Abstract

Pseudomonas sp. strain WBC-3 utilizes para-nitrophenol (PNP) as a sole carbon and energy source. The genes involved in PNP degradation are organized in the following three operons: pnpA, pnpB, and pnpCDEFG. How the expression of the genes is regulated is unknown. In this study, an LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) is identified to activate the expression of the genes in response to the specific inducer PNP. While the LTTR coding gene pnpR was found to be not physically linked to any of the three catabolic operons, it was shown to be essential for the growth of strain WBC-3 on PNP. Furthermore, PnpR positively regulated its own expression, which is different from the function of classical LTTRs. A regulatory binding site (RBS) with a 17-bp imperfect palindromic sequence (GTT-N11-AAC) was identified in all pnpA, pnpB, pnpC, and pnpR promoters. Through electrophoretic mobility shift assays and mutagenic analyses, this motif was proven to be necessary for PnpR binding. This consensus motif is centered at positions approximately −55 bp relative to the four transcriptional start sites (TSSs). RBS integrity was required for both high-affinity PnpR binding and transcriptional activation of pnpA, pnpB, and pnpR. However, this integrity was essential only for high-affinity PnpR binding to the promoter of pnpCDEFG and not for its activation. Intriguingly, unlike other LTTRs studied, no changes in lengths of the PnpR binding regions of the pnpA and pnpB promoters were observed after the addition of the inducer PNP in DNase I footprinting.

INTRODUCTION

para-Nitrophenol (PNP), a priority environmental pollutant identified by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, is the most common isomer of mononitrophenols. It enters the environment through industrial release and degradation of parathion-based pesticides. To date, as many as 20 bacterial strains have been isolated for their ability to metabolize PNP under aerobic conditions. The following two major pathways have been elucidated for bacterial degradation of PNP: (i) the hydroquinone (HQ) pathway (1) and (ii) the hydroxyquinol (BT) pathway (2). The HQ pathway has been well characterized in a number of Gram-negative bacteria, such as Pseudomonas sp. strain WBC-3 (3), Moraxella sp. strain (1), and Burkholderia sp. strain SJ98 (4, 5). Gram-positive bacteria, such as Rhodococcus sp. strain SAO101 (6) and Arthrobacter sp. strain JS443 (7), usually degrade PNP via the BT pathway. Although PNP degradation in both Gram-positive and -negative utilizers has been extensively characterized at both the molecular and biochemical levels (3, 7), very little is known about the regulation of PNP degradation, except that two regulatory proteins were proposed to be involved in PNP degradation based purely on the knockout of the putative regulator-encoding genes pnpR in Pseudomonas sp. strain Dll E4 (8) and nphR in Rhodococcus sp. strain PN1 (9).

The LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) family represents the most abundant sort of transcriptional regulatory proteins in the prokaryotic kingdom (10, 11). LTTRs control diverse bacterial functions, such as antibiotic resistance, CO2 fixation, nodulation, virulence, aromatic compound degradation, and amino acid biosynthesis (11, 12). LTTRs function as homo-oligomers, usually tetramers, in which each subunit is composed of approximately 300 amino acids (13). Proteins of this family usually activate promoters transcribed divergently from their own genes in response to corresponding inducer molecules, such as BenM involved in benzoate degradation (14), AtzR in cyanuric acid utilization (15), and HadR in 2,4,6-trichlorophenol catabolism (16). In addition, almost all LTTRs repress their own synthesis (10). It has also been shown that a large group of LTTRs regulate a single target operon, and very few regulatory proteins in this family have been found to control multiple operons (13).

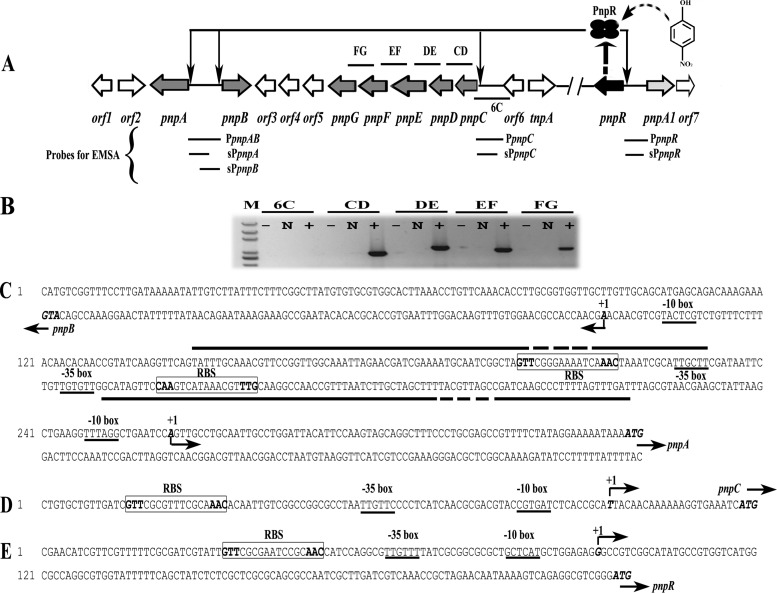

Pseudomonas sp. strain WBC-3 utilizes methyl parathion or its hydrolyzed product, PNP, as a sole source of carbon, nitrogen, and energy (3). Its PNP degradation was PNP inducible (17). Similar to all other Gram-negative PNP utilizers reported, the PNP catabolic gene cluster of strain WBC-3 comprises three operons, as shown in Fig. 1A and B: two adjacent divergently transcribed operons, pnpA and pnpB, and a third operon, pnpCDEFG (3) (GenBank accession number EF577044). PnpA is a flavin adenine dinucleotide-dependent PNP 4-monooxygenase that converts PNP to para-benzoquinone in the presence of NADPH. PnpB is an NADPH-dependent p-benzoquinone reductase that catalyzes the reduction of p-benzoquinone to hydroquinone. Furthermore, the enzymes produced by pnpCDEF next to pnpAB were proposed to convert hydroquinone into β-ketoadipate. In addition to these structural genes, orf6 (formally pnpR in reference 3) located next to pnpCDEF was proposed as a putative LysR-type transcriptional regulator controlling the expression of PNP catabolic operons (3).

FIG 1.

(A) Schematic of the regulatory circuit of the PNP catabolic cluster in Pseudomonas sp. strain WBC-3 (figure not drawn to scale). Four ellipses represent the PnpR tetramer. The curved and dotted arrow stands for binding of para-nitrophenol (PNP) with PnpR. Four thin arrows represent PnpR's activation of the four pnpA, pnpB, pnpCDEFG, and pnpR operons. Two forward slashes represent a gap in genome. The lengths of probes PpnpAB, sPpnpA, sPpnpB, PpnpC, sPpnpC, PpnpR, and sPpnpR, used in electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs), were 334 bp, 182 bp, 185 bp, 270 bp, 119 bp, 344 bp, and 217 bp, respectively. The locations of DNA fragments amplified by RT-PCR are represented by short solid lines above (or below) the relevant genes and designated 6C, CD, DE, EF, and FG. (B) Transcriptional organization of the pnpC, pnpD, pnpE, pnpF, and pnpG genes. Strain WBC-3 was grown at 30°C, and mRNA was extracted after PNP induction. The cDNA was synthesized with random primers. Lane M, molecular marker (100-bp ladder; Transgen). +, presence of RT-PCR products; N, the corresponding negative controls with DNase-treated RNA samples; −, the corresponding negative controls with water. The organization of the upstream regions of the four operons of pnpA and pnpB (C), pnpCDEFG (D), and pnpR (E) is shown. The putative −10 boxes and −35 boxes are underlined. The start codon ATG and TSSs are in italic and bold. TSSs are denoted by bent arrows and +1, and the direction of the arrows indicates the direction of gene transcription. The putative regulatory GTT-N11-AAC binding sites (RBSs) are boxed, and the palindrome is in bold. The solid straight lines indicate the PNP binding sites in DNase I footprinting analysis with or without PNP while the fractured portions denote the region where PnpR is bound tighter in the presence of PNP than in the absence of PNP.

Here, we report that transcription of the multiple operons involved in PNP degradation in strain WBC-3 is regulated by a newly identified LTTR, PnpR, encoded by a gene that is at least 16 kb away from the catabolic genes. This was achieved by the analyses of gene knockout, electrophoretic mobility shift assays, promoter assays, and site-directed mutagenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, culture media, and general DNA manipulation.

Bacterial strains used in this work and their relevant genotypes are summarized in Table 1. Lysogeny broth (LB) medium was used as a rich medium. Liquid cultures were grown in culture tubes or flasks with shaking (180 to 200 rpm) at 30°C for Pseudomonas sp. strains and at 37°C for Escherichia coli strains. Pseudomonas sp. strain WBC-3 was grown at 30°C in LB or minimal medium (MM) (18) with 1 mM PNP as a sole source of carbon and nitrogen. For solid medium, Bacto agar was added to a final concentration of 12 g liter−1. When required, antibiotics and other additions were used as follows (concentration): ampicillin (100 mg liter−1), chloramphenicol (34 mg liter−1), gentamicin (20 mg liter−1), kanamycin (100 mg liter−1), tetracycline hydrochloride (10 mg liter−1), and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) (25 mg liter−1). All reagents used were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) or Fluka Chemical Co. (Buchs, Switzerland). Plasmids and oligonucleotides that were used are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. All DNA manipulations were performed according to standard procedures (19). Restriction enzymes, DNA polymerases, and T4 DNA ligase were purchased from New England BioLabs, Inc. (Ipswich, MA), and Transgen (Beijing, China). Plasmid DNA preparation and DNA purification kits were purchased from Omega (Norcross, GA) and used according to the manufacturer's specifications. Plasmid DNA was transferred into E. coli and Pseudomonas sp. strains by transformation (20), biparental mating (21), or electroporation (22). E. coli DH5α was used as the expression host. All cloning procedures involving PCR were sequence verified by Tsingke (Wuhan, China).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Reference(s) or source |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas sp. strains | ||

| WBC-3 | PNP and methyl parathion utilizer, wild type | 43 |

| WBC3-Δorf6 | WBC-3 mutant with orf6 gene disrupted | This study |

| WBC3-ΔpnpR | WBC-3 mutant with pnpR gene disrupted | This study |

| WBC3-pnpRC | WBC3-ΔpnpR strain with orf6 replaced by pnpR | This study |

| Pseudomonas putida strain PaW340 | Mxy− Mtol− PNP− Strr Trp− | 44, 45 |

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | λ− ϕ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rk− mk−) supE44 thi-1 gyrA relA1 | 46 |

| WM3064 | thrB1004 pro thi rpsL hsdS lacZΔM15 RP4-1360 Δ(araBAD)567 ΔdapA1341::[erm pir(wt)] | 21 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMD18-T | Ampr, lacZ; cloning vector | TaKaRa |

| pEX18Tc | Tcr sacB+, gene replacement vector | 47 |

| pEX18Gm | Gmr; oriT+ sacB+, gene replacement vector with MCS from pUC18 | 47 |

| pTnMod-OKm | Kmr, source of neomycin phosphotransferase II gene (nptII) | 48 |

| pKOorf6 | pEX18Tc with a 1.0-kb PCR fragment carrying the flanking regions of orf6 | This study |

| pKOorf6-Km | pEX18Tc with a 1.0-kb PCR fragment carrying the flanking regions of orf6 disrupted by nptII | This study |

| pKOpnpR | pEX18Tc with a 1.0-kb PCR fragment carrying the flanking regions of pnpR | This study |

| pKOpnpR-Km | pEX18Tc with a 1.0-kb PCR fragment carrying the flanking regions of pnpR disrupted by nptII | This study |

| pKOorf6-GmpnpR | pEX18Tc with a 1.0-kb PCR fragment carrying the flanking regions of orf6 disrupted by aacC1 and pnpR | This study |

| pCM130 | IncP and colE1 origin, Tcr, promoter probe vector | 49 |

| pEX18Tc-cmgfp | Tcr, pEX18Tc with Cm gene and gfp gene | 23 |

| pCMgfp | pCM130 containing gfp and new MCS | This study |

| pCMgfp-lacZ | pCMgfp containing lacZ | This study |

| pCMgfp-spAlacZ | spA-lacZ translational fusion in pCMgfp carrying the sequence between positions −103 and +79 | This study |

| pCMgfp-spBlacZ | spB-lacZ translational fusion in pCMgfp carrying the sequence between positions −91 and +94 | This study |

| pCMgfp-spClacZ | spC-lacZ translational fusion in pCMgfp carrying the sequence between positions −94 and +25 | This study |

| pCMgfp-spRlacZ | spR-lacZ translational fusion in pCMgfp carrying the sequence between positions −92 and +125 | This study |

| pCMgfp-lpAlacZ | lpA-lacZ translational fusion in pCMgfp carrying the sequence between positions −220 and +79 | This study |

| pCMgfp-lpBlacZ | lpB-lacZ translational fusion in pCMgfp carrying the sequence between positions −236 and +94 | This study |

| pCMgfp-lpClacZ | lpC-lacZ translational fusion in pCMgfp carrying the sequence between positions −255 and +25 | This study |

| pCMgfp-lpRlacZ | lpR-lacZ translational fusion in pCMgfp carrying the sequence between positions −219 and +125 | This study |

| pCMgfp-spAmlacZ | pCMgfp-spAlacZ with GTT of RBS to AAA | This study |

| pCMgfp-spBmlacZ | pCMgfp-spBlacZ with GTT of RBS to AAA | This study |

| pCMgfp-spCmlacZ | pCMgfp-spClacZ with GTT of RBS to AAA | This study |

| pCMgfp-spRmlacZ | pCMgfp-spRlacZ with GTT of RBS to AAA | This study |

| pBBR1mcs-2 | Kmr, broad host range, lacPOZ′ | 50 |

| pVLT33 | Kmr, RSF 1010-derived lacIq-Ptac hybrid broad-host-range expression vector, MCS of pUCl8 | 24 |

| pBBR1-tacpnpR | pBBR1mcs-2 containing a 1-kb fragment pnpR (His tag sequence at its 3′ end) and promoter tac | This study |

Coordinates are relative to the transcriptional start of the gene fused to lacZ. The mutated bases are underlined. MCS, multiple cloning site.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer function and name | Sequence (5′ to 3′)a |

|---|---|

| Disruption | |

| EcoRI-orf6-up-F | CCGGAATTCATGACCTTTCCTCAGGCGTA |

| SalI-orf6-up-R | ACGCGTCGACAGGCGAATATTGTAGAGCGA |

| SalI-orf6-down-F | ACGCGTCGACAAAACCCCGTCAAACAATGA |

| PstI-orf6-down-R | AAAACTGCAGGAATTCCACACGGACCTCAC |

| EcoRI-pnpR-up-F | CCGGAATTCGCGAATCCGCAACCATCCAG |

| SalI-pnpR-up-R | ACGCGTCGACGGTCGTTGGCGAAAACGTCG |

| SalI-pnpR-down-F | ACGCGTCGACTGGCGACCCCCGAATACCTT |

| PstI-pnpR-down-R | AACTGCAGGACGTTTCCGATTGCATGTG |

| Infusion-gm-F | ATATTCGCCTGTCGACTCAAGATCCCCTGATTCCCT |

| Infusion-gm-R | AATTTACCGAACAACTCCGC |

| Infusion-pnpR-F | GCGGAGTTGTTCGGTTTGTTATGGGTAGCCAAAAG |

| Infusion-pnpR-R | ACGGGGTTTTGTCGACCGTTTCCGATTGCATGTGTA |

| EMSA and lacZ fusion | |

| KpnI-mcs-gfp-F | CGGGGTACCGCTCTGCAGGTCGACCCTGGATCCCCGGATGCTTTCTGTCAGTGGAGAGGGT |

| SacI-gfp-R | CGAGCTCCATGTGTAATCCCAGCAGCT |

| gfp1-F | TTTCTGTCAGTGGAGAGGGT |

| gfp1-R | CATGTGTAATCCCAGCAGCT |

| gfp2-F | TTCTGTCAGTGGAGAGGGTG |

| gfp2-R | GCTGTTTCATATGATCTGGG |

| gfp3-F | TGCCCGAAGGTTATGTACAG |

| gfp3-R | GTCTCTCTTTTCGTTGGGAT |

| BamHI-lacZ-F | CGGGATCCATGACCATGATTACGGATTC |

| PstI-lacZ-R | CCCAAGCTTTTATTTTTGACACCAGACCA |

| SphI-pA-F | ACATGCATGCTCCGGTTGGCAAATTAGAAC |

| BamHI-pA-R | CGGGATCCCATTTTATTTTTCCTATAGAAAACG |

| SphI-pB-F | ACATGCATGCTTCGATCGTTCTAATTTGCC |

| BamHI-pB-R | CGGGATCCCATGTCGGTTTCCTTGATAA |

| SphI-pC-F | ACATGCATGCCTGTGCTGTTGATCGTTCGC |

| BamHI-pC-R | CGGGATCCCATGATTTCACCTTTTTTGTTGTAA |

| SphI-pR-F | ACATGCATGCCGAACATCGTTCGTTTTTCG |

| BamHI-pR-R | CGGGATCCCATCCCGACGCCTCTGACTT |

| SphI-pAm-F | ACATGCATGCTCCGGTTGGCAAATTAGAACGATCGAAAATGCAATCGGCTAAAACGGGAAAATCAAACTAAATCG |

| SphI-l-pA-F | ACATGCATGCGGCTTATGTGTGCGTGGCAC |

| SphI-pBm-F | ACATGCATGCTTCGATCGTTCTAATTTGCCAACCGGAACAAATGCAAATACTGAACCTTGATAC |

| SphI-l-pB-F | ACATGCATGCTTCCTATAGAAAACGGCTCG |

| SphI-pCm-F | ACATGCATGCCTGTGCTGTTGATCAAACGCGTTTCGCAAACACAA |

| SphI-l-pC-F | ACATGCATGCATTCGGACTGGTCGATAAAC |

| SphI-pRm-F | ACATGCATGCCGAACATCGTTCGTTTTTCGCGATCGTATTAAACGCGAATCCGCAACCATCC |

| SphI-l-pR-F | ACAT GCATGC GTATGCCCTCTGAATAACGC |

| SphI-pAB-F | ACATGCATGCTCCCCAAACCCCGTCTTCTA |

| BamHI-pAB-R | CGGGATCCGCAATGAAGTCAGCACAATC |

| KpnI-tac-F | GGGGTACCGAAAGGTTTTGCACCATTCG |

| BamHI-ptac-R | CGGGATCCCTTAAAGTTAAACAAAATTATTTCTAG |

| BamHI-ex-pnpR-F | CGGGATCCATGGCGCCAGGCGTGGTATTT |

| SacI-His tag-pnpR-R | CCGAGCTCTTAATGATGATGATGATGGTGTTGCTCTTCCTGTTCCGG |

| qRT-PCR | |

| 16srRNAinduce-F | GGGAACTTTGTGAGGTTGCT |

| 16srRNAinduce-R | GTCTGGACCGTGTCTCAGTT |

| pnpAinduce-F | GCACTGAAACTGGGTAAAGC |

| pnpAinduce-R | CATGGCGATAGGCGAAATCC |

| pnpBinduce-F | CGGAACTGATGCCTGAAGAG |

| pnpBinduce-R | GGCGTTGCGTAAGGGATGCT |

| pnpCinduce-F | CACGGTGGAGATCATCAGTG |

| pnpCinduce-R | ATGACGATGGCGAACTCATC |

| pnpRinduce-F | AAGCGGGTAACTTCTCCAAC |

| pnpRinduce-R | GAGATGCCCACTTCAGACAG |

| 5′ RACE | |

| pnpA-GSP1 | CGGCGAAGGCGAGAC |

| pnpB-GSP1 | CCCGCTCTTGACCTGA |

| pnpC-GSP1 | GTAGCCGAGGTTCAGG |

| pnpR-GSP1 | GCTGGAACGGTGGAA |

| pnpA-GSP2 | CGGCTTTACCCAGTTTCAGT |

| pnpB-GSP2 | ACTTCGACATCACCGACTT |

| pnpC-GSP2 | TGACGGGCCTCGCCACTGAT |

| pnpR-GSP2 | AGTTGCTGGACACGGGTGG |

| pnpA-GSP3 | CCGGACCACCGCCAACTACA |

| pnpB-GSP3 | CGGCCATTTTGTAGATGTG |

| pnpC-GSP3 | GATCTCCACCGTGCCTTTGC |

| pnpR-GSP3 | TTGGCGGCGTTGGAGAAGT |

| Transcriptional organization | |

| clusterorf6-F | TGCCAAACGATGGGAAGAGG |

| clusterpnpC-R | GAGCGTCGAGCTTGAGGAAT |

| clusterpnpC-F | CTTCGCCTCGCTGGATAACT |

| clusterpnpD-R | CCTTGAGCGTGCCGTTAAAG |

| clusterpnpD-F | CGCAAAAATGGCGAAAACCT |

| clusterpnpE-R | GTGAACATCAGCGGAAAGTT |

| clusterpnpE-F | ATGGACCCGGAAACCGAAAT |

| clusterpnpF-R | ATCACAGTCTTGGGCAGGAC |

| clusterpnpF-F | ACCCCGATCTATGGCTTGAC |

| clusterpnpG-R | AGGGTGTCCGACAACAAAAT |

Oligonucleotide positions altered from the template sequences are underlined. Restriction sites are in boldface.

Plasmid construction.

To construct a knockout plasmid for orf6, fragment orf6-up containing sequence upstream of orf6 was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA of strain WBC-3 using the primer pairs EcoRI-orf6-up-F and SalI-orf6-up-R. The fragment orf6-down containing sequence downstream of orf6 was amplified by PCR using primer pairs SalI-orf6-down-F and PstI-orf6-down-R. The EcoRI/SalI-digested orf6-up fragment and SalI/PstI-digested orf6-down fragment were then cloned into EcoRI/PstI-digested pEX18Tc by three-way ligation, yielding plasmid pKOorf6. The kanamycin-resistance gene nptII digested with SalI was cloned into pKOorf6, yielding plasmid pKOorf6-Km for knockout of orf6. The plasmid pKOpnpR-Km was constructed in the same way as pKOorf6-Km for pnpR knockout. The entire pnpR gene together with the gentamicin resistance gene aacC1 was cloned into SalI-digested pKOorf6 using an In-Fusion Advantage PCR cloning kit (Clontech, Beijing, China), yielding plasmid pKOorf6-GmpnpR for pnpR complementation.

To construct plasmids for promoter activity assays, the fragment mcs-gfp (where mcs is multiple cloning site) amplified with template pEX18Tc-cmgfp (23) was cloned into KpnI/SacI-digested pCM130, yielding plasmid pCMgfp. The fragment lacZ was cloned into BamHI/HindIII-digested pCMgfp, yielding plasmid pCMgfp-lacZ. The wild-type and mutated promoters were cloned into SphI/BamHI-digested pCMgfp-lacZ, yielding plasmids pCMgfp-spAlacZ, pCMgfp-spBlacZ, pCMgfp-spClacZ, pCMgfp-spRlacZ, pCMgfp-lpAlacZ, pCMgfp-lpBlacZ, pCMgfp-lpClacZ, pCMgfp-lpRlacZ, pCMgfp-spAmlacZ, pCMgfp-spBmlacZ, pCMgfp-spCmlacZ, and pCMgfp-spRmlacZ, in which all the promoters and lacZ were transcribed in the same direction. The fragment tac digested with KpnI and BamHI and the fragment pnpR containing His tag sequence digested with BamHI and SacI were cloned into KpnI-/SacI-digested pBBR1mcs-2, yielding plasmid pBBR1-tacpnpR. During the above constructions, genomic DNA of strain WBC-3 was used as the template for amplifying relevant promoters inserted upstream of lacZ, while plasmid pVLT33 (24) was used to amplify the tac promoter. The two tac promoters are transcribed in the same direction in plasmid pBBR1-tacpnpR.

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR).

Pseudomonas sp. strain WBC-3 and its mutants were grown in LB and MM (1:4, vol/vol) in duplicates. PNP was added into one tube at a final concentration of 0.1 mM when the culture was grown to an optical density of 0.4 at 600 nm (OD600) and was incubated for another 3 h before harvest. Total RNA was extracted and then heated at 42°C for 2 min with genomic DNA (gDNA) Eraser (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) for removal of genomic DNA before being placed on ice for 1 min. Total cDNA was synthesized in 20-μl reverse transcription (RT) reaction mixtures containing 1 μg of total RNA, 4.0 μl of 5× PrimeScript Buffer 2, 4.0 μl of RT primer mix, and 1.0 μl of PrimeScript RT Enzyme Mix I (TaKaRa), incubated at 37°C for 15 min. Finally, RT enzyme was inactivated by incubation at 85°C for 5 s.

qRT-PCR was performed using a CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and iQ SYBR green Supermix (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The expression levels of all the genes tested were normalized to 16S rRNA gene expression as an internal standard and quantified according to a previously described method (25).

β-Galactosidase assays.

Steady-state β-galactosidase assays were used to examine the expression of promoter-lacZ fusions in the surrogate host Pseudomonas putida PaW340, which is unable to degrade PNP. Preinocula of bacterial strains harboring the relevant plasmids were grown to saturation in 1 ml of LB medium at 30°C. Cells were then diluted by adding 4 ml of MM into the cultures, and 0.1 mM inducer was added when required. Diluted cultures were shaken for an additional 5 h at 30°C before harvest. β-Galactosidase activity was determined by SDS- and chloroform-permeabilized cells as described previously (26, 27).

Purification of PnpR-His6.

PnpR with a C-terminal His tag (PnpR-His6) was purified from Pseudomonas putida PaW340 harboring pBBR1mcs2-tacpnpR by nickel affinity chromatography according to the manufacturer's specifications (Qiagen, Hilden, German). One liter of cultures was grown to an OD600 of 0.4 to 0.5 at 30°C and then transferred to a 12°C shaker. After 30 min, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mM to induce overexpression of PnpR-His6 overnight. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 13,500 × g for 3 min at 4°C, resuspended in 40 ml of binding buffer (0.3 M NaCl, 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4), and sonicated. Broken cells were centrifuged at 13,500 × g for 1 h at 4°C, and the supernatant was charged onto a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) affinity column that had been preequilibrated with binding buffer. The column was washed extensively with binding buffer containing 120 mM imidazole, and bound proteins were eluted with binding buffer containing 200 to 400 mM imidazole gradient. Fractions were collected, and the presence of PnpR-His6 was checked by SDS-PAGE. The fractions of interest were then dialyzed in 2 liters of dialytic buffer (0.1 M NaCl, 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, 20% glycerol, and 0.1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]) overnight at 4°C with a magnetic stirring apparatus. Finally, the fractions were concentrated using a 10,000-molecular-weight-cutoff (MWCO) centrifugal filter unit (Millipore Co., Billerica, MA). The protein concentration was calculated using a protein assay kit (Beyotime Co., Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Protein purity was estimated visually by SDS-PAGE to be >95%.

Gel filtration chromatography.

The solution containing PnpR-His6 or protein markers was charged onto a column (1.6 by 60 cm) of Hiload Superdex 200 prep grade (fast-performance liquid chromatography [FPLC] system; GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) that was equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 0.1 M NaCl for 2 h at a flow rate of 0.5 ml min−1. Then, the protein was eluted with this buffer at the same rate. Protein markers were used as reference proteins (28).

5′ RACE.

The transcriptional start sites (TSSs) of the pnpA, pnpB, pnpCDEFG, and pnpR operons were determined using a 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Total RNA was isolated from strain WBC-3 induced by PNP. First-strand cDNA was synthesized with the primers pnpA-, pnpB-, pnpC-, and pnpR-GSP1 (Table 2) by reverse transcription. Template RNA in the cDNA-RNA hybrid was degraded by RNase H (TaKaRa), and the single-stranded RNAs were degraded by RNase T1 (TaKaRa). The cDNA was subsequently purified. Homopolymeric tailing of the cDNA was performed with terminal transferase and dCTP (TaKaRa). The tailed cDNA was then amplified using the abridged anchor primer (AAP) and pnpA-, pnpB-, pnpC-, and pnpR-GSP2 (Table 2). Finally, this PCR product was used as a template for a nested PCR with AAP and primers pnpA-, pnpB-, pnpC-, and pnpR-GSP3 (Table 2) and then cloned into pMD18-T (TaKaRa) for sequencing.

EMSAs.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) were performed as previously described (29). Double-stranded DNA probes containing the wild-type and the mutated versions of the PnpR binding sites were obtained by PCR using genomic DNA from strain WBC-3 as the template (primers are shown in Table 2). EMSA reaction mixtures containing 0.025 μM DNA fragments and increasing amounts of purified His6-PnpR were assembled in 20-μl reaction mixtures in binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM KCl, 12.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, and 5% glycerol [vol/vol]) on ice. Two DNA fragments (0.025 μM [each]) consisting of approximately 150 and 600 bp of the gfp gene amplified from pEX18Tc-cmgfp were used as negative controls in the binding reactions when required. After incubation for 30 min at 25°C, the samples were immediately loaded onto a 6% native polyacrylamide gel at 4°C and electrophoresed at 170 V (constant voltage) for 1 h. The gels were subsequently stained with SYBR green I according to the manufacturer's instructions (BioTeKe Co., Beijing, China) and photographed.

DNase I footprinting assay.

DNase I footprinting assays were performed as described previously (30). For preparation of the probe, the promoter region of pnpA-pnpB was PCR amplified with primers SphI-pAB-F and BamHI-pAB-R, and the product was cloned into the pMD18-T vector. The obtained plasmid was used as the template for further preparation of fluorescent 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM)-labeled probes with the primer pairs M13F-47(FAM)/M13R-48 for the sense strand and M13R-48(FAM)/M13F-47 for the antisense strand. The FAM-labeled probe was purified by a Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega, Fitchburg, WI) and was quantified with NanoDrop 2000C (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). For each assay, 0.025 μM probe was incubated with 1.6 μM PnpR in the EMSA buffer in a total volume of 40 μl with or without PNP (0.3 mM). After incubation for 30 min at 30°C, 10 μl of solution containing 0.015 units of DNase I (Promega) and 100 nmol of freshly prepared CaCl2 was added and further incubated for 1 min at 25°C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 140 μl of DNase I stop solution (200 mM unbuffered sodium acetate, 30 mM EDTA, and 0.15% SDS). First, samples were extracted with phenol-chloroform and precipitated with ethanol, and then the pellets were dissolved in 30 μl of MiniQ water. The preparation of the DNA ladder, electrophoresis, and data analysis were the same as described previously (31), with the exception that a GeneScan-LIZ500 size standard (Applied Biosystems) was used.

Bioinformatics and genome sequencing.

The genomic sequence was obtained by 454 sequencing as previously described (32). Imperfect palindromic sequences containing the consensus-binding motif (T-N11-A) were analyzed with the online European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite (EMBOSS).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS, version 20.0.0, software. Paired-sample tests were used to calculate probability values (P) of the transcription of pnpA, pnpB, pnpC, and pnpR. Paired-sample tests were also used to calculate probability values (P) of β-galactosidase activity analyses of pnpA, pnpB, pnpC, and pnpR promoters containing regulatory binding sites (RBSs) or their corresponding mutants. P values of <0.05 and <0.01 were considered to be statistically significant and greatly statistically significant, respectively.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The contig 001 of the WBC-3 genome sequence containing pnpR has been submitted to the GenBank database under accession number KM019215.

RESULTS

pnpR is essential in PNP degradation.

To determine the involvement of the putative transcriptional regulator Orf6 in activating catabolic clusters for PNP degradation, its coding gene was knocked out in strain WBC-3. First, the suicide plasmid pKOorf6-Km in E. coli WM3064 (a diaminopimelic acid auxotroph) was transferred to strain WBC-3 by biparental mating. The gene orf6 in strain WBC-3 was replaced by the kanamycin resistance gene nptII cassette through double homologous recombination, thereby yielding the mutant strain WBC3-Δorf6. Contrary to our previous assumption, strain WBC3-Δorf6 was still capable of utilizing PNP. It was able to grow to an OD600 of 0.13 after 24 h on PNP plus MM, similar to the wild-type strain WBC3, as shown in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material. This result demonstrated that Orf6 was not the transcriptional regulator of PNP degradation. Subsequently, contig 001 from genome sequencing of strain WBC-3 was found to contain the gene pnpA1 (orf wbc3-000011), and the sequence of its product is 57.7% identical to that of PnpA. Divergently transcribed to pnpA1, the gene pnpR (orf wbc3-000010) encoding a LysR-like regulatory protein was present (Fig. 1A). This gene is located at least 16 kb away from the PNP catabolic cluster described in our previous study (3), which led us to explore the possible involvement of PnpR in activating PNP catabolic operons by knocking out the pnpR gene. The resulting strain WBC3-ΔpnpR was no longer able to utilize PNP. Since it was difficult for plasmids to be introduced into WBC-3, the mutant strain was complemented by inserting pnpR into the orf6 locus of the mutant genome through a double crossover. The complemented strain WBC3-pnpRC, in which orf6 was replaced by pnpR, regained the ability to grow on PNP (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

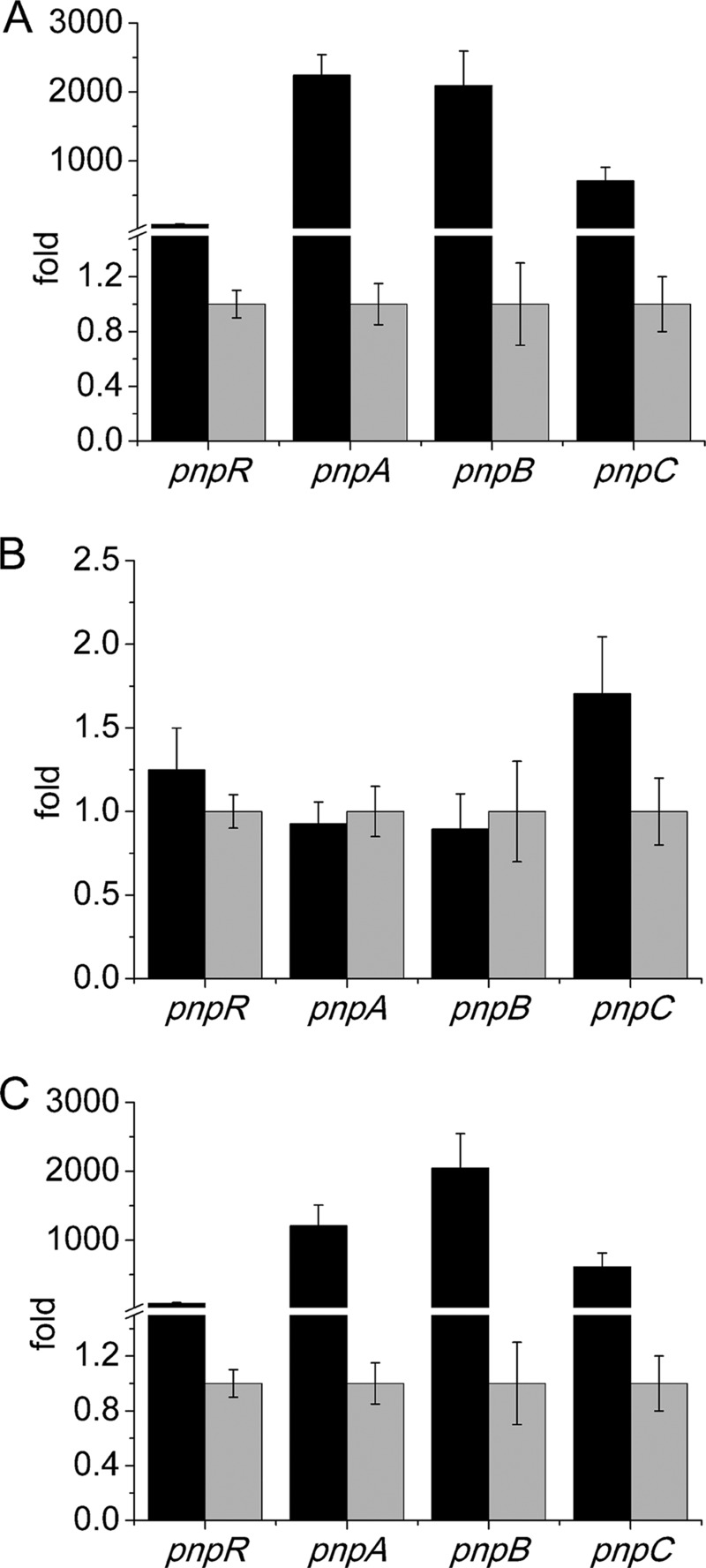

After PnpR was confirmed to be involved in PNP degradation, the impact of PnpR on the PNP degradation operons was further analyzed by measuring the transcriptional levels of each PNP degradation operon as well as the pnpR operon in both the wild-type and mutant strains. In the presence of PNP, the transcriptional levels of four tested genes (each representing one of the four operons) in strain WBC-3 were enhanced dramatically compared to the levels in the absence of PNP, with the transcriptional levels of pnpA, pnpB, pnpC, and pnpR being 2,243-, 2,093-, 710-, and 77-fold higher, respectively, based on qRT-PCR assays. In contrast, the transcriptional levels of all four of the above genes were almost unaltered in strain WBC3-ΔpnpR, regardless of the presence or absence of PNP. In the pnpR-complemented strain, WBC3-pnpRC, the transcriptional levels of four genes were similar to those of the corresponding genes in the wild-type WBC-3 strain under the same conditions (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Transcriptional analysis of pnpA, pnpB, pnpCDEFG, and pnpR operons in the wild-type strain WBC-3 (A), pnpR knockout strain WBC3-ΔpnpR (B), and the complemented pnpR knockout strain WBC3-pnpRC (C), in the presence and absence of PNP. RNA samples were isolated from the above three strains grown on LB plus MM (1:4, vol/vol) with 3 h of induction with PNP or without PNP. qRT-PCR was manipulated as described in the Materials and Methods section. The levels of gene expression in each sample were calculated as the fold expression ratio after normalization to 16S rRNA gene transcriptional levels. The values are averages of three independent qRT-PCR experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations. There was a significant difference in the transcription levels of pnpA, pnpB, pnpC, and pnpR between strains WBC3-ΔpnpR and WBC3-pnpRC (P < 0.001, paired-sample test). Changes (fold) in gene expression levels in the presence (black) and absence (gray) of induction with PNP are indicated.

All of these results indicate that PnpR is involved in the activation of the PNP catabolic pathway under PNP-induced conditions and that it also activates its own transcription.

Mapping of the transcriptional start sites of operons pnpA, pnpB, pnpCDEFG, and pnpR.

To identify the promoter regions of the pnp operons responsible for PnpR binding, their transcription start sites (TSSs) were determined by 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′ RACE) using total RNA extracted from strain WBC-3 grown in the presence of PNP. The identified TSSs were detected in the upstream regions of four operons, as shown in Fig. 1C, D, and E. Relative to the TSSs, the A bases of the ATG start codons of pnpA, pnpB, pnpC, and pnpR are located at positions 77, 92, 23, and 123, respectively. A more detailed analysis of the promoters is shown in Fig. 1C, D, and E.

Purified PnpR is a tetramer.

To obtain a functional regulatory protein for in vitro assays, PnpR-His6 was overproduced from the broad-host-range vector-based construct pBBR1-tacpnpR in Pseudomonas putida PaW340 and purified by nickel affinity chromatography. By analytical gel filtration in the chromatography buffer with or without PNP, the homologously produced PnpR-His6 was eluted as a single peak corresponding to 160 kDa (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), which is consistent with PnpR as a tetramer. The deduced size of the monomer, 35 kDa, was confirmed by SDS-PAGE (see Fig. S3).

PnpR binds with the promoter regions of pnpA-pnpB, pnpC, and pnpR.

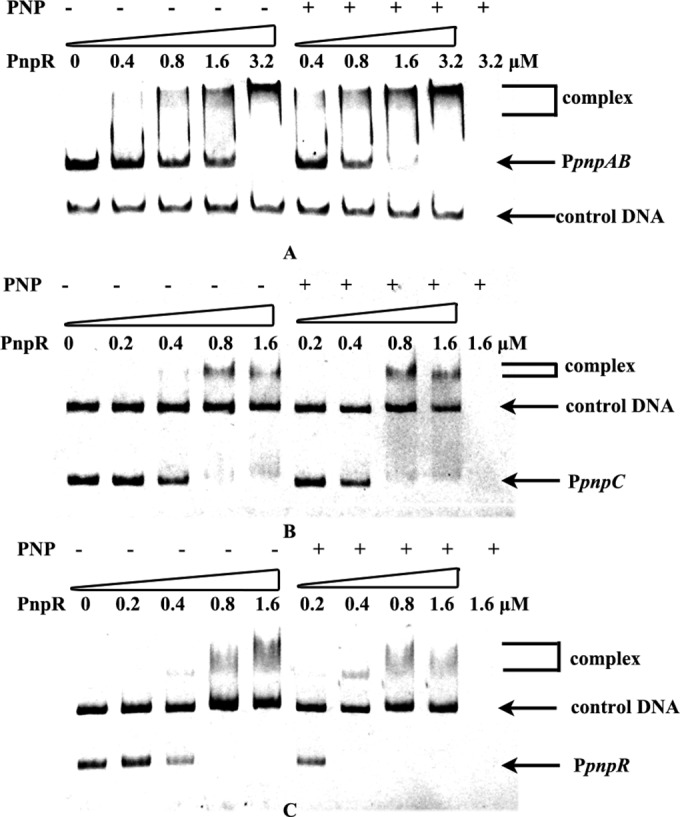

EMSA was carried out to test the interaction of PnpR with PpnpAB, a 334-bp fragment of the intergenic region of pnpA and pnpB amplified using primers SphI-pAB-F and BamHI-pAB-R. As shown in Fig. 3A, diffused bands were formed in all sample lanes. As PnpR responded to PNP in vivo, binding was also tested in the presence of 0.3 mM PNP. When PNP was present, the saturating concentration of PnpR required for complete binding with PpnpAB was somewhat lower. An approximately 300-bp fragment of PpnpC between positions −255 and +25 relative to the TSS of pnpC, which was amplified using primers SphI-l-pC-F and BamHI-pC-R, was used in EMSAs for the interaction of PnpR with the pnpCDEFG promoter region. The presence of the formed complex, shown in Fig. 3B, suggested that PnpR was able to bind specifically with the promoter of the operon pnpCDEFG. When PnpR was tested with the promoter region of its own operon, an approximately 350-bp fragment of PpnpR between positions −219 and +125 relative to TSS of pnpR, which was amplified using primers SphI-l-pR-F and BamHI-pR-R, was used in EMSAs for the interaction of PnpR with pnpR promoter region. While specific binding with diffused bands was observed between PnpR and PpnpR, the saturating concentration of PnpR required for complete binding with PpnpR was lower when PNP was present (Fig. 3C), which is similar to the binding of PnpR with PpnpAB shown in Fig. 3A.

FIG 3.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays of PnpR binding with pnp promoters. (A) The first five lanes contain 0.025 μM DNA and no PNP; the next four lanes contain 0.025 μM DNA and 0.3 mM PNP; the last lane contains 0.3 mM PNP. Amounts of PnpR are indicated above the lanes. An approximately 150-bp DNA fragment, gfp1, amplified from the gfp gene in the plasmid pEX18Tc-cmgfp was used as a control DNA (0.025 μM). Free probe is an intergenic fragment of PpnpAB of 334 bp between pnpA and pnpB. Complex PnpR-PpnpAB is indicated by a bracket. The binding reaction was performed at 25°C for 1 h. (B) The first five lanes contain 0.025 μM DNA and no PNP; the next four lanes contain 0.025 μM DNA and 0.3 mM PNP; the last lane contains 0.3 mM PNP. Amounts of PnpR are indicated above the lanes. An approximately 600-bp DNA fragment, gfp2, amplified from the gfp gene in the plasmid pEX18Tc-cmgfp, was used as a control DNA (0.025 μM). Free probe is a fragment of PpnpC of 270 bp upstream of the pnpC translational start codon. Complex PnpR-PpnpC is indicated by a bracket. The binding reaction was performed at 25°C for 1 h. (C) The first five lanes contain 0.025 μM DNA and no PNP; the next four lanes contain 0.025 μM DNA and 0.3 mM PNP; the last lane contains 0.3 mM PNP. Amounts of PnpR are indicated above the lanes. An approximately 600-bp DNA fragment, gfp2, amplified from the gfp gene in the plasmid pEX18Tc-cmgfp, was used as a control DNA (0.025 μM). Free probe is a fragment of PpnpR of 344 bp upstream of the pnpR translational start codon. Complex PnpR-PpnpR is indicated by a bracket. The binding reaction was performed at 25°C for 1 h.

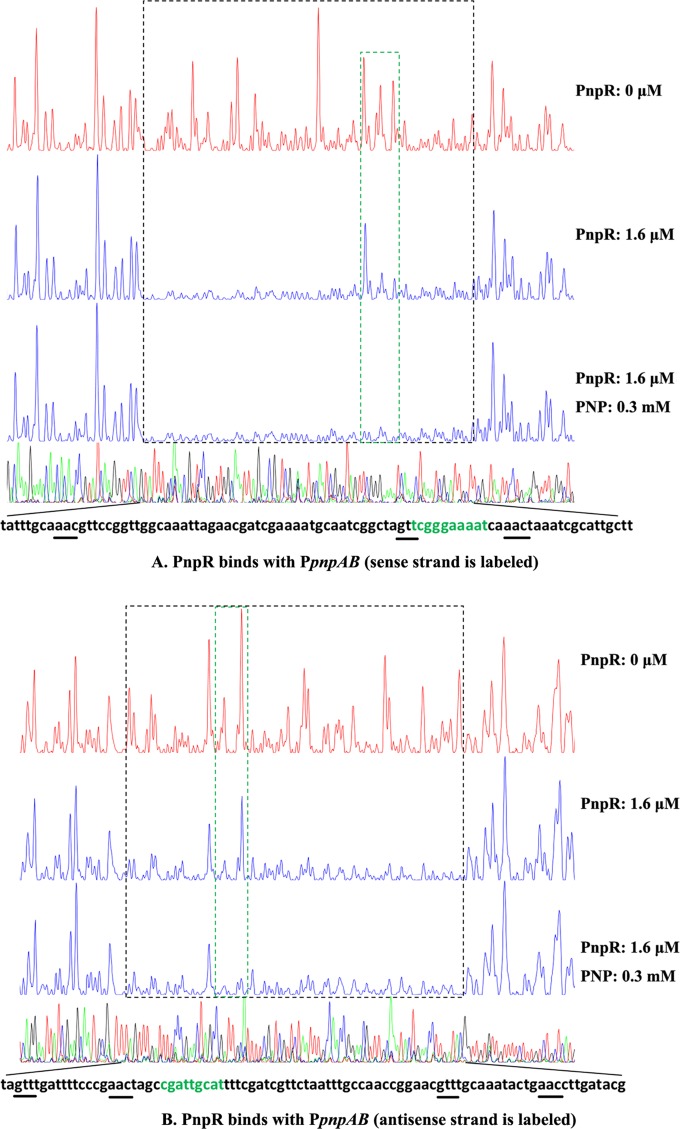

To obtain a more detailed picture of PnpR interacting with its specific binding site, PnpR binding with PpnpAB was also tested by a DNase I footprinting assay. With or without PNP, the same continuous 82-bp region of the sense strand from positions −116 to −35, relative to the pnpA transcriptional start, was protected by PnpR. In the presence of PNP, the binding of PpnpAB with PnpR from positions −60 to −51 was slightly enhanced (Fig. 4A). A similar pattern was also observed at the antisense strand, with continuous protection spanning from positions −124 to −37 (an 88-bp region) relative to the pnpB transcriptional start site, with or without PNP. In the presence of PNP, the binding of PpnpAB with PnpR from −101 to −93 was also slightly enhanced (Fig. 4B).

FIG 4.

The DNase I footprinting analysis of PnpR binding to PpnpAB in which the sense strand (A) and antisense strand (B) are labeled. An amount of 0.025 μM probe PpnpAB covering the entire intergenic region of pnpA and pnpB was incubated with 1.6 μM PnpR in the EMSA buffer with or without PNP (0.3 mM). The intergenic fragment was labeled with 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM) dye, incubated with 1.6 μM PnpR (blue line) or without PnpR (red line). The regions protected by PnpR from DNase I cleavage are indicated with black dotted boxes. The differences between protected regions with and without PNP are indicated with green dotted boxes. Sequences of the PnpR protected region are shown at the bottom, and the palindrome sequence of the regulatory binding site (RBS) is underlined.

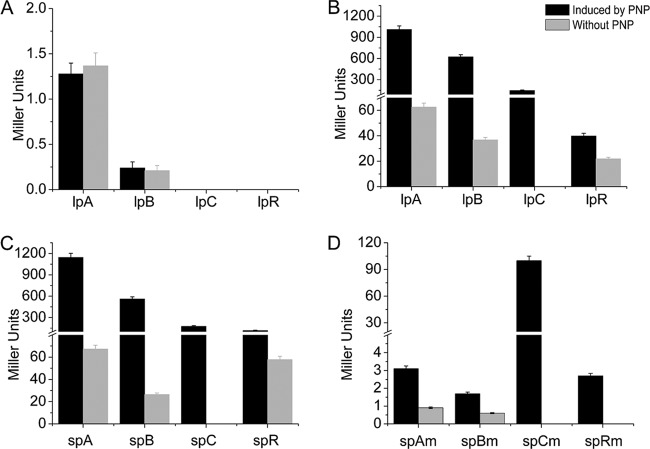

Key promoter regions of pnpA, pnpB, pnpC, and pnpR.

Constructs pCMgfp-lpAlacZ, pCMgfp-lpBlacZ, pCMgfp-lpClacZ, and pCMgfp-lpRlacZ contain approximately 300 bp of the corresponding promoter regions of pnpA, pnpB, pnpCDEFG, and pnpR, respectively (Table 1 and Fig. 3), which are at positions approximately −200 bp upstream of TSSs to their ATG translational start codons. Their corresponding constructs, pCMgfp-spAlacZ, pCMgfp-spBlacZ, pCMgfp-spClacZ, and pCMgfp-spRlacZ, contain approximately 200-bp fragments from −85 bp upstream of the TSSs to the ATG start codons, respectively, for the above four operons. These eight constructs were used to assess the requirement of cis-acting DNA sequences for the correct regulation of pnpR expression in strain PaW340 carrying pBBR1-tacpnpR. Meanwhile, the above constructs with 300-bp promoter regions were introduced into strain PaW340 carrying pBBR1mcs-2 as negative controls (Fig. 5A). Without PNP, the expression levels of LacZ in the constructs with the 300-bp corresponding promoter regions and those with the 200-bp regions were all evidently low. When PNP was added to the cultures, the expression levels of LacZ were enlarged 16.1-, 16.9-, and 1.8-fold in strain PaW340(pBBR1-tacpnpR) carrying pCMgfp-lpAlacZ, pCMgfp-lpBlacZ, and pCMgfp-lpRlacZ (Fig. 5B), respectively. Similar results were obtained from their counterparts with 200-bp fragments (Fig. 5C). As the basal expression level of pCMgfp-lpClacZ was undetectable, the fold change increase could not be calculated for this case. Nevertheless, strain PaW340(pBBR1-tacpnpR) carrying pCMgfp-lpClacZ or pCMgfp-spClacZ exhibited similar β-galactosidase activities of 146.8 and 177.3 Miller units, respectively, with PNP induction (Fig. 5B and C). All of the above results suggested that the 200-bp promoter region fragments contained the necessary motifs for corresponding transcriptional activation of the operons. It is noted that the promoter regions denote the 200-bp fragments from −85 bp upstream of the TSSs to the ATG start codons for pnpA, pnpB, pnpC, and pnpR.

FIG 5.

Determination of the promoter activities of the pnpA, pnpB, pnpC, and pnpR operons and their derivatives. (A) Expression of promoter-lacZ translational fusions containing approximately 300-bp promoters of above the four operons in PaW340(pBBR1mcs-2) without PnpR. The β-galactosidase activities were determined in the above strains containing pCMgfp-lpAlacZ (lpA in the figure), pCMgfp-lpBlacZ (lpB), pCMgfp-lpClacZ (lpC), and pCMgfp-lpRlacZ (lpR) with or without PNP. (B) Expression of promoter-lacZ translational fusions containing approximately 300-bp promoters of the above four operons in PaW340(pBBR1-tacpnpR) with PnpR expression in cis. The β-galactosidase activities were determined in the above strain containing pCMgfp-lpAlacZ (lpA in the figure), pCMgfp-lpBlacZ (lpB), pCMgfp-lpClacZ (lpC), and pCMgfp-lpRlacZ (lpR) with or without PNP. There was a significant difference in promoter activity with or without PNP among the above four strains (P < 0.001, paired-samples test). (C) Expression of promoter-lacZ translational fusions containing 200-bp promoters of the above four operons in PaW340(pBBR1-tacpnpR) with PnpR expression in cis. The β-galactosidase activities were determined in the above strain containing pCMgfp-spAlacZ (spA in the figure), pCMgfp-spBlacZ (spB), pCMgfp-spClacZ (spC), and pCMgfp-spRlacZ (spR) with or without PNP. There was a significant difference in promoter activity with or without PNP among the above four strains (P < 0.001, paired-samples test). (D) Expression of promoter-lacZ translational fusions containing 200-bp mutant promoters of the above four operons in PaW340(pBBR1-tacpnpR) with PnpR expression in cis. The β-galactosidase activities were determined in the above strain containing pCMgfp-spAmlacZ (spAm in the figure), pCMgfp-spBmlacZ (spBm), pCMgfp-spCmlacZ (spCm), and pCMgfp-spRmlacZ (spRm) with or without PNP. There was a significant difference in the promoter activity between regulatory binding sites (RBSs) of the pnpA, pnpB, and pnpR operons and their mutated sites from strain PaW340(pBBR1-tacpnpR) grown on LB plus MM (1:4) with PNP or without PNP (P < 0.001, paired-samples test).

Motif required for high-affinity PnpR binding and activation of pnpA, pnpB, pnpCDEFG, and pnpR promoters.

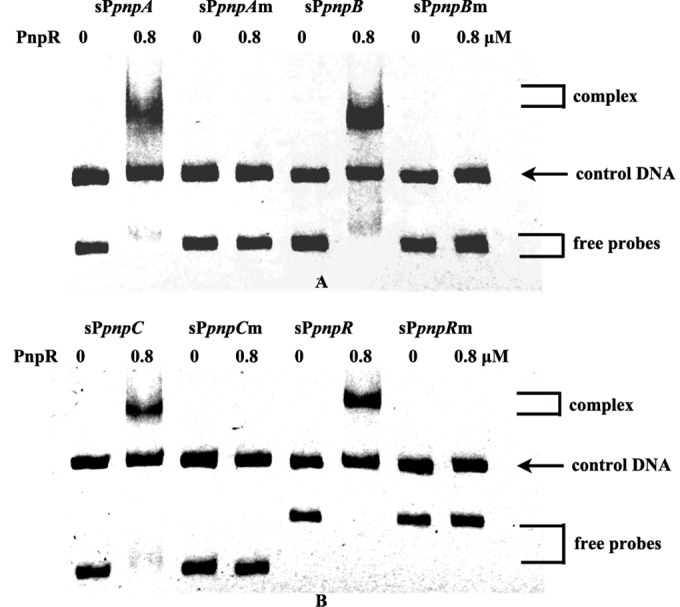

Through the bioinformatics analysis described in Materials and Methods, all promoters of the four operons were found to contain a 17-bp imperfect palindromic sequence GTT-N11-AAC (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material), which is consistent with the RBS consensus motif T-N11-A in the LTTR family. To test the involvement of this putative RBS sequence in positive autoregulation of pnpR and activation of the operons pnpA, pnpB, and pnpCDEFG, four mutated promoter regions bearing substitutions at this consensus sequence were constructed. It was found that the mutated RBS fragments harboring three substitutions from GTT to AAA lost the ability to bind with PnpR, in contrast to the wild-type promoters (Fig. 6A and B).

FIG 6.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays of PnpR binding with wild-type pnp promoters and mutant pnp promoters. The left lane of each pair (0 PNP) contains 0.025 μM DNA, and the right lane of each pair (0.8 μM PnpR) contains 0.025 μM DNA without PNP. Wild-type promoters are fragments of approximately 200 bp, from −85 bp relative to the TSSs to gene translational start codons of the pnpA, pnpB, pnpC, and pnpR genes, respectively, and are designated sPpnpA, sPpnpB, sPpnpC, and sPpnpR. Mutant promoters are fragments in which GTT of RBS is changed to AAA in the wild-type promoters and are designated sPpnpAm, sPpnpBm, sPpnpCm, and sPpnpRm. Free probes and complexes (the product of protein PnpR binding with promoter DNA) are indicated by brackets. The binding reaction was performed at 25°C for 1 h. An approximately 400-bp DNA fragment, gfp3, amplified from the gfp gene in the plasmid pEX18Tc-cmgfp was used as a control DNA (0.025 μM).

Further analysis of these four RBSs with the consensus sequence of GTT-N11-AAC revealed a conserved G in the 5th base and A/T from the 8th to 10th base present in the motif GTT-N11-AAC (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). After comparison of the entire protected regions between the antisense strand and sense strand of the pnpA and pnpB promoters in the footprinting assay (Fig. 4A and B), it was found that PnpR was bound with the sequence GTT-TGCAAATACTG-AAC (the fifth base G is in bold) but did not bind with its reverse complemented sequence, GTT-CAGTATTTGCA-AAC (the fifth base A is in bold). Intriguingly, no hypersensitive sites in protected regions were present in these footprinting assays. Notably, there were approximately only 10 nucleotides present in protected regions in the downstream regions of the sequences of RBSs for the pnpA and pnpB promoters.

To assess the requirement of RBS sequences for correct binding of PnpR with the above four pnp operon promoters, plasmids with mutated RBSs (from GTT to AAA) were constructed. Without PNP, their expression levels were all very low or undetectable in strain PaW340(pBBR1-tacpnpR) carrying pCMgfp-spAmlacZ, pCMgfp-spBmlacZ, pCMgfp-spRmlacZ, or pCMgfp-spCmlacZ with mutated RBSs. Unlike their wild types shown in Fig. 5C, the expression levels of the first three were still low in the presence of PNP (Fig. 5D). Surprisingly, the strain with pCMgfp-spCmlacZ for the pnpCDEFG operon exhibited as high as 100.0 Miller units of β-galactosidase activity (Fig. 5D) in the presence of PNP, a level similar to the wild-type level (Fig. 5C).

DISCUSSION

In this study, an LysR-type regulatory protein, PnpR, located at least 16 kb away from the PNP catabolic cluster in Pseudomonas sp. strain WBC-3, was identified and characterized to be involved in triggering the transcription of pnp genes within three catabolic operons. PnpR was found to be a tetramer in solution with or without PNP, a characteristic, active oligomeric state of typical LysR-type transcriptional regulators (LTTRs) (13, 33, 34). Interestingly, PnpR regulates multiple functional operons involved in PNP degradation over a long distance rather than regulating a single adjacent divergently transcribed operon in most LTTRs identified so far. Among the GTT-N11-AAC regulatory binding sites (RBSs) identified in this study, GTT or AAC was proven to be vital for PnpR binding to the promoter region by EMSA after site-direct mutagenesis, whereas several nucleotides between GTT and AAC were also shown by DNase I footprinting to be potentially important for binding.

Most specific regulators in LTTRs repress their own gene expression and activate divergently transcribed target genes (10). In contrast, PnpR positively regulates its own synthesis and the operons at least 16 kb away from its encoding gene, pnpR. This phenomenon is similar to the global regulators of LTTRs, including LrhA in E. coli, HexA in Erwinia carotovora, and PecT in Erwinia chrysanthemi (35). They were shown to control the expression of genes required for flagellation, motility, and chemotaxis in response to environmental and growth phase signals in the respective strains by long-distance regulation and positive self-regulation. However, based on an NCBI BLAST search of homologues, PnpR with the specific inducer PNP in this study is present only in the strains capable of degrading PNP and its derivatives, such as Burkholderia sp. strain SJ98 (36), Burkholderia sp. strain Y123 (37), and Pseudomonas sp. strain NyZ402 (38). This suggests that PnpR in strain WBC-3 is a specific regulator rather than a global regulator and that pnpR might have evolved independently from the PNP catabolic genes. Despite the fact that most of the specific LTTRs were found to regulate single multiple operons, several have also been found to regulate multiple operons. One of the well-studied examples is BenM that activates the benABCDE and benPK operons involved in benzoate biodegradation of Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 (39). However, unlike BenM, PnpR is a positive autoregulatory LTTR.

Generally, interaction of LTTRs with the promoter regions occurs at the following two dissimilar sites: a strong binding determinant, the regulatory binding site (RBS), and a weak binding determinant, the activation binding site (ABS). They are required for activation of the effector operon by interacting with the LTTR to change the bending angle of DNA and the protected region in the presence of the inducer (40). However, no change in lengths of the PnpR binding regions with the pnpA and pnpB promoters was observed after the addition of the inducer PNP in DNase I footprinting (Fig. 4). One of the possibilities for this observation may be that PnpR needs other inducers in addition to PNP to act like other LTTRs or that PnpR does not mimic in vitro its behavior in vivo.

Direct transcriptional regulation depends on the binding of a regulator with the promoter of a gene operon whose expression it regulates, while the indirect regulation does not need a regulator to interact with the promoter (41). The significant loss of promoter activities of pnpA, pnpB, and pnpR after mutation of their RBSs (Fig. 5C and D) indicates that PnpR directly regulates the three operons of pnpA, pnpB, and pnpR. In contrast, no difference in promoter activity was observed between wild-type and mutant RBSs of the promoter for the pnpCDEFG operon (Fig. 5C and D). This may be because of indirect regulation of the pnpCDEFG operon by PnpR or the presence of an additional binding site that was undetectable under current conditions in vitro. It is generally accepted that promoters have evolved from constitutive expression to inducible expression (42). The above results suggest that the pnpA, pnpB, and pnpR promoters may have evolved simultaneously in a highly competitive environment in conjunction with their transcriptional regulator PnpR. On the other hand, the promoter of pnpCDEFG may have evolved from a different origin, which is evidenced by a longer distance (20 nucleotides) between the RBS and −35 box of the pnpCDEFG promoter than the distances for the other three promoters (9 to 10 nucleotides) (Fig. 4).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 31070050) and the National Key Basic Research Program of China (973 Program, grant 2012CB725202).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02720-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Spain JC, Gibson DT. 1991. Pathway for biodegradation of p-nitrophenol in a Moraxella sp. Appl Environ Microbiol 57:812–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jain RK, Dreisbach JH, Spain JC. 1994. Biodegradation of p-nitrophenol via 1,2,4-benzenetriol by an Arthrobacter sp. Appl Environ Microbiol 60:3030–3032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang JJ, Liu H, Xiao Y, Zhang XE, Zhou NY. 2009. Identification and characterization of catabolic para-nitrophenol 4-monooxygenase and para-benzoquinone reductase from Pseudomonas sp. strain WBC-3. J Bacteriol 191:2703–2710. doi: 10.1128/JB.01566-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vikram S, Pandey J, Kumar S, Raghava GP. 2013. Genes involved in degradation of para-nitrophenol are differentially arranged in form of non-contiguous gene clusters in Burkholderia sp. strain SJ98. PLoS One 8:e84766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Min J, Zhang J-J, Zhou N-Y. 2014. The para-nitrophenol catabolic gene cluster is responsible for 2-chloro-4-nitrophenol degradation in Burkholderia sp. strain SJ98. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:6212–6222. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02093-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitagawa W, Kimura N, Kamagata Y. 2004. A novel p-nitrophenol degradation gene cluster from a gram-positive bacterium, Rhodococcus opacus SAO101. J Bacteriol 186:4894–4902. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.15.4894-4902.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perry LL, Zylstra GJ. 2007. Cloning of a gene cluster involved in the catabolism of p-nitrophenol by Arthrobacter sp. strain JS443 and characterization of the p-nitrophenol monooxygenase. J Bacteriol 189:7563–7572. doi: 10.1128/JB.01849-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen W, Liu W, Zhang J, Tao J, Deng H, Cao H, Cui Z. 2010. Cloning and characterization of a gene cluster involved in the catabolism of p-nitrophenol from Pseudomonas putida DLL-E4. Bioresour Technol 101:7516–7522. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeo M, Murakami M, Niihara S, Yamamoto K, Nishimura M, Kato D, Negoro S. 2008. Mechanism of 4-nitrophenol oxidation in Rhodococcus sp. strain PN1: characterization of the two-component 4-nitrophenol hydroxylase and regulation of its expression. J Bacteriol 190:7367–7374. doi: 10.1128/JB.00742-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maddocks SE, Oyston PC. 2008. Structure and function of the LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) family proteins. Microbiology 154:3609–3623. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/022772-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schell MA. 1993. Molecular biology of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators. Annu Rev Microbiol 47:597–626. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henikoff S, Haughn GW, Calvo JM, Wallace JC. 1988. A large family of bacterial activator proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 85:6602–6606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tropel D, van der Meer JR. 2004. Bacterial transcriptional regulators for degradation pathways of aromatic compounds. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 68:474–500. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.3.474-500.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bundy BM, Collier LS, Hoover TR, Neidle EL. 2002. Synergistic transcriptional activation by one regulatory protein in response to two metabolites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:7693–7698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102605799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porrua O, Lopez-Sanchez A, Platero AI, Santero E, Shingler V, Govantes F. 2013. An A-tract at the AtzR binding site assists DNA binding, inducer-dependent repositioning and transcriptional activation of the PatzDEF promoter. Mol Microbiol 90:72–87. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torii H, Machida A, Hara H, Hatta T, Takizawa N. 2013. The regulatory mechanism of 2,4,6-trichlorophenol catabolic operon expression by HadR in Ralstonia pickettii DTP0602. Microbiology 159:665–677. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.063396-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei M, Zhang JJ, Liu H, Zhou NY. 2010. para-Nitrophenol 4-monooxygenase and hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase catalyze sequential transformation of 4-nitrocatechol in Pseudomonas sp. strain WBC-3. Biodegradation 21:915–921. doi: 10.1007/s10532-010-9351-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu H, Wang SJ, Zhou NY. 2005. A new isolate of Pseudomonas stutzeri that degrades 2-chloronitrobenzene. Biotechnol Lett 27:275–278. doi: 10.1007/s10529-004-8293-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inoue H, Nojima H, Okayama H. 1990. High efficiency transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. Gene 96:23–28. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90336-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saltikov CW, Newman DK. 2003. Genetic identification of a respiratory arsenate reductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:10983–10988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834303100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwasaki K, Uchiyama H, Yagi O, Kurabayashi T, Ishizuka K, Takamura Y. 1994. Transformation of Pseudomonas putida by electroporation. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 58:851–854. doi: 10.1271/bbb.58.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu F, Jiang X, Zhang J-J, Zhou N-Y. 2014. Construction of an engineered strain capable of degrading two isomeric nitrophenols via a sacB-and gfp-based markerless integration system. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98:4749–4756. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5567-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Lorenzo V, Eltis L, Kessler B, Timmis KN. 1993. Analysis of Pseudomonas gene products using lacIq/Ptrp-lac plasmids and transposons that confer conditional phenotypes. Gene 123:17–24. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller JH. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 27.Griffith KL, Wolf RE Jr. 2002. Measuring beta-galactosidase activity in bacteria: cell growth, permeabilization, and enzyme assays in 96-well arrays. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 290:397–402. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suga K, Kabashima T, Ito K, Tsuru D, Okamura H, Kataoka J, Yoshimoto T. 1995. Prolidase from Xanthomonas maltophilia: purification and characterization of the enzyme. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 59:2087–2090. doi: 10.1271/bbb.59.2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao C, Hu C, Zheng Z, Ma C, Jiang T, Dou P, Zhang W, Che B, Wang Y, Lv M. 2012. Regulation of lactate utilization by the FadR-type regulator LldR in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 194:2687–2692. doi: 10.1128/JB.06579-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zianni M, Tessanne K, Merighi M, Laguna R, Tabita FR. 2006. Identification of the DNA bases of a DNase I footprint by the use of dye primer sequencing on an automated capillary DNA analysis instrument. J Biomol Tech 17:103–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y, Cen XF, Zhao GP, Wang J. 2012. Characterization of a new GlnR binding box in the promoter of amtB in Streptomyces coelicolor inferred a PhoP/GlnR competitive binding mechanism for transcriptional regulation of amtB. J Bacteriol 194:5237–5244. doi: 10.1128/JB.00989-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar S, Vikram S, Raghava GP. 2012. Genome sequence of the nitroaromatic compound-degrading bacterium Burkholderia sp. strain SJ98. J Bacteriol 194:3286. doi: 10.1128/JB.00497-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muraoka S, Okumura R, Ogawa N, Nonaka T, Miyashita K, Senda T. 2003. Crystal structure of a full-length LysR-type transcriptional regulator, CbnR: unusual combination of two subunit forms and molecular bases for causing and changing DNA bend. J Mol Biol 328:555–566. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00312-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hryniewicz MM, Kredich NM. 1995. Hydroxyl radical footprints and half-site arrangements of binding sites for the CysB transcriptional activator of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol 177:2343–2353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gibson KE, Silhavy TJ. 1999. The LysR homolog LrhA promotes RpoS degradation by modulating activity of the response regulator SprE. J Bacteriol 181:563–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar S, Vikram S, Raghava GP. 2013. Genome annotation of Burkholderia sp. SJ98 with special focus on chemotaxis genes. PLoS One 8:e70624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lim JS, Choi BS, Choi AY, Kim KD, Kim DI, Choi IY, Ka JO. 2012. Complete genome sequence of the fenitrothion-degrading Burkholderia sp. strain YI23. J Bacteriol 194:896. doi: 10.1128/JB.06479-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wei Q, Liu H, Zhang JJ, Wang SH, Xiao Y, Zhou NY. 2010. Characterization of a para-nitrophenol catabolic cluster in Pseudomonas sp. strain NyZ402 and construction of an engineered strain capable of simultaneously mineralizing both para- and ortho-nitrophenols. Biodegradation 21:575–584. doi: 10.1007/s10532-009-9325-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Collier LS, Gaines GL III, Neidle EL. 1998. Regulation of benzoate degradation in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 by BenM, a LysR-type transcriptional activator. J Bacteriol 180:2493–2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Porrua O, Garcia-Jaramillo M, Santero E, Govantes F. 2007. The LysR-type regulator AtzR binding site: DNA sequences involved in activation, repression and cyanuric acid-dependent repositioning. Mol Microbiol 66:410–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Madan Babu M, Teichmann SA. 2003. Evolution of transcription factors and the gene regulatory network in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res 31:1234–1244. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cases I, de Lorenzo V. 2001. The black cat/white cat principle of signal integration in bacterial promoters. EMBO J 20:1–11. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Y, Zhang X, Liu H, Wang Y, Xia X. 2002. Study on Pseudomonas sp. WBC-3 capable of complete degradation of methylparathion. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Bao 42:490–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams PA, Murray K. 1974. Metabolism of benzoate and the methylbenzoates by Pseudomonas putida (arvilla) mt-2: evidence for the existence of a TOL plasmid. J Bacteriol 120:416–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu H, Zhang JJ, Wang SJ, Zhang XE, Zhou NY. 2005. Plasmid-borne catabolism of methyl parathion and p-nitrophenol in Pseudomonas sp. strain WBC-3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 334:1107–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woodcock DM, Crowther PJ, Doherty J, Jefferson S, DeCruz E, Noyer-Weidner M, Smith SS, Michael MZ, Graham MW. 1989. Quantitative evaluation of Escherichia coli host strains for tolerance to cytosine methylation in plasmid and phage recombinants. Nucleic Acids Res 17:3469–3478. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.9.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoang TT, Karkhoff-Schweizer RR, Kutchma AJ, Schweizer HP. 1998. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene 212:77–86. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dennis JJ, Zylstra GJ. 1998. Plasposons: modular self-cloning minitransposon derivatives for rapid genetic analysis of gram-negative bacterial genomes. Appl Environ Microbiol 64:2710–2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marx CJ, Lidstrom ME. 2001. Development of improved versatile broad-host-range vectors for use in methylotrophs and other Gram-negative bacteria. Microbiology 147:2065–2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kovach ME, Elzer PH, Hill DS, Robertson GT, Farris MA, Roop RM II, Peterson KM. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.