Abstract

Recent developments of tools for targeted genome modification have led to new concepts in how multiple traits can be combined. Targeted genome modification is based on the use of nucleases with tailor-made specificities to introduce a DNA double-strand break (DSB) at specific target loci. A re-engineered meganuclease was designed for specific cleavage of an endogenous target sequence adjacent to a transgenic insect control locus in cotton. The combination of targeted DNA cleavage and homologous recombination–mediated repair made precise targeted insertion of additional trait genes (hppd, epsps) feasible in cotton. Targeted insertion events were recovered at a frequency of about 2% of the independently transformed embryogenic callus lines. We further demonstrated that all trait genes were inherited as a single genetic unit, which will simplify future multiple-trait introgression.

Keywords: cotton, targeted molecular trait stacking, meganuclease, targeted DNA double-strand break induction and repair, homologous recombination, gene targeting

Introduction

Cotton is one of the major GM field crops next to soya bean, corn and canola. The percentage of the global cotton acreage planted with GM cotton has reached 82% in 2012 (James, 2011). Herbicide tolerance and/or insect resistance is the most widely used GM traits in cotton. Different herbicide tolerance and insect resistance genes with different modes of action will be needed to provide for future combined, broad coverage weed and pest control. In addition to herbicide tolerance and insect resistance traits, there are several agronomic and quality traits being developed for multiple-trait introgression in cotton and other crop plants, including disease resistance, abiotic stress tolerance, yield enhancement and quality traits. Combining two or more traits in one variety can be performed either by conventional breeding stacks or by molecular trait stacking in a single transgene locus using a transformation vector carrying multiple-trait genes (Que et al., 2010). With both technologies, the logistical challenges increase with the number of trait genes to be stacked. Either large breeding populations have to be screened to identify those individuals in which all trait genes are retained or large numbers of transformants have to be screened to identify the one expressing all traits as desired. Targeted molecular trait stacking could overcome many of these challenges by targeted insertion of the additional trait genes in close genetic vicinity of an already existing transgene locus.

Targeted genome modifications have been achieved by the introduction of a DNA double-strand break (DSB) at a chosen specific chromosomal location using different types of sequence-specific nucleases. The three major types of sequence-specific designer rare-cutting endonucleases for targeted DSB induction are the zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) (Porteus and Baltimore, 2003), the transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) (Bogdanove and Voytas, 2011) and the meganucleases (Epinat et al., 2003). The ZFNs consist of a synthetic C2H2 DNA-binding zinc finger domain fused to the catalytic domain of the FokI endonuclease (Carroll, 2011). The DNA-binding domain is usually composed of three to five zinc fingers, each recognizing a 3-bp-long sequence. Zinc finger binding depends on more than simply matching triplets of DNA to the corresponding finger. TALENs consist of an engineered DNA-binding domain from transcription activator-like effectors (TALEs) fused to the catalytic domain of FokI (Cermak et al., 2011). Each transcription activator-like effector (TALE) repeat binds a single base pair in the target DNA, thereby simplifying design in comparison with ZFNs. Also, there seem to be fewer context effects with TALE repeats than with zinc fingers (Christian et al., 2010). As dimerization of the FokI domain is required for cleavage, this necessitates the design of a pair of reagents for both ZFNs and TALENs to cleave the desired target sequence.

The LAGLIDADG homing endonucleases, also called meganucleases, are a third class of designer nucleases for targeted DSB induction (Epinat et al., 2003). Meganucleases are more challenging to re-engineer compared with TALENs and ZFNs as the DNA-binding domains of most homing endonucleases are not separated from the catalytic domain (Taylor et al., 2012). These meganucleases typically cleave long recognition sites (20–30 bp), making them highly specific. The I-CreI homing endonuclease of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Thompson et al., 1992) has been used as scaffold for the development of designer meganucleases (Arnould et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2006).

More recently, a new platform for targeted DSB induction in complex genomes based on the CRISPR-associated (Cas) endonuclease has been discovered. Cas9 is guided to its target by a small designer RNA and specifically cleaves target sequences complementary to this small guide RNA (Hwang et al., 2013; Jinek et al., 2012). Cleavage of a new target sequence requires only a new guide RNA but no new enzyme, while for ZFNs and TALENs and meganucleases, a new enzyme has to be generated for each target.

Double-strand breaks in plant cells are predominantly repaired by nonhomologous recombination (NHR), which is often imprecise resulting in the loss of gene function. Precise repair of DSBs is possible through homologous recombination (HR) by the use of a homologous DNA template that is exploited for the creation of precise modifications at a desired target site. Up to now, there are several papers reporting on targeted mutagenesis in plants by nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) using ZFNs as designer nucleases, like in Arabidopsis (Lloyd et al., 2005), tobacco (Maeder et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2013) and soya bean (Curtin et al., 2011). As TALENs have been developed only a few years ago, there are still only a few papers describing studies of TALENs in plants. TALENs have been used for the creation of mutations by NHEJ in Arabidopsis (Cermak et al., 2011), tobacco (Mahfouz et al., 2011) and in rice for the generation of disease-resistant plants by targeted disruption of the rice bacterial blight susceptibility gene (Li et al., 2012). Targeted mutagenesis by NHR at the liguleless1 chromosomal locus in maize using an engineered I-CreI endonuclease has been demonstrated by Gao et al., 2010. There have no studies been published yet on the use of CRISPR/Cas9 for targeted DSB induction and repair in plants.

Most published studies on HR-mediated targeted genome modification mediated by ZFNs use the model plant tobacco (Cai et al., 2009; Townsend et al., 2009; Wright et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2013) or Arabidopsis (De Pater et al., 2013). To date, there is only one plant paper on ZFN- and HR-mediated genome modification in an agronomic crop describing targeted gene addition at an endogenous locus in maize (Shukla et al., 2009). These authors show disruption of the IPK1 locus by HR-mediated targeted insertion of an herbicide tolerance gene resulting in both herbicide tolerance and phytate reduction. HR-mediated gene targeting using TALENs has only been reported for tobacco. In this study, gene targeting was obtained at frequencies that would not further require the need for selection or enrichment procedures (Zhang et al., 2013).

In our study, we assessed whether a customized designed nuclease could be used for trait stacking by HR-mediated gene addition next to a pre-existing, good performing transgene locus in cotton. Using single-chain I-CreI–based engineered homing endonuclease technology, we were able to precisely insert two herbicide tolerance genes in close vicinity to a pre-existing insect control locus.

Results

Design and validation of the endonuclease

To allow transgene stacking in the elite insect control event GHB119 (described in 2008/151780, deposit nr ATCC PTA-8398) comprising the cry2Ae gene and the bar gene, conferring Lepidoptera resistance and glufosinate tolerance, respectively, a customized meganuclease was developed for cleavage in the flanking genomic sequence of the cry2Ae/bar transgene locus. A flanking sequence of about 5.2 kb was screened for the presence of potential useful target sites. Four potential target sites for the development of a meganuclease were identified: COT-1/2, COT-5/6, COT-7/8 and COT-9/10. Southern blot analysis was carried out to test whether these endonucleases did in vitro cleave genomic cotton DNA at the intended recognition sequence. Although Southern blot analysis did show that all four endonucleases cleaved their intended recognition site in vitro, only the COT-5/6 meganuclease cleaved efficiently its intended ‘chromosomal’ target site in planta. To test the meganucleases for their potential to cleave their chromosomal target in planta, we produced stable transformants with each of the four meganucleases and we performed PCRs over the target site. Upon cleavage of its chromosomal target, NHEJ will result in imprecise repair and may result in a shift in size of the PCR amplification product as a result of insertion or deletion of sequences at the target site. With COT-5/6 transformants, we could observe PCR amplification products with a size different from the ones expected for a noncleaved target. In cotton transformations with the other three meganucleases, only incidental cleavage of the chromosomal target was observed with COT-7/8 and no cleavage was observed with COT-1/2 and COT-9/10 based on the size of the PCR amplification product (data not shown). To evaluate whether the absence of cleavage of their chromosomal target was due to an expression problem of the meganuclease, we tested expression by RNA and protein gel blot analysis for stable transformants with the COT-1/2 meganuclease. Full-length COT-1/2 transcript and protein were observed (data not shown). By making a fusion protein between COT-1/2 and GFP, we also showed that the protein was targeted to the nucleus, as intended (data not shown). We therefore hypothesize that target inaccessibility was the reason for absence of cleavage of the COT-1/2 and likewise also for the COT-9/10 meganuclease.

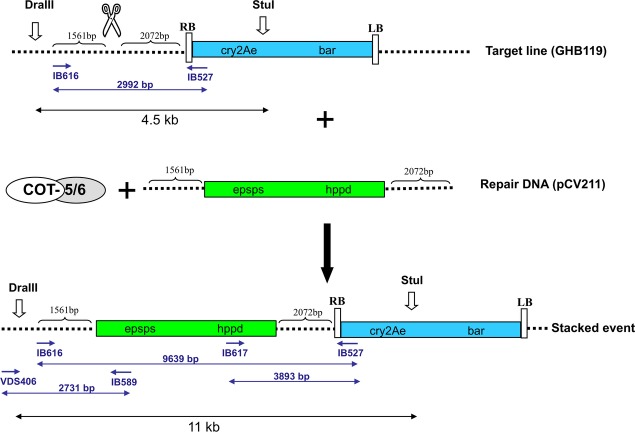

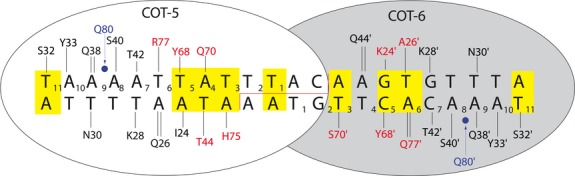

The COT-5/6 meganuclease was designed to recognize and cleave the DNA sequence 5′-TAAAATTATTTACAAGTGTTTA-3′, and the target sequence was found 2072 bp upstream of the cry2Ae/bar transgene locus (Figures1 and 2). To develop the engineered COT-5/6 meganuclease, the DNA-binding characteristics of the natural, homodimeric I-CreI homing endonuclease were modified by the introduction of a number of amino acid substitutions into a pair of engineered monomers (designated as COT-5 and COT-6, Figure1). A single-chain meganuclease, comprising this pair of modified I-CreI monomers, fused into a single polypeptide, was used for the targeted cleavage to allow the insertion of additional genes at the elite insect control locus. The COT-5/6 coding sequence was placed under the control of a 35S promoter, and an SV40 nuclear localization signal (NLS) was fused to the N-terminus of the protein.

Figure 1.

The predicted amino acid contacts between the engineered COT-5 and COT-6 meganuclease monomers and the intended target site in the cotton genome. Amino acids that deviate from I-CreI are shown in red. Bases in the target site that deviate from the wild-type I-CreI target are shown in yellow. Predicted contacts to the DNA backbone are in blue.

Figure 2.

Homologous recombination (HR)-mediated targeted insertion of hppd and epsps at a pre-existing transgene locus (cry2Ae and bar) in the target line GHB119. pCV211 is the repair DNA; a 2072 bp downstream and a 1561 bp upstream of the COT-5/6 cleavage site function as the homologous regions. Stacked events obtained after double-strand break-induced HR between the target GHB119 and the repair DNA pCV211 are expected to have the structure as shown in the bottom part of the figure. The primer pairs IB617 × IB527, VDS406 × IB589 and IB616 × IB527 are generating a fragment of 3893, 2731 and 9639 bp, respectively. With primer pair IB616 × IB527, a PCR fragment should shift from 2992 bp for target GHB119 to 9639 bp for a correct stacked event. Bar, phosphinothricin acetyltransferase; hppd, 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase gene; cry2Ae, insecticidal crystal protein of Bacillus thuringiensis, epsps, 5-enol-pyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase.

Stacking of trait genes by targeted sequence insertion

To allow precise gene addition, a homologous DNA pCV211, designated ‘repair DNA’, was developed. The repair DNA contains two herbicide tolerance genes, epsps and hppd genes, flanked by cotton genomic sequences corresponding to the target locus, being 1561 bp homology upstream and 2072 bp homology downstream of the COT-5/6 cleavage site (Figure2). The coding sequence of the 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase gene (hppd) of Pseudomonas fluorescens (Boudec et al., 2001) was under the control of a 35S promoter. The coding sequence of a double mutant enol-pyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase gene (epsps) of Zea mays (Lebrun et al., 1997) was operably linked to the promoter region of the histone H4 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana Ph4a748 (Chabouté et al., 1987). The epsps gene confers tolerance to the herbicide glyphosate, whereas the hppd gene confers tolerance to the hppd inhibitor herbicides, for example tembotrione. Particle bombardment was used to co-deliver the COT-5/6 meganuclease coding sequence and the repair DNA pCV211 into embryogenic callus (EC) of the hemizygous target line GHB119. To test whether simultaneous expression of the COT-5/6 meganuclease and the delivery of homologous repair DNA may lead to events with precise targeted insertion of the herbicide tolerance genes at the intended target locus, we first selected for EC transformation events on the basis of tolerance to the herbicide glyphosate. Glyphosate-tolerant EC events were subsequently subjected to PCR analysis for the identification of targeted sequence insertion events. The presence of a PCR product of 3893 bp with primer pair IB527 × IB617 or a PCR product of 9640 bp fragment with primer pair IB527 × IB616 and the presence of a PCR product of 2731 bp with primer pair IB589 × VDS406 are indicative for precisely stacked gene insertion by two-sided HR. The presence of only a 3893 bp or a 9640 bp and the absence of a 2731 bp or vice versa are indicative of at least one-sided homologous-mediated insertion.

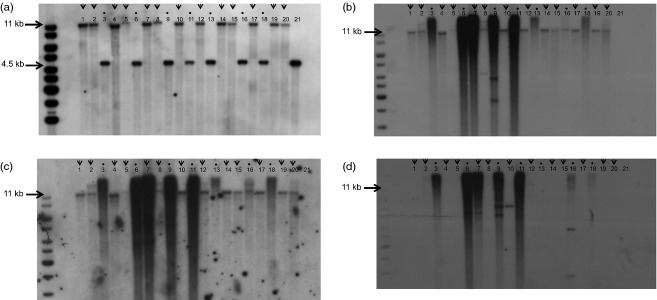

In total, 27 putative correctly stacked EC events have been identified using PCR analysis: targeted sequence insertion events were recovered at a frequency of 1.8% of the 1479 identified glyR events. To further confirm that the PCR-identified stacked events were indeed the result of targeted integration of the epsps and the hppd gene, Southern blot analysis was performed. By hybridization of DraIII-/StuI-digested DNA with the cry2Ae probe, we showed that the 4.5-kb fragment in the target line shifted to an 11-kb fragment in the stacked event (Figure3). This 5.5-kb increase in fragment size is corresponding with the 5.5-kb size of the hppd and epsps genes showing the feasibility of homology-based targeted insertion of the hppd and epsps genes. By hybridization with the hppd and the epsps probes, the same 11-kb fragment was obtained (data not shown). This provides proof of evidence for homology-directed targeted insertion of the hppd and epsps genes in the cotton genome. In Southern blot analysis, we also included some samples from glyphosate-tolerant EC events that did not yield a PCR product with the above-mentioned primers, as the absence of a PCR product could also result from poor DNA quality or large deletions or insertions at the target site. These latter events yielded only a fragment of 4.5 kb upon DNA hybridization of DraIII-/StuI-digested DNA with the cry2Ae probe, showing the absence of targeted insertion of the herbicide resistance genes in these events (Figure3a).

Figure 3.

Southern blot analysis on DraIII-/StuI-digested genomic DNA isolated from embryogenic callus and probed with cry2Ae (a), hppd (b), epsps (c) and the COT-5/6 meganucleases (d) from events selected on glyphosate. Events designated as stacked events based on PCR genotyping are indicated with an arrow. Events designated as nonstacked events based on the absence of a PCR product upon PCR genotyping are indicated with a dot. First lane: molecular mass marker (1 kb+); lanes 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 12, 14, 15, 17, 19 and 20: stacked events; lanes 3, 6, 9, 11, 13, 16 and 18: nonstacked events; lane 21: target line GHB119. The fragments corresponding to a 4.5-kb band for a nonstacked event (after hybridization with the cry2Ae probe) and an 11-kb fragment for a stacked event (after hybridization with the cry2Ae, hppd, and epsps probes) are indicated by arrows to the left.

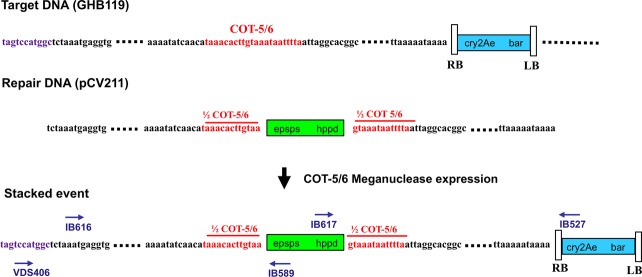

Sequence analysis of a 3893-bp or a 2731-bp fragment, PCR amplified with primer pair IB527 × IB617 or primer pair IB589 × VDS406, respectively, from 18 targeted insertion events, and spanning the two recombination sites, showed perfect insertion of epsps and hppd at the target locus up to the nucleotide (Figure4).

Figure 4.

Sequence analysis at the target locus of a stacked event. The epsps and hppd genes are highlighted in green, the flanking homologous sequences in black, the COT-5/6 recognition sequence in red, the cry2Ae and bar sequence in blue, and the flanking genomic sequence outside the repair DNA in purple. Target DNA (GHB119) and repair DNA (pCV211) sequences are illustrated at the top of the figure. Primers IB617 × IB527, VDS406 × IB589 and IB616 × IB527, used to amplify the fragments for sequence analysis, are indicated both in Figure2 and in Figure4 as on the stacked event at the bottom. In 18 independent stacked events, the hppd and epsps inserts show junctions as for perfect 2-sided homologous recombination events as shown in this figure.

A remarkable large fraction (∼60%–70%) of the stacked events did not contain additional insertions of hppd or epsps or COT-5/6 meganuclease elsewhere in the genome. No bands in addition to the 11-kb fragment were observed after hybridization of DraIII-/StuI-digested DNA with the hppd or epsps probes (Figure3b,c). Also after hybridization with the COT-5/6 meganuclease probe, the majority of the stacked events (80%) did not show insertions of the meganuclease gene (Figure3d). This suggests that most often the meganuclease was only transiently expressed and did not stably integrate into the genome. In contrast to our stacked events, the nonstacked events included in Figure3 (indicated by a dot) did often show an intense ‘smear’ upon hybridization with the hppd, epsps or COT-5/6 meganuclease probe. This presumably results from multiple-copy insertions of the repair DNA and the meganuclease in these nonstacked events, which is typical for particle bombardment–mediated transformation.

Based on all the results, we can conclude that DSB-induced perfect two-sided HR-mediated targeted trait gene addition at a specified target locus, without random additional insertions, is feasible in cotton.

Inheritance of the stack

To verify the inheritance of the four trait genes as a single genetic unit, we attempted to produce seeds. As not all tissue culture–regenerated plants from cotton are fertile, we regenerated multiple plants from each independent stacked EC event to increase the chance of getting seeds.

Plant regeneration was obtained from 15 independent stacked EC events and seven events produced seeds either by self-pollination and/or by pollination with wild-type C312 pollen. Individual progeny were analysed by real-time PCR (Ingham et al., 2001) for copy number determination of the four genes of the stack. Hemizygous and homozygous progeny plants did contain 1 and 2 copies, respectively, of each of the four genes of the gene stack, while null segregants were WT for all four genes. All progeny did show inheritance of the gene stack (cry2Ae, bar, hppd, epsps) in a normal Mendelian manner as a single genetic locus.

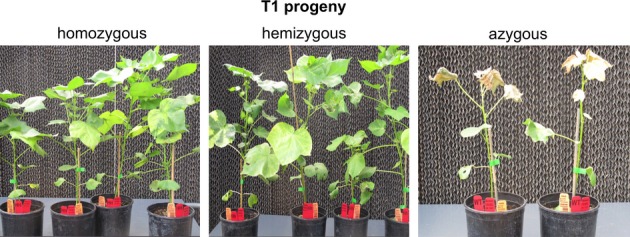

We further evaluated the tolerance to the HPPD inhibitor herbicide tembotrione (TBT) in the greenhouse on T1 and T2 progeny. The plants displayed some mild bleaching after a TBT spray treatment (200 g/ha) but recovered completely and produced plenty of seeds. Null segregants bleached out completely and died off (Figure5). This shows that the hppd gene was expressed. We further showed that the other three genes, epsps, bar and cry2Ae, were expressed, as 2mEPSPS, PAT/bar and CRY2A protein were detected by the EnviroLogix QuickStix™ Strip tests (catalogue number AS 089ST and AS 005LT, EnviroLogix, Portland, ME). From these observations, it can be concluded that the four genes were transmitted to the next generation as a single genetic unit and that all genes of the gene stack were expressed.

Figure 5.

Greenhouse evaluation of segregating T1 progeny of a stacked event sprayed with 200 g/ha tembotrione. Pictures were taken 18 days after the spray treatment. The azygous plants (right) were completely killed 18 days after the herbicide treatment. The transformed plants carrying the four genes (hppd, epsps, cry2Ae and bar) showed some mild bleaching, with sometimes a mosaic pattern, on one or a few leaves. No difference in herbicide tolerance performance was observed between homozygous and hemizygous progeny plants.

Discussion

The number of trait genes to be transformed into an agronomically relevant crop as cotton could easily add up to a number that would become unmanageable to be combined in a single variety through breeding. The breeding effort to introduce different trait loci into a crop will increase exponentially with the number of trait loci. Therefore, it may be important to bring several trait genes into a single genetic locus. This could be done either through molecular trait stacking by transformation with a vector containing multiple-trait genes or through targeted molecular trait stacking by targeted insertion of additional trait genes in an already existing trait locus. In this study, we have shown the feasibility of the targeted introduction, through targeted DSB induction by a customized meganuclease, of additional genes at an already existing transgenic locus in cotton.

Engineering new GM traits in cotton is particularly challenging. There is a strong genotype dependence for regeneration through somatic embryogenesis, with long timelines to produce transformed plants and with fertility problems related to the high level of somaclonal variation (Kumria et al., 2003). In a difficult transformable crop as cotton, the development of a good performing event is a tedious process. As customized nucleases can be designed for targeted DSB induction, in combination with the targeted molecular trait stacking concept shown in this study, this offers the possibility to build on an existing elite event by inserting the additional transgenes in close proximity of the initial transgenes within a genetic distance that would not allow segregation.

Molecular trait stacking through standard transformation with vectors containing only two trait genes already requires the generation of many independent transformants to identify a single-copy transformant with optimal expression of both transgenes. Tandemly arranged genes may influence each other's expression due to transcriptional interference between these genes (Eszterhas et al., 2002). Using transformation vectors carrying even more gene cassettes, the probability of selecting an elite event may decrease as the expression of each gene, and the efficacy of each trait, will become less predictable with the increasing number of transgenes (Dietz-Pfeilstetter, 2010; Halpin, 2005). As an alternative for molecular trait stacking by delivering multiple transgenes simultaneously in one vector, transgenes could now be added consecutively by targeted integration at an already identified existing locus as described in this study. The advantage of this approach is that the integration position can be chosen such that the presence of genomic sequences between 2 transgenes reduces transcriptional interference and allows for more predictable expression.

Still, also for targeted molecular trait stacks, it remains important to evaluate whether stacked trait genes are expressed as expected to give the desired trait efficacy, whether their expression remains stable over generations and whether no gene silencing occurs (Que et al., 2010). It has been shown that cre-lox–mediated site-specific transgene integration into a specific chromosome location can produce alleles that express at a predictable level, as well as alleles that are differentially silenced while the alleles were identical at the DNA sequence level (Day et al., 2000). This variation could not be attributed to a position effect as the site of insertion is the same between different site-specific integration events. Epigenetic modification of the transgene, such as methylation, may be one of the factors triggering variation in expression (Day et al., 2000).

It was remarkable to observe that stacked events, as confirmed by PCR and Southern blot analysis, were two-sided HR events and showed perfect insertion up to the nucleotide of both epsps and hppd. Previously, it has been reported that repair of genomic DSBs in somatic plant cells is frequently initiated by one-sided invasion of a homologous sequence, even with repair DNA being homologous to both ends of the break (Puchta, 1998). Puchta's results showed that one-sided invasion was the main pathway for DSB repair in plant cells using T-DNA as matrix. We used extrachromosomal plasmid DNA as repair matrix and particle bombardment as delivery system, and we cannot exclude that these differences have an impact on the mode of repair. Plasmid DNA enters the plant nucleus as a double-stranded DNA molecule, whereas Agrobacterium transfers a single-stranded, protein-coated T-DNA molecule into the nucleus. Although it has been shown that T-DNA may rapidly turn double-stranded in the plant nucleus (Tinland et al., 1994), the timing by which it becomes double-stranded may have an impact on the outcome of DSB repair. In the end, double-stranded DNA template molecules are required for repair of a DSB by two-sided HR as described by the double-strand break repair (DSBR) model for HR (Szostak et al., 1983). In studies performed with mammalian cells, using double-stranded plasmid DNA with homology to both ends of the DSB, also one-sided HR events were found at a high frequency (Rouet et al., 1994; Smih et al., 1995). This suggests that also the target tissue, through the prevalence of certain repair machinery, may stimulate either one- or two-sided HR-mediated repair of DSBs. In our study, we used EC as target tissue, and it is not known whether DSBs are repaired by HR differently in somatic cells from different target tissues. Our observation of highly frequent, perfect, two-sided HR is of particular interest as this allows the predictable generation of ‘perfect’ recombination events.

Of the four meganucleases used in this study, only one efficiently cleaved its chromosomal target in planta, although Southern blot analysis of cotton genomic DNA incubated with purified meganuclease protein revealed that all four meganucleases cleaved their intended chromosomal target sites efficiently in vitro. This discrepancy between in vitro and in planta results is likely due to target site accessibility. Chromosomal context and epigenetic factors play a major role in the cleavage efficiency of rare-cutting endonucleases and account for strong position effects (Daboussi et al., 2012). The latter authors show a very robust correlation between chromatin accessibility and meganuclease efficacy that may also apply to other types of nucleases such as ZFNs and TALENs.

Again in this study, we made the observation that in the majority of our precise targeting events, no additional random integrations of the hppd and epsps genes were observed. We previously made the same observation in maize upon HR-mediated targeted sequence insertion at a pre-engineered I-SceI site (D'Halluin et al., 2008). This is specifically remarkable for DNA delivery by biolistics, which is usually associated with high copy number integration of fragmented and rearranged DNA sequences (Hansen and Chilton, 1996; Travella et al., 2005). We hypothesize that many of the repair proteins involved in DSB repair may be recruited to the nuclease-induced targeted DSB site, hereby reducing the frequency of random integration.

Tools for directed genome modification at any target position in a genome based on targeted cleavage with designed nucleases are becoming a reality. While earlier methods used random mutagenesis and nontargeted methods for genome engineering, with more recent methods, targeted genome optimization is within reach. The induction of DSBs at natural chromosomal sites of choice by custom-made nucleases will allow targeted genome optimization in all agronomically relevant crops. In addition, this technology will make it possible to more effectively exploit the ever-increasing knowledge from systems biology and genomics for both gene discovery and trait development.

In this study, we show for the first time the feasibility of precise targeted integration of transgenes at an elite locus in cotton. This was possible through the combination of targeted DNA cleavage by nucleases with tailor-made specificities and HR-mediated repair of the DSB by naturally occurring DNA repair mechanisms. Targeted molecular trait stacking will facilitate faster and economical trait introgression.

Experimental procedures

Plasmids

The COT-5/6 meganuclease was developed by Precision BioSciences. To produce the COT-5 and COT-6 monomers, a number of amino acid changes were introduced in I-CreI (Figure1). The two engineered monomers were joined into a single polypeptide using an 38 amino acid linker as described in the study by Gao et al., 2010. To generate plasmid pCV193, the single-chain meganuclease was preceded by an SV40 NLS and cloned between the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV)35S promoter and the 3'nos terminator.

The repair DNA pCV211 was constructed as follows. A fragment of 3671 bp consisting of a 1561-bp flanking genomic DNA sequence upstream of the COT-5/6 cleavage site, a multiple cloning site (HpaI, StuI, AsisI), and a 2072-bp flanking genomic DNA sequence downstream of the COT-5/6 cleavage site was synthesized by Entelechon GmbH (Figure2). The gene cassette P35S2-hppd-3′his linked to a Phis-2mepsps-3′his gene cassette was transferred as a 6628-bp AsisI/HpaI fragment into the multiple cloning site (MCS) of the synthetic fragment, yielding the repair DNA construct pCV211 as schematic presented in Figures2 and 4.

The vector construction of the repair DNA pCV211, and the COT-5/6 meganuclease, including sequence listings, is described in detail in Example 1 of WO2013/026740.

Plasmid DNA preparation

Plasmid DNA was prepared with the GenElute™ Plasmid Maxiprep Kit from Sigma, Saint-Louis, MO. An additional DNA precipitation was performed on the 5 mL eluted DNA with 0.1 volume of 7 m NH4Ac and 2 volumes of 100% ethanol.

The DNA pellet was dissolved in MQH2O after washing the DNA pellet with step with 70% ethanol.

Plant material, transformation, repair DNA delivery and selection of targeted integration events

Embryogenic callus was produced from hypocotyls of 8- to 10-day-old hemizygous seedlings from the elite insect control event GHB119 (described in 2008/151780, deposit nr ATCC PTA-8398). GHB119 is a Coker312 transformant comprising the cry2Ae and the bar genes. Hypocotyl explants were plated on medium 100 for callus induction, which is a slightly modified medium as described by Trolinder and Goodin (1987) [M&S salts (Murashige and Skoog, 1962), 100 mg/L myo-inositol, B5 vitamins (Gamborg et al., 1968), 30 g/L glucose, 0.5 g/L 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulphonic acid (MES), 0.94 g/L MgCl2·6H2O, 2 g/L Gelrite, pH 5.8] and incubated under dim light conditions (5–10 μmol/m2/s). After about 2 months when the wound callus at the cut surface of the hypocotyls started to show fast proliferation, the further subculture for the enrichment and maintenance of EC was performed on medium 100 with 2 g/L active carbon. Induction and maintenance of EC occur under dim light conditions (intensity: 1–7 μmol/m2/s; photoperiod: 16-H light/8-H dark) at 26–28 °C. EC was collected 2–3 weeks after subculture, and ∼0.7 mL packed cell volume was plated uniformly on top of a filter paper (Whatman™ 70 mm diameter, GE Healthcare UK Limited, Little Chalfont, UK) on 100 Q (=100 medium with 0.2 m mannitol and 0.2 m sorbitol) for 4–6 h prior to bombardment. After preplasmolysis on 100Q substrate, the EC was bombarded with plasmid DNAs pCV211and pCV193 (0.5–0.75 pmol of each DNA) using the biolistic PDS-1000/He particle delivery system (Bio-Rad, Bio-Rad Laboratories S.A./N.V., Nazareth Eke, Belgium). The particle bombardment parameters were as follows: diameter gold particles, 0.3-3 μm; target distance, 9 cm; bombardment pressure, 9301.5 k Pa; gap distance, 6.4 mm; and macrocarrier flight distance, 11 mm. Immediately after bombardment, the filters were transferred on medium 100 without glyphosate. After 2–4 days on nonselective substrate under dim light conditions at 26–28 °C, the filters were transferred onto medium 100 with 1 mm glyphosate. After about 2–3 weeks, proliferating calli were selected from the filters and further subcultured as small piles onto selective medium with 1 mm glyphosate. A molecular screen based on PCR analysis for the identification of candidate targeted modification events was performed at the level of transformed EC selected on substrate with 1 mm glyphosate. Plant regeneration was initiated from the targeted modification events by plating EC on medium 104 (=medium 100 + 1 g/L KNO3) with 2 g/L active carbon and 1 mm glyphosate under light conditions (intensity: 40–70 μmol/m2/s; photoperiod: 16-H light/8-H dark) at 26–28 °C. After about 1 month, individual embryos of about 0.5–1 cm were transferred on top of a filter paper on M104 medium with active carbon and 1 mm glyphosate. Further well-germinating embryos were transferred onto nonselective germination medium 702 [Stewarts salts and vitamins (Stewart and Hsu, 1977), sucrose 5 g/L, MgCl2·6H2O 0.71 g/L, Gelrite 1.5 g/L, plant agar 5 g/L, pH 6.8]. After 1–2 months, the further developing embryos were transferred onto medium 700 [Stewarts salts + vitamins, sucrose 20 g/L, MgCl2·6H2O 0.47 g/L, Gelrite 1 g/L, plant agar 2.25 g/L, pH 6.8.].

Nucleic acid procedures

Southern blot analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from cotton callus or leaf tissue using the DNeasy® Plant Mini Kit from Qiagen©, Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany. The DNA was digested, separated by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel, transferred to nylon membranes and hybridized with 32P-radioactive probes following standard procedures (Sambrook and Russell, 2001).

PCR analysis

PCR was performed on 100 ng of genomic DNA extracted from cotton calli using a sbeadex® kit-based DNA extraction method from LGC genomics (LGC Limited, Teddington, UK).

For PCR products generated with primer pairs IB527 × IB617 and IB589 × VDS406, the Expand enzyme mix from Roche was used with the following cycling parameters: 4-min denaturation at 94 °C followed by five cycles of 1 min at 94 °C, 1 min at 57 °C, 4 min at 68 °C, followed by 25 cycles of 15 s at 94 °C, 45 s at 60 °C and 4 min at 68 °C (extended with 5 s per cycle) and a final elongation step of 10 min at 68 °C in a 50 μL mixture. For PCR products generated with primer pair IB527 × IB616, the Elongase Enzyme Mix from Invitrogen (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) was used in a final MgSO4 concentration of 2 mm with the following cycling parameters: 2 min at 94 °C followed by 35 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 58 °C and 9 min at 68 °C and a final elongation step of 7 min at 68 °C.

IB527: TCCAGTACTAAAATCCAGATCATGC

IB616: TGATGCGATGAATAACGTAGTG

IB617: CCCTGGCTTGCAGTTGGTCC

IB589: CGACAGCCATCAGAGACGTG

VDS406: TATAAATGCCGGCGCGTAGC

Sequence analysis

Sequence analysis was performed on a 9640-bp, a 3893-bp and a 2371-bp fragments generated with primer pairs IB527 × IB616, IB527 × IB617 and IB589 × VDS406, respectively. The 9640-bp fragment is covering the inserted hppd and epsps cassettes, and 1561-bp and 2072-bp genomic flanking sequence upstream and downstream of the COT-5/6 cleavage site, respectively, and 50 bp of the 3′end of the cry2Ae transgene locus in the GHB119 target line. The 3893-bp and the 2371-bp fragments are covering the recombination sites downstream and upstream of the COT-5/6 target site, respectively (Figure2).

Acknowledgments

Kristine Reynaert, Guillermo Aguacil Ruiz, Christoph Van Hese, Wendy Walraet and Stefanie Van Laere are kindly acknowledged for follow up of the plant material in the greenhouse. We acknowledge Jeff Smith and Michael Nicholson (Precision BioSciences) for their contribution to the development of the COT meganucleases. We are grateful to Geert Hesters for excellent tissue culture support. We thank Veerle Habex for providing the target flanking genomic sequences.

References

- Arnould S, Perez C, Cabaniols J-P, Smith J, Gouble A, Grizot S, Epinat J-C, Duclert A, Duchateau P, Pâques F. Engineered I-CreI derivatives cleaving sequences from the human XPC gene can induce highly efficient gene correction in mammalian cells. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;371:49–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanove A, Voytas D. TAL effectors: customizable proteins for DNA targeting. Science. 2011;333:1843–1846. doi: 10.1126/science.1204094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudec P, Rodgers M, Dumas F, Sailland A, Bourdon H. Mutated hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase, DNA sequence and isolation of plants which contain such a gene and which are tolerant to herbicides. US Patent US6245968B1, France; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cai C, Doyon Y, Ainley W, Miller J, Dekelver R, Moehle E, Rock J, Lee Y, Garrison R, Schulenberg L, Blue R, Worden A, Baker L, Faraji F, Zhang L, Holmes M, Rebar E, Collingwood T, Rubin-Wilson B, Gregory P. Targeted transgene integration in plant cells using designed zinc finger nucleases. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009;69:699–709. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9449-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll D. Genome engineering with zinc-finger nucleases. Genetics. 2011;188:773–782. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.131433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cermak T, Doyle E, Christian M, Wang L, Zhang Y, Schmidt C, Baller J, Somia N, Bogdanove A, Voytas D. Efficient design and assembly of custom TALEN and other TAL effector-based constructs for DNA targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:e82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabouté N, Chaubet N, Philipps G, Ehling M, Gigot Genomic organization and nucleotide sequences of two histone H3 and two histone H3 genes of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 1987;8:179–191. doi: 10.1007/BF00025329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian M, Cermak T, Doyle E, Schmidt C, Zhang F, Hummel A, Bogdanove A, Voytas D. Targeting DNA double-strand breaks with TAL effector nucleases. Genetics. 2010;186:757–761. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.120717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin S, Zhang F, Sander J, Haun W, Starker C, Baltes N, Reyon D, Dahlborg E, Goodwin M, Coffman A, Dobbs D, Joung K, Voytas D, Stupar M. Targeted mutagenesis of duplicated genes in soybean with zinc-finger nucleases. Plant Physiol. 2011;156:466–473. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.172981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daboussi F, Zaslavskiy M, Poirot L, Loperfido M, Gouble A, Guyot V, Leduc S, Galetto R, Grizot S, Oficjalska D, Perez C, Delacôte F, Dupuy A, Chion-Sotinel I, Le Clerre D, Lebuhotel C, Danos O, Lemaire F, Oussedik K, Cédrone F, Epinat J, Smith J, Yanez-Munoz R, Dickson G, Popplewell L, Koo T, VandenDriessche T, Chuah M, Duclert A, Duchateau P, Pâques F. Chromosomal context and epigenetic mechanisms control the efficacy of genome editing by rare-cutting designer endonucleases. Nucleic Acid Res. 2012;40:6367–6379. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day C, Lee E, Kobayashi J, Holappa L, Albert A, Ow D. Transgene integration into the same chromosome location can produce alleles that express at a predictable level, or alleles that are differentially silenced. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2869–2880. doi: 10.1101/gad.849600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pater S, Pinas J, Hooykaas P, van der Zaal B. ZFN-mediated gene targeting of the Arabidopsis protoporphyrinogen oxidase through Agrobacterium-mediated floral dip transformation. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2013;11:510–515. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Halluin K, Vanderstraeten C, Stals E, Cornelissen M, Ruiter R. Homologous recombination: a basis for targeted genome optimization in crop species such as maize. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2008;6:93–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2007.00305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz-Pfeilstetter A. Stability of transgene expression as a challenge for genetic engineering. Plant Sci. 2010;179:164–167. [Google Scholar]

- Epinat J-C, Arnould S, Chames P, Rochaix P, Desfontaines D, Puzin C, Patin A, Zanghellini A, Pâques F, Lacroix E. A novel engineered meganuclease induces homologous recombination in yeast and mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2952–2962. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eszterhas S, Bouhassira E, Martin D, Fiering S. Transcriptional interference by independently regulated genes occurs in any relative arrangement of the genes and is influenced by chromosomal integration position. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:469–470. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.2.469-479.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamborg O, Miller R, Ojima K. Nutrient requirements of suspension cultures of soybean root cells. Exp. Cell. Res. 1968;50:151–158. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(68)90403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Smith J, Yang M, Jones S, Djukanovic V, Nicholson M, West A, Bidney D, Falco C, Jantz D, Lyznik A. Heritable targeted mutagenesis in maize using a designed endonuclease. Plant J. 2010;61:176–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpin C. Gene stacking in transgenic plants-the challenge for 21st plant biotechnology. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2005;3:141–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2004.00113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen G, Chilton M-D. Agrolistic transformation of plant cells: integration of T-strands generated in planta. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:14978–14983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang W, Fu Y, Reyon D, Maeder M, Tsai S, Sander J, Peterson R, Yeh JR, Young K. Efficient genome editing in zebrafish using a CRISPR-Cas system. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:227–229. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingham DJ, Beer S, Money S, Hansen G. Quantitative real-time PCR assay for determining transgene copy number in transformed plants. Biotechniques. 2001;31:132–140. doi: 10.2144/01311rr04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James C. ISAAA report on global status of biotech/GM crops. 2011.

- Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna J, Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumria R, Leelavathi S, Bhatnagar R, Reddy V. Regeneration and genetic transformation of cotton: present status and future perspectives. Plant Tissue Cult. 2003;13:211–225. [Google Scholar]

- Lebrun M, Sailland A. Freyssinet G, Degryse E. Mutated 5-enol-pyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase, gene coding for said protein and transformed plants containing said gene. 1997.

- Li T, Liu B, Spalding M, Weeks D, Yang B. High-efficiency TALEN-based gene editing produces disease resistant rice. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30:390–392. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd A, Plaisier C, Carroll D, Drews G. Targeted mutagenesis using zinc-finger nucleases in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:2232–2237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409339102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeder M, Thibodeau-Beganny S, Osiak A, Wright D, Anthony R, Eichtinger M, Jiang T, Foley J, Winfrey R, Townsend J, Unger-Wallace E, Sander J, Müller-Lerch F, Fu F, Pearlberg J, Göbel C, Dassie J, Pruett-Miller S, Porteus M, Sgroi D, Iafrate A, Dobbs D, McCray P, Cathomen T, Voytas D, Joung J. Rapid ‘open-source’ engineering of customized zinc-finger nucleases for highly efficient gene modification. Mol. Cell. 2008;31:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahfouz M, Li L, Shamimuzzaman M, Wibowo A, Fang X, Zhu J. De novo-engineered transcription activator-like effector (TALE) hybrid nuclease with novel DNA binding specificity creates double-strand breaks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;93:5055–5060. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019533108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue culture. Physiol. Plant. 1962;15:473–497. [Google Scholar]

- Porteus M, Baltimore D. Chimeric nucleases stimulate gene targeting in human cells. Science. 2003;300:763. doi: 10.1126/science.1078395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puchta H. Repair of double-strand breaks in somatic plant cells by one-sided invasion of homologous sequences. Plant J. 1998;13:331–339. [Google Scholar]

- Que Q, Chilton M-D, de Fontes C, He C, Nuccio M, Zhu T, Wu Y, Chen J, Shi L. Trait stacking in transgenic crops: challenges and opportunities. GM Crops. 2010;1:1–10. doi: 10.4161/gmcr.1.4.13439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouet P, Smih F, Jasin M. Introduction of double-strand breaks into the genome of mouse cells by expression of a rare-cutting endonuclease. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;23:5012–5019. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Russell D. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla V, Doyon Y, Miller J, DeKelver R, Moehle E, Worden S, Mitchell J, Arnold N, Gopalan S, Meng X, Choi V, Rock J, Wu Y-Y, Katibah G, Zhifang G, McCaskill D, Simpson M, Blakeslee B, Greenwalt S, Butler H, Hinkley S, Zhang L, Rebar E, Gregory P, Urnov D. Precise genome modification in the crop species Zea mays using zinc-finger nucleases. Nature. 2009;459:437–441. doi: 10.1038/nature07992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smih F, Rouet P, Romanienko PJ, Jasin M. Double-strand breaks at the target locus stimulate gene targeting in embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;14:8096–8106. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.24.5012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Grizot S, Arnould S, Duclert A, Epinat J-C, Chames P, Prieto J, Redondo P, Blanco F, Bravo J, Montoya G, Pâques F, Duchateau P. A combinatorial approach to create artificial homing endonucleases cleaving chosen sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:e149. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl720. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J, Hsu C. In ovulo embryog culture and seedling development of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) Planta. 1977;137:113–117. doi: 10.1007/BF00387547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szostak JW, Orr-Weaver TL, Rothstein RJ, Stahl FW. The double-strand break repair model of recombination. Cell. 1983;33:25–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90331-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor G, Petrucci L, Lambert A, Baxter S, Jarjour J, Stoddard B. LAHEDES: the LAGLIDADG homing endonuclease database and engineering server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W110–W116. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson A, Yuan X, Kudlicki W, Herrin D. Cleavage and recognition pattern of a double-strand-specific endonuclease (I-CreI) encoded by the chloroplast 23S rRNA intron of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Gene. 1992;119:247–251. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90278-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinland B, Hohn B, Puchta H. Agrobacterium tumefaciens transfers single-stranded transfer DNA (T-DANN) into the plant cell nucleus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:8000–8004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend J, Wright D, Winfrey R, Fu F, Maeder M, Joung J, Voytas D. High-frequency modification of plant genes using engineered zinc-finger nucleases. Nature. 2009;459:442–445. doi: 10.1038/nature07845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travella S, Ross M, Harden J, Everett C, Snape J, Harwoord W. A comparison of transgenic barley lines produced by particle bombardment and Agrobacterium-mediated techniques. Plant Cell Rep. 2005;23:780–789. doi: 10.1007/s00299-004-0892-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trolinder L, Goodin J. Somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration in cotton (Gossypium hirsute L.) Plant Cell Rep. 1987;6:231–234. doi: 10.1007/BF00268487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright D, Townsend J, Winfrey R, Irwin P, Rajagopal J, Lonosky P, Hall B, Jondle M, Voytas D. High-frequency homologous recombination in plants mediated by zinc-finger nucleases. Plant J. 2005;44:693–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zhang F, Li X, Baller J, Qi Y, Starker C, Bogdanove A, Voytas D. TALENs enable efficient plant genome engineering. Plant Physiol. 2013;161:20–27. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.205179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]