Abstract

This study integrates insights from social network analysis, activity space perspectives, and theories of urban and spatial processes to present an innovative approach to neighborhood effects on health-risk behavior among youth. We suggest spatial patterns of neighborhood residents’ non-home routine activities may be conceptualized as ecological, or “eco”-networks, which are two-mode networks that indirectly link residents through socio-spatial overlap in routine activities. We further argue structural configurations of eco-networks are consequential for youth’s behavioral health. In this study we focus on a key structural feature of eco-networks—the neighborhood-level extent to which households share two or more activity locations, or eco-network reinforcement—and its association with two dimensions of health-risk behavior, substance use and delinquency/sexual activity. Using geographic data on non-home routine activity locations among respondents from the Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey (L.A.FANS), we constructed neighborhood-specific eco-networks by connecting sampled households to “activity clusters,” which are sets of spatially-proximate activity locations. We then measured eco-network reinforcement and examined its association with adolescent dimensions of health risk behavior employing a sample of 830 youth ages 12-17 nested in 65 census tracts. We also examined whether neighborhood-level social processes (collective efficacy and intergenerational closure) mediate the association between eco-network reinforcement and the outcomes considered. Results indicated eco-network reinforcement exhibits robust negative associations with both substance use and delinquency/sexual activity scales. Eco-network reinforcement effects were not explained by potential mediating variables. In addition to introducing a novel theoretical and empirical approach to neighborhood effects on youth, our findings highlight the importance of eco-network reinforcement for adolescent behavioral health.

Keywords: Neighborhood Effects, Ecological Networks, Health-Risk Behavior, Social Networks

The effect of residential neighborhoods on the health and well-being of youth is a longstanding focus of social science research (Elliott et al., 1996; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). Pioneering work on “neighborhood effects” suggested social and economic characteristics of youths’ residential contexts influence various outcomes related to delinquency and health-risk behavior (e.g., violence; Cloward & Ohlin, 1960; Shaw & McKay, 1942). After a mid-century hiatus in research on neighborhoods, theoretical innovations (Kasarda & Janowitz, 1974; Kornhauser, 1978; Wilson 1987) combined with statistical advances (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) and large-scale data resources with which to investigate neighborhood contexts (Earls, Brooks-Gunn, Raudenbush, & Sampson, 1995; Sastry, Ghosh-Dastidar, Adams, & Pebley, 2006) prompted a surge in research on neighborhood effects on youth outcomes over the last 30 years (Sampson, Morenoff, & Gannon-Rowley, 2002).

The early phase of this “second wave” of research on neighborhood effects was dominated by theoretical approaches that emphasized the role of cohesive informal social networks in setting the structural conditions for the emergence of effective norms regulating youth health-risk behavior (Kasarda & Janowitz, 1974; Kornhauser, 1978). But recent empirical research has found mixed support for the claim that dense, closely tied informal social networks yield benefits for neighborhood residents (Bellair & Browning, 2010; Bellair, 1997; Browning, Dietz, & Feinberg, 2004; Pattillo, 1998). Consequently, questions regarding the extent and nature of neighborhood social network influence on youth well-being remain unsettled.

In this study we present an alternative, ecologically-based approach to conceptualizing and operationalizing beneficial neighborhood networks for youth. Our approach integrates insights from social network analysis (Granovetter, 1973; Robins and Alexander, 2004), activity space perspectives (Browning & Soller 2014; Kwan, 2009; Kwan et al., 2008), and theory on urban social and spatial processes (Jacobs, 1961; Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997; Wilson, 1996). Specifically, we focus on structural characteristics of neighborhood-based ecological (or “eco-”) networks, which capture the extent to which residents intersect in space when they engage in their non-home, routine activities. In social network terminology, eco-networks represent “two-mode” networks that are comprised of two distinct “node sets.” The first node set consists of neighborhood residents, and the other set consists of residents’ activity spaces. Residents and activity spaces are linked through residents’ participation in routine actions within activity spaces. We argue structural characteristics of eco-networks influence neighborhood-level processes—notably, the collective capacity to supervise and socialize local youth (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Coleman, 1988; Sampson, Morenoff, & Earls, 1999; Wilson 1996)— with implications for adolescent health-risk behavior.

In this study, we consider the association between the extent to which households share two or more activity locations (i.e., “reinforcement”) within eco-networks and two dimensions of health-risk behavior—substance use and delinquency/sexual activity. We then consider whether neighborhood-level collective efficacy and intergenerational closure mediate any observed associations between eco-network reinforcement and adolescent health risks. We employ unique geo-coded data on the routine activities of a large sample of households from the Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey (L.A.FANS). These data allow us to investigate the health consequences of eco-networks for urban youth—previously neglected in research on neighborhoods, networks, and health-risk behavior.

Background

Drawing on the systemic model of community organization (Kasarda & Janowitz, 1974), late 20th century proponents of social disorganization theory highlighted cohesive informal neighbor networks—comprised of frequently interacting individuals who maintain strong connections to one another—as the most effective means for establishing and maintaining informal social control over crime and other social ills. Scholars such as Kornhauser (1978) and Sampson (1988) articulated theoretical models linking variation in levels of intra-neighborhood informal social ties with the collective capacity to achieve pro-social behavioral health outcomes for youth. Yet empirical findings on the benefits of social networks for neighborhood crime and youth wellbeing have been mixed (Bellair, 1997; Pattillo, 1998; Browning, Feinberg, & Dietz 2004). Additionally, community network studies suggest most strong social ties maintained by contemporary urban residents extend beyond the local neighborhood (Fischer, 1982; Wellman, 1979). These findings have led to a shift away from the study of cohesive interpersonal networks as primary sources of local social organization relevant for promoting adolescent behavioral health.

Instead, researchers increasingly have focused on neighborhood normative orientations toward local youth—irrespective of the level of neighborhood informal social interaction—as critical determinants of health-related outcomes. Collective efficacy theory (Sampson, Morenoff, & Earls, 1997; Morenoff, Sampson, & Raudenbush, 2001), for instance, calls into question the regulatory role of social network ties, pointing to high expectations for informal social control of youth as the key neighborhood-level factor limiting the prevalence of delinquency and other health-compromising behaviors. Indeed, evidence indicates that collective efficacy has a protective effect on the occurrence of adolescent health risk behaviors such as risky sexual activity (Browning, Leventhal, & Brooks-Gunn, 2005), alcohol and marijuana use (Erickson et al 2012), and violence (Maimon and Browning 2010). The collective efficacy approach downplays the importance of strong informal social ties among neighbors, suggesting they are insufficient to produce effective informal social control (Sampson et al., 1999). Consistent with this claim, Morenoff et al. (2001) and Browning et al. (2004) found no evidence of direct effects of the extent of informal social interaction on rates of violence in Chicago neighborhoods.

Although contemporary approaches to informal neighborhood social control tend to place less importance on residents’ strong ties, theory and research highlights the pro-social benefits of residents’ weak ties. Granovetter (1973) notes weak ties involve lower expectations for reciprocal exchange and are less time-consuming and emotionally intense than strong ties. But weak ties are important for community cohesion because they provide communication linkages (i.e., “bridging ties”) across local cliques. Absent weak ties, community networks may become fragmented regardless of the abundance of strong ties. Extending Granovetters’ theory, Bellair (1997) argues high levels of infrequent interaction among neighbors reflect the presence of weak ties in communities. Bellair’s study of neighbor networks and crime found the combination of frequent and infrequent (i.e., one or more times per year) interactions among neighbors (but not frequent interactions alone) best helped residents combat crime in the local environment.

Findings on the beneficial role of weak social ties suggest the potential importance of more casual forms of interaction for understanding neighborhood social organization. In what follows, we consider an alternative network approach to neighborhood influence on youth behavioral health emphasizing the interconnectedness of people and local places. We argue the intersection of neighborhood residents in space while engaged in routine activities captures the ecological preconditions for the emergence of neighborhood social processes relevant for the control of adolescent health risk behavior. Structural patterns of spatial overlap in community members’ routine activities—features of eco-networks—represent an important mechanism through which residents establish effective monitoring of public space; baseline levels of familiarity, casual information exchange, trust, reinforcement of place-based conventional behavioral norms; and integration of local youth into mainstream institutions and practices.

Ecological network precursors to neighborhood social organization

We integrate insights from Jacobs’ (1961) theory of street ecology with sociological approaches to neighborhood effects to develop a novel theoretical and empirical approach centered on how eco-networks influence youth developmental outcomes. First, Jacobs argues diverse and spatially-distributed neighborhood routine activity opportunities bring residents onto the street as they travel to and from shared local destinations (school, commerce, work, etc.). Shared connections to routine activity locations and associated conventionally-oriented street activity generate the ecological basis for effective monitoring of public areas—or “eyes on the street” (Jacobs 1961; Browning and Jackson 2013). That is, neighborhood residents must jointly use routine activity spaces in order to collectively engage in their informal social control. Eco-networks capture the structure of residents’ co-presence at routine activity locations (Browning and Soller 2014).

Second, Jacobs also suggests residents who intersect in public space frequently will develop familiarity and a “web of public trust.” Eco-network ties typically will not lead to the formation of conventionally-understood social network ties based on friendship or even acquaintanceship. But neighborhood residents are unlikely to develop familiarity and trust without spatial overlap in routine activities and the repeated encounters such overlap implies (Jacobs, 1961). It is this network of public familiarity and trust that is critical for casual information dissemination, generating shared expectations for public behavior, and promoting a willingness to intervene to enforce behavioral norms—that is, Sampson’s notion of collective efficacy. Consequently, we expect any observed protective effects of eco-network structure to be partially mediated by collective efficacy, including the inter-generationally oriented willingness to support and supervise local youth. Thus, features of eco-networks capture the structural precursors of sources of neighborhood-based social organization (collective efficacy and norms of intergenerational support and control) that are consequential for the prevalence of adolescent health-risk behavior.

Third, extensively shared conventional routines embed local youth in a broader environment characterized by predictable, pro-social patterns of activity. Consistent with Wilson’s (1987; 1996) argument regarding the detrimental effects of “social isolation,” youth who intersect with neighborhood residents on their way to work, going to school, or engaging in other activities revolving around family support or collective life (e.g., grocery shopping, going to a place of worship) will be more effectively drawn into the conventional institutions that shape, and benefit from, these seemingly trivial day-to-day activities. The more consistently daily exposures anchor urban households in the collective experience of conventional institutions such as education, employment, and family life, the more likely resident youth are to view risky and illegal activity as disruptive of conventional goals. Accordingly, we expect embeddedness in interconnected eco-networks—which capture conventional routine activities—to increase the social costs of engaging in a range of health-risk behaviors including those less likely to occur in public space (e.g., substance use and sexual activity).

In sum, shared routine activities as captured by interconnected eco-networks provide effective monitoring, casual information exchange, trust, and reinforcement of behavioral expectations associated with the use of public space while also embedding local youth in the day-to-day public activities of conventional institutional life, with potentially important socialization implications. Thus, the eco-network approach further challenges the emphasis on strong interpersonal ties as the glue that binds local communities and generates effective informal social control (Bellair & Browning, 2010; Browning, Feinberg, and Dietz 2004; Sampson et al., 1997). Below, we provide a technical introduction to our approach, emphasizing the concept and measurement of eco-network reinforcement—a key structural feature of neighborhood eco-networks we hypothesize influences adolescent behavioral health.

Neighborhood eco-networks

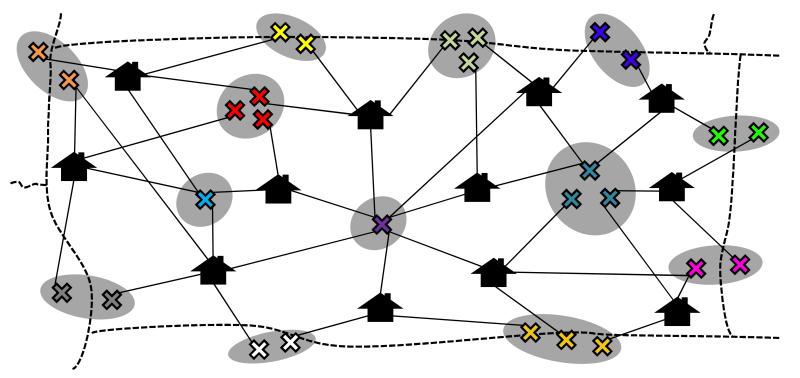

Social network analysts emphasize interdependence among social units and view the world as patterns of relations among actors (Papachristos, 2010). In graph theoretic terminology, networks are comprised of “nodes” (i.e., actors, settings, etc.) and “ties” (i.e., relations between nodes). The eco-networks we focus on are comprised of the following two node sets: (1) neighborhood households, and (2) residents’ activity location clusters. Activity location clusters represent sets of geographically-proximate routine activity locations (Inagami, Cohen, & Finch, 2007; Kwan, 2009). Households are tied to activity location clusters when one or more household members’ activities take place within a cluster. Thus, households within each neighborhood are indirectly tied through shared participation in activity clusters, while clusters are indirectly tied through households. Figure 1 visually depicts a hypothetical neighborhood’s eco-network. In this figure, households are directly tied to activity locations, which are denoted by Xs. The colorings of the Xs and the grey ellipses enclosing them demarcate activity location clusters, which may be located within or outside the neighborhood. Dashed lines represent neighborhood boundaries. Households are indirectly tied if they share activities within the same activity location cluster.

Fig. 1.

Illustrative example of Neighborhood Eco-Network

NOTE: X’s denote activity locations. Grey ellipses and activity location color denote specific activity location clusters. Dashed lines represent neighborhood boundaries.

Reinforcement in eco-networks

Within eco-networks, reinforcement refers to tendencies for neighborhood residents to engage in shared activities within two or more routine activity clusters. High levels of reinforcement capture more frequent opportunities for spatial intersection among residents (Robins and Alexander 2004).

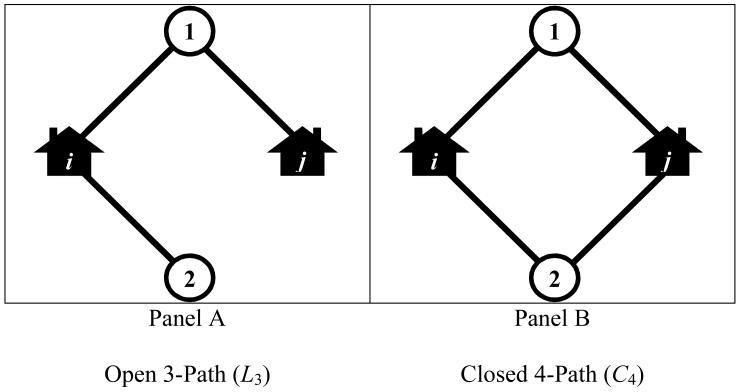

In two-mode eco-networks, reinforcement represents a basic form of network “closure” defined by the linkage of two households through a 4-cycle. For instance, as depicted in Figure 2, Panel A, i and j engage in an activity within Cluster 1, while i (but not j) engages in an activity within Cluster 2. This relation represents an open 3-path because i and j share one activity location but the 3-path is left open by a non-shared location. We operationalize the tendency toward shared routine activity locations within an eco-network as the percentage of 3-paths with the network that are closed (i.e., 4-cycles as depicted in Panel B of Figure 2). The relation between households i and j in Panel B represents a 4-cycle that includes a 3-path (i-1-j) that is closed by i and j both engaging in an activity in Cluster 2.

Fig. 2.

Illustration of Open vs. Closed 4-Path

Reinforcement within two-mode networks reflects aggregate tendencies for network actors to connect to the same set of groups (in our case, locations) as other actors (Opshal, 2013). With respect to neighborhood eco-networks, we hypothesize that higher levels of reinforcement will increase the capacity for shared monitoring of public spaces and promote familiarity and trust. Because reinforcement captures the aggregate extent to which household dyads share more than one activity location, increasing reinforcement is also likely to be associated with interactions beyond passive familiarity, such as actual acquaintanceship. We argue, however, that the weak, routine activity location-anchored network ties associated with higher levels of reinforcement are likely to be productive for the emergence of shared informal social control. Moreover, a key feature of reinforcement in two-mode networks is the linkage of actors through multiple locations (e.g., i and j close the 3-path through a shared location). Thus, the measure is not capturing closure through actors’ ties to the same location (e.g., a highly centralized structural pattern), but rather a structure that allows for dissemination of norms and information more extensively across activity locations.

The present study

We examine the association between reinforcement in neighborhood eco-networks and two dimensions of health-risk behaviors. We first test whether eco-network reinforcement is associated with a multi-item measure of substance use. We then consider links between reinforcement and a second dimension of problem behavior combining multiple indicators of delinquency and the occurrence of sexual activity during adolescence (see dependent measures below). These outcomes have been linked with a variety of physical and mental health implications for youth. Adolescent substance use has been associated with accidental injuries (Boden & Fergusson, 2011) and poor mental health (Hallfors et al., 2004). In addition to the direct health implications of participation in delinquent activities such as violence, arrest and institutionalization for juvenile offenses is linked to numerous markers of poor mental health for adults (Lanctôt, Cernkovich, & Giordano, 2007; Massoglia 2008, while early onset of sexual behavior exposes adolescents to a wide range of adverse outcomes, such as sexually transmitted infections (Weinstock, Berman, & Cates, 2004), unintended/unwanted pregnancies (Santelli & Melnikas, 2010), and poor mental health (Hallfors et al., 2004; Meier, 2007). We consider the effects of eco-network reinforcement after controlling for individual and household characteristics, and a host of neighborhood structural and social process controls. We then examine the extent to which collective efficacy and expectations for intergenerational support and supervision (hereafter “intergenerational closure”) mediate any observed association between eco-network reinforcement and adolescent risk-taking.

Data and Methods

We use data from wave 1 of L.A.FANS and the 2000 decennial census. Wave 1 of L.A.FANS was conducted between 2000 and 2001 and includes a stratified random sample of 65 census tracts in Los Angeles County. Although the sample covers the entire income range, high-poverty tracts were oversampled. Households were randomly selected within each tract, and those with children were oversampled. Within each household a randomly selected adult (RSA) was interviewed. If children under age 17 lived in the household, then the primary caregiver (PCG), if not the RSA, a randomly selected child (RSC), and one of the child’s siblings (SIB) if present, also were interviewed.

Because the L.A.FANS sampling design is based on 1990 tracts, we apply the 2000 data to the 1990 tract boundaries (see Peterson et al. 2007 for information on crosswalk procedures). We use tracts to approximate neighborhood boundaries consistent with the L.A.FANS sampling strategy.

Study sample

We use information provided by L.A.FANS respondents to measure neighborhood social processes (e.g., eco-network reinforcement, collective efficacy), all individual-level covariates, and the dependent variables. Approximately 2,600 RSAs provided information on neighborhood collective efficacy and household-level social capital. Nearly 2,600 RSAs/PCGs provided valid location information of non-home activities used to reconstruct tract-level eco-networks. Analytic samples for the three outcomes investigated in this analysis consist of RSCs and SIBs (i.e., adolescent respondents) between the ages of 12 and 17. Our analytic sample includes 830 adolescent respondents nested in 65 census tracts. Descriptive statistics are displayed in Table 1. Consistent with of the demographics of Los Angeles County, Latinos comprise a large proportion of our sample; 55% of sampled adolescent respondents are Latino, 24% are white, 11% are black, and 10% identify as another race/ethnicity. Additionally, 24% of sampled respondents are first generation immigrants.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Variables | Mean | (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | ||

| Alcohol use (last 30 days) | .14 | |

| Cigarette use (last 30 days) | .07 | |

| Marijuana use (last 30 days) | .06 | |

| Other drug use (last 30 days) | .02 | |

| Ever had sexual intercourse | .15 | |

| Ever arrested | .09 | |

| Ever run away from home | .07 | |

| Member of a gang (last 12 months) | .02 | |

| Carry a gun (last 30 days) | .02 | |

| Individual/Household Variables (N=822) | ||

| Age | 14.47 | (165) |

| Male | .51 | |

| Race/Ethnicity (Ref.=Latino/a) | .55 | |

| White | .24 | |

| Black | .11 | |

| Other | .10 | |

| Immigrant generation (Ref.=first generation) | .24 | |

| Second generation | .35 | |

| Third or later generation | .41 | |

| Primary caregiver education level | 11.76 | (4.68) |

| Residential tenure | .78 | |

| Parental warmth | 3.46 | (66) |

| Family conflict | 1.64 | (.41) |

| Unsupervised socializing | .56 | |

| Household’s number of locations | 4.77 | (160) |

| Neighborhood informal social ties | .03 | (.77) |

| Neighborhood Variables (N=65) | (2.94 | |

| Eco-network reinforcement | 7.79 | ) |

| Neighborhood informal social ties | .00 | (07) |

| Collective efficacy | 3.45 | (.32) |

| Intergenerational closure | 3.53 | (.26) |

| Social disorder | 0 | (123) |

| Total number of locations | 84.92 | 17.33 |

| Concentrated disadvantage | .00 | (126) |

| Immigrant concentration | .00 | (110) |

| Residential instability | .00 | (88) |

| Percentage African American | 8.30 | (9.98) |

Dependent variables

Building on Frank et al. (2007), we consider two scales of health-risk behavior—substance use and delinquency/sexual activity. The substance use scale is composed of four items capturing whether the respondent (1) drank alcohol, (2) smoked cigarettes, (3) used marijuana, or (4) used other drugs (such as crack, cocaine, speed, methamphetamines, heroin, LSD or inhalants) (no = 0, yes = 1). The delinquency/sexual activity scale is based on responses (yes/no) to the following questions: (1) “In the past 30 days, did you ever carry a hand gun?”, (2) “Have you been a member of a gang in the past 12 months?”, (3) “Have you ever run away, that is, left home and stayed away at least overnight without your parent’s”, (4) “Have you ever had sexual intercourse, that is, made love, had sex, or gone all the way with a person of the opposite sex?” (no = 0, yes = 1). The scale composition was based on factor analyses of the total set of items, revealing evidence of substance use and delinquency dimensions; the occurrence of sexual activity loaded highly on the delinquency factor, leading to the decision to incorporate this item into the delinquency scale (see also Frank et al 2007).

Ecological networks

One key innovation of L.A.FANS is the gathering of geographic coordinates for respondents’ non-home routine activities. Such data are not available in any other large-scale probability study of urban residents that contains rich information on individual, household, and neighborhood characteristics. Respondents provided location information (subsequently geocoded to latitude and longitude coordinates) for a number of household members’ routine activities. We use non-home activity locations of the RSA (including those who also are the PCG) and of the RSC (if present) to construct neighborhood eco-networks for each tract in L.A.FANS. RSC activity locations are reported by the PCG. Potential activities include grocery shopping, healthcare, a place other than home or work where the RSA spends the most time, school, employment, religious services, relatives’ homes, childcare, and non-home locations where the child spends the night. We exclude locations with invalid XY coordinates, as well as locations outside California because they are unlikely to be part of the respondents’ daily routines. On average, households reported 5.04 non-home activities with valid XY coordinates. Due to overlapping locations for activities, the average number of unique locations per household—as defined by valid geographic coordinates—is 4.2.

To measure neighborhood eco-networks, we first apply a k-means clustering strategy to the XY coordinates of all non-home locations among every household in LAFANS. This procedure groups activity locations into a pre-determined number (which equals k) of mutually-exclusive point clusters on the basis of distance in space (Kaufmann & Whiteman, 1999). The k-means clustering algorithm selects random coordinates to serve as base points (i.e., centroids) to which other data points are assigned (Kanungo et al., 2002). Points are placed into respective clusters based on distance from these centroids, with points being matched to the closest centroid. This process is repeated whereby new centroids are selected and each point is again matched with its nearest centroid. The process concludes when the mean squared distance from each point to its nearest centroid is minimized. When this criterion is reached, each point within the study area is matched with its appropriate centroid thus placing it in its respective set of activity location settings—which we term “activity location clusters.”

In this study, we chose k=2,500 because this number of clusters minimized the median within-cluster distance between routine activity location XY coordinates (38 meters at the 50th percentile) while also allowing for detection of co-location within the network. Although more precision could be achieved by limiting the distance between activity location points that define a cluster, this approach comes at the expense of network tie detection (in the extreme case of within cluster distance minimization, we would detect no network ties). We also note that the distance between activity locations within clusters varies across clusters (e.g., at the 75th percentile, the median within-cluster distance between routine activity location XY coordinates is 317 meters; at the 95th percentile, it is 602 meters; maximum distances between points at 50th, 75th, and 95th percentiles are 160, 416, and 738 meters, respectively). Our approach captures tendencies to co-locate that, in the aggregate, are hypothesized to capture ecological structures relevant for neighborhood social organization and youth outcomes. Clusters with the largest distances between points tend to be clustered at the outskirts of the metropolitan area—areas with lower population densities where shared spaces may plausibly involve larger physical areas. As an empirical check, we ran analyses based on k = 3,000 and k = 2,000 clusters. Results from these supplementary analyses corroborate our findings regarding the link between network reinforcement and adolescent risk. On average, each cluster contained 2.14 unique activity locations (min=1, max=12).

After identifying activity clusters for all non-home locations in LAFANS, we generate two-mode eco-networks for each of the 65 census tracts in the sample. The first mode consists of households within the tract. On average, there are 39.80 households within each residential tract-network. The second mode consists of the activity clusters containing one or more activity locations for sampled households in the focal tract. On average, there are 84.92 clusters per network (min=46, max=139). All households exhibit at least one tie in 41 of the networks. But in 5 networks, two households have no ties, and in 19 networks just one household has no ties.

Reinforcement in eco-networks

We use the two-mode clustering coefficient C to measure the extent of reinforcement in neighborhood eco-networks (Robins & Alexander, 2004). Robins and Alexander’s coefficient C takes as its denominator the number of 3 paths (labeled L3), that occur in a two-mode network. In our study 3-paths occur when two households are connected through a shared activity cluster (see Panel B in Figure 2). The numerator (4*C4) represents four times the number of 3-paths that are closed by being part of a 4-cycle (C4), or a relation where two households are connected through two distinct activity clusters. C4 is multiplied by 4 because every C4 configuration contains four L3 configurations. Conceptually, this measure captures overall tendencies for 3-paths to become closed 4-cycles and is formally defined as:

This measure varies between 0 to 100, with 100 indicating that all 3-paths in the network are closed (i.e., are 4-cycles). This percentage-based measure (controlling number of activity locations) facilitates comparison of reinforcement across multiple networks (Entwisle et al 2007), but we also consider alternative measures.

Neighborhood mediators

We measure neighborhood collective efficacy by combining information from three subscales asked of RSAs. First, social cohesion/trust includes items gauging respondents’ agreement with 5 statements such as “neighbors generally don’t get along” and “people in this neighborhood can be trusted.” Responses ranged from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”), with items reverse-coded to indicate higher levels of trust/cohesion. Second, informal social control assesses the likelihood neighbors would intervene on behalf of the public good in 3 different situations including children spray-painting graffiti, children loitering, and children showing disrespect to an adult. Responses ranged from 1 (“very unlikely”) to 5 (“very likely”). The measure of collective efficacy represents the empirical Bayes (EB) adjusted intercept from a three-level IRT model with items from the two highly-correlated subscales, nested in individuals, nested in census tracts (multilevel reliability = .90). Sampson et al. (1997) provide more information on the IRT approach to measuring neighborhood collective efficacy. Intergenerational closure includes 5 items capturing bonds between neighborhood adults and children within the neighborhood. Items measure agreement with statements such as “there are adults in the neighborhood that children can look up to” and “parents in this neighborhood know their children’s friends.” Responses ranged from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). The final measure is the EB adjusted intercept from a three-level IRT model comprising intergenerational closure items nested in individuals, nested in neighborhoods (reliability=.85).

Individual-level control measures

We include several individual-level variables that potentially confound the association between eco-network closure and adolescent health-risk behavior outcomes. A binary measure of unsupervised socializing indicates whether the adolescent frequently attends parties with his or her friends (0 = no, 1=yes, as self-reported by the adolescent respondent). Two variables capture family processes that are potentially associated with health-risk behavior. The first measure, parental warmth, taps parent-child affective bonding. Adolescent respondents were asked how often their mother (1) praises them for doing well, and (2) helps them with things that are important to them. These questions then were asked in reference to the father figure (if present). Responses ranged from 1 (“never”) to 4 (“often”). To measure parental warmth, we first took the maximum values (across parents) for each paired item and took the mean of the two items.

Our second family process measure—family conflict—comprises six items capturing the extent of anger and violent confrontation among family members. Adolescent respondents indicated whether people in his or her family (1) fight a lot, (2) hardly ever lose their tempers, (3) get so angry they throw things, (4) always calmly discuss problems, (5) often criticize each other, and (6) sometimes hit each other. Responses ranged from 1 (“true”) to 3 (“not true”). To measure family conflict, we first reverse-coded items 1, 3, 5 and 6 so that higher values indicate greater conflict, and then took the mean of the items (alpha=.627).

We control for several demographic characteristics of the adolescent including age (continuous, in years), race/ethnicity (three indicators for black, white, and other, and Latino/a as the omitted reference category), male sex (0 = no, 1 = yes), and immigrant generation (two indicators for second generation, and third or later generation, and first generation as the omitted reference category). We control for parental education with the education level of the PCG. Education levels ranged from 0 (“less than high school/GED”) to 19 (“graduate/professional degree”). We control for residential tenure, which indicates whether the adolescent has lived in the same residence for 5 or more years, and for the household’s number of locations, which consists of the number of unique geographic coordinates for household members’ routine activities.

Neighborhood control variables

We include three measures of neighborhood structural characteristics (based on the 2000 Census data) commonly used in neighborhood research. First, concentrated disadvantage is measured using the weighted least-squares scores from a factor analysis of the following six items (Johnson & Wichern, 2002): (1) the prevalence of poverty, (2) percentage of residents employed in the secondary labor sector, (3) proportion of female-headed households, (4) unemployment rate, (5) percentage of residents employed in managerial/professional occupations (reverse coded), and (6) college attainment (reverse coded). Residential instability is measured with the standardized percent of residents aged five and older who have moved since 1995. We measure immigrant concentration with the mean of the standardized percentages of the tract population that is (1) foreign born, and that (2) do not speak English well or at all (among those aged five and older). We also include a measure of percentage African American.

We include a measure of neighborhood social disorder to capture conditions that may be associated both with withdrawal from local spatial contexts—reducing the likelihood that households share activity locations—and, potentially, adolescent risk behaviors. The social disorder scale was based on interviewer assessments of the presence of adults loitering, congregating, or hanging out; prostitutes; people selling illegal drugs; people drinking alcohol; drunk/intoxicated people; and homeless people on each block face (i.e., one side of the street for a given block) (Jones, Pebley, & Sastry, 2011). The scale was constructed based on a three-level Rasch model with disorder items at level one, block face at level 2 (controlling time of day the block face was observed—evening, morning, vs. afternoon), and census tract at level three. The final scale score is the tract-level EB residual from the level three model (multilevel reliability = .88). We also include the total number of locations reported at the neighborhood level.

Finally, we include measures that capture strong connections between neighbors at the household and neighborhood levels (with which eco-network reinforcement may be confounded). Informal social ties includes three items indicating the RSA’s social embeddedness within the informal social network of the neighborhood. This individual-level scale includes items tapping frequency of contact with neighbors, the proportion of friends living the neighborhood, and how close the RSA feels to the neighbor with whom he or she is friendliest.

The measure represents the mean of the standardized items (alpha=.625). Higher values suggest more intense relations with neighbors. We also include a measure of neighborhood informal social ties, which represents the mean level of informal social ties among respondents within the tract. Accounting for informal social ties at the individual and neighborhood levels helps ensure that the associations between reinforcement in eco-networks and the outcomes are net of the effects of close and more frequently interacting social ties.

Analytic strategy

We multiply impute missing values for independent variables using the ICE procedure in Stata12 (Royston, 2004). To model the two multi-item scales, we employ three-level Rasch models (items nested within individuals, nested within neighborhoods) with robust standard errors. The multilevel Rasch model views the log odds of participation in any given health-risk behavior as a function of item severity and person propensity (Frank, Cerda, and Rendon 2007; Maimon and Browning 2010; see Raudenbush, Johnson, & Sampson [2003] for a more extended treatment of the multilevel Rasch model as applied to risk behavior).

Results

Substance use

Multilevel Rasch models of substance use are presented in Table 2. Intra-class correlations based on individual and tract-level variance components (1.496 and .074, respectively) from unconditional models indicated that 5% of the variance in substance use is at the neighborhood level. However, the tract level variance does not achieve statistical significance at the conventional level. Model 1 includes individual and neighborhood-level controls and eco-network reinforcement. For the sake of presentation we omit the coefficients and standard errors for individual-level variables (these coefficients and standard errors are presented in the Supplementary Appendix). We include a number of possible structural and social process confounders. Evidence of multi-collinearity emerged for concentrated disadvantage and immigrant concentration. In the LA context, these variables are highly correlated (r > .70). We chose to include both predictors, favoring bias reduction in the coefficient for eco-network reinforcement over stable estimation of the concentrated disadvantage and immigrant concentration effects (although the effects of eco-network reinforcement are consistent with those presented when estimated with only one or the other structural covariate included in otherwise comparable models).

Table 2.

Coefficients from Three Level Rasch Models (with Robust Standard Errors) of Substance Use on Neighborhood Characteristics (Individual Level Coefficients Omitted).a

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood Variables | |||

| Concentrated disadvantage | −.19 (.22) |

−.16 (.24) |

−.21 (.23) |

| Immigrant concentration | −.12 (.26) |

−.11 (.26) |

−.13 (.26) |

| Residential instability | .08 (.13) |

.09 (.14) |

.04 (.14) |

| Percentage African American | −.02 (.02) |

−.02 (.02) |

−.01 (.02) |

| Number of locations | −.01* (.01) |

−.01* (.01) |

−.01* (.01) |

| Informal social ties | −.19 (2.11) |

.41 (2.20) |

.29 (2.20) |

| Social disorder | .31 + (.16) |

.32 * (.16) |

.29 + (.15) |

| Eco-network reinforcement | −.13 ** (.04) |

−.13 ** (.04) |

−.13 ** (.04) |

| Collective efficacy | -- | −.23 (.72) |

-- |

| Intergenerational closure | -- | -- | −.48 (.80) |

| Item Severities (vs. alcohol) | |||

| Cigarette use (last 30 days) | −.98 *** (.20) |

−.98 *** (.20) |

−.98 *** (.20) |

| Marijuana use (last 30 days) | −1.25 *** (.21) |

−1.25 *** (.21) |

−1.25 *** (.21) |

| Other drug use (last 30 days) | −2.79 *** (.29) |

−2.79 *** (.29) |

−2.79 *** (.29) |

| Intercept | −2.42 *** (.13) |

−2.42 *** (.13) |

−2.42 *** (.13) |

| Variance components | |||

| Person level | 1.81 | 1.81 | 1.81 |

| Tract level | .03 | .03 | .02 |

Note: Neighborhood level n=65; person level n=830; item level n=3255.

Robust standard errors are in parentheses. Coefficients for individual-level control variables are included in the Supplementary Appendix.

p<.001,

p<01,

p<.05,

p<. 10 (two-tailed tests).

Coefficients for neighborhood level controls do not achieve significance with the exception of a significant negative effect of the total number of activity locations reported at the neighborhood level (p < .05) and a positive and marginally significant (p < .10) effect of social disorder on substance use. Eco-network reinforcement is negatively and significantly associated with substance use (p<.01), consistent with expectations. The coefficient can be interpreted as the change in the log odds of endorsing any given substance use item associated with a one percentage increase in closed three paths (4 cycles) in the tract-level eco-network. The coefficient (-.13) indicates that a one percentage increase in eco-network reinforcement is associated with a 12% decrease in the odds of substance use. Alternatively, a one standard deviation increase in eco-network reinforcement decreases the odds of substance use by 28%.

Models 2 and 3 include measures of neighborhood collective efficacy and intergenerational closure, testing the hypothesis that these neighborhood social processes independently influence substance use risk and partially mediate the effects of eco-network reinforcement. Neither intergenerational closure nor collective efficacy achieves statistical significance in these models. The coefficient for eco-network reinforcement is unchanged in magnitude and significance across both models, offering no evidence that these social process variables mediate the association between eco-network reinforcement and substance use.

Delinquency/sexual activity

Table 3 presents the results of three-level Rasch models predicting delinquency/sexual activity (hereafter “delinquency”). Intra-class correlations based on individual and tract-level variance components (1.996 and .206, respectively) from unconditional models indicate that 9% of the variance in delinquency is at the neighborhood level. The tract level variance component is statistically significant (p < .05) in the unconditional model, but is no longer significant in models reported in Table 3 (with the inclusion of multiple neighborhood level controls). These models control for all individual-level covariates included in the models from table 2 (see Supplementary Appendix for individual-level coefficients). Model 1 includes neighborhood-level controls and eco-network reinforcement, offering evidence of a positive social disorder effect on delinquency (p < .01), consistent with substance use findings. Eco-network reinforcement is negatively and significantly associated with delinquency (p < .01). A one percentage increase in reinforcement leads to an 8% decrease in the odds of delinquency, and a one standard deviation increase in reinforcement leads to a 21% reduction in the odds of this outcome. Models 2 and 3 include collective efficacy and intergenerational closure, respectively. As with substance use, the coefficients do not achieve significance, offering no evidence of a protective effect of these social processes on delinquency. The coefficient for eco-network reinforcement remains unchanged across models 2-4.

Table 3.

Coefficients from Three Level Rasch Models (with Robust Standard Errors) of Delinquency/Sexual Activity on Individual and Neighborhood Characteristics.a

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood Variables | |||

| Concentrated disadvantage | −.01 (.16) |

−.07 (.16) |

−.05 (.14) |

| Immigrant concentration | −.09 (.19) |

.08 (.19) |

.07 (.18) |

| Residential instability | .11 (.10) |

.07 (.10) |

.05 (.10) |

| Percentage African American | −.02 (.01) |

−.02 (.01) |

−.02 (.01) |

| Number of locations | −.00 (.00) |

−.00 (.00) |

−.00 (.00) |

| Informal social ties | −.45 (.162) |

1.04 (.176) |

1.34 (.171) |

| Social disorder | .36 ** S (.12) ** |

.33 * (.12) ** |

.31 * (.13) ** |

| Eco-network reinforcement | −.08 (.03) |

−.08 (.03) |

−.08 ** (.03) |

| Collective efficacy | -- | −.66 (.62) |

-- |

| Intergenerational closure | -- | -- | −1.03 (.68) |

| Item Severities (vs. sexual activity) | |||

| Ever arrested | −.70 *** I (.15) |

−.70 *** (.15) |

−.70 *** (.15) |

| Ever runaway | −1.00 *** (.16) |

−1.00 *** (.16) |

−1.00 *** (.16) |

| Carry a gun (last 30 days) | −2.31 *** (.26) |

−2.31 *** (.26) |

−2.31 *** (.26) |

| Member of a gang (last year) | −2.43 *** (.27) |

−2.43 *** (.27) |

−2.43 *** (.27) |

| Intercept | −2.19 *** (.12) |

−2.17 *** (.12) |

−2.17 *** (.12) |

| Variance components | |||

| Person level | 1.09 | 1.08 | 1.08 |

| Tract level | .04 | .04 | .04 |

Note: Neighborhood level n=65; person level n=830; item level n=4140.

Robust standard errors are in parentheses. Coefficients for individual-level control variables are included in the Supplementary Appendix).

p<.001,

p<.01,

p<.05,

+p<.10 (two-tailed tests).

Alternative approaches to measurement of eco-network reinforcement across networks

Comparison of network structural measures across networks is complicated by differences in network size and density across tracts. The relative ranking of tracts on the basis of the raw percentage of closed three paths may be problematic if this measure has different meaning across networks of varying size and density. To address this concern, we constructed an alternative measure of reinforcement that captures the extent of reinforcement within the observed network that is beyond what is expected by chance, given the number of individuals, location clusters, and ties in each eco-network. For each tract we first generated 1,000 random networks that maintain the number of households, activity locations, and ties that were present in the tract’s eco-network. We then estimated the mean and standard deviation of reinforcement across the 1,000 random networks for each tract. The resulting mean values represent the level of reinforcement that is expected by chance, given the actual density of the eco-network. We then subtracted the mean level of reinforcement within each tract’s 1,000 random networks from the level of reinforcement within the observed eco-network. This difference then was divided by the standard deviation of the simulated network reinforcement values in order to standardize the value for comparison across multiple networks. We estimated the effect of this alternative measure of reinforcement on substance use and delinquency/sexual activity in models that were comparable to model 1 of tables 2 and 3. Effects of reinforcement remained negative and statistically significant in these models (substance use: p < .05; delinquency/sexual activity: p < .01).

Robustness of eco-network reinforcement effects for respondents residing in disadvantaged neighborhoods

Although we find evidence of average protective effects of reinforcement on health-risk outcomes, we also examined reinforcement effects within higher disadvantage neighborhoods in order to confirm that youth residing in these riskier contexts also experience benefits from increasing overlap in routine activity locations. We fit models comparable to model 1 of tables 2 and 3 only for respondents who were above the sample mean on neighborhood concentrated disadvantage. The effect of reinforcement remained comparable in magnitude and significance for both scales, indicating that reinforcement does not interact with neighborhood concentrated disadvantage in its effect.

In sum, results demonstrate that eco-network reinforcement exhibits robust and consistent effects on measures of both substance use and delinquency/sexual activity. These effects hold net of a host of individual/household and neighborhood controls, including a rich set of neighborhood structural measures and potentially confounding social processes. Eco-network effects on health-risk outcomes are observed above and beyond the influence of individual- and neighborhood-level social ties, which are not influential predictors of adolescent risk. Neither collective efficacy nor intergenerational closure mediated the effects of eco-network reinforcement on adolescent risk.

Conclusion

To date, neighborhood research has not offered strong evidence supporting the hypothesis that neighborhood-level informal social networks provide beneficial social organizational resources for youth. Findings on the protective effects of such networks—as measured by the extent of close ties, such as those based on friendship and kinship within local neighborhoods and on the frequency of social interaction—have been equivocal at best and, in some cases, suggest such ties may lead to worse health outcomes for youth. Recent research emphasizing normative orientations toward informal social control and collective efficacy has offered more consistent evidence of a protective effect for youth outcomes. We argue, however, that the theoretical shift away from networks as sources of neighborhood social organization is premature. We point specifically to the role of spatially-intersecting conventional routine activities—eco-networks— as a source of familiarity, casual information dissemination, public trust, normative reinforcement, and monitoring. By focusing on ties between people and shared routine activity settings, our approach “spatializes” networks (Tita & Radil, 2011) that emerge from residents’ patterns of interaction. Eco-networks in turn may have more direct implications for neighborhood social organization and youth outcomes compared to conceptualizations of close social network ties that neglect geographic space.

Our analyses focused on the role of reinforcement within ecological networks— specifically, the extent to which households residing in each of 65 Los Angeles neighborhoods shared two or more activity locations. Our findings demonstrate the protective effects of reinforcement within eco-networks on two scales capturing substance use and delinquency/sexual activity. Increasing eco-network reinforcement was negatively and significantly associated with both health-risk behavior dimensions. The effects of reinforcement were observed above and beyond a wide range of neighborhood and individual-level controls. Consistent with extant literature, the extent of neighborhood informal social ties was not protective with respect to the adolescent behavioral health outcomes we considered. Contrary to expectations, however, measures of collective efficacy and intergenerational closure did not mediate the effects of eco-network reinforcement. Significant associations between reinforcement and the problem behavior outcomes remained after taking into account potential mediating processes. These findings suggest reinforcement may be working through intervening social processes related to everyday involvement in place-based conventional routines that are not adequately captured by our measures of collective efficacy or intergenerational closure. For instance, routine exposures of youth to neighbors engaged in conventional activities such as employment, education, and family support likely promote pro-social goals and expectations, increasing the costs of a range of health-risk behaviors. Assessing the role of eco-networks in fostering a sense of embeddedness in conventional institutions and positive expectations for the future may yield insight into the youth-level processes that account for beneficial eco-network effects. Future research capturing the social-psychological dimensions of this process may help shed light on the mechanisms through which eco-networks operate to influence adolescent outcomes.

In addition, eco-network reinforcement also may promote health and well-being by enhancing youths’ sense of security and reducing stress. At the individual-level, youth’s exposure to neighbors engaged in co-located routinized activities enhances ontological security by promoting a sense of predictability within and across contexts of interaction (Giddens, 1990; Frohlich et al., 2001; Hawkins & Maurer, 2011). Lacking such security, adolescents may be more likely to experience mistrust and stress associated with their daily activities, thus increasing the likelihood of coping activities such as substance use, delinquency, risky-sexual behavior, and other adverse behaviors. Finally, eco-networks that integrate local institutions and service agencies into residents’ informal activities may lead to information dissemination regarding various resources, such as local health-related services. These potential mechanisms highlight the importance of capturing youth perceptions of local neighborhood social organization (e.g., trust, safety) more directly as well as patterns of youth integration into local institutions and health behavior-related services.

Although LAFANS currently offers the most comprehensive activity space information available in a large-scale neighborhood-based social survey, our analyses are limited in several respects. The relatively small number of geo-coded locations provided by respondents inevitably represented the entire household activity space incompletely, potentially biasing the representation of eco-networks. Moreover, the lack of precise information on time spent at activity space locations meant that we could not generate co-location networks by both space and time-of-day. Moreover, the core concept of a “tie” in our eco-network framework can be highly variable—from fleeting “familiar stranger” contacts to, potentially, more enduring, closer contacts. More detailed information regarding the timing, duration, and extent of co-presence at locations within neighborhood eco-networks may provide more insight into the specific types of repeated encounters and eco-network structural patterns that most benefit health and well-being. In addition, our study relies on a sample from a single city. We therefore caution against generalizing our findings; further research informed by the eco-network approach presented here is needed to assess the extent to which our findings are unique to the Los Angeles area, or apply to other urban areas throughout the US and the rest of the world. Finally, we used only the first wave of LAFANS data, precluding analyses of change over time in the outcomes considered. Thus, the associations we observe between eco-network closure and youth outcomes cannot be interpreted as causal.

Data collection efforts increasingly are incorporating sophisticated measures of spatial exposure, for example, through the use of mobile phone-based GPS information (Browning & Soller, 2014; Palmer, 2013; Wiehe et al., 2008). These and other approaches that generate rich data on human mobility patterns will offer increasingly precise information on shared routine activities. Such data will provide an opportunity to investigate micro-level aspects of spatial exposures such as time spent at institutions, private residences, and unstructured settings. Information on network ties that integrate distinct types of places combined with data on the timing of spatial intersection will yield unprecedented insight into the ecological structure of urban spaces and their role in shaping health and well-being across the life course.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Neighborhood ecological networks link residents through routine activities.

Ecological network reinforcement protects against adolescent problem behavior.

Ecological network protective effects are comparable in disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Thanks to the Special Issue Editors and reviewers for comments on previous versions of the manuscript. The authors acknowledge financial support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA032371), the William T. Grant Foundation, the National Science Foundation, and the Ohio State University Institute for Population Research.

Contributor Information

Christopher R. Browning, The Ohio State University

Brian Soller, University of New Mexico.

Aubrey L. Jackson, University of New Mexico

References

- Bellair PE. Social Interaction and Community Crime: Examining the Importance of Neighbor Networks. Criminology. 1997;35(4):677–704. [Google Scholar]

- Bellair PE, Browning CR. Contemporary Disorganization Research: An Assessment and Further Test of the Systemic Model of Neighborhood Crime. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2010;47(4):496–521. [Google Scholar]

- Boden JM, Fergusson DM. The short and long term consequences of adolescent alcohol Use. In: Saunders J, Rey JM, editors. Young people and alcohol: Impact, policy, prevention and treatment. Wiley-Blackwell; Chichester: 2011. pp. 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard university press; Boston: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Dietz RD, Feinberg SL. The Paradox of Social Organization: Networks, Collective Efficacy, and Violent Crime in Urban Neighborhoods. Social Forces. 2004;83(2):503–534. [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Jackson AL. The Social Ecology of Public Space: Active Streets and Violent Crime in Urban Neighborhoods. Criminology. 2013;51:795–1043. doi: 10.1111/1745-9125.12026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Jackson AL, Soller B, Krivo L, Peterson RD. Ecological Community and Neighborhood Social Organization; Presented at the Annual Meetings of the American Society of Criminology; Washington D.C.. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Sexual Initiation in Early Adolescence: The Nexus of Parental and Community Control. American Sociological Review. 2005;70(5):758–778. [Google Scholar]

- Browning Christopher R., Soller Brian. Moving Beyond Neighborhood: Activity Spaces and Ecological Networks as Contexts for Youth Development. Cityscape. 16:165–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloward RA, Ohlin LE. Delinquency and Opportunity: A Theory of Delinquent Gangs. Free Press; New York: 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JS. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94:S95–S120. [Google Scholar]

- Earls FJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Raudenbush SW, Sampson RJ. Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods 1995-2002 [Computer file]. ICPSR13714-v1. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; Ann Arbor, MI: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, et al. The Effects of Neighborhood Disadvantage on Adolescent Development. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1996;33(4):389–426. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle B, Faust K, Rindfuss RR, Kaneda T. Networks and Contexts: Variation in the Structure of Social Ties. American Journal of Sociology. 2007;112(5):1495–1533. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson PG, Harrison LL, Cook S, Cousineau M, Adlaf EM. A comparative study of the influence of collective efficacy on substance use among adolescent students in Philadelphia, Toronto, and Montreal. Addiction Research and Theory. 2012;20(1):11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer CS. To dwell among friends: Personal networks in town and city. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Frohlich KL, Corin E, Potvin L. A theoretical proposal for the relationship between context and disease. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2001;23(6):776–797. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens A. The Consequences of Modernity. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter M. The Strength of Weak Ties. American Journal of Sociology. 1973;78(6):1360–1380. [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors DD, et al. Adolescent Depression and Suicide risk: Association with Sex and Drug Behavior. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;27(3):224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins RL, Maurer K. ‘You fix my community, you have fixed my life’: the disruption and rebuilding of ontological security in New Orleans. Disasters. 2011;35(1):143–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2010.01197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagami S, Cohen DA, Finch BK. Non-residential neighborhood exposures suppress neighborhood effects on self-rated health. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65(8):1779–1791. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Random House; New York: 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RA, Wichern DW. Applied multivariate statistical analysis. Vol. 5. Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jones M, Pebley AR, Sastry N. Eyes on the block: Measuring urban physical disorder through in-person observation. Social Science Research. 2011;40(2):523–537. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanungo T, Mount DM, Netanyahu NS, Piatko CD, Silverman R, Wu AY. An efficient k-means clustering algorithm: Analysis and implementation. Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, IEEE Transactions on. 2002;24(7):881–892. [Google Scholar]

- Kasarda JD, Janowitz M. Community Attachment in Mass Society. American Sociological Review. 1974;39(3):328–339. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann P, Whiteman CD. Cluster-Analysis Classification of Wintertime Wind Patterns in the Grand Canyon Region. Journal of Applied Meteorology. 1999;38(8):1131–1147. [Google Scholar]

- Kornhauser R. Social Sources of Delinquency. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kwan MP. From place-based to people-based exposure measures. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69(9):1311–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan MP, Peterson RD, Browning CR, Burrington LA, Calder CA, Krivo LJ. Reconceptualizing Sociogeographic Context for the Study of Drug Use, Abuse, and Addiction. In: Thomas YF, Richardson D, Cheung I, editors. Geography and Drug Addiction. Springer; New York: 2008. pp. 437–446. [Google Scholar]

- Lanctôt N, Cernkovich SA, Giordano PC. Delinquent behavior, official delinquency, and gender: consequences for adulthood functioning and well-being. Criminology. 2007;45(1):131–157. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The Neighborhoods They Live in. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126(2):309–337. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maimon D, Browning CR. Unstructured Socializing, Collective Efficacy, and Violent Behavior Among Urban Youth. Criminology. 2010;48(2):443–474. [Google Scholar]

- Massoglia Michael. Incarceration, Health, and Racial Disparities in Health. Law and Society Review. 2008;42:275–306. [Google Scholar]

- Meier A. Adolescent first sex and subsequent mental health. American Journal of Sociology. 2007;112(8):1811–1847. [Google Scholar]

- Morenoff JD, Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW. Neighborhood Inequality, Collective Efficacy, and the Spatial Dynamics of Urban Violence. Criminology. 2001;39(3):517–558. [Google Scholar]

- Opsahl T. Triadic closure in two-mode networks. Social Networks. 2013;35(2):159–167. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer JR. Activity-space segregation: Understanding social divisions in space and time. Princeton University; 2013. p. 3604494. 150 pages. [Google Scholar]

- Papachristos AV. The Coming of a Networked Criminology? Measuring Crime and Criminality: Advances in Criminological Theory. 2010;17:101–140. [Google Scholar]

- Pattillo ME. Sweet Mothers and Gangbangers: Managing Crime in a Black Middle-Class Neighborhood. Social Forces. 1998;76(3):747–774. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CE, Pebley AR, Sastry N. RAND Labor and Population Working Paper Series. 2007. The Los Angeles Neighborhood Services and Characteristics Database: Codebook. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen A, Aber MS, Bhana A. Adolescent coping and neighborhood violence: perceptions, exposure, and urban youths’ efforts to deal with danger. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;33(1-2):61–75. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000014319.32655.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Johnson C, Sampson RJ. A Multivariate, Multilevel Rasch Model with Application to Self-Reported Criminal Behavior. Sociological Methodology. 2003;33:169–211. [Google Scholar]

- Robins G, Alexander M. Small worlds among interlocking Directors: Network structure and distance in bipartite graphs. Computational and Mathematical Organization Theory. 2004;10(1):69–94. [Google Scholar]

- Royston P. Multiple Imputation of Missing Values. Stata Journal. 2004;4(3):227–241. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ. Local Friendship Ties and Community Attachment in Mass Society: A Multilevel Systemic Model. American Sociological Review. 1988;53(5):766–779. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Earls F. Beyond Social Capital: Spatial Dynamics of Collective Efficacy for Children. American Sociological Review. 1999;64(5):633–660. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Gannon-Rowley T. Assessing “Neighborhood Effects”: Social Processes and New Directions in Research. Annual Review of Sociology. 2002;28:443–478. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and Violent Crime: A Multilevel Study of Collective Efficacy. Science. 1997;277(5328):918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli JS, Melnikas AJ. Teen fertility in transition: recent and historic trends in the United States. Annual Review of Public Health. 2010;31:371–383. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastry N, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Adams J, Pebley AR. The design of a multilevel survey of children, families, and communities: The Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey. Social Science Research. 2006;35(4):1000–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw C, McKay HD. Juvenile Delinquency and Urban Areas. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Tita GE, Radil SM. Spatializing the Social Networks of Gangs to Explore Patterns of Violence. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2011;27(4):521–545. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W. Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2004;36(1):6–10. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.6.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellman B. The Community Question: The Intimate Networks of East Yorkers. The American Journal of Sociology. 1979;84(5):1201–1231. [Google Scholar]

- Wiehe SE, et al. Using GPS-enabled cell phones to track the travel patterns of adolescents. International Journal of Health Geographics. 2008;7(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-7-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass, and public policy. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. When work disappears: The world of the new urban poor. Random House; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.