Abstract

Mammalian PAF49 and PAF53 form a heterodimer and are essential for transcription. However their roles in transcription have not been specifically defined. While the yeast homologues are "not essential" proteins, yeast cells deficient in the homologue of PAF53 grow at 50–66% the wild-type rate at 30C, but fail to grow at 25C (1, 2). There is increasing evidence that these proteins may play important roles in transcription initiation and elongation.

We have found that while some cells regulated the protein levels of both PAF53 and PAF49, other cells did not. However, in either case they regulated the nucleolar levels of the PAFs. In addition, we found that the association of PAF49/PAF53 with Pol I is regulated. In examining the mechanism that might regulate this association, we have found that PAF49 is acetylated on multiple sites. The acetylation state of PAF49 does not affect heterodimerization. However, hypoacetylated heterodimer binds to Pol I with greater affinity than acetylated heterodimer. Further, we have found that the heterodimer interacts with Rrn3. We propose a model, in which there is a biochemical interaction between the Pol I-associated heterodimer and Rrn3 and that this interaction facilitates the recruitment of Rrn3 to the polymerase. As the binding of Rrn3 to Pol I is essential to transcription initiation in yeast and mammals, our results provide a greater understanding of the regulation of Rrn3 function and provide biochemical underpinning for the roles of the PAF49/PAF53 heterodimer in transcription initiation and elongation by Pol I.

Keywords: acetylation, ribosomal RNA, nucleolus, Rrn3

1. Introduction

Schultz and Caspersson and Brachet (3, 4) were the first authors to demonstrate an increased RNA content in rapidly growing tissues. In fact, they had observed a correlation between the growth rate and the rRNA content of a cell as subsequently demonstrated in prokaryotic cells by Schaechter et al. (5) and in eukaryotic cells by Becker et al. (6). Studies in many laboratories have demonstrated that this is the result of increased rates of rDNA transcription, and that there are multiple levels of control of the rDNA transcription apparatus in eukaryotes (7–9).

In 1975, Huet et al. (10) reported the isolation of two forms of RNA polymerase I from yeast that they referred to as RNA polymerase A and RNA polymerase A*. They reported that RNA polymerase A* "was lacking two polypeptide chains of 48,000 and 37,000 daltons", now referred to as A49 and A34.5, respectively. They also reported biochemical differences between Pol A and Pol A*, including their ability to transcribe various synthetic substrates. Subsequent studies on the yeast Pol I structure demonstrated that the two subunits most likely interacted with the core Pol I as a heterodimer (11).

In 1996, Hanada et al. (12) reported the isolation of two forms of mammalian RNA polymerase I, Pol IA and Pol IB. They reported evidence that Pol IB contained several subunits, noticeably subunits of 53 and 49 kDa that were associated with transcriptionally competent Pol I and that Pol IA did not function in specific transcription. They obtained molecular clones of the 53kDa subunit, PAF53, and noted that it was similar to the yeast Pol I subunit A49.

Further, Hanada et al. (12) reported evidence for a positive correlation between the nucleolar accumulation of PAF53 and rDNA transcription, i.e. nucleoli of serum starved 3T3 cells were depleted in PAF53 which accumulated in the nucleoli of actively growing cells. These results have been controversial. Seither et al. (13) reported that the association of PAF53 withPAF49 was constitutive, while Hannan et al. (14) reported evidence for the growth-dependent regulation of PAF53 in 3T6 cells.

Subsequent studies by Yamamoto et al. (15) demonstrated that the 49kDa subunit of mammalian Pol I, PAF49, formed a heterodimer with PAF53, similar to that formed by the yeast subunits A49 and A34.5. They also demonstrated that PAF49 was regulated similar to the regulation of PAF53. Studies in yeast demonstrated that the A49 and A34.5 subunits formed a heterodimer (16) Studies on the role(s) of the heterodimer indicate that the complex is structurally and functionally related to the TFIIE and TFIIF components of the Pol II GTF. The A49 and A34.5 heterodimerization module is related to modules in the Pol III (the C37–C53 heterodimer) (17) and in Pol-II (TFIIF)(18). In addition, the tandem winged-helix (tWH) domain in A49 is related to DNA-binding domains in Pol III (C34) and the GTF, TFIIE, (18). The complex can bind DNA (A49), function in RNA cleavage and may promote elongation (16, 18). Further, the heterodimers may function at several stages in the Pol I transcription cycle. Various studies indicate that it may play roles in recruitment, promoter escape and elongation (2, 16, 19–21).

As mentioned above, the multisubunit Pol I complex exists as at least two distinct subpopulations (10, 22, 23). Both forms of Pol I are active and can catalyze the synthesis of RNA, but only Pol Ib, which represents less than 10% of the total Pol I in a yeast cell, will initiate accurate transcription. This is due, at least in part, to the association of Pol Ib with Rrn3 (12, 13) (mammalian Rrn3,sometimes referred to as TIF1A (24, 25). Rrn3 interacts directly with Pol I, through its A43 subunit (26, 27). Genetic studies in yeast have also demonstrated that the A49/A34.5 heterodimer is important for the association and dissociation of Rrn3 with Pol I. However, biochemical data supporting a possibly direct interaction between Rrn3 and the heterodimer has been unavailable (2).

We have examined several aspects of the biology and biochemistry of the heterodimer. First, we have found that when cells are arrested and rDNA transcription repressed due to serum starvation, we observe a decrease in the nucleolar content of PAF53. In some cell lines, this is associated with a decrease in the cell content of PAF53 and PAF49, by ~70%. However, in other cells, we only observe a 30% decrease in PAF53 and PAF49 levels. In addition, the serum-deprivation driven decrease in nucleolar localization is associated with a decrease in the association of PAF53 with Pol I. However, serum starvation does not affect the formation of the heterodimer. While seeking to understand the mechanism that might explain the regulation of PAF53 and PAF49, we observed that PAF49 was more highly acetylated than PAF53 (28). We have tentatively identified two sites of acetylation in PAF49. Mutation of the lysines in these putative acetylation sites does not affect the ability of PAF49 to heterodimerize with PAF53. However, heterodimers that contain hypoacetylated PAF49 interact more strongly with core RNA polymerase than those that contain wild-type PAF49. Using affinity purified heterodimers, we have been able to demonstrate an interaction between the heterodimer and Rrn3. Interestingly, neither PAF53 nor PAF49 by itself interacted with Rrn3, and the interaction was strongest when the PAF49 was hypoacetylated. It has been reported that SirT7 associates with Pol I and can activate rDNA transcription (29, 30). Our data is consistent with this finding, and with the model that the deacetylation of PAF49 is at least one component of the mechanism through which SirT7 functions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Tissue Culture, Transfection, Stable Cell Lines and Cell

NIH 3T3, NIH 3T6 and HEK293 cells were grown as described previously (31, 32). Cells were plated in DMEM, 5% FBS at 2×106 cells per 100mm dish, and transfected the next day using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions or CaPO4 (33). Transfections were carried out for 24 or 48 hr for 293 and 3T3 cells, respectively. To establish cell lines that constitutively expressed tagged proteins, G418 (500 µg/ml) was first added to the tissue culture media forty-eight hours after transfection. Fourteen days later, the cells were cloned in 96 well plates and individual clones grown and characterized for transgene expression (34).

2.2 Ligand and Immunoaffinity Purification

Forty-eight hours post transfection, whole cell lysates were prepared as described previously (35). Cells were scraped into lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, containing protease inhibitors (Complete, Roche Molecular Biochemicals)) and either used immediately or frozen at −80°C until needed (27, 34, 36, 37). As necessary, the lysates were tumbled with anti-FLAG-agarose, immobilized nickel (Ni-NTA agarose, Qiagen) or GSH-agarose for 2h at 4°C. The bound proteins were eluted with FLAG peptide (500 µg/ml), imidazole (500 mM) or reduced GSH (50 mM), or the beads were boiled in SDS sample buffer, and the eluted proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using anti-FLAG, anti-GST, anti-HA or antibodies specific to PAF53 or PAF49 as described previously (27). DEAE-Sephadex column chromatography of whole cell extracts was carried out essentially as described previously (38).

2.3 Immunoblotting

Protein determinations were performed using the Bio-Rad D-C protein assay kit with bovine serum albumin as the protein standard. Western blots were carried out as described previously (37). The molecular sizes of the immunodetected proteins were verified by comparison to the migration of prestained protein markers (Bio-Rad) electrophoresed in parallel lanes (39). Antibodies to PAF53 and mammalian A127 have been described previously (37). The antibodies to GFP were obtained from Clontech, the antibodies to GST were obtained from Sigma.

2.4 Mutagenesis of PAF53 and PAF49

Full-length or mutants of PAF53 or PAF49 were cloned into pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen), PKH3 BSENX, and/or pEBG as required. Various epitope tags were added to the coding regions by PCR. Substitution mutants were constructed by PCR-directed mutagenesis using overlapping primers based on the sequences of the cDNA and the vector. All the amplification reactions were performed using iProof polymerase (Bio-Rad). All mutant constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The initial clones for PAF53 and PAF49 were obtained from the laboratory of Dr. Masami Muramatsu.

3. Results and Discussion

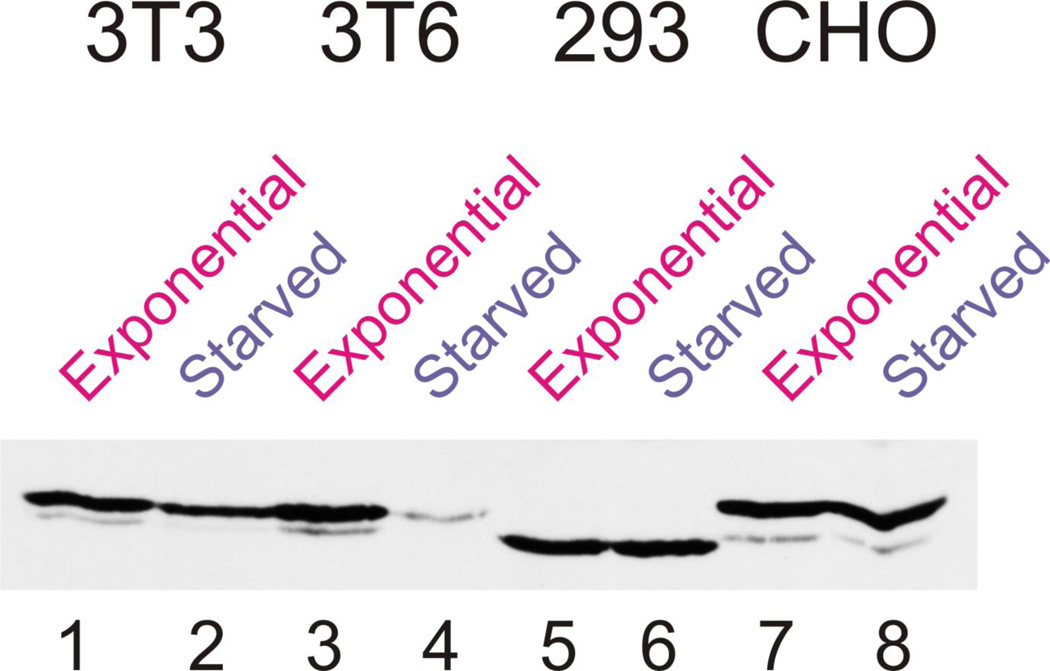

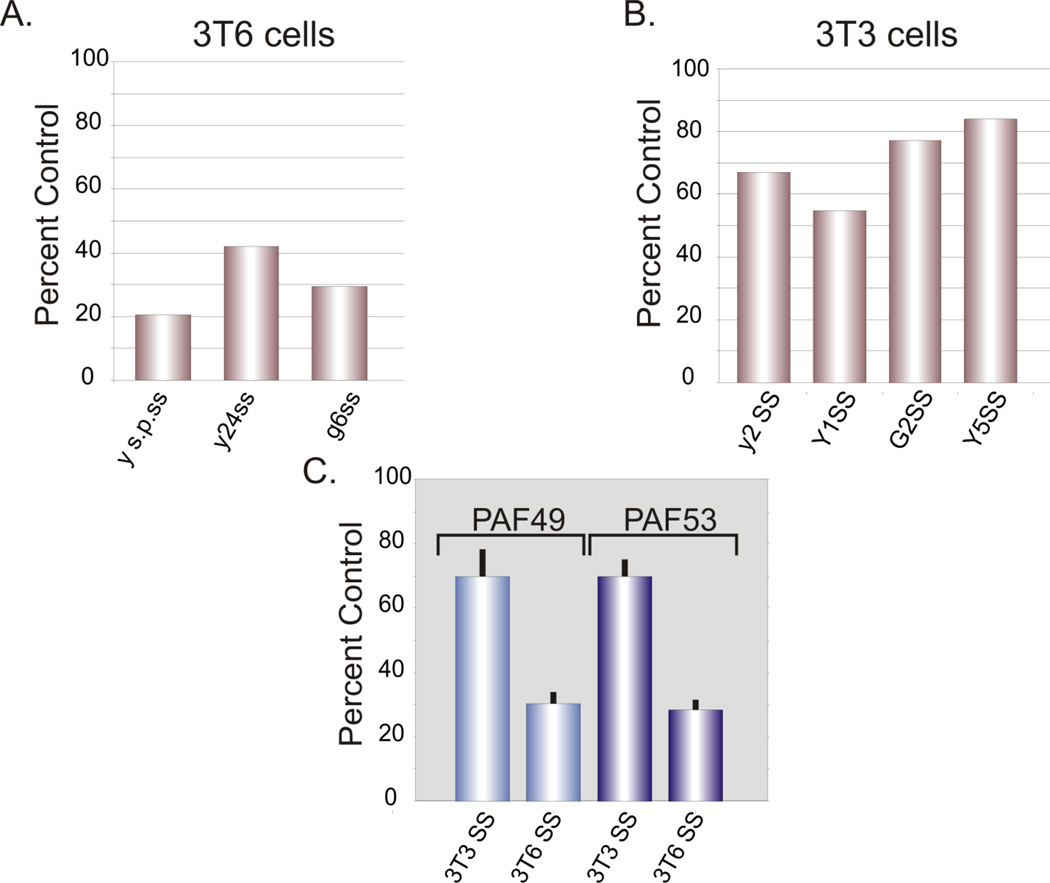

As there were discrepancies between the various reports of the effects of serum starvation on the nuclear localization or cellular levels of PAF49/53, we reinvestigated this issue. We examined the cellular levels of PAF53 in NIH3T3 and NIH3T6 cells. When 3T6 cells were serum-starved, whole cell levels of PAF53 were reduced by ~70% (Figure 1, lanes 3 and 4). This reproduced our initial observation (14) using this same cell line. However, when the experiment was carried out using serum-starved NIH3T3, 293 and CHO cells, we only observed a 20–30% reduction in whole cell levels of PAF53 (Figure 1, lanes 1 and 2, 5 and 6 and 7 and 8). These results, especially those from two closely related cell lines, 3T3 and 3T6 (40), lead to two very different models. In one case, one could argue that the pattern of regulation of PAF53 observed in 3T6 cells is not relevant to the down-regulation of rDNA transcription observed when these cells are serum-starved. On the other hand, it might be that the regulation of PAF53 is pertinent to the regulation of rDNA transcription, but different cell lines might utilize different mechanisms. For example, 3T6 cells might regulate the levels of PAF53 and 3T3 cells might regulate its nucleolar localization. In order to examine this question, we established cell lines that constitutively expressed GFP-tagged PAF53 and GFP-tagged PAF49, as PAF53 and PAF49 form a heterodimer on the polymerase. In order to obviate differences that might arise to expression levels or sites of insertion, multiple clones of both NIH3T3 and NIH3T6 cells that stably expressed the two proteins were used. In the first series of experiments, we examined the regulation of these ectopically expressed proteins. Western blots of two separate 3T3 clones expressing tagged-PAF53, demonstrated that the protein level decreased 29±7% upon serum-starvation (data not shown). This was in agreement with the values by which serum starvation affected the endogenous protein. We observed essentially the same pattern of regulation of ectopically expressed PAF49 in three clones of 3T3 cells (30% ±12%; Figure 2). When these experiments were repeated using clones established using 3T6 cells, we found that serum-starvation reduced the levels of both PAF49 and PAF53 by 70%±10%. These data are summarized in Figure 2. The ectopically expressed, PAF53 is being regulated similarly to the endogenous protein. As the data demonstrate that 3T6 cells regulate the whole cell content of the PAFs, we sought to determine if the 3T3 cells regulated their nucleolar localization. Regulating the nucleolar concentration of the PAFs would accomplish the same "goal" of reducing the ability of the PAFs to participate in rDNA transcription. In one sense this would demonstrate a finer level of control than that demonstrated in the 3T6 cells.

Figure 1.

PAF53 levels are affected differentially by serum starvation. The various cell lines indicated were grown exponentially in 10% FBS or were serum starved for 24hr in 0.1% FBS. After cells were harvested by scraping into SDS sample buffer, equal amounts of lysates (protein) were fractionated by SDS-PAGE. PAF53 levels were determined by western blotting with a rabbit polyclonal anti-PAF53 antibody as described previously (37).

Figure 2.

PAF49 and PAF53 are coordinately regulated. Individual clones of 3T6 cells (A) or 3T3 cells (B) expressing GFP-tagged PAF53 were serum starved for 24 hours and the whole cell levels of the tagged proteins were determined by western blots as described in Materials and Methods. (C) Mean values derived from experiments similar to those in Panels A and B for the effects of serum starvation on the whole cell levels of GFP-PAF49 and GFP-PAF53 in clones of 3T3 and 3T6 cells.

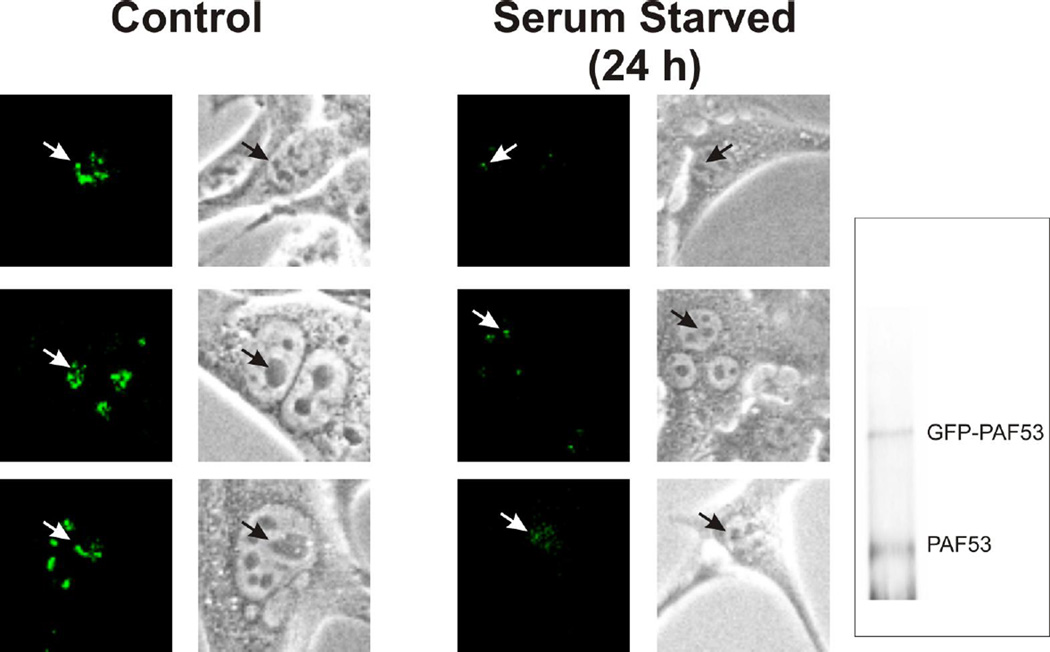

As shown in Figure 3, when 3T3 cells were serum-starved we observed a significant depletion in the nucleolar levels of the tagged PAF53. Similar results were seen when we examined the nucleolar levels of tagged PAF49 (data not shown). These results suggested that in both cell lines we had observed parallel regulation of the two PAFs. We then asked if serum starvation 1) caused the PAFs to dissociate from core Pol I and/or 2) affected heterodimer formation.

Figure 3.

Nucleolar levels of PAF53 decrease when 3T3 cells are serum starved. 3T3 cells that stably expressed GFP-tagged PAF53 were grown exponentially or serum starved (0.1% FBS) for twenty-four hours and then photographed using either fluorescence or phase optics. Arrows indicate the fluorescence signals in the indicated nucleoli. Inset: Anti-PAF53 western blot of whole cell extracts of the clone used in the immunolocalization experiment demonstrates the relative levels of GFP-PAF53 and the endogenous protein.

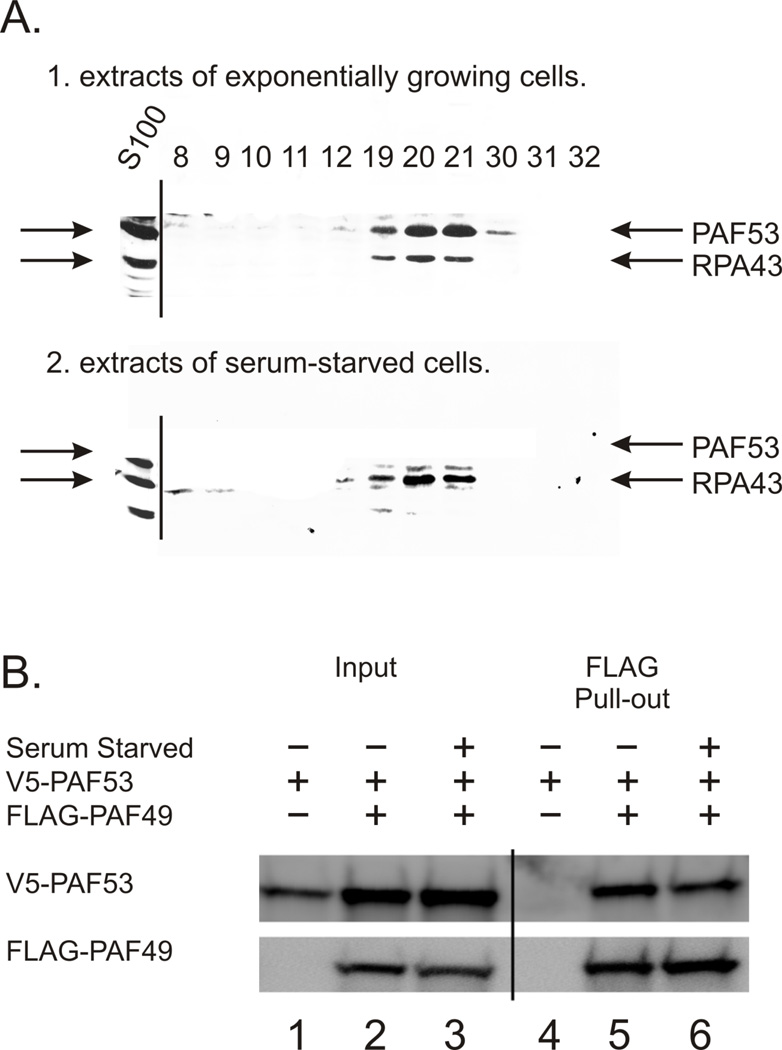

NIH 3T3 cells were grown to 50% confluence and then serum-starved for 24 hr. Whole cell extracts prepared from control (exponentially growing cells) and from the serum-starved cells were subject to DEAE-Sephadex column chromatography as described previously (38). Equal aliquots of the fractions containing RNA polymerase I activity from the chromatography samples were analyzed for both rpa43, as an indicator of core polymerase, and PAF53. As shown in Figure 4 (panel A), PAF53 coeluted with rpa43 in fractions 12–30. In contrast, the western blot of the chromatogram of the serum-starved sample did not display a significant level of PAF53 in the fractions that contained rpa43. These data are consistent with the cytochemistry data. They suggest that the nucleolar depletion of PAF53 is associated with its dissociation from RNA polymerase I.

Figure 4.

Serum starvation causes the dissociation of PAF53 from RNA polymerase I, but does not cause the heterodimer to dissociate. A. S100 extracts from control or serum-starved (48hr) NIH 3T3 cells were fractionated by DEAE-Sephadex chromatography. Equal aliquots of the polymerase containing fractions were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF. The blots were then probed with rabbit polyclonal antibodies for the indicated proteins. B. 293T cells were transfected with vectors driving the expression of the indicated proteins. Twenty-four hours post transfection, the cells were serum starved for 48 hours and then lysates were harvested for western blot analysis as described in Materials and Methods. Control cells were allowed to grow for a total of 48hr post transfection.

As PAF53 forms a heterodimer with PAF49 ((18, 35) and references therein), we then asked if serum-starvation caused the heterodimer to dissociate. 293T cells were transfected with vectors driving the expression of tagged versions of both PAF53 and PAF49 and then subject to serum starvation for 48hr. FLAG-tagged PAF49 was purified from extracts of the serum-starved cells using immobilized anti-FLAG antibodies, and the pulled-down proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and western blotting. As expected, the FLAG-purified PAF49 from extracts from exponentially growing cells copurified with PAF53 (Fig 4, panel B, lane 5). Interestingly, the FLAG-purified PAF49 from serum-starved cells also copurified with PAF53 (Fig 4, panel B, lane 6). This indicates that serum starvation did not affect the formation of the heterodimer.

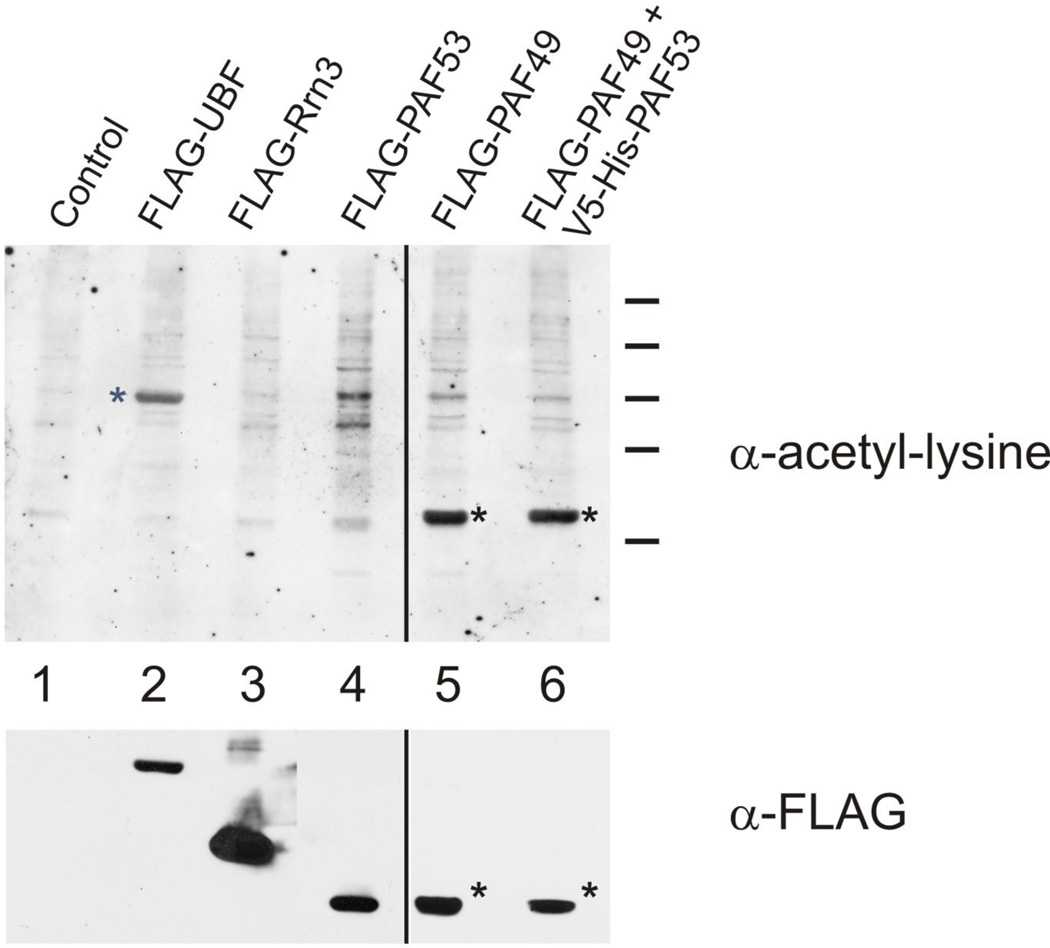

We have previously reported (35) that both PAF49 and PAF53 can interact with core Pol I. Also, it has recently been reported that the deacetylation of PAF53 might contribute to the regulation of rDNA transcription (29). Thus, we asked if it was possible that PAF49 was acetylated and if the acetylation of PAF49 might also contribute to the regulation of the association of PAF49/53 with Pol I. As shown in Figure 5, we found that PAF49 was acetylated and that ectopically expressed PAF49 was more highly acetylated than PAF53.

Figure 5.

PAF49 is acetylated. 293T cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1 containing inserts that would drive the indicated proteins. Forty-eight hours post transfection, whole cell lysates were prepared and the FLAG-tagged proteins purified by immunoaffinity pull-down on immobilized anti-FLAG antibodies. The proteins that bound to the anti-FLAG beads were analyzed by western blotting using anti-acetyl-lysine and then anti-FLAG antibodies as described in Materials and Methods.

In this experiment (Figure 5), 293T cells were transfected with vectors driving the expression of the indicated FLAG-tagged proteins. Forty-eight hours post transfection, the proteins were purified from extracts of the cells by immuno-affinity pull-down using immobilized anti-FLAG antibodies. Analysis of the immunopurified proteins using both anti-FLAG and anti-acetyl lysine antibodies demonstrated that UBF (lane 2; used as a positive control (41)) and PAF49 (*, lanes 5 and 6) were both acetylated, and that there was a low level of acetylation of PAF53 (lane 4). The low level of acetylation of PAF53, consistent with previous reports (29), is apparent when one compares the anti-FLAG blots of PAF49 and PAF53 in the bottom panel with the corresponding anti-acetyl-lysine blot in the upper panel. Using FLAG-affinity purified Pol I (37), we confirmed that endogenous PAF49 was acetylated (data not shown).

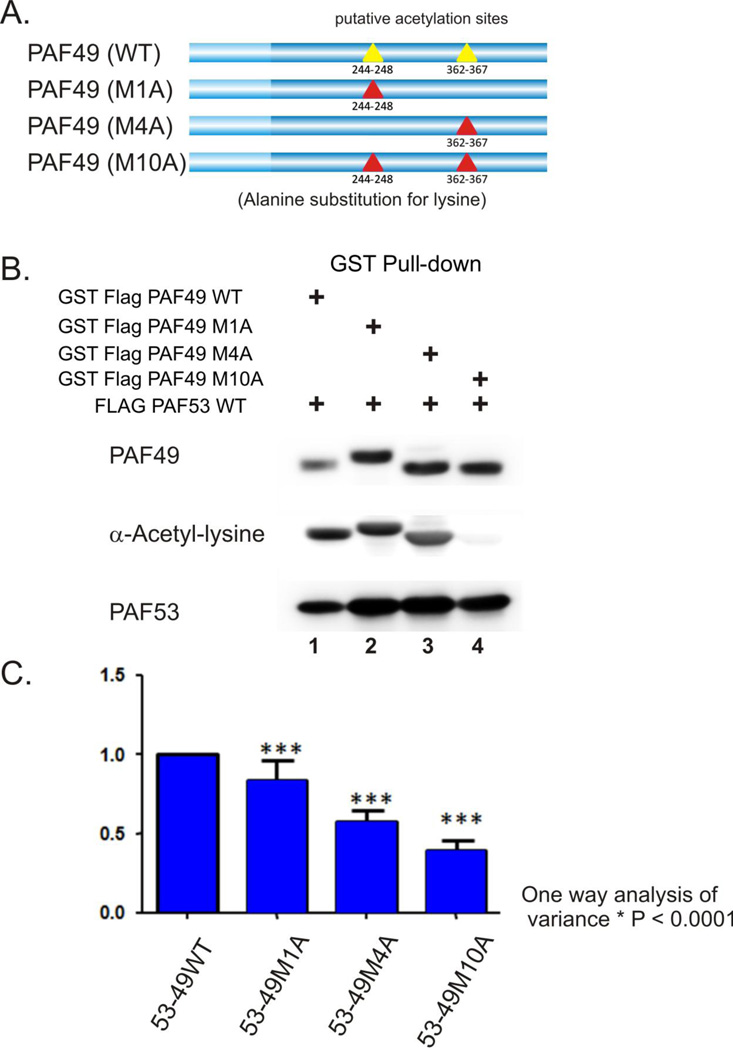

Using in silico analysis and mutagenesis (truncation and site-specific mutants) of PAF49 we have identified two putative sites of lysine acetylation that account for approximately 70% of PAF49 acetylation (Figure 6A, yellow triangles). 293T cells were cotransfected with the indicated acetylation site mutant of PAF49, GST-tagged, and FLAG-PAF53. The PAF49 proteins were then purified from crude lysates by GST pull-down and the pull-down products analyzed by SDS-PAGE and western blotting. Mutation of the lysine residues in the indicated sites to either alanine or arginine reduced (Figure 6, panels B and C), but did not completely inhibit the acetylation of PAF49, suggesting that there is at least one more site of acetylation.

Figure 6.

The PAF49 acetylation state does not affect the interaction with PAF53. A. In silico analysis and mutagenesis identified two sites of PAF49 that were likely acetylation sites. B. The lysines in those two sites were mutated to alanine and then the effects of site-specific mutagenesis on the acetylation of PAF49 was determined following cotransfection with pcDNA3.1-PAF53. Western blots for PAF49 and PAF53 demonstrated that the mutants associated with PAF53 and blots with anti-acetyl-lysine demonstrated the effect of mutagenesis on acetylation. C. Analysis of the effects of site specific mutagenesis on the acetylation of ectopically expressed PAF49. The experiments were quantified by dividing the ECL signal for the anti-acetyl-lysine blot by the ECL signal for the anti-FLAG signal for the individual PAF49 constructs. The results of each experiment was normalized to the wild-type signal. The results of 3–5 experiments were used to calculate mean values and SD. The significance of the results were examined by a one way analysis of variance.

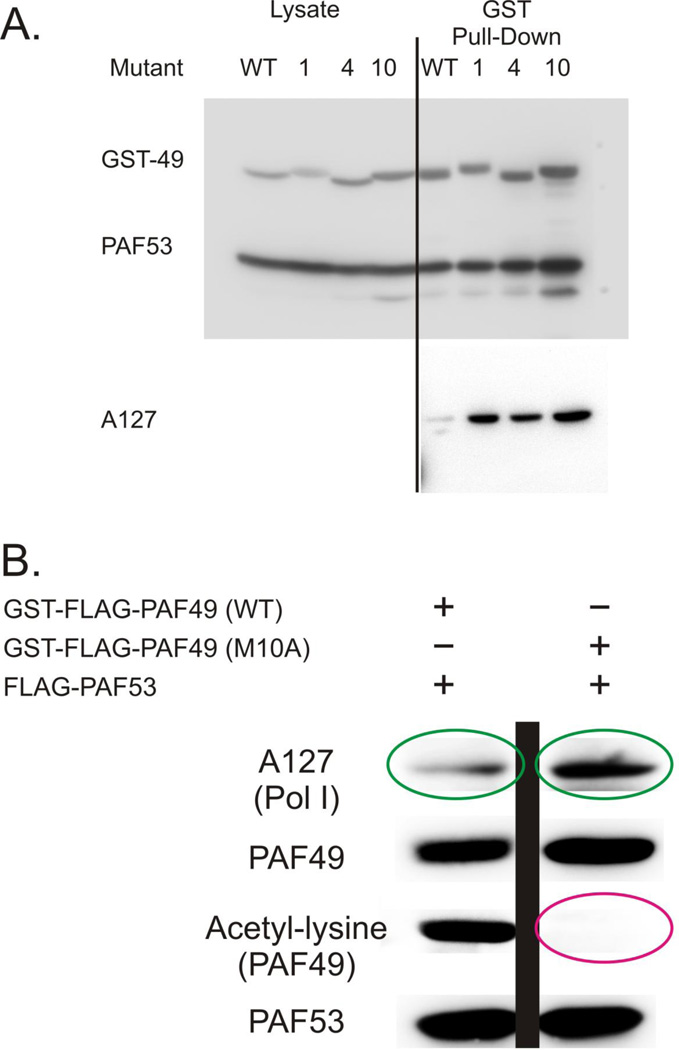

We then asked if the state of acetylation affected the binding of PAF49 to PAF53. As shown in Figure 6B and 7A, we did not observe a significant difference in the binding of PAF53 to the various acetylation site mutants of PAF49. When the blot in the top panel of Figure 7 was assayed for the ability of the transfected proteins to interact with endogenous Pol I, we noted a striking increase in the amount of Pol I that copurified with the acetylation site mutants compared to that which copurified with wild-type PAF49/PAF53 (Compare the amount of A127 in lane 1 of the lower panel with the amounts of A127 in lanes 2–4). This result is illustrated in Figure 7B., where the acetylation state of the PAF49 was assessed as well. The PAF53/PAF49 complex containing hypoacetylated PAF49 appear to demonstrate a greater affinity than wild type protein for endogenous Pol I.

Figure 7.

Coimmunoprecipitation demonstrates that Pol I binds more effectively to hypoacetylated PAF49 than acetylated PAF49. 293 cells were transfected with vectors driving the expression of PAF53 and the indicated wild-type and mutant forms of GST-PAF49. Forty-eight hours post transfection, PAF49 was purified by GSH pull-down and the bound proteins analyzed by SDS-PAGE and western blots. The coimmunoprecipitation of RNA polymerase I was determined with an anti-A127 antibodies (37).

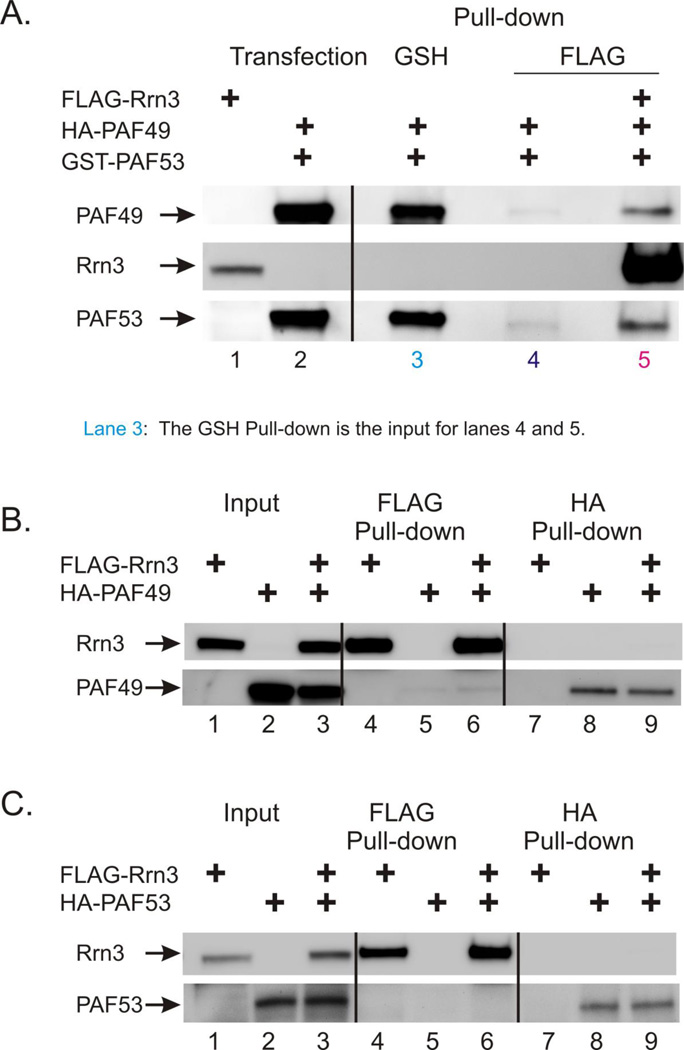

Genetic studies have led to the model of "a dual role of the Rpa49-Rpa34 dimer during the recruitment of Rrn3 and its subsequent dissociation from the elongating polymerase." (2). As crystallography models for Pol I do not include Rrn3, there is little or no structural evidence for this interaction. However, a recently proposed structure does provide for this possibility (42). As the yeast and mammalian proteins appear to share many biochemical properties (12, 15, 35), we investigated the possibility of a direct interaction between the mammalian heterodimer and Rrn3. In the first series of experiments, ectopically expressed FLAG-Rrn3 was purified by FLAG-affinity chromatography from extracts of 293T cells. Ectopically expressed PAF49 and PAF53 were purified as a heterodimer (GSH) by GSH affinity chromatography, and incubated with the immobilized Rrn3. As shown in Figure 8, panel A., GSH purified heterodimer (lane 3) bound to immobilized Rrn3 (lane 5), but not to FLAG beads alone (lane 4). These experiments provided evidence that the heterodimer could interact with Rrn3. In the next series of experiments, we sought to determine if either PAF49 or PAF53 individually would bind to Rrn3. We found that when either PAF49 (Figure 8, panel B.) or PAF53 (Figure 8, panel C.) were coexpressed individually with Rrn3, neither protein bound to Rrn3 (lanes 6 and 9 in both Figure 8, panels B and C.). These experiments suggest that the formation of the heterodimer does more than regulate the interaction of PAF53/49 with Pol I, but that the heterodimer can interact with Rrn3 as well and may stabilize the interaction of Rrn3 with Pol I.

Figure 8.

Rrn3 binds to the PAF49/PAF53 heterodimer (A), but not to either PAF53 or PAF49 alone (B and C). A. Ectopically expressed Rrn3 was purified by FLAG-affinity chromatography from extracts of 293T cells. Ectopically expressed PAF49 and PAF53 were purified as a heterodimer (GSH) by GSH affinity chromatography, and incubated with the immobilized Rrn3 (lane 5) or blank anti-FLAG resin (lane 4). The bound proteins were analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. B. and C. Cells were transfected with vectors driving the expression of tagged versions of Rrn3, PAF49 and PAF53 as indicated. Cell lysates were then fractionated using either immobilized anti-HA or immobilized anti-FLAG antibodies and the proteins that bound to the different matrices were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and western blots as described in Materials and Methods.

4. Conclusions

Our experiments provide a new basis for the regulation of rDNA transcription. Our results demonstrate that the association of the PF49/PAF53 heterodimer with mammalian RNA polymerase I is subject to regulation. Moreover, our results suggest that the acetylation state of PAF49 may be responsible, at least in part, for the regulation of the association of the heterodimer with core Pol I. As the yeast homologue of the heterodimer, A34/A49, has been demonstrated to affect elongation, our results are consistent with the possibility that the association/dissociation of the mammalian heterodimer may also affect elongation by Pol I. Moreover, the demonstration of a direct interaction between the heterodimer and Rrn3 provides a biochemical rationale for the genetic experiments of Beckouet et al. (2) who demonstrated that the A49/A34.5 heterodimer is important for the association and dissociation of Rrn3 with Pol I.

Highlights.

The association of the heterodimer of PAF53 and PAF49 with RNA Pol I is regulated

PAF49 is acetylated

The acetylation state of PAF49 affects the binding of the heterodimer to Pol I

Heterodimers containing hypoacetylated PAF49 are more stably associated with Pol I

The heterodimer interacts with Rrn3

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by GM069841 and HL077814 awarded to LIR, The Stephenson Cancer Center, and funds from the University of Oklahoma.

Abbreviations

- pol I

RNA polymerase I

- rRNA

ribosomal RNA

- A127

β subunit of RNA polymerase I

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- PAF49

polymerase associated factor 49 kDa

- PAF53

polymerase associated factor 53kDa

- a43 or rpa43

mouse homologue of yrpa43, the 43 kDa subunit of RNA polymerase I

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References Cited

- 1.Liljelund P, Mariotte S, Buhler JM, Sentenac A. Characterization and mutagenesis of the gene encoding the A49 subunit of RNA polymerase A in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89:9302–9305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.9302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beckouet F, Labarre-Mariotte S, Albert B, Imazawa Y, Werner M, Gadal O, et al. Two RNA polymerase I subunits control the binding and release of Rrn3 during transcription. Molecular and cellular biology. 2008;28:1596–1605. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01464-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schultz J, Caspersson T. Nucleic acids in Drosophila eggs, and Y-chromosome effects. Nature. 1948;162:66. doi: 10.1038/163066b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brachet J. Chemical embryology. New York: Interscience Publishers; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schaechter M, Maaloe O, Kjeldgaard NO. Dependency on medium and temperature of cell size and chemical composition during balanced grown of Salmonella typhimurium. J Gen Microbiol. 1958;19:592–606. doi: 10.1099/00221287-19-3-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker H, Stanners CP, Kudlow JE. Control of macromolecular synthesis in proliferating and resting Syrian hamster cells in monolayer culture. II. Ribosome complement in resting and early G1 cells. J Cell Physiol. 1971;77:43–50. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040770106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grummt I. Life on a planet of its own: regulation of RNA polymerase I transcription in the nucleolus. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1691–1702. doi: 10.1101/gad.1098503R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moss T, Langlois F, Gagnon-Kugler T, Stefanovsky V. A housekeeper with power of attorney: the rRNA genes in ribosome biogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:29–49. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6278-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hannan KM, Hannan RD, Rothblum LI. Transcription by RNA polymerase I. Frontiers in bioscience : a journal and virtual library. 1998;3:d376–d398. doi: 10.2741/a282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huet J, Buhler JM, Sentenac A, Fromageot P. Dissociation of two polypeptide chains from yeast RNA polymerase A. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1975;72:3034–3038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.8.3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gadal O, Mariotte-Labarre S, Chedin S, Quemeneur E, Carles C, Sentenac A, et al. A34.5, a nonessential component of yeast RNA polymerase I, cooperates with subunit A14 and DNA topoisomerase I to produce a functional rRNA synthesis machine. Molecular and cellular biology. 1997;17:1787–1795. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanada K, Song CZ, Yamamoto K, Yano K, Maeda Y, Yamaguchi K, et al. RNA polymerase I associated factor 53 binds to the nucleolar transcription factor UBF and functions in specific rDNA transcription. The EMBO journal. 1996;15:2217–2226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seither P, Zatsepina O, Hoffmann M, Grummt I. Constitutive and strong association of PAF53 with RNA polymerase I. Chromosoma. 1997;106:216–225. doi: 10.1007/s004120050242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hannan KM, Rothblum LI, Jefferson LS. Regulation of ribosomal DNA transcription by insulin. The American journal of physiology. 1998;275:C130–C138. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.1.C130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamamoto K, Yamamoto M, Hanada K, Nogi Y, Matsuyama T, Muramatsu M. Multiple protein-protein interactions by RNA polymerase I-associated factor PAF49 and role of PAF49 in rRNA transcription. Molecular and cellular biology. 2004;24:6338–6349. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.14.6338-6349.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuhn CD, Geiger SR, Baumli S, Gartmann M, Gerber J, Jennebach S, et al. Functional architecture of RNA polymerase I. Cell. 2007;131:1260–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carter R, Drouin G. The increase in the number of subunits in eukaryotic RNA polymerase III relative to RNA polymerase II is due to the permanent recruitment of general transcription factors. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:1035–1043. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geiger SR, Lorenzen K, Schreieck A, Hanecker P, Kostrewa D, Heck AJ, et al. RNA polymerase I contains a TFIIF-related DNA-binding subcomplex. Molecular cell. 2010;39:583–594. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albert B, Leger-Silvestre I, Normand C, Ostermaier MK, Perez-Fernandez J, Panov KI, et al. RNA polymerase I-specific subunits promote polymerase clustering to enhance the rRNA gene transcription cycle. The Journal of cell biology. 2011;192:277–293. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panov KI, Friedrich JK, Russell J, Zomerdijk JC. UBF activates RNA polymerase I transcription by stimulating promoter escape. EMBO J. 2006;25:3310–3322. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panov KI, Panova TB, Gadal O, Nishiyama K, Saito T, Russell J, et al. RNA polymerase I-specific subunit CAST/hPAF49 has a role in the activation of transcription by upstream binding factor. Molecular and cellular biology. 2006;26:5436–5448. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00230-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milkereit P, Tschochner H. A specialized form of RNA polymerase I, essential for initiation and growth-dependent regulation of rRNA synthesis, is disrupted during transcription. The EMBO Journal. 1998;17:3692–3703. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.13.3692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller G, Panov KI, Friedrich JK, Trinkle-Mulcahy L, Lamond AI, Zomerdijk JC. hRRN3 is essential in the SL1-mediated recruitment of RNA Polymerase I to rRNA gene promoters. EMBO J. 2001;20:1373–1382. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moorefield B, Greene EA, Reeder RH. RNA polymerase I transcription factor Rrn3 is functionally conserved between yeast and human. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:4724–4729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080063997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bodem J, Dobreva G, Hoffmann-Rohrer U, Iben S, Zentgraf H, Delius H, et al. TIF-IA, the factor mediating growth-dependent control of ribosomal RNA synthesis, is the mammalian homolog of yeast Rrn3p. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:171–175. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peyroche G, Milkereit P, Bischler N, Tschochner H, Schultz P, Sentenac A, et al. The recruitment of RNA polymerase I on rDNA is mediated by the interaction of the A43 subunit with Rrn3. The EMBO journal. 2000;19:5473–5482. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.20.5473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cavanaugh AH, Hirschler-Laszkiewicz I, Hu Q, Dundr M, Smink T, Misteli T, et al. Rrn3 phosphorylation is a regulatory checkpoint for ribosome biogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27423–27432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201232200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choudhary C, Kumar C, Gnad F, Nielsen ML, Rehman M, Walther TC, et al. Lysine acetylation targets protein complexes and co-regulates major cellular functions. Science. 2009;325:834–840. doi: 10.1126/science.1175371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen S, Seiler J, Santiago-Reichelt M, Felbel K, Grummt I, Voit R. Repression of RNA polymerase I upon stress is caused by inhibition of RNA-dependent deacetylation of PAF53 by SIRT7. Molecular cell. 2013;52:303–313. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ford E, Voit R, Liszt G, Magin C, Grummt I, Guarente L. Mammalian Sir2 homolog SIRT7 is an activator of RNA polymerase I transcription. Genes & development. 2006;20:1075–1080. doi: 10.1101/gad.1399706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hannan KM, Rothblum LI, Jefferson LS. Regulation of ribosomal DNA transcription by insulin. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:C130–C138. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.1.C130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stefanovsky VY, Pelletier G, Hannan R, Gagnon-Kugler T, Rothblum LI, Moss T. An immediate response of ribosomal transcription to growth factor stimulation in mammals is mediated by ERK phosphorylation of UBF. Mol Cell. 2001;8:1063–1073. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Green MR, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning : a laboratory manual. 4th ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mortensen R, Chesnut JD, Hoeffler JP, Kingston RE. Selection of transfected mammalian cells. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2003;Chapter 9(Unit 9):5. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb0905s62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Penrod Y, Rothblum K, Rothblum LI. Characterization of the interactions of mammalian RNA polymerase I associated proteins PAF53 and PAF49. Biochemistry. 2012;51:6519–6526. doi: 10.1021/bi300408q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hannan RD, Cavanaugh A, Hempel WM, Moss T, Rothblum L. Identification of a mammalian RNA polymerase I holoenzyme containing components of the DNA repair/replication system. Nucleic acids research. 1999;27:3720–3727. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.18.3720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hannan RD, Hempel WM, Cavanaugh A, Arino T, Dimitrov SI, Moss T, et al. Affinity purification of mammalian RNA polymerase I. Identification of an associated kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1257–1267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.2.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith SD, Oriahi E, Lowe D, Yang-Yen HF, O'Mahony D, Rose K, et al. Characterization of factors that direct transcription of rat ribosomal DNA. Molecular and cellular biology. 1990;10:3105–3116. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.6.3105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hannan RD, Luyken J, Rothblum LI. Regulation of ribosomal DNA transcription during contraction-induced hypertrophy of neonatal cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3213–3220. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.3213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Todaro GJ, Green H. Quantitative studies of the growth of mouse embryo cells in culture and their development into established lines. The Journal of cell biology. 1963;17:299–313. doi: 10.1083/jcb.17.2.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hirschler-Laszkiewicz I, Cavanaugh A, Hu Q, Catania J, Avantaggiati ML, Rothblum LI. The role of acetylation in rDNA transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:4114–4124. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.20.4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vannini A, Cramer P. Conservation between the RNA polymerase I, II, and III transcription initiation machineries. Molecular cell. 2012;45:439–446. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]