Abstract

Background

Few studies have characterized longer-term outcomes after retropubic and transobturator midurethral slings.

Methods

Women completing 2-year participation in a randomized equivalence trial who had not received surgical retreatment for stress urinary incontinence were invited to participate in a 5-year observational cohort. The primary outcome, treatment success, was defined as no retreatment or self-reported stress incontinence symptoms. Secondary outcomes included urinary symptoms and quality of life, satisfaction, sexual function and adverse events.

Results

404 of 597 (68%) women from the original trial enrolled. Five-years after surgical treatment, success was 7.9% greater in women assigned to retropubic-sling compared to transobturator-sling (51.3% vs 43.4%, 95% CI −1.4%, 17.2%) not meeting pre-specified criteria for equivalence. Satisfaction decreased over 5-years, but remained high and similar between arms (79%, retropubic-sling vs 85%, transobturator-sling groups, p=0.15). Urinary symptoms and quality of life worsened over time (p<0.001), and women with retropubic-sling reported greater urinary urgency (P=0.001), more negative quality of life impact (p=0.02), and worse sexual function (P=0.001). There was no difference in proportion of women experiencing at least 1 adverse event (p=0.17). Seven new mesh erosions were noted (retropubic-sling-3, transobturator-sling-4).

Conclusion

Treatment success declined over 5-years for retropubic and transobturator-slings and did not meet pre-specified criteria for equivalence with retropubic demonstrating a slight benefit. However, satisfaction remained high in both arms. Women undergoing transobturator-sling reported more sustained improvement in urinary symptoms and sexual function. New mesh erosions occurred in both arms over time, although at a similarly low rate.

Introduction

Midurethral slings (MUS) are the most commonly performed surgeries for women with stress urinary incontinence. (SUI). Approximately 200,000 SUI surgeries are performed annually 1,2 in the United States, increasing 27% from 2000 to 2009. Most of this increase is attributed to sling procedures 3. Insufficient information is available regarding long-term success and safety of MUS procedures, as most previous clinical trials reported outcomes only at 1-2 years and did not include physical examinations in follow-up.

Failure rates increase over time for most SUI procedures 4,5. Whether this is due to surgical failure or natural history of incontinence with aging is unclear. Complications of SUI surgery, including urgency urinary incontinence, urinary tract infections and mesh-related problems may have long-term impact on patient satisfaction and quality of life (QOL). The Federal Drug Administration issued warnings about utilization of mesh for prolapse and SUI surgery due to lack of information regarding longer-term outcomes. Mesh-related complications can occur up to 5 years post-operatively 5,6. Few prospective studies report long-term outcomes after MUS in a comparative fashion using validated symptom and QOL questionnaires and physical examination, which is essential for evaluating mesh complications5,7-9. Even fewer randomized trials compare continence outcomes and mesh complications between retropubic and transobturator-slings with follow up longer than 2-years 10.

We previously reported 1 and 2-year outcomes of randomized equivalence clinical trial of retropubic and transobturator-MUS in women with SUI 11,12. We report 5-year outcomes, including treatment success, satisfaction, urinary symptoms, QOL, and adverse events in women who completed Trial of Mid-urethral Slings (TOMUS) and enrolled in this observational cohort study.

Methods

Study Design

Details of design and 1-year (primary outcome) and 2-year outcomes of the randomized equivalence trial of retropubic and transobturator-MUS are published (NCT00325039) 11,12. Women completing trial, not surgically retreated for SUI, were invited to participate in observational study to assess 5-year treatment success, satisfaction, symptom-specific distress, QOL, and adverse events of MUS. Institutional review boards at each participating institution approved observational follow-up study protocol. Participants provided written consent for participation in follow-up.

Outcomes

Primary outcome, treatment success, was defined as no re-treatment for SUI (behavioral, pharmacological, pessary or surgical) and no self-reported SUI symptoms on Medical, Epidemiological and Social Aspects of Aging questionnaire(MESA) 13. An answer of ‘never’ or ‘rarely” to all stress-specific questions was considered negative symptoms. Secondary outcomes included the Urogenital Distress Inventory14 and Incontinence Impact Questionnaire 14. Women also completed Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Function Questionnaire 15 to assess sexual function; Patient Global Impression of Improvement 16to assess overall improvement; and one-item satisfaction question, “How satisfied or dissatisfied are you with results of bladder surgery related to urine leakage”. Possible responses were completely satisfied, mostly satisfied, neutral, mostly dissatisfied and completely dissatisfied. Completely and mostly satisfied were reported as “satisfied” and neutral, mostly dissatisfied and completely dissatisfied as “not satisfied”.

Pelvic examinations were performed at annual visits to assess for visual and palpable evidence of mesh exposure and associate patient symptoms with physical findings. Prolapse was assessed using Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification system 17. Participants who were not seen in-person could mail completed questionnaires.

Adverse events were defined as deviation from normal postoperative follow-up, and severity grade determined with modified Clavien-Dindo classification, which is based on level of therapy required to treat an event 18. Non-serious adverse events (Grades I and II) did not require surgical, endoscopic or radiological intervention. Serious adverse events required such intervention (Grade III), were life threatening (Grade IV), or resulted in death (Grade V). The following adverse events were collected during cohort study: mesh exposure (mesh visualized in the vagina), mesh erosion (mesh erosion after primary healing into a nearby organ), vesical and urethral-vaginal fistulas and recurrent urinary tract infections defined as >3 in 1-year.

Statistical Analysis

TOMUS had 80% power to show equivalence between the two procedures at 1-year with equivalence margins of ±12 percentage points at 5% significance level.11 We projected an initial enrollment in cohort study of 400 women with 90% (n=360) completing one or more of the follow-up visits and 70% (n=280) completing each visit. This sample size provides 80% power to show equivalence at 5 years post-surgery with equivalence margins of ±15 percentage points at 5% significance level. Determination of equivalence requires the entire 95% confidence interval for the difference between the two slings to be within the equivalence margin. Rates of treatment success and their standard errors rates were obtained using Kaplan Meier (KM) time-to-event analysis. For this analysis, we included all women randomized and treated per-protocol in the equivalence trial since retreatment was a treatment failure and exclusion criterion for observational study. Those who did not enroll in cohort study were censored at the last trial visit at which their outcome was assessed. To minimize bias toward determining equivalence, data from women who were treated per protocol (i.e., were eligible and received the assigned surgery) were included in the primary analysis 19. The difference between groups was calculated using cumulative success rates from KM analysis. Confidence intervals of differences were calculated using standard errors from KM analysis, assuming independent groups and normal approximation to binomial distribution. Sensitivity analyses were performed in which different assumptions about outcomes of women who were lost to follow-up were used. Fisher's exact test was used to compare the proportions of women in each group who had one or more adverse events.

Analysis of the secondary outcomes was performed including only observational study sample. Continuous outcomes were analyzed with use of least squares modeling methods. Repeated measures modeling was used to assess changes over time post-surgery by sling group controlling for baseline level of measures. Analyses were performed using SAS statistical software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute).

Results

Study Population

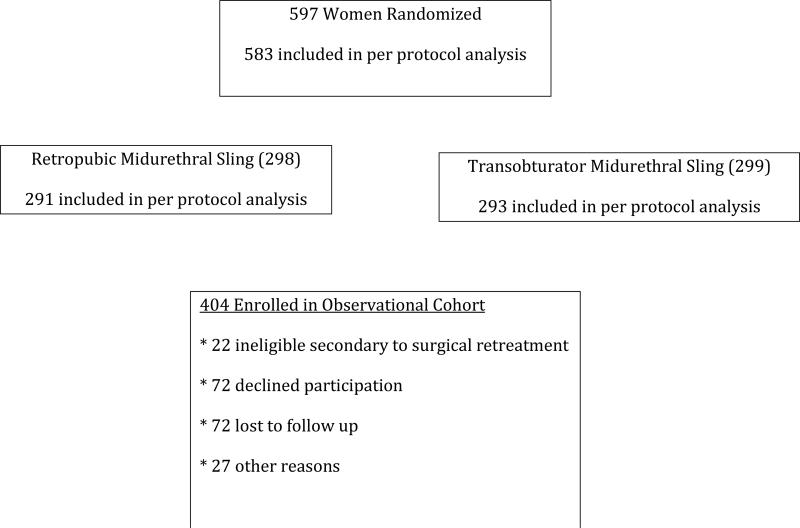

Four hundred four of 597 (67.7%) women from the original randomized trial enrolled in observational follow-up. Twenty-two (3.7%) were ineligible because of surgical retreatment for SUI; 72 (12.1%) declined participation; 72 (12.1%) were lost to follow-up; and 27 (4.5%) were not enrolled for other reasons (Figure 1). Women who enrolled were older (53.7±10.5 versus 51.2±11.8, P=0.02) and more likely to be postmenopausal (33.4% versus 18.8%, p=0.0009). Baseline clinical and demographic characteristics at entry into randomized trial were similar in both surgery groups (Table1).

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Women Enrolled and Not Enrolled in Observational Cohort Study

| Characteristics | Enrolled (N=404) | Not Enrolled (N=193) | p-Value1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | |||

| Age (years): Mean±SD | 53.7 (± 10.48) | 51.2 (± 11.83) | 0.02 |

| Racial and Ethnicity Group N (%) | 0.59 | ||

| Hispanic | 42 (10.4%) | 29 (15.0%) | 0.28 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 328 (81.2%) | 145 (75.1%) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 12 (3.0%) | 5 (2.6%) | |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 22 (5.4%) | 14 (7.3%) | |

| Married/Living as Married N (%) | 285 (70.5%) | 127 (65.8%) | 0.26 |

| Education n (%) | 0.30 | ||

| High School or Less | 120 (29.7%) | 64 (33.2%) | |

| Post High School | 143 (35.4%) | 74 (38.3%) | |

| Bachelors or more | 141 (34.9%) | 55 (28.5%) | |

| Risk Factors for Urinary Incontinence | |||

| BMI: Mean±SD | 30.3 (± 6.59) | 30.3 (± 7.03) | 0.94 |

| Vaginal Nulliparous N (%) | 46 (11.4%) | 24 (12.4%) | 0.67 |

| Prior Incontinence Surgery N (%) | 54 (13.4%) | 25 (13.1%) | > 0.99 |

| Menopausal Status N (%) | 0.80 | ||

| Premenopausal | 154 (38.1%) | 90 (47.1%) | 0.0009 |

| Postmenopausal not using HRT | 135 (33.4%) | 36 (18.8%) | |

| Postmenopausal using HRT | 115 (28.5%) | 65 (34.0%) | |

| Concomitant Surgery N (%) | 105 (26.0%) | 46 (23.8%) | 0.62 |

| Leaks/day: Median (10th, 90th %) | 2.7 (0.67, 6.67) | 2.7 (0.67, 6.67) | 0.89 |

| Pad test: Median (10th, 90th %) | 12.1 (3.39, 92.85) | 13.4 (4.13, 78.64) | 0.60 |

| Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification Stage N (%) | |||

| Stage 0/I | 178 (44.1%) | 89 (46.1%) | 0.74 |

| Stage II | 195 (48.3%) | 87 (45.1%) | |

| Stage III/IV | 31 (7.7%) | 17 (8.8%) | |

| Quality of Life | |||

| Urinary Distress Inventory Mean±SD | 134.8 (± 44.11) | 134.0 (± 48.36) | 0.85 |

| Incontinence Impact Questionnaire Mean±SD | 147.3 (± 96.02) | 160.3 (± 99.77) | 0.13 |

| MESA Stress Index Mean±SD | 71.7 (± 16.84) | 71.3 (± 17.51) | 0.81 |

| MESA Urge Index Mean±SD | 35.5 (± 21.97) | 33.2 (± 22.22) | 0.21 |

p-values for continuous variables were based on t-tests; p-values for categorical variables were based on Fisher's Exact Test

Outcomes

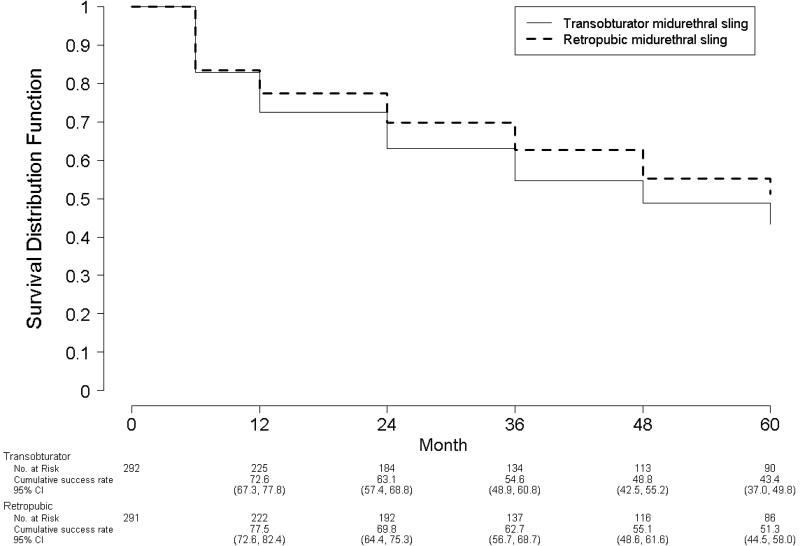

To obtain accurate estimates of long-term treatment success, all women randomized in the original trial, who received the study surgery per-protocol (N=583) were included in KM analysis (Figure 2). As seen in primary equivalence outcome, retropubic had a slightly better treatment success over time (Log rank test p=0.09).

Figure 2.

TreatmentSuccess Rates Over Time for Women Randomized to Retropubic and Transobturator Midurethral Sling (N=583)

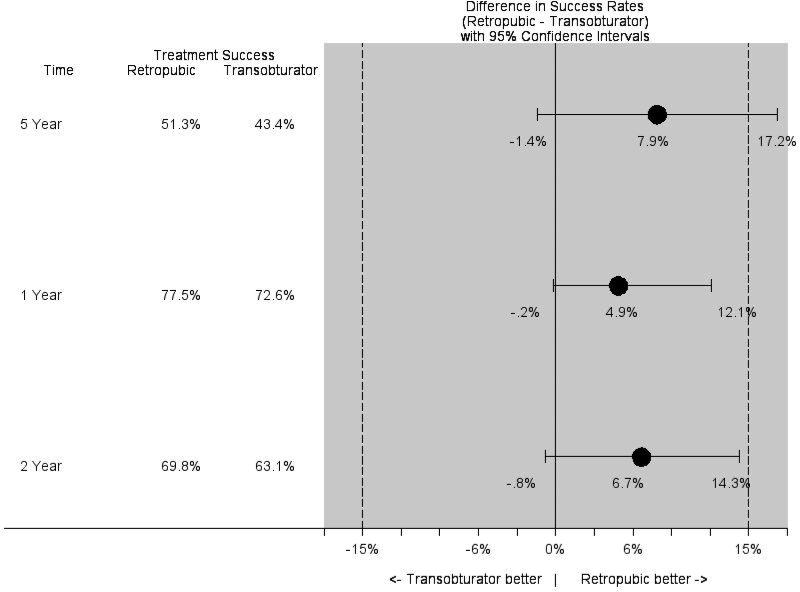

Five-years after surgery, treatment success was 7.9% greater after retropubic compared to transobturator (51.3% versus 43.4%, 95% CI -1.4, 17.2) and did not meet pre-specified criteria for equivalence of 12% at the original trial or 15% in current study (Figure 3). However, confidence intervals included 0%, indicating that success rates also cannot be considered different from one another. Treatment failures were primarily due to SUI symptoms only (N=220); others were due to SUI symptoms and surgical retreatment (N=37); and a single failure was attributed exclusively to surgical re-treatment. We also re-estimated the 1 and 2-year treatment success rates and equivalence margins of the clinical trial using our definition of treatment success from cohort study and compared those rates to treatment success rates at 5-years. (Figure 2). Recalculated 1 and 2-year treatment success rates are similar to originally reported subjective and objective success rates at 2-years12.

Figure 3.

Treatment Success and 95% confidence intervals for Retropubic and Transobturator Midurethral Slings at 1, 2, and 5-years after Surgery

To assess sensitivity of our results to loss to follow-up, we computed several analyses using different assumptions about experiences of those not followed for 5-years (Table 2). Only the most extreme assumptions in favor of retropubic sling result in a confidence interval that indicates superiority of the retropubic procedure. When all women who were lost to follow-up are assumed to be incontinent, the difference between groups is -0.9 (95% CI -8.0 to 6.1) and confidence interval lies within the equivalence bounds. In this case, the hypothesis of non-equivalence would be rejected. For most cases, the confidence intervals cross the equivalence bounds and results remain inconclusive.

Table 2.

Overall Treatment Success by Sling Treatment Group at 5 year Visit (n=583)

| Retropubic | Transobturator | Difference | 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | % | %,% | |

| Kaplan Meier Estimates | 51.3% | 43.4% | 7.9% | −1.4%, 17.2% | ||

| Complete Cases 1 | ||||||

| (n=189) | (n=217) | |||||

| 72 | 38.1% | 75 | 34.6% | 3.5% | −5.9%, 12.9% | |

| Sensitivity Analyses 2 | ||||||

| (n=291) | (n=292) | |||||

| All treatments: Lost = success | 174 | 59.8% | 150 | 51.4% | 8.4% | 0.4%, 16.5% |

| All treatments: Lost = failure | 72 | 24.7% | 75 | 25.7% | −0.9% | −8.0%, 6.1% |

| Retropubic: lost = success; Transobturator: lost = failure | 174 | 59.8% | 75 | 25.7% | 31.4% | 26.6%, 41.7% |

| Retropubic: lost = failure; transobturator, lost = success | 72 | 24.7% | 150 | 51.4% | −26.6% | 34.2%, −19.1% |

Notes

Complete cases analysis, observational cohort failure status at 5-years is known. Those who did not consent or were lost to follow-up before completing the 5-year visit were excluded.

Sensitivity analysis – different assumptions about status of those who did not consent to observational cohort or were lost to follow-up.

Mean symptom distress and impact scores at baseline, 6-month and 5-years after surgery for the 404 women in observational cohort by treatment group are shown in Table 3. Urinary and sexual function measures improved after surgery, but there was a significant increase of these symptoms over time in both groups (though still improved compared to baseline). SUI symptoms as measured by MESA and Urogenital Distress Inventory measures pooled over all visits did not differ between treatment groups (P=0.62 and P=0.08, respectively). However, urgency incontinence symptoms as measured by MESA were higher in retropubic compared to transobturator-MUS group (P=0.001). For incontinence impact on QOL, trend over time differed significantly between groups (p=0.02), with retropubic having greater negative impact. Pattern of changes in incontinence impact from visit to visit differed between groups. Among 271 women who reported they were sexually active after surgery, mean sexual function scores were lower (worse function) in the retropubic compared to transobturator group when pooled over post-surgery visits (P=0.001).

Table 3.

Baseline, 6 Month, and 5-Year Symptom Outcomes for 404 Women in Observational Cohort

| Baseline | 6-month | 1-year | 2-year | 3-year | 4-year | 5-year | *P | **P | ***P (Trend) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MESA Stress Index Mean (SD) | <0.001 | 0.62 | 0.08 | |||||||

| RMUS (N=201) | 72(0.4) | 6.3 (1.2) | 7.6(1.2) | 8.6(1.2) | 11.6(1.2) | 12.9(1.2) | 13 (1.6) | |||

| TMUS (N=203) | 72 (0.5) | 5.9 (1.2) | 6.9(1.1) | 9.3(1.1) | 9.7(1.2) | 10.2(1.2) | 14(1.6) | |||

| MESA Urge Index Mean±SD | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.58 | |||||||

| RMUS (N=201) | 33.1(0.6) | 11.2 (1) | 10.9 (1) | 12.8(1.) | 14.3(1) | 14.3(1) | 16.8(1.6) | |||

| TMUS (N=203) | 37.4(0.6) | 6.8 (1) | 8.1 (1) | 10.1 (1) | 10.6 (1) | 12(1.1) | 12.2(1.5) | |||

| UDI Total Mean±SD | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.57 | |||||||

| RMUS (N=201) | 132(46) | 21(2.5) | 22.6(2.5) | 28.7(2.5) | 32.6(2.5) | 37(2.6) | 43.3(2.7) | |||

| TMUS (N=203) | 138(42) | 18.7(2.5) | 20.7(2.5) | 25.9(2.5) | 26.9(2.5) | 31.6(2.6) | 33.5(2.7) | |||

| IIQ Total Mean±SD | 0.02 | |||||||||

| RMUS (N=201) | 144(96.1) | 18.4(3.5) | 17(3.4) | 14.9(3.5) | 24.7(3.5) | 29.4(3.6) | 38.8(3.9) | |||

| TMUS (N=203) | 150(96) | 14.5(3.5) | 14(3.4) | 23.5(3.4) | 19.6(3.5) | 22.7(3.6) | 26.5(3.8) | |||

| PISQ Mean±SD (N=271) | 37.7±0.4 | 38.3±0.4 | 35.4±0.5 | 37.8±0.5 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.14 | |||

| RMUS | 33.8(0.2) | 37.7(0.4) | 37(0.4) | 36.7(0.4) | 35.8(0.4) | 35.9(0.4) | 35.4(0.5) | |||

| TMUS | 32.4(0.2) | 38.3(0.4) | 37.8(0.4) | 37.9(0.4) | 37.6(0.4) | 37(0.4) | 37.8(0.5) |

P-value for hypothesis of no change over time (6 months to 5-years)

P-value for null hypothesis of no overall difference between groups 6 months to 5-years

Test of null hypothesis for the interaction of treatment group and time (trend) p = 0.02.

MESA, Medical, Epidemiologic and Social Aspects of Aging Questionnaire; UDI, Urogenital Distress Inventory; IIQ, Incontinence Impact questionnaire; PISQ, Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Incontinence Sexual Function questionnaire

Proportion of women who stated they were ‘very much better’ or ‘much better’ by patient global impression of improvement declined over-time in both groups (P<0.0001); however, a greater proportion of women in the transobturator group reported they were ‘very much better’ or ‘much better’ at 5-years (88% versus 77%, P=0.01). Women in the transobturator group were nearly twice as likely (OR=1.94, 95% CI 1.18-3.21) to report improvement in their urinary condition than those in the retropubic group. Although patient satisfaction decreased significantly over-time in both groups (retropubic: 93% to 79% and transobturator 92% to 85%, P<0.0001), there was no significant difference between groups at 5-years (P=0.15).

Adverse Events

During the observational cohort study, 40 women (10%) experienced 52 non-serious adverse events and 6 serious adverse events. There was no difference between groups in proportion of women who experienced at least 1 adverse event (12% in retropubic vs. 8% in transobturator,p=0.17). The 6 serious adverse events, which required surgical, radiological or endoscopic intervention (Grade III), included two mesh erosions (one in each group) and 4 recurrent urinary tract infections (all retropubic group). The 52 non-serious adverse events were primarily urinary tract infections (N=37) followed by mesh exposures (N=7) with remainder being pain, vaginal discharge, decreased bladder sensation and numbness.

Five of 52 non-serious adverse events were reported in clinical trial and were followed for 5-years, including two persistent mesh exposures (one in each group), two cases of continuing neurologic symptoms (transobturator), and one case of seroma. Overall, there were 7 new mesh exposures in years 3-5 after surgery (3 in retropubic and 4 in transobturator, p=0.71). Forty-one recurrent urinary tract infections were reported by 25 women (6%) - 17 (8%) in retropubic group and 8 (4%) in transobturator group, p=0.06.

Discussion

Women from a well-characterized, randomized equivalence surgical trial enrolled in a longitudinal observational cohort demonstrated decreasing continence success rates after retropubic and transobturator-MUS during the first 5-years after treatment. Treatment success was slightly higher after retropubic compared to transobturator-sling and did not meet our pre-specified criteria for equivalence; however, confidence intervals included 0%, indicating that success rates cannot be considered different from one another. Similar to our 2-year findings12, long-term treatment success after retropubic-MUS continued to be slightly higher than after transobturator, while urinary urgency incontinence, sexual function, and overall impression of improvement were better after transobturator-MUS.

Patient reported outcomes for QOL, sexual function, and global assessment of improvement also declined over time, but remained significantly improved than at baseline. While satisfaction declined after both procedures, it declined less than actual continence success rates, suggesting that satisfaction is influenced by other urogenital functional outcomes. Our satisfaction rates at 5-years are similar to the rates (83%) reported in a Cochrane Review comparing retropubic and transobturator-slings at one-year 20. Longer-term data are not included in the Cochrane Review demonstrating the marked importance of the current data.

Although treatment success rates were slightly higher after retropubic-sling, a greater proportion of women who underwent a transobturator-sling reported that their urinary status was “very much better” or “much better”. This perception of greater overall improvement despite more SUI symptoms may be explained by higher rates of urgency urinary incontinence and irritative symptoms in women after retropubic-sling and this essentially “equalized” the slight advantage of retropubic over transobturator-sling with respect to treatment success. In general, urinary symptoms and quality of life measures showed greater overall improvement after transobturator-sling suggesting that the trend towards favoring better treatment success in the retropubic group may come at the cost of quality of life and other symptom improvement. These findings are similar to those seen in extended follow up of the Stress Incontinence Surgical Treatment Efficacy Trial, a multicenter, randomized trial which compared Burch colposuspension to pubovaginal sling using autologous rectus fascia4. Fascial sling had slightly higher 5-year continence rates than the Burch but, similar to our current study, satisfaction trends over time did not differ significantly between the two treatments. Investigators reported that urgency urinary incontinence may contribute significantly to patients’ perceptions of satisfaction4,21. Clearly, there are other factors, including urgency incontinence, which contribute to satisfaction and perception of overall improvement and may partially explain the disparity between treatment success rates and improvement and satisfaction. More urgency incontinence or voiding symptoms may be the trade-off in longer term for higher treatment success in these procedures.

The large cohort with annual in-person pelvic examinations to assess mesh exposures is an important contribution. Although a few women developed new mesh exposures, numbers remain reassuringly small (1.7%). While new mesh exposures are not unacceptably high and comparable to rates seen with polypropylene abdominal sacrocolpopexy22, it illustrates ongoing risks of mesh erosion even 5-years from initial sling placement. Clearly mesh exposure is not limited to immediate postoperative period and this adverse effect should be a consideration remote from initial placement of mesh.

Early in the introduction of polypropylene slings, surgeons suggested the use of “permanent” mesh would result in more durable outcomes compared to procedures with autologous, donor allograft, and xenograft slings. Our data refutes that initial belief: just as with biological materials, permanent mesh slings show a progressive decline in efficacy over time.

Our results are robust due to well-defined surgical cohort, followed closely at multiple centers across the country, and assessed using standardized and validated measures, including annual physical examination to assess mesh complications. Limitations include a slightly lower retention rate (67%) compared to original trial; therefore mesh exposures may be slightly higher than reported, although our previous trial found a lower proportion of continent women entered extended follow-up, suggesting that adverse events may not be over-represented in the study population.4

Long-term treatment success and satisfaction with both retropubic and transobturator-MUS declines over time and mesh complications continue to rise at a low rate. Women undergoing transobturator-MUS reported more sustained improvement in urinary symptoms, QOL and sexual function despite slightly lower treatment success rates. These data are important for both physicians and patients as rates of MUS procedures continue to increase with some even suggesting slings be offered as a first line treatment for SUI 23.

Acknowledgements

STEERING COMMITTEE

E. Ann Gormley, Chair (Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH); Larry Sirls, MD, Salil Khandwala, MD (William Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak, MI and Oakwood Hospital, Dearborn, MI; U01 DK58231); Linda Brubaker, MD, Kimberly Kenton, MD (Loyola University Chicago, Stritch School of Medicine, Maywood, IL; U01 DK60379); Holly E. Richter, PhD, MD, L. Keith Lloyd, MD (University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL; U01 DK60380); Michael Albo, MD, Charles Nager, MD (University of California, San Diego, CA; U01 DK60401); Toby C. Chai, MD, Harry W. Johnson, MD (University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD; U01 DK60397); Halina M. Zyczynski, MD, Wendy Leng, MD (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA; U01 DK 58225); Philippe Zimmern, MD, Gary Lemack, MD (University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, TX; U01 DK60395); Stephen Kraus, MD, Amy Arisco, MD (University of Texas Health Sciences Center, San Antonio, TX; U01 DK58234); Peggy Norton, MD, Ingrid Nygaard, MD (University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT; U01 DK60393); Sharon Tennstedt, PhD, Anne Stoddard, ScD (New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA; U01 DK58229); Debuene Chang, MD (until 10/2009), John Kusek, PhD (starting 10/2009) (National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases).

CO-INVESTIGATORS

Jan Baker, APRN; Diane Borello-France, PT, PhD; Kathryn L. Burgio, PhD; Ananias Diokno, MD; MaryPat Fitzgerald, MD; Chiara Ghetti, MD; Patricia S. Goode, MD; Robert L. Holley, MD; Yvonne Hsu, MD; Jerry Lowder, MD; Emily Lukacz, MD; Alayne Markland, DO, MSc; Shawn Menefee, MD; Pamela Moalli, MD; Elizabeth Mueller, MD; Leslie Rickey, MD, MPH; Thomas Rozanski, MD; Elizabeth Sagan, MD; Joseph Schaffer, MD; Robert Starr, MD; Gary Sutkin, MD; R. Edward Varner, MD; Emily Whitcomb, MD.

STUDY COORDINATORS

Julie E. Burge, BS; Laura Burr, RN; JoAnn Columbo, BS, CCRC; Tamara Dickinson, RN, CURN, CCCN, BCIA-PMDB; Rosanna Dinh, RN, CCRC; Judy Gruss, RN; Alice Howell, RN, BSN, CCRC; Chaandini Jayachandran, MSc; Kathy Jesse, RN; Barbara Leemon, RN; Karen Mislanovich, RN; Caren Prather, RN; Mary Tulke, RN; Robin Willingham, RN, BSN; Kimberly Woodson, RN, MPH; Gisselle Zazueta-Damian.

DATA COORDINATING CENTER:

Kimberly J. Dandreo, MSc; Liyuan Huang, MS; Rose Kowalski, MA; Heather Litman, PhD; Marina Mihova, MHA; Chad Morin, BA; Anne Stoddard, ScD (Co-PI); Kerry Tanwar, MPH; Sharon Tennstedt, PhD (PI); Yan Xu, MS.

DATA SAFETY AND MONITORING BOARD

J. Quentin Clemens MD, (Chair) Northwestern University Medical School, Chicago IL; Paul Abrams MD, Bristol Urological Institute, Bristol UK; Deidre Bland MD, Blue Ridge Medical Associates, Winston Salem NC; Timothy B. Boone, MD, The Methodist Hospital, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX; John Connett PhD, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis MN; Dee Fenner MD, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor MI; William Henderson PhD, University of Colorado, Aurora CO; Sheryl Kelsey PhD, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh PA; Deborah J. Lightner, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN; Deborah Myers MD, Brown University School of Medicine, Providence RI; Bassem Wadie MBBCh, MSc, MD, Mansoura Urology and Nephrology Center, Mansoura, Egypt; J. Christian Winters, MD, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, LA

Footnotes

IRB approved at each participating clinical site.

Contributor Information

Kimberly Kenton, Northwestern University.

Anne M. Stoddard, New England Research Institutes.

Halina Zyczynski, University of Pittsburgh, Magee-Women's Research Institute.

Michael Albo, University of California San Diego.

Leslie Rickey, Yale University.

Peggy Norton, University of Utah.

Clifford Wai, University of Texas Southwestern.

Stephen R. Kraus, University of Texas Health Sciences Center San Antonio.

Larry T. Sirls, William Beaumont Hospital.

John W. Kusek, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Heather J. Litman, Boston Children's Hospital.

Robert P. Chang, New England Research Institute.

Holly E. Richter, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

References

- 1.Oliphant SS, Wang L, Bunker CH, et al. Trends in stress urinary incontinence inpatient procedures in the United States, 1979-2004. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2009;200:521, e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erekson EA, Lopes VV, Raker CA, et al. Ambulatory procedures for female pelvic floor disorders in the United States. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2010;203:497, e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anger JT, Weinberg AE, Albo ME, et al. Trends in surgical management of stress urinary incontinence among female Medicare beneficiaries. Urology. 2009;74:283–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brubaker L, Richter HE, Norton PA, et al. 5-year continence rates, satisfaction and adverse events of burch urethropexy and fascial sling surgery for urinary incontinence. The Journal of urology. 2012;187:1324–30. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.11.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward KL, Hilton P. Uk, Ireland TVTTG. Tension-free vaginal tape versus colposuspension for primary urodynamic stress incontinence: 5-year follow up. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2008;115:226–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsivian A, Mogutin B, Kessler O, et al. Tension-free vaginal tape procedure for the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence: long-term results. The Journal of urology. 2004;172:998–1000. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000135072.27734.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jelovsek JE, Barber MD, Karram MM, et al. Randomised trial of laparoscopic Burch colposuspension versus tension-free vaginal tape: long-term follow up. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2008;115:219–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01592.x. discussion 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ballester M, Bui C, Frobert JL, et al. Four-year functional results of the suburethral sling procedure for stress urinary incontinence: a French prospective randomized multicentre study comparing the retropubic and transobturator routes. World journal of urology. 2012;30:117–22. doi: 10.1007/s00345-011-0668-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nilsson CG, Kuuva N, Falconer C, et al. Long-term results of the tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) procedure for surgical treatment of female stress urinary incontinence. International urogynecology journal and pelvic floor dysfunction. 2001;12(Suppl 2):S5–8. doi: 10.1007/s001920170003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schierlitz L, Dwyer PL, Rosamilia A, et al. Three-year follow-up of tension-free vaginal tape compared with transobturator tape in women with stress urinary incontinence and intrinsic sphincter deficiency. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2012;119:321–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823dfc73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richter HE, Albo ME, Zyczynski HM, et al. Retropubic versus transobturator midurethral slings for stress incontinence. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;362:2066–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albo ME, Litman HJ, Richter HE, et al. Treatment success of retropubic and transobturator mid urethral slings at 24 months. The Journal of urology. 2012;188:2281–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.07.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herzog AR, Diokno AC, Brown MB, et al. Two-year incidence, remission, and change patterns of urinary incontinence in noninstitutionalized older adults. Journal of gerontology. 1990;45:M67–74. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.2.m67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shumaker SA, Wyman JF, Uebersax JS, et al. Health-related quality of life measures for women with urinary incontinence: the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire and the Urogenital Distress Inventory. Continence Program in Women (CPW) Research Group. Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 1994;3:291–306. doi: 10.1007/BF00451721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogers RG, Coates KW, Kammerer-Doak D, et al. A short form of the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ-12). International urogynecology journal and pelvic floor dysfunction. 2003;14:164–8. doi: 10.1007/s00192-003-1063-2. discussion 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yalcin I, Bump RC. Validation of two global impression questionnaires for incontinence. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2003;189:98–101. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1996;175:10–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Annals of surgery. 2004;240:205–13. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brittain E, Lin D. A comparison of intent-to-treat and per-protocol results in antibiotic non-inferiority trials. Statistics in medicine. 2005;24:1–10. doi: 10.1002/sim.1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogah J, Cody JD, Rogerson L. Minimally invasive synthetic suburethral sling operations for stress urinary incontinence in women. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2009:CD006375. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006375.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burgio KL, Brubaker L, Richter HE, et al. Patient satisfaction with stress incontinence surgery. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2010;29:1403–9. doi: 10.1002/nau.20877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nygaard IE, McCreery R, Brubaker L, et al. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy: a comprehensive review. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2004;104:805–23. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000139514.90897.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Labrie J, Berghmans BL, Fischer K, et al. Surgery versus physiotherapy for stress urinary incontinence. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;369:1124–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1210627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]