Abstract

Purinergic signaling regulates a diverse and biologically relevant group of processes in the liver. However, progress of research into functions regulated by purinergic signals in the liver has been hampered by the complexity of systems probed. Specifically, there are multiple liver cell subpopulations relevant to hepatic functions, and many of these have been effectively modeled in human cell lines. Furthermore, there are more than 20 genes relevant to purinergic signaling, each of which has distinct functions. Hence, we felt the need to categorize genes relevant to purinergic signaling in the best characterized human cell line models of liver cell subpopulations. Therefore, we investigated the expression of adenosine receptor, P2X receptor, P2Y receptor, and ecto-nucleotidase genes via RT-PCR in the following cell lines: LX-2, hTERT, FH11, HepG2, Huh7, H69, and MzChA-1. We believe that our findings will provide an excellent resource to investigators seeking to define functions of purinergic signals in liver physiology and liver disease pathogenesis.

Keywords: Liver cell line, Purinergic signaling, Hepatic stellate cell, Hepatocyte, Cholangiocyte

Introduction

One of the fundamental aspects of liver physiology and disease pathogenesis is the diversity of resident cell types involved. Liver cell subpopulations include such distinct specialized cell types as parenchymal cells or hepatocytes [1] and non-parenchymal cells including, cholangiocytes [2], portal fibroblasts [3], hepatic stellate cells (HSC) [4], mesothelial cells [5], sinusoidal endothelial cells [6], and immune cells [7, 8]. For most of these cell types, the establishment of various immortalized cell lines in human and rodent species represents a major experimental advance, providing in vitro models for the study of liver functions in cell-specific manner. Most of these cell lines have been effectively characterized and are increasingly used in fundamental experiments probing the basic biology of liver under normal and pathological conditions.

The diverse roles of purinergic signals in the liver have been increasingly appreciated in recent years [9–11]. For instance, purinergic signals regulate proliferation [12–14] and glucose release [15] in hepatocytes; secretion [16, 17], proliferation [18], and mechanosensation [19] in cholangiocytes; and fibrogenic activity [20, 21] and properties in HSC [22, 23]. Of note, the purinergic signaling system is quite diverse, including multiple subtypes of G protein-coupled receptors for adenosine P1 receptors [24] and nucleotide P2Y receptors [25], nucleotide P2X ligand-gated ion channels [26], and a variety of plasma membrane-bound ecto-enzymes that regulate extracellular nucleotide/nucleoside levels, namely ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolases (ENTPDases) [27, 28], CD73/ecto-5′-nucleotidase [29, 30], and tissue-non-specific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP) [31]. Thus, there is tremendous, almost overwhelming, complexity both in the relevant cell types and purinergic signaling systems relevant to liver physiology and disease [32].

To help remedy this concern, we set out to categorize the specific genes relevant to purinergic signaling in well-characterized human liver cell lines. We propose that the data collection created from this work will be of value to all investigators interested in the role of purinergic signaling in the liver.

Materials and methods

Materials/reagents

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles medium (DMEM), DMEM/F12 medium, fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin-streptomycin (10,000 U/mL) antibiotic solution, human recombinant insulin, and zinc solution were purchased from Gibco (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Adenine, epinephrine, triiodothyronine-transferrin, epidermal growth factor, and hydrocortisone reagents used for cell culture medium were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis. MO). Deoxyribonuclease 1 (DNAse 1) and nuclease-free water were purchased from Ambion (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Qubit RNA Assay Kit was purchased from Invitrogen (Life Technologies), and iScript RT-Supermix kit was purchased from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). RNeasy Plus total RNA extraction Kit, Qiashredder homogenizer spin columns, and TopTaq polymerase chain reaction Mastermix Kit were purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). Human Liver Poly A + RNA was purchased from Clontech (Mountain View, CA).

Cell lines and culture conditions

LX-2 [33] (kindly provided by Dr. Scott Friedman, Mont Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York), hTERT [34] (kindly provided by Dr. Tatiana Kisseleva, University of California at San Diego, San Diego, CA), FH11 [35] (kindly provided by Dr. Meena Bansal, Mont Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York), Mz-Cha-1 [36], HepG2 [37], and Huh7 [37] (kindly provided by Dr. Michael Nathanson, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT) cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10 % fetal bovine serum and 1 % antibiotic. H69 cells [38] (kindly provided by Dr. Doug Jefferson, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, MA) were cultured, as previously described [38], in a mixture (1:1, volume/volume) of DMEM and DMEM/F12 media containing 10 % FBS, 1 % antibiotics, 1 % adenine, 0.125 % insulin, 0.1 % epinephrine, 0.1 % triiodothyronine-transferrin, 0.33 % epidermal growth factor, and 0.267 % hydrocortisone. All cell cultures were maintained at 37 °C with a 5.0 % CO2, humidified environment, and passaged every 2–3 days.

Total RNA extraction and RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from human liver cell lines (LX-2, hTERT, FH11, HepG2, Huh7, H69, and Mz-Cha-1) in culture using RNeasy Plus Kit following homogenization with supplementary Qiashredder spin columns according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA sample concentration was quantified using the Qubit RNA Assay Kit with a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies). In order to remove any genomic DNA contamination from isolated RNA samples, 1 μg of total RNA was digested with DNase 1 according to the manufacturer’s instructions before performing the reverse transcription reaction using the iScript RT Supermix according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The product of the RT reaction was diluted 1:10 with nuclease-free water; 1 μl of that diluted RT reaction sample was further used for PCR amplification using the TopTaq Master Mix Kit as DNA polymerase. PCR amplification was performed with the following protocol for the PCR reactions: Initialization at 94 °C for 2 min followed by 35 cycles of 30 s denaturation at 94 °C, 30 s annealing at 60 °C (except for all adenosine receptors at 62 °C and nucleotide P2Y4 receptor at 54 °C), and 30 s elongation at 72 °C; the amplification was then completed with a 10-min final elongation at 72 °C, using an S1000 Thermo Cycler (Bio-Rad). The primer sequences used for the semi-quantitative RT-PCR reactions are listed in Table 1. Amplification products were visualized on 3 % agarose gels via ethidium bromide staining.

Table 1.

Sequences of PCR primers used for expression analysis of human purinergic genes

| Targeted gene symbol | Forward primer sequence | Reverse primer sequence | Product size (bp) | Gene accession number | Positive Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenosine receptors | |||||

| ADORA1 | CCTCCATCTCAGCTTTCCAG | AGTAGGTCTGTGGCCCAATG | 222 | NM_000674 | Brain |

| ADORA2a | AACCTGCAGAACGTCACCAA | GTCACCAAGCCATTGTACCG | 245 | NM_000675 | Brain |

| ADORA2b | GAGACACAGGACGCGCTGTACG | CGGGTCCCCGTGACCAAACT | 353 | NM_000676.2 | Brain |

| ADORA3 v1, v3 | GACACAGGGAACCAGCTCAT | TGCAGCTTCTGGTTTTGTTG | 199 | NM_020683 | Brain |

| ADORA3 v2 | TGTTTGGCTGGAACATGAAA | ATAGATGGCGCACATGACAA | 155 | NM_000677 | Brain |

| P2X receptors | |||||

| P2RX1 | GCTACGTGGTGCAAGAGTCA | GTAGTTGGTCCCGTTCTCCA | 215 | NM_002558 | Brain |

| P2RX2 | GCTCCTTTCCATCTCACTGG | GGAAGTGAGCAGCCCTGTAG | 237 | NM_170682.3 | Brain |

| P2RX3 | ACAGCCAGGGACATGAAGAC | AGCCGGGTGAAGGAGTATTT | 186 | NM_002559 | Liver |

| P2RX4 | GAGATTCCAGATGCGACC | GACTTGAGGTAAGTAGTGG | 296 | NM_002560 | Brain |

| P2RX5 | CTGGTCGTATGGGTGTTCCT | CTGGGCTGGAATGACGTAGT | 159 | NM_002561 | Brain |

| P2RX6 | ACTCTGTGTGGAGGGAGCTG | GGCAAGTGGGTGTCAGAACT | 151 | NM_005446.3 | Brain |

| P2RX7 | AAGCTGTACCAGCGGAAAGA | GCTCTTGGCCTTCTGTTTTG | 202 | NM_002562 | Brain |

| P2Y receptors | |||||

| P2RY1 | AAAACTAGCCCCCTGCAACT | GATCTGATGCCGGATGAACT | 153 | NM_002563 | Brain |

| P2RY2 | CCACCTGCCTTCTCACTAGC | TGGGAAATCTCAAGGACTGG | 163 | NM_176072 | Liver |

| P2RY4 | CGTCTTCTCGCCTCCGCTCTCT | GCCCTGCACTCATCCCCTTTTCT | 411 | NM_002565 | Liver |

| P2RY6 | AGCTGGGCATGGAGTTAAGA | GCTGACTGGGACCTCTCAAG | 139 | NM_176797 | Liver |

| P2RY11 | CCTCTACGCCAGCTCCTATG | CACTGCGGCCATGTAGAGTA | 211 | NM_002566 | Brain |

| P2RY12 | TTTGCCCGAATTCCTTACAC | ATTGGGGCACTTCAGCATAC | 192 | NM_022788 | Brain |

| P2RY13 | CCCCTGGTACACTTGGAAGA | TACAGAGGAGGGGGTGATTG | 125 | NM_176894.2 | Liver |

| P2RY14 | TCTTTGGGCTCATCAGCTTT | TCCGTCCCAGTTCACTTTTC | 213 | NM_014879 | Brain |

| Ecto-nucleotidases | |||||

| ENTPD1 | CAGAACAAAGCATTGCCAGA | CCACATCCAGAACCCTGTCT | 340 | NM_001776.4 | Brain |

| ENTPD2 | TCAATCCAGCTCCTTGAACC | TCCCCAGTACAGACCCAGAC | 167 | NM_203468.1 | Brain |

| ENTPD3 | TTGACCTCAGGGCTCAGTTT | TGAGGGGGTTCACTGCTTAC | 159 | NM_001248.2 | Brain |

| ENTPD8 | ACTGGGCTACATGCTGAACC | GCACCATGAACACCACTTTG | 107 | NM_198585.2 | Liver |

| NT5E | TGGAACCACGTATCCATGTG | ATGCTCAAAGGCCTTCTTCA | 171 | NM_002526 | Brain |

| ALPL | CTCTCCAAGACGTACAACACCAA | ATGGTGCCCGTGGTCAAT | 735 | NM_000478.4 | Brain |

v1, v2, v3 distinct genetic variants

Results

Human LX-2, hTERT, and FH11 hepatic stellate cell lines

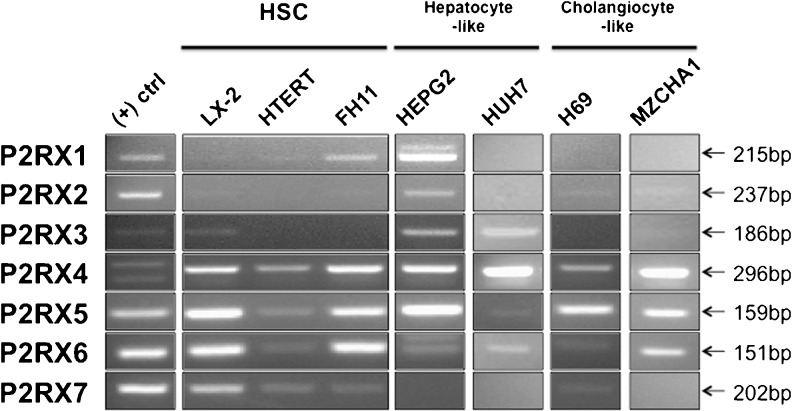

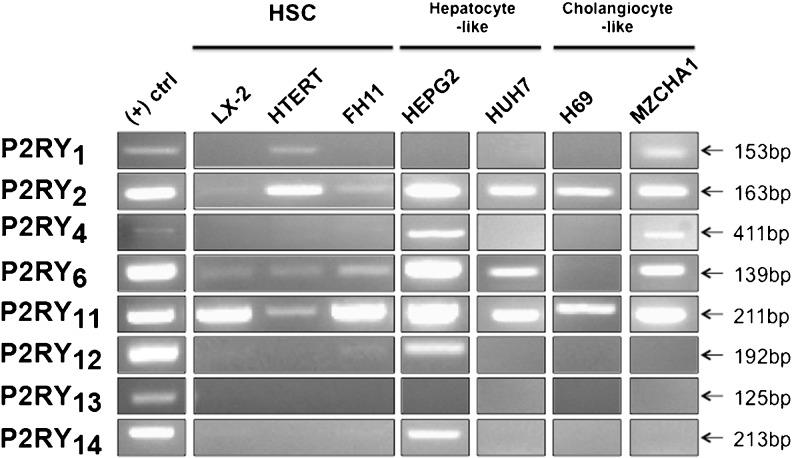

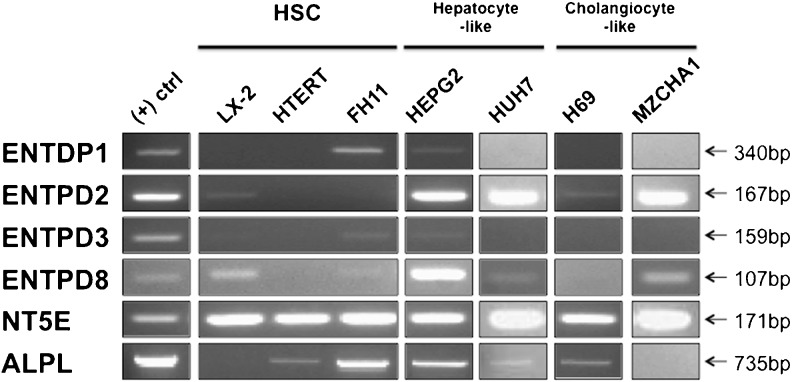

LX-2 [33] and hTERT cells [34] are immortalized activated human HSCs cell lines, while FH11 cells [35] are primary activated human HSC isolated from liver explants. The expression of adenosine receptors on HSC cell lines varied considerably (as seen in Fig. 1). The LX-2, hTERT, and FH11 cells expressed all four adenosine receptors (A1, A2a, A2b, and A3). The expression of P2X receptors by HSC cell lines was consistent (Fig. 2) with a few exceptions. It is interesting to note that the hTERT cell line exhibited no expression of P2X2 and P2X3 and that P2X3 was expressed only by LX2 cells. In comparison to the expression of adenosine and P2X receptors, HSC cell lines did not express a wide variety of P2Y receptors (Fig. 3). Neither LX-2, hTERT, nor FH11 cells expressed P2Y4 or P2Y13 genes. In contrast, the P2Y2, P2Y6, and P2Y11 receptors were detected in all three HSC cell lines. P2Y1 expression was detected solely in hTERT cells. The expression of ecto-nucleotidases in HSC cell lines is presented in Fig. 4. hTERT cells showed no evidence of ENTPDase expression. CD73 was expressed by all three cell lines, while TNAP was expressed by FH11 cells and hTERT cells but was absent in LX-2 cells.

Fig. 1.

Adenosine receptor genes expression in human liver cell lines. RT-PCR analysis was performed on LX-2, HTERT, Fh11, HEPG2, HUH7, H69, and MZCHA1 cell cDNA samples. Human brain or liver cDNA was used as positive control (see Table 1). Negative control was obtained by replacing cDNA by deionized water. RT-PCR products were visualized on a UV transilluminator with ethidium bromide staining

Fig. 2.

P2X receptor genes expression in human liver cell lines. RT-PCR analysis was performed as described in Fig. 1

Fig. 3.

P2Y receptor genes expression in human liver cell lines. RT-PCR analysis was performed as described in Fig. 1

Fig. 4.

Ecto-nucleotidase genes expression in human liver cell lines. RT-PCR analysis was performed as described in Fig. 1

Human HepG2 and Huh7 hepatocyte-like cells

HepG2 [37] and Huh7 [39] cell lines are derived from excised hepatocellular carcinomas. HepG2 cells expressed all four adenosine receptors. Expression of adenosine receptors by Huh7 cells was nearly identical to HepG2, although no expression of the A1 receptor was detected (Fig. 1). HepG2 cells expressed all P2X receptors excluding P2X7, yet Huh7 cells expressed only P2X3, P2X4, P2X5, and P2X6 (Fig. 2). HepG2 cells expressed all P2Y receptors with the exception of P2Y1 and P2Y13, while Huh7 cells showed expression of P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y6, and P2Y11, and no expression of P2Y4, P2Y12, P2Y13, or P2Y14 (Fig. 3). Lastly, HepG2 cells expressed all ecto-nucleotidases examined. On the other hand, Huh7 cells expressed all ecto-nucleotidases tested aside from ENTPDase1 and ENTPDase3.

Human H69 and Mz-ChA-1 cholangiocyte-derived cells

H69 cell line [38] was developed through retroviral SV40 transformation of human cholangiocytes, while Mz-ChA-1 cell line [36] is derived from mechanically dissociated gallbladder adenocarcinoma metastases. All adenosine receptors were shown to be expressed by both H69 and MzChA-1 cell lines (Fig. 1). Neither H69 nor MzChA-1 showed expression of P2X1; however, both cell lines showed expression of P2X2, P2X4, P2X5, and P2X6 (Fig. 2). The only P2Y receptors detected in H69 cells were P2Y2 and P2Y11, yet Mz-ChA-1 cells expressed P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, P2Y6, and P2Y11 (Fig. 3). H69 cell ecto-nucleotidase expression was limited to expression of CD73, NTPDase2, and TNAP, while Mz-ChA-1 cells demonstrated NTPDase2, NTPDase8, and CD73 expression (Fig. 4).

Discussion

Purinergic signaling in the liver is biologically relevant. Specifically, purinergic signals contribute to the maintenance of normal liver physiology via regulation of secretory [40, 41] and metabolic [15] functions, as well as disease pathogenesis, via modulation of activation mechanisms in multiple hepatic cell types [21, 42, 43] and of wound healing and inflammatory responses [10, 32, 44]. Furthermore, the ecto-enzymes that control balance of extracellular nucleotides and nucleosides in the liver are equally important in pathological processes such as regeneration [45], injury [46, 47], ischemia/reperfusion [48], and fibrosis [10]. Thus, it is scientifically worthwhile to clarify the cell-specific distribution of the various purinergic signaling components expressed in the liver tissue.

A distinct aspect of the liver that makes its study difficult is the multitude of subcellular populations expressed. Myofibroblasts derived from HSC are the primary effector cells in liver fibrosis [49–51], whereas hepatocytes and cholangiocytes work in coordinated fashion to secrete bile [52] and are primary targets of a variety of liver diseases [53, 54] . Isolation of HSC, hepatocytes, and cholangiocytes is now technically straightforward [55], yet there are good reasons to use cell culture models of each of these cell types. In particular, cultured cells allow greater cell purity, have longer life span, and maintain a more stable phenotype (even upon passaging) than isolated cells. Thus, characterization of the adenosine receptors, nucleotide receptors, and regulatory ecto-enzymes in immortalized cells is worthwhile. Unfortunately, because the purinergic gene array investigated in our study has never been characterized in a systematic fashion in liver cell culture models, we proposed that doing so represents a useful resource to the liver research community.

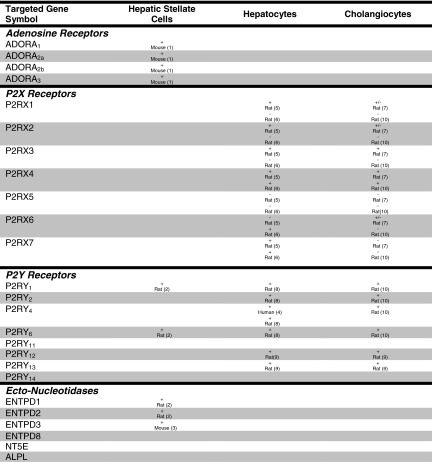

The expression patterns of purinergic signaling genes in the liver cell cultures examined are interesting and occasionally unanticipated. When data are categorized by cell type rather than target gene (Table 2), two important findings become utterly apparent. First, there are distinct differences between HSC cell lines, HepG2 cells (hepatocyte-like), and H69 cells (cholangiocyte-like). Specifically, HSC cell lines (LX-2, hTERT, and FH11) have wide expression of adenosine receptors, but more limited and varied expression of P2X and P2Y receptors. HSC cell line expression of ecto-nucleotidases is more consistent. In contrast, HepG2 cells express all adenosine receptors, all P2X receptors besides P2X7, all P2Y receptors besides P2Y1 and P2Y12, and all ecto-nucleotidases, and Huh7 cells express all adenosine receptors besides A1—a more limited number of P2X and P2Y receptors—and all ecto-nucleotidases besides NTPDase1 and NTPDase3. H69 cells primarily express the A2b receptor, P2X4 and P2X5 receptors, P2Y2 and P2Y11 receptors, and CD73. In contrast, Mz-ChA-1 cells express all adenosinergic receptors, all “traditional” Gq-coupled P2Y receptors plus P2Y11 and NTDPase2, NTPDase8, and CD73; the one consistent area is the complement of P2X receptors expressed by H69 cells and Mz-ChA-1 cells, which is nearly identical. These wide differences in gene expression may be explained in part by the origins of these cells. Precisely, HepG2 cells and Huh7 were derived from distinct tumors may explain, while Mz-ChA-1 cells derive from cholangiocarcinoma cells rather than primary cholangiocytes (as is the case for H69).

Table 2.

mRNA expression of purinergic genes in human liver cell lines

| Targeted gene symbol | Cell line name | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LX-2 | hTERT | FH11 | HEPG2 | HUH7 | H69 | MZCHA1 | |

| Adenosine receptors | |||||||

| ADORA1 | + | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| ADORA2a | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| ADORA2b | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| ADORA3 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| P2X receptors | |||||||

| P2RX1 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| P2RX2 | + | − | + | + | − | + | + |

| P2RX3 | + | − | − | + | + | − | + |

| P2RX4 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| P2RX5 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| P2RX6 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| P2RX7 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − |

| P2Y receptors | |||||||

| P2RY1 | − | + | − | − | + | − | + |

| P2RY2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| P2RY4 | − | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| P2RY6 | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| P2RY11 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| P2RY12 | + | - | + | + | − | − | − |

| P2RY13 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| P2Y14 | + | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| Ecto-nucleotidases | |||||||

| ENTPD1 | − | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| ENTPD2 | + | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| ENTPD3 | + | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| ENTPD8 | + | − | + | + | + | − | + |

| NT5E | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| ALPL | − | + | + | + | + | + | − |

The second finding of particular interest is the dissimilarity in expression pattern among the three HSC cell lines. While some consistent patterns are apparent—expression of A2B, P2X4, P2Y11, and CD73—there are notable differences. To our knowledge, no study has directly compared gene profiles of LX2 cells and hTERT cells, so it is reasonable to expect differences in purinergic gene expression. Since FH11 cells are outgrowths from primary resected cirrhotic livers, it might be expected that they are highly differentiated, with more limited gene expression patterns. Interestingly, FH11 cells express more purinergic genes than hTERT cells. One quite unexpected but consistent observation is that all but LX-2 cells were negative for NTPDase2, which has been reported as a marker for activated HSC [56]; this may be explained by species differences or cell activation state. Also interesting is the consistent expression of P2Y11, which has not been studied previously in activated HSC, and the absence of consistent expression of P2Y1 and P2Y6, which are expressed in activated rat HSC (Table 3). Here, cataloguing purinergic gene expression patterns in HSC cell lines may be of particular importance since it will let investigators choose the proper cell lines for study for specific projects.

Table 3.

Summary of known expression of purinergic signaling mediators

Lastly, there are some quirks worthy of comment. NTPDase8 has been identified as a hepatocyte canalicular marker [57]; however, expression was detected in HSC and Mz-ChA-1 cells as well. In contrast, CD73 is expressed in hepatocytes in normal liver; however, expression is dramatically redistributed to HSC [58] in the cirrhotic liver. Thus, there may be a disconnection between mRNA expression and protein expression in the cell lines we have examined. This possibility underlines the necessity to validate all of the mRNA expression patterns with assays of protein expression or biochemical function whenever possible when using the cell lines examined for physiological studies.

In summary, we have provided, here, useful data to liver investigators with an interest in purinergic signaling. This is not hypothesis-driven research; rather, it is an attempt at creating a tool or guide for our scientific colleagues. We are optimistic that similar time-saving approaches will be taken in other organ systems with comparable complexity as the field progresses. Recent developments in liver purinergic signaling are exciting, and we wish to see the field advance more rapidly.

References

- 1.Treyer A, Musch A. Hepatocyte polarity. Compr Physiol. 2013;3:243–287. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c120009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Hara SP, Tabibian JH, Splinter PL, LaRusso NF. The dynamic biliary epithelia: molecules, pathways, and disease. J Hepatol. 2013;58:575–582. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dranoff JA, Wells RG. Portal fibroblasts: underappreciated mediators of biliary fibrosis. Hepatology. 2010;51:1438–1444. doi: 10.1002/hep.23405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puche JE, Saiman Y, Friedman SL. Hepatic stellate cells and liver fibrosis. Compr Physiol. 2013;3:1473–1492. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c120035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onitsuka I, Tanaka M, Miyajima A. Characterization and functional analyses of hepatic mesothelial cells in mouse liver development. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1525–1535. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeLeve LD. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells and liver regeneration. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1861–1866. doi: 10.1172/JCI66025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kolios G, Valatas V, Kouroumalis E. Role of Kupffer cells in the pathogenesis of liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7413–7420. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i46.7413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhan YT, An W. Roles of liver innate immune cells in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4652–4660. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i37.4652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beldi G, Enjyoji K, Wu Y, Miller L, Banz Y, Sun X, Robson SC. The role of purinergic signaling in the liver and in transplantation: effects of extracellular nucleotides on hepatic graft vascular injury, rejection and metabolism. Front Biosci. 2008;13:2588–2603. doi: 10.2741/2868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaughn BP, Robson SC, Burnstock G. Pathological roles of purinergic signaling in the liver. J Hepatol. 2012;57:916–920. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fausther M, Sevigny J. Extracellular nucleosides and nucleotides regulate liver functions via a complex system of membrane proteins. C R Biol. 2011;334:100–117. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beldi G, Wu Y, Sun X, Imai M, Enjyoji K, Csizmadia E, Candinas D, et al. Regulated catalysis of extracellular nucleotides by vascular CD39/ENTPD1 is required for liver regeneration. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1751–1760. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzales E, Julien B, Serriere-Lanneau V, Nicou A, Doignon I, Lagoudakis L, Garcin I, et al. ATP release after partial hepatectomy regulates liver regeneration in the rat. J Hepatol. 2010;52:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thevananther S, Sun H, Li D, Arjunan V, Awad SS, Wyllie S, Zimmerman TL, et al. Extracellular ATP activates c-jun N-terminal kinase signaling and cell cycle progression in hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2004;39:393–402. doi: 10.1002/hep.20075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emmett DS, Feranchak A, Kilic G, Puljak L, Miller B, Dolovcak S, McWilliams R, et al. Characterization of ionotrophic purinergic receptors in hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2008;47:698–705. doi: 10.1002/hep.22035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dranoff JA, Masyuk AI, Kruglov EA, LaRusso NF, Nathanson MH. Polarized expression and function of P2Y ATP receptors in rat bile duct epithelia. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G1059–G1067. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.4.G1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minagawa N, Nagata J, Shibao K, Masyuk AI, Gomes DA, Rodrigues MA, Lesage G, et al. Cyclic AMP regulates bicarbonate secretion in cholangiocytes through release of ATP into bile. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1592–1602. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jhandier MN, Kruglov EA, Lavoie EG, Sevigny J, Dranoff JA. Portal fibroblasts regulate the proliferation of bile duct epithelia via expression of NTPDase2. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22986–22992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412371200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masyuk AI, Gradilone SA, Banales JM, Huang BQ, Masyuk TV, Lee SO, Splinter PL, et al. Cholangiocyte primary cilia are chemosensory organelles that detect biliary nucleotides via P2Y12 purinergic receptors. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295:G725–G734. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90265.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dranoff JA, Kruglov EA, Abreu-Lanfranco O, Nguyen T, Arora G, Jain D. Prevention of liver fibrosis by the purinoceptor antagonist pyridoxal-phosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulfonate (PPADS) In Vivo. 2007;21:957–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dranoff JA, Ogawa M, Kruglov EA, Gaca MD, Sevigny J, Robson SC, Wells RG. Expression of P2Y nucleotide receptors and ectonucleotidases in quiescent and activated rat hepatic stellate cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G417–G424. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00294.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hashmi AZ, Hakim W, Kruglov EA, Watanabe A, Watkins W, Dranoff JA, Mehal WZ. Adenosine inhibits cytosolic calcium signals and chemotaxis in hepatic stellate cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G395–G401. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00208.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takemura S, Kawada N, Hirohashi K, Kinoshita H, Inoue M. Nucleotide receptors in hepatic stellate cells of the rat. FEBS Lett. 1994;354:53–56. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen JF, Eltzschig HK, Fredholm BB. Adenosine receptors as drug targets—what are the challenges? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:265–286. doi: 10.1038/nrd3955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobson KA, Boeynaems JM. P2Y nucleotide receptors: promise of therapeutic applications. Drug Discov Today. 2010;15:570–578. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.North RA, Jarvis MF. P2X receptors as drug targets. Mol Pharmacol. 2013;83:759–769. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.083758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knowles AF. The GDA1_CD39 superfamily: NTPDases with diverse functions. Purinergic Signal. 2011;7:21–45. doi: 10.1007/s11302-010-9214-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robson SC, Sevigny J, Zimmermann H. The E-NTPDase family of ectonucleotidases: structure function relationships and pathophysiological significance. Purinergic Signal. 2006;2:409–430. doi: 10.1007/s11302-006-9003-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zimmermann H, Zebisch M, Strater N. Cellular function and molecular structure of ecto-nucleotidases. Purinergic Signal. 2012;8:437–502. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9309-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strater N. Ecto-5′-nucleotidase: structure function relationships. Purinergic Signal. 2006;2:343–350. doi: 10.1007/s11302-006-9000-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buchet R, Millan JL, Magne D. Multisystemic functions of alkaline phosphatases. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1053:27–51. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-562-0_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burnstock G, Vaughn B, Robson SC. Purinergic signalling in the liver in health and disease. Purinergic Signal. 2014;10:51–70. doi: 10.1007/s11302-013-9398-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu L, Hui AY, Albanis E, Arthur MJ, O’Byrne SM, Blaner WS, Mukherjee P, et al. Human hepatic stellate cell lines, LX-1 and LX-2: new tools for analysis of hepatic fibrosis. Gut. 2005;54:142–151. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.042127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schnabl B, Choi YH, Olsen JC, Hagedorn CH, Brenner DA. Immortal activated human hepatic stellate cells generated by ectopic telomerase expression. Lab Invest. 2002;82:323–333. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong F, Tuyama A, Lee TF, Loke J, Agarwal R, Cheng X, Garg A, et al. Hepatic stellate cells express functional CXCR4: role in stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha-mediated stellate cell activation. Hepatology. 2009;49:2055–2067. doi: 10.1002/hep.22890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knuth A, Gabbert H, Dippold W, Klein O, Sachsse W, Bitter-Suermann D, Prellwitz W, et al. Biliary adenocarcinoma. Characterisation of three new human tumor cell lines. J Hepatol. 1985;1:579–596. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(85)80002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knowles BB, Howe CC, Aden DP. Human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines secrete the major plasma proteins and hepatitis B surface antigen. Science. 1980;209:497–499. doi: 10.1126/science.6248960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grubman SA, Perrone RD, Lee DW, Murray SL, Rogers LC, Wolkoff LI, Mulberg AE, et al. Regulation of intracellular pH by immortalized human intrahepatic biliary epithelial cell lines. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:G1060–G1070. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.266.6.G1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakabayashi H, Taketa K, Miyano K, Yamane T, Sato J. Growth of human hepatoma cells lines with differentiated functions in chemically defined medium. Cancer Res. 1982;42:3858–3863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zsembery A, Spirli C, Granato A, LaRusso NF, Okolicsanyi L, Crepaldi G, Strazzabosco M. Purinergic regulation of acid/base transport in human and rat biliary epithelial cell lines. Hepatology. 1998;28:914–920. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roman RM, Feranchak AP, Salter KD, Wang Y, Fitz JG. Endogenous ATP release regulates Cl- secretion in cultured human and rat biliary epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G1391–G1400. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.6.G1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beldi G, Wu Y, Banz Y, Nowak M, Miller L, Enjyoji K, Haschemi A, et al. Natural killer T cell dysfunction in CD39-null mice protects against concanavalin A-induced hepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:841–852. doi: 10.1002/hep.22401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohta A, Sitkovsky M. Role of G-protein-coupled adenosine receptors in downregulation of inflammation and protection from tissue damage. Nature. 2001;414:916–920. doi: 10.1038/414916a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kukulski F, Levesque SA, Sevigny J. Impact of ectoenzymes on p2 and p1 receptor signaling. Adv Pharmacol. 2011;61:263–299. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385526-8.00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Graubardt N, Fahrner R, Trochsler M, Keogh A, Breu K, Furer C, Stroka D, et al. Promotion of liver regeneration by natural killer cells in a murine model is dependent on extracellular adenosine triphosphate phosphohydrolysis. Hepatology. 2013;57:1969–1979. doi: 10.1002/hep.26008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Odashima M, Otaka M, Jin M, Komatsu K, Wada I, Matsuhashi T, Horikawa Y, et al. Selective A2A adenosine agonist ATL-146e attenuates acute lethal liver injury in mice. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:526–529. doi: 10.1007/s00535-005-1609-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oliveira AG, Marques PE, Amaral SS, Quintao JL, Cogliati B, Dagli ML, Rogiers V, et al. Purinergic signalling during sterile liver injury. Liver Int. 2013;33:353–361. doi: 10.1111/liv.12109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hart ML, Much C, Gorzolla IC, Schittenhelm J, Kloor D, Stahl GL, Eltzschig HK. Extracellular adenosine production by ecto-5′-nucleotidase protects during murine hepatic ischemic preconditioning. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1739–1750. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Henderson NC, Arnold TD, Katamura Y, Giacomini MM, Rodriguez JD, McCarty JH, Pellicoro A, et al. Targeting of alphav integrin identifies a core molecular pathway that regulates fibrosis in several organs. Nat Med. 2013;19:1617–1624. doi: 10.1038/nm.3282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mederacke I, Hsu CC, Troeger JS, Huebener P, Mu X, Dapito DH, Pradere JP, et al. Fate tracing reveals hepatic stellate cells as dominant contributors to liver fibrosis independent of its aetiology. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2823. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iwaisako K, Brenner DA, Kisseleva T. What’s new in liver fibrosis? The origin of myofibroblasts in liver fibrosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27(Suppl 2):65–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.07002.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boyer JL. Bile formation and secretion. Compr Physiol. 2013;3:1035–1078. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c120027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schuppan D, Kim YO. Evolving therapies for liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1887–1901. doi: 10.1172/JCI66028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strazzabosco M, Fabris L, Spirli C. Pathophysiology of cholangiopathies. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:S90–S102. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000155549.29643.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tacke F, Weiskirchen R. Update on hepatic stellate cells: pathogenic role in liver fibrosis and novel isolation techniques. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;6:67–80. doi: 10.1586/egh.11.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dranoff JA, Kruglov EA, Toure J, Braun N, Zimmermann H, Jain D, Knowles AF, et al. Ectonucleotidase NTPDase2 is selectively down-regulated in biliary cirrhosis. J Investig Med. 2004;52:475–482. doi: 10.2310/6650.2004.00710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fausther M, Lecka J, Kukulski F, Levesque SA, Pelletier J, Zimmermann H, Dranoff JA, et al. Cloning, purification, and identification of the liver canalicular ecto-ATPase as NTPDase8. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G785–G795. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00293.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fausther M, Sheung N, Saiman Y, Bansal MB, Dranoff JA. Activated hepatic stellate cells upregulate transcription of ecto-5′-nucleotidase/CD73 via specific SP1 and SMAD promoter elements. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G904–G914. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00015.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]