Abstract

Introduction

Peyronie's disease (PD) can be emotionally and sexually debilitating for patients and may negatively impact partner relationships.

Aims

This study aims to present an ongoing collaborative care model for patients with PD and to discuss the critical need for integration of patient care among sexual medicine physicians and mental health practitioners or sex therapists.

Methods

PubMed searches using the terms “Peyronie's disease” and “natural history,” “treatment,” “psychosexual,” “depression,” “relationship,” and “partner” were conducted. Expert opinion based on review of the relevant published literature and clinical experience was used to identify meaningful treatment targets for patients with PD within a collaborative care model.

Main Outcome Measure

Characteristics of PD, medical treatment, and important assessment and treatment targets, including physical, emotional, psychosexual, and relationship concerns, from peer-reviewed published literature and clinical experience.

Results

PD can result in significant patient and partner distress and relationship disruption. Sex therapy interventions may be directed at acute emotional, psychosexual, and relationship problems that occur during the initial diagnosis of PD, the period following minimally invasive or surgical treatment for PD, or recurring problems over the lifelong course of the disease. Sex therapy to improve self-acceptance, learn new forms of sexual intimacy, and improve communication with partners provides comprehensive treatment targeting emotional, psychosexual, and relationship distress. Ongoing communication between the mental health practitioner and physician working with the patient with PD about key assessments, treatment targets, and treatment responses is necessary for coordinated treatment planning and patient care.

Conclusions

Men with PD are more likely now than in the past to see both a sexual medicine physician and a mental health practitioner or sex therapist, and the integration of assessments and treatment planning is essential for optimal patient outcomes.

Keywords: Relationship Factors, Peyronie's Disease, Treatment Options, Psychosexual Symptoms, Collaborative Care Model

Introduction

Peyronie's disease (PD) is an acquired benign yet debilitating condition characterized by the development of dense fibrous collagens plaques in the tunica albuginea of the penis 1. The plaques prevent normal expansion of the tunica albuginea during erection, resulting in various possible altered penile shapes, such as curvature deformity, shortening, and narrowing with a hinge effect 1. The etiology and underlying pathophysiology of PD are not completely understood. However, PD is thought to originate from trauma or repeated microtrauma to the erect penis in genetically susceptible men 2. Early studies proposed that PD was a rare condition, with a prevalence of <1%; however, later studies have shown that PD is more common, with up to 7.1% of men affected in the general population 3–12. Prevalence estimates are higher in selected populations, ranging from 8.1% in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) 11 to 20.3% in the presence of comorbid DM and erectile dysfunction (ED) 10.

PD can be emotionally and sexually debilitating for patients and may negatively impact partner relationships 13–16. The altered penile shape that patients with PD may experience can prevent intercourse or result in patient bother, greater awkwardness, performance anxiety, less sexual enjoyment, and reduced overall sexual satisfaction. The current article reviews the natural history of the disease course of PD, psychosexual consequences of PD, and current medical treatment options for patients with PD. In response to psychosexual consequences and treatment of PD, men with PD are more likely now than in the past to see both a sexual medicine physician and a mental health practitioner or sex therapist. The current article also presents and discusses an ongoing collaborative biopsychosocial model in which patients with PD are seen by a mental health practitioner and a physician as part of patient management. The model emphasizes ongoing, effective communication that allows an integration of assessments and treatment planning for optimal patient care.

The Natural History of PD

Understanding the natural history of PD supports effective communication and collaboration between the sex therapy mental health practitioner and the sexual medicine physician. Several studies have demonstrated that for most patients, PD is a sustained or progressive disease 13,17,18. When penile curvature is present early in the disease, it tends to stabilize or worsen, with one study showing a mean change in curvature of 22° during the natural course of disease 18. Decreased stretched, flaccid penile length (0.8 cm mean change in length) has also been shown over 18 months 18. In addition to being a chronic disease for many patients, the disease course is highly variable, and the outcome of PD is uncertain.

PD has two phases, acute and chronic, both of which are distinguished by symptom presentation. In the acute phase, the penile plaque is new and still forming, with associated inflammation. The patient may present with one or more symptoms, including painful erections, a palpable plaque, and curvature of the erect penis. Not all patients with PD experience penile pain or discomfort, but for those patients who do experience pain, it usually resolves by 12–18 months after disease onset 18. During the acute phase, the patient's penile shape may be changing, requiring adjustments from the patient and the patient's partner. The patient may begin to experience anxiety and negative self-perceptions related to sexual performance, and sexual function and the partner relationship may be disrupted.

Younger patients may be particularly vulnerable to emotional, psychosexual, and relationship bother/distress and may benefit from integrated care with a sex therapy mental health practitioner and sexual medicine physician. Approximately 10% of patients who present with PD are younger than age 40, including teenagers 10,17,19–21. Younger patients are more likely to present to a physician during the acute phase of PD, typically within 3 months from the onset of symptoms, with the presenting symptoms of pain during erection, palpable nodules, and changing penile shape 20,22. Additionally, progressive worsening of an altered penile shape may be more likely in patients younger than age 50 17,23. Younger patients are more likely to seek treatment sooner, have more than one palpable penile plaque, and present with cardiovascular risk factors, such as DM 19.

The second phase of PD, the chronic disease phase, begins approximately 12–18 months following disease onset. Pain and inflammation typically resolve, and the penile plaque and changing penile shape become relatively stable. During the chronic phase, the penile curvature may continue to worsen in some patients; it rarely improves during this phase 18. In addition to emotional, psychosexual, and relationship concerns associated with chronic PD, patients in the chronic phase may experience anxiety related to surgical treatment options and possible complications, including PD recurrence.

PD Treatments

The symptoms of PD can be medically managed using minimally invasive therapies or surgical intervention in appropriate patients; however, currently there is no cure for PD. Pharmacological treatments and minimally invasive approaches may be considered for patients early in the disease course 24. Currently available therapies include oral systemic agents, iontophoresis, shockwave therapy, traction therapy, and intralesional injections. Intralesional injection of collagenase clostridium histolyticum (CCH; Xiaflex®, Auxilium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Chesterbrook, PA, USA) is the only U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved treatment for men with PD. Most of the existing pharmacological and other minimally invasive treatment regimens have not demonstrated consistent results in clinical trials 25–27. A few treatments have shown significantly decreased penile curvature in placebo-controlled studies, including intralesional injection with interferon (IFN) α-2b; however, additional anti-inflammatory medications may be required with this agent due to side effects, which may limit its use. CCH has also demonstrated efficacy and tolerability in two identical Phase 3 clinical studies 28–33 and has been approved by the U.S. FDA for use in adult men with PD with a palpable plaque and a curvature deformity of 30 degrees or greater at the start of therapy. Treatment with IFN α-2b or CCH requires physician administered injections directly into the penile plaque. IFN α-2b is administered as a biweekly injection over a period of 6–12 weeks and may result in mild to moderate adverse effects, including myalgias, arthralgias, sinusitis, flu-like symptoms with fever and chills, and minor penile swelling 29–31. CCH is administered as two injections separated by 24–72 hours and repeated after 6 weeks, for up to four treatment cycles 28. Following the second injection of each treatment cycle, modeling—this involves gradual, gentle stretching of the flaccid penis in the opposite direction of the penile curvature—is used to further reduce the restrictive effects of the plaque. Adverse effects are transient and most commonly include injection site tenderness, edema, pain, and bruising, and serious adverse events include rare cases of corporal rupture 28,33.

Surgical procedures typically are not considered until patients are within the chronic phase of PD, show stable disease for ≥12 months, or have intractable ED 26,27. Surgical treatment is invasive, and as a result, it is often limited to patients with severe ED and/or a penile shape or level of rigidity that does not allow sexual activity. Surgical treatments to correct the penile curvature include shortening the longer side (known as tunical plication corporoplasty) without intervention on the side of the penis with the plaque, tunical lengthening that targets the restricting effects of the plaque through plaque incision or excision with potential use of grafting materials, or implanting a penile prosthesis with or without straightening maneuvers 26,27,34. Potential complications associated with surgery include penile shortening, risk of sensation changes, recurrence of penile curvature, and subsequent ED 35,36. Possible penile prosthetic implantation complications include device breakdown or failure, recurrent curvature, penile shortening, malposition, infection, erosion, and urethral injury 35–38.

The medical management of PD with minimally invasive treatment and surgical treatment options may address some of the physical symptoms of PD. However, optimal patient management in the integrated care model requires assessment and treatment of emotional, psychosexual, and relationship concerns associated with PD to achieve the most favorable quality-of-life outcomes for patients. Additionally, mental health practitioners within the integrated care model are particularly well suited to the pretreatment or presurgical assessment of patient beliefs and expectations about treatment outcomes. Several long-term follow-up studies have indicated that moderate-to-high levels of dissatisfaction can occur among patients receiving surgery 36,39–41. Given the potential complications and possible recurrence of disease following surgery, the assessment of patient expectations and beliefs about the surgical procedure and the identification and correction of inaccurate beliefs are essential components to presurgical patient management 41–44.

Emotional, Psychosexual, and Relationship Concerns

Assessment of the emotional, psychosexual, and relationship aspects of the patient's PD symptoms that negatively impact the patient's quality of life is needed to prioritize treatment goals. Although severe penile curvature >60° has been identified as an independent predictor of sexual difficulties in patients with PD 45, the full impact of PD on patients is multifaceted and is not necessarily related to the severity of penile curvature. Patients with lesser severities of curvature may have significant bother or distress associated with their disease. A qualitative study of the psychosocial outcomes for patients with PD identified six core domains important to men with PD, including concerns about physical appearance, sexual self-image, loss of sexual confidence and feelings of attractiveness, sexual function and performance, performance anxiety and concern about not satisfying partners sexually, and social stigmatization and isolation 16. Importantly, it was found that the level of concern within these domains was uniformly high, despite a wide range in the degree of penile curvature among the patients studied. Assessment of the psychosexual impact of PD using the PD-specific Peyronie's Disease Questionnaire, a validated, patient-reported measure, has confirmed that high PD symptom bother can occur across the full range of mild, moderate, and severe penile curvature 46. Quality-of-life factors beyond penile curvature, including psychosexual and relationship factors, can impact a patient's perception of his PD 13.

Emotional Concerns

The emotional state of the patient may have important interactions with his psychosexual and relationship concerns, and areas of bother or emotional distress may be an important treatment target for the patient with PD (Table 1). A review of discussion group themes from PD Internet discussion boards aimed at supporting patients with PD and their partners identified patients' feelings of anger, depression, fear of rejection, and diminished self-worth, which led to feelings of isolation and an avoidance of intimacy as important discussion themes 47. In a survey of men with PD, 77% of patients acknowledged psychological effects due to PD, and 55% of patients reported these effects persisted over time 13. A study evaluating depression and quality of life in patients with PD found that 48% of patients had clinically meaningful depression, with 26% of these patients reporting moderate depressive symptoms and 21% reporting severe depressive symptoms 15. Of the patients who reported being depressed at baseline, 58% remained depressed after the 18-month follow-up period, suggesting that rather than adjust to PD symptoms, patients' depressive symptoms persisted 15. In a younger, teenage cohort with PD, high distress was reported by 94% of patients, 34% sought treatment for anxiety/mood disorders, and 28% had a negative experience with a sexual partner related to PD 21.

Table 1.

Call out box highlighting important components of Peyronie's disease (PD)-associated patient emotional distress that may be appropriate targets for treatment

| PD-associated emotional distress treatment targets |

|---|

| Depression |

| Anger |

| Body image dysmorphia |

| Diminished self-worth |

| Feelings of shame and inadequacy |

| Feelings of isolation |

| Fear of rejection |

| Avoidance of intimacy |

In addition to depressive symptoms, patients with PD may experience loneliness or hopelessness, and a partner's level of support, or positive or negative reactions, can influence the patient's feelings of isolation 16. Feelings of isolation and social stigmatization were found to be greater during the early phase of PD before coping mechanisms or trusted support had developed, but the feelings did not resolve over the course of PD 16. Feelings of shame and inadequacy due to PD have been reported and coincided with low self-esteem in some men 16. Additionally, body image issues can be a source of high distress in patients with PD. Patients may experience aesthetic concerns, even if penile functioning is normal, about how the penis looks and feels. This concern may have the greatest impact particularly on homosexual patients with PD, as there can be a constant comparison with the partner's penis. The one available study examining men who have sex with men (MSM) who sought treatment for PD found that 92.9% of MSM reported they were self-conscious about the appearance of their penis and 92.9% were not satisfied with the size of their penis 48. Changes in penile shape are not necessary for body image concerns, as loss of penile girth or length have been reported to be just as distressing as more severe disfigurements, and some men did not like to look at or touch their penis 16. The possibility of body dysmorphia is further suggested by a study showing 54% of men with PD overestimated their degree of penile curvature, and 44% overestimated their curvature by ≥20° 49. Similarly, in one study of postsurgical penile measurement, over half of the patients complained of penile shortening, despite the fact that the objectively measured mean penile length increased by 2.1 cm 50.

Psychosexual Concerns

Psychosexual concerns of the patient with PD may overlap with his emotional state and affect his relationship with his sexual partner, and thus they are an important area of assessment and treatment (Table 2). A patient's anxiety about sex may include concern about hurting his partner during intercourse or further injuring his penis 16. Pain during sex due to penile curvature, for the patient and/or the patient's partner, may be a significant contributor to sexual dysfunction experienced by men with PD and their partners. The contribution of pain to psychosexual concerns and sexual function varies, depending on the severity of the altered penile shape, the duration of PD, and the position of intercourse 16. Moreover, sexual difficulties may exist independent of the patient's physical ability to engage in intercourse due to an altered penile shape. In a study of men with PD, most men were able to engage in penetrative sex; however, many said that intercourse could not be natural or spontaneous 16. The men described their sexual function as impaired due to difficulties with specific sex positions, reduced ability to ejaculate, loss of erection, decreased satisfaction, or pain during intercourse 16. Some men refrained from sex, despite being able to physically engage in vaginal intercourse, due to psychological or interpersonal effects of PD, and many men had withdrawn from all forms of sexual interaction 16. Men with partners were less likely to initiate sex, and single men avoided dating 16.

Table 2.

Call out box highlighting important components of Peyronie's disease (PD)-associated patient psychosexual concerns that may be appropriate targets for treatment

| PD-associated psychosexual treatment targets |

|---|

| Loss of sexual confidence |

| Lack of sexual desire or sexual aversion |

| Decreased sexual satisfaction |

| Difficulty with specific sex positions |

| Sexual performance anxiety |

| Concern about further penis injury |

| Aesthetic concerns: how the penis looks and feels |

| Avoidance of dating |

Relationship Concerns

If the patient's and sexual partner's reaction to PD symptoms is negative, relationship concerns may become a target of treatment (Table 3). In a small study of MSM who sought treatment for PD, 45% of MSM and 64% of non-MSM reported their intimate relationships were negatively affected by PD 48. Relationship and emotional concerns related to PD have been shown to influence one another. In a study of men with PD, the prevalence rates of emotional and relationship problems attributable to PD were 81% and 54%, respectively 14. Among these men, relationship problems were independently associated with emotional problems and the ability to have intercourse, and relationship problems and loss of penile length significantly and independently predicted emotional problems. Relationship concerns associated with PD occur in single men as well as partnered men and may require different treatment focus. In single patients, PD symptoms may result in fear of starting a relationship and avoidance of dating. Discussion group themes from PD discussion board websites showed that single and divorced men avoided intimacy, as they were afraid that their PD would become fodder for gossip among the social networks of women whom they dated 47. The fear of such potential gossip resulted in feelings of shame and loss of control over their personal life.

Table 3.

Call out box highlighting important components of Peyronie's disease (PD)-associated patient and partner relationship concerns that may be appropriate targets for treatment

| PD-associated relationship treatment targets |

|---|

| Concern about not sexually satisfying partner |

| Concern about hurting partner during sex |

| Conflicting or unbalanced sexual desires |

| Lack of emotional support or withdrawal of the partner |

| Loss of intimacy |

| Boredom with limited sexual positions due to penile curvature |

| Partner feelings of helplessness |

| Partner feelings of personal responsibility |

| Partner frustration with patient's fixation on altered penile shape |

| Partner sexual dysfunction |

For couples, potential patient and partner concerns include performance anxiety and concern about satisfying their partner 16. Additionally, conflicting or unbalanced sexual desires between partners, lack of emotional support or understanding, withdrawal of the partner, and loss of intimacy may be important treatment targets. The couple may experience boredom with a limited number of sexual positions that they can engage in due to penile curvature. The partner may experience feelings of helplessness and personal responsibility, especially if the PD developed after an injury during sexual intercourse, and frustration at the PD patient's obsession or focus on the altered shape of his penis. Partners themselves may begin to experience sexual dysfunction requiring intervention 15,51.

Given the breadth of emotional, psychosexual, and relationship concerns that patients with PD may experience, and the high level of distress or bother that may be associated with such concerns, sex therapy aimed at improving sexual communication and satisfaction within the context of PD symptoms and functional constraints is essential for patients and their partners. Consistent with the integrative model of sex therapy and sexual medicine, patients who receive timely information and reassurance about PD and its treatment options, particularly interventions that address sexual functioning and penile shortening, may be more likely to experience less distress and an improved quality of life 14. In a study not specific to men with PD, greater sexual satisfaction and functioning in men was associated with greater self- and partner disclosure about sexual preferences, a skill that can be developed in sex therapy and applied to improving the relationship functioning of men with PD with their partners 52.

Treatment Goals

It is often assumed that successful medical treatment that leads to resolution of PD penile curvature would alleviate psychosexual and relationship concerns. However, one study suggests resolution of physical symptoms may not automatically lead to such a cascade of improvements. In this study, successful and satisfying surgical outcomes for patients with congenital penile curvature did not improve personal relationships or psychogenic ED 53. These findings support the need for an integrated, collaborative care model, which incorporates sex therapy, targeted to emotional, psychosexual, and relationship factors, in collaboration with sexual medicine interventions for optimal patient outcomes. Ongoing assessment of patient function and response to treatment is important, as treatment targets in any one area of concern may influence patient function in other areas of concern. Therefore, patient function and concerns may shift during sexual medicine interventions involving minimally invasive or surgical treatments. Promotion of effective communication about sex and learning techniques to improve sexual function to overcome limitations imposed by PD symptoms may positively and broadly affect emotional concerns of the patient in addition to psychosexual and relationship concerns.

Treatment goals in sex therapy are addressed through individual, couples, and group therapy (see Table 4). Individual therapy is appropriate for patients without a current sexual partner or for patients with a sexual partner who may have personal treatment goals in addition to goals involving their partner. Individual therapy addresses self-image/body image problems, depression, self-acceptance, reframing the symptoms of PD and their associated effects on sexuality and quality of life, and development of effective coping skills to manage anxiety and frustration. Couples therapy additionally addresses psychosexual concerns, relationship distress, and expansion of the definitions of intimacy and sex. Couples learn to explore nonintercourse sexual activities/creativity, and through improved communication and trust, couples determine what sexual satisfaction means for the patient and partner. Additionally, they may learn alternative methods for achieving sexual satisfaction, given limitations imposed by PD symptoms. Group therapy, either in-person or online, can also significantly reduce distress. Social support can be gained through group therapy among patients with PD coping with similar issues, reducing feelings of isolation and assisting in the development of effective coping skills. Furthermore, these same issues can be addressed in group therapy among the partners of patients with PD. Patients should be made aware of Internet-based resources, such as the sexual health discussion forums dedicated to PD and coping with a partner's sexual health issues, which are available at http://www.sexualmed.org.

Table 4.

Call out box highlighting therapeutic approaches to address Peyronie's disease (PD)-associated treatment targets

| Treatment approach | Targeted solutions |

|---|---|

| Individual therapy | Self-acceptance targeting self-image/body image |

| Reframing the symptoms of PD to help the patient reinterpret effects of PD symptoms on sexuality and quality of life | |

| Development of effective coping skills to manage negative emotions | |

| Couples therapy | Expansion of the couple's definitions of intimacy and sex |

| Exploration of nonintercourse sexual activities/creativity | |

| Improved communication about sex to further develop trust | |

| Determination of what sexual satisfaction means for the patient and partner | |

| Development of alternative methods for achieving sexual satisfaction | |

| Group therapy | Providing social support among patients with PD coping with similar issues to reduce feelings of isolation and negative emotions |

| Providing social support among partners of patients with PD coping with similar issues to reduce feelings of isolation and negative emotions | |

| Learning effective coping skills from other patients with PD or their partners |

Integration of Sex Therapy and Sexual Medicine: A Collaborative Care Model

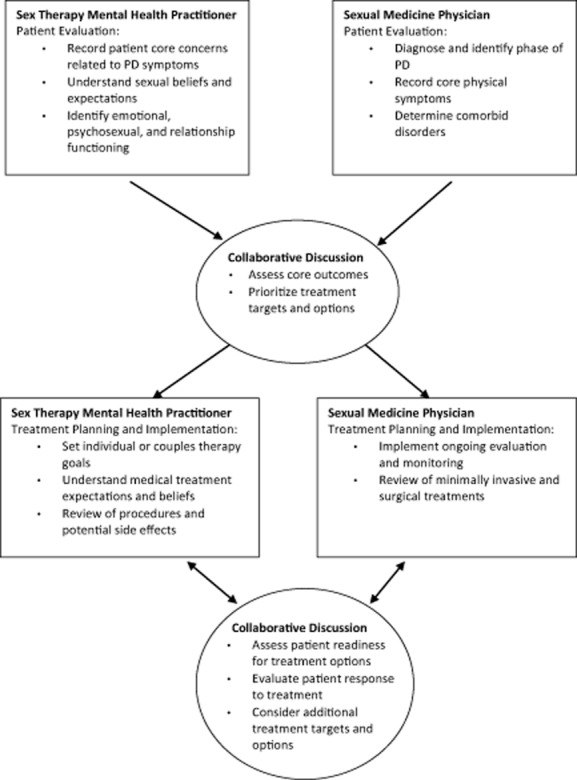

The integration of sex therapy and sexual medicine in the evaluation and treatment of patients with PD addresses the physical aspects of patient sexual function as well as the patient's sexual beliefs and expectations. In addition, emotional, psychosexual, and relationship concerns may all contribute to sexual difficulties and poor quality of life. Optimal patient management necessitates a collaborative working relationship between the patient's mental health practitioner and physician. An ongoing dynamic collaborative model involving a mental health practitioner and a physician working with patients with PD is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A biopsychosocial collaborative model of the integration of sex therapy and sexual medicine in the treatment of patients with Peyronie's disease (PD).

In this model, from the time of initial referral to the clinic, the patient with PD sees both the sexual medicine physician and the sex therapy mental health practitioner. Regular communication between the mental health practitioner and the physician about the patient regarding each provider's assessment of the patient's current function and difficulties and the development of coordinated treatment planning is essential to the collaborative model. The frequency of follow-up visits with the patient's sexual medicine physician and sex therapy mental health practitioner is determined by the assessment, treatment goals, and treatment response of the patient. For patients referred with a diagnosis of PD, the mental health practitioner's assessment of the diagnosis (e.g., when the diagnosis was received, how the assessment of PD was done, and who provided the diagnosis), treatment history, the patient's perspective on response to previous treatments, and the patient's plans for future treatments provide valuable input to the physician's assessment of the patient's medical needs. The physician's treatment regimen and prognoses for the patient can also provide information regarding how the mental health practitioner can be most helpful to the patient's understanding, treatment adherence, and acceptance of his physical condition.

Sex therapy interventions may be directed at acute emotional, psychosexual, and relationship problems that occur during the initial diagnosis of PD, the period following minimally invasive or surgical treatment for PD, or recurring problems over the lifelong course of the disease. Studies of patients with PD who received surgical interventions to correct penile curvature, or other changes in penile shape and rigidity, support the need for a presurgical evaluation of the patient's readiness for surgery 41–44. Any inappropriate or inaccurate expectations expressed by the patient during the presurgical evaluation are then targeted for intervention and are communicated to the physician performing the surgery. The mental health practitioner in the integrated collaborative care model is well positioned to assess patient readiness and to implement any needed interventions to improve patient readiness.

As previously noted, counseling for patients pursuing surgical intervention should address patient expectations for penile straightening, potential adverse events, and surgical recovery, including if the patient has someone who can help take care of him in the immediate postsurgery period. Patient expectations for postsurgery rehabilitation, including possible massage and stretch therapy, use of penile traction therapy, and refraining from sexual intercourse for 6 weeks, should also be addressed 54. For patients receiving penile prosthetic implantation, specific counseling topics should include discussion of the patient's feelings about the penile changes associated with treatment and his understanding that eventually the prosthesis will need to be replaced. Additionally, patients will need to be counseled regarding permanent changes to the structure of the penis required with implantation, and they need to understand that they will never again function naturally without the help of an implant. For patients not currently in a relationship, any patient concerns or anxiety about whether and how the patient would disclose that he has an implant to a new partner should be discussed.

For patients receiving intralesional injection therapy (CCH or interferon), counseling should examine the patient's understanding of the repeated treatment cycles that occur over several months and the time period for penile curvature response, potential adverse effects, and the potential need to refrain from sexual intercourse following treatment. Of additional concern from the therapist's perspective for patients receiving either surgery or intralesional injections, is how the patient's expectations following treatment may affect his relationship with his partner or potential partners. For example, some patients may believe that improvements following treatment may allow them to initiate a new relationship without hesitation or it may “save” their existing relationship. Counseling should be conducted with the patient's partner, when possible to evaluate the partner's expectations for how the treatment will affect their sexual relationship.

Ongoing communication between the sexual medicine physician and the sex therapy mental health practitioner provides the basis of the education interventions that the mental health practitioner presents to the patient about realistic outcomes, potential side effects, and potential adverse events. In settings in which mental health practitioners and physicians are not within the same clinic, a mental health practitioner may be the initial contact for the patient experiencing symptoms of PD. In this situation, the mental health practitioner has the additional role of guiding the patient with a referral to a urologist for evaluation and consideration of medical treatment of PD. It also may be important for mental health practitioners to educate urologists in their area who may not be aware of the benefit of sex therapy in mental health services for the treatment of PD. This can motivate physicians to encourage their PD patients to get the mental health treatment that they may need.

Conclusions

Sex therapy mental health practitioners and sexual medicine physicians have key collaborative roles in the integrated model of the clinical management of patients with PD to maximize quality of life for patients and their partners. Central to this integrated and collaborative model is ongoing communication between the mental health practitioner and physician working with the patient with PD about key assessments, treatment targets, and treatment responses, allowing for coordinated treatment planning and patient care. The mental health practitioner in the integrated collaborative care model is well positioned to assess patient readiness for medical treatment of PD involving surgery and to implement any needed interventions to improve patient readiness. As a chronic, progressive disease with uncertain outcome, PD can result in significant patient and partner distress and relationship disruption. Loss of connection and intimacy, lowered satisfaction in the sexual relationship, and withdrawal of the partner from the relationship are all meaningful targets for sex therapy intervention. Sex therapy to improve self-acceptance, learn new forms of sexual intimacy, and improve communication with partners provides comprehensive treatment targeting emotional, psychosexual, and relationship distress.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Lynanne McGuire, PhD, of MedVal Scientific Information Services, LLC, for providing medical writing and editorial assistance. This manuscript was prepared according to the International Society for Medical Publication Professionals' “Good Publication Practice for Communicating Company-Sponsored Medical Research: the GPP2 Guidelines.”

Source of Funding

Funding to support the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Auxilium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Chesterbrook, PA, USA to MedVal.

References

- Taylor FL, Levine LA. Peyronie's disease. Urol Clin North Am. 2007;34:517–534. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Cadavid NF, Rajfer J. Mechanisms of disease: New insights into the cellular and molecular pathology of Peyronie's disease. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2005;2:291–297. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay MB, Schain DM, Grambsch P, Benson RC, Beard CM, Kurland LT. The incidence of Peyronie's disease in Rochester, Minnesota, 1950 through 1984. J Urol. 1991;146:1007–1009. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37988-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer U, Sommer F, Klotz T, Braun M, Reifenrath B, Engelmann U. The prevalence of Peyronie's disease: Results of a large survey. BJU Int. 2001;88:727–730. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-4096.2001.02436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Pera G, Pescatori ES, Calabrese M, Boffini A, Colombo F, Andriani E, Natali A, Vaggi L, Catuogno C, Giustini M, Taggi F SIMONA Study Group. Peyronie's disease: Prevalence and association with cigarette smoking. A multicenter population-based study in men aged 50–69 years. Eur Urol. 2001;40:525–530. doi: 10.1159/000049830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiBenedetti DB, Nguyen D, Zografos L, Ziemiecki R, Zhou X. A population-based study on Peyronie's disease: Prevalence and treatment patterns in the United States. Adv Urol. 2011;2011:282503. doi: 10.1155/2011/282503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoden EL, Teloken C, Ting HY, Lucas ML, Teodosio da Ros C, Ary Vargas Souto C. Prevalence of Peyronie's disease in men over 50-y-old from Southern Brazil. Int J Impot Res. 2001;13:291–293. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sakka AI. Prevalence of Peyronie's disease among patients with erectile dysfunction. Eur Urol. 2006;49:564–569. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulhall JP, Creech SD, Boorjian SA, Ghaly S, Kim ED, Moty A, Davis R, Hellstrom W. Subjective and objective analysis of the prevalence of Peyronie's disease in a population of men presenting for prostate cancer screening. J Urol. 2004;171(6):2350–2353. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000127744.18878.f1. Pt 1): [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arafa M, Eid H, El-Badry A, Ezz-Eldine K, Shamloul R. The prevalence of Peyronie's disease in diabetic patients with erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2007;19:213–217. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sakka AI, Tayeb KA. Peyronie's disease in diabetic patients being screened for erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 2005;174:1026–1030. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000170231.51306.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tal R, Heck M, Teloken P, Siegrist T, Nelson CJ, Mulhall JP. Peyronie's disease following radical prostatectomy: Incidence and predictors. J Sex Med. 2010;7:1254–1261. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelbard MK, Dorey F, James K. The natural history of Peyronie's disease. J Urol. 1990;144:1376–1379. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39746-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JF, Walsh TJ, Conti SL, Turek P, Lue T. Risk factors for emotional and relationship problems in Peyronie's disease. J Sex Med. 2008;5:2179–2184. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00949.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CJ, Diblasio C, Kendirci M, Hellstrom W, Guhring P, Mulhall JP. The chronology of depression and distress in men with Peyronie's disease. J Sex Med. 2008;5:1985–1990. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen R, Catania J, Lue T, Althof S, Henne J, Hellstrom W, Levine L. Impact of Peyronie's disease on sexual and psychosocial functioning: Qualitative findings in patients and controls. J Sex Med. 2008;5:1977–1984. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadioglu A, Tefekli A, Erol B, Oktar T, Tunc M, Tellaloglu S. A retrospective review of 307 men with Peyronie's disease. J Urol. 2002;168:1075–1079. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64578-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulhall JP, Schiff J, Guhring P. An analysis of the natural history of Peyronie's disease. J Urol. 2006;175:2115–2118. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00270-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveci S, Hopps CV, O'Brien K, Parker M, Guhring P, Mulhall JP. Defining the clinical characteristics of Peyronie's disease in young men. J Sex Med. 2007;4:485–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefekli A, Kandirali E, Erol H, Alp T, Koksal T, Kadioglu A. Peyronie's disease in men under age 40: Characteristics and outcome. Int J Impot Res. 2001;13:18–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tal R, Hall MS, Alex B, Choi J, Mulhall JP. Peyronie's disease in teenagers. J Sex Med. 2012;9:302–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine LA, Estrada CR, Storm DW, Matkov TG. Peyronie disease in younger men: Characteristics and treatment results. J Androl. 2003;24:27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasso M, Lania C, Blanco S, Limonta G. The natural history of Peyronie's disease. Arch Esp Urol. 2007;60:326–331. doi: 10.4321/s0004-06142007000300021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrom WJ. Medical management of Peyronie's disease. J Androl. 2009;30:397–405. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.108.006221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serefoglu EC, Hellstrom WJ. Treatment of Peyronie's disease: 2012 update. Curr Urol Rep. 2011;12:444–452. doi: 10.1007/s11934-011-0212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur S, Limin M, Hellstrom WJ. Current status and new developments in Peyronie's disease: Medical, minimally invasive and surgical treatment options. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12:931–944. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2011.544252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph D, Gonzalez-Cadavid N, Mirone V, Perovic S, Sohn M, Usta M, Levine L. The management of Peyronie's disease: Evidence-based 2010 guidelines. J Sex Med. 2010;7:2359–2374. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelbard M, Goldstein I, Hellstrom WJG, McMahon CG, Smith T, Tursi J, Jones N, Carson CC., 3rd Clinical efficacy, safety, and tolerability of collagenase clostridium histolyticum in the treatment of Peyronie's disease from 2 large double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 studies. J Urol. 2013;190:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.01.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrom WJ, Kendirci M, Matern R, Cockerham Y, Myers L, Sikka SC, Venable D, Honig S, McCullough A, Hakim LS, Nehra A, Templeton LE, Pryor JL. Single-blind, multicenter, placebo controlled, parallel study to assess the safety and efficacy of intralesional interferon α-2B for minimally invasive treatment for Peyronie's disease. J Urol. 2006;176:394–398. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00517-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang G, Matern R, Bivalacqua TJ, Sikka S, Hellstrom WJ. Intralesional interferon-α-2B injections for the treatment of Peyronie's disease. South Med J. 2004;97:42–46. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000056658.60032.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judge IS, Wisniewski ZS. Intralesional interferon in the treatment of Peyronie's disease: A pilot study. Br J Urol. 1997;79:40–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1997.02849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelbard MK, James K, Riach P, Dorey F. Collagenase versus placebo in the treatment of Peyronie's disease: A double-blind study. J Urol. 1993;149:56–58. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35998-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelbard M, Lipshultz LI, Tursi J, Smith T, Kaufman G, Levine LA. Phase 2b study of clinical efficacy and safety of collagenase clostridium histolyticum in patients with Peyronie's disease. J Urol. 2012;187:2268–2274. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal RL, Burnett AL. Surgical management for Peyronie's disease. World J Mens Health. 2013;31:1–11. doi: 10.5534/wjmh.2013.31.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadioglu A, Akman T, Sanli O, Gurkan L, Cakan M, Celtik M. Surgical treatment of Peyronie's disease: A critical analysis. Eur Urol. 2006;50:235–248. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung E, Clendinning E, Lessard L, Brock G. Five-year follow-up of Peyronie's graft surgery: Outcomes and patient satisfaction. J Sex Med. 2010;8:594–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langston JP, Carson CC., III Peyronie disease: Plication or grafting. Urol Clin North Am. 2011;38:207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garaffa G, Minervini A, Christopher NA, Minhas S, Ralph DJ. The management of residual curvature after penile prosthesis implantation in men with Peyronie's disease. BJU Int. 2011;108:1152–1156. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.10023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazili T, Kouriefs C, Anjum F, Masood S, Mufti GR. Ten years outcome analysis of corporeal plication for Peyronie's Disease. Int Urol Nephrol. 2007;39:111–114. doi: 10.1007/s11255-006-9015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paez A, Mejias J, Vallejo J, Romero I, De CM, Gimeno F. Long-term patient satisfaction after surgical correction of penile curvature via tunical plication. Int Braz J Urol. 2007;33:502–507. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382007000400007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akin-Olugbade O, Parker M, Guhring P, Mulhall J. Determinants of patient satisfaction following penile prosthesis surgery. J Sex Med. 2006;3:743–748. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauck EW. Editorial comment: Surgical therapy of Peyronie's disease. Eur Urol. 2006;50:248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Lesser TF, Aboseif SR. Subjective patient-reported experiences after surgery for Peyronie's disease: Corporeal plication versus plaque incision with vein graft. Urology. 2008;71:698–702. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.11.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usta MF, Bivalacqua TJ, Sanabria J, Koksal IT, Moparty K, Hellstrom WJ. Patient and partner satisfaction and long-term results after surgical treatment for Peyronie's disease. Urology. 2003;62:105–109. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh TJ, Hotaling JM, Lue TF, Smith JF. How curved is too curved? The severity of penile deformity may predict sexual disability among men with Peyronie's disease. Int J Impot Res. 2013;25:109–112. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2012.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrom WJG, Feldman R, Rosen RC, Smith T, Kaufman G, Tursi J. Bother and distress associated with Peyronie's disease: Validation of the Peyronie's Disease Questionnaire (PDQ) J Urol. 2013;190:627–634. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.01.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bella AJ, Perelman MA, Brant WO, Lue TF. Peyronie's disease (CME) J Sex Med. 2007;4:1527–1538. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell MR, Corder CJ, Levine LA. Peyronie's disease among men who have sex with men: Characteristics, treatment, and psychosocial factors. J Sex Med. 2013;10:2077–2083. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacal V, Rumohr J, Sturm R, Lipshultz LI, Schumacher M, Grober ED. Correlation of degree of penile curvature between patient estimates and objective measures among men with Peyronie's disease. J Sex Med. 2009;6:862–865. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurkanin JP, Dean R, Wessells H. Effect of incision and saphenous vein grafting for Peyronie's disease on penile length and sexual satisfaction. J Urol. 2001;166:1769–1772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Morales A, Graziottin A, Jaoude GB, Debruyne F, Buvat J, Beneke M, Neuser D. Improvement in sexual quality of life of the female partner following vardenafil treatment of men with erectile dysfunction: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Sex Med. 2011;8:2831–2840. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehman US, Rellini AH, Fallis E. The importance of sexual self-disclosure to sexual satisfaction and functioning in committed relationships. J Sex Med. 2011;8:3108–3115. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallini G, Caracciolo S. Pilot study to determine improvements in subjective penile morphology and personal relationships following a Nesbit plication procedure for men with congenital penile curvature. Asian J Androl. 2008;10:512–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2008.00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor FL, Abern MR, Levine LA. Predicting erectile dysfunction following surgical correction of Peyronie's disease without inflatable penile prosthesis placement: Vascular assessment and preoperative risk factors. J Sex Med. 2012;9:296–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]