Abstract

Objective

To study the day-night variation of omentin-1 levels and assess whether leptin, and/or short-and long-term energy deprivation alter circulating omentin-1 levels via cytokines.

Design and Methods

Omentin-1 levels were measured hourly in serum samples from six healthy men to evaluate for day-night variation. To study effects of acute energy deprivation and of leptin administration, eight healthy subjects were studied in the fasting state for 72 hours with administration of either placebo or metreleptin in physiological replacement doses. We evaluated the effect of leptin in pharmacological doses on serum omentin-1 and cytokine levels, as well as on omentin-1 levels in ex vivo omental adipose tissue, in fifteen healthy volunteers. To study the effect of chronic energy deprivation and weight loss on omentin-1 levels we followed eighteen obese subjects for 12 months who underwent bariatric surgery.

Results

There is no day-night variation in omentin-1 levels. Short-term and chronic energy deprivation as well as ex vivo leptin administration and physiological replacement doses of leptin do not alter omentin-1 levels, whereas pharmacologic doses of metreleptin reduce omentin-1 levels whereas levels of TNF-α receptor II and IL-6 tend to increase.

Conclusions

Omentin-1 levels are reduced by pharmacological doses of metreleptin independent of effects on cytokine levels.

Keywords: Omentin-1, visceral fat, adipokines

Introduction

Visceral adiposity is associated with a higher risk of metabolic complications of obesity, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia and cardiovascular disease, compared to subcutaneous adiposity.1-3 In an attempt to identify humoral mediators of this risk, studies were performed to identify genes specifically expressed in human omental adipose tissue.4, 5 By sequencing complementary DNA (cDNA) from a human fat library, Yang et al. discovered a gene on chromosome 1q21.3 that was selectively expressed in human omental adipose tissue,5 coding for a 313-amino-acid glycosylated protein,4 which was named omentin to reflect its preferential expression in the omental adipose tissue.5-9 This adipocytokine was later renamed omentin-1 after the discovery of omentin-2, which shares 83% amino acid homology with omentin-1 but is much less abundant in plasma.10

The exact role of omentin-1 in human physiology remains unclear. Cross-sectional human studies have found lower levels of omentin-1 in obese, as compared to lean, individuals, and an inverse correlation with BMI, waist-to-hip ratio,8, 10-15 and insulin resistance.12, 16-19 Physiologic studies have suggested that omentin-1 may play a role in the pathogenesis of complications of obesity. For example, the reduced levels of omentin-1 in obesity may be contributing to the higher risk of hypertension through a reduction in vasodilatory effect of omentin-1 on the vasculature.20, 21 Studies in rodent models have yielded controversial results on whether the changes in omentin-1 levels are secondary or causative to obesity and increased insulin levels. Although a chronic intraperitoneal infusion of omentin-1 led to a significant increase in food intake, weight and altered the related hypothalamic peptides and neurotransmitters in a rat model,22 injection of omentin-1 into the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus in rats did not alter food intake or expression of orexigenic or anorexigenic neuropeptides.23 Tan et al. demonstrated that glucose and insulin were able to suppress omentin-1 secretion, both in human omental fat explants and in in vivo human experiments.6 Interestingly, several studies have found a negative correlation between omentin-1 and leptin levels,10, 13 which persisted even after adjusting for age, sex and BMI,10 suggesting a regulatory relationship between these two adipokines outside of the effects of adiposity.10 However, no interventional study has investigated whether this relationship may be causal, nor is there evidence for whether levels vary with feeding or fasting.

In addition to its proposed metabolic role, data from epidemiologic studies demonstrate a negative correlation between omentin-1 serum levels and levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, suggesting that omentin-1 could have a role in the immune system.12, 16 In particular, investigations have focused on a potential role of omentin-1 in moderating the effects of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). Omentin-1 was found to reduce TNF-α-induced inflammation in vascular smooth muscle cells24 and human vascular endothelial cells,25 possibly via prevention of TNF-α-induced cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 expression.26, 27

The purpose of this study is thus to evaluate whether omentin-1 levels exhibit any day/night variation given many adipokines including leptin demonstrate day/night variability. Also to assess whether chronic or acute energy deprivation affects omentin-1 levels and whether metreleptin administration, in replacement or pharmacological doses, directly affect circulating omentin-1 levels. In addition, we performed ex vivo experiments evaluating whether direct treatment of omental adipose tissue with leptin could change omentin-1 expression.

Materials and methods

Institutional approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and written informed consent was obtained, for all studies. An investigator-initiated Investigational New Drug approval was obtained by Christos Socrates Mantzoros from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the use of metreleptin.

Studies 1, 3 and 4 are from the same original study but only 6 subjects in the isocaloric fed study and only 8 subjects in the fasting state with placebo/physiologic metreleptin study had samples available for evaluation.

Subjects

Study 1: Study in the Isocaloric Fed state

To evaluate for potential day/night variation pattern in omentin-1 levels, six healthy lean male volunteers, were recruited from the community and admitted to the Clinical Research Center (CRC) for four days.28 The participants had no medical problems and did not take any medications. Meals, sleep, and other potential confounders were standardized as previously described.28 From 0800 hours (h) on day 3 to 0800 h on day 4, blood samples were collected every 15 minutes. The samples were pooled hourly to satisfy assay sample volume requirements. The samples were stored at −80°C until assayed.

Study 2: Study in the weight reduced state after Bariatric surgery

To evaluate for any effect of prolonged energy deprivation on omentin-1 levels, 18 patients who underwent bariatric surgery (Roux-en-Y or gastric banding) were recruited. Fasting blood samples were obtained between 0800 h and 1000 h pre-operatively (n=18), and at 3, 6 and 12 months after the surgery (n=16, 16, 10 respectively).

Study 3: Study in the Fasting state with placebo /physiological metreleptin in physiological doses

To evaluate for any effect of acute energy deprivation on omentin-1 levels, eight lean male volunteers (including the six from Study 1) were admitted to the CRC for two separate four-day admissions, separated by at least seven weeks.28 During these admissions, the participants were kept fasting but were allowed free access to non-caloric non-caffeinated drinks. In addition, they were given a multivitamin, 500 mg of NaCl, and 40 mEq of KCl daily. During the two admissions, participants were administered in a randomized, double-blinded fashion either placebo or recombinant human leptin (metreleptin). Clinical quality metreleptin was supplied by Amylin Pharmaceuticals, LLC (a wholly-owned subsidiary of Bristol-Myers Squibb). The daily dose of metreleptin was 0.04 mg/kg per day on day 1, 0.1 mg/kg per day on days 2 and 3, and one dose of 0.025 mg/kg at 0800 h on the fourth day, with the total daily dose divided into four equal doses given every 6 hours starting at 0800 h on day 1. Blood samples were collected through an indwelling peripheral IV line from 0800 h on day 3 to 0800 h on day 4, and processed and stored as described for Study 1. Omentin-1 levels were assayed in six samples per 24-hour period per participant per admission.

Study 4: Study in the Fasting state with pharmacologic doses of metreleptin

To evaluate for any effect of high-dose metreleptin on levels of omentin-1, we administered 0.1 mg/kg of metreleptin to healthy individuals (n=15) subcutaneously. Blood samples were obtained at 30 minutes, 1, 6, 12 and 18 hours after the metreleptin administration.

Study 5: Ex vivo treatment of omental fat with leptin

To evaluate whether leptin has an acute effect on omentin-1 secretion ex vivo, we collected omental fat samples from five patients undergoing abdominal surgery, and abdominal wall subcutaneous fat in three of these patients. The samples were split in half by weight, and then cut up in small pieces. Half of each sample was incubated in control Krebs-Ringer-HEPES buffer (20 mmol/L, pH 7.4) containing 2.5% BSA and 200 nmol/L adenosine, and the other sample was incubated with leptin 100 ng/mL (ProSpec Bio, East Brunswick, NJ). After 20 hours of incubation at 37°C with gentle rocking the supernatant was collected from all the samples for omentin-1 measurement by ELISA.

Hormone assays

Serum omentin-1 was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Biovendor, Candler, NC). The assay had an intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) of 3.7%, and an inter-assay CV of 4.6%. The lower limit of detection was 2 ng/mL. Leptin was measured with a radioimmunoassay (Leptin RIA, Linco Research, St. Louis, MO; now Millipore, Billerica, MA) with an inter-assay CV of 6.2% and an intra-assay CV of 8.3%. Serum soluble TNF-α receptor II (sTNFRII) was measured with an ELISA (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) with an intra-assay CV of 4.4%, inter-assay CV of 6.1% and a lower limit of detection of 7.8 pg/mL. Serum IL-6 was measured with an ELISA (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) with an intra-assay CV of 7.4%, inter-assay CV of 7.8% and a lower limit of detection of 0.156 pg/mL. All samples were run in duplicates using standardized laboratory techniques. Stability of leptin and omentin-1 was confirmed with multiple freeze thaw cycles.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata version 11.1 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX), SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and Sigmaplot version 12.0 (Systat Software, Inc, San José, CA). The descriptive characteristics of the study groups are expressed as mean and standard error of the mean for continuous variables, or percentage and number for categorical variables. Variables were assessed for normality using P-P plots and the Shapiro-Wilkes test, and transformed if needed.

Analysis for day-night variation was performed using Pulse XP (University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA). To evaluate for day-night variability at the level of each subject we utilized the cosine routine that fits a four-parameter cosine function to the time series of each subject's hormonal levels, against the standard deviation between duplicate measurements allowing the evaluation of the amplitude, period, and phase of the oscillations on a subject-to-subject basis. To evaluate for potential day-night variability of omentin-1 levels across all study participants we fit 4-parametric nonlinear ordinal least-squares trigonometric regression models, with constrained period at 24 hours, evaluating potential amplitude, periodicity, and phase agreement. The adjusted nonlinear coefficient of determination (R2) was calculated using these models.

For study 3, we analyzed our data using hierarchical, mixed-effects linear regression models. Hormone levels were modeled as a linear function of time. Condition (fed, fasting with placebo, or fasting with metreleptin) was introduced at the level-2 specification using dummy encoding. Model selection was performed using the Akaike and the Bayesian information criteria (AIC and BIC). The optimal model fit in our data was a two-level model with random intercept but fixed slope with heterogeneous first-order autoregressive residual covariance structure. For studies 2 and 4, we used repeated measures ANOVA with least significant difference post-hoc testing.

A two-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the participants in each study.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants.

| Study 1 (n=6) (Study in the Isocaloric Fed state) | Study 2 (n=18) (Study in the weight reduced state after Bariatric surgery) | Study 3(n=8) (Study in the Fasting state with placebo / metreleptin in physiological doses) | Study 4 (n=15) (Study in the Fasting state with pharmacologic doses of metreleptin) | Study 5 (n=5) (Ex vivo treatment of omental fat with leptin) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 22.3 (19-27) | 52 (33-66) | 23.3 (19-29) | 21.9 (19-28) | 48 (30-61) |

| Male | 6 (100%) | 8 (44.4%) | 8 (100%) | 10 (66.7%) | 2 (40%) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.4 (20.6-25.1) | 47.4 (37.1-74.6) | 23.7 (20.6-25.2) | 25.3 (20.2-34.6) | 44.6 (40.0-50.4) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 0 (0) | 7 (38.9%) | 0 (0) | N/A | 2 (40%) |

| Type of surgery | N/A | Roux-en-Y: 7 (38.9%) Gastric banding: 11 (61.1%) |

N/A | N/A | Roux-en-Y: 1 (20%) Gastric banding: 2 (40%) Sleeve gastrectomy: 1 (20% Cholecystectomy: 1 (20%) |

Values are mean (range) or n (%).

Study 1: Study in the isocaloric fed state:Omentin-1 shows no circadian variation

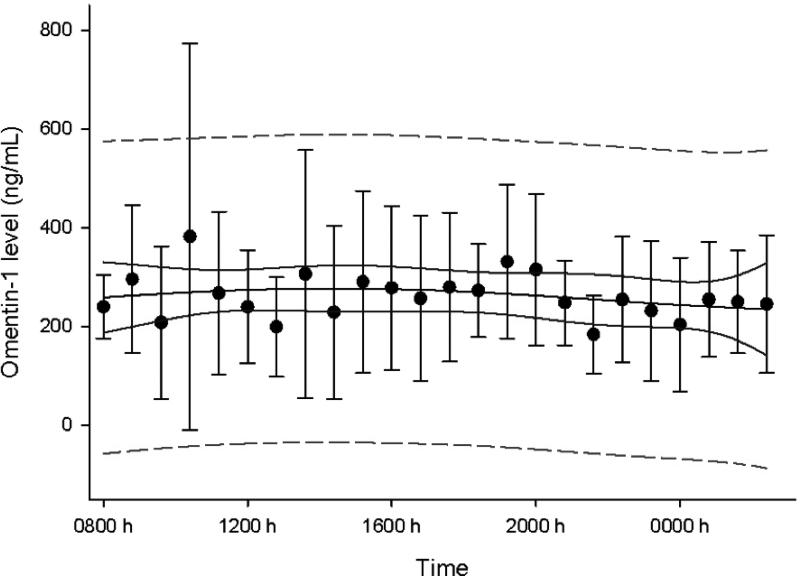

Figure 1 shows the mean omentin-1 level over 24 hours. No significant day-night variation was noted (p=0.92, adjusted R2<0.0001).

Figure 1. Study 1: Study in the isocaloric fed state.

Circadian variation of omentin-1 levels on day 3 of baseline fed state (95% confidence band in solid line, 95% prediction band in dashed line, bars are standard errors)

Study 2: Study in the weight reduced state after bariatric surgery: Omentin-1 levels do not change after bariatric surgery

After bariatric surgery there was significant weight loss (mean BMI dropped from 47.4 ± 8.2 to 39.4 ± 7.4 kg/m2). However, serum levels of omentin-1 did not change [301 ± 22, 342 ± 29, 271 ± 25 and 300 ± 29 ng/mL at 0, 3, 6 and 12 months respectively, p=0.17]. Subgroup analyses by type of surgery (Roux-en-Y vs. gastric banding) or diabetes status did also not show a significant difference.

Study 3: Study in the fasting state with placebo /physiological metreleptin in physiological doses: Omentin-1 levels do not change with acute fasting or with metreleptin injections

Mean omentin-1 levels were 263 ± 48 ng/mL in the fed state, and did not change with fasting (231 ± 38 ng/mL, p=0.58) or fasting along with metreleptin administration in physiological replacement doses (331 ± 63 ng/mL, p=0.25). The slopes of the omentin-1 level trajectories across time were non-significant meaning that omentin-1 levels did not change during the 24 hours of the study. The latter was true for all three states (p-value for slope: p=0.27, p=0.95 and p=0.32 for fed, fasting and fasting with metreleptin respectively).

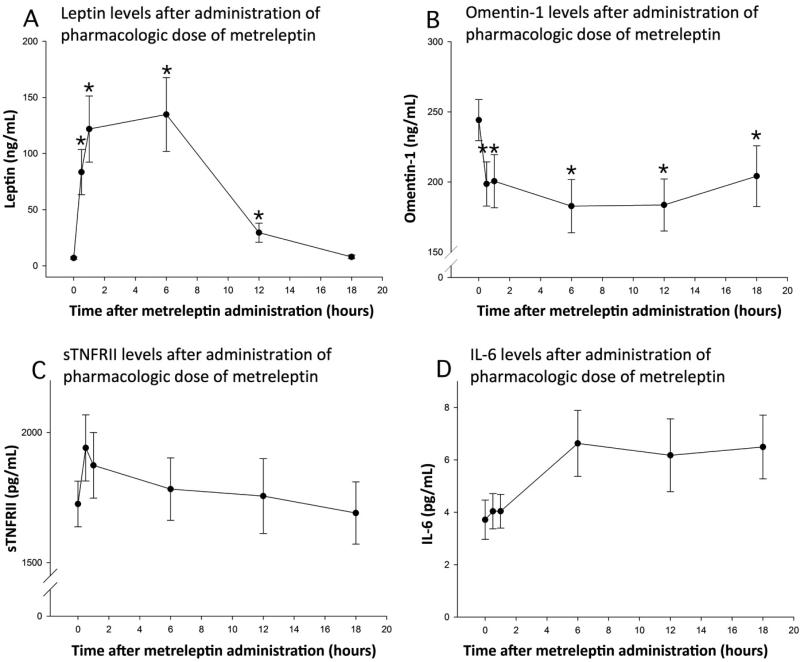

Study 4: Study in the fasting state with pharmacologic doses of metreleptin: Acute hyperleptinemia leads to a reduction in omentin-1 levels but no change in inflammatory cytokines

After administration of pharmacologic doses of metreleptin, serum leptin levels reached a peak mean concentration of 135 ± 33 ng/mL (Figure 2A). Omentin-1 levels dropped significantly (Figure 2B, p=0.03). There was a trend towards an increase in soluble TNF-α receptor II, a marker of activation of the TNF-α system (Figure 2C, p=0.12). There was also trend towards an increase in interleukin-6 levels (Figure 2D, p=0.13) but these were not statistically significant. When performing post-hoc comparisons of IL-6 levels between the values at 0, 0.5 and 1 hour on one hand, to the values at 6, 12 and 18 hours on the other, there was a statistically significant increase (p=0.001). Similarly, when comparing the baseline TNF-α receptor II levels to the levels at 30 minutes, there was a statistically significant increase (p=0.004). However larger studies are needed to fully quantify effects on inflammatory makers.

Figure 2. Study 4:Study in the fasting state with pharmacologic doses of metreleptin.

Levels of leptin (Panel A), omentin-1 (Panel B), sTNFRII (Panel C) and IL-6 (Panel D) after administration of pharmacologic dose metreleptin (0.1mg/kg). Bars indicate standard errors; stars indicate significant change when compared with baseline, p <0.05.

Study 5: Study in the Fasting state with pharmacologic doses of metreleptin: Omentin-1 is not secreted from subcutaneous fat, and secretion from omental fat is not altered by leptin

Omentin-1 levels from subcutaneous adipose tissue were below the level of detection of our assay but were present in omental fat. Omentin-1 levels did not change with ex vivo exposure of omental fat to leptin (163 ng/mL ± 52 ng/mL vs. 158 ± 48 ng/mL, p=0.85).

Discussion

Obesity, especially visceral adiposity, is an inflammatory state. Adipose tissue is known to synthesize and release adipokines, and cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6.29 Leptin, which is secreted in higher levels from subcutaneous fat depots,30 is known to increase macrophage and monocyte proliferation rates, thereby increasing the levels of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6).31 On the other hand, omentin-1 is predominantly secreted from visceral adipose tissue4, 5 and plays an anti-inflammatory role by preventing the TNF-α-induced inflammation.27, 32 Given the roles of both leptin and omentin-1 in obesity and chronic inflammation we investigated whether an interaction exists between leptin and omentin-1. We also studied the physiology of omentin-1 in humans, specifically evaluating for any potential day-night variation in omentin-1 circulating levels and for omentin-1's response to starvation and leptin administration in humans.

Our study demonstrates that in contrast to leptin, there is no day-night variation in omentin-1 levels. This is in agreement with a prior study, which reached the same conclusion but was limited due to the paucity of measurements (every 30 minutes from 0800 h to 1000 h, but then only every two hours, and only one measurement between midnight and 0800 h).6 We also demonstrate, for the first time in humans, that acute energy deprivation, induced by three days of fasting, does not alter omentin-1 levels. Interestingly we failed to demonstrate any change in omentin-1 levels with chronic energy deprivation and weight loss following bariatric surgery. This comes in contrast with prior studies demonstrating that weight loss from a very low-calorie diet,13 metformin,32, 33 or an aerobic exercise program14 led to an increase in omentin-1 levels but this might be explained by loss of more subcutaneous tissue as compared to visceral adipose tissue after bariatric surgery.34 Since omentin-1 is primarily secreted from the visceral adipose tissue there might be no observed difference in omentin-1 level despite of weight loss, if the latter leads to loss of subcutaneous tissue. It is unclear if our results are due to the direct effects of bariatric surgery or to other unmeasured factors.

Our study also demonstrates that high-dose metreleptin administration leads to a marked reduction in omentin-1 levels in vivo, but not ex vivo (leptin 100 ng/mL), suggesting that this is most likely mediated via intermediary factors, activated by in vivo leptin administration and not directly by leptin (which would have expected to alter omentin-1 levels ex vivo). In view of the known effects of leptin as a pro-inflammatory cytokine and proposed role of omentin-1 in inflammation, we also studied whether inflammatory cytokines were altered by high-dose metreleptin. We found that levels of both soluble TNF-α receptor II and IL-6 show a trend towards increase after metreleptin administration, but these changes achieve statistical significance only when time points are consolidated together. Thus, whether the changes in omentin-1 could be attributable to the changes in either TNF-α receptor II or IL-6 remains a possibility and needs be fully confirmed by future, larger studies.

A limitation of our study is that we cannot exclude changes in the samples due to prolonged storage. However all the samples were stored under the same conditions and evaluation of the assays showed stability with multiple freeze-thaw cycles. Random error in laboratory measurements also remains a possibility but this would have been expected to only suppress effect estimates and could have not lead to the statistically significant results presented herein.

In conclusion, our physiologic study demonstrates that omentin-1 does not display any day-night variation and that omentin-1 levels remain unaltered in from both acute and chronic energy deprivation. Thus omentin-1 levels can be measured at any time of the day irrespective of fasting or fed state. In addition, we show that pharmacologic doses of leptin decrease circulating levels of omentin-1 through an indirect mechanism that does not involve the TNF-α or IL-6 system. Whether changes in other hormones or cytokines downstream of leptin and/or leptin-induced activation of the central nervous system could be responsible for these changes in omentin-1 remains to be fully elucidated by future studies.

Acknowledgments

Part of the results described herein was presented at Endo 2012 in Houston, Texas in June 2012.

Grant support, fellowship support: The Mantzoros group was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants 58785, 79929 and 81913. The project described was also supported by Award Number 1I01CX000422-01A1 from the Clinical Science Research and Development Service of the VA Office of Research and Development. Amylin Pharmaceuticals, LLC., supplied metreleptin for this study and approved the design of the study but had no role in the study design; conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. This work was conducted with support from Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award #UL1 RR 025758 and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers, or the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-α

- COX

Cyclooxygenase

- CRC

Clinical Research Center

- h

Hours

- metreleptin

recombinant human leptin

- sTNFRII

soluble TNF-α receptor II

- IL-6

interleukin-6

Footnotes

Disclosure summary: Dr. CS Mantzoros has received research support for investigator-initiated trials from Amylin Pharmaceuticals, LLC (a wholly-owned subsidiary of Bristol-Myers Squibb) through Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. All other authors have no relevant conflicts of interest related to this research.

Clinical trials registration number: Not applicable.

References

- 1.Liu J, Fox CS, Hickson D, Bidulescu A, Carr JJ, Taylor HA. Fatty liver, abdominal visceral fat, and cardiometabolic risk factors: the Jackson Heart Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2715–2722. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.234062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu J, Fox CS, Hickson DA, May WD, Hairston KG, Carr JJ, et al. Impact of abdominal visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue on cardiometabolic risk factors: the Jackson Heart Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:5419–5426. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fox CS, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, Pou KM, Maurovich-Horvat P, Liu CY, et al. Abdominal visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue compartments: association with metabolic risk factors in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2007;116:39–48. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.675355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schaffler A, Neumeier M, Herfarth H, Furst A, Scholmerich J, Buchler C. Genomic structure of human omentin, a new adipocytokine expressed in omental adipose tissue. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1732:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang RZ, Lee MJ, Hu H, Pray J, Wu HB, Hansen BC, et al. Identification of omentin as a novel depot-specific adipokine in human adipose tissue: possible role in modulating insulin action. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290:E1253–1261. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00572.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan BK, Adya R, Farhatullah S, Lewandowski KC, O'Hare P, Lehnert H, et al. Omentin-1, a novel adipokine, is decreased in overweight insulin-resistant women with polycystic ovary syndrome: ex vivo and in vivo regulation of omentin-1 by insulin and glucose. Diabetes. 2008;57:801–808. doi: 10.2337/db07-0990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barth S, Klein P, Horbach T, Dotsch J, Rauh M, Rascher W, et al. Expression of neuropeptide Y, omentin and visfatin in visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissues in humans: relation to endocrine and clinical parameters. Obesity facts. 2010;3:245–251. doi: 10.1159/000319508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Auguet T, Quintero Y, Riesco D, Morancho B, Terra X, Crescenti A, et al. New adipokines vaspin and omentin. Circulating levels and gene expression in adipose tissue from morbidly obese women. BMC Med Genet. 2011;12:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-12-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fain JN, Sacks HS, Buehrer B, Bahouth SW, Garrett E, Wolf RY, et al. Identification of omentin mRNA in human epicardial adipose tissue: comparison to omentin in subcutaneous, internal mammary artery periadventitial and visceral abdominal depots. Int J Obes. 2008;32:810–815. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Souza Batista CM, Yang RZ, Lee MJ, Glynn NM, Yu DZ, Pray J, et al. Omentin plasma levels and gene expression are decreased in obesity. Diabetes. 2007;56:1655–1661. doi: 10.2337/db06-1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shibata R, Takahashi R, Kataoka Y, Ohashi K, Ikeda N, Kihara S, et al. Association of a fat-derived plasma protein omentin with carotid artery intima-media thickness in apparently healthy men. Hypertens Res. 2011;34:1309–1312. doi: 10.1038/hr.2011.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreno-Navarrete JM, Ortega F, Castro A, Sabater M, Ricart W, Fernandez-Real JM. Circulating omentin as a novel biomarker of endothelial dysfunction. Obesity. 2011;19:1552–1559. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moreno-Navarrete JM, Catalan V, Ortega F, Gomez-Ambrosi J, Ricart W, Fruhbeck G, et al. Circulating omentin concentration increases after weight loss. Nutr Metab. 2010;7:27. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saremi A, Asghari M, Ghorbani A. Effects of aerobic training on serum omentin-1 and cardiometabolic risk factors in overweight and obese men. J Sports Sci. 2010;28:993–998. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2010.484070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Mesallamy HO, El-Derany MO, Hamdy NM. Serum omentin-1 and chemerin levels are interrelated in patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus with or without ischaemic heart disease. Diabet Med. 2011;28:1194–1200. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan HY, Guo L, Li Q. Changes of serum omentin-1 levels in normal subjects and in patients with impaired glucose regulation and with newly diagnosed and untreated type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;88:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi JH, Rhee EJ, Kim KH, Woo HY, Lee WY, Sung KC. Plasma omentin-1 levels are reduced in non-obese women with normal glucose tolerance and polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;165:789–796. doi: 10.1530/EJE-11-0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu R, Wang X, Bu P. Omentin-1 is associated with carotid atherosclerosis in patients with metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;93:21–25. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan P, Liu D, Long M, Ren Y, Pang J, Li R. Changes of serum omentin levels and relationship between omentin and adiponectin concentrations in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2011;119:257–263. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1269912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamawaki H, Tsubaki N, Mukohda M, Okada M, Hara Y. Omentin, a novel adipokine, induces vasodilation in rat isolated blood vessels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;393:668–672. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van de Voorde J, Pauwels B, Boydens C, Decaluwe K. Adipocytokines in relation to cardiovascular disease. Metabolism. 2013;62:1513–1521. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brunetti L, Orlando G, Ferrante C, Recinella L, Leone S, Chiavaroli A, et al. Orexigenic effects of omentin-1 related to decreased CART and CRH gene expression and increased norepinephrine synthesis and release in the hypothalamus. Peptides. 2013;44:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brunetti L, Di Nisio C, Recinella L, Chiavaroli A, Leone S, Ferrante C, et al. Effects of vaspin, chemerin and omentin-1 on feeding behavior and hypothalamic peptide gene expression in the rat. Peptides. 2011;32:1866–1871. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kazama K, Usui T, Okada M, Hara Y, Yamawaki H. Omentin plays an anti-inflammatory role through inhibition of TNF-alpha-induced superoxide production in vascular smooth muscle cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;686:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhong X, Li X, Liu F, Tan H, Shang D. Omentin inhibits TNF-alpha-induced expression of adhesion molecules in endothelial cells via ERK/NF-kappaB pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;425:401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.07.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamawaki H. Vascular effects of novel adipocytokines: focus on vascular contractility and inflammatory responses. Biol Pharm Bull. 2011;34:307–310. doi: 10.1248/bpb.34.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamawaki H, Kuramoto J, Kameshima S, Usui T, Okada M, Hara Y. Omentin, a novel adipocytokine inhibits TNF-induced vascular inflammation in human endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;408:339–343. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan JL, Heist K, DePaoli AM, Veldhuis JD, Mantzoros CS. The role of falling leptin levels in the neuroendocrine and metabolic adaptation to short-term starvation in healthy men. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1409–1421. doi: 10.1172/JCI17490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kershaw EE, Flier JS. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2548–2556. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montague CT, Prins JB, Sanders L, Digby JE, O'Rahilly S. Depot- and sex-specific differences in human leptin mRNA expression: implications for the control of regional fat distribution. Diabetes. 1997;46:342–347. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Batra A, Okur B, Glauben R, Erben U, Ihbe J, Stroh T, et al. Leptin: a critical regulator of CD4+ T-cell polarization in vitro and in vivo. Endocrinology. 2010;151:56–62. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan BK, Adya R, Farhatullah S, Chen J, Lehnert H, Randeva HS. Metformin treatment may increase omentin-1 levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes. 2010;59:3023–3031. doi: 10.2337/db10-0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaker M, Mashhadani ZI, Mehdi AA. Effect of Treatment with Metformin on Omentin-1, Ghrelin and other Biochemical, Clinical Features in PCOS Patients. Oman Med J. 2010;25:289–293. doi: 10.5001/omj.2010.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Korner J, Punyanitya M, Taveras C, McMahon DJ, Kim HJ, Inabnet W, et al. Sex differences in visceral adipose tissue post-bariatric surgery compared to matched non-surgical controls. Int J Body Compos Res. 2008;6:93–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]