Abstract

Proximity effect is a form of synergistic effect exhibited when cellulases work within a short distance from each other, and this effect can be a key factor in enhancing saccharification efficiency. In this study, we evaluated the proximity effect between 3 cellulose-degrading enzymes displayed on the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell surface, that is, endoglucanase, cellobiohydrolase, and β-glucosidase. We constructed 2 kinds of arming yeasts through genome integration: ALL-yeast, which simultaneously displayed the 3 cellulases (thus, the different cellulases were near each other), and MIX-yeast, a mixture of 3 kinds of single-cellulase-displaying yeasts (the cellulases were far apart). The cellulases were tagged with a fluorescence protein or polypeptide to visualize and quantify their display. To evaluate the proximity effect, we compared the activities of ALL-yeast and MIX-yeast with respect to degrading phosphoric acid-swollen cellulose after adjusting for the cellulase amounts. ALL-yeast exhibited 1.25-fold or 2.22-fold higher activity than MIX-yeast did at a yeast concentration equal to the yeast cell number in 1 ml of yeast suspension with an optical density (OD) at 600 nm of 10 (OD10) or OD0.1. At OD0.1, the distance between the 3 cellulases was greater than that at OD10 in MIX-yeast, but the distance remained the same in ALL-yeast; thus, the difference between the cellulose-degrading activities of ALL-yeast and MIX-yeast increased (to 2.22-fold) at OD0.1, which strongly supports the proximity effect between the displayed cellulases. A proximity effect was also observed for crystalline cellulose (Avicel). We expect the proximity effect to further increase when enzyme display efficiency is enhanced, which would further increase cellulose-degrading activity. This arming yeast technology can also be applied to examine proximity effects in other diverse fields.

INTRODUCTION

Cellulose is the most abundant organic polymer on earth (1). Lignocellulosic biomass has increasingly attracted attention as a promising alternative feedstock for biofuel (2). However, producing biofuels from lignocellulosic biomass by using the current technology is exceedingly expensive because of 2 possible reasons: (i) the recalcitrance that hinders the deconstruction and use of the feedstock and (ii) the involvement of multiple steps, because of which a complicated infrastructure is required and the risk of contamination is enhanced. Overcoming these obstacles requires both a synergistic reaction between cellulases and consolidated bioprocessing (CBP), which integrates the whole biofuel production process (3, 4).

Certain naturally occurring microorganisms can degrade cellulose. Aerobic fungi, such as Trichoderma reesei, secrete several kinds of cellulases, mainly endoglucanase (EG), cellobiohydrolase (CBH), and β-glucosidase (BG), to completely degrade cellulose, and the free cellulases are recognized to degrade cellulose synergistically (5). Conversely, anaerobic bacteria, such as Clostridium thermocellum and Clostridium cellulovorans, produce a complex of cellulases, the cellulosome, and degrade lignocellulosic biomass efficiently (6–8). When the cellulases are located near each other within the cellulosome, they exhibit higher cellulose-degrading activity than they do when not present in the cellulosome; this is referred to as the proximity effect (9, 10).

In a previous study, to exploit the proximity effect and achieve CBP, we constructed an arming Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast that simultaneously displays, on the surface of yeast cells, the 3 kinds of cellulases that are necessary for the complete degradation of cellulose into glucose (11). The yeast strain could directly degrade and ferment cellulose to ethanol. Because the cellulases were concentrated on the cell surface and were nearer each other than they are when they exist freely, the cellulases were expected to degrade cellulose with a greater degree of synergy (i.e., to exhibit the proximity effect) than they do when they exist freely. However, the proximity effect has not been demonstrated in previous studies because of the challenges associated with quantifying the amounts of the displayed cellulases.

In this study, we used genome integration to construct a yeast strain that simultaneously displays EG II and CBH II from T. reesei and BG I from Aspergillus aculeatus, and we tagged each of the cellulases with a polypeptide or a fluorescent protein to enable the quantification of the displayed enzymes. The mixture of single-cellulase-displaying yeasts was prepared by quantifying and adjusting the amount of the displayed cellulases. Subsequently, we measured the proximity effect between the displayed cellulases by comparing the phosphoric acid-swollen cellulose (PASC)- and crystalline cellulose (Avicel)-degrading activities of the 3-cellulase-displaying yeast strain with those of the mixture of single-cellulase-displaying yeasts. Furthermore, in this study, we investigated the relationship between the proximity effect and the distance between cellulases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

All the primers used for constructing plasmids are listed in Table 1. PCR was performed using KOD-plus DNA polymerase (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). The plasmids used for cellulase display were constructed as follows. Before constructing the plasmids used for genome integration, we constructed the multicopy plasmids used for displaying the cellulases tagged with a fluorescent protein or polypeptide. The T. reesei EG II gene present in pEG (12) was PCR amplified using the BglII-FLAG-linker-EG-F and EG-SphI-extra-R primers to attach a FLAG tag to the N terminus of EG. The amplified EG DNA fragment was inserted into pRS425display (12), which was cut using BglII and SphI. The resulting plasmid included 2 FLAG tags on the N and C termini of EG, because a FLAG tag-encoding sequence was originally included in pRS425display; the plasmid constructed was named pRS425DF-EG.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids and primers used in this study

| Plasmid or primer | Feature or sequencea |

|---|---|

| Plasmids | |

| pRS425DF-EG | Cell surface display of EG II with FLAG tag, LEU2 |

| pRS426DE-CBH | Cell surface display of CBH II with EGFP, URA3 |

| pRS423Dm-BG | Cell surface display of BG I with mCherry, HIS3 |

| pRS402 | ADE2 |

| pRS403 | HIS3 |

| pRS405 | LEU2 |

| pRS406 | URA3 |

| pRS403DF-EG | Cell surface display of EG II with FLAG tag, HIS3 |

| pRS405DF-EG | Cell surface display of EG II with FLAG tag, LEU2 |

| pRS406DF-EG | Cell surface display of EG II with FLAG tag, URA3 |

| pRS403DE-CBH | Cell surface display of CBH II with EGFP, HIS3 |

| pRS405DE-CBH | Cell surface display of CBH II with EGFP, LEU2 |

| pRS406DE-CBH | Cell surface display of CBH II with EGFP, URA3 |

| pRS403Dm-BG | Cell surface display of BG I with mCherry, HIS3 |

| pRS405Dm-BG | Cell surface display of BG I with mCherry, LEU2 |

| pRS406Dm-BG | Cell surface display of BG I with mCherry, URA3 |

| Primers | |

| BglII-FLAG-linker-EG-F | 5′-ATGCAGATCTGATTACAAGGATGACGATGACAAGGGTGGATCTACTGTCTGGGGCCAGTGTG-3′ |

| EG-SphI-extra-R | 5′-TGCAGTCGGACGATGCGCATGCCTTTCTTGCGAGACACGAGCTG-3′ |

| BglII-CBH-F | 5′-ATGCAGATCTCAAGCTTGCTCAAGCGTCTGG-3′ |

| CBH-SphI-R | 5′-ATGCGCATGCCAGGAACGATGGGTTTGCGTTTG-3′ |

| SphI-EGFP-F | 5′-ATGCGCATGCGGTGGATCTGGTGGCGTGA-3′ |

| EGFP-SphI-R | 5′-ATGCGCATGCCTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGCC-3′ |

| NotI-BG-F | 5′-ATGCGCGGCCGCGATGAACTGGCGTTCTCTCCTC-3′ |

| BG-SphI-R | 5′-ATGCGCATGCTTGCACCTTCGGGAGCGC-3′ |

| SphI-5linker-mCherry-F | 5′-ATGCGCATGCGGTGGATCTGGTGGCGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAG-3′ |

| mCherry-SphI-R | 5′-ATGCGCATGCCTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGCC-3′ |

| infusion GAPDH promoter F | 5′-CGGGCCCCCCCTCGAGACCAGTTCTCACACGGAACAC-3′ |

| infusion GAPDH terminator R | 5′-ACCGCGGTGGCGGCCGCTTTGATTATGTTCTTTCTATTTGAATGAGATATGA-3′ |

Underlined sequences are restriction enzyme sites.

The T. reesei CBH II gene in pCBH (12) was PCR amplified using the BglII-CBH-F and CBH-SphI-R primers. The amplified CBH DNA fragment was inserted into pRS426display (12), which was cut using BglII and SphI, and the resulting plasmid was named pRS426D-CBH. The enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) gene present in pULSG1 (13) was PCR amplified using the SphI-EGFP-F and EGFP-SphI-R primers, and the amplified EGFP DNA fragment was inserted into the pRS426D-CBH plasmid, which was cut using SphI. The resulting plasmid was named pRS426DE-CBH.

The A. aculeatus BG I gene in pBG (12) was PCR amplified using the NotI-BG-F and BG-SphI-R primers. The amplified BG I gene fragment was inserted in a plasmid that was constructed as follows. The sequence encoding the GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) promoter, the secretion signal of glucoamylase from Rhizopus oryzae, the multicloning site, the Strep-tag, and the C-terminal region of α-agglutinin, which are present in pRS426display, were inserted into the SalI-SacII section of pRS423 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) after digestion with SalI and SacII. The resulting plasmid was named pRS423display. The amplified BG I gene fragment was inserted into pRS423display, and this plasmid was named pRS423D-BG. The mCherry gene present in pmCherry-N1 (Clontech, CA, USA) was PCR amplified using the SphI-5linker-mCherry-F and mCherry-SphI-R primers, and the fragment was inserted into pRS423D-BG that had been cut using SphI. The resulting plasmid was named pRS423Dm-BG.

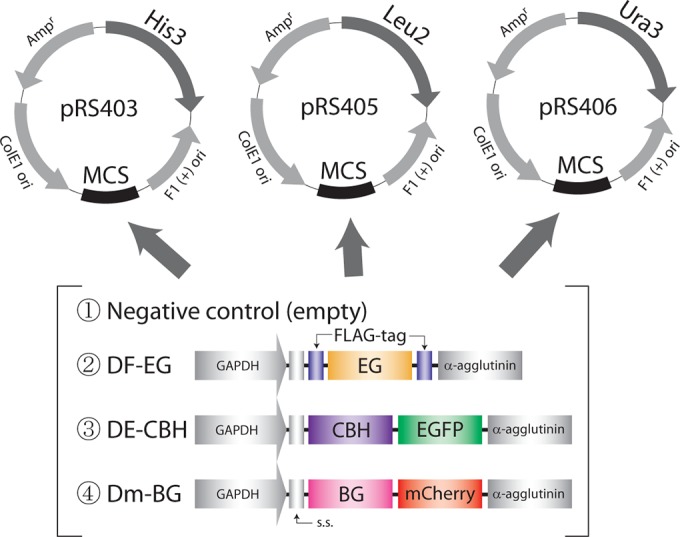

The gene cassettes used for the cell surface display of FLAG-EG, CBH-EGFP, and BG-mCherry (GAPDH promoter, secretion signal of glucoamylase, the cellulase containing a polypeptide tag or a fluorescence protein, and the C-terminal region of α-agglutinin) were amplified with the infusion GAPDH promoter F and infusion GAPDH terminator R primers (Table 1). Each of the amplified fragments was inserted into the each of the 3 plasmids pRS403, pRS405, and pRS406 (American Type Culture Collection), which were cut using XhoI and NotI; thus, we constructed the 9 plasmids that were used for genome integration (Table 1).

Strains and media.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae wild-type strain W303-1A (MATa leu2-3/112 ura3-1 trp1-1 his3-11/15 ade2-1 can1-100) was used for cell surface display. The cellulase-displaying yeast strains constructed in this study are listed in Table 2. Because W303-1A is colored red because of the accumulation of the adenine precursor, the strain was transformed with pRS402; this eliminated the red color and allowed the mCherry fluorescence to be observed. Yeast transformants were aerobically cultivated in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium (1% [wt/vol] yeast extract, 2% glucose, 2% peptone) that was buffered at pH 6.0 with 50 mM 2-morpholinoethanesulfonic acid (MES). Escherichia coli DH5α [F− ϕ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) phoA supE44 λ− thi-1 gyrA96 relA1] was used as a host for manipulating recombinant DNA, and this strain was grown in Luria-Bertani medium (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% sodium chloride) containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin.

TABLE 2.

Constructed yeast strains

| Namea | Introduced plasmids |

|---|---|

| Cont-yeast | pRS402, pRS403, pRS405, pRS406 |

| EG-yeast | pRS402, pRS403DF-EG, pRS405DF-EG, pRS406DF-EG |

| CBH-yeast | pRS402, pRS403DE-CBH, pRS405DE-CBH, pRS406DE-CBH |

| BG-yeast | pRS402, pRS403Dm-BG, pRS405Dm-BG, pRS406Dm-BG |

| ALL-yeast | pRS402, pRS403Dm-BG, pRS405DF-EG, pRS406DE-CBH |

Cont-yeast, a yeast strain that displays no cellulase; EG-yeast, a yeast strain that displays only endoglucanase (EG); CBH-yeast, a yeast strain that displays only cellobiohydrolase (CBH); BG-yeast, a yeast strain that displays only β-glucosidase (BG); ALL-yeast, a yeast strain that simultaneously displays EG, CBH, and BG. MIX-yeast was prepared by mixing EG-yeast, CBH-yeast, and BG-yeast.

Immunostaining and microscopic examination of the 5 yeast strains.

All cellulase-displaying yeast strains were precultivated for 24 h at 30°C in YPD medium, to inoculate the same number of yeast cells for the main cultivation, and cultivated for 72 h at 30°C in YPD medium in all the following experiments.

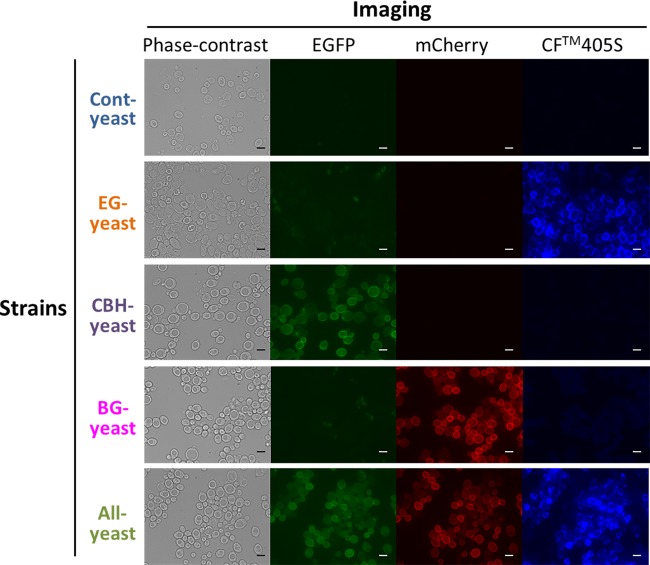

After the cultivation, yeast cells of the 5 yeast strains listed in Table 2 were harvested at a concentration equal to the yeast cell number in 1 ml of yeast suspension with an optical density (OD) at 600 nm of 0.5 (OD0.5), washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4), and then used for quantifying the displayed cellulases. The cell pellets were resuspended using 50 μl of PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin, and then the yeast cell suspensions were incubated on a rotary shaker; all incubations in this experiment were carried out at room temperature. After the suspensions were incubated for 30 min, 1 μl of an anti-FLAG mouse monoclonal primary antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to them. Subsequently, they were incubated for 1.5 h and then were washed twice with PBS. The precipitates were resuspended in 50 μl of PBS, and then we added 8 μl of CF405S-conjugated goat antimouse monoclonal secondary antibodies (Biotium, Hayward, CA, USA) and incubated the cell suspensions for another 1.5 h. After the incubation, the suspensions were washed twice with PBS and the precipitates were resuspended using 40 μl of PBS. These immunostained yeast strains were examined under an inverted microscope (IX71; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The green fluorescence of EGFP was detected through a U-MNIBA2 mirror unit containing a BP470-490 excitation filter, a DM505 dichroic mirror, and a BA510-550 emission filter (Olympus). The red fluorescence of mCherry was detected through a U-MWIG2 mirror unit containing a BP520-550 excitation filter, a DM565 dichroic mirror, and a BA580IF emission filter (Olympus). The blue fluorescence of the CF405S fluorophore was detected through a U-MNUA2 mirror unit containing a BP360-370 excitation filter, a DM400 dichroic mirror, and a BA420-460 emission filter (Olympus).

Fluorometric analysis.

After immunofluorescence labeling, the yeast cells were suspended in 200 μl of PBS in 96-well black plates (catalog number 353945; BD Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and the fluorescence of the cells was measured using a Fluoroskan Ascent fluorometer (Labsystems OY, Helsinki, Finland). Filter pairs of 355/460 nm, 485/510 nm, and 584/612 nm were used for detecting the fluorescence of CF405S, EGFP, and mCherry, respectively.

Cellulase activity assay.

BG activity was measured using 20 mM p-nitrophenyl glucopyranoside (PNPG; 30.125 mg/5 ml) as a substrate. OD0.05 yeast cells were collected by centrifuging them for 1 min at 12,000 × g and then washed once with a 50 mM citrate buffer. The cell pellet was resuspended using 750 μl of the 50 mM citrate buffer, and the suspension was incubated in a heat block at 50°C for 30 min. The PNPG solution was also incubated at 50°C for 30 min, and 250 μl of this solution was added to the yeast suspension to start the reaction. During the reaction, samples were withdrawn at 5, 10, and 15 min and mixed with 0.2 M Na2CO3 in a 1:1 ratio, and 200 μl of the mixed solution was used for measuring the A400 using a Fluoroskan Ascent fluorometer and the 96-well black plates mentioned in the preceding paragraph.

EG and CBH activities and cellulase proximity effects were measured using 1% PASC (14) as a substrate. OD10 or OD0.1 yeast cells were collected and washed once with the 50 mM citrate buffer. The cell pellet was resuspended using 500 μl of a 100 mM citrate buffer and incubated in a heat block at 50°C for 1 h, after which 500 μl of 2% PASC was added to start the reaction (which was performed at 50°C). Reaction samples were withdrawn at 6, 12, 24, and 48 h of incubation in the case of OD10 yeast cells and at 24, 48, 84, and 120 h of incubation in the case of OD0.1 yeast cells, and then the supernatants were mixed with 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) solution (NaOH, 16 g/liter; potassium sodium tartrate, 300 g/liter; DNS, 5 g/liter) in a 1:2 ratio to quantify the reduced ends of the degraded products. The mixed solutions were incubated at 100°C for 5 min, and after cooling them to room temperature, 200 μl of each solution was used for measuring the A530 using the Fluoroskan Ascent fluorometer and 96-well black plates.

RESULTS

Construction of a yeast strain that simultaneously displays 3 kinds of cellulose-degrading enzymes on the cell surface.

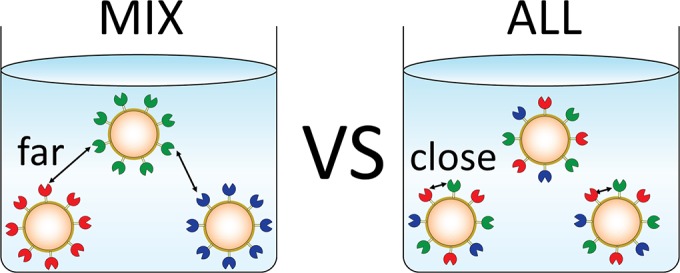

To demonstrate that the 3 kinds of cellulases displayed on the yeast cell surface, EG, CBH, and BG, degrade cellulose synergistically (Fig. 1), we constructed these 5 yeast strains: Cont-yeast (yeast displaying no cellulases), EG-yeast (yeast displaying FLAG-tagged EG), CBH-yeast (yeast displaying CBH fused with EGFP), BG-yeast (yeast displaying BG fused with mCherry), and ALL-yeast (yeast simultaneously displaying EG-FLAG, CBH-EGFP, and BG-mCherry) (Table 2). We constructed 13 plasmids that were used for the display (Fig. 2), and these plasmids were transformed into the yeast S. cerevisiae W303-1A strain to obtain the aforementioned 5 yeast strains (Tables 1 and 2). To readily visualize and quantify the displayed cellulases, EGFP and mCherry were fused with CBH and BG, respectively; in the case of EG, the attached FLAG tag was detected by immunostaining.

FIG 1.

Schematic illustration of experiments conducted to demonstrate the proximity effect between cellulases displayed on the surface of yeast cells. MIX-yeast is a mixture of 3 single-cellulase-displaying yeasts, EG-yeast (for example, blue), CBH-yeast (green), and BG-yeast (red), which are listed in Table 2. MIX-yeast was prepared by mixing the 3 single-cellulase-displaying yeasts in a ratio corresponding to the display ratio of ALL-yeast. The proximity effect between the cellulases displayed on ALL-yeast, which simultaneously displays EG, CBH, and BG, was determined by comparing the PASC-degrading activity of ALL-yeast and MIX-yeast.

FIG 2.

Maps of the plasmids used for generating the 5 cellulase-displaying yeast strains. The 3 gene cassettes DF-EG, DE-CBH, and Dm-BG were constructed and inserted into pRS403, pRS405, and pRS406. D, display; F, FLAG tag; E, EGFP; m, mCherry; s.s., signal sequence. All of the plasmids were introduced into the yeasts listed in Table 2. Genes encoding the FLAG tag, EGFP, and mCherry were fused with the cellulase genes to visualize and quantify the displayed cellulases.

To confirm that the 5 yeast strains displayed each of the cellulases properly, we immunostained the yeast cells by using an anti-FLAG primary antibody and a CF405S-conjugated antimouse secondary antibody. The blue fluorescence of CF405S, the green fluorescence of EGFP, and the red fluorescence of mCherry were observed under a fluorescence microscope (Fig. 3). This microscopic analysis revealed that whereas Cont-yeast exhibited no fluorescence, EG-yeast fluoresced blue, CBH-yeast fluoresced green, BG-yeast fluoresced red, and ALL-yeast exhibited fluorescence in all 3 colors. Notably, almost 100% of EG-, CBH-, BG-, and ALL-yeast cells displayed cellulases. These results indicate that ALL-yeast simultaneously displayed the 3 kinds of cellulases and that all 5 yeast strains were successfully constructed.

FIG 3.

Confirmation of cellulase display by immunostaining and fluorescence microscopy. Cells of 5 yeast strains were immunostained using an anti-FLAG mouse monoclonal primary antibody and CF405S-conjugated goat antimouse monoclonal secondary antibodies. Fluorescence microscopy was used to examine the fluorescence of EGFP on CBH-yeast and ALL-yeast, CF405S on EG-yeast and ALL-yeast, and mCherry on BG-yeast and ALL-yeast. Bars = 5 μm.

Confirmation of cellulase activities of the 5 yeast strains constructed.

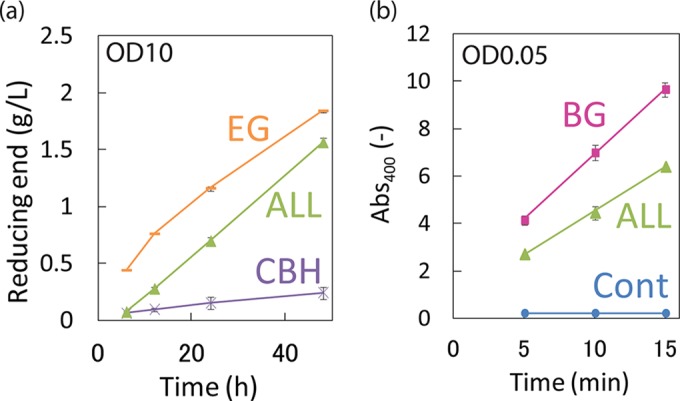

After constructing the 5 yeast strains, we examined their cellulase activities to measure the PASC-degrading activities of EG-yeast, CBH-yeast, and ALL-yeast or used PNPG to measure the BG activities of BG-yeast and ALL-yeast. All 5 yeast strains were incubated at 50°C for 1 h to kill and prevent ALL-yeast from ingesting the produced glucose before the reaction. Incubation at 50°C does not affect the activity of the displayed cellulases because their optimal temperature is 50°C. After this inactivation step, we confirmed that glucose was not consumed by ALL-yeast during the reaction (data not shown). The results presented in Fig. 4 show that all of the constructed yeast strains exhibited their specific activities. Notably, the PASC-degrading activity of EG-yeast decreased slightly over time, whereas that of ALL-yeast was exactly proportional to the time course (Fig. 4a); this result suggests that whereas the EG displayed on EG-yeast was inhibited by the degradation products generated from PASC (e.g., cellobiose), the glucose-tolerant BG that was displayed on ALL-yeast degraded oligosaccharides to glucose, and thus, the EG activity of ALL-yeast was not inhibited.

FIG 4.

Confirmation of the PASC-degrading activity and BG activity of the 5 cellulase-displaying yeast strains. (a) The PASC-degrading (reducing-end) activities of EG and CBH displayed on EG-yeast, CBH-yeast, and ALL-yeast were measured. Yeast cells were used at a concentration of OD10 in the reaction mixture. The PASC-degrading activity of Cont-yeast was subtracted from the activities measured for EG-yeast, CBH-yeast, and ALL-yeast, and the values obtained are plotted here. (b) BG activities (absorbance at 400 nm [Abs400]) of BG displayed on BG-yeast and ALL-yeast were measured using PNPG as a substrate. Yeast cells were used at a concentration of OD0.05 in the reaction mixture. The reactions were performed at 50°C, and the yeasts were incubated at 50°C for 1 h before the reaction started to prevent ALL-yeast from taking up the produced glucose. The data represent the reducing ends (g/liter [L]) generated by the yeast strains in the PASC-degrading reaction, and the average ± standard deviation from 3 independent experiments is shown.

Determination of amounts of the displayed cellulases and their proximity effect.

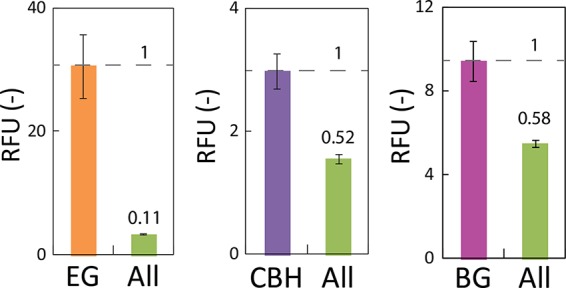

To compare the cellulase activity of ALL-yeast with that of MIX-yeast, which was a mixture of single-cellulase-displaying yeasts (Fig. 1), we had to quantify and adjust the amount of the cellulases used in the reaction mixture. First, the amount of EG displayed on EG-yeast and ALL-yeast was quantified by measuring the fluorescence intensity after immunostaining, and it was 1:0.11 (Fig. 5). Next, the fluorescence intensity of EGFP was measured to quantify the CBH displayed on CBH-yeast and ALL-yeast, and the ratio was 1:0.52. Finally, the fluorescence intensity of mCherry was measured to quantify the BG displayed on BG-yeast and ALL-yeast, and the ratio was 1:0.58.

FIG 5.

Comparison of the amounts of cellulases displayed on ALL-yeast and EG-, CBH-, or BG-yeast. The amounts of the displayed cellulases were determined by measuring the fluorescence after immunostaining. Filter pairs of 355/460 nm, 485/510 nm, and 584/612 nm were used to quantify the fluorescence of CF405S, EGFP, and mCherry, respectively. The data represent the relative fluorescence unit (RFU) values of the yeast strains, and the average ± standard deviation from 3 independent experiments is shown.

The BG activity of BG-yeast was approximately 1.6 times higher than that of ALL-yeast (Fig. 4b). Because EG-yeast and CBH-yeast did not exhibit any activity toward PNPG, this result suggests that the ratio of the activity corresponds to the ratio of the amount of the enzymes displayed on BG-yeast and ALL-yeast. As the display ratio calculated for BG on BG-yeast/ALL-yeast on the basis of the fluorescence intensity was almost the same as the ratio determined from the PNPG assay, it indicates that the display ratio calculated from the fluorescence intensity is reliable.

MIX-yeast was prepared by mixing the 3 single-cellulase-displaying yeasts in the aforementioned ratios: MIX-yeast was composed of OD1.1 EG-yeast cells, OD5.2 CBH-yeast cells, and OD5.8 BG-yeast cells; thus, the total amount of the cellulases derived from MIX-yeast and ALL-yeast used was the same. Because the total amount of MIX-yeast added up to OD12.1, we added OD2.1 Cont-yeast cells to OD10 ALL-yeast cells to adjust the total amount of yeast cells. ALL-yeast or MIX-yeast was mixed with PASC, and their PASC-degrading activities were compared. The activity of ALL-yeast was 1.25-fold higher than that of MIX-yeast, which suggests that the cellulases simultaneously displayed on ALL-yeast synergistically degraded PASC (Fig. 6a). Based on this result, we surmised that the distance between the different kinds of cellulases (i.e., the distance between yeast cells in the case of MIX-yeast versus the distance between cellulases on single yeast cells in the case of ALL-yeast) was critical for the synergistic reaction between the cellulases; this is because the distance between the cellulases in ALL-yeast is substantially shorter than that in MIX-yeast (Fig. 1).

FIG 6.

Proximity effect between cellulases displayed on ALL-yeast. MIX-yeast was prepared on the basis of the ratio of the amount of each cellulase displayed on ALL-yeast to that displayed on the single-cellulase-displaying yeast strains. (a) Yeast cells were used at OD10 in the reaction mixture. For MIX-yeast, OD1.1 EG-yeast cells, OD5.2 CBH-yeast cells, and OD5.8 BG-yeast cells were used; for ALL-yeast, OD2.1 Cont-yeast cells and OD10 ALL-yeast cells were used. (b) OD0.1 yeast cells were used in the reaction mixture. At this lower yeast concentration, the distance between yeast cells was greater than that when OD10 yeast cells were used, and, consequently, the distance between the different kinds of cellulases in MIX-yeast was greater at OD0.1 than at OD10. To obtain OD0.1 yeast cells, OD10 MIX-yeast cells and OD10 ALL-yeast cells were diluted 100-fold. The yeast strains were used in reaction mixtures containing 1% PASC, and the reducing ends of the degraded products were quantified using the DNS assay. The data represent the reducing ends (g/liter [L]) generated by the yeast strains in the PASC-degrading reaction; the average ± standard deviation from 3 independent experiments is shown. **, P < 0.01, calculated using the data at the endpoint and t tests. ALL-yeast showed 1.25-fold (a) or 2.22-fold (b) higher PASC-degrading activity. The activity of Cont-yeast was subtracted from the activities of ALL-yeast and MIX-yeast, and the data were plotted.

We conducted an additional experiment to support the proximity effect (i.e., to demonstrate that increased PASC-degrading activity is related to the distance between cellulases). The amount of yeast cells used in the PASC-degrading reaction was lowered to OD0.1 for the purpose of further increasing the distance between cellulases in MIX-yeast while maintaining the same distance between the cellulases in ALL-yeast. At OD0.1, relative to the PASC-degrading activity of MIX-yeast, ALL-yeast exhibited even higher (2.22-fold higher) PASC-degrading activity than it did when the activities of these yeasts were measured at OD10 (Fig. 6b). The difference in PASC-degrading activity between ALL-yeast and MIX-yeast at the low concentration was approximately 5-fold greater than that when the high concentration of yeast was used. This result suggests that the proximity effect functioned in enhancing PASC degradation by the 3 kinds of cellulases displayed on ALL-yeast.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we successfully constructed a yeast strain that simultaneously displays 3 kinds of cellulases and demonstrated that the simultaneous display promoted a synergistic reaction between the different kinds of cellulases (the proximity effect). More specifically, simultaneous display and the proximity effect were demonstrated after adjusting the amounts of the displayed enzymes by using arming yeast. Previous reports have indicated that a yeast strain that simultaneously displays several kinds of enzymes exhibits higher activity than a mixture of single-enzyme-displaying yeast strains; however, the amounts of the displayed enzymes were not determined, and thus, the amount of the enzymes used was not adjusted (11, 15).

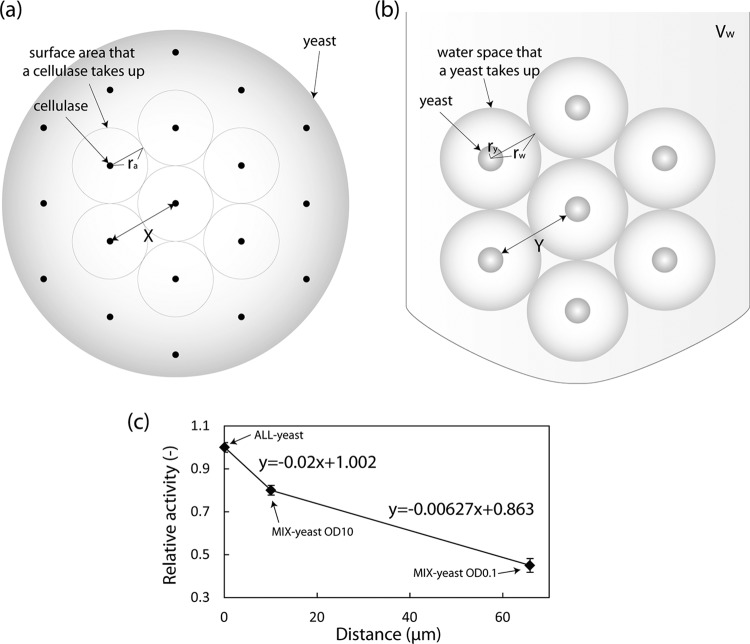

The distances between different kinds of cellulases in ALL-yeast and MIX-yeast were calculated approximately to analyze the relationship between the distance and the proximity effect. We hypothesized that the cellulases are evenly distributed on the cell surface of yeast, and we set the area or the volume occupied by a displayed cellulase or a yeast cell to be a circle or a sphere, respectively, to simplify the calculations (Fig. 7). Equations 1 and 2, provided below, were used for calculating the distance between the 3 cellulases in ALL-yeast, and equations 3 to 5 were used for calculating the distance between the cellulases in MIX-yeast.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

FIG 7.

Approximate calculation of the distance between cellulases in ALL-yeast and MIX-yeast and the relationship between distance and the proximity effect. (a) The distance between the different kinds of cellulases displayed on ALL-yeast (X) was calculated. The area occupied by a displayed cellulase was set to be a circle to simplify the calculation. ra, radius of the area that a displayed cellulase occupies. (b) The distance between the different kinds of cellulases displayed on MIX-yeast (Y) was calculated. The volume occupied by a yeast cell was set to be a sphere to simplify the calculation. rw is the radius of the water space that a yeast cell occupies; Vw, the total volume of water used in the reaction mixture, was 1 ml (10−6 m3); and ry, the radius of a yeast cell, was 2.5 μm. (c) The relative activities of ALL-yeast and MIX-yeast in PASC degradation are plotted against the distance between cellulases.

The variables are the following: ra is the putative radius of the area that a displayed cellulase occupies; ry, the putative radius of a yeast cell, is equal to 2.5 μm; nd, the total number of displayed cellulases on the surface of a yeast cell (16), is equal to 104; X is the putative distance between the 3 kinds of cellulases displayed on ALL-yeast; rw is the putative radius of the surrounding space that a yeast cell occupies; Vw, the total volume of water used in the reaction mixture, is equal to 1 ml (10−6 m3); ny, the number of yeast cells used in the reaction mixture, is 5.55 × 108 (OD10) or 5.55 × 106 (OD0.1); and Y is the putative distance between the different kinds of cellulases displayed on MIX-yeast.

The distance between the 3 kinds of cellulases in ALL-yeast was 0.1 μm, and the distance in MIX-yeast, which is equal to the distance between yeast cells, was 10.1 μm in case of OD10 and 65.1 μm in case of OD0.1 (Table 3). Relative activity was calculated by dividing the reducing-end value of ALL-yeast or MIX-yeast at the endpoint (48 h for OD10 and 120 h for OD0.1) by the value of ALL-yeast. Our results showed that the proximity effect increased when the distance was shortened (Fig. 7c). Furthermore, the absolute value of the gradient between 0.1 and 10.1 μm (0.02) was >3-fold higher than that between 10.1 and 65.1 μm (0.00627), which implies that the proximity effect changes more drastically when the distance range shrinks.

TABLE 3.

Relationship between distance and proximity effecta

| Strain (concn) | Distanceb (μm) | Relative activityc |

|---|---|---|

| ALL-yeast | 0.100 | 1.00 ± 0.02 |

| MIX-yeast (OD10) | 10.1 | 0.80 ± 0.02 |

| MIX-yeast (OD0.1) | 65.9 | 0.45 ± 0.03 |

Reducing-end values at 48 and 120 h were used in the calculation for the OD10 and OD0.1 samples, respectively.

The distance between the different kinds of cellulases. To calculate the distance approximately, we set the variables of the radius of the yeasts, the amount of total displayed cellulases, and the number of cells in an OD1 yeast cell culture to be 2.5 μm (putative), 104 cellulases/yeast cell (from a previous study [16]), and 5.55 × 107 (counted), respectively.

Relative activity is (reducing-end value at endpoint of MIX-yeast or ALL-yeast)/(reducing-end value at endpoint of ALL-yeast).

We have found that the distance between cellulases is critical for the occurrence of the synergistic reaction: the strength of the proximity effect increased with a decrease in the distance between the different kinds of cellulases, and the proximity effect increased more sharply at shorter distances than at longer distances (Fig. 7). These results suggest that enhancing the display efficiency would lead to an increased proximity effect because the distance between the displayed cellulases would be decreased. In the development of arming technology, substantial effort has been devoted to improving the display efficiency mainly by using 3 strategies. First, display can be enhanced by integrating increased numbers of genes; this can be achieved by inserting 2 or 3 cassettes of genes into a plasmid or by means of δ-integration (17). Yamada et al. (18) reported a cocktail δ-integration method that they used to successfully insert multiple genes and readily optimize the ratio of displayed cellulases, which resulted in an increase in cellulose-degrading activity. Second, disruption of cell wall proteins or proteins related to cell wall formation can increase display efficiency. SED1 is a major structural cell wall protein expressed in the stationary phase (19), and it is considered to compete with α-agglutinin for cell surface display. A SED1-disrupted yeast strain which showed increased display efficiency, particularly during the stationary growth phase, was constructed previously (20, 21). Moreover, Matsuoka et al. (22) reported that the disruption of the MNN2 gene, which encodes α-1,2-mannosyltransferase, increased the overall display efficiency but did so particularly on the outer surface, where high-molecular-weight substrates can bind. Third, the gene promoter or enzyme-anchoring domain used can be changed to enhance display (23). In this study, we used the GAPDH promoter and the α-agglutinin C-terminal anchor domain. In a recent study, the GAPDH promoter and the α-agglutinin anchor domain were replaced with the SED1 promoter and the SED1 anchor domain, respectively; the promoter replacement increased the overall display efficiency, and the anchor domain replacement increased the display efficiency on the outer surface. Using these strategies to enhance the display efficiency is expected to lead not only to an increase in the total amounts of displayed cellulases but also to an increase in the proximity effect.

We have demonstrated the proximity effect of arming yeast on PASC, but whether it shows the proximity effect on Avicel is also an interesting issue. Krauss et al. (24) reported that the addition of scaffoldin to the scaffoldin-disrupted C. thermocellum culture supernatant increased the cellulase activity only when Avicel was used as a substrate, whereas it did not differ greatly when PASC or soluble cellulose was used, which suggests an exclusive proximity effect on Avicel. From this report, we expected that the arming yeast would show an even greater proximity effect on Avicel and we measured the Avicel-degrading activity of MIX-yeast and ALL-yeast (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Although the Avicel-degrading activity of MIX-yeast was not high enough to be detected, ALL-yeast showed significantly higher Avicel-degrading activity than MIX-yeast, which suggests that the cellulases displayed on ALL-yeast degraded Avicel synergistically and the proximity effect could be even greater than that on PASC.

Arming yeasts offer the advantageous feature of serving as a biocatalyst of cellulose degradation, and, additionally, these cellulase-displaying yeasts can be used to further study the proximity effect. Studies on cellulosomes have yielded unexpected results showing that decreasing the distance between cellulases in the cellulosome does not necessarily lead to increased cellulose-degrading activity (25, 26); this was unexpected because of the lack of information on the natural fine structure of the cellulosome. In the previous study in which a designed minicellulosome was used, the proximity effects of cellulases at various distances were evaluated (25). The lengths of the linkers between cohesins (domains in the scaffoldin structure of the cellulosome that cellulases can bind to) were varied using, for example, 0, 5, or approximately 30 amino acids, and the designed minicellulosome featuring the shortest linker exhibited the lowest cellulose-degrading activity because of the conformational constraint and steric hindrance between the cellulases. Moreover, a similar cellulose-degrading activity was reported when a linker length of up to 128 amino acids was used, even though the distance between the cellulases increased (26).

A 30-amino-acid linker is estimated to be about 10 nm long. In our study, the distance between the cellulases in ALL-yeast was calculated to be 100 to 10 nm when the display efficiency was 104 to 105 per cell. This distance is comparable to the distance between cellulases in the minicellulosome. Further investigation of the proximity effect at this close range conducted by using arming yeast could provide valuable insights into the proximity effect and conformational constraints when combined with the results of cellulosome analysis (27).

In conclusion, we have successfully constructed an ALL-yeast strain that simultaneously displays 3 kinds of cellulases and have determined that ALL-yeast exhibited higher PASC-degrading activity than MIX-yeast did when the same amount of cellulases was used, which demonstrates the proximity effect. Because the proximity effect increased more drastically when the distances between the cellulases decreased, further increasing the cellulase display efficiency could enhance the proximity effect and, thus, cellulose-degrading activity. We expect that combining proximity effect studies conducted in various contexts, such as by using arming yeast and cellulosomes, will provide key insights that could facilitate the development of novel strategies for efficiently degrading cellulose and for enabling synergistic and continuous reactions in several other fields.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02864-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Klemm D, Heublein B, Fink HP, Bohn A. 2005. Cellulose: fascinating biopolymer and sustainable raw material. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 44:3358–3393. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carroll A, Somerville C. 2009. Cellulosic biofuels. Annu Rev Plant Biol 60:165–182. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.043008.092125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lynd LR, Weimer PJ, van Zyl WH, Pretorius IS. 2002. Microbial cellulose utilization: fundamentals and biotechnology. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 66:506–577. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.3.506-577.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lynd LR, Laser MS, Bransby D, Dale BE, Davison B, Hamilton R, Himmel M, Keller M, McMillan JD, Sheehan J, Wyman CE. 2008. How biotech can transform biofuels. Nat Biotechnol 26:169–172. doi: 10.1038/nbt0208-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jalak J, Kurasin M, Teugjas H, Valjamae P. 2012. Endo-exo synergism in cellulose hydrolysis revisited. J Biol Chem 287:28802–28815. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.381624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamaru Y, Karita S, Ibrahim A, Chan H, Doi RH. 2000. A large gene cluster for the Clostridium cellulovorans cellulosome. J Bacteriol 182:5906–5910. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.20.5906-5910.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamed R, Setter E, Bayer EA. 1983. Characterization of a cellulose-binding, cellulase-containing complex in Clostridium thermocellum. J Bacteriol 156:828–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson EA, Sakajoh M, Halliwell G, Madia A, Demain AL. 1982. Saccharification of complex cellulosic substrates by the cellulase system from Clostridium thermocellum. Appl Environ Microbiol 43:1125–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fierobe HP, Bayer EA, Tardif C, Czjzek M, Mechaly A, Belaich A, Lamed R, Shoham Y, Belaich JP. 2002. Degradation of cellulose substrates by cellulosome chimeras. Substrate targeting versus proximity of enzyme components. J Biol Chem 277:49621–49630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207672200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morais S, Barak Y, Caspi J, Hadar Y, Lamed R, Shoham Y, Wilson DB, Bayer EA. 2010. Cellulase-xylanase synergy in designer cellulosomes for enhanced degradation of a complex cellulosic substrate. mBio 1(5):e00285-10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00285-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujita Y, Ito J, Ueda M, Fukuda H, Kondo A. 2004. Synergistic saccharification, and direct fermentation to ethanol, of amorphous cellulose by use of an engineered yeast strain codisplaying three types of cellulolytic enzyme. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:1207–1212. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.2.1207-1212.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakanishi A, Kuroda K, Ueda M. 2012. Direct fermentation of newspaper after laccase-treatment using yeast codisplaying endoglucanase, cellobiohydrolase, and β-glucosidase. Renew Energ 44:199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2012.01.078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsui K, Kuroda K, Ueda M. 2009. Creation of a novel peptide endowing yeasts with acid tolerance using yeast cell-surface engineering. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 82:105–113. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1761-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang YH, Cui J, Lynd LR, Kuang LR. 2006. A transition from cellulose swelling to cellulose dissolution by o-phosphoric acid: evidence from enzymatic hydrolysis and supramolecular structure. Biomacromolecules 7:644–648. doi: 10.1021/bm050799c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakatani Y, Yamada R, Ogino C, Kondo A. 2013. Synergetic effect of yeast cell-surface expression of cellulase and expansin-like protein on direct ethanol production from cellulose. Microb Cell Fact 12:66. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-12-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shibasaki S, Ueda M, Iizuka T, Hirayama M, Ikeda Y, Kamasawa N, Osumi M, Tanaka A. 2001. Quantitative evaluation of the enhanced green fluorescent protein displayed on the cell surface of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by fluorometric and confocal laser scanning microscopic analyses. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 55:471–475. doi: 10.1007/s002530000539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakai A, Shimizu Y, Hishinuma F. 1990. Integration of heterologous genes into the chromosome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae using a delta sequence of yeast retrotransposon Ty. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 33:302–306. doi: 10.1007/BF00164526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamada R, Taniguchi N, Tanaka T, Ogino C, Fukuda H, Kondo A. 2010. Cocktail δ-integration: a novel method to construct cellulolytic enzyme expression ratio-optimized yeast strains. Microb Cell Fact 9:32. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-9-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimoi H, Kitagaki H, Ohmori H, Iimura Y, Ito K. 1998. Sed1p is a major cell wall protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in the stationary phase and is involved in lytic enzyme resistance. J Bacteriol 180:3381–3387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuroda K, Matsui K, Higuchi S, Kotaka A, Sahara H, Hata Y, Ueda M. 2009. Enhancement of display efficiency in yeast display system by vector engineering and gene disruption. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 82:713–719. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1808-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotaka A, Sahara H, Kuroda K, Kondo A, Ueda M, Hata Y. 2010. Enhancement of β-glucosidase activity on the cell-surface of sake yeast by disruption of SED1. J Biosci Bioeng 109:442–446. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsuoka H, Hashimoto K, Saijo A, Takada Y, Kondo A, Ueda M, Ooshima H, Tachibana T, Azuma M. 2014. Cell wall structure suitable for surface display of proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 31:67–76. doi: 10.1002/yea.2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inokuma K, Hasunuma T, Kondo A. 2014. Efficient yeast cell-surface display of exo- and endo-cellulase using the SED1 anchoring region and its original promoter. Biotechnol Biofuels 7:8. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-7-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krauss J, Zverlov VV, Schwarz WH. 2012. In vitro reconstitution of the complete Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome and synergistic activity on crystalline cellulose. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:4301–4307. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07959-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vazana Y, Barak Y, Unger T, Peleg Y, Shamshoum M, Ben-Yehezkel T, Mazor Y, Shapiro E, Lamed R, Bayer EA. 2013. A synthetic biology approach for evaluating the functional contribution of designer cellulosome components to deconstruction of cellulosic substrates. Biotechnol Biofuels 6:182. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-6-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molinier AL, Nouailler M, Valette O, Tardif C, Receveur-Brechot V, Fierobe HP. 2011. Synergy, structure and conformational flexibility of hybrid cellulosomes displaying various inter-cohesins linkers. J Mol Biol 405:143–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bae J, Morisaka H, Kuroda K, Ueda M. 2013. Cellulosome complexes: natural biocatalysts as arming microcompartments of enzymes. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 23:370–378. doi: 10.1159/000351358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.