 1. (See also Figure S7 and S8). The observed kapp is linearly dependent on the mutant protein concentration. kapp = 2[α]0k in Eq 1. C) A plot of d[I(t)]/dt2 against [I(t)]2 overlaying the data from D57N- (gray) and wt- (dark) α. D) Kinetic trace for dATP-promoted wt-α hexamerization measured over 300 s (gray curve). The black dashed curve and baseline traces indicate fit to the data using Berkeley Madonna (Eq 2) and residuals, respectively. See also Figure 5.

We also probed whether the α dimerization rate is influenced by the identity of the nucleotide effector. We thus opted to exploit dGTP allosteric effector that binds exclusively at the S site and induces wt-α dimerization.[6,8–11] We first confirmed under steady-state conditions that the addition of saturating amounts of dGTP (0.1 mM) to a 1:5 mixture of F:T-wt-α promoted a 30–35% percentage drop in F-α intensity, a value within the range observed for dATP-induced D57N-α dimerization (Figure S9A). The subsequent stopped-flow monitoring of dGTP-induced wt-α dimerization revealed a kinetic trace that best fit the dimerization rate equation (Eq 1). The analysis provided a second order rate constant of (7.7 ± 0.6) × 104 M−1s−1 (Figure S9B). Although substrate specificity is conferred by specific effector binding at the S site—dGTP binding selecting ADP substrate and dATP binding selecting UDP substrate,[6,8–10] our data suggest that the two different effectors induced α dimerization at near identical rates.

We then probed α hexamerization with stopped-flow mixing of the wt protein and the feedback inhibitor dATP. The altered oligomeric state of mammalian α in the presence of the natural inhibitor dATP has been investigated using various biophysical methods.[8–14] Gel filtration,[10,11,14] dynamic light scattering[10,13] and gas-phase electrophoretic molecular mobility[14] analyses have collectively established that dATP binding to the A site drives mammalian RNR-α hexamerization. X-ray crystallography and electron microscopy data from 6.6 Å dATP-bound S. cerevisiae RNR-α hexamers[10] and ClF nucleotides-induced hRNR hexamers[12], respectively, have also provided structural insights into the inhibited complexes that adopt the trimer of dimers assembly. In the present study, we sought to construct the missing kinetic model of dATP-assisted eukaryotic RNR α hexamerization exemplified by the human enzyme.

D57N-α was thus replaced with wt-α under the stopped-flow conditions described above (Figure 4D). The resultant kinetic trace was identical to that obtained from the stopped-flow mixing of D57N-α and dATP, except in the early period, which featured an additional fast phase. Consistent with this observation, initially fitting of this trace to the dimerization equation showed a deviation from the fit within the <10 s period. Conversion of this kinetic trace to a plot of the rate of total fluorescence intensity drop (Figure 4C) revealed that unlike the trace obtrained for dATP-induced D57N-α dimerization, that of the dATP-induced wt-α hexamerization deviated clearly from linearity. The overall time course of dATP-induced wt-α hexamerization was best fit to a two-step kinetic model using the Berkeley Madonna program (v 8.3.18) (Figure 4D and 5, Eq 2.1–2.4). The fast phase fit well to a monoexponential rate law with a rate constant of 1.3 ± 0.2 s−1. Interestingly, the fitted second rate constant belonging to the slow phase of the FRET change in wt-α, (6.9 ± 0.6) × 104 M−1s−1, was very close to the dimerization rate constant for D57N-α determined above: (5.8 ± 0.2) × 104 M−1s−1. This unexpected finding suggested that the slow phase is associated with dimerization.

Figure 5.

Kinetics of 100 μM dATP-induced wt-α hexamerization. A) Kinetic simulation for the overall hexamerization process. B) Initial period of simulation in (A). Simulations were carried out with Madonna software (v 8.3.18): the rate constants were derived from fitting the averaged kinetic trace in Figure 4C to Eq 2.1–2.4. See also the Text and SI (page 9). Note that (α*)2 did not accumulate but was rapidly converted to α6 at a rate faster than that of rate-determining (α*)2 formation. The experimental kinetic trace (Figure 4D) and Eq 2.1–2.4 thus exclude information on the fast steps beyond the rate-determining step. C) Representative averaged kinetic traces at various wt-α concentrations. See also Table S2 and Figure S9. Inset on the right is the expansion of the initial period at [α] = 0.2 μM (dark trace) overlayed with the corresponding trace for D57N-α (0.2 μM) (gray trace) after normalization.

We used Eq 2.1–2.4 to model the observed kinetic trace to a two-step sequence: α→α*→(α*)2, in which α* was postulated to be α with an altered conformation. Steps subsequent to the rate-determining dimerization did not affect the kinetic trace or the derivation of Eq 2.4 (see also SI, page 9).

| (Eq 2.1) |

| (Eq 2.2) |

| (Eq 2.3) |

| (Eq 2.4) |

In Eq 2.1–2.4, α* represents an intermediate formed during the fast phase, (α*)2 is a dimer that can undergo further oligomerization at a rate(s) faster than that of (α*)2 formation, k1 and k2 are the rate constants of the two steps, I(t) and I0 designate the measured fluorescence intensity at time t and time zero, respectively, and U and V are constants. Figure 5A–B shows a kinetic simulation of this model using the Berkeley Madonna software. To test the hypothesis that α→α* conversion is associated with conformational transition, we evaluated the effects of various protein concentrations (Figure 5C). As expected, a large part of each of the resultant traces representing the rate-determining dimerization step was affected by protein concentration. Extraction of the rate constants (Table S2) by fitting the averaged traces at each α concentration to Eq 2.1–2.4 revealed that the fast phase preceding dimerization was a unimolecular process independent of protein concentration (Figure S10). By contrast, excluding the initial 10 s period from each trace and approximating the remaining part to dimerization (Eq 1) showed that the apparent rate constants for the slow step changed linearly as a function of α concentration (Figure S10).

These data unexpectedly revealed that α dimerization is the rate-determining step in dATP-promoted wt-α hexamerization, but subsequent faster step(s) were not revealed. The fast step relating to the proposed conformationally altered α* was notably absent in the wt-α dimerization triggered by the dGTP binding at the S site as well as in D57N-α dimerization in which dATP only associates with the S site under the given conditions. We thus posit that the rapid conformational transition of α to α* (<10 s) unique to wt-α is linked to dATP-binding at the A site, effectively giving rise to a dimer primed specifically to proceed ultimately to forming the hexameric (α6) state. As this priming step was absent in D57N-α with dATP and in wt-α with dGTP bound at the S site (Figure 4A–C, 5C inset, S7–9), dATP binding at the A site on wt-α likely enables allosteric adjustments through conformational transitioning at an early step that precedes dimerization.

The rate-determining nature of the dimerization limited our ability to obtain a readout of the kinetics of the remaining steps representing α2 → α6 transition. Because termolecular events in which the three α2 dimers simultaneously assemble into a hexamer are statistically improbable, the α4 state is a likely transient intermediate along this pathway. Since the rate constants of dGTP-induced wt-α dimerization and the dATP-induced D57N-α dimerization are similar, the dGTP-bound (wt-α)2 dimer is considered a reasonable dimeric precursor with a vacant A site to accept dATP, thereby proceeding along the α2 → α6 trajectory. Thus to approximate the kinetics of the α2 → α6 oligomeric transition, we performed stopped-flow mixing of one syringe containing wt-α pre-incubated with 0.1 mM dGTP and another containing 200 μM dATP (Figure 6A). Although the overall trace did not fit to simple rate laws, the initial period (~50 s) fit well to the second-order dimerization equation (Eq 1) (Figure 6B). This initial period presumably reports the biomolecular combination of α2 and α2 affording a tetrameric intermediate. Concentration-dependent studies (Figure S11) showed that the apparent rate constant, kapp (2[α2]0k in Eq 1) is linearly dependent of [α2], yielding a rate constant of (5.6 ± 0.2) × 105 M−1s−1. The fact that the rate constant for α2 → α6 conversion was an order of magnitude faster than that for the rate-determining dimerization (~ 6 × 104 M−1s−1) was in line with our expectations. These observations further reinforced the previous findings that the new fluorescence platform can differentiate the initial dimerization event from the subsequent formation of higher-order α oligomers.

Figure 6.

(A–C) Estimating the rates of α2 → α6 and α2 → α transitions in saturating dATP. A) Averaged kinetic trace (N = 9) resulting from mixing dATP and wt-α presaturated with dGTP at the S site. See also Figure S10A. B) The first 50 s of a representative kinetic trace from (A). Solid black line indicates the fit to Eq 1. The baseline trace indicates residuals. See also Figure S10B. C) Fluorescence recovery after 1:1 v/v mixing of 2 μM unlabelled D57N-α dimers (in 200 μM dATP) and 375 nM labeled D57N-α dimers (1:1 F:T-D57N-α in 200 μM dATP). The solid line shows monoexponential fit. Residuals are shown at the baseline. D) Oligomerization model in the presence of saturating dATP. The reverse process is considered negligible in the presence of saturating dATP and was 1.1 × 10−3 s−1 for α2 → α. Dimerization is the rate-determining step (R.D.S) and is estimated to be one order of magnitude slower than subsequent oligomerization steps. α* is the proposed conformationally altered transient state of α that can ultimately undergo α hexamerization process as described in the text. Tetrameric state is proposed as a transient intermediate because α2 trimerization directly to α6 in a single step is considered to be an unlikely event. Ribbon depictions for α2 and α6 are based on the known crystal structures of hRNR-α (2WGH) and yeast RNR-α (3PAW), respectively. Each α monomer is shown in dark and light gray, and the N-terminal domain housing the A site is in black. See Table of Contents figure for depiction in color.

Because of the known stability of the α2 and α6 states in the presence of appropriate effectors under saturating concentrations,[8–14] we were interested to probe the dissociation rate under the same experimental conditions, in addition to rate of association. As an initial step, the propensity of dimer decomplexation was examined using dATP-bound D57N-α dimers. Addition of a large excess of unlabeled D57N-α dimer to a sample containing labeled dimer resulted in a slow (~1 h) recovery of donor intensity at 520 nm (Figure 6C). Monoexponential fit to the data gave a first-order rate constant of (1.1 ± 0.2) × 10−3 s−1 for the subunit exchange process, which is equivalent to the dimer dissociation rate constant[28] in the presence of saturating concentrations of dATP. From α2 association and dissociation events, the dimer-monomer equilibrium constant in the presence of saturating concentrations of dATP was calculated to be 18 nM. In the absence of any nucleotide, the equilibrium constant for dimer-monomer transition has been repored to be 170 μM.[29]

Conclusions

We have developed a simple readout that can directly report hRNR-α oligomerization events with high sensitivity. The pre-steady-state kinetic analyses using this newly developed platform revealed: (1) hRNR oligomerization is a slow process; (2) dimerization is the unexpected rate-limiting step along dATP-induced hexamerization-coupled inhibition pathway (Figure 6D); (3) the rates of dimerization in response to nucleotide-binding at the allosteric specificity (S) site are similar for dGTP and dATP likely suggesting that substrate selection is not governed by kinetics but through the binding equilibrium; (4) the dissociation of dimer is very slow implying that the complex once formed is tight in the presence of saturating concentrations of dATP; and (5) kinetics of the subsequent steps beyond the rate-determining dimerization were estimated to be an order of magnitude faster. In this model, the reverse process is considered negligible in the presence of saturating concentrations of dATP.

dATP is the only endogenous ligand capable of downregulating RNR activity.[5,6,8,9,30] Thus feedback regulation is essential in maintaining dNTP pools at appropriate levels and sustaining DNA replication fidelity.[9,30] Our initial data provide a starting point for understanding oligomeric regulatory kinetics in response to an important feedback inhibitor. Analogous measurements of ClFD(T)P-induced α hexamerization are the subjects of future studies. Our fluorimetric platform also paves the way toward rapid identification of non-nucleotide-based small molecules that can bind and promote self-assembly of α. Such molecules may have the potential to inhibit hRNR.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Peng Chen for scientific discussions, Professor JoAnne Stubbe for scientific feedback, and the laboratories of Professors Peng Chen, Steven E. Ealick, and Hening Lin for the use of the fluorimeter, inert atmosphere chamber, and LCMS instrument, respectively. We thank Professor Charles Richardson (Harvard Medical School) for the plasmid encoding E. coli TrxA. We acknowledge Dr. Sheng Zhang and the staff of the proteomics and mass spectrometry facility at Cornell for LC-MS/MS technical support, and the protein production facility at Cornell for the use of the stopped-flow spectrofluorimeter. ESR data were collected at the ACERT and supported by NIH/NIGMS Grant P41GM103721 [at Cornell University, Professor Jack Freed (PI); we thank Dr. Boris Dzikovski for his assistance]. This research was supported by a Hill Undergraduate Research Fellowship (to W.B), a King Bhumibol Adulyadej Graduate Fellowship (to S.W.), and the Cornell University junior faculty start-up funds, the Milstein Sesquicentennial Fellowship, the Affinito-Stewart grant from the President's Council of Cornell Women and a faculty development grant from the ACCEL program supported by NSF [SBE-0547373, Kent Fuchs (PI)] (to Y.A).

Footnotes

Experimental Section

See the supporting information for complete experimental methods. Table S1–S2 and Figures S1–S11.

References

- 1.Freeman M. Nature. 2000;408:313. doi: 10.1038/35042500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sneppen K, Krishna S, Semsey S. Annu Rev Biophys. 2010;39:43. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.093008.131241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Csete M, Doyle J. Trends Biotech. 2004;22:446. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stubbe J, van der Donk W. Chem Rev. 2008;98:705. doi: 10.1021/cr9400875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thelander L. Nat Gen. 2007;39:703. doi: 10.1038/ng0607-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nordlund P, Reichard P. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:681. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shao J, Zhou B, Chu B, Yen Y. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2006;6:409. doi: 10.2174/156800906777723949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hofer A, Crona M, Logan DT, Sjoberg BM. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;47:50. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2011.630372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aye Y, Li M, Long MJC, Weiss RS. Oncogene. 2014 doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.155. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fairman JW, Wijerathna SR, Ahmad MF, Xu H, Nakano R, Jha S, Prendergast J, Welin RM, Flodin S, Roos A, Nordlund P, Li Z, Walz T, Dealwis CG. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:316. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aye Y, Stubbe J. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013274108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aye Y, Brignole Edward J., Long Marcus J. C., Chittuluru J, Drennan Catherine L., Asturias Francisco J., Stubbe J. Chem Biol. 2012;19:799. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kashlan OB, Cooperman BS. Biochemistry. 2003;42:1696. doi: 10.1021/bi020634d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rofougaran R, Vodnala M, Hofer A. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:27705. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonate PL, Arthaud L, Cantrell WR, Jr., Stephenson K, Secrist JA, 3rd, Weitman S. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:855. doi: 10.1038/nrd2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hertel LW, Boder GB, Kroin JS, Rinzel SM, Poore GA, Todd GC, Grindey GB. Cancer Res. 1990;50:4417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lakowicz JR. Principles of fluorescence spectroscopy. 3rd Ed. Springer; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson ECB, Kent SBH. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128:6640. doi: 10.1021/ja058344i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guignet EG, Hovius R, Vogel H. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:440. doi: 10.1038/nbt954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uttamapinant C, Sanchez MI, Liu DS, Yao JZ, Ting AY. Nature Protocols. 2013;8:1620. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsien RY. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:509. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell RE, Tour O, Palmer AE, Steinbach PA, Baird GS, Zacharias DA, Tsien RY. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082243699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Los GV, Encell LP, McDougall MG, Hartzell DD, Karassina N, Zimprich C, Wood MG, Learish R, Ohana RF, Urh M, Simpson D, Mendez J, Zimmerman K, Otto P, Vidugiris G, Zhu J, Darzins A, Klaubert DH, Bulleit RF, Wood KV. ACS Chem Biol. 2008;3:373. doi: 10.1021/cb800025k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuzmic P, Sideris S, Cregar LM, Elrod KC, Rice KD, Janc JW. Anal Biochem. 2000;281:62. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minnihan EC, Ando N, Brignole EJ, Olshansky L, Chittuluru J, Asturias FJ, Drennan CL, Nocera DG, Stubbe J. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:3835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220691110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu Y, Long MJ, Rigney M, Parvez S, Blessing WA, Aye Y. Biochemistry. 2013;52:7050. doi: 10.1021/bi400781z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berney C, Danuser G. Biophysical Journal. 2003;84:3992. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75126-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan C. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28827. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott CP, Kashlan OB, Cooperman BS. Biochemistry. 2001;40:1651. doi: 10.1021/bi002335z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou BB, Elledge SJ. Nature. 2000;408:433. doi: 10.1038/35044005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.