Abstract

Nitrogen mustard (NM) is a toxic alkylating agent that causes damage to the respiratory tract. Evidence suggests that macrophages and inflammatory mediators including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α contribute to pulmonary injury. Pentoxifylline is a TNFα inhibitor known to suppress inflammation. In these studies, we analyzed the ability of pentoxifylline to mitigate NM-induced lung injury and inflammation. Exposure of male Wistar rats (250 g; 8–10 weeks) to NM (0.125 mg/kg, i.t.) resulted in severe histolopathological changes in the lung within 3 d of exposure, along with increases in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cell number and protein, indicating inflammation and alveolar-epithelial barrier dysfunction. This was associated with increases in oxidative stress proteins including lipocalin (Lcn)2 and heme oxygenase (HO)-1 in the lung, along with pro-inflammatory/cytotoxic (COX-2+ and MMP-9+), and anti-inflammatory/wound repair (CD163+ and Gal-3+) macrophages. Treatment of rats with pentoxifylline (46.7 mg/kg, i.p.) daily for 3 d beginning 15 min after NM significantly reduced NM-induced lung injury, inflammation, and oxidative stress, as measured histologically and by decreases in BAL cell and protein content, and levels of HO-1 and Lcn2. Macrophages expressing COX-2 and MMP-9 also decreased after pentoxifylline, while CD163+ and Gal-3+ macrophages increased. This was correlated with persistent upregulation of markers of wound repair including pro-surfactant protein-C and proliferating nuclear cell antigen by Type II cells. NM-induced lung injury and inflammation were associated with alterations in the elastic properties of the lung, however these were largely unaltered by pentoxifylline. These data suggest that pentoxifylline may be useful in treating acute lung injury, inflammation and oxidative stress induced by vesicants.

Keywords: pentoxifylline, vesicants, mustards, lung injury, macrophages, oxidative stress

Introduction

Sulfur mustard and related analogs including nitrogen mustard (NM) are bi-functional alkylating agents synthesized for use as chemical warfare agents (McManus and Huebner, 2005; Saladi et al., 2006). Although NM was never used in combat, it was amassed during World War II. Subsequently, NM was developed as an anticancer agent for treating lymphoma, as well as lung and breast cancer (Colvin M, 2010; Gulati et al., 1988). Sulfur mustard and NM are vesicants that cause severe damage to target organs, such as the lung (Weinberger et al., 2011). Toxicity results from alkylation and cross-linking of nucleic acids, as well as proteins, lipids and other membrane components, leading to impairment of cellular functioning and cell death. Oxidative and nitrosative stress have also been shown to contribute to toxicity (Laskin et al., 2010). This is supported by findings that antioxidants ameliorate vesicant-induced lung injury (Anderson et al., 2009; Hoesel et al., 2008; McClintock et al., 2006; McClintock et al., 2002).

Accumulating evidence from both experimental and human exposures suggests an involvement of inflammatory cells and mediators they release in vesicant-induced lung injury (Weinberger et al., 2011; Wigenstam et al., 2012). Of particular interest is tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α, a macrophage-derived pro-inflammatory cytokine rapidly generated in the lung in response to injury induced by vesicants (Malaviya et al., 2010; Sunil et al., 2011b; Sunil et al., 2012). The major receptor mediating the pro-inflammatory activity of TNFα is TNFR1 (Parameswaran and Patial, 2010). In earlier studies we demonstrated that mice lacking TNFR1 are protected from vesicant-induced lung injury, suggesting a key role of TNFα in the pathological response to mustards (Sunil et al., 2011a).

Pentoxifylline is a methyl xanthine phosphodiesterase inhibitor reported to downregulate production of the pro-inflammatory cytokine, TNFα (Fernandes et al., 2008; Gonzalez-Espinoza et al., 2012; Turhan et al., 2012). It has been used clinically to treat a broad spectrum of inflammatory pathologies including alcoholic hepatitis, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, kidney disease and rheumatoid arthritis (Day, 2012; Dhanda et al., 2012; Gallardo et al., 2007; Goicoechea et al., 2012; Shan et al., 2012). In the present studies we assessed the ability of pentoxifylline to attenuate pulmonary toxicity induced by NM. Our findings that administration of pentoxifylline to rats 15 min after NM exposure reduces acute injury, inflammation and oxidative stress suggest that it may be efficacious for the treatment of acute lung toxicity following exposure to vesicants.

Materials and Methods

Animals and treatments

Male, specific pathogen-free Wistar rats (150–174 g) were obtained from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN). Animals were housed in microisolation cages and maintained on sterile food and pyrogen-free water ad libitum. All animals received humane care in compliance with the institution’s guidelines, as outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, published by the National Institutes of Health. Animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of ketamine:xylazine (80 mg/kg:10 mg/kg) and then placed on a titling rodent work stand (Hallowell EMC, Pittsfield, MA) in a supine position and restrained using an incisor loop. The tongue was extruded using a cotton tip applicator and the larynx visualized by a hemi-sectioned 4 mm speculum attached to an operating head of an otoscope (Welch Allyn, Skaneateles Falls, NY). NM (mechlorethamine hydrochloride, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in PBS was administered via Clay Adams Intramedic PE-60 (I.D. 0.76 mm, O.D. 1.22 mm) polyethylene tubing (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ) attached to a 20 gauge hypodermic needle. The tubing was advanced approximately 20 mm past the epiglottis and 0.1 ml of sterile PBS or NM (0.125 mg/kg) instilled into the trachea. The tubing and speculum were withdrawn immediately after instillation. Animals were then removed from the work stand and maintained in a vertical position until normal respiration was observed (less than 1 min). All instillations were performed by David Reimer, DVM, Rutgers University Laboratory Animal Services. Pentoxifylline (3,7-Dimethyl-1-(5-oxohexyl)-3,7-dihydro-1H-purine-2,6-dione, 46.7 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich) was administered i.p. daily beginning 15 min after NM.

Sample collection

Animals were euthanized 3 d after exposure to NM or PBS by i.p. injection of Sleepaway® (0.44 kg/ml; Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, IA). PBS (10 ml) was instilled into the lung via a cannula in the trachea. BAL was collected by slowly withdrawing the fluid. BAL fluid was centrifuged (300 x g, 8 min), supernatants collected, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C until analysis. The cell pellet was resuspended in 1 ml PBS and viable cells counted with a hemocytometer using trypan blue dye exclusion. Total protein was quantified in cell-free BAL using a BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce Biotechnologies Inc., Rockford, IL) with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Following BAL collection, the lung was removed, fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 4 h on ice and then transferred to 50% ethanol. Histological sections (4 μm) were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The extent of inflammation, including macrophage and neutrophil localization, alterations in alveolar epithelial barriers, fibrin deposition and edema, were assessed blindly by a board certified veterinary pathologist (LeRoy Hall, DVM, Ph.D.). Images were acquired at high resolution using an Olympus VS120 Virtual Microscopy System, scanned and viewed using OlyVIA version 2.6 software (Center Valley, PA).

For immunohistochemistry, tissue sections were deparaffinized. After antigen retrieval using citrate buffer (10.2 mM sodium citrate, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 6.0) and quenching of endogenous peroxidase with 3% H2O2 for 15 min, sections were incubated at room temperature for 2 h with 5–100% goat or horse serum to block nonspecific binding. This was followed by incubation overnight at 4°C with rabbit or mouse IgG or anti-heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1, 1:200, Stressgen/Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY), anti-matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9, 1:100, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), anti-pro-surfactant protein (SP)-C (pro-SP-C, 1:500, EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA), anti-cycloxygenase-2 (COX-2, 1:500, Abcam), anti-proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA, 1:400, Abcam), anti-CD163 (1:200, ABD Serotec, Raleigh, NC) or anti-galectin-3 (Gal-3, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) antibodies. Sections were then incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) for 30 min at room temperature. Binding was visualized using a Peroxidase Substrate Kit DAB (Vector Labs). Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin for 1 min followed by PBS for 30 sec.

Western blotting

BAL was concentrated using Amicon Ultra (0.5 ml) Ultracel®-10K membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA), and 5 μg of proteins fractionated by 20% SDS-PAGE, and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (0.45 μm pore size; Millipore). Non-specific binding was blocked by incubation of the blots for 2 h at room temperature with 5% non-fat dry milk in 0.1% TBS-T buffer (0.02 M Tris-base, 0.137 M sodium chloride, 0.1% Tween-20). Blots were incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit polyclonal anti-Lcn2 (1:500, Abcam) or anti-Clara cell secretory protein (CCSP, 1:30,000, Millipore) antibodies. After 5 washes in 0.1% TBS-T buffer, blots were incubated with anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:20,000, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) for 1 h at room temperature. Bands were visualized using an ECL prime detection system (GE, Healthcare Bio-Science Corp, Piscataway, NJ).

Measurement of lung mechanics and function

Animals were weighed and anesthetized i.p. with 80 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine. After 5 min, tracheotomy was performed using a 15-gauge cannula, the animals attached to a SciReq flexiVent (Montreal, Canada) and ventilated at a frequency of 90 breaths/min and a tidal volume of 10 mg/ml. Baseline lung mechanics were measured using the forced oscillation technique at a positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 3 cm H2O. Derecruitment was assessed at four levels of PEEP following two 6 sec deep-inflation maneuvers to a peak pressure of 30 cm of H2O. Following deep-inflation, respiratory impedance was measured every 15 sec over 8.5 min for each PEEP. Constant phase model parameters were estimated using flexi Vent software version 7.2.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated 3–4 times. Data were analyzed using student’s t-test and 2-way ANOVA; a p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Effects of pentoxifylline on NM-induced lung inflammation, injury and oxidative stress

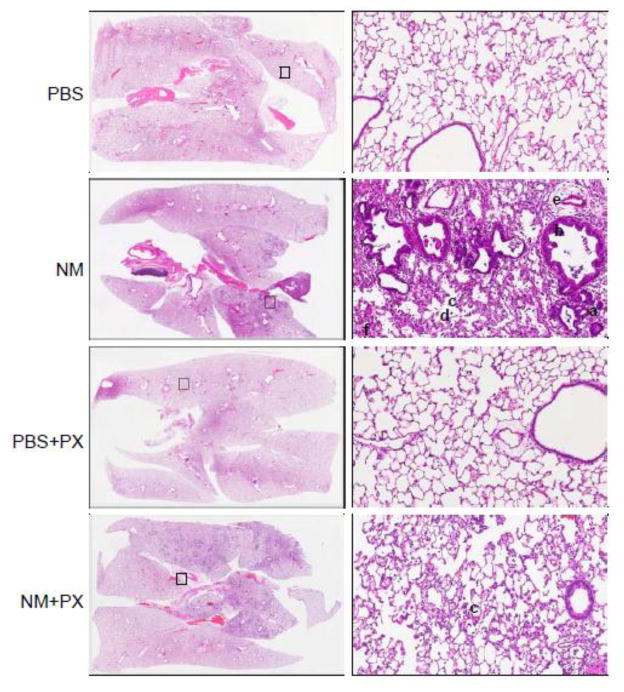

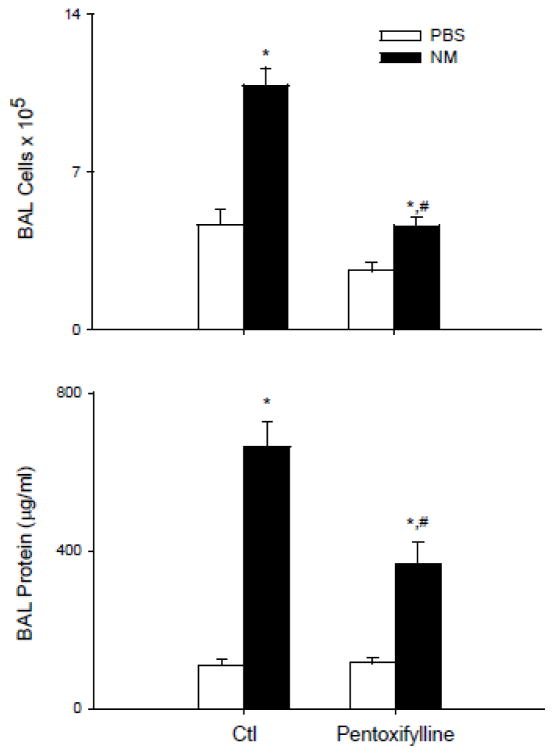

Treatment of rats with NM resulted in marked histolopathological changes in the lung within 3 d of exposure; these included macrophage and granulocyte infiltration, edema, fibrin deposition in bronchiolar and alveolar epithelium, bronchiectasis, fibroplasia and emphysema (Figure 1 and Table 1). This was associated with an increase in cells and protein in BAL fluid, markers of inflammation and injury, respectively (Figure 2). Daily administration of pentoxifylline to rats beginning 15 min after NM, significantly reduced granulocyte infiltration into the tissue, as well as edema, fibrin deposition and fibroplasia (Table 1); BAL protein and cell number were also significantly reduced (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Effects of pentoxifylline on NM-induced alterations in lung structure. Animals were treated with PBS or NM followed by daily administration of pentoxifylline (PX). After 3 d, histologic sections were prepared and stained with H & E. Images were acquired using a VS120 Virtual Microscopy system. One representative lung section from 4–8 rats per treatment group is shown. Left panels: Magnification, 2x; Right panels: Magnification, 100x; squares indicate regions of high power magnification in right panels. a, bronchiectasis, b, hypercellularity of bronchiolar epithelium; c, infiltrating macrophages; d, emphysema; e, edema; f, fibrin deposits.

Table 1.

Effects of pentoxifylline on pulmonary pathology

| PBS | NM | PBS+ PX | NM + PX | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Congestion | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.8 ± 0.6 |

| Macrophage Infiltrates | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.0* | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 3.0 ± 0.0 |

| Granulocytic Infiltrates | - | 3.0 ± 0.0 | - | 1.8 ± 0.3# |

| Edema | - | 3.0 ± 0.0 | - | 2.0 ± 0.0# |

| Fibrin | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.0* | - | 1.5 ± 0.5# |

| Bronchiolar Alveolar Hyperplasia | - | 3.5 ± 0.3 | - | 2.5 ± 0.3 |

| Bronchiectasis | - | 3.0 ± 0.0 | - | 2.3 ± 0.3 |

| Fibroplasia | - | 3.5 ± 0.3 | - | 2.0 ± 0.0# |

| Hemorrhage | 0.5 ± 0.2 | - | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.5 |

| Emphysema | - | 2.8 ± 0.3 | - | 2.0 ± 0.0 |

| Mesothelial Proliferation | - | 2.0 ± 0.0 | - | 2.0 ± 0.0 |

| Fibrosis | - | 0.8 ± 0.8 | - | 1.0 ± 0.6 |

| Hypertrophy/Hyperplasia Bronchiolar Epithelium | - | 3.0 ± 0.0 | - | - |

The extent of pulmonary pathology including macrophage and granulocyte infiltration, edema, alterations in alveolar-epithelial barriers, emphysema and fibrin deposition were assessed 3 d following exposure of rats to NM, PBS, pentoxifylline (PBS+PX) or NM+PX. Semi-quantitative grades (0 to 3) were assigned to sections, with grade 0 indicating no changes; grade 1, minimal or small changes; grade 2, mild to medium changes; and grade 3, moderate to extensive changes, relative to PBS controls. Values are means ± SE (n=4–8).

Statistically different (p<0.05) from PBS;

Statistically different (p<0.05) from NM.

Figure 2.

Effects of pentoxifylline on NM-induced increases in BAL cells and protein. Animals were treated with PBS or NM followed by daily administration of pentoxifylline (PX). After 3 d, BAL was collected and analyzed for cell and protein content. Top panel: Viable cells were enumerated by trypan blue dye exclusion. Bottom panel: Cell-free supernatants were analyzed in triplicate for protein content using a BCA protein assay kit. Each bar is the average ± SE (n = 6–12 rats). *Significantly different (p <0.05) from PBS; #Significantly different (p<0.05) from NM.

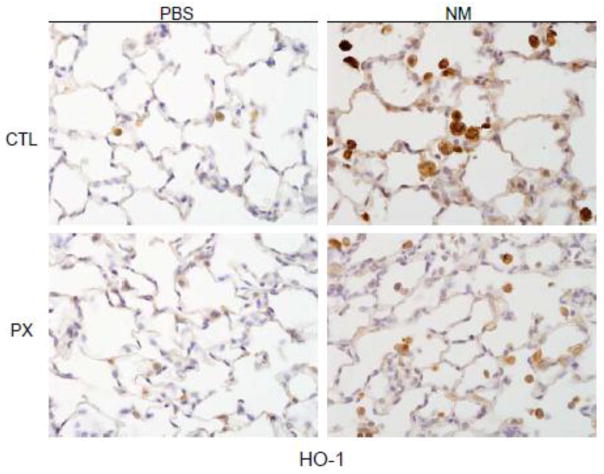

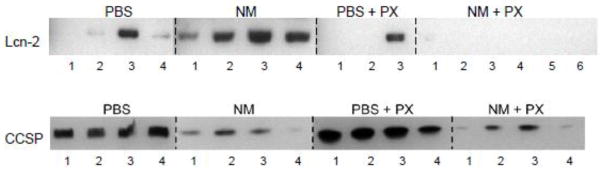

Lcn2 is a member of the lipocalin superfamily known to be up-regulated in response to oxidative stress (Roudkenar et al., 2007). Figure 3 shows that NM administration to rats resulted in an increase in BAL levels of Lcn2, which is consistent with our earlier findings (Sunil et al., 2012). Expression of HO-1, an antioxidant enzyme important in protecting the lung from oxidative stress (Ryter et al., 2007), was also increased after NM exposure (Figure 4). This was most prominent in alveolar macrophages. Treatment of rats with pentoxifylline reduced the effects of NM on macrophage HO-1 expression, and on BAL Lcn2 levels (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Effects of pentoxifylline on BAL levels of Lcn2 and CCSP. Animals were treated with PBS or NM followed by daily administration of pentoxifylline (PX). After 3 d, BAL was collected, concentrated and analyzed for Lcn2 and CCSP levels by western blotting. Each lane represents BAL from 1 rat. Three to six rats per treatment group are shown.

Figure 4.

Effects of pentoxifylline on NM-induced HO-1 expression. Animals were treated with PBS or NM followed by daily administration of pentoxifylline (PX). After 3 d, lung sections were prepared and stained with antibody to HO-1. Binding was visualized using a peroxidase DAB substrate kit. One representative section from 4 rats per treatment group is shown (Original magnification, x600).

Effects of pentoxifylline on NM-induced increases in classically and alternatively activated macrophages, and on markers of tissue repair

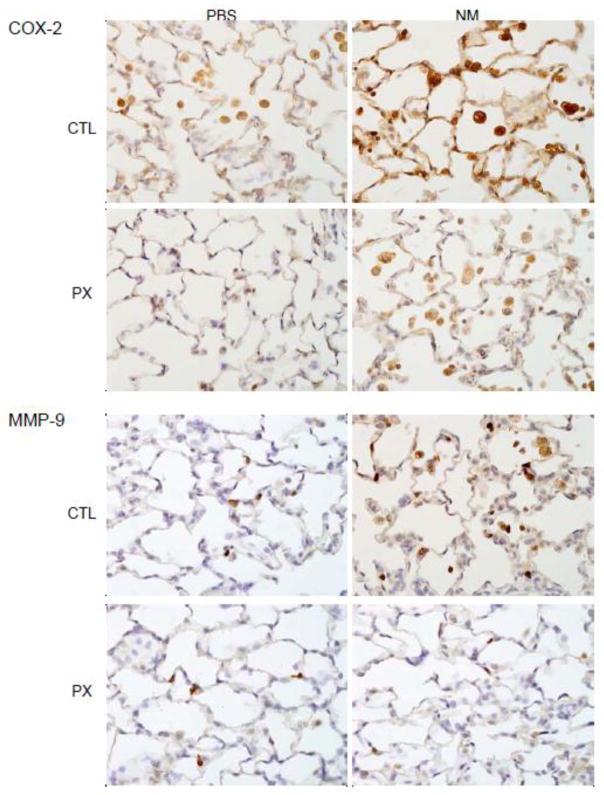

We previously demonstrated that NM-induced injury is associated with an accumulation of classically activated pro-inflammatory/cytotoxic and alternatively activated anti-inflammatory/wound repair macrophages in the lung (Malaviya et al., 2012). In further studies, we examined the effects of pentoxifylline on NM-induced accumulation of these macrophage subpopulations. COX-2 is an inducible enzyme mediating the formation of pro-inflammatory eicosanoids implicated in lung injury, and a marker of classically activated macrophages (Laskin et al., 2011). In control rats, alveolar macrophages were found to express low levels of COX-2 (Figure 5). A marked increase in COX-2 expression was observed in alveolar macrophages, as well as in alveolar epithelial cells following NM exposure. MMP-9 is a matrix metalloproteinase produced by proinflammatory/cytotoxic macrophages and is important in tissue injury and remodeling (Muroski et al., 2008). We found that MMP-9 was upregulated in lung macrophages after NM exposure (Figure 5). Pentoxifylline abrogated the effects of NM on both COX-2 and MMP-9 expression in lung macrophages.

Figure 5.

Effects of pentoxifylline on NM-induced COX-2 and MMP-9 expression. Animals were treated with PBS or NM followed by daily administration of pentoxifylline (PX). After 3 d, lung sections were prepared and stained with antibody to COX-2 or MMP-9. Binding was visualized using a peroxidase DAB substrate kit. One representative section from 4 rats per treatment group is shown (Original magnification, x600).

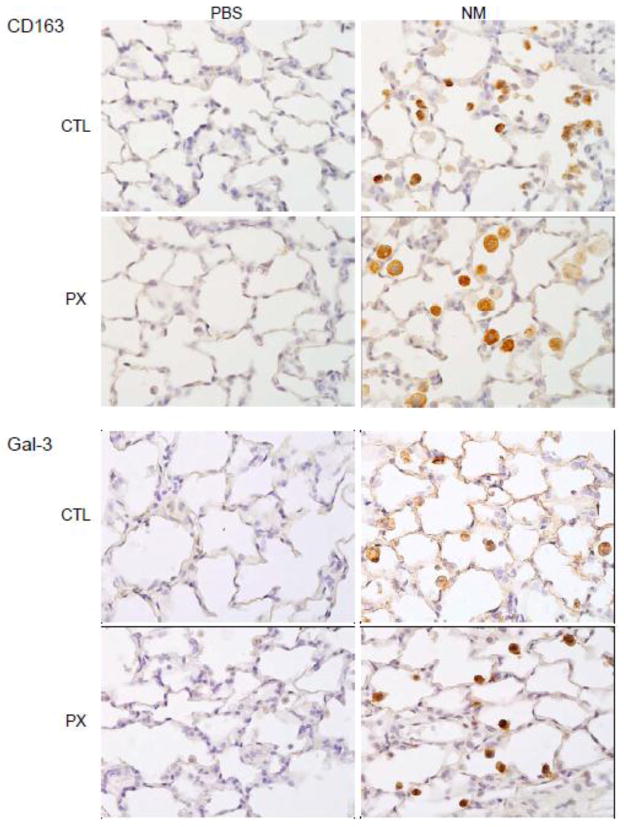

CD163 and Gal-3 are markers of alternatively activated lung macrophages (Gibbons et al., 2011; Gong et al., 2012; MacKinnon et al., 2008). Exposure of animals to NM resulted in increased numbers of CD163+ and Gal-3+ macrophages in the lung (Figure 6). This response was increased in rats treated with pentoxifylline. We also found that after pentoxifylline administration, CD163+ cells were larger and more vacuolated than macrophages in lungs of NM treated animals (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effects of pentoxifylline on NM-induced CD163 and galectin-3 (Gal-3) expression. Animals were treated with PBS or NM followed by daily administration of pentoxifylline (PX). After 3 d, lung sections were prepared and stained with antibody to CD163 or Gal-3. Binding was visualized using a peroxidase DAB substrate kit. One representative section from 4 rats per treatment group is shown (Original magnification, x600).

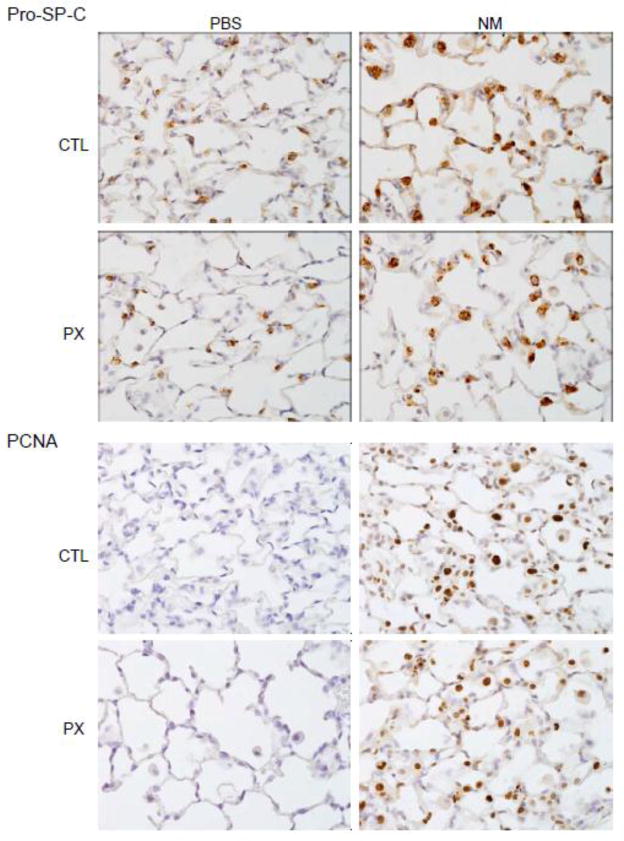

Increases in numbers of anti-inflammatory/wound repair macrophages following NM exposure were correlated with upregulation of markers of tissue repair in Type II epithelial cells; these included pro-SP-C, a precursor of SP-C synthesized by activated alveolar epithelial cells in response to tissue injury, and PCNA, a marker for Type II cell proliferation (Figure 7) (Lee et al., 2012; Mason, 2006). Pentoxifylline has no effect on Type II cell expression of pro-SP-C or PCNA indicating the persistence of tissue repair. NM-induced decreases in BAL levels of CCSP, an anti-inflammatory protein constitutively secreted by Clara cells (Wong et al., 2009), were also unaffected by pentoxifylline administration (Figure 3).

Figure 7.

Effects of pentoxifylline on NM-induced pro-SP-C and PCNA expression. Animals were treated with PBS or NM followed by daily administration of pentoxifylline (PX). After 3 d, lung sections were prepared and stained with antibody to pro-SP-C or PCNA. Binding was visualized using a peroxidase DAB substrate kit. One representative section from 4 rats per treatment group is shown (Original magnification, x600).

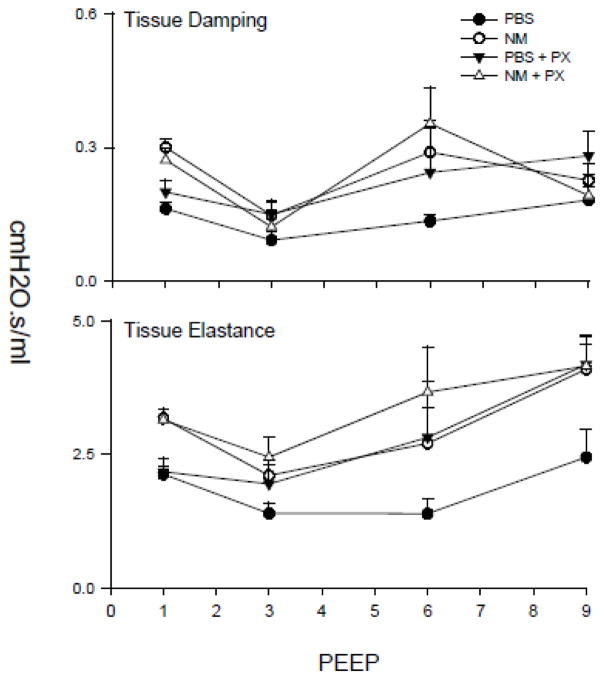

NM-induced alterations in pulmonary mechanics

We next determined if structural and inflammatory changes induced in the lung by NM were associated with alterations in parenchymal mechanical properties. This was assessed by measuring pulmonary impedance following deep-inflation as a function of increasing PEEP. NM exposure was found to result in an increase in the tissue elastance (H) and resistance (G) parameters, across all levels of PEEP (Figure 8). These increases were evident immediately following deep inflation; conversely the rate and extent of changes in H and G over the measurement interval were not altered. Pentoxifylline had no significant effects on NM-induced alterations in tissue damping or elastance.

Figure 8.

Effects of pentoxifylline on NM-induced alterations in lung function. Animals were treated with PBS or NM followed by daily administration of pentoxifylline (PX). After 3 d, measurements were made in triplicate of tissue damping and elastance at PEEPs ranging from 1 to 9 cm H2O. Each point is the mean ± SE (n = 6 rats).

Discussion

Pentoxifylline is a nonspecific phosphodiesterase inhibitor with anti-inflammatory activity, which is due in part to its ability to block TNFα (Fernandes et al., 2008; Gonzalez-Espinoza et al., 2012; Turhan et al., 2012). In this regard, pentoxifylline has been found to be clinically efficacious in a number of inflammatory pathologies characterized by increased TNFα production including alcoholic liver disease and rheumatoid arthritis (Queiroz-Junior et al., 2013; Sidhu et al., 2012; Zaitone et al., 2011). Since TNFα is a key mediator of pulmonary toxicity induced by vesicants (Sunil et al., 2011a), we tested the ability of pentoxifylline to mitigate NM-induced lung toxicity. We found that pentoxifylline, administered daily beginning 15 min after NM exposure, attenuated lung injury, inflammation and oxidative stress induced by this vesicant. This was associated with a reduction in pro-inflammatory/cytotoxic macrophages and an increase in anti-inflammatory/wound repair macrophages in the lung. These data suggest that pentoxifylline may be useful for the treatment of acute lung injury and inflammation induced by vesicants.

NM-induced pulmonary toxicity is characterized by prominent histopathologic alterations in the lung including inflammatory cell accumulation, edema, fibrin deposition, bronchiolar and alveolar epithelial hyperplasia, bronchiectasis, fibroplasia and emphysema, along with increases in BAL protein and cells, which is in accord with previous studies (Malaviya et al., 2012; Sunil et al., 2011b). Pentoxifylline post-treatment significantly attenuated histologic evidence of pulmonary inflammation and injury, as well as increases in BAL protein and cell content. Similar suppression of inflammation and tissue damage have been described following pentoxifylline administration in models of lung injury induced by mechanical ventilation, sepsis, hyperoxia, meconium aspiration, thermal injury, and acute pancreatitis (Almario et al., 2012; de Campos et al., 2008; Oliveira-Junior et al., 2010; Oliveira-Junior et al., 2003; Ramallo et al., 2013; Turhan et al., 2012). Based on these observations, we suggest that pentoxifylline is efficacious in a broad spectrum of lung pathologies with diverse etiologies.

Oxidative stress has been proposed to play an important role in vesicant-induced pulmonary toxicity (Anderson et al., 2009; Hoesel et al., 2008; Malaviya et al., 2012; Mukhopadhyay et al., 2006; Sunil et al., 2012). In response to oxidative stress, cells upregulate HO-1, a phase II stress response enzyme with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity (Otterbein et al., 1999; Rahman et al., 2006). Consistent with induction of oxidative stress, we found that HO-1 expression increased in alveolar macrophages following NM exposure. BAL levels of the oxidative stress marker, Lcn2, which we previously demonstrated increases after vesicant exposure, were also elevated (Sunil et al., 2012). Administration of pentoxifylline to rats reduced NM-induced HO-1 expression by alveolar macrophages, as well as BAL Lcn2 levels, demonstrating that pentoxifylline is effective in reducing NM-induced oxidative stress. These findings are in accord with earlier studies showing that pentoxifylline reduces oxidative stress induced by thermal injury, airway obstruction, steatohepatitis, acute pancreatitis, and kidney injury (Barkhordari et al., 2011; Chae et al., 2012; Escobar et al., 2012; Ramallo et al., 2013; Venugopal et al., 2013; Zein et al., 2012). The mechanism underlying the antioxidant actions of pentoxifylline in NM-induced lung toxicity are unknown. Pentoxifylline has been reported to inhibit lipid oxidation and to interfere with oxygen radical mediated activation of the pro-inflammatory transcription factor, NFκB; it also prevents glutathione depletion and up-regulates glutathione peroxidase (Hepgul et al., 2010). It remains to be determined if these actions contribute in the protective activity of pentoxifylline against NM-induced oxidative stress.

Whereas classically activated pro-inflammatory macrophages have been implicated in acute lung injury induced by pulmonary toxicants, alternatively activated anti-inflammatory macrophages are thought to contribute to wound repair, and under pathologic conditions, to fibrosis [reviewed in (Laskin et al., 2011)]. Following NM exposure, both of these cell populations appear in the lung, as shown by increased numbers of macrophages expressing COX-2 and MMP-9, markers of classically activated macrophages, and CD163 and Gal-3, markers of alternatively activated macrophages (Gibbons et al., 2011; Gong et al., 2012; Laskin et al., 2011; MacKinnon et al., 2008). The presence of CD163+ and Gal-3+ macrophages in the lung within 3 d of NM exposure indicates that tissue repair is initiated early in the response to vesicants. This is supported by our findings that Type II cells become activated and begin to proliferate at this time, as shown by increased expression of pro-SPC and PCNA, key responses associated with the repair of damaged epithelium (Lee et al., 2012; Mason, 2006). Interestingly, while pentoxifylline administration reduced COX-2+ and MMP-9+ macrophages in the lungs of NM treated animals, CD163+ and Gal-3+ macrophages increased. This suggests that pentoxifylline’s effectiveness in reducing NM-induced injury, inflammation and oxidative stress may be due, in part, to a shift in the phenotype of macrophages in the lung from pro-inflammatory/cytotoxic to anti-inflammatory/wound repair. This notion is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that pentoxifylline administration to mice blocks activation of NFκB, a key regulator of TNFα, and a major inducer of classically activated pro-inflammatory macrophages, as well as COX-2, which regulates pro-inflammatory eicosanoid production, and MMP-9, a proteolytic enzyme known to promote inflammation (Coimbra et al., 2006; Deree et al., 2006). Interestingly, BAL levels of the anti-inflammatory protein, CCSP, which were reduced following NM exposure, were largely unaffected by pentoxifylline, despite evidence of tissue repair, and the presence of increased numbers of anti-inflammatory/wound repair macrophages. Roflumistat, a specific phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, has been reported to restore CCSP levels in the lung after cigarette smoke exposure in mice (Ge et al., 2009). The fact that pentoxifylline had no major effect on NM-induced decreases in CCSP suggest that pathways unrelated to inhibition of phosphodiesterase may regulate production of CCSP in the lung following vesicant exposure.

The present studies demonstrate that NM-induced injury and inflammation is associated with PEEP-dependent increases in tissue damping and elastance in the lung. While the kinetics of derecruitment following a deep inflation were not significantly altered by NM, there was an absolute increase in both elastance and resistance parameters. These data indicate that the changes observed are inherent properties of the lung, and not changes in the dynamic components of respiration, such as surfactant. Therefore, it is likely that they result as a direct consequence of NM-induced injury, rather than an inflammatory response. In this context, it is not surprising that despite reducing NM-mediated inflammation, pentoxifylline has little effect on NM-mediated changes in pulmonary mechanics. Earlier studies have shown a protective effect of pentoxifylline against altered lung function induced experimentally by mechanical ventilation or recurrent airway obstruction, and in humans with sarcoidosis or after smoke inhalation (Aikawa et al., 2011; Leguillette et al., 2002; Ogura et al., 1994; Zabel et al., 1997). However, these studies focused on oxygenation and overall inflammatory cell recruitment to the lung. It remains to be determined if pentoxifylline improves the oxygenation index in NM-treated animals.

NM exposure involves both acute and chronic pathologic consequences in the lung. The present studies demonstrate that pentoxifylline attenuates acute lung injury, oxidative stress and inflammation induced by NM. Findings that this is associated not only with a reduction in pro-inflammatory macrophages, but an increase in anti-inflammatory/wound repair macrophages suggest a potential pathway contributing to its protective activity. Elucidating mechanisms underlying NM-induced injury and oxidative stress, and identifying novel inflammatory targets may lead to the development of more specific and effective drugs to treat pulmonary toxicity caused by vesicants.

Highlights.

NM causes lung injury, inflammation, and oxidative stress and impairs lung function

Pentoxifylline mitigates NM-induced lung injury, inflammation and oxidative stress

Reduced lung toxicity is associated with increases in anti-inflammatory macrophages

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank David Reimer (DVM, Laboratory Animal Services, Rutgers University) for performing NM instillations.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (grant numbers R01ES004738, R01CA132624, U54AR055073, P30ES05022 and HL086621).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aikawa P, Zhang H, Barbas CS, Pazetti R, Correia C, Mauad T, Silva E, Sannomiya P, Poli-de-Figueiredo LF, Nakagawa NK. The effects of low and high tidal volume and pentoxifylline on intestinal blood flow and leukocyte-endothelial interactions in mechanically ventilated rats. Respir Care. 2011;56:1942–1949. doi: 10.4187/respcare.01183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almario B, Wu S, Peng J, Alapati D, Chen S, Sosenko IR. Pentoxifylline and prevention of hyperoxia-induced lung -injury in neonatal rats. Pediatr Res. 2012;71:583–589. doi: 10.1038/pr.2012.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DR, Taylor SL, Fetterer DP, Holmes WW. Evaluation of protease inhibitors and an antioxidant for treatment of sulfur mustard-induced toxic lung injury. Toxicology. 2009;263:41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkhordari K, Karimi A, Shafiee A, Soltaninia H, Khatami MR, Abbasi K, Yousefshahi F, Haghighat B, Brown V. Effect of pentoxifylline on preventing acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery by measuring urinary neutrophil gelatinase - associated lipocalin. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;6:8. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-6-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae MK, Park SG, Song SO, Kang ES, Cha BS, Lee HC, Lee BW. Pentoxifylline attenuates methionine- and choline-deficient-diet-induced steatohepatitis by suppressing TNF-alpha expression and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Exp Diabetes Res. 2012;2012:762565. doi: 10.1155/2012/762565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coimbra R, Melbostad H, Loomis W, Porcides RD, Wolf P, Tobar M, Hoyt DB. LPS-induced acute lung injury is attenuated by phosphodiesterase inhibition: effects on proinflammatory mediators, metalloproteinases, NF-kappaB, and ICAM-1 expression. J Trauma. 2006;60:115–125. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000200075.12489.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colvin MHW. Alkylating agents and platinum antitumor compounds. In: Hong BRJWK, Hait WN, Kufe DW, Pollack RE, Weichselbaum RR, Holland JE, Frei E III, editors. Cancer Medicine. People’s Medical Publishing House; Shelton, CT: 2010. pp. 633–644. [Google Scholar]

- Day CP. Clinical spectrum and therapy of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Dig Dis. 2012;30(Suppl 1):69–73. doi: 10.1159/000341128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Campos T, Deree J, Martins JO, Loomis WH, Shenvi E, Putnam JG, Coimbra R. Pentoxifylline attenuates pulmonary inflammation and neutrophil activation in experimental acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2008;37:42–49. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181612d19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deree J, Lall R, Melbostad H, Loomis W, Hoyt DB, Coimbra R. Pentoxifylline attenuates stored blood-induced inflammation: A new perspective on an old problem. Surgery. 2006;140:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanda AD, Lee RW, Collins PL, McCune CA. Molecular targets in the treatment of alcoholic hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5504–5513. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i39.5504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar J, Pereda J, Arduini A, Sandoval J, Moreno ML, Perez S, Sabater L, Aparisi L, Cassinello N, Hidalgo J, Joosten LA, Vento M, Lopez-Rodas G, Sastre J. Oxidative and nitrosative stress in acute pancreatitis. Modulation by pentoxifylline and oxypurinol. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes JL, de Oliveira RT, Mamoni RL, Coelho OR, Nicolau JC, Blotta MH, Serrano CV., Jr Pentoxifylline reduces pro-inflammatory and increases anti-inflammatory activity in patients with coronary artery disease-a randomized placebo-controlled study. Atherosclerosis. 2008;196:434–442. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo JM, de Carmen Prado-Uribe M, Amato D, Paniagua R. Inflammation and oxidative stress markers by pentoxifylline treatment in rats with chronic renal failure and high sodium intake. Arch Med Res. 2007;38:34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge XN, Chu HW, Minor MN, Case SR, Bosch DG, Martin RJ. Roflumilast increases Clara cell secretory protein in cigarette smoke-exposed mice. COPD. 2009;6:185–191. doi: 10.1080/15412550902905979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons MA, MacKinnon AC, Ramachandran P, Dhaliwal K, Duffin R, Phythian-Adams AT, van Rooijen N, Haslett C, Howie SE, Simpson AJ, Hirani N, Gauldie J, Iredale JP, Sethi T, Forbes SJ. Ly6Chi monocytes direct alternatively activated profibrotic macrophage regulation of lung fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:569–581. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1719OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goicoechea M, Garcia de Vinuesa S, Quiroga B, Verdalles U, Barraca D, Yuste C, Panizo N, Verde E, Munoz MA, Luno J. Effects of pentoxifylline on inflammatory parameters in chronic kidney disease patients: a randomized trial. J Nephrol. 2012;25:969–975. doi: 10.5301/jn.5000077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong D, Shi W, Yi SJ, Chen H, Groffen J, Heisterkamp N. TGFbeta signaling plays a critical role in promoting alternative macrophage activation. BMC Immunol. 2012;13:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-13-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Espinoza L, Rojas-Campos E, Medina-Perez M, Pena-Quintero P, Gomez-Navarro B, Cueto-Manzano AM. Pentoxifylline decreases serum levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 6 and C-reactive protein in hemodialysis patients: results of a randomized double-blind, controlled clinical trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:2023–2028. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulati SC, Atzpodien J, Langleben A, Shimazaki C, Jain K, Yopp J, Ng RP, Colvin OM, Clarkson BD. Comparative regimens for the ex vivo chemopurification of B cell lymphoma-contaminated marrow. Acta Haematol. 1988;80:65–70. doi: 10.1159/000205604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepgul G, Tanrikulu S, Unalp HR, Akguner T, Erbil Y, Olgac V, Ademoglu E. Preventive effect of pentoxifylline on acute radiation damage via antioxidant and anti-inflammatory pathways. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:617–625. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0780-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoesel LM, Flierl MA, Niederbichler AD, Rittirsch D, McClintock SD, Reuben JS, Pianko MJ, Stone W, Yang H, Smith M, Sarma JV, Ward PA. Ability of antioxidant liposomes to prevent acute and progressive pulmonary injury. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:973–981. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskin DL, Sunil VR, Gardner CR, Laskin JD. Macrophages and tissue injury: agents of defense or destruction? Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011;51:267–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskin JD, Black AT, Jan YH, Sinko PJ, Heindel ND, Sunil V, Heck DE, Laskin DL. Oxidants and antioxidants in sulfur mustard-induced injury. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1203:92–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05605.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Hanaoka M, Kitaguchi Y, Kraskauskas D, Shapiro L, Voelkel NF, Taraseviciene-Stewart L. Imbalance of apoptosis and cell proliferation contributes to the development and persistence of emphysema. Lung. 2012;190:69–82. doi: 10.1007/s00408-011-9326-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leguillette R, Desevaux C, Lavoie JP. Effects of pentoxifylline on pulmonary function and results of cytologic examination of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in horses with recurrent airway obstruction. Am J Vet Res. 2002;63:459–463. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2002.63.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon AC, Farnworth SL, Hodkinson PS, Henderson NC, Atkinson KM, Leffler H, Nilsson UJ, Haslett C, Forbes SJ, Sethi T. Regulation of alternative macrophage activation by galectin-3. J Immunol. 2008;180:2650–2658. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaviya R, Sunil VR, Cervelli J, Anderson DR, Holmes WW, Conti ML, Gordon RE, Laskin JD, Laskin DL. Inflammatory effects of inhaled sulfur mustard in rat lung. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2010;248:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaviya R, Venosa A, Hall L, Gow AJ, Sinko PJ, Laskin JD, Laskin DL. Attenuation of acute nitrogen mustard-induced lung injury, inflammation and fibrogenesis by a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;265:279–291. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason RJ. Biology of alveolar type II cells. Respirology. 2006;11(Suppl):S12–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.00800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClintock SD, Hoesel LM, Das SK, Till GO, Neff T, Kunkel RG, Smith MG, Ward PA. Attenuation of half sulfur mustard gas-induced acute lung injury in rats. J Appl Toxicol. 2006;26:126–131. doi: 10.1002/jat.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClintock SD, Till GO, Smith MG, Ward PA. Protection from half-mustard-gas-induced acute lung injury in the rat. J Appl Toxicol. 2002;22:257–262. doi: 10.1002/jat.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus J, Huebner K. Vesicants. Journal. 2005;21:707–718. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay S, Rajaratnam V, Mukherjee S, Smith M, Das SK. Modulation of the expression of superoxide dismutase gene in lung injury by 2-chloroethyl ethyl sulfide, a mustard analog. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2006;20:142–149. doi: 10.1002/jbt.20128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muroski ME, Roycik MD, Newcomer RG, Van den Steen PE, Opdenakker G, Monroe HR, Sahab ZJ, Sang QX. Matrix metalloproteinase-9/gelatinase B is a putative therapeutic target of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and multiple sclerosis. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2008;9:34–46. doi: 10.2174/138920108783497631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura H, Cioffi WG, Okerberg CV, Johnson AA, Guzman RF, Mason AD, Jr, Pruitt BA., Jr The effects of pentoxifylline on pulmonary function following smoke inhalation. J Surg Res. 1994;56:242–250. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1994.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira-Junior IS, Oliveira WR, Cavassani SS, Brunialti MK, Salomao R. Effects of pentoxifylline on inflammation and lung dysfunction in ventilated septic animals. J Trauma. 2010;68:822–826. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181a5f4b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira-Junior IS, Pinheiro BV, Silva ID, Salomao R, Zollner RL, Beppu OS. Pentoxifylline decreases tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1 during high tidal volume. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2003;36:1349–1357. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2003001000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otterbein LE, Lee PJ, Chin BY, Petrache I, Camhi SL, Alam J, Choi AM. Protective effects of heme oxygenase-1 in acute lung injury. Chest. 1999;116:61S–63S. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.suppl_1.61s-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parameswaran N, Patial S. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha signaling in macrophages. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2010;20:87–103. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v20.i2.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz-Junior CM, Bessoni RL, Costa VV, Souza DG, Teixeira MM, Silva TA. Preventive and therapeutic anti-TNF-alpha therapy with pentoxifylline decreases arthritis and the associated periodontal co-morbidity in mice. Life Sci. 2013;93:423–428. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman I, Biswas SK, Kode A. Oxidant and antioxidant balance in the airways and airway diseases. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;533:222–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramallo BT, Lourenco E, Cruz RH, Almeida JC, Taha MO, Silva PY, Oliveira-Junior IS. A comparative study of pentoxifylline effects in adult and aged rats submitted to lung dysfunction by thermal injury. Acta Cir Bras. 2013;28:154–159. doi: 10.1590/s0102-86502013000200012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roudkenar MH, Kuwahara Y, Baba T, Roushandeh AM, Ebishima S, Abe S, Ohkubo Y, Fukumoto M. Oxidative stress induced lipocalin 2 gene expression: addressing its expression under the harmful conditions. J Radiat Res. 2007;48:39–44. doi: 10.1269/jrr.06057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryter SW, Kim HP, Nakahira K, Zuckerbraun BS, Morse D, Choi AM. Protective functions of heme oxygenase-1 and carbon monoxide in the respiratory system. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:2157–2173. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saladi RN, Smith E, Persaud AN. Mustard: a potential agent of chemical warfare and terrorism. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2005.01945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan D, Wu HM, Yuan QY, Li J, Zhou RL, Liu GJ. Pentoxifylline for diabetic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD006800. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006800.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidhu SS, Goyal O, Singla M, Bhatia KL, Chhina RS, Sood A. Pentoxifylline in severe alcoholic hepatitis: a prospective, randomised trial. J Assoc Physicians India. 2012;60:20–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunil VR, Patel-Vayas K, Shen J, Gow AJ, Laskin JD, Laskin DL. Role of TNFR1 in lung injury and altered lung function induced by the model sulfur mustard vesicant, 2-chloroethyl ethyl sulfide. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2011a;250:245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunil VR, Patel KJ, Shen J, Reimer D, Gow AJ, Laskin JD, Laskin DL. Functional and inflammatory alterations in the lung following exposure of rats to nitrogen mustard. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2011b;250:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunil VR, Shen J, Patel-Vayas K, Gow AJ, Laskin JD, Laskin DL. Role of reactive nitrogen species generated via inducible nitric oxide synthase in vesicant-induced lung injury, inflammation and altered lung functioning. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;261:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turhan AH, Atici A, Muslu N, Polat A, Helvaci I. The effects of pentoxifylline on lung inflammation in a rat model of meconium aspiration syndrome. Exp Lung Res. 2012;38:250–255. doi: 10.3109/01902148.2012.676704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venugopal C, Mariappan N, Holmes E, Kearney M, Beadle R. Effect of potential therapeutic agents in reducing oxidative stress in pulmonary tissues of recurrent airway obstruction-affected and clinically healthy horses. Equine Vet J. 2013;45:80–84. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.2012.00566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger B, Laskin JD, Sunil VR, Sinko PJ, Heck DE, Laskin DL. Sulfur mustard-induced pulmonary injury: therapeutic approaches to mitigating toxicity. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2011;24:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigenstam E, Jonasson S, Koch B, Bucht A. Corticosteroid treatment inhibits airway hyperresponsiveness and lung injury in a murine model of chemical-induced airway inflammation. Toxicology. 2012;301:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2012.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong AP, Keating A, Waddell TK. Airway regeneration: the role of the Clara cell secretory protein and the cells that express it. Cytotherapy. 2009;11:676–687. doi: 10.3109/14653240903313974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabel P, Entzian P, Dalhoff K, Schlaak M. Pentoxifylline in treatment of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1665–1669. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.5.9154873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaitone S, Hassan N, El-Orabi N, El-Awady el S. Pentoxifylline and melatonin in combination with pioglitazone ameliorate experimental non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;662:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zein CO, Lopez R, Fu X, Kirwan JP, Yerian LM, McCullough AJ, Hazen SL, Feldstein AE. Pentoxifylline decreases oxidized lipid products in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: new evidence on the potential therapeutic mechanism. Hepatology. 2012;56:1291–1299. doi: 10.1002/hep.25778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]