Abstract

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women, and tamoxifen is the preferred drug for estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer treatment. Many of these cancers are intrinsically resistant to tamoxifen or acquire resistance during treatment. Consequently, there is an ongoing need for breast cancer drugs that have different molecular targets. Previous work has shown that 8-mer and cyclic 9-mer peptides inhibit breast cancer in mouse and rat models, interacting with an unsolved receptor, while peptides smaller than eight amino acids did not. We show that the use of replica exchange molecular dynamics predicts the structure and dynamics of active peptides, leading to the discovery of smaller peptides with full biological activity. Simulations identified smaller peptide analogues with the same conserved reverse turn demonstrated in the larger peptides. These analogues were synthesized and shown to inhibit estrogen-dependent cell growth in a mouse uterine growth assay, a test showing reliable correlation with human breast cancer inhibition.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed in women and is the second leading cause of cancer death among women, closely following lung cancer. In 2006, the American Cancer Society estimated that 212 920 women in the United States will be diagnosed with invasive breast cancer and predicted 40 970 deaths.1 Tamoxifen is the most widely used drug for the treatment of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer, acting through competition with estrogen for binding to the estrogen receptor (ER).

However, approximately one-third to one-sixth of ER-positive breast cancers are intrinsically resistant to tamoxifen, and many more acquire resistance to this drug during treatment.2 Additionally, tamoxifen stimulates uterine growth, which can lead to uterine cancer in a small percentage of women taking this drug.2 Consequently, there is an ongoing need for breast cancer drugs with greater efficacy and fewer side effects.

α-Fetoprotein (AFP) is an embryo specific serum α-globulin glycoprotein that is synthesized primarily by the fetal liver and circulates through the serum of pregnant women.3 AFP has been reported to bind and transport ligands, including fatty acids, steroids, heavy metal ions, phytoestrogens, drugs, and some toxins.4 AFP is a growth-regulating hormone with the capacity to stimulate or inhibit growth.5 From fertilization through birth, AFP holds an important physiological role as a developmental promoter for the fetus. More recent reports have shown that AFP has antiestrogenic activity and can inhibit the growth of estrogen dependent cancer.2,6–8 These data, combined with epidemiological data showing that elevated levels of AFP are associated with a reduced lifetime risk of breast cancer,7 have led to the suggestion that AFP or analogues thereof may be a useful agent for chemoprevention, as well as for the treatment, of breast cancer.7,9,10 Festin et al.,11 Eisele et al.,12,13 and Mesfin et al.14 parsed the 70 000 MW AFP into a series of smaller peptides that retained the same antiestrogenic and antibreast cancer activities of the original protein. Their work resulted in the smallest known active analogue, an 8-mer with the sequence EMTPVNPG (AFPep),14 which consists of amino acids 472–479 from the human AFP sequence. Amino acid substitution studies revealed the importance of specific residues essential for activity.15 All efforts since then to create an active peptide consisting of fewer than eight residues has resulted in the loss of antiestrogenic activity.14,15

A receptor for AFP on cancer cell membranes has been reported,16 and binding of AFP (or AFPep) to this receptor signals the cell to inhibit its own growth. The steric/electronic features of the receptor site that permits AFP binding are largely unknown, making rational development of lead compounds difficult. We present here a novel strategy for developing new lead compounds, a strategy that uses molecular dynamics to explore the allowed conformational space of potentially active analogues in solution. Rational drug design using molecular dynamics in this manner involves understanding the conformational space occupied by the active compounds followed by the creation of different compounds that sample the same space. We have used Replica Exchange17,18 Molecular Dynamics (REMD) techniques19 to explore the conformational dynamics of several AFPep analogues. Our REMD results reveal that the peptide’s critical region for activity is a four amino acid sequence that adopts a Type I β-turn conformation. We have run REMD simulations on several different four and five amino acid peptides, synthesized those that appeared promising, along with controls, and tested them for activity using an immature mouse uterine growth assay.2 Results from the REMD simulations and the experimental activity studies are presented in this paper and show that peptides as short as four amino acid residues retain biological activity.

The REMD technique has been successfully used to obtain energy landscapes for the TRP cage and for the C-terminal β-hairpin of protein G,20–22 to find the global minimum for chignolin23 and to explore unfolding of α-helical peptides as a function of pressure and temperature.24 REMD has also been used to explore intrafacial folding and membrane insertion of designed peptides25 as well as simulations of DNA.26,27 Recent work has focused on use of REMD to determine peptide structure and peptide and protein folding pathways.28–85 We demonstrate for the first time that REMD, besides being an excellent technique for probing peptide and protein structure, can be used for a lead compound design.

Methods

We used the AMBER 8 molecular dynamics program package19,86 with a new force field that has been created specifically to improve the representation of peptide structure.87 Simulations were run in implicit solvent, using the Generalized Born (GB) model88 implemented in AMBER89 with the default radii under the multisander framework.89 It has been demonstrated that the use of continuum solvent models in REMD can lead to overstabilization of ion pairs that affect the secondary structure,90,91 but since we do not have salt bridges in our peptide structure we avoid this potential problem. Adequate sampling of conformational space was insured through the use of the Replica Exchange algorithm.17,18 REMD was developed as a means to overcome local potential energy barriers. Compiled under AMBER 8, one-dimensional REMD explores a generalized canonical ensemble of N noninteracting replicas that undergo simulation separately but concomitantly at exponentially related temperatures, with exchanges between replicas occurring at a specified time interval. The consequence of this exchange is that entrapment in local potential energy wells is avoided. Those replicas that do become trapped within a local well at one temperature can escape when transitioned to a higher temperature as part of the exchange process. Thus, accuracy of conformation is maintained through analysis at low temperatures, while simulations at higher temperatures efficiently achieve exploration of the potential energy surface.

The sequences used for the simulations were chosen from the set of previously synthesized active analogues.15 REMD simulations were run on the cyclic analogues cyclic-[EKTPVNPGN], cyclic-[EKTPVNPGQ], cyclic-[EMTPVNPGQ], and the linear analogues EMTPVNPG and EMTPTNPG. In addition, REMD simulations were run on the smaller analogues EMTPVNP, MTPVNPG, TPVNP, TPVN, and PVNP. All sequences were capped using an acetyl beginning residue and an N-methylamine ending residue. Eight different replicas were used, each defined initially with the same input structure. Temperatures were selected to agree with exponential growth such that interchange occurred within the temperature group tempi, tempo = 265, 304, 350, 402, 462, 531, 610, and 700 K. The same temperatures were used for each peptide simulated and controlled using a weak-coupling algorithm as specified by ntt) 1. The number of exchange attempts between neighboring replicas was set to 1000, and the number of MD steps between exchange attempts was defined as 10 000. Thus, the total length for each simulation with a time step of 0.002 ps was 20 ns.19 Additional methodological information can be found in a forthcoming paper.92

The linear peptide analogues shown in Table 2 were prepared using Fmoc solid-phase synthesis.14,15,93 The antiestrogenic activity of each peptide was determined using the immature mouse uterine growth assay as described previously.2,7 Intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration of 0.5 μg of 17β-estradiol (E2) to an immature female mouse doubles its uterine weight in 24 h.7 Swiss/Webster female mice, weighing 6–8 grams at 13–15 days old, were obtained from Taconic Farms. Mice were grouped so that each group had the same range of body weights. Each group received two sequential i.p. injections spaced 1 h apart. The peptide or a saline solution control was contained in the first injectant, and E2 or a saline control was contained in the second injectant. 22 h after the second injection, uteri were dissected and weighed immediately. The uterine weights were normalized to mouse body weights (mg of uterine/g of body). Experiments used a minimum of five mice per group, and the mean normalized uterine weight and standard deviations were determined for each group. Percent growth inhibition in a test group was calculated from the normalized uterine weights as given by eq 1.

Table 2.

Effect of AFP-derived Peptides on Estrogen-stimulated Growth of Immature Mouse Uterusa

| sequence | % inhibition ± SE |

|---|---|

| EMTPVNPG | 34 ± 3b |

| EMTOVNOG | 32 ± 4b |

| EMTPVNP | 19 ± 2 |

| TOVNO | 31 ± 4b |

| TPVNP | 26 ± 1b |

| TPVN | 24 ± 5b |

| TOVN | 22 ± 1b |

| OVNO | 6 ± 5 |

| PVNP | 5 ± 3 |

| PGVGQ | 0 |

| EMTPV | 0 |

| EMTOV | 0 |

Estradiol and peptide injection into immature mice was carried out as described in Methods. Peptide was injected intraperitoneally at a dose of 1 μg per mouse.

p < 0.05 when compared to group stimulated with E2 alone. Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test.

| (1) |

The significance of differences between groups was evaluated with the nonparametric Wilcoxon ranks sum test (one-sided). Generally, drug-induced growth inhibitions of 20% or greater are significantly different (p ≤ 0.05) from the group receiving E2 alone. Each AFPep analogue was evaluated for antiuterotrophic activity in three or more experiments, and the mean growth inhibition ± the standard error for each analogue is reported in Table 2.

Results

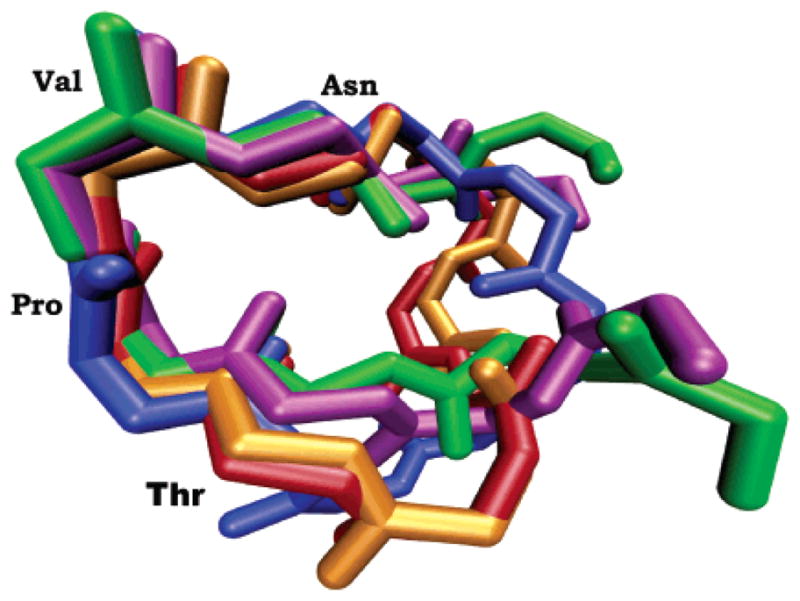

Figure 1 shows the conservation of conformational space of the five active 8-mer and cyclic 9-mer AFP-derived peptides previously shown14,15 to have antiestrogenic activity. This figure shows the overlay of the most representative peptide geometries obtained from the conformational family that displays the common reverse turn motif in each REMD simulation. Four amino acids, TPVN, are conserved in the conformational space of the active 8-mers and cyclic 9-mers. The TPVN sequence forms a reverse turn within the longer peptides, a structure that is conserved across all five REMD simulations. In a Type I reverse β-turn, four amino acids form a turn structure, which is defined by the phi (φ) and psi (ψ) angles of the second and third amino acids. An ideal Type I β-turn has φ/ψ values of −60° and −30° for the second amino acid and φ/ψ values of −90° and 0° for the third amino acid in the four amino acid turn sequence. As displayed in Table 1, the cyclic-[EMTPVN-PGQ] and EMTPVNPG peptides have average φPro/ψPro and φVal/ψVal values that fall within 13° of a Type I turn. The other three simulations of the 8-mer and 9-mer peptides have similar values (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overlay of the cyclic-[EKTPVNPGN] (red), cyclic-[EKTPVN-PGQ] (blue), cyclic-[EMTPVNPGQ] (orange), and the EMTPVNPG (green) and EMTPTNPG (purple) peptides from REMD simulations. Each structure represents the β-turn motif sampled during the dynamics.

Table 1.

Average φ/ψ Angle Values for the Second and Third Amino Acids for Five Different Sequencesa

| φ2 | ψ2 | φ3 | ψ3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| type I β-turn | −60 | −30 | −90 | 0 | |

| cyclic-[EMTPVNPGQ] | −68 | −16 | −96 | −9 | |

|

| |||||

| EMTPVNPGb | −68 | −17 | −94 | −11 | |

|

| |||||

| TPVNP | −65 | −19 | −95 | −12 | |

| TPVN | −68 | −19 | −88 | −11 | |

|

| |||||

| PVNP | 68% | −89 | −8 | −110 | 115 |

| 27% | −108 | 141 | −104 | 128 | |

The four residues in boldface define amino acids one through four for each peptide. The φ/ψ angle values for the second and third amino acids of a four amino acid sequence are diagnostic for a β-turn structure.

The sequence of the AFPep peptide.

We ran REMD simulations for the TPVN, TPVNP, and PVNP analogues to explore the conformational space sampled by these four and five amino acid peptides. The TPVN and TPVNP peptides form the same reverse turn seen in the larger, active peptides. As displayed in Table 1, the TPVNP and TPVN analogues have φPro/ψPro values of approximately −67° and −19°, while the φVal/ψVal values are approximately −91° and −12°. In contrast, the average φVal/ψVal, and φAsn/ψAsn values for the two dominant conformations of the PVNP peptide reveal that none of the three structures is a turn (Table 1). The structure that is sampled for 68% of the REMD simulations has φVal/ψVal angles of −89° and −8° and φAsn/ψAsn angles of −110° and 115°. The structure sampled for 27% of the REMD simulation has φVal/ψVal angles of −108° and 141° and φAsn/ψAsn angles of −104° and 128°. Consideration of the average asparagine angles alone shows that the PVNP peptide does not form a turn structure.

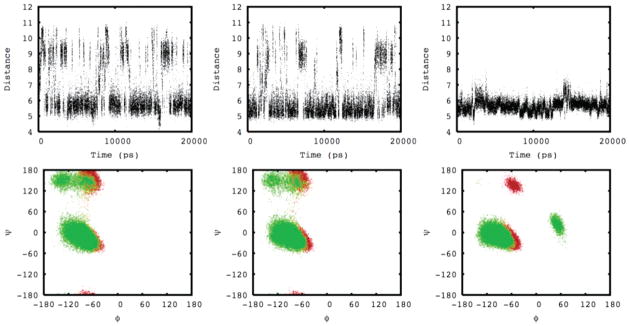

The representative dynamics of three analogues containing the conserved TPVN sequence can be visualized in Figure 2. The top graphs display the distance between the Cα atoms of the threonine and asparagine residues, serving as a definitive diagnostic for a β-turn. Twenty-five percent of β-turns do not have an intraturn hydrogen bond, so an alternative definition of a β-turn is that the distance between the Cα carbon atoms of amino acid residues one and four in the tetrapeptide sequence is less than 7 Å.94 The TPVN tetrapeptide has a Cα(T) − Cα(N) distance less than 7 Å for 64% of the simulation, indicating a β-turn. The TPVNP pentapeptide adopts the turn structure for 74% of the simulation, and the cyclic-[EMTPVNPGQ] peptide is locked into the turn structure for 99% of the simulation. The bottom graphs in Figure 2 show the corresponding three-dimensional plots of φ versus ψ. These plots reveal the dynamics of the φ/ψ values for proline (red) and valine (green) amino acids throughout the simulation for these three peptides. These plots confirm that these three peptides adopt a β-turn conformation over the course of the simulation.

Figure 2.

The top graphs depict the distances between the conserved threonine and asparagine Cα atoms as a function of simulation time for the TPVN (left), TPVNP (middle), and cyclic-[EMTPVNPGQ] (right) peptides. The bottom graphs depict their corresponding φ (x-axis) and ψ (y-axis) angles as a function of simulation time for the conserved proline (red) and valine (green) amino acids.

Several 4-mer and 5-mer peptide analogues containing the TPVN sequence, or a similar sequence with hydroxyproline (O) substituted for proline, were synthesized, tested, and compared to the original 8-mer peptides for biological activity. As shown in Table 2, biological activity, as defined by inhibition of estrogen-stimulated growth of an immature mouse uterus, was retained in the TPVN and TOVN 4-mers and even more so in the TPVNP and TOVNO 5-mers.

The OVNO and PVNP analogues, which were thought to represent the pharmacophore region of AFPep,15 did not show significant activity. Similarly, five amino acid peptides containing the amino or carboxyl end of AFPep did not have biological activity (bottom of Table 2). The 7-mer, EMTPVNP, was slightly less active than AFPep and the smaller TPVNP.

The figures reveal why the TPVNP and TPVN analogues are active. All active peptides have a conserved reverse β-turn motif. These β-turns are formed by the TPVN sequence, with a hydrogen bond formed between the carbonyl oxygen of the first amino acid and the amide hydrogen of the fourth amino acid. The conservation of proline in the second position favors the formation of a reverse turn. This proline is conserved in human, gorilla, chimpanzee, horse, rat, and mouse AFP sequences.15

Discussion

We have used REMD simulations to sample the conformational space of 8-mer and 9-mer AFP-derived peptides that have antiestrogenic and antibreast cancer activity. We discovered that an identical four amino acid sequence had minimal conformational flexibility, suggesting that this region is essential for the biological activities of these peptides. The TPVN, TOVN, TPVNP, and TOVNO sequences were subsequently synthesized and were found to be biologically active. This is a novel finding because Mesfin et al.11 and DeFreest et al.15 had concluded that the 8-mer, EMTPVNPG, was the minimum number of residues that an AFP-derived peptide can have and still retain significant antiestrogenic activity. This conclusion was based on the findings that the 7-mers, MTPVNPG and EMTPVNP, had relatively less biological activity than the 8-mers. These investigators concluded that the 8-mer peptide assumed a pseudo-cyclic conformation, that the middle of the peptide contained its pharmacophore region (the PVNP sequence), and that the exterior residues were essential for holding the peptide in its active conformation. The 7-mers lost activity, which was assumed to result from the loss of hydrogen bonding between the first and eighth amino acid residues, suggesting that full activity must require at least eight amino acid residues. Indeed the 5-mer, EMTPV, was synthesized and found to have no significant activity, which supported their conclusion that the 8-mer sequence was the minimal sequence for biological activity.14 Furthermore, guided by this hydrogen bond hypothesis, cyclic 9-mers were also synthesized and shown to possess significant biological activity.93 We tested this pseudocyclic conformation hypothesis by examining the percentage of hydrogen bond formation between the first and eighth amino acids for each simulation containing seven or eight amino acid residues. For all 8-mer and 7-mer simulations, hydrogen bond formation between the first and the last amino acids is observed for less than 1% of the simulation if the distance definition for a hydrogen bond is set at 2.3 Å. This result is contrary to the original hypothesis.

The REMD studies reported herein lead to a substantially different conclusion regarding the requirement for peptide activity. These studies indicate that the key region is the TPVN sequence, since this structure retains the turn conformation common in every active peptide; the PVNP peptide does not sample a reverse turn structure (Table 1) and shows insignificant activity (Table 2). The above discovery has profound consequences. First, a 4-mer or a 5-mer peptide that retains biological activity is less expensive to synthesize than an 8-mer or a 9-mer peptide, and these smaller analogues are more druglike. Second, knowing the conformational space occupied by the 4-mer provides insight into the topology of the unknown receptor site for these peptides. Based on this study, the receptor site topology for the AFP analogue peptides is predicted to be a mirror image of a reverse β-turn. We note that the β-turn solution conformation of these peptides may not be retained when bound in the active site. However the high correlation between activity and β-turn conformation coupled with the entropic cost for altering the conformation upon binding gives us confidence that the receptor topology will accommodate a β-turn conformation. Previous substitutions in the 8-mer sequences reveal that when threonine, leucine, or isoleucine is substituted for valine, biological activity is retained, while substitution of valine with D-valine or alanine results in loss of activity. This implies that the topology of the receptor is stereospecific, and branched amino acids are essential for creation of hydrophobic forces that bind the receptor to the peptide. Finally, it leads to a different conceptual approach for stabilization of these peptides and the development of peptidomimetics. Peptidomimetics can be designed based on the active 4-mer and 5-mer peptides, with REMD used to ensure that the steric and electronic nature of the peptides is retained. Developing a peptidomimetic may not be necessary, for as long as the peptides are bioavailable they have the advantage of a lower probability of side effects compared to peptide mimics. The AFP 8-mer and cyclic 9-mer peptides have already been shown to be nontoxic and bioavailable in mice.2 Cancer xenograft assays in mice involved the administration of 8-mer and cyclic 9-mer peptides twice a day for 30 days, during which time tumor growth was significantly inhibited, and there was no change in mouse body weight, cage activity, fur texture, or body temperature. In addition there were no changes in size or appearance of major organs relative to the control group. The uterine growth studies revealed that these peptides, unlike tamoxifen, did not stimulate murine uterine growth; indeed they inhibit the uterine stimulated growth induced by tamoxifen.2,8 Thus, the peptides derived from AFP represent a new class of potential breast cancer drugs, which are active through a new, yet to be discovered, receptor.

Because there is excellent correlation between the uterine growth assay and the human breast cancer xenograft assay with regard to AFPep peptide inhibition of estrogen-stimulated growth,2,14 the TOVNO, TPVNP, TOVN, and TPVN analogues that are all active in the uterine growth assay are predicted to inhibit human breast cancer growth. We have begun the xenograft assays on these analogues to evaluate this prediction.

Conclusions

We have applied and demonstrated for the first time that REMD simulations can be used as a novel lead compound design tool. We have shown that REMD predicts a common conformation that is shared between the active linear 8-mer and cyclic 9-mer peptides. The predicted common conformation is a conserved reverse β-turn, and the smaller peptide analogues TOVNO, TPVNP, TOVN, and TPVN also contain the same conserved reverse turn. These analogues are shown to inhibit estrogen-dependent cell growth in a mouse uterine growth assay, through interaction with a yet to be discovered key receptor, and are predicted to inhibit human breast cancer. The 5-mer and 4-mer peptides are new discoveries that may lead to promising new antibreast cancer drugs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carlos Simmerling and Adrian Roitberg for insightful discussions of the replica exchange methodology and Steve Festin for his contributions. Acknowledgment is made to the donors of the Petroleum Research Fund, administered by the ACS, to the Research Corporation, to the NIH (R01 CA102540 and R15 CA115524), to the New York State Breast Cancer Research and Education fund through Department of Health Contract C017922, to the DOD (BC031067 and W81XWH-05-1-0441), and to Hamilton College for support of this work. This project was supported in part by NSF Grant CHE-0457275 and by NSF Grants CHE-0116435 and CHE-0521063 as part of the MERCURY high-performance computer consortium (http://mercury.chem.hamilton.edu). This work was first presented at the 2006 International Symposium on Theory and Computations in Molecular and Materials Sciences, Biology and Pharmacology, on February 26, 2006.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society: Atlanta. American Cancer SocietyWebsite. 2006;2006 http://www.cancer.org/docroot/MED/content/MED_1_1_Most-Requested_Graphs_and_Figures_2006.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett JA, Mesfin FB, Andersen TT, Gierthy JF, Jacobson HI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2211–2215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251667098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abelev GI. Adv Cancer Res. 1971;14:295–358. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60523-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mizejewski GJ. Exp Biol Med. 2001;226:377–408. doi: 10.1177/153537020122600503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dudich E, Semenkova L, Gorbatova E, Dudich I, Khromykh L, Tatulov E, Grechko G, Sukhikh G. Tumor Biol. 1998;19:30–40. doi: 10.1159/000029972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobson HI, Bennett JA, Mizejewski GJ. Cancer Res. 1990;50:415–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett JA, Zhu SJ, Pagano-Mirarchi A, Kellom TA, Jacobson HI. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:2877–2884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parikh RR, Gildener-Leapman N, Narendran A, Lin HY, Lemanski N, Bennett JA, Jacobson HI, Andersen TT. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8512–8520. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobson HI, Janerich DT. Biological Activities of Alpha-Fetoprotein. CRC; Boca Raton, FL: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richardson BE, Hulka BS, David-Peck JL, Hughes CL, Van den Berg BJ, Christianson RE, Calvin JA. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:719–727. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Festin SM, Bennett JA, Fletcher PW, Jacobson HI, Shaye DD, Andersen TT. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1427:307–314. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(99)00030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisele LE, Mesfin FB, Bennett JA, Andersen TT, Jacobson HI, Vakharia DD, MacColl R, Mizejewski GJ. J Pept Res. 2001;57:539–546. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.2001.00903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisele LE, Mesfin FB, Bennett JA, Andersen TT, Jacobson HI, Soldwedel H, MacColl R, Mizejewski GJ. J Pept Res. 2001;57:29–38. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.2001.00791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mesfin FB, Bennett JA, Jacobson HI, Zhu SJ, Andersen TT. Biochim Biophys Acta (Molecular Basis of Disease) 2000;1501:33–43. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(00)00008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeFreest LA, Mesfin FB, Joseph L, McLeod DJ, Stallmer A, Reddy S, Balulad SS, Jacobson HI, Andersen TT, Bennett JA. J Pept Res. 2004;63:409–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.2004.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Villacampa MJ, Moro R, Naval J, Faillycrepin C, Lampreave F, Uriel J. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;122:1322–1327. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)91236-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugita Y, Okamoto Y. Chem Phys Lett. 1999;314:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitsutake A, Sugita Y, Okamoto Y. Biopolymers. 2001;60:96–123. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2001)60:2<96::AID-BIP1007>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Case DA, et al. AMBER Version 8 Molecular Dynamics Program. University of California; San Francisco, CA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou RH, Berne BJ, Germain R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:14931–14936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201543998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou RH. Proteins: Struct, Funct, Genet. 2003;53:148–161. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou RH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13280–13285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2233312100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seibert MM, Patriksson A, Hess B, van der Spoel DJ. Mol Biol. 2005;354:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paschek D, Gnanakaran S, Garcia AE. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6765–6770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408527102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Im W, Brooks CL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6771–6776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408135102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murata K, Sugita Y, Okamoto Y. J Theor Comput Chem. 2005;4:411–432. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murata K, Sugita Y, Okamoto Y. J Theor Comput Chem. 2005;4:433–448. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nymeyer H, Gnanakaran S, Garcia AE. Numerical Computer Methods, Pt D. 2004;383:119. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)83006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andrec M, Felts AK, Gallicchio E, Levy RM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6801–6806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408970102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernard D, Coop A, Mackerell AD. J Med Chem. 2005;48:7773–7780. doi: 10.1021/jm050785p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malolepsza E, Boniecki M, Kolinski A, Piela L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:7835–7840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409389102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Best RB, Clarke J, Karplus MJ. Mol Biol. 2005;349:185–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gnanakaran S, Garcia AE. Proteins: Struct, Funct, Bioinf. 2005;59:773–782. doi: 10.1002/prot.20439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nymeyer H, Woolf TB, Garcia AE. Proteins: Struct, Funct, Bioinf. 2005;59:783–790. doi: 10.1002/prot.20460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshida K, Yamaguchi T, Okamoto Y. Chem Phys Lett. 2005;412:280–284. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baumketner A, Shea JE. Biophys J. 2005;89:1493–1503. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.059196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nguyen PH, Mu YG, Stock G. Proteins: Struct, Funct, Bioinf. 2005;60:485–494. doi: 10.1002/prot.20485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Snow CD, Sorin EJ, Rhee YM, Pande VS. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2005;34:43–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.34.040204.144447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang W, Wu C, Duan Y. J Chem Phys. 2005:123. doi: 10.1063/1.2056540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ravindranathan KP, Gallicchio E, Levy RM. J Mol Biol. 2005;353:196–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nishino M, Sugita Y, Yoda T, Okamoto Y. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:5425–5429. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu P, Kim B, Friesner RA, Berne BJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13749–13754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506346102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roe DR, Hornak V, Simmerling C. J Mol Biol. 2005;352:370–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nguyen PH, Stock G, Mittag E, Hu CK, Li MS. Proteins: Struct, Funct, Bioinf. 2005;61:795–808. doi: 10.1002/prot.20696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen Z, Xu Y. Proteins: Struct, Funct, Bioinf. 2006;62:539–552. doi: 10.1002/prot.20774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang ZX, Zhang W, Wu C, Lei HX, Cieplak P, Duan Y. J Comput Chem. 2006;27:781–790. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen JH, Im WP, Brooks CL. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3728–3736. doi: 10.1021/ja057216r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Affentranger R, Tavernelli I, Di Iorio EE. J Chem Theory Comput. 2006;2:217–228. doi: 10.1021/ct050250b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okur A, Wickstrom L, Layten M, Geney R, Song K, Hornak V, Simmerling C. J Chem Theory Comput. 2006;2:420–433. doi: 10.1021/ct050196z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baumketner A, Bernstein SL, Wyttenbach T, Bitan G, Teplow DB, Bowers MT, Shea JE. Protein Sci. 2006;15:420–428. doi: 10.1110/ps.051762406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bunagan MR, Yang X, Saven JG, Gai F. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:3759–3763. doi: 10.1021/jp055288z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jang S, Shin S. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:1955–1958. doi: 10.1021/jp055568e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jang S, Kim E, Pak Y. Proteins: Struct, Funct, Bioinf. 2006;62:663–671. doi: 10.1002/prot.20771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang J, Qin M, Wang W. Proteins: Struct, Funct, Bioinf. 2006;62:672–685. doi: 10.1002/prot.20813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ravindranathan KP, Gallicchio E, Friesner RA, McDermott AE, Levy RM. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:5786–5791. doi: 10.1021/ja058465i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trebst S, Troyer M, Hansmann UHE. J Chem Phys. 2006:124. doi: 10.1063/1.2186639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Larios E, Pitera JW, Swope WC, Gruebele M. Chem Phys. 2006;323:45–53. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Soto P, Baumketner A, Shea JE. J Chem Phys. 2006:124. doi: 10.1063/1.2179803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yadav MK, Leman LJ, Price DJ, Brooks CL, Stout CD, Ghadiri MR. Biochemistry. 2006;45:4463–4473. doi: 10.1021/bi060092q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kmiecik S, Kurcinski M, Rutkowska A, Gront D, Kolinski A. Acta Biochim Pol. 2006;53:131–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van der Spoel D, Seibert MM. Phys Rev Lett. 2006:96. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.238102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baumketner A, Bernstein SL, Wyttenbach T, Lazo ND, Teplow DB, Bowers MT, Shea JE. Protein Sci. 2006;15:1239–1247. doi: 10.1110/ps.062076806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nanias M, Czaplewski C, Scheraga HA. J Chem Theory Comput. 2006;2:513–528. doi: 10.1021/ct050253o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mu YG, Nordenskiold L, Tam JP. Biophys J. 2006;90:3983–3992. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.076406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wei GH, Shea JE. Biophys J. 2006;91:1638–1647. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.079186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wickstrom L, Okur A, Song K, Hornak V, Raleigh DP, Simmerling CL. J Mol Biol. 2006;360:1094–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ho BK, Dill KA. PLoS Comp Biol. 2006;2:228–237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li PC, Huang L, Makarov DE. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:14469–14474. doi: 10.1021/jp056422i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang J, Gu Y, Liu HY. J Chem Phys. 2006:125. doi: 10.1063/1.2346681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hughes RM, Waters ML. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16:514–524. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Baumketner A, Shea JE. Theor Chem Acc. 2006;116:262–273. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Daura X. Theor Chem Acc. 2006;116:297–306. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kokubo H, Okamoto Y. Mol Simul. 2006;32:791–801. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Grater F, de Groot BL, Jiang HL, Grubmuller H. Structure. 2006;14:1567–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li HZ, Li GH, Berg BA, Yang W. J Chem Phys. 2006:125. doi: 10.1063/1.2354157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Baumketner A, Shea JE. J Mol Biol. 2006;362:567–579. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu P, Huang XH, Zhou RH, Berne BJ. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:19018–19022. doi: 10.1021/jp060365r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sugita Y, Miyashita N, Yoda T, Ikeguchi M, Toyoshima C. doi: 10.1021/bi061071z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kameda T, Takada S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:17765–17770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602632103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lou HF, Cukier RI. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:24121–24137. doi: 10.1021/jp064303c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lwin TZ, Luo R. Protein Sci. 2006;15:2642–2655. doi: 10.1110/ps.062438006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Periole X, Mark AE. J Chem Phys. 2007:126. doi: 10.1063/1.2404954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bu LT, Im W, Charles LI. Biophys J. 2007;92:854–863. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.095216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liwo A, Khalili M, Czaplewski C, Kalinowski S, Oldziej S, Wachucik K, Scheraga HA. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:260–285. doi: 10.1021/jp065380a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jang S, Kim E, Pak Y. Proteins: Struct, Funct, Bioinf. 2007;66:53–60. doi: 10.1002/prot.21173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Case DA, Cheatham TE, Darden T, Gohlke H, Luo R, Merz KM, Onufriev A, Simmerling C, Wang B, Woods RJ. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1668–1688. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hornak V, Abel R, Okur A, Strockbine B, Roitberg A, Simmerling C. Proteins: Struct, Funct, Genet. 2006;65:712–725. doi: 10.1002/prot.21123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cramer CJ. Essentials of Computational Chemistry: Theories and Models. 2. John Wiley & Sons Ltd; Chichester, U.K: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Onufriev A, Bashford D, Case DA. J Phys Chem B. 2000;104:3712–3720. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhou RH, Berne BJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12777–12782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142430099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Geney R, Layten M, Gomperts R, Hornak V, Simmerling C. J Chem Theory Comput. 2006;2:115–127. doi: 10.1021/ct050183l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lexa KW, Alser KA, Salisburg AM, Ellens DJ, Hernandez L, Bono SJ, Derby JR, Skiba JG, Feldgus S, Kirschner KN, Shields GC. Int J Quantum Chem. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mesfin FB, Andersen TT, Jacobson HI, Zhu S, Bennett JA. J Pept Res. 2001;58:246–256. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.2001.00922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chou KC. Anal Biochem. 2000;286:1–16. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]