Abstract

Objective

To compare the efficacy of leuprolide and continuous oral contraceptives in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain.

Design

Prospective, randomized, double-blind controlled trial.

Setting

Academic medical centers in Rochester, New York, and Boston, Massachusetts.

Patient(s)

Forty-seven women with endometriosis-associated pelvic pain.

Intervention(s)

Forty-eight weeks of either depot leuprolide, 11.25 mg IM every 12 weeks with hormonal add-back using norethindrone acetate 5 mg orally, daily; or a generic monophasic oral contraceptive (1 mg norethindrone + 35 mg ethinyl estradiol) given daily.

Main Outcome Measure(s)

Biberoglu and Behrman (B&B) pain scores, numerical rating scores (NRS), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and Index of Sexual Satisfaction (ISS).

Result(s)

Based on enrollment of 47 women randomized to continuous oral contraceptives and to leuprolide, there were statistically significant declines in B&B, NRS, and BDI scores from baseline in both groups. There were no significant differences, however, in the extent of reduction in these measures between the groups.

Conclusion(s)

Leuprolide and continuous oral contraceptives appear to be equally effective in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pelvic pain. (Fertil Steril 2011;95:1568–73. 2011 by American Society for Reproductive Medicine.)

Keywords: Endometriosis, pelvic pain, GnRH agonists, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist, oral contraceptives, randomized controlled trial

Chronic pelvic pain is a common and significant affliction of women, with an estimated lifetime prevalence of 33%–39% and a point prevalence of 12% (1, 2). This syndrome accounts for approximately 10% of outpatient gynecologic evaluations, one-third of gynecologic laparoscopies, and up to 12% of hysterectomies (3).

Among women with chronic pelvic pain, approximately one-third have endometriosis (4). Endometriosis-associated pelvic pain can be treated medically or surgically. Conservative surgical treatment is typically associated with significant reduction in pain on a short-term basis. However, 50% of patients report recurrence of pain by 12 months postoperatively (5). A variety of medical regimens, including danazol, progestins, and GnRH analogs, have been shown to be effective in suppressing endometriosis-associated pelvic pain when treatment is continued for 6 months (6–8). After discontinuation of medication, however, pain scores return toward baseline levels (6–8). These drugs have generally not been studied for more than 6 months owing to side effects, complexity, or cost.

Currently, the only treatment for endometriosis-associated chronic pelvic pain approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for greater than 6 months is a combination of IM leuprolide acetate (LA; a GnRH analog) and oral norethin-drone acetate (NA) for up to 12 months (9). However, such treatment requires periodic injections plus a daily pill and is quite costly.

As an alternative to GnRH analogs, the use of cyclic oral contraceptives (OCs) has been advocated as a practical, inexpensive strategy for long-term medical treatment of endometriosis-associated pain. Although such an approach has a number of advantages, including safety of long-term use, simplicity, and cost, there are limited data regarding its efficacy (10, 11). Continuous use of OCs has the additional potential advantages of reduced dysmenorrhea and reduced reseeding of endometriosis.

In view of theses considerations, we performed a randomized, double-blind trial of continuous OCs versus leuprolide/norethin-drone in the treatment of women with endometriosis-associated pelvic pain. We hypothesized that over a 12-month period of treatment, both treatments would result in a significant reduction in pain but that there would be no difference between the two treatments in the extent of pain reduction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Overview

The research design was a prospective double-blind, randomized clinical trial. Women were recruited from gynecologic practices associated with the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, New York, and Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 1. Eligible women who provided informed consent were randomized to receive either 48 weeks of a generic monophasic OC (1 mg norethindrone + 35 μg ethinyl estradiol) given daily or 48 weeks of depot leuprolide, 11.25 mg IM every 12 weeks with hormonal add-back using NA 5 mg orally daily. Each participant received one injection every 12 weeks (depot leuprolide or saline with an inert powder suspension formulated to look alike) and also received tablets to take daily (NA or OC, each made into a powder and placed in an identical capsule). Medication began at the onset of the first menstrual period after enrollment. Baseline measures of pain and quality of life, described below, were obtained before beginning treatment and were repeated at 12-week intervals through week 48.

TABLE 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Criteria |

|---|

| Inclusion |

| Age greater than 18 and premenopausal. |

| Pelvic pain of at least 3 months’ duration. |

| Diagnosis of endometriosis by laparoscopy or laparotomy within 3 years of entry. The diagnosis of endometriosis will require either histology consistent with endometriosis or operative records indicating visual evidence of lesions consistent with endometriosis. |

| Moderate to severe pelvic pain attributable to endometriosis (average NRS40 of 5 or more for 3 or more months). |

| Willingness to comply with visit schedule and protocol. |

| Exclusion |

| Use of OCs within 1 month of enrollment. |

| Dose of leuprolide within 3 months if given monthly or within 5 months if given 3-month injection. |

| Any disorder that represents a contraindication to the use of OCs (e.g., insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, history of thrombophlebitis, hypertension, history of cardiovascular disease, smoker at 35 or more years of age) or GnRH analogs (e.g., history of osteopenia). |

| History ofhysterectomyand bilateral salpingo-ophorectomy. |

| Pregnancy or breastfeeding. |

| Significant mental or chronic systemic illness that might confound pain assessment or the inability to complete the study. |

Study Population, Recruitment, and Informed Consent

The principal investigators (PIs) at each site (Rochester, DSG; Boston, MDH) were directly involved with recruitment from referral practices. In Rochester, the study was presented by the PI to faculty in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and to four private practice obstetrics and gynecology groups. In Boston, participants were recruited from the Center for Reproductive Medicine at Brigham and Women's Hospital and from radio and print advertisements. Eligible and interested participants attended an intake visit, at which informed consent was obtained. The study was approved by the Research Subjects Review Board of the University of Rochester and the Human Research Committee of Partners Healthcare.

Pain and Quality-of-Life Assessments

Pain intensity, quality of life, and psychosocial functioning were assessed initially at the intake visit after informed consent had been obtained. These three domains captured the multidimensional nature of the experience of chronic pain (12) and provided data especially relevant to the evaluation of pain in women (13). The specific instruments described below were administered on the intake visit before treatment and at 12, 24, 36, and 48 weeks after commencement of treatment. In Rochester, all visits occurred in the General Clinical Research Center. In Boston, all visits took place at the Center for Reproductive Medicine of Brigham and Women's Hospital.

Biberoglu and Behrman patient ratings (B&B pain score) (14)

This instrument, widely used in many treatment studies of endometriosis-associated pain, assesses dyspareunia, dysmennorrhea, and noncyclic pelvic pain. It is a 0–9 scale, with 0–3 points assigned for each type of pain.

Numerical Rating Scale (NRS pain score) (15)

This is a 0–10 scale that measures the participant's range of pain levels independent of the menstrual cycle or intercourse. In a structured daily diary, participants recorded NRS ratings of their global pain each day.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (16)

This is a 21-item self-report instrument that provides a rapid assessment of depressive symptoms. It has been used in a large number of studies of chronic pain, including chronic pelvic pain (17, 18).

Index of Sexual Satisfaction (ISS) (19)

This is a 25-item measure of self-reported satisfaction with the sexual aspects of an intimate relationship. Since dyspareunia is nearly always present with chronic pelvic pain, sexual satisfaction is an important outcome variable.

Data Processing and Analysis

Data forms for de-identified data were developed by the Department of Biostatistics at the University of Rochester. Forms from both clinical units were transferred to the Department of Biostatistics as soon as they were completed and tracked on a log system. Data were entered, using double entry validation, onto an SAS database with a password-protected account.

The main hypothesis was assessed by comparing B&B and NRS scores for each treatment group across time and by comparing the change in these scores across time between the two treatment groups. Linear mixed models were fitted for each treatment with a categorical time variable to assess the change in pain scores over time. In addition, a linear mixed model was run for all data with both the treatment variable and time to assess their effects simultaneously. This analysis used repeated measurements on each subject at different time points, which were assumed to be correlated in the modeling process. Parameters were estimated by restricted maximum likelihood and generalized least squares using SAS (20). In addition to the two pain scores, similar analyses were performed on BDI and ISS.

RESULTS

Over the period 2005–2008, 47 women were recruited to the study protocol, 28 in Boston and 19 in Rochester. Of these 47 women, 26 were randomized to treatment with OCs and 21 to treatment with leuprolide. There were seven patients who dropped out immediately after the screening visit, three in the OC group and four in the NA group. Thus, baseline scores were available for 40 participants. There were no significant differences in any of the four baseline outcome measures between Rochester and Boston. For the purposes of hypothesis testing, data from Rochester and Boston were combined.

Demographic and baseline data are shown in Table 2. Based on χ2-tests for categorical variables and two-sample t-tests for mean age and baseline outcome measures, there were no differences in race, parity, marital status, or age between the two randomized treatment groups or between patients from the Rochester and Boston sites. There were no significant differences between treatment groups in baseline outcome measures, with the exception of ISS, with a P value of .0286.

TABLE 2.

Demographic characteristics and baseline measures.

| Rochester (n = 19) | Boston (n = 28) | Levlen/NS (n = 26) | Leuprolide/norethindrone (n = 21) | Total (n = 47) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race (%) | |||||

| White | 14 (29.79) | 21 (44.68) | 20 (42.55) | 15 (31.91) | 35 (74.47) |

| African American | 1 (2.13) | 2 (4.26) | 3 (6.38) | 0 | 3 (6.38) |

| Hispanic | 2 (4.26) | 5 (10.64) | 3 (6.38) | 4 (8.51) | 7 (14.89) |

| Other | 2 (4.26) | 0 | 0 | 2 (4.26) | 2 (4.26) |

| Parity (%) | |||||

| Nulliparous | 12 (25.53) | 22 (46.81) | 19 (40.43) | 15 (31.91) | 34 (72.34) |

| Parous | 7 (14.89) | 6 (12.77) | 7 (14.89) | 6 (12.77) | 13 (27.66) |

| Marital status (%) | |||||

| Married | 5 (10.64) | 10 (21.28) | 10 (21.28) | 5 (10.64) | 15 (31.91) |

| Single | 10 (21.28) | 13 (27.66) | 12 (25.53) | 11 (23.40) | 23 (48.94) |

| Divorced | 3 (6.38) | 5 (10.64) | 3 (6.38) | 5 (10.64) | 8 (17.02) |

| Age, mean (SE) | 27.51 (5.35) | 30.28 (7.00) | 29.92 (7.37) | 28.22 (5.15) | 29.16 (6.47) |

| Outcome measures | |||||

| B&B | 3.94 (1.24) | 3.88 (1.92) | 3.57 (1.47) | 4.35 (1.84) | 3.90 (1.66) |

| BDI | 11.55 (6.85) | 12.66 (8.25) | 11.96 (7.36) | 12.22 (8.53) | 12.06 (7.49) |

| ISS | 18.05 (10.97) | 21.06 (11.77) | 16.90 (9.70) | 24.84 (12.36) | 19.40 (11.33) |

| NRS | 4.63 (2.17) | 4.25 (1.85) | 4.30 (1.77) | 4.83 (1.87) | 4.46 (2.03) |

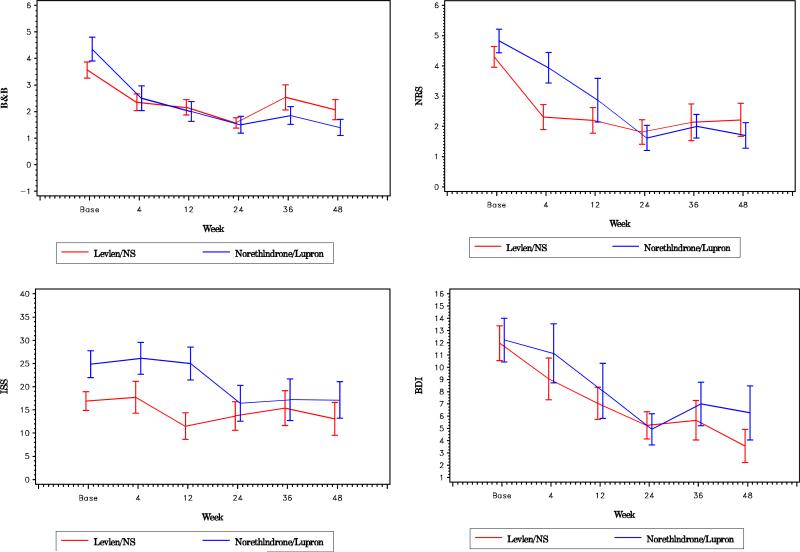

The trend in pain reduction scores for each treatment at each time point is shown in Figure 1. It can be seen that both B&B and NRS pain scores declined after the commencement of both NA and OC treatment and that self-reported pain measures continued at a lower level for both NA and OC through 48 weeks of treatment. Using the linear mixed model described above and as reported in Table 3, the reductions in B&B and NRS pain scores from baseline levels were statistically significant at each of the five time points measured through 48 weeks, with the exception of the B&B score at 36 weeks for the OC group (P=.06). However, comparisons of treatment show that the extent of pain reduction from baseline, whether measured by B&B or NRS, was no different for the two treatments. Analysis using two-sample t-tests at each time point also confirms that the difference in treatments was not significant (data not shown). Significant reductions were seen in BDI scores for both treatments at all time points, with the exception of the BDI score at 4 weeks in both groups. The ISS appeared to show improved scores in weeks 24–48 of leuprolide treatment, but there was no overall difference in treatment effect on sexual satisfaction between the two treatments using mixed model analysis.

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of trends between leuprolide and oral contraceptive groups in pain and quality-of-life assessments. Mean values with standard error bars are shown at each time of assessment.

TABLE 3.

Mixed model analysis: the estimates, SE, and P values for changes in outcome measures from baseline for each treatment at each time point.

| 4 wk | 12 wk | 24 wk | 36 wk | 48 wk | Treatment comparisona | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B&B | ||||||

| Levlen/NS | ||||||

| n | 23 | 19 | 14 | 15 | 14 | |

| Coefficient | –1.22 | –1.48 | –1.80 | –0.97 | –1.40 | |

| SE | 0.45 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | |

| P value | 0.0112 | 0.0035 | 0.0009 | 0.0578 | 0.0082 | .95, SE = ±0.57 (P= .10) |

| Leuprolide/norethindrone | ||||||

| N | 14 | 15 | 12 | 13 | 10 | |

| Coefficient | –1.88 | –2.18 | –2.77 | –2.36 | –2.71 | |

| SE | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.55 | |

| P value | .0006 | .0001 | < .0001 | < .0001 | < .0001 | |

| ISS | ||||||

| Levlen/NS | ||||||

| n | 16 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 9 | |

| Coefficient | 1.42 | –1.15 | –1.34 | –0.51 | –2.41 | |

| SE | 1.63 | 1.72 | 1.76 | 1.79 | 1.82 | |

| P value | .3934 | .513 | .4523 | .7775 | .1959 | 4.69, SE = ±2.72, (P= .10) |

| Leuprolide/norethindrone | ||||||

| n | 10 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 10 | |

| Coefficient | 0.20 | –3.58 | –9.32 | –8.91 | –12.18 | |

| SE | 3.27 | 3.28 | 3.85 | 3.45 | 3.45 | |

| P value | .9515 | .2846 | .0208 | .0148 | .0013 | |

| BDI | ||||||

| Levlen/NS | ||||||

| n | 20 | 20 | 16 | 15 | 14 | |

| Coefficient | –2.41 | –3.92 | –5.22 | –4.70 | –6.53 | |

| SE | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.26 | 1.28 | 1.30 | |

| P value | .0536 | .0029 | .0002 | .0008 | < .0001 | –0.84, SE = ±1.59, (P=.60) |

| Leuprolide/norethindrone | ||||||

| n | 15 | 15 | 13 | 13 | 11 | |

| Coefficient | –0.75 | –3.94 | –6.26 | –4.18 | –3.72 | |

| SE | 1.55 | 1.55 | 1.64 | 1.64 | 1.73 | |

| P value | .6325 | .0158 | .0005 | .0145 | .0369 | |

| NRS | ||||||

| Levlen/NS | ||||||

| n | 23 | 20 | 16 | 15 | 14 | |

| Coefficient | –2.25 | –2.43 | –2.82 | –2.55 | –2.53 | |

| SE | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.59 | |

| P value | .0001 | < .0001 | < .0001 | < .0001 | < .0001 | –0.11, SE = ±0.61, (P=.85) |

| Leuprolide/norethindrone | ||||||

| n | 16 | 15 | 13 | 13 | 10 | |

| Coefficient | –1.04 | –2.08 | –3.59 | –3.21 | –3.56 | |

| SE | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.54 | |

| P value | .0236 | < .0001 | < .0001 | < .0001 | < .0001 |

Comparison of treatments by mixed models effect. Listed are the estimated coefficient ±SE and P value.

No significant adverse events were reported. Based on responses to a survey of side effects by each subject at each visit, there were six or fewer total reported episodes of headache, breast tenderness, bloating, reduced libido, mood change, and nausea in each treatment group. Vaginal bleeding was reported in 22 of 81 responses in the OC group, as compared with 12 of 72 responses in the NA group (P=.24) Hot flashes occurred in 11 of 82 and 12 of 73 responses in the OC and NA groups (P=.65).

DISCUSSION

The major findings of this prospective, randomized, double-blind 48-week trial of a continuous OC versus LA in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pelvic pain were that [1] both treatment arms provided a significant reduction in pain from baseline and [2] there was no significant difference in the extent of pain relief between the two treatment regimens.

A detailed cost-effectiveness evaluation is beyond the scope of this report, but based on 2009 prices in Boston, Massachusetts, and Rochester, New York, the cost of leuprolide depot 11.25 mg (four injections at $1,800 each) plus NA 5 mg (336 pills at $2.40 each) totals $8,006. The OC arm (ethinyl estradiol 35 μg plus NA) entailed 16 3-week pill packs at $28.38 each, totaling $454. Thus, to achieve a reduction in pain that is not significantly different from leuprolide treatment, a 48-week treatment of OCs would save $7,552 per patient over 48 weeks.

There has been only one previous randomized trial of a GnRH agonist versus continuous OCs in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain. Zupi and colleagues randomized 133 women to three regimens in the treatment of women with relapsing pain after surgery for endometriosis (21): GnRH agonist plus add-back consisting of transdermal E2 25 μg and norethindrone 5 mg, GnRH agonist alone, or a continuous contraceptive consisting of ethinyl estradiol 30 μg and gestodene 0.75 mg daily. Patients were treated for 12 months with assessments of pain, quality of life, and measurement of bone mineral density. In contrast to our study, Zupi et al. found that patients treated with GnRH agonist with or without hormonal add-back had better relief of dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and pelvic pain at 6 and 12 months of treatment and at 6-month follow-up than those on OCs. The GnRH agonist groups, however, showed increased bone loss compared with the OC group.

One reason for the different results in this study may be different assessments of pelvic pain (a visual analog scale versus two measures—the often used B&B scale and the validated NRS scale in this trial). The varying conclusions of our study and that of Zupi et al. point to the importance of conducting confirmatory studies in different populations.

The strengths of this clinical trial include its study design (randomized, double-blind prospective, multicenter) and the choice of contemporary medical regimens currently in widespread clinical use in the United States. It examined two well-characterized and widely accepted pain assessments: the B&B patient ratings, the most widely used pain score for assessing endometriosis-associated pelvic pain; and the NRS, a commonly used general pain assessment. In addition, the two centers permitted diversity in geography and in the types of practices from which patients were recruited, allowing the potential for more generalizable conclusions.

The greatest weakness of the study is its limited sample size, a direct result of significant challenges in subject recruitment. Both sites were unable to achieve patient accrual goals. In Rochester, it was anticipated that subjects would be recruited from university practices and several affiliated practices. Recruitment, particularly among the private groups, fell well short of expectations, largely because of changes in practice patterns—patients with pelvic pain and symptoms of endometriosis were often treated empirically. In Boston, it was anticipated that the majority of patients would come from the practice of the co-PI (MDH), who maintains an extensive endometriosis referral practice. In the end, very few patients came from his practice, largely because nearly all patients had already been treated with a regimen similar to one of the treatment arms, and the great majority of subjects were recruited from print and radio advertisements. The study was powered to recruit 188 subjects, 94 from each site. In the end, only 47 patients, 28 from Boston and 19 from Rochester, entered the trial. As it turned out, the observed reduction in pain scores was greater than assumed in the power analysis, resulting in statistically significant declines in each group, even with the smaller sample size. That said, we would have greater confidence in the conclusions if the sample size were greater.

A second limitation was the high dropout rate. Of the 40 patients enrolled at baseline, only 24 (60%) completed the trial. Reasons for dropout varied but included lack of improvement in pain symptoms, side effects, and a decision to proceed with alternative therapies such as surgery. Recognizing potential bias from dropout, our linear mixed model took account of all data at each monitoring visit across time. Thus, we used all available data on each subject. That said, the reduced number of subjects at the study's end limited statistical significance, particularly in the later weeks of treatment.

Finally, this trial did not use a placebo arm. Since FDA approval of nafarelin in 1989 as the first GnRH agonist for the treatment of endometriosis, the FDA has not required a placebo arm, allowing equivalence with an approved drug as demonstration of efficacy. It has long been accepted that use of a placebo in pelvic pain trials is unethical, and for that reason a placebo arm was not used in this trial.

In conclusion, this 48-week randomized prospective trial of a continuous OC pill versus a GnRH agonist plus progestin hormonal add-back demonstrated roughly equal clinical and quality-of-life outcomes. Given the lower cost and generally low side effects of OCs, these data support the use of continuous OCs as first-line therapy in the medical treatment of endometriosis-associated pelvic pain.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant nos. R01HD044870 and UL1RR024160.

Footnotes

D.S.G. has nothing to disclose. L.-S.H. has nothing to disclose. B.A.B. has nothing to disclose. M.N. has nothing to disclose. M.D.H. has nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Walker EA, Katon WJ, Jemelka RP. The prevalence of chronic pelvic pain and irritable bowel syndrome in two university clinics. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 1991;12(Suppl):65–75. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jamieson DJ, Steege JF. The prevalence of dysmenor-rhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, and irritable bowel syndrome in primary care practices. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:55–8. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00360-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milburn A, Reiter RC, Rhomberg AT. Multi-disciplinary approach to chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1993;20:643–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howard FM. Laparoscopic evaluation and treatment of women with chronic pelvic pain. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1994;1:325–31. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)80797-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Candiani GB, Fedele L, Vercellini P, Bianchi S, Di Nola G. Presacral neurectomy for the treatment of pelvic pain associated with endometriosis: a controlled study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167(1):100–3. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)91636-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parazzini F, Fedele L, Busacca M, Falsetti L, Pellegrini S, Venturini PL, et al. Postsurgical medical treatment of advanced endometriosis: results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:1205–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(94)90133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hornstein MD, Hemmings R, Yuzpe AA, Heinrichs WL. Use of nafarelin versus placebo after reductive laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1997;68:860–4. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(97)00360-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Telimaa S, Puolakka J, Ronnberg L, Kauppila A. Placebo-controlled comparison of danazol and high-dose medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of endometriosis after conservative surgery. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1987;1:363–71. doi: 10.3109/09513598709082709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hornstein MD, Surrey ES, Weisberg GW, Casino LA. Leuprolide acetate depot and hormonal add-back in endometriosis: a 12-month trial. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:16–24. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00620-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vercellini P, Trespidi L, Colombo A, Vendola N, Marchini M, Crosignani PG. A gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist versus a low-dose oral contraceptive for pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1993;60:75–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muzii L, Marana R, Caruana P, Catalano GF, Margutti F, Panici PB. Postoperative administration of monophasic combined oral contraceptives after laparoscopic treatment of ovarian endometriomas: a prospective, randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:588–92. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dworkin RH, Nagasako EM, Hetzel RD, Farrar JT. Assessment of pain and pain-related quality of life in clinical trials. In: Turk DC, Melzak R, editors. Handbook of pain assessment. 2d ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2001. pp. 659–92. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masheb RM, Nash JM, Brondolo E, Kerns RD. Vulvodynia: an introduction and critical review of a chronic pain condition. Pain. 2000;86:3–10. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biberoglu KO, Behrman SJ. Dosage aspects of danazol therapy in endometriosis: short-term and long-term effectiveness. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;139:645–54. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(81)90478-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM, Fisher LD. Visual Analog Score: comparative reliability and validity of chronic pain intensity measures. Pain. 1999;83:157–62. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00101-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory manual. 2d ed. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown C, Schulberg HC, Madonia MJ. Assessing depression in primary care practice with the Beck Depression Inventory and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. Psychol Assess. 1995;7:59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kames LD, Rapkin AJ, Naliboff BD, Afifi S, Ferrer-Brechner T. Effectiveness of an interdisciplinary pain management program for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain. Pain. 1990;41:41–6. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)91107-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hudson WW, Harrison DF, Crossup PC. A short-form scale to measure sexual discord in dyadic relationships. J Sex Res. 1981;17:157–74. [Google Scholar]

- 20.SAS Institute Inc. SAS companion for the Microsoft Windows Environment, Version 8. SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zupi E, Marconi D, Sbracia M, Zullo F, De Vivo B, Exacustos C, et al. Add-back therapy in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:1303–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.03.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]