ABSTRACT

The core human gut microbiota contributes to the developmental origin of diseases by modifying metabolic pathways. To evaluate the predominant microbiota as an epigenetic modifier, we classified 8 pregnant women into two groups based on their dominant microbiota, i.e., Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria. Deep sequencing of DNA methylomes revealed a clear association between bacterial predominance and epigenetic profiles. The genes with differentially methylated promoters in the group in which Firmicutes was dominant were linked to risk of disease, predominantly to cardiovascular disease and specifically to lipid metabolism, obesity, and the inflammatory response. This is one of the first studies that highlights the association of the predominant bacterial phyla in the gut with methylation patterns. Further longitudinal and in-depth studies targeting individual microbial species or metabolites are recommended to give us a deeper insight into the molecular mechanism of such epigenetic modifications.

IMPORTANCE

Epigenetics encompasses genomic modifications that are due to environmental factors and do not affect the nucleotide sequence. The gut microbiota has an important role in human metabolism and could be a significant environmental factor affecting our epigenome. To investigate the association of gut microbiota with epigenetic changes, we assessed pregnant women and selected the participants based on their predominant gut microbiota for a study on their postpartum methylation profile. Intriguingly, we found that blood DNA methylation patterns were associated with gut microbiota profiles. The gut microbiota profiles, with either Firmicutes or Bacteroidetes as a dominant group, correlated with differential methylation status of gene promoters functionally associated with cardiovascular diseases. Furthermore, differential methylation of gene promoters linked to lipid metabolism and obesity was observed. For the first time, we report here a position of the predominant gut microbiota in epigenetic profiling, suggesting one potential mechanism in obesity with comorbidities, if proven in further in-depth studies.

Observation

The human gut microbiota is mainly composed of the phyla Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteria, with other phyla, such as Proteobacteria, as a smaller but important component. Small shifts in microbial composition may modify energy intake in a way that leads to weight gain and, later, to insulin insensitivity. For instance, the abundances of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes can be highly biased in cases of obesity (1), diabetes (2), and cardiovascular risk factors (3). The molecular mechanism controlling these metabolic alterations has been related to effects on glucose absorption, generation of fatty acids, hepatic lipogenesis, and deposition of triglycerides in adipocytes (4).

We hypothesized that host-microbe interaction during the critical and sensitive period of pregnancy may determine the risk of developing obesity with comorbidities. Recent reports suggest that the microbiota and its metabolites influence genomic reprogramming (5–7). For example, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Eubacterium rectale/Roseburia spp., which belong to the Firmicutes, are major contributors of butyrate, which regulates gene expression by histone modifications (5). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is another microbial factor that may have a significant role in the epigenetic regulation of immune and intestinal cells (8). LPS, widely recognized as an inflammatory molecule, acts as risk factor for cardiovascular diseases (9). There are various molecules of microbial origin that are in complex interplay with host metabolism and physiology. However, to our knowledge, there are no studies in human subjects that have correlated the microbiota and epigenetic modifications. As a first step, we compared the fecal microbiota composition to blood DNA methylation patterns in 8 subjects (body mass index of ≤25).

Previously, we have shown that microbiota alteration during pregnancy has a significant impact on host metabolism (10). Analysis of the fecal microbiota at different stages of pregnancy indicated that the bacterial diversity in the first trimester of pregnancy is similar to that of normal nonpregnant individuals (10). In the present study, we have identified an association that suggests a role of the predominant microbiota in epigenomic regulation. Thus, the following questions were asked: is the abundance of Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and/or Proteobacteria associated with differences in methylation pattern, and what are the major pathways associated epigenetically with patterns of microbial community structure?

Selection of subjects.

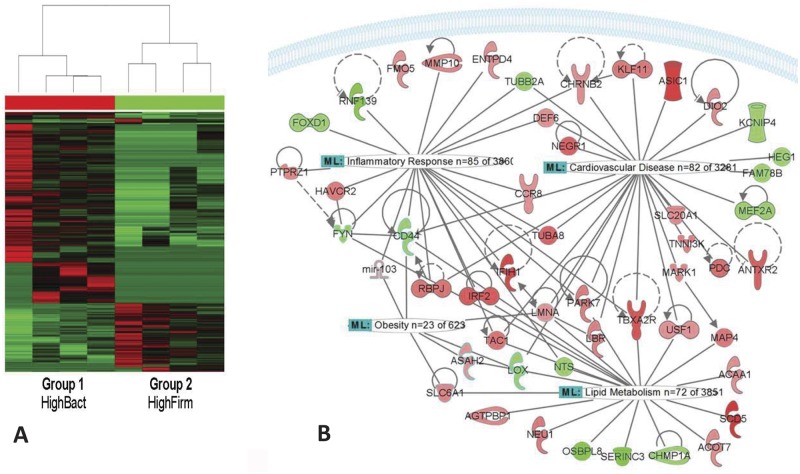

Eight pregnant women were selected from a cohort of 91 subjects previously described elsewhere (10). We selected mothers based on the relative abundances of the predominant phyla as previously reported (10). The HighBact group (n = 4) exhibited a predominance of the Bacteroidetes (P = 0.017) and Proteobacteria (P = 0.013) phyla, whereas Firmicutes were predominant in the HighFirm group (n = 4) mothers (P = 0.020) (Fig. 1). Previously, it has been shown that Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes constitute the dominant core of gut microbiota, and a Firmicutes-dominant microbiota has been implicated in the development of overweight, obesity, and metabolic syndrome (11–13). Additionally, the dietary and health characteristics of selected mothers in each group were similar, i.e., statistically insignificant (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG 1 .

Categorization of mothers into group HighBact and group HighFirm was based on their dominant bacterial phyla. Box plots show the relative abundance (%) of the three major bacterial phyla, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria. There is a statistically significant difference between the groups (P < 0.05) using t test analysis.

Correlation between DNA methylation profile and microbiota composition.

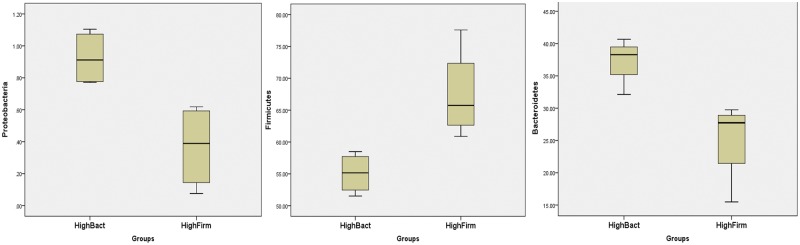

The two groups showed distinct methylation profiles (blood samples were collected 6 months after delivery), as illustrated by the clustering analysis in Fig. 2A. With a fold change cutoff of 1.5 and P value of 0.05, the promoters of a total of 568 genes were more methylated and the promoter of 245 genes were less methylated in mothers with higher levels of Firmicutes (HighFirm group) than in mothers with higher levels of Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria (HighBact group) (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

FIG 2 .

Association of gut microbiota with DNA methylation. (A) Clustering analysis of DNA methylome data revealed a clear correlation between the whole-blood epigenetic profile and the composition of the gut microbial population of the mothers with a predominance of either Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria (group HighBact) or Firmicutes (group HighFirm). Green indicates decreased and red indicates increased gene promoter methylation in group HighFirm compared to the promoter methylation in group HighBact. (B) Based on Pathway Analysis (Ingenuity Systems), the gut microbial composition affects the DNA methylation status of genes primarily linked to cardiac diseases, with associations to lipid metabolism, inflammatory response, and obesity. The affected genes linked to the particular functional or metabolic syndrome displayed in the network had fold changes of ≥3 in the promoter DNA methylation status between the HighBact group and the HighFirm group. The symbols and their colors are defined in Table S4 in the supplemental material.

Gut microbiota composition associates with promoter DNA methylation status of genes associated with lipid metabolism, obesity, and inflammation.

Pathway analysis revealed that the most significant functional network altered in the HighBact group was linked to cardiovascular diseases, together with gene expression and cell morphology functions (score of 43; Fisher exact test, P = 1 × 10−43) (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). In addition, differentially methylated genes were enriched in other functional networks, including the inflammatory response, metabolic pathways, and diseases like cancer, mostly affecting the gastrointestinal system (312 molecules, P < 0.05). As the Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratio was associated with obesity-related comorbidities, the cardiovascular disease risk network was further expanded, and associations with lipid metabolism (72 genes), inflammatory response (85 altered genes), and obesity (23 altered genes) were found (Fig. 2B). Consistent with these results, the gene SCD5, which had the greatest difference between the two groups (fold change, 6.239; P = 0.00005), encodes primate-specific stearoyl-coenzyme A (CoA) desaturase, which has a key function in the catalysis of monounsaturated fatty acids from saturated fatty acids. The promoter region of SCD5 was more methylated in the HighFirm group and had an undetectable methylation in the HighBact group. LPS (P = 0.00208) was one of the upstream regulators of genes identified in the network (see Table S3), which further strengthens the role of microbial molecules in epigenetic modifications.

Some of the epigenetically regulated genes include the genes encoding USF1 (P = 0.00805), ACOT7 (P = 0.035), ASAH2 (P = 0.0367), TAC1 (P = 0.00972), and LMNA (P = 0.03081). USF1 is one of the key regulators of fatty acid synthase (FAS) and is also a key enzyme in lipogenesis (14). USF1 and LMNA have also been linked with the onset of coronary heart disease (15, 16). The expression of ACOT and microRNAs 103/107 was also found to be upregulated in obese rats and mice, respectively (17, 18). Similarly, gut microbiota or its metabolites are directly linked to obesity and associated metabolic pathways. However, the association with epigenetic regulation of these genes should be further confirmed by quantitative PCR (qPCR) and in vitro experiments.

These findings are consistent with previous studies, which have linked higher levels of Firmicutes to the development of overweight, obesity, higher energy extraction, and metabolic functions, including lipid metabolism. Additionally, deviant gut microbiota composition could also be one of the risk factors which may contribute to metabolic syndrome. Our findings are novel, but due to the small sample size, larger studies and interventions, and possibly animal experiments also, are required to assess the mechanisms. Nonetheless, this approach is intriguing and could offer a new basis for prevention and treatment strategies involving the gut microbiota and its impact on long-term genomic modifications.

Microbial phylum comparisons.

All the OTU tables were retrieved from our earlier study (10).The percentages of relative abundance for all phyla were used to compare the mothers (divided into two groups). Statistical package SPSS was used for the t test and to make box plots of the percentages of relative abundance.

DNA methylome analysis.

The DNA methylome analysis was carried out from 5 µg of genomic DNA that was extracted from EDTA blood with a QIAamp DNA blood maxikit (Qiagen) and fragmented into an average size of 150 bp with a Covaris S2 sonicator. Methylated DNA was enriched with a MethylMiner methylated DNA enrichment kit (Invitrogen) by following the high-salt (2 M NaCl), single-elution workflow. The sequencing libraries were prepared from 500 ng of enriched DNA with a SOLiD fragment library construction kit (Life Technologies), and the SOLiD fragment library barcoding kit module 1-16 (Life Technologies) was used for multiplexing. The libraries were purified (AMPure XP beads; Agencourt) and size selected (150 to 300 bp) from 1% agarose gels (QIAquick gel extraction kit; Qiagen). The bead preparation was carried out according to the SOLiD 4 System Templated Bead Preparation Guide. The SOLiDEZ bead system was used for automated templated bead preparation. The libraries were sequenced with a SOLiD 4 or SOLiD 5500XL sequencer (Life Technologies) by using 50-bp chemistry.

Methylation sequencing data analysis.

The raw sequence data were mapped to hg19 reference genome sequences with Life Technologies Bioscope (version 2.0) software using the default parameters, yielding on average 56.7 M mapped reads per sample (standard deviation, 14.26 M reads). The read counts for proximal promoters (region between 1,000 bp upstream and 500 bp downstream from the transcription start site, coordinates derived from RefSeq gene annotations) were calculated using bedtools (version 2.17.0). Statistical analysis for comparing differentially methylated promoters between sample groups was carried out using R/Bioconductor limma package on TMM-normalized and voom-transformed count values as suggested in the limma manual (19, 20). The promoters with absolute fold changes above 2 and P values below 0.05 were listed as significantly differentially methylated.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Diet and health characteristics of mothers divided into two groups, HighBact and HighFirm. Statistical analysis was carried out using the Mann-Whitney U test in the SPSS package.

Differentially methylated promoters compared between two groups of mothers, HighBact and HighFirm.

Upstream regulators of the differentially methylated genes shown in Fig. 2B

Key to molecule shapes and colors in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Omry Koren for useful discussion on data analysis. We also thank the hospital nurses for their help in collecting the samples.

This research project was funded by the Academy of Finland.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Citation Kumar H, Lund R, Laiho A, Lundelin K, Ley RE, Isolauri E, Salminen S. 2014. Gut microbiota as an epigenetic regulator: pilot study based on whole-genome methylation analysis. mBio 5(6):e02113-14. doi:10.1128/mBio.02113-14.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. 2006. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature 444:1022–1023. 10.1038/4441022a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sasaki M, Ogasawara N, Funaki Y, Mizuno M, Iida A, Goto C, Koikeda S, Kasugai K, Joh T. 2013. Transglucosidase improves the gut microbiota profile of type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled study. BMC Gastroenterol. 13:81. 10.1186/1471-230X-13-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Manco M, Putignani L, Bottazzo GF. 2010. Gut microbiota, lipopolysaccharides, and innate immunity in the pathogenesis of obesity and cardiovascular risk. Endocr. Rev. 31:817–844. 10.1210/er.2009-0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Caesar R, Fåk F, Bäckhed F. 2010. Effects of gut microbiota on obesity and atherosclerosis via modulation of inflammation and lipid metabolism. J. Intern. Med. 268:320–328. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Berni Canani R, Di Costanzo M, Leone L. 2012. The epigenetic effects of butyrate: potential therapeutic implications for clinical practice. Clin. Epigenetics 4:4. 10.1186/1868-7083-4-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Minarovits J. 2009. Microbe-induced epigenetic alterations in host cells: the coming era of patho-epigenetics of microbial infections. A review. Acta. Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 56:1–19. 10.1556/AMicr.56.2009.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shenderov BA. 2012. Gut indigenous microbiota epigenetics. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2012:23. 10.3402/mehd.v23i0.17195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Angrisano T, Pero R, Peluso S, Keller S, Sacchetti S, Bruni CB, Chiariotti L, Lembo F. 2010. LPS-induced IL-8 activation in human intestinal epithelial cells is accompanied by specific histone H3 acetylation and methylation changes. BMC Microbiol. 10:172. 10.1186/1471-2180-10-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Després JP. 2012. Abdominal obesity and cardiovascular disease: is inflammation the missing link? Can. J. Cardiol. 28:642–652. 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koren O, Goodrich JK, Cullender TC, Spor A, Laitinen K, Bäckhed HK, Gonzalez A, Werner JJ, Angenent LT, Knight R, Bäckhed F, Isolauri E, Salminen S, Ley RE. 2012. Host remodeling of the gut microbiome and metabolic changes during pregnancy. Cell 150:470–480. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mahowald MA, Rey FE, Seedorf H, Turnbaugh PJ, Fulton RS, Wollam A, Shah N, Wang C, Magrini V, Wilson RK, Cantarel BL, Coutinho PM, Henrissat B, Crock LW, Russell A, Verberkmoes NC, Hettich RL, Gordon JI. 2009. Characterizing a model human gut microbiota composed of members of its two dominant bacterial phyla. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:5859–5864. 10.1073/pnas.0901529106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ley RE, Bäckhed F, Turnbaugh P, Lozupone CA, Knight RD, Gordon JI. 2005. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:11070–11075. 10.1073/pnas.0504978102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tap J, Mondot S, Levenez F, Pelletier E, Caron C, Furet JP, Ugarte E, Muñoz-Tamayo R, Paslier DL, Nalin R, Dore J, Leclerc M. 2009. Towards the human intestinal microbiota phylogenetic core. Environ. Microbiol. 11:2574–2584. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Putt W, Palmen J, Nicaud V, Tregouet DA, Tahri-Daizadeh N, Flavell DM, Humphries SE, Talmud PJ, EARSII Group 2004. Variation in USF1 shows haplotype effects, gene: gene and gene: environment associations with glucose and lipid parameters in the European Atherosclerosis Research Study II. Hum. Mol. Genet. 13:1587–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pajukanta P, Lilja HE, Sinsheimer JS, Cantor RM, Lusis AJ, Gentile M, Duan XJ, Soro-Paavonen A, Naukkarinen J, Saarela J, Laakso M, Ehnholm C, Taskinen MR, Peltonen L. 2004. Familial combined hyperlipidemia is associated with upstream transcription factor 1 (USF1). Nat. Genet. 36:371–376. 10.1038/ng1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Worman HJ, Bonne G. 2007. “Laminopathies”: a wide spectrum of human diseases. Exp. Cell Res. 313:2121–2133. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fujita M, Momose A, Ohtomo T, Nishinosono A, Tanonaka K, Toyoda H, Morikawa M, Yamada J. 2011. Upregulation of fatty acyl-CoA thioesterases in the heart and skeletal muscle of rats fed a high-fat diet. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 34:87–91. 10.1248/bpb.34.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Trajkovski M, Hausser J, Soutschek J, Bhat B, Akin A, Zavolan M, Heim MH, Stoffel M. 2011. MicroRNAs 103 and 107 regulate insulin sensitivity. Nature 474:649–653. 10.1038/nature10112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, Hornik K, Hothorn T, Huber W, Iacus S, Irizarry R, Leisch F, Li C, Maechler M, Rossini AJ, Sawitzki G, Smith C, Smyth G, Tierney L, Yang JY, Zhang J. 2004. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 5:R80. 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Core, R Team. 2005. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Diet and health characteristics of mothers divided into two groups, HighBact and HighFirm. Statistical analysis was carried out using the Mann-Whitney U test in the SPSS package.

Differentially methylated promoters compared between two groups of mothers, HighBact and HighFirm.

Upstream regulators of the differentially methylated genes shown in Fig. 2B

Key to molecule shapes and colors in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis.