Abstract

Hypothesis

The advent of LDCT for lung cancer screening will likely lead to an increase in the detection of stage I lung cancer. Presently, these patients are primarily treated with surgery alone and ~ 30% will develop recurrence and die. Biomarkers that can identify patients for whom adjuvant chemotherapy would be a benefit could significantly reduce both patient morbidity and mortality. Herein, we sought to build a prognostic inflammatory-based classifier for stage I lung cancer.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of 548 European American lung cancer cases prospectively enrolled in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) study. CRP, IL-6, IL-8, TNFα and IL-1β were measured using an ultrasensitive electrochemiluminescence immunoassay in serum samples collected at the time of study entry.

Results

IL-6 and IL-8 were each associated with significantly shorter survival (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.08–1.64, P=0.007) (HR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.09–1.67, P=0.005), respectively). Moreover, a combined classifier of IL-6 and IL-8 were significantly associated with poor outcome in stage I lung cancer patients (HR, 3.39; 95% C.I. 1.54 – 7.48, P=0.002) and in stage 1 patients with ≥30 pack-years of smoking (HR, 3.15; 95% C.I. 1.54 – 6.46, P=0.002).

Conclusions

These results further support the association between inflammatory markers and lung cancer outcome and suggest that a combined serum IL-6/IL-8 classifier could be a useful tool for guiding therapeutic decisions in stage I lung cancer patients.

Introduction

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality in the United States 1. For all stages of lung cancer combined, the five-year survival rates are still less than 17%. However, patients diagnosed with stage IA disease and who undergo surgery have a 5-year survival rate of approximately 75%, this rate decreases to 71% for stage IB patients and further declines with increasing stage 1, 2. Although surgery remains the standard of care for stage I lung cancer patients, between 20% and 30% of patients with histologically negative lymph nodes at the time of surgery will experience a recurrence 3 and the prospective identification of these patients remains a challenge. Biomarkers that can identify patients for whom adjuvant chemotherapy would be a benefit could significantly reduce both patient morbidity and mortality. Results from the National Lung Screening Trial indicate that annual screens with low dose helical CT (LCDT) can reduce the mortality associated with lung cancer by 20% 4, especially those at higher risk 5. The study prompted the US Preventative Services Task Force to recommend low-dose CT screening for all individuals aged between 55 and 80 with a smoking history of ≥30 pack-years 6. The immense sensitivity of this imaging tool has led to increased detection of stage I lung cancers, thus enhancing the need for biomarker-guided approaches to the treatment of stage I lung cancer and the prospective identification of patients at risk of tumor recurrence. Moreover, a recent study estimates the rate of over-diagnosis in the NLST at 18.5% 7; biomarkers that can be combined with an imaging screening program could offer improved prospective identification of aggressive and indolent tumors, and thus informed treatment of patients with LDCT-detected lung cancer.

We 8 and others 9–12 have shown an association between a systemic inflammatory response and a higher risk of lung cancer mortality 9–11, 13–15. In addition, chronic inflammatory states 16 including COPD 17, 18 and asbestosis 19 are associated with a higher risk of lung cancer mortality. Inflammatory cells may participate in lung carcinogenesis by generating reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, by secreting growth stimulatory cytokines, and by contributing to the formation of DNA adducts 20. Identifying biomarkers that quantify such signals and prospectively inform cancer prognosis, especially for stage I lung cancer patients, could prove extremely useful in the management of lung cancer. However, few studies have examined the association between chronic inflammation and lung cancer survival in stage I patients.

Materials and Methods

Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer (PLCO) Screening Trial Study

Participants within the screening arm of the PLCO Cancer Screening Trial were selected for this nested case–control study as described previously 21. The PLCO screening trial was a randomized trial designed to evaluate the efficacy of cancer screening in reducing cancer mortality. It recruited 155,000 men and women aged 55–74 years from 1992 to 2001, from 10 centers throughout the United States 22. Participants in the screening group provided blood samples annually for 6 years, but baseline blood samples were used in this study. At the time of the December 31, 2004 sample selection cut-off date, 898 lung cancers had been diagnosed among the 77,464 participants in the screening group. Patients were excluded if they had a missing consent for utilization of biological specimens for etiologic studies, missing baseline questionnaire, diagnosis of multiple cancers during the study, missing smoking information at baseline, or unavailability of serum specimens. Patients for whom lung cancer was not the primary diagnosis were removed from the analysis as it was thought that other cancer types could confound the association – for example, if cytokines were high, it could be because they later developed a different cancer that is preceded by elevated levels. This point is relevant given our previous work showing that serum levels of a biomarker can be elevated many years before a cancer diagnosis 21. Five hundred forty-eight serum samples from European American and 44 serum samples from African American lung cancer patients were available. This proportion was comparable to the enrollment of African Americans in the full PLCO trial (6%) 23. The characteristics of the European American cases included in this study are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of characteristics among the PLCO lung cancer cases included in our study

| Characteristic | N | % | IL-6 Stage I only Median (IQR) |

IL-8 Stage I only Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 548 | 100 | 164 | 164 |

| Age in years, mean ± SD (range) | 65 ± 5 (55 – 74) | |||

| Race | ||||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 548 | 100 | 4.1 (2.7 – 7.3) | 19.05 (13.9 – 24.1) |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | ||||

| Hispanic | ||||

| Asian | ||||

| Pacific Islander/American Indian | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 370 | 67.5 | 4.6 (2.7 – 8.2) | 19.0 (14.2 – 24.0) |

| Female | 178 | 32.5 | 3.8 (2.8 – 5.7) | 19.1 (13.3 – 24.2) |

| Smoking Status | ||||

| Never | 38 | 6.9 | 3,9 (2.8 – 4.8) | 15.2 (11.5 – 20.5) |

| Former | 214 | 39.1 | 4.3 (2.6 – 8.0) | 19.2 (15.0 – 24.2) |

| Current | 296 | 54.0 | 4.1 (2.8 – 7.8) | 18.6 (12.1 – 24.0) |

| Pack-years, mean SD (range) | 56.6 ± 35.9 (0 – 230) | |||

| Family History of Cancer | ||||

| No | 419 | 18.8 | 4.3 (2.7 – 7.2) | 19.1 (13.8 – 24.2) |

| Yes | 97 | 81.2 | 3.3 (2.7 – 5.7) | 19.3 (15 – 23.2) |

| Missing | 32 | |||

| Stage | ||||

| Ia | 104 | 22.9 | ||

| Ib | 60 | 13.2 | ||

| II | 36 | 7.9 | ||

| III | 73 | 16.1 | ||

| IV | 171 | 39.9 | ||

| Missing | 94 | |||

| Histology | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 175 | 22.9 | 3.85 (2.4 – 6.3) | 18.0 (13.8 – 23.2) |

| Squamous Cell Carcinoma | 121 | 22.1 | 5.7 (3.3 – 8.4) | 21.5 (17 – 24.2) |

| Small Cell Carcinoma | 70 | 12.8 | NA | NA |

| Bronchioalveolar Adenocarcinoma | 48 | 8.8 | 3.1 (2.6 – 4.4) | 15.9 (11.7 – 22.7) |

| Large Cell Carcinoma | 33 | 6.0 | 6.6 (2.9 – 6.7) | 17.7 (9.4 – 29.3) |

| Other | 96 | 17.5 | 3.5 (2.8 – 7.0) | 19.1 (12.1 – 24.2) |

| Missing | 5 | |||

| IL-6 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 4.4 (2.9 – 7.2 pg/ml) | |||

| IL-8 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 18.9 (14.0 – 24.8 pg/ml) | |||

| TNF-α | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 9.5 (7.6 – 12.3 pg/ml) | |||

| IL-1β | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 0.8 (0.5 – 1.4 pg/ml) | |||

| CRP | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 3.5 (1.5 – 7.9 pg/ml) | |||

| Arthrithis | ||||

| No | 321 | 58.0 | 3.7 (2.6 – 6.6) | 19.2 (14.2 – 24.2) |

| Yes | 228 | 42.0 | 4.8 (3.0 – 8.1) | 19.1 (11.8 – 24.7) |

| Emphysema | ||||

| No | 486 | 88.0 | 3.9 (2.7 – 7.0)* | 18.6 (13.8 – 24.2) |

| Yes | 65 | 12.0 | 7.1 (4 – 10.25) | 21.7 (17.6 – 21.1) |

| Chronic Bronchitis | ||||

| No | 489 | 89.0 | 3.75 (2.7 – 7.0)* | 18.6 (13.8 – 23.5) |

| Yes | 62 | 11.0 | 7.2 (4.4 – 9.1) | 22.1 (19.1 – 25.3) |

| Diabetes | ||||

| No | 502 | 91 | 3.8 (2.7 – 7.2) | 19.2 (14.0 – 24.2) |

| Yes | 48 | 9 | 4.7 (4.3 – 5.7) | 15.8 (14.0 – 20.4) |

| Body Mass Index at Baseline | ||||

| <18.5 kg/m2 | 5 | 1.0 | 7.2 (7.2 - 7.2) | 24.2 (24.2 - 24.2) |

| ≤ 18.5 – 25 kg/m2 | 198 | 36.0 | 3.6 (2.6 – 7.8) | 21.5 (15.5 – 25.4) |

| ≤ 25 – 30 kg/m2 | 146 | 45.0 | 4.1 (2.7 – 7.0) | 17.4 (13.3 – 21.9( |

| > 30 kg/m2 | 98 | 18.0 | 4.7 (3.0 – 8.2) | 18.6 (12.1 – 21.2) |

| Survival in years mean ± SD (range) | 3.1 ± 3.6 (0 – 12.8) | |||

IQR denotes inter-quartile range

P<0.05

Death from lung cancer was initially determined through a questionnaire that was distributed annually by mail and linkage to the National Death Index. Subsequently, a death review panel confirmed the cause of death in a uniform unbiased manner. Further details outlining this process are described 24. TNM stage was initially determined using the 5th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer’s Cancer Staging Manual. Stage was subsequently re-classified using the TNM criteria, 7th edition 25. Death certificates were obtained to confirm death and to determine cause of death. Lung cancer-specific death was defined as one with an underlying cause of lung cancer or treatment for lung cancer.

Measurement of inflammatory markers

Serum cytokines were determined in a previous study 21. Data on prognosis were not assessed at the time of this study as survival data for participants in the lung screening portion of PLCO had not yet been analyzed and the data were not available. Since then, it has been shown that annual screening with chest radiograph does not reduce lung cancer mortality compared with usual care 26. Briefly, sera from T0 (or the earliest time point available) were retrospectively tested for circulating levels of CRP, IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β and TNF-α. IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β and TNF-α levels were measured using an ultrasensitive 4-Plex kit. CRP was measured as reported earlier 27. Briefly, 10 μL of serum were measured for CRP using the Immulite 1000 High Sensitivity CRP chemiluminescent immunometric assay and instrumentation (Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, Los Angeles, CA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples were blinded and randomly distributed. All samples were assayed in duplicate; results shown are based on the average of those duplicates. Controls and standard curves were included with each plate and as an added quality control, 12% of the samples from all three studies were blindly duplicated and evenly distributed both inter-plate and intra-plate. The inter-plate correlations for IL-6 and IL-8 were 0.78 and 0.76, respectively. Intra-plate correlations for IL-6 and IL-8 were 0.84 and 0.92, respectively 21. Samples with values lower than the detection limit were assigned a value of one-half of the detection limit. The detection limit for each plate was determined based on linearity of the standard curve following the manufacturer’s instructions. As reported previously, the average limit of detection for IL-6 was 0.11 pg/mL and 0.10 pg/mL for IL-8 in this study 21. For both IL-6 and IL-8, there were no samples that fell below this detection limit. The limit of detection for CRP was 0.2 μg/mL, samples below this detection limit were assigned a level of 0.2 μg/mL. For this study, there were no samples that fell below this detection limit. Quartiles (25%, 50%, 75%) were based on serum IL-6 and IL-8 cut-off levels among European American controls in our previous study (IL-6, 1.4, 2.1, 3.8 pg/mL; IL-8, 7.0, 10.8, 28.5 pg/mL) 21. Median and quartile levels of IL-1β, CRP and TNF-α are outlined in Table 1. These cut-off values were also determined based on the European American controls of our previous study.

Statistical analysis

To test the magnitude of association between inflammatory markers with lung cancer-specific survival, hazard ratios (HR) were estimated using multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression modeling 28 with adjustment for potential confounders, including age (continuous), sex (male/female), current smoking status (never/former/current), stage (stage I/stage II/stage III/stage IV), histology (adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, other) and pack-years of smoking. The 44 African American samples were removed from our analysis as numbers were too small for a stratified analysis. Time from lung cancer diagnosis was used to estimate the survival timescale and failure was described as lung cancer-specific death. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 12.0. Proportional hazards assumptions were verified by visual inspection of log-log plots and using a non-zero slope test of the Schoenfeld residuals 29 (P=0.754 for all stages, P=0.257 stage I, and P=0.525 stage I & ≥ 30 pack-years of smoking). Our results were analyzed and presented according to the REMARK guidelines 30, 31. In this study, causes of death other than lung cancer were censored. There were 29 people (5.3%) whose cause of death was not lung cancer. Of these, 19 (11.2%) were in the stage I category. As competing risks are distinct from standard censoring, we performed a competing risks regression based on the method of Fine and Gray 32 using the stcrreg function in STATA. A new variable was generated to specify the competing events (death from cancer and death from another cause).

Results

Increased serum levels of IL-6 and IL-8 are associated with a higher risk of lung cancer mortality

The lung cancer case participants in this study had a median survival time from diagnosis of 1.3 years. For stage I patients, the median survival time increased to 6.1 years. Increasing levels of IL-1β (HR 1.09, 95% C.I. 0.98 – 1.21, Ptrend=0.119), CRP (HR 1.06, 95% C.I. 0.95 – 1.18, Ptrend=0.231) and TNF-α (HR 1.09, 95% C.I. 0.99 – 1.19, Ptrend=0.077) were not associated with risk of lung cancer mortality (Supplementary Table 1). Increased IL-6 levels, categorized based on the median or quartiles, were associated with a higher risk of mortality (HR ≥ median vs. < median 1.33, 95% C.I. 1.08 – 1.64, P=0.007) (Supplementary Table 1) (Table 2). In addition, high levels of IL-8, categorized as above the 75th percentile, were also associated with higher risk of death (HR ≥75th percentile vs. < 75th percentile 1.43, 95% C.I. 1.13 – 1.80, P=0.002). As certain health conditions associated with systemic inflammation were recorded as part of the questionnaires in PLCO, we also adjusted our analyses for chronic bronchitis (no/yes), emphysema (no/yes), arthritis (no/yes), body mass index at baseline (0–18.5/18.5–25/25–30/30+), and diabetes (no/yes). Controlling for these potential confounders did not change the magnitude of the association between IL-6 (HR ≥ median vs. < median 1.32, 95% C.I. 1.05 – 1.66, P=0.017) or IL-8 (HR ≥75th percentile vs. < 75th percentile 1.39, 95% C.I. 1.10 – 1.76, P=0.006) with lung cancer survival. In addition, there was no significant difference in IL-6 or IL-8 levels among patients with and without these conditions, with 2 exceptions; IL-6 levels were higher in patients with both emphysema and chronic bronchitis (Table 1).

Table 2.

Circulating serum IL-6 and IL-8 associated with risk of lung cancer mortality in PLCO (EA only)

| N | Univariable | Multivariable* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% C.I. | P | HR | 95% C.I. | P | ||

| IL-6 | |||||||

| 1st Quartile | 97 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| 2nd Quartile | 136 | 1.39 | 1.03 – 1.88 | 0.034 | 1.30 | 0.93 – 1.81 | 0.129 |

| 3rd Quartile | 147 | 1.53 | 1.14 – 2.06 | 0.004 | 1.48 | 1.07 – 2.06 | 0.019 |

| 4th Quartile | 168 | 1.73 | 1.30 – 2.31 | <0.0001 | 1.64 | 1.19 – 2.25 | 0.002 |

| P trend | 1.18 | 1.08 – 1.25 | <0.0001 | 1.16 | 1.06 – 1.28 | 0.002 | |

| ≤Median | 243 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| > Median | 305 | 1.28 | 1.07 – 1.55 | 0.008 | 1.33 | 1.08 – 1.64 | 0.007 |

| 1.28 | 1.03 – 1.58 | 0.023^ | |||||

| IL-8 | |||||||

| 1st Quartile | 111 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| 2nd Quartile | 122 | 1.00 | 0.74 – 1.36 | 0.993 | 1.12 | 0.78 – 1.58 | 0.539 |

| 3rd Quartile | 147 | 0.97 | 0.72 – 1.30 | 0.832 | 0.94 | 0.69 – 1.32 | 0.724 |

| 4th Quartile | 168 | 1.19 | 0.90 – 1.58 | 0.223 | 1.37 | 0.99 – 1.89 | 0.057 |

| P trend | 1.06 | 0.97 – 1.16) | 0.221 | 1.09 | 0.99 – 1.21 | 0.093 | |

| ≤ 75th Percentile | 375 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| > 75th Percentile | 173 | 1.23 | 1.00 – 1.52 | 0.047 | 1.43 | 1.13 – 1.80 | 0.002 |

| 1.38 | 1.10 – 1.74 | 0.006# | |||||

Adjusted for age, gender, stage, histology, smoking status

Adjusted for age, gender, stage, histology, smoking status, IL-8

Adjusted for age, gender, stage, histology, smoking status, IL-6

Quartiles (25%, 50%, 75%) were based on serum IL-6 and IL-8 cut-off levels among controls in NCI-MD study (IL-6, 1.4, 2.1, 3.8 pg/mL; IL-8 7.0, 10.8 and 28.5 pg/mL).

Serum IL-6 and IL-8 levels were dichotomized into ≤ the median vs > the median among controls in the NCI-MD study (IL-6, 2.1 pg/mL; IL-8 10.8 pg/mL).

EA denotes European American

Association of circulating IL-6 and IL-8 with outcome of stage I lung cancer

Results from the NLST show that annual screens of high-risk individuals with LDCT reduces lung cancer mortality and diagnoses a predominance of early-stage lung cancer, particularly stage 1A 4, 5. Thus, given the need for robust prognostic biomarkers for stage I lung cancer, we conducted a sub-group analysis and restricted our cases to those diagnosed with stage I disease (36% of patients in our study). We observed that increased levels of both IL-6 and IL-8 were associated with an increased risk of mortality in this group (Table 3); IL-6 (HR ≥ median vs. < median 2.19, 95% C.I. 1.23 – 3.81, P=0.006) (Table 3) and IL-8 (HR ≥75th percentile vs < 75th percentile 1.85, 95% C.I. 1.12 – 3.04, P=0.016). Additional controlling for inflammatory health conditions did not significantly alter the magnitude of the association between IL-6 (HR ≥ median vs. < median 2.05, 95% C.I. 1.13 – 3.72, P=0.018) and IL-8 (HR ≥75th percentile vs < 75th percentile 1.83, 95% C.I. 1.05 – 3.21, P=0.034) with lung cancer survival. Levels of TNFα, IL-1β or CRP were not associated with outcome of stage I lung cancer (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 3.

Circulating serum IL-6 and IL-8 associated with risk of lung cancer mortality in Stage I diagnosed lung cancer (EA only)

| Univariable | Multivariable* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% C.I. | P | HR | 95% C.I. | P | |

| IL-6 | ||||||

| 1st Quartile | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| 2nd Quartile | 0.99 | 0.38 – 2.56 | 0.981 | 1.06 | 0.41 – 2.75 | 0.908 |

| 3rd Quartile | 1.93 | 0.84 – 4.44 | 0.122 | 1.98 | 0.85 – 4.60 | 0.111 |

| 4th Quartile | 3.18 | 1.46 – 4.44 | 0.004 | 2.88 | 1.31 – 6.35 | 0.009 |

| P trend | 1.57 | 1.23 – 2.00 | <0.0001 | 1.47 | 1.16 – 1.89 | 0.002 |

| ≤ Median | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| > Median | 2.41 | 1.40 – 4.14 | 0.002 | 2.19 | 1.23 – 3.81 | 0.006 |

| 2.02 | 1.16 – 3.54 | 0.014^ | ||||

| IL-8 | ||||||

| 1st Quartile | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| 2nd Quartile | 1.41 | 0.62 – 3.22 | 0.418 | 1.5 | 0.64 – 3.48 | 0.350 |

| 3rd Quartile | 1.04 | 0.45 – 2.41 | 0.925 | 1.12 | 0.49 – 2.60 | 0.787 |

| 4th Quartile | 2.09 | 0.98 – 4.45 | 0.056 | 2.22 | 1.04 – 4.74 | 0.039 |

| P trend | 1.24 | 0.99 – 1.57 | 0.067 | 1.27 | 1.00 – 1.60 | 0.048 |

| ≤ 75th Percentile | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| > 75th Percentile | 1.82 | 1.11 – 2.99 | 0.018 | 1.85 | 1.12 – 3.04 | 0.016 |

| 1.60 | 0.96 – 2.66 | 0.069# | ||||

Adjusted for age, gender, stage, histology, smoking status

Adjusted for age, gender, stage, histology, smoking status, IL-8

Adjusted for age, gender, stage, histology, smoking status, IL-6

Quartiles (25%, 50%, 75%) were based on serum IL-6 and IL-8 cut-off levels among controls in NCI-MD study (IL-6, 1.4, 2.1, 3.8 pg/mL; IL-8 7.0, 10.8 and 28.5 pg/mL).

Serum IL-6 and IL-8 levels were dichotomized into ≤ the median vs > the median among controls in the NCI-MD study (IL-6, 2.1 pg/mL; IL-8 10.8 pg/mL).

EA denotes European American

Selection criteria for LDCT included high-risk individuals with at least 30 pack-years of smoking, therefore we also conducted a stratified analysis by high and low pack-years of smoking (<30 vs. ≥30) to determine whether circulating levels of IL-6 and IL-8 remained significantly associated with risk of mortality in this population. IL-6 levels higher than the median (HR pack-years < 30 1.60, 95% C.I. 0.78 – 3.27, P=0.198, n=89) (HR pack-years ≥ 30 2.16, 95% C.I. 1.13 – 4.15, P=0.020, n=127), and IL-8 levels greater than the 75th percentile (HR pack-years < 30 1.06, 95% C.I. 0.21 – 5.40, P=0.946, n=39) (HR pack-years ≥ 30 1.92, 95% C.I. 1.07 – 3.44, P=0.028, n=127) were both significantly associated with a higher risk of lung cancer mortality in stage I patients with > 30 pack-years of smoking. Levels of TNFα, IL-1β or CRP were not associated with outcome of stage I lung cancer among patients with > 30 pack-years of smoking (Supplementary Table 3).

A combined IL-8 and IL-6 classifier is prognostic for stage I lung cancer

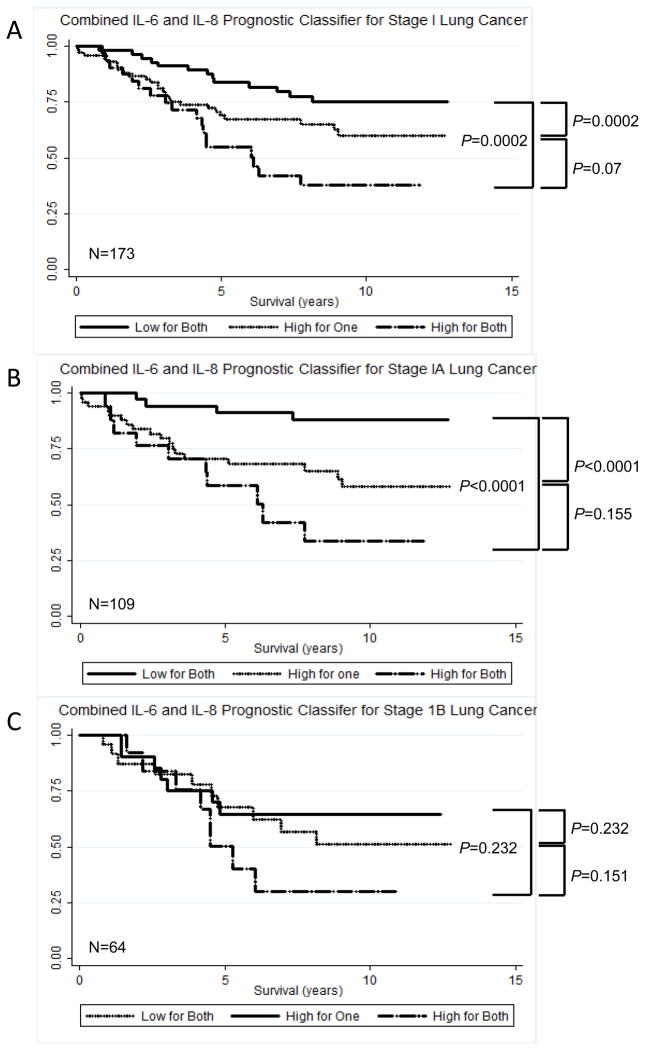

Biomarkers, when used alone, can misclassify some patients. However, combining two or more biomarkers together is likely to reduce this level of misclassification and therefore increase the accuracy of the prediction. For this to work however, the biomarkers should be independent of each other. As the association between IL-8 with lung cancer prognosis was independent of IL-6 in the multivariable model (Table 2), we reasoned that combining IL-8 and IL-6 into a single classifier could be more predictive of survival than either marker alone. Therefore, we created the following variable; 1 (IL-6 < median and IL-8 < 75th percentile) or (IL-6 ≥ median and IL-8 < 75th percentile or IL-6 < median and IL-8 ≥ 75th percentile), 2 (IL-6 ≥ median and IL-8 ≥ 75th percentile). In stage I patients, those with both high IL-8 and high IL-6 levels has significantly higher risk of lung cancer-specific death than those with low levels (HR High IL-6/High IL-8 vs Low IL-6/Low IL-8 3.14, 95% C.I. 1.50 – 6.60, P=0.002, n=166) (Figure 1) (Table 4). At five years, 73% of stage 1 patients with low levels of IL-8 and IL-6 were alive, compared to 46% of patients with high levels of IL-6 and IL-8 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves illustrating the survival times for patients with stage I (A), stage IA (B) and stage IB (C) lung cancer in the prostate, lung, colorectal and ovarian cancer screening trial.

Table 4.

Risk of lung cancer mortality and an IL-8/IL-6 signature in stage 1 lung cancer patients stratified by pack-years of smoking

| All | < 30 pack-years of smoking | ≥ 30 pack-years of smoking | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% C.I. | P | HR | 95% C.I. | P | HR | 95% C.I. | P | |

| Low for both | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| High for one | 1.58 | 0.78 – 3.14 | 0.192 | 1.57 | 0.85 – 2.89 | 0.151 | 1.39 | 0.63 – 3.04 | 0.411 |

| High for both | 3.14 | 1.50 – 6.60 | 0.002 | 2.4 | 1.23 – 4.68 | 0.996 | 3.58 | 1.59 – 8.08 | 0.002 |

| P trend | 1.78 | 1.22 – 2.60 | 0.003 | 1.19 | 0.46 – 3.07 | 0.723 | 1.95 | 1.27 – 3.00 | 0.002 |

Data adjusted for age, gender, histology, body mass index, bronchitis, emphysema, arthritis

Low IL-6 (≤ 1.4 pg/mL); High IL-6 (> 1.4 pg/mL)

Low IL-8 (≤ 28.5 pg/mL); High IL-8 (> 28.5 pg/mL)

As mentioned, there were 29 individuals who died from a cause of death other than lung cancer. A competing risks survival analysis indicated that the association between the IL6/IL-8 classifier with outcome was not affected by censoring of the 29 individuals who died of causes other than lung cancer (HR High IL-6/High IL-8 vs Low IL-6/Low IL-8 1.78, 95% C.I. 1.32 – 2.41, P<0.0001, n=166). This was also true for stage I lung cancer (HR High IL-6/High IL-8 vs Low IL-6/Low IL-8 3.18, 95% C.I. 1.59 – 6.39, P=0.001, n=166).

The combined IL-8/IL-6 classifier was associated with outcome of stage I lung cancer among current smokers (Supplementary Table 4). Furthermore, restricting the analysis to stage I patients with ≥ 30 pack-years of cigarettes we again found that the classifier was specifically associated with higher risk of mortality in this sub-group (HR High IL-6/High IL-8 vs Low IL-6/Low IL-8 3.58, 95% C.I. 1.59 – 8.08, P=0.002, n=127) (Table 4). Additional adjustments for potential confounding by past or prevalent chronic inflammatory conditions (HR High IL-6/High IL-8 vs Low IL-6/Low IL-8 3.58, 95% C.I. 1.59 – 8.08, P=0.002, n=125) or BMI at diagnosis, at age 20 and age 50 (HR High IL-6/High IL-8 vs Low IL-6/Low IL-8 3.27, 95% C.I. 1.39 – 7.73, P=0.007, n=121) did not alter the associations. To rule out the possibility that most stage I lung cancers were diagnosed close to serum collection, we also adjusted our model for the time interval between serum collection and lung cancer diagnosis, however our association remained statistically significant (HR High IL-6/High IL-8 vs Low IL-6/Low IL-8 3.16, 95% C.I. 1.54 – 6.47, P=0.002, n=166). Moreover, as our samples were taken at study entry, and not the exact time of diagnosis, we also tested the temporality of the prognostic signal in our samples. This is important, as were IL-8 and IL-6 to be used as a prognostic classifier in the clinic, it would be important to know if the association with prognosis is evident in samples taken around the time of diagnosis or whether the signal extends further back in time. For both cytokines, the signals were predominantly observed in samples taken approximately 3 months before diagnosis (Supplementary Table 5). For IL-6, an association with prognosis was also evident 1–3 years before diagnosis.

For patients with stage IA lung cancer, chemotherapy and radiation are not usually recommended, however, adjuvant treatment may be indicated for patients with stage IB lung cancer 33. We therefore refined our analysis further to look at the strength of the IL-8 and IL-6 classifier in stage IA (n=104) and stage IB (n=60) lung cancer. As shown in Figure 1B and Figure 1C, we found that patients with high levels of both IL-6 and IL-8 had significantly shorter survival times compared to those with low IL-6 and IL-8. In stage IA patients, although they will most likely have received surgery and not chemotherapy 33, the combined IL-6/IL-8 classifier was significantly associated with outcome (HR high for one vs low for both 3.23, 95% C.I. 1.07 – 9.74; P=0.038: HR high for both vs low for both 6.27, 95% C.I. 1.95 – 20.20; P=0.002). However, it will be important in the future as newer therapeutic options evolve to carry out studies that examine if, and how, radiation and chemotherapy influence the association between these cytokines and outcome.

Lung cancer is primarily classified into 4 main histological subtypes; adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, large cell carcinoma and small cell carcinoma. These share a common etiologic cause (i.e., tobacco) but also some distinct features and association with prognosis 34. We therefore tested the association between the IL-6/IL-8 classifier with risk of mortality from each histological subtype of lung cancer. As shown in Supplementary Table 6, the IL-6/IL-8 classifier was significantly associated with poor outcome of adenocarcinoma (HR 1.21, 95% C.I. 1.02 –1.43). While a similar trend was observed for squamous cell carcinoma, it was not significant. The IL-6 and IL-8 classifier was not associated with outcome of large cell or small cell carcinoma. However, the power to detect associations in subgroups is less. Levels of IL-6 and IL-8 did not significantly vary across the tumor subtypes (Table 1).

We then assessed it the IL-8/IL-6 classifier was associated with lung cancer outcome in patients who were diagnosed either by X-ray, ing or between screens. As mentioned, this study only included patients from the screening arm of PLCO and therefore there were no cases diagnosed from the non-screened arm of the study. There were 181 cases diagnosed by X-ray and 295 clinically diagnosed cases (189 of which were diagnosed post-screening and 96 that were diagnosed between screens). High levels of IL-8 and IL-6 were associated with poor outcome in patients whose lung cancer was diagnosed by X-ray (HRHigh for both vs. Low for both 1.81, 1.09 – 3.01; P=0.022) and in the post-screening period (HRHigh for both vs. Low for both 3.01, 1.38 – 3.15; P=0.003). However, the classifier was not associated with lung cancer in patients whose cancers were diagnosed between screens (HRHigh for both vs. Low for both 1.42, 0.71 – 2.82; P=0.323) (Supplemental Table 7). Similar results were observed for stage I cancer, although power was reduced. Thus, the association between the IL-6/IL-8 classifier with outcome

Discussion

We previously reported that an 11 gene inflammatory mRNA expression classifier, which included IL-6 and IL-8, was associated with lung cancer outcome 35. The classifier was derived from mRNA expression ratios of tumor and matched non-tumor lung tissue. Here we present data that this prognostic mRNA signal is systemically represented at the protein level in serum, a more readily accessible biospecimen. Furthermore, in line with our previous results with mRNA, we show that combining serum levels of IL-6 with IL-8 gives superior prognostic information compared to these markers alone. Some prospective studies have also found associations between circulating cytokines with lung cancer outcome 9, 10, 12, but few have investigated the association between circulating inflammatory markers and lung cancer survival in stage I disease. Our analyses were not corrected for multiple comparisons; however, the possibility for false discovery is reduced by the fact that it confirms other studies 8, 36. The NLST results suggest that focus on this group of patients will become increasingly important as this successful screening modality diagnoses a majority of stage I disease. Our results show that the IL-6/IL-8 classifier is associated with outcome of stage I disease, which is in agreement with our previous results with a mRNA cytokine gene classifier 35.

Several lines of evidence suggest that the systemic inflammatory signal emanates from the tumor itself. In addition to studies that show lung cancer cells express higher levels of IL-8 and IL-6 35, 37, numerous studies have also shown that inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6 and IL-8, and free radicals 38 play a direct role in lung carcinogenesis 39–42. Prevalent inflammatory disorders could confound inflammatory signals relating to tumor incidence and outcome, however our analyses were independent of past or prevalent inflammatory disorders. They were also independent of smoking, which is again important given that smoking can increase levels of IL-6 and IL-8 and the fact that smoking has been associated with poor survival 5, 43, 44. Potential limitations of our work include a restricted analysis to a sub-group of inflammatory markers. However given the study design and assay matrix geometry we were limited to this number. Recent studies have suggested that an expanded cytokine profile might also be predictive of outcome in lung cancer 12 and an expanded profile could therefore be studied further. Studies of circulating cytokines are open to confounding by prevalent systemic inflammatory conditions, and while we adjusted for a number of these in our analysis, it is possible that other conditions, such as asthma and COPD, could have confounded our results. Additional studies should aim to additionally control for these conditions.

In light of a series of studies that now show circulating serum cytokines are associated with lung cancer prognosis, several questions and directions remain to be explored. For example, our analysis was based on a cut-off derived from European American controls in our previous study. Whether or not these are the most apt and informative concentrations in the larger population remains to be determined. Additionally, studies will be needed to determine whether IL-8 and IL-6 are uniformly associated with prognosis in populations across geographical regions; analysis of recent data suggests that they may not be 8, 45–48. Moreover, selection of the appropriate biofluid, such as serum versus plasma, may also be an important choice 49. Further follow-up studies will also be required to define whether circulating inflammatory markers could be used as an early marker of tumor recurrence. This is not just an unmet need in the clinical management of lung cancer, but one where IL-6 and IL-8 could be particularly useful. Our recent data showed that IL-6 and IL-8 expression in lung cancer tissue is higher than in non-tumor tissue 35. We recently reported that increased levels of circulating IL-8 were predictive of lung cancer up to five years prior to clinical diagnosis and that circulating levels of IL-6 are associated with lung cancer diagnosis 21. These results, and recent work from animal models of cancer showing elevated serum levels of IL-6 and VEGF coincident with tumor recurrence, suggest that monitoring cytokines in the circulation could be an effective means of following tumor relapse. Another factor that will need to be refined in larger studies is whether or not this cytokine profile, or indeed whether an alternative one, is prognostic of outcome from adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, small cell or large cell carcinoma. The data in this study suggest that the association is strongest of adenocarcinoma.

Uncertainty remains with regard to how patients with stage 1B lung cancer should be treated50–52; some studies suggest that stage IB patients should be given post-operative adjuvant chemotherapy 53, 54 while others do not 55–57. Although we had limited power, we conducted a separate analysis of stage 1A and stage 1B patients. We found that 54% of patients with low levels of IL6 and IL-8 were alive after 5 years, compared to only 38% of patients with high levels of both cytokines. At 10 years, the difference in survival was more pronounced; 20% of stage IB patients with low levels of IL-6 and IL-8 were alive, compared to only 8% of patients with high levels of these cytokines. Moreover, the risk of mortality in the 104 stage IA patients, who are more likely to receive surgery without further chemotherapy, was (HR high for one vs low for both 3.23, 95% C.I. 1.07 – 9.74; P=0.038: HR high for both vs low for both 6.27, 95% C.I. 1.95 – 20.20; P=0.002). Stage IB patients sometimes undergo chemotherapy, although long term evidence that this provides a patient benefit is contradictory. While this data is preliminary, it suggests that further study of stage 1B patients should be carried out to further define the prognostic utility of these markers. Furthermore, analyses that include the treatment regimens these patients underwent would be additionally informative.

In summary, we have shown that a combined IL-6 and IL-8 classifier is associated with outcome in stage I lung cancer in a prospective study with up to 13 years of follow-up. Our work confirms our previous findings 8 and extends that of others 12, 36. Sufficient evidence now exists to begin to refine the association between these markers with clinical outcome and to ascertain both the scope, and limitations, of these markers in the clinical setting. In addition, given the specific relationship between these markers with outcome of stage I lung cancer in heavy smokers, the potential use of these markers within a screening setting, such as that with LDCT, should be explored. This is important, as recent studies suggest that screen-detected lung cancers may have a different natural history from that of clinically-detected lung cancer 58, 59, and there is a pressing need to address the consequences associated with over-diagnosis of screen-detected lung cancer 7. Our sub-group analysis of X-ray versus clinically diagnosed lung cancer did not suggest that there was a difference between these two groups, but this will have to be confirmed for LDCT-detected lung cancer. Analyses of this, and other, promising prognostic classifiers should be explored within such a trial to confirm their utility and potential for improving health outcomes among patients with lung cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

The authors do not have any financial, consultant or institutional conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Kan Q, Jinno S, Yamamoto H, et al. Chemical DNA damage activates p21 WAF1/CIP1-dependent intra-S checkpoint. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:5879–5884. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.11.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okayama M, Hayashi S, Aoi Y, et al. Aggravation by selective COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitors of dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colon lesions in rats. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2095–2103. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9597-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffman PC, Mauer AM, Vokes EE. Lung cancer. Lancet. 2000;355:479–485. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)82038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hussain SP, Amstad P, Raja K, et al. Increased p53 mutation load in noncancerous colon tissue from ulcerative colitis: a cancer-prone chronic inflammatory disease. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3333–3337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kovalchik SA, Tammemagi M, Berg CD, et al. Targeting of low-dose CT screening according to the risk of lung-cancer death. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:245–254. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S.P.T.F. Screening for Lung Cancer US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. 2013 Available at http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf13/lungcan/lungcanfinalrs.htm.

- 7.Patz EF, Jr, Pinsky P, Gatsonis C, et al. Overdiagnosis in low-dose computed tomography screening for lung cancer. JAMA internal medicine. 2014;174:269–274. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enewold L, Mechanic LE, Bowman ED, et al. Serum concentrations of cytokines and lung cancer survival in African Americans and Caucasians. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:215–222. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alifano M, Falcoz PE, Seegers V, et al. Preresection serum C-reactive protein measurement and survival among patients with resectable non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142:1161–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hong S, Kang YA, Cho BC, et al. Elevated serum C-reactive protein as a prognostic marker in small cell lung cancer. Yonsei Med J. 2012;53:111–117. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2012.53.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Srimuninnimit V, Ariyapanya S, Nimmannit A, et al. C-reactive protein as a monitor of chemotherapy response in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (CML study) J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95 (Suppl 2):S199–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okayama H, Nishimura K, Saito M, et al. Significance of the distal to proximal coronary flow velocity ratio by transthoracic Doppler echocardiography for diagnosis of proximal left coronary artery stenosis. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography: official publication of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2008;21:756–760. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2007.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kita H, Shiraishi Y, Watanabe K, et al. Does postoperative serum interleukin-6 influence early recurrence after curative pulmonary resection of lung cancer? Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;17:454–460. doi: 10.5761/atcs.oa.10.01627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott HR, McMillan DC, Forrest LM, et al. The systemic inflammatory response, weight loss, performance status and survival in patients with inoperable non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:264–267. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vlachostergios PJ, Gioulbasanis I, Kamposioras K, et al. Baseline insulin-like growth factor-I plasma levels, systemic inflammation, weight loss and clinical outcome in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer patients. Oncology. 2011;81:113–118. doi: 10.1159/000331685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hijikata A, Kitamura H, Kimura Y, et al. Construction of an open-access database that integrates cross-reference information from the transcriptome and proteome of immune cells. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2934–2941. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turin TC, Kita Y, Rumana N, et al. Registration and surveillance of acute myocardial infarction in Japan: monitoring an entire community by the Takashima AMI Registry: system and design. Circulation journal: official journal of the Japanese Circulation Society. 2007;71:1617–1621. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho LH, Ohno T, Oboki K, et al. IL-33 induces IL-13 production by mouse mast cells independently of IgE-FcepsilonRI signals. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2007;82:1481–1490. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0407200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.IARC. A Review of Human Carcinogens: Arsenic, Metals, Fibres, and Dusts. Lyon, France: 2012. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; p. 100c. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pine SR, Mechanic LE, Enewold L, et al. Increased levels of circulating interleukin 6, interleukin 8, C-reactive protein, and risk of lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1112–1122. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rusch VW, Giroux DJ, Kraut MJ, et al. Induction chemoradiation and surgical resection for superior sulcus non-small-cell lung carcinomas: long-term results of Southwest Oncology Group Trial 9416 (Intergroup Trial 0160) J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:313–318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ochiai T, Sonoyama T, Kikuchi S, et al. Results of repeated hepatectomy for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:858–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller AB, Yurgalevitch S, Weissfeld JL, et al. Death review process in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial. Control Clin Trials. 2000;21:400S–406S. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471–1474. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu YW, Tadamura E, Yamamuro M, et al. Estimation of global and regional cardiac function using 64-slice computed tomography: a comparison study with echocardiography, gated-SPECT and cardiovascular magnetic resonance. International journal of cardiology. 2008;128:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chaturvedi AK, Caporaso NE, Katki HA, et al. C-reactive protein and risk of lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2719–2726. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hess KR. Graphical methods for assessing violations of the proportional hazards assumption in Cox regression. Stat Med. 1995;14:1707–1723. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780141510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakata T, Okamoto A, Morita T, et al. Age- and gender-related differences of plasma prothrombin activity levels. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97:1052–1053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Savichtcheva O, Okayama N, Okabe S. Relationships between Bacteroides 16S rRNA genetic markers and presence of bacterial enteric pathogens and conventional fecal indicators. Water research. 2007;41:3615–3628. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howington JA, Blum MG, Chang AC, et al. Treatment of stage I and II non-small cell lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143:e278S–313S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirsch FR, Spreafico A, Novello S, et al. The prognostic and predictive role of histology in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a literature review. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:1468–1481. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318189f551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seike M, Yanaihara N, Bowman ED, et al. Use of a cytokine gene expression signature in lung adenocarcinoma and the surrounding tissue as a prognostic classifier. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1257–1269. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bodelon C, Polley MY, Kemp TJ, et al. Circulating levels of immune and inflammatory markers and long versus short survival in early-stage lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2073–2079. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turin TC, Kita Y, Murakami Y, et al. Increase of stroke incidence after weekend regardless of traditional risk factors: Takashima Stroke Registry, Japan; 1988–2003. Cerebrovascular diseases. 2007;24:328–337. doi: 10.1159/000106978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okayama H, Saito M, Oue N, et al. NOS2 enhances KRAS-induced lung carcinogenesis, inflammation and microRNA-21 expression. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:9–18. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hussain SP, Hofseth LJ, Harris CC. Radical causes of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:276–285. doi: 10.1038/nrc1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu YW, Tadamura E, Kanao S, et al. Left ventricular functional analysis using 64-slice multidetector row computed tomography: comparison with left ventriculography and cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Cardiology. 2008;109:135–142. doi: 10.1159/000105555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marrogi AJ, Travis WD, Welsh JA, et al. Nitric oxide synthase, cyclooxygenase 2, and vascular endothelial growth factor in the angiogenesis of non-small cell lung carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:4739–4744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Munesue S, Yoshitomi Y, Kusano Y, et al. A novel function of syndecan-2, suppression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 activation, which causes suppression of metastasis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28164–28174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609812200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shiels MS, Pfeiffer RM, Hildesheim A, et al. Circulating Inflammation Markers and Prospective Risk of Lung Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shiels MS, Engels EA, Shi J, et al. Genetic variation in innate immunity and inflammation pathways associated with lung cancer risk. Cancer. 2012;118:5630–5636. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimzukawa M, Sakakibara T, Sato M, et al. Tuberculosis in two patients after administration of etanercept for rheumatoid arthritis. Nihon Naika Gakkai zasshi The Journal of the Japanese Society of Internal Medicine. 2007;96:1476–1478. doi: 10.2169/naika.96.1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakamura K, Okamura T, Hayakawa T, et al. The proportion of individuals with obesity-induced hypertension among total hypertensives in a general Japanese population: NIPPON DATA80, 90. European journal of epidemiology. 2007;22:691–698. doi: 10.1007/s10654-007-9168-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takajo I, Umeki K, Morishita K, et al. Engraftment of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 carriers in NOD/SCID/gammac(null) (NOG) mice. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:2205–2211. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tatsumi T, Ashihara E, Yasui T, et al. Intracoronary transplantation of non-expanded peripheral blood-derived mononuclear cells promotes improvement of cardiac function in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation journal: official journal of the Japanese Circulation Society. 2007;71:1199–1207. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoneyama S, Miura K, Itai K, et al. Dietary intake and urinary excretion of selenium in the Japanese adult population: the INTERMAP Study Japan. European journal of clinical nutrition. 2008;62:1187–1193. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strauss GM, Herndon JE, 2nd, Maddaus MA, et al. Adjuvant paclitaxel plus carboplatin compared with observation in stage IB non-small-cell lung cancer: CALGB 9633 with the Cancer and Leukemia Group B, Radiation Therapy Oncology Group, and North Central Cancer Treatment Group Study Groups. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5043–5051. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.4855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Winton T, Livingston R, Johnson D, et al. Vinorelbine plus cisplatin vs. observation in resected non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2589–2597. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Butts CA, Ding K, Seymour L, et al. Randomized phase III trial of vinorelbine plus cisplatin compared with observation in completely resected stage IB and II non-small-cell lung cancer: updated survival analysis of JBR-10. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:29–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.0333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kato H, Ichinose Y, Ohta M, et al. A randomized trial of adjuvant chemotherapy with uracil-tegafur for adenocarcinoma of the lung. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1713–1721. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roselli M, Mariotti S, Ferroni P, et al. Postsurgical chemotherapy in stage IB nonsmall cell lung cancer: Long-term survival in a randomized study. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:955–960. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Winton T, Livingston R, Johnson D, et al. Vinorelbine plus cisplatin vs. observation in resected non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2589–2597. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Douillard JY, Rosell R, De Lena M, et al. Adjuvant vinorelbine plus cisplatin versus observation in patients with completely resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (Adjuvant Navelbine International Trialist Association [ANITA]): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:719–727. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70804-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wakelee H, Dubey S, Gandara D. Optimal adjuvant therapy for non-small cell lung cancer--how to handle stage I disease. Oncologist. 2007;12:331–337. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-3-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takashima N, Shioji K, Kokubo Y, et al. Validation of the association between the gene encoding proteasome subunit alpha type 6 and myocardial infarction in a Japanese population. Circulation journal: official journal of the Japanese Circulation Society. 2007;71:495–498. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kido T, Kurata A, Higashino H, et al. Cardiac imaging using 256-detector row four-dimensional CT: preliminary clinical report. Radiation medicine. 2007;25:38–44. doi: 10.1007/s11604-006-0097-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.