Abstract

High-throughput sequencing allows detailed study of the B cell receptor (BCR) repertoire post-immunization but it remains unclear to what extent the de novo identification of antigen-specific sequences from the total BCR repertoire is possible. A Hib-MenC-TT conjugate vaccine containing H. influenzae type b (Hib) and group C meningococcal (MenC) polysaccharides as well as tetanus toxoid (TT) was used to investigate the BCR repertoire of adult humans following immunization and test the hypothesis that public or convergent repertoire analysis could identify antigen specific sequences. A number of antigen-specific BCR sequences have previously been reported for Hib and TT which made a vaccine containing these 2 antigens an ideal immunological stimulus. Analysis of identical complementarity determining region (CDR)3 amino acid (AA) sequences that were shared by individuals in the post-vaccine repertoire identified a number of known Hib-specific sequences but only one previously described TT sequence. The extension of this analysis to non-identical but highly similar CDR3 AA sequences revealed a number of other TT-related sequences. The anti-Hib avidity index post-vaccination was strongly correlated with the relative frequency of Hib-specific sequences, indicating that the post-vaccination public BCR repertoire may be related to more conventional measures of immunogenicity correlating with disease protection. Analysis of public BCR repertoire provided evidence of convergent BCR evolution in individuals exposed to the same antigens. If this finding is confirmed, the public repertoire could be used for rapid and direct identification of protective antigen-specific BCR sequences from peripheral blood.

Introduction

The human humoral response is anticipatory, with diverse antibody specificities present even prior to antigen stimulation, to account for the extensive range of potential antigens likely to be encountered. The basis for this diverse repertoire is the multiple variable (V), diversity (D; heavy chain only) and junctional (J) B cell gene segments encoding the variable region of the antibody heavy and light chain proteins (1). Further variation is created by combinatorial association, junctional diversity, and somatic hypermutation, leading to the creation of up to 1011 unique antibody molecules (2). Within the variable domains of each heavy and light chain are the 3 complementarity determining regions (CDR), which encode the amino acid loops of the antigen binding site, and are particularly susceptible to somatic hypermutation (3). Of these, the variable heavy (VH) CDR3 plays a dominant role in antigen binding and specificity (4, 5).

‘Next-generation’ sequencing (NGS) technologies perform large-scale DNA sequencing (6), allowing in-depth analysis of the B cell receptor (BCR) repertoire of the circulating B cell pool (7, 8). The Roche 454 platform generates reads of sufficient length to interrogate the entire recombined heavy chain VDJ region. 454 sequencing of antibody variable regions has been used to obtain estimates of BCR repertoire diversity (2, 9), to detect and track clonal expansions in lymphoid malignancy (10) and to investigate the characteristics of different B cell lineages (11-13). However, understanding the diversity of the BCR repertoire in relation to antigen specificity remains challenging. This is an important area to advance understanding in autoimmunity, immunity against infectious diseases and immunization. Studies of the BCR repertoire generated in response to specific antigens such as bacterial polysaccharides (14-16), viral glycoproteins (17-19) and autoimmune antigens (20) have used small numbers of immortalized B cell lines and suggested that genetically diverse individuals utilized similar combinations of heavy chain VDJ segments in response to a given antigen. However there is some evidence that VDJ gene segment usage may be relatively independent of antigen specificity supported by the fact that BCR sequences that differ markedly in the CDR3 sequence can have the same V(D)J usage (J. Trück, unpublished observations). NGS approaches have the potential to advance understanding of this area through access to vastly increased numbers of BCR sequences across a larger number of individuals. Whilst isolation of antigen-specific B cells is possible, this requires the development of antigen-specific staining and sorting protocols to detect low frequency B cell populations. Several studies have utilized the relative enrichment for antigen-specific B cells that occurs at day 7 following immunization. Whilst these have demonstrated changes in the large-scale structural features of the repertoire they have not investigated which features of BCR sequences indicate antigen-specificity. Two recent studies found that conserved CDR3 sequences were produced in patients recovering from acute dengue infection (21) and during the immune response following pandemic influenza H1N1 vaccination (22). The characteristic that similar CDR3 sequences dominate the immune response in different individuals following antigen stimulation is often referred to as the presence of a convergent or public repertoire. We utilized a model antigen in the form of a vaccine in which Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) and serogroup C meningococcal (MenC) polysaccharides are conjugated to tetanus toxoid (TT) to stimulate human B cell responses. A significant amount of BCR sequence data are already available for the Hib polysaccharide showing that clonotypes are similar between individuals and revealing usage of a single VH (V3-23) and only two JH gene segments combined with two variable and joining light chain gene segments (23-26). The canonical Hib-specific antibody has a conserved CDR3 amino acid motif of Gly–Tyr–Gly–Phe/Met–Asp (GYGMD or GYGFD) (27). Previous investigations used low-resolution methods and were therefore only able describe a small number of Hib-specific sequences whereas information about the relative abundance of different sequences between time points and individuals, their mutational rate, and the isotype subclasses is lacking. For TT the limited data indicate that there is a much more diverse repertoire with very few sequences that are shared (28, 29). The use of antigens with CDR3 sequences known to specifically bind antigen together with deep sequencing of B cell heavy chain variable domains following antigen stimulation provides an opportunity to investigate several aspects of the repertoire. The main objective of the present study was to identify antigen-specific BCR sequences following vaccination by searching for sequences shared between participants and by comparing sequences to previously described antigen-specific sequences. Sequence analysis focused on CDR3 amino acid (AA) sequences although other V gene regions such as CDR1 and CDR2 may also be important for antigen binding (3). Antigen-specific repertoires were then used to characterize CDR3 length, V(D)J usage, mutational rate and isotype (subclasses). Finally, the Hib-specific repertoires were compared to anti-Hib antibody concentration and avidity index in order to investigate the use of repertoire sequencing as an alternative measure of immunogenicity.

Material and Methods

Participants and vaccine

Antibody responses specific for Hib were studied as part of a single center, open-label clinical study in healthy adults aged 18-65 years, undertaken to generate a Hib reference serum for the UK’s National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (NIBSC). Written informed consent was obtained from the participants before enrollment. Ethical approval was obtained from the Oxfordshire Research Ethics Committee (OXREC Reference: 08/H0605/74). Volunteers received a Hib-MenC polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccine (Menitorix®, GlaxoSmithKline), containing Hib polyribosyl ribitol phosphate (PRP, 5 μg) polysaccharide and meningococcal serogroup C polysaccharide (5 μg) individually conjugated to tetanus toxoid carrier protein (total 17.5 μg). Blood was taken from participants immediately prior to vaccination, and at 7 and 28 days after vaccination.

Anti-PRP antibody and avidity index 1 month post-vaccination

Serum anti-PRP immunoglobulin G (IgG) concentrations were measured by ELISA. Antibody avidity can be used as a surrogate measure for antibody quality and tends to be increased in memory responses (30). Antibody avidity was determined by elution using a 0.15M solution of the chaotrope sodium thiocyanate as a separate step after the initial binding of the serially diluted sera. Avidity index was expressed as the percent reduction in IgG concentration compared to the concentration in the absence of the chaotrope (31).

B cell isolation and cell sorting

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained by density gradient centrifugation over Lymphoprep (Axis-Shield). CD19+ cells were separated at baseline from all participant samples and at day 7, either plasma or CD19+ cells were obtained. Enrichment of cell populations was performed by magnetic cell separation using CD19 MicroBeads or Plasma cell isolation Kit II and the AutoMacs (Miltenyi Biotec). The purity of sorted populations was checked using flow cytometry and was 95-99% for plasma cells and 82-97% for the CD19+ B cells.

cDNA synthesis and PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized using random hexamers and Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) with reverse transcription at 42°C (60 min) and inactivation at 95°C (10 min). Antibody heavy chain sequences were amplified using previously published VH family consensus forward primers, and reverse primers enabling identification of IgM, IgA and IgG (11). Two rounds of PCR amplification were performed using Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen) with initial denaturation at 94°C (3 min); followed by 30 (first round) or 15 (second round) cycles of denaturation at 94°C (30s), annealing at 58°C (30s), extension at 72°C (1 min); and final extension at 72°C (10 min).

Library preparation and 454 sequencing

The PCR amplicons were prepared for sequencing and blunt-end ligated to multiplex identifier (MID) tags using the Roche GS FLX Titanium Rapid Library Preparation Protocol. Emulsion PCR and pyrosequencing were performed on each library using the GS FLX Titanium XL+ sequencing platform.

Sequence analysis

Output files were converted into fasta files and sequences were assigned a sample and isotype based on the MID sequence. For two individuals at both time points, isotype-specific amplicons were sequenced without separate MID tags and sequences were therefore assigned an isotype by constant region sequence motifs; sequences that could not be matched for isotype were discarded. Remaining sequences were analyzed using IMGT/HighV-Quest allowing for insertions and deletions (32) and only productive sequences were further considered. Analysis was performed using Rstudio (version 0.98.490) and R (33) and graphically displayed using ggplot2 (34). Sequence clonality was calculated by dividing the total number of sequences for each sample by the number of unique VDJ combinations. Of note, an increase in clonality at the sequence level could reflect either an increase in overall clonality of the B-cell population or a change in immunoglobulin mRNA expression levels in a subset of B-cells within a population of fixed clonality.

Sequences with identical CDR3 AA sequences, which were shared between at least 2 individuals were used to define the public repertoire. Hib-specific sequences were identified as those which (a) contained either the AA string ‘GYGMD’ or ‘GYGFD’ (27) and (b) were exactly 10 AA long. For each of these sequences VJ usage and the relative abundances were calculated by dividing the number of Hib-specific sequences by the total number of sequences for each sample. Further, for each of the Hib-specific CDR3 AA sequences, the number of study participants using identical VJ combinations to create the same Hib-specific CDR3 AA sequence was calculated.

CDR3 AA sequences were also compared to previously described sequences specific for Hib (24, 25, 27, 35), TT (36-39), H1N1 influenza (40, 41), and MenC (42, 43) by searching for identical and closely related sequences in the dataset. Approximate matches to known CDR3 AA string patterns were searched within the data by the ‘agrep’ function in R (33) using the default parameters but excluding insertions and deletions (maximum Levenshtein edit distance between pattern substring and search strings equals to 10% of the pattern substring length, e.g. for a 10 AA string the maximal number of substitutions allowed to call it ‘related’ would be 1 AA).

Proportions of Hib-specific sequences per total number of sequences were calculated for each sample and their log-transformed values correlated with the log-transformed antibody concentrations and avidity indices. The same analysis was performed to calculate the correlation between the frequencies of unique Hib-specific CDR3 AA sequences and antibody.

Isotype subclass information for IgA and IgG was determined by mapping constant region nucleotide sequences to all possible isotype (subclasses) using Stampy (44) and VEGA constant region sequences as reference (45). The number of V gene mutations were taken from IMGT output files and compared between sequences of different antigen specificities and isotype subclasses.

Results

General overview

At baseline, CD19 B cells were isolated from all 5 participants. Seven days following vaccination, CD19 B cells were isolated from 2 individuals and plasma cells from 3 individuals. From each sample IgG, IgA and IgM BCR libraries were prepared with one library preparation failing (IgG from plasma cells). In total, 460,077 sequences were obtained (average 15,860 per sample), of which 184,844 (average 6,374 per sample) were considered as productive by IMGT (Table I). Around 12% of constant region sequences from IgA sequence libraries [7,094/61,023 sequences] were too short for confirmation of an IgA subclass and the isotype of 110 sequences (0.2%) differed from the original PCR primer isotype. For IgG sequence libraries, 2,781/25,280 (11%) sequences were too short for identification and the isotype of 19 sequences (0.08%) differed from the original PCR primer isotype. Before vaccination, IgA sequences were dominated by IgA1, and IgG1 was most common amongst the IgG sequences. After vaccination, there was a relative increase in IgA1 from 65% to 70% and IgG2 from 33% to 48% of assigned sequences (Fig. S1A).

Table I. Characteristics of sequence data.

| Participant | Day post-vaccination | Isotype B-cell subset | Total no. of sequences | No. of productive sequences | No. of Hib CDR3 AA sequencesa | No. of unique Hib CDR3 AA sequencesb | Anti-PRP Ab / avidity index | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | IgA | CD19+ | 3,313 | 2,527 | 0 | 0 | |

| IgG | 2,277 | 1,689 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| IgM | 7,843 | 5,998 | 0 | 0 | 49.0 μg/ml | |||

| 7 | IgA | PC | 3,750 | 3,026 | 277 | 4 | 59.83 | |

| IgG | 2,165 | 1,710 | 78 | 3 | ||||

| IgM | 8,694 | 6,932 | 601 | 6 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| 2 | 0 | IgA | CD19+ | 5,071 | 3,997 | 0 | 0 | |

| IgM | 12,802 | 10,256 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 7 | IgA | PC | 3,899 | 3,289 | 620 | 6 | 45.89 μg/ml | |

| IgG | 1,612 | 1,342 | 446 | 10 | 343.29 | |||

| IgM | 7,131 | 5,819 | 1,221 | 13 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| 3 | 0 | IgA | CD19+ | 23,857 | 9,522 | 1 | 1 | |

| IgG | 19,412 | 3,763 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| IgM | 20,773 | 10,879 | 1 | 1 | 7.3 μg/ml | |||

| 7 | IgA | PC | 24,768 | 12,073 | 143 | 4 | 30.15 | |

| IgG | 15,334 | 5,350 | 97 | 8 | ||||

| IgM | 27,272 | 10,156 | 71 | 5 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| 4 | 0 | IgA | CD19+ | 21,952 | 7,858 | 1 | 1 | |

| IgG | 32,545 | 2,391 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| IgM | 24,633 | 11,237 | 0 | 0 | 29.1 μg/ml | |||

| 7 | IgA | CD19+ | 22,630 | 9,080 | 624 | 10 | 66.51 | |

| IgG | 20,871 | 3,723 | 614 | 10 | ||||

| IgM | 23,315 | 9,279 | 399 | 8 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| 5 | 0 | IgA | CD19+ | 26,016 | 9,051 | 0 | 0 | |

| IgG | 18,655 | 3,227 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| IgM | 23,552 | 11,774 | 0 | 0 | 123.7 μg/ml | |||

| 7 | IgA | CD19+ | 19,134 | 7,804 | 50 | 3 | 3.52 | |

| IgG | 16,379 | 4,885 | 5 | 2 | ||||

| IgM | 20,422 | 6,207 | 1 | 1 | ||||

Sequence clonality and CDR3 length distributions

At baseline, clonality was similar for each of the isotypes. The day 7 plasma cell samples were significantly more oligoclonal than their paired baseline CD19+ B cell samples whereas for paired pre- and post-vaccination CD19+ B cell samples an increase in clonality was seen for IgG but not IgA or IgM sequences (Fig. S1B). Graphical representation of the VDJ repertoire also showed increased clonality after vaccination (Fig. S2). CDR3 length distributions of all isotypes were similar between isotypes and before and after vaccination (Fig. S1C).

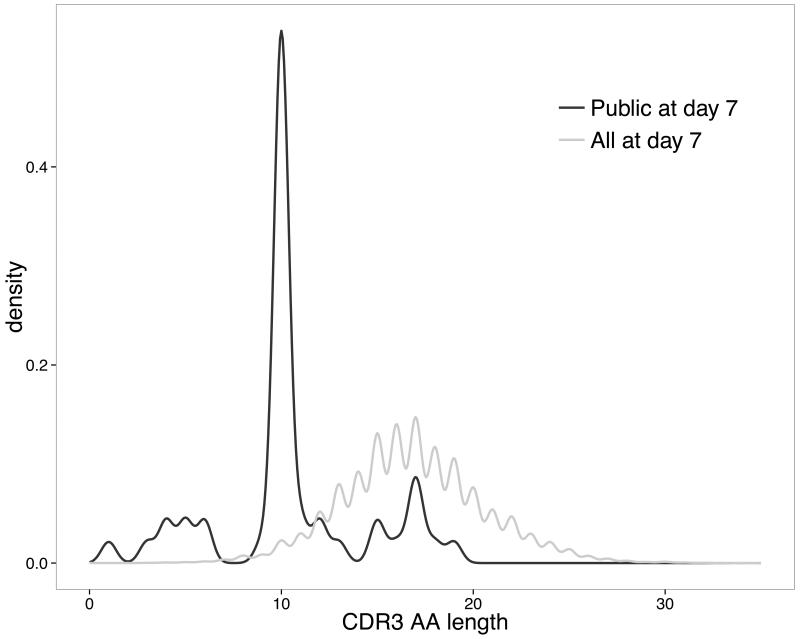

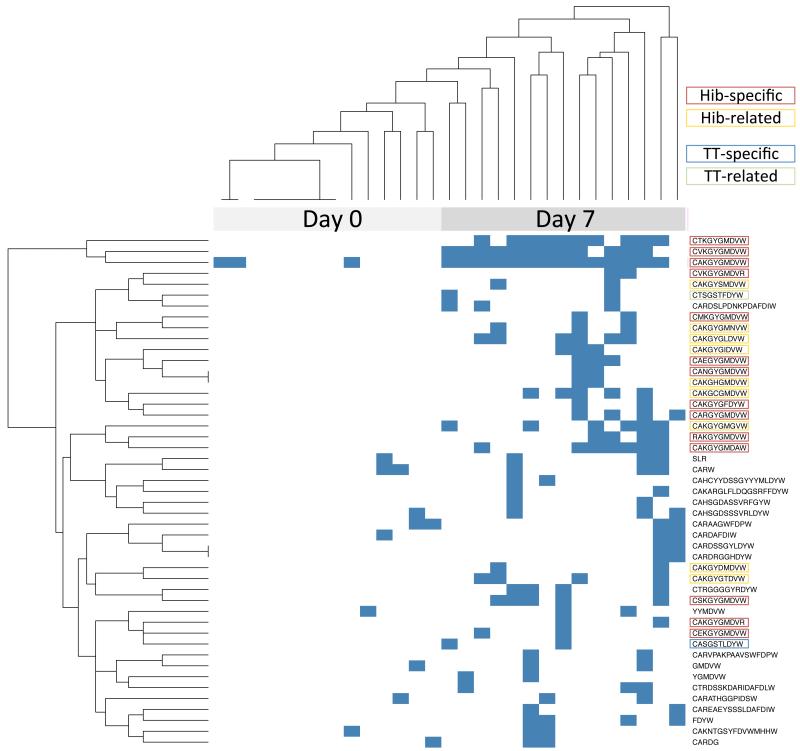

The post-vaccination public repertoire is dominated by Hib-specific sequences

The post-vaccination public repertoire was defined as the collection of CDR3 AA sequences that were shared by at least two out of the 5 individuals. A total of 47 unique such CDR3 AA sequences were found. More than 50% of these CDR3 AA sequences were exactly 10 AA long, which was considerably shorter than the average CDR3 AA sequence lengths from all sequence data at day 7 (Fig. 1). We further assessed for presence of these 47 shared CDR3 AA sequences in all samples and the result is represented as an unsupervised heatmap with dendrograms in Fig. 2. Thirty percent of the day 7 public CDR3 AA sequences (14/47) showed distinctive characteristics of previously identified Hib-specific motifs (27). The frequency of sequences determined as Hib-specific was significantly enriched post-vaccination in all of the isotypes tested, although the frequency of those sequences differed considerably between individuals (Table I). The 3 most abundant CDR3 AA sequences, which were shared by all 5 individuals and present in 10-14 out of the 15 post-vaccination samples, contained Hib-specific motifs (Fig. 2). Another 9 of the public CDR3 AA sequences post-vaccination were also 10 AA long but differed by only 1 AA from previously described Hib-specific CDR3 AA motifs (Fig. S3A). Hence, almost half (23/47) of the CDR3 AA sequences in the post-vaccination public repertoire showed characteristics similar or identical to those previously described as binding the Hib polysaccharide antigen.

Fig. 1. CDR3 AA length distributions of unique sequences 7 days post-vaccination shared by at least 2 study participants (“public repertoire”) compared with all sequences at day 7 (“total repertoire”).

The proportion of sequences of a particular length (x-axis) without counting duplicate sequences in each group is shown on the y-axis as a density plot.

Fig. 2. Heatmap and unsupervised hierarchical clustering of shared CDR3 AA sequences.

Individual samples (columns) were assessed for the presence of shared CDR3 AA sequences (rows). A blue square indicates that the CDR3 AA sequence of at least 1 sequence matched exactly the query string.

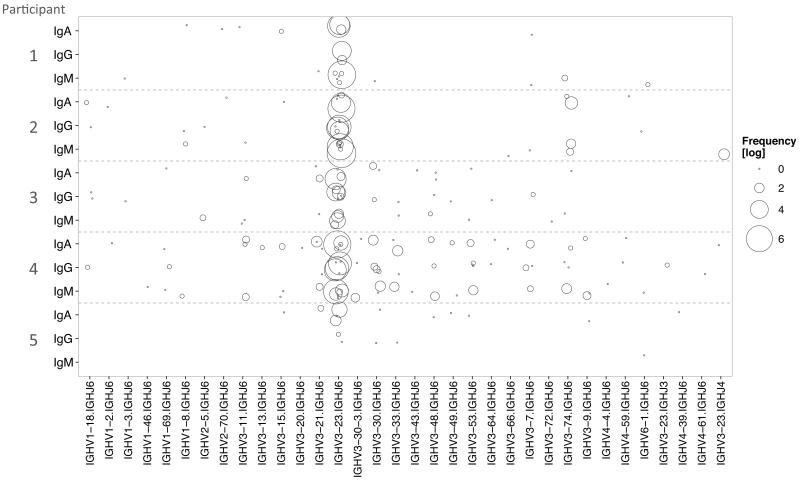

VJ usage of Hib-specific sequences

Sequences containing known Hib-specific CDR3 AA motifs were further analyzed. These sequences were dominated by gene rearrangements consisting of the gene segments V3-23 and J6 in all isotypes. The Hib-specific CDR3 AA sequences shared by all participants (which were also the most abundant sequences) showed the broadest range of VJ usage (Fig. S3B). In general less diversity of VJ usage was observed in the IgG than in IgM or IgA repertoires (Fig. S3B). While there were variations in the breadth of VJ usage between individuals, within a given participant a similar usage of VJ segments was seen across the different isotypes (Fig. 3). We also assessed how many participants used the same VJ combination to create similar Hib-specific CDR3 AA sequences and found that VJ usage of some of the Hib-specific CDR3 AA sequences is very diverse whereas for other CDR3 AA sequences only a single VJ rearrangement is found (Fig. S4A).

Fig. 3. VJ gene usage of known Hib-specific sequences by individual participants according to isotype at day 7 post-vaccination.

For each participant, the VJ usage of Hib-specific sequences is shown by isotype with the size of the circle representing the number of sequences of a particular VJ combination on the log scale. Participants showed similar VJ usage of Hib-specific CDR3 AA sequences across isotypes.

Tetanus toxoid-specific BCR repertoire

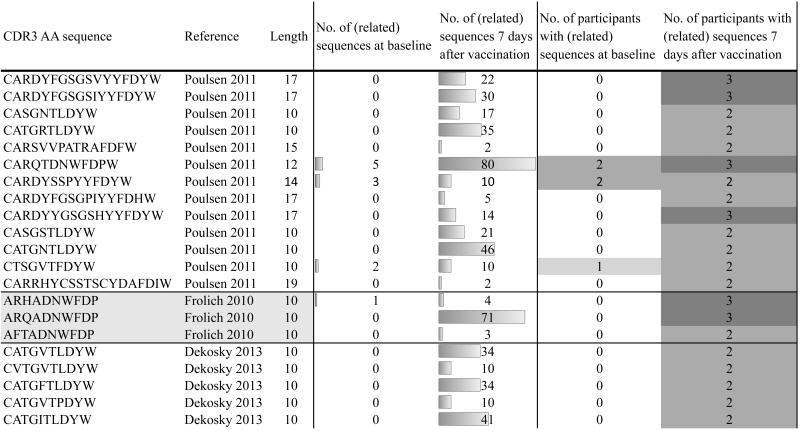

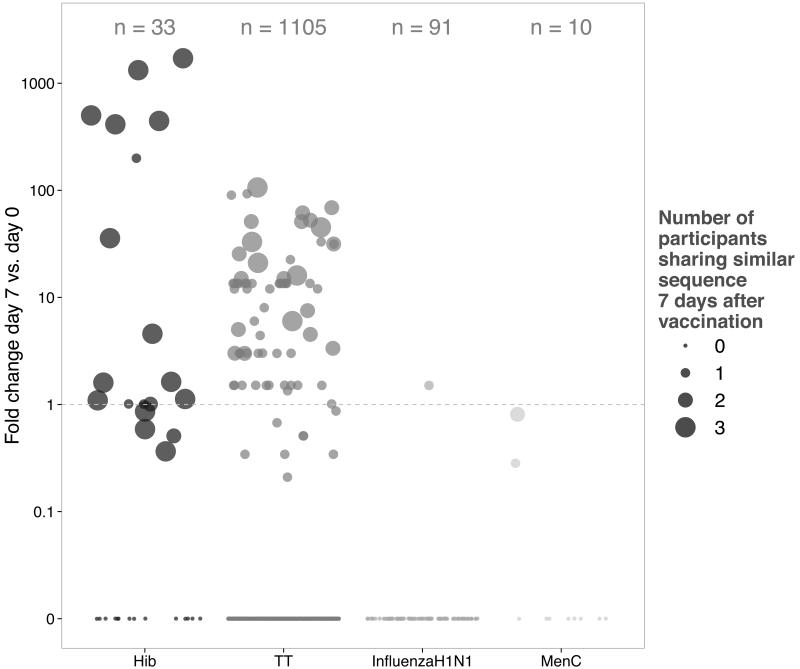

In addition to the Hib-specific sequences which dominated the shared repertoire at day 7 post-vaccination, one shared CDR3 AA sequence we identified was previously described as TT-specific (“CASGSTLDYW”) (36), with another sequence of similar length closely resembling this sequence (“CTSGSTFDYW”) (Fig. 2). By allowing some mismatch between the CDR3 AA sequences in the dataset and previously described sequences specific for TT, we identified several other sequences related to known TT-specific sequences. The majority of CDR3 AA sequences identified in this manner had the same length and was highly similar (Levenshtein edit distance between pattern substring and search strings at most 2) to previously described sequences (not shown). These TT-related sequences found in the dataset were enriched and shared between individuals 7 days post-vaccination (Fig. 4). In a similar manner the dataset was investigated for sequences previously described as specific for H1N1 influenza and MenC. Sequences related to these antigens were not enriched post-vaccination (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4. Known TT-specific CDR3 AA sequences that are found with minor changes in the dataset and are shared by at least 2 study participants.

Shown are sequences in the dataset that are related to previously identified TT-specific sequences along with information about CDR3 AA length, pre- and post-vaccine frequency, and the number of participants sharing related sequences at baseline and at day 7 following vaccination.

Fig. 5. Fold change in frequencies at day 7 compared to baseline for sequences that were closely related to previously described to be specific for Hib, TT, H1N1 influenza and MenC and number of participants sharing these sequences.

Enrichment of these sequences was calculated as fold changes between post- and pre-vaccination frequencies; for sequences not present at baseline, fold change was calculated as 1.5 times frequency post-vaccination.

The Hib- and TT-repertoires consist of limited isotype subclasses and show increased mutation post-vaccination

Post-vaccination Hib-specific sequences were dominated by the subclasses IgA2 and IgG2 (Fig. S4B). For sequences related to known TT-sequences a relative increase for subclasses IgA1 and IgG1 was seen (Fig. S4C).

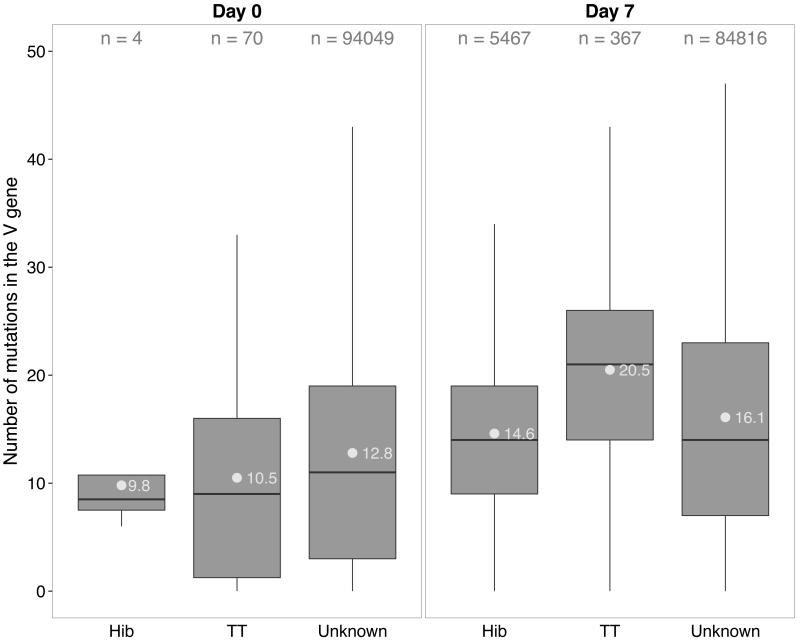

Frequencies of nucleotide (nt) mutations in V genes (VMUT) differed between isotypes, with IgM sequences having fewer mutations both before and after vaccination than other isotypes. VMUT increased significantly for IgM and IgG but not for IgA sequences after vaccination (not shown). At baseline, sequences identified as Hib or TT-specific had similar VMUT compared with sequences of unknown specificity, although numbers of antigen-specific sequences were low. Seven days post-vaccination, VMUT differed significantly between sequences of Hib, TT and unknown specificity (TT >> unknown >> Hib, p<10−16 for all comparisons (t-test); Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Number of V gene mutations by antigen specificity.

Shown are boxplots of numbers of V gene mutations in sequences identified as Hib- or TT-specific compared with sequences of unknown specificity at baseline (left) and 7 days post-vaccination (right). N indicates the number of sequences per group of sequences. Grey dots with numbers represent average mutations within each group of sequences.

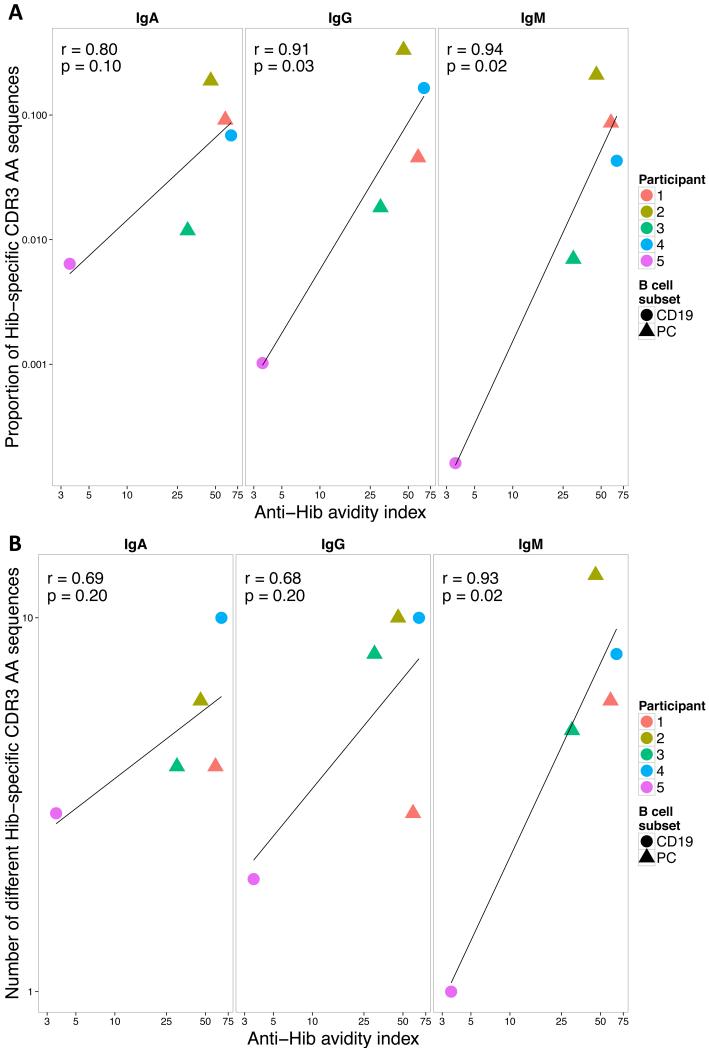

Hib-specific CDR3 AA frequency and diversity are correlated with functional anti-Hib antibody

The proportion of Hib-specific CDR3 AA sequences per sample by isotype at day 7 correlated strongly with anti-Hib avidity indices 1 month following vaccination (Fig. 7A, Pearson’s r=0.8-0.94, significant for IgG and IgM) but not with anti-PRP antibody concentrations measured at 1 month (Fig. S4D). Similarly, the number of non-identical Hib-specific CDR3 AA sequences per sample correlated with avidity indices (Fig. 7B, r=0.68-0.93, significant for IgM) but not with antibody concentrations (Fig. S4E).

Fig. 7. Correlation between anti-Hib avidity indices and (A) frequency of Hib-specific sequences or (B) number of different Hib-specific CDR3 AA sequences 7 days after vaccination.

Filled circles and triangles represent results of day 7 plasma cell (PC) and total B cell (CD19) samples. Pearson’s correlation coefficient and the corresponding p-value of each calculation are shown in the left hand corner of each graph and the line through the data points represents the regression line.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that high-throughput sequencing of B cell receptor heavy chain transcripts before and after vaccination can be used to identify antigen-specific sequences, by studying response to a vaccine containing capsular polysaccharides from Hib and MenC, individually conjugated to TT carrier protein. Known and presumptive novel antigen-specific sequences were found by searching for heavy chain CDR3 AA sequences that were shared between participants and by comparing sequences to previously described as antigen-specific sequences within the pool of post-vaccination sequences. Post-vaccination sequences shared between study participants were rare as a proportion of total sequence diversity (47/32,186 (0.15%) unique CDR3 AA sequences) but constituted a much greater proportion of total (8,099/90,675 (8.9%) CDR3 AA sequences). Whilst sequences (especially short sequences) may be shared by chance, the approach used in the study identified sequences that were highly enriched only in post-vaccine samples. These sequences also showed isotype subclass distribution similar to previous studies using serum, and were similar to those with previously described antigen specificity. The data from IgG sequences suggest that it may be possible to identify public repertoire sequences, following vaccination, from total CD19+ B cells without the need for isolation of plasma cells. Public repertoire sequences had an unusual CDR3 AA length distribution and were dominated by CDR3 sequences with a length of 10 AA (Fig. 1). This feature of shorter post-vaccination CDR3 sizes has previously been shown using spectratype analysis following combined influenza and 23-valent pneumococcal vaccination (46). It is unknown whether this is a property of newly generated antigen-specific CDR3 AA sequences (versus resting memory or naïve B cells) or if this is characteristic of sequences stimulated by polysaccharide-containing Hib and pneumococcal vaccines. A large proportion of shared (unique) CDR3 motifs (14/47, corresponding to 5,206/8,099 (64%) sequences) showed an AA motif previously characterized as specific for the capsular polysaccharide of Hib (27). Almost all of the sequences that were 10 AA long and contained previously identified Hib-motifs (5,206/5,248 (99.2%) sequences) were shared between participants. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of samples containing day 7 shared CDR3 AA sequences distinguished baseline and day 7 samples further indicating that these CDR3 AA sequences were produced in response to vaccination (Fig. 2). We identified another 9/47 (14%) CDR3 AA motifs within the post-vaccination public repertoire closely resembling known Hib motifs and which were also enriched in post-vaccination samples (Fig. 2 and S3A). Although it is possible that these ‘novel’ Hib-specific sequences are the result of PCR or 454 sequencing errors it seems unlikely that similar errors would have occurred in separate samples from 2 different participants. Sequences containing those additional motifs were rare in the present study (72/8,099 shared sequences) and it is therefore likely that previous attempts using low-resolution techniques may have missed these sequences. Such previous methods have been used to describe a limited number of monoclonal antibodies directed against a variety of vaccine antigens and in response to natural infection (21, 24, 36-38, 41, 47-54). NGS allows capture of the whole breadth of the BCR repertoire by comparing sequences between time points and across individuals.

In the current study, although dominated by previously described sequences using V3-23 and J6 gene segments, Hib-specific sequences were also found to be encoded by a variety of different V segments (Fig. S3B). Furthermore similar CDR3 AA sequences were encoded by similar V and J genes between several individuals (Fig. S4A) suggesting that the Hib-specific antibody response is broader than previously acknowledged both within and between individuals therefore making it unlikely that germline allelic polymorphisms have a great impact on the overall quantity and quality of anti-Hib antibodies (55). These results also suggest that anti-Hib antibodies can harbor a range of different CDR1 and CDR2 sequences as previously demonstrated in the immune response to a variety of antigens in mice (5).

We further expanded the sequence analysis aiming to identify and characterize sequences targeting the tetanus toxoid protein contained in the vaccine given to study participants. Only 1 of 47 shared CDR3 AA sequences was identical to previously described TT-specific sequences. The lack of TT-specific sequences in the public repertoire may be the result of TT antigen complexity and the targeting of many more epitopes of this protein (compared to a polysaccharide antigen with repeating units) by B cells. However, by comparing the dataset to 3 different published sources (36-38) and allowing for minimal mismatches between the CDR3 AA sequences, many more sequences closely resembling TT-specific sequences were identified (Fig. 4). Around 55% of the sequences related to previously known CDR3 AA sequences were shared between participants post-vaccination, highlighting the convergence of the antigen-specific BCR repertoire. On the other hand, almost none of the sequences resembled any of the 91 previously described H1N1 influenza-specific sequences (40, 41), both before and after vaccination (Fig. 5). Few MenC-specific sequences have previously been identified, largely in mice, which may be why only 3 MenC-related sequences were found in the dataset (Fig. 5), all of which were shared between study participants but their frequencies were lower at day 7 than at baseline. It is quite possible that some of the day 7 shared sequences of unknown specificity are targeting the MenC polysaccharide, which we were unable to confirm because of lack of pre-existing MenC data. Using a single component vaccine may help to identify MenC-specific sequences.

Mutational analysis of Hib- and TT-specific sequences within the dataset revealed that in general TT sequences are more mutated than Hib sequences. V gene mutations increased significantly for all specificities between baseline and post-vaccination samples further indicating that these sequences are generated by vaccine-containing antigens. The differences in mutation between Hib and TT might be due to the nature of the antigen, protein vs. polysaccharide. However, it is noteworthy the volunteers in this study may have received as many as 5 doses of tetanus vaccine through the UK immunization program, but most of the participants are unlikely to have received any Hib vaccine, since they were born before this immunization program commenced. Hib is a frequent colonizing organism in healthy children (56) but the nature of B cell priming following Hib carriage is unclear. Post-vaccination plasma cell samples were more oligoclonal than baseline CD19 samples for all isotypes (Fig. S1B), consistent with the plasma cell population being enriched for antigen-specific cells. In contrast to previous work (11, 12), we were unable to detect a difference between the clonality of IgA, IgG and IgM sequences when adjusted for the total number of sequences per sample (Fig. S1C). Briney et al. calculated the contribution of the 50 most common VDJ combinations for the overall repertoire in 3 different B cell subsets, which had been isolated by flow cytometry (12) but did not adjust for total number of sequences observed in each sample, which may have biased this result. Wu et al (11) similarly reported on clone size distributions of different B cell subsets and found that switched memory B cells in particular showed larger clone expansions than naïve B cells. Relatively few sequences per sample were considered in the latter study and this may have been due to prior sorting of B cell subsets by flow cytometry. We performed cDNA synthesis and PCR amplification directly on bulk cell populations (CD19+ B cells or plasma cells) which required less in vitro manipulation. In the present study sequences were compared before and after receipt of a highly immunogenic protein-polysaccharide vaccine. IgA and IgM repertoires obtained from CD19+ B cells were similar before and after vaccination whereas the clonality of plasma cell samples was increased compared with CD19+ B cell baseline samples for IgA and IgM sequences. Interestingly, this difference in clonality between plasma and CD19+ B cell samples at day 7 was not found in IgG sequences indicating that the IgG sequence pool of CD19+ B cells is dominated by newly generated (oligoclonal) antigen-experienced sequences. In addition, plasma cells are actively secreting cells containing vast amounts of BCR mRNA, resulting in over-representation of these sequences in the repertoire data, which may be more pronounced in the pool of IgG sequences.

For many vaccines, alternative methods to measure immunogenicity are desirable, either because current laboratory tests are too variable, difficult or time-consuming to perform on a large scale or are not available. High-throughput B cell receptor sequencing data was compared to Hib immunogenicity data. The proportion of Hib-specific sequences in each sample correlated with anti-Hib avidity indices but not with total anti-PRP antibody concentration (Fig. 4 and S4D). The antibody data seem to suggest opposite relationships between the frequencies of Hib sequences and anti-PRP antibody concentration for total B cell and plasma cell populations (Fig S4D) but numbers for each B cell population are small and more data are needed to resolve this question. Not only the relative number of Hib-specific sequences but also the number of different Hib-specific CDR3 AA sequences correlated well with the anti-Hib avidity index post-vaccination. Thus, the expansion of closely related sequences sharing a similar length (in this case 10 AA) seems to be a feature of a more pronounced immune response and may therefore serve in the future as a further characteristic to identify ‘good responders’. Antibody avidity represents a measure of the amount of functional antibody as generated by the vaccine. Hib-specific sequences included mainly IgA2 and IgG2 sequences (Fig. S4B), which is consistent with previous work demonstrating that IgG2 anti-Hib antibodies are the predominant IgG subclass in adult sera (57). Sequences that were identified as TT-specific (i.e. identical to or related to previously known TT sequences) were enriched for IgA1 and IgG1 sequences post-vaccination (Fig. S4C), which is in line with published data (58-60) further confirming the validity of this approach.

In conclusion, using high-throughput sequencing of the heavy chain B cell repertoire in the peripheral blood of participants following immunization with a Hib-MenC-TT glycoconjugate vaccine, we were able to confirm that the analysis of the public BCR repertoire post-immunization identifies BCRs enriched for vaccine specific sequences. The identification of previously described Hib- and TT-specific sequences (and sequences related to them) through analysis of the public repertoire demonstrates convergence of CDR3 AA sequences in response to antigen stimulation. We linked Hib-specific CDR3 AA frequencies to functional anti-Hib antibody data suggesting that the Hib-specific repertoire is a specific marker of the immune response to the Hib polysaccharide. This study provides the first confirmation that the convergent BCR repertoire post-immunization can be used as a way of rapidly identifying antigen-specific sequences without sorting antigen-specific B-cells. High-throughput methods to detect paired heavy and light chains have been described and when combined with such analyses will allow the production of functional antibodies from such data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

A.J.P is a Jenner Institute Investigator and James Martin Senior Fellow. J.T. is a James Martin Fellow.

Funding J.T. was supported by an ESPID fellowship award. D.F.K receives salary support from the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre. Oxford University Medical Research Fund (Medical Sciences Division) provided funding for this study. G.L. was funded by Wellcome Trust grant 090532/Z/09/Z.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Tonegawa S. Somatic generation of antibody diversity. Nature. 1983;302:575–581. doi: 10.1038/302575a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glanville J, Zhai W, Berka J, Telman D, Huerta G, Mehta GR, Ni I, Mei L, Sundar PD, Day GM, Cox D, Rajpal A, Pons J. Precise determination of the diversity of a combinatorial antibody library gives insight into the human immunoglobulin repertoire. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20216–20221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909775106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohno S, Mori N, Matsunaga T. Antigen-binding specificities of antibodies are primarily determined by seven residues of VH. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:2945–2949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.9.2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noel D, Bernardi T, Navarro-Teulon I, Marin M, Martinetto JP, Ducancel F, Mani JC, Pau B, Piechaczyk M, Biard-Piechaczyk M. Analysis of the individual contributions of immunoglobulin heavy and light chains to the binding of antigen using cell transfection and plasmon resonance analysis. J Immunol Methods. 1996;193:177–187. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(96)00043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu JL, Davis MM. Diversity in the CDR3 region of V(H) is sufficient for most antibody specificities. Immunity. 2000;13:37–45. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Margulies M, Egholm M, Altman WE, Attiya S, Bader JS, Bemben LA, Berka J, Braverman MS, Chen YJ, Chen Z, Dewell SB, Du L, Fierro JM, Gomes XV, Godwin BC, He W, Helgesen S, Ho CH, Ho CH, Irzyk GP, Jando SC, Alenquer ML, Jarvie TP, Jirage KB, Kim JB, Knight JR, Lanza JR, Leamon JH, Lefkowitz SM, Lei M, Li J, Lohman KL, Lu H, Makhijani VB, McDade KE, McKenna MP, Myers EW, Nickerson E, Nobile JR, Plant R, Puc BP, Ronan MT, Roth GT, Sarkis GJ, Simons JF, Simpson JW, Srinivasan M, Tartaro KR, Tomasz A, Vogt KA, Volkmer GA, Wang SH, Wang Y, Weiner MP, Yu P, Begley RF, Rothberg JM. Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature. 2005;437:376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature03959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Georgiou G, Ippolito GC, Beausang J, Busse CE, Wardemann H, Quake SR. The promise and challenge of high-throughput sequencing of the antibody repertoire. Nat Biotechnol. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nbt.2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galson JD, Pollard AJ, Trück J, Kelly DF. Studying the Antibody Repertoire after Vaccination: Practical Applications. Trends Immunol. 2014;35:319–331. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyd SD, Gaëta BA, Jackson KJ, Fire AZ, Marshall EL, Merker JD, Maniar JM, Zhang LN, Sahaf B, Jones CD, Simen BB, Hanczaruk B, Nguyen KD, Nadeau KC, Egholm M, Miklos DB, Zehnder JL, Collins AM. Individual variation in the germline Ig gene repertoire inferred from variable region gene rearrangements. J Immunol. 2010;184:6986–6992. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyd SD, Marshall EL, Merker JD, Maniar JM, Zhang LN, Sahaf B, Jones CD, Simen BB, Hanczaruk B, Nguyen KD, Nadeau KC, Egholm M, Miklos DB, Zehnder JL, Fire AZ. Measurement and clinical monitoring of human lymphocyte clonality by massively parallel VDJ pyrosequencing. Sci Transl Med. 2009;1:12ra23. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu YC, Kipling D, Leong HS, Martin V, Ademokun AA, Dunn-Walters DK. High-throughput immunoglobulin repertoire analysis distinguishes between human IgM memory and switched memory B-cell populations. Blood. 2010;116:1070–1078. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-275859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Briney BS, Willis JR, McKinney BA, Crowe JE. High-throughput antibody sequencing reveals genetic evidence of global regulation of the naïve and memory repertoires that extends across individuals. Genes Immun. 2012;13:469–473. doi: 10.1038/gene.2012.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prabakaran P, Zhu Z, Chen W, Gong R, Feng Y, Streaker E, Dimitrov DS. Origin, diversity, and maturation of human antiviral antibodies analyzed by high-throughput sequencing. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:277. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernández-Sánchez A, García-Ocaña M, de los Toyos JR. Mouse monoclonal antibodies to pneumococcal C-polysaccharide backbone show restricted usage of VH-DH-JH gene segments and share the same kappa chain. Immunol Lett. 2009;123:125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolibab K, Smithson SL, Shriner AK, Khuder S, Romero-Steiner S, Carlone GM, Westerink MA. Immune response to pneumococcal polysaccharides 4 and 14 in elderly and young adults. I. Antibody concentrations, avidity and functional activity. Immun Ageing. 2005;2:10. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou J, Lottenbach KR, Barenkamp SJ, Lucas AH, Reason DC. Recurrent variable region gene usage and somatic mutation in the human antibody response to the capsular polysaccharide of Streptococcus pneumoniae type 23F. Infect Immun. 2002;70:4083–4091. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4083-4091.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wisnewski A, Cavacini L, Posner M. Human antibody variable region gene usage in HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1996;11:31–38. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199601010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Binley JM, Lybarger EA, Crooks ET, Seaman MS, Gray E, Davis KL, Decker JM, Wycuff D, Harris L, Hawkins N, Wood B, Nathe C, Richman D, Tomaras GD, Bibollet-Ruche F, Robinson JE, Morris L, Shaw GM, Montefiori DC, Mascola JR. Profiling the specificity of neutralizing antibodies in a large panel of plasmas from patients chronically infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtypes B and C. J Virol. 2008;82:11651–11668. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01762-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tian C, Luskin GK, Dischert KM, Higginbotham JN, Shepherd BE, Crowe JEJ. Immunodominance of the VH1-46 antibody gene segment in the primary repertoire of human rotavirus-specific B cells is reduced in the memory compartment through somatic mutation of nondominant clones. J Immunol. 2008;180:3279–3288. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chardès T, Chapal N, Bresson D, Bès C, Giudicelli V, Lefranc MP, Péraldi-Roux S. The human anti-thyroid peroxidase autoantibody repertoire in Graves’ and Hashimoto’s autoimmune thyroid diseases. Immunogenetics. 2002;54:141–157. doi: 10.1007/s00251-002-0453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parameswaran P, Liu Y, Roskin KM, Jackson KK, Dixit VP, Lee JY, Artiles KL, Zompi S, Vargas MJ, Simen BB, Hanczaruk B, McGowan KR, Tariq MA, Pourmand N, Koller D, Balmaseda A, Boyd SD, Harris E, Fire AZ. Convergent antibody signatures in human dengue. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:691–700. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson KJ, Liu Y, Roskin KM, Glanville J, Hoh RA, Seo K, Marshall EL, Gurley TC, Moody MA, Haynes BF, Walter EB, Liao HX, Albrecht RA, García-Sastre A, Chaparro-Riggers J, Rajpal A, Pons J, Simen BB, Hanczaruk B, Dekker CL, Laserson J, Koller D, Davis MM, Fire AZ, Boyd SD. Human Responses to Influenza Vaccination Show Seroconversion Signatures and Convergent Antibody Rearrangements. Cell Host Microbe. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Insel RA, Kittelberger A, Anderson P. Isoelectric focusing of human antibody to the Haemophilus influenzae b capsular polysaccharide: restricted and identical spectrotypes in adults. J Immunol. 1985;135:2810–2816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adderson EE, Shackelford PG, Quinn A, Wilson PM, Cunningham MW, Insel RA, Carroll WL. Restricted immunoglobulin VH usage and VDJ combinations in the human response to Haemophilus influenzae type b capsular polysaccharide. Nucleotide sequences of monospecific anti-Haemophilus antibodies and polyspecific antibodies cross-reacting with self antigens. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:2734–2743. doi: 10.1172/JCI116514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silverman GJ, Lucas AH. Variable region diversity in human circulating antibodies specific for the capsular polysaccharide of Haemophilus influenzae type b. Preferential usage of two types of VH3 heavy chains. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:911–920. doi: 10.1172/JCI115394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lucas AH, McLean GR, Reason DC, O’Connor AP, Felton MC, Moulton KD. Molecular ontogeny of the human antibody repertoire to the Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide: expression of canonical variable regions and their variants in vaccinated infants. Clinical Immunology. 2003;108:119–127. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6616(03)00094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lucas AH, Reason DC. Polysaccharide vaccines as probes of antibody repertoires in man. Immunol Rev. 1999;171:89–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poulsen TR, Meijer PJ, Jensen A, Nielsen LS, Andersen PS. Kinetic, affinity, and diversity limits of human polyclonal antibody responses against tetanus toxoid. J Immunol. 2007;179:3841–3850. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lavinder JJ, Wine Y, Giesecke C, Ippolito GC, Horton AP, Lungu OI, Hoi KH, Dekosky BJ, Murrin EM, Wirth MM, Ellington AD, Dörner T, Marcotte EM, Boutz DR, Georgiou G. Identification and characterization of the constituent human serum antibodies elicited by vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:2259–2264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317793111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldblatt D, Vaz AR, Miller E. Antibody avidity as a surrogate marker of successful priming by Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccines following infant immunization. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1112–1115. doi: 10.1086/517407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romero-Steiner S, Holder PF, Gomez de Leon P, Spear W, Hennessy TW, Carlone GM. Avidity determinations for Haemophilus influenzae Type b anti-polyribosylribitol phosphate antibodies. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12:1029–1035. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.9.1029-1035.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brochet X, Lefranc MP, Giudicelli V. IMGT/V-QUEST: the highly customized and integrated system for IG and TR standardized V-J and V-D-J sequence analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W503–W508. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.R Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wickham HW. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adderson EE, Shackelford PG, Quinn A, Carroll WL. Restricted Ig H chain V gene usage in the human antibody response to Haemophilus influenzae type b capsular polysaccharide. J Immunol. 1991;147:1667–1674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poulsen TR, Jensen A, Haurum JS, Andersen PS. Limits for antibody affinity maturation and repertoire diversification in hypervaccinated humans. J Immunol. 2011;187:4229–4235. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frölich D, Giesecke C, Mei HE, Reiter K, Daridon C, Lipsky PE, Dörner T. Secondary immunization generates clonally related antigen-specific plasma cells and memory B cells. J Immunol. 2010;185:3103–3110. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DeKosky BJ, Ippolito GC, Deschner RP, Lavinder JJ, Wine Y, Rawlings BM, Varadarajan N, Giesecke C, Dörner T, Andrews SF, Wilson PC, Hunicke-Smith SP, Willson CG, Ellington AD, Georgiou G. High-throughput sequencing of the paired human immunoglobulin heavy and light chain repertoire. Nature Biotechnology. 2013;31:166–169. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Faber C, Shan L, Fan Z-C, Guddat LW, Furebring C, Ohlin M, Borrebaeck CA, Edmundson AB. Three-dimensional structure of a human Fab with high affinity for tetanus toxoid. Immunotechnology. 1998;3:253–270. doi: 10.1016/s1380-2933(97)10003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li GM, Chiu C, Wrammert J, McCausland M, Andrews SF, Zheng NY, Lee JH, Huang M, Qu X, Edupuganti S, Mulligan M, Das SR, Yewdell JW, Mehta AK, Wilson PC, Ahmed R. Pandemic H1N1 influenza vaccine induces a recall response in humans that favors broadly cross-reactive memory B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:9047–9052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118979109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krause JC, Tsibane T, Tumpey TM, Huffman CJ, Briney BS, Smith SA, Basler CF, Crowe JE. Epitope-specific human influenza antibody repertoires diversify by B cell intraclonal sequence divergence and interclonal convergence. J Immunol. 2011;187:3704–3711. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hutchins WA, Adkins AR, Kieber-Emmons T, Westerink MAJ. Molecular characterization of a monoclonal antibody produced in response to a group C meningococcal polysaccharide peptide mimic. Molecular Immunology. 1996;33:503–510. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(96)00012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smithson SL, Srivastava N, Hutchins WA, Westerink MA. Molecular analysis of the heavy chain of antibodies that recognize the capsular polysaccharide of Neisseria meningitidis in hu-PBMC reconstituted SCID mice and in the immunized human donor. Mol Immunol. 1999;36:113–124. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(99)00024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lunter G, Goodson M. Stampy: a statistical algorithm for sensitive and fast mapping of Illumina sequence reads. Genome Res. 2011;21:936–939. doi: 10.1101/gr.111120.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilming LG, Gilbert JG, Howe K, Trevanion S, Hubbard T, Harrow JL. The vertebrate genome annotation (Vega) database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D753–D760. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ademokun A, Wu YC, Martin V, Mitra R, Sack U, Baxendale H, Kipling D, Dunn-Walters DK. Vaccination-induced changes in human B-cell repertoire and pneumococcal IgM and IgA antibody at different ages. Aging Cell. 2011;10:922–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jiang N, He J, Weinstein JA, Penland L, Sasaki S, He XS, Dekker CL, Zheng NY, Huang M, Sullivan M, Wilson PC, Greenberg HB, Davis MM, Fisher DS, Quake SR. Lineage structure of the human antibody repertoire in response to influenza vaccination. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:171ra19. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu J, O’Dell S, Ofek G, Pancera M, Wu X, Zhang B, Zhang Z, Mullikin JC, Simek M, Burton DR, Koff WC, Shapiro L, Mascola JR, Kwong PD. Somatic Populations of PGT135-137 HIV-1-Neutralizing Antibodies Identified by 454 Pyrosequencing and Bioinformatics. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:315. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu X, Zhou T, Zhu J, Zhang B, Georgiev I, Wang C, Chen X, Longo NS, Louder M, McKee K, O’Dell S, Perfetto S, Schmidt SD, Shi W, Wu L, Yang Y, Yang Z-Y, Yang Z, Zhang Z, Bonsignori M, Crump JA, Kapiga SH, Sam NE, Haynes BF, Simek M, Burton DR, Koff WC, Doria-Rose NA, Connors M, Mullikin JC, Nabel GJ, Roederer M, Shapiro L, Kwong PD, Mascola JR. Focused Evolution of HIV-1 Neutralizing Antibodies Revealed by Structures and Deep Sequencing. Science. 2011;333:1593–1602. doi: 10.1126/science.1207532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weitkamp JH, Kallewaard N, Kusuhara K, Bures E, Williams JV, LaFleur B, Greenberg HB, Crowe JE. Infant and adult human B cell responses to rotavirus share common immunodominant variable gene repertoires. J Immunol. 2003;171:4680–4688. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.9.4680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rohatgi S, Dutta D, Tahir S, Sehgal D. Molecular Dissection of Antibody Responses against Pneumococcal Surface Protein A: Evidence for Diverse DH-Less Heavy Chain Gene Usage and Avidity Maturation. The Journal of Immunology. 2009;182:5570–5585. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wrammert J, Smith K, Miller J, Langley WA, Kokko K, Larsen C, Zheng NY, Mays I, Garman L, Helms C, James J, Air GM, Capra JD, Ahmed R, Wilson PC. Rapid cloning of high-affinity human monoclonal antibodies against influenza virus. Nature. 2008;453:667–671. doi: 10.1038/nature06890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu YC, Kipling D, Dunn-Walters DK. Age-Related Changes in Human Peripheral Blood IGH Repertoire Following Vaccination. Front Immunol. 2012;3:193. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vollmers C, Sit RV, Weinstein JA, Dekker CL, Quake SR. Genetic measurement of memory B-cell recall using antibody repertoire sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312146110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu L, Lucas AH. IGH V3-23*01 and its allele V3-23*03 differ in their capacity to form the canonical human antibody combining site specific for the capsular polysaccharide of Haemophilus influenzae type b. Immunogenetics. 2003;55:336–338. doi: 10.1007/s00251-003-0583-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oh SY, Griffiths D, John T, Lee YC, Yu LM, McCarthy N, Heath PT, Crook D, Ramsay M, Moxon ER, Pollard AJ. School-aged children: a reservoir for continued circulation of Haemophilus influenzae type b in the United Kingdom. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:1275–1281. doi: 10.1086/586716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Herrmann DJ, Hamilton RG, Barington T, Frasch CE, Arakere G, Mäkelä O, Mitchell LA, Nagel J, Rijkers GT, Zegers B. Quantitation of human IgG subclass antibodies to Haemophilus influenzae type b capsular polysaccharide. Results of an international collaborative study using enzyme immunoassay methodology. J Immunol Methods. 1992;148:101–114. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(92)90163-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Engström PE, Nava S, Mochizuki S, Norhagen G. Quantitative analysis of IgA-subclass antibodies against tetanus toxoid. J Immunoassay. 1995;16:231–245. doi: 10.1080/15321819508013560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Riet E, Retra K, Adegnika AA, Jol-van der Zijde CM, Uh HW, Lell B, Issifou S, Kremsner PG, Yazdanbakhsh M, van Tol MJ, Hartgers FC. Cellular and humoral responses to tetanus vaccination in Gabonese children. Vaccine. 2008;26:3690–3695. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.04.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kroon FP, van Tol MJ, Jol-van der Zijde CM, van Furth R, van Dissel JT. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) subclass distribution and IgG1 avidity of antibodies in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals after revaccination with tetanus toxoid. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:352–355. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.3.352-355.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.