Abstract

Background

Treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) with the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) imatinib significantly improves patient outcomes. As some patients are unresponsive to imatinib, next generation BCR-ABL inhibitors such as nilotinib have been developed to treat patients with imatinib-resistant CML. The use of some BCR-ABL inhibitors has been associated with bleeding diathesis, and these inhibitors have been shown to inhibit platelet functions, which may explain the hemostasis impairment. Surprisingly, a new TKI, ponatinib, has been associated with a high incidence of severe acute ischemic cardiovascular events. The mechanism of this unexpected adverse effect remains undefined.

Objective and Methods

This study used biochemical and functional assays to evaluate whether ponatinib was different from the other BCR-ABL inhibitors with respect to platelet activation, spreading, and aggregation.

Results and Conclusions

Our results show that ponatinib, similar to other TKIs, acts as a platelet antagonist. Ponatinib inhibited platelet activation, spreading, granule secretion, and aggregation, likely through broad spectrum inhibition of platelet tyrosine kinase signaling, and also inhibited platelet aggregate formation in whole blood under shear. As our results indicate that pobatinib inhibits platelet function, the adverse cardiovascular events observed in patients taking ponatinib may be the result of the effect of ponatinib on other organs or cell types or disease-specific processes, such as BCR-ABL+ cells undergoing apoptosis in response to chemotherapy, or drug-induced adverse effects on the integrity of the vascular endothelium in ponatinib-treated patients.

Keywords: Platelets, Tyrosine Kinase, Thrombosis, Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia

Introduction

The BCR-ABL gene, which is detected in 95% of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) patients, is a product of reciprocal translocation between the long arms of chromosomes 9 and 22 [1]. When translated, BCR-ABL mRNA produces a protein with elevated tyrosine kinase activity that has been linked to specific pathologic defects characteristic of CML, notably a massive increase in myeloid cell numbers due to increased proliferation and decreased apoptosis of a hematopoietic stem cell or progenitor cell, defects in adherence of myeloid progenitors to marrow stroma leading to the release of immature progenitors into circulation, and disease progression resulting from genetic instability. BCR-ABL inhibitors were developed as a treatment for CML. Imatinib, which competitively inhibits the ATP binding site of BCR-ABL, was the first BCR-ABL inhibitor developed for the treatment of patients with CML. This compound was shown to inhibit the proliferation of myeloid cell lines expressing BCR-ABL or CML blast crisis cell lines [1].

While imatinib significantly improves patient outcomes, follow-on studies found that nearly 20% of patients on imatinib do not exhibit a complete cytogenetic response [1]. As a subset of patients develop resistance to imatinib, second-generation BCR-ABL inhibitors were developed. Nilotinib, an aminopyrimidine derivative, was rationally designed to be more selective against the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase than imatinib, and has been shown to effectively inhibit the growth of 32 of the 33 cells lines containing imatinib-resistant mutations. However, while second generation inhibitors such as nilotinib are active against many imatinib-resistant cells, some BCR-ABL mutations, particularly T315I, result in resistance to these second generation compounds [2-4]. Ponatinib was developed as a third generation pan-BCR-ABL inhibitor to treat CML resistant to the previously existing BCR-ABL inhibitors. Ponatinib has been shown to exhibit potent activity against native, T315I, and most other clinically relevant BCRABL mutants [5]. Ponatinib has also been shown to inhibit a subset of the class III/IV family of receptor tyrosine kinases [6].

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors, including the BCR-ABL inhibitors imatinib and ponatinib, are associated with cardiovascular complications, including bleeding diathesis as well as thrombosis [7]. For instance, hemorrhaging is a common adverse event reported in patients receiving imatinib, and imatinib has been associated with abnormalities in platelet aggregometry testing [8, 9]. While the second-generation inhibitor nilotinib is not commonly associated with bleeding diathesis, the third-generation inhibitor ponatinib can inhibit primary hemostasis even in the absence of thrombocytopenia [7, 8]. In contrast to these bleeding side effects common to BCR-ABL inhibitor chemotherapies, prothrombotic complications observed in patients treated with ponatinib resulted in the temporary suspension of the drug by the FDA in late 2013 [10, 11]. However, the pathogenic mechanisms underlying the cardiovascular events observed in patients taking ponatinib remain ill-defined. To better understand the effects of BCR-ABL inhibitors on the process of thrombus formation, this study investigated the effects of ponatinib and other BCR-ABL inhibitors on the key steps in platelet activation, spreading, and aggregation.

Materials and Methods

List of reagents

Bovine thrombin, fatty-acid free BSA, and all other reagents were from Sigma except for as noted. All BCR-ABL inhibitors (ponatinib, nilotinib, and imatinib) were from Selleck Chemicals. Collagen was from Chrono-Log (Havertown, PA). Collagen-related peptide (CRP) was from R. Farndale (Cambridge University, UK). Human fibrinogen was from Enzyme Research. For flow cytometry experiments, the FITC-conjugated Annexin V was from Life Technologies, CD62P-FITC antibody was from Acris Antibodies, and Alexa Fluor 488-Annexin V was from Life Technologies. Antibodies for Western blotting experiments were from Sigma (α-tubulin), Cell Signaling (Lyn pTyr507, BTK pTyr223, Src pTyr416, LAT pTyr191) and Millipore (4G10).

In vitro platelet studies

To prepare washed human platelets, human venous blood was drawn from healthy volunteers by venipuncture into sodium citrate in accordance with an Oregon Health & Science University IRB-approved protocol. The blood was centrifuged at 200 × g for 20 minutes to obtain platelet rich plasma (PRP). Platelets were isolated from the PRP via centrifugation at 1000 × g for 10 minutes in the presence of prostacyclin (0.1 μg/ml). The platelets were then resuspended in modified HEPES/Tyrode buffer (129 mM NaCl, 0.34 mM Na2HPO4, 2.9 mM KCl, 12 mM NaHCO3, 20 mM HEPES, 5 mM glucose, 1mM MgCl2; pH 7.3) and were subsequently washed once via centrifugation at 1000 × g for 10 minutes in modified HEPES/Tyrode buffer. Platelets were resuspended in modified HEPES/Tyrode buffer to the desired concentration. Static adhesion assays, aggregation studies, and flow cytometry experiments were performed as previously described [12, 13].

Flow cytometry

Purified platelets (2 × 107/m1, 50 μl) were treated with inhibitors as indicated before stimulation with CRP or thrombin in the presence of 1:100 FITC-anti-CD62P or FITC/Alexa Fluor 488-Annexin V to stain surface P-selectin or phosphatidylserine, respectively. For Annexin V samples, buffers were supplemented with 10 mM CaCl2. After 20 min incubation, samples were diluted to 500 μl and analyzed on a FACSCalibur or FACSCanto (Becton Dickinson, USA). Platelets were identified by logarithmic signal amplification for forward and side scatter as previously described [14].

Western blotting

For Western blotting assays, purified human platelets (5×108 /ml) were incubated in 24-well culture plates coated with fibrinogen or fibrillar collagen and blocked with fatty acid-free BSA. After incubation (45 min, 37°C), non-adherent platelets were removed and adherent platelets were washed three times with PBS before lysis into 50 μl Laemmli Sample Buffer (Biorad) supplemented with 200 mM DTT. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with indicated antibodies as previously described [12].

Platelet aggregation

Platelet aggregation studies were performed using 300 μl platelets (2 × 108/ml) treated with inhibitors as indicated. Platelet aggregation was triggered by CRP (3 μg/ml) or thrombin (0.1 U/ml) and monitored under continuous stirring at 1200 rpm at 37°C by measuring changes in light transmission using a PAP-4 aggregometer, as previously described [12].

Platelet aggregate formation under flow

Sodium citrate-anticoagulated blood was treated with inhibitors as indicated and perfused at 2200 s−1 and 37°C through glass capillary tubes coated with collagen (100 μg/ml) and surface blocked with denatured BSA to form platelet aggregates as previously described [14]. Imaging of aggregate formation was performed using Köhler-illuminated Nomarski DIC optics with a Zeiss 40× 0.75 NE EC Plan Neofluar lens on a Zeiss Axiocam MRm camera and Slidebook 5.0 software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations). Aggregate formation was computed by manually outlining and quantifying platelet aggregates as previously described [14].

Statistical Analysis

For flow chamber and flow cytometry experiments, data were tested for homogeneity of variance using Bartlett’s test and transformed via the natural log if the test returned p < 0.05, then assessed using twoway analysis of variance (ANOVA: treatment and day as factors), followed by post-hoc analysis using Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) test. For aggregation experiments, percent aggregation was assessed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA: treatment and day as factors) with post-hoc analysis via Bonferroni-corrected pairwise t-tests, and lag time data were right-censored at 120 sec and fitted to a Kaplan-Meier survival curve and the log-rank test performed for each comparison. For all analyses, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

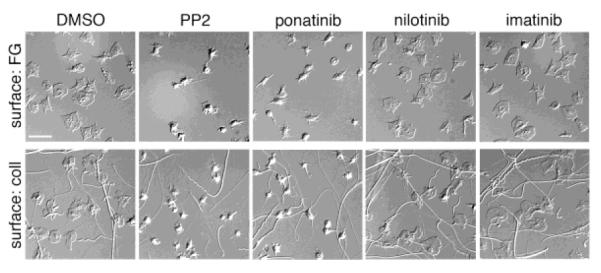

Ponatinib blocks platelet spreading on fibrinogen and collagen surfaces

To determine the effect of BCR-ABL inhibitors on the intracellular signaling pathways that drive platelet activation, we first examined the effects of BCR-ABL inhibitors on the ability of platelets to spread on surfaces of either fibrillar collagen or fibrinogen, which support platelet adhesion and activation downstream of the platelet glycoprotein receptor GPVI / integrin α2β1 and integrin αIIbβ3, respectively [15]. Replicate samples of washed human platelets were treated with BCR-ABL inhibitors in solution prior to spreading on collagen- or fibrinogen-coated coverslips, fixed, and visualized by differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy. As seen in Figure 1, treatment of platelets with ponatinib (1μM), but not nilotinib (1μM) or imatinib (1μM), inhibited platelet spreading and lamellipodia formation on fibrillar collagen and fibrinogen surfaces. Treatment of platelets with the Src family kinase (SFK) inhibitor PP2 served as a control to monitor platelet inhibition [12]. The addition of thrombin in solution reversed the inhibitory effect of ponatinib (data not shown), indicating that the effects of the BCR-ABL inhibitors on platelet spreading can be bypassed through G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR)-mediated signaling.

Figure 1. Ponatinib inhibits platelet surface spreading.

Replicate samples of washed human platelets (2×107 /ml) treated for 10 minutes with vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%), ponatinib (1 μM), nilotinib (1 μM), or imatinib (1 μM) were spread on fibrinogen (FG, 50 μg/ml) or fibrillar collagen (coll, 100 μg/ml) at 37°C. After 45 min, platelets were fixed, mounted onto slides and visualized. Scale bar = 10 μm. Results are representative of three experiments.

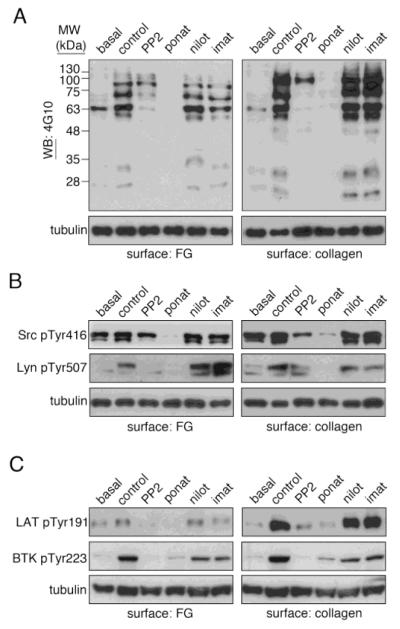

Effect of BCR-ABL inhibitors on tyrosine phosphorylation in platelets

We hypothesized that BCR-ABL inhibitors such as ponatinib interfere with platelet function through an inhibition of tyrosine kinase activation proximal to the engagement of platelet activating receptors, including GPVI and integrin αIIbβ3. Accordingly, we next examined the effects of ponatinib, nilotinib, and imatinib on the intracellular signaling cascades mediating platelet activation following exposure to fibrillar collagen or fibrinogen. As seen in Figure 2A, treatment of platelets with ponatinib markedly inhibited the tyrosine kinase activation profile of platelets on surfaces of fibrinogen or fibrillar collagen as determined by Western blot analysis of platelet lysates with 4G10 antisera; imatinib and nilotinib had only minor effects on the activation of platelet tyrosine kinases. In addition to Abl, ponatinib has been shown to inhibit a number of tyrosine kinases in vitro, including Src family kinases (SFKs) [16]. To specify a role for the inhibition of Src by ponatinib in mediating platelet inhibition, we next examined the phosphorylation state of the Src kinase activation loop (Tyr416) which serves as a marker of Src kinase activation [17]. As seen in Figure 2B, exposure of platelets to surfaces of fibrinogen or fibrillar collagen upregulated Src Tyr416 phosphorylation in platelets. Like PP2, ponatinib inhibited Src Tyr416 phosphorylation in response to fibrinogen or collagen (Figure 2B). In contrast, platelet Src Tyr416 phosphorylation was not effected by nilotinib or imatinib treatments (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Ponatinib inhibits platelet tyrosine kinase activation.

Replicate samples of washed human platelets (5×108 /ml) treated for 10 minutes with vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%), ponatinib (1 μM), nilotinib (1 μM), or imatinib (1 μM) were spread surfaces of fibrinogen (50 μg/ml) or fibrillar collagen (100 μg/ml) at 37°C. After 45 min, non-adherent platelets were removed and adherent platelets were washed three with PBS before lysis into sample buffer, separation by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting (WB) for (A) phosphotyrosine moieties with 4G10 antisera as well as (B) phospho-Src Tyr416, phospho-Lyn Tyr507 and (C) phospho-BTK Tyr223 and phospho-LAT Tyr191. Tubulin serves as a loading control. Western blots are representative of four experiments.

Previous studies have noted that BCR-ABL inhibitors, including ponatinib, inhibit the phosphorylation of the SFK member Lyn and have inhibitory effects on the activation of the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase BTK [16-19]. As both of these kinases have roles in platelet activation [20, 21], we examined the effect of ponatinib, nilotinib, and imatinib on the activation state of Lyn [21] as well as BTK [20] in response to platelet spreading on fibrillar collagen and fibrinogen. Similar to the Src family kinase inhibitor, PP2, treatment of platelets with ponatinib markedly reduced the levels of Lyn Tyr507 phosphorylation in response to spreading on fibrinogen or fibrillar collagen (Figure 2B). Phosphorylation of BTK Tyr223, an autophosphorylation site that serves as a marker of BTK activation [22], was also reduced by ponatinib or PP2 treatment (Figure 2C). Imatinib and nilotinib had only marginal inhibitory effects on Lyn and BTK phosphorylation (Figure 2). Similar to BTK phosphorylation, platelet SFKs also support the phosphorylation of the linker for activation of T cells protein, LAT, which serves roles in platelet PLCγ activation, calcium signaling and the later stages of platelet activation [15, 23]. As shown in Figure 2C, both ponatinib and PP2 inhibited the LAT Tyr191 phosphorylation in platelets bound to surfaces of fibrinogen or fibrillar collagen. LAT phosphorylation was minimally effected by nilotinib or imatinib treatments (Figure 2C). Together, these studies support a role for ponatinib as an inhibitor of platelet Src family tyrosine kinase activation and signaling.

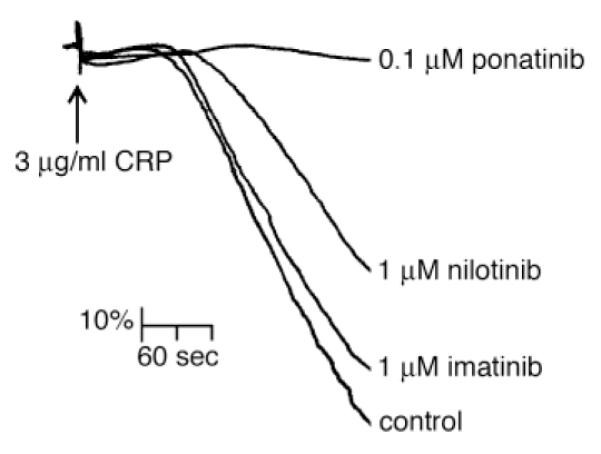

Effect of BCR-ABL inhibitors on platelet aggregation

We next examined the effects of BCR-ABL inhibitors on platelet activation and aggregation in response to the GPVI-agonist collagen-related peptide (CRP), which mediates platelet activation in a receptor tyrosine kinase-dependent manner, and the platelet agonist thrombin, which acts through GPCRs. As shown in Figure 3 and Table 1, platelet aggregation in response to stimulation with CRP (3 μg/ml) was dramatically decreased by ponatinib at concentrations as low as 0.1 μM. Furthermore, treatment with ponatinib significantly increased the lag time for platelet shape change and aggregation in response to CRP stimulation (Table 1). Conversely, treatment with nilotinib (1 μM) and imatinib (1 μM) had little effect on extent of platelet aggregation and lag time in response to addition of CRP (Figure 3 and Table 1). Treatment with ponatinib, nilotinib, or imatinib had no effect on platelet aggregation in response to stimulation with thrombin (0.1 U/ml; Table 1).

Figure 3. Ponatinib blocks platelet aggregation in response to CRP stimulation.

Washed human platelets (2×108 /ml) were treated with ponatinib (0.1 μM), nilotinib (1 μM), and imatinib (1 μM) before stimulation with 3 μg/ml CRP (time of addition signified by arrow) and analysis by Born aggregometry. The change in optical density was recorded as a vertical drop and lag times to quantify the extent of the inhibition of platelet aggregation (Table 1). Results are representative of three experiments.

Table 1.

Effect of BCL-ABL inhibitors on percent aggregation and lag times.

| Inhibitor | Agonist | Percent Aggregation (%) | Lag Time (sec) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO (0.1%) | CRP (3 μg/ml) |

100 | 14.3 ± 3.1 |

| ponatinib (0.1 μM) | 4.3 ± 20.5 * | 42.0 ± 5.1 * | |

| nilotinib (1 μM) | 79.0 ± 15.6 | 11.3 ± 2.2 | |

| imatinib (1 μM) | 96.4 ± 3.2 | 15.0 ± 1.5 | |

| DMSO (0.1%) | Thrombin (0.1 U/ml) |

100 | 3.0 ± 0.0 |

| ponatinib (1 μM) | 80.1 ± 28.9 | 3.0 ± 0.0 | |

| nilotinib (1 μM) | 100 ± 9.2 | 3.0 ± 0.0 | |

| imatinib (1 μM) | 98.4 ± 13.5 | 3.0 ± 0.0 |

signifies p<0.05 with respect to DMSO control; mean ± S.E.M.

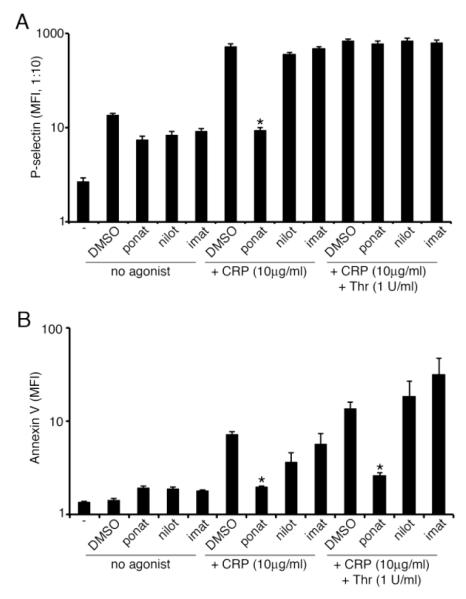

Effect of BCR-ABL inhibitors on platelet P-selectin and phosphatidylserine exposure

In vivo, platelet activation and aggregation is associated with the secretion of P-selectin from platelet alpha granules, which is associated with thrombus stability [24], as well as the externalization of phosphatidylserine (PS), which regulates blood coagulation by providing a platform for the coagulation factor assembly required for thrombin generation [25]. Given the recent reports of thrombotic complications in ponatinib-treated patients [10] and the ability of ponatinib to upregulate PS-exposure on apoptotic cells in culture [26], we next assayed the effect of ponatinib, nilotinib, and imatinib on platelet P-selectin and PS surface levels during platelet activation. Replicate samples of washed human platelets were treated with BCR-ABL inhibitors prior to stimulation with CRP and/or thrombin, staining with anti-P-selectin (CD62P) antibodies or FITC-conjugated Annexin-V prior to flow cytometry analysis. As seen in Figure 4, ponatinib (1 μM) significantly decreased platelet P-selectin exposure in response to CRP. The addition of thrombin reversed the inhibitory effect of ponatinib, indicating that the effects of ponatinib on P-selectin exposure can be bypassed through GPCR-mediated signaling. Ponatinib also significantly decreased PS exposure, as measured by Annexin V binding, in response to CRP alone as well as in response to CRP in combination with thrombin. Treatment of platelets with nilotinib or imatinib (1 μM) did not significantly affect P-selectin or PS exposure in response to CRP or a combination of CRP and thrombin.

Figure 4. Ponatinib blocks P-selectin and phosphatidylserine exposure.

(A) Platelet surface P-selectin levels analyzed by flow cytometry following vehicle (DMSO), ponatinib (1 μM), nilotinib (1 μM), or imatinib (1 μM) treatment and incubation with vehicle, CRP (10 μg/ml), or thrombin (1 U/ml). (B) Phosphatidylserine levels analyzed by flow cytometry following vehicle (DMSO), ponatinib (1 μM), nilotinib (1 μM), or imatinib (1 μM) treatment and incubation with vehicle, CRP (10 μg/mL), or CRP (10 μg/mL) and thrombin (1 U/ml). Results shown as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). * signifies p<0.05 with respect to DMSO control; N=3, error bars represent S.E.M.

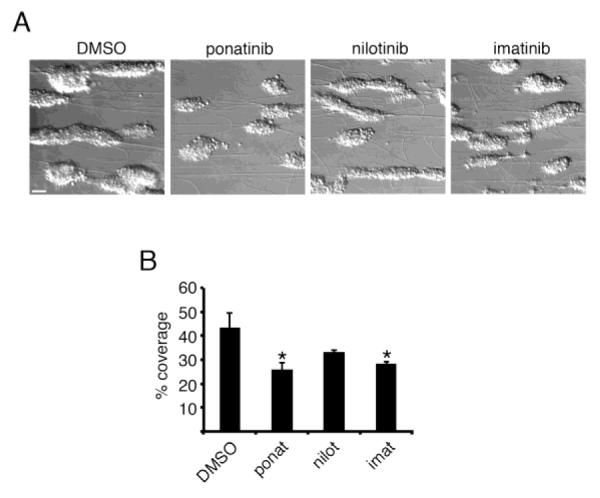

Effect of BCR-ABL inhibitors on aggregate formation under flow

We next looked at the effect of the BCR-ABL inhibitors on aggregate formation in a flow chamber model of platelet aggregate formation. Whole human blood was pretreated BCR-ABL inhibitors prior to flow over a surface of fibrillar collagen at an initial shear rate of 2200 sec−1 for 5 min, fixed, and visualized. As seen in Figure 5, ponatinib reduced aggregate formation under shear, as evidenced by a 52.4 ± 11.2% reduction in platelet aggregate surface area coverage in the presence of ponatinib as compared to vehicle alone (0.1% DMSO). Interestingly, although to a lesser extent than ponatinib, imatinib significantly decreased the platelet aggregate formation on collagen under shear.

Figure 5. Ponatinib inhibits platelet aggregate formation under shear.

(A) Whole blood was treated with vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%), ponatinib (1 μM), nilotinib (1 μM), or imatinib (1 μM) and perfused at 2200 s−1 at 37°C through vitro tubes coated with collagen (100 μg/ml) to form platelet aggregates. (B) The percent surface area covered by aggregates was computed by outlining and quantifying platelet aggregates. * signifies p<0.05 with respect to DMSO control; error bars represent S.E.M. N=3, scale bar = 10 μm.

Discussion

Here we demonstrate that the BCR-ABL inhibitor ponatinib blocks platelet immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) signaling as well as platelet spreading, aggregation, and aggregate formation under shear. While bleeding tendencies that occur in patients undergoing BCR-ABL targeted therapies have been hypothesized to occur as a result of platelet inhibition [7, 8, 27] or a decrease in platelet production by megakaryocytes [28], serious cardiovascular complications have been observed in some patients treated with ponatinib [10, 11]. However, the pathological mechanisms underlying these contradictory clinical observations in patients undergoing BCR-ABL directed therapies have not yet been resolved. Our results show that, in vitro, ponatinib acts as a platelet antagonist at clinically achievable concentrations, inhibiting platelet activation, granule secretion, spreading, and aggregation through ITAM signaling.

Ponatinib was designed as a next-generation therapy for CML patients with specific BCR-ABL kinase domain T315I mutations that promote resistance to imatinib as well as the second generation BCR-ABL inhibitors nilotinib or dasatinib [16]. Ponatinib effectively inhibits tyrosine kinase activity of Abl; however, ponatinib also inhibits other tyrosine kinases with well-defined roles in platelet function, including the Src family kinases (SFKs) Src and Lyn [16, 29]. Indeed, a previous study describing an inhibition of platelet function in patients treated with ponatinib suggested that the loss of platelet function in such patients could be attributed to the inhibition of non-Abl targets in platelets such as SFKs [7]; however, the ability of ponatinib to act as a platelet SFK inhibitor and platelet antagonist remained unexamined. In this study, we find that, in vitro, while treatment of platelets with imatinib or nilotinib had only marginal effects on platelet tyrosine kinase phosphorylation, ponatinib markedly reduced the overall levels of tyrosine phosphorylated proteins and dramatically reduced the levels of activated Src and phosphorylated Lyn in platelets activated on fibrinogen or collagen surfaces. Phosphorylation of the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) and LAT, which occur downstream of Src activation in platelet GPVI signaling [15, 23, 30], was also inhibited by treatment with ponatinib.

At the onset of the GPVI/ITAM platelet signaling processes, an interplay amongst platelet SFKs and other tyrosine kinases and phosphatases positively and negatively orchestrates the temporality of platelet activation [15, 30]. Such signaling events are complex, as SFKs such as Lyn can both inhibit or potentiate aspects of platelet function, including platelet spreading, aggregation and dense granule secretion [21, 31, 32]. Lyn also regulates the aggregation of platelets on collagen surfaces under arterial shear [21]. Congruent with its role as a Lyn inhibitor and platelet antagonist, we found that treatment of whole blood with ponatinib reduced aggregate formation in flow chamber studies. However, the consistent and straightforward role of ponatinib as a platelet antagonist in our studies, inhibiting platelet spreading, aggregation, and secretion in vitro suggests that rather than acting solely as a Lyn-specific inhibitor, ponatinib may also target other SFKs with roles in platelet function. In addition, the dramatic inhibition of Lyn phosphorylation and minor reduction in total phosphotyrosine protein content found in ponatinib-treated platelets relative to platelets treated with the Src kinase inhibitor, PP2, suggests that ponatinib may act as a platelet SFK inhibitor with specificity for SFK family members that differs from that of other SFK inhibitors such as PP2.

The release of P-selectin from platelet alpha granules is a marker of platelet activation and predictor of thrombotic complications in cancer, such as venous thromboembolism [33, 34]. Consistent with its role as a platelet antagonist, we found that ponatinib effectively inhibited platelet P-selectin secretion in response to CRP stimulation as determined by flow cytometry analysis (Figure 4A). In a manner similar to apoptosis, platelets also externalize plasma membrane phosphatidylserine, which plays a role in coagulation through the activation of the tissue factor pathway and clotting cascade. Intriguingly, previous studies have shown that ponatinib upregulates apoptotic pathways in transformed cells, resulting in enhanced PS exposure [26]. Given the prothrombotic effects of ponatinib in some patients, we tested the hypothesis that ponatinib potentiated PS exposure in platelets. However, examination of platelet PS exposure through Annexin V staining and flow cytometry revealed that, like other platelet antagonists, ponatinib inhibits PS exposure in activated platelets. These findings suggest that the mechanism of PS exposure in primary cells such as platelets from healthy donors is different than the mechanism of PS exposure in transformed cell lines.

Nonetheless, cancer cells can promote coagulation in a PS-dependent manner [35], and ponatinib may be acting specifically on BCR-ABL+ cells to promote thrombosis through an upregulation of apoptosis in a manner different from that of BCR-ABL inhibitors that are not associated with thrombotic events. The role of BCR-ABL expression thus represents an intriguing area of future research, particularly given the role of BCR-ABL in cellular transformation and the adverse cardiovascular events associated with ponatinib relative to other Abl inhibitors. As our results show that pobatinib inhibits platelet function, the cardiovascular events observed in patients taking ponatinib may be the result of an effect on other organs or cell types or disease-specific processes, such as BCR-ABL+ cells undergoing apoptosis in response to chemotherapy, or drug-induced adverse effects on the integrity of the vascular endothelium in ponatinib-treated patients.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that ponatinib inhibits the ability of platelets to activate SFK signaling required for spreading and aggregate formation through ITAM and integrin signaling pathways.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

- The BCR-ABL inhibitor ponatinib inhibits platelet ITAM-mediated signaling

- Ponatinib inhibits platelet spreading on collagen and fibrinogen

- Ponatinib inhibits platelet P-selectin and phosphatidylserine exposure downstream of GPVI

- Ponatinib inhibits platelet adhesion and aggregate formation on collagen under shear

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01HL101972 to O.J.T.M.), the American Heart Association (13POST13730003 to J.E.A. and 13EIA12630000 to O.J.T.M.) and the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute (OCTRI; UL1TR000128 to O.J.T.M. and UL1 RR024140 to L.D.H). C.P.L. is a Phi Kappa Phi Marcus L. Urann Fellow and Chi Omega Mary Love Collins Scholar. We thank J. Pang for technical assistance and M. Loriaux for insightful discussions.

Abbreviations

- CML

chronic myelogenous leukemia

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- CRP

collagen-related peptide

- BTK

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase

- PRP

platelet rich plasma

- DIC

differential interference contrast

- GPVI

glycoprotein VI

- SFK

Src family kinase

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- PS

phosphatidylserine

- ITAM

immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Authorship C.P.L. designed this project, performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. J.E.A. assisted in experimental design and in writing the manuscript. R.A.R. carried out aggregation and flow cytometry experiments and analyzed data. M.S.N. carried out flow chamber experiments. L.D.H. helped perform research. A.G., B.J.D., and O.J.T.M. supervised the research and assisted in writing the manuscript.

Disclosures AG and Oregon Health & Science University have a significant financial interest in Aronora Inc., a company that may have a commercial interest in the result of this research. This potential conflict of interest has been reviewed and managed by the Oregon Health & Science University Conflict of Interest in Research Committee. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- [1].Druker BJ. Imatinib as a paradigm of targeted therapies. Adv Cancer Res. 2004;91:1–30. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(04)91001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].O’Hare T, Walters DK, Stoffregen EP, Jia T, Manley PW, Mestan J, et al. In vitro activity of Bcr-Abl inhibitors AMN107 and BMS-354825 against clinically relevant imatinib-resistant Abl kinase domain mutants. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4500–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Weisberg E, Manley PW, Breitenstein W, Bruggen J, Cowan-Jacob SW, Ray A, et al. Characterization of AMN107, a selective inhibitor of native and mutant Bcr-Abl. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:129–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Weisberg E, Manley P, Mestan J, Cowan-Jacob S, Ray A, Griffin JD. AMN107 (nilotinib): a novel and selective inhibitor of BCR-ABL. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1765–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Huang WS, Metcalf CA, Sundaramoorthi R, Wang Y, Zou D, Thomas RM, et al. Discovery of 3-[2-(imidazo[1,2-b]pyridazin-3-yl)ethynyl]-4-methyl-N-{4-[(4-methylpiperazin-1-y l)methyl]-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl}benzamide (AP24534), a potent, orally active pan-inhibitor of breakpoint cluster region-abelson (BCR-ABL) kinase including the T315I gatekeeper mutant. J Med Chem. 2010;53:4701–19. doi: 10.1021/jm100395q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gozgit JM, Wong MJ, Wardwell S, Tyner JW, Loriaux MM, Mohemmad QK, et al. Potent activity of ponatinib (AP24534) in models of FLT3-driven acute myeloid leukemia and other hematologic malignancies. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:1028–35. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Neelakantan P, Marin D, Laffan M, Goldman J, Apperley J, Milojkovic D. Platelet dysfunction associated with ponatinib, a new pan BCR-ABL inhibitor with efficacy for chronic myeloid leukemia resistant to multiple tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. Haematologica. 2012;97:1444. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.064618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Quintas-Cardama A, Han X, Kantarjian H, Cortes J. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor-induced platelet dysfunction in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2009;114:261–3. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-180604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cohen MH, Williams G, Johnson JR, Duan J, Gobburu J, Rahman A, et al. Approval summary for imatinib mesylate capsules in the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:935–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dalzell MD. Ponatinib pulled off market over safety issues. Manag Care. 2013;22:42–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Mathisen MS, Kantarjian HM, Cortes J, Jabbour EJ. Practical issues surrounding the explosion of tyrosine kinase inhibitors for the management of chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood Rev. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Aslan JE, Tormoen GW, Loren CP, Pang J, McCarty OJ. S6K1 and mTOR regulate Rac1-driven platelet activation and aggregation. Blood. 2011;118:3129–36. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-331579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Aslan JE, Itakura A, Gertz JM, McCarty OJ. Platelet shape change and spreading. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;788:91–100. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-307-3_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Aslan JE, Itakura A, Haley KM, Tormoen GW, Loren CP, Baker SM, et al. p21 activated kinase signaling coordinates glycoprotein receptor VI-mediated platelet aggregation, lamellipodia formation, and aggregate stability under shear. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:1544–51. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.301165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Watson SP, Auger JM, McCarty OJ, Pearce AC. GPVI and integrin alphaIIb beta3 signaling in platelets. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:1752–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].O’Hare T, Shakespeare WC, Zhu X, Eide CA, Rivera VM, Wang F, et al. AP24534, a pan-BCR-ABL inhibitor for chronic myeloid leukemia, potently inhibits the T315I mutant and overcomes mutation-based resistance. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:401–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Xu W, Doshi A, Lei M, Eck MJ, Harrison SC. Crystal structures of c-Src reveal features of its autoinhibitory mechanism. Mol Cell. 1999;3:629–38. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gleixner KV, Peter B, Blatt K, Suppan V, Reiter A, Radia D, et al. Synergistic growth-inhibitory effects of ponatinib and midostaurin (PKC412) on neoplastic mast cells carrying KIT D816V. Haematologica. 2013;98:1450–7. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.079202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hantschel O, Grebien F, Superti-Furga G. The growing arsenal of ATP-competitive and allosteric inhibitors of BCR-ABL. Cancer Res. 2012;72:4890–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Quek LS, Bolen J, Watson SP. A role for Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (Btk) in platelet activation by collagen. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1137–40. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70471-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Severin S, Nash CA, Mori J, Zhao Y, Abram C, Lowell CA, et al. Distinct and overlapping functional roles of Src family kinases in mouse platelets. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:1631–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04814.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Park H, Wahl MI, Afar DE, Turck CW, Rawlings DJ, Tam C, et al. Regulation of Btk function by a major autophosphorylation site within the SH3 domain. Immunity. 1996;4:515–25. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80417-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Pasquet JM, Gross B, Quek L, Asazuma N, Zhang W, Sommers CL, et al. LAT is required for tyrosine phosphorylation of phospholipase cgamma2 and platelet activation by the collagen receptor GPVI. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:8326–34. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Merten M, Thiagarajan P. P-selectin expression on platelets determines size and stability of platelet aggregates. Circulation. 2000;102:1931–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.16.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lentz BR. Exposure of platelet membrane phosphatidylserine regulates blood coagulation. Prog Lipid Res. 2003;42:423–38. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(03)00025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Sadovnik I, Lierman E, Peter B, Herrmann H, Suppan V, Stefanzl G, et al. Identification of Ponatinib as a potent inhibitor of growth, migration, and activation of neoplastic eosinophils carrying FIP1L1-PDGFRA. Exp Hematol. 2014;42:282–93. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Gratacap MP, Martin V, Valera MC, Allart S, Garcia C, Sie P, et al. The new tyrosine-kinase inhibitor and anticancer drug dasatinib reversibly affects platelet activation in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2009;114:1884–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-205328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mazharian A, Ghevaert C, Zhang L, Massberg S, Watson SP. Dasatinib enhances megakaryocyte differentiation but inhibits platelet formation. Blood. 2011;117:5198–206. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-326850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Okabe S, Tauchi T, Tanaka Y, Ohyashiki K. Efficacy of ponatinib against ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor-resistant leukemia cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;435:506–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tourdot BE, Brenner MK, Keough KC, Holyst T, Newman PJ, Newman DK. Immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM)-mediated inhibitory signaling is regulated by sequential phosphorylation mediated by distinct nonreceptor tyrosine kinases: a case study involving PECAM-1. Biochemistry. 2013;52:2597–608. doi: 10.1021/bi301461t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Chari R, Kim S, Murugappan S, Sanjay A, Daniel JL, Kunapuli SP. Lyn, PKC-delta, SHIP-1 interactions regulate GPVI-mediated platelet-dense granule secretion. Blood. 2009;114:3056–63. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-188516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ming Z, Hu Y, Xiang J, Polewski P, Newman PJ, Newman DK. Lyn and PECAM-1 function as interdependent inhibitors of platelet aggregation. Blood. 2011;117:3903–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-304816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Pabinger I, Thaler J, Ay C. Biomarkers for prediction of venous thromboembolism in cancer. Blood. 2013;122:2011–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-460147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hanna DL, White RH, Wun T. Biomolecular markers of cancer-associated thromboembolism. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;88:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Berny-Lang MA, Aslan JE, Tormoen GW, Patel IA, Bock PE, Gruber A, et al. Promotion of experimental thrombus formation by the procoagulant activity of breast cancer cells. Phys Biol. 2011;8:015014. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/8/1/015014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.