Abstract

Antibody-based therapeutics exhibit great promise in the treatment of central nervous system (CNS) disorders given their unique customizable properties. Although several clinical trials have evaluated therapeutic antibodies for treatment of CNS disorders, success to date has likely been limited in part due to complex issues associated with antibody delivery to the brain and antibody distribution within the CNS compartment. Major obstacles to effective CNS delivery of full length immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies include transport across the blood-brain and blood-cerebrospinal fluid barriers. IgG diffusion within brain extracellular space (ECS) may also play a role in limiting central antibody distribution; however, IgG transport in brain ECS has not yet been explored using established in vivo methods. Here, we used real-time integrative optical imaging to measure the diffusion properties of fluorescently labeled, non-targeted IgG after pressure injection in both free solution and in adult rat neocortex in vivo, revealing IgG diffusion in free medium is ~10-fold greater than in brain ECS. The pronounced hindered diffusion of IgG in brain ECS is likely due to a number of general factors associated with the brain microenvironment (e.g. ECS volume fraction and geometry/width) but also molecule-specific factors such as IgG size, shape, charge and specific binding interactions with ECS components. Co-injection of labeled IgG with an excess of unlabeled Fc fragment yielded a small yet significant increase in the IgG effective diffusion coefficient in brain, suggesting that binding between the IgG Fc domain and endogenous Fc-specific receptors may contribute to the hindered mobility of IgG in brain ECS. Importantly, local IgG diffusion coefficients from integrative optical imaging were similar to those obtained from ex vivo fluorescence imaging of transport gradients across the pial brain surface following controlled intracisternal infusions in anesthetized animals. Taken together, our results confirm the importance of diffusive transport in the generation of whole brain distribution profiles after infusion into the cerebrospinal fluid, although convective transport in the perivascular spaces of cerebral blood vessels was also evident. Our quantitative in vivo diffusion measurements may allow for more accurate prediction of IgG brain distribution after intrathecal or intracerebroventricular infusion into the cerebrospinal fluid across different species, facilitating the evaluation of both new and existing strategies for CNS immunotherapy.

Keywords: antibody, drug delivery, diffusion, distribution, extracellular space, intracisternal, intraparenchymal

1. Introduction

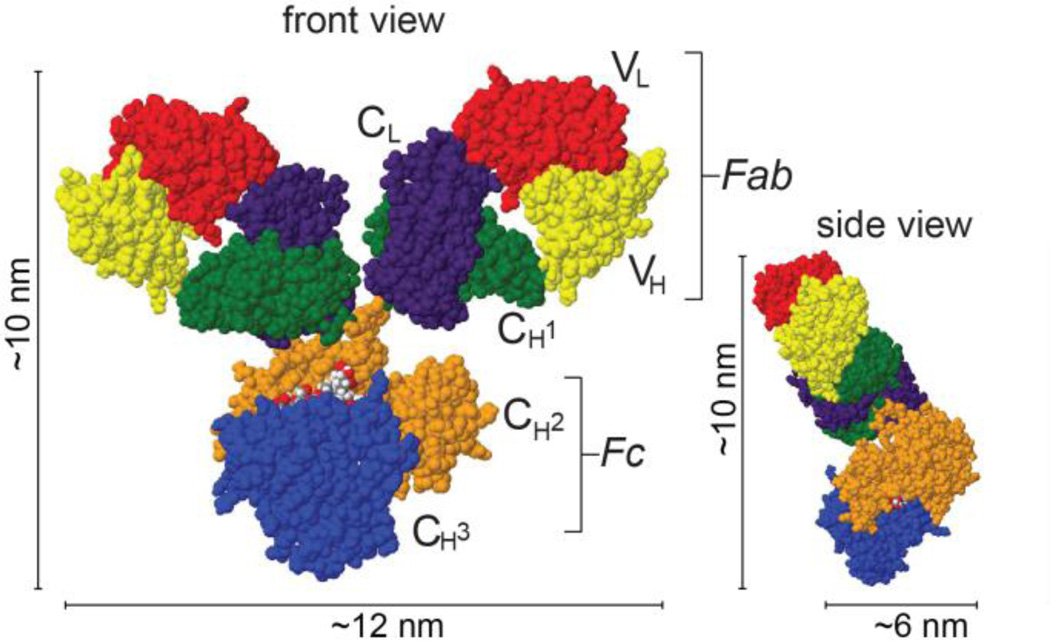

Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies are large proteins (~150 kDa) normally involved in the body’s adaptive immune response. IgG antibodies account for ~80% of all immunoglobulins in human serum, where they exist at levels (~70 µM) second only to albumin (500–800 µM)[1, 2]. IgG antibodies are also abundant in the CNS, where they account for ~7–8% of total protein in normal adult human cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), albeit at lower levels (~0.1–0.2 µM) than in the plasma[3]. IgG antibodies possess two antigen-binding domains (Fab) for binding unique epitopes and a single fragment crystallizable domain (Fc) for the binding of cell surface receptors and the recruitment of effector functions (Figure 1). Although mammalian IgGs can be described as Y-shaped or T-shaped structures comprised of two ellipsoidal Fab subunits connected to a heart-shaped Fc stem, many IgG isoforms show considerable flexibility in solution[4]. Known Fc receptors include the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn or Brambell receptor) and Fc receptors specific to Ig isoforms (e.g. FcγR for IgG)[1, 5]. While FcRn is thought to act as a protection or salvage receptor in vascular endothelia, protecting antibodies from intracellular catabolism and prolonging their serum half-life, FcRn only binds IgG with high affinity in the acidic environment of early endosomes (~pH 6) after cellular internalization[1, 5]. Conversely, FcγRs normally bind IgG with high affinity as they distribute within extracellular fluid (~pH 7.4). Importantly, FcγRs are located on most cell types of the brain[6], where they play roles in normal brain function (e.g. facilitating IgG uptake and IgG-dependent neurotransmitter release[7]) and in CNS disorders (e.g. initiating inflammatory responses in microglia following stroke[8]).

Figure 1.

Antibody structure. Space-filled rendering of murine IgG in Jmol (PDB ID: 1IGY [24]) with the Fab and Fc domains outlined. Mammalian IgG has two long axes (with typical lengths of approximately 10–15 nm[24, 25]) and one short axis with a unique Y- or T-shaped geometry.

The use of IgG antibodies as neurotherapeutics is an attractive strategy because these biologics may in theory be used to treat a great range of diseases due to their high specificity, potency, and customizability as drug candidates[9]. Antibody engineering has enabled the targeting of IgG to specific antigens or receptors that may potentially be of benefit in neurological disorders varying from cancer[10, 11] to Alzheimer’s disease[12, 13]. Several IgGs have already been in clinical trials for Alzheimer's disease, but a number of these have failed to meet their primary endpoints despite promising pre-clinical results; the precise reasons for these failures remain unclear (e.g. they may include inadequate selection of potentially responsive patient populations[14]), but a major factor is likely associated with the challenge of achieving adequate delivery to sites of action within the brain[15]. Strategies to address this delivery challenge include systemic approaches that utilize endogenous receptor-mediated transcytosis systems at the blood-brain barrier[16] or central approaches such as administering antibodies intraventricularly or intrathecally so they may travel along with the CSF circulation[13]. Regardless of the strategy used to achieve brain delivery, antibodies will need to distribute within brain tissue to reach all potential target sites. It is therefore important to develop a quantitative understanding of the factors affecting this distribution.

Nearly all CNS drugs must navigate the brain extracellular space (ECS) to exert their effects. Diffusion governs distribution within the ECS and is influenced by properties of the brain microenvironment as well as the specific characteristics of the diffusing molecule. Established techniques to measure extracellular diffusion in vivo include real-time iontophoresis, ventriculocisternal perfusion of radiotracers, and integrative optical imaging (IOI) of fluorescent probes[17]; these methods have been used to show that the normal, adult brain ECS accounts for ~20% of total tissue volume in most areas[18] and that the neocortical ECS is about 40–60 nm in width[19]. Importantly, diffusion measurements have also shown that all molecules experience hindrance as they travel through the brain ECS and encounter cellular obstructions. This hindrance is characterized by a dimensionless parameter termed the tortuosity (λ = (D/D*)1/2, where D is the free diffusion coefficient and D* is the effective diffusion coefficient in brain)[17, 18]. The potential sources of diffusional hindrance in brain ECS remain under investigation but are thought to include an increased path length around local obstacles[20], delay within dead-space microdomains[21], steric hindrance and drag caused by the finite ECS width[19], and the effects of charge and/or binding to the extracellular matrix (ECM) or cellular components[17, 18, 22].

Here we have used IOI [20, 23] to measure the real-time in vivo diffusion of fluorescently labeled immunoglobulin G (IgG) in the rat somatosensory cortex and explore the effect of FcγR binding on local antibody distribution in the brain microenvironment. The relevance of our IOI-derived diffusion parameters was shown by their use in predicting and interpreting whole brain distribution profiles following controlled intracisternal infusion into the CSF of anesthetized rats. Our findings represent the first in vivo measurements of IgG diffusion in brain ECS, allowing for quantitative comparisons with other macromolecules and more accurate modeling of IgG distribution following its controlled release within the brain.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal preparation

Experiments were carried out at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines and local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee regulations. For IOI, female Sprague-Dawley rats (180–240 g) were anesthetized with urethane (1.5 g/kg i.p.), tracheotomized, and placed in a three-point head holder (Narishige) for preparation of an open cranial window over the left parietal cortex, as described previously[19, 22]. Briefly, a custom fabricated chamber was fixed to the skull and an approximately 3- × 4-mm craniotomy was performed over the primary somatosensory cortex. Artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF; composition, mM: 124 NaCl, 3 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1.3 MgCl2, 1.5 CaCl2, and 10 D-glucose equilibrated with 95% O2/ 5% CO2; 300 ± 5 mOsm/kg osmolality determined using a freezing-point osmometer, Model 3250 Osmometer, Advanced Instruments) was heated to 37±1°C using a solution in-line heater (TC-344B, Warner Instruments) and continuously superfused through the chamber ports at 2 ml/min (Minipuls 3, Gilson) for the duration of experiments. The dura was then carefully removed before animals were positioned under an Olympus BX61WI microscope for imaging after an equilibration period of at least 1 hr.

2.2. Fluorescent conjugates

Experiments utilized Alexa Fluor 488-labeled highly cross-adsorbed goat anti-rabbit IgG (AF488-IgG; ~6 mol AF488/1 mol IgG; Invitrogen), a non-targeted antibody. AF488-IgG was used alone at a concentration of 2 mg/ml (13 µM) in PBS (pH 7.5). Further diffusion measurements tested the effect of Fc binding using an excess of goat Fc fragment (Jackson ImmunoResearch) with a ~35:1 ratio of unlabeled Fc to AF488-IgG. All solutions were vortexed briefly, centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 3 minutes, and loaded into micropipettes pulled from thin-wall borosilicate capillary glass (catalog 617000, A-M Systems) with a tip diameter of 3–10 µm.

2.3. Diffusion measurements using integrative optical imaging (IOI)

IgG diffusion was evaluated in free solution and in the rat neocortex in vivo as previously described using IOI[19, 22], an extensively characterized and validated method for local diffusion measurements over distances spanning a few hundred microns[20, 23, 26, 27]. This method utilizes epifluorescent microscopy and quantitative image analysis to measure the diffusion of fluorescently labeled molecules over time following a brief pressure ejection from a micropipette, approximating a point source. The full IOI set-up has been described previously[23]; our system consisted of an Olympus BX61WI microscope with a water-immersion objective (UM PlanFl 10×, NA 0.3; Olympus), 75-W xenon epi-illuminator, and dichromatic mirror system and appropriate filter for AF488 (U-N49002, Chroma). Small volumes (~25–50 picoliters[28]) were typically ejected using a 50–250 ms nitrogen pulse from a pressure ejection system (Toohey Spritzer, Toohey Company). Following ejection, successive images of the diffusion cloud were recorded at regular intervals of 4–8 s by a cooled charge coupled device camera (Cool-Snap HQ2, Photometrics) using a custom program in MatLab (The MathWorks) provided by C. Nicholson and L. Tao[20]. During image collection, illumination was kept constant and only images with fluorescence intensities within the camera’s linear range were used for analysis.

Image analysis with a second MatLab program (C. Nicholson) accounted for how the 3D diffusion cloud projected onto the camera using the following expressions:

| (Equation 1) |

and

| (Equation 2) |

where Ii is the fluorescence intensity of the ith image at radial distance r from the source point, and Ei incorporates the defocused point spread function of the microscope objective[26]. To account for deviation from the point source approximation, a time offset, t0, was added to the measured time from injection, ti; such an approximation does not affect analysis under typical experimental conditions[29]. Eq. 1 was fit to the upper 90% of the fluorescence intensity curves using a nonlinear simplex algorithm, providing estimates of a parameter, γ2, at a succession of ti intervals. A linear regression plot of γ2/4 versus ti returned a slope equal to D* (or D) based on Eq. 2. Analyses were performed using curves across six axes of the intensity clouds with the final value of D* (or D) obtained from an average of four values (excluding the highest and lowest).

Measurements of D were made at 37 ± 1°C using 0.3% NuSieve GTG agarose (FMC) in 154 mM NaCl at depths of 1–2 mm from the gel surface. Measurements of D* were at a depth of 200 µm below the pial surface in the primary somatosensory cortex. For in vivo experiments, the pipette was moved to a new location after AF488-IgG injection and full image acquisition to reduce possible environmental changes such as receptor blocking or cellular responses that might alter local diffusion properties. D was further used to calculate the apparent hydrodynamic diameter (dH) using the Stokes-Einstein equation [dH = (kT)/(3πηD), where k is Boltzmann’s constant, T is absolute temperature, and η is the viscosity of water (6.9152 × 10−4 Pa·s at T = 310 K)][23]. Experimental λ values were compared against predictions obtained from a model relating dH and λ for inert pseudo-spherical molecules based on hydrodynamic theory for hindered diffusion[19].

2.4. Modeling

Models were generated and plotted in SigmaPlot using appropriate solutions to Fick’s Second Law. For a semi-infinite medium with a plane boundary at a constant C0 that is not at steady-state, the following applies:

| (Equation 3) |

where ‘erf’ is the error function, Cx is the concentration at a distance x from the brain surface (i.e. the ependymal surface of periventricular tissue or the pial brain surface facing the subarachnoid space), C0 is the concentration in the CSF at the boundary (x = 0), C∞ is the background concentration, and t is the infusion time[30, 31]. For steady state conditions following continuous release from an interface held at a constant concentration, the following applies:

| (Equation 4) |

where ke is the efflux constant (related to the half-life in brain [ke = ln(2) / t1/2])[17, 23].

2.5. Ex vivo fluorescence imaging following in vivo intracisternal infusions

Anesthetized rats were placed in a stereotaxic frame (Stoelting) following initial preparation as described above. A catheter made of a 1/2 inch piece of 33 GA polyether ether ketone (PEEK) tubing (Plastics One) was connected to a 26s GA Hamilton syringe via PE-10 tubing (Solomon Scientific) and controlled by an infusion pump (Quintessential Stereotaxic Injector, Stoelting). PEEK tubing was mounted onto the microelectrode holder of the stereotaxic frame and the system was loaded with the infusate. The cisterna magna was exposed and the PEEK catheter (at a 60° angle to the rat’s level head) was advanced 1 mm into the cisterna magna and sealed with cyanoacrylate. Eighty microliters of AF488-IgG was infused into the cisterna magna at 1.6 µL/min for 50 minutes, similar to a previously described protocol[32]. When the infusion was finished, the catheter was sealed and cut, the abdominal aorta was quickly cannulated, and animals were perfused with ~50 mL 0.01 M phosphate buffered saline followed by ~450 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde. The brain was removed and post-fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde, then sliced into 100 µm sections using a vibratome (Leica VT1000S). Sections were imaged on an Olympus MVX10 using an Orca-flash 2.8 CMOS camera (Hamamatsu), a Lumen Dynamics X-Cite 120Q illuminator and an appropriate filter set (Chroma, U-M49002XL). ImageJ was used to determine fluorescence intensity along a line (80 µm wide × ~500 µm deep) normal to the pial surface in the primary somatosensory cortex of slices located approximately 3 mm posterior to bregma (similar location to IOI diffusion measurements). Assuming fluorescence intensity to be a linear function of concentration in the measurement area, Eq. 3 may be written as:

| (Equation 5) |

where Ix is the concentration at a distance x from the brain surface, I0 is intensity at x=0, and I∞ is the background intensity. Fluorescence intensity data was fit to Eq. 5 using relative intensity as a measure of concentration along the line of measurement to estimate D* of AF488-IgG at the pial surface (i.e. maximum intensity set as I0 at x=0, I∞ set as the minimum background intensity, and time = 50 min of infusion). For graphical display, Eq. 5 was transformed by setting I∞ = 0 to yield:

| (Equation 6) |

3. Results

3.1. Extracellular IgG diffusion is markedly hindered in cortex compared to free solution

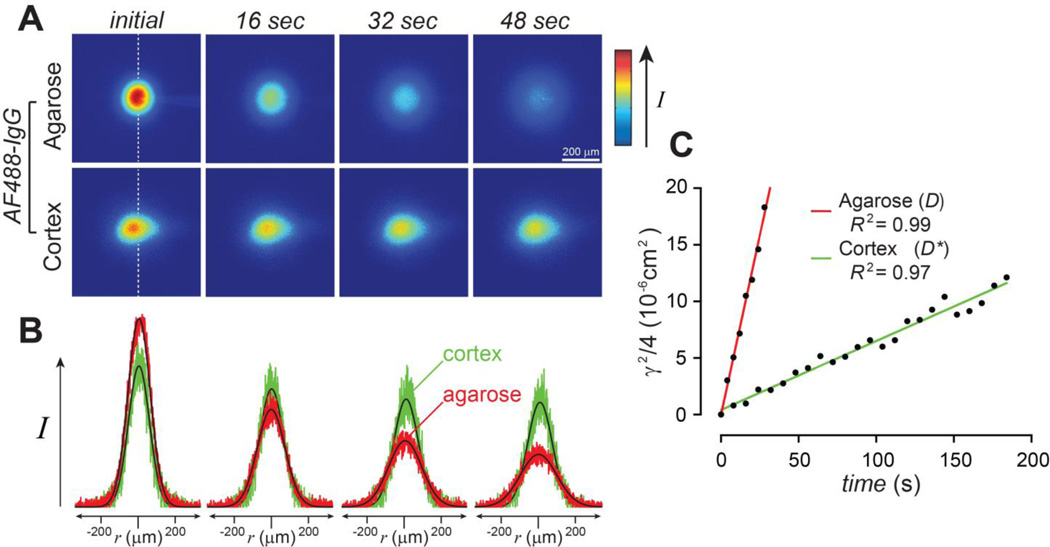

Free diffusion coefficients (D) for AF488-IgG were determined by IOI in dilute (0.3%) agarose, an essentially free medium that reduces thermal convention. In vivo measurements of the effective diffusion coefficient (D*) were performed in the primary somatosensory cortex. After acquiring a background image, AF488-IgG was pressure ejected into either dilute agarose or cortex, and 15–25 subsequent images were taken at regular intervals (4 s intervals in agarose and 8 s intervals in cortex). Figure 2A shows a representative series of images of the diffusion cloud after the subtraction of background intensity for AF488-IgG in free medium (agarose) and cortex. It is evident that the cloud spread and dissipation was faster in agarose than in cortex. Figure 2B depicts the Gaussian-shaped fluorescence intensity curves obtained from the images in 2A, as well as the fit of Eq. 1 to the data at each time point. Theoretical fits (black lines) to the raw data (in color: red, agarose; green cortex) were excellent, suggesting Fickian diffusion in both media. It is easily appreciated that the curves for AF488-IgG in agarose flatten and broaden more rapidly than the curves for AF488-IgG in cortex. This illustrates that AF488-IgG diffusion was hindered in cortex relative to agarose (water), as expected, and is further reflected in the nearly 10-fold higher value obtained for D than D* from the linear regression of the data shown in Fig 2C. Using the mean D for AF488-IgG (Table 1), its apparent hydrodynamic diameter (dH) was determined to be 10.15 ± 0.17 nm using the Stokes-Einstein equation. Using both mean D and D* values (Table 1), calculation of AF488-IgG tortuosity (λ), an overall measure of diffusional hindrance in brain ECS relative to free solution, yielded λ = 3.11 ± 0.09, suggesting a remarkably high hindrance for AF488-IgG in cortex.

Figure 2.

Antibody diffusion is hindered in brain. (A) Representative images acquired after injection of AF488-IgG in 0.3% agarose or somatosensory cortex. (B) Fluorescence intensity data extracted along the 90° axis (white dashed line) from the images in A and fit to the diffusion equation (Eq. 1). The data is in shown in color (agarose, red; cortex, green) to facilitate comparison to the curve fits at each time point (black). (C) Data records in A and B were used to determine γ2/4 at each time point (Eq. 1) with linear regression of γ2/4 on time (Eq. 2) returning a slope of D or D* after data transformation to a zero y-intercept. Fitting of these individual records yielded D (37°C) = 63.4 × 10−8 cm2/s and D* (37°C) = 6.42 × 10−8 cm2/s with a very high coefficient of determination (R2), indicating the data were fit well.

Table 1.

Diffusion parameters for IgG in agarose and brain in the absence or presence of excess unlabeled Fc fragment

| Dilute agarose D (10−8 cm2/s) |

Hydrodynamic diameter, dH (nm)a |

Effective brain D* (10−8 cm2/s) |

Tortuosity, (λ = [D/D*]1/2) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AF488-IgG | 64.7 ± 1.1 (29) | 10.15 ± 0.17 | 6.68 ± 0.22 (10) | 3.11 ± 0.09 |

| AF488-IgG + Fc (1 : 35) |

67.1 ± 1.9 (9) | 9.79 ± 0.28 | 7.43 ± 0.30 (7) | 3.01 ± 0.11 |

Values determined at 37°C are reported as mean ± s.e. (n measurements);

apparent hydrodynamic diameter determined from Stokes-Einstein equation

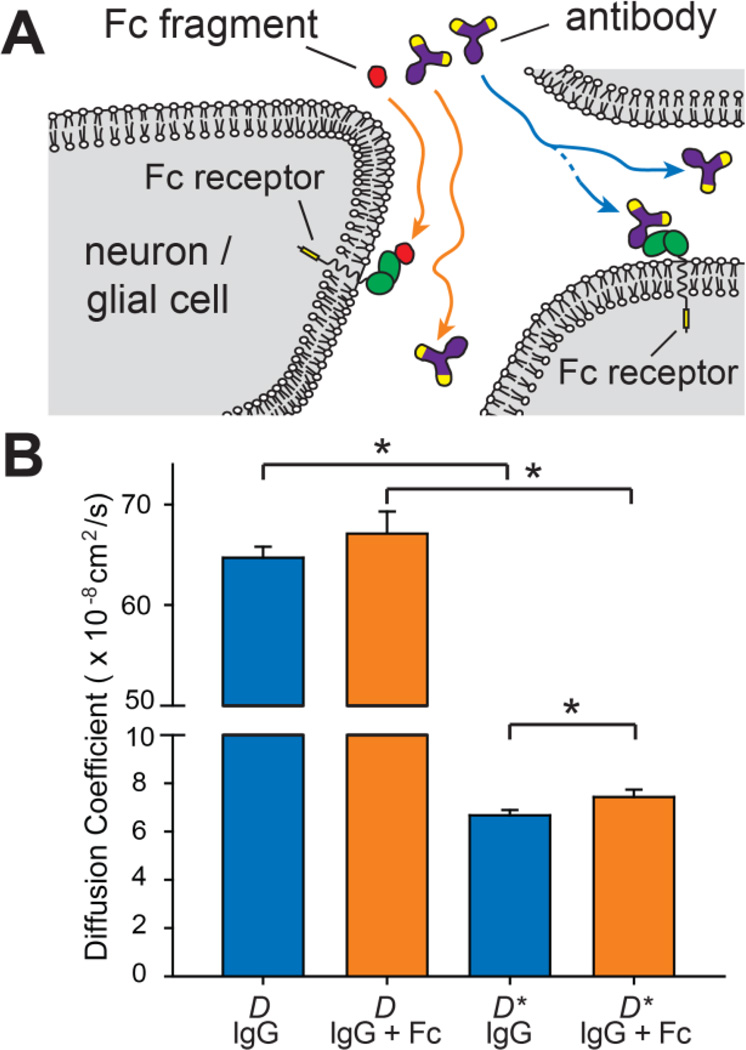

3.2. Extracellular IgG diffusion in brain is slowed by Fc binding

Our previous work has provided quantitative relationships that can be used to predict λ for diffusing substances of a given dH[17]; these relationships exhibit experimentally validated behavior (e.g. increasing values of λ as dH is increased[19] or rapid, reversible binding to relatively fixed brain ECS sites such as extracellular matrix components or cell surface receptors becomes applicable[22]) with particular usefulness as an aid in the interpretation of new experimental data. One of these relationships, a multicomponent model of tortuosity for relatively inert (non-binding) substances diffusing in normal adult isoporous brain ECS[19] is potentially instructive in the interpretation of our AF488-IgG data; the relationship is based on fitting prior experimental data to a model of the brain ECS as either cylindrical pores or parallel planes, yielding model parameters (pore diameters) based on hydrodynamic theory for hindered diffusion[33]. This particular model has been shown to provide excellent agreement with experimentally determined λ values for a wide variety of relatively inert macromolecules (e.g. dextrans and several proteins)[19, 22]; significant deviations from the model in the form of a higher than predicted experimental λ value have been shown to indicate additional sources of hindrance such as interactions with relatively fixed ECS binding sites[22]. Model predictions for a relatively inert diffusing macromolecule with a dH = 10.15 nm corresponding to AF488-IgG yielded an expected λ = 2.34–2.36, a value significantly smaller than our experimentally determined value for AF488-IgG. Indeed, the experimental value of D* for AF488-IgG was reduced by ~40% from that expected for a relatively inert macromolecule of equivalent size. We hypothesized a likely additional source of hindrance for IgG diffusing in brain ECS to be a binding interaction with endogenous FcγRs and decided to explore this further.

Goat anti-rabbit highly cross-adsorbed IgG was chosen for our experiments to limit specific binding interactions. However, previous studies have demonstrated Fc receptor affinity across species, e.g. between human Fc receptors and mouse antibodies[34]. We therefore investigated the effect of co-injecting excess unlabeled goat Fc fragment along with AF488-IgG; if AF488-IgG diffusion through brain ECS was slowed by rapid, reversible FcγR binding, co-injecting excess unlabeled Fc would be expected to reduce this interaction and result in a higher effective diffusion coefficient (Figure 3A). Indeed, the effects of a chemical reaction, e.g. binding, on diffusion in brain ECS have previously been demonstrated with the 80 kDa iron-binding protein lactoferrin, where co-injection with heparin was shown to inhibit lactoferrin binding to endogenous heparan sulfate proteoglycans[22]. Free diffusion experiments with AF488-IgG were first repeated with an excess of Fc fragments with no significant change seen in the value of D (Table 1 & Figure 3B), as expected. However, measurements of AF488-IgG diffusion in brain demonstrated that co-injecting excess unlabeled Fc significantly increased the value of D* (P = 0.049, one-tailed student T-test), decreasing λ in the process (Table 1 & Figure 3B). While the ~11% increase in D* for AF488-IgG was not sufficient to increase its effective diffusion in brain ECS to that predicted for a relatively inert macromolecule of similar size, it nevertheless suggests in vivo FcγR binding may have played some role in attenuating IgG diffusion in our measurements.

Figure 3.

Antibody diffusion in brain is attenuated by Fc binding. (A) Schematic showing IgG antibody movement through brain ECS and the hypothetical role that rapid, reversible binding to endogenous, cell surface Fc receptors might play in reducing IgG diffusion. If an IgG-Fc interaction were to slow IgG transport, the presence of excess Fc would be expected to compete off this interaction, allowing IgG to move more freely. (B) Summary data comparing D and D* for IgG with (orange) and without (blue) a 35-fold molar excess of unlabeled Fc (*P < 0.05; one-tailed student T-test; no significant difference was observed between D values for the two groups – note the break in the graph).

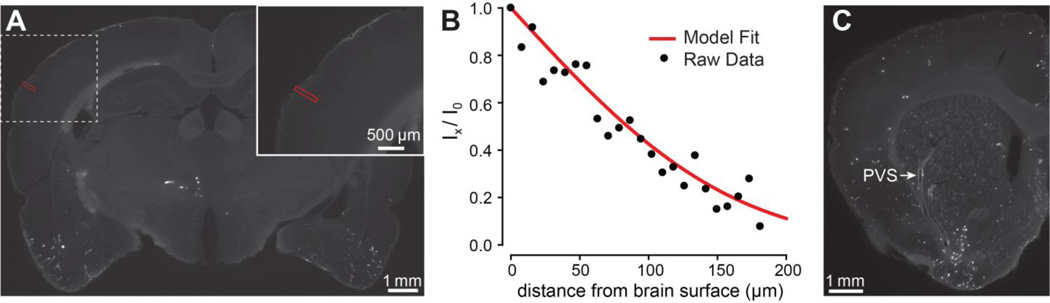

3.3. Intracisternal infusion gradients confirm diffusive transport of IgG into brain tissue

We evaluated how well our IOI-derived IgG diffusion parameters predicted brain distribution at the brain-CSF interface following controlled, slow-flow intracisternal infusions into the CSF. While our general approach resembled an older radiotracer method pioneered by Fenstermacher and colleagues[30, 35], our use of AF488-IgG as a fluorescent tracer for the infusions (the same conjugate used for IOI) allowed for much higher resolution measurements and a more direct comparison with IOI diffusion data. Figure 4A shows a representative coronal section following a 50 min AF488-IgG infusion, revealing a sharp fluorescence intensity gradient at the pial brain surface upon close examination. Fitting Eq. 5 to the fluorescence intensity profile along lines normal to the brain surface within the somatosensory cortex (Figure 4B) suggested diffusive transport had occurred at many brain-CSF interfaces, yielding a lower observed effective diffusive coefficient (D* = 2.1 ± 0.3 × 10−8 cm2/s; n = 12; N = 3 animals) than obtained with IOI, although similar in magnitude.

Figure 4.

Antibody distribution after infusion into the CSF. (A) Coronal image (~3 mm posterior to bregma) obtained after AF488-IgG infusion into the cisterna magna for 50 min, revealing a signal gradient at the pial surface. (B) Fluorescence intensity was measured along a line (red) normal to the brain surface in A. Intensity data was fitted to Eq. 5 (here yielding D* = 2.6 × 10−8 cm2/s) and replotted as Eq. 6 to facilitate comparison of the model fit to the raw data. (C) Limited distribution in perivascular spaces (PVS) was often evident in brain sections along with steep signal gradients at the pial surface (coronal image, ~1 mm anterior to bregma).

4. Discussion

4.1. Validation and interpretation of IOI measurements of IgG diffusion in brain ECS in vivo

IOI has already been extensively applied to measure both free diffusion in dilute agarose (yielding D) and effective diffusion in brain tissue (yielding D*) for a variety of different fluorescently labeled proteins, dextrans and other substances. IOI-derived D values have consistently agreed well with that obtained from other quantitative methods[17–23, 27, 31] as well as predictive correlations for proteins based on molecular weight[22, 23], providing important validation of the IOI method in its application with different probe substances. Our free diffusion coefficient for IgG (D(37°C) = 65 × 10−8 cm2/s) agreed well with predictions from correlation expressions for protein free diffusion (summarized in Thorne et al.[23]), where Dpredicted (37°C) for a 150 kDa protein ranged from 65.5 to 79.3 × 10−8 cm2/s; a slight additional reduction in our D value from these predictions may be attributed to the presence of the covalently attached fluorophores[23]. Our experimental D value was also consistent with previously published measurements of fluorescently labeled-IgG free diffusion using other methods such as fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (D(37°C) = 63 × 10−8 cm2/s)[36] and fluorescence imaging of profiles (D(37°C) = 58.9 × 10−8 cm2/s)[37]. The excellent agreement between our value of D for IgG, protein correlations based on molecular weight and experimental values from other quantitative methods confirms the monomeric behavior of AF488-IgG in free solution and its stable measurement using IOI.

It is very important to accurately characterize and understand the factors governing the in vivo diffusion behavior of proteins such as IgG because of their potential use as centrally applied therapeutics[13, 15]. Our experimental value for D* represents the first such measurement using a method focused exclusively on IgG antibody diffusion in brain ECS in vivo. Our effective diffusion coefficient for IgG (D*(37°C) = 6.7 × 10−8 cm2/s) was reduced by nearly a factor of 10 in comparison to its free diffusion coefficient, yielding a tortuosity for IgG in somatosensory cortex of λ = 3.11. Our in vivo λ value for IgG is higher than that obtained previously in vivo for a number of smaller molecular weight dextrans[19] and the iron binding protein transferrin (80 kDa)[22], as expected; indeed, prior in vivo diffusion studies (as well as most in vitro studies using acute brain slices) have shown a tendency for λ in normoxic neocortex to increase with increasing hydrodynamic size of the diffusing probe, starting at a low value of approximately 1.6 (representing a 2.6-fold difference between D and D*) for the smallest extracellular tracers such as the tetramethylammonium ion (dH ~ 0.5 nm; reviewed in [17] & [18]). We note that our D* value for IgG diffusion in brain ECS is slightly higher than that recently reported by Shi et al. (D*(37°C) = 4.7 × 10−8 cm2/s) for measurements derived from a new in vivo multiphoton method focused on permeability and transport across rat brain blood vessels[38], although the relationship between this group’s measurements of diffusion at the neurovascular unit following infusion into the carotid artery and our measurements from controlled intraparenchymal pressure injections in the neuropil are not completely clear. A recent in vitro study by McLean et al. using a modified form of the IOI method with fluorescently labeled IgG antibodies in an acute brain slice preparation (400 µm neocortical slices from adult mice) yielded a remarkably low λ value of 1.39, suggesting IgG’s effective diffusion coefficient in brain was reduced by less than a factor of 2 compared to its free diffusion coefficient[39]. While McLean et al. estimated a free diffusion coefficient for IgG (D(37°C) = 58 × 10−8 cm2/s; McLean & Shoichet. Personal communication & [39]) similar to what we report here, their estimate of D* was more than 4-fold greater than the D* value measured in the present study. Although the precise reasons for this discrepancy are not obvious, it is likely that a methodological issue arose in the McLean et al. study because a tortuosity of 1.4 would imply that the 150 kDa IgG experiences less relative hindrance to diffusion within the neocortical ECS than any other substance yet studied, including the 74 Da tetramethylammonium, 2 kDa polyethylene glycol, 3 kDa dextran and much smaller proteins such as the ~6 kDa epidermal growth factor[17, 18]. Indeed, an earlier study by the same group[40] examining the diffusion of epidermal growth factor in the neocortex of normal adult murine brain slices yielded a λ value of 1.9 and D* values nearly equivalent to their later estimates for IgG D*, suggesting their IgG diffusion measurements in brain may have suffered from a lack of sensitivity. Overall, our IOI measurements of IgG diffusion significantly extend on previous related work and provide the first quantitative evaluation of D* and λ for an antibody in brain ECS in vivo.

Another important finding of the present study is that the diffusional hindrance measured for AF488-IgG in brain ECS was higher than expected based on prior measurements with other large macromolecules (e.g. 70 kDa dextran, with dH ~ 14 nm and λ = 2.68) as well as model predictions for a diffusing inert substance with a dH equal to the Stokes-Einstein diameter of IgG (~10 nm, λpredicted = 2.34–2.36; Section 3.2)[17, 19, 22]. Of the possible explanations for IgG’s high λ value (corresponding to a ~40% lower D*), the most obvious to suspect was a rapid, reversible binding interaction with FcγRs expressed on the cell surfaces of microglia, macroglia and neurons[6–8]. Although we used highly cross-adsorbed goat anti-rabbit IgG to limit any specific binding interactions in the rat brain and therefore reveal the ‘upper limit’ for IgG’s D*, cross-species Fc affinity has been previously reported[34]. We therefore explored the effect FcγR binding had on the extracellular diffusion of our labeled IgG. Co-injection of AF488-IgG with a 35-fold molar excess of unlabeled Fc enhanced the extracellular diffusion of AF488-IgG, as expected, but the modest ~11% increase in D* suggests significant additional sources of hindrance exist. As IgG efflux/elimination from the brain or specific cellular uptake would also likely involve Fc receptor-dependent processes, the lack of a large increase in D* after co-injecting Fc suggests elimination and/or uptake did not play an important role in IgG’s low D* under our experimental conditions; indeed, the total imaging time used here for IOI in brain (~5 min or less) was significantly shorter than the expected in vivo clearance half-life of IgG (e.g. reported IgG t1/2 values in brain have ranged from 48 min[41] to 12.8 hr[42]). It is possible that fluorophore conjugation to IgG may have altered the affinity of its interaction with endogenous Fc receptors. It is also possible that IgG’s unique geometry (Figure 1) could be partly responsible for the high diffusional hindrance we measured for our fluorescently labeled goat IgG because its long axes likely extend further in solution than its dH suggests. The flexibility of IgG’s hinge region may also be important; this region connects the two Fab domains with the Fc domain and may confer significant conformational freedom on IgG as it diffuses in a confined environment such as the brain ECS. These flexible hinges are thought to allow IgGs to reach a wider range of antigen sites, facilitating antigen recognition and enhancing its activity[4]. Different IgG isoforms have hinge regions that vary in length and flexibility (e.g. murine IgG1 has a shorter, less flexible hinge compared to murine IgG2a[24] while the hinge region of goat IgG has limited homology and a large gap in residues compared to human IgG isoforms, suggesting goat IgG may be less flexible than human IgG[43]). More flexibility in the IgG hinge region may allow certain IgGs to diffuse slightly better through the narrow brain ECS than expected based on the length of their hydrodynamic axes, e.g. studies with significantly larger dextrans have shown that conformational flexibility allows random coil polymers larger than the ECS width to extracellularly diffuse by processes such as reptation[44]. Another possible contributing factor to our AF488-IgG’s high λ value may be related to charge effects. The isoelectric point of unconjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG is less than 7[45] while the additional covalent attachment of six negatively charged AF488 fluorophores would be expected to shift the resulting conjugate further toward the acidic range. For a molecule as large as AF488-IgG diffusing through a narrow brain ECS containing an abundant, negatively charged ECM composed of glycosaminglycans and proteoglycans[18, 22], electrostatic effects might produce a small reduction in D* through charge repulsion; indeed, studies with IgG and other large serum proteins have indicated such an effect in narrow (20 nm), engineered nanochannel arrays[45]. The possible dependence of D* on geometric and charge effects associated with different IgG isoforms will require further study.

4.2. Significance of limited IgG diffusion in brain ECS for central delivery of antibodies and antibody-based drugs

There is a large amount of experimental evidence suggesting that solute exchange between the CSF and adjacent brain tissue is governed, at least in part, by diffusive transport within brain ECS[3, 17, 18, 30, 35, 46]; however, recent work has refocused interest on the possible role that transport within perivascular spaces (PVS), micron-sized channels surrounding cerebral blood vessels, may play in whole brain distribution following infusions into the CSF[32, 47]. The relative contribution of diffusive transport in brain ECS versus convective transport in the PVS for IgG distribution from CSF to brain is an important question for both central immunotherapy approaches and for better understanding the neuroimmunological role of endogenous CSF IgG. We developed a new application of ex vivo fluorescence imaging following intracisternal infusion to confirm and quantify diffusive transport of IgG from the CSF into adjacent brain at the pial surface, based in part on theory described for the well-established radiotracer technique that has previously been used to determine diffusion coefficients in brain for a variety of smaller molecular weight substances (e.g. sucrose and inulin)[30, 35]. This involved a slow intracisternal infusion of AF488-IgG (1.6 µl/min[32]; chosen to be below normal rat CSF production of 2–5 µl/min[48]) into the subarachnoid space CSF followed by upper body perfusion-fixation and subsequent imaging of the resulting fluorescence intensity gradients at the brain surface. Our results were consistent with diffusive transport governing the distribution of AF488-IgG at the pial surface, yielding a D* value (2.1 × 10−8 cm2/s) lower than that determined using the local IOI method in the somatosensory cortex but similar in magnitude. While our ex vivo fluorescence method for determining diffusion parameters after intracisternal infusion may need further refinements to conform as well to the applied diffusion theory as the IOI method, the similarity in D* values obtained by the two methods is nevertheless striking. It is possible that the lower D* we measured at the pial brain surface-CSF interface compared to the result obtained from IOI performed in the somatosensory cortex may be attributed to local differences in Fc receptor expression or increased hindrance associated with the glia limitans (interleaved processes of astrocytes present just below the pia)[46], but this will require further study. The glia limitans has previously been suggested to limit the distribution of sucrose (342 Da; dH ~ 0.9 nm) into brain from the CSF in some regions[46] so its effect on the much larger IgG may even be more pronounced. We did observe limited distribution of IgG within the PVS of cerebral blood vessels, more notable ventrally in some brain slices (Figure 4C) than in others (Figure 4A); the observed PVS distribution of IgG, occurring over large distances spanning many millimeters and more striking within certain vessels (e.g. lenticulostriate in Figure 4C), was consistent with a convective process and qualitatively similar to that seen with other fluorescently labeled macromolecules (e.g. dextran tracers) in recent reports[32, 47]. In summary, our findings confirm a prominent role for diffusive transport in governing distribution at the brain-CSF interface for IgG, in line with qualitative findings from previous reports for IgG[49] as well as other large proteins[50].

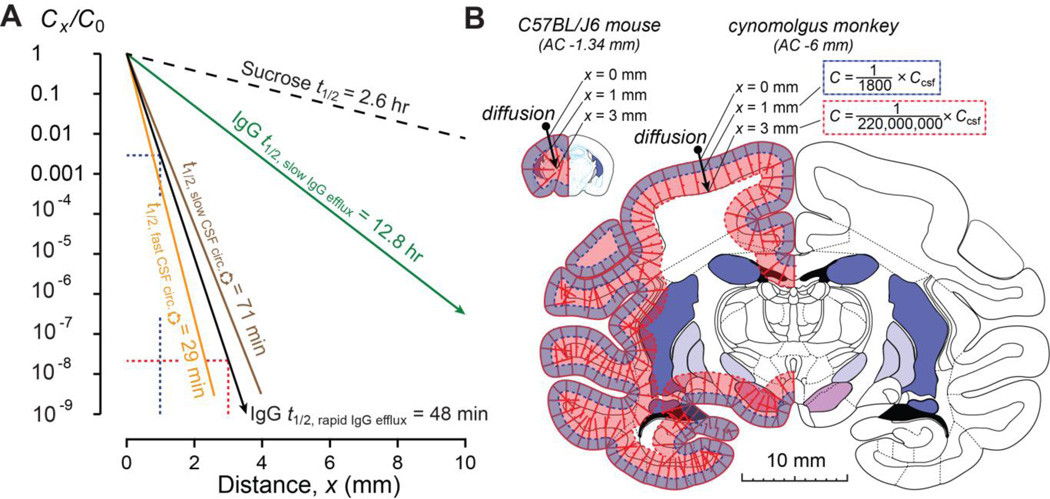

The significance of our findings for the central delivery of IgG, particularly for its clinical application in human beings, can perhaps best be understood by some simple modeling of its distribution in brains of different size. Figure 5A shows steady state distribution profiles predicted for IgG and for the small sucrose molecule following long infusions into the CSF, such as might be done clinically. The profiles were obtained assuming diffusive transport at the brain surface, using experimental D* values and brain efflux constants (ke) along with Eq. 4; as can be seen, varying either of these parameters significantly affects the resulting concentration profile. Parameters for sucrose, included for comparison purposes, were taken from the literature (D* = 310 × 10−8 cm2/s [35]; ke = 0.26 hr−1 or t1/2 = 2.62 hr [53]) while the D* for IgG was from the present study’s IOI measurements (6.7 × 10−8 cm2/s). As already mentioned, clearance half-lives for IgG have been reported to vary widely (e.g. from 48 min[41] to 12.8 hr[42] in the rat); comparison of these reported values with literature turnover times for rat CSF (t1/2 = 29–71 min)[3] indicate a higher IgG ke (t1/2 = 48 min) may be more appropriate to describe the kinetics of IgG elimination from the CSF compartment. Utilizing this higher ke and our IOI-derived D* for IgG, predicted IgG concentration profiles resulting from diffusive transport in brains of different size are shown in Figure 5B. Taking into account that diffusion does not scale with larger brain size[17], it is easily appreciated that a long CSF infusion of IgG in a small animal such as a mouse would be expected to yield higher levels throughout the cortical layers (outermost area of tissue) than a similar infusion in a larger animal such as a cynomolgus monkey (or an even larger human being). Limited penetration and the associated steep concentration profiles of IgG with distance would appear to present a large challenge to the clinical application of centrally applied IgG, despite promising pre-clinical findings typically seen in murine models of disease (e.g. with intracerebroventicular application[13]). We note that these profiles may potentially be modified by other processes at brain-CSF interfaces, e.g. convection within the PVS, as well as improved diffusion characteristics or reduced brain clearance. Our results provide better understanding of the balance that exists between diffusive and convective processes governing the central distribution of antibodies and suggest possible strategies for manipulating them. For example, antibody engineering may possibly be used to finely tune IgG distribution by altering Fc receptor affinity. It is also expected that smaller antibody-based drugs, e.g. Fab (~50 kDa) or single domain fragments (~15 kDa)[5], may benefit from better diffusion characteristics and whole brain distribution profiles than full length IgG antibodies.

Figure 5.

Modeling of antibody penetration into brain from the CSF. (A) Concentration profiles (Cx/C0) determined from Eq. 4 (steady-state), based on experimental values for effective diffusion coefficients (D*) and brain efflux constants (ke) for sucrose, a small molecule, or IgG. Sucrose penetrates much further with a far less severe concentration profile as compared to IgG under different brain efflux conditions. IgG model predictions utilizing half-lives for CSF turnover in the rat to determine ke are also depicted. See text for additional details. (B) IgG concentration profiles with distance depicted on brains of different size. Profiles correspond to results from Eq. 4 using a rapid IgG efflux (t1/2 = 48 min) and D* from the present study (corresponding to the solid black line in A). The predicted concentration at 1- and 3- mm depths from the brain surface in mouse (atlas figure adapted from [51]) and non-human primate brain (atlas figure adapted from [52]) are indicated.

5. Conclusions

We report the first quantitative determination of IgG antibody diffusion in brain ECS in vivo using integrative optical imaging following local intraparenchymal injection, an established technique for quantitative diffusion studies in different media. We also confirm the value and predictive ability of these IgG diffusion measurements using ex vivo fluorescence imaging of pial brain surface gradients resulting from whole brain distributions after controlled intracisternal infusions. The major findings of the present study are: (i) the effective diffusion coefficient of IgG in neocortical ECS is reduced from its value in free solution by nearly one full order of magnitude, meaning its extracellular distribution in brain tissue is significantly hindered, (ii) at least a portion of IgG’s large diffusional hindrance in neocortical ECS may be attributed to rapid, reversible binding to endogenous FcγRs, and (iii) IgG penetration into the brain following intrathecal infusion into the subarachnoid space CSF compartment confirms diffusive transport in brain ECS is important in governing whole brain IgG distribution by this central delivery route, particularly at the pial surface. These results are important for drug delivery strategies employing central application of IgG antibodies and also have relevance for understanding how endogenous IgG, a major protein component in the CSF, distributes within the CNS for immune surveillance.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Pharmacy, the Graduate School at the University of Wisconsin, the Clinical and Translational Science Award program administered through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NIH UL1TR000427 and KL2TR00428), fellowships from the NIH (NRSA T32 EBO11424 – DJW & MEP) & NSF (DGE-1256259 – MEP), and a fellowship from the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) Foundation (DJW). The authors thank Dr. Jeffrey Lochhead and Ms. Niyanta Kumar (University of Wisconsin-Madison) for reviewing the manuscript. RGT acknowledges (i) periodically receiving honoraria for speaking to organizations within academia, foundations, and the biotechnology and pharmaceutical industry and (ii) occasional service as a consultant on CNS drug delivery to industry.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wang W, Wang EQ, Balthasar JP. Monoclonal antibody pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:548–558. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hortin GL, Sviridov D, Anderson NL. High-abundance polypeptides of the human plasma proteome comprising the top 4 logs of polypeptide abundance. Clin Chem. 2008;54:1608–1616. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.108175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davson H, Segal MB. Physiology of the CSF and blood-brain barriers. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandin S, Ofverstedt LG, Wikstrom AC, Wrange O, Skoglund U. Structure and flexibility of individual immunoglobulin G molecules in solution. Structure. 2004;12:409–415. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holliger P, Hudson PJ. Engineered antibody fragments and the rise of single domains. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1126–1136. doi: 10.1038/nbt1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okun E, Mattson MP, Arumugam TV. Involvement of Fc receptors in disorders of the central nervous system. Neuromolecular Med. 2010;12:164–178. doi: 10.1007/s12017-009-8099-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohamed HA, Mosier DR, Zou LL, Siklos L, Alexianu ME, Engelhardt JI, Beers DR, Le WD, Appel SH. Immunoglobulin Fc gamma receptor promotes immunoglobulin uptake, immunoglobulin-mediated calcium increase, and neurotransmitter release in motor neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2002;69:110–116. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Komine-Kobayashi M, Chou N, Mochizuki H, Nakao A, Mizuno Y, Urabe T. Dual role of Fcgamma receptor in transient focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Stroke. 2004;35:958–963. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000120321.30916.8E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho RJY, Gibaldi M. Biotechnology and biopharmaceuticals : transforming proteins and genes into drugs. Second edition. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley-Blackwell; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lampson LA. Monoclonal antibodies in neuro-oncology: Getting past the blood-brain barrier. MAbs. 2011;3:153–160. doi: 10.4161/mabs.3.2.14239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neuwelt EA, Barnett PA, Hellstrom I, Hellstrom KE, Beaumier P, McCormick CI, Weigel RM. Delivery of melanoma-associated immunoglobulin monoclonal antibody and Fab fragments to normal brain utilizing osmotic blood-brain barrier disruption. Cancer Res. 1988;48:4725–4729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deane R, Sagare A, Hamm K, Parisi M, LaRue B, Guo H, Wu Z, Holtzman DM, Zlokovic BV. IgG-assisted age-dependent clearance of Alzheimer's amyloid beta peptide by the blood-brain barrier neonatal Fc receptor. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11495–11503. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3697-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thakker DR, Weatherspoon MR, Harrison J, Keene TE, Lane DS, Kaemmerer WF, Stewart GR, Shafer LL. Intracerebroventricular amyloid-beta antibodies reduce cerebral amyloid angiopathy and associated micro-hemorrhages in aged Tg2576 mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4501–4506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813404106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moreth J, Mavoungou C, Schindowski K. Passive anti-amyloid immunotherapy in Alzheimer's disease: What are the most promising targets? Immun Ageing. 2013;10:18. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammarlund-Udenaes M, Lange ECMd, Thorne RG. Drug delivery to the brain : physiological concepts, methodologies and approaches. New York ; Heidelberg: Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu YJ, Zhang Y, Kenrick M, Hoyte K, Luk W, Lu Y, Atwal J, Elliott JM, Prabhu S, Watts RJ, Dennis MS. Boosting brain uptake of a therapeutic antibody by reducing its affinity for a transcytosis target. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002230. 84ra44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolak DJ, Thorne RG. Diffusion of macromolecules in the brain: implications for drug delivery. Mol Pharm. 2013;10:1492–1504. doi: 10.1021/mp300495e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sykova E, Nicholson C. Diffusion in brain extracellular space. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1277–1340. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thorne RG, Nicholson C. In vivo diffusion analysis with quantum dots and dextrans predicts the width of brain extracellular space. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5567–5572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509425103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicholson C, Tao L. Hindered diffusion of high molecular weight compounds in brain extracellular microenvironment measured with integrative optical imaging. Biophys J. 1993;65:2277–2290. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81324-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hrabetova S, Hrabe J, Nicholson C. Dead-space microdomains hinder extracellular diffusion in rat neocortex during ischemia. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8351–8359. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-23-08351.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thorne RG, Lakkaraju A, Rodriguez-Boulan E, Nicholson C. In vivo diffusion of lactoferrin in brain extracellular space is regulated by interactions with heparan sulfate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8416–8421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711345105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thorne RG, Hrabetova S, Nicholson C. Diffusion of epidermal growth factor in rat brain extracellular space measured by integrative optical imaging. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:3471–3481. doi: 10.1152/jn.00352.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris LJ, Skaletsky E, McPherson A. Crystallographic structure of an intact IgG1 monoclonal antibody. J Mol Biol. 1998;275:861–872. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryazantsev S, Tischenko V, Nguyen C, Abramov V, Zav'yalov V. Three-dimensional structure of the human myeloma IgG2. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tao L, Nicholson C. The three-dimensional point spread functions of a microscope objective in image and object space. J Microsc. 1995;178:267–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1995.tb03604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tao L, Nicholson C. Diffusion of albumins in rat cortical slices and relevance to volume transmission. Neuroscience. 1996;75:839–847. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00303-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cragg SJ, Nicholson C, Kume-Kick J, Tao L, Rice ME. Dopamine-mediated volume transmission in midbrain is regulated by distinct extracellular geometry and uptake. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:1761–1771. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.4.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prokopova-Kubinova S, Vargova L, Tao L, Ulbrich K, Subr V, Sykova E, Nicholson C. Poly[N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide] polymers diffuse in brain extracellular space with same tortuosity as small molecules. Biophys J. 2001;80:542–548. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76036-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patlak CS, Fenstermacher JD. Measurements of dog blood-brain transfer constants by ventriculocisternal perfusion. Am J Physiol. 1975;229:877–884. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1975.229.4.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicholson C. Diffusion and related transport mechanisms in brain tissue. Rep Prog Phys. 2001;64:815–884. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iliff JJ, Lee H, Yu M, Feng T, Logan J, Nedergaard M, Benveniste H. Brain-wide pathway for waste clearance captured by contrast-enhanced MRI. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1299–1309. doi: 10.1172/JCI67677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deen WM. Hindered transport of large molecules in liquid-filled pores. Aiche J. 1987;33:1409–1425. [Google Scholar]

- 34.van de Winkel JG, Anderson CL. Biology of human immunoglobulin G Fc receptors. J Leukoc Biol. 1991;49:511–524. doi: 10.1002/jlb.49.5.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fenstermacher J, Kaye T. Drug "diffusion" within the brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;531:29–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb31809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clauss MA, Jain RK. Interstitial transport of rabbit and sheep antibodies in normal and neoplastic tissues. Cancer Res. 1990;50:3487–3492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saltzman WM, Radomsky ML, Whaley KJ, Cone RA. Antibody diffusion in human cervical mucus. Biophys J. 1994;66:508–515. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(94)80802-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi L, Zeng M, Sun Y, Fu BM. Quantification of blood-brain barrier solute permeability and brain transport by multiphoton microscopy. J Biomech Eng. 2014;136 doi: 10.1115/1.4025892. 031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McLean D, Cooke MJ, Wang Y, Fraser P, St George-Hyslop P, Shoichet MS. Targeting the amyloid-beta antibody in the brain tissue of a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Control Release. 2012;159:302–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y, Cooke MJ, Lapitsky Y, Wylie RG, Sachewsky N, Corbett D, Morshead CM, Shoichet MS. Transport of epidermal growth factor in the stroke-injured brain. J Control Release. 2011;149:225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Y, Pardridge WM. Mediated efflux of IgG molecules from brain to blood across the blood-brain barrier. J Neuroimmunol. 2001;114:168–172. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Hear C, Foote J. Antibody buffering in the brain. J Mol Biol. 2006;364:1003–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strausbauch PH, Hurwitz E, Givol D. Interchain disulfide bonds of goat immunoglobulin G. Biochemistry. 1971;10:2231–2237. doi: 10.1021/bi00788a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiao F, Nicholson C, Hrabe J, Hrabetova S. Diffusion of flexible random-coil dextran polymers measured in anisotropic brain extracellular space by integrative optical imaging. Biophys J. 2008;95:1382–1392. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.124743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gao HL, Li CY, Ma FX, Wang K, Xu JJ, Chen HY, Xia XH. A nanochannel array based device for determination of the isoelectric point of confined proteins. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2012;14:9460–9467. doi: 10.1039/c2cp40594f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ghersi-Egea JF, Finnegan W, Chen JL, Fenstermacher JD. Rapid distribution of intraventricularly administered sucrose into cerebrospinal fluid cisterns via subarachnoid velae in rat. Neuroscience. 1996;75:1271–1288. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00281-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, Plogg BA, Peng W, Gundersen GA, Benveniste H, Vates GE, Deane R, Goldman SA, Nagelhus EA, Nedergaard M. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid beta. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003748. 147ra111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thorne RG. Primer on central nervous system structure/function and vasculature, ventricular system, and fluids of the brain. In: Hammarlund-Udenaes M, Lange ECMd, Thorne RG, editors. Drug delivery to the brain : physiological concepts, methodologies and approaches. New York ; Heidelberg: Springer; 2014. pp. 685–707. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Broadwell RD, Sofroniew MV. Serum proteins bypass the blood-brain fluid barriers for extracellular entry to the central nervous system. Exp Neurol. 1993;120:245–263. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ziegler RJ, Salegio EA, Dodge JC, Bringas J, Treleaven CM, Bercury SD, Tamsett TJ, Shihabuddin L, Hadaczek P, Fiandaca M, Bankiewicz K, Scheule RK. Distribution of acid sphingomyelinase in rodent and non-human primate brain after intracerebroventricular infusion. Exp Neurol. 2011;231:261–271. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Compact 2nd ed. Amsterdam ; Boston: Elsevier Academic Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martin RF, Bowden DM. Primate brain maps : structure of the macaque brain. Amsterdam ; New York: Elsevier; 2000. pp. viii, 160 p. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Groothuis DR, Vavra MW, Schlageter KE, Kang EW, Itskovich AC, Hertzler S, Allen CV, Lipton HL. Efflux of drugs and solutes from brain: the interactive roles of diffusional transcapillary transport, bulk flow and capillary transporters. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:43–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]