Summary

Background

Psychotherapy is not routinely recommended for in ulcerative colitis (UC). Gut-directed hypnotherapy (HYP) has been linked to improved function in the gastrointestinal tract and may operate through immune-mediated pathways in chronic diseases.

Aims

To determine the feasibility and acceptability of hypnotherapy and estimate the impact of hypnotherapy on clinical remission status over a 1 year period in patients with an historical flare rate of 1.3 times per year.

Methods

54 patients were randomized at a single site to 7 sessions of gut-directed hypnotherapy (N = 26) or attention control (CON; N = 29) and followed for 1 year. The primary outcome was the proportion of participants in each condition that had remained clinically asymptomatic (clinical remission) through 52 weeks post-treatment.

Results

One-way ANOVA comparing hypnotherapy and control subjects on number of days to clinical relapse favored the hypnotherapy condition [F = 4.8 (1, 48), p = .03] by 78 days. Chi square analysis comparing the groups on proportion maintaining remission at 1 year was also significant [X2(1) = 3.9, p = .04], with 68% of hypnotherapy and 40% of control patients maintaining remission for 1 year. There were no significant differences between groups over time in quality of life, medication adherence, perceived stress or psychological factors.

Conclusions

This is the first prospective study that has demonstrated a significant effect of a psychological intervention on prolonging clinical remission in patients with quiescent UC.

Clinical Trial # NCT00798642

Keywords: ulcerative colitis, hypnotherapy, remission, inflammatory bowel disease, psychological treatment

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis affects approximately 220 per 100,000 patients in the United States 1,2 and is associated with painful and unpredictable symptoms, undesirable psychosocial consequences3 and disability, particularly during periods of disease flare 4–7. Medical treatment is focused on prolonging remission and reducing exposure to environmental triggers of flare8. Psychosocial research in UC has been limited to survey studies characterizing co-morbid anxiety or depression in the setting of disease 9 or cross-sectional studies linking stressful experiences to the onset of disease flares10,11. However, the prevalence of psychological disorders in patients with UC mirrors that of the general population, particularly during quiescent disease states 12,13, and thus psychotherapy is not routinely recommended14.

Hypnotherapy, one of the first psychological therapies to be implemented in medical populations, has been linked to positive outcomes in a number of chronic diseases such as cancer 15–17, rheumatoid arthritis18, HIV19,20, fibromyalgia21,22 and chronic pain 23,24. Mechanistic studies suggest that hypnotherapy can have positive effects on immune parameters, with data supporting the effects of hypnotherapy on T-cell expression of interferon-gamma and interleukin-225, increases in secretory immunoglobulin-A and neutrophil adherence 26 and reductions in inflammatory markers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate, c-reactive protein and leukocyte activity 18. Hypnotherapy used in inpatient medical settings has been associated with shorter length of hospital stays, decreased need for pain medication27,28, more rapid recovery from surgery 29 and faster wound healing 30–32.

Gut-directed hypnotherapy is a form of medical hypnosis that draws upon metaphors and delivers post-hypnotic suggestions specific to the improved health and function of the gastrointestinal tract. Hypnotherapy has demonstrated efficacy in several gastrointestinal disorders [see Palsson, 2010 33 for a review], with treatment gains maintained up to 5 years 34. Gut-directed hypnotherapy is well-tolerated and effective in irritable bowel syndrome 34–36, functional dyspepsia37,38, non-cardiac chest pain 39, delayed gastric emptying40 and relapse prevention for duodenal ulcer41.

Limited data are available on the use of gut-directed hypnotherapy in inflammatory bowel diseases, with most research in this area limited to small, uncontrolled case series 42–46. One particularly compelling study demonstrated that patients with active UC who underwent a single session of gut-directed hypnotherapy reduced mucosal release of substance P, histamine, and interleukin-13 and serum levels of interleukin-6 46, suggesting that hypnotherapy could have a disease-modifying impact on UC. We have previously reported on the preliminary findings from the Ulcerative Colitis Relapse Prevention Trial (UCRPT), an NIH-funded randomized controlled trial comparing gut-directed hypnotherapy to a time and attention control group in quiescent UC in which a 7-session gut-directed hypnotherapy program demonstrated improvement in health related quality of life, including reduction of bowel and systemic UC symptoms (IBDQ) and increased disease-specific self-efficacy immediately post-treatment and at 3 month follow-up 47.

UCRPT completed data acquisition in April, 2012 and we now report the results of our primary scientific question—can participation in a brief gut-directed hypnotherapy program prolong clinical remission among patients with quiescent UC? Our hypothesis was that hypnotherapy would be superior to control on two endpoints—1. the proportion of patients at 52 weeks who were still clinically asymptomatic and 2. number of days to first relapse.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

UCRPT was a prospective, single site randomized clinical trial comparing gut-directed hypnotherapy (HYP) against an active control condition (CON) on the primary outcome variable, which was the proportion of UC patients who remained clinically asymptomatic (no rectal bleeding, no diarrhea/ urgency or requirements to increase medication) through 1 year follow-up. Repeated assessments of disease status (patient and physician), self-efficacy and quality of life were administered at baseline, 2 weeks post treatment, 20 weeks, 36 weeks and 52 weeks post-treatment. This clinical trial was registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov/NCT00798642.

Participants

Male and female patients (ages 18 to 70), who were in remission, with endoscopy confirmed mild or moderately severe ulcerative colitis were invited to participate. Remission at the time of enrollment was operationally defined by a Mayo Score < 2 with no subscale > 1, and no rectal bleeding in last 2 weeks. We included only those patients who had a self-reported flare rate of > 1 per year and a documented disease flare within the past 1.5 years to enhance the opportunity to observe differences between groups over the course of a 1-year trial. As such, we expected to see primarily left-sided ulcerative colitis and some pancolitis with significant fewer patients with proctitis qualifying. Patients were required to be on a stable dose of maintenance medication (i.e. mesalamine or sulfasalazine) for at least one month prior to enrollment and could not have taken oral steroids within the past 30 days or topical steroids within the past 7 days. Exclusion criteria included any markers of active disease, a history of severe/fulminant UC, and other gastrointestinal disorders that could explain symptoms (e.g. Crohn’s disease, indeterminate colitis, short-bowel syndrome, renal/hepatic disease, Clostridium difficile infection, irritable bowel syndrome), pregnancy or intention to become pregnant in the next year, smoking cessation within the past 30 days, a prior history with hypnotherapy as well as any of the common contraindications for hypnotherapy 48. We based sample size calculations on our previous research in this area—50 participants spread across two conditions is minimally acceptable (80% power) to detect an OR of 3.8 47,49.

Interventions

Both interventions were standardized and conducted on an individual, outpatient basis at a tertiary clinic in an academic medical center. Gut-directed hypnotherapy (HYP) is a 7-session standardized treatment protocol delivered by 1 of 2 trained health psychologists (LK, JLK) in weekly, 40-minute sessions (Figure 2 for sample hypnotic suggestion). Sessions were fully scripted to ensure uniformity across therapists. Patients were provided a self-hypnosis audio recording to practice outside of clinic 5 times per week during the study and then as they chose through follow-up 47. The control condition (CON) consisted of non-directive discussion about UC and “the mind-body connection” with a separate post- doctoral fellow (MK). The therapist avoided any in-depth discussions of hypnotherapy or relaxation techniques to ensure difference from the experimental condition. Notably, the control treatment was not inert—participants were able to ask questions around disease self-management of their therapist, and the therapist would point participants towards up-to-date information on behavioral self-management of IBD without directly encouraging behavior change. This treatment was previously validated as a credible intervention that controlled for time and clinical attention. Hypnotherapists were randomized on a 2:1 ratio (JLK:LK). Randomization allocation software was provided by the statistician (ZM) and the study coordinator enrolled and assigned participants to treatment. While blinding of the therapists or participants to the intervention was not possible, participants were blinded to study hypothesis and gastroenterologists were blinded to the treatment the participant’s received (HYP or CON). Participants were told that the goal of the study was to determine if behavioral therapies are an effective complementary therapy for IBD and that they would be assigned to one of two therapies: gut-directed hypnotherapy or a mind-body therapy aimed at identifying the impact of UC on the psyche and vice versa.

Figure 2.

Example post-hypnotic suggestion from trial

To ensure participants were blind to hypothesis, we administered the 10 point Expectancy and Credibility Questionnaire (1 not credible, 10 completely credible) after session 1. The mean score for the HYP group was 7.5 (0.9; 6–9) and the experimental group was 7.1 (1.5; 5–9) demonstrating that each therapy was presented in an engaging and credible manner. We used separate therapists for the two conditions to reduce the effect of therapist allegiance, or the tendency for a therapist to unknowingly “water down” a treatment they do not necessarily believe is effective, on outcome 50. To further reduce the potential bias of not being able to blind participants or providers, all follow-up assessments were done online immediately prior to the patient’s “booster session” with the therapist. We also asked the patients not to share with their physicians the type of treatment they received until the end of the trial so as not to influence expectancy.

Measurement: Disease State

The primary outcome measure was the proportion of participants in each treatment group that were still in remission at 52 weeks post treatment. We used several subjective markers of flare given the absence of endoscopy:

Baseline Sociodemographic and Clinical Information

Participants were asked to report several demographic and illness-related variables including disease duration, medication regimen, smoking, CAM use and medical history.

Daily Symptom Diaries

Participants completed an online time and date stamped standard symptom diary daily using a secure, password protected website during the 2-week baseline period and throughout treatment. The diaries asked patients to report on the presence and severity of rectal bleeding [referring to the most severe episode of the day on a scale of 0 (mild) to 3 (severe)], the number of stools during the day and the presence and severity of abdominal pain or discomfort (same scale 0–3) and general well-being [0 (generally well) to 3 (poor)]. The diary was also re-assigned in 2-week periods prior to each repeated assessment interval to confirm remission status.

Flare Worksheet

Participants were instructed to complete this form at the first sign of a flare regardless of whether they were currently in one of the 2 week assessment intervals for UCRPT. The form was accessible online and asked participants to identify the date they first noticed symptoms, note the presence and frequency of rectal bleeding, average # of bowel movements per day since start of flare, average rating of abdominal pain since start of flare, general well-being and free text describing the situation. When completed, an alert was triggered to the study coordinator who was able to follow-up for additional details.

Modified Mayo Score

The Mayo Scoring System for the Assessment of UC activity is a 12-point scale that reflects the physician’s clinical opinion of disease activity at each assessment interval. It was modified in this Phase I/II a study to exclude endoscopy results. This decision was based on factor analysis which revealed that other items included in disease activity indices (rectal bleeding, stool frequency/urgency) made the histological findings obtained on endoscopy redundant, with endoscopy accounting for less than 1% of the variance in predicting disease activity scores 51.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ)52

Participants completed the 32-item version of the well- validated questionnaire to assess disease severity and quality of life in IBD, yielding four subscale scores: bowel health, systemic health, emotional functioning, and social functioning.

Morisky Medication Adherence Scale 53

Non-adherence to medication was assessed with a validated, 4-item questionnaire and allowed us to track adherence in the study to control for the effects of adherence to maintenance medications on relapse.

Measurement: Psychological questionnaires

Psychiatric comorbidity was assessed during the intake interview and participants with a psychiatric diagnosis (e.g. depression, bipolar disorder, panic disorder) were not included in this trial in order to maintain as much homogeneity as possible and reduce the possibility that the treatment worked through change in psychiatric symptoms.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease Self-Efficacy Scale (IBD-SES)

Drawn from social-cognitive theory, self-efficacy is an individual’s personal beliefs about their ability to engage in a certain behavior/set of behaviors and has been linked to healthy outcomes in a host of chronic diseases. Disease-specific self-efficacy reflects a person’s individual belief in his/her ability to manage IBD. Participants completed a 29-item validated disease-specific self-efficacy measure54 with 4 subscales: managing stress and emotions, managing medical care, managing symptoms and disease, and maintaining remission.

Perceived Stress Questionnaire-Recent (PSQ)55

The PSQ-Recent is a 30-item validated measure of stress in the past month across 7 factors: harassment, overload, irritability, lack of joy, fatigue, worries, and tension. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale from “almost never” to “usually.” Higher scores suggest greater perceived stress. Norms have been previously reported in IBD 56.

Short Form 12 Health Survey Version 2 (SF-12v2)57

The SF-12v2 includes 12 items from the Short-Form 36 Health Survey58 and yields a physical and mental composite score. Lower scores correspond with poorer general health-related quality of life.

Determination of Flare

Conservative estimates of flare occurrences were used. Patients were considered to have had a disease flare if any of the following were met: 1) patient completed the flare worksheet (N = 15), 2) Modified Mayo Score >2 or subscale was >1 at time of an assessment or self-reported flare (N = 10); 3) patient self-reported a flare as rectal bleeding > 2 days with no other symptoms between assessment periods (N = 5); or 4) a patient’s therapy was escalated to include oral or topical steroids at any point in the 12 months or a new class of medications was added (N = 8). Once a flare occurred, we recorded the date it was first reported/described to quantify the total number of days between study enrollment and time of flare. If a flare was not reported during the 12 month follow-up period and if we were unable to quantify time to the first flare, we recorded 366 days (1 year + 1 day) to flare (censored).

Maintenance of Remission

We defined continued clinical remission at 52 weeks as the absence of flare (defined above) during the 1 year follow-up phase. While there has been recent emphasis on the use of mucosal healing as the “gold standard” determinant of remission, the study was designed during a period of time where patient-centered reports of clinical remission were of similar utility to endoscopic indices 51,59. Indeed, Higgins et al suggested that unless a patient considers him/herself to be in remission, s/he is still likely to experience impairment, poor quality of life and high health use. Thus, the participant or his/her physician could not have reported a flare, defined above, at any of the previous follow-ups, or during the interval between week 36 and week 52. Participants were categorized at the 52 week follow- up according to the primary outcome variable: continued remission at week 52 (yes/no).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were completed using SPSS 20.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL). ANOVA and chi-square tests were performed on baseline demographic and disease variables. There were no dropouts during active treatment in either condition, so intent-to-treat procedures were unnecessary. When possible, a worst case carried forward approach was employed for missing data. For example, if the patient did not have data at 1 year, they were assumed to have flared during the 52 week trial period. This approach left us with 3 participants whose data was too unreliable to include in the analysis and 1 participant who withdrew consent. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to assess differences in days to flare for subjects in HYP versus CON. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was performed to determine differences between the 2 groups on number of days to flare. Chi-square test was used to evaluate differences between groups in the proportion of individuals who had flared by one year. Multivariate analyses of variance were performed to determine changes in psychological questionnaire data over time [baseline, post-treatment, 20 weeks, 36 weeks, 52 weeks].

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Northwestern University. All co-authors had access to the study data and have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Results

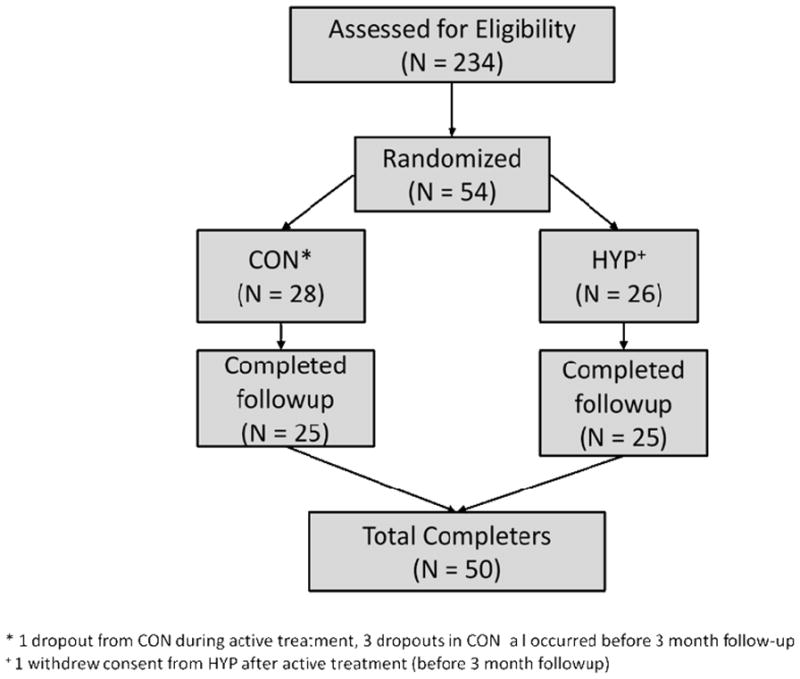

Participants were recruited over a 3-year period, from March, 2008 through Feb, 2011. There were no adverse effects in either treatment condition. See Figure 1 for CONSORT-NP statement. Of the 234 patients assessed for eligibility, 54 were randomized. Twenty participants were excluded from the 234 because of a contraindication to hypnotherapy (10 for objection to hypnosis for religious purposes, 8 for unresolved trauma histories, 2 for history of mania/psychosis), another 20 were excluded for refusal to be randomized and 90 were excluded due to active disease, steroid use, smoking or other medical exclusion criteria. Four patients were excluded because of psychiatric disorder. Forty-eight patients (90%) had left sided colitis of mild to moderate severity 6 had pancolitis. All patients were in clinical remission at the time of enrollment.

Figure 1. CONSORT Table for UCRPT.

*1 dropout from CON during active treatment, 3 dropouts in CON a I occurred before 3 month follow-up

+1 withdrew consent from HYP after active treatment (before 3 month followup)

Fifty (50) patients (93%) were considered at 1 year follow-up (25 HYP, 25 CON). There were no differences between patients who followed up vs. failed to follow-up on demographic or clinical variables. The mean age of the sample was 38 years [range 18 to 65] with average disease duration of 9.5 years [range 1.5 to 35y].

Participants were 54% female, 86% white, non-Hispanic, 56% married and 75% with a college degree. One third reported a prior history of smoking but no participants had smoked within the last 2 years. Sixteen percent reported a positive family history of IBD. Seventy percent endorsed 5ASA use and 18% reported current azathiopurine use. None of the patients were currently using a biologic agent and 15% had a history of azathiopurine use. Only 2 participants reported no maintenance medication use. Sixty-four percent reported a history of oral steroid use in the last 1.5 years. Participants reported an average of 1.29 flares per year [range 1 to 5] with an average duration of flare of 6.3 weeks (SD=5.4), [range 1–24]. The median number of days since last flare was 100 (19, 55–144). Baseline symptom diaries suggested that participants, who were all in remission, had an average of 3 bowel movements per day, mild daily abdominal pain/discomfort and excellent to good well-being. See Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline and demographic characteristics of patients by condition.

| Variable | Hypnotherapy (N = 25) | Attention Control (N = 25) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 56% female (N = 14) | 52% female (N = 13) |

| Race | 84% white (N = 21) | 88% white (N = 22) |

| Ethnicity | 4% non-white Hispanic (N = 1) | 4% non-white Hispanic (N = 1) |

| Marital status | 48% married/life partner (N = 12) | 64% married/life partner (N = 16) |

| Education | 86% college degree or higher (N = 19) | 68% college degree or higher (N = 17) |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Age | 38.7 (11.8) | 38.8 (12.1) |

| disease duration (y) | 9.38 (7.95) | 9.96 (6.73) |

| Disease extent | 84% (N = 21) left sided colitis, 16% (N = 4) pancolitis | 88% (N = 22) left sided colitis, 12% (N = 3) pancolitis |

| # BM/day | 3.1 (.88) | 3.3 (1.4) |

| Abdominal pain | 1.3 (.43) | 1.3 (.46) |

| Well-being | 1.21 (.37) | 1.2 (.54) |

| # flares per year | 1.29 (.46) | 1.29 (.46) |

| days since last flare | 102.6 (20.8, 60–144) | 99.2 (18.9, 55–136) |

| +5ASA use (current) | 18 (72%) | 17 (68%) |

| + azathioprine/mercaptopurine use (current) | 4 (16%) | 5 (20%) |

| Duration of last flare (weeks) | 6.1 (4.9, 1–16) | 6.6 (6.0, 0.1–24) |

| + History of smoking | 8(32%) | 7 (28%) |

| + fam history of IBD | 5 (20%) | 3 (12%) |

No differences between groups on any variables. All patients were in remission at the time of enrollment.

Overall baseline IBDQ score was 191 (SD=19.8), reinforcing remission status and a good disease-specific quality of life estimate.

Remission status by group

A one-way ANOVA comparing HYP and CON on number of days to relapse favored the HYP condition [F = 4.8 (1, 48), p = .03] by 78 days. Chi square analysis comparing the two groups on proportion who maintained remission at 1 year was also significant [X2(1) = 3.9, p = .04] with 68% of HYP patients and 40% of CON patients maintaining remission for 1 year. See Table 2. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to assess differences in days to flare for subjects in HYP vs. CON. Overall, the risk of flare was estimated to be 2.11 times greater in the CON vs HYP; however this result was not statistically significant (Wald Chi-square=2.87, p=.090).

Table 2.

Changes in primary outcome measures at 1 year.

| Variable | Hypnotherapy (N = 25) Mean (SD) |

Attention Control (N = 25) Mean (SD) |

Test Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Days to relapse | 359.4 (145.9) | 281.8 (100.5) | t = 2.1 (1, 48), p = .03 |

| Proportion still in remission at 1 year | 17 (68%) | 10 (40%) | X2 (1) = 3.9, p = .04 |

| IBDQ | ↑2.3 (24.1) | ↓7.9 (20.7) | t (1,48) = .24, p = ns |

Twenty-three patients flared during the study. There was one flare in a CON participant at 3 month follow-up. By 6 month follow-up, 10 CON and 5 HYP had flared, and by 12 month follow-up 15 CON and 8 HYP had flared. Of those patients who flared, 15/23 (5 HYP, 10 CON) reported it via the flare worksheet between assessment intervals and 10 of these were also confirmed by physician’s Modified Mayo Score (2 HYP, 8 CON). The additional 8 participants who flared but did not complete a worksheet were identified through the medical record as requiring an escalation in therapeutic dose (3 HYP, 5 CON). Five/23 participants who flared reported rectal bleeding >2 days as their sole indicator of flare (3 HYP, 2 CON) but were not confirmed to have flared by the medical record or physician Mayo rating. Of those patients who flared, 22% (5) were stepped up from 5ASA only to azathioprine/mercaptopurine and 30% (7) had an escalation in 5ASA use. Nineteen percent (4) required oral steroid use at time of flare. There was no significant difference between groups in approach to flare. We were not powered to detect impact of hypnotherapy on flare characteristics.

There were no main effects or group X time interaction effects for any of the psychological questionnaires at 1 year follow-up F = 1.4(24, 16), p = .28 [Table 3a and b].

Table 3a.

Changes in psychological variables over time, hypnotherapy group

| Variable | Hypnotherapy (N=25) Mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Baseline | Post Tx | Week 20 | Week 36 | Week 52 | |

|

|

|||||

| IBDQ Perceived | 187.5 (22.4) | 190.0 (22.5) | 189.7 (25.2) | 184.1 (24.7) | 185.2 (26.0) |

| Stress Self - | 36.4 (14.4) | 33.1 (18.1) | 33.1 (18.1) | 35.6 (17.4) | 34.8 (16.0) |

| Efficacy SF12 | 212.8 (48.5) | 221.5 (48.6) | 221.8 (54.6) | 225.7 (43.6) | 218.7 (56.8) |

| MCS | 44.9 (10.9) | 48.4 (11.1) | 48.0 (9.4) | 45.8 (11.3) | 45.6 (12.2) |

| SF12 PCS | 52.3 (6.8) | 53.6 (4.6) | 53.2 (4.8) | 54.3 (5.3) | 53.8 (4.9) |

Table 3b.

Changes in psychological variables over time, attention control group

| Variable | Attention Control (N=25) Mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Baseline | Post Tx | Week 20 | Week 36 | Week 52 | |

|

|

|||||

| IBDQ Perceived | 181.8 (20.7) | 186.7 (22.2) | 188.8 (18.8) | 188.9 (20.9) | 189.7 (20.6) |

| Stress Self - | 37.2 (14.3) | 34.3 (12.3) | 33.5 (12.3) | 31.7 (14.2) | 30.7 (12.1) |

| Efficacy SF12 | 203.4 (40.6) | 204.7 (43.4) | 208.8 (38.4) | 208.6 (39.2) | 216.2 (38.1) |

| MCS | 44.6 (9.5) | 48.3 (5.9) | 44.7 (8.7) | 46.2 (8.2) | 46.8 (7.7) |

| SF12 PCS | 52.3 (6.8) | 52.6 (8.2) | 53.4 (8.2) | 53.5 (8.4) | 53.0 (9.2) |

We also monitored adherence to recommended weekly, at-home practice and at 1-year follow-up, 52% of the HYP group was practicing self-HYP at least once per week.

Discussion

This is the first prospective study to our knowledge that has reported a demonstrable effect of a psychological intervention in prolonging remission in patients with quiescent UC. We found that hypnotherapy prolonged remission by a very conservative estimate of approximately 2.5 months, which is likely to be a clinically and subjectively significant benefit of the therapy considering that these patients had a pre-intervention annual flare rate of 1.3.

There are several strengths to this study. Participants were selected based on a flare rate of >1 per year and were “primed” for flare in that eligibility criteria required a documented disease flare within the past 18 months, making it more likely that they would flare during the course of the 1 year follow-up period. However, the average flare rate still fell within 1–2 per year. Thus, it is significant that 68% of the hypnotherapy group did not flare during the year post- treatment, contrary to the 40% seen in the time-attention control group. It is also important to note that the control group in this study was a one-on-one verbal intervention provided by a doctoral level therapist, not simply routine care. Comparing our intervention to wait-list (treatment as usual), while less rigorous, would likely have yielded more stunning results. Indeed, we have previously demonstrated that there is some immediate benefit on risk of flare derived from an active placebo condition 49. Furthermore, we did not detect a difference in treatment expectancy at baseline, suggesting that both treatments were presented with strong rationale.

That we were able to detect a difference between groups followed prospectively over 1 year with only 50 participants suggests that hypnotherapy is likely to be an effective complementary intervention in patients with mild to moderate UC, especially in contrast to no intervention, which is currently what patients receive in IBD centers. Furthermore, the majority of participants were practicing self-HYP on their own at one year, supporting its potential for sustainability and self-management therapeutic benefit even when a health psychologist is not readily available. Our results mirror IBD patient’s positive attitudes about the use of complementary and alternative therapies in IBD60. Finally, the fact that the hypnotherapy followed a standardized scripted protocol means that the same precise therapeutic components were delivered to all patients, and also that this intervention can easily be replicated, further tested and applied in clinical care by other groups.

Only 52% of the participants engaged in home practice of the hypnosis audio file, yet there was no relation between practice and no practice in terms of flare outcome. Previous research has shown lasting effects of gut-directed hypnotherapy (up to 7 years) on bowel symptoms, motility, abdominal pain and visceral hypersensitivity in functional gastrointestinal problems 33,61,62. Mechanisms proposed for these findings include cognitive change around the meaning of symptoms, improved motility and improved pain tolerance 62–64. Similarly, enduring effects of hypnotherapy have been attributed to learning that occurs occurring at the neurophysiological level; this has been linked to depth of trance 65 and type and ease of suggestion 66 and may be interesting for future research. Less is known about long-term benefits of hypnosis in chronic autoimmune conditions, but it is possible that increased awareness of body processes, improved self-care after participating in a program during remission and strengthening of the immune system more generally may explain some of the long-term effects of hypnotherapy noted in this study. Finally, recent support for the importance of brain-gut interactions in the clinical expression of IBD67 is highly compatible with our complementary approach to treatment—to the extent that gut-directed hypnotherapy has been shown to modify brain-gut pathways and visceral hypersensitivity in functional gastrointestinal disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome68, it is possible that our intervention could impact IBD disease outcomes in a similar manner.

It is unlikely that patients participated in this study because of psychological distress—indeed our patient population did not evidence any clinically significant depression, anxiety or stress at the time of study entry, which is consistent with other reports of psychological characteristics of patients with quiescent UC. The IBDQ, a well-recognized index of disease specific quality of life 69 did not change with treatment in our group, likely because it is of limited value when patients are in remission at baseline70; differences in quality of life over time were not detectable, even in the group with a higher flare rate. Finally, rate of adherence to medication did not differ over time between the two groups, so adherence does not explain the difference in remission status over the course of 1 year.

We acknowledge a few important limitations to the study. First, we did not confirm flare and remission status endoscopically and instead relied on clinical symptoms, corroborated through daily symptom diaries, medical records, and patient and physician report. Inflammation has been shown to be present when clinical symptoms are absent in UC 71 and mucosal healing is gaining acceptance as an endpoint in clinical trials 72. We wish we had been able to use fecal calprotectin as a biomarker of flare or risk to flare for this study—at the time the NIH grant was awarded, this biomarker was still quite novel and expensive and not feasible for a pilot trial. Indeed, recent data suggests that high levels of perceived stress may contribute to higher symptom burden without altering fecal calprotectin levels, underscoring the importance of both objective and subjective markers of flare73. We cannot draw any conclusions on the mechanism through which hypnotherapy may have prolonged remission in this study, which highlights an interesting area for future research. Secondly, our patient population may not be representative of the typical UC patient seen in clinical practice—we are a tertiary care center with an integrated behavioral medicine and nutrition program and therefore our patients may be more motivated to participate in this type of research. An important next step in this line of inquiry would be a multi-center trial with a range of care settings and patient phenotypes. Finally, because the lead author served as a therapist in the hypnotherapy condition, it is possible that researcher allegiance impacted the outcome50. Unfortunately, at the time of the study, the lead author was also one of the few individuals qualified to provide the therapy. That said, the hypnotherapy was well-scripted and therefore it would have been difficult to impose considerable expectancy onto the individual patient. Future, multi-center trials could address this by training therapists.

If gut-directed hypnotherapy is effective in augmenting the time patient’s spend in clinical remission for even a portion of patients with UC, this would have marked clinical significance for the conventional management of IBD. This intervention may prove particularly useful for the large number of patients who have high rates of flare, difficulty obtaining remission, who become steroid dependent, or are otherwise resistant to maintenance medications.

Summary

This paper reports on an NIH funded RCT of gut-directed hypnotherapy in quiescent UC [NCT00798642]. The primary aims were to determine the feasibility and acceptability of hypnotherapy and estimate the impact of hypnotherapy on clinical remission status over a 1 year period in patients with an historical flare rate of 1.2 times per year. This is the 1 year follow-up paper reporting on the impact of hypnotherapy on relapse. We found that patients receiving hypnotherapy were able to prolong clinical remission by 78 days, with 68% of HYP patients and 40% of CON patients maintaining remission for 1 year.

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health R21AT0032004, clinical trial # NCT00798642

We also thank Monika Kwiatek, PhD for her assistance with the control condition, Edward Loftus, MD for his assistance with the choice of outcome measures, Rachel Lawton for her assistance with final chart review and all of the participants for their commitment to the project.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors has a conflict of interest relevant to this trial.

Author Roles:

All co-authors had access to the study data and had reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

LK: study concept and design, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, manuscript preparation, statistical analysis, obtained funding, study oversight

TT: data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, manuscript preparation

JLK: primary therapist, data acquisition, administrative support and manuscript revision

TAB: study concept and design, subject recruitment and retention, medical oversight

ZM: study concept and design, statistics, analysis, interpretation of data

OP: study concept and design, development and oversight of the hypnotherapy intervention, critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content

References

- 1.Loftus CG, Loftus EV, Jr, Harmsen WS, et al. Update on the incidence and prevalence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940–2000. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2007;13:254–61. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, et al. The prevalence and geographic distribution of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2007;5:1424–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waljee AK, Joyce JC, Wren PA, Khan TM, Higgins PD. Patient reported symptoms during an ulcerative colitis flare: a Qualitative Focus Group Study. European journal of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2009;21:558–64. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328326cacb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Cieza A, Sandborn WJ, et al. Development of the first disability index for inflammatory bowel disease based on the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Gut. 2012;61:241–7. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Achleitner U, Coenen M, Colombel JF, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sahakyan N, Cieza A. Identification of areas of functioning and disability addressed in inflammatory bowel disease-specific patient reported outcome measures. Journal of Crohn’s & colitis. 2012;6:507–17. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abraham BP, Sellin JH. Disability in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology clinics of North America. 2012;41:429–41. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reinisch W, Sandborn WJ, Bala M, et al. Response and remission are associated with improved quality of life, employment and disability status, hours worked, and productivity of patients with ulcerative colitis. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2007;13:1135–40. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernstein CN, Singh S, Graff LA, Walker JR, Miller N, Cheang M. A prospective population-based study of triggers of symptomatic flares in IBD. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2010;105:1994–2002. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker JR, Ediger JP, Graff LA, et al. The Manitoba IBD cohort study: a population-based study of the prevalence of lifetime and 12-month anxiety and mood disorders. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2008;103:1989–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keefer L, Keshavarzian A, Mutlu E. Reconsidering the methodology of “stress” research in inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Crohns & Colitis. 2008;2:193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maunder RG, Levenstein S. The role of stress in the development and clinical course of inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiological evidence. Current molecular medicine. 2008;8:247–52. doi: 10.2174/156652408784533832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rogala L, Miller N, Graff LA, et al. Population-based controlled study of social support, self-perceived stress, activity and work issues, and access to health care in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2008;14:526–35. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graff LA, Walker JR, Clara I, et al. Stress coping, distress, and health perceptions in inflammatory bowel disease and community controls. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2009;104:2959–69. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.von Wietersheim J, Kessler H. Psychotherapy with chronic inflammatory bowel disease patients: a review. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2006;12:1175–84. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000236925.87502.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen MP, Gralow JR, Braden A, Gertz KJ, Fann JR, Syrjala KL. Hypnosis for symptom management in women with breast cancer: a pilot study. The International journal of clinical and experimental hypnosis. 2012;60:135–59. doi: 10.1080/00207144.2012.648057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hudacek KD. A review of the effects of hypnosis on the immune system in breast cancer patients: a brief communication. The International journal of clinical and experimental hypnosis. 2007;55:411–25. doi: 10.1080/00207140701506706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sohl SJ, Stossel L, Schnur JB, Tatrow K, Gherman A, Montgomery GH. Intentions to use hypnosis to control the side effects of cancer and its treatment. The American journal of clinical hypnosis. 2010;53:93–100. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2010.10404331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horton-Hausknecht JR, Mitzdorf U, Melchart D. The effect of hypnosis therapy on the symptoms and disease activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Psychology & health. 2000;14:1089–104. doi: 10.1080/08870440008407369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rucklidge JJ, Saunders D. The efficacy of hypnosis in the treatment of pruritus in people with HIV/AIDS: a time- series analysis. The International journal of clinical and experimental hypnosis. 2002;50:149–69. doi: 10.1080/00207140208410096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langenfeld MC, Cipani E, Borckardt JJ. Hypnosis for the control of HIV/AIDS-related pain. The International journal of clinical and experimental hypnosis. 2002;50:170–88. doi: 10.1080/00207140208410097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernardy K, Fuber N, Klose P, Hauser W. Efficacy of hypnosis/guided imagery in fibromyalgia syndrome--a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2011;12:133. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alvarez-Nemegyei J, Negreros-Castillo A, Nuno-Gutierrez BL, Alvarez-Berzunza J, Alcocer-Martinez LM. Ericksonian hypnosis in women with fibromyalgia syndrome. Revista medica del Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social. 2007;45:395–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan G, Fukui T, Jensen MP, Thornby J, Waldman KL. Hypnosis treatment for chronic low back pain. The International journal of clinical and experimental hypnosis. 2010;58:53–68. doi: 10.1080/00207140903310824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jensen MP. Hypnosis for chronic pain management: a new hope. Pain. 2009;146:235–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wood GJ, Bughi S, Morrison J, Tanavoli S, Zadeh HH. Hypnosis, differential expression of cytokines by T-cell subsets, and the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. The American journal of clinical hypnosis. 2003;45:179–96. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2003.10403525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller GE, Cohen S. Psychological interventions and the immune system: a meta-analytic review and critique. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2001;20:47–63. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hypnosis before breast cancer surgery eases pain, cuts costs. Harvard women’s health watch. 2007;15:6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nash MR, Tasso A. The effectiveness of hypnosis in reducing pain and suffering among women with metastatic breast cancer and among women with temporomandibular disorder. The International journal of clinical and experimental hypnosis. 2010;58:497–504. doi: 10.1080/00207144.2010.499353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lynch DF., Jr Empowering the patient: hypnosis in the management of cancer, surgical disease and chronic pain. The American journal of clinical hypnosis. 1999;42:122–30. doi: 10.1080/00029157.1999.10701729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ginandes C, Brooks P, Sando W, Jones C, Aker J. Can medical hypnosis accelerate post-surgical wound healing? Results of a clinical trial The American journal of clinical hypnosis. 2003;45:333–51. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2003.10403546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiecolt-Glaser H, Marucha PT, Atkinson C, Glaser R. Hypnosis as a modulator of cellular immune dysregulation during acute stress. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2001;69:674–82. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.4.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Strain EC, et al. Modulation of cellular immunity in medical students. Journal of behavioral medicine. 1986;9:5–21. doi: 10.1007/BF00844640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palsson OS. Hypnosis treatment for Gut Problems. European Gastroenterology and Hepatology Review. 2010;6:42–6. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan G, Hammond DC, Joseph G. Hypnosis and irritable bowel syndrome: a review of efficacy and mechanism of action. The American journal of clinical hypnosis. 2005;47:161–78. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2005.10401481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whitehead WE. Hypnosis for irritable bowel syndrome: the empirical evidence of therapeutic effects. The International journal of clinical and experimental hypnosis. 2006;54:7–20. doi: 10.1080/00207140500328708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palsson OS, Turner MJ, Johnson DA, Burnett CK, Whitehead WE. Hypnosis treatment for severe irritable bowel syndrome: investigation of mechanism and effects on symptoms. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2002;47:2605–14. doi: 10.1023/a:1020545017390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calvert EL, Houghton LA, Cooper P, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. Long-term improvement in functional dyspepsia using hypnotherapy. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1778–85. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.37071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharma RL. Functional dyspepsia: At least recommend hypnotherapy. BMJ. 2008;337:a1972. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palsson OS, Whitehead WE. Hypnosis for non-cardiac chest pain. Gut. 2006;55:1381–4. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.095489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chiarioni G, Vantini I, De Iorio F, Benini L. Prokinetic effect of gut-oriented hypnosis on gastric emptying. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2006;23:1241–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hypnotherapy for duodenal ulcer. Lancet. 1988;2:159–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shaoul R, Sukhotnik I, Mogilner J. Hypnosis as an adjuvant treatment for children with inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics : JDBP. 2009;30:268. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181a7eeb0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller V, Whorwell PJ. Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a role for hypnotherapy? The International journal of clinical and experimental hypnosis. 2008;56:306–17. doi: 10.1080/00207140802041884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emami MH, Gholamrezaei A, Daneshgar H. Hypnotherapy as an adjuvant for the management of inflammatory bowel disease: a case report. The American journal of clinical hypnosis. 2009;51:255–62. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2009.10401675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keefer L, Keshavarzian A. Feasibility and acceptability of gut-directed hypnosis on inflammatory bowel disease: a brief communication. The International journal of clinical and experimental hypnosis. 2007;55:457–66. doi: 10.1080/00207140701506565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mawdsley JE, Jenkins DG, Macey MG, Langmead L, Rampton DS. The effect of hypnosis on systemic and rectal mucosal measures of inflammation in ulcerative colitis. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2008;103:1460–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keefer L, Kiebles JL, Kwiatek MA, et al. The potential role of a self-management intervention for ulcerative colitis: a brief report from the ulcerative colitis hypnotherapy trial. Biol Res Nurs. 2012;14:71–7. doi: 10.1177/1099800410397629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hammond DC, Scheflin AW, Vermetten E. Informed consent and the standard of care in the practice of clinical hypnosis. The American journal of clinical hypnosis. 2001;43:305–10. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2001.10404287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keefer L, Kiebles JL, Martinovich Z, Cohen E, Van Denburg A, Barrett TA. Behavioral interventions may prolong remission in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Behaviour research and therapy. 2011;49:145–50. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Munder T, Gerger H, Trelle S, Barth J. Testing the allegiance bias hypothesis: a meta-analysis. Psychotherapy research : journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research. 2011;21:670–84. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2011.602752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Higgins P, Schwartz M, Mapili J, Zimmerman EM. Is endoscopy necessary for the measurement of disease activity in ulcerative colitis? American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2005;100:355–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Irvine EJ. Development and subsequent refinement of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: a quality- of-life instrument for adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 1999;28:S23–7. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199904001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morisky D, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Medical care. 1986;24:67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Keefer L, Kiebles JL, Taft TH. The role of self-efficacy in inflammatory bowel disease management: preliminary validation of a disease-specific measure. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2011;17:614–20. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Levenstein S, Prantera C, Varvo V, Scribano ML, Berto E, Luzi C, Andreoli A. Development of the perceived stress questionnaire: A new tool for psychosomatic research. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1993;37:19–32. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Levenstein S, Prantera C, Varvo V, Scriabno ML, Andreoli A, Luzi C, Arca M, Berto E, Milite G, Marcheggiano A. Stress and exacerbation in ulcerative colitis: A prospective study of patients enrolled in remission. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2000;95:1213–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker DM, Gandek B. Version 2 of the SF-12 Health Survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ware JE. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Higgins PD, Schwartz M, Mapili J, Krokos I, Leung J, Zimmermann EM. Patient defined dichotomous end points for remission and clinical improvement in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2005;54:782–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.056358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weizman AV, Ahn E, Thanabalan R, et al. Characterisation of complementary and alternative medicine use and its impact on medication adherence in inflammatory bowel disease. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2012;35:342–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lindfors P, Unge P, Nyhlin H, et al. Long-term effects of hypnotherapy in patients with refractory irritable bowel syndrome. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 2012;47:414–20. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2012.658858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gonsalkorale WM, Miller V, Afzal A, Whorwell PJ. Long term benefits of hypnotherapy for irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2003;52:1623–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.11.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gonsalkorale WM, Toner BB, Whorwell PJ. Cognitive change in patients undergoing hypnotherapy for irritable bowel syndrome. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2004;56:271–8. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00076-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lea R, Houghton LA, Calvert EL, et al. Gut-focused hypnotherapy normalizes disordered rectal sensitivity in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2003;17:635–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Berrigan LP, Kurtz RM, Stabile JP, Strube MJ. Durability of “posthypnotic suggestions” as a function of type of suggestion and trance depth. The International journal of clinical and experimental hypnosis. 1991;39:24–38. doi: 10.1080/00207149108409616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Trussell JE, Kurtz RM, Strube MJ. Durability of posthypnotic suggestions: type of suggestion and difficulty level. The American journal of clinical hypnosis. 1996;39:37–47. doi: 10.1080/00029157.1996.10403363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bonaz BL, Bernstein CN. Brain-gut interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:36– 49. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lowen MB, Mayer EA, Sjoberg M, et al. Effect of hypnotherapy and educational intervention on brain response to visceral stimulus in the irritable bowel syndrome. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2013;37:1184–97. doi: 10.1111/apt.12319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pallis AG, Mouzas IA, Vlachonikolis IG. The inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: a review of its national validation studies. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2004;10:261–9. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200405000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huaman JW, Casellas F, Borruel N, et al. Cutoff values of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire to predict a normal health related quality of life. Journal of Crohn’s & colitis. 2010;4:637–41. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Baars JE, Nuij VJ, Oldenburg B, Kuipers EJ, van der Woude CJ. Majority of patients with inflammatory bowel disease in clinical remission have mucosal inflammation. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2011 doi: 10.1002/ibd.21925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dave M, Loftus EV., Jr Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease-a true paradigm of success? Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2012;8:29–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sexton K, Bernstein MT, Walker JR, Graff LA, Miller N, Rogala L, Sargent M, Targownik LE. Digestive Diseases Week. Orlando, FL: 2013. Perceived Stress Is Related to Symptom Burden, but Not Intestinal Inflammation, in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. [Google Scholar]